Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether urine biomarkers of kidney health are associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease among men living with and without HIV.

Design:

Cross-sectional study within the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) among 504 men with and without HIV infection who underwent cardiac computed tomography scans and had urine biomarkers measured within the preceding two years.

Methods:

Our primary predictors were four urine biomarkers of endothelial (albuminuria), proximal tubule dysfunction (alpha-1-microglobulin [A1M] and injury (kidney injury molecule-1 [KIM-1]) and tubulointerstitial fibrosis (pro-collagen-III N-terminal peptide [PIIINP]). These were evaluated for association with coronary artery calcium (CAC) prevalence, CAC extent, total plaque score, and total segment stenosis using multivariable regression.

Results:

Of the 504 participants, 384 were men with HIV (MWH) and 120 were men without HIV. In models adjusted for sociodemographic factors, cardiovascular disease risk factors, eGFR, and HIV-related factors, each two-fold higher concentration of albuminuria was associated with a greater extent of CAC (1.35-fold higher, 95% CI [1.11, 1.65]), and segment stenosis (1.08-fold greater, 95% CI [1.01, 1.16]). Associations were similar between MWH and men without HIV in stratified analyses. The third quartile of A1M showed an association with greater CAC extent, total plaque score, and total segment stenosis, compared with the lowest quartile.

Conclusions:

Worse endothelial and proximal tubule dysfunction as reflected by higher urine albumin and A1M, were associated with greater CAC extent and coronary artery stenosis.

Keywords: Biomarkers, kidney, subclinical cardiovascular disease, CAC, HIV, MACS

Background

Despite advances in HIV treatment, life expectancy gains among people living with HIV (PWH) remain dampened by an elevated risk of non-HIV comorbidities, including both atherosclerotic-related cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1–4] and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [5]. As in the general population, CKD, defined by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or albuminuria, is associated with subclinical CVD[1, 2, 6, 7] and adverse clinical cardiovascular outcomes [8–11].

Several tubular biomarkers have been identified that reflect different aspects of kidney health. For example, kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM1) is released during injury to the proximal tubules. Pro-collagen-III N-terminal peptide (PIIINP) is a component of the extracellular matrix. Its presence in the urine reflects ongoing tubulointerstitial fibrosis, an important prognostic indicator of progression to end-stage kidney disease. Finally, alpha-1-microglobulin (A1M) is a protein freely filtered at the glomerulus and normally reabsorbed by the proximal tubules in a healthy kidney; the presence of A1M in the urine reflects proximal tubular dysfunction [12, 13].

Prior work has shown that PWH have worse kidney tubular health, measured by the previously mentioned urine biomarkers, compared to persons without HIV infection[14]. In PWH, urine biomarkers of kidney health and injury are associated with kidney disease progression [13, 15] and all-cause mortality [13, 16]. In studies of non-HIV-infected individuals, urine biomarkers of kidney health are associated with kidney disease progression[17], all-cause mortality[18], heart failure[19], and atherosclerotic CVD, including acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary heart disease death[12, 18]. A previous sub-study of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) found that men with HIV (MWH) had a higher prevalence of coronary artery plaque and higher prevalence and extent of noncalcified plaque [1], relative to men without HIV, independent of CVD risk factors. Whether or not tubular damage may contribute independently to the higher CVD risk among PWH compared to the uninfected population remains unclear. We hypothesized that these differences in subclinical coronary artery disease by HIV serostatus might be partially due to subclinical impairments in kidney tubule health.

To evaluate the potential link between kidney tubule health and subclinical CVD, we estimated the associations of urine biomarkers of kidney tubular damage and albuminuria with subclinical CVD as assessed by cardiac computed tomography (CT). We hypothesized that markers of glomerular and tubular damage would be associated with subclinical CVD, independent of traditional CVD risk factors and that these associations would be more pronounced in MWH compared to the uninfected population.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study nested within the MACS, a prospective cohort initiated in 1984 to study the natural history of HIV-1 infection among gay and bisexual men based in Los Angeles, California; Chicago, Illinois; Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, D.C., and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania [20]. The MACS cohort enrolled men with and without HIV. The present analysis focused on the 504 men with and without HIV who completed a non-contrast CT for CAC screening between January 2010 and August 2013 as part of the MACS CVD-2 Substudy [1] and had measurements of urine biomarkers of tubular injury within the preceding two years as part of the MACS Kidney Study[21]. All men in the MACS CVD-2 Substudy did not have a history of coronary artery interventions or cardiac surgery. Participants with pre-existing kidney disease (eGFR <60) were still eligible for inclusion in the study; however, 124 men were excluded from CTA based on having either eGFRs <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 during previous MACS visits and within one month of CT, or having a history of atrial fibrillation. This resulted in 380 participants who underwent CTA (Supplemental Table 2). The details of the overall protocol of the MACS cohort, Kidney Substudy, and CVD-2 Substudy have been published previously [1, 20, 21]. The institutional review boards of participating institutions approved the study protocol, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The University of California, San Francisco, and San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Review Boards approved the present analysis.

Primary exposures:

Urine biomarkers were previously measured as a part of the MACS Kidney Study[21, 22]. Biomarkers were measured in urine samples stored at −80°C until biomarker measurement, without prior freeze-thaw, and included albuminuria, A1M, KIM-1, and PIIINP. These biomarkers were selected as an optimal set that captured four distinct dimensions of kidney damage. All biomarkers were measured at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Biomarker Laboratory. Urine A1M was measured using a commercially available assay (Siemens BNII nephelometer, Munich, Germany). The urine KIM-1 ELISA was constructed using commercially available reagents (R & D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Urine PIIINP was measured by a commercially available ELISA (USCN Life Sciences, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Urine albumin and creatinine were measured by immunoturbidimetry and colorimetric enzyme assay using a Siemens Dimension Xpand plus HM clinical analyzer (Siemens, Munich, Germany). Coefficients of variation for the urine measurements were: A1M, 3.5–8.8% KIM-1, 5.2%; PIIINP, <10%; albumin, 5.9%; and creatinine, 4.1%. Laboratory personnel performing the biomarker assays were blinded to participant clinical information.

Outcomes:

Details on the imaging protocols for subclinical CVD have been previously published[1, 23]. In brief, participants underwent non-contrast CT for CAC scoring between January 2010 and August 2013. For coronary CT angiography, participants received beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers as needed, and sublingual nitroglycerin was administered unless contraindicated. CT scanning was performed at one of four centers, with images transferred to the core CT reading center (Lundquist Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA). Images were read by blinded readers unaware of biomarker assay results and analyzed using the modified 15-segment model of the American Heart Association[24].

Among participants who underwent coronary non-contrast CTs, the presence of any coronary artery calcium (CAC) and CAC score were assessed. Prevalent CAC was defined as CAC Agatson score >0. Among participants who underwent coronary CT angiography total coronary plaque score and total segment stenosis were assessed using the modified 15-segment model of the American Heart Association. Plaque size was graded as: 0 = no plaque, 1 = mild plaque, 2= moderate plaque, 3 = severe plaque. Plaque score was defined as the sum of plaque size grades of all assessable coronary segments, up to a maximum score of 45. Segment stenosis was graded as: 0 = no plaque, 1 = 1–29% stenosis, 2 = 30–49% stenosis, 3 = 50–69% stenosis, 4 ≥ 70% stenosis. The total segment stenosis score was defined as the sum of scores across coronary segments up to a maximum score of 60.

Clinical covariates:

We included the following sociodemographic factors: age, race (categorized into White, Black, and Other due to small numbers in the non-White and non-Black categories), and Hispanic ethnicity. Factors related to MACS (study center and enrollment cohort dichotomized by prior to 2001 and 2001 onward). Urine creatinine was included to adjust for urine tonicity.

We included the following cardiovascular risk factors: history of hypertension (defined as systolic blood pressure >= 140, DBP >= 90, or diagnosis of hypertension plus use of hypertension medications), diabetes (defined as hemoglobin A1c >=6.5, serum glucose >= 126, or diagnosis of diabetes plus use of diabetes medications), and dyslipidemia. We also included body mass index (BMI), smoking systolic blood pressure (SBP), hemoglobin A1c, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides.

We included the following exposures: pack-years of tobacco and medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor [ACEi]/angiotensin-receptor blocker [ARB], lipid-lowering, antidiabetic).

We included kidney disease related factors (HCV serostatus, eGFR by serum creatinine race-free CKD-EPI), and among MWH, HIV risk factors (cumulative antiretroviral treatment [ART] years, current ART use, clinical history of AIDS, current CD4+, and HIV-1 RNA levels). Missing covariates were multiply imputed by fully conditional specification (n=30).

Statistical analyses:

We conducted descriptive analyses to evaluate the distributions of urine biomarkers of kidney health and coronary CT measures. As the urine biomarkers had right-skewed distributions, their values were log2-transformed to achieve normality and assessed as per two-fold difference. We also modeled the urine biomarkers as quartiles to evaluate for a non-linear association between the log2 transformed urine biomarkers of kidney health and subclinical coronary artery disease measurements. Biomarkers were assessed with staged adjustment for covariates in our primary analysis to illustrate the impact of covariates on the relationships of interest. The first model included sociodemographic factors, MACS enrollment factors, and urine creatinine. The second model additionally included cardiovascular disease risk factors, kidney disease, HIV related factors, and medication exposures. Poisson regression was used to evaluate the associations of urine biomarkers with CAC prevalence[25]. Because the CAC extent was both right-skewed and had a large percentage of zero values, we fit a Tobit regression model to handle left-censored values while assuming a normal distribution for the response, as previously described[26]. Among those with plaque, linear regression was used to model biomarker associations with the extent of plaque. Among those with total segment stenosis, linear regression was also used to examine associations with the extent of segment stenosis. For each model, we performed two staged adjustments: 1) study center, enrollment cohort, and urine creatinine; 2) those in the first model plus sociodemographic factors, CVD risk factors, HCV serostatus, HIV serostatus, and eGFR. The first model we term “minimally adjusted” and the second “fully adjusted.” We assessed for effect modification of the associations between kidney damage biomarkers and subclinical CVD by HIV serostatus through stratified analyses and the inclusion of interaction terms. For analyses restricted to MWH, we adjusted for antiretroviral regimen, CD4+ cell count and HIV-1 RNA level. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In a set of sensitivity analyses, we repeated our main analyses and included cumulative years of TDF use as a covariate.

Results:

A total of 504 individuals had previously undergone non-contrast CT imaging and had urine kidney health biomarker measurements available; 384 were HIV-seropositive and 120 were HIV-seronegative; 380 individuals underwent CTA. The median time between the biomarker visit and the CVD-2 substudy visit was 0.8 years (IQR 0.4–1.3 years). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Men with HIV were, on average younger, and had higher urine albumin, A1M, and KIM1 concentrations than their HIV-seronegative counterparts. Self-reported race/ethnicity, history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and eGFR were similar between MWH and their HIV-seronegative counterparts.

Table 1.

MACS Substudy participant characteristics at time of cardiovascular imaging, by HIV serostatus

| Men with HIV (n=384) | Men without HIV (n=120) | Total (n=504) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years ± SD | 53 ± 6 | 55 ± 7 | 54 ± 6 |

| Race-ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 219 (57) | 71 (59) | 290 (58) |

| Black | 129 (34) | 41 (34) | 170 (34) |

| Other | 36 (9) | 8 (7) | 44 (9) |

| Hispanic | 38 (10) | 10 (8) | 48 (10) |

| BMI (kg/m2 ± SD) | 26 ± 5 | 27 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 |

| Current tobacco use, n (%) | 114 (30) | 29 (24) | 143 (28) |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 236 (61) | 78 (65) | 314 (62) |

| Median systolic blood pressure, mmHg (IQR) | 125 (88–183) | 127 (99–174) | 126 (88–183) |

| Use of ACEi/ARBs, n (%) | 76 (20) | 19 (16) | 95 (19) |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 73 (19) | 25 (21) | 98 (19) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.6 (4–10) | 5.6 (5–14) | 5.6 (4.3–13.5) |

| Use of anti-diabetic medications, n (%) | 39 (10) | 13 (11) | 52 (10) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL- median (IQR) | 192 (81–335) | 192 (108–267) | 192 (81–335) |

| Median LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (IQR) | 107 (29–228) | 112 (38–186) | 108 (29–228) |

| Median HDL cholesterol, mg/dL (IQR) | 47 (20–151) | 53 (28–149) | 48 (20–151) |

| Median triglycerides, mg/dL (IQR) | 131 (28–3900) | 109 (28–463) | 124 (28–3900) |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, n (%) | 135 (35) | 37 (31) | 172 (34) |

| HCV seropositive, n (%) | 47 (12) | 10 (8) | 57 (11) |

| HIV seropositive, n (%) | 384 (100) | 0 (0) | 384 (76) |

| History of AIDS | 54 (14) | 0 (0) | 54 (11) |

| Undetectable viral load (%) | 285 (74) | - | - |

| Median current HIV RNA level, copies/mL (IQR) | 42 (20–50) | - | 42 (20–50) |

| Median current CD4+ count, cells/mm3 (IQR) | 588 (419–751) | - | 588 (419–751) |

| ART use, n (%) | 337 (88) | - | 337 (67) |

| TDF use, n (%) | 302 (79) | 302 (60) | |

| Median eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR) | 89 (23.0–120.7) | 88 (31–115) | 89 (23–121) |

| Median urine ACR, mg/g (IQR) | 6 (0.1–3101) | 4 (0.1–138) | 6 (0.1–101) |

| Median urine A1M, mg/dL (IQR) | 2 (0.2–548) | 1 (0.1–11) | 1 (0.1–548) |

| Median urine KIM-1, pg/mL (IQR) | 690 (8–7591) | 494 (3–4512) | 661 (3–7591) |

| Median urine PIIINP, pg/mL (IQR) | 6639 (490–491577) | 6493 (737–55692) | 6639 (490–491577) |

BMI, body mass index; ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ART, antiretroviral therapy; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; A1m, alpha 1 microglobulin; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule 1; PIIINP, procollagen III, N-terminal propeptide.

History of hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure >=140 or diastolic blood pressure >= 90, or prior diagnosis of hypertension along with use of antihypertensive medication; history of diabetes defined as Hgb A1c >= 6.5 or glucose >=126, or prior diagnosis of diabetes along with use of antidiabetic medication; Undetectable viral load defined as <80 copies/ mL

Baseline characteristics are from the closest measure prior to or on outcome visit, no longer than 24 months prior.

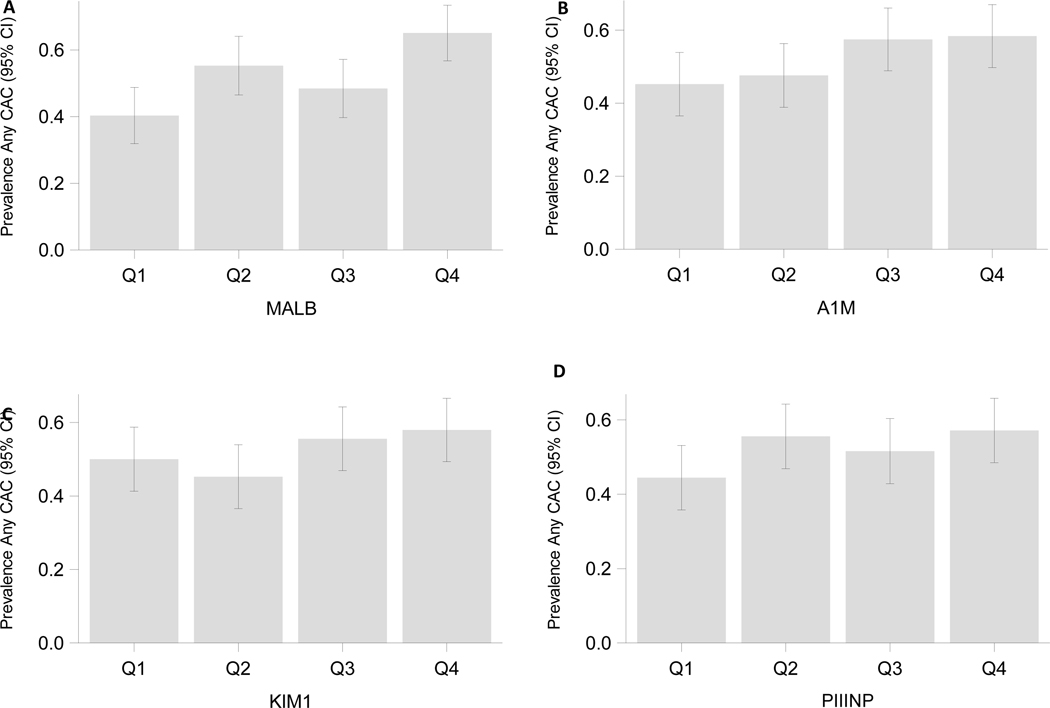

CAC Prevalence

CAC was prevalent in 53% of MWH and 51% of HIV-seronegative men. By biomarker quartile, CAC prevalence appeared to be greater with worse albuminuria and A1M (Figure 1). In minimally adjusted models, levels of urine albumin and A1M were weakly associated with CAC prevalence, with respective effect sizes of 9% and 7% greater prevalence of CAC per two-fold higher urine biomarker. In fully adjusted models, the association of albuminuria with prevalent CAC remained marginally significant, whereas A1M’s association with CAC prevalence no longer reached statistical significance (Table 2). When biomarkers were modeled by quartile in fully adjusted analyses, higher quartiles of albuminuria and A1M appeared to be associated with greater CAC prevalence than their respective lowest quartiles (Figure 2A).

Figure 1: Kidney biomarker quartiles and coronary artery calcium prevalence in cross-sectional study of MACS.

Table 2.

Associations of urine biomarkers of kidney health with coronary artery calcification, plaque and stenosis in cross-sectional substudy of MACS

| Minimally adjusted* | Fully adjusted** | Fully adjusted, among MWH*** | Fully adjusted, among men without HIV** | Interaction between biomarker and HIV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: CAC Prevalence (Agatston score >0) (n=504) | |||||

| Prevalence Ratio per two-fold higher biomarker concentration (95% CI) | p-value for biomarker*HIV | ||||

| Albumin | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 1.05 (1.00–1.09) | 1.01 (0.90–1.14) | 0.05 |

| A1M | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | 0.18 |

| KIM1 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 0.05 |

| PIIINP | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 1.04 (0.86–1.25) | 0.13 |

| Outcome: CAC extent (Log of Agatston score + 1) (n=504) | |||||

| Fold DIfference per two-fold higher biomarker (95% CI) | p-value for biomarker*HIV | ||||

| Albumin | 1.65 (1.37–1.99) | 1.35 (1.11–1.65) | 1.33 (1.07–1.65) | 1.41 (0.71–2.82) | 0.02 |

| A1M | 1.44 (1.12–1.86) | 1.20 (0.91–1.57) | 1.22 (0.91–1.62) | 1.27 (0.53–3.04) | 0.04 |

| KIM1 | 1.20 (0.92–1.58) | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) | 0.78 (0.57–1.07) | 1.30 (0.73–2.31) | 0.02 |

| PIIINP | 1.17 (0.87–1.56) | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) | 0.91 (0.66–1.25) | 1.31 (0.58–2.94) | 0.11 |

| Outcome: Coronary artery plaque score (n = 298) | |||||

| Fold DIfference per two-fold higher biomarker (95% CI) | p-value for biomarker*HIV | ||||

| Albumin | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | 1.06 (1.00–1.14) | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) | 1.04 (0.85–1.27) | 0.13 |

| A1M | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 1.00 (0.94–1.08) | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) | 0.93 (0.77–1.12) | 0.49 |

| KIM1 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | 0.46 |

| PIIINP | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 1.00 (0.83–1.22) | 0.31 |

| Outcome: Total segment stenosis >50% (n=298) | |||||

| Fold DIfference per two-fold higher biomarker (95% CI) | p-value for biomarker*HIV | ||||

| Albumin | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | 0.11 |

| A1M | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) | 0.91 (0.75–1.10) | 0.32 |

| KIM1 | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 1.00 (0.86–1.15) | 0.33 |

| PIIINP | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.97 (0.80–1.18) | 0.37 |

MWH, men with HIV; A1M, alpha 1 microglobulin; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule 1; PIIINP, procollagen III, N-terminal propeptide

study center and enrollment cohort (dichotomized by prior to 2001), sociodemographic factors (age, race (categorized into White, Black and Other due to small numbers in the non-white and non-black categories), and Hispanic ethnicity), and urine creatinine;

history of hypertension, history of diabetes, and history of dyslipidemia, SBP, A1c, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and medications (ACEi/ARB, lipid-lowering, antidiabetic), BMI, and pack-years of tobacco smoking ); HIV serostatus and other comorbidities (HCV), and eGFR (CKD-Epi, race-free).

additionally adjusted for HIV disease course for MWH (Cumulative HAART years, History of AIDS, current HIV viral load, current CD4, currently on HAART)

Bolded values indicate statistical significance at p<0.05

Figure 2: Adjusted associations of kidney biomarker quartiles with coronary artery calcium prevalence and extent in MACS.

A, associations of kidney biomarker quartiles with coronary artery calcium prevalence by Poisson regression in MACS; B, associations of kidney biomarker quartiles with coronary artery calcium extent by Tobit regression in MACS. Note the x-axis scale differs between subfigures.

All models are adjusted for study center and enrollment cohort (dichotomized by prior to 2001.), urine creatinine, sociodemographic factors (age, race (categorized into White, Black and Other due to small numbers in the non-white and non-black categories), and Hispanic ethnicity); history of hypertension, history of diabetes, and history of dyslipidemia, SBP, A1c, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and medications (ACEi/ARB, lipid-lowering, antidiabetic), BMI, and pack-years of tobacco smoking ); HIV serostatus and other comorbidities (HCV), and eGFR (CKD-Epi, race-free).

When stratified by HIV serostatus, higher levels of urine albumin were more strongly associated with the prevalence of CAC among MWH than men without HIV (Table 2).

CAC Extent

CAC extent was generally greater with ascending biomarker quartiles across all four biomarkers (Supplemental Figure 3). Each two-fold higher level of albuminuria, A1M, KIM1, and PIIINP was associated with greater CAC extent in minimally adjusted models with effect sizes ranging from 1.2–1.7-fold greater CAC extent. In fully adjusted models, each two-fold higher albuminuria remained associated with a 1.4-fold greater CAC extent, while A1M was directionally associated with a 1.2-fold greater CAC burden (Table 2).

When analyzed by HIV serostatus, the associations between biomarkers and CAC extent were slightly stronger in men without HIV compared to MWH across all four biomarkers, although only the interaction terms for albuminuria, A1M, and KIM1 reached statistical significance (Table 2).

Coronary Artery Plaque Score

The distribution of total plaque score appeared incrementally higher with ascending biomarker quartiles of albumin, KIM1, and PIIINP (Supplemental Figure 4). Among those with any plaque, each 2-fold higher urine albumin level was associated with a greater total plaque score in minimally adjusted models. However, this association was attenuated in fully adjusted models. Analyses stratified by HIV serostatus were similar and none of the biomarker-HIV interactions reached statistical significance (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 2A).

Total Segment Stenosis

Each higher biomarker quartile of albuminuria, KIM1, and PIIINP appeared to be associated with a greater total segment stenosis score in a graded fashion (Supplemental Figure 5). In minimally and fully adjusted models, each 2-fold higher level of albuminuria was associated with more significant total segment stenosis among those with detectable stenoses. Analyses by HIV serostatus were qualitatively similar, and none of the biomarker-HIV interactions reached statistical significance (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 2B).

Sensitivity analyses, biomarkers by quartile, TDF use

In sensitivity analyses, we modeled biomarkers by quartile in fully adjusted models. Associations between biomarkers and CAC prevalence and CAC extent were qualitatively similar to the continuous analyses (Figures 2A, 2B), however the third quartile of A1M was associated with CAC extent. Similarly, when biomarkers were modeled as quartiles, stratified by HIV serostatus, associations with CAC prevalence and CAC extent were qualitatively similar to their continuous counterparts (Supplemental Figures 1A, 1B). When evaluated by quartile, individuals in the highest quartile of albuminuria, and second and third quartiles of A1M had higher total plaque scores and greater total segment stenosis, compared to those in the lowest quartiles. (Figures 3A, 3B). Inclusion of TDF use as a covariate showed results that were nearly identical to the main analyses (Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 3: Adjusted associations of kidney biomarker quartiles with total plaque score and segment stenosis in MACS.

A, associations of kidney biomarker quartiles with total plaque score, among those with any plaque, by linear regression in MACS; B, associations of kidney biomarker quartiles with total segment stenosis, among those with any stenosis, by linear regression in MACS.

All models are adjusted for study center and enrollment cohort (dichotomized by prior to 2001.), urine creatinine, sociodemographic factors (age, race (categorized into White, Black and Other due to small numbers in the non-white and non-black categories), and Hispanic ethnicity); history of hypertension, history of diabetes, and history of dyslipidemia, SBP, A1c, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and medications (ACEi/ARB, lipid-lowering, antidiabetic), BMI, and pack-years of tobacco smoking ); HIV serostatus and other comorbidities (HCV), and eGFR (CKD-Epi, race-free).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the link between kidney tubular health and subclinical atherosclerotic CVD. In these analyses of well-characterized men with and without HIV in the MACS cohort, we found that urine biomarkers of kidney glomerular and tubular health were associated with a greater burden of subclinical CVD. These findings suggest that even early reductions in kidney health may predispose to or be a marker of the development of CVD in middle-aged men.

Kidney tubular biomarkers have been shown to be associated with clinical CVD outcomes[12]. Conversely, eGFR has been shown to have a graded relationship with CAC extent[7]. In contrast to these two relationships, data on measures of kidney tubular health and early subclinical CVD are lacking. In the present study, higher urine A1M concentrations, a measure of proximal tubule dysfunction, were associated with markers of subclinical CVD, independent of traditional CVD risk factors. However, the continuous associations were inconsistent across all subclinical CVD outcomes that we evaluated, possibly as a result of non-linear associations seen in the categorical analysis of A1M. The intersection of kidney and heart health is a complex and incompletely understood pathway. The kidney tubules are a major site of water reabsorption and ion transport, which could modulate blood pressure and CVD risk [27]. Despite the limitations of its cross-sectional design, our study implicates kidney tubular dysfunction, independent of eGFR, as a part of the pathway between kidney disease and atherosclerotic CVD[28]. However, additional studies are needed to determine if tubular dysfunction has a causal effect on CVD, or if it is simply a marker of increased CVD risk.

Albuminuria is an established marker of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risk [29–31]. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort, albuminuria was associated with a higher risk of both the development and progression of CAC [32]. Additionally, urine albumin is associated with increased CAC score and other measures of subclinical CVD [33, 34]. Consistent with prior studies, we found that higher levels of urine albumin were associated with several measures of subclinical CVD in this cohort. Our study is the first to evaluate this association among persons with HIV; future studies will be needed to substantiate our observation that the association of albuminuria with subclinical CVD appeared less strong among MWH.

Urinary biomarkers were measured on average one year before CT scans were performed. Data on longitudinal intra-individual change in urine biomarkers are lacking. A1M and KIM-1 have been shown to increase a year after TDF initiation [35]. We postulate that biomarkers measuring acute injury, namely KIM-1, might normalize with increasing distance from an acute insult. This may attenuate associations given the time between biomarker measurement and CT scans. In contrast, measures of dysfunction such as albuminuria and A1M may be more stable over time, compared to measures of acute injury. Although data on the natural course of biomarkers after an insult are lacking, ambulatory measures of biomarkers have been shown to be consistently associated with subsequent risk for various outcomes in both PWH and people without HIV[13, 36–38]. Therefore, we believe overwhelmingly that our findings reflect chronic associations between kidney damage and CAD.

The present study shows that while urine markers of both glomerular health and kidney tubular health are independently associated with subclinical CVD, glomerular health appears to be the more robust marker for the risk of subclinical CVD. Given the relatively preserved kidney function and lower burden of other comorbidities in the MACS cohort, the extent of kidney tubular dysfunction may have been insufficient to cause observable differences in subclinical cardiovascular health. Future studies should examine whether stronger and more consistent associations between kidney tubular health and subclinical CVD exist in older adults with more advanced kidney disease or greater co-morbidity burden.

HIV infection and ART have been previously shown to be associated with increased tubular damage markers[13, 28, 35, 39]. Additionally, HIV infection has been implicated in subclinical CVD. In a previous analysis of the MACS cohort, Post et al. showed that MWH had a higher prevalence of CAC compared with HIV-seronegative men; however, this association was attenuated after adjustment for CVD risk factors, and HIV was not associated with CAC severity [1]. In contrast, a smaller study by Lo et al. found MWH to have a higher burden and extent of coronary atherosclerosis and a higher prevalence of CAC than men without HIV [40]. In the present study, across all four biomarkers for CAC extent, the associations between biomarker and subclinical CVD appeared stronger among men without HIV. However, the respective interaction terms did not always reach statistical significance. We speculate that this may be due to etiologies of kidney dysfunction among MWH that do not contribute to subclinical CVD as strongly as traditional etiologies of kidney dysfunction seen among men without HIV, such as hypertension or diabetes. For example, we observed significant associations between urine albumin and CAC extent even after multivariable adjustment among MWH, although the point estimate seemed stronger in men without HIV. Among MWH, albuminuria may result from the direct effects of HIV infection on the kidneys rather than systemic endothelial injury. Conversely, albuminuria in men without HIV may more specifically reflect endothelial injury shared with CVD pathogenesis. The care of PWH has advanced towards earlier and more tolerable antiretroviral regimens, including much less use of TDF. Given that TDF has known nephrotoxic effects, we might expect that if the study were to be repeated with more contemporary antiretroviral medications, that the associations in MWH would be more similar to those seen in men without HIV.

Our study has several important limitations. Firstly, the study was conducted in a subset of the MACS cohort, which comprised men with relatively preserved kidney function; specifically, only participants with an eGFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2 were eligible for CTA. This may limit the generalizability of these results to populations with worse kidney function. Secondly, the study is cross-sectional, limiting our ability to determine causal directionality, or whether both renal and cardiac disease are influenced by a third unmeasured factor. Thirdly, exposure and outcome measurement were not strictly simultaneously measured with a maximum difference of 24 months (median 9, IQR 4–15 months) between the biomarker measurements and the CT scan (Supplemental Table 1). Fourthly, the exposures and outcomes of this study were measured over 10 years ago. We cannot exclude the possibility that changes in care for PWH might alter the relationships between glomerular and tubular dysfunction and subclinical cardiovascular disease, limiting the generalizability of the study. Fifthly, we only adjusted for HCV serostatus and did not include viral load; therefore, we cannot exclude residual confounding from severity of HCV infection. Lastly, the MACS Kidney Study measured a relatively small number of biomarkers of kidney health. Future studies are needed to evaluate novel tubular biomarkers of kidney health which capture other aspects of tubule structure and function such as UMOD and EGF.

In conclusion, among men with and without HIV, higher levels of urine albumin and A1M were associated with some measures of subclinical CVD. Our findings underscore the importance of albuminuria as a marker of CVD. To a lesser magnitude, tubular dysfunction as reflected by A1M may be another important risk marker of subclinical CVD however, investigations in other cohorts are needed to determine if this association holds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study participants and dedication of the staff at the MWCCS sites.

Funding:

MACS Kidney Study is funded by grant 1 R01 AG034853-01A2 (PI, Shlipak), which was administered by the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and with resources of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California.

The MACS CVD 2 study is funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), R01 HL095129-01 (PI, Post).

ML was supported in part by the UCSF Yearlong Inquiry Program and NIH 2TL1TR001871-06.

CRP is supported by NIH grants R01HL085757, U01DK114866, U01DK106962, U01DK129984 and R01DK093770 and P30DK079310.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant number UL1TR001881.

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), now the MACS/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). MWCCS (Principal Investigators): Atlanta CRS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-HL146241; Baltimore CRS (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), U01-HL146201; Bronx CRS (Kathryn Anastos, David Hanna, and Anjali Sharma), U01-HL146204; Brooklyn CRS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-HL146202; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D’Souza, Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Topper), U01-HL146193; Chicago-Cook County CRS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-HL146245; Chicago-Northwestern CRS (Steven Wolinsky, Frank Palella, and Valentina Stosor), U01-HL146240; Northern California CRS (Bradley Aouizerat, Jennifer Price, and Phyllis Tien), U01-HL146242; Los Angeles CRS (Roger Detels and Matthew Mimiaga), U01-HL146333; Metropolitan Washington CRS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-HL146205; Miami CRS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-HL146203; Pittsburgh CRS (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), U01-HL146208; UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Jodie Dionne-Odom, Deborah Konkle-Parker, and James B. Brock), U01-HL146192; UNC CRS (Adaora Adimora and Michelle Floris-Moore), U01-HL146194. The MWCCS is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), National Institute On Aging (NIA), National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke (NINDS), National Institute Of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute On Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute Of Nursing Research (NINR), National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), and in coordination and alignment with the research priorities of the National Institutes of Health, Office of AIDS Research (OAR). MWCCS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR003098 (JHU ICTR), UL1-TR001881 (UCLA CTSI), P30-AI-050409 (Atlanta CFAR), P30-AI-073961 (Miami CFAR), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR), P30-MH-116867 (Miami CHARM), UL1-TR001409 (DC CTSA), KL2-TR001432 (DC CTSA), and TL1-TR001431 (DC CTSA).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study participants and dedication of the staff at the MWCCS sites.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

TTB has served as a consultant to ViiV Haelthcare, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Janssen.

CRP is a member of the advisory board and owns equity in RenalytixAI. He also serves as a consultant for Genfit.

References:

- 1.Post WS, Budoff M, Kingsley L, Palella FJ Jr., Witt MD, Li X, et al. Associations between HIV infection and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Annals of internal medicine 2014; 160(7):458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2007; 92(7):2506–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senoner T, Barbieri F, Adukauskaite A, Sarcletti M, Plank F, Beyer C, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis characteristics in HIV-infected patients on long-term antiretroviral therapy: insights from coronary computed tomography–angiography: Erratum. AIDS 2020; 34(6):961–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearns A, Gordon J, Burdo TH, Qin X. HIV-1–Associated Atherosclerosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017; 69(25):3084–3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szczech LA, Grunfeld C, Scherzer R, Canchola JA, van der Horst C, Sidney S, et al. Microalbuminuria in HIV infection. AIDS (London, England) 2007; 21(8):1003–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park M, Shlipak MG, Vittinghoff E, Katz R, Siscovick D, Sarnak M, et al. Associations of kidney injury markers with subclinical cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Clinical Nephrology 2015; 84 (2015)(12):358–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budoff MJ, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, Mohler ER 3rd, Lash J, Yang W, et al. Relationship of estimated GFR and coronary artery calcification in the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 58(4):519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heywood JT, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Mathur VS, Wigneswaran JR, Wynne J, et al. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and its impact on outcome in 118,465 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a report from the ADHERE database. Journal of cardiac failure 2007; 13(6):422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Newman A, Harris T, Peralta CA, Devarajan P, et al. Association of urinary injury biomarkers with mortality and cardiovascular events. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2014; 25(7):1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu C-y. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Risks of Death, Cardiovascular Events, and Hospitalization. New England Journal of Medicine 2004; 351(13):1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi AI, Li Y, Deeks SG, Grunfeld C, Volberding PA, Shlipak MG. Association between kidney function and albuminuria with cardiovascular events in HIV-infected persons. Circulation 2010; 121(5):651–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jotwani V, Katz R, Ix JH, Gutiérrez OM, Bennett M, Parikh CR, et al. Urinary Biomarkers of Kidney Tubular Damage and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Elders. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2018; 72(2):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jotwani V, Scherzer R, Abraham A, Estrella MM, Bennett M, Cohen MH, et al. Association of Urineα1-Microglobulin with Kidney Function Decline and Mortality in HIV-Infected Women. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2014; 10(1):63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jotwani V, Scherzer R, Abraham A, Estrella MM, Bennett M, Devarajan P, et al. Does HIV infection promote early kidney injury in women? Antiviral therapy 2014; 19(1):79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shlipak MG, Scherzer R, Abraham A, Tien PC, Grunfeld C, Peralta CA, et al. Urinary markers of kidney injury and kidney function decline in HIV-infected women. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012; 61(5):565–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peralta C, Scherzer R, Grunfeld C, Abraham A, Tien P, Devarajan P, et al. Urinary biomarkers of kidney injury are associated with all-cause mortality in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). HIV medicine 2014; 15(5):291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peralta CA, Katz R, Bonventre JV, Sabbisetti V, Siscovick D, Sarnak M, et al. Associations of urinary levels of kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) with kidney function decline in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2012; 60(6):904–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Newman A, Harris T, Peralta CA, Devarajan P, et al. Association of Urinary Injury Biomarkers with Mortality and Cardiovascular Events. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2014; 25(7):1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Driver TH, Katz R, Ix JH, Magnani JW, Peralta CA, Parikh CR, et al. Urinary Kidney Injury Molecule 1 (KIM-1) and Interleukin 18 (IL-18) as Risk Markers for Heart Failure in Older Adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2014; 64(1):49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR Jr. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. American journal of epidemiology 1987; 126(2):310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jotwani V, Scherzer R, Estrella MM, Jacobson LP, Witt MD, Palella FJ Jr., et al. HIV Infection, Tenofovir, and Urine α1-Microglobulin: A Cross-sectional Analysis in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 68(4):571–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jotwani V, Scherzer R, Estrella MM, Jacobson LP, Witt MD, Palella F, et al. Brief Report: Cumulative Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Exposure is Associated With Biomarkers of Tubular Injury and Fibrosis in HIV-Infected Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73(2):177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacıoğlu Y, Gupta M, Choi TY, George RT, Deible CR, Jacobson LP, et al. Use of cardiac CT angiography imaging in an epidemiology study - the Methodology of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study cardiovascular disease substudy. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2013; 13(3):207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson KM, Johnson HE, Zhao Y, Dowe DA, Staib LH. Scoring of Coronary Artery Disease Characteristics on Coronary CT Angiograms by Using Machine Learning. Radiology 2019; 292(2):354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao K. Proper Estimation of Relative Risk Using PROC GENMOD in Population Studies. SAS Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reilly MP, Wolfe ML, Localio AR, Rader DJ. Coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular risk factors: Impact of the analytic approach. Atherosclerosis 2004; 173(1):69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho KM, Morgan DJR. The Proximal Tubule as the Pathogenic and Therapeutic Target in Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron 2022:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jotwani V, Katz R, Ix JH, Gutiérrez OM, Bennett M, Parikh CR, et al. Urinary Biomarkers of Kidney Tubular Damage and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Elders. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2018; 72(2):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anyanwagu U, Donnelly R, Idris I. Albuminuria Regression and All-Cause Mortality among Insulin-Treated Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Analysis of a Large UK Primary Care Cohort. American journal of nephrology 2019; 49(2):146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sung K-C, Ryu S, Lee J-Y, Lee SH, Cheong E, Hyun Y-Y, et al. Urine Albumin/Creatinine Ratio Below 30 mg/g is a Predictor of Incident Hypertension and Cardiovascular Mortality. Journal of the American Heart Association 2016; 5(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang M, Kwon S, Lee J, Shin J-I, Kim YC, Park JY, et al. Albuminuria within the Normal Range Can Predict All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality. Kidney360 2022; 3(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeFilippis AP, Kramer HJ, Katz R, Wong ND, Bertoni AG, Carr J, et al. Association Between Coronary Artery Calcification Progression and Microalbuminuria. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3(6):595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kramer H, Jacobs DR, Bild D, Post W, Saad MF, Detrano R, et al. Urine albumin excretion and subclinical cardiovascular disease. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979) 2005; 46(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Son J-W, Jang E-H, Kim M-K, Kim H-L, Baek K-H, Song K-H, et al. Usefulness of Albuminuria as Predictor for Coronary Artery Stenosis, Regardless of Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. The American Journal of Cardiology 2012; 110(10):1434–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang WR, Scherzer R, Estrella MM, Ascher SB, Muiru A, Jotwani V, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate initiation and changes in urinary biomarker concentrations among HIV-infected men and women. AIDS 2019; 33(4):723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jotwani V, Garimella PS, Katz R, Malhotra R, Bates J, Cheung AK, et al. Tubular Biomarkers and Chronic Kidney Disease Progression in SPRINT Participants. Am J Nephrol 2020; 51(10):797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ascher Simon B, Scherzer R, Estrella Michelle M, Shlipak Michael G, Ng Derek K, Palella Frank J, et al. Associations of Urine Biomarkers with Kidney Function Decline in HIV-Infected and Uninfected Men. American Journal of Nephrology 2019; 50(5):401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garimella PS, Lee AK, Ambrosius WT, Bhatt U, Cheung AK, Chonchol M, et al. Markers of kidney tubule function and risk of cardiovascular disease events and mortality in the SPRINT trial. European heart journal 2019; 40(42):3486–3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ascher SB, Scherzer R, Estrella MM, Shigenaga J, Spaulding KA, Glidden DV, et al. HIV preexposure prophylaxis with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine and changes in kidney function and tubular health. AIDS 2020; 34(5):699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo J, Abbara S, Shturman L, Soni A, Wei J, Rocha-Filho JA, et al. Increased prevalence of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis detected by coronary computed tomography angiography in HIV-infected men. AIDS 2010; 24(2):243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.