Abstract

Background:

When a person’s workload of healthcare exceeds their resources, they experience treatment burden. At the intersection of cancer and aging, little is known about treatment burden. We evaluated the association between a geriatric assessment-derived deficit accumulation index (DAI) and patient-reported treatment burden in older adults with early stage, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of older adults with NMIBC (≥65 years). We calculated DAI using the Cancer and Aging Research Group’s geriatric assessment and measured urinary symptoms using the Urogenital Distress Inventory-6 (UDI-6). The primary outcome was Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) score. A negative binomial regression with LASSO penalty was used to model TBQ. We further conducted qualitative thematic content analysis of responses to an open-ended survey question (“What has been your Greatest Challenge in managing medical care for your bladder cancer”) and created a joint display with illustrative quotes by DAI category.

Results:

Among 119 patients, mean age was 78.9 years (SD 7) of whom 56.3% were robust, 30.3% pre-frail, and 13.4% frail. In the multivariable model, DAI and UDI-6 were significantly associated with TBQ. Individuals with DAI above the median (>0.18) had TBQ scores 1.94 times greater than those below (adjusted IRR 1.94, 95% CI 1.33-2.82). Individuals with UDI-6 greater than the median (25) had TBQ scores 1.7 times greater than those below (adjusted IRR 1.70, 95% CI 1.16-2.49). The top 5 themes in the Greatest Challenge question responses were cancer treatments (22.2%), cancer worry (19.2%), urination bother (18.2%), self-management (18.2%), and appointment time (11.1%).

Conclusions:

DAI and worsening urinary symptoms were associated with higher treatment burden in older adults with NMIBC. These data highlight the need for a holistic approach that reconciles the burden from aging-related conditions with that resulting from cancer treatment.

Keywords: geriatric oncology, bladder cancer, treatment burden, geriatric assessment, urinary symptoms

INTRODUCTION

By 2030, two-thirds of all new cancers will be diagnosed in older adults (≥65 years).1 At baseline, most older adults with cancer manage co-existing geriatric conditions such as multimorbidity, functional decline, and cognitive impairment. Adding a cancer diagnosis has the potential to expand the healthcare workload of older adults and their families to unmanageable levels. Management requires balancing of this healthcare workload (e.g. healthcare visits, self-management) with an individual’s physical, mental, financial, and social resources.2 Treatment burden results when a person’s healthcare workload exceeds their resources and has been associated with poor adherence to treatment, hospital readmission, and lower quality of life.3–7 There is increasing recognition of the additive effects of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship on treatment burden with potential downstream effects on adherence, tolerability, and quality of life.8

Notwithstanding, studies of treatment burden at the intersection of cancer and aging are limited.9 Prior studies either lack measures of geriatric conditions or apply narrow definitions of treatment burden, such as healthcare utilization, which fail to fully capture the patient experience.10–12 Validated patient-reported measures of treatment burden are available, but have been infrequently used to assess the experiences of older adults with cancer.

In this study, we collected validated geriatric assessment data and self-reported treatment burden from patients with early stage, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). We focused on NMIBC because it is a highly prevalent and burdensome malignancy that disproportionately affects older adults. The sixth most common cancer in the United States, bladder cancer has the highest median age at diagnosis of all cancer sites (73 years), high recurrence (up to 70%), and low mortality.13 Rather than a single major treatment with a limited time course such as chemotherapy or extirpative surgery, current guidelines recommend an ongoing regimen of weekly intravesical therapy, quarterly surveillance cystoscopies, and surgeries for recurrence resulting in many visits to urology per year.13 Further complicating this time-intensive treatment are high rates of multimorbidity among patients with bladder cancer.10,14

Our objective was twofold. First, we quantitatively evaluated the association between patient-reported treatment burden in older adults with NMIBC and their geriatric conditions as measured with the geriatric assessment-derived deficit accumulation index (DAI). Second, we qualitatively examined open-ended survey responses to assess the direct experience of treatment burden in older patients with NMIBC.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study with a convenience sample of older adults with NMIBC recruited from urology clinics at Geisinger, an integrated health system serving rural central Pennsylvania. Due to the cross-sectional nature of our study design and data, our study is exploratory and was limited to identifying the strongest risk factors for treatment burden rather than causal inference or risk prediction. This study identifies associations between patient factors including frailty and multimorbidity and self-reported treatment burden. We hope these associations can guide future studies aimed at evaluating prospective factors and ultimately interventions tailored to patient-specific age- and cancer-related characteristics to ameliorate treatment burden. Eligibility criteria included age ≥65 years at NMIBC diagnosis, diagnosed with NMIBC for ≥6 months, and able to read, write, understand English and provide informed consent individually or with the assistance of a healthcare proxy. We excluded patients who were treated with radical cystectomy for NMIBC, had non-urothelial carcinoma histology, or were unable to be consented due to cognitive impairment without a healthcare proxy.

This study was approved by the Geisinger Institutional Review Board. Study recruitment occurred from November 2019 through July 2021. A total of 266 eligible patients were identified, 130 enrolled (49%), and 119 returned surveys (45%, Supplemental Figure 1). Of the 63 patients who declined participation, the most common reason was lack of interest in participating in research (n=45, 71.4%).

Outcome

The primary outcome was patient-reported treatment burden as measured by the Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ, Supplemental Material). The TBQ was initially developed as a thirteen-item questionnaire in France based on a literature review and interviews with patients with one or more chronic conditions. It was then adapted, validated, and expanded for English-speaking patients into the fifteen-item questionnaire used in our study.15 The TBQ has previously been used with older adults and with cancer patients.16,17 The fifteen items measure patient-perceived burdens associated with managing ≥1 chronic conditions including medication management, arrangements for medical appointments and tests, self-monitoring, relationships, administrative and financial burdens, and adherence to physician recommendations.15,18 Fourteen items are scored on a 0-10 Likert scale with 0 indicating “Not a Problem” and 10 indicating “A Big Problem.” The fifteenth item is a global burden question (“The need for medical healthcare on a regular basis reminds me of my health problems?”) where zero indicates “Not at all” and 10 indicates “All the time.” Items are summed for a total score (range 0 to 150) with higher scores indicating greater patient-reported treatment burden. The TBQ was administered at one time point.

Exposure

The primary exposure was the Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI). Based on the deficit accumulation model of frailty, the DAI we used is a validated composite score derived from the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) geriatric assessment, selected laboratory values, and electronic health record data.19 The DAI has been used previously in other studies of older adults with cancer.20–23 The DAI was calculated for each enrolled patient by summing across all possible deficits and dividing by the total number of possible deficits for a range of 0.0 to 1.0 (full list in Supplemental Table 2). We imputed values for missing items. DAI was treated as continuous in multivariable analysis and as categorical for the mixed methods analysis: robust (<0.2), pre-frail (0.2<0.35), or frail (≥0.35).

The CARG geriatric assessment is a validated, mostly self-administered survey tool used to assess geriatric conditions relevant to older adults with cancer.24,25 In addition, clinicians or research staff administer selected assessments (e.g. cognitive screening, Timed Up and Go test, and physician-rated Karnofsky performance status).26,27 Almost all of our recruitment occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as a result, we transitioned from the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to the telephone-based Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) for cognitive screening to ensure the health and safety of our participants and research staff.28–30 We considered using a telephone version of the MoCA; however, we opted to use the TICS due to concerns raised by the co-creators of the MoCA regarding use in older adults with sensory impairment and limits of interpretation in non-standard conditions.31 After in-person research visits resumed in October 2020, we captured as many in-person assessments as possible from previously enrolled patients to reduce the amount of missing data to the greatest extent possible. However, Timed Up and Go and cognitive screening assessments had missingness due to some patients having died or not being accessible.

We also considered urinary symptoms (e.g. incontinence, urinary urgency, urinary frequency, pelvic discomfort) as an explanatory variable. Urinary symptoms and incontinence are known side effects of NMIBC treatment and are a common geriatric condition. Enrolled patients completed the short form of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), a validated survey with six questions that is scored from 0 to 100 with higher scores corresponding to greater distress from urinary symptoms.32,33

Covariates

Demographics included age at enrollment, age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, and employment status. We assessed health literacy using a single validated survey item (“How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”) with 5 possible responses.34 We categorized Somewhat, A Little Bit, and Not at All as low health literacy. We assessed financial hardship with a single validated item (“How hard is it for you to pay for the very basics like food, housing, medical care, and heating?”).35 We estimated distance and drive time from the patient’s home address to the primary urologist’s office using Google Maps. We calculated healthcare utilization for enrolled and non-enrolled patients to understand whether existing healthcare burdens impacted the decision to participate. We pulled clinical encounters from the electronic health record and calculated the total number of days engaged in clinic visits, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits in the year prior to being approached for the study. We defined recent NMIBC treatment as transurethral resection of bladder tumor and/or intravesical bladder instillation, and/or immunotherapy with pembrolizumab in the 3 month period immediately preceding the date of enrollment in the study. We selected 3 months because most NMIBC follow up and treatment occurs in 3 month intervals per American Urological Association guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

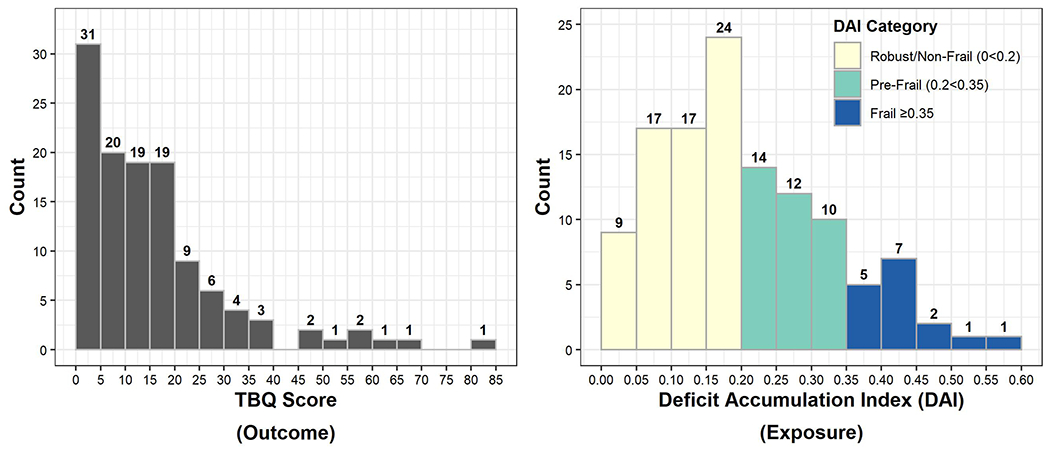

We calculated descriptive statistics for the demographic characteristics and geriatric conditions using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Histograms of the TBQ outcome variable and the primary exposure of DAI (with color-coded sub-categories of robust, pre-frail and frail) were presented to graphically describe their respective distributions. The proportions of each item in the TBQ outcome reported by the participants were illustrated in a bar chart.

There was missingness ranging from a small amount (0.8% in health literacy) to a large amount (34.5% in Timed Up and Go) which was assumed to be missing-at-random and multiply imputed 20 times.36 We evaluated several distributions for modeling the count outcome of TBQ as a function of the primary exposure, DAI, using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The negative binomial distribution was chosen using this criterion.

Prior to model selection, we considered whether temporal proximity of treatment might unduly influence our outcome measure. For this reason, we tested the unadjusted association of recent treatment (≤3 months) with the outcome to consider its potential inclusion as a candidate for the multivariable model. In order to select a parsimonious multivariable model of TBQ, the LASSO (least absolute shrinkage selection operator) as implemented in the R package “glmnet” was separately applied to each of the imputations.37 This approach can simultaneously consider a large number of explanatory variables and regularizes their respective associations with the outcome by shrinking the coefficients such that those left with non-zero coefficients are chosen as the most influential. Those variables that were selected in all imputations were retained for the final multivariable model. The coefficients from the separate imputations were combined using Rubin’s rules to provide a single, global set of coefficients that accounts for the uncertainty of imputation. These global coefficients were used to calculate incidence rate ratios (IRR) of the DAI exposure and the covariates. Because the DAI exposure ranges in percentile values from 0 to 1, it typically results in very small effect sizes. For this reason the DAI was also codified as an indicator of values greater than the sample median relative to those less than or equal to the sample median. The covariate UDI-6 was similarly dichotomized and the IRR and the least square mean values of the median-based subgroups (for DAI and UDI-6) were presented to give both relative and absolute results for the TBQ outcome. Analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team, 2022), RStudio (RStudio Team, 2022), and the glmnet package.37

Mixed Methods Analysis

In a convergent mixed methods design, TG and CKM analyzed DAI categories and responses to the open-ended survey question “Please share with us what has been your greatest challenge in managing medical care for your bladder cancer.” We conducted qualitative template analysis of survey responses.38 After reviewing the survey responses, we determined that TBQ domains represented most of the comments relating to challenges in managing NMIBC. We created a codebook based on the 15 TBQ domains, while allowing for open coding for new themes (Supplemental Table 6). We found that certain codes derived from TBQ survey items required modification for the cancer context. We modified the TBQ survey item of “The taste, shape or size of your tablets, or the annoyances caused by your injections” into a code called “cancer treatments” which included side effects of NMIBC treatment other than urination bother. We split urination bother caused by NMIBC treatments into a separate code because of the high volume of responses that referred to urinary side effects, underscoring importance to participants. The TBQ does not measure emotional burdens and we created a new code called “cancer worry” (Supplemental Table 6).

We coded all survey responses and resolved disagreements through discussion and with the larger study team. We excluded data that focused on positive aspects of care, as our objective was to describe burdens, not mitigators. Survey responses could be coded to more than one code. Analyses were conducted in NVIVO version 12.0 (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia). Quantitative DAI categories were integrated with qualitative survey responses in a joint display demonstrating the frequency of codes by DAI category with illustrative quotes.

RESULTS

Demographics/Patient Characteristics

We enrolled 119 patients with a mean enrollment age of 78.9 years and mean age at NMIBC diagnosis of 75.2 years (Table 1). Consistent with NMIBC demographics, three-quarters of the cohort were males (77.3%) and 89.1% were White.1 Over half had a high school education only (57.1%), one-third noted difficulty paying for basic needs (35.3%), one-third had low health literacy (33.6%), and 45.4% were rural. Mean travel distance to the urology clinic was 29.4 miles and mean travel time was 40 minutes. Patients had a mean of 15 days of healthcare utilization (SD 12) in the year prior to study enrollment. Twenty-three patients (19.3%) received at least one NMIBC treatment within the 3 months prior to enrollment. Of these recently treated patients, 22 had either undergone transurethral resection of bladder tumor or intravesical bladder instillation, one patient had undergone both, and none had received intravenous immunotherapy with pembrolizumab. Because the indicator of recent treatment (≤3 months) did not exhibit a significant unadjusted association (p=0.39) with the outcome, it was not included as a candidate for multivariable model selection.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Enrolled Older Adults with Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC)

| Enrolled(n=119) | |

|---|---|

| Selected Demographics | |

| Age at enrollmentab, years (mean, SD) | 78.9 (7.0) |

| Sexab (n, %) Male Female |

92 (77.3%) 27 (22.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity (n, %) White only American Indian only White and American Indian Does not fully describe me Prefer not to answer Missing |

106 (89.1%) 1 (0.8%) 3 (2.5%) 5 (4.2%) 3 (2.5%) 1 (0.8%) |

| Marital Statusab (n, %) Single Married/Partnered Divorced/Widowed/Other Missing |

8 (6.7%) 83 (69.7%) 26 (42.5%) 2 (1.7%) |

| Education Levelab (n, %) High school College Graduate school |

68 (57.1%) 39 (32.8%) 12 (10.1%) |

| Difficulty paying for the basicsab (n, %) Very hard/Somewhat hard Not hard at all Missing |

42 (35.3%) 76 (63.9%) 1 (0.8%) |

| Health Literacyab (n, %) Low High Missing |

40 (33.6%) 78 (65.5%) 1 (0.8%) |

| Urban-Rural Residenceab (n, %) Urban Rural |

65 (54.6%) 54 (45.4%) |

| Recent NMIBC Treatment (n, %) No Yes |

96 (80.7%) 23 (19.3%) |

| Treatment Burden Questionnaire Scoreab (mean, SD) | 15.8 (15.5) |

| Selected Geriatric Conditions | |

| ADL (n, %) Full function (6) Moderate functional impairment (4) Severe functional impairment (≤2) Missing |

100 (84.0%) 1 (0.8%) 2 (1.7%) 16 (13.4%) |

| ≥2 falls in the last 6 monthsab (n, %) Missing |

10 (8.4%) 9 (7.6%) |

| Multimorbidity (≥2 chronic conditions)ab, yes (n, %) | 104 (87.4%) |

| Weight Loss, yes (n, %) | 27 (22.7%) |

| HADS Depression, yes (n, %)ab Missing |

9 (7.6%) 5 (4.2%) |

| Urogenital Distress Inventory Scoreab (mean, SD) Missing (n, %) |

26.0 (21.8) 1 (0.8%) |

| Timed Up and Go, ≥13 seconds (n, %) Missing |

40 (33.6%) 41 (34.5%) |

| MoCA Scorea (n, %) <26 ≥26 Missing |

30 (25.2%) 7 (5.9%) 82 (68.9%) |

| TICS Scoreab (n, %) <27 ≥27 Missing |

1 (0.8%) 93 (78.2%) 25 (21.0%) |

| DAI Categoriesb (n, %) Robust/Non-Frail (0<0.2) Pre-Frail (0.2<0.35) Frail (≥0.35) |

67 (56.3%) 36 (30.3%) 16 (13.4%) |

Abbreviations: SD=standard deviation; NMIBC=non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; ADL=activities of daily living; HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TICS=Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status; DAI=Deficit Accumulation Index

Variable is included in the multiple imputation. Recorded missingness for a variable is indicated with a “Missing” label. Additional variables used in multiple imputation included: instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), patient-reported Karnofsky Performance Status, HADS Anxiety Score, SF-36 Score, healthcare utilization in the year prior to enrollment, travel time from home to urology office, and NMIBC stage/grade.

Variable is included in the multivariable model for Treatment Burden Questionnaire. The SF-36 Score was also used in the multivariable model.

Multimorbidity was the most common geriatric condition (87.4%, Table 1) with a median of 3 chronic conditions (IQR 2-5). One-quarter (24.4%) had ≥5 prescribed medications (Supplemental Table 1). Almost half noted that their health impacted social activity (48.8%). The majority had full function based on the Katz ADL assessment (84%); however, 33.1% had intermediate or slow Timed Up and Go speeds (≥13 seconds). The majority of recruitment occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and due to the pause on in-person research visits, 68.9% of MoCA scores were missing. Of the 37 MoCA scores collected, 30 (81.1%) were in the cognitive impairment range (<26). Following our transition to TICS, we found lower rates of cognitive impairment with only 1 patient with TICS <27.

There were no significant differences between enrolled and non-enrolled patients (Supplemental Table 3).

TBQ Scores (Primary Outcome)

Mean TBQ score was low (15.8, SD 15.5) and right-skewed (Figure 1a), consistent with prior studies of similar older adults.39 For individual TBQ survey items, financial burden (58%), doctors visits and other appointments (51%), lab tests and exams (51%), and arranging appointments (50%) were the most frequent treatment-related burdens and had the highest mean scores (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 2, and Supplemental Table 4). Two-thirds of participants (66%) responded affirmatively to the global treatment burden question.

Figure 1:

Distributions of a) Treatment Burden Questionnaire Scores (TBQ, Outcome), and b) Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI, Exposure)

Figure 2:

Proportion of Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) Survey Items Reported as a Problem By Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI) Category

DAI (Primary Exposure)

Mean DAI for the cohort was 0.21 (SD 0.12) and the distribution of DAI values was right-skewed (Figure 1b). By DAI category, 56.3% were robust, 30.3% were pre-frail, and 13.4% were frail.

Multivariable Model Results

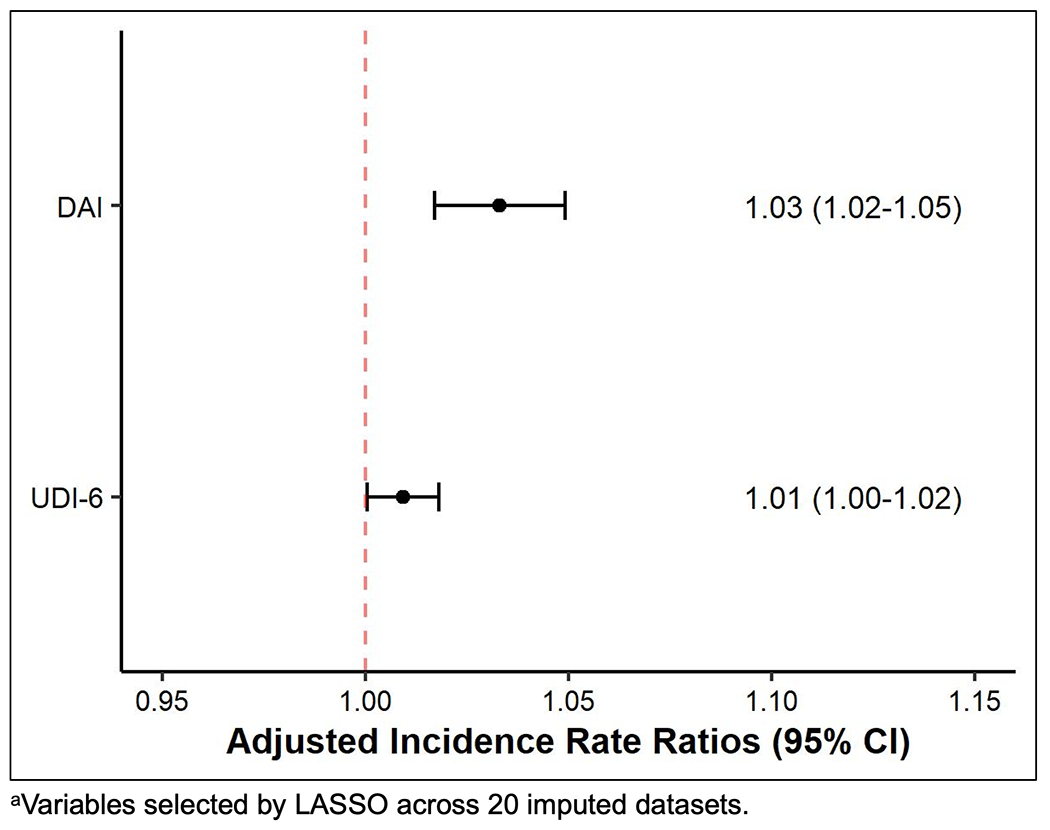

Unadjusted associations of the eighteen explanatory variables considered by LASSO are shown in Supplemental Table 5. For our primary objective, we found that DAI and UDI-6 score were significantly associated with TBQ score in adjusted analyses. Figure 3 shows the results of our adjusted multivariable model with the adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) point estimate (dot) and 95% confidence interval (bars) for the exposures, DAI and UDI-6. For patients in our cohort, for each 0.01 unit increase in DAI (scaled from 0 to 1), on average, the TBQ score increased by 3% (adjusted IRR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02-1.05, Figure 3). This means that as aging-related deficits accumulate, older adults with NMIBC in our cohort reported greater treatment burden. For urinary symptoms, for each 1 unit increase in UDI-6 score, on average, for patients in our cohort, the TBQ score increased by 1% (adjusted IRR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00-1.02). This means that worsening urinary symptoms were associated with greater patient reported-treatment burden for older adults with NMIBC in our cohort.

Figure 3:

Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratios for the Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory-6 (UDI-6) from the Negative Binomial Regression Model of the Treatment Burden Questionnaire Score

Mixed Methods Results: Greatest Challenge Question

Ninety nine participants responded to the greatest challenge question, of whom 43 (43.4%) were frail or pre-frail, and 56 (56.6%) were robust. Pre-frail/frail respondents had higher mean age (80.8 versus 76.7 years) and TBQ score (22.9 versus 10.2) than robust respondents. Approximately one-quarter (27.3%) reported no challenges and described positive relationships with providers, long periods of time without NMIBC recurrence, and limited need for treatment following initial diagnosis and treatment.

The top five most frequent codes were cancer treatments (22.2%), cancer worry (19.2%), urination bother (18.2%), self-management (18.2%), and appointment time (11.1%). Robust respondents mentioned cancer treatment challenges more frequently than frail/pre-frail (30.4% versus 11.6%, Figure 4), and described urinary catheter discomfort and long trips back and forth for treatments. Pre-frail/frail patients reported urination bother more frequently than robust patients (20.9% versus 16.1%), and distress due to nocturia and interrupted sleep. A higher proportion of robust respondents reported emotional burdens due to cancer worry (21.4% versus 16.3%), though all respondents described similar concerns about fear of recurrence, disappointment with recurrences, and worry about losing their bladder.

Figure 4:

Joint Display of Most Common Greatest Challenge Themes by Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI) Category

Self-management burdens were reported by 18.2% of respondents in nearly equal proportions by robust and pre-frail/frail patients (17.9% versus 18.6%). Burdens included urinary catheter management, use of products for urinary leakage, and personal hygiene. Robust respondents noted that lifestyle changes such as dietary modifications and physical activity were burdensome self-management tasks, especially within the context of multimorbidity (Supplemental Table 7).

Respondents highlighted challenges due to arranging appointments and the time spent in appointments. Multiple respondents discussed the difficulties of arranging transportation, relying on others for transportation, healthcare visit frequency, and lengthy travel times with associated costs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that higher geriatric assessment-derived DAI was significantly associated with greater patient-reported treatment burden in older adults with NMIBC. The specific burdens and challenges reported by older adults with NMIBC in our cohort varied by DAI category. Pre-frail and frail older adults reported urinary side effects of NMIBC treatment and overall self-management most frequently as their greatest challenges. In contrast, robust older adults reported NMIBC-specific burdens including the treatments themselves and worry about cancer recurrence and progression, as well as excessive time spent in appointments. We also found that higher UDI-6 scores, a measure of urinary symptom severity, were significantly associated with greater patient-reported treatment burden. Collectively, these findings suggest that as aging-related conditions accumulate in quantity and severity, older adults with NMIBC experience greater burdens related to cancer treatment, side effects, and overall healthcare management.

Of all of the demographic, cancer-specific, and aging-related variables we examined, we found that the DAI, a composite measure of quantity and severity of geriatric conditions, was most significantly associated with patient-reported treatment burden. Our results expand on our prior study from the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database in which we found that functional dependency was associated with higher overall health system contact rate in the year following NMIBC diagnosis.10 Our findings also extend research from SEER-Medicare regarding other malignancies. For example, in older adults with multiple myeloma, performance status and multimorbidity were the most significant predictors of treatment burden as measured by healthcare system contact days in the year following diagnosis.12 Healthcare encounters are only one aspect of treatment burden and exclude home-based work such as medication management and healthcare visit coordination. Our study expands on prior large database work by demonstrating that older adults with cancer and aging-related conditions report a direct experience of higher overall, multi-dimensional treatment burden.

Our qualitative findings may help to explain the quantitative associations between DAI and TBQ scores. Specific treatment burden dimensions varied by DAI category, such as for self-management. For pre-frail/frail older adults, a growing self-management workload may exceed energy levels to perform it or cause more fatigue. For example, in a study of older colorectal cancer survivors, self-management was associated with physical and mental fatigue resulting in higher treatment burden scores.17 However, that study excluded individuals over 80 which may have biased its results towards lower treatment burden.

Robust participants in our study were younger, had lower treatment burden scores, and had emotional burdens specific to cancer treatment and worry. Other studies have also suggested that younger patients with cancer experience depression, anxiety, and cancer worry at higher rates than older patients with cancer. A cross-sectional survey of 1796 bladder cancer patients found that younger participants had the most problems with anxiety and depression.40 Burdens due to cancer treatment and worry were not easily coded to the domains of the TBQ. The TBQ does not capture such emotional burdens and may require modification for the cancer context.

Robust participants also noted burdens due to time spent in appointments. Several studies have shown that younger age is associated with higher patient-perceived burdens related to time toxicity.17 Younger patients may still be employed or have other social obligations and may become frustrated at the amount of time diverted to healthcare activities. Nearly half of our cohort resided in a rural area and traveled long distances for care which exacerbated time burdens. Our findings corroborate multiple studies of the time toxicity of cancer treatment including a study of older adults with advanced lung cancer for whom the frequency of appointments, treatments, and procedures left little time for rest or other activities.9–11,41–43 Though beyond the scope of this paper, we recognize that for frailer older adults, a limiting factor may be the time toxicity experienced by an informal caregiver such as an adult daughter or son with downstream negative effects such as lost pay and excessive time spent on paperwork for compliance with Family and Medical Leave Act policies (FMLA).

We found an association between UDI-6 scores, a measure of urinary symptom severity, and patient-reported treatment burden in older adults with NMIBC. Urinary incontinence and other urinary symptoms (e.g., nocturia) are highly prevalent in both older men and women; however, urinary conditions are not captured by the DAI we used.44,45 NMIBC treatment including resections and intravesical therapies have been associated with urinary incontinence.46 Both our quantitative and qualitative findings highlight how urinary symptoms may be associated with greater treatment burden in pre-frail/frail NMIBC patients who may already have baseline urinary symptoms.47 Our findings emphasize the importance of assessing and managing urinary symptoms in older adults generally and specifically when undergoing treatment for urologic cancer.

Our findings must be considered within certain limitations. Our sample was limited to one health system and a geographic area of the United States and reflects the primarily White and male demographic of bladder cancer.1 However, a strength was that our cohort included rural-dwelling older adults (45%), a high priority population that is underrepresented in both aging and cancer research. Our cohort was underprivileged with lower educational attainment, financial difficulties, and low health literacy. Because we used a convenience sample, we may have missed participants too overburdened to enroll. We attempted to address this by comparing enrolled and declined participants and found no clear differences, though declined participants may have had a greater perception of treatment burden. We also recognize that our sample size was small considering the number of variables considered. However, we specifically selected LASSO modeling which was designed to accommodate a large number of variables even in small sample sizes such as ours. Due to the unintended consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, we experienced multiple limitations, as well as opportunities. The greatest limitation was having to switch from in-clinic to telehealth assessments which likely had an adverse impact on our recruitment. However, the ability to perform certain assessments reliably by telephone may be an unanticipated benefit for future studies and interventions decreasing the amount of time older research participants have to spend in clinic. Our average TBQ scores were low, but similar to what has been previously reported in similar populations.39 There is no clear threshold TBQ score that indicates high burden. Recently, the creators of the TBQ suggested introducing a new item that would indicate at which point treatment becomes unsustainable.48 Finally, we had considerable missingness in certain variables (cognitive screening, Timed Up and Go, labs) due to the COVID-19-associated pause on in-person research visits. Future studies could utilize more specific telephone-based mobility measures such as the SARC-F questionnaire.49 Ultimately, this is a feasibility study with promising findings about the interaction between patient characteristics and treatment burden in cancer.

Our findings may inform future prospective and age-informed interventions and Age-Friendly cancer care.50 Applying current evidence-based guidelines that recommend screening for geriatric conditions prior to starting cancer treatment could help physicians to identify those at risk for treatment burden, even in primarily surgically-managed malignancies such as NMIBC.51 Decision tools like Patient Priorities Care could provide a framework for discussions around goals and preferences to tailor treatment and reduce excessive tests and visits in appropriate patients.39 Supportive care for urinary symptoms such as pelvic floor physical therapy may reduce patient-reported treatment burden, but within consideration of extra visits and self-management associated with such interventions. We studied a unidirectional relationship between geriatric conditions and treatment burden; however, this relationship may, in actuality, function as a bidirectional loop in which excessive treatment burden may exacerbate geriatric conditions and vice versa as described in the Cumulative Complexity Model.2 We plan to evaluate these relationships in greater detail in future work. Our findings may also inform the possibility of enabling older adults, a population for whom travel itself may be burdensome, to participate in our future research via telephone or telehealth.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between geriatric conditions and the direct experience of treatment burden in older adults with cancer. These data highlight the need for a holistic approach that reconciles burdens from aging-related conditions with those resulting from cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: CONSORT Diagram

Supplemental Table 1: Full Characteristics of Enrolled Older Adults with Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC)

Supplemental Figure 2: Proportion of Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) Survey Items Reported as a Problem

Supplemental Table 2: Calculation of Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI)

Supplemental Table 3: Comparison of Enrolled to Non-Enrolled NMIBC Patients

Supplemental Table 4: Treatment Burden Questionnaire Responses

Scores for an Average Enrolled Older Adult with DAI and UDI-6 Scores Above and Below the Median

Supplemental Table 5: Unadjusted Associations Between 18 Explanatory Variables Entered into LASSO Model and Treatment Burden Questionnaire Scores

Supplemental Table 6: Codebook for Greatest Challenge Open-Ended Survey Question Analysis

Supplemental Table 7: Full Joint Display of Frequencies of All Greatest Challenge Codes by DAI Category with Illustrative Respondent Quotes

Supplemental Figure 3: Treatment Burden Questionnaire

Key Points:

Among older adults with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, deficit accumulation and urinary symptoms are associated with higher treatment burden.

Specific burdens and challenges varied between robust and pre-frail/frail participants.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding that treatment burden results from both cancer and aging-related conditions can help care teams better manage the healthcare workload of older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are deeply grateful to the study participants for their enthusiasm and engagement with our team. We are grateful to Research Assistant Erika Campbell for her compassionate approach to patient enrollment during the COVID-19 pandemic. We thank the Geisinger Department of Urology clinic staff and faculty for supporting this study. We are grateful to Dr. Gerda Fillenbaum for guidance on the OARS IADL and Physical Health questionnaires and for permission to use them in our study. We received written permission from Wake Forest University to use the UDI-6 questionnaire.

Funding Sources:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (grant number R03AG064382), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR002014), the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (grant number P30AG021342), and the Duke Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (grant number P30AG028716).

Conflict of Interest:

Matthew E. Nielsen serves as a paid consultant to the American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force and to the American Urological Association. Dr. Nielsen serves as a consultant/advisor to Grand Rounds for which he is paid via stock options. Tullika Garg served as a paid consultant to WebMD in 2020, currently receives research funding from the Flume Catheter Company, LLC, and reports an immediate family member was an employee and a stockholder of DRPLZ through 2021. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Sponsor’s Role:

The funders had no involvement in study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit this article for publication.

Footnotes

Meetings: Portions of this work were presented as a poster at the 2022 Society of Urologic Oncology Annual Meeting in San Diego, California.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: A functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(10):1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreiner N, DiGennaro S, Harwell C, Burant C, Daly B, Douglas S. Treatment burden as a predictor of self-management adherence within the primary care population. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;54:151301. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eton DT, Anderson RT, Cohn WF, et al. Risk factors for poor health-related quality of life in cancer survivors with multiple chronic conditions: exploring the role of treatment burden as a mediator. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:89–99. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S191480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Gruenigen VE, Huang HQ, Beumer JH, et al. Chemotherapy Completion in Elderly Women with Ovarian, Primary Peritoneal or Fallopian Tube Cancer – An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(3):459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, et al. Burden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literature. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2015;18(3):312–324. doi: 10.1111/hex.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flannery MA, Culakova E, Canin BE, Peppone L, Ramsdale E, Mohile SG. Understanding Treatment Tolerability in Older Adults With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. Published online 2021:JCO.21.00195. doi: 10.1200/jco.21.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sav A, McMillan SS, Akosile A. Burden of Treatment among Elderly Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2021;9(5):612. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg T, Johns A, Young AJ, et al. Geriatric conditions and treatment burden following diagnosis of non-muscle- invasive bladder Cancer in older adults: A population-based analysis. J Geriatr Oncol. Published online May 2021:S1879406821001041. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Presley CJ, Soulos PR, Tinetti M, Montori VM, Yu JB, Gross CP. Treatment burden of medicare beneficiaries with stage i non-small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(2):e98–e107. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.014100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mian HS, Fiala MA, Wildes TM. Burden of Treatment Among Older Adults With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(2):e152–e159. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline. J Urol. 2016;196(4):1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg T, Young AJ, Kost KA, et al. Burden of Multiple Chronic Conditions among Patients with Urological Cancer. J Urol. 2018;199(2):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran VT, Harrington M, Montori VM, Barnes C, Wicks P, Ravaud P. Adaptation and validation of the Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) in English using an internet platform. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siddiqui A, Ornstein KA, Ankuda CK. Prevalence of Treatment Burden in the Last Three Years of Life. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(6):879–886. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husebø AML, Dalen I, Richardson A, Bru E, Søreide JA. Factors influencing treatment burden in colorectal cancer patients undergoing curative surgery: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;30(5). doi: 10.1111/ecc.13437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran VT, Montori VM, Eton DT, Baruch D, Falissard B, Ravaud P. Development and description of measurement properties of an instrument to assess treatment burden among patients with multiple chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2012;10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen HJ, Smith D, Sun CL, et al. Frailty as determined by a comprehensive geriatric assessment-derived deficit-accumulation index in older patients with cancer who receive chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(24):3865–3872. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji J, Sun CL, Cohen HJ, Synold T, Muss H, Sedrak MS. Inflammation and Clinical Decline After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Older Adults With Breast Cancer: Results From the Hurria Older Patients Prospective Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(2):307–315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji J, Sun CL, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Bae M, Sedrak MS. Toxicity risk score and clinical decline after adjuvant chemotherapy in older breast cancer survivors. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115(5):578–585. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djad029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandelblatt JS, Zhou X, Small BJ, et al. Deficit Accumulation Frailty Trajectories of Older Breast Cancer Survivors and Non-Cancer Controls: The Thinking and Living With Cancer Study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(8):1053–1064. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerard EJ, Deal AM, Chang Y, et al. Frailty index developed from a cancer-specific geriatric assessment and the association with mortality among older adults with cancer. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15(7):894–902. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: A feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a Geriatric Assessment in Cooperative Group Clinical Cancer Trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1290–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohannon RW. Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2001. 2006;29(2):64–68. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200608000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dodson JA, Hajduk AM, Murphy TE, et al. Thirty-Day Readmission Risk Model for Older Adults Hospitalized With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(5):e005320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips NA, Chertkow H, Pichora-Fuller MK, Wittich W. Special Issues on Using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for telemedicine Assessment During COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):942–944. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK, Andrew Fantl J. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: The incontinence impact questionnaire and the urogenital distress inventory. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14(2):131–139. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Utomo E, Korfage IJ, Wildhagen MF, Steensma AB, Bangma CH, Blok BFM. Validation of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7) in a Dutch population. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(1):24–31. doi: 10.1002/nau.22496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: Screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall MH, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, et al. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: The SWAN sleep study. Sleep. 2009;32(1):73–82. doi: 10.5665/sleep/32.1.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33(1). doi: 10.18637/jss.v033.i01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202–222. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of Patient Priorities-Aligned Decision-Making with Patient Outcomes and Ambulatory Health Care Burden among Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688–1697. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Catto JWF, Downing A, Mason S, et al. Quality of Life After Bladder Cancer: A Cross-sectional Survey of Patient-reported Outcomes. Eur Urol. 2021;79(5):621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lippiett KA, Richardson A, Myall M, Cummings A, May CR. Patients and informal caregivers’ experiences of burden of treatment in lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e020515. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta A, O’Callaghan CJ, Zhu L, et al. Evaluating the Time Toxicity of Cancer Treatment in the CCTG CO.17 Trial. JCO Oncol Pract. Published online March 7, 2023. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rocque GB, Williams CP, Ingram SA, et al. Health care-related time costs in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2020;(August):1–9. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao C, Zhang C, Sriskandarajah C, et al. Trends and Racial Disparities in the Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence Among Men in the USA, 2001-2020. Eur Urol Focus. 2022;8(6):1758–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2022.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee UJ, Feinstein L, Ward JB, et al. Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence among a Nationally Representative Sample of Women, 2005-2016: Findings from the Urologic Diseases in America Project. J Urol. 2021;205(6):1718–1724. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brisbane WG, Holt SK, Winters BR, et al. Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Influences Physical Health Related Quality of Life and Urinary Incontinence. Urology. 2019;125:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauer SR, Scherzer R, Suskind AM, et al. Co-Occurrenceof Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Frailty among Community-DwellingOlder Men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;189(1):S93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tran VT, Montori VM, Ravaud P. Is My Patient Overwhelmed? Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(3):504–512. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: A Simple Questionnaire to Rapidly Diagnose Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):531–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vonnes C, Mason TM. Crafting age friendly cancer care: A model for improvement utilizing the 4Ms framework across the continuum of an NCI-designated Cancer Center. J Geriatr Oncol 2021;12(1):152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dale W, Klepin HD, Williams GR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic Cancer Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. Published online July 17, 2023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: CONSORT Diagram

Supplemental Table 1: Full Characteristics of Enrolled Older Adults with Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC)

Supplemental Figure 2: Proportion of Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) Survey Items Reported as a Problem

Supplemental Table 2: Calculation of Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI)

Supplemental Table 3: Comparison of Enrolled to Non-Enrolled NMIBC Patients

Supplemental Table 4: Treatment Burden Questionnaire Responses

Scores for an Average Enrolled Older Adult with DAI and UDI-6 Scores Above and Below the Median

Supplemental Table 5: Unadjusted Associations Between 18 Explanatory Variables Entered into LASSO Model and Treatment Burden Questionnaire Scores

Supplemental Table 6: Codebook for Greatest Challenge Open-Ended Survey Question Analysis

Supplemental Table 7: Full Joint Display of Frequencies of All Greatest Challenge Codes by DAI Category with Illustrative Respondent Quotes

Supplemental Figure 3: Treatment Burden Questionnaire