Abstract

Introduction:

There is a requirement for health and care systems and services to work on an equitable basis with people who use and provide integrated care. In response, co-production has become essential in the design and transformation of services. Globally, an array of approaches have been implemented to achieve this. This unique review explores multi-context and multi-method examples of co-production in integrated care using an exceptional combination of methods.

Aim:

To review and synthesise evidence that examines how co-production with service users, unpaid carers and members of staff can affect the design and transformation of integrated care services.

Methods:

Systematic review using meta-ethnography with input from a patient and public involvement (PPI) co-production advisory group. Meta-ethnography can generate theories by interpreting patterns between studies set in different contexts. Nine academic and four grey literature databases were searched for publications between 2012–2022. Data were extracted, analysed, translated and interpreted using the seven phases of meta-ethnography and PPI.

Findings:

A total of 2,097 studies were identified. 10 met the inclusion criteria. Studies demonstrated a variety of integrated care provisions for diverse populations. Co-production was most successful through person-centred design, innovative planning, and collaboration. Key impacts on service transformation were structural changes, accessibility, and acceptability of service delivery. The methods applied organically drew out new interpretations, namely a novel cyclic framework for application within integrated care.

Conclusion:

Effective co-production requires a process with a well-defined focus. Implementing co-delivery, with peer support, facilitates service user involvement to be embedded at a higher level on the ‘ladder of co-production’. An additional step on the ladder is proposed; a cyclic co-delivery framework. This innovative and operational development has potential to enable better-sustained person-centred integrated care services.

Keywords: co-production, co-delivery, patient and public involvement, meta-ethnography, integrated care design and transformation

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended health and care systems partner with service users to create a culture that allows for the co-production of healthcare outcomes [1]. Integrated care services have progressed this recommendation, moving services from working alongside users as passive recipients of care, to active involvement in the development and design of service provision [2]. Recent legislation and guidance around co-production supports this progress, including the European Commission‘s technical dossier for the role of citizens in governance and service delivery [3], the WHO’s principles of integrated care [4] and the Care Act in England [5]. Co-production is acknowledged as an approach where professionals share power and have an equal partnership with people to plan, design and evaluate together [6].

There are many definitions of integrated care [7]. Defined as a global principle to improve patient access and outcomes by organisations delivering services in a joined-up and person-centred way [8], integration can be horizontal (between providers at the same level) or vertical (between providers at different levels), aligning governance structures, budgets and planning approaches [9,10]. The clinical advantages of integrated care have been identified as; better detection of illness, improvement in overall health outcomes and patient experience [11].

Co-production within integrated care recognises that knowledge from service users and providers is essential [12], it supports people with long-term health conditions [13], affects quality improvement [14] and is crucial in mitigating health inequalities [15]. Co-production of change processes generate a wide array of ideas to improve the service user experience across multiple settings [16]. Questions remain regarding the contexts in which co-production is impactful [17,18], as successful outcomes depend on the setting and subjective experiences of those involved [19,20]. While co-production within integrated care is significant to health and care development globally [21], there remains a shortfall of evidence about its impact, with few studies incorporating primary data collection.

Integrated care is too complex for a one-size-fits-all solution [7]. Co-production has the promise of delivering tailored integrated care services [22,23]. For success in a system approach, the needs of all stakeholders including service users and carers must be considered [12,16]. While involving service users throughout a whole-system transformation is a key mechanism for change [24], there is complexity in implementing co-production at a systems level [25,26]. Two key barriers to understanding how to embed co-production within a health and care system include insufficient knowledge of evidence-based methods [23,27], and a lack of preparation to embed into existing structures [18,19,28,29].

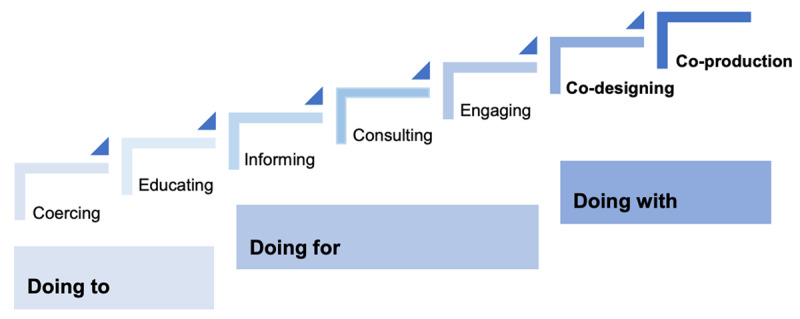

‘True’ co-production is part of a continuum of participation, derived from the work of Arnstein [30] and often analogised in literature as a ‘ladder of co-production’ (Figure 1). This conceptualisation interprets co-production as an approach for organisations to share power between citizens, service users, professionals and decision-makers [31,32]. Equalising power through co-production enables service users and carers to act as experts in their conditions and circumstances, and to use this lived experience to develop models of service design and delivery [33,34].

Figure 1.

A depiction of the ladder of co-production [35].

This paper aims to review and synthesise evidence that examines how co-production with service users, unpaid carers and members of staff, can affect the design and transformation of integrated care services.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted using meta-ethnography together with patient and public involvement (PPI) to explore and synthesise the data. Meta-ethnography is a seven-phase process proposed by Noblit and Hare [36]. It was selected for its ability to add an additional level of interpretation of primary qualitative studies, along with its capability to deliver a comparison of the complexities of co-production across various global contexts [37]. It also enables the full in-depth involvement of a PPI group across the phases; as recommended in eMERGe guidelines for meta-ethnographies [38]. This paper follows the eMERGe reporting guidance [39]: phase 1 is the introduction; phase 2 through phase 6 detail the methods and findings; phase 7 forms the discussion.

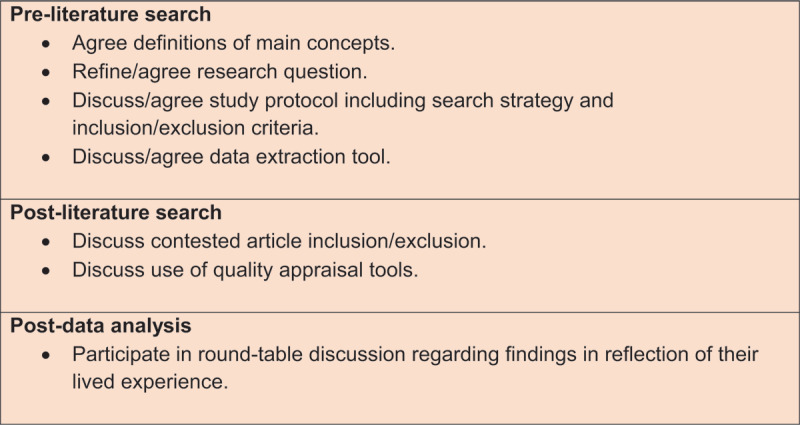

A Co-production Advisory Group (CAG) of six members was formed comprising service users (n = 2), unpaid carers (n = 2) and members of staff (n = 2) who use and/or provide health and care services within one integrated care system in England. They were recruited through a local Healthwatch network via newsletter and word of mouth. Those interested received an information sheet, and completed a simple application form providing their background and experience of co-production within integrated care. The group met three times with additional email and telephone communications, and were remunerated for their contribution. The lead author facilitated meetings and one co-author (RI) represented a member of staff in the group. Figure 2 depicts key tasks performed by CAG members.

Figure 2.

CAG action log.

Search strategy

The SPICES framework was used to develop the research question and guided the search strategy [40] (Table 1).

Table 1.

SPICES framework and resulting research question.

|

| |

|---|---|

| SPICES HEADINGS | REVIEW CONCEPT |

|

| |

| Setting | Health and care services within integrated care |

|

| |

| Perspective | Service users, unpaid carers, members of staff |

|

| |

| Intervention | Co-production |

|

| |

| Comparison | Hypothetically, prior to/without co-production |

|

| |

| Evaluation | The design and transformation of service provision |

|

| |

| Social science method | Qualitative and mixed method |

|

| |

| Research question: | How has co-production with service users, unpaid carers and members of staff impacted the design and transformation of integrated health and care services? |

|

| |

Nine academic and four grey literature databases were electronically searched for results published between March 2012 and March 2022, applying the search terms derived from SPICES and guidance from CAG members. These incorporated CINAHL, Cochrane, MEDLINE, Web of Science Core Collection, KCI-Korean, SciELO, Proquest Central, PubMed Central and SAGE Journals, HMIC, NICE, Nuffield Trust and Social Care Online. Search terms included keywords and Boolean operators (‘AND’, ‘OR’) (Appendix A).

Two authors (SC, RI) screened title and abstracts as per exclusion criterion (Appendix B) to exclude off-topic studies applying Covidence software [41]. Where disagreement occurred, consensus was achieved through discussion. Studies were excluded if they did not demonstrate search terms according to CAG agreed conceptual definitions (Appendix C).

Full-text screening involved two stages. First, CAG members each examined two studies against the inclusion criteria. Second, four co-authors (SC, RI, KW, CFS) met to discuss each source in light of CAG members’ views. One author (SC) hand searched reference lists for further studies.

Studies were critically appraised for methodological and conceptual quality [42]. Two tools were tested, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [43], and TAPUPAS framework for quality assessment [44]. Three authors (SC, RI, KW) conducted the appraisal and agreed the TAPUPAS framework provided a more accurate test for quality than CASP. Studies scoring <7 points using TAPUPAS were excluded.

Data extraction

A data extraction tool was designed by co-authors and CAG members. Two co-authors (SC, RI) performed data extraction. Information and direct citations were extracted from each study. The lead author identified emerging concepts from studies and scored the extent of co-production processes through applying the Ladder of Co-production developed by Think Local Act Personal [45] and the Spectrum of Involvement recommended by NHS England and NHS Improvement [46] respectively (Appendix D). Higher scores indicated more active involvement and influence on design and transformation decisions by service users, carers and members of staff in co-production.

Data analysis

Analysis of concepts of the studies, in order of publication date, was completed by two authors (SC, RI) to determine key themes. Study comparison was separated by aspects of ‘design’ and ‘transformation’. Once broad themes were established across studies, the original texts were analysed by three authors (SC, RI, KW). Findings were visually produced to present to co-authors and CAG members.

Data translation and synthesis

A 90-minute roundtable discussion with CAG members provided findings in reflection of their lived experience. Two co-authors (SC, RI) presented their early impressions of findings, showing study examples to ensure discussions were rooted in context. Key concepts were identified through the discussion transcript. Concepts were compared with data analysis findings through reciprocal analysis (studies and concepts showing similarities) and refutational analysis (exploration of contradictions). Syntheses of findings were completed through analysis, translation and interpretation of themes. This process involved the lead author presenting themes and translations to the co-authors who shared interpretations of findings and came to a consensus on final interpretations.

Findings

2,097 papers were identified, of these 1,904 were imported into Covidence which removed 760 duplicates. 191 sources were manually sifted, 243 were full-text-screened, resulting in 21 studies for review and discussion. Ten studies remained, with one additional study meeting inclusion criteria from hand searching. 11 studies were critically appraised for quality; one was excluded (Appendix E).

Study characteristics

Table 2 displays key characteristics of included studies published between 2015 and 2021, across a range of countries and integrated care provisions. Differences were present in the scale of co-production, ranging from accessing a pathway (e.g. cancer screening) [47] to development of a full integrated care system [48]. Models of co-production included co-design [22,49,50,51,52,53], co-delivery [22,47,52,54,55], peer support [22,47,51,54], and co-production along with a quality improvement (QI) framework [49,50,52,54].

Table 2.

Included studies.

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMARY AUTHOR | PUBLICATION COUNTRY | INTEGRATED CARE PROVISION | CO-PRODUCTION MODEL(S) |

|

| |||

| Kamvura [55] | Zimbabwe | Depression, diabetes, hypertension | Theory of Change Co-delivery |

|

| |||

| Bruns [22] | South Africa | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Co-design Peer support Co-delivery |

|

| |||

| Sarkadi [52] | Sweden | Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders | Co-design Co-delivery QI |

|

| |||

| Yadav [53] | Australia (conducted in Nepal) | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | Co-design |

|

| |||

| Wolstenholme [51] | England | Hepatitis C virus | Co-design Peer support |

|

| |||

| O’Donnell [50] | Ireland | Frailty | Co-design QI |

|

| |||

| Eriksson [47] | Sweden | Cervical cancer screening | Representative co-production Peer support Co-delivery |

|

| |||

| Lalani [48] | England | Ealy integrated care system | Public committee |

|

| |||

| Van Deventer [49] | South Africa | Childhood malnutrition | Experienced-based co-design QI |

|

| |||

| Flora [54] | Canada | Psychiatry | Continuous improvement committees Peer support QICo-delivery |

|

| |||

Table 3 (Additional file) shows further study characteristics. Disparity was seen in the temporality of the co-production processes (eight months to three years). The aims of integrated care, co-production, and key outcomes of co-production were extracted for comparison. Most assessed outcomes qualitatively such as systemic changes (e.g. a strategy, intervention or pathway design, relational or capacity building), while some quantitively measured outcomes.

Table 4 (Additional file) re-orders studies from highest to lowest according to their accumulated score using the ladder depictions [45,46]. One study scored the highest (12 points) [47], one the lowest (six points) [48], with the remaining eight studies scoring nine, 10 and 11 points. This order was used to identify any links between the extent of co-production and data extracted.

Findings from the re-order showed two promising links. In exploring the scale of the co-production (size of the health/care provision), one study [48] exploring co-production within an integrated care system scored the lowest, while co-production of access to a cancer screening programme scored the highest [47]. The second link was between the extent of co-production and the model of co-production; the five studies that had a ‘co-delivery’ model [22,47,52,54,55], and the four studies with ‘peer support’ [22,47,51,54] scored within the highest ranked studies.

Table 4 further details numbers of service users, carers and members of staff involved in co-production, demographics, evidence of equity, and evaluation techniques. There was a lack of detailed information across studies which did not support an in-depth understanding of how co-production impacted integrated care design and transformation.

Table 5 (Additional file) shows definitions of co-production which were similar, featuring the bringing together of various actors working collaboratively and equitably using solution-focused approaches. A variety of facilitators, barriers and recommendations are shown. A universal barrier was time and resource constraints challenging the commitment and focus of those involved. Other data includes methods of co-production, who was involved, recruitment strategies, and equalising factors between members.

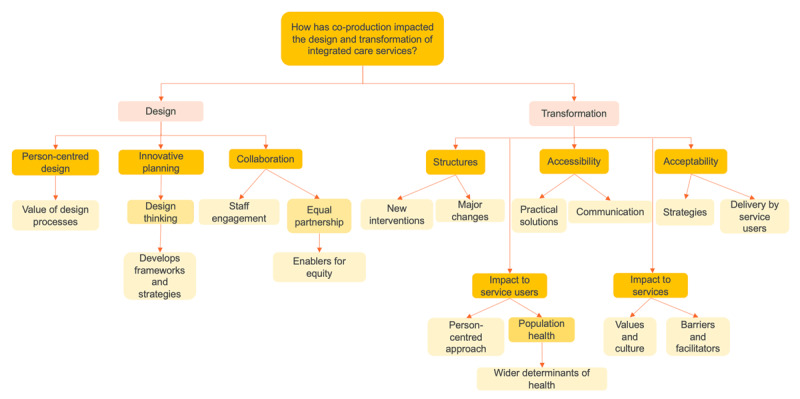

Key themes: design and transformation

Thematic analysis resulted in emergence of two categories: ‘design’ and ‘transformation’ (Figure 3). Design related to the act of developing new service processes in co-production with service users, carers and members of staff, whilst transformation related to implementation and outcome of co-produced changes.

Figure 3.

Analysis themes.

Design

Three impacts of co-production on design of integrated care services were identified; person-centred design, innovative planning and collaboration. Challenges and requirements for co-producing design were also drawn from the studies.

Person-centred design

Most studies explicitly discussed the importance of service users bringing expertise from their experience in accessing and using services [22,47,48,52,53,55].

“The […] design approach ensured empathy in understanding how men living with HIV in South Africa experience the world […]. This depth of empathy also empowered decision-makers [to] achieve better outcomes and [it] allowed for robust, rapid evaluations of prototypes.” [22: 241]

Person-centred design was described as a vital ingredient [22], with service user input seen as a resource [49], and, as a strategy to reduce health inequalities [47].

Innovative planning

Co-production supported development and use of strategies and frameworks within service design. These delivered sustainability of design as well as ensuring co-production processes could be embedded and flexible [50,54,55].

“As phased implementation of the pathways is ongoing, the service and quality improvement initiatives […] are being evaluated using a Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) process. This will generate an iterative process […] whereby the co-designed models of care are continually adapted to the context […].” [50: 4]

Strategies included frameworks of design e.g. journey mapping [22,47,53], developing personas [22,51], design thinking techniques, i.e. democratic dialogue [50], and imaginative questioning [47]. Each approach shaped the process of co-production, supporting accessibility [51], inclusion [55], and collaboration between different groups [49].

Collaboration

Collaboration within co-production allowed equity between stakeholders at varying levels and roles within integrated care [22,49,50,54]; studies highlighted enablers for equality [47,50,53,54]. For example, clinical staff rotated their involvement to ensure a higher proportion of public and patient representatives at meetings, to amplify their voice and input [50]. Co-production impacted engagement of staff members and supported collaboration [47,49,52,53]. In one study [49] staff were emotional regarding motives for working in healthcare, their organisation was humbled by how staff discussed service improvements.

Challenges

Challenges of co-producing service design were highlighted through learning and requirements [47,48,49,51,52]. The independent evaluation of an early integrated care system [48], was the only study to face a disproportionate number of barriers to facilitators. Co-production was intended across the whole system, but only implemented at smaller scales. This study showed:

Co-production could be undermined within financial restraints.

Health professionals struggled to work in partnership with service users and felt threatened by their active involvement.

A lack of awareness about co-production and how to usefully involve service users.

Importance of tackling barriers with communication and honesty was demonstrated.

“[…] residents were often willing to accept […] tight financial parameters […] but communication has to be effective and residents need to feel that they are being engaged and involved in decision-making.” [48: 34]

“I think one of the problems is we are not very good at being totally honest about things […]. What we probably don’t say to people often enough is, ‘How do you want us to use this money, because that’s all we’ve got?” [48: 34]

Requirements

Requirements for successful co-production within service design were stated across the studies, including:

Offered information in accessible languages and formats explaining context, encouraging participation [47,48,49,50,51,53].

A process wherein service users and carers felt that they were engaged and truly involved in decision-making [22,51,54].

Allowed time to build relationships with each participant, involving them in creative processes, to understand the community [51,53,54,55].

Transformation

In exploring the impact of co-production on transformation, three key impacts were detailed; structure, accessibility and acceptability. In addition, two further impacts were highlighted, the health of service users and the culture of services.

Structure

The use of co-production resulted in substantial physical changes to provision and delivery of services [22,49,50,53,55], e.g. a children’s ward moved floors in a hospital building to integrate paediatric outpatients with an HIV clinic [49]. Structural changes allowed for capacity building [50,53,54,55], a top-down, bottom-up approach [50,52,53,55] and sustainability [22,52], recognising co-production as crucial in allocating resources and ensuring ownership of designed solutions.

Co-production enabled design of new interventions across all studies, e.g. a frailty screening tool [50], and a telephone reminder service [51] were implemented. One study stated the breadth of co-produced interventions [49].

“…a total of 38 concrete, practical QI interventions were suggested […]. Of these, 25 were implemented […] and 5 others were being discussed.” [49: 10]

Accessibility

Co-production increased accessibility of service provision through improved communication and pragmatic solutions. Service-to-service user communication supported accessibility [47,50,51,52,55] as service users became more informed about how and why a service met their needs, e.g. through co-produced leaflets [50], posters [51], films [47,51], online platforms [52,55], and radio [47]. Pragmatic solutions to accessibility included a mobile Hepatitis C clinic van [51].

Acceptability

Co-production enhanced acceptability of transformations by enabling specific suggestions of strategies [22,51,54,55], e.g. an incentive scheme evaluated over three months demonstrated feasibility and improved attendance rates [51]. Studies showed service delivery being performed by service user representatives [22,47,52,54,55] and each study that featured co-delivery found ownership of the co-produced transformation together with acceptance of change. One study [22] demonstrated the key benefits of the Coach Mpilo programme where men with HIV were recruited as coaches. The unique value of the coach role was trust. Peer support was utilised within the studies, alongside co-delivery [22,47,51,54], as well as people with lived experience providing training [22,52,55]. In one study a peer coordinator was employed [51].

“In supporting future parents, they offered information in their mother tongues, helped to explain the Swedish healthcare system, and participated in parental education together with staff at the local antenatal clinics.” [47: 300]

Impact on service users and services

Structure, accessibility and acceptability also affected service culture and service user health outcomes. Co-production has supported services to be more person-centred [22,50,51,52,53,54], e.g. service users and carers emphasised the importance of continence care in quality person-centred care, particularly around dignity and respect, and was prioritised as a pilot [50].

Three stand-out examples of co-production affecting people’s health outcomes were:

42% increase in cancer screening annually [47].

Increase in patients getting out of bed and dressed to reduce risks following hospital admission [50].

Reduction in death rates from malnutrition; zero over three months [49].

Wider determinants of health were affected by co-production including community-capacity building, social isolation, education and a focus on equality and diversity (e.g. studies featuring co-delivery increased employment and volunteering).

Each study outlined the impact of service culture and values within integrated care, placing service users at the forefront of responses to required transformations. Two studies acknowledged that co-production is a response to a hierarchical system [49,54].

“The [project] acknowledge[d] a paternalistic system and the potential to change this by co-creating solutions, innovations with practical outcomes that were a synergy between previously disparate groups (providers and clients).” [49: 11]

To deliver co-production, each study demonstrated the necessity to put in place a detailed focus, evaluation, reflective and iterative practice. Those featuring QI methods [49,50,52,54] emphasised the importance of testing those developing ideas that come from co-production.

“The project had to be responsive to the emergent ideas and so a range of methods to ‘evaluate’ and test these ideas were developed in collaboration with the project team and workshop participants.” [51: 218]

Each study outlined that co-production could lead to short-term challenges in delivering re-designed services. Examples include:

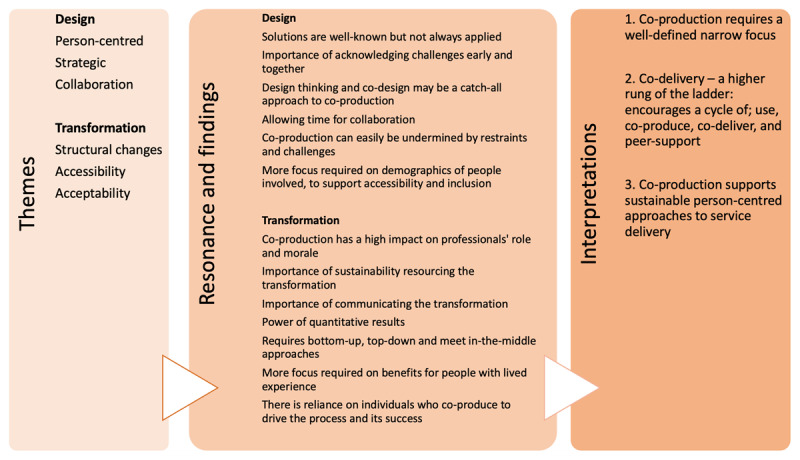

Translation and interpretation of themes

The categories ‘design’ and ‘transformation’ also emerged during translation. CAG members affirmed study findings were valid, meaningful and sensible in comparison to their experience of co-production within integrated care. While the themes drawn from the papers were well known, the examples and context provided new knowledge, enabling novel discussion. Reciprocal and refutational analysis were both useful during translation.

The CAG recognised the barriers to co-production. The study set within an integrated care system in England [48], which faced the most challenges, became a comparator to the more successful co-production examples. This comparison highlighted the limitations and successes of co-production within both design and transformation. The group’s resonance with the findings were translated into statements which encompass facilitators and barriers. This process provided three new interpretations of the data (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Translation of themes by the CAG into new interpretations.

Narrow focus

Co-production within integrated care is most constructive when matched with an explicit focus. In the case of the integrated care system, the elements of proven co-production were specific projects. Focused co-production processes require a defined scope, large or small, where roles of people involved are clear and vision and scope are shared. Delivery of focused well-defined co-production within integrated care may also require a project leader(s) who supports planning, management and definition of the process including scope, resources available, accessibility, evaluation and reporting outcomes. The CAG and co-author discussions explored the narrow focus required at the design stage, necessity of acknowledging challenges of co-production early and together, importance of co-design frameworks, and need for time to collaborate.

Co-delivery

The synthesis indicates that co-production benefits from an additional step, that of co-delivery. Building upon the depictions of the ‘ladder of co-production’ [35,45], this review offers evidence for an additional rung with ‘co-delivery’ following ‘co-production’. Co-delivery is where service users and carers who have been involved in co-production then take action to provide the service to others, supporting the operation of the transformation. Demonstrated benefits of co-delivery included ownership of the transformation, individual personal development, acceptance of co-produced changes, and public knowledge about health and care. Studies that co-delivered service transformation also showed the most authentic or ‘true’ co-production approach.

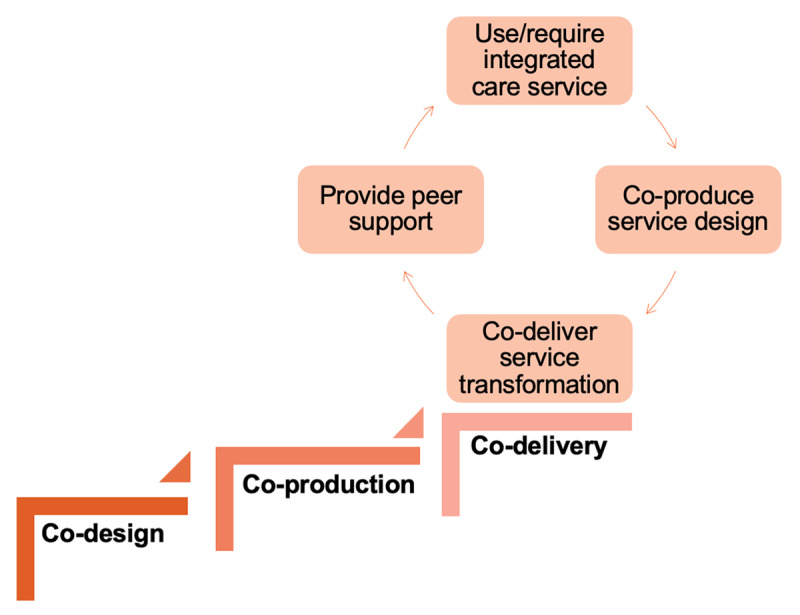

The potential of co-delivery opens up a cyclic journey for service users and carers, moving from being the recipient of an integrated care service, to co-production using their lived experience of that service and/or condition, to co-delivery, and finally, peer support (Figure 5). Peer support ensures that future service users can access services, leading to co-production opportunities. This may provide a sustainable implementation process, including co-delivered training.

Figure 5.

The co-delivery cycle.

CAG members and co-authors explored co-delivery with peer support within both design and transformation, in particular, increased acceptability of service changes. Where user involvement is extended to allow individuals to become part of delivery, the impacts are felt on professionals’ roles and morale, longer-lasting involvement benefits for people with lived experience, an increase in resources available in service delivery, and encouraging a bottom-up and top-down approach.

Sustainable person-centred services

Co-production focuses on the process of designing services so the needs of service users are met early on. Where co-production is well-led, focused and well-defined, co-delivered with people who have lived experience and that process sustains itself through peer support, the processes of co-production can be embedded into the culture of organisations, increasing the possibility that transformations will be person-centred. Where organisations expend their resources to co-produce change, and this has been successful, direct positive outcomes are shown for service users, personalised services, accessibility, and the potential for sustainability. This core concept drawn from the data resonated with CAG members and co-authors, who explored that co-production, co-delivery and peer support could transform services even during their operation by continuously making adaptations and improvements throughout the co-delivery cycle. In addition, it was recognised that sustainable and person-centred provision demanded communication loops, flexible resourcing and bridging gaps between service users’ and professionals’ lived and learned experience of integrated care.

Discussion

The relationship between the conceptual literature of integrated care and co-production does not always neatly align. While the dominant integrated care frameworks put citizen and service users’ needs at the centre of the purpose of integration, they are not traditionally included in decisions about how integration affects them and their care [2]. However, health and care systems are encouraged to incorporate users as both recipients and designers of care when planning to integratively design and transform provision [56]. The WHO’s framework for meaningful engagement of people living with non-communicable diseases, and mental health and neurological conditions sets out six key enablers for co-creating healthcare [57]. A number of their recommendations are reflected in this review including; resourcing co-production, practically addressing power imbalances, integrating lived experience into design and delivery processes, building community capacity, and embedding co-production into policy.

The aim of this systematic review has been met by our central finding from this review. We propose an extension of the existing ‘ladder of co-production’, adding a co-delivery cycle that includes peer support; enabling co-production to be embedded within integrated health and care systems.

Co-delivery is prominent in the field of co-production within public services [58,59,60], forming one of the ‘Four Co’s’ presented by Loeffler [61] and described as being more about citizens taking action in service improvement than inputting into co-design meetings. Leoffter [62] describes six types of co-delivery, three being most relevant here; co-implementation of projects; contributing to peer support groups and; co-influencing behaviour change. The cyclic co-delivery framework we propose supports and adds to the existing theories by its potential to sustainably be applied to integrated care, as evidence for co-delivery is less common in the associated health and care literature. The most common practice examples of co-delivery within integrated care are seen within mental health [34,63,64], e.g. the global Recovery College’s formal peer-taught programme [65].

Co-production uses personal strengths, resources and assets from the people involved [12,61,66]. Participatory service design within integrated care similarly demands a variety of skills and consideration of where different people’s strengths lie [16]. Co-delivery with peer support provides service users, carers and staff further opportunities to transform services alongside co-production and co-design, and provides services with access to people’s strengths, resources and assets in different and prolonged ways. Thus, a ‘co-delivery cycle’ becomes a logical extension of commonly accepted interpretations of co-production and co-design within integrated health and care systems. More research on the benefits and risks for those involved in co-delivery and peer support is required for assurance of safety, both for those delivering and for those in receipt of co-delivered services [64].

Successful co-production and co-delivery enable sustainable person-centred integrated care services. Providing care that is both integrated and person-centred is a challenge that participatory approaches may help to overcome [15,67]. However much of the evidence about service user and carer involvement and person-centred services is around the micro level, the personalisation of care, rather than co-production at the design or strategic, meso and macro levels [27,68]. The same can be said for integrated care theories, such as the House of Care approach [69] and The Burrtzorg model [70]. This review included studies at the meso and macro levels. Further research could be undertaken to understand how to embed co-production into existing frameworks at these levels, for example, the Rainbow Model of Integrated Care, which identifies six dimensions of integration aligned with micro, meso and macro levels [71].

The ambition, that co-production creates equal partnerships with people who understand first-hand the needs of the population [13,14], provides a good basis for co-production enabling person-centred integrated care. Co-produced changes, even small tweaks, have been found to improve accessibility and engagement with healthcare interventions [16]. Co-production with a narrow focus within integrated care is seen in literature and the practice of QI processes [49,50,52,54,72,73]. These well-defined methodologies have increasingly used service user involvement [26,74]. Experience-based co-design (EBCD), originally developed by Bate and Robert [75], is a published method of combining QI and co-production to ensure a focused time-bounded approach [76]. While this review initially captured several papers using variations of EBCD, with differing levels of service user and carer involvement, only one study featuring EBCD was included, as the rest did not constitute ‘co-production’ within the agreed definition.

Co-production in practice is often a creative, participatory space where various actors bring ideas for service improvement [47,66,77]. However, creativity may be restricted if the co-production process is limited to a narrow focus, as suggested in the findings. As seen across many of the studies, people involved suggested changes that were not implemented, e.g. a Hepatitis C outreach van was fully co-designed but limitations negated implementation [51]. It can be disappointing for those involved in co-production when the process is focused on the design and transformation without ongoing regard for the realities of resourcing and pace of cultural change. Simultaneously, if co-production is given a too narrow focus the features often desired in co-production (e.g. innovation, trust, equal partnerships) may be lost.

“Co-production is a slippery concept and if it is not clearly defined, there is a danger its meaning is diluted and its potential to transform services is reduced. At the same time, a definition that is too narrow can stifle creativity and decrease innovation.” [Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2013, cited in 51: 213]

Iterative and flexible design approaches, seen in included studies, allow services to be quickly accepted and meet people’s multiple care needs. This review sits in the paradigm of progression in organisational culture and values within integrated care, historically expressed as ‘nothing about us without us’ [22,78]. This ethos puts service users at the forefront of a required transformation, and thus co-production may be a challenge to a paternalistic system [49,54], system-focused frameworks and one-size-fits-all approaches to integrated care service design and transformation.

Strengths and limitations

The included studies showed strength in their deep descriptions of co-production, clear context, and recommendations for future practice. Meta-ethnography proved to be a valuable iterative process for organically exploring co-production within integrated care design and transformation. Findings and interpretations were drawn from the data using the seven phases. PPI was vital to the protocol development and understanding of the findings, which is highly recommended to future meta-ethnographers. The CAG members’ resonance with the findings provided a rich contribution, enabling new interpretations of the data to be understood at an operational level. The strength of methods resulted in a novel cyclic co-delivery framework for application within integrated care.

The main limitation was gaps in data including; numbers of people within different groups, demographics, evaluation techniques and equality across and between groups (Table 4). It was therefore difficult to compare the models of co-production. CAG members emphasised this lack of data proved challenging for assuring equity across co-production processes, limiting knowledge of accessibility and inclusion of diverse people or communities and learning for future best-practice. They also noted that studies displaying quantitative data could more easily show successes and tangible outcomes than those not providing statistical information via measuring impacts or undertaking an evaluation.

There were limitations to the methods, most notably how depictions of the ‘ladder of co-production’ were used to measure the extent of co-production. As multiple studies scored the same, further work may be necessary to capture nuances of co-production processes. Similarly, heterogeneity of studies in practice and provision limited the application of CAG-developed concepts and definitions relating to ‘co-production’ and ‘integrated care’. This heterogeneity made describing each model of co-production challenging for authors and CAG members. The models were revealed during data extraction therefore not previously defined for inclusion in the search criteria. Despite this, varying concept definitions present in the papers (Table 5), along with use of the scoring process, enabled authors and CAG members to draw conclusions from the data.

Conclusion

This paper highlights three core findings; co-production requires a process with a narrow focus, co-delivery with peer support facilitates service user involvement to be embedded at a higher level on the ‘ladder of co-production’, and implementing these enables transformations to be person-centred. Through novel use of meta-ethnography and PPI, this review proposes a cyclic co-delivery framework. This innovative and operational development has potential to enable better-sustained person-centred integrated care services.

Further research is recommended to explore how co-production within integrated care, and the cyclic co-delivery framework, can deliver successful design and transformation resulting in person-centred care. In particular, primary data collection and evaluation of co-production methods within integrated care service design and subsequent service transformation need to be prioritised.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Appendix A to E.

Tables 3 to 5.

Acknowledgements

The CAG members Lucy Ainsley, Cath Allum, Annetta Bradshaw, Tracy Brooke, Tanya Florence, and Richard Iles.

Funding Statement

This paper was completed as part of a doctoral research programme funded by Ipswich and East Suffolk Clinical Commissioning Group, sponsored by The Integrated Care Academy, University of Suffolk.

Reviewers

Axel Kaehne, Professor Health Services Research, Medical School, Edge Hill University, UK.

Susan Usher, Université de Sherbrooke, Canada.

One anonymous reviewer.

Funding Information

This paper was completed as part of a doctoral research programme funded by Ipswich and East Suffolk Clinical Commissioning Group, sponsored by The Integrated Care Academy, University of Suffolk.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Donaldson L. Exploring patient participation in reducing health-care-related safety risks. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation; 2013. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326442/9789289002943-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glimmerveen L, Nies H, Ybema S. Citizens as active participants in integrated care: Challenging the field’s dominant paradigms. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2019; 19(1): 6. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.4202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Commission. Co-production – enhancing the role of citizens in governance and service delivery. European Social Fund Plus; 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/european-social-fund-plus/en/publications/co-production-enhancing-role-citizens-governance-and-service-delivery.

- 4.World Health Organisation. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. 2015; WHO/HIS/SDS/2015.6. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/155002/WHO_HIS_SDS_2015.6_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 5.Department of Health. Care and support statutory guidance. Issued under the Care Act 2014; 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/315993/Care-Act-Guidance.pdf.

- 6.NHS England. Working in Partnership with People and Communities; 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/B1762-guidance-on-working-in-partnership-with-people-and-communities-2.pdf.

- 7.Armitage GD, Suter E, Oelke ND, Adair CE. Health systems integration: State of the evidence. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2009; 9: e82. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright JSF, Turner S. Integrated care and the ‘agentification’ of the English National Health Service. Social Policy & Administration. 2021; 55(1): 173–90. DOI: 10.1111/spol.12630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ham C, Curry N. Integrated care: What is it? Does it work? What does it mean for the NHS? The King’s Fund; 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/integrated-care-summary-chris-ham-sep11.pdf.

- 10.Briggs ADM, Göpfert A, Thorlby R, Allwood D, Alderwick H. Integrated health and care systems in England: Can they help prevent disease? Integrated Healthcare Journal. 2020; 2(1): e000013. DOI: 10.1136/ihj-2019-000013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raney L, Lasky G, Scott C. Integrated care: A guide for effective implementation. New York: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahn ES. No more throw-away people: The co-production imperative. Washington, DC, Charlbury: Essential; Jon Carpenter; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Realpe AW, Wallace L. What is co-production? 2010. https://qi.elft.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/what_is_co-production.pdf.

- 14.Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, Seid M, Armstrong G, Opipari-Arrigan L, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2016; 25(7): 509. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall K, Bamber H. Using co-production in the implementation of community integrated care: A scoping review. Primary Health Care. 2022; 32(4): 36–42. DOI: 10.7748/phc.2022.e1753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke D, Jones F, Harris R, Robert G. What outcomes are associated with developing and implementing co-produced interventions in acute healthcare settings? A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(7): e014650. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conquer S, Bacon L. The value of co-production within health and social care: A literature review. Healthwatch Suffolk; 2021. https://healthwatchsuffolk.co.uk/co-production/literaturereview/.

- 18.Kaehne A, Beacham A, Feather J. Co-production in integrated health and social care programmes: A pragmatic model. Journal of Integrated Care. 2018; 26(1): 87–96. DOI: 10.1108/JICA-11-2017-0044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palumbo R. Contextualizing co-production of health care: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2016; 29(1): 72–90. DOI: 10.1108/IJPSM-07-2015-0125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith E, Ross FM. Service user involvement and integrated care pathways. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2007; 20(3): 195–214. DOI: 10.1108/09526860710743345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe D, Ryan R, Schonfeld L, Merner B, Walsh L, Graham-Wisener L, et al. Effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership on health services planning, delivery and evaluation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021; 9. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013373.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruns C. Using human-centered design to develop a program to engage South African men living with HIV in care and treatment. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2021; 9(Supplement 2): S234. DOI: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox C, Smith A, Traynor P, Harrison J. Co-creation and co-production in the United Kingdom – A rapid evidence assessment. Manchester Metropolitan University; 2018. https://mmuperu.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Co-Creation_and_Co-Production_in_the_United_Kingdom_-_A_Rapid_Evidence_Assessment_-_March_2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Hughes J, Macfarlane F, Butler C, Pawson R. How do you modernize a health service? A realist evaluation of whole-scale transformation in London. The Milbank Quarterly. 2009; 87(2): 391–416. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00562.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bovaird T. Efficiency in third sector partnerships for delivering local government services: The role of economies of scale, scope and learning. Public Management Review. 2014; 16(8): 1067–90. DOI: 10.1080/14719037.2014.930508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergerum C, Thor J, Josefsson K, Wolmesjö M. How might patient involvement in healthcare quality improvement efforts work—A realist literature review. Health Expectations. 2019; 22(5): 952–64. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vennik FD, van de Bovenkamp HM, Putters K, Grit KJ. Co-production in healthcare: Rhetoric and practice. International Review of Administrative Sciences. 2015; 82(1): 150–68. DOI: 10.1177/0020852315570553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holland-Hart DM, Addis SM, Edwards A, Kenkre JE, Wood F. Coproduction and health: Public and clinicians’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators. Health Expectations. 2019; 22(1): 93–101. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gheduzzi E, Masella C, Morelli N, Graffigna G. How to prevent and avoid barriers in co-production with family carers living in rural and remote area: An Italian case study. Research Involvement and Engagement. 2021; 7(1): 16. DOI: 10.1186/s40900-021-00259-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners. 1969; 35(4): 216–24. DOI: 10.1080/01944366908977225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jo S, Nabatchi T. Getting back to basics: Advancing the study and practice of coproduction. International Journal of Public Administration. 2016; 39(13): 1101–8. DOI: 10.1080/01900692.2016.1177840 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whaley J, Domenico D, Alltimes J. Shifting the balance of power. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities. 2019; 13(1): 3–14. DOI: 10.1108/AMHID-03-2018-0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd H, McKernon S, Mullin B, Old A. Improving healthcare through the use of co-design. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2012; 125(1357): 76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pardi J, Willis M. How young adults in London experience the Clubhouse Model of mental health recovery: A thematic analysis. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health. 2018; 5(2): 169–82. DOI: 10.1007/s40737-018-0124-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skills For Care. Co-production in mental health; 2018. https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/resources/documents/Developing-your-workforce/Care-topics/Learning-disability-and-mental-health/Co-production-in-mental-health.pdf.

- 36.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies: SAGE Publications; 1988. DOI: 10.4135/9781412985000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nye E, Melendez-Torres GJ, Bonell C. Origins, methods and advances in qualitative meta-synthesis. Review of Education. 2016; 4(1): 57–79. DOI: 10.1002/rev3.3065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.France EF, Ring N, Noyes J, Maxwell M, Jepson R, Duncan E, et al. Protocol-developing meta-ethnography reporting guidelines (eMERGe). BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2015; 15(1): 103. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-015-0068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, Uny I, Duncan EAS, Jepson RG, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. Review of Education. 2019; 7(2): 430–51. DOI: 10.1002/rev3.3147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth A. Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech. 2006; 24(3): 355–68. DOI: 10.1108/07378830610692127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covidence. Covidence systematic review software. Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; 2024. https://www.covidence.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sattar R, Lawton R, Panagioti M, Johnson J. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research. 2021; 21(1): 50. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of a Qualitative research; 2018. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf.

- 44.Gough D. Weight of Evidence: A framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education. 2007; 22(2): 213–28. DOI: 10.1080/02671520701296189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Think Local Act Personal. Ladder of co-production; 2021. https://www.thinklocalactpersonal.org.uk/Latest/Co-production-The-ladder-of-co-production/.

- 46.NHS England and NHS Improvement. Building strong integrated care systems everywhere ICS implementation guidance on working with people and communities; 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/B0661-ics-working-with-people-and-communities.pdf.

- 47.Eriksson EM. Representative co-production: Broadening the scope of the public service logic. Public Management Review. 2019; 21(2): 291–314. DOI: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1487575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lalani M, Fernandes J, Marshall M. Locality based approaches to integrated care in Tower Hamlets Final report; 2019. https://www.towerhamletstogether.com/resource-library/34/download.

- 49.Van Deventer C, Robert G, Wright A. Improving childhood nutrition and wellness in South Africa: Involving mothers/caregivers of malnourished or HIV positive children and health care workers as co-designers to enhance a local quality improvement intervention. BMC Health Services Research. 2016; 16(1): 358. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-016-1574-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Donnell D, Ní Shé É, McCarthy M, Thornton S, Doran T, Smith F, et al. Enabling public, patient and practitioner involvement in co-designing frailty pathways in the acute care setting. BMC Health Services Research. 2019; 19(1): 797. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-019-4626-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolstenholme D, Poll R, Tod A. Innovating access to the nurse-led hepatitis C clinic using co-production. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2020; 25(3): 211–24. DOI: 10.1177/1744987120914353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkadi A, Dahlberg A, Leander K, Johansson M, Zahlander J, Fäldt A, et al. An integrated care strategy for pre-schoolers with suspected developmental disorders: The Optimus co-design project that has made it to regular care. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2021; 21(2): 3. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.5494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Baral KP, Bhatta N, Mehta S, Harris MF. Using a co-design process to develop an integrated model of care for delivering self-management intervention to multi-morbid COPD people in rural Nepal. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2021; 19(1): 17. DOI: 10.1186/s12961-020-00664-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flora L, Lebel P, Dumez V, Bell C, Lamoureux J, Saint-Laurent D. L’expérimentation du Programme partenaires de soins en psychiatrie: Le modèle de Montréal. Santé mentale au Québec. 2015; 40(1): 101–17. [in French]. DOI: 10.7202/1032385ar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kamvura TT, Turner J, Chiriseri E, Dambi J, Verhey R, Chibanda D. Using a theory of change to develop an integrated intervention for depression, diabetes and hypertension in Zimbabwe: Lessons from the Friendship Bench project. BMC Health Services Research. 2021; 21(1): 928. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-021-06957-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doble E, Barone M. Co-creating healthcare. BMJ. 2023; 382: 1820. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.p1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organisation. WHO Framework for meaningful engagement of people living with non-communicable diseases, and mental health and neurological conditions; 2023. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/367340/9789240073074-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 58.Parks RB, Baker PC, Kiser L, Oakerson R, Ostrom E, Ostrom V, et al. Consumers as co-producers of public services: Some economic and institutional considerations. Policy Studies Journal. 1981; 9(7): 1001–11. DOI: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.1981.tb01208.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alford J, O’Flynn J. Rethinking public service delivery: managing with external providers. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Loeffler E, Bovaird AG. The Palgrave handbook of co-production of public services and outcomes. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2021. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-53705-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loeffler E, Bovaird T. Co-commissioning of public services and outcomes in the UK: Bringing co-production into the strategic commissioning cycle. Public Money & Management. 2019; 39(4): 241–52. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2019.1592905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loeffler E. Co-delivering public services and public outcomes. In: Loeffler E, Bovaird T (eds.), The Palgrave handbook of co-production of public services and outcomes. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2021. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-53705-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slay J, Stephens L. Co-production in mental health: A literature review. London: New Economics Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewis HK, Foye U. From prevention to peer support: A systematic review exploring the involvement of lived-experience in eating disorder interventions. Mental Health Review Journal. 2022; 27(1): 1–17. DOI: 10.1108/MHRJ-04-2021-0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muir-Cochrane E, Lawn S, Coveney J, Zabeen S, Kortman B, Oster C. Recovery College as a transition space in the journey towards recovery: An Australian qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2019; 21(4): 523–30. DOI: 10.1111/nhs.12637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyle D, Harris M. The challenge of co-production; 2009. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/the_challenge_of_co-production.pdf.

- 67.Henderson L, Bain H, Allan E, Kennedy C. Integrated health and social care in the community: A critical integrative review of the experiences and well-being needs of service users and their families. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2021; 29(4): 1145–68. DOI: 10.1111/hsc.13179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Persson S, Andersson AC, Kvarnefors A, Thor J, Andersson Gäre B. Quality as strategy, the evolution of co-production in the Region Jönköping health system, Sweden: A descriptive qualitative study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2021; 33(Supplement_2): ii15–ii22. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzab060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coulter A, Roberts S, Dixon A. Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions: Building the House of Care. The King’s Fund; 2013. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/delivering-better-services-for-people-with-long-term-conditions.pdf.

- 70.Monsen KA, De Blok J. Buurtzorg: Nurse-led community care. Creative Nursing. 2013; 19(3): 122–7. DOI: 10.1891/1078-4535.19.3.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valentijn P. Rainbow of chaos: A study into the theory and practice of integrated primary care. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2016; 16: 1–4. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suutari AM, Areskoug-Josefsson K, Kjellström S, Nordin AMM, Thor J. Promoting a sense of security in everyday life—A case study of patients and professionals moving towards co-production in an atrial fibrillation “learning café”. Health Expectations. 2019; 22(6): 1240–50. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kilander H, Weinryb M, Vikström M, Petersson K, Larsson EC. Developing contraceptive services for immigrant women postpartum – a case study of a quality improvement collaborative in Sweden. BMC Health Services Research. 2022; 22(1): 556. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-022-07965-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Armstrong N, Herbert G, Aveling EL, Dixon-Woods M, Martin G. Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expectations. 2013; 16(3): e36–e47. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paul B, Glenn R. Experience-based design: From redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2006; 15(5): 307. DOI: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomas N. Service user involvement in healthcare improvement. In: Baillie L, Maxwell E (eds.), Improving healthcare: A handbook for practitioners. London: Taylor & Francis; 2017: 53–63. DOI: 10.1201/9781315151823-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bamber H. Managers’ and clinical leads’ perspectives of a co-production model for community mental health service improvement in the NHS: A case study. DProf Thesis; 2020. https://salford-repository.worktribe.com/output/1354203/managers-and-clinical-leads-perspectives-of-a-co-production-model-for-community-mental-health-service-improvement-in-the-nhs-a-case-study. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.ICIC2070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Charlton J. Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1998. DOI: 10.1525/9780520925441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A to E.

Tables 3 to 5.