Dear Editor,

Meningoencephalomyelitis is a heterogeneous group of overlapping central nervous system (CNS) inflammatory diseases that often occur after infection.1 However, meningoencephalomyelitis caused by an autoimmune response is uncommon, which can delay the diagnosis or lead to misdiagnosis by clinicians. Here we describe a patient with varicella zoster virus (VZV) meningitis who developed atypical meningoencephalomyelitis after an interval of 12 days; we also review the relevant literature.

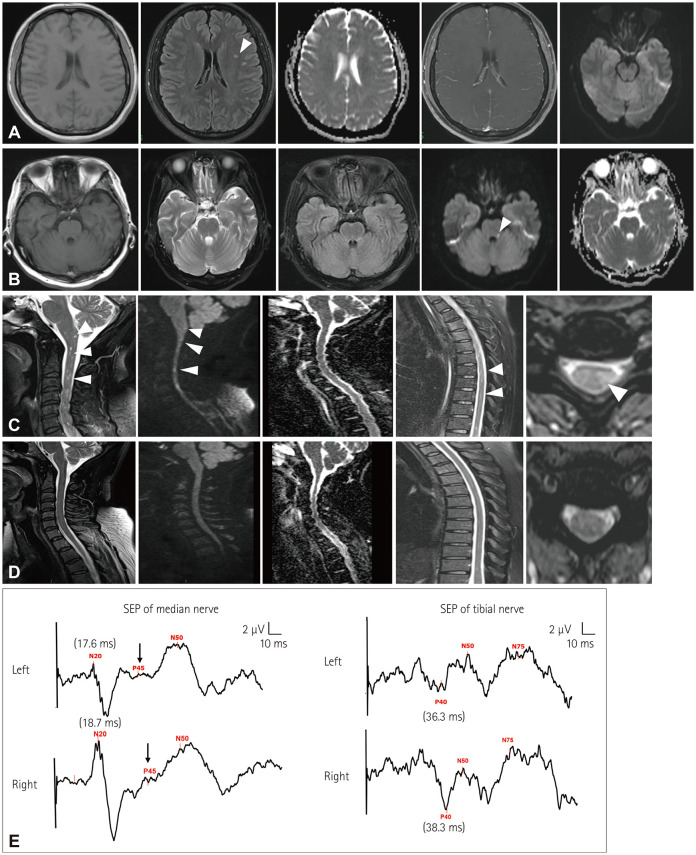

A 43-year-old female presented with a 5-day history of fever and headache. A neurological examination showed no other neurological disturbance other than mild neck resistance. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multifocal low-intensity T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) signals and high-intensity T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery signals in the left cerebral hemisphere without gadolinium enhancement (Fig. 1A). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure was 285 mm H2O (normal range, 80–180 mm H2O), the cell count was 106×106/L (normal range, 0–8×106/L) with 95% being mononuclear cells, the protein level was 1.02 g/L (normal range, 0–0.45 g/L), and the glucose level was 3.5 mmol/L (normal range, 2.5–4.5 mmol/L). The serum glucose level was 4.8 mmol/L (normal range, 3.6–6.1 mmol/L). VZV DNA was detected in the CSF by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The patient was diagnosed with VZV meningitis and treated with intravenous acyclovir. One day after the treatment, her temperature returned to normal and her headache was relieved. However, she developed lethargic and symmetric weakness in all four limbs on day 12 after the onset. The limb weakness progressed to nadir on day 15. A neurological examination revealed Medical Research Council grades of 3/5 and 1/5 in the bilateral upper and lower limbs, respectively. Tendon reflexes were absent from all four limbs, but there was no sensory loss. The second MRI showed multifocal low-intensity T1WI signals, high diffusion-weighted imaging signals, and normal apparent diffusion coefficient signals on the left side of the pons and extending from the cervical to the thoracic vertebrae (Fig. 1B and C). The CSF pressure on day 16 was 330 mm H2O, the cell count was 320×106/L, and the protein level was 0.53 g/L. Oligoclonal bands (OB) and autoantibodies against aquaporin 4 (AQP4), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody (GFAP) were negative in both serum and CSF. The findings of nerve conduction studies of the four limbs were normal, but somatosensory evoked potentials measured on day 16 showed discrete cortical potentials, with part of the waves being poorly differentiated (component P45 of the upper limbs) (Fig. 1E), indicating CNS impairment. On day 17, she received intravenous immunoglobulin (0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days) and steroid treatment, after which her limb weakness gradually improved. The third lumbar puncture performed on day 28 showed a CSF pressure of 168 mm H2O, a cell count of 20×106/L, and a protein level of 0.3 g/L. She had almost completely recovered at a 6-month follow-up. The third MRI showed that the area of the lesion in the spinal cord had reduced significantly (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Neuroimaging of the patient with meningoencephalomyelitis following varicella zoster virus infection. A: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain at study entry showing multifocal low-intensity T1-weighted imaging signals, high-intensity T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signals in the left cerebral hemisphere (arrow), and an enhanced image with no gadolinium enhancement. B: MRI of the brain on day 15. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) of the brain showed high-intensity signals but normal apparent diffusion coefficient signals on the left side of the pons (arrow). C: MRI of the spine on day 15. Midsagittal T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) of the spine showed small multifocal areas of high-intensity signals extending from the cervical to the thoracic vertebrae (arrows). DWI of the spine showed multifocal high-intensity signals in the cervical (arrows). Axial T2WI of the cervical showed high-intensity signals (arrow). D: In MRI of the spine 6 months performed later, T2WI showed that the originally high-intensity signals in the cervical and thoracic vertebrae were significantly reduced. DWI of the spine showed no abnormal signals in the cervical vertebra. E: Somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) in the bilateral median and tibial nerves were measured on day 16. The bilateral median SEP of our case showed normal interpeak latencies in the N20 component (17.6 ms and 18.7 ms on the left and right, respectively; both within the normal limit of 20 ms), and were poorly differentiated in the P45 component (arrows). Bilateral tibial SEP showed normal interpeak latencies in the P40 component (36.3 ms and 38.3 ms on the left and right, respectively; both within the normal limit of 40 ms). The SEP indicated impairment of the central nervous system.

This case fulfilled the criteria of VZV meningitis with typical symptoms as well as the PCR-confirmed VZV infection.2 The subsequent clinical presentations of limb weakness developed with an interval of 12 days after VZV meningitis. The patient showed a monophasic clinical course and responded well to steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin. A series of differential diagnoses needed to be considered, including autoimmune and inflammatory diseases affecting the CNS. The suspicion of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis was driven by the close relation between infection and the polysymptomatic deficits of CNS, but that diagnosis was less likely because the brain and spinal MRI did not show a distribution of large and confluent lesions.3 Our case was not consistent with a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder due to the presence of multifocal small lesions in the spinal cord and negativity for both OB and autoantibodies against AQP4.4 She had multifocal lesions in the spinal cord but was seronegative for anti-GFAP antibodies, which did not support the diagnosis of autoimmune GFAP astrocytopathy.5 In light of PCR-confirmed VZV meningitis and multifocal lesions in the spinal cord, this case was considered to be meningoencephalomyelitis following VZV infection.6 The clinical course was different from typical meningoencephalomyelitis, which may have been due to the delayed autoimmune response following VZV infection.

The exact mechanism underlying meningoencephalomyelitis following VZV infection remains unclear. VZV might carry molecular mimics of self-antigens in the CNS and initiate the autoimmune response, leading to damage to the spinal cord. Notably, there was a 12-day interval between VZV meningitis and lesions in the spinal cord for our case. It is also possible that autoimmune lesions are caused by epitope spreading secondary to the release of self-antigens caused by VZV infection. Infectious encephalitis that triggers secondary inflammation or autoimmunity has been reported previously.7 The mechanism of action of meningoencephalomyelitis following VZV meningitis may share a similar pattern and so deserves further investigation.

In conclusion, we have described an uncommon case of meningoencephalomyelitis following VZV infection. When a patient with VZV meningitis is aggravated after antivirus treatment, repeating MRI and lumbar puncture as well as adequate tests for autoantibodies are necessary.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and her family for their supports.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical Science Research, Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University (2023-09C094). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report.

- Data curation: Guorong Zhang, Chen Liu.

- Formal analysis: Chen Liu.

- Funding acquisition: Guorong Zhang.

- Investigation: Chen Liu, Jin Song.

- Methodology: Jin Song.

- Project administration: Yuzhong Wang.

- Writing—original draft: Guorong Zhang.

- Writing—review & editing: Yuzhong Wang.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020QH110).

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1.McKelvie PA, Collins S, Thyagarajan D, Trost N, Sheorey H, Byrne E. Meningoencephalomyelitis with vasculitis due to varicella zoster virus: a case report and review of the literature. Pathology. 2002;34:88–93. doi: 10.1080/00313020120105705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrei G, Snoeck R. Advances and perspectives in the management of varicella-zoster virus infections. Molecules. 2021;26:1132. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tenembaum S, Chitnis T, Ness J, Hahn JS International Pediatric MS Study Group. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurology. 2007;68(16 Suppl 2):S23–S36. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259404.51352.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, Rommer P, Abu-Mugheisib M, Zettl UK, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis--it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shan F, Long Y, Qiu W. Autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy: a review of the literature. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2802. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pahud BA, Glaser CA, Dekker CL, Arvin AM, Schmid DS. Varicella zoster disease of the central nervous system: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory features 10 years after the introduction of the varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:316–323. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A, Mattozzi S, Cárceles-Cordon M, Martinez-Heras E, et al. Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:760–772. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.