Key Points

Question

Is there a survival benefit of combining immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) plus chemotherapy in patients 75 years and older with acceptable risk status and previously untreated advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)?

Findings

In this case series of older adults with NSCLC, no significant difference in overall survival or progression-free survival between ICI plus chemotherapy and ICI therapy alone was found before or after propensity score matching, but grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events were more frequent in the former group.

Meaning

Based on data from clinical practice, ICI alone may be recommended for older adult patients with programmed death–ligand 1–positive NSCLC.

Abstract

Importance

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) plus chemotherapy combination treatment (ICI-chemotherapy) is now a standard treatment for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without targetable oncogene alterations, but there are few data on ICI-chemotherapy for patients 75 years and older.

Objective

To inform the choice of first-line drugs in clinical practice and assess the safety and efficacy of ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment in older adult patients with previously untreated advanced NSCLC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included 58 centers in Japan. The cohort consisted of patients 75 years and older with clinical stage IIIB, IIIC, IV, postoperative or radiotherapy recurrent NSCLC. Patients started first-line systemic therapy between December 2018 and March 2021. Those receiving first-line molecular targeted drugs were excluded. The data were analyzed from February 2022 to October 2022.

Exposures

Systemic therapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and safety.

Results

A total of 1245 patients (median [range] age, 78 [75-95] years; 967 [78%] male) with NSCLC were included in the cohort. Programmed death ligand–1 (PD-L1) expression of less than 1% occurred in 268 tumors (22%); 1% to 49% in 387 tumors (31%); 50% and higher in 410 tumors (33%), and unknown expression in 180 tumors (14%). Median OS was 20.0 (95% CI, 17.1-23.6) months for the 354 patients receiving ICI-chemotherapy (28%); 19.8 (95% CI, 16.5-23.8) months for the 425 patients receiving ICI alone (34%); 12.8 (95% CI, 10.7-15.6) months for the 311 patients receiving platinum-doublet chemotherapy (25%); and 9.5 (95% CI, 7.4-13.4) months for the 155 patients receiving single-agent chemotherapy (12%). After propensity score matching, no differences in OS and PFS were found between the patients receiving ICI-chemotherapy vs ICI alone. Each group consisted of 118 patients. For PD-L1 expression of 1% and higher the OS hazard ratio (HR) was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.67-1.42; P = .90), and the PFS HR was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.67-1.25; P = .59). Significance was also not reached when separately analyzed for lower or higher PD-L1 expression (1%-49% or ≥50%). However, grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events occurred in 86 patients (24.3%) treated with ICI-chemotherapy and 76 (17.9%) with ICI alone (P = .03).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment did not improve survival and increased the incidence of grade 3 and higher immune-related adverse events compared with ICI alone in patients 75 years and older. Based on these results, ICI alone may be recommended for older adult patients with PD-L1–positive NSCLC.

This case series assesses overall and progression-free survival and safety outcomes of chemotherapy and immunotherapy combination treatment in patients 75 years and older with non–small cell lung cancer.

Introduction

The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) represents a breakthrough in the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without targetable oncogene alterations. Blockade of programmed cell death–1 and its ligand (PD-L1) resulted in improved overall survival (OS) compared with chemotherapy in the first-line and second-line settings. Subsequent phase 3 studies showed that the addition of pembrolizumab to platinum-doublet chemotherapy resulted in longer OS and progression-free survival (PFS) than chemotherapy alone, regardless of the level of PD-L1 expression by the tumor. There are now more first-line treatment options, including a combination of programmed cell death–1 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 inhibitors with or without chemotherapy.

However, patients 75 years and older were seldom included in these phase 3 trials. Thus, patients of this age represented only 9% and 11% of cases in KEYNOTE-189 and IMpower130, respectively. Furthermore, only fit older adults were allowed to participate in clinical trials and those who were frail could not. There is an increasing number of older adult patients with cancer, and optimal treatment strategies for this vulnerable population should be considered.

In a pooled analysis from phase 3 trials (KEYNOTE-10, -024, -042), pembrolizumab monotherapy resulted in longer OS relative to chemotherapy with a more favorable safety profile among older adult patients. The results of a large international cohort study indicated that single-agent ICI may be effective and generally well-tolerated in patients 80 years and older. On the other hand, the efficacy and safety of ICI plus chemotherapy combination treatment (hereafter, ICI-chemotherapy) in older adult patients have not been fully explored. In a pooled analysis of anti–PD-1 and PD-L1 therapy in combination with chemotherapy vs immunotherapy alone, the OS benefit of adding chemotherapy was not demonstrated for patients 75 years and older. Even for data on pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy from clinical practice, the number of older adult patients is extremely limited. Therefore, we conducted a large retrospective study to determine the optimal choice of first-line drugs in older adults from clinical practice data and evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination ICI-chemotherapy treatment.

Methods

Patient Selection

We retrospectively reviewed the records of consecutive patients who met the following criteria: (1) cytologically or histologically confirmed NSCLC; (2) clinical stage IIIB or IIIC without indication of definitive thoracic radiotherapy, stage IV, or recurrent disease after surgery or radiotherapy; (3) patients who started first-line systemic therapy between December 2018 and March 2021; (4) patients 75 years and older at initiation of first-line systemic therapy. Patients with epidermal growth factor receptor gene variation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement, or whose first-line systemic therapy was a molecular-targeted drug, were excluded.

This multicenter observational study was conducted per the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. The study followed the reporting guideline for case series. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Tohoku University Hospital. Informed consent from individuals for the use of their medical data was obtained by the opt-out method based on a disclosure document.

Data Collection and Outcome Assessment

The following information was extracted from the patients’ medical records: age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, smoking history, histologic characteristics, clinical stage, metastatic sites, PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS), complete blood count results, biochemistry, chemotherapy regimen, tumor response, PFS, OS, toxic effect profiles, and course of second-line and third-line treatments. The data cutoff was December 31, 2021. Tumor response was evaluated by each physician according to the methods described in the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1). Objective response and disease control rates were defined as the proportion of patients achieving complete response or partial response and complete response, partial response, or stable disease, respectively. PFS was defined as the period from receiving the first dose of systemic therapy to disease progression, death from any cause, or the last day of follow-up. OS was defined as the period from receiving the first dose of systemic therapy to death from any cause or the last day of follow-up. Adverse events during the first-line course were assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 5.0. We extracted all-grade immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and grade 3 and higher non-irAEs. The decision regarding irAE or non-irAE distinction was made by each physician. Data analyses were performed between February 2022 and October 2022.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between 2 groups using Mann-Whitney U testing or the Fisher exact test. During the follow-up period, PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine hazard ratios (HRs) for OS and PFS.

For propensity score matching (PSM), the propensity scores for each patient were generated using logistic analysis given the covariates of age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, sex, smoking history, histologic characteristics, PD-L1 TPS, stage, and metastatic sites. For analysis of patients with PD-L1 TPS of 1% and higher, as well as the subset at 1% to 49%, PSM was applied at a 1:1 ratio to compare patients who received ICI alone with those who received ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment with caliper width 0.1 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. For analysis of patients with PD-L1 TPS 50% and higher, PSM was applied at a 2:1 ratio.

Multivariate analysis was performed including factors with P < .10 in univariate analysis. Differences in adverse event (AE) frequencies were examined using the Fisher exact test. Statistical significance was assessed as P < .05. The assumptions of the Cox model were assessed using the Schoenfield residuals-based test. GraphPad Prism, version 6.07 (GraphPad Software), and EZR, version 1.60, a graphical user interface for R statistical software (R Project for Statistical Computing), were used for statistical analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1245 patients (median [range] age, 78 [75-95] years; 967 [78%] male) with NSCLC were enrolled from 58 institutions in Japan. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All participants had Japanese ethnicity. PD-L1 expression of less than 1% occurred in 268 tumors (22%); 1% to 49% in 387 tumors (31%); 50% and higher in 410 tumors (33%); and unknown expression in 180 tumors (14%). Regimens selected for first-line therapy are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. A total of 354 patients (28%) received ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment; 425 patients (34%), ICI alone; 311 patients (25%), platinum-doublet chemotherapy; and 155 patients (12%), single-agent chemotherapy. The reasons for not selecting ICI-chemotherapy are shown in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. The PDL-1 status of each therapy group is shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Treatments.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) (N = 1245) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 78 (75-95) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 278 (22) |

| Male | 967 (78) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 367 (29) |

| 1 | 680 (55) |

| 2 | 171 (14) |

| 3 | 23 (2) |

| 4 | 1 (0.1) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.2) |

| Smoking history | |

| Never | 175 (14) |

| Current or former | 1069 (86) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) |

| Histologic characteristic | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 678 (54) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 456 (37) |

| NSCLC NOS | 77 (6) |

| Other | 34 (3) |

| Disease stage | |

| IIIB, IIIC | 143 (11) |

| IVA, IVB | 807 (65) |

| Recurrence | 295 (24) |

| PD-L1 tumor proportion score, % | |

| <1 | 268 (22) |

| 1-49 | 387 (31) |

| ≥50 | 410 (33) |

| Unknown | 180 (14) |

| Brain metastases | |

| Yes | 164 (13) |

| No | 1078 (87) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.2) |

| Bone metastases | |

| Yes | 325 (26) |

| No | 919 (74) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) |

| Liver metastases | |

| Yes | 131 (11) |

| No | 1113 (89) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) |

| Treatment | |

| ICI plus chemotherapy | 354 (28) |

| ICI alone | 425 (34) |

| Platinum-doublet chemotherapy | 311 (25) |

| Single-agent chemotherapy | 155 (12) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NSCLC NOS, non–small cell lung cancer not otherwise specified; PD-L1, programmed death ligand–1; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Efficacy

Median follow-up duration was 19.2 (95% CI, 17.8-20.5) months. There were 955 PFS events (76.7%) and 654 OS events (52.5%). Median OS was 20.0 (95% CI, 17.1-23.6) months for the ICI-chemotherapy group, 19.8 (95% CI, 16.5-23.8) months for ICI alone, 12.8 (95% CI, 10.7-15.6) months for platinum-doublet chemotherapy, and 9.5 (95% CI, 7.4-13.4) months for single-agent chemotherapy (Figure 1A). The median PFS was 7.7 (95% CI, 6.5-8.7) months, 7.7 (95% CI, 6.6-8.8) months, 5.4 (95% CI, 4.8-5.7) months, and 3.4 (95% CI, 2.6-4.0) months, respectively (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Overall Survival (OS) and Progression-Free Survival (PFS) of All Patients in the Cohort.

The Kaplan-Meier curves provide estimates of OS (A) and PFS (B) of the 1245 patients in the cohort, stratified by treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitor plus chemotherapy (ICI-chemotherapy), immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) alone, platinum-doublet chemotherapy, or single-agent chemotherapy.

The data on PFS, OS, objective response rate, and disease control rate for each regimen are shown in eFigure 1 and eTable 4 in Supplement 1. By stratifying according to histologic characteristics, the median OS was 20.4 months with ICI-chemotherapy vs 26.2 months with ICI alone (HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.78-1.37]) for adenocarcinoma, and median OS was 18.3 months vs 13.8 months (HR, 0.79 [95% CI, 0.57-1.09]) for squamous cell carcinoma (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). Regarding PD-L1 TPS, ICI-chemotherapy tended to yield a longer OS compared with ICI alone, but the difference was not significant (≥50% PD-L1 TPS: 28.0 months vs 21.5 months; HR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.62-1.34]; 1%-49% PD-L1 TPS: 20.0 months vs 14.3 months; HR, 0.79; [95% CI, 0.55-1.14]) (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

To compare the ICI-chemotherapy and ICI-alone groups with matched background factors, we performed PSM. Patient characteristics in patients with a PD-L1 TPS of 1% and higher before PSM are shown in eTable 5 in Supplement 1. Patient characteristics after PSM were uniform between the 2 groups (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). OS and PFS of patients with a PD-L1 TPS of 1% and higher after PSM was not significantly different between ICI-chemotherapy and ICI-alone groups (OS: 22.3 months vs 19.2 months; HR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.67-1.42]; PFS: 8.6 months vs 8.0 months; HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.67-1.25]) (Figure 2). By multivariate analysis, adding chemotherapy to ICI did not significantly prolong PFS and OS (OS: HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 0.73-1.56]; PFS: HR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.72-1.36]) (eTables 7 and 8 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Overall Survival (OS) and Progression-Free Survival (PFS) of Patients With Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Programmed Death Ligand–1 Expression of 1% and Higher After Propensity Score Matching .

The Kaplan-Meier curves provide estimates of OS (A) and PFS (B) of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor plus chemotherapy (ICI-chemotherapy) vs immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) alone. HR indicates hazard ratio; NR, not reported.

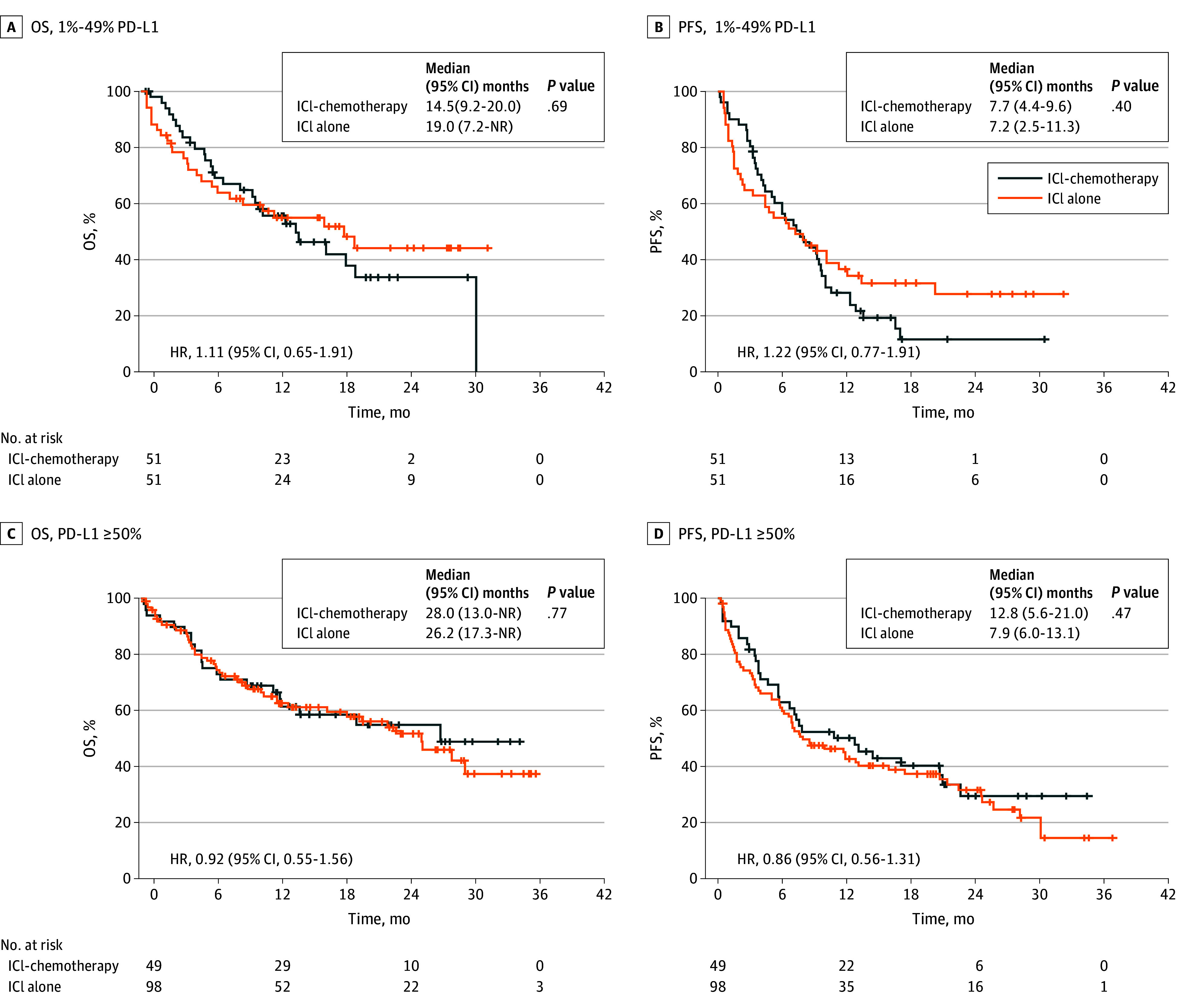

Subgroup analysis of patients with a PD-L1 TPS of 1% to 49% was also performed (eTable 9 in Supplement 1). There was no difference in OS and PFS between the ICI-chemotherapy and ICI-alone groups (OS: 14.5 months vs 19.0 months; HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.65-1.91]; PFS: 7.7 months vs 7.2 months; HR, 1.22 [95% CI, 0.77-1.91]), and the survival curves of the 2 groups crossed (Figure 3, A and B). Multivariate analysis showed that addition of chemotherapy to ICI failed to prolong OS or PFS (OS: HR, 1.31 [95% CI, 0.76-2.26]; PFS: HR; 1.26 [95% CI, 0.80-1.98]) (eTables 10 and 11 in Supplement 1).

Figure 3. Overall Survival (OS) and Progression-Free Survival (PFS) of Patients Stratified by Programmed Death Ligand–1 (PD-L1) Subgroups After Propensity Score Matching.

OS (A) and PFS (B) of patients with non–small cell lung cancer PD-L1 tumor proportion score of 1% to 49%. OS (C) and PFS (D) in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%. HR indicates hazard ratio; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; ICI-chemo, ICI plus chemotherapy combination treatment.

Subgroup analysis of patients with tumors having a PD-L1 TPS of 50% and higher was also performed (eTable 12 in Supplement 1), and there was no difference in OS and PFS between them (OS: 28.0 months vs 26.2 months; HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.55-1.56]; PFS: 12.8 months vs 7.9 months; HR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.56-1.31]) (Figure 3, C and D). By multivariate analysis, adding chemotherapy to ICI did not significantly prolong PFS and OS (PFS: HR, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.55-1.57]; OS: HR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.56-1.32]) (eTables 13 and 14 in Supplement 1).

Safety

Treatment was discontinued in 639 patients (51.3%) due to disease progression. The rate of discontinuation due to AEs was similar among all 4 groups (range, 19.0%-26.2%) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). Toxic effects are summarized in Table 2. All-grade irAEs and grade 3 and higher non-irAEs were extracted to compare ICI-chemotherapy with ICI alone, and with platinum-doublet chemotherapy. Grade 3 or higher irAEs occurred in 86 patients (24.3%) and 76 patients (17.9%) in the ICI-chemotherapy and ICI-alone groups, respectively (P = .03). The number of patients who required steroids for irAEs was 115 (32.5%) in the ICI-chemotherapy group and 105 (24.7%) in the ICI-alone group (P = .02). Pneumonitis was reported in 83 (23.4%) and 66 patients (15.6%) in the ICI-chemotherapy and ICI-alone groups, respectively (P = .006), with 41 (11.6%) and 29 (6.8%) having grade 3 and higher (P = .02). The safety profile for each regimen including more than 100 patients is shown in eTable 15 in Supplement 1.

Table 2. Adverse Events.

| irAEs | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICI-chemotherapy | ICI | |||

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| All | 173 (48.9) | 86 (24.3) | 171 (40.2) | 76 (17.9) |

| Steroid use due to irAEs | 115 (32.5) | NA | 105 (24.7) | NA |

| Pneumonitis | 83 (23.4) | 41 (11.6) | 66 (15.6) | 29 (6.8) |

| Colitis | 13 (3.7) | 7 (2) | 10 (2.4) | 1 (0.24) |

| Thyroid disorder | 18 (5.1) | 2 (0.6) | 16 (3.8) | 0 (0) |

| Skin disorder | 27 (7.6) | 11 (3.1) | 43 (10.1) | 13 (3.1) |

| Liver dysfunction | 15 (4.2) | 6 (1.7) | 14 (3.3) | 9 (2.1) |

| Kidney dysfunction | 19 (5.4) | 5 (1.4) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.24) |

| Endocrine disorder | 18 (5.1) | 13 (3.7) | 23 (5.4) | 13 (3.1) |

| Central nervous system disorder | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.24) |

| Other | 16 (4.5) | 10 (2.8) | 24 (5.6) | 11 (2.6) |

| Non-irAEs (grade ≥3) | ICI-chemotherapy | Platinum-doublet chemotherapy | Single-agent chemotherapy | |

| All | 189 (53.4) | 169 (54.3) | 68 (43.9) | |

| Leukopenia | 86 (24.3) | 86 (27.7) | 33 (21.3) | |

| Neutropenia | 126 (35.6) | 109 (35.0) | 31 (20) | |

| Febrile neutropenia | 18 (5.1) | 27 (8.7) | 17 (11) | |

| Anemia | 39 (11.0) | 22 (7.1) | 14 (9) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 27 (7.6) | 28 (9.0) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Liver dysfunction | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Fatigue | 9 (2.5) | 27 (8.7) | 6 (3.9) | |

| Vomiting | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Nausea | 4 (1.1) | 8 (2.6) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Anorexia | 24 (6.8) | 16 (5.1) | 11 (7.2) | |

| Diarrhea | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.6) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Constipation | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0) | |

Abbreviations: ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; ICI-chemotherapy, ICI plus chemotherapy combination treatment; irAE, immune-related adverse event; NA, not available.

In contrast, the incidence of grade 3 and higher myelosuppression was similar in the ICI-chemotherapy and platinum-doublet chemotherapy groups. The rate of dose reduction was similar in the ICI-chemotherapy and platinum-doublet chemotherapy groups, reflecting similar degrees of myelosuppression in both (eTable 16 in Supplement 1). Treatment-related deaths occurred in 9 patients (2.5%), 8 patients (1.9%), 6 patients (1.9%), and 1 patient (0.65%) treated with ICI-chemotherapy, ICI alone, platinum-doublet chemotherapy, and single-agent chemotherapy, respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study to investigate the efficacy and safety of ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment in older adult patients with advanced NSCLC. In this study using PSM, no significant differences in OS were discerned between treatment with an ICI-chemotherapy combination and ICI alone, but the incidence of grade 3 and higher irAEs and steroid use due to irAEs was more frequent in patients treated with ICI-chemotherapy than with ICI alone.

To investigate the choice of first-line drugs for older adult patients in clinical practice, we consecutively incorporated older adults who received any first-line systemic treatments other than molecular-targeted therapy. The numbers of patients receiving ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment, ICI alone, or platinum-doublet chemotherapy were similar. Pembrolizumab monotherapy was the most frequent regimen used, which may have been due to patient age and the study era. The combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab might now be increasingly selected based on the Checkmate 227 and Checkmate 9LA trials, requiring the investigation of the efficacy of this regimen in older adults in the future.

In the present study, OS in the ICI-chemotherapy group was 20.0 months and PFS was 7.7 months. Almost all had received pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. The median OS and PFS under this regimen were reported as 22.0 and 9.0 months in KEYNOTE-189, respectively, and 17.1 and 8.0 months in KEYNOTE-407, respectively. Thus, the efficacy for older adult patients in the present study was similar to that reported in these clinical trials.

Here, OS and PFS in patients receiving ICI alone were 19.8 and 7.7 months, respectively. A total of 397 patients (93%) in the ICI-alone group received pembrolizumab monotherapy. In KEYNOTE-024, median OS and PFS values were 26.3 months and 7.7 months, respectively, with 5 years of follow-up. In KEYNOTE-042, OS and PFS values were 16.4 and 5.6 months, respectively, in the subgroup with PD-L1 TPS of 1% and higher. Hence, the OS data of the present study were again similar to those from clinical trials, considering that 69.9% and 26.1% of patients had PD-L1 TPS 50% and higher and 1% to 49%, respectively. There were only 12 patients who had PD-L1-negative tumors and received ICI alone in the present study. The difference in OS based on histologic characteristics (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1) seemed to be due to the different distribution of PD-L1 TPS between squamous and adenocarcinomas. Patients with PD-L1 TPS of 50% and higher constituted 75% and 61% of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, respectively.

PD-L1 TPS, PS, stage, and bone metastases were factors with large differences between ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment and ICI alone before PSM. A high PD-L1 TPS, a larger number of postoperative recurrence with presumably low tumor volume, and a smaller number of patients with bone metastases were favorable for ICI alone. Older age and poor PS were unfavorable for treatment with ICI alone. To eliminate selection bias as much as possible, we performed PSM to compare OS and PFS between ICI-chemotherapy and ICI alone but found no differences regardless of PD-L1 TPS of 1% and higher, 1% to 49%, or 50% and higher.

To our knowledge, no prospective studies comparing ICI-chemotherapy with ICI alone have been reported thus far. A pooled US Food and Drug Administration analysis of anti–PD-1 and PD-L1 therapy combined with chemotherapy vs immunotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC with PD-L1 score of 1% to 49% or 50% and higher showed no OS benefit of adding chemotherapy for patients aged 75 years, although the number of patients was low, at 132 and 185, respectively. A phase 3 randomized clinical trial comparing pembrolizumab alone followed by chemotherapy and pembrolizumab together with chemotherapy in advanced nonsquamous NSCLC is currently ongoing. Although that study is not focused on the older adult population, it may provide a more definitive answer to the question of the necessity for chemotherapy in the future.

We also found that the median OS and PFS of patients with platinum-doublet chemotherapy was shorter than for ICI with or without chemotherapy, and platinum-doublet chemotherapy was similar to ICI alone even when the PD-L1 TPS was 1% to 49%. Although we need to take subsequent treatment after platinum-doublet chemotherapy into account, these data suggest that ICI should be preferred over platinum-doublet chemotherapy in the patient population with PD-L1 TPS of 1% and higher.

Here, we have also reported important findings regarding safety profiles in older adult patients. The rates of grade 3 and higher irAEs and use of steroids were significantly higher for patients on ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment than ICI alone. Despite this, however, the discontinuation rate due to AE was similar in the ICI-chemotherapy and ICI-alone groups (26% vs 24%). This may have been influenced by the younger age and better PS of patients in the ICI-chemotherapy group. The use of steroids may lead to life-threatening complications such as infection and thrombosis, and affect the survival of older adult patients.

The irAEs occurring at a significantly high frequency with ICI-chemotherapy vs ICI-alone groups were pneumonitis (23.4% vs 15.6%) and kidney dysfunction (5.4% vs 0.94%). Especially, the incidence of grade 3 and higher pneumonitis was 11.6% in the ICI-chemotherapy group. Although higher rates were observed in clinical practice compared with those reported from the clinical trials, several retrospective studies have also reported a high incidence of pneumonitis in patients on ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment. Observational data from clinical practice for pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for older adult patients in China indicated that grade 3 and higher pneumonitis occurred in 9%, and AEs leading to discontinuation registered 26%. Another study conducted in Italy reported grade 3 and higher pneumonitis occurring in 10.2% of patients receiving a combination of pembrolizumab, platinum, and pemetrexed with a median age of 68 years. Furthermore, Morimoto et al reported that the incidence of grade 3 and higher pneumonitis reached 16.0% in patients 75 years and older who received pembrolizumab with platinum and pemetrexed in Japan. Considering these results, ICI-chemotherapy resulted in an increased frequency of severe pneumonitis relative to ICI alone, especially in older adults.

Limitations

First, due to this study’s retrospective nature, the timing of tumor assessment was not uniform among the different study sites, and radiographic outcomes were verified by investigators without central review. This can lead to either an overestimation or underestimation of PFS. However, we have thoroughly documented OS data, which is the most robust clinical end point and the most important indicator of therapeutic efficacy. Second, the diagnosis of AEs was based on medical records. Furthermore, the decision as to whether AEs were irAEs or non-irAEs was made by the attending physician without central review. This distinction is difficult and it has been reported that some are overlooked in clinical trials. Therefore, caution should be exercised in interpreting the incidence of adverse events, including irAEs. Third, the cohort from the present study has a single ethnicity because this study was conducted in Japan. Comparing global data and Japanese subset data of trials of pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE-189, -407, and -024), the incidence of irAEs including pneumonitis was higher in the Japanese population. Therefore, caution should be exercised when considering global applicability regarding the incidence of irAEs. Finally, the differences in baseline characteristics of the patients may affect the results of retrospective studies. Because the cohort from the present study was large, we attempted to compensate for this using PSM. However, factors, such as comorbidities, of which we were unaware may have affected the results. Therefore, accurate comparison of each group to answer which regimen should be selected remains a challenge.

Conclusions

In this study, ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment did not improve survival compared with ICI alone but increased the incidence of grade 3 and higher irAEs for patients 75 years and older in clinical practice. Based on these results, ICI alone may be recommended for older adult patients with PD-L1–positive (TPS of ≥1%) NSCLC. Randomized clinical trials comparing ICI alone vs ICI-chemotherapy combination treatment are needed to validate these findings in this population.

eTable 1. Details of the treatment regimens

eTable 2. Reasons for not selecting ICI-chemotherapy

eTable 3. PD-L1 expression by treatment group

eTable 4. Response to treatment

eTable 5. Patient Characteristics (before propensity score matching)

eTable 6. Patient Characteristics (after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1%)

eTable 7. Cox hazards analysis for overall survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1%

eTable 8. Cox hazards analysis for progression-free survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1%

eTable 9. Patient Characteristics (after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS 1-49%)

eTable 10. Cox hazards analysis for overall survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS 1-49%

eTable 11. Cox hazards analysis for progression-free survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS 1-49%

eTable 12. Patient Characteristics (after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%)

eTable 13. Cox hazards analysis of overall survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%

eTable 14. Cox hazards analysis of progression-free survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%

eTable 15. Adverse events, by treatment

eTable 16. Treatment exposures

eFigure 1. Overall survival and progression-free survival according to treatment regimens

eFigure 2. Overall survival and progression-free survival according to histology

eFigure 3. Overall survival and progression-free survival according to programmed death–ligand 1 tumor proportion score

eFigure 4. The reasons for treatment discontinuation

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. ; KEYNOTE-024 Investigators . Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823-1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1–positive, advanced non–small cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540-1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, et al. Five-year outcomes from the randomized, phase III trials CheckMate 017 and 057: nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non–small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):723-733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. ; OAK Study Group . Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non–small cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255-265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. ; KEYNOTE-189 Investigators . Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078-2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. ; KEYNOTE-407 Investigators . Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040-2051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. ; IMpower150 Study Group . Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288-2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non–small cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):924-937. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020-2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu TE, Cobo M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(2):198-211. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30641-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naltet C, Besse B. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in elderly patients treated for a lung cancer: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(6):3014-3028. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenke Y, Hakozaki T, Nakahara Y, Horinouchi H, Ohe Y; Lung Cancer Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) . Medical management of older patients with lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2022;52(10):1082-1088. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyac135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pallis AG, Gridelli C, Wedding U, et al. Management of elderly patients with NSCLC; updated expert’s opinion paper: EORTC Elderly Task Force, Lung Cancer Group and International Society for Geriatric Oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1270-1283. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosaki K, Saka H, Hosomi Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients with PD-L1–positive advanced non–small cell lung cancer: Pooled analysis from the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 studies. Lung Cancer. 2019;135:188-195. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nebhan CA, Cortellini A, Ma W, et al. Clinical outcomes and toxic effects of single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors among patients aged 80 years or older with cancer: a multicenter international cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(12):1856-1861. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akinboro O, Vallejo JJ, Mishra-Kalyani PS, et al. Outcomes of anti–PD-(L1) therapy in combination with chemotherapy versus immunotherapy (IO) alone for first-line (1L) treatment of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with PD-L1 score 1-49%: FDA pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15)(suppl):9001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.9001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimoto D, Miura S, Yoshimura K, et al. A real-world study on the effectiveness and safety of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for nonsquamous NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;3(2):100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velcheti V, Hu X, Piperdi B, Burke T. Real-world outcomes of first-line pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed-carboplatin for metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC at US oncology practices. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9222. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88453-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy monotherapy as a first-line treatment in elderly patients (≥75 years old) with non–small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:807575. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.807575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikezawa Y, Mizugaki H, Morita R, et al. Current status of first-line treatment with pembrolizumab for non–small cell lung cancer with high PD-L1 expression. Cancer Sci. 2022;113(6):2109-2117. doi: 10.1111/cas.15361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kempen JH. Appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(1):7-10.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brahmer JR, Lee JS, Ciuleanu TE, et al. Five-year survival outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer in checkmate 227. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(6):1200-1212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodríguez-Abreu D, Powell SF, Hochmair MJ, et al. Pemetrexed plus platinum with or without pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: protocol-specified final analysis from KEYNOTE-189. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(7):881-895. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paz-Ares L, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC: protocol-specified final analysis of KEYNOTE-407. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(10):1657-1669. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥50. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(21):2339-2349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Castro G Jr, Kudaba I, Wu YL, et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and programmed death ligand–1 tumor proportion score ≥1% in the KEYNOTE-042 study. J Clin Oncol. 2022:JCO2102885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akinboro O, Vallejo JJ, Nakajima EC, et al. Outcomes of anti–PD-(L)1 therapy with or without chemotherapy (chemo) for first-line (1L) treatment of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with PD-L1 score ≥50%: FDA pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16)(suppl):9000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.9000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Testing the timing of pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy as first line treatment and maintenance in non–small cell lung cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2024. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03793179

- 31.Attili I, Valenza C, Santoro C, et al. Comparison of real-world data (RWD) analysis on efficacy and post-progression outcomes with pembrolizumab plus chemo vs chemo alone in metastatic non-squamous non–small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 <50. Front Oncol. 2022;12:980765. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.980765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morimoto K, Yamada T, Yokoi T, et al. Clinical impact of pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2021;161:26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naqash AR, Moey MYY, Cherie Tan XW, et al. Major adverse cardiac events with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pooled analysis of trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(29):3439-3452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horinouchi H, Nogami N, Saka H, et al. Pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed-platinum for metastatic nonsquamous non–small cell lung cancer: KEYNOTE-189 Japan Study. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(8):3255-3265. doi: 10.1111/cas.14980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugawara S, Tanaka K, Imamura F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in Japanese patients with metastatic squamous non–small cell lung cancer in KEYNOTE-407. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(8):3330-3341. doi: 10.1111/cas.15816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satouchi M, Nosaki K, Takahashi T, et al. First-line pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy in metastatic non–small cell lung cancer: KEYNOTE-024 Japan subset. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(12):5000-5010. doi: 10.1111/cas.15144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Details of the treatment regimens

eTable 2. Reasons for not selecting ICI-chemotherapy

eTable 3. PD-L1 expression by treatment group

eTable 4. Response to treatment

eTable 5. Patient Characteristics (before propensity score matching)

eTable 6. Patient Characteristics (after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1%)

eTable 7. Cox hazards analysis for overall survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1%

eTable 8. Cox hazards analysis for progression-free survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1%

eTable 9. Patient Characteristics (after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS 1-49%)

eTable 10. Cox hazards analysis for overall survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS 1-49%

eTable 11. Cox hazards analysis for progression-free survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS 1-49%

eTable 12. Patient Characteristics (after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%)

eTable 13. Cox hazards analysis of overall survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%

eTable 14. Cox hazards analysis of progression-free survival after propensity score matching of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%

eTable 15. Adverse events, by treatment

eTable 16. Treatment exposures

eFigure 1. Overall survival and progression-free survival according to treatment regimens

eFigure 2. Overall survival and progression-free survival according to histology

eFigure 3. Overall survival and progression-free survival according to programmed death–ligand 1 tumor proportion score

eFigure 4. The reasons for treatment discontinuation

Data Sharing Statement