Abstract

Introduction:

Guidelines suggest a single screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in patients with multiple risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus (BE). We aimed to determine BE prevalence and predictors on repeat EGD after a negative initial EGD, using two large national databases (GI Quality Improvement Consortium [GIQuIC] and TriNetX).

Methods:

Patients who underwent at least 2 EGDs were included and those with BE or esophageal adenocarcinoma detected at initial EGD were excluded. Patient demographics and prevalence of BE on repeat EGD were collected. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess for independent risk factors for BE detected on the repeat EGD.

Results:

In 214,318 and 153,445 patients undergoing at least 2 EGDs over a median follow-up of 28-35 months, the prevalence of BE on repeat EGD was 1.7% in GIQuIC and 3.4% in TriNetX respectively (26-45% of baseline BE prevalence). Most (89%) patients had non-dysplastic BE. The prevalence of BE remained stable over time (from 1 to >5 years from negative initial EGD) but increased with increasing number of risk factors. BE prevalence in a high-risk population (GERD + ≥1 risk factor for BE) was 3-4%.

Discussion:

In this study of >350,000 patients, rates of BE on repeat EGD ranged from 1.7-3.4%, and were higher in those with multiple risk factors. Most were likely missed at initial evaluation, underscoring the importance of a high-quality initial endoscopic examination. While routine repeat endoscopic BE screening after a negative initial examination, is not recommended, repeat screening may be considered in carefully selected patients with GERD and ≥ 2 risk factors for BE, potentially using non-endoscopic tools.

INTRODUCTION

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), the predominant form of esophageal cancer in the United States, with increasing incidence over the past several decades.[1-4] EAC continues to have dismal outcomes with 5-year survival rates <20%.[5] Therefore, national guidelines recommend screening for BE in individuals with multiple risk factors and endoscopic surveillance in patients with BE to detect dysplasia and early-stage EAC.[6-10] Despite these recommendations, only 7-10% of all incident EACs are currently identified in surveillance suggesting that many at-risk patients are not being adequately identified [11].

Current guidelines recommend a one-time screening endoscopy for BE in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and other risk factors (age >50 years, family history of BE/EAC, central obesity, male sex, white race, and tobacco use).[12] Repeat screening after a negative screening endoscopy for BE is currently not endorsed largely based on two studies that examined the incidence of BE on a second endoscopy albeit with notable limitations, including small sample size and limited follow-up after two years.[13,14] The duration for development of BE is uncertain, and a single endoscopy may not rule out missed or true incident BE, especially if the initial evaluation occurs before age 50 years and the patient acquires additional risk factors like obesity, reflux symptoms, or smoking over time.

Given high costs and perceived low-yield of repeat endoscopy after a negative initial examination for BE, it is generally not recommended except in severe erosive esophagitis where BE prevalence on follow-up is higher (up to 27%).[15, 16] Recent advancements in non-endoscopic BE detection tools using swallowable cell collection devices and biomarkers have shown excellent performance when compared to the criterion standard of endoscopy.[17-19] With development of these minimally invasive, low-cost tools and the possibility of missed or incident BE, consideration of repeat evaluation in select patients with a negative initial endoscopic examination has gained renewed relevance.

The study aims were: a) To determine the prevalence of BE and b) to identify predictors of BE on repeat endoscopy after negative initial examination. We first assessed this using the GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQuIC), a national benchmarking registry, and subsequently validated outcomes in the TriNetX Research Network, a national health record network.

METHODS

We analyzed data from two large national databases, GIQuIC and TriNetX.[20-23] Additional details on these databases can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥18 years who underwent at least 2 EGDs were included. Patients with BE/EAC present on first EGD were excluded. Patients who underwent repeat EGD for BE surveillance, surveillance after BE eradication, endoscopic therapy of BE, or palliation of stenosing neoplasm were also excluded.

Definition of BE and GERD

Given inherent differences in the two databases, there were some differences in how BE and GERD were defined for each database. In GIQuIC, BE diagnosis required both supportive endoscopic and pathology findings. In TriNetX, since data on pathology is not directly available, BE diagnosis was based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes (Supplementary Table 1). In GIQuIC, GERD was defined using a procedure indication of “esophageal reflux symptoms that persist or recur despite appropriate therapy”, or documentation in the “other” indication field of “reflux”, “GERD”, “heartburn”, or “k21.9” (ICD code for GERD). In TriNetX, GERD was defined using pertinent ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes (Supplementary Table 1).

Definition of BE

The GIQuIC data collection form includes a specific question on the presence of BE as follows: “Was BE confirmed by pathology on the current exam?” This information is entered by the performing endoscopist or their staff after pathology results have returned. Hence in the GIQuIC database, BE was diagnosed when both endoscopic and pathology findings were consistent with BE. In contrast, in TriNetX, diagnosis of BE in TriNetX was based using the ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes in the electronic medical record (Supplementary Table 1). To increase specificity of BE diagnosis, we only included patients with an ICD diagnosis code of BE who also had a CPT code for EGD within 90 days prior to the BE diagnosis code (Supplementary Table 1). We also performed additional analyses in TriNetX to determine the presence of BE on subsequent endoscopies to minimize coding issues that could be generating false positive BE diagnoses.

Study Outcomes:

Primary outcomes

Age, sex, and race stratified prevalence of BE on repeat endoscopy after a negative initial examination,

Predictors of BE on repeat endoscopy after negative initial examination in the GIQuIC registry and TriNetX network.

Secondary Outcomes

Prevalence of BE on repeat EGD in a high-risk population defined as the presence of GERD symptoms and at least one additional risk factor for BE

Prevalence and predictors of BE diagnosed at ≥1 year time interval between initial and subsequent EGD.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of BE on repeat EGD was stratified by age, sex, race, and GERD status. Subgroup analysis was performed in patients that had repeat EGD ≥1 year after negative initial EGD. Repeat EGD was classified by years following negative initial EGD in groups (i.e., <1 year, 1-3 years, 3-5 years, and >5 years), and the yield of BE was tabulated for each stratum. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between each variable of interest and the outcome of BE on repeat examination. Those independent variables considered a priori to be clinically relevant, or those with a p-value <0.2 resulting from the univariate analyses, were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. A priori, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant in the final multivariate model. The GIQUIC and the TriNetX data analysis was conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 and R version 4.2, respectively.

RESULTS

Prevalence of BE on repeat EGD after negative initial EGD

GIQuIC Registry

The prevalence of BE and EAC on initial EGD in GIQuIC was 3.8% and 0.11%, respectively. The GIQuIC registry contained data on 2,614,643 patients who underwent at least one EGD, of which 214,318 (8.2%) patients met inclusion (had at least two EGDs with the initial EGD negative for BE/EAC) with a median (interquartile range [IQR]) 2 (2, 2) EGDs after the first negative EGD. These patients underwent repeat EGD after median (IQR) 12.7 (3, 29) months from the negative initial EGD. The indications for repeat EGD (Table 1) most commonly included reflux (n=75,281), dysphagia (n=72,908), and gastrointestinal bleeding/anemia (n=43,638). A total of 3,727 patients (1.7%) had BE/EAC on repeat EGD with 54% men, 90% Caucasians, and 59% with GERD symptoms. BE length was available for 2,077 patients and the median (IQR) BE length was 2 (1, 2) cm; only 15.7% (n=326) patients had long-segment BE. Most patients had NDBE (n=3,276, 88%) with the remaining showing variable dysplasia grades (BE-IND: n=69, 1.8%; BE-LGD: n=29, 0.7%; BE-HGD: n=22; 0.6%) or EAC (n=26, 0.7%) (unknown 8%).

Table 1:

Prevalence of BE on repeat endoscopy after a negative initial endoscopy stratified by indication for follow-up EGD.

| GIQuIC | TriNetX | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indications# | Total N=214,318 |

No BE N = 210,591 |

BE present N = 3,727 |

p-value | Total N=153,445 |

No BE N =148,123 |

BE present N = 5,322 |

p-value |

| Screening for BE | 2,180 | 2,004 (91.9%) |

176 (8.1%) |

<0.01 | 3,394 | 3,349 (98.7%) |

45 (1.3%) |

<0.01 |

| Reflux | 75,281 | 73,085 (97.1%) |

2,196 (2.9%) |

<0.01 | 86,976 | 83,002 (95.4%) |

3,974 (4.6%) |

<0.01 |

| Ulcer | 22,425 | 22,036 (98.2%) |

389 (1.8%) |

0.95 | 2 | 2 (100.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0.99 |

| Weight loss | 4,646 | 4,605 (98.9%) |

41 (1.1%) |

<0.01 | 8,070 | 7,875 (97.6%) |

195 (2.4%) |

<0.01 |

| Dysphagia | 72,908 | 72,006 (98.8%) |

902 (1.2%) |

<0.01 | 3,096 | 2,912 (95.1%) |

184 (4.9%) |

<0.01 |

| Esophagitis | 18,195 | 17,341 (95.3%) |

854 (4.7%) |

<0.01 | 250 | 228 (91.2%) |

22 (8.8%) |

<0.01 |

| GI bleeding / anemia | 43,638 | 43,238 (99.1%) |

400 (0.9%) |

<0.01 | 24,315 | 23,983 (98.6%) |

332 (1.4%) |

<0.01 |

| Vomiting | 12,012 | 11,867 (98.8%) |

145 (1.2%) |

<0.01 | 12,005 | 11,780 (98.1%) |

225 (1.9%) |

<0.01 |

| Others | 22,740 | 22,431 (98.6%) |

309 (1.4%) |

<0.01 | 30,836 | 30,129 (97.7%) |

707 (2.3%) |

<0.01 |

Indications are not mutually exclusive (i.e., a single patient could have multiple indications for EGD and appear in multiple categories).

TriNetX Network

The prevalence of BE/EAC on initial EGD in TriNetX was 13.0%. TriNetX contained data on 2,211,097 patients who underwent at least one EGD, of which 153,445 (6.9%) had at least 2 EGDs with the initial EGD being negative for BE/EAC and repeat EGD was performed after median (IQR) 13.5 (2.6, 37.1) months. The indications for repeat EGD (Table 1) most commonly included reflux (n=86,976), gastrointestinal bleeding/anemia (n=24,315), and dysphagia (n=3,096). A total of 5,322 patients (3.4%) had BE/EAC on repeat EGD with 51% men, 80% Caucasians, and 89% with GERD symptoms. Notably, 87% of those with BE on repeat EGD continued to display a BE diagnosis code on subsequent encounters. Most patients had NDBE (n=4,732, 89%) with the remaining showing variable dysplasia (BE-LGD: n=30, 0.5%; BE-HGD: n=23; 0.4%) or EAC (n=452, 8.4%) (unknown 1.6%).

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 shows the prevalence of BE stratified by age, gender, race, time interval between initial and subsequent EGD, and risk factors across the two databases. Patients in the 50-80 years age group had the highest prevalence of BE in GIQuIC (2%) and TriNetX (4%) on repeat EGD. Almost half of BE cases were diagnosed within 1 year of negative initial EGD in both databases (GIQuIC: 56%; TriNetX: 41%). The prevalence remained similar across all time intervals between EGDs as follows: 1-3 years (GIQuIC: 2%; TriNetX: 4%), 3-5 years (GIQuIC: 2%; TriNetX: 4%), >5 years (GIQuIC: 1%; TriNetX: 4%) (Figure 1). Approximately 60% and 74% of BE cases had GERD symptoms as the primary indication for repeat EGD in GIQuIC and TriNetX, respectively. The prevalence based on indication for repeat EGD is shown in Table 1. The highest prevalence of BE was observed in patients with esophagitis as an indication (GIQuIC: 4.7%; TriNetX:8.8%), followed by reflux (GIQuIC: 2.9%; TriNetX: 4.6%), dysphagia (GIQuIC: 1.2%; TriNetX:4.9%), and weight loss (GIQuIC: 1.1%; TriNetX: 2.4%).

Table 2:

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without BE on follow-up EGD after negative initial EGD.

| GIQuIC | TriNetX | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total N= 214,318 |

No BE N = 210,591 |

BE present N = 3,727 |

p-value | Total N=153,445 |

No BE N =148,123 |

BE present N = 5,322 |

p- value |

| Age (years) | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| <50 | 47,643 (22.2%) | 47,029 (22.3%) | 614 (16.5%) | 45,479 (30.7%) | 44,248 (31.0%) | 1,231 (24.0%) | ||

| 50-80 | 151,896 (70.9%) | 148,953 (70.7%) | 2,943 (79.0%) | 96,001 (64.8%) | 92,256 (64.5%) | 3,745 (73.1%) | ||

| >80 | 14,779 (6.9%) | 14,609 (6.9%) | 170 (4.6%) | 6,592 (4.5%) | 6,445 (4.5%) | 147 (2.9%) | ||

| Male sex | 83,903 (39.1%) | 81,909 (38.9%) | 1,994 (53.5%) | <0.01 | 61,269 (39.9%) | 58,572 (39.5%) | 2,697 (50.7%) | <0.01 |

| White race * | 145,918 (82.2%) | 143,211 (82.1%) | 2,707 (89.8%) | <0.01 | 109,018 (71.0%) | 104,751 (70.7%) | 4,267 (80.2%) | <0.01 |

| GERD symptoms | 75,281 (35.1%) | 73,085 (34.7%) | 2,196 (58.9%) | <0.01 | 119,213 (77.7%) | 114,456 (77.3%) | 4,757 (89.4%) | <0.01 |

| Smoking (ever) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 26,821 (17.5%) | 26,073 (17.6%) | 748 (14.1%) | <0.01 | |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 13,804 (36.0%) | 13,421 (35.9%) | 383 (37.4%) | 0.31 | 26,963 (38.9%) | 25,989 (38.8%) | 974 (40.3%) | 0.16 |

| Time interval between initial negative EGD and subsequent EGD | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| <1 year | 104,366 (48.7%) | 102,284 (48.6%) | 2,082 (55.9%) | 72,793 (47.4%) | 70,603 (47.7%) | 2,190 (41.1%) | ||

| 1-3 years | 73,034 (34.1%) | 71,922 (34.2%) | 1,112 (29.8%) | 41,542 (27.1%) | 39,845 (26.9%) | 1,697 (31.9%) | ||

| 3-5 years | 29,387 (13.7%) | 28,954 (13.7%) | 433 (11.6%) | 19,416 (12.7%) | 18,726 (12.6%) | 690 (13.0%) | ||

| ≥ 5 years | 7,531 (3.5%) | 7,431 (3.5%) | 100 (2.7%) | 19,694 (12.8%) | 18,949 (12.8%) | 745 (14.0%) | ||

| High risk population (GERD + ≥1 risk factor) | 73,831 (34.4%) | 71,655 (34.0%) | 2,176 (58.4%) | <0.01 | 116,423 (75.9%) | 111,710 (75.4%) | 4,713 (88.6%) | <0.01 |

Selection of white race could be accompanied with selection of 1 or more other races, and/or Hispanic ethnicity.

Figure 1:

The prevalence of BE by time interval after negative initial EGD for BE in GIQuIC and TriNetX.

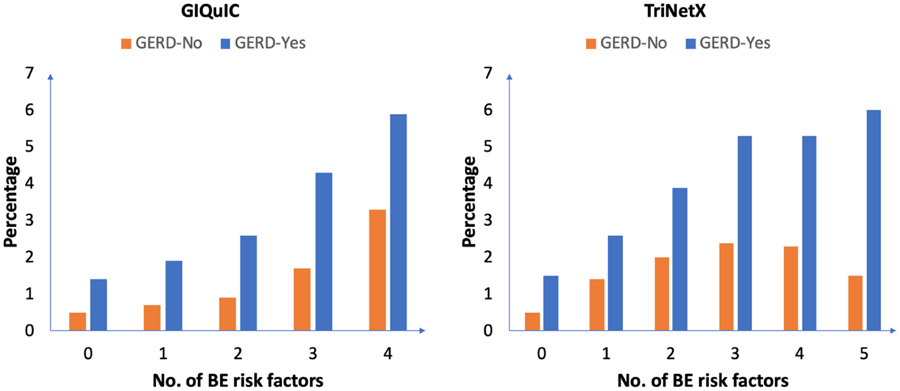

Prevalence of BE based on GERD and number of risk factors

The cohort was further subdivided into two groups: patients with GERD at time of repeat EGD (GIQuIC: n=75,281, 35%, TriNetX: n=119,213, 78%) and without GERD (GIQuIC: n=139,037, 65%; TriNetX: n=34,232, 22%). In the GERD group, the prevalence of BE on repeat EGD was 2.9% and 3.9% in GIQuIC and TriNetX, respectively. In contrast, the prevalence of BE in the non-GERD population was lower (GIQuIC 1.1%; TriNetX 1.7%; p<0.01). The prevalence of BE on repeat EGD in a high-risk population defined as GERD and at least one additional risk factor (based on society guidelines)[24] was 3% (n=2,176) in GIQuIC and 4% (n=4,713) in TriNetX. The high-risk group accounted for almost 60% and 89% of the total diagnosed BE cases on repeat EGD in GIQuIC and TriNetX, respectively. The prevalence of BE also increased with increasing number of risk factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

The prevalence of BE based on the number of risk factors present stratified by GERD status.

BE on repeat EGD with ≥1 year time interval between initial and subsequent EGD

Predictors for BE after negative initial EGD

Independent risk factors associated with BE on repeat EGD included a diagnosis of GERD, male sex, White race, and age 50-80 years in both databases (Table 3).

Table 3:

Predictors for BE on follow-up EGD after negative initial EGD for BE.

| Characteristics | GIQuIC | TriNetX | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

p-value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

p-value | |

| Age | ||||

| <50 | REF | REF | ||

| 50-80 | 1.65 (1.51-1.80) | <0.01 | 1.41 (1.28-1.56) | <0.01 |

| >80 | 1.17 (0.98-1.39) | 0.077 | 0.85 (0.66-1.10) | 0.2 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | REF | REF | ||

| Male | 1.89 (1.68-1.92) | <0.01 | 1.73 (1.59-1.88) | <0.01 |

| Race | ||||

| Other | REF | REF | ||

| White | 1.86 (1.65-2.10) | <0.01 | 1.68 (1.51-1.89) | <0.01 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| No | NA | REF | ||

| Yes | 0.71 (0.63-0.80) | <0.01 | ||

| GERD | ||||

| No | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | <0.01 | 2.23 (1.93-2.59) | <0.01 | |

| Hiatal Hernia | ||||

| No | NA | REF | ||

| Yes | NA | 1.07 (0.97-1.12) | <0.01 | |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | ||||

| No | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | 1.06 (0.93-1.21) | NS | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | 0.5 |

| Time between EGD1 and EGD2 | ||||

| <1 year | 1.59 (1.47-1.71) | <0.01 | REF | |

| 1-3 years | REF | 1.34 (1.20, 1.49) | <0.01 | |

| 3-5 years | 0.89 (0.80-1.00) | 0.04 | 1.29 (1.13, 1.46) | <0.01 |

| >5 years | 0.80 (0.65-0.99) | 0.03 | 1.41 (1.25, 1.58) | <0 .01 |

| Proceduralist | NA | NA | ||

| Gastroenterologist | REF | |||

| Non-gastroenterologist | 1.10 (0.97-1.25) | 0.14 | ||

DISCUSSION

BE prevalence on repeat EGD after a negative initial EGD using data from two large national databases encompassing over 350,000 patients varied from 1.7-3.4%. In other words, the yield of BE on repeat EGD ranged from 26% (TriNetX, 3.4% vs. 13.0%) to 45% (GIQuIC, 1.7% vs. 3.8%) of the baseline prevalence. Rates were higher in those with GERD and at least 1 additional risk factor and predictors included known risk factors. Results were similar in patients undergoing endoscopy >1 year after the initial negative endoscopy. Given that the BE prevalence remained stable over time after initial EGD in both databases, it is probable that most cases reflect BE ‘missed’ on initial endoscopy as opposed to true ‘incident’ BE.

Our study findings are somewhat comparable to two prior smaller studies,[13,14]. The Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) database study, which included 24,406 patients, reported a BE prevalence of 2.3% on repeat EGD .[13] In this study, BE was more common in patients with GERD as an indication for endoscopy (5% vs 1.6%). Similarly, we found that BE prevalence was higher in patients with GERD than without GERD (2.9-3.9% vs. 1.1-1.6%). However, unlike our study which used both endoscopy and histology data to define BE (GIQuIC), the CORI study defined BE using endoscopic findings only. A second study of 2,701 Turkish patients found that only 0.7% patients had BE on repeat EGD.[14] Both studies were limited by a relatively small sample size and only minority of patients had follow-up past 2 years. Given the substantially larger sample size and longer follow-up in our study, we were able to assess BE rates on repeat EGD over longer time intervals (<1, 1-3, 3-5, and >5 years after initial EGD) with a substantial number of patients in each interval (Figure 1).

Our observation that these rates were fairly consistent over time (even 5 years and beyond the initial endoscopy) suggests the majority of BE cases on repeat EGD were likely missed (prevalent) rather than truly incident cases (Figure 1). With incident BE, we would expect that each of the time intervals would have increasing proportions of BE reflecting the sum of the missed prevalent BE cases (which would be constant in magnitude) as well as increasing incidence of incident BE (increasing in time intervals farther away from the initial EGD). A high-quality endoscopic examination is essential in decreasing chances of missed BE and should include assessment of the “5 L’s”: landmarks, length, look, lesions, and levels.[25] Landmark identification includes noting the location of the squamo-columnar junction, the gastroesophageal junction, and diaphragmatic hiatus. The BE length should be documented using the Prague criteria. When looking for lesions, using a distal attachment cap, cleaning the mucosal surface, examining with both white light and narrow band imaging, and spending adequate time to inspect the BE segment can be helpful.[26] When lesions are present, performing targeted biopsies or resecting any focal lesions is critical in addition to sampling with the Seattle protocol).

Our study highlights that BE prevalence increased with increasing number of risk factors, consistent with BE prevalence estimates on initial screening EGD.[27] In patients with ≥2 risk factors, the prevalence of BE was two-fold higher than the overall prevalence on repeat EGD. Furthermore, the prevalence was higher in patients with GERD than without GERD. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that repeat endoscopic screening in White men with GERD symptoms (at age 45 and 60 years) was cost-effective, enabling the detection of both missed prevalent and de novo incident cases.[29] Repeat screening of even 20% of the at-risk population could prevent an additional 11% of EAC deaths compared with one-time screening, whereas repeat screening of 100% of the at-risk population would prevent an additional 21% of EAC deaths.

Given our findings, it is likely that the most cost-effective strategy to decreasing missed BE is a high quality index examination. An alternative strategy is a second screening exam following the first negative study, in high-risk subgroups. The advent of cost-effective and minimally invasive BE detection tests may build a case for a one-time repeat non-endoscopic screening in patients with multiple risk factors (GERD + >1 risk factor), though this has yet to be studied. In a comparative cost effectiveness study of non-endoscopic approaches for BE screening, capsule sponge + biomarker strategies were more cost-effective than sedated endoscopy.[29] The possibility of false negative results does exist with these non-endoscopic techniques. As such, a one-time repeat evaluation 3-5 years after an initial negative evaluation could be considered in those with multiple risk factors. This has to be balanced with the finding that most patients appear to have short-segment, non-dysplastic BE on repeat EGD, and are presumably at low-risk of progression to EAC. A similar predicate exists in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening where repeat testing with stool-based tests is recommended 1-3 years after initial negative testing and is cost effective.[30-32]

Our study has strengths and limitations. We used data from two large national databases, including 367,763 individuals with longer follow-up intervals, to study BE prevalence rates after an initial negative EGD. While the prevalence estimates varied, results overall were largely consistent between the two databases. A particular strength of GIQuIC is the utilization of both endoscopy and pathology data to confirm BE diagnosis. In contrast, in TriNetX the definition of BE is limited to endoscopy and histologic codes only. This difference may account for the higher BE prevalence rates in TriNetX, as some patients may not have had true BE raising the potential for coding errors overestimating the rates of BE. A recent VA study reported many individuals (76.6%) diagnosed with BE solely based on ICD codes did not actually meet BE diagnostic criteria on manual review of medical records.[33] Conversely, the potential for a significant coding error in TriNetX appears limited as 87% of patients diagnosed with BE on repeat endoscopy had a continued BE diagnosis on follow-up encounters. While it is possible that some patients may have had repeat endoscopies at a non-GIQuIC or TriNetX site, we anticipate these numbers to be overall small. GIQuIC has recently added EAC to their data collection form (since 2019). Since only 50% of participating centers have adopted this new collection form, it is possible that EAC on repeat EGD may be under-reported in our study. As GIQuIC collects very limited data on non-BE outcomes such as severe esophagitis, it is possible that prevalent BE may be over-reported on repeat endoscopy as this may reflect the follow-up examination after prior LA grade C-D esophagitis and treatment with potent acid suppression. To mitigate this, we performed a sub-group analysis on patients with at least 1-year interval between two endoscopies (to exclude endoscopy done for the follow-up of esophagitis) and showed that the prevalence remained similar. The potential of a selection bias (in terms of patients undergoing a second endoscopy compared to those only undergoing a single examination) also cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, the prevalence of BE on repeat EGD following a negative EGD is approximately 25-50% of BE prevalence at initial evaluation, but higher in those with multiple risk factors. BE prevalence appeared consistent across different time intervals between initial and repeat EGD, suggesting missed prevalent BE rather than incident BE and underscoring the importance of a high-quality examination at initial endoscopy. In selected patients with multiple BE risk factors, a one-time repeat evaluation could be considered, although more data on cost-effectiveness is needed. While repeat endoscopic screening may be expensive, the development of low-cost, minimally invasive, non-endoscopic BE detection tools may make this approach more feasible in the future. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the prevalence of BE at prolonged intervals after negative initial endoscopy.

Supplementary Material

Table 4:

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without BE on follow-up EGD at least one year after negative initial EGD.

| GIQuIC | TriNetX Network | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total N=109,952 |

No BE N=108,307 |

BE present N =1,645 |

p-value | Total N=80,652 |

No BE N = 77,520 |

BE present N = 3,132 |

p-value |

| Age | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| <50 | 21,752 (19.8%) |

21,524 (19.9%) |

228 (13.9%) |

23,670 (29.3%) |

22,953 (30.7%) |

717 (23.8%) |

||

| 50-80 | 81,575 (74.2%) |

80,245 (74.1%) |

1,330 (80.9%) |

3,198 (3.9%) |

3,111 (4.0%) |

87 (2.9%) |

||

| >80 | 6,625 (6.0%) |

6,538 (6.0%) |

87 (5.3%) |

3,198 (4.0%) |

3,111 (4.0%) |

87 (2.9%) |

||

| Male | 36,811 (33.5%) |

36,075 (33.3%) |

736 (44.7%) |

<0.01 | 27,783 (34.4%) |

26,333 (34.0%) |

1,450 (46.3%) |

<0.01 |

| White * | 76,448 (82.3%) |

75,240 (82.2%) |

1,208 (89.0%) |

<0.01 | 58,132 (72.1%) |

55,570 (71.7%) |

2,562 (81.8%) |

<0.01 |

| GERD | 49,641 (45.1%) |

48,623 (44.9%) |

1,018 (61.9%) |

<0.01 | 68,913 (85.4%) |

66,005 (85.1%) |

2,908 (92.8%) |

<0.01 |

| Tobacco_abuse | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13,951 (17.3%) |

13,534 (17.5%) |

417 (13.3%) |

<0.01 |

|

Obese (BMI >

30) |

7,731 (36.5%) |

7,531 (36.5%) |

200 (37.2%) |

0.72 | 17,506 (41.1%) |

16,796 (41.1%) |

710 (42.4%) |

0.280 |

| Time interval between EGD | 0.38 | <0.01 | ||||||

| 1-3 years | 73,034 (66.4%) |

71,922 (66.4%) |

1,112 (67.6%) |

41,542 (51.5%) |

39,845 (51.4%) |

1,697 (54.2%) |

||

| 3-5 years | 29,387 (26.7%) |

28,954 (26.7%) |

433 (26.3%) |

19,416 (24.1%) |

18,726 (24.2%) |

690 (22.0%) |

||

| ≥5 years | 7,531 (6.8%) |

7,431 (6.9%) |

100 (6.1%) |

19,694 (24.4%) |

18,949 (24.4%) |

745 (23.8%) |

||

| High risk population (GERD + ≥1 risk factor) | 48,831 (44.4%) |

47,821 (44.2%) |

1,010 (61.4%) |

<0.01 | 67,386 (83.6%) |

64,501 (83.2%) |

2,885 (92.1%) |

<0.01 |

Selection of white race could be accompanied with selection of 1 or more other races, and/or Hispanic ethnicity.

What You Need To Know.

Background:

Current guidelines recommend a one-time screening EGD in patients with multiple risk factors for BE. Studies reporting low BE risk after a negative initial EGD are limited by small sample size and short follow-up. We aimed to determine BE prevalence on repeat EGD using two large national databases.

Findings:

In this study with >350,000 patients, rates of BE on repeat EGD after negative initial EGD ranged from 1.7-3.4% (26-45% of the baseline prevalence rates in the two databases). BE prevalence in a high-risk population (GERD + ≥1 risk factor for BE) was 3-4%.

Implications for patient care:

A high-quality initial endoscopic examination is important to reduce the probability of missed BE. While routine repeat endoscopic BE screening is not recommended, repeat screening may be considered in carefully selected patients with GERD and ≥ 2 risk factors, potentially using non-endoscopic tools.

Acknowledgment

This publication was made possible through the support of the Clinical Research Center of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UHCMC) and the Case Western Reserve University Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative (CTSC) 4UL1TR000439. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of UHCMC or NIH.

Funding:

Supported in part by the ACG Medical Resident Research Award (to LKD and PGI), NIH RO1 grant (CA 241164 to PGI and JBK) and The Freeman Foundation

Abbreviations:

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- NDBE

non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus

- LGD

low-grade dysplasia

- HGD

high-grade dysplasia

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- EGD

Endoscopy

- GIQuIC

GI Quality Improvement Consortium Registry

- IQR

interquartile range

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

Lovekirat Dhaliwal: None

Amrit K. Kamboj: None

Lucas Williams: None

Apoorva K. Chandar: None

Karan Sachdeva: None

Erin Gibbons: None

Ramona Lansing: None

Melissa Passe: None

Jamie A. Perez: None

Katelin LR Avenir: None

Scott A. Martin: None

Cadman Leggett: Consulting: Verily Life Sciences

Amitabh Chak: NIH/NCI – U54 CA163060, P50 CA150964, Founder and equity holder in Lucid Diagnostics.

Gary Falk: Research funding: Castle Bioscience, Lucid. Consulting: Castle Bioscience, CDx, Exact Sciences, Lucid

Sachin Wani: Research funding from Lucid Medical, Ambu and CDx Diagnostics. He is a consultant for, Exact Sciences and Castle Biosciences. Supported by NIH/NIDDK— U01DK129191

Nicholas J. Shaheen: Research funding: Pentax, Lucid, Medtronic, Steris, GIE, Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Consulting: Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Castle Biosciences, Aqua Medical

John Kisiel: Inventor of Mayo Clinic intellectual property in the field of Barrett’s esophagus, licensed to Exact Sciences, from which royalties may be paid to Mayo Clinic

Prasad G. Iyer: Research funding from Exact Sciences, Medtronic, Pentax Medical; Consulting: Pentax Medical, CSA Medical, Medtronic, CDx Medical, Castle Biosciences

References

- 1).Cameron A, Ott B, Payne W. The incidence of adenocarcinoma in columnar-lined (Barrett's) esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:857–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Holmes RS, Vaughan TL. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of esophageal cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Pohl H, Sirovich B, Welch HG. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence:Are we reaching the peak?. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1468–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2019. Cancer J Clin 2019; 69: pp. 7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Hur C, Miller M, Kong CY, et al. : Trends in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality. Cancer 2013; 119: pp. 1149–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111(1):30–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90(3):335–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).American Gastroenterological Association Spechler SJ, Sharma P, et al. American gastroenterological association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140(3):1084–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Shaheen NJ, Weinberg DS, Denberg TD, et al. Upper endoscopy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2012;157(11):808–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Fitzgerald RC, Di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2014;63(1):7–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Vaughan TL, Fitzgerald RC. Precision prevention of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. Apr;12(4):243–8. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.24. Epub 2015 Feb 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Kamboj AK, Katzka DA, Iyer PG. Endoscopic Screening for Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Rationale, Candidates, and Challenges. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2021;31(1):27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Rodriguez S, Mattek N, Lieberman D, Fennerty B, Eisen G. Barrett's esophagus on repeat endoscopy: should we look more than once?. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(8):1892–1897. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01892.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Suna N, Parlak E, Kuzu UB, et al. The Prevalence of Barrett Esophagus Diagnosed in the Second Endoscopy: A Retrospective, Observational Study at a Tertiary Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(14):e3313. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Moriarty JP, Shah ND, Rubenstein JH, et al. Costs associated with Barrett's esophagus screening in the community: an economic analysis of a prospective randomized controlled trial of sedated versus hospital unsedated versus mobile community unsedated endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018. Jan;87(1):88–94.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.019. Epub 2017 Apr 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Gilani N, Gerkin RD, Ramirez FC, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in patients with moderate to severe erosive esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008. Jun 14;14(22):3518–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Benaglia T, Sharples LD, Fitzgerald RC, et al. Health benefits and costeffectiveness of endoscopic and nonendoscopic cytosponge screening for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2013;144:62–73 e6.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Heberle CR, Omidvari AH, Ali A, et al. Cost effectiveness of screeningpatients with gastroesophageal reflux disease for Barrett’s esophagus witha minimally invasive cell sampling device. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Sami SS, Moriarty JP, Rosedahl JK, et al. (2021). Comparative Cost Effectiveness of Reflux-Based and Reflux-Independent Strategies for Barrett's Esophagus Screening. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 116 (8), 1620–1631. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Jones B, Williams JL, Komanduri S, et al. Racial Disparities in Adherence to Quality Indicators in Barrett's Esophagus: An Analysis Using the GIQuIC National Benchmarking Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021. Jun 1;116(6):1201–1210. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Wani S, Williams JL, Falk GW, et al. An Analysis of the GIQuIC Nationwide Quality Registry Reveals Unnecessary Surveillance Endoscopies in Patients With Normal and Irregular Z-Lines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020. Nov;115(11):1869–1878. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Singh S, Bilal M, Pakhchanian H, et al. Impact of Obesity on Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the United States: A Multicenter Electronic Health Records Network Study. Gastroenterology. 2020. Dec;159(6):2221–2225.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.028. Epub 2020 Aug 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Hadi Y, Dulai PS, Kupec J, et al. Incidence, outcomes, and impact of COVID-19 on inflammatory bowel disease: propensity matched research network analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022. Jan;55(2):191–200. doi: 10.1111/apt.16730. Epub 2021 Dec 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).ASGE STANDARDS OF PRACTICE COMMITTEE, Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019. Sep;90(3):335–359.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Sharma P, Katzka DA, Gupta N, et al. Quality indicators for the management of Barrett's esophagus, dysplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma: international consensus recommendations from the American Gastroenterological Association Symposium. Gastroenterology. 2015. Nov;149(6):1599–606. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.007. Epub 2015 Aug 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Chen BL, Xing XB, Wang JH, et al. Improved biopsy accuracy in Barrett's esophagus with a transparent cap. World J Gastroenterol. 2014. Apr 28;20(16):4718–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Qumseya BJ, Bukannan A, Gendy S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors for Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(5):707–717.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Rubenstein JH, Omidvari AH, Lauren BN, et al. Endoscopic Screening Program for Control of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in Varied Populations: A Comparative Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):163–173. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Sami SS, Moriarty JP, Rosedahl JK, et al. Comparative Cost Effectiveness of Reflux-Based and Reflux-Independent Strategies for Barrett's Esophagus Screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021. Aug 1;116(8):1620–1631. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021. May 18;325(19):1965–1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238. Erratum in: JAMA. 2021 Aug 24;326(8):773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.21457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1287 – 1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Rubenstein JH, Burns JA, Arasim ME, et al. Yield of Repeat Endoscopy for Barrett's Esophagus After Normal Index Endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023; 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002204. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.