Abstract

The importance of V(D)J recombination for generating diversity in the immune system is well established, but the mechanisms which regulate V(D)J recombination are still poorly understood. Although transcription of unrearranged (germ line) immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene segments often precedes V(D)J recombination and has been implicated in its control, the actual role of germ line transcripts in V(D)J recombination is not known. We used a sensitive reverse transcription-PCR assay to study immunoglobulin VH germ line transcripts in proB lines from RAG-deficient mice. All 10 VH families analyzed were germ line transcribed, and germ line transcription was found in all of the cell lines examined, indicating that active chromatin was present in the VH region. However, not all VH families were germ line transcribed in every cell line, and there was a surprising lack of uniformity in the number and family distribution of germ line VH transcripts in individual lines. When V(D)J recombination was activated by restoration of RAG activity, recombinational activity of endogenous VH genes for which germ line transcription was observed could be compared with those of genes for which it was not observed. This analysis revealed multiple examples of endogenous VH gene segments which were rearranged in cells where their germ line transcription was not detectable prior to RAG expression. Thus, our data provide strong support for the idea that V-(D)J recombination does not require germ line transcription of the recombining variable gene segment.

V(D)J recombination is a specialized DNA rearrangement which is unique to immunoglobulin (Ig) and T-cell receptor (TCR) genes. The process involves recognition and double-stranded cleavage by recombinase-activating gene 1 and 2 (RAG1 and RAG2) proteins (47, 56), which recognize highly conserved recombination signal sequences (RSSs) flanking Ig and TCR variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments. Following RAG-dependent DNA cleavage, ubiquitously expressed components of the normal double-strand break repair machinery carry out end processing and religation, so that specific V, D, and J gene segments are fused and the DNA between them is deleted and ultimately lost from the cell. V(D)J recombination is essential for functional expression of Ig and TCR genes and is critical for generating antigen recognition diversity in the immune system (4, 41, 57, 70, 72).

Since cutting, deletion, and rejoining of DNA could potentially be detrimental to genomic integrity, it is not surprising that V(D)J recombination is highly regulated. This process is controlled in several ways (60). First, V(D)J recombination is lymphoid cell specific, occurring only in B and T lymphocytes. Second, it is lineage specific, since Ig gene segments are fully rearranged only in B cells and TCR gene segments are rearranged only in T cells. Third, it is developmental stage specific, occurring only at specific stages of lymphocyte development. Fourth, it is an ordered process in which specific gene segments rearrange at particular developmental stages. For example, in B cells the Ig heavy-chain locus always undergoes rearrangement before the κ and λ light-chain loci. Furthermore, D-to-JH recombination usually precedes VH-D recombination. Finally, successful V(D)J recombination causes feedback regulation that halts further rearrangement of a rearranging locus, so that only one Ig or TCR allele is functionally rearranged in each cell. This aspect of regulation is critical for the phenomenon of allelic exclusion of Ig and TCR genes, which ensures that each lymphocyte expresses TCR or Ig with a single antigen recognition specificity. Given the importance of V(D)J recombination for immune function and the potential hazards of its inappropriate occurrence, the need to understand the mechanisms of its exquisite regulation is obvious.

The lymphoid and developmental stage-specific expression of the RAG1 and RAG2 genes accounts for some regulatory aspects of V(D)J recombination. However, since all Ig and TCR genes have identical RSSs, which are recognized and rearranged by common recombinase enzymes, regulated RAG gene expression cannot account for lineage specificity, ordered rearrangement, or negative feedback (2, 48, 76). A model involving regulated chromatin accessibility has been suggested to account for these aspects of V(D)J recombination regulation (12, 60, 64, 75). The accessibility hypothesis posits that V, D, and J gene segments must acquire an altered chromatin structure which makes them accessible to the recombination enzymatic machinery before they can undergo rearrangement.

Initial support for the chromatin accessibility model came from the observation that rearranging loci in B cells were transcriptionally active at the time of their rearrangement (38, 53, 71, 75). In particular, transcripts from unrearranged gene segments, termed germ line transcripts, were found to initiate upstream of the Ig heavy-chain Cμ constant-region gene segment and upstream of the JH-proximal D gene when the Ig heavy-chain locus was undergoing rearrangement (1, 3, 13) and from the Jκ-Cκ region when the kappa locus rearranged (71). Similarly, germ line V gene transcripts have been observed in the Ig heavy-chain (18, 59, 73, 75), TCRβ, and TCRγ (11, 27, 50) loci and in the TCRγ locus, activation of germ line V transcription is correlated with the ordered rearrangement of these segments during development (25, 27, 30). Furthermore, Schlissel et al. found that introduction of a rearranged μ transgene caused a decrease in endogenous VH germ line transcripts as well as decreased VDJ recombination of the endogenous Ig heavy-chain locus (58).

Additional evidence in support of the accessibility model comes from gene-targeting studies that have revealed an important role for Ig and TCR transcriptional enhancers in V(D)J recombination. Transcriptional enhancers affect chromatin structure (20, 26, 33, 34) and in some cases have locus control region (LCR) activity (19, 21). Deletion of transcriptional enhancers in the Ig heavy-chain Igκ TCRβ, light-chain and TCRα, loci leads in each case to significant reduction of V(D)J recombination in the targeted locus (7, 8, 61, 63, 68). Thus, the strong correlation of V(D)J recombination with the presence of germ line transcripts and transcriptional enhancers supports the chromatin accessibility model.

In spite of these correlations, no definitive role in V(D)J recombination has been established for germ line transcripts or germ line transcription. Several models are possible. First, either the germ line transcripts or polypeptides encoded by the transcripts might act in trans and play a direct role in V(D)J recombination. However, a role for a trans-acting RNA or protein is not consistent with the finding that targeted disruption of the Eμ enhancer inhibited V(D)J recombination in cis but not in trans (13). A second model is that the process of transcription may render the transcribed region more recombinogenic. Consistent with this model, there is evidence that transcription leads to increased recombination between directly repeated sequences of GAL10 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (69). Third, germ line transcription may be required to establish an appropriately accessible chromatin structure for VDJ recombination. Fourth, germ line transcripts may be by-products of an altered, accessible chromatin structure. Finally, germ line transcripts may have no mechanistic relationship to V(D)J recombination. It is important to distinguish among these models, since they make very different predictions about the role of VH gene promoters in regulating V-DJ recombination.

Ig heavy-chain V-DJ recombination occurs only in B cells, while D-J recombination is sometimes observed in T cells, indicating that V-DJ recombination is more stringently regulated than is D-J recombination. Therefore, we reasoned that regulation of germ line VH transcription could be particularly important for regulating Ig heavy-chain VDJ rearrangement. Although murine germ line VH transcripts from the J558 family were first identified in pro-B and pre-B cells more than a decade ago (75), neither the full extent of VH germ line transcription in developing B cells nor its role in VH-DJ recombination is yet known. To achieve a better understanding of the extent, pattern, and role of germ line VH transcription, we developed a sensitive reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay which detects transcripts specific to different VH families and used it to study VH transcription in cell lines lacking the RAG1 or RAG2 gene. Although we observed extensive VH germ line transcription, we found that not all VH families were germ line transcribed in every cell line. By introducing functional RAG genes into different lines, we were able to activate V-DJ recombination. Thus, our system has provided a unique opportunity to compare the ability of both transcribed and nontranscribed germ line VH genes, in their endogenous chromosomal location, to undergo VDJ recombination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of nucleic acids.

Total RNA was prepared by the guanidinium thiocyanate method followed by cesium purification. RNA was further purified with DNase to eliminate contamination with genomic DNA. A 10-μg portion of RNA was digested with 2 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega Biotec, Madison, Wis.) for 30 min at 37°C in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 40 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM CaCl2. The samples were then phenol extracted, ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 10 μl of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA). DNA was prepared for PCR by lysing 106 cells in 100 μl of PCR lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Tween 20, 60 μg of proteinase K per ml), incubating them at 60°C for 1 h, and then inactivating the protease by heating the mixture to 95°C for 10 min. The DNA was then ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 100 μl of TE, and used for PCR at a concentration of 10,000 cells/μl.

RT-PCR assay.

RT-PCR assays were performed on cDNA made by random priming total RNA samples. A 10-μg portion of RNA was reverse transcribed in a reaction mixture containing 25 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MuLV) reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs), 200 pmol of random hexamers, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 20 U of RNasin (Promega Biotec), and 250 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTP) in a final volume of 20 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. cDNA samples were stored frozen at −20°C until used for PCR. A 2-μl volume of cDNA was used in a 100-μl PCR mixture containing 25 pmol of each VH primer (sequences of primers are given in Table 1), 200 μM each dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1× PCR buffer, and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq (Cetus Corp.). The samples were heated to 94°C for 3 min and then subjected to amplification for 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 40°C, and 1 min at 72°C. After the last cycle, a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min was carried out; 35 μl of each PCR mixture was run on a 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The gel was blot-transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham, Arlington Heights), UV cross-linked, and probed with VH-specific CDR2 probes (Table 1) at 42°C in a hybridization solution containing 10% polyethylene glycol, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1.5× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes used in this study

| Primer or probe class | Name | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| VH family specific primers | 7183CDR1 | 5′-ATGTCTTGGGTTCG-3′ |

| 7183CDR2 | 5′-GGTGAATCGGCCCTT-3′ | |

| Q52CDR1 | 5′-AGCTATGGTGTACAC-3′ | |

| Q52CDR2 | 5′-TATGAAAGCTGCATT | |

| S107CDR1 | 5′-CTTCTGGGTTCACCT-3′ | |

| S107CDR2 | 5′-AGATGCATCGTACTC-3′ | |

| SM7CDR1 | 5′-GACTACTATATGCAC-3′ | |

| SM7CDR2 | 5′-CTGGAACTTCGGGTC-3′ | |

| 3660CDR1 | 5′-TACTGGAACTGGATC-3′ | |

| 3660CDR2 | 5′-CTTTTGAGAGATGGA-3′ | |

| V-Gam3/8CDR1 | 5′-CTATGGAATGAACTGG-3′ | |

| V-Gam3/8CDR2 | 5′-CAAACCGTCCCTTGAA-3′ | |

| J606CDR1 | 5′-AACTACTGGATGTCC-3′ | |

| J606CDR2 | 5′-AGACTCCGCATAATG-3′ | |

| V10CDR1 | 5′-ATACCAATGCCATGA-3′ | |

| V10CDR2 | 5′-CTGAATCGGCATAATA-3′ | |

| 3609CDR1 | 5′-ACTTCTGGTATGGGT-3′ | |

| 3609CDR2 | 5′-CAGGGCTGTGTTATA-3′ | |

| J558VaCDR1 | 5′-AACTACTGGGTAGGT-3′ | |

| J558VaCDR2 | 5′-CTTGAACTTCTCATT-3′ | |

| 7183CDR1gene spec. | 5′-TGCCATGTCTTGGGT-3′ | |

| VH1 5′ primers | 5′VH1a | 5′-GCCCAGAGTGACTCT-3′ |

| 5′VH1b | 5′-GGATCCTGTCCTGAG-3′ | |

| Primers for D-J and V-DJ PCR | 5′7183Fr3 | 5′-AAGAASAMCCTGTWCCTGCAATGASC-3′ |

| 5′558Fr3 | 5′-TCCARCACAGCCTWCATGCARCTCARC3′ | |

| 5′Q52Fr3 | 5′-AGACTGARCATCASCAAGGACAAYTCC-3′ | |

| 5′S107CDR2 | 5′-YAACAGAGTACAGTGCATCTRTKAAGGG-3′ | |

| 5′3609CDR2 | 5′-KCYYTGAAGAGCCRRCTCACAATCTCC-3′ | |

| 5′3660CDR2 | 5′-CTCAAAAGTCAATCTCCATCACTCGA-3′ | |

| 5′V-Gam3/8CDR2 | 5′-CAAGGGACGGTTTGCCTTCTCTTTGGAA-3′ | |

| 5′V10CDR2 | 5′-CGCATAAGCCGTAAAAGTARTAATTATGC-3′ | |

| 5′SM7CDR2 | 5′-GGATTGATYCTGMGAATGGTAATGCT-3′ | |

| DHL | 5′-GGAATTCGMTTTTTGTSAAGGGATCTACTACTGTG-3′ | |

| J3 | 5′-GTCTAGATTCTCACAAGAGTCCGATAGACCCTGG-3′ | |

| Probes for PCR products | ||

| 7183P | 5′-AAGAGGCTGGAGTGGGTC-3′ | |

| Q52p | 5′-GATATGGAGTGGTGGAAGCAC-3′ | |

| S107p | 5′-GCAAGTAGAAACAAAGCTAATG-3′ | |

| SM7p | 5′-AGGATTGATCCTGCGAATG-3′ | |

| 3660p | 5′-ATGGGGTACATAAGCTACAGT-3′ | |

| V-GAM3.8p | 5′-TGGATGGGCTGGATAAACAC-3′ | |

| J606p | 5′-GTTGCTCAAATAAGATTGAAATCT-3′ | |

| V10p | 5′-CGCATAAGAAGTAAAAGT-3′ | |

| 3609p | 5′-CTGGCACACATTTGGTGGGAT-3′ | |

| J558p | 5′-CTTGAGTGGATTGGAGATATT-3′ | |

| JH3 | 5′-CCTGGTTTGCTTACTGGG-3′ |

The sequences are presented 5′ to 3′. The degenerate nucleotide positions are coded as follows: R is A or G; Y is C or T; S is C or G; M is A or C; K is G or T; W is A or T; B is C, G, or T.

PCR assay for D-J and V-DJ recombination.

Genomic DNA from 105 cells (10 μl) was PCR amplified in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 100 ng of each primer, 200 μM each dNTP, and 1 U of AmpliTaq. For D-JH rearrangement, the previously described DHL 5′ primer was used (59) with a J3 3′ primer. For V-DJ rearrangement, degenerate primers for specific VH families as previously described (59) (J558, J7183, and Q52) or designed by us (3609, 3660, S107, and V-Gam3/8) (Table 1) were used with a J3 3′ primer. Previously described (59) PCR conditions were used. The samples were heated to 94°C for 3 min and then subjected to amplification for 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C. After the last cycle, a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min was carried out; 25 μl of PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel, transferred, and hybridized with an oligonucleotide homologous to the JH3 gene.

DNA sequencing.

For direct sequencing, PCR products were subjected to cycle-sequencing with the fmol DNA cycle-sequencing system (Promega) and 32P-end-labeled primer. For cloned DNA, PCR products were cloned into plasmid vector pGEMT (Promega), screened by white-blue selection, and sequenced by the double-stranded dideoxy method with the Sequenase 2.0 kit (U.S. Biochemicals) and 35S-dATP.

Cell lines, culture, and transfection.

Bone marrow-derived Abelson MuLV (A-MuLV)-transformed lines from 1-month-old RAG1 mice were established by conventional methods for infection and soft agar cloning by using wild-type A-MuLV carrying the p160 form of v-Abl (54). Abelson virus-transformed pro-B-cell lines were maintained in RPMI plus 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and gentamicin. DNA was introduced into cells lines 1-2 and AH7 (a gift from C. Roman and D. Baltimore) and into the RAG2−/− fetal liver-derived Abelson pro-B-cell line 63-12 (a gift from G. Rathbun and F. Alt) by electroporation. Cell lines were grown to a density of about 5 × 105 cells/ml. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in growth medium at a density of 3 × 107/ml, and 0.3 ml was placed in an electroporation cuvette at room temperature. Then 10 μg of linearized plasmid construct PDR1 or PDR1 carrying RAG1 or RAG2 cDNA (a gift from G. Rathbun) and 2 μg of pBabepuro were added to the cell suspensions; mock transfectants received only pBabepuro DNA. Electroporation was performed in a gene pulser (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) at 280 V and 960 μF capacitance (for 1-2 and AH7 lines) and at 260 V for 63-12; the cells were then placed in 10 ml of normal medium for 2 to 3 days. For selection, 0.5 to 1 μg of puromicin per ml was added to the cell suspension, and after a few days the living cells were plated in 96-well plate at a concentration of 0.5 cell/well. The growth of puromycin-resistant stably transfected clones was noted macroscopically about 3 weeks afterward, and the clones were expanded for subsequent analysis.

RESULTS

Development of an assay for germ line transcripts corresponding to specific VH families.

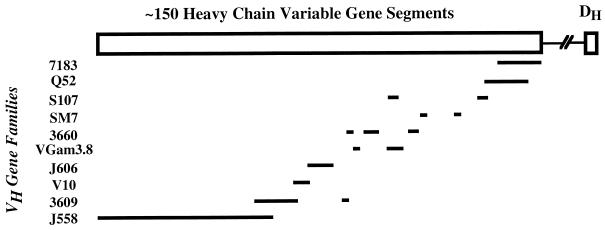

It is estimated that there are 150 to 200 VH gene segments located within a region of approximately ∼2 Mb on murine chromosome 12. They are divided into 15 VH gene families, where a family is defined as consisting of members with at least 80% nucleotide sequence identity. Family size varies from 1 member (V12) to approximately 70 members (J558) (9, 31, 43). Although early studies showed that genes encoding members of different families were physically clustered within the Ig heavy-chain locus (9, 52), subsequent studies have revealed that there is interspersion of some VH families (45, 51) as shown in Fig. 1. More recent studies of overlapping YAC clones of the region show that in C57BL/6 mice the J558 genes are interspersed with genes from small families such as SM7, VGam3/8, and S107 in the central region and that approximately two-thirds of the region most distal from the constant regions is composed enterely of interspersed J558 and 3609P genes (53a).

FIG. 1.

Organization of the murine VH region. The lengths of the lines indicate the estimated numbers of VH genes as described by reference 43.

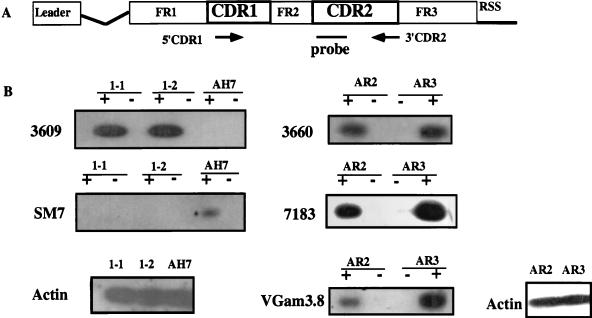

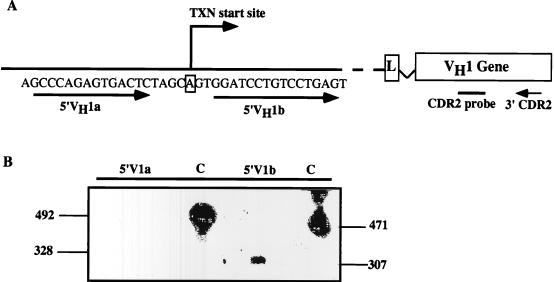

To determine the germ line transcription patterns throughout the murine VH region, we designed an RT-PCR assay that would identify VH family-specific germ line transcripts rather than gene-specific transcripts. The general strategy of this assay is diagrammed in Fig. 2A. Family-specific primers, corresponding to characteristic regions in complementarity-determining region 1 (CDR1) and CDR2 from each of 10 VH families, were designed to amplify VH family-specific transcripts (Table 1). RT-PCR products were detected by blotting and hybridization with an internal family-specific probe from CDR2 (Table 1; Fig. 2A). We chose primers corresponding to the 10 largest VH families, which represent more than 90% of all VH genes. Since the J558 family is large and all members have not been cloned and sequenced, it is likely that transcripts from some J558 family members may not be recognized with our J558 primers and probe; however, for the nine other families, our primers and probes should detect all family members. Since primers from CDR1 and CDR2 do not span an intron, control reactions lacking reverse transcriptase were always included to ensure that the RT-PCR products reflected cDNA rather than contaminating genomic DNA.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR assay for germ line VH transcripts. (A) Diagram of a typical VH gene showing the location of VH family-specific primers (5′CDR1 and 3′CDR2) and probes used in the assay. The primers were 15-base oligonucleotides complementary to the CDR1 and CDR2 regions conserved among family members. (B) Representative results from RT-PCR analysis of lines AR2, AR3, 1-1, 1-2, and AH7. Reactions were performed with 1 μg of total RNA with (+) or without (−) the addition of reverse transcriptase. A control RT-PCR with actin primers was performed for each sample.

Because this assay does not distinguish VH germ line transcripts from VDJ rearranged transcripts, we analyzed Abelson murine leukemia virus (A-MuLV)-transformed pro-B-cell lines derived from RAG1−/− or RAG2−/− mice where V(D)J recombination is completely absent (46, 62). Thus, we are certain that the VH transcripts observed are germ line. Eleven A-MuLV-transformed pre-B-cell lines were analyzed for germ line transcription of 10 VH gene families. AR2, AR3, AR8, and AR19 were derived from bone marrow of 129 RAG2−/− mice; 1-2, 1-1, and AH7 were derived from bone marrow of 129 RAG1−/−-deficient mice; CA1, CA4, and CA5 were derived from bone marrow of C57BL/6 RAG1−/− mice; and 6312 was derived from fetal liver of 129 RAG2−/− mice.

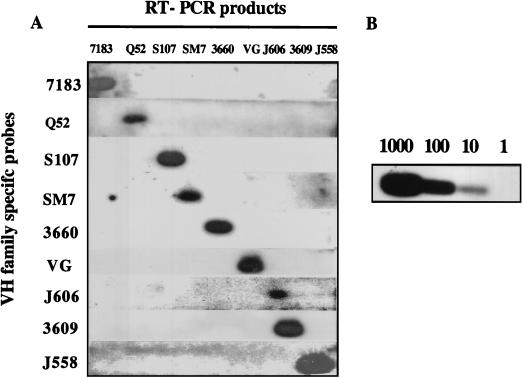

Figure 2B shows representative results from several different cell lines; these data are discussed in the following section. The family specificity of the hybridization step was verified in the following way. RT-PCR products for each VH family were amplified from one of the cell lines which expressed them and blotted on multiple membranes. Duplicate membranes were then hybridized with individual VH family probes. No cross-hybridization with probes corresponding to other VH families was observed (Fig. 3A). To estimate the sensitivity of the assay, dilutions of plasmid DNA encoding the 7183 RT-PCR product were added to a constant amount of cDNA and amplified in our standard PCR assay. As shown in Fig. 3B, 10 copies of 7183 DNA can be detected after hybridization with 7183-specific probe. cDNA obtained from RNA corresponding to 500,000 cells was the amount of template used in our RT-PCR assay. Thus, even allowing for an order of magnitude decrease from the sensitivity of this trial, we would expect to detect a transcript occurring in one copy per cell in every 5,000 cells.

FIG. 3.

Specificity and sensitivity of the RT-PCR assay. (A) Duplicate blots of RT-PCR products derived from the amplification of nine different VH families with 5′CDR1 and 3′CDR2 family-specific primers were hybridized individually with each family-specific VH probe. (B) Dilutions (1,000 to 1 copies) of plasmid DNA encoding a 7183 VH gene were added to a constant amount of cDNA, amplified with 7183 primers, and blotted with a 7183 probe.

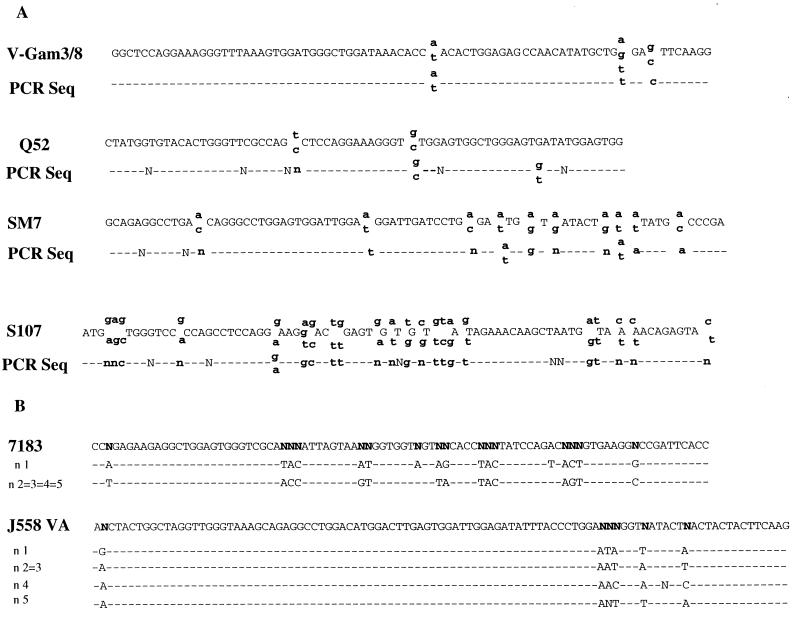

To further verify the specificity of the assay, DNA sequencing was performed on the RT-PCR products from six different VH families (Fig. 4). For the SM7, S107, V-Gam3/8, and Q52 families, which have 3 to 15 members, we performed cycle sequence PCR with the RT-PCR product obtained from one of the expressing lines as template. All of the sequences corresponded to the expected VH family consensus sequences. From cycle sequencing, we found that degeneracy in the sequences occurred at regions where cloned family members are known to differ in sequence from one another (Fig. 4A). For the J558 and 7183 families, which have ∼100 and 19 members, respectively, we cloned the products of each RT-PCR and sequenced several clones. Differences in sequences of different J558 and 7183 clones also corresponded to regions where family members show sequence variation (Fig. 4B). These data confirm that the RT-PCR is family specific and also show that germ line transcripts from multiple members of various VH families are present in our cell lines and can be detected by our assay.

FIG. 4.

DNA sequences of VH RT-PCR products. (A) Cycle sequencing was performed on RT-PCR products obtained from V-Gam3/8, Q52, SM7, and S107 VH families. The consensus sequence of known gene segments is shown in the upper line; the lower line represents the sequence obtained from cycle-sequencing PCR. (B) Sequence from cloned RT-PCR products from the 7183 and J558 families. The consensus sequence for each family is shown in the upper line, and the sequences from individual clones are shown in the lower lines. “N” in the upper line represents nucleotides where members of the family are divergent.

The 10 VH families are germ line transcribed but not in every cell line.

Figure 2B shows representative RT-PCR data. In each blot, cDNAs derived from different A-MuLV lines were tested for transcription of a specific VH family. For instance, the 3609 VH family is transcribed in cell lines 1-1 and 1-2 but not in AH7, and the 3660, 7183, and VGam3.8 families are transcribed both in AR2 and AR3 lines. Control RT-PCR with β-actin primers that do span introns were performed to verify the abundance of cDNA and its lack of contaminating genomic DNA (Fig. 2B). The pattern of germ line VH gene transcription in all of the cell lines is summarized in Table 2. Each cell line had germ line transcripts from at least one VH family. In addition, germ line transcripts corresponding to each VH gene family were found in one or more of the 11 cell lines. However, some lines, such as AR2 and AR3, transcribed many VH gene families, while others, such as CA4 and AH7, transcribed only one or a few families.

TABLE 2.

Summary of germ line VH transcription for 10 families in 11 cell lines

| Cell line | Transcriptiona for family:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 558 | 3609 | V10 | J606 | VG | 3660 | SM7 | S107 | Q52 | 7183 | |

| AR2 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| AR3 | + | + | ND | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| AR8 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| AR19 | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1-1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| 1-2 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| AH7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| CA1 | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| CA4 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CA5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| 6312 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

+, detectable germ line transcription; −, no detectable germ line transcription; ND, not done.

To determine if the pattern of VH germ line transcription correlated with different stages of early B-cell development, the lines were analyzed by flow cytometry for surface expression of B-cell markers which are expressed at particular stages of early B-cell development (29). All of the lines express B220, CD43, and HSA surface markers, and all but 1-2 and AR8 express BP-1. Thus, most lines fall into fraction C of the Hardy classification, while 1-2 and AR8 belong to the earlier stage classified as fraction B (data not shown). Therefore, differences in germ line transcription are not explained by the developmental state of the cells as revealed by these markers. We also considered the possibility that failure to transcribe certain VH families in particular cell lines is due to deletions within the VH locus. However, PCR analysis of genomic DNA showed that VH genes from nontranscribed families were easily detectable (data not shown).

We conclude that in our system, germ line transcription occurs in all cell lines and involves all 10 of the 15 VH gene families which we analyzed. However, the pattern of VH germ line transcription in different pro-B-cell lines is not uniform and cannot be explained by detectable differences in developmental stage, mouse strain, or genomic deletions.

Germ line VH1 transcripts initiate at the same site as rearranged transcripts do.

Primer extension analyses on J558 germ line transcripts suggested that most germ line transcripts initiated at the same site as transcripts for the rearranged gene (75). However, these studies were not designed to determine the transcription initiation site of germ line transcripts from individual genes, and therefore specific initiation sites for germ line versus rearranged genes could not be compared. The steady-state levels of germ line VH transcripts are too low to allow standard analyses by primer extension or S1 nuclease protection assays. Therefore, we used RT-PCR to map the initiation site of germ line transcription from the VH1 gene, where the transcription initiation site of the rearranged gene has been clearly defined (14). VH1 transcripts in RAG2−/− lines were analyzed by RT-PCR with two 5′ primers (5′VH1a and 5′VH1b) which bracket the known transcription start site for the rearranged gene (Fig. 5A). These primers were used with the S107CDR2 3′ primer. After hybridization with a CDR2 internal probe, transcripts were detected with the 5′VH1b primer but not the 5′VH1a primer, suggesting that germ line VH1 transcripts start at the same site as rearranged VH1 transcripts (Fig. 5B). These data are consistent with previous results for J558 (75). This information is important because it means that promoter factors previously identified for rearranged genes are likely to participate in regulation of germ line transcripts. The VH1 promoter is typical of VH promoters in that an octamer site at bp −50 is the most important activator site, although μE3 and C/EBP sites also participate in promoter activity (17, 22).

FIG. 5.

Transcription initiation site of the germ line VH1 transcript. (A) RT-PCR strategy used to detect the transcript start site of the VH1 germ line transcript. The 5′VH1a and 5′VH1b primers were designed to bracket the previously identified transcription start site for the rearranged VH1 gene (14). These primers were used with the S107CDR2 3′ primer (Table 1); PCR products were blotted and probed with an S107CDR2 probe. In this case, the primers span the intron between leader and V exons; PCR products derived from the amplification of cDNA would be 328 and 307 bp for 5′VH1a and 5′VH1b, respectively; 471 bp and 492 bp are the expected sizes of PCR products derived from control amplification of genomic DNA. (B) RT-PCR performed on cDNA derived from the AR2 cell line with 5′VH1a and with 5′VH1b primers. C is a DNA-positive control for PCR.

VH genes which are not germ line transcribed are recombined.

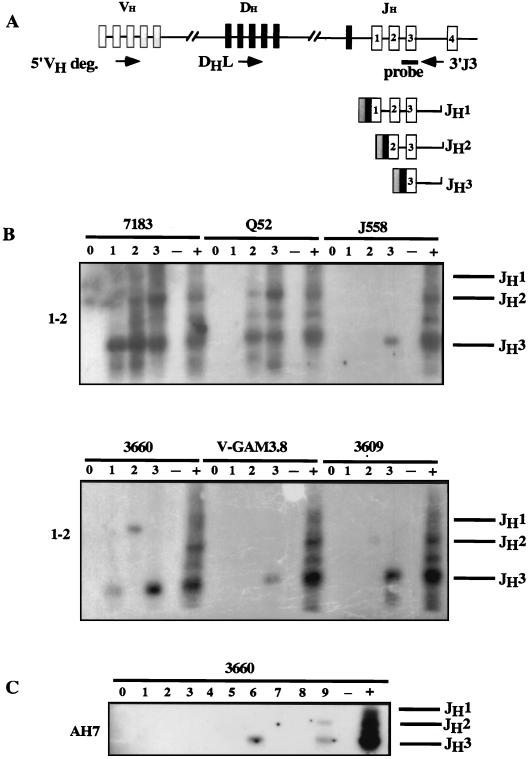

The unexpected observation that endogenous VH gene families are differentially transcribed in individual RAG−/− pro-B-cell lines provided the opportunity to compare V-DJ recombination of transcribed and nontranscribed VH gene segments. We restored RAG activity in these pro-B-cell lines by stably transfecting RAG1 or RAG2 expression plasmids and then analyzed the pattern of V-DJ recombination. VDJ recombination is expected to occur in transfected cell lines because Shinkai et al. have previously shown that ectopic expression of RAG2 in A-MuLV-transformed RAG2−/− pro-B-cells leads to VDJ recombination (62). RAG1 or RAG2 DNA in an expression plasmid dependent upon an Ig heavy-chain V gene promoter and intronic enhancer was stably transfected into the RAG−/− cell lines by using puromycin drug selection. We tried to transfect all the lines and were able to obtain drug-resistant clones from five lines. D-J recombination was used to identify clones with functional RAG protein. Genomic DNA from puromycin-resistant clones was assayed for rearrangement at the JH locus by using a sensitive PCR assay that involves degenerate DHL and J3 primers followed by hybridization with a probe homologous to the JH3 gene segment (Fig. 6A) (59). D-J rearrangements were detected as amplified fragments of 1,033, 716, and 333 nucleotides depending on whether JH1, JH2, or JH3 was rearranged. This assay allowed us to verify that D-J recombination can be activated in these lines by introduction of RAG expression plasmids and to identify subclones in which recombination was occurring. D-J recombination was observed in transfectants from three parental RAG−/− lines: AH7, 1-2, and 63-12 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of lines 1-2, AH7, and 63-12 stably transfected with RAG expression plasmids. (A) Diagram of the PCR strategy used to detect the V-DJ rearrangement (21). The upper line represents a diagram of the unrearranged Ig heavy-chain locus (not drawn to scale). The primers used for the D-J and V-DJ PCR assays are shown by the short arrows. The probe used to hybridize PCR products after blotting is an oligonucleotide homologous to the JH3 coding region. The lower lines represent the sizes of expected PCR products depending on whether JH1, JH2, or JH3 gene segments were used during V-to-DJ joining. (B and C) Representative results showing the products of V-DJ rearrangement revealed by PCR analysis of DNA from the 1-2 (B) and AH7 (C) lines stably transfected with the RAG1 expression plasmid. For 1-2, three subcultures undergoing D-J recombination were tested for rearrangement of six VH families. For AH7, nine subcultures undergoing DJ recombination were tested for rearrangement of the 3660 family. + indicates DNA from normal bone marrow cells used as a positive control; − indicates DNA from untransfected RAG1−/− cells used as a negative control.

Subsequently, subclones undergoing D-J recombination were screened for V-DJ recombination. DNA from these transfected subclones was assayed for V-DJ rearrangement by PCR (Fig. 6A) with the same J3 oligonucleotide as a 3′ primer and oligonucleotides designed to recognize specific VH gene families as 5′ primers. PCR assays were performed to detect rearrangement of nine VH families. We used oligonucleotides homologous to conserved framework region 3 (FR3) for 7183, J558, and Q52 (59) or homologous to the CDR2 region for 3660, V-Gam3/8, S107, 3609, SM7, and V10 (Table 1). As before, three different PCR products are expected determined by rearrangement to JH1, JH2, or JH3 gene segments. Although these “subclones” were originally isolated as drug-resistant single-cell isolates, ongoing D-J and V-DJ rearrangements result in progeny having rearranged different V, D, and J gene segments so that the cultures are no longer clonal. Since the original “subcloned” cultures have been analyzed in bulk without further subcloning, we shall refer to them as subcultures.

Figure 6B shows representative results for VDJ recombination in subcultures of 1-2 and AH7 cell lines, and all of the data are summarized in Table 3. Three subcultures from the parental line 1-2, which contains germ line transcripts from the J558 and 3609 families, were positive for D-J recombination, and V-DJ recombination was also detected in all of these. In all three subcultures of line 1-2, we observed rearrangement of VH families which were not germ line transcribed in the parental 1-2 line. Specifically, rearrangement of the 7183 family was observed in all three subcultures, rearrangement of the Q52 family was observed in two subcultures, rearrangement of the 3660 family was observed in all three, and rearrangement of V-Gam3/8 was observed in one. In addition, rearrangement of germ line transcribed VH families J558 and 3609 was also observed in some but not all subcultures, suggesting that VH germ line transcription neither activates nor inhibits V-DJ recombination. Rearrangement of the S107, SM7, and V10 families was not detected.

TABLE 3.

Patterns of V-DJ rearrangement in three lines which had functional RAG gene expression indicated by D-J rearrangement

| Cell line | Culture | Transcription patterna or V-DJ rearrangementb for family:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 558 | 3609 | V10 | 3660 | SM7 | VG | S107 | Q52 | 7183 | ||

| 1-2 | P | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | |

| 2 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 3 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| AH7 | P | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 1 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 6312 | P | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | |

| 2 | +* | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 3 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | |

| 4 | +* | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| 5 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 6 | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | |

The germ line transcription pattern of the parental (P) line before expression of RAG protein is indicated by + or − at the top of each series.

Numbers 1 to 6 indicate subcultures positive for V-DJ rearrangement after expression of RAG protein. The families which were positive for V-DJ rearrangement in different subcultures are indicated by +, and those for which no V-DJ rearrangement was detected are indicated by −. The primer used for J558 rearrangement can also anneal to SM7 genes, although the 5′ primer for SM7 is specific for SM7. Since the two subcultures indicated by * are positive for SM7 rearrangement, the positive signal obtained with the J558 primers may represent either SM7 or J558.

The parental line 63-12 contains germ line transcripts of V10, J558, and 3609 VH gene families. Six subcultures of 63-12 had V-DJ rearrangement, and rearrangement of non-germ line transcribed families was even more striking in these cultures. Rearrangement of 7183 and Q52 families was found in all six subcultures, rearrangement of S107 occurred in three, rearrangement of 3660 occurred in two, rearrangement of V-Gam3/8 occurred in four, rearrangement of V10 occurred in three, and rearrangement of SM7 occurred in two. A third parental line, AH7, displayed a more limited pattern of germ line VH transcription, since only SM7 family transcripts were detected. Only two of nine D-J-positive AH7 subcultures had detectable V-DJ recombination. In both subcultures, the 3660 VH family was rearranged, although it was not germ line transcribed (Table 3). No other VH family was rearranged.

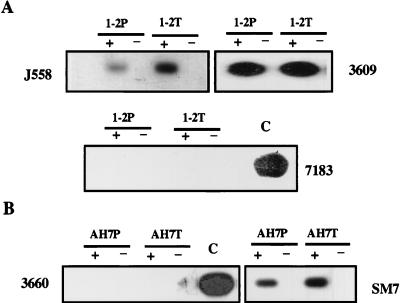

We wished to determine if the original pattern of VH germ line transcription was stable following many passages in culture and the manipulations involved in transfection and selection. Mock transfectants carrying only the puromycin selectable marker were analyzed. As shown in Fig. 7, we saw that germ line transcription patterns remained constant throughout the transfection process. For example, line AH7 does not transcribe 3660 but does transcribe SM7 both before and after transfection. Similarly, line 1-2 transcribes J558 and 3609 but not 7183 (Fig. 7) or Q52 (data not shown) before and after transfection. For the 1-2 cell line, a total of eight independent mock-transfected lines were analyzed and the pattern of germ line transcription was maintained in all eight (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Stability of the VH germ line transcription pattern. (A) VH germ line transcripts revealed by RT-PCR of cDNA from the 1-2 cell line before (1-2P) and after (1-2T) mock transfection with the drug-selectable plasmid. (B) 3660 and SM7 VH germ line transcripts in the AH7 line before (AH7P) and after (AH7T) mock transfection with the drug-selectable plasmid. All reactions were carried out with (+) or without (−) reverse transcriptase.

These results show that VH genes which were not germ line transcribed were, nevertheless, rearranged. However, a trivial explanation for our data might be that germ line transcription of certain family members was not detected in our original RT-PCR assay because the family-specific primers used did not anneal efficiently to particular VH gene sequences. To rule out this possibility, we sequenced a 7183 gene which was rearranged in a subculture of the 1-2 line. The sequence revealed 1-bp mismatch with the 5′ primer used in the RT-PCR assay; the 3′ primer matched exactly. We therefore designed a new 5′ primer which matched the rearranged 7183 gene perfectly and used this primer in the RT-PCR assay to search for germ line transcription of the rearranged 7183 gene in a mock-transfected subculture from the 1-2 line. No germ line transcript was detected (Fig. 7A). Thus, we conclude that endogenous VH genes for which germ line transcripts are undetectable in our sensitive RT-PCR assay are able to undergo V-DJ recombination.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a sensitive RT-PCR assay to detect VH germ line transcription in pro-B-cell lines from RAG-deficient mice. Germ line transcription was evaluated for 10 VH families which encode more than 90% of all VH genes (31). Extensive germ line VH transcription was observed. Although all 10 VH families were germ line transcribed and each of 11 different pro-B-cell lines contained VH germ line transcripts, there was a surprising lack of uniformity in the number and family distribution of germ line transcripts in individual cell lines. When the missing RAG proteins were supplied by stable transfection of RAG expression plasmids, V(D)J recombination was restored in three cell lines. This experimental system provided a unique opportunity to compare the germ line transcription pattern and V-DJ recombinational activity of endogenous VH genes. Analysis of RAG transfectants undergoing V(D)J recombination showed that endogenous VH genes for which germ line transcripts were undetectable in the parental cell lines were V-DJ joined. Thus, in this system, germ line transcription of recombining endogenous VH genes, as detected by our assay, is not required for VH-DJ recombination. Our working model is that accessible chromatin structure in the VH region, but not transcription of particular VH genes, is required for VH-DJ recombination.

VH germ line transcription is not uniform in different cell clones.

Our data show that 10 of 15 VH families, representing more than 90% of all VH genes, are germ line transcribed in pro-B cells. All of the pro-B-cell lines we studied displayed germ line VH transcripts, and all but one had germ line transcripts from two or more VH families. Thus, in pro-B cells, germ line transcription is not limited to the J558 family but appears to be widespread throughout the VH region. Based on these data, it seems likely that all VH genes may be germ line transcribed in some B-cell clones during B-cell lymphopoiesis. Germ line transcripts from the large J558 family were first reported in 1985 by Yancopoulos and Alt (75). Although these authors mentioned the presence of weak signals from other VH families, they did not investigate them further. Subsequently, many laboratories confirmed the occurrence of germ line J558 transcripts in pro-B cells (39, 59, 73), and germ line transcripts corresponding to 81X, a member of the 7183 VH family (18) but not other murine VH families, have been reported. However, more extensive germ line VH transcription has recently been reported in human fetal liver, where germ line transcription of six VH families was observed (37). Our data confirm and expand these previous studies.

A striking finding of the present study was the nonuniform pattern of germ line VH gene transcription observed in the 11 RAG-deficient pro-B-cell lines analyzed (Table 2). We also observed that the germ line transcription pattern in different cell lines was stable over many cell doublings and was not altered by transfection and drug selection. We are unable to account for the observed differences among clonal lines by differences in developmental stage as evidenced by expression of cell surface markers commonly used to identify early stages of B-cell development in the bone marrow, by differences in mouse strain, or by trivial explanations such as deletion of portions of the VH region. However, there may be subtle developmental or phenotypic differences in the lines, which we have not been able to detect.

Since our data provide multiple examples of VH genes which are not germ line transcribed but which are located in a region flanked on both sides by VH families which are germ line transcribed (i.e., SM7 in line AR3, J606 and V10 in line AR19, S107 in line 1-1, and SM7 and 3660 in line CA1), it seems unlikely that differential transcription is conferred by accessible chromatin structure, although we cannot rule out the possibility that the chromatin structure is regulated in very small domains. It seems more likely that accessible chromatin is necessary but not sufficient for VH germ line transcription. Activation of individual VH promoters may occur by a stochastic process. All VH promoters that have been analyzed depend primarily on Oct sites (6, 28, 44). If Oct-1, Oct-2, OCA-B, or another protein required for activation of VH promoters is limiting in pro-B cells, it would mean that even if the chromatin structure were permissive for transcription, not all VH genes could be transcribed. It may also be that once transcription from a particular VH promoter is activated, it remains activated throughout subsequent cell divisions. An alternative explanation is that individual VH gene promoters may be specifically regulated. This would be consistent with a report that two VH promoters have different strengths in vitro (10). However, our data do not support a model in which particular promoters are stronger in vivo, because we did not find a specific VH family which was preferentially germ line transcribed. Although we cannot rule out a model in which germ line transcription of individual VH gene promoters is a regulated event, the fundamental similarity of the VH promoters and the lack of any apparent physiological rationale for such regulation argue against it.

It is also interesting that we did not observe preferential germ line transcription of D-proximal 7183 and Q52 gene families. In vivo, these genes are preferentially rearranged early in B-cell ontogeny (77), and in two of three cell lines where RAG gene expression restored VDJ recombination, 7183 VH genes were frequently rearranged (Table 3). It may be that preferential rearrangement of these VH genes reflects other aspects of the VDJ recombination mechanism, possibly related directly to their proximity to D-gene segments or differences in their RSSs. This possibility is supported by a recent study showing that a 7183 RSS recombines more frequently than a J558 RSS in vitro (16).

We cannot identify precisely which regions of VH are germ line transcribed in our cell lines, because the ∼2-Mb region has been only partially characterized. Early studies involving hybridization kinetics led to an estimate of more than 1,000 VH genes; however, more recent mapping studies suggest the existence of 100 to 200 VH genes. Analysis of a set of overlapping YAC clones from C57BL/6 mice, which encompasses the VH region, has revealed that the 7183, Q52, S107, SM7, and 3660 families are clustered in the D-proximal portion of the region and that J558 and 3609P genes are interspersed throughout more than two-thirds of the VH region (53a). Germ line transcription of either 3609 or J558 family genes was observed in 10 of 11 pro-B-cell lines analyzed. Since sequence analysis of the RT-PCR products from six VH families, including J558, showed that multiple family members were germ line transcribed, it is reasonable to speculate that transcription occurs throughout much, possibly all, of the region occupied by J558 or 3609 family members in the 10 lines where J558 or 3609 germ line transcripts were observed. Thus, our data show extensive germ line transcription in the VH region. Germ line transcription is one indicator of open or accessible chromatin structure. Extensive germ line transcription is consistent with a model in which much of the 2-Mb VH region chromatin becomes accessible in pro-B cells. These changes in chromatin structure may be controlled by locus control elements (19, 42) within the VH region or by similar regulatory elements which affect the structure of large regions of chromatin.

Rearrangement of a VH gene segment does not require its germ line transcription.

Our data are consistent with previous reports suggesting that germ line transcription does not correlate with or is not required for V(D)J recombination (5, 32, 49). However, in these studies the recombination substrates used were either transiently transfected genes (32) or transgenes (5, 49). For example, Okada et al. (49) found that Vβ transgenes were transcribed but not rearranged in B cells, suggesting that transcription was not sufficient for VDJ recombination. In addition, using transgene substrates, Alvarez et al. (5) observed similar recombination of two Vβ genes, one containing and one lacking an active promoter, suggesting that transcription is not required for recombination. However, since the chromatin structure of the rearranging gene segments is likely to be a critical determinant for recombination and since the chromatin structure of transfected genes or transgenes may differ significantly from that of endogenous genes, it is difficult to draw unambiguous conclusions from these studies. By analyzing the recombination of endogenous VH genes, our experiments remove the potential problem of artifactual chromatin structure. Our data show that easily detectable levels of germ line transcription do not favor V-DJ recombination of particular VH genes. Our data also provide multiple examples of V-DJ recombination in the absence of detectable germ line transcription. Of course, no experiment can rule out completely the possibility that VH germ line transcription immediately precedes V-DJ recombination in the rare cells in which recombination occurs and that the transcripts were undetected because of low levels or instability. However, our assay is very sensitive, and we estimate that we would detect one transcript in approximately 5,000 cells. We also cannot rule out the formal possibility that specific germ line VH transcription occurred but was repressed upon A-MuLV transformation. This seems unlikely since these A-MuLV cell lines do express germ line transcripts from many VH genes. Thus, our data complement and extend previous studies, providing strong support for the idea that germ line transcription is not required for V-DJ rearrangement of a particular VH gene in its endogenous chromosomal location.

Considering our evidence of extensive germ line transcription prior to VDJ rearrangement (Table 2) but no requirement for germ line transcription for rearrangement of a particular VH gene (Table 3) and the previous studies from many other laboratories (60, 64), our working model is that while altered chromatin structure is required for V-DJ rearrangement, VH germ line transcription of the rearranging VH gene is not required for V-DJ rearrangement. It seems likely that VH germ line transcription is a secondary consequence of altered chromatin structure, but we cannot rule out the possibility that VH germ line transcription, somewhere within the VH region, is required to establish the required chromatin structure.

If rearrangement of a VH gene does not require its germ line transcription, this rules out a VH gene-specific role for either the germ line mRNA or a polypeptide encoded by the germ line mRNA in the process of V-DJ recombination. (The possibility remains that VH germ line transcripts or polypeptides, not specific for a particular VH gene, play a role in V-DJ recombination.) It also rules out the interesting idea that the process of transcription is required to transiently melt the DNA, making a specific gene segment a better substrate for VDJ recombination. Lack of a specific requirement for transcription is consistent with the fact that there is no apparent requirement for transcription proteins or NTPs when VDJ cleavage (65) or cleavage and joining (40) reactions are reconstituted in vitro. Lack of a requirement for germ line transcription is one of several features of the V(D)J recombination mechanism which is different from the mechanism of isotype switch recombination, since germ line transcription appears to be required for the latter DNA rearrangement (15, 55, 66, 74).

In several previous studies, transcription of particular Vγ or Vλ genes has been highly correlated with their recombination (27, 67). There is also a report in which T-cell-specific V-DJ recombination of a transgenic substrate was determined by the V-gene promoter (23). Although these data strongly suggest that transcription is required for rearrangement of a V gene, they do not prove it. Developmentally regulated transcription of different Vγ or Vλ genes may reflect developmentally regulated accessibility of chromatin, which would not be inconsistent with our data. There are also important differences in the experimental systems used, which may influence the outcomes of the different studies. The transgenic recombination substrates used by Ferrier et al. (23, 24) may have different chromatin structure and regulatory requirements for V-DJ recombination than endogenous genes. Our studies were carried out with A-MuLV-transformed cell lines, which may have altered expression of some genes compared to normal pro-B cells. Finally, it is possible, although we consider it unlikely, that regulation of TCR and Ig heavy-chain V(D)J recombination is different. Further experiments, probably involving gene targeting, are necessary to resolve these issues.

Gene-targeting studies have clearly demonstrated that deletions of transcriptional enhancer elements in the Ig heavy-chain (61), Igκ (68), TCRβ (7, 8), and TCRα (63) loci cause a decrease in V(D)J recombination, establishing the importance of these elements for optimal V(D)J recombination. Our study does not support the theory that these elements could enhance V(D)J recombination by activating germ line transcription of rearranging gene segments prior to V(D)J rearrangement. However, our results do support models in which enhancers alter chromatin structure or participate in other aspects of VDJ recombination. In support of these possibilities, previous studies have shown that enhancers alter chromatin structure (33, 35) and may have LCR activity (19, 42). One study involving the rabbit kappa enhancer (36) showed that enhancement of VJ recombination could be separated from enhancement of transcription. In addition, there is recent evidence that in mice lacking the TCRβ enhancer, double-strand breaks are normal but coding joins do not form, suggesting that this enhancer plays a role in the joining phase of V(D)J recombination (57a). Therefore, transcriptional enhancers may enhance recombination in a way which is independent of transcription, which would be completely consistent with our results.

If, as we suggest, accessible chromatin structure but not germ line transcription is required for rearrangement of a particular V gene, further understanding of how V-DJ rearrangement is regulated should focus on regions such as LCRs, which may regulate chromatin structure in the 2-Mb VH region, rather than on promoters for particular VH genes. We are beginning a thorough analysis of the chromatin structure of different VH genes in our RAG−/− pro-B-cell lines with a variety of probes for chromatin structure. By comparing the chromatin structure in the VH region with the known V-DJ rearrangement pattern in the different lines, we should be able to obtain a more detailed understanding of if or how various features of VH gene chromatin structure correlate with subsequent V-DJ rearrangement. In addition, this analysis will help us determine if subdomains of the 2-Mb VH region are differentially regulated at the level of chromatin structure and, if so, should help to identify the boundaries of such subdomains. The limited pattern of germ line transcription and VH gene rearrangement in line AH7 is consistent with the possibility that subdomains of VH region chromatin are individually regulated, and this is supported by a recent report showing that substrate accessibility at the 5′ end of the Ig heavy-chain locus is controlled separately from that at the 3′ end (18).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to A. Henderson, P. Rothman, and C. Tunyaplin for critically reading the manuscript and to members of the Calame laboratory for many helpful discussions. We thank K. Merrell for lines AR2, AR3, AR8, and AR19; C. Roman and D. Baltimore for lines 1-1, 1-2, and AH7; and G. Rathbun and F. Alt for lines 63-12 and RAG expression vectors PDR1 and PDR2.

This work was supported by grant RO1 GM29361 to K.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessandrini A, Desiderio S V. Coordination of immunoglobulin DJH transcription and D-to-JH rearrangement by promoter-enhancer approximation. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2096–2107. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alt F W, Oltz E M, Young F, Gorman J, Taccioli G, Chen J. VDJ recombination. Immunol Today. 1992;13:306–314. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alt F W, Rosenberg N, Enea V, Siden E, Baltimore D. Multiple immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene transcripts in Abelson murine leukemia virus-transformed lymphoid cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:386–400. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.4.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alt F W, Blackwell T, Yancopoulos G. Development of the primary antibody repertoire. Science. 1987;238:1079–1087. doi: 10.1126/science.3317825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez J D, Anderson S J, Loh D Y. V(D)J recombination and allelic exclusion of a TCR beta-chain minilocus occurs in the absence of a functional promoter. J Immunol. 1995;155:1191–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard D W, Bothwell A. Mutational analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain promoter region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9626–9630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bories J C, Demengeot J, Davidson L, Alt F W. Gene-targeted deletion and replacement mutations of the T-cell receptor beta-chain enhancer: the role of enhancer elements in controlling V(D)J recombination accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7871–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvier G, Watrin F, Naspetti M, Verthuy C, Naquet P, Ferrier P. Deletion of the mouse T-cell receptor beta gene enhancer blocks alphabeta T-cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7877–7881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodeur P H, Osman G E, Mackle J J, Lalor T M. The organization of the mouse IgH-V locus. Dispersion, interspersion, and the evolution of Vh gene family clusters. J Exp Med. 1988;168:2261–2278. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.6.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchanan K L, Hodgetts S I, Byrnes J, Webb C F. Differential transcription efficiency of two Ig VH promoters in vitro. J Immunol. 1995;155:4270–4277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candeias S, Hardy R R, Li Y S, Staerz U D. T cell receptor V beta 8.2 gene germ-line transcription: an early event of lymphocyte differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3073–3081. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Alt F W. Gene rearrangement and B-cell development. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:194–200. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90004-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Young F, Bottaro A, Stewart V, Smith R K, Alt F W. Mutations of the intronic IgH enhancer and its flanking sequences differentially affect accessibility of the JH locus. EMBO J. 1993;12:4635–4645. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke C, Berenson J, Goverman J, Boyer P, Crews S, Siu G, Calame K. An immunoglobulin promoter region is unaltered by DNA rearrangement and somatic mutation during B-cell development. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7731–7749. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.23.7731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cogne M, Lansford R, Bottaro A, Zhang J, Gorman J, Young F, Cheng H L, Alt F W. A class switch control region at the 3′ end of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Cell. 1994;77:737–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connor A M, Fanning L J, Celler J W, Hicks L K, Ramsden D A, Wu G E. Mouse VH7183 recombination signal sequences mediate recombination more frequently than those of VHJ558. J Immunol. 1995;155:5268–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper C L, Johnson D, Roman C, Avitahl N, Tucker P, Calame K. The C/EBP family of transcriptional activators is functionally important for Ig VH promoter activity in vivo and in vitro. J Immunol. 1992;149:3225–3231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corcoran A, Riddell A, Krooshoop D, Venkitaraman A R. Impaired immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in mice lacking the IL-7 receptor. Nature. 1998;391:904–907. doi: 10.1038/36122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz P, Cado D, Winoto A. A locus control region in the T cell receptor α/δ locus. Immunity. 1994;1:207–217. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon N, Grosveld F. Transcriptional regulation of multigene loci: multilevel control. Trends Genet. 1993;9:134–137. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon N, Grosveld F. Chromatin domains as potential units of eukaryotic gene function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:260–264. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton S, Calame K. Multiple DNA sequence elements are necessary for the function of an immunoglobulin heavy chain promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrier P, Krippl B, Blackwell K, Furley A J, Suh H, Winoto A, Cook W, Hood L, Costantini F, Alt F. Separate elements control DJ and VDJ rearrangement in a transgenic recombination substrate. EMBO J. 1990;9:117–125. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrier P, Covey L R, Suh H, Winoto A, Hood L, Alt F W. T cell receptor DJ but not VDJ rearrangement within a recombination substrate introduced into a pre-B cell line. Int Immunol. 1989;1:66–74. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fondell J D, Marcu K B. Transcription of germ line V alpha segments correlates with ongoing T-cell receptor alpha-chain rearrangement. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1480–1489. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forrester W C, van Genderen C, Jenuwein T, Grosschedl R. Dependence of enhancer-mediated transcription of the immunoglobulin mu gene on nuclear matrix attachment regions. Science. 1994;265:1221–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.8066460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldman J P, Spencer D M, Raulet D H. Ordered rearrangement of variable region genes of the T cell receptor gamma locus correlates with transcription of the unrearranged genes. J Exp Med. 1993;177:729–739. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosschedl R, Baltimore D. Cell-type specificity of immunoglobulin gene expression is regulated by at least three DNA sequence elements. Cell. 1985;41:885–897. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy R R, Carmack C E, Shinton S A, Kemp J D, Hayakawa K. Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1213–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holman P O, Roth M E, Huang M, Kranz D M. Characterization of transcripts from unrearranged V alpha 8 genes in the thymus. J Immunol. 1993;151:1959–1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honjo T, Matsuda F. Immunoglobulin heavy chain loci in mouse and human. In: Honjo T, Alt F, editors. Immunoglobulin genes. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsieh C L, McCloskey R P, Lieber M R. V(D)J recombination on minichromosomes is not affected by transcription. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15613–15619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenuwein T, Forrester W, Grosschedl R. Role of enhancer sequences in regulating accessibility of DNA in nuclear chromatin. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:97–103. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenuwein T, Forrester W, Qiu R, Grosschedl R. The immunoglobulin mu enhancer core establishes local factor access in nuclear chromatin independent of transcriptional stimulation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2016–2032. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenuwein T, Forrester W C, Fernandez-Herrero L A, Laible G, Dull M, Grosschedl R. Extension of chromatin accessibility by nuclear matrix attachment regions. Nature. 1997;385:69–72. doi: 10.1038/385269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kallenbach S, Babinet C, Pournin S, Cavelier P, Goodhardt M, Rougeon F. The intronic immunoglobulin kappa gene enhancer acts independently on rearrangement and on transcription. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1917–1921. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenig N, Malone B, Hoch S, Schwaber J. Transcription of germline VH gene elements by normal human fetal liver. Mol Immunol. 1997;34:333–341. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lennon G G, Perry R. Cu-containing transcripts initiate heterogeneously within the IgH enhancer region and contain a novel 5′ nontranslatable exon. Nature. 1985;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/318475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lennon G G, Perry R P. The temporal order of appearance of transcripts from unrearranged and rearranged Ig genes in murine fetal liver. J Immunol. 1990;144:1983–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leu T M, Eastman Q M, Schatz D G. Coding joint formation in a cell-free V(D)J recombination system. Immunity. 1997;7:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis S M. The mechanism of V(D)J joining: lessons from molecular, immunological, and comparative analyses. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:27–150. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madisen L, Groudine M. Identification of a locus control region in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus that deregulates c-myc expression in plasmacytoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2212–2226. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.18.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mainville C A, Sheehan K M, Klaman L D, Giorgetti C A, Press J L, Brodeur P H. Deletional mapping of fifteen mouse VH gene families reveals a common organization for three Igh haplotypes. J Immunol. 1996;156:1038–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mason J O, Williams G T, Neuberger M S. Transcription cell type specificity is conferred by an immunoglobulin Vh gene promoter that includes a functional consensus sequence. Cell. 1985;41:479–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meek K, Rathbun G, Reininger L, Jaton J C, Kofler R, Tucker P W, Capra J D. Organization of the murine immunoglobulin VH complex: placement of two new VH families (VH10 and VH11) and analysis of VH family clustering and interdigitation. Mol Immunol. 1990;27:1073–1081. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(90)90095-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson R S, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou V E. Rag-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;65:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oettinger M A, Schatz D G, Gorka C, Baltimore D. RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination. Science. 1990;248:1517–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.2360047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okada A, Alt F W. Mechanisms that control antigen receptor variable region gene assembly. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:185–196. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okada A, Mendelsohn M, Alt F. Differential activation of transcription versus recombination of transgenic T cell receptor beta variable region gene segments in B and T lineage cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:261–272. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pardoll D M, Fowlkes B J, Lechler R I, Germain R N, Schwartz R H. Early genetic events in T cell development analyzed by in situ hybridization. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1624–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.6.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pennell C A, Mercolino T J, Grdina T A, Arnold L W, Haughton G, Clarke S H. Biased immunoglobulin variable region gene expression by Ly-1 B cells due to clonal selection. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:1289–1295. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rathbun G A, Capra J D, Tucker P W. Organization of the murine immunoglobulin VH complex in the inbred strains. EMBO J. 1987;6:2931–2937. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reth M, Alt F W. Novel immunoglobulin heavy chains are produced from DJH gene segment rearrangements in lymphoid cells. Nature. 1984;312:418–423. doi: 10.1038/312418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53a.Riblet, R. Personal communication.

- 54.Rosenberg N, Baltimore D, Scher C D. In vitro transformation of lymphoid cells by Abelson murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothman P, Chen Y Y, Lutzker S, Li S C, Stewart V, Coffman R, Alt F W. Structure and expression of germ line immunoglobulin heavy-chain epsilon transcripts: interleukin-4 plus lipopolysaccharide-directed switching to C epsilon. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1672–1679. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schatz D G, Oettinger M A, Baltimore D. The V(D)J recombination activating gene, RAG-1. Cell. 1989;59:1035–1048. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schatz D G, Oettinger M A, Schlissel M S. V(D)J recombination: molecular biology and regulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:359–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57a.Schlissel, M. Personal communication.

- 58.Schlissel M, Morrow T. Ig heavy chain protein controls B cell development by regulating germ-line transcription and retargeting V(D)J recombination. J Immunol. 1994;153:1645–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schlissel M, Corcoran L, Baltimore D. Virus-transformed pre-B cells show ordered activation but not inactivation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and transcription. J Exp Med. 1991;173:711–720. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schlissel M S, Stanhope-Baker P. Accessibility and the developmental regulation of V(D)J recombination. Semin Immunol. 1997;9:161–170. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Serwe M, Sablitzky F. V(D)J recombination in B cells is impaired but not blocked by targeted deletion of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intron enhancer. EMBO J. 1993;12:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam K-P, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall A, Alt F. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sleckman B P, Bardon C G, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Alt F W. Function of the TCR alpha enhancer in alphabeta and gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sleckman B P, Gorman J R, Alt F W. Accessibility control of antigen-receptor variable-region gene assembly: role of cis-acting elements. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stanhope-Baker P, Hudson K M, Shaffer A L, Constantinescu A, Schlissel M S. Cell type-specific chromatin structure determines the targeting of V(D)J recombinase activity in vitro. Cell. 1996;85:887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stavnezer-Nordgren J, Sirlin S. Specificity of immunoglobulin heavy chain switch correlates with activity of germline heavy chain genes prior to switching. EMBO J. 1986;5:95–102. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stiernholm N B, Berinstein N L. A mutated promoter of a human Ig V lambda gene segment is associated with reduced germ-line transcription and a low frequency of rearrangement. J Immunol. 1995;154:1748–1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takeda S, Zou Y R, Bluethmann H, Kitamura D, Muller U, Rajewsky K. Deletion of the immunoglobulin kappa chain intron enhancer abolishes kappa chain gene rearrangement in cis but not lambda chain gene rearrangement in trans. EMBO J. 1993;12:2329–2336. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas B J, Rothstein R. Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell. 1989;56:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Ness B, Weigert M, Coleclough C, Mather E, Kelley D, Perry R. Transcription of the unrearranged mouse Ck locus: sequences of the initiation region and comparison of activity with a rearranged Vk-Ck gene. Cell. 1981;27:593–602. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weaver D, Boubnov N, Wills Z, Hall K, Staunton J. V(D)J recombination: double-strand break repair gene products used in the joining mechanism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;764:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb55811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Webb C, Dou S, Buchanan K, Resta R, Smithson G, Smith E. Reassessment of germline heavy chain transcripts from two murine VH families. Mol Immunol. 1997;34:743–750. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu L, Gorham B, Li S C, Bottaro A, Alt F W, Rothman P. Replacement of germ-line epsilon promoter by gene targeting alters control of immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3705–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yancopoulos G, Alt F. Developmentally controlled and tissue-specific expression of unrearranged VH gene segments. Cell. 1985;40:271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yancopoulos G, Alt F. Regulation of assembly and expression of variable-region genes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:339–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yancopoulous G D, Malynn B A, Alt F W. Developmentally regulated and strain-specific expression of murine Vh gene families. J Exp Med. 1988;168:417–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.1.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]