Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and weight loss in people with overweight, and semaglutide is in phase 3 clinical trials for treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). GLP-1RAs reduce alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and in phase 2 trials semaglutide resulted in histologic improvement in steatohepatitis1, 2.

Genetics may modify response to NAFLD treatment. In one recent systematic review, the PNPLA3-rs738409-G genotype associated with increased hepatic steatosis and fibrosis was associated with lower response to omega-3 fatty acids and dapagliflozin, but greater response to lifestyle interventions3.To our knowledge, no studies have investigated the impact of PNPLA3 genotype on GLP-1RA treatment effect. Notably, several weight-independent pathways by which GLP-1RAs decrease steatohepatitis, including lipid transport, beta-oxidation, and de novo lipogenesis, are altered in the PNPLA3-rs738409-G variant, suggesting PNPLA3 genotype may modify GLP-1RA treatment effects4. Our primary aim was to evaluate whether PNPLA3 genotype impacts treatment response to semaglutide.

We conducted a retrospective study of consecutive patients treated with semaglutide at Michigan Medicine before January 1, 2022. Genetic data were available through the Michigan Genomics Initiative, in which research subjects were genotyped on the Illumina HumanCoreExome v.12.1 array with genotypes imputed to the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine reference panel using Michigan Imputation Server v.1.5.75 , 6. Patients were excluded if semaglutide treatment lasted <3 months, semaglutide dosage was <1.0 mg weekly, or if another GLP-1RA was started following semaglutide treatment. The index date was the first date of semaglutide treatment and follow-up dates were defined as 6 (3–9), 12 (9–18), or 24 (18–36) months after the index date, with ranges allowed to minimize missingness. The primary outcome was change in ALT during follow-up, with ALT defined either as a continuous variable or as a 17-point reduction which is associated with histologic improvement7, 8. The primary predictor was PNPLA3-rs738409 genotype, defined as CC or CC/GG. Continuous variables were compared via nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum testing. Depending on statistical assumptions, categorical variables were evaluated using either chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the relationship between PNPLA3 genotype and decrease in ALT. Regression sensitivity analyses were performed after excluding patients taking oral semaglutide, those with normal baseline ALT, or both groups. A cutoff of P<.05 was used for statistical significance. For each analysis, participants with missing data were excluded.

220 patients met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 1). Average age was 59.2 years and 141 (64.1%) were female. Mean baseline body mass index (BMI) was 36.9 kg/m2; 172 (78.2%) had T2DM, 184 (83.6%) dyslipidemia, 180 (81.8%) hypertension, and 77 (35.0%) nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (International Classification of Diseases-9 571.8 or −10 K74.0 or K75.81). Mean baseline ALT was 29 [95% CI: 26–32] and 35 [30–40] (P=.10) in patients with PNPLA3-rs738409-CC vs. CG or GG genotypes, respectively. Average semaglutide treatment duration was 1.6 years. Most (93.6%) took subcutaneous semaglutide with the most common doses being 1 mg (45%), 2.4 mg (24%), and 2 mg weekly (17%); the remainder (6.4%) took oral semaglutide. PNPLA3-rs738409 genotype was CC, CG, and GG in 126, 81, and 13 patients, respectively. 47% of the patients had taken another GLP-1RA within the last six months, with the primary reasons for switching to semaglutide being inadequate glycemic control or weight loss, change in insurance coverage, or supply shortage of the previous GLP-1RA. There was no significant difference in PNPLA3-rs738409 genotype between those who had vs. had not previously taken another GLP1-RA (P=.60). There was no difference between ALT or BMI 12 months before semaglutide initiation vs. at baseline, overall or based on PNPLA3 genotype.

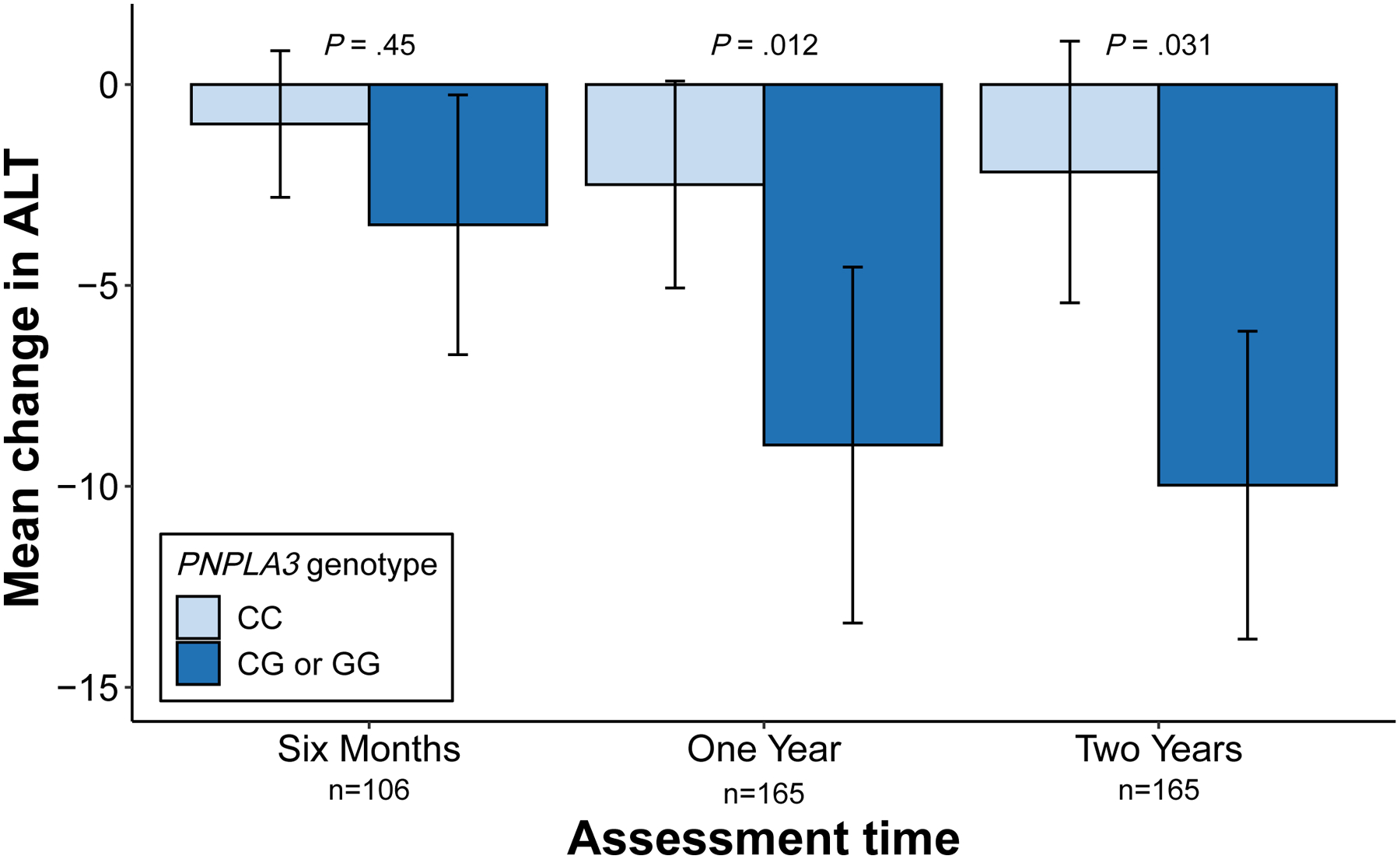

After 6 months of semaglutide treatment, change in ALT did not significantly differ across dichotomized PNPLA3 genotype. However, one year after semaglutide initiation, ALT decreased more in people carrying at least one PNPLA3 risk allele: mean ALT decrease 9.0 (4.5–13.4) vs. 2.5 (−0.1–5.1) U/L in individuals with CG/GG vs. CC CC genotype (P=.012). A similar pattern held at two years, with mean ALT decrease 10.0 [6.1–13.8] and 2.2 [−1.1–5.4] U/L in the CG/GG vs. CC genotypes, respectively (P=.031). BMI changes were similar across PNPLA3 genotype (mean BMI decrease 7.0% vs. 6.3% in CC and CG/GG genotypes, respectively; P=.93) and in an interaction model the BMI-PNPLA3 interaction term was not significant.

We conducted logistic regression analyses evaluating the odds of a decrease in ALT at 12 or 24 months based on PNPLA3 genotype (Supplementary Table 2). In univariable analysis, PNPLA3 group (CC vs. CG/GG) was associated with odds ratio (OR) 3.04 [1.30–7.08; P=.010] and 2.81 [1.20–6.60; P=.018] of having a 17-point decrease in ALT at year 1 and 2, respectively. We conducted additional analyses adjusted for age, sex, TM6SF2-rs58542926 genotype, and HSD17B13- rs72613567 genotype (model 1); model 1 variables plus change in BMI and diabetes status (model 2); and model 2 variables plus prior use of GLP-1RA use (model 3). Finally, we conducted an analysis including only individuals with elevated baseline ALT (>19/30 U/L in women/men, respectively). In all analyses, the associations between carriage of PNPLA3 risk alleles and halving of ALT were consistent. Change in BMI strongly correlated with ALT response, while change in hemoglobin A1c and low-density lipoprotein did not (data not shown). Change in year 2 vs. baseline Fibrosis-4 scores was not affected by PNPLA3 genotype (data not shown). Among patients receiving semaglutide, ALT decreased more in people with PNPLA3 risk alleles despite similar baseline ALT. Study limitations include the surrogate outcome of ALT change, though the threshold we used does correlate with histologic reduction in steatohepatitis.2, 7 Also, many patients had near-normal baseline ALT. In addition, our cohort was small and only 13 people had PNPLA3-rs738409-GG genotype. Finally, not all patients had NAFLD, though the prevalence was likely high based on high prevalence of obesity (80%) and T2DM (78%). People with PNPLA3-rs738409-G risk alleles may represent a select group for treatment with GLP-1RAs because they are at high baseline risk of progression to cirrhosis9 and also because they may experience greater decreases in ALT, which needs to be correlated further with response, in large clinical trials, using noninvasive tests and liver histology.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Effects of PNPLA3 genotype on change in alanine aminotransferase following semaglutide treatment. The graph shows the change in alanine aminotransferase (ALT, in U/L) at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after initiation of semaglutide treatment. PNPLA3 in the legend refers to PNPLA3-rs738409 genotype. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Overall group differences were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge the Michigan Genomics Initiative participants, Precision Health at the University of Michigan, the University of Michigan Medical School Central Biorepository, the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core and the University of Michigan Medical School Data Office for Clinical and Translational Research for providing data and specimen storage, management, processing, and distribution services, and the Center for Statistical Genetics in the Department of Biostatistics at the School of Public Health for genotype data curation, imputation, and management in support of the research reported in this manuscript.

Funding:

VLC was supported in part by NIDDK (K08 DK132312).

Conflicts of Interest:

Esteban Urias: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Nicholas Tedesco: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Antonino Oliveri: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Chinmay Raut: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Michigan Genomics Initiative (Matthew Zawistowski and Sebastian Zöllner): No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Elizabeth Speliotes: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Vincent Chen: Received grant funding from AstraZeneca and KOWA (to University of Michigan)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. The Lancet 2016;387:679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeckmans J, Gatzios A, Schattenberg JM, et al. PNPLA3 I148M and response to treatment for hepatic steatosis: A systematic review. Liver Int 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luukkonen PK, Qadri S, Ahlholm N, et al. Distinct contributions of metabolic dysfunction and genetic risk factors in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2022;76:526–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das S, Forer L, Schönherr S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nature Genetics 2016;48:1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zawistowski M, Fritsche LG, Pandit A, et al. The Michigan Genomics Initiative: A biobank linking genotypes and electronic clinical records in Michigan Medicine patients. Cell Genom 2023;3:100257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang DQ, Sharpton SR, Amangurbanova M, et al. Clinical Utility of Combined MRI-PDFF and ALT Response in Predicting Histologic Response in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Kowdley KV, et al. Factors Associated With Histologic Response in Adult Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2019;156:88–95 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen VL, Oliveri A, Miller MJ, et al. PNPLA3 Genotype and Diabetes Identify Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease at High Risk of Incident Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2023;164:966–977 e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.