Abstract

The purpose of the present research is to test the level of agreement between targets and observers both at any given moment and as the targets’ current behavior (assessed as personality states) change across moments. Ninety-seven target participants participated in 22 different activities across 20 one-hour long sessions in a laboratory setting while reporting their current behavior, and their behavior was evaluated by 183 observers (total of 3493 target self-reports, 2973 of which had a corresponding observer report from at least one observer). Target-observer and observer-observer agreement was significant for all personality states (and was substantial for Extraversion, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience), and was observed in different situations, across all situations, and after accounting for normative agreement. The findings from this study—the first to examine within-person agreement on in-person behavioral states—provide evidence that people can accurately report their current behavior, that people agree on changes in behaviors across situations, and by extension that intensive assessment methodologies (such as experience sampling methodology) have validity as assessments of momentary behavior.

Keywords: behavior, personality states, agreement, situations, personality, experience sampling methodology

The purpose of the present research is to test the level of agreement between targets and observers on targets’ current behavior (assessed as personality states) at any given moment and as the target’s behaviors change across different situations. It is important to pursue this purpose for at least four reasons. First, behavior— being visible to observers (Furr, 2009a)—is a basic element of the social world. Specifically, agreement about behavior reveals both the degree of self-awareness and the degree to which perceptions of social reality are shared. Behavior is the primary means of impact on other people, and lack of awareness about how people are acting would make effective interaction nearly impossible. Alienation from awareness of one’s own behavior would create great social difficulty and harm one’s reputation (Vazire & Wilson, 2012).

Second, determining the level of agreement about behavior and changes in behavior is vital to dynamic theories of personalities (e.g., Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2015; Fournier et al., 2022; Jayawickreme et al., 2021a, b; Quintus et al., 2020; Rauthmann et al., 2015; Tett & Guterman, 2000; Wrzus et al., 2021). For such approaches to be viably tested, both self- and observer-reports of momentary behavior and changes in those reports must be valid. There is additionally strong interest in the study of behavior in personality psychology more generally (Baumeister et al., 2007; Funder, 2012; Uziel & Baumeister, 2009). This means that assessments of behavior need to be evaluated as viable dependent variables. This applies especially to the state conception of behavior (Baumert et al., 2017; Bleidorn, 2009; Bleidorn et al., 2020; Breil et al., 2019; Geukes & Back, 2017; Fleeson, 2001; Jayawickreme et al., 2019) which typically uses subjective ratings rather than behavioral categories.

Third, agreement about behavior is a core feature of person perception. Trait perception, for it to be realistic, must be based on the perception of behaviors first, followed by inferences to traits (Funder, 2001; Uleman & Saribay, 2012). Were this not to happen, trait perceptions would be based on factors other than how the person behaves. Thus, the primary step in person perception is the accurate perception of behaviors (Eysenck, 1970), and realistic theories of person perception require substantial agreement in the perception of behaviors. If there is already slippage in the perception of behaviors, this slippage will likely be magnified when carried over to the perception of traits, resulting in poor accuracy. Surprisingly, little direct information concerning the agreement about behavior exists in the current literature (Furr, 2009a; Mõttus et al., 2020). Given that agreement about behavior should be the building block of agreement about traits, if the agreement isn’t high for behaviors, the possibility for meaningful agreement on traits is substantially undermined.

Fourth, in addition to the key theoretical implications noted above, this question is also relevant to assessing intensive assessment strategies such as experience-sampling methodology (ESM), given that the credibility of such studies relies on the dependability of self-reports of on-going behavior (e.g., Sun & Vazire, 2019). However, given that are ESM reports rely on subjective judgments, there is reasonable doubt that they accurately represent actual behavior (Horstmann & Ziegler, 2020). Uncertainty over the status of ESM as a valid measure of behavior casts doubt on entire literatures in the psychological and behavioral sciences that rely heavily on this method.

We therefore present results from an innovative study that specifically examines levels of agreement about personality states and changes in personality states across situations. Specifically, we examine a) the degree of target-observer and observer-observer agreement on Big Five personality states in different situations, b) the degree of target-observer and observer-observer agreement on changes in personality states across situations, c) the degree of target-observer and observer-observer agreement after accounting for normative agreement, and d) individual differences in the amount of observed target-observer and observer-observer agreement. In doing so, this study evaluates the validity of self-reported behavioral states as an indicator of behavior (Fleeson, 2001).

What is the Level of Agreement About Targets’ Traits?

One would generally expect high levels of agreement regarding traits, given that traits tend to be stable within a person, manifest in daily behavior, and are consequential to social life (Anglim et al., 2020; Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Schimmack & Kim, 2020; Roberts et al., 2007; Soto, 2019). It is therefore not surprising that both target-observer and observer-observer agreement on targets’ broad trait levels has been observed to be generally high (Albright et al., 1988; Back et al., 2008; Colvin & Funder, 1991; Funder et al., 1995; Letzring et al., 2006; Gosling et al., 2002; 2007; Helzer et al., 2014; Holleran & Mehl, 2008; Marcus et al., 2006; Mottus et al., 0214; Vazire & Gosling, 2004; Watson, 1989; Watson et al., 2000; see Kim et al., 2019 for meta-analytic evidence for target-observer agreement). Trait content has been found to make a difference to the level of agreement. Meta-analyses have found that target-observer agreement about Extraversion is consistently the highest, while agreement about Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, Intellect and Agreeableness was also found to be strong, but smaller (Connolly et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2019).

Preliminary evidence suggests that differences in trait agreement may be due to several factors, including degree of interpersonal closeness, type of relationship to target, and trait content (Connelly & Ones, 2010; Kim et al., 2019; Vazire, 2010). Furthermore, in order for targets and observers to agree on trait-relevant behavior, it must be visible (Funder & Colvin, 1988; Vazire, 2010), noticed by the observer (Funder, 1995), interpreted in the same way by targets and observers (Kenney, 1994), and finally reported accurately (Paunonen, 1989). Compounding these barriers to agreement, targets and observers frequently have different perspectives on the behavior (Vazire, 2010). As a result, targets and observers exhibit greater consensus for more observable/behavioral traits (e.g., extraversion) rather than less observable/internal traits (e.g., neuroticism; Funder & Doborth, 1987; John & Robbins, 1993; Vazire, 2010).

Agreement about traits may be based on factors other than behavior, such as stereotypes, physical characteristics, halo effects, and projection. For example, trait agreement may be higher because of differences in body shape (Hu et al., 2018), because they reflect favorable ratings of desirable group members (see Crawford & Brant, 2019 for a broad discussion); and because of shared myths about the implications of various behaviors (e.g., Blackie et al., 2015). It is not known how much high levels of agreement about traits are attributable to those factors. Indeed, if agreement about behavior is low, it suggests that agreement about traits may be artificially inflated by such superficial features. These challenges make it important to examine the extent to which individual differences in the amount of target-observer and observer-observer agreement on trait-relevant behavior are observed.

The Importance of Examining Within-Person Agreement about Behavior

Because of the focus on agreement about traits, personality research on agreement has naturally employed mostly between-person agreement (Borkenau & Liebler, 1992; Carlson et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2013; Human & Biesanz, 2011). Between-person agreement relies on differences between targets in their levels of traits, and tests whether ratings of target traits are sensitive enough to track those differences. However, few studies have focused on within-person agreement in behavior. Within-person agreement refers to how much targets and observers agree on how the target is behaving differently than how the same target behaved on other occasions. In other words, within-person agreement indexes the extent to which observers observe current states with enough sensitivity to track changes in a target’s behavior from moment to moment in a way that corresponds to targets’ own perceptions of change (Bernieri et al., 1994). Within-person agreement is a critical test of whether observers and targets can agree about dynamic shifts in behavior, as high levels of within-person agreement would indicate that observers are sensitive to variations in targets’ behavior as they engage and respond to different contexts (Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2021; Lievens et al., 2006; Tett & Guterman, 2000).

Prior research has demonstrated that such within-person shifts in behavior are meaningful; for example, changes in extraversion may be the result of both demands afforded by the situation (Fleeson, 2007) and goals that may be facilitated by manifesting extraversion (McCabe & Fleeson, 2012). Since process models consider within-person variation over time (Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2021; Wrzus & Roberts, 2017; Wrzus et al., 2021), it is important to test whether assessments of these changes over time are valid. Additionally, examining agreement at the within-person level can help get around stereotype effects on person perception (Blackman & Funder, 1998; Fiske et al., 2002; Higgins, 1989).

In examining within-person agreement, it is also important to account for normative beliefs about a situation’s impact on behavior. For example, multiple informants may rate a target’s level of extraversion in two distinct situations – while planning a party and while studying. In this scenario, observers could potentially assume that targets were more extraverted when planning the party and thus rate them so, without observing the targets’ actual extraversion levels. Here, the observers may have high agreement on cross situational changes in the target’s extraversion, even though neither observer had paid attention to the target’s behavior. Thus, to be sure that within-person agreement reflects observations rather than assumptions, it is important to examine whether agreement is still present after removing the effects of such normative patterns of cross-situational changes in states.

Examining Agreement Across Multiple Situations

Examining within-person agreement requires assessing behavioral states across many different situations. Ideally, those situations are spaced apart in time and reflect everyday types of situations. Thus, this study included a wide range of different situations, selected to reflect the kinds of situations the targets would normally encounter, and spaced out across multiple months.

In addition, this design allows investigating the effects of situations on agreement. While situations— a set of circumstances with distinctive and psychologically active characteristics and affordances (Fleeson, 2007)—affect behavior (Lewin, 1936; Ross & Nisbett, 1991), situations may also affect agreement about the behavior. For example, some situations may facilitate certain types of behavior over others (e.g., extraverted vs. introverted behavior at a party; conscientious vs. extraverted behavior at a library), leading raters to perceive behavior in that context as relevant to the affordances of the situation. Understanding behavior in a given situation involves also understanding its purpose, which is tied to the features of the situation (Fleeson, 2007; Horstmann & Ziegler, 2020). It is therefore important to examine agreement about behavior in multiple situations.

Such an approach has several advantages. First, it allows for multiple tests of agreement, meaning that the findings are generalizable across situations, as opposed to being specific to one situation. Second, it is possible to examine whether situations matter for the level of agreement (Rauthmann & Sherman, 2017). Based on prior research on trait-perceptions, some situations may lead to greater agreement than others. For example, Borkenau and colleagues (2004) found that self-observer agreement for Openness to Experience varied across a set of situations, such that agreement was highest for an activity of describing multiple uses for a brick and lowest for singing a song. These initial findings provide preliminary support for diagnosticity, that is, the idea that certain traits are expressed more in certain situations (Funder, 1995). There are a number of reasons for why specific traits are expressed more in certain situations; for example, specific situations may afford the achievement of specific goals, which require specific state manifestations (McCabe & Fleeson, 2012). The design of the present study allows us to evaluate whether agreement depends on the situation in which the behavior is taking place.

Examining Within-Person Agreement Utilizing the State Approach to Measuring Behavior

The present study also investigates the validity of the state assessment of behavior by considering whether observers agree on targets’ personality states. Conceptualizing behavior in terms of states (Fleeson, 2001; Steyer et al., 1992) affords the opportunity to assess both the trait content of specific behaviors and the degree to which the person is expressing that trait in their behavior at each moment (rather than examining behavior as discreate events). The most straightforward way of assessing this is through utilizing continuous adjectives that are broader than reporting specific categories of behavior. State assessments may be done in other ways, but one challenge is that these approaches may not capture the core features of the trait content. The idea behind this approach is to focus on the key trait-relevant dimensions of the behavior, rather than its physical actions or superficial appearance (Fleeson, 2007).

Using states is advantageous in at least three ways. First, states emphasize the psychological meaning behind behavior. For example, the discrete behavior of slapping someone on the back may carry the psychological meaning of either being warm or aggressive, depending on the context (Fleeson, 2007). Second, states are advantageous because they transfer the content of the trait to the state, so traits and states are directly commensurate. Third, states have been proven useful for investigating dynamic approaches to personality. They have been a key component of the assessment of process models of personality traits (Fleeson & Law, 2015; Quintus et al., 2020), they are manifested in the service of achieving goals in daily life (McCabe & Fleeson, 2012), and changes in state manifestations over time may lead to enduring changes in personality and well-being (e.g., Bleidorn et al., 2020; Fleeson, 2001; 2007; Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2015; Fleeson & Leicht, 2006; Fleeson, Malanos, & Achille, 2002).

Examining the Validity of Experience Sampling Methodology

Finally, the present study tests the validity of experience sampling methodology (ESM) for measuring behavior. ESM has been utilized to answer important questions in psychology, including the existence of, consistency of, and processes underlying traits (Fleeson, 2001; Fleeson, 2007; Fleeson & Noftle, 2008a; Fleeson & Noftle, 2008b; Noftle & Fleeson, 2010; Horstmann et al., 2020; McCabe & Fleeson, 2016; Heller et al., 2007; Noftle & Fleeson, 2010). ESM has high ecological validity because it allows individuals to answer questions while immersed in different real-life situations. It also allows for better examination of within-person fluctuations in personality states (Sherman et al., 2015).

ESM however also has a number of drawbacks (Scollon et al., 2003). Chief among them is the worry that ESM does not sufficiently attenuate weaknesses of self-report, such as socially desirable responding or self-deception (Conner et al., 2007; Cutler et al., 1996). Because states are not concrete, rely on subjective judgments, and are reported by the actors themselves, there is reasonable doubt that they accurately represent actual behavior. Given the critical importance of ESM for the testing of current theories of personality dynamics (Horstmann & Ziegler, 2020; Jayawickreme et al., 2021a), it is important to provide evidence that individuals can accurately report their on-going behavior.

Existing Research on Agreement about Behavior

To our knowledge, past research has not examined both target-observer and observer-observer agreement of directly observed trait-relevant state manifestations as it changes across different situations.1 Ozer and Buss (1991) used spouses as observers over a 3-month period and compared their reports of behaviors to target participants. In another study, Kolar and colleagues (1996) had unacquainted observers view videotapes and make ratings on the California Q-sort (e.g., initiates humor, behaves in a considerate manner) which were compared with self-ratings on the Q-sort.

Gosling and colleagues (1998) conducted a study where observers viewed videotapes of a group discussion and rated behaviors that were specific to the task the participants engaged in (e.g., issued orders that got the group organized, outlined a set of criteria for determining how to allocate money). However, they coded behaviors as discrete categorical events (e.g., “pointed out the distinction between a merit bonus and a salary increase”) rather than as dimensional attributes (e.g., “precise”). Dichotomous ratings (even as counts) are generally less reliable than dimensional ratings, require very specific events to occur, and are often multi-barreled, providing multiple opportunities for disagreement. Similarly, Vazire and Mehl (2008) observed that both self- and informant reports of discrete behaviors predicted objective ratings of audio recordings of enacted behavior.

Sun and Vazire (2019) recently examined the relationship between state assessments of four Big Five traits and objective ratings of audio recordings of enacted behavior. For three of the four traits, self-ratings of states predicted indirect ratings of those states based on audio recordings. A particular strength of this important study was the naturalistic assessment of behaviors and independent qualities of the ratings based on audio recordings; however, coders of the audio recordings did not have visual information on targets’ behaviors. The innovative design of the current study allows us to examine both target-observer and observer-observer agreement on directly observed (i.e., both aurally and visually accessible) behaviors across multiple situations.

The Present Research

We examined the level of agreement between targets and observers on targets’ behavior across a series of 22 laboratory-based situations. Participants in this study came to the lab on 20 different occasions across a period of 10 to 20 weeks, lasting an hour each. All participants experienced the same situations in the same order. This innovative research design affords the opportunity to focus our analysis of agreement in several distinct ways. Based on the considerations outlined above, we examined the following research questions related to (target-observer and observer-observer) agreement about behavior:

1) What is the degree of agreement on Big Five personality states in different situations?

2) What is the degree of agreement on changes in personality states across all situations?

3) What is the degree of agreement after accounting for normative agreement?

4) Are there individual differences in the amount of observed agreement?

Method

Participants

This research is part of the Integrating Processes and Structure into Personality (IPSP) study. Data from this study have been reported in prior publications (e.g., Fleeson & Law, 2015; Fleeson & Wilt, 2010; Noftle & Fleeson, 2010; Noftle & Gust, 2019; Wilt et al., 2012). However, the analyses related to the present research question were not included in those publications. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Wake Forest University. The procedure below is adapted from Fleeson and Law (2015, p. 1093–1094). We note that the analyses reported in this paper were not preregistered2.

Participants came into the lab on up to 20 different occasions, once or twice per week for 10 to 20 weeks. Targets (N = 97) in this study interacted in groups of 2 to 4, while observers (total N = 183; N = 97 primary observers and N = 86 secondary observers) viewed the targets from behind one-way mirrors. Twenty two of the 321 participants who originally committed to the study dropped out prior to the study, while seven targets attended six or fewer sessions and 12 observers attended two or fewer sessions. These participants were not included in any of the following analyses.

The study was conducted in two waves of enrollment and participation across the academic year, with one session per week for 20 weeks (N = 62 targets, 118 observers); and in the spring semester of the same academic year with two sessions per week for 10 weeks (N = 35 targets, 65 observers). Individuals were compensated either $6 (wave one) or $8 (wave two) per session, plus attendance-based bonuses. The waves were combined as they followed the same procedure and contained samples with similar demographic backgrounds.

Procedure

Participants first attended an information meeting describing the study. They were told that the study’s goal was to investigate how people act and assess their behavior in a variety of activities. They were further informed that the study was being conducted in the laboratory to make sure that participants all have the same situations and have their behavior rated by attending observers. They then provided consent and completed a short questionnaire. Only measures relevant to this paper will be described.

Participants took part in up to 20 sessions. Groups of between two and four targets participated together in each session for 50 minutes. Sessions began with targets reading instructions and then participating in the instructed situation. Typically, targets sat at the sides of a small, four-sided table in a medium-sized room, with one-way mirrors lining two of the walls. Four observers were behind each mirror; this allowed observers watching the same target to be behind different mirrors. Observers wore headphones to listen into sound from the target room and were instructed to focus on their assigned target at all times and not to talk or make other sounds. Each observer rated his or her assigned target after 20–25 minutes and at the end of each session. Concurrent observation was used to make the observer’s task as similar as possible to the target’s task.

Laboratory situations were chosen on the basis of the following criteria: (i) they should engage individuals in the activity; (ii) they were reasonably representative of the situations participants encounter in daily life; (iii) they showed substantial between-subject variability in previous research; (iv) they were unstructured and unconstrained enough to allow a wide range of behaviors from the individuals in the situation (so as not to inflate or deflate estimates of variability or accuracy); and (v) they provided a variety of settings and tasks so as to provide opportunity for each level of each of the Big 5 states. The following situations occurred in the following order (situations with two sub-components are labeled A and B): (1) bingo, (2) discuss medical ethics dilemmas, (3) tell an embarrassing story, (4) plan a safe sex campaign, (5) twister, (6A), sculpt personality traits, (6B) analyze a painting, (7) role play a compensation committee, (8) play a board game, (9) interpret drawings, (10) study, (11) review trait words, and paint, (12A) solve the parking problem on campus, (12B) plan a party, (13) no instructions, (14) plan and present a speech and debate, (15) no instruction 2, (16) play charades, (17) collaborate on one participant’s study project, (18) word review and paint 2 (19A) discuss sweatshops, (19B) complete questionnaires (20) play a board game 2. Observers did not rate targets after situation 19B. Because of scheduling issues or errors, on eight occasions participants completed a backup activity.

Two observers were assigned to a particular target for the duration of the study. Our rationale for this choice was to avoid inflating within-target variance due to different observers, which increased the power of the study and ensured that within-subject variation was due to changes in the same person, not due to different raters3. Observers were mostly assigned to targets at random, taking into account schedule availability. Halfway through the study, one of the two observers for each target was reassigned to a different task, based primarily on compatibility of schedules. The primary observer was the one who observed the target the most times, and analyses use the primary observers’ data unless otherwise stated. Two observers started as targets but were switched very early to be observers for balancing purposes (their target data is excluded).

Targets were rotated through the groups, in order to have targets interact with different people each session. The average target interacted with 27–28 different people over of the course of the 20 sessions (because of occasional repeats, the average target had 45 interaction partners). We attempted to have the interaction partners be entirely new each time, but scheduling restrictions meant that the average target had seen 6.9 of the partners one previous time, 2.6 partners two previous times each, 1 partner three previous times, .4 partner four previous times, and .2 partner five previous times.

Attendance was high; observers attended 85% of the assigned sessions and targets attending 90% of the assigned sessions, producing 3492 self-reports and 4838 independent observer reports of those same behaviors. Reports were discarded if an experimenter noted a problematic occurrence, such as observers’ headphones not working, a participant being late, observers overhearing targets discuss their self-reports, or a participant responding the same number to all adjectives. In the end, 183 target or observer reports were removed, resulting in 3493 target self-reports, and 2973 self-reports that had a corresponding observer report from at least one observer (86%).

Materials

Targets and observers used the same standard Big-Five adjective-based scales (Goldberg, 1992) to rate targets. Four bipolar adjective scales assessed each Big-Five factor: extraversion (unenergetic-energetic, bold-timid, talkative-silent, and unassertive-assertive), agreeableness (warm-cold, rude-polite, stingy-generous, distrustful-trustful), conscientiousness (careless-thorough, hardworking-lazy, serious-frivolous, inefficient-efficient), emotional stability (insecure-secure, nervous-at ease, relaxed-tense, unexcitable-excitable [with excitable scored as high ES due to interitem correlations]), intellect (unimaginative-imaginative, uninquisitive-curious, uncreative-creative, imperceptive-perceptive). Participants rated how well the adjective described them or their target during the previous 20 minutes, on 1–7 scales. Target and observer Cronbach’s alphas for these assessments can be found in Fleeson and Law (2015, p. 1094).

Results

What is the Degree of Agreement on Big Five Personality States in Different Situations?

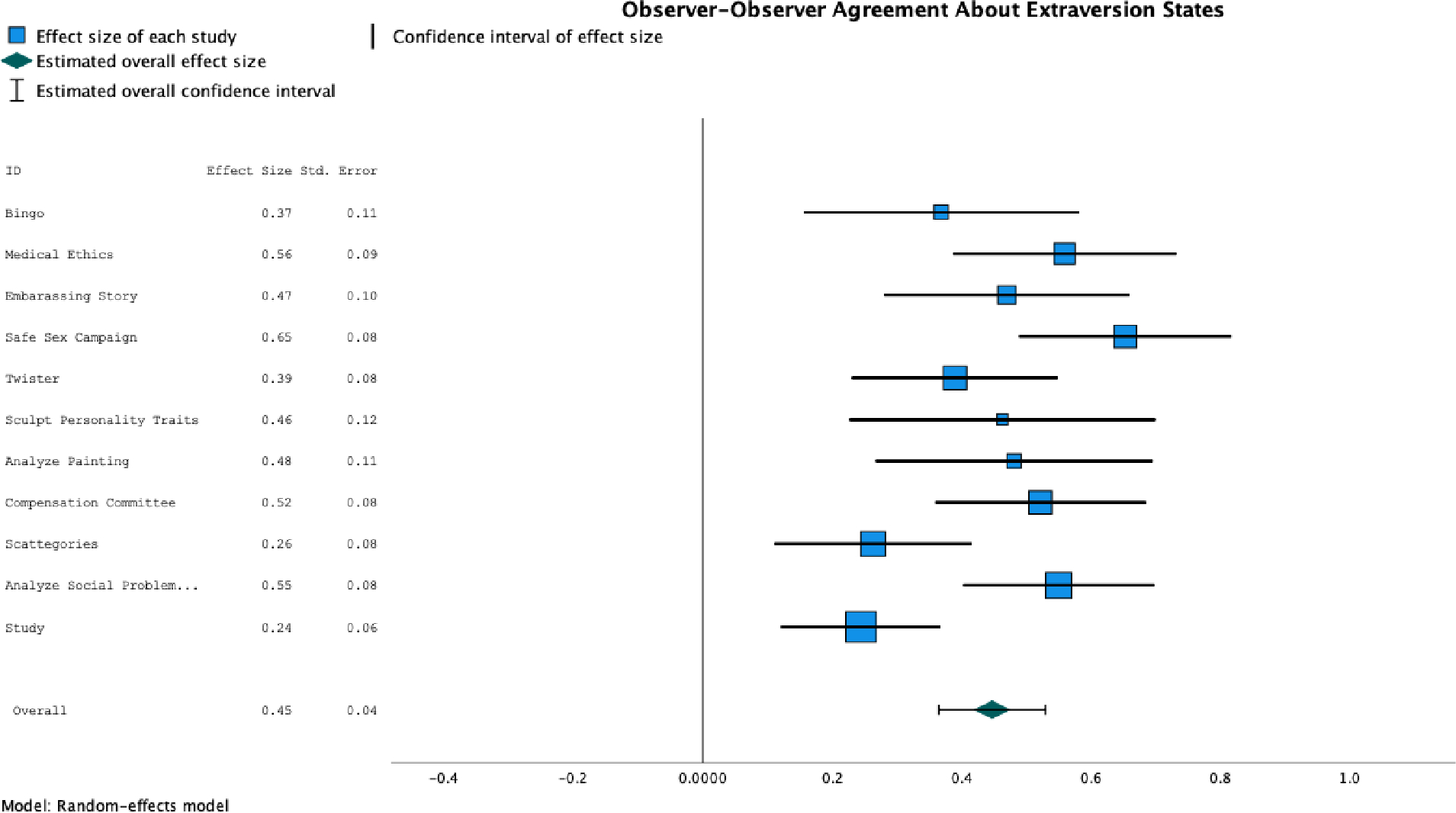

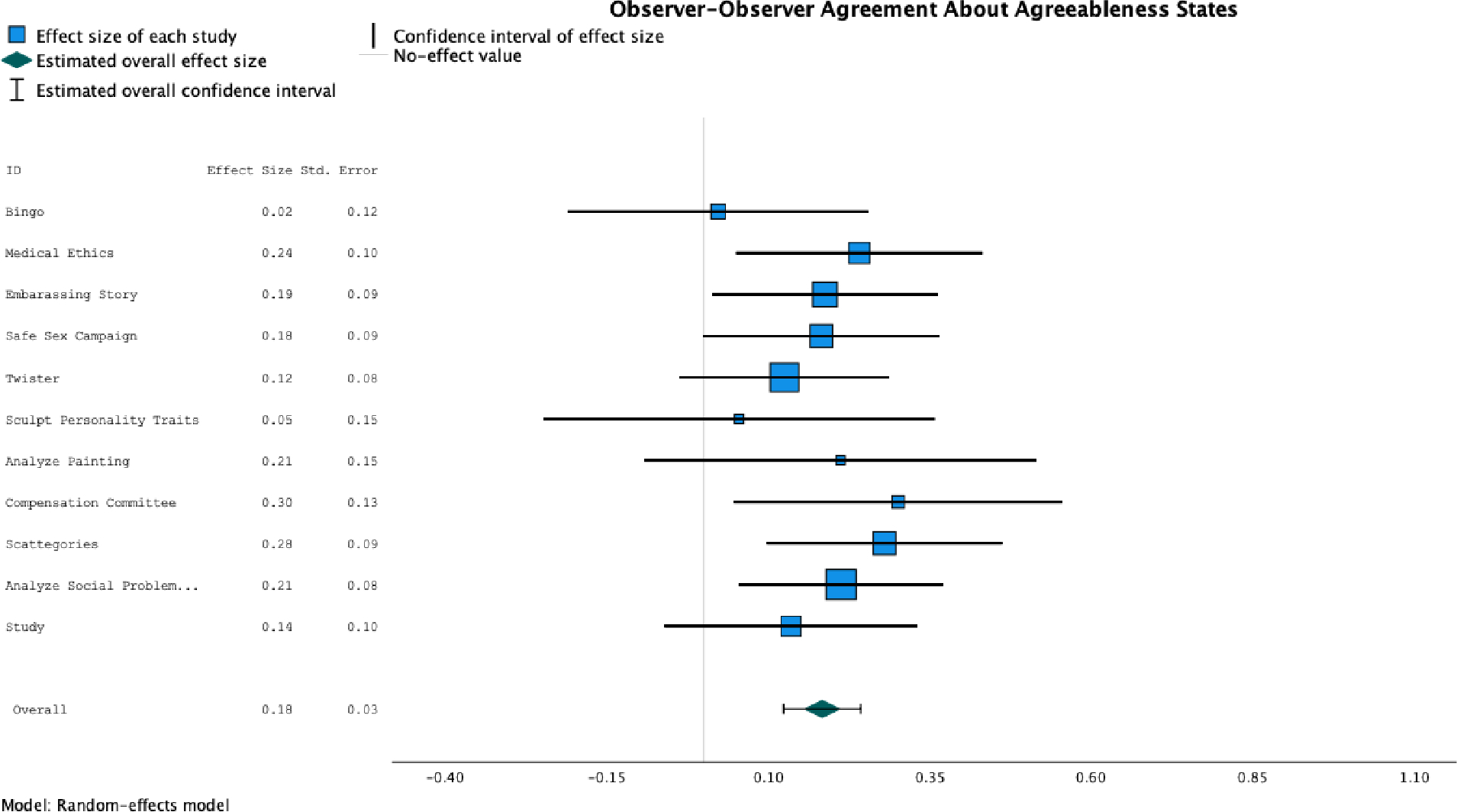

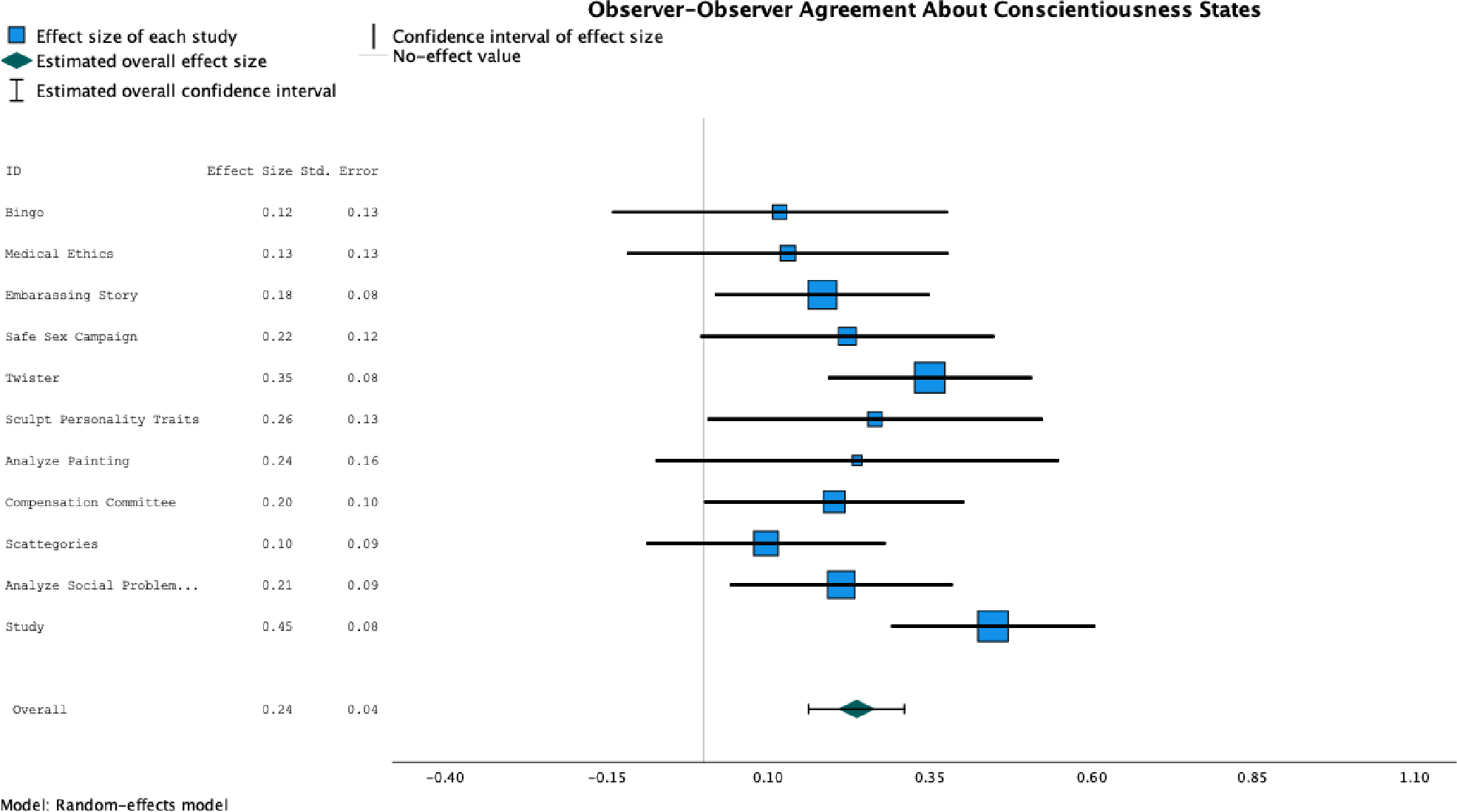

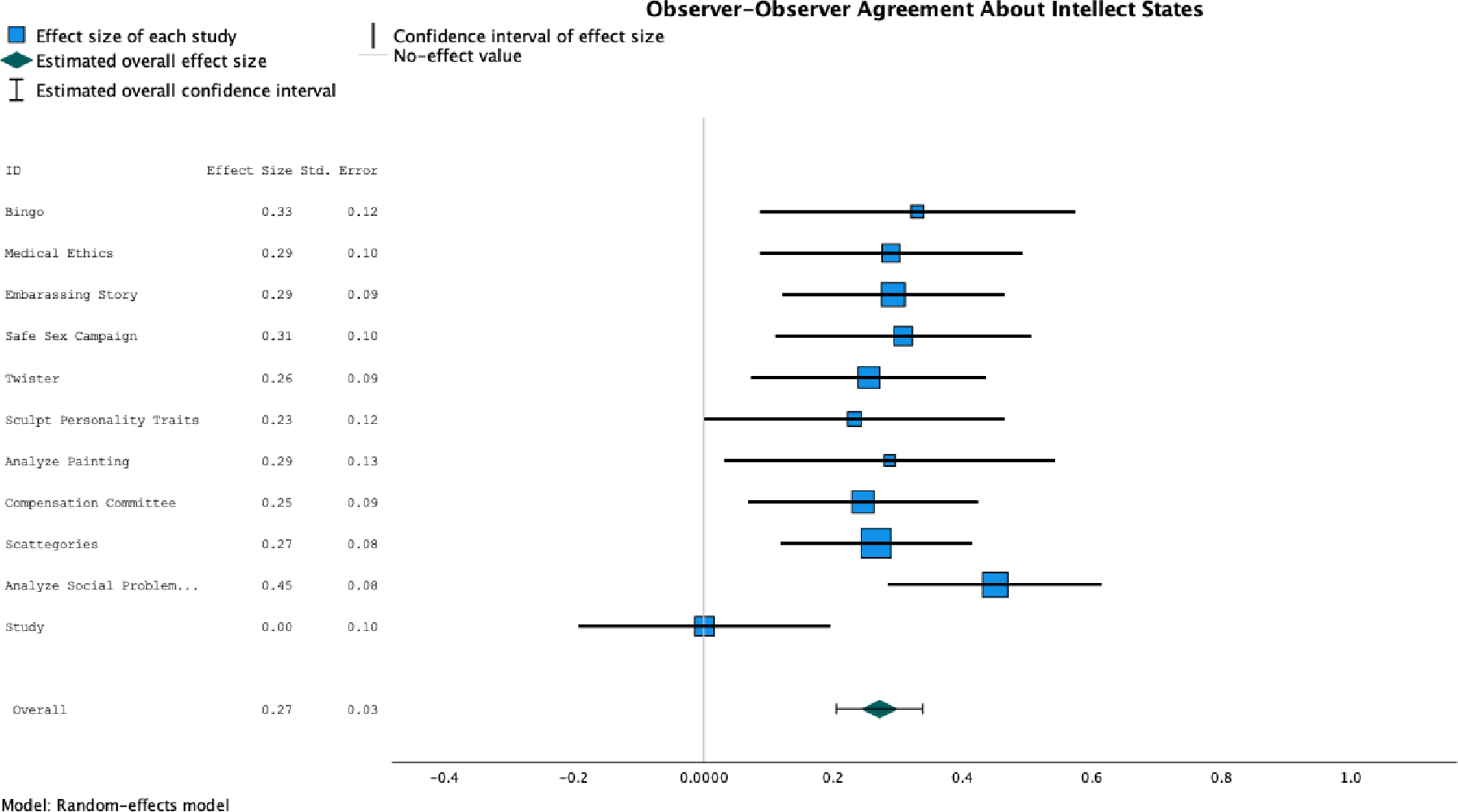

The first situation participants acted in was playing bingo. The first lines of the forest plots in Figure 1 show unstandardized coefficients of five MLM’s, each one predicting Observer 1’s rating from Observer 2’s rating of the same target, with intercepts allowed to vary randomly across targets. Because each participant contributed two reports, MLM was used to account for the resulting dependency. This analysis is nearly equivalent to a regression in which the DV is Observer 1’s rating and the IV is Observer 2’s rating. The important difference is that MLM accounts for the fact that each rater provided two ratings per session (one at the middle and one at the end of each session; the pattern of results was highly similar with OLS regressions).

Figure 1:

Forest Plots Depicting Observer-Observer Agreement in Each of the Situations with Two Observers

Agreement was significant and strong for three of the traits: Extraversion, Emotional Stability, and Intellect. These coefficients can be interpreted similarly to unstandardized regression coefficients, describing the degree to which relative deviations in Observer 1’s ratings corresponded to relative deviations in Observer 2’s ratings. Because the variances for state ratings were generally around 1.0, standardized coefficients would be close to these unstandardized coefficients.

These results for bingo are analogous to a typical agreement study, in which only one or a few situations are used, and between-person deviations are evaluated for agreement. Fortunately, there were multiple situations in this study, and this analysis can be repeated for each of the eleven situations in which two observers were present (Figure 1; because of absences of the target or an observer, the N’s varied across analyses). The average agreement across the eleven situations from meta analyses, depicted at the bottoms of the forest plots, was positive, moderate to strong, and significantly greater than zero for each trait content, all Z’s > 6, all p’s < .001. Agreement about differences between target extraversion states was significant in 11 of 11 situations. For agreeableness, it was significant in 5 of 11 situations, for conscientiousness in 4 of 11 situations, for emotional stability in 9 of 11 situations, and for intellect in 9 of 11 situations. Observers agreed how the targets were acting and about the characterization of those behaviors in terms of all of the Big 5 states. Forest plots of observer-observer agreement (Figure 1) reveal the precision of each situation’s estimate of agreement level, showing 95% confidence intervals for each beta, and also show the situations which differ from each other in their agreement levels.

Observer-observer agreement did vary across personality state contents (Figure 1). Extraversion achieved the highest observer-observer agreement, followed by emotional stability, intellect, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. Observer-observer agreement also varied across situations. For example, agreement about differences between targets’ states was highest in the situation in which they were analyzing drawings about social problems. The situation in which agreement about state agreeableness levels of the targets was highest was when they were acting out a mock compensation committee. Conversely, the highest level of agreement about targets’ state levels of conscientiousness was in the studying situation (which did not produce agreement about targets’ state levels of intellect). Thus, the situation in which a researcher investigates agreement may strongly affect the level of agreement found.

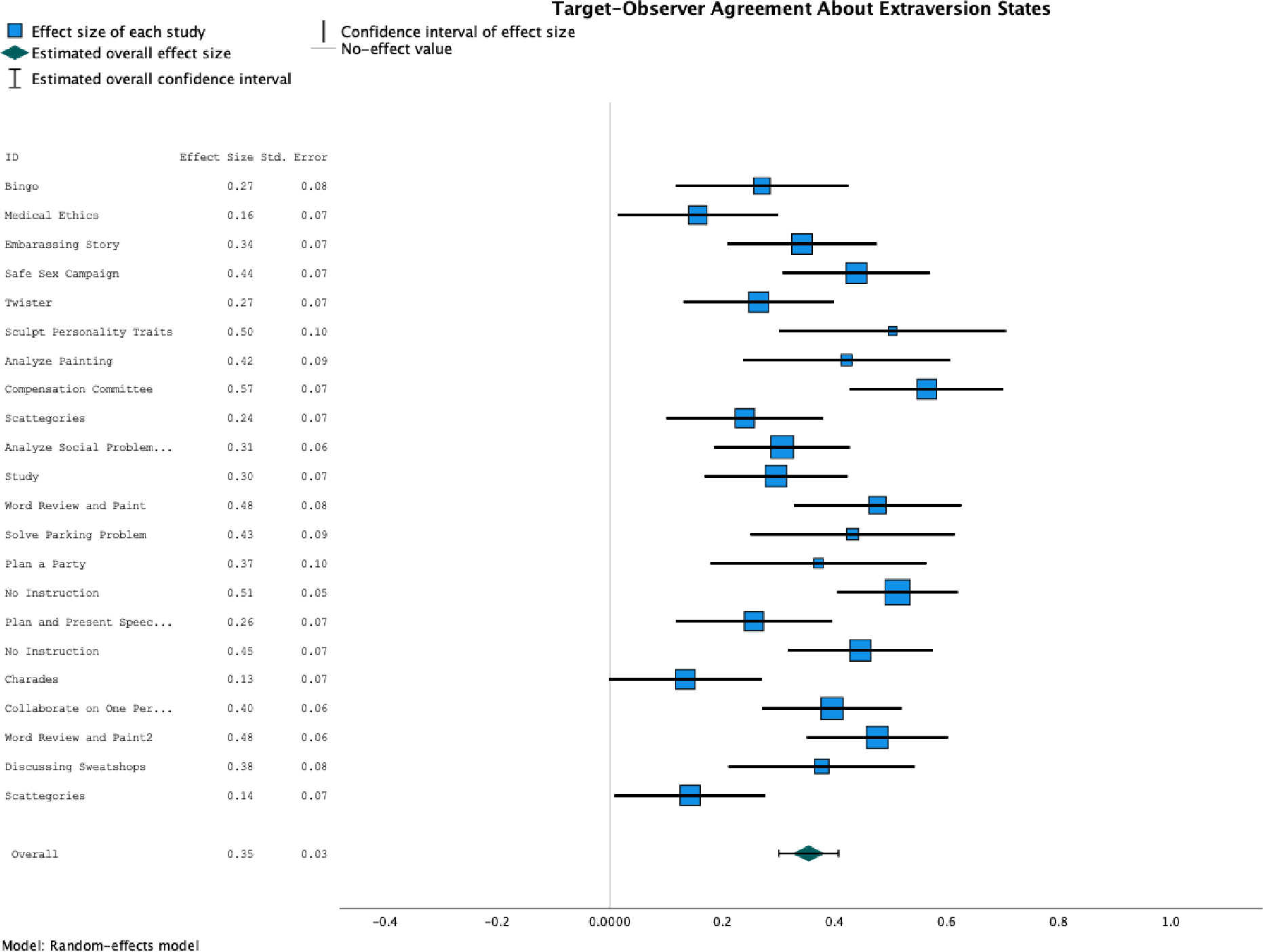

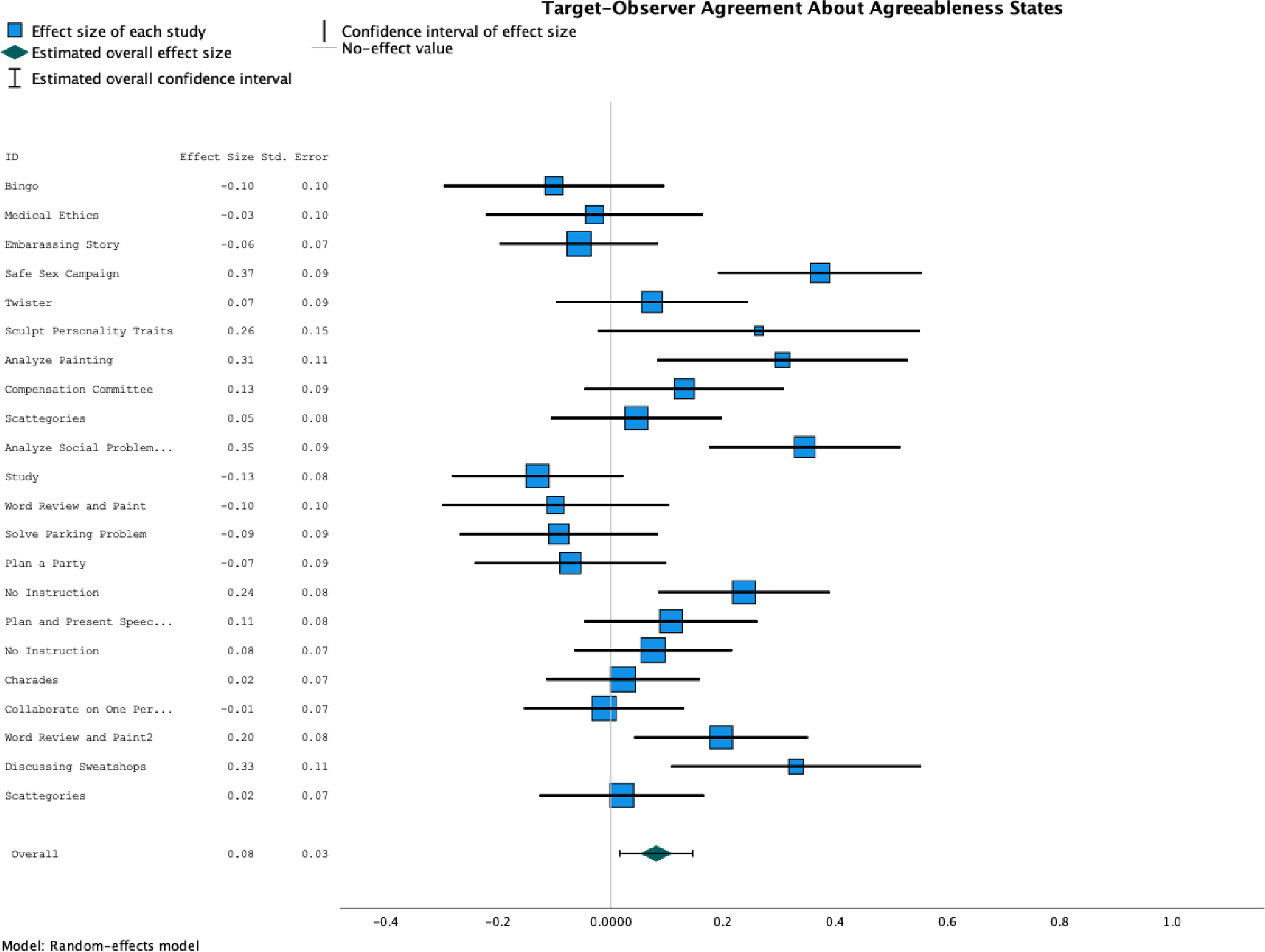

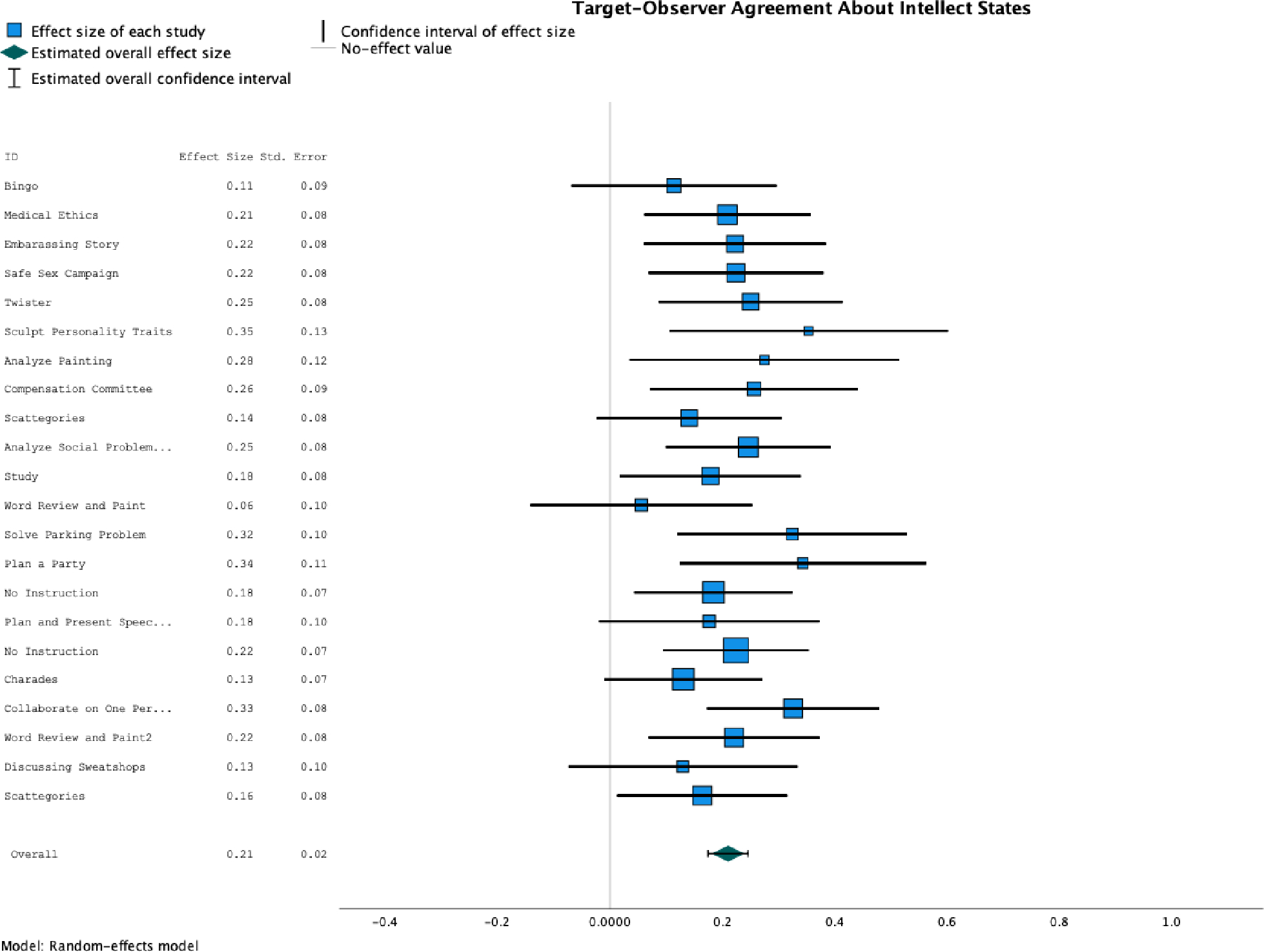

Target-observer agreement compares perceptions when one of the perceivers is also the source of the behavior. Figure 2 shows unstandardized coefficients from MLM’s; the MLM’s were the same as for the results in Figure 1, except that each one predicted the targets’ ratings (DV) from the average of the two observers’ ratings of the target (IV; when only one observer was available, then they were predicted from only that observer)4. Forest plots of target-observer agreement are presented in Figure 2. Agreement was positive about every state in almost every situation and was moderate and significant in most. The average agreement across the 22 situations from meta analyses, depicted at the bottoms of the forest plots, was positive, moderate to strong, and significantly greater than zero for each trait content, all Z’s > 2.4, all p’s < .05. Agreement about differences between target extraversion states was significant in 21 of 22 situations. For agreeableness, it was significant in 6 of 22 situations, for conscientiousness in 15 of 22 situations, for emotional stability in 12 of 22 situations, and for intellect in 16 of 22 situations. Observers agreed with targets about how the targets were acting and about the characterization of those behaviors in terms of all of the Big 5 states.5

Figure 2:

Forest Plots Depicting Target-Observer Agreement in Each of the Situations

What is the Degree of Target-Observer and Observer-Observer Agreement on Changes in Personality States across Situations?

Assessing the same subjects in multiple situations allows the unique opportunity to discover the degree of agreement about changes in states over short periods of time, such as minutes or days. The data across all targets and all situations were combined into a multi-level structure in which each subject had a row for each half-session (up to 39 rows per target, 3493 rows in total). To assess target-observer agreement about targets’ states, a separate MLM was run for each state (Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience). In each MLM, the DV was the targets’ ratings of their own states, and it was predicted from the average of the two observers’ ratings of the same target; resulting coefficients reveal the degree to which the targets and observers agreed on the targets’ states. The observers’ ratings were broken down into two parts: (i) the observers’ mean (or central) ratings of the targets across all situations and (ii) the deviations around these mean ratings in each situation (the centered ratings). This centering within targets isolated agreement about within-person changes across situations. The mean ratings of the traits were also included as predictors to assess agreement about mean levels of states. Coefficients were allowed to vary randomly across observer pairs.

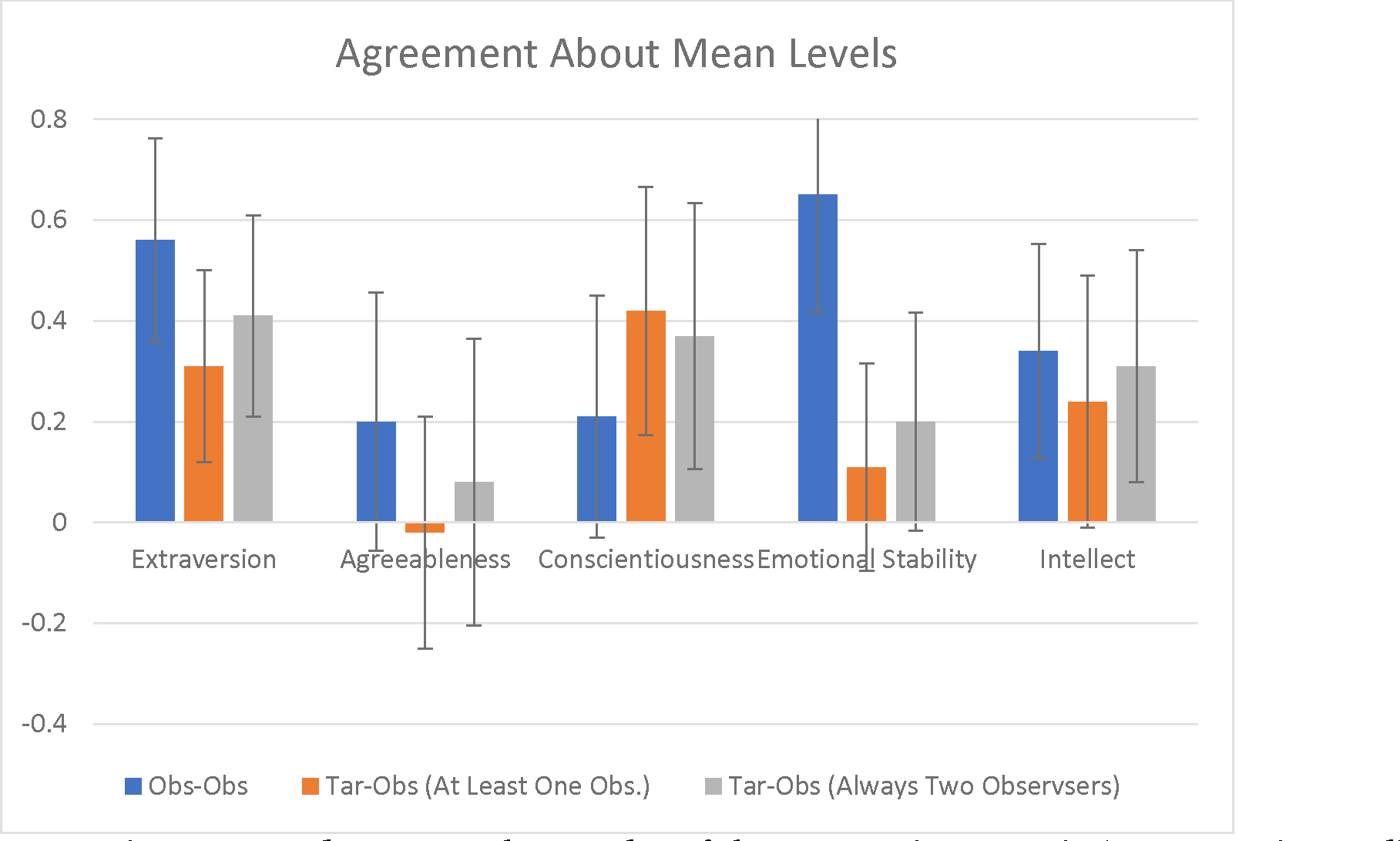

The middle bars in Figure 3 reveal the degree to which changes across situations in the targets’ ratings corresponded to changes across situations in their observers’ ratings. Because this is a multilevel model with centering, the results can be interpreted as describing agreement about one individual target’s states (the typical individual’s states) across the twenty-two situations. Agreement about extraversion states was highest, b = .53, p < .001, followed by conscientiousness, b = .35, p < .001, intellect, b = .32, p < .001, emotional stability, b = .20, p < .001, and agreeableness, b = .19, p < .001.6 That is, as the typical individual changed their state levels across situations, the target’s ratings of those changes agreed with the observer’s ratings of those changes. As shown in the middle bars of Figure 4, targets and observers also agreed on between-person differences between targets’ mean states, to comparable magnitudes, but significantly so for only two of the traits.7 These results suggest that, although targets and observers have partially different sources of information (e.g., the target has access to internal aspects of the states), targets and observers still agreed on fine distinctions in a person’s states as they shifted across situations. In other words, targets varied their behavior at different times, both targets and observers were able to detect those variations over time in the target’s behavior, and targets and observers agreed on those variations.

Figure 3:

Agreement About Personality States as They Change Across Sessions

Note. Figures 3 and 4 report the results of three MLM’s per trait (15 MLMs in total): one MLM predicting one observer’s ratings of a given target from another observer’s ratings of the same target (leftmost bar); one MLM predicting the target’s ratings from the average of two observers’ ratings (or one observer if only one was available, middle bars); one MLM predicting the target’s ratings from the average of two observers’ ratings (using only moments when both observers provided ratings, rightmost bars). Figure 3 shows the results for the centered ratings, removing influence from agreement about mean or average states. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4:

Agreement About Mean Levels of Personality States

Note. Figures 3 and 4 report the results of three MLM’s per trait (15 MLMs in total): one MLM predicting one observer’s ratings of a given target from another observer’s ratings of the same target (leftmost bar); one MLM predicting the target’s ratings from the average of two observers’ ratings (or one observer if only one was available, middle bars); one MLM predicting the target’s ratings from the average of two observers’ ratings (using only moments when both observers provided ratings, rightmost bars). Figure 4 shows the results for predictions from the mean ratings, revealing agreement about the average states the targets enacted. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

To assess observer-observer agreement about targets’ states, a separate MLM was run for each state (Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience). In each MLM, the DV was the primary observers’ ratings of their targets’ states, and it was predicted from the secondary observers’ ratings of the same target – coefficients reveal the degree to which the observers agreed on the targets’ states. The secondary observers’ ratings were broken down into two parts: the mean (or central) ratings of the target across all situations and the deviations around this mean rating in each situation (the centered ratings). This centering within targets isolated within-person changes across situations. The mean ratings of the traits were also included as predictors to assess agreement about mean levels of states. Coefficients were allowed to vary randomly across observer pairs.

Because this is a multilevel model with centering, the coefficients depicted in the leftmost bars in Figure 3 can be interpreted as describing agreement between two observers about an individual target’s states (the typical target’s states). The coefficients reveal the degree to which changes across situations in a primary observers’ ratings corresponded to changes across situations in the secondary observers’ ratings of the same target. Agreement about extraversion states was highest, b = .57, p < .001, followed by conscientiousness, b = .44, p < .001, intellect, b = .40, p < .001, emotional stability, b = .29, p < .001, and agreeableness, b = .14, p < .001. As shown in Figure 4, agreement about mean levels of states was also significant and sizeable for some traits, but not significant for others, possibly because the power to detect between-person differences was lower. Because the variances for state ratings were generally approximately 1.0, standardized coefficients would be close to these unstandardized coefficients. Thus, observers were in strong agreement about the states as those states changed across situations. Observers agreed about how the participants were acting and about the characterization of those behaviors in terms of Big 5 states8.

What is the Degree of Target-Observer and Observer-Observer Agreement on Changes in Personality States After Accounting for Normative Agreement?

Observed agreement about behavior partially reflects changes that are normative for the situation. This means that agreement may reflect only normative assumptions about the average person’s state levels in each of the situations. (Furr, 2008; Human et al., 2021). To create the normative level of each state in each situation, a mean was created for each state in each situation across all subjects and ratings. Then, to subtract out these normative ratings, each self-rating and observer rating was subtracted from the corresponding mean for that state for that situation. This created a distinctive profile, indicating the extent to which the ratings deviated from the norms for the situations (Furr, 2009b). Thus, each participant had two distinctive cross-situational profiles of behavior – one for her self-ratings (i.e., a self-distinctive profile of behavior) and one for her observers’ ratings (i.e., an observed distinctive profile of behavior). Distinctive agreement is thus simply the agreement/convergence/correlation between those two distinctive profiles.

We note that because we focus only on distinctive patterns of cross-situational variability in these analyses, it represents a very strong test of agreement. Five MLM’s (one per trait content) predicted observer one’s distinctive component from observer two’s distinctive component (after centering observer two’s ratings within target), allowing both the intercept and the observer 2 component to have both fixed and random components. Distinctive agreement remained significant (and moderate) in all cases: extraversion, b = .44, p < .001, conscientiousness, b = .30, p < .001, intellect, b = .32, p < .001, emotional stability, b = .24, p < .001, and agreeableness, b = .13, p < .01. Thus, observers agreed about how the targets’ states were deviating from the norm across situations, and agreement on state was not a byproduct of situation effects. Similarly, target-observer distinctive agreement remained significant (and moderate) in all cases: extraversion, b = .42, p < .001, conscientiousness, b = .29, p < .001, intellect, b = .23, p < .001, emotional stability, b = .18, p < .001, and agreeableness, b = .15, p < .001. Thus, , observers agreed with targets about how the targets’ states were deviating from the norms for the situations, and agreement on states was not a byproduct of situation effects. 9

Are There Individual Differences in the Amount of Observed Target-Observer and Observer-Observer Agreement?

MLM analyses also revealed whether different observer-observer pairs had significantly different levels of agreement about the changes in states across the situations. This indicates whether some targets were perceived in a more consensual way than were other targets and may reflect individual differences in target transparency. That is, Figures 3 and 4 showed agreement levels for the typical target and observer pairs, whereas this further result describes how much pairs varied around those typical levels of agreement. The variance component on the agreement coefficient indicates how much pairs differed from each other in their levels of agreement and whether the differences were significantly greater than expected from chance. Reported as a standard deviation, it can be roughly interpreted as the +/− interval around the average coefficient in which 2/3 of the pairs fell. For example, for extraversion the variation was s = .17, p < .05. This means that some observer pairs agreed more with each other about their targets’ state changes than did other observer pairs, and about 2/3 of the pairs had agreement coefficients between .39 and .73 (.56 +/− .17). The least agreeing pairs nonetheless agreed moderately well about how extraverted their targets were acting, whereas the most agreeing pairs agreed very closely about how extraverted their targets were acting.

For four of the traits, some observer pairs agreed significantly more about their targets’ state changes than did other observer pairs: agreeableness, s = .19, p < .05; conscientiousness, s = .26, p < .01; emotional stability, s = .15, ns; intellect, s = .22, p < .01. The agreeableness agreement differences are interesting because approximately 2/3 of the pairs had agreement levels between −.05 and .33, meaning that some pairs did not agree at all about how agreeably their targets were acting, whereas other pairs agreed moderately well about how agreeably their targets were acting.

Target-observer pairs differed significantly in levels of agreement across all five traits: extraversion s = .21, p < .001; agreeableness, s = .18, p < .001; conscientiousness, s = .22, p < .001; emotional stability, s = .16, p < .01; intellect, s = .17, p < .001. Thus, for extraversion, conscientiousness, and intellect, it was nearly universal for targets and observers to agree with each other about the target’s state changes, but some pairs very closely agreed whereas other agreed only moderately. For emotional stability and agreeableness, in contrast, assuming a normal distribution of agreement, some target-observer pairs did not agree at all about the target’s state changes, whereas most showed between small and moderate agreement.

Supplementary Subcomponent Analyses.

We also examined an additional supplementary question. Because Big Five traits are not univocal characteristics, but rather are composed of somewhat independent subcomponents (Costa & McCrae, 1995; Crowe et al., 2018, DeYoung et al., 2007; Anusic et al., 2009; Paunonen, 2003), they may represent unique features of a person that can be at different levels within a given person. Thus, levels of agreement about different subcomponents, even of the same broad trait, may differ.

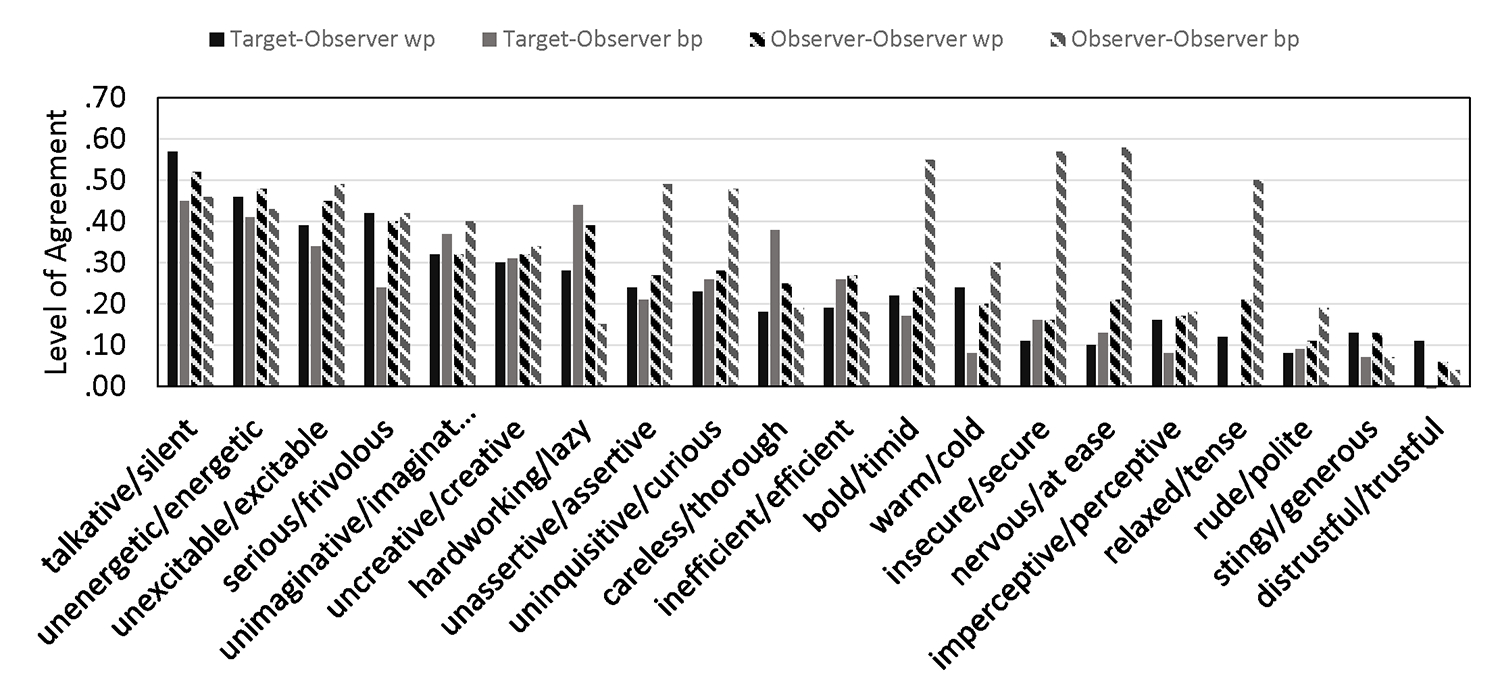

The results of these analyses are presented in Figure 5. The left two bars for each subcomponent show the results of MLM analyses, each predicting a target’s state ratings from an average of the primary and secondary observers’ state ratings (if only one observer was available, as in the second half of observations, then only the one observer was used). The observers’ centered ratings and the intercept were modeled as having both a fixed and random component. The first bar shows the prediction from centered observer ratings, and therefore shows agreement about within-person changes; the second bar shows the prediction from each observer’s central rating, and therefore shows agreement about differences between targets in average levels of the subcomponents. Agreement varied considerably across the subcomponents, ranging from .57 for talkative/silent to .08 for rude/polite.10

Figure 5:

Agreement About Subcomponent States

Note. Wp agreement is agreement about changes in states within a person over time, revealed by the coefficient on the centered observer rating. Bp agreement is agreement about differences between people, revealed by the coefficient on the central or mean rating by the observer of that target.

Figure 5 also shows observer-observer agreement in the two right bars for each subcomponent, in which a primary observer’s ratings was predicted from a secondary observer’s centered and central ratings, with the secondary observers’ centered ratings and the intercept both having fixed and random components. Within-person observer-observer agreement was significant for all subcomponents and varied from .52 for talkative/silent to .06 for distrustful/trustful. The pattern across subcomponents was similar to the pattern for target-observer agreement, with the exception that observer-observer between-person agreement was much higher for some subcomponents, mostly those involving neuroticism.

Overall, substantial target-observer agreement was observed for the subcomponents related to Extraversion, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience, while the observed agreement for those related to Agreeableness and Emotional Stability was lower. Between-person and within-person agreement levels varied over subcomponents in similar ways. Additionally, targets and observers significantly agreed on the unique aspects of 18 of 20 subcomponents; that is, after controlling for perceptions of the subcomponent’s parent trait. These results provide evidence of meaningful target-observer agreement at the subcomponent level.

Robustness to Design and Analysis Decisions

One of the reasons we analyzed the data in multiple different ways and presented the corresponding results in the paper was to reveal the degree of robustness of the conclusions across different design and analytic decisions. The goal was to show the degree to which the conclusions were affected by changes in the analytic approach. (The goal was also to show the times when conclusions may be different for different approaches.) Across the multiple ways of analyzing the data, the conclusion that targets and observers agree on changes in personality states across time was robust to design and analysis decisions.

Targets and observers agreed with each other about targets’ states when analyzed in single situations. Targets and observers agreed with each other about targets’ states when analyzed in different kinds of situations. Targets and observers agreed with each other about targets’ states when change in states were analyzed across situations. Targets agreed with single observers and with averages of multiple observers. Observers agreed with other observers. Targets and observers agreed with each other after accounting for normative behavior in situations.

The pattern across traits was generally robust. Highest agreement levels were found for extraversion, then conscientiousness and intellect, and finally the lowest levels were found for agreeableness and emotional stability. The main exception to this pattern was that observers showed very strong agreement about mean levels of emotional stability (possibly reflecting stereotypes about anxiety).

Additionally, we reran the analyses for Figures 3 and 4 after restoring targets who had been excluded for completing only a small number of sessions. For observer-observer agreement, results were very similar: extraversion, state b = .56, p < .001, mean-level b = .56, p < .001; agreeableness, state b = .15, p < .001, mean-level b = .13, p = .28; conscientiousness, state b = .44, p < .001, mean-level b = .18, p = .11; emotional stability, state b = .28, p < .001, mean-level b = .66, p < .001; intellect, state b = .40, p < .001, mean-level b = .38, p < .001. For target-observer agreement in cases with both observers, results were also very similar: extraversion, state b = .59, p < .001, mean-level b = .41, p < .001; agreeableness, state b = .30, p < .001, mean-level b = .15, p = .28; conscientiousness, state b = .48, p < .001, mean-level b = .37, p < .01; emotional stability, state b = .30, p < .001, mean-level b = .23, p < .05; intellect, state b = .44, p < .001, mean-level b = .32, p < .01.

The biggest variations in results due to design decision appears to come from selecting the situation in which the agreement is assessed. Observed agreement levels may vary quite a bit from one situation to the next. This needs to be addressed in future research.

Discussion

Do people agree on how they and others are acting? As shown from the present study’s results, the answer is positive. Targets and observers agreed when using others’ personality states as the comparison standard (“between-person agreement”) and when using the same person’s state manifestations in different situations as the comparison standard (“within-person agreement”). Targets and observers agreed on Big Five personality states in different situations, across all situations, and after accounting for normative agreement. Individuals also differed in the amount of observed target-observer and observer-observer agreement, with these differences being particularly pronounced for Emotional Stability and Agreeableness. Agreement also occurred at the subcomponent level, as well as for distinctive profile agreement across situations.

Agreement About Behavior Should Be Examined in Multiple Situations

Regarding the first research question, substantial variability was seen in the differential target-observer agreement observed across the 22 different situations. For example, there was significant agreement about Extraversion across all situations except a few (planning and presenting a speech, studying, and discussing medical ethics). Target-observer agreement was achieved for a smaller number of situations in the case of Emotional Stability and Agreeableness. These few situations may have afforded easy ways to exhibit all levels of content of those traits (e.g., discussing sweatshops for Agreeableness).

These observed patterns of agreement across different situations have clear implications for future research. For example, the two “no instruction” situations revealed the typical pattern of strong agreement on extraversion, conscientiousness, and intellect, and lesser agreement on emotional stability and agreeableness, whereas planning and presenting a speech revealed high agreement for conscientiousness and moderate agreement on the other traits. This means the choice of situation matters in which one studies agreement and may lead to very different conclusions. Most research on agreement uses situations similar to “no instruction”, such as “get to know each other”, and it may not be surprising that extraversion is the main trait that visibly distinguishes actors in such situations. If instead, most of the situations in past research had been similar to “studying” or “planning a speech”, then conscientiousness may have emerged as the most agreed upon trait. Researchers should therefore employ multiple situations when assessing agreement and acknowledge that their findings may not generalize beyond the situation they chose. Another implication of this finding is that future research should examine why situations affected agreement in future studies. For example, situations may differ in the extent to which they are relevant for a given trait (Rauthmann et al., 2015), provoke a given trait (Hartley et al., 2011), afford a moderate level of the trait (Blum et al., 2018), produce variance in the trait (Blackie et al., 2017), or highlight the trait (Zachry et al., 2018).

Implications for Process Models of Personality

The observed moderate to high levels of agreement suggest that people do agree to a substantive degree in their perceptions of the social world. People agree with others about much of their own behavior and people agree with others about other people’s behavior. This implies that people are mostly acting in the same reality as others, that behavior mostly come across as expected, that there are not huge disparities in the perception of the most basic facts about interpersonal interactions, effective interactions are facilitated, and self-awareness of one’s behavior is in accord with others’ perceptions.

This evidence is key for process approaches to personality (e.g., Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2021) that posit changes across time in personality expression as meaningful changes in personality expression. As discussed earlier, process approaches to personality try to illuminate personality by investigating changes in personality-expressive behavior over short periods of time (e.g., Baumert et al., 2017; Fleeson & Jayawickreme, 2015; 2021). Such approaches aim to document that such changes exist (Fleeson & Gallagher, 2009), to explain such changes, and to discover their consequences. This study adds an important piece of validity for such changes, in that multiple perceivers agreed on which changes in personality expression were happening. Rapid personality changes within a person over time are both common and valid and represent a legitimate phenomenon to investigate. Furthermore, the present results provide important evidence that self-report assessments of behavior are a trustworthy tool to assess such expressions in personality and to explain such processes.

This study was also the first to examine whether self-reported personality states are valid and similar to ratings that independent observers would provide. These results therefore provide validity evidence for the state assessment of behavior (Finnigan & Vazire, 2018; Sun & Vazire, 2019). Rather than referring to concrete behaviors, state assessments typically consist of adjectives, in order to measure the personality of the actor in the moment. Thus, state assessments are not concrete, require judgment, and employ rating scales. These features rightfully raise concern about the trustworthiness of state assessments. Nonetheless, these studies revealed good agreement at both the trait and subcomponent level, suggesting that state assessments indeed are trustworthy.

Evidence for the Validity of Experience Sampling as an Assessment of Behavior

By extension, these findings provide evidence for the validity of ESM as a methodology to assess personality states. Further establishing the validity of ESM is important, given that the methodology has been used to address fundamental questions in personality psychology, such as the existence of personality traits, trait consistency, and variability in well-being (Lucas et al., 2021). However, as noted above, ESM can be affected by systematic error caused by self-concept and self-enhancement biases, as well as by random unsystematic error. This has led to claims that direct behavioral observation is the best (Furr, 2009a) or even the only (Back & Egloff, 2009) way to measure behavior. However, direct behavioral observation can also be affected by systematic sources of error including shared stereotypes (Fleeson, 2009). Moreover, while ESM is based on self-reports of behavior, the immediacy built into the methodology means that a great deal of salient and immediate behavioral information is passed through a thin filter of self-concept. This filter is arguably thinner than other methods using self-reports of behavior (Furr, 2009a).

The present study therefore provided evidence for the trustworthiness of self-reported personality states assessed in ESM studies. This validity evidence showed through in a wide variety of tests, including some subtle ones, which required a great deal of fidelity in judgment. For example, perceivers agreed about personality states in different situations even after controlling for normative agreement.

It is worth considering why distinctive agreement remained high, given that distinctive agreement is often attenuated dramatically after accounting for normativeness (Human et al., 2021). In those studies, normativeness is usually examined for agreement on individuals’ overall trait profile. In contrast, the current study examines agreement on an individual’s cross-situational behavioral profile. Additional analyses suggest that the normative situational profile in the current context is simply less robust than the normative trait profile as observed most agreement studies. Thus, controlling for normativeness in the current study has less of an effect than typical, leaving distinctive agreement closer to overall agreement.

Implications for Person Perception Research

Regarding the fourth research question, individual differences were observed in the amount of target-observer and observer-observer agreement. High agreement was obtained for Extraversion (~.50), Conscientiousness (~.35) and Intellect (~.35), while Emotional Stability and Agreeableness exhibited lower levels of agreement (~.25 and ~.20, respectively). Notably, these levels of agreement are similar to levels of agreement reported in past studies on between-person agreement on behavior (e.g., Ozer & Buss, 1991; Gosling et al., 1998). This further suggests that there is still a reasonable amount of unshared reality, especially with regards to Emotional Stability and Agreeableness (Beer & Vazire, 2017).

What are the implications of these results for our understanding of person perception? Models of person perception typically rely on perception of behavior first, followed by subsequent inferences about traits based on those behaviors (Borkenau et al., 2004; Funder, 1995; Uleman & Saribay, 2012; Kenney, 2004). Given that inference processes from behaviors to traits are likely to generate at least some error or inaccuracy, agreement about behaviors is necessary to start at least at a moderate to high level, in order to support those inferences. This study provided evidence that agreement does start at a moderate to high level for at least some traits, supporting such behavior-based models. But we note that agreement was not extraordinarily high, and modest for Emotional Stability and Agreeableness, suggesting that person-perception models may need to accommodate these findings. Specifically, they need to address the possibility that errors are happening early in the process, that the resulting inferences may suffer in accuracy, and that agreement at the trait level may be contaminated by potentially irrelevant, non-behavioral information.

This is especially true for Agreeableness. Agreeableness was assessed in this study with the facets of warmth, trustfulness, generosity (vs. stinginess) and politeness (vs. rudeness), suggesting that one’s judgment of how warm or generous another is being may have little to no correspondence with another’s judgment of how warm or generous that same person is being. The relatively low levels of agreement about agreeableness were also in line with past studies on between-person agreement on behavior (e.g., Gosling et al., 1998; Ozer & Buss, 1991; Sun & Vazire, 2019) and traits (John & Robins, 1993).

This reduction in levels of agreement may result from multiple factors (Vazire, 2010). Targets have insights into internal processes (e.g., feelings, thoughts, and motives) that influence behavior, and are also aware of idiosyncratic changes in behavior. Targets are additionally invested in the social desirability of their behavior and may not perceive (or accurately weight) the way their behavior looks to the outside. Conversely, observers are not subject to self-presentational or self-enhancement strategies (Borkenau & Zaltauskas, 2009; John & Robins, 1994), although they are subject to superficiality biases, such as the use of physical cues, status, and stereotypes (Fleeson, 2009; Uleman & Saribay, 2012). Different beliefs about behaviors can lead to different judgments of similar actions (e.g., one person might think honesty is rude whereas another person might see honesty as polite). Further research on these processes and how they vary across traits is warranted (e.g., Mottus, Allik, & Realo, 2020).

Relatedly, we note that although the level of agreement on aggregates was comparable to that for single states (Figure 3), it was not at the high levels one might expect from aggregates. One possible reason is that aggregation not only purifies the accurate part of the rating, but also any other repeated component of the rating (Leising et al., 2010), such as (i) private sources of information; (ii) individual response styles; and (iii) individual interpretations of the states. If any or all of these are consistently present in all ratings of a given state, then aggregating across that state would magnify those effects. Another possible explanation is that aggregation included fewer diagnostic situations, adding error to the aggregates. Future research is needed to address agreement about aggregates.

Limitations

Despite the innovative nature of the present study’s design, we acknowledge a number of limitations. One limitation was that the same observers were used for a given target throughout the study. Thus, observers formed impressions about their targets and any observer bias would have accumulated within a target over time. Observers may have stuck to early-formed impressions of the actors. Although the within-person analyses adjusted for any consistent rater effects that would have been present, the between-person analyses did not. Future research could employ a new observer for each session.

A second limitation was that the activities took place in a lab rather than in a more natural context. During the activities, actors were videotaped. These factors could have created self-consciousness, reactance, or artificiality in the actors’ behavior. Thus, the activities may not have perfectly recreated the kinds of activities that occur in daily life, although we went to extensive efforts to make them do so. Experts conclude that the maximum time to adaptation to videotape is about six hours, so this study likely avoided that problem, and the activities were probably similar enough to everyday activities not to interfere greatly with the amount of agreement about behavior. Furthermore, the subjects varied their behavior across the situations in meaningful ways and about as much as they vary their behavior in everyday life (Fleeson & Law, 2015).

A third limitation was that while there were only four items assessing each trait, there were also arguably too many items per report (20 state items plus affect, goal, and situation items). The large number of items may have reduced observer fidelity to some extent; the small number of items assessing traits may have reduced reliability and breadth of the trait measures. However, the fidelity and reliability were both enough to create clearly distinct and repeated distinctions among the traits.

A fourth limitation of the present study was that we did not obtain situation characteristic ratings from participants during the study. Obtaining such data would have allowed us to examine the systematic relationship between the psychological characteristics of situations and agreement about personality state manifestations (Rauthmann et al., 2014; 2015), and provide insight as to why situations affected agreement.

However, as a preliminary step towards ascertaining the psychological characteristics of the situations in the present study, 79 raters (Mage = 18.7, SD = .79) rated the instructions for each of the situations in this study on the DIAMONDS situational taxonomy using the DIAMONDS- S6 (Rauthmann & Sherman, 2016; see Table S1 and S2 in supplementary materials for ICCs and mean ratings). The ratings suggest that levels of psychological characteristics varied substantially across the situations for some situational characteristics (e.g., Intellect, Positivity, Negativity), but not others (e.g., high levels of Sociability and Duty, low levels of Deception, Adversity, and Mating). However, we did not find consistent relationships between the situational characteristics and levels of agreement (see supplementary materials for ratings data, further details and discussion).

Conclusion

This study innovatively examined levels of agreement among targets and observers about the behavior a target is manifesting at any given moment, as it changes over time and across. These results suggest a substantial degree of shared reality about behavior and in self-awareness, which facilitates effective interactions, except for perceptions of agreeableness, which ironically may be the trait with the most direct impact on social interactions. The results also provide support for dynamic approaches to personality, which rely on rapidly varying and meaningful personality expressions as their basic data element. By extension, they provide evidence for the validity of state assessments of behavior. Finally, these findings also support behavior-based accounts of person-perception, in that they demonstrated moderate to high agreement at the early stages of person perception.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH70571. This publication was also made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Some studies have collected ratings of traits based on observations of behavior rather than collect direct ratings of behavior (Borkenau & Leibler, 1992; Borkenau, Mauer, Riemann, Spinith, & Angleitner, 2004; McLarney-Vesotski, Bernieri, & Rempala, 2006). Although such studies are similar to the current research, by collecting trait ratings those studies focus on agreement in the inferential process from behavior to traits rather than on agreement about behavior. Abrahams and colleagues (2021) collect target and informant ratings of personality from a sample of student teachers; however, the focus of this investigation was understanding person-situation dynamics, rather that agreement on personality states.

We are still conducting analyses on these data, and moreover the data have not been fully deidentified. However, we are happy to share the data with researchers interested in corroborating these results presented here.

Observers occasionally observed a different target due to scheduling difficulties – those data are not reported here. Additionally, two observers began the study as targets but were switched to the observer role after 1 or 2 sessions for balancing triads; only their observer data is included.

We used MLM for these analyses as participants provided two raters per situation (one after 25 minutes, and again after 50 minutes).

When limited to occasions in which both observers provided reports, agreement between targets and observers was higher: extraversion, b = .38, p < .001, conscientiousness, b = .28, p < .001, intellect, b = .24, p < .001, emotional stability, b = .27, p < .001, agreeableness, b = .18, p < .001.

If limited to cases in which both observers reported on the states, agreement between targets and observers was still higher, as shown in the rightmost bars in Figure 3. Thus, when the quality of observation was improved, it came more into line with target self-ratings.

Note that the beta for the agreement about a given state and the beta for the corresponding agreement about the mean level came from the same MLM. There were three such MLM’s for each state: one for obs-obs agreement and two for tar-obs agreement. These estimates of agreement about mean levels reimplement an analysis presented in Fleeson & Law, 2015.

To test for acquaintanceship effects, we repeated MLMs with week number as an additional predictor (week number was scored from 1–20). When predicting observers 1’s rating, the interaction between week number and observer 2’s rating revealed whether agreement changed linearly over time. Time predicted improved agreement for conscientiousness, b = .05, t (1002) = 4.53, p < .001, and marginally so for extraversion, b = .01, t (933) = 1.67, p = .096, but predicted worsened agreement for emotional stability, b = −.02, t (866) = −2.32, p < .05, and did not predict agreement for agreeableness, b = .01, t (816) = 1.0, p = .32, or intellect, b = .01, t (886) = 1.17, p = .24.

If limited to cases in which both observers reported on the states, distinctive agreement between targets and observers was even higher: extraversion, b = .45, p < .001, conscientiousness, b = .39, p < .001, intellect, b = .33, p < .001, emotional stability, b = .27, p < .001, agreeableness, b = .26, p < .001.

Limiting to cases in which both observers reported on the states, agreement was substantially higher (about .08-.09 points higher for the average subcomponent).

Supplementary data, materials, and syntax are available at https://osf.io/xajym/

References

- Abrahams L, Rauthmann JF, & Fruyt FD (2021). Person-situation dynamics in educational contexts: A self-and other-rated experience sampling study of teachers’ states, traits, and situations. European Journal of Personality, 35(4), 598–622. [Google Scholar]

- Albright L, Kenny DA, & Malloy TE (1988). Consensus in personality judgments at zero-acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM (1984). Self-knowledge and social inference: II. The diagnosticity of cognitive/affective and behavioral data. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, & Shirako A (2008). Are individuals’ reputations related to their history of behavior?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 320–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglim J, Horwood S, Smillie LD, Marrero RJ, & Wood JK (2020). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 279–323. 10.1037/bul0000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anusic I, Schimmack U, Pinkus RT, & Lockwood P (2009). The nature and structure of correlations among Big Five ratings: The halo-alpha-beta model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1142–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back MD, & Egloff B (2009). Yes we can! A plea for direct behavioral observation in personality research. European Journal of Personality, 23(5), 403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Back MD, Schmukle SC, & Egloff B (2008). How extraverted is honey. bunny77@ hotmail. de? Inferring personality from e-mail addresses. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 1116–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, & Funder DC (2007). Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior?. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(4), 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert A, Schmitt M, Perugini M, Johnson W, Blum G, Borkenau P, Costantini G, Denissen J, Fleeson W, Grafton B, Jayawickreme E, Kurzius E, MacLeod C, Miller L, Read L, Read SJ, Robinson MD, Roberts B, Wood D, & Wrzus C (2017). Integrating personality structure, personality process, and personality development. European Journal of Personality, 31, 503–528. [Google Scholar]

- Beer A, & Vazire S (2017). Evaluating the predictive validity of personality trait judgments using a naturalistic behavioral criterion: a preliminary test of the self-other knowledge asymmetry model. Journal of Research in Personality, 70, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bernieri FJ, Zuckerman M, Koestner R, & Rosenthal R (1994). Measuring person perception accuracy: Another look at self-other agreement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(4), 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Blackie LE, Jayawickreme E, Helzer EG, Forgeard MJ, & Roepke AM (2015). Investigating the veracity of self-perceived posttraumatic growth: A profile analysis approach to corroboration. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(7), 788–796. [Google Scholar]

- Blackie LER, Jayawickreme E, Tsukayama E, Forgeard MJ, Roepke AM, & Fleeson W (2017). Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Developing a measure to assess within-person variability. Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman MC, & Funder DC (1998). The effect of information on consensus and accuracy in personality judgment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 34(2), 164–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn W (2009). Linking personality states, current social roles and major life goals. European Journal of Personality, 23(6), 509–530. [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn W, Hopwood CJ, Back MD, Denissen JJA, Hennecke M, Jokela M, Kandler C, Lucas RE, Luhmann M, Orth U, Roberts BW, Wagner J, Wrzus C, & Zimmermann J (2020) Longitudinal experience-wide association studies—A framework for studying personality change. European Journal of Personality, 34, 285– 300. 10.1002/per.2247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blum GS, Rauthmann JF, Göllner R, Lischetzke T, & Schmitt M (2018). The nonlinear interaction of person and situation (NIPS) model: Theory and empirical evidence. European Journal of Personality, 32(3), 286–305. [Google Scholar]

- Borkenau P, & Liebler A (1992). Trait inferences: Sources of validity at zero-acquaintance, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 645–657. [Google Scholar]

- Borkenau P, Mauer N, Rieman R, Spinath FM, & Angleitner A (2004). Thin slices of behavior as cues of personality and intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 599–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkenau P, & Zaltauskas K (2009). Effects of self-enhancement on agreement on personality profiles. European Journal of Personality, 23, 107–123. doi: 10.1002/per.707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breil SM, Geukes K, Wilson RE, Nestler S, Vazire S, & Back MD (2019). Zooming into real-life extraversion—How personality and situation shape sociability in social interactions. Collabra Psychology, 5(1), 7. DOI: 10.1525/collabra.170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunswik E (1952). The conceptual framework of psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 49(6), 654–656. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EN, Vazire S, & Oltmanns TF (2013). Self-other knowledge asymmetries in personality pathology. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 155–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TR, Panter AT, Turan N, Morse L, & Kim Y (2013). Agreement and similarity in self-other perceptions of moral character. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(6), 816–830. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin CR, & Funder DC (1991). Predicting personality and behavior: A boundary on the acquaintanceship effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner TS, Barrett LF, Tugade MM, & Tennen H (2007). Idiographic personality: The theory and practice of experience sampling. In Robins RW, Fraley RC, & Krueger RF (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (p. 79–96). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JJ, Kavanagh EJ, & Viswesvaran C (2007). The convergent validity between self and observer ratings of personality: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 15(1), 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly BS, & Ones DS (2010). An other perspective on personality: Meta-analytic integration of observers’ accuracy and predictive validity. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1092–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT Jr, & McCrae RR (1995). Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64(1), 21–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]