Abstract

Uterine fibroids (UF), also called uterine leiomyoma, is one of the most prevalent uterine tumors. UF represents a serious women’s health global problem with a significant physical, emotional, and socioeconomic impact. Risk factors for UF include racial disparities, age, race, hormonal factors, obesity, and lifestyle (diet, physical activity, and stress). There are several biological contributors to UF pathogenesis such as cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation. This review addresses tumor immune microenvironment as a novel mediator of ECM deposition. Polarization of immune microenvironment towards the immunosuppressive phenotype has been associated with ECM deposition. Immunosuppressive cells include M2 macrophage, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and Th17 cells, and their secretomes include interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, IL-22, arginase 1, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1). The change in the immune microenvironment not only increase tumor growth but also aids in collagen synthesis and ECM disposition, which is one of the main hallmarks of UF pathogenesis. This review invites further investigations on the change in the UF immune microenvironment as well as a novel targeting approach instead of the traditional UF hormonal and supportive treatment.

Keywords: Uterine Fibroids, MDSCs, TH17, M2 Macrophage, ECM

Introduction

Uterine fibroids (UF), also known as leiomyoma, is a benign uterine tumor with an unclear etiology that predominately affects the myometrium. Most of these monoclonal, estrogen-dependent uterine neoformations affect women in their reproductive years and 80% of them experience symptoms for the rest of their lives. Uterine fibroids can cause anemia from prolonged or heavy monthly flow, pelvic pain, or pressure, and difficulties in achieving successful pregnancies. UF develops as a result of changes of myometrial microenvironment under particular pathological circumstances [1].

It is unclear exactly what molecular and cellular alterations caused the UF to form and grow. UF are distinguished by an excessive buildup of extracellular matrix (ECM) elements like collagen, fibronectin, laminins, and proteoglycans. ECM deposition is thought to be the root of aberrant bleeding and pelvic pressure or pain [2]. ECM proteins induce mechanotransduction, a mechanism wherein increased tissue stiffness leads to bidirectional signaling via integrins and downstream mediators like Rho/p38 MAPK/ERK [3]. To control these tumors, it may be possible to prevent additional ECM formation and the associated fibrosis [4].

Additionally, uterine fibroids express proteolytic enzymes that are essential for ECM remodeling, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs). MMPs and other proteolytic enzymes release growth factors and activate numerous signal transduction pathways by destroying ECM components. Growth factors and steroid hormones control how much ECM accumulates and how it functions. Growth factors are bound and hidden by the ECM, which increases their stability and limits their activity. Among the suggested predisposing factors for ECM deposition is the shift in immune microenvironment from the proinflammatory type 1 immunity to the anti-inflammatory type 2 immunity [5].

Type 2 immunity is characterized, to some extent, as a counter-regulatory process controlling type 1 immunity and exhibits both host-protective and pathogenic qualities. Type 2 immunity promotes resolution of the inflammatory process after an injury. Chronic stimulation of type 2 response leads to tissue fibrosis [6]. The cytokines interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 are produced more frequently in type 2 immunity [7]. In this review, we highlight the involvement of type 2 immunosuppressive cells such as M2 macrophage, MDSCs, and Th17 in UF pathogenesis by affecting ECM accumulation

1. - Macrophage

Macrophages are myeloid immune cells that exhibit a propensity for enthusiastic phagocytosis [8]. Macrophages serve a crucial part in the body’s homeostatic maintenance by eliminating internal waste and repairing tissue, in addition to acting as a defense against infections like bacteria. However, because macrophages can act as effectors for cell-mediated immunity and present antigens to T cells, it is recognized that they play a role in the onset of infectious illnesses, malignancies, and chronic inflammatory conditions including arteriosclerosis [9].

Macrophages can develop a variety of states depending on their environment, which are roughly categorized into two main groups: M1-like or pro-inflammatory and M2-like or anti-inflammatory [10]. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), TNF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and various pathogen-derived signals, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), induce the formation of M1-like macrophages. M1 macrophages entrap, phagocytose, and lyse tumor cells. Additionally, M1’s have the capacity to deliver tumor antigens which would encourage other leukocytes to perform cytotoxic actions [11]. For instance, immunostimulatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)) produced by M1 phenotype macrophages may boost CD8+ T cells and NK cells, initiating apoptosis in tumor cells [12]. M1 phenotype secrete high levels of pro-inflammatory molecules like TNF, IL-1, and IL-12, carry out efficient antigen presentation and co-stimulation, and regulate defense mechanisms against infections and cancer [13]. Less immunogenic antigens are present in tumor stem cells, but these cells are more active in proliferating and differentiating. Given the heterogeneity and tumor-specific immune escape mechanisms, tumor stem cells may use M1 phenotype macrophages as a natural filter to evade killing and advance to the next stage. With low antigenicity, most macrophages transit from the M1 phenotype to the M2 phenotype, which is more likely to contain immunosuppressive potentials in tumor nests [14].

In addition to the pathogen defense, M2 macrophages clear apoptotic cells, decrease inflammatory responses, and induce wound healing. M2 phenotype macrophages support tumor growth by generating growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and b-fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) [15].

In actuality, all macrophages are important for the growth of the initial tumor nest and encourage subsequent spread of the tumor. In light of M1/M2 ratios and responses, immunoediting theory suggests that tumor growth can be viewed as stages of immunological eradication, equilibrium, and escape [16]. M2 macrophage was found to induce collagen synthesis and thus upregulation of UFs through secretion of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and TGF-β1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Effect of M2 macrophage on collagen synthesis

1.1. IL-4 and collagen synthesis

In addition to Th2 lymphocyte; basophils, mast cells, and eosinophils are the main producers of IL-4. La Flamme, Kharkrang [17] results supported that type II macrophages (M2 macrophages) as an important innate immune source of IL-4. The role of the IL-4 protein is to induce the development of naive helper T lymphocyte cells into T-helper-2 cells (TH2), as well as the production of several other cytokines, such as IL-13, IL-5, and IL-10 [18]. Sosna, Kolesár [19] found an association between polymorphisms of the IL4 gene promotor at positions −590 C/T and −33 C/T and observed the risk of leiomyoma.

Interleukin 4 is expected to induce UF collagen synthesis through multiple effects. Compared to myometrium progenitor cells, leiomyoma progenitor cells exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher levels of IL4 [20]. Krsteski, Jurgec [21] showed that rs1801275 (IL4R) can predispose patients to develop multiple UF. Măluţan, Drugan [22] found that women with endometriosis had considerably higher mean serum levels of IL-1Ra, IL-4, and IL-10 than did women in the control group without the condition. Aoudjehane, Pissaia [23] found that IL-4 has profibrotic effects by activating intrahepatic myofibroblasts and inducing collagen synthesis and release which requires STAT-6 activation and IL4-R binding.

Liang, Zhang [24] showed that IL-4 stimulated the synthesis of fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and STAT6 in mouse bone marrow monocytes. Knipper, Willenborg [25] showed that lysyl hydroxylase 2 (LH2), an enzyme that controls enduring pro-fibrotic collagen cross-links, is induced in fibroblasts by IL-4R signaling in macrophages. Sugimoto, Enjoji [26] showed that in comparison to untreated cells, treatment of LI90 cells with IL-4 enhanced collagen I synthesis. In a JAK/STAT-dependent way, IL-4 strongly and selectively stimulates prostate stromal fibroblasts to produce collagen mRNA and protein [27].

1.2. IL-10 and collagen synthesis

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a secreted inhibitory cytokine that is produced by T helper (Th) 2 cells and M2 macrophages and has been shown to prevent Th1 cells from producing cytokines [28]. M2 macrophages produce more IL-10 and other anti-inflammatory cytokines than other macrophage subtypes [29]. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which include dendritic cells (DCs), Langerhans cells, and macrophages, are just a few examples of how IL-10 affects both innate and adaptive immunity [30]. IL-10 inhibits the antigen-presenting ability of monocytes by down-regulating class II MHC, hence preventing the development of human T lymphocytes that are specific for antigen [31]. Compared to myometrium progenitor cells, leiomyoma progenitor cells exhibited a significant 40% increase in IL10 levels and significantly lower levels of Th1/Th17 cytokines (IL6, IL12, IL17A, IFN-γ, G-CSF, and TGF-β1) [20].

Jung, Ma [32] found that in vivo IL-10 administration induced an increase in fibroblast activation (proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis). Matsuzaki, Pouly [33] showed that endometriotic stromal cells developed a pro-fibrotic phenotype as a result of IL-10, including increased cell division, the production of collagen type I, the appearance of positive stress fibers for smooth muscle actin, and contraction of collagen gel. Chang, Liu [34] showed that with the development of endometriosis, IL-10+Th17 cells in the endometriotic milieu rapidly increased. Yang, Zhou [35] results suggest that by increasing the release of IL-10 and TGF-β, the interaction between macrophages and endometrial stromal cells may reduce the cytotoxicity of NK cells. It may also cause immunological escape of ectopic pieces and encourage the onset and progression of endometriosis.

Matsuzaki, Pouly [33] found that endometriotic stromal cells underwent pro-fibrotic phenotypic induction by IL-10, including cell proliferation, collagen type I synthesis, α-SMA positive stress fibers, and collagen gel contraction which was reduced by STAT3 gene knockdown. On the other hand, IL-10 showed no appreciable influence on the pro-fibrotic phenotype of healthy women’s endometrial stromal cells. Bhattacharyya, Boostanpour [36] findings reveal a novel, IL10-dependent mechanism of macrophage polarization leading to fibroblast activation after injury.

1.3. IL-13 and collagen synthesis

A crucial T helper 2 (Th2) cell-derived cytokine called IL-13 has been shown to play a role in regulating both pathological processes like autoimmune diseases, bronchial asthma, and organ fibrosis as well as normal physiological processes like inflammation, immune response, mucus production, and tissue reconstruction [37]. Li, Liu [38] showed that IL-13 increased expression of CCR4, CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL2 which induces Treg activation and recruitment, supporting its immunosuppressive role. Krsteski, Jurgec [21] found that rs20541 (IL-13) may contribute to susceptibility of UF development. Compared to myometrium progenitor cells, leiomyoma progenitor cells exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher levels of IL13 [20].

Firszt, Francisco [39] found that when compared to healthy controls, IL-13, dramatically increased the formation of collagen type-1 in asthma patients and thus airway remodeling Through a mechanism involving TGF-β1 and MMP-2, IL-13 enhances airway remodeling. O’Reilly, Ciechomska [40] showed that IL-13 increased collagen expression in a STAT6-dependent way. Sugimoto, Enjoji [41] results suggested that HSCs were directly impacted by IL-13, which increased collagen synthesis and decreased cell division. Data from Bailey, Bland [42] indicate that the IL-13 pathway is activated in the fibrotic intestinal muscle of Crohn’s patients and it inhibits fibroblast MMP synthesis and down-regulates matrix degradation, resulting in excessive collagen deposition. Lu, Liu [43] demonstrated that in primary cultured mouse airway fibroblasts, IL-13 dose- and time-dependently increased collagen synthesis which was countered by inhibiting the JAK/STAT6 signal pathway. Cardilo-Reis, Gruber [44] showed that IL-13 administration promotes collagen production in established lesions of atherosclerosis-prone mice.

1.4. TGF-β and collagen synthesis

Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β) is a cytokine that regulates many cell-intrinsic processes that reprogram the tumor microenvironment. The basic processes of cell and tissue development, vasculogenesis, wound healing, and immunological homeostasis are all controlled by TGF-β1 [45]. TGF-β acts as an immunosuppressive cytokine that induces growth, differentiation, tolerance induction, and homeostasis of immune cells [46, 47]. Increased amounts of TGF-β and other anti-inflammatory cytokines are expressed by M2 macrophages. In fibroblast cocultured UtLM, an increased secretion of TGF-β1,3 was found, and immunoprecipitated TGF-β receptor I from cocultured UtLM cells showed elevated phosphoserine expression [48].

Findings from Hillege, Galli Caro [49] revealed that TGF-β acutely enhanced the expression of a subset of fibrosis-related genes, including CTGF and FGF-2, in both myoblasts and myotubes, which was then followed by an increase in Col1a1 expression. Pan, Chen [50] results showed that in cardiac fibroblasts, TGF-β1 increased COL1A1 mRNA expression and protein synthesis. When cells were exposed to 10 ng/mL of TGF-β1 for 48 hours, the expression of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and DNMT3a was considerably downregulated, and the overall DNMT activity was suppressed. The rat COL1A1 promoter’s DNA methylation percentage was significantly reduced after TGF-β1 treatment at numerous CpG sites and thus inhibiting DNMT1 and DNMT3a expressions as well as overall DNMT activity and subsequently increase collagen type I expression.

2. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are heterogeneous populations of immature myeloid cells that exhibit the capacity to inhibit both innate and adaptive immune responses. They are divided into two subtypes, polymorphonuclear (PMN-MDSCs) or granulocytic MDSCs, which morphologically and phenotypically resemble neutrophils, and monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs), which morphologically and phenotypically resemble monocytes [51]. Clinical research found that patients with solid tumors who had circulating and/or infiltrating MDSCs at the tumor site had a poor prognosis. MDSC removal could aid in reestablishing immunological surveillance [52].

Kim, Chu [53] showed that expression of programmed death ligand 1 increases MDSCs accumulation, promotes tumor progression by gastric epithelial cells. Lebrun, Lo Re [54] data showed that silica-treated mice’s M-MDSCs produced TGF-β1 and that resulted in which increased TIMP-1 release by lung fibroblasts. This inhibited collagen breakdown and facilitated lung fibrosis. In addition to their immunosuppressive effects, sB7H3-mediated disease progression may be influenced by TERT and B7H3-dependent MDSC recruitment/expansion from BM, which may trigger myofibroblast differentiation during pulmonary fibrosis [55]. Sun, Ni [56] found that by secreting S100A8/A9 and controlling FGF2-SOX9 signaling in fibroblasts as they age, G-MDSCs encourage cardiac fibrosis.

Key molecular mechanisms allow MDSCs to suppress immunological responses include the elevation of STAT3 expression, development of ER stress, production of arginase 1, and expression of S100A8/A9 [57] (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Effect of MDSCs on collagen synthesis.

2.1. STAT3 and collagen synthesis

An oncogene and latent transcription factor, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is triggered by a variety of cytokines and growth factors [58]. Papaioannou, Xu [59] mentioned that in human lung fibroblasts, collagen enhancer activation is not constrained by active STAT3. However, STAT3 activity must be over a particular threshold to enable activation of the COL1A2 enhancer and TGF-β signaling in fibroblasts. Chakraborty, Šumová [60] found that the interaction of JAK, SRC, c-ABL, and JNK kinases leads to STAT3 activation. The pro-fibrotic effects of TGF-β are less pronounced in fibroblasts lacking STAT3. In experimental animal models, skin fibrosis is reduced by pharmacological suppression of STAT3 or by STAT3-specific deletion. Heichler, Schmied [61] found that in colorectal carcinoma linked to colitis, inhibition of STAT3 activation in type I collagen-expressing fibroblasts may provide a feasible therapeutic target. Pedroza, To [62] mentioned that in mouse models of skin fibrosis, STAT3 inhibition with C188–9 reduced collagen deposition, myofibroblast accumulation, pro-fibrotic gene expression, and skin fibrosis. Additionally, they found that using C188–9 reduced in vitro dermal fibroblast production of fibrotic genes induced by IL-6 trans-signaling and TGF-β and that TGF-β caused STAT3 to become phosphotyrosylated in a way that was SMAD3 dependent.

A STAT3 inhibitor called HJC0123 works by lowering STAT3 phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity. HJC0123 therapy has been shown to inhibit HSC activation and proliferation, induced its cell cycle arrest, promoted its apoptosis, and downregulated ECM proteins fibronectin and type I collagen production. Additionally, HJC0123 boosted the production of IL-6 and inhibited the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 caused by TGF-β [63]. STAT3 also regulates the activity of lysyl oxidase (LOX), a copper-dependent monoamine oxidase whose major role is to covalently cross-link collagen in the ECM, making it one of the key mediators in ECM deposition [64]. Park, Yoon [65] found that keloid fibroblast proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis were severely inhibited by a JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor and a STAT3 siRNA. In vitro results from Matsui, Rhee [66] demonstrate that the response to IL-18 stimulation includes enhanced p-STAT3, SOCS3, α-SMA, collagen III expression, collagen synthesis, and TEC apoptosis; however, the reaction was considerably reduced in the presence of STAT3 inhibition.

2.2. Arginase 1 and collagen synthesis

Arginase 1 (ARG1), one of the main enzymes that metabolizes arginine, is typically found in the cytoplasm while its isoform ARG2 is typically found in the mitochondria [67]. L-arginine is converted into L-ornithine and urea by the enzyme ARG1, which is produced by MDSCs and TAMs, and is essential for ammonia detoxification in the liver [68]. An ARG1-induced reduction of L-arginine reduces TCR chain expression, prevents T cell differentiation, arrests the T cell cycle, and reduces cytokine production. As a result, increased T cell-mediated anti-tumor responses are inhibited by higher ARG1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. Tumor cells may promote the growth of ARG1-expressing cells, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and MDSCs, to elude immune surveillance [69].

Dias, Ciambarella [70] suggested that ARG1 helps with fibrogenesis in silicosis. Inactivating Arg1 in activated HSCs effectively reduced collagen synthesis but did not affect cell division. The downregulation of arginase-ornithine pathway expression following Tianlongkechuanling (TL) administration is a key mechanism and prospective treatment for pulmonary fibrosis using TL [71]. Grasemann, Dhaliwal [72] reported that treatment with amino-2-borono-6-hexanoic acid, an arginase inhibitor, stopped collagen deposition caused by bleomycin (BLM). In rat tracheal and lung fibroblasts cultured in a proline-free medium, Warnken, Haag [73] reported that inhibiting arginase reduced basal collagen I accumulation by about one-third and greatly attenuated the TGF-β1-induced increase in collagen accumulation.

2.3. S100A8/A9 and collagen formation

The Ca2+-binding proteins S100A8 and S100A9, also known as MRP8 and MRP14, respectively, are members of the S100 family [74]. Due to their stability, they frequently exist as heterodimers and seldom as homodimers. In neutrophils and monocytes, S100A8/A9 is constitutively expressed as a Ca2+ sensor, taking a role in cytoskeleton reorganization and arachidonic acid metabolism. S100A8/A9 is actively produced during inflammation and plays a crucial role in regulating the inflammatory response by encouraging leukocyte recruitment and triggering cytokine secretion [75].

Araki, Kinoshita [76] reported that S100A8/A9 play a direct role in fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis. Additionally, S100A8/A9 induced collagen synthesis by fibroblasts. In a mouse model of BLM-induced lung fibrosis, the anti-S100A8/A9 neutralizing antibody reduced the effects of S100A8/A9 on fibroblasts and slowed the progression of fibrosis.

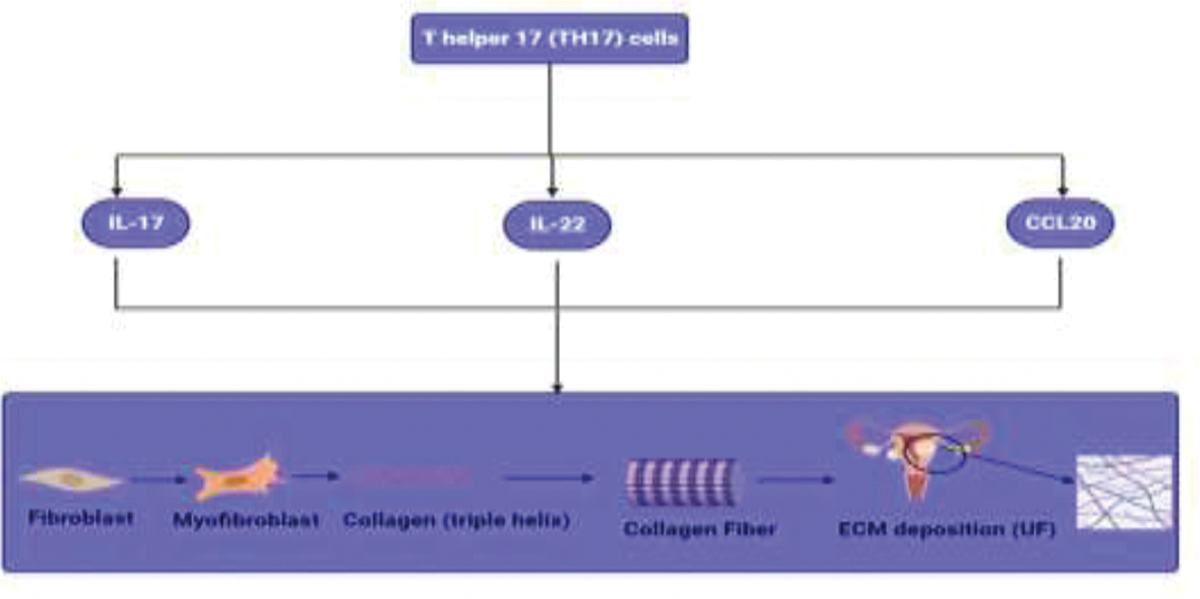

3. - T helper 17 (TH17) cells

Through the production of the cytokine IL-17, Th17 cells, a specific subset of CD4+ T cells, are crucial in triggering inflammation in autoimmune diseases and infections. Various human malignancies have been discovered to contain Th17 cells [77]. Th17 cells differ from other immune system cells in that they can secrete IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, and CCL20 [78]. TH17 were found to induce collagen synthesis and thus upregulation of UFs through secretion of IL-17, IL-22, and CCL20 (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Effect of TH17 on collagen synthesis. Here, Table 1 summarize our findings about role of immunosuppressive cells in ECM deposition

3.1. IL-17 and collagen synthesis

A class of cytokines called IL-17 is involved in both acute and long-term inflammatory responses. It has been suggested that IL-17 has a key role in the initiation and development of UF since studies have demonstrated that it has a considerable impact on collagen accumulation from assembly to accumulation to ECM. Two pathways are activated when IL-17 binds to its receptor: (1) the canonical pathway, which involves activating the NF-kB, MAPK, and CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) pathways, which activate downstream genes and proteins like pro-inflammatory genes and genes involved in tissue remodeling; and (2) the non-canonical pathway, which involves mRNA transcript stabilization.

Interleukin-17 improves the stability of CXCL1 mRNA and consequently CXCL1 expression. As a result, neutrophils are recruited and triggered inflammation [79]. Through lysyl oxidase enzyme activation, IL-17 was reported to promote collagen assembly in cardiac fibrosis [80]. Additionally, it was discovered that IL-17 enhanced the stemness features of tumors and increased hMSC proliferation [81]. In a mouse fibrosis model, it was discovered that Th17 cells increased fibroblast proliferation, cytokine production, and induced skin and lung fibrosis [82]. Besides, IL-17A changed the fibroblast transcription model to tumorigenic phenotype [83].

3.2. IL-22 and collagen synthesis

A crucial regulator of epithelial homeostasis is the cytokine interleukin-22 (IL-22). IL-22 also contributed to regulation of epithelial cell development and permeability, formation of mucus and antimicrobial proteins (AMPs), and complement synthesis that has been linked to epithelial barrier [84].

In cultured normal human dermal fibroblasts, IL-22 dramatically boosted the expression of type I collagen protein without affecting its mRNA levels [85]. Liu, Shang [86] found that through the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway, the IL-22/IL-22R1 signaling pathway induced MRC-5 cell proliferation and the production of COL11 and COL12 in MRC-5 cells. Wu, Tan [87] reported that in cardiac fibroblasts treated with TGF-β1, in vitro recombinant mouse IL-22 therapy increased the production of α-SMA, collagen I, and collagen III. Type I collagen and MMP-1, which are expressed in wounds involving keratinocytes, may be mediated by IL-22, which may promote scarless healing [88].

3.3. CCL20 and collagen synthesis

The sole chemokine known to interact with CC chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6) is CCL20. The ligand-receptor pair CCL20-CCR6 plays a role at skin and mucosal surfaces under homeostatic and inflammatory conditions, as well as in pathology, including cancer and rheumatoid arthritis. It is responsible for the chemoattraction of immature dendritic cells (DC), effector/memory T-cells, and B-cells [89].

Recombinant CCL20 promoted the expression of the collagen Type I alpha 2 gene from human skin fibroblasts. On the other hand, collagen type I gene and protein expression were significantly decreased when CCL20’s siRNA gene was knocked down [90]. Han, Zou [91] reported that lead acetate-induced fibroblast proliferation, hydroxyproline levels, the synthesis of TGF-β, and the expression of ECM-related proteins (Collagen I and fibronectin) which were all decreased by CCL20 knockdown. Beider, Abraham [92] showed that elevated dosages of CCL20 considerably increased cell adherence to collagen type I while just modestly increasing cell adhesion to fibronectin.

Conclusion

Despite the high prevalence of uterine fibroids and their health and economic consequences, little research has discussed the possible immunological causes of the disease. Immune reprogramming is one of the possible causes of UF formation through inducing collagen synthesis. The increase in M2 macrophage, MDSCs, and TH17 are among the most possible causes for inducing collagen synthesis and thus UF formation. This review represents a new era towards more investigations of the change in the UF immune microenvironment and also possible targeting approaches, through immunomodulation, that leads to better prognosis of UF cases.

Figure 1:

Effect of Different immune cells on ECM deposition and UF progression

Table 1:

Role of immunosuppressive cells in collagen deposition

| Cell | Mediator | Pathway affected | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| M2 Macrophages | IL-4 | Activation of myofibroblasts and inducing collagen synthesis and release (STAT-6 dependent) | [23] |

| Stimulation prostate stromal fibroblasts to produce collagen mRNA and protein (JAK/STAT dependent) | [27] | ||

| Stimulated the synthesis of fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and STAT6 | [24] | ||

| Induction of lysyl hydroxylase 2 (LH2) | [25] | ||

| Enhanced collagen I synthesis | [26] | ||

| IL-10 | Increase in fibroblast activation (proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis) | [32] | |

| Increased cell division, the production of collagen type I, the appearance of positive stress fibers for smooth muscle actin, and contraction of collagen gel | [33] | ||

| Induction of pro-fibrotic phenotypic including cell proliferation, collagen type I synthesis, α-SMA positive stress fibers, and collagen gel contraction (STAT3 dependent) | [33] | ||

| Fibroblast activation | [36] | ||

| IL-13 | Increased collagen type-1 formation (TGF-β1 and MMP-2 dependent) | [39] | |

| Increased collagen expression (STAT6-dependent) | [40] | ||

| HSCs Stimulation and increased collagen synthesis | [41] | ||

| Inhibition of fibroblast MMP synthesis and down- | |||

| regulates matrix degradation, resulting in excessive collagen deposition. | [42] | ||

| IL-13 dose- and time-dependently increased collagen synthesis which was countered by inhibiting the JAK/STAT6 signal pathway. | [43] | ||

| Promotion of collagen production | [44] | ||

| TGF-β1 | Enhancement of CTGF and FGF-2 expression, in both myoblasts and myotubes, which was then followed by an increase in Col1a1 expression. | [49] | |

| Increased COL1A1 mRNA expression and protein synthesis Inhibition of DNMT1 and DNMT3a expressions as well as overall DNMT activity and subsequently increase collagen type I expression. |

[50] | ||

| MDSCs | STAT3 | Increased collagen deposition, myofibroblast accumulation, pro-fibrotic gene expression, and skin fibrosis. Increased IL-6 trans-signaling and TGF-β profibrotic effects. |

[62] |

| Activation of HSC proliferation, inhibition of its cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and upregulation of ECM proteins fibronectin and type I collagen production. Stimulation of Smad2/3 phosphorylation caused by TGF-β |

[63] | ||

| Enhancement of lysyl oxidase (LOX) activity and ECM deposition | [64] | ||

| Enhancement of α-SMA, collagen III expression, collagen synthesis | [66] | ||

| Enhanced fibroblast proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis | [65] | ||

| Arginase 1 | Activation of HSCs and enhancement of collagen synthesis | [71] | |

| Enhancement of collagen deposition | [72] | ||

| Enhancement of collagen I accumulation and enhancement of TGF-β1-induced increase in collagen accumulation. | [73] | ||

| S100A8/A9 | Fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, enhanced collagen synthesis by fibroblasts. | [76] | |

| TH17 | IL-17 | Improvement of CXCL1 mRNA stability and consequently CXCL1 expression and thus neutrophils recruitment and inflammation | [79] |

| Lysyl oxidase enzyme activation | [80] | ||

| Enhancement of tumors stemness and increased hMSC proliferation | [81] | ||

| Increased fibroblast proliferation and cytokine production | [82] | ||

| Changed fibroblast transcription model to tumorigenic phenotype | [83] | ||

| IL-22 | Boosting the expression of type I collagen protein. | [85] | |

| Induction of production of COL11 and COL12 | [86] | ||

| Increased α-SMA, collagen I, and collagen III production | [87] | ||

| Increased Type I collagen and MMP-1 production | [88] | ||

| CCL-20 | Promotion of collagen Type I alpha 2 gene expression | [90] | |

| Fibroblast proliferation, hydroxyproline levels, the synthesis of TGF-β, and the expression of ECM-related proteins (Collagen I and fibronectin) | [91] | ||

| Increased cell adherence to collagen type I while just modestly increasing cell adhesion to fibronectin. | [92] |

Highlights.

UF pathogenesis is mainly associated with ECM accumulation

The process of ECM accumulation is partly immune mediated

Immunosuppressive cells and their secretory cytokines accelerate collagen deposition which worse UF pathogenesis

- Funding:

This work was supported by NIH grant 1R01HD094380.

Mostafa Borahay, MD, PhD

Associate Professor

Director, Division of General Obstetrics and Gynecology, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD

Dr. Borahay is a Physician Scientist. He is the Principal Investigator on 3 NIH R01 grants and co-Investigator on several other grants.

He is the PI on NIH grants R01HD094380 titled Mechanisms of Action(s) of Simvastatin in Uterine Leiomyoma; R01HD111243 titled Role of Senescent Cells in Uterine Fibroid Pathogenesis; and 3R01HD094380–04S1 titled COVID-19 Vaccination and Menstruation

His lab focuses on understanding the pathogenesis of uterine fibroids and developing novel therapeutics. Dr. Borahay has more than 90 peer-reviewed papers, published 2 gynecology textbooks, is Associate Editor at the American Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynecology and is a member of NIH study section.

Footnotes

- Competing interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart EA, et al. , Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016. 2: p. 16043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Q, et al. , Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Developmental Origin, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Endocr Rev, 2022. 43(4): p. 678–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam MS, et al. , Extracellular matrix in uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis: a potential target for future therapeutics. Hum Reprod Update, 2018. 24(1): p. 59–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao H, Sin TK, and Zhang G, Activin A induces tumorigenesis of leiomyoma via regulation of p38β MAPK-mediated signal cascade. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2020. 529(2): p. 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordeiro Mitchell CN, et al. , Mechanical stiffness augments ligand-dependent progesterone receptor B activation via MEK 1/2 and Rho/ROCK-dependent signaling pathways in uterine fibroid cells. Fertil Steril, 2021. 116(1): p. 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manti S and Parisi GF, Type 2 inflammation in cystic fibrosis: New insights. 2022. 33 Suppl 27(Suppl 27): p. 15–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gieseck RL, Wilson MS, and Wynn TA, Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2018. 18(1): p. 62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosser DM, Hamidzadeh K, and Goncalves R, Macrophages and the maintenance of homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol, 2021. 18(3): p. 579–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirayama D, Iida T, and Nakase H, The Phagocytic Function of Macrophage-Enforcing Innate Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci, 2017. 19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yunna C, et al. , Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur J Pharmacol, 2020. 877: p. 173090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zannotti A, et al. , Macrophages and Immune Responses in Uterine Fibroids. Cells, 2021. 10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laganà AS, et al. , Evaluation of M1 and M2 macrophages in ovarian endometriomas from women affected by endometriosis at different stages of the disease. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2020. 36(5): p. 441–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji X, et al. , Effect of tumor-associated macrophages on the pyroptosis of breast cancer tumor cells. Cell Communication and Signaling, 2023. 21(1): p. 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oshi M and Tokumaru Y, M1 Macrophage and M1/M2 ratio defined by transcriptomic signatures resemble only part of their conventional clinical characteristics in breast cancer. 2020. 10(1): p. 16554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, et al. , Tumor-associated macrophages of the M1/M2 phenotype are involved in the regulation of malignant biological behavior of breast cancer cells through the EMT pathway. 2022. 39(5): p. 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macciò A, et al. , Role of M1-polarized tumor-associated macrophages in the prognosis of advanced ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Flamme AC, et al. , Type II-activated murine macrophages produce IL-4. PLoS One, 2012. 7(10): p. e46989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ul-Haq Z, Naz S, and Mesaik MA, Interleukin-4 receptor signaling and its binding mechanism: A therapeutic insight from inhibitors tool box. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, 2016. 32: p. 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosna O, et al. , Th1/Th2 cytokine gene polymorphisms in patients with uterine fibroid. Folia Biol (Praha), 2010. 56(5): p. 206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orciani M and Caffarini M, Chronic Inflammation May Enhance Leiomyoma Development by the Involvement of Progenitor Cells. 2018. 2018: p. 1716246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krsteski J, et al. , Polymorphism of the IL13 gene may be associated with Uterine leiomyomas in Slovenian women. Balkan J Med Genet, 2016. 19(2): p. 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Măluţan AM, et al. , Serum anti-inflammatory cytokines for the evaluation of inflammatory status in endometriosis. J Res Med Sci, 2015. 20(7): p. 668–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoudjehane L, et al. , Interleukin-4 induces the activation and collagen production of cultured human intrahepatic fibroblasts via the STAT-6 pathway. Lab Invest, 2008. 88(9): p. 973–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang H, et al. , The IL-4 receptor α has a critical role in bone marrow-derived fibroblast activation and renal fibrosis. Kidney Int, 2017. 92(6): p. 1433–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knipper Johanna A., et al. , Interleukin-4 Receptor α Signaling in Myeloid Cells Controls Collagen Fibril Assembly in Skin Repair. Immunity, 2015. 43(4): p. 803–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimoto R, et al. , Effect of IL-4 and IL-13 on collagen production in cultured LI90 human hepatic stellate cells. Liver International, 2005. 25(2): p. 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Arcy Q, et al. , The IL-4/IL-13 signaling axis promotes prostatic fibrosis. 2022. 17(10): p. e0275064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ip WKE, et al. , Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science, 2017. 356(6337): p. 513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zannotti A, et al. , Macrophages and Immune Responses in Uterine Fibroids. Cells, 2021. 10(5): p. 982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porro C, Cianciulli A, and Panaro MA, The Regulatory Role of IL-10 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saraiva M, Vieira P, and O’Garra A, Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J Exp Med, 2020. 217(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung M, et al. , IL-10 improves cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction by stimulating M2 macrophage polarization and fibroblast activation. 2017. 112(3): p. 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuzaki S, Pouly JL, and Canis M, IL-10 is not anti-fibrotic but pro-fibrotic in endometriosis: IL-10 treatment of endometriotic stromal cells in vitro promotes myofibroblast proliferation and collagen type I protein expression. Hum Reprod, 2023. 38(1): p. 14–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang K-K, et al. , IL-27 triggers IL-10 production in Th17 cells via a c-Maf/RORγt/Blimp-1 signal to promote the progression of endometriosis. Cell Death & Disease, 2017. 8(3): p. e2666–e2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang HL, et al. , The crosstalk between endometrial stromal cells and macrophages impairs cytotoxicity of NK cells in endometriosis by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β. Reproduction, 2017. 154(6): p. 815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharyya A, et al. , IL10 trains macrophage profibrotic function after lung injury. 2022. 322(3): p. L495–l502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao H, et al. , IL-13/STAT6 signaling plays a critical role in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(38): p. 61183–61198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, et al. , Elevated serum IL-13 level is associated with increased Treg cells in tumor microenvironment and disease progression of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. 2023. 41(2): p. 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Firszt R, et al. , Interleukin-13 induces collagen type-1 expression through matrix metalloproteinase-2 and transforming growth factor-β1 in airway fibroblasts in asthma. Eur Respir J, 2014. 43(2): p. 464–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Reilly S, et al. , IL-13 mediates collagen deposition via STAT6 and microRNA-135b: a role for epigenetics. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 25066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugimoto R, et al. , Effect of IL-4 and IL-13 on collagen production in cultured LI90 human hepatic stellate cells. Liver Int, 2005. 25(2): p. 420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey JR, et al. , IL-13 promotes collagen accumulation in Crohn’s disease fibrosis by down-regulation of fibroblast MMP synthesis: a role for innate lymphoid cells? PLoS One, 2012. 7(12): p. e52332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, et al. , PPAR-γ inhibits IL-13-induced collagen production in mouse airway fibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol, 2014. 737: p. 133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cardilo-Reis L, et al. , Interleukin-13 protects from atherosclerosis and modulates plaque composition by skewing the macrophage phenotype. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 2012. 4(10): p. 1072–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Streel G and Lucas S, Targeting immunosuppression by TGF-β1 for cancer immunotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol, 2021. 192: p. 114697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheng J, Chen W, and Zhu H-J, The immune suppressive function of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in human diseases. Growth Factors, 2015. 33(2): p. 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abd El-Fattah EE and Zakaria AY, Metformin modulate immune fitness in hepatocellular carcinoma: Molecular and cellular approach. International Immunopharmacology, 2022. 109: p. 108889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore AB, et al. , Human uterine leiomyoma-derived fibroblasts stimulate uterine leiomyoma cell proliferation and collagen type I production, and activate RTKs and TGF beta receptor signaling in coculture. Cell Commun Signal, 2010. 8: p. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hillege MMG, et al. , TGF-β Regulates Collagen Type I Expression in Myoblasts and Myotubes via Transient Ctgf and Fgf-2 Expression. Cells, 2020. 9(2): p. 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan X, et al. , Transforming growth factor β1 induces the expression of collagen type I by DNA methylation in cardiac fibroblasts. PLoS One, 2013. 8(4): p. e60335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh C-C, et al. , Administration of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells ameliorates renal fibrosis in diabetic mice. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2018. 9(1): p. 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Law AMK, Valdes-Mora F, and Gallego-Ortega D, Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as a Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Cells, 2020. 9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim W, et al. , PD-1 Signaling Promotes Tumor-Infiltrating Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Gastric Tumorigenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology, 2021. 160(3): p. 781–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lebrun A, et al. , CCR2(+) monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (M-MDSCs) inhibit collagen degradation and promote lung fibrosis by producing transforming growth factor-β1. 2017. 243(3): p. 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu T, et al. , B7H3-dependent myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment and activation in pulmonary fibrosis. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 901349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun S-N, et al. , G-MDSCs promote aging-related cardiac fibrosis by activating myofibroblasts and preventing senescence. Cell Death & Disease, 2021. 12(6): p. 594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Veglia F, Sanseviero E, and Gabrilovich DI, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2021. 21(8): p. 485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim CP, et al. , Stat3 contributes to keloid pathogenesis via promoting collagen production, cell proliferation and migration. Oncogene, 2006. 25(39): p. 5416–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papaioannou I, et al. , STAT3 controls COL1A2 enhancer activation cooperatively with JunB, regulates type I collagen synthesis posttranscriptionally, and is essential for lung myofibroblast differentiation. Mol Biol Cell, 2018. 29(2): p. 84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chakraborty D, et al. , Activation of STAT3 integrates common profibrotic pathways to promote fibroblast activation and tissue fibrosis. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heichler C, et al. , Targeting STAT3 Signaling in COL1+ Fibroblasts Controls Colitis-Associated Cancer in Mice. Cancers (Basel), 2022. 14(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedroza M, et al. , Role of STAT3 in skin fibrosis and transforming growth factor beta signalling. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2018. 57(10): p. 1838–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nunez Lopez O, et al. , STAT3 Inhibition Suppresses Hepatic Stellate Cell Fibrogenesis: HJC0123, a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Liver Fibrosis. RSC Adv, 2016. 6(102): p. 100652–100663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang X, et al. , Lysyl oxidase promotes renal fibrosis via accelerating collagen cross-link driving by β-arrestin/ERK/STAT3 pathway. Faseb j, 2022. 36(8): p. e22427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park G, et al. , Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses collagen production and proliferation in keloid fibroblasts via inhibition of the STAT3-signaling pathway. J Invest Dermatol, 2008. 128(10): p. 2429–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsui F, et al. , IL-18 induces profibrotic renal tubular cell injury via STAT3 activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 2013. 305(7): p. F1014–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Menjivar RE, et al. , Arginase 1 is a key driver of immune suppression in pancreatic cancer. Elife, 2023. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aaboe Jørgensen M, et al. , Arginase 1–Based Immune Modulatory Vaccines Induce Anticancer Immunity and Synergize with Anti–PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Immunology Research, 2021. 9(11): p. 1316–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lorentzen CL, et al. , Arginase-1 targeting peptide vaccine in patients with metastatic solid tumors - A phase I trial. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 1023023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dias DF, et al. , Arginase 1 contributes to fibrogenesis in the lungs of silica-challenge mice. European Respiratory Journal, 2015. 46(suppl 59): p. PA940. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang L, et al. , Tianlongkechuanling Inhibits Pulmonary Fibrosis Through Down-Regulation of Arginase-Ornithine Pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2021. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grasemann H, et al. , Arginase inhibition prevents bleomycin-induced pulmonary hypertension, vascular remodeling, and collagen deposition in neonatal rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015. 308(6): p. L503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Warnken M, et al. , Species differences in expression pattern of arginase isoenzymes and differential effects of arginase inhibition on collagen synthesis in human and rat pulmonary fibroblasts. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 2010. 381(4): p. 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pruenster M, et al. , S100A8/A9: From basic science to clinical application. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2016. 167: p. 120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang S, et al. , S100A8/A9 in Inflammation. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Araki K, et al. , The heterodimer S100A8/A9 is a potent therapeutic target for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Mol Med (Berl), 2021. 99(1): p. 131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang SH, T helper 17 (Th17) cells and interleukin-17 (IL-17) in cancer. Arch Pharm Res, 2019. 42(7): p. 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bailey SR, et al. , Th17 Cells in Cancer: The Ultimate Identity Crisis. Frontiers in Immunology, 2014. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Korbecki J, et al. , CXCL1: Gene, Promoter, Regulation of Expression, mRNA Stability, Regulation of Activity in the Intercellular Space. 2022. 23(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu M, et al. , Th17/Treg imbalance modulates rat myocardial fibrosis and heart failure by regulating LOX expression. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2020. 230(3): p. e13537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang H, et al. , IL-17 stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells: implications for bone remodeling. Cell Death Differ, 2009. 16(10): p. 1332–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lei L, et al. , Th17 cells and IL-17 promote the skin and lung inflammation and fibrosis process in a bleomycin-induced murine model of systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2016. 34 Suppl 100(5): p. 14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mucciolo G, et al. , IL17A critically shapes the transcriptional program of fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer and switches on their protumorigenic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2021. 118(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Keir M, et al. , The role of IL-22 in intestinal health and disease. J Exp Med, 2020. 217(3): p. e20192195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sawamura S, et al. , Regulatory mechanisms of collagen expression by interleukin-22 signaling in scleroderma fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci, 2018. 90(1): p. 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu J, Shang B, and Bai J, IL-22/IL-22R1 promotes proliferation and collagen synthesis of MRC-5 cells via the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway and regulates airway subepithelial fibrosis. Exp Ther Med, 2020. 20(3): p. 2148–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu Y, et al. , Interleukin-22 is elevated in the atrium and plasma of patients with atrial fibrillation and increases collagen synthesis in transforming growth factor-β1-treated cardiac fibroblasts via the JNK pathway. Exp Ther Med, 2020. 20(2): p. 1012–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu R, et al. , IL-22 mediates the oral mucosal wound healing via STAT3 in keratinocytes. Arch Oral Biol, 2016. 72: p. 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kadomoto S, Izumi K, and Mizokami A, The CCL20-CCR6 Axis in Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bandow K, et al. , CC chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20) positively regulates collagen type I production in 3D skin equivalent tissues. Exp Dermatol, 2023. 32(4): p. 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Han L, Zou Y, and Yu C, Targeting CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 20 by miR-143–5p alleviate lead poisoning-induced renal fibrosis by regulating interstitial fibroblasts excessive proliferation and dysfunction. Bioengineered, 2022. 13(4): p. 11156–11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Beider K, et al. , Interaction between CXCR4 and CCL20 pathways regulates tumor growth. PLoS One, 2009. 4(4): p. e5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]