Abstract

Opioid overdose is the leading cause of drug overdose lethality, posing an urgent need for investigation. The key brain region for inspiratory rhythm regulation and opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) is the preBötzinger Complex (preBötC) and current knowledge has mainly been obtained from animal systems. This study aimed to establish a protocol to generate human preBötC neurons from induced pluripotent cells (iPSCs) and develop an opioid overdose and recovery model utilizing these iPSC-preBötC neurons. A de novo protocol to differentiate preBötC-like neurons from human iPSCs has been established. These neurons express essential preBötC markers analyzed by immunocytochemistry and demonstrate expected electrophysiological responses to preBötC modulators analyzed by patch clamp electrophysiology. The correlation of the specific biomarkers and function analysis strongly suggests a preBötC-like phenotype. Moreover, the dose-dependent inhibition of these neurons’ activity was demonstrated for four different opioids with identified IC50’s comparable to the literature. Inhibition was rescued by naloxone in a concentration dependent manner. This iPSC-preBötC mimic is crucial for investigating OIRD and combating the overdose crisis and a first step for the integration of a functional overdose model into microphysiological systems.

Keywords: iPSC-derived, preBötC, opioid overdose, overdose rescue, human in vitro model

Graphical Abstract

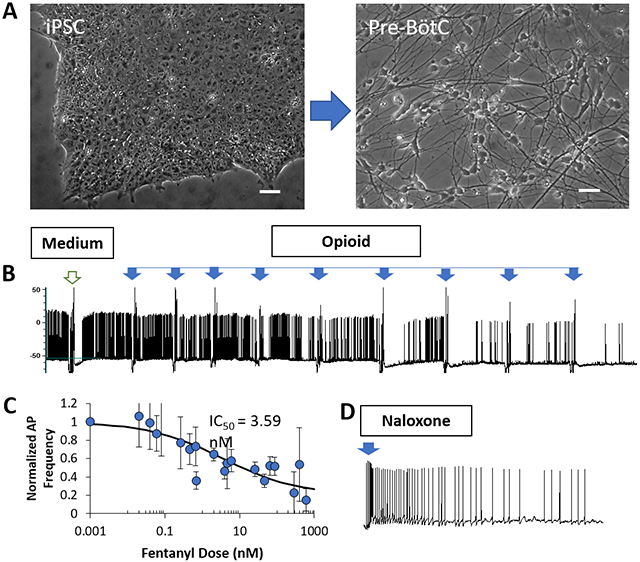

Development of an opioid overdose neuronal model. A) A protocol is developed to differentiate Pre-BötC-like neurons from human iPSCs. Neuronal response to opioids and rescue by Naloxone is investigated by electrophysiology. B) The spontaneous neural activity is inhibited by opioids and C) dose-dependent curves are generated for fentanyl and other opioids. D) The opioid-induced inhibition can be rescued by Naloxone.

1. Introduction

Opioids abuse and disorders due to its misuse are a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare, and has become a global public health emergency.[1] Use or misuse of illicit and prescription opioids, especially synthetic opioids like fentanyl, are currently the main drivers of drug overdose deaths. Nearly 70% of the 67,367 deaths in 2018 involved an opioid based on a CDC report.[2] Opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD), caused by prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, is described as a slowing and shallowing of respiration and is the major cause of death associated with opioid analgesics and drugs of abuse[3] due to ensuing bradypnea, apnea, and resulting hypoxemia. The mammalian respiratory motor network appears to assemble from three rhythmogenic medullary microcircuits;[4-6] the preBötzinger Complex (preBötC), responsible for inspiratory rhythm generation,[7] the Retrotrapezoid/Parafacial nucleus (RTN/pFRG),[8] critical for active expiration, and the Post-inspiratory Complex (PiCo), associated with post-inspiratory activity.[4] The core and most essential portion of the respiratory network is the preBötC, a bilateral and symmetrical neural network located in the brainstem, which individually is sufficient to generate inspiration rhythm, and follower neurons shape motor outputs by activating upper airway respiratory muscles.[6] The preBötC is composed of excitatory rhythmogenic interneurons and excitatory and inhibitory pattern-forming interneurons that together produce the essential periodic drive for inspiration.[9] Coupled oscillatory microcircuits make up the rhythmic core of the breathing network[10] but only preBötC and PiCo are suppressed by opioids.[6, 10] Although opioid receptors are widely distributed in the brainstem, including at sites likely to contribute to respiratory depression such as the Kölliker-Fuse/Parabrachial nuclei,[11, 12] only the preBötC is essential for breathing and survival.[13-16]

The importance of the preBötC in neural control of breathing and its potential participation in neurological diseases in humans has been suggested based on pharmacological manipulation and lesion of the preBötC in animal models, both in vivo and in vitro.[17] The preBötC contains interneurons expressing neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1R) and the peptide somatostatin (SST). NK1R activation increases rhythmic breathing and genioglossus muscle activity in wild-type mice. Conversely, SST decreases the rhythmic breathing via SST2 receptors and reduces genioglossus muscle activity, likely through SST4 receptors. At its core, a population of neurons expressing neurokinin-1 NK1R and the peptide somatostatin (SST) form the site essential for the generation of breathing rhythm.[13, 15] Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, with opioids being the most common drug. In 2015, over 33,000 deaths were attributed to opioid overdoses,[18] which increased to 64,000 in 2017.[19] The CDC currently estimates that more than 1000 emergency department visits daily are related to the misuse of opioids which lead to about 91 opioid overdose deaths every day.[18] The main opioid receptors that mediate their effect are mu (μ), kappa (κ), and delta (δ). Most of the potent opioid analgesics currently in use act through the mu opioid receptor (MOR), and MORs are recognized as the key receptors mediating opioid overdose-induced OIRD.[20] Administration of morphine and other opioids failed to induce OIRD in MOR knockout mice.[21, 22] MORs mediate the pleasurable properties of therapeutic and/or abused opiates in vivo, and are important for the reward mechanisms of other drugs of abuse,[23] therefore it is perhaps unsurprising that drugs activating μ (e.g. heroin, morphine and oxycodone (Oxycontin®)) are also the most commonly abused. Conversely, kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) agonists produce dysphoric states and stress and drug abuse both enhance KORdynorphin (Dyn) signaling.[24] By contrast, delta-opioid receptor (DOR) activity reduces anxiety and depressive states, and regulates learning and memory.[25]

Since 1996, naloxone has been the treatment of choice to reverse the potentially fatal respiratory depression caused by overdose of heroin, fentanyl and other opioids,[26] and remains a mainstay therapy for opioid overdose in both community-based programs and clinical practice.[27] Naloxone is a mu-opioid antagonist clinically indicated for treatment of opioid overdose and has no agonistic activity.[28] It antagonizes opioid effects by displacing opioid agonists from opioid receptors in the central nervous system, reversing opioid-related respiratory depression. Typically larger doses are used to treat emergent, life-threatening respiratory depression in pre-hospital and inpatient settings, with recent public health policy emphasizing the role of community access to naloxone and reversal of opioids by non-clinical bystanders.[29-31] In monitored clinical settings such as intensive care units, operating rooms and post-anesthesia care units, clinicians may administer lower, titrated doses of naloxone to prevent or modulate OIRD without completely reversing its analgesic actions.[20, 32-34] Naloxone infusions have also been used to treat opioid-related side effects,[35, 36] to protect the spinal cord from presumed ischemic injury during surgery on the aorta,[37, 38] to modulate glial/microglial-mediated CNS inflammation,[39-42] and to modulate behavioral reward pathways,[43-45] amongst other applications.[46-48] The drug is thought to be relatively safe in acute doses, although abrupt reversal of opioid overdose may pose significant hemodynamic consequences in at-risk populations. Naloxone can be administered via several routes including intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, or via endotracheal tube. The dose may be repeated to reverse long-acting or short-acting opioids, although requirements for redosing naloxone remain predicated upon the pharmacokinetics of the opioids in need of reversal. The major known adverse effect of naloxone in opioid-dependent patients is precipitated opioid withdrawal.[49]

Numerous studies concerning the physiology and regulation of preBötC function as well as its role in opiate-induced respiratory depression have been reported in the literature, but primarily from animal models. The typical models for preBötC study are either in vivo or in vitro rodent models. For in vivo models, the specific population of neurons were investigated under the perfusion of the opioid drugs in genetically/functionally knocked out of neurons in the complex while the respiration activity was monitored.[14, 21, 22, 50, 51] For in vitro models, organotypic brainstem slices containing the preBötC region combined with electrophysiology and pharmacology is the primary method of investigation.[52-54] However, species comparison studies have indicated the differences between human and rodent systems in MOR gene expression regulation [55], opioid drug bias [56], and ligand-directed signaling pathways [57], highlighting the importance of developing human-based overdose models. Unfortunately, the literature concerning preBötC physiology in humans is fairly minimal except that inferred from post-mortem anatomical analysis[58] or injury/disease associated lesions affecting the relevant regions.[59] There are no human in vitro models of the preBötC complex as it has not been investigated using primary cultures nor have neurons of the complex been differentiated from stem cells such as iPSCs. To better translate the findings from animal studies to the clinic, and to facilitate the development of effective and safe strategies and therapies to opiate overdose, this study aimed to generate preBötC neurons from human iPSC and establish a human-based platform to investigate opiate overdose and recovery using naloxone for integration into a microphysiological system.

2. Results

2.1. Development of the Differentiation Protocol for PreBötC Neurons from hiPSCs

In vitro differentiation of preBötC neurons is a challenge because of the small size of this neural complex, scant literature concerning its in vitro differentiation and lack of conclusive molecular markers to distinctively identify the cells in the complex as primary cultures from humans has not been demonstrated to date. The general design of the differentiation procedure is depicted in Figure 1A. The protocol was developed by adapting information from a study by Lippmann et al. that reported on the in vitro deterministic HOX patterning in hiPSC-derived neuroectoderm and a defined approach to derive regional neural phenotypes from diverse hindbrain and spinal cord domains.[60] The preBötC neuronal differentiation protocol was designed to first induce brain stem region neurons based on HOX gene patterning development as described in,[60] followed by neural fate induction targeting the preBötC region.[61] The phase images of the culture at different stages of differentiation are shown in Figure 1B. During D3~D11, the cultures went through active differentiation processes evidenced by the significant mobilization of cells and their morphological changes. Starting from D7, neural rosette structures began to appear and became increasingly prominent. After 19 days of differentiation, the cultures were then replated into a low density culture to encourage neuronal maturation. The passage 1 culture was passaged one additional time to further accelerate the neuronal maturation and after another 20 days, the neurons were competent for functional analysis.

Figure 1. Design of differentiation protocol of preBötC-like neurons from hiPSCs.

A) Differentiation protocol scheme. B) Phase images of the culture at different stages of differentiation. Scale bar: 40 μm.

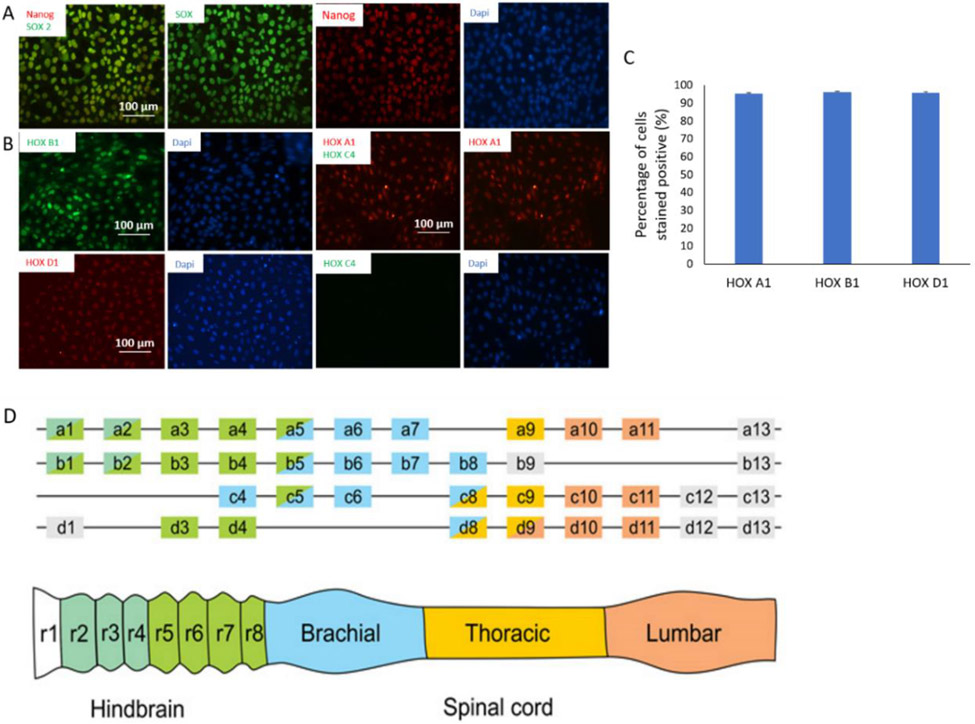

As shown in Figure 1A, the induction of brainstem identity through HOX gene activation was initiated by successive activation of fibroblast growth factor and wnt/β-catenin. Retinoic Acid was added at 24 hours after the colinear HOX activation, and the identity of the brainstem neuroectoderm was then characterized for the expression of HOX genes by immunocytochemistry (Figure 2A) and quantified as in Figure 2B. In mammals, 39 Hox genes with some structural homology are organized in 13 paralogous groups, forming 4 clusters on 4 separate chromosomes. The genes within each cluster are arranged along the chromosomes in a 3' to 5' gradient representing expression in embryos in an equivalent anterior-posterior direction needed for determining, positioning, and patterning of embryonal organs along the body axis.[62, 63] The HOX combination correspondent to the brainstem is the expression of HOXA1, B1, D1 and the absent expression of HOXC4.[63] As in Figure 2, the neuroectoderm cells expressed the right HOX gene combinations as targeted. Therefore, cells during differentiation expressed the HOX gene combination that confirmed the correct intermediate neuronal identity of these cells along the differentiation path outlined to produce preBötC neurons.

Figure 2. Characterization of the differentiation path of preBötC neurons from hiPSCs by immunocytochemistry.

A) HiPSCs stained positive to the pluripotent markers Nanog and SOX2. Scale bar: 100 μm. B) Cells at an early stage of differentiation expressed the set of rohmbomeric genes correspondent to the derivative region for the preBötC complex during development: positive to HoxA1, HoxB1 and HoxD1 but negative to HoxC1. Scale bar: 100 μm. C) Quantification of the percentage of cells positive to HOXA1, HOXB1, and HOXD1. Data presented as: Mean + STDEV. N=3 Experiments. For each experiment, 3 sets of images were quantified. D) In vertebrates 39 Hox genes are distributed across 4 clusters. Each Hox gene is expressed in discrete rostrocaudal domains within the hindbrain and spinal cord. Color coding of Hox genes represents expression domains along the rostrocaudal axis. (Figure cited from [63])

2.2. Immunocytochemistry Characterization of iPSC-Derived PreBötC-like Neurons

The preBötC circuit consists of the “core” of rhythmogenerator, glutamatergic neurons, and inhibitory regulatory neurons, including GABAergic and Glycinergic neurons.[64, 65] The glutamatergic neurons heterogeneously co-express several markers including NK1R, SST, and the μ-opiate receptor (MOR), each marking a different population but are more or less overlapping in composition.[9] The initial set of markers analyzed were NK1R and MOR, the primary markers reported for preBötC neurons and essential for their regulation by opioids. NK1R is a peptide receptor expressed in a subpopulation of rhythmogenic neurons in the preBötC. Binding of Substance P can activate this receptor and increase the inspiration rhythm. Normal breathing requires preBötzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons.[15] A subset of NK1R-expressing preBötC neurons also express MOR and binding of opiate can inhibit neural activity and induce the depression of inspiration. It is postulated that Type 1 neurons in the preBötC, which have rhythmogenic properties, express both NK1Rs and MORs, whereas type 2 neurons express only NK1Rs.[66] As in Figure 3A, the generated preBötC neurons expressed Dbx1, the transcription factor that gives rise to respiratory rhythm-generating neurons in the preBötzinger complex.[67, 68] These neurons were also positive to NK1Rs and MORs, the markers for the subpopulation of neurons that account for the opiate sensitivity of the preBötC complex.[69] The expression of other opioid receptors was also analyzed (Figure S1). KOR expression was observed in these neurons primarily in the processes while no DOR expression was observed.

Figure 3. Differentiation of preBötC-like neurons from hiPSCs characterized by immunocytochemistry and electrophysiology.

A-B) Differentiated neurons plated at low density were stained positive for the preBötC markers Dbx1, co-stained with MAP2 (A) and NK1R and MOR (B). Scale bar: 100 μm. C-F) D13 culture stained with the markers GFAP (C), vGluT and SST (D), GluR2/3 and MAP2 (E), vGluT and GABA (F). Scale bar: 100 μm. G) Quantification of the GABAergic and Glutamatergic neurons in the preBötC neuron population based on immunocytochemistry analysis. Data were presented as: Mean + SEM. N=3 batches of differentiation. For each batch, 15 images were quantified.

The preBötC culture was analyzed for the composition of neuron versus glia populations (Figure 3B) and the ratio of neurons (MAP2+) to astrocytes (GFAP+) was approximately 3:1 in the culture. A subset of preBötC neurons expressed the SST peptide and SST+-neuron-mediated inhibitory pathways have been shown to modulate respiratory activity.[67] Elimination of glutamate release from SST-positive preBötC neurons by genetic ablation of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2) indicated that this population of neurons plays a role in regulating respiration-related vocal behavior.[70] Silencing of preBötC SST-expressing neurons through the activation of a transgenically expressed allatostatin receptor induced persistent apnea in awake rats.[13] ICC of the iPSC-preBötC culture revealed a subpopulation of neurons were SST-positive (Figure 3C).

The potential of these neurons to respond to glutamate was analyzed by immunostaining for the glutamate receptor (GluR), indicating almost all the neurons (labeled by MAP2) expressed GluR (Figure 3D). The culture was also characterized for the composition of excitatory versus inhibitory neurons utilizing the markers vGlut and GABA, respectively (Figure 3E). From studies in rodents, although the inspiration relies on glutamatergic neurons, a significant subset of preBötC neurons are inhibitory and express either GABA or Glycine, or both.[6, 71] The role of these inhibitory neurons is still elusive although different hypothesis have been proposed including coordinating inspiration and expiration activity through connections with different respiration circuits, both ipsilateral and contralateral, or by shaping respiratory motor outputs.[6, 71] As in Figure 3F, the neurons in the culture were mainly glutamatergic (66.5%+/−9.8) containing a small population of inhibitory neurons (14.4%+/−2.3%), while another population of neurons expressed both Glutamate and GABA (19.1%+/8.1), with qualification listed in Figure 3G.

2.3. Functional Characterization of iPSC-PreBötC-like Neurons

Electrical function of the hiPSC-preBötC derived neurons was analyzed by patch clamp electrophysiology (Figure 4). These neurons demonstrated active spontaneous action potentials (APs), occasionally in bursts but mostly with sporadic electrical activity (Figure 4E-F), both of which have been reported for preBötC neurons.[72, 73] Quantification of 84 recorded neurons indicated 38 demonstrated rhythmic bursting (45.23%). Glutamate-mediated signaling has been proposed as an essential mechanism in rhythmogenesis in preBötCs,[74] therefore the capability of these iPSC- preBötC neurons to respond to glutamate was tested via patch clamp recordings. Glutamate dosing induced intensive neuronal firing as displayed in Figure 5A. The preBötC coordinates all phases of the breathing cycle, coordinates breathing with orofacial behaviors and strongly influences, and is influenced by, emotion and cognition.[9] Therefore, neurons in the preBötC complex receive modulations from a variety of inputs so that the breathing rhythm can be regulated in response to a multitude of internal or external cues. The effects of several confirmed molecular modulators, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP), Substance P and somatostatin (SST), were tested on the preBötC neurons by patch clamp electrophysiology.

Figure 4. Patch clamp recordings from the iPSC-preBötC-like neurons.

A) A snapshot of a neuron under patch clamp analysis. B) Sample trace of an action potential (AP). C) Representative inward and outward currents induced by stepwise depolarization under voltage clamp mode. D) A sample trace of repetitive firing induced by current injection. E-F) Spontaneous activity recorded under gapfree conditions demonstrated either rhythmic (E) or sporadic (F) electrophysiological patterns.

Figure 5. Patch clamp analysis of iPSC-preBötC-like neurons.

A) Dosing of Glutamate (10 uM) elicited a neuronal response. B) Under gapfree conditions, dosing of ATP (100 μM) induced depolarization and bursting of action potentials. C) Treatment with Substance P (Sub P, 5 μM) increased iPSC-Pre-BotC neuronal activity. D) Treatment with Somatostatin (SST, 1 μM) inhibited iPSC-Pre-BotC neuronal activity. (n>=3 cells for each compound testing).

ATP is released during hypoxia from the ventrolateral medulla (VLM) and activates purinergic P2 receptors (P2Rs) in the preBötC network by increasing inspiratory frequency.[75] Substance P modulates preBötC and RTN network activity by binding to the receptor NK1R which is coupled with voltage-independent cation channels to increase neuronal excitability.[76-79] The respiratory activity can be increased by neuromodulators, such as substance P and serotonin.[78] Sources of Substance P have been found in some chemosensitive serotonergic neurons within the ventral lateral medulla that innervates the RTN and preBötC regions. SST is released by a subset of glutamatergic preBötC neurons, but acts as an inhibitory neuromodulator. The function of SST modulation in the preBötC is proposed to stabilize breathing rhythmicity in both normoxic and hypoxic conditions.[80] As shown in Figure 5B-D, the activity of the iPSC-derived preBötC neurons was increased by ATP and Sub P, and decreased by SST, which is similar to the reported in vivo responses of preBötC neurons to these modulators.[73, 81] The functional characterization further confirmed that the protocol developed with iPSC-derived neurons resulted in a preBötC neuronal lineage.

2.4. Development of an Opiate Overdose Model Utilizing Human iPSC-Drived PreBötC-like Neurons

The field of addiction and pain research would benefit from a human neuronal model of respiration and overdose recovery so these iPSC-derived preBötC neurons were tested for functional susceptibility to four opioids: Fentanyl, methadone, codeine and DAMGO (D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin). Codeine, a natural opium alkaloid, is a prodrug, which exerts its full activity upon bioactivation to morphine and morphine glucuronide. Fentanyl and methadone represent synthetic opioids in the families of anililoperidines and dipehenylpropylamines respectively. Clinically, Codeine is usually used to treat mild to moderately severe pain. Fentanyl has demonstrated high potency and is typically used to treat severe pain such as those with cancer or after surgery, and has a high tendency to translate to an opioid use disorder (OUD). Methadone is prescribed for pain reduction or for the treatment of OUD given its extend half-life. DAMGO is a synthetic opiate peptide with high MOR specificity. The electrophysiological response of the preBötC neurons to each opiate was analyzed by patch clamp electrophysiology. For each patched neuron, after a period of recording of spontaneous activity, puffs of each opioid at different doses were added sequentially and their addition induced hyperpolarization. As the dosage increased in a stepwise manner, the activity of these neurons was gradually inhibited as demonstrated by a decrease of AP frequency. As in Figure 6A for representative electrophysiological recordings, all four opioids significantly reduced neuronal AP firing when applied at incremental dosages. Dose-response analysis indicated a dose-dependency of the inhibition effect for all four opioids. While all had the same Imax value under normalized scale, each demonstrated different IC50 values and had different effective dose windows. The slope of the dose-response curve of each drug was also different for each opioid. Methadone had the steepest slope while Fentanyl had the flattest, indicative of a different susceptibility to adverse effects upon dose changes (Figure 6B). To ensure that the change of AP frequency was not caused by the action of repetitive dosing, a control experiment was performed by repeat dosing the system with medium alone, where no change in the AP was observed (Figure S2).

Figure 6. Electrophysiological responses of iPSC-pre-BötC-like neurons to opioids (DAMGO, Methadone, Fentanyl and Codeine) characterized by patch clamp.

A) Sample trace of the response of iPSC-preBötC neurons to each opioid, indicating the firing frequency decreased as the opioid dosages were increased. A dosing with medium was added before each opioid as a control for the dosing action. B) Dose-response curve of the preBötC neurons’ response to each opioid, which indicates an IC50 for each. The number of cells analyzed is indicated in the graph. The cells analyzed were from more than three batches of differentiation. Data presented represent MEAN +/− SEM.

2.5. Analysis of the Rescue Effects of Naloxone from Opiate Overdose

To simulate the clinical rescue of respiration depression by naloxone as in an opiate overdose situation, the effect of naloxone was assessed in the preBötC neurons after dosing with DAMGO, fentanyl, methadone and codeine. Naloxone (100 mM) was prepared in DMSO and further diluted in medium in these experiments to reach different concentrations. For each patched neuron, after the neuronal activity was maximumly inhibited by each opioid, puffs of naloxone at the indicated dosages (1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM) were added and the recovery of neural activity was analyzed. As shown in Figure 7, the neuronal activity silenced by the overdose of all four opioids could be recovered by naloxone. To ensure that any effect observed in these experiments was not the result of DMSO addition, two control experiments were performed. One was dosing of DMSO after DAMGO inhibition (Figure S3), mimicking the protocol for the rescue experiments. The other was recordings under repetitive addition of DMSO alone on preBötC neurons after medium dosing but without any opioid pre-treatment (Figure S4). DMSO treatment did not induce any change of neural activity in either experiment, confirming the observed changes were due to naloxone.

Figure 7.

IPSC-derived Pre-BotC neuronal response to Naloxone after neuronal inhibition induced by the overdose with DAMGO, Methadone, Fentanyl and Codeine. Sample traces of AP firing activity recorded under gapfree conditions demonstrated the baseline activity, inhibition induced by opioid overdose, and the rescue of AP activity by Naloxone. The opioid dosages utilized to induce overdose and the dosages of naloxone for each rescue are as listed in the figure.

The detailed dose-response effect of naloxone is presented for the overdose model as induced by DAMGO, but is representative of each opioid. After the complete or close-to-complete inhibition of neural activity by DAMGO, a series of naloxone dosages were tested on the recorded neurons with different starting dosages. A sample trace is shown in Figure S5A. Peak recovery was observed at 10 μM, and further addition of naloxone did not induce sustained or increased AP activity. Interestingly, higher dosages of Naloxone tended to induce significant depolarization, which halted neuronal activity, reminiscent of “depolarization block”, one of the hallmark features of putative rhythmogenic preBötC neurons.[82] Quantification of AP firing frequency was plotted at each naloxone dosage for 8 cells analyzed by patch clamp (Figure S5B). A peak recovery was observed at a certain naloxone dosage for each cell tested, irrespective of the starting dosages. Based on the analysis from multiple neurons, it was determined that 5 out 8 cells demonstrated the highest level of recovery in neural activity at naloxone dosages between 10~30 μM, while 3 out of 8 cells demonstrated highest recovery below 5 μM (Figure S5B). A plot of the maximum firing frequency (normalized to baseline frequency) with the correspondent naloxone dosage gave rise to the graph in Figure S5C, confirming the most efficient naloxone dose occurred at approximately 10 μM. However, 6 out of 8 neurons indicated a maximum recovery of activity over 100%, or higher than the original level. This overshoot induced by naloxone could potentially contribute to the relative hyperventilation observed following acute opioid reversal with naloxone during recovery from opioid overdose.[83]

3.0. Discussion

In this study, a de novo protocol was developed that successfully differentiated preBötC-like neurons from human iPSCs. The identity of these iPSC-preBötC-like neurons was validated by both biomarker expression and electrical functional analysis. Ideally, a transcriptomic comparison between these iPSC-derived neurons with human primary preBötC neurons would be desired for complete identity confirmation. However, it is currently not feasible due to the unavailability of the primary cells and the lack of transcriptomic data for these cell types.

A clinically relevant opioid overdose model was then developed for these iPSC-preBötC-like neurons to investigate the respiratory inhibition by mu-opioid receptor agonists as well as opioids important in clinical settings, and its rescue by the opioid antagonist naloxone. This is the first report describing in vitro generation of preBötC-like neurons from stem cells. These human neurons now provide a clinically relevant cellular tool for studying the regulation mechanisms of respiration under physiological and pathological conditions, such as opiate overdose, and for drug efficacy and toxicity testing.

The precise nature of the cellular and synaptic mechanisms underlying rhythmogenesis remains elusive. Currently there are two theories.[74] One early theory proposed intrinsic bursting pacemaker neurons[84] synchronized via excitatory synaptic connections.[85] The proportion of preBötC inspiratory neurons with voltage-dependent pacemaker properties is between 5% and 25%,[54] while a population of voltage-independent pacemaker neurons was also identified.[86] Later electrophysiological and modeling studies proposed a network driven hypothesis,[87, 88] in which the rhythm emerges through stochastic activation of intrinsic currents conveyed by recurrent synaptic connections, and randomly connected neuronal networks with synaptic dynamics (depression/facilitation) is sufficient to generate rhythmic activity.[89] In either case, excitatory synapses are required for rhythm generation. The inhibition of preBötC rhythmogenesis by opioids was proposed by enhancing the depression mechanism in the network.[10, 90] Immunocytochemistry analysis of the iPSC-preBötC cultures did reveal a majority of glutamatergic neurons mixed with a small portion of inhibitory neurons, which agrees with the network theory of depression/facilitation dynamics. These neurons expressed glutamate receptors based on immunocytochemistry and were responsive to glutamate as demonstrated by patch clamp analysis. The evidence suggests that this iPSC-preBötC model reproduces the physiological features of preBötC neurons, and would be a valuable platform for investigating inspiratory rhythogenesis, and its regulation by opioids and for opioid overdose rescue.

These hiPSC-derived preBötC-like neurons expressed the MOR and were responsive to four opioids; fentanyl, codeine, DAMGO and methadone, which then caused a decrease or cessation of neuronal activity in a dose-dependent manner. These effects are seen even in the absence of changes in CO2, O2, acidosis, and known cellular connections (e.g. RTN/pFRG) which are present and modulatory of the PreBötC in in vivo systems, confirming that PreBötC neurons are a direct target of opioid overdose. Moreover, this decreased activity was recovered by naloxone treatment. The IC50’s generated from the iPSC-preBötC-like neurons through patch clamp analysis were comparable with literature. Also, due to the absence of preBötC in vitro human models, most of the relevant research approaches this issue through competitive receptor binding assays in cell lines or membrane preparations.[91],[92] The functional assay in organotypic slices or local perfusion in animals also provides some information.[72, 93, 94] Both of the approaches are limited in their translation to clinical applications.

The details of the suggested dosages and those utilized in this study are listed as in Table 1. The IC50’s for codeine, methadone and fentanyl from this study are 2.74 μM, 31.68 nM and 3.59 nM, respectively. This is comparable with those identified from competitive μ-opioid receptor binding assays which were reported to be 3.2 μM, 15.9 nM and 10 nM.[91] The IC50 for DAMGO from our model is 9.0 μM. This is different from the results in the competitive receptor binding assay which was 2 nM, however, it is comparable to the effective dosage identified in a study with local perfusion of the preBötC complex in rats,[72] which indicated the DAMGO dosages for effective inspiration reduction at 5 μM, and for complete inspiration inhibition at 200 μM. The effective dosage for naloxone identified from our study was between 1~10 μM, with the maximal recovery at around 10 μM. This is also different from that reported from the competitive receptor binding assays which was reported to be approximately 5.9 nM.[91] However, it is comparable to that reported from a study utilizing rat preBötC brain slices which was 10 μM,[10] and much lower than that in a local brain stem perfusion study in rat which used 100 μM.[72] Therefore, it is apparent that the effective dosages for these drugs can differ dramatically based on selection of biological system and assay format, but suggests that values determined from in vivo models are more appropriate for comparison to the human cellular models.

Table 1.

List of modulatory compounds or drugs utilized in this study.

| Drug | Concentrations tested |

Dosing unit | Solvent | Product Information |

Suggested Working Conc. from literature |

Reference | system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAMGO | 0.5~70 μM | 0.5 μM, 5 μM | 5 mM in Medium | Sigma (Cat E7380) | 5 μM | [72] | Rat, preBötC brain |

| 0.2 μM, 0.5 μM, 1 μM | [10, 93] | Rat, preBötC brain slice | |||||

| Naloxone | 1~240 μM | 1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM | 100 mM in DMSO, further diluted in medium | Sigma (USP 1453005) | 100 μM | [72] | Rat, preBötC brain |

| 10 μM | [10] | Rat, preBötC brain | |||||

| 0.5mM | [94] | Decerebrated dogs | |||||

| Codeine Hydrochloride | 1~100 μM | 1 μM, 10 μM | 10 mM in H2O, further diluted in medium | NIDA 9050-001 | 1~100 μM | [91] | In vitro competitive binding assay |

| Methadone Hydrochloride | 10 ~1000 nM | 20 nM, 200 nM, 2000 nM | 20 mM in H2O, further diluted in medium | NIDA 9250-003 | 1~1000 nM | [91] | In vitro competitive binding assay |

| Fentanyl Hydrochloride | 0.02 ~ 600 nM | 0.02 nM, 0.2 nM, 2 nM, 20 nM, 200 nM | 10 mM in H2O, further diluted in medium | NIDA 9801-001 | 0.1~100 nM | [72, 91, 93] | Rat preBötC brain slice; in vivo CSF perfusion; In vitro competitive binding assay |

| SST | 1 μM | 1 μM | 0.1 mM in Medium | Sigma (S9129) | 1 μM | [80] | Mice, preBötC brain slice |

| Substance P | 5 μM | 5 μM | 0.5 mM in Medium | R&D (1156/5) | 1 μM | [79] | Mice, preBötC brain slice |

| ATP | 100 μM | 100 μM | 10 mM in Medium | Sigma (A2383) | 100 μM | [73] | Rat, preBötC brain slice |

Compared to the in vitro binding assay, which relies on the binding affinity to a specific opioid receptor subtype (usually MOR) for the generation of the IC50 for a particular opioid, the readout from this functional assay reflects a compound outcome integrating opioid binding to more than one type of opioid receptor (MOR and KOR in these cells). Each receptor has its own binding affinity, subcellular signaling pathways and a variety of biases depending on the agonist, as well as the interactions between these subcellular signaling pathways. Combined, this gives a more relevant translation of the subcellular signaling for each opioid to the electrophysiological readouts, which may also differ depending on the cell types. In addition to these more complex interactions, there are ongoing OR desensitization and recycling events during the whole cell functional analysis which is not present in in vitro binding assays. So, it is not surprising that there are some differences between the results derived from OR receptor binding assays and those from the iPSC-preBötC-like patch clamp assay, such as for DAMGO and naloxone, but maybe more predictive of in vivo human results. Actually, it is somewhat surprising that three clinic opioids (codeine, fentanyl, methadone) demonstrated comparable IC50 values in these two biological systems, further highlighting the validity of this functional assay.

Compared to organotypic slice models or in vivo models, which rely on the response of complicated neural circuits or a living organism for the readouts, the iPSC-preBötC-like system presented here analyzed the effects of opioids in a defined system where other potential complications involved in respiration regulation, such as the changes in CO2, O2, acidosis, and other known physiologic modulators of preBötC activity, as well as other known connections (e.g. RTN/pFRG, Kolliker-Fuse nucleus, parabrachial complex, locus coeruleus, etc) which are modulatory of preBötC function in in vivo systems, were not present. While this is a limitation of this iPSC- preBötC-like model, since it may not reproduce the overdose response at systematic level, it can also be an advantage, which allows the stepwise addition of these modulatory factors for mechanism investigation of their modulatory effect. on overdose and recovery.

This system also allows for many other possibilities for future investigations. The model can now be integrated with microelectode arrays for a more high-throughput system, which can subsequently be combined with other relevant organ mimics to understand organ-organ interactions in a multi-organ platform to model overdose and recovery.[95, 96] Drug-drug interactions can also be investigated as many analgesic adjuncts often co-prescribed with opioids, including benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, gabapentinoids, herbal supplement Kratom are increasingly recognized to increase the risk of OIRD and other concerns.[97-100] Clinically, certain patient risk factors such as obstructive sleep apnea may increase the risk of OIRD. This human-based in vitro iPSC-preBötC system can now provide an essential platform to build on for investigating issues such as drug-drug interactions or comorbidity/co-mortality.

4.0. Conclusion

These iPSC-preBötC-like neurons, with the capacity of simulating the regulation of respiration by opioid overdose and its subsequent rescue as seen in clinical situations, would be an invaluable bridge platform for drug screening between simple biomolecular assays and in vivo and clinical models, as well as for mechanistic investigation of ORID. It also supplies a new platform to investigate other effective long-lasting overdose rescue drugs, for opioid alternatives that do not have the respiratory inhibition effect or for opioid conjugates that may enhance respiration.

5.0. Experimental Section/Methods

Differentiation of preBötC neurons from hiPSC:

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were obtained from the Coriell Institute, Camden, NJ, from healthy subjects (line ND41865). The iPSCs were plated on Matrigel-coated plates and grown in TesR1 medium to 70% confluency. The cells were harvested with accutase and plated onto Vitronectin XF™ (Stem cell Technology, Cat 07180)-coated NC-plates (Stem cell Technology, Cat 27147) at a density of 1X103 cells mm−2 in TesR ™ -E8 medium containing 10 μM ROCK inhibitor (Y27632, R&D system) and cultured overnight. The following morning, the cells were fed with TesR ™ -E6 medium with a complete medium change. 24 hours later, the medium was changed to TesR ™ -E6 medium containing 200 ng ml−1 FGF8b (R&D, 423-F8-025). After another 24 hour period, the cells are replated utilizing accutase again, to detach the cells resuspended in TesR ™ -E6 containing 200 ng ml−1 FGF8b and 2 μM CHIR99021 (Tocris, Cat 4423) and re-seeded on VTN-NC-coated plates at a density of 1.5 × 103 cells mm−2 and 10 μM Y27632 was included during the re-seeding process. The medium was switched to TesR ™ -E6 plus 1 μM Retinoic Acid (RA, Sigma, R2625) after an additional 24 hours and this was counted as Day 0 of differentiation. The cells were fed with the same medium daily for 6 additional days. On Day 7, the feeding medium was switched to preBötC Neuronal Medium (PBNM), and then every two days with a whole medium change until Day 14. The cells were then harvested using Trypsin (0.05%) for replating or cryopreservation (P0). To further mature the cells, P0 cells were plated on ECL-coated plates at 250 cells mm−2 in PBNM medium, then fed every two days with PBNM with full medium change for 14 days. The cells were harvested with 0.05% Trypsin for further plating for analysis or cryopreservation (P1).

Immunocytochemistry analysis of preBötC culture:

Cells on the ECL-coated coverslips were fixed utilizing freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. Cells were then washed twice in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (pH 7.2, w/o Mg2+, Ca2+) for 10 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.1% triton X-100/PBS for 15 min. Non-specific binding sites were blocked using Blocking Buffer (5% Donkey serum plus 0.5% BSA in PBS) for 45 min at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After being washed with PBS 3x 10 min, the cells were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 2.5 hours at room temperature. The cells were again washed with PBS 3x for 10 min and mounted utilizing Vectashield with 4'-6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (dapi) (Vector laboratories, Inc.). Primary antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 2. Secondary antibodies include: Goat-anti-Mouse-568 (Invitrogen, 1:250), Goat-anti-Rabbit-488 (Invitrogen, 1:250), Goat-anti-Rabbit-568 (Invitrogen, 1:250), Donkey-anti-Gt-488 (Invitrogen, 1:250), Donkey anti sheep-568 (Invitrogen,1:250) and Goat anti Guinea pig −488 (Invitrogen 1:250). All antibodies were diluted in Blocking Buffer.

Table 2.

Primary antibodies utilized in this study.

| Antibody | Cat No. | Species | Company | Dilution Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NANOG | Ab62734 | Mouse | Abcam | 1:200 |

| SOX2 | Ab137385 | Rabbit | Abcam | 1:200 |

| HOXA1 | AF5014 | Goat | R&D systems | 1:20 |

| HOXB1 | AF6318 | Sheep | R&D systems | 1:20 |

| HOXC4 | 14321-1-AP | Rabbit | Thermo fisher | 1:200 |

| HOXD1 | Ab220856 | Rabbit | Abcam | 1:100 |

| MOR | Ab10275 | Rabbit | Abcam | 1:800 |

| NK1R | 694501 | Mouse | Novus biologicals | 1:500 |

| GFAP | AB5804 | Rabbit | Sigma Aldrich | 1:1000 |

| MAP2 | MA5-12826 | Mouse | ThermoFisher | 1:1000 |

| vGLUT2 | AB2251-I | guinea pig | Sigma Aldrich | 1:400 |

| GABA | A2052 | Rabbit | Sigma Aldrich | 1:1000 |

| SST | MAB2358 | Mouse | R&D | 1:500 |

| vGluR2/3 | AB1506 | Rabbit | Abcam | 1:500 |

Electrophysiological data acquisition and analysis of hiPSC derived preBötC neurons:

For whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, the current-clamp and voltage-clamp recordings were carried out using a Zeiss, upright microscope (Axioscope, FS2, Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a multiclamp 700B amplifier. Borosilicate glass patch pipettes (BF 150-86-10; Sutter Instrument Company), with a resistance of 6 to 10 MΩ, were made using a Sutter P97 pipette puller (Sutter Instrument Company). The pipette (intracellular) solution contained 140 mM K-gluconate, 4 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM Na2ATP, 5 mM HEPES base, and 5 mM HEPES acid. The pH and osmolarity were adjusted to 7.2 and 280 mOsmole, respectively. The PBNM medium was used as the extracellular solution for all patch-clamp experiments. Following the formation of a Giga-Ω seal and membrane puncture, the cell capacitance was compensated. Signals were filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz with a Digidata 1322A interface (Axon Instruments). Data recording and analysis were performed using the pClamp10 software (Axon Instruments). Membrane potentials were corrected by subtraction of a 15 mV tip potential, which is the liquid junction potential between intracellular solution and extracellular solution and was calculated using Axon's pClamp10 program.

The neuronal electrophysiological activity was evaluated from 20 to 40 days old cells. Cultured neurons maintained on glass coverslips were placed in the recording chamber of the microscope. The preBötC neurons in culture were distinguished from non-neuronal cells visually. Large cells with bright somas were identified as preBötC neurons. Sodium and potassium currents were measured using a voltage-clamp protocol of 15 pulses from −20 to +120 mV separated by 10 mV, while the holding voltage was −70 mV as detailed previously.[101] Whole-cell capacitance and series resistance was compensated and a p/6 protocol was used. The access resistance was less than 20 MΩ. Induced single and repetitive action potentials (APs) were recorded in current-clamp mode utilizing 1-second depolarizing current injections from a −70 mV holding potential. Other parameters in the protocol were optimized during the recording due to cell to cell variations. Spontaneous activity was recorded in gap-free mode. The data were analyzed using pClamp 10 software (Axon Instrument, Foster City, CA, USA) and quantified using Microsoft Excel.

Testing of opioids and naloxone effect by patch clamp:

The electrophysiological properties of hiPSC- preBötC neuron’s response to different modulators or chemicals were analyzed through patch-clamp. Drugs were administered only on the spontaneously active cells and recorded in gap-free mode. For drug treatment, fentanyl, methadone, codeine, DAMGO, and Naloxone were administered with incremental dosages through pipetting in at different unit dosages as listed in Table 1 starting at a smaller unit dosage, and electrical firing activity was recorded for tens of seconds after each dosing. Additional doses at the same or higher unit concentrations would be applied sequentially until the firing activity was maximumly inhibited. For example, the dosing of DAMGO was initiated with 0.5 μM unit sizes, then increased to several 5 μM doses each, and the final concentration in the bath was up to 278 μM. To generate the IC50s for the opioid drugs, the electrical firing activity of hiPSC- preBötC neurons was recorded at a series of dosages in the ranges described in Table 1. The action potential frequency within a particular dosing period was calculated and plotted against the correspondent dosage in Excel. The dose-response curves were generated by curve fitting and the IC50 was then calculated.

Preparation of drugs utilized for dosing preBötC neurons:

All the modulatory chemicals tested in the patch clamp experiments are listed in Table 1. All drugs were prepared by dissolving the chemicals into correspondent solvents and further diluted in PBNM medium to create different working stocks as needed. For incremental dosing during patch clamp, drug doses at different unit concentrations were prepared to establish final concentrations in the chamber.

Curve-fitting for the dose-response curve of opioids:

The firing rates collected from the patch clamp recording of each cell were first normalized to the baseline activity of the same cell. The normalized firing rates were then fit to a sigmoidal dose-response curve utilizing two parameters: the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and Hill coefficient (h). Non-linear regression was performed using least-squares to simultaneously fit the IC50 and Hill coefficient. In cases when the highest dose did not fully abolish activity, a third parameter describing the activity level at full inhibition was included into the model.

Statistical Information:

All the data were collected from three or more batches of experiments. The statistics for all the quantified data have been described specifically in each graph.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Authors Xiufang Guo and Nesar Akanda contributed equally to this work.

Funding:

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant number 1UG3TR003081-01.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Competing interests: The authors confirm that competing financial interests exist but there has been no financial support for this research that could have influenced its outcome. The only author with competing interest is J.J.H. who has ownership interest and is Chief Scientist and member of the Board of Directors in a company that may benefit financially as a result of the outcomes of the research or work reported in this publication.

Contributor Information

Xiufang Guo, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA.

Nesar Akanda, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA.

Gabriella Fiorino, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA.

Siddharth Nimbalkar, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA.

Christopher J. Long, Hesperos Inc. 12501 Research Parkway, Suite 100, Orlando, FL 32826. USA

Alisha Colon, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA.

Aakash Patel, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA.

Patrick J. Tighe, University of Florida, College of Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, 1600 SW Archer Road, Gainesville, FL. 32610. USA.

James J. Hickman, University of Central Florida, NanoScience Technology Center, 12424 Research Parkway, Suite 400, Orlando, Florida, 32826. USA; Hesperos Inc. 12501 Research Parkway, Suite 100, Orlando, FL 32826. USA

Data availability:

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. The iPSC line (ND41865) utilized for preBötC neuron differentiation was under the restriction of an MTA with the Coriell Institute. The opioid drugs (fentanyl, methadone, morphine, codeine), which are level II DEA controlled substances, were purchased and utilized under the regulations required in our DEA license.

References

- [1].Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, and Matthew Gladden R, Am. J. Transplant 2016, 16, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wilson N KM, Seth P, Smith H IV, Davis NL, MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 2020, 69, 290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pattinson KT, Br. J. Anaesth 2008, 100, 747–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anderson TM, Garcia AJ, Baertsch NA, Pollak J, Bloom JC, Wei AD, Rai KG, and Ramirez J-M, Nature 2016, 536, 76–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Feldman JL, Negro CAD, and Gray PA, Annu. Rev. Physiol 2013, 75, 423–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Anderson T, and Ramirez J, F1000Research 2017, 6, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Smith J, Ellenberger H, Ballanyi K, Richter D, and Feldman J, Science 1991, 254, 726–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Thoby-Brisson M, Karlén M, Wu N, Charnay P, Champagnat J, and Fortin G, Nat. Neurosci 2009, 12, 1028–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Del Negro CA, Funk GD, and Feldman JL, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2018, 19, 351–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mellen NM, Janczewski WA, Bocchiaro CM, and Feldman JL, Neuron 2003, 37, 821–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Erbs E, Faget L, Scherrer G, Matifas A, Filliol D, Vonesch J-L, Koch M, Kessler P, Hentsch D, Birling M-C, Koutsourakis M, Vasseur L, Veinante P, Kieffer BL, and Massotte D, Brain Structure and Function 2015, 220, 677–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cerritelli S, Hirschberg S, Hill R, Balthasar N, and Pickering AE, PLoS One 2016, 11, e0153187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tan W, Janczewski WA, Yang P, Shao XM, Callaway EM, and Feldman JL, Nat. Neurosci 2008, 11, 538–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bachmutsky I, Wei XP, Kish E, and Yackle K, eLife 2020, 9, e52694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gray PA, Janczewski WA, Mellen N, McCrimmon DR, and Feldman JL, Nat. Neurosci 2001, 4, 927–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ramirez JM, Schwarzacher SW, Pierrefiche O, Olivera BM, and Richter DW, The Journal of Physiology 1998, 507, 895–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Muñoz-Ortiz J, Muñoz-Ortiz E, López-Meraz L, Beltran-Parrazal L, and Morgado-Valle C, Neurología (English Edition) 2018, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ringwalt C, Sanford C, Dasgupta N, Alexandridis A, McCort A, Proescholdbell S, Sachdeva N, and Mack K, Health promotion practice 2018, 19, 747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jones MR, Viswanath O, Peck J, Kaye AD, Gill JS, and Simopoulos TT, Pain Ther 2018, 7, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dahan A, Aarts L, and Smith TW, Anesthesiology 2010, 112, 226–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dahan A, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olievier C, Nieuwenhuijs D, Matthes HW, and Kieffer BL, Anesthesiology 2001, 94, 824–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Romberg R, Sarton E, Teppema L, Matthes HW, Kieffer BL, and Dahan A, Br. J. Anaesth 2003, 91, 862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Contet C, Kieffer BL, and Befort K, Curr Opin Neurobiol 2004, 14, 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bruchas MR, Land BB, and Chavkin C, Brain Res 2010, 1314, 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pellissier LP, Pujol CN, Becker JAJ, and Le Merrer J, Handb Exp Pharmacol 2018, 247, 227–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, and Davidson PJ, MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 2015, 64, 631–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mueller SR, Walley AY, Calcaterra SL, Glanz JM, and Binswanger IA, Subst. Abus 2015, 36, 240–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Foldes FF, Med. Clin. North Am 1964, 48, 421–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chou R, Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Coffin PO, Griffin JC, Davis-O'Reilly C, Grusing S, and Daya M, Ann. Intern. Med 2017, 167, 867–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Clark AK, Wilder CM, and Winstanley EL, J. Addict. Med 2014, 8, 153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lambdin BH, Bluthenthal RN, Wenger LD, Wheeler E, Garner B, Lakosky P, and Kral AH, MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 2020, 69, 1117–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cosgrave D, Vencken S, Galligan M, McGuinness S, Soukhin E, McMullan V, Nair S, Puttappa A, Boylan J, Hussain R, Conlon N, Doran P, and Nichol A, Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Takahashi M, Sugiyama K, Hori M, Chiba S, and Kusaka K, J Anesth 2004, 18, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim HK, and Nelson LS, J. Med. Toxicol 2016, 12, 107–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Monitto CL, Kost-Byerly S, White E, Lee CK, Rudek MA, Thompson C, and Yaster M, Anesth. Analg 2011, 113, 834–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].He F, Jiang Y, and Li L, Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Scali ST, Kim M, Kubilis P, Feezor RJ, Giles KA, Miller B, Fatima J, Huber TS, Berceli SA, Back M, and Beck AW, J. Vasc. Surg 2018, 67, 409–423.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Acher CW, Wynn MM, and Archibald J, Surgery 1990, 108, 755–61; discussion 761-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hutchinson MR, Lewis SS, Coats BD, Rezvani N, Zhang Y, Wieseler JL, Somogyi AA, Yin H, Maier SF, Rice KC, and Watkins LR, Neuroscience 2010, 167, 880–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang X, Zhang Y, Peng Y, Hutchinson MR, Rice KC, Yin H, and Watkins LR, Br. J. Pharmacol 2016, 173, 856–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Anttila JE, Albert K, Wires ES, Mätlik K, Loram LC, Watkins LR, Rice KC, Wang Y, Harvey BK, and Airavaara M, eNeuro 2018, 5, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hutchinson MR, Zhang Y, Brown K, Coats BD, Shridhar M, Sholar PW, Patel SJ, Crysdale NY, Harrison JA, Maier SF, Rice KC, and Watkins LR, Eur. J. Neurosci 2008, 28, 20–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bachtell R, Hutchinson MR, Wang X, Rice KC, Maier SF, and Watkins LR, CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 692–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Herz A, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997, 129, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wise RA, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 1980, 13 Suppl 1, 213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Martin WR, Ann. Intern. Med 1976, 85, 765–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen MH, Xie L, Liu TW, Song FQ, and He T, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand 2006, 50, 1125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rothstein RJ, Niemann JT, Rennie CJ 3rd, Suddath WO, and Rosborough JP, Ann. Emerg. Med 1985, 14, 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wermeling DP, Ther Adv Drug Saf 2015, 6, 20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wang X, Hayes JA, Revill AL, Song H, Kottick A, Vann NC, LaMar MD, Picardo MCD, Akins VT, Funk GD, and Del Negro CA, eLife 2014, 3, e03427–e03427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hayes JA, Wang X, and Del Negro CA, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 8286–8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ruangkittisakul A, Kottick A, Picardo MCD, Ballanyi K, and Del Negro CA, Physiol Rep 2014, 2, e12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ge Q, and Feldman JL, The Journal of physiology 1998, 509 ( Pt 1), 255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pagliardini S, Adachi T, Ren J, Funk GD, and Greer JJ, J. Neurosci 2005, 25, 2591–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lee DS, Law PY, Ln W, Loh HH, Song KY, and Choi HS, Biomed Rep 2017, 6, 532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schattauer SS, Kuhar JR, Song A, and Chavkin C, Cell Signal 2017, 32, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schattauer SS, Miyatake M, Shankar H, Zietz C, Levin JR, Liu-Chen LY, Gurevich VV, Rieder MJ, and Chavkin C, J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 41595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Schwarzacher SW, Rüb U, and Deller T, Brain 2010, 134, 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ramirez J-M, Brain 2010, 134, 8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lippmann Ethan S., Williams Clay E., Ruhl David A., Estevez-Silva Maria C., Chapman Edwin R., Coon Joshua J., and Ashton Randolph S., Stem Cell Reports 2015, 4, 632–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kirkeby A, Grealish S, Wolf Daniel A., Nelander J, Wood J, Lundblad M, Lindvall O, and Parmar M, Cell Reports 2012, 1, 703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Krumlauf R, Cell 1994, 78, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Philippidou P, and Dasen JS, Neuron 2013, 80, 12–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Liu YY, Ju G, and Wong-Riley MT, J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001, 91, 1387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Baertsch NA, Baertsch HC, and Ramirez JM, Nature Communications 2018, 9, 843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Gray PA, Rekling JC, Bocchiaro CM, and Feldman JL, Science 1999, 286, 1566–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cui Y, Kam K, Sherman D, Janczewski WA, Zheng Y, and Feldman JL, Neuron 2016, 91, 602–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Picardo MC, Weragalaarachchi KT, Akins VT, and Del Negro CA, J Physiol 2013, 591, 2687–2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gray PA, Janczewski WA, Mellen N, McCrimmon DR, and Feldman JL, Nat. Neurosci 2001, 4, 927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Tupal S, Rieger MA, Ling GY, Park TJ, Dougherty JD, Goodchild AK, and Gray PA, Eur. J. Neurosci 2014, 40, 3067–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Koizumi H, Koshiya N, Chia JX, Cao F, Nugent J, Zhang R, and Smith JC, J. Neurosci 2013, 33, 2994–3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Montandon G, Qin W, Liu H, Ren J, Greer JJ, and Horner RL, The Journal of Neuroscience 2011, 31, 1292–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lorier AR, Lipski J, Housley GD, Greer JJ, and Funk GD, The Journal of physiology 2008, 586, 1429–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Feldman JL, and Del Negro CA, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2006, 7, 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lalley PM, Pilowsky PM, Forster HV, and Zuperku EJ, The Journal of physiology 2014, 592, 1163–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hayes JA, and Negro CAD, J. Neurophysiol 2007, 97, 4215–4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Peña F, and Ramirez J-M, The Journal of Neuroscience 2004, 24, 7549–7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ptak K, Yamanishi T, Aungst J, Milescu LS, Zhang R, Richerson GB, and Smith JC, The Journal of Neuroscience 2009, 29, 3720–3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Yeh S-Y, Huang W-H, Wang W, Ward CS, Chao ES, Wu Z, Tang B, Tang J, Sun JJ, van der Heijden M. Esther, Gray PA, Xue M, Ray RS, Ren D, and Zoghbi HY, Neuron 2017, 94, 294–303.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ramírez-Jarquín JO, Lara-Hernández S, López-Guerrero JJ, Aguileta MA, Rivera-Angulo AJ, Sampieri A, Vaca L, Ordaz B, and Peña-Ortega F, Peptides 2012, 34, 360–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Montandon G, Liu H, and Horner RL, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 32707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Gray PA, Hayes JA, Ling GY, Llona I, Tupal S, Picardo MCD, Ross SE, Hirata T, Corbin JG, Eugenín J, and Del Negro CA, The Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30, 14883–14895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Heather Powell GLP, US Pharmacist 2019, 44, HS2–HS8. [Google Scholar]

- [84].Johnson SM, Smith JC, Funk GD, and Feldman JL, J. Neurophysiol 1994, 72, 2598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Koshiya N, and Smith JC, Nature 1999, 400, 360–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Peña F, Parkis MA, Tryba AK, and Ramirez JM, Neuron 2004, 43, 105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Rekling JC, Shao XM, and Feldman JL, The Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 20, RC113–RC113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Del Negro CA, Morgado-Valle C, Hayes JA, Mackay DD, Pace RW, Crowder EA, and Feldman JL, The Journal of Neuroscience 2005, 25, 446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Guerrier C, Hayes JA, Fortin G, and Holcman D, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 9728–9733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Wei AD, and Ramirez J-M, Front. Physiol 2019, 10, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Volpe DA, McMahon Tobin GA, Mellon RD, Katki AG, Parker RJ, Colatsky T, Kropp TJ, and Verbois SL, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 2011, 59, 385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Emmerson PJ, Liu MR, Woods JH, and Medzihradsky F, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1994, 271, 1630–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Homma I, Onimaru H and Fukuchi Y, Editors. Indirect Opioid Actions on Inspiratory pre-Bötzinger Complex Neurons in Newborn Rat Brainstem Slices. Proceedings of the New Frontiers in Respiratory Control, (2010) 2010//; New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- [94].Mustapic S, Radocaj T, Sanchez A, Dogas Z, Stucke AG, Hopp FA, Stuth EAE, and Zuperku EJ, J. Neurophysiol 2010, 103, 409–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Oleaga C, Bernabini C, Smith AST, Srinivasan B, Jackson M, McLamb W, Platt V, Bridges R, Cai Y, Santhanam N, Berry B, Najjar S, Akanda N, Guo X, Martin C, Ekman G, Esch MB, Langer J, Ouedraogo G, Cotovio J, Breton L, Shuler ML, and Hickman JJ, Sci Rep 2016, 6, 20030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Oleaga C, Lavado A, Riu A, Rothemund S, Carmona-Moran CA, Persaud K, Yurko A, Lear J, Narasimhan NS, Long CJ, Sommerhage F, Bridges RL, Cai Y, Martin C, Schnepper MT, Goswami A, Note R, Langer J, Teissier S, Cotovio J, and Hickman JJ, Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29, 1805792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Li Y, Delcher C, Wei YJ, Reisfield GM, Brown JD, Tighe P, and Winterstein AG, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 2020, 108, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Antoniou T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, and van den Brink W, PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, and Bohnert AS, BMJ 2015, 350, h2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Torrance N, Veluchamy A, Zhou Y, Fletcher EH, Moir E, Hebert HL, Donnan PT, Watson J, Colvin LA, and Smith BH, Br. J. Anaesth 2020, 125, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Akanda N, Molnar P, Stancescu M, and Hickman JJ, Journal of Biomolecular Screeing 2009, 14, 1228–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. The iPSC line (ND41865) utilized for preBötC neuron differentiation was under the restriction of an MTA with the Coriell Institute. The opioid drugs (fentanyl, methadone, morphine, codeine), which are level II DEA controlled substances, were purchased and utilized under the regulations required in our DEA license.