SUMMARY

Neurodegeneration is a protracted process involving progressive changes in myriad cell types that ultimately result in the death of vulnerable neuronal populations. To dissect how individual cell types within a heterogeneous tissue contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of a neurodegenerative disorder, we performed longitudinal single-nucleus RNA sequencing of mouse and human spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) cerebellar tissue, establishing continuous dynamic trajectories of each cell population. Importantly, we defined the precise transcriptional changes that precede loss of Purkinje cells and, for the first time, identified robust early transcriptional dysregulation in unipolar brush cells and oligodendroglia. Finally, we applied a deep learning method to predict disease state accurately and identified specific features that enable accurate distinction of wild-type and SCA1 cells. Together, this work reveals new roles for diverse cerebellar cell types in SCA1 and provides a generalizable analysis framework for studying neurodegeneration.

Keywords: spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, SCA1, ataxin-1, neurodegeneration, single-nucleus RNA sequencing, Purkinje cell, unipolar brush cells, oligodendrocyte progenitor cell, oligodendrocyte, machine learning

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb:

In neurodegeneration, vulnerable neuronal populations are highly influenced by concomitant changes in surrounding cells, including glia. Here, Tejwani et al. performed longitudinal single-nucleus profiling of the mouse and human SCA1 cerebellum, which elucidated the progressive dysregulation of Purkinje cells and revealed early transcriptional changes in oligodendroglia and unipolar brush cells.

INTRODUCTION

SCA1 is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder in the family of polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases and is caused by expansion of the CAG trinucleotide repeat tract in ATXN1, encoding the ataxin-1 protein.1 Although ATXN1 is ubiquitously expressed,2 the Purkinje cells (PCs) display the most marked degeneration in the SCA1 cerebellum,3 and thus have been the primary focus of most studies. Evidence from animal models suggests that profound cerebellar circuit dysfunction precedes overt PC loss,4 which can be attributed to PC-intrinsic changes or perturbations in the many cell types that directly or indirectly modulate PC activity. Recent studies have suggested the involvement of additional cerebellar cell types in disease;5–8 however, the effects of the SCA1 mutation on other populations are not well-understood and are further obscured by their low relative abundance compared to cerebellar granule cells.

In SCA1 and other neurodegenerative diseases, efforts to interrogate the roles of individual cell types in disease have primarily relied on the development of conditional animal models by restricting mutant gene expression to a candidate cell type, which in the case of late-onset neurodegenerative diseases, can be extremely laborious and time-consuming. In recent years, droplet-based single-cell sequencing has emerged as a scalable tool for profiling many cells of heterogenous tissues,9,10 and several groups have applied this to human post-mortem samples from patients with neurodegenerative disorders.11–22 While these studies have revealed some insights into how certain cell types are unexpectedly perturbed, they reflect the end-stage transcriptional changes in surviving populations of cells, falling short of accurately describing the progressive course of disease, which occurs over decades in humans. Additionally, the mechanisms through which various cell types contribute to disease are constantly changing. Therefore, approaches geared towards elucidating the molecular dynamics throughout a disease process at a single-cell resolution are desirable. Here, we integrate cutting-edge genomics and analytical approaches to examine the complex and dynamic interplay between diverse cell populations in the SCA1 cerebellum over time.

RESULTS

Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) of the SCA1 cerebellum

To profile the transcriptional dynamics of the SCA1 cerebellum comprehensively throughout the disease at a single-cell level, we performed snRNA-seq of 10 control (CTRL) and 10 SCA1 primary human post-mortem cerebellar cortex tissues (Table S1), and 15 SCA1 knock-in (SCA1 KI; Atxn1154Q/+) and 15 wild-type (WT) littermate control mice at five timepoints (5, 12, 18, 24, and 30 weeks of age) (Figure 1A). We selected these timepoints to capture all major processes throughout disease, from the early onset of behavioral deficits (5–6 weeks) to eventual cell loss and premature lethality, which typically begins around 32 weeks of age.4,23 Following removal of cells that did not meet quality control criteria (see STAR★Methods), our snRNA-seq yielded datasets of 237,554 and 313,447 high-quality single-nucleus transcriptomes from human and mouse, respectively (Figure 1A; Table S1). Cell type labels were assigned to pre-clusters based on expression of established marker genes, as well as novel markers from a recently published single-cell atlas of the adult WT mouse cerebellum,24 and pre-clusters with similar identities were merged when appropriate (Figures 1B–1E; Figures S1 and S2; Table S1).

Figure 1. Single-cell transcriptional profiling of the SCA1 human and mouse cerebellum.

(A) Schematic pipeline of SCA1 snRNA-seq and analysis of human post-mortem (n=20 human) and mouse (n=30 mice) cerebellum.

(B and C) UMAP embeddings of 237,554 human (B) and 313,447 mouse (C) single-nucleus transcriptomes. Nuclei from 20 human post-mortem (CTRL, n=10; SCA1, n=10) and 30 mouse (WT, n=3; SCA1, n=3 per timepoint; timepoints= 5, 12, 18, 24, 30 weeks) tissues were sequenced.

(D and E) Normalized violin plots showing expression of cell type-specific marker genes for each human (D) and mouse (E) cluster used for cell type annotation.

(F and G) Relative proportions of each cell type within each genotype for the human (F) and mouse (G) datasets.

(H) Dot plot displaying mean scaled expression of previously reported effectors of SCA1 toxicity (rows) in WT mouse cerebellar cell types (columns) averaged over time.

(I) Heatmap displaying mean expression profiles of 238 ataxin-1 physical interactors (rows) in WT mouse cerebellar cell types (columns) averaged over time.

(J and K) Number of down-regulated, up-regulated, and total differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the human (J) and mouse (K) snRNA-seq datasets.

See also Figures S1–S7, and Tables S1–S10.

The resource presented here describes the single-nuclei transcriptomes of 13 human and 14 mouse clusters that represent the major cell types of the cerebellum including granule cells (GC), deep cerebellar nuclei neurons (DCN), unipolar brush cells (UBC), Purkinje cells (PC), three classes of GABAergic interneurons including two molecular layer interneuron populations (MLI1, MLI2) and Golgi cells (GoC), astrocytes (AS), Bergmann glia (BG), oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC), oligodendrocytes (OL), microglia (MG), pericytes (PER), and endothelial cells (END). Relative proportions of cells and sequencing quality were largely comparable across genotypes in both the human and mouse datasets (Figures 1F and 1G; Figures S3A–S3I).

Expression networks of ataxin-1 interactors

Ataxin-1 is ubiquitously expressed and serves key functions as a transcriptional co-regulator and splicing co-factor through its interactions with various proteins.25 In SCA1, the majority of gain-of-function pathogenic changes are thought to be mediated through altered incorporation of polyQ-expanded ataxin-1 into its native protein complexes,26–28 which typically depends on post-translational modification of ataxin-1.26,27,29–32 Although several key protein interactors of ataxin-1 have been demonstrated to be central to PC pathology, it is unclear if these same molecular mechanisms are responsible for dysfunction of other cerebellar cell types, as many of the studies investigating these genetic interactions have relied on constitutive whole-body deletion of putative mediators in all cell types. Thus, we aimed to use our snRNA-seq dataset to determine the extent to which various protein interactors or reported disease modifiers could potentially influence gene expression across the heterogenous cell types of the cerebellum.

We hypothesized that for a particular protein interactor to contribute to cell-autonomous pathogenic changes in a given cell type, its simultaneous co-expression with ATXN1 in the same cell is obligatory. Therefore, we first examined the cell type-specific expression of previously described effectors of polyQ-expanded ataxin-1 pathogenic functions, including genes encoding proteins involved in transcriptional regulation,26,33–38 protein levels and localization,30,39–43 splicing factors,27,32 and others.44–48 This analysis revealed that although many previously reported mediators of ataxin-1 toxicity are expressed at high levels in PCs, many are also robustly expressed by other cell types of the mouse and human cerebellum (Figure 1H; Figure S3J). For example, RORα and co-activator Tip60 (encoded by gene Kat5) are expressed at comparable or higher levels in various inhibitory interneuron populations (MLI1, MLI2, GoC) as PCs in both the mouse and human cerebellum, suggesting this complex may similarly contribute to gene expression changes in these cells as previously shown for PCs in a PC-specific transgenic model of SCA1 (SCA1 B05).35 On the other hand, although reduction of Nlk and Msk1 (encoded by gene Rps6ka5) may ameliorate SCA1 deficits through direct modulation of ataxin-1 phosphorylation in PCs,40,42 reduction of proteins like Pak1 may confer partial protection to SCA1 phenotypes through alternate mechanisms in other cell types,43 as its expression is higher in these other populations than in PCs (Figure 1H). Extension of this analysis to a broader set of transcripts encoding over 200 ataxin-1 physical interactors49 revealed several groups with the most similar expression profiles, including a group of interneuron subtypes (UBC, MLI1, MLI2, GoC) and DCN neurons, and an astroglial group (AS, BG), with distinct interactor expression profiles in each of the other cell types (Figure 1I), suggesting that the primary molecular mechanisms governing pathogenesis in different cell types may be distinct and dependent on co-expression patterns of these interactors with ataxin-1 (Table S2). Importantly, although mRNA expression profiles of putative mediators of mutant ataxin-1 toxicity across the heterogenous cerebellum may be useful for future targeted investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying cell type-specific gene expression changes in SCA1, additional post-transcriptional modifications that affect interactor protein levels, localization, and function must also be considered.

Differential gene expression in the SCA1 cerebellum

To identify cell type-specific gene expression changes between WT/CTRL and SCA1, we first performed differential gene expression analyses for all cell types, subsampling the data to control for differences in the number of nuclei across genotypes and timepoints. Because we aimed to broadly describe how the diverse populations of cerebellar neurons and glia are affected in SCA1, we merged pre-clusters belonging to the same cell type to perform differential expression analyses across genotypes for each major cell type. As a result, and due to the distributional nature of heterogenous gene expression across single nuclei within a merged population, we not only calculated the fold-change in mean expression between groups, but also computed the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) between genotypes for each gene in each cell type, as this approach retained information regarding both the magnitude of change and the proportion of cells undergoing alterations.50

We identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in individual cell types at each timepoint, with different cell types having different numbers of DEGs across the discrete timepoints (Figures 1J and 1K; Figure S4; Tables S3–S7). The timepoints sampled from the SCA1 KI mouse span the course of disease, from the onset of mild motor behavioral impairments (5 weeks) through the late-stage neuropathological changes (30 weeks) prior to premature lethality resulting from bulbar dysfunction. Examination of the number of DEGs in each cell type at discrete timepoints along disease progression revealed several key pieces of information. First, UBCs had the greatest number of DEGs at early timepoints immediately prior to the onset of behavioral deficits (Figure 1K). Overall, the 24-week timepoint had the highest number of DEGs averaged across all cell types in the mouse dataset (Figure 1K). Between the different cell types, the UBC, PC, OPC, and MG clusters displayed the highest number of DEGs averaged over time (Figure 1K). Because of their high number of DEGs over time (Figure 1K; Tables S3–S6), we focused on analyzing the UBC, PC, and OPC/OL clusters in greater detail.

UBC gene expression is highly dysregulated during early disease

As described above, SCA1 is characterized by early behavioral deficits that precede cell loss and degeneration. Although we observed differential gene expression in all cell types of the cerebellum at early stages, UBCs, an excitatory glutamatergic interneuron population, displayed the greatest dysregulation (Figure 1K). Intriguingly, UBCs are enriched in cerebellar lobules IX and X,51 the region that undergoes the earliest atrophy in SCA1 patients,52,53 suggesting a potential contribution to regional vulnerability and early SCA1 phenotypes. In the cerebellar circuitry, UBCs transform and amplify synaptic input from a single mossy fiber via its numerous connections with GCs or other UBCs,54,55 and this transformation via altered glutamatergic signaling underlies diverse temporal representation of synaptic inputs.56 Historically, UBCs have been broadly classified into mGluR1α/Trpc3-positive “ON” or calretinin-positive “OFF” UBC subtypes, referring to exclusive protein immunoreactivity and their firing activity in response to glutamatergic input.57–60 Recently, however, advances in transcriptional profiling of UBCs have revealed that rather than being functionally and molecularly discrete subpopulations, cerebellar UBCs display continuous molecular variation across subtypes,24,61 which has been suggested to relate to a continuum of functional properties through which cells can display biphasic physiological responses.

To explore the identities of the UBCs captured by our snRNA-seq approach, we first examined expression of reported UBC subpopulation markers in our mouse dataset (Figures S5A–S5C). This analysis confirmed the inverse graded expression of ON UBC markers Grm1 (encoding mGluR1α) and Plcb4, and OFF UBC markers Calb2 (encoding calretinin) and Plcb1 mRNA across the continuous UBC population (Figures S5B and S5C).24 Expression of these marker genes more accurately segregated UBC subclusters than age or genotype labels did (Figures S5D–S5F); therefore, cells were assigned ON or OFF labels (based on marker gene expression) for downstream analyses. To determine additional genes that can be used to discriminate between subsets of UBCs, we performed differential gene expression analyses between ON and OFF UBC subclusters, which revealed several novel markers for ON (e.g. Ntng1, Cdh18, and Slc24a2) and OFF UBCs (e.g. Nrg1, Fam155a, and Sgcd) (Figures S5G and S5H; Table S8). Similar to established UBC marker genes,24 these genes displayed graded transcript expression levels across the entire UBC cluster. Whether cells with intermediate expression of ON- and OFF-enriched marker genes display intermediate functional properties remains to be determined.

We next aimed to interrogate genotype-dependent differences in UBCs in SCA1. Although transcript levels of marker genes were continuous across the UBC cluster, protein immunoreactivity of Trpc3 and calretinin was completely non-overlapping (Figure S5I). Therefore, we first assessed numbers of Trpc3-positive (predominantly ON) and calretinin-positive (predominantly OFF) UBCs in the SCA1 cerebellum. Interestingly, the number of Tbr2-positive total UBCs, calretinin-positive OFF UBCs, and Trpc3-positive ON UBCs were all decreased in SCA1 at early stages (Figures S5J–S5M). Additionally, although gene ontology (GO) analysis of UBC DEGs over time revealed dynamic enrichment in different pathways over the course of disease, there was an enrichment in changes related to glutamate receptor signaling that emerged at early timepoints and persisted throughout disease (Figures S6A and S6B; Table S9), suggesting that changes in responsiveness to mossy fiber excitatory inputs may occur in SCA1. Electrophysiological analysis of UBCs at early timepoints revealed no significant alterations in intrinsic firing patterns at baseline (Figures S6C and S6D). Furthermore, pre-synaptic vGlut2 levels (likely from mossy fiber terminals) onto ON or OFF UBCs were unchanged in 12-week SCA1 mice (Figures S6E and S6F). Collectively, these data suggest that although overt functional changes in baseline electrophysiological properties and connectivity between UBCs and synaptic partners were not observed in SCA1 KI mice, altered UBC numbers may contribute to motor behavioral deficits, consistent with a previous report that loss of specific UBCs can lead to early ataxia-like behaviors in mice.59

Finally, to determine the degree of overlap between UBCs from human SCA1 patient post-mortem tissue and SCA1 KI mice, we first compared the enriched pathways of UBC DEGs from the two species, aggregating DEGs across the mouse timepoints. Pathways related to neurotransmitter secretion and synaptic vesicles were among the top enriched pathways for down-regulated genes across both species (Figures S7A and S7B; Table S10). Although all top enriched pathways from the upregulated gene list of human UBCs were similarly enriched in the mouse dataset, mouse UBCs displayed a unique enrichment in upregulated genes related to synapse assembly, which was not observed in human UBCs (Figures S7A and S7B; Table S10). Additionally, mouse (and not human) UBCs displayed a down-regulation of genes related to mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupled electron transport (Figures S7A and S7B; Table S10), some of which emerged at early timepoints (Table S6). After removal of DEGs without known orthologs between mouse and humans, individual UBC gene lists were compared, which revealed over 500 common DEGs between the two species. Repeating the pathway analysis on only these shared UBC DEGs uncovered an enrichment in genes related to splicing, dendrite development, and synaptic functions, among others (Figure S7D; Table S10). Future studies aimed at understanding how these gene expression changes across the heterogenous UBC subpopulations specifically impact their physiology and manifest in synaptic and circuit dysfunction, possibly through altering response dynamics to pre-synaptic inputs, may help to explain a role for UBCs in SCA1 pathogenesis.

Longitudinal dynamics of PCs throughout SCA1

PCs undergo substantial gene expression changes prior to eventual cell death in SCA1.62 Bulk RNA-seq of the SCA1 mouse cerebellum has revealed several tissue-level changes that have been suggested to be the result of PC perturbations;63–65 however, due to their relative rarity in the heterogenous cerebellum, it remains unclear to what degree this interpretation is confounded by changes in other cell types. Therefore, we sought to define the PC-specific transcriptional dynamics with single-cell accuracy throughout multiple stages of disease for the first time. To characterize the progressive transcriptional dysregulation in SCA1 PCs, we first examined overall differential gene expression in the mouse at 5, 12, 18, 24, and 30 weeks of age. Although gene expression differences were observed in PCs at all timepoints (Figure 1K; Tables S3–S6), hierarchical clustering of WT and SCA1 PCs revealed the largest overall transcriptional divergence between genotypes at 24 weeks of age (Figure 2A), driven both by number of DEGs and the degree of differential expression. Surprisingly, of all timepoints sampled, PCs from the 18- and 24-week mice displayed the largest differential expression between genotypes, which was partially corrected in late-stage 30-week animals (Figure 2A). This relative normalization of PC gene expression changes between genotypes at late stages of disease was not only reflected in the number of DEGs, but also in the degree to which DEGs were dysregulated (Figures 1K and 2A–2C; Table S6), raising the possibility of homeostatic adaptation (see Discussion).

Figure 2. SCA1 Purkinje cell dynamics over time.

(A) Heatmap of relative normalized expression for DEGs in mouse PCs over time.

(B and C) Smoothed histograms displaying time-dependent alterations in distribution of normalized gene expression for selected genes that are down-regulated (B) and up-regulated (C) in SCA1 mouse PCs.

(D) Heatmap of significantly enriched pathways in the PC population over time.

(E) Western blots validating time-dependent changes of several PC-enriched genes/proteins in the SCA1 KI mouse cerebellum (WT, n=4; SCA1, n=4 mice per timepoint). The target band for Prkg1 is denoted with a closed arrow and a non-specific band with an open arrowhead. For quantification data, target expression was normalized to a loading control (vinculin) and then to the average of WT mice at each timepoint.

(F) Representative images of detected RNA foci of PC markers from MERFISH analysis of the WT and SCA1 KI cerebellum of 18 week mice.

(G and H) Representative images of detected RNA foci (G) and smoothed histograms (H) displaying differential expression of selected up- and down-regulated genes in PCs of the 18 week WT and SCA1 cerebellum, as determined using MERFISH.

Data presented in (E) are mean±s.e.m. Student’s t-tests were performed to compare genotypes within each timepoint. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

See also Figures S8–S12, and Tables S11–S13.

Pathway analyses of DEGs in PCs at early timepoints revealed the highest enrichment in genes related to synaptic long-term depression (LTD), neurovascular coupling signaling, and synaptogenesis signaling (Figure 2D; Figure S8; Table S11). Because synaptic LTD at the parallel fiber (PF) to PC synapse requires type 1 glutamatergic signaling, which has been previously reported to be dysfunctional in multiple cerebellar disorders,66 including SCA1,64,67–69 we aimed to define the precise molecular changes in this signaling pathway in PCs. Among all down-regulated protein-coding genes in PCs, the most reduced gene (by EMD) at most timepoints was Grid2 (Figure S8C; Table S6), which encodes the glutamate receptor subunit delta-2 (Gluδ2). Gluδ2 functions as a post-synaptic regulator of mGluR1 specifically at the parallel fiber (PF) to PC synapse70 and is necessary for cerebellar LTD, motor learning, and proper establishment of PF and climbing fiber (CF) territories on PCs.71,72 In humans, GRID2 deletion mutations cause a recessive ataxia73,74 and its reduction contributes to cerebellar dysfunction in essential tremor.75 Furthermore, loss-of-function hotfoot mutations of Grid2 in rodents (for which over 20 alleles have been described) result in severe ataxia and cerebellar atrophy.76 Thus, the early and progressive reduction of Grid2 in SCA1 KI mice may contribute to the onset of motor deficits, as well as the pathological abnormalities in spatial distribution of CF inputs onto PCs observed in SCA1.77–79

Beyond Grid2 down-regulation, extensive early changes in other post-synaptic molecules involved in LTD at the PF to PC synapse were also observed at 5 weeks of age, including dysregulation of AMPA receptor subunit-encoding Gria1, Gria3, and Gria4; mGluR1-dependent signal transduction molecules Plcb1, Plcb3, and Prkca; and nitric oxide/cGMP-dependent protein kinase Prkg1 (Table S6). As disease progressed, additional genes central to cerebellar LTD, PF to PC signaling, and calcium handling were also dysregulated (Figure 2B; Figure S8). Many of these genes were the most differentially expressed at 18 weeks (Figure 2B; Table S6), which we also validated for several PC-enriched genes at the protein level using bulk mouse cerebellar tissue (Figure 2E) and multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH) for simultaneously probing 140 different genes, including PC DEGs of interest identified by our snRNA-seq analysis (Figures 2F–2H; Figure S9; Table S12). Although PF-evoked synaptic responses in SCA1 PCs have been reported to be grossly normal,79 pre-symptomatic mice display a decline in efficiency in PF-PC signaling,80 which may contribute to early plasticity-related deficits at this synapse in SCA1.69 Because the downstream signaling pathways at this synapse identified in our snRNA-seq analyses are critical for the complex functions of the cerebellum, including various forms of plasticity and motor learning, dysregulation is likely to compromise proper cerebellar functionality.

In addition to these LTD-related changes (Figure S10), a persistent down-regulation of genes involved in calcium handling was observed starting from 5 weeks of age, which progressed in magnitude of down-regulation, as well as in a number of genes by later timepoints Figure S8B; Table S6 and S11). This early disruption of calcium homeostasis in PCs is consistent with recent studies of SCA1 B05 animals,81 as well as SCA7 transgenic mice.82 Starting at 12 weeks of age, the most enriched pathways were related to netrin and synaptogenesis signaling (Figure 2D; Figure S8A; Table S11), suggesting potential alterations in neuronal cell-cell communication and cerebellar circuit stability. Among these DEGs, many cell adhesion and axon guidance signaling molecules involved in synapse formation and maintenance were up-regulated (Figure 2C; Figure S8A; Tables S5, S6, and S9), and these DEGs persisted through all timepoints examined. We confirmed increased protein expression of Caspr2 (encoded by Cntnap2) in bulk protein lysates of 24-week SCA1 KI mice (Figures S11A and S11B). Furthermore, although Dlg4 (encodes PSD-95) was not differentially expressed at the transcript level in our mouse snRNA-seq dataset (Table S6), we observed increased PSD-95-positive puncta and vGlut1/PSD-95 double-positive co-localized puncta in PC dendrites of 24-week SCA1 KI mice (Figures S11C and S11D), suggesting compensatory changes in PF to PC connectivity, likely in response to broad synaptic dysfunction. Collectively, these data highlight the PF to PC synapse as a potential site of early, persistent, and progressive transcriptional dysfunction that coincides with the onset and progression of behavioral impairments in SCA1, warranting further electrophysiological studies of PF-PC synaptic plasticity.

Similar to our cross-species examination of UBCs, we performed a comparative analysis of SCA1 human and mouse PCs. Although only a small number of top enriched pathways were shared between the two PC datasets (Figures S12A and S12B; Table S13), over 300 DEGs were commonly changed in the two datasets, many of which encode key genes involved in key PC functions (Figure S12C). Pathway analysis of the shared DEGs demonstrated an enrichment of genes related to glutamatergic transmission (Figure S12D; Table S13). Interestingly, human PCs displayed a downregulation of many nuclear-encoded genes involved in mitochondrial electron transport and ATP synthesis, which was not observed at any analyzed timepoint in SCA1 KI mice (Figure S12C). Although functional mitochondrial deficits have previously been reported in SCA1 KI83 and transgenic84 mouse models, identification of robust transcriptional changes in mitochondrial genes in SCA1 PCs may require assessment of terminal timepoints of disease, beyond 30 weeks. Overall, in addition to revealing several differences between SCA1 PCs in humans and mice, this analysis further reinforced glutamatergic signaling deficits as a core dysregulated pathway in PCs across species in SCA1.

Analysis of PC subclusters

The cerebellum is functionally organized into distinct domains that differ in input source and target projections to coordinate its various motor and non-motor functions. In addition to regional differences in the connectivity of the cerebellar cortex microcircuitry,85 individual cells of the cerebellum, including PCs, display regional molecular specializations that can influence their function in the healthy and diseased brain.24 To explore PC heterogeneity in SCA1, we examined if PCs from the mouse cerebellum could be segregated into subclusters based on overall transcriptional similarity. To this end, we first assessed the number of distinct subclusters that could be recovered with increasing clustering resolution, which revealed 5 major subpopulations that comprised the majority of all PCs, which we labeled as PC0, PC1, PC2, PC3, and PC4 (Figure 3A; Figure S13A). These subclusters were present at all sampled timepoints (Figures S13B and S13C) but differentially represented across the two genotypes, with PC0 and PC4 being increased and PC2 being reduced in SCA1 relative to the proportions observed in WT mice (Figures 3B and 3C). Differential expression analysis between subclusters revealed sets of candidate marker genes to distinguish between subclusters, including Car10 and Pde4b (PC0), Chst8 (PC1), Atp6ap1l (PC2), Cux2 (PC3), Hs6st3 (PC4) (Figure S13D), among others (Figures 3D and 3E; Table S14).

Figure 3. Analysis of Purkinje cell subpopulations in SCA1.

(A and B) UMAP embeddings displaying five major subclusters (A) and genotypes (B) of mouse PCs.

(C) Relative proportions of each PC subcluster aggregated over time in the WT and SCA1 mouse cerebellum snRNA-seq dataset.

(D) Heatmap of non-imputed expression z-score for the top 20 marker genes for each of the five PC subclusters.

(E) Dot plots displaying non-imputed relative expression of selected marker genes for each of the five PC subclusters.

(F and G) UMAP embeddings displaying non-imputed expression of Aldoc and Kctd16 (F) and zebrin II (Aldoc)-subcluster assignment of mouse PCs (G).

(H) Dot plots displaying non-imputed expression of DEGs in Aldoc+ and Aldoc− PC subpopulations averaged over time.

(I) Representative smFISH images acquired with identical intensity parameters for detection of Aldoc RNA foci showing distinct Aldoc+ and Aldoc− PC populations in the 18-week WT cerebellum. (J-M) Representative images of detected RNA foci (J,L) and smoothed histograms (K,M) showing differential expression between genotypes in 18-week Aldoc+ (J,K) or Aldoc− (L,M) PCs.

See also Figure S13, and Table S14.

Historically, individual markers have been reported to label exclusive PC subtypes. Among these distinguishing markers, the parasagittal striping of Aldoc (zebrin II)-expressing and zebrin II-negative PCs is of considerable interest in neurodegenerative disorders, as these subpopulations have been shown to display differential susceptibility to degeneration in response to certain experimental, genetic, and pathological perturbations.86–89 Therefore, we next examined if the PC subclusters identified in our snRNA-seq dataset could be segregated based on Aldoc expression. Although not entirely distinguishable by Aldoc expression, our 5 PC subclusters could largely be classified as Aldoc-positive/Kctd16-negative (PC0, PC2, PC3) or Aldoc-negative/Kctd16-positive (PC1, PC4) (Figures 3E–3G). To explore the effect of SCA1 mutations on Aldoc-positive and Aldoc-negative PCs, we examined differential non-imputed expression between genotypes overall (Figure 3H) and between genotypes at each timepoint (Figure S13E) within each PC subpopulation. Consistent with a recent study,90 assessment of PC DEGs in these subclusters revealed similar SCA1-dependent transcriptional responses in both PC subpopulations (Figure 3H; Figure S13E), which we also confirmed using single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) (Figures 3I–3M). These data demonstrate that both Aldoc-positive and Aldoc-negative PCs are affected in SCA1 KI mice; therefore, we proceeded to analyze the aggregated mouse PC cluster for downstream analyses.

Myelination is impaired in SCA1

Our snRNA-seq analysis of SCA1 mouse and human post-mortem tissue revealed a large number of DEGs in glial clusters (Figures 1J and 1K; Tables S3–S6), with a high number of DEGs identified in the oligodendroglial lineage (OPC and OL), a glial population suggested to be involved in several other neurodegenerative disorders,91,92 including at least two other polyQ diseases.93–98 OLs, the myelin-producing cells of the central nervous system, serve essential functions in promoting efficient action potential conduction through myelination and in providing metabolic support to axons.99–102 Specifically within the cerebellum, myelination of PC axons is necessary for precise synaptic transmission onto deep cerebellar nuclei neurons,103 which integrate information from the cerebellar cortex with excitatory inputs from extracerebellar regions and subsequently project to their target output regions throughout the central nervous system.

Pathway analysis of human OLs revealed the highest enrichment for pathways related to myelin, driven primarily by down-regulated genes (Figure 4A; Table S15). Examination of DEGs revealed an overall reduction of mature OL transcripts, including nearly all genes encoding the most abundant human myelin proteins recently identified by mass spectrometry104 (Figure 4B and 4C). We validated these findings by immunoblotting in cerebellar lysates from CTRL and SCA patient post-mortem tissues, which demonstrated a reduction of myelin proteins in SCA1 and SCA3 patient tissues, but not SCA6 (Figures 4D and 4E), consistent with neuroimaging studies.105,106 Human tissue-level changes in myelination were further confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure S14A) and immunohistochemistry in the cerebellar cortex of a larger cohort of SCA1 patients (Figures 4F and 4G; Figures S14B–S14I).

Figure 4. Oligodendrocyte impairments and myelin deficits in SCAs.

(A) Gene ontology (biological process) analysis of total, down-regulated, and up-regulated DEGs in human OL cluster. Top five pathways with the highest fold enrichment for each gene set are displayed.

(B) Volcano plot displaying DEGs of the human OL cluster.

(C) Smoothed histograms displaying distribution of expression of major myelin protein-encoding transcripts in the human OL cluster, showing significant decreases in SCA1.

(D and E) Validation of myelin protein reduction in the SCA1, SCA3, and SCA6 human post-mortem cerebellar cortex relative to controls (CTRL) (CTRL, n=3; SCA1, n=3; SCA3, n=5; SCA6, n=1 patient).

(F and G) Immunohistochemistry (F) and quantification (G) of OL number (i.e. opalin+ cells) and myelination (MBP+ staining) in the granule cell layer (GCL) of the human post-mortem cerebellar cortex (CTRL, n=10; SCA1, n=10 patients). Opalin, scale bar=100μm. MBP, scale bar=100μm.

(H) Heatmap of significantly differentially expressed OPC/OL genes from bulk RNA sequencing of the 12-week WT and SCA1 KI mouse cerebellum (WT, n=3; SCA1, n=3 mice).

(I and J) Western blots confirming myelin protein reduction in the 12-week SCA1 KI mouse cerebellum (WT, n=3; SCA1, n=3 mice).

(K-M) Transmission electron microscopy of PC axons from the 13-week WT and SCA1 KI mouse cerebellum (K) revealed a reduction in percentage of myelinated PC axons (L) and increased g-ratio (M) in SCA1 KI mice. Scale bar=2μm. Red asterisks indicate nonmyelinated axons.

For bar plots, data are mean±s.e.m. The following statistical tests were used: Student’s t-tests to compare across genotypes for (G, J, and L); one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to compare across genotypes for (E). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

See also Figures S14 and S15, and Table S15.

Because we observed robust myelin deficits in post-mortem tissues of late-stage SCA1 patients, we next aimed to interrogate the course of myelin impairments during SCA1 progression by examining oligodendroglia throughout time in SCA1 KI animals. Although OPCs and OLs comprise a small fraction of the total cells of the cerebellum (Figures 1F and 1G; Figures S3A, S3B, and S3E–S3G), the consequences of their dysfunction were observed at the tissue level in the cerebellum as early as 12 weeks of age, as demonstrated by bulk RNA-sequencing63 (Figure 4H) and biochemical analysis of myelin proteins (Figures 4I and 4J). This reduction in key myelin transcripts was also observed in the SCA1 cerebral cortex (CX) and inferior olive (IO) of the brainstem, two brain regions that display differential susceptibility in SCA1 (Figures S15A–S15D),63,64,107 suggesting that reduced myelination may contribute to diverse disease-associated pathologies across multiple brain regions. Ultrastructurally, SCA1 KI mice displayed an age-dependent progressive reduction in myelination of PCs, with minor changes in myelin ultrastructure at 6 weeks of age that became more pronounced by 13 weeks of age (Figures 4K–4M; Figures S15E–S15G). Collectively, these data demonstrate that myelin deficiencies may contribute to cerebellar circuit dysfunction from early stages of disease through adulthood; however, confirming this will involve conditional animal studies to selectively express or ablate mutant ataxin-1 in select oligodendroglial populations.

Progressive impairments in OPC to OL differentiation

The proper maintenance and plasticity of myelin through adulthood require continual remyelination, a process in which adult OPCs terminally differentiate into myelin-forming OLs in response to appropriate stimuli.108–110 Additionally, adult remyelination and myelin plasticity are essential for motor learning,111–114 a major function of the cerebellum that is impaired at early timepoints in SCA1 KI mice.4 Because there was a large dysregulation of genes in mouse and human oligodendroglia, including multiple transcription factors involved in OL formation and maturation (OLIG1, OLIG2, NKX6–2, ZNF24, ZNF488, ZNF536, MYRF) (Figure S16A), and many significantly down-regulated genes of the SCA1 OL cluster encode proteins restricted to terminally-differentiated OLs (Figures 4B and 4C), we hypothesized that transcriptional dysregulation at multiple stages during differentiation may impair the formation of OLs and remyelination during adulthood, and contribute to a failure to maintain appropriate expression of pro-myelinating genes.

To study the conversion of OPCs to OL in vivo (Figure 5A), we crossed transgenic Plp1-EGFP/+ reporter mice115 with SCA1 KI animals and analyzed the number of undifferentiated OPCs (Olig2+/Plp1-EGFP−) and differentiating/mature OLs (Olig2+/Plp1-EGFP+) (Figure 5B). Although the total number of oligodendroglia (OPCs and OLs; Olig2+) was unchanged (Figures 5C and S16B), the relative proportion of OLs decreased in SCA1 by 12 weeks of age, with a greater percentage of Olig2+ cells remaining as OPCs (Figure 5D), which was not observed in younger, 5-week mice (Figure S16C). Because OPC differentiation is regulated both by cell intrinsic mechanisms and microenvironmental signals from surrounding cells,116,117 including PCs of the cerebellum,118 we next wanted to determine if the observed OPC differentiation block was due to primary oligodendroglial changes or secondary to PC dysfunction. To this end, we examined cerebellar myelination in a SCA1 animal model in which polyQ-expanded ataxin-1 expression is highly over-expressed but restricted to PCs (SCA1 B05; Pcp2-ATXN1[82Q]/+). Ultrastructurally, PC axons of SCA1 B05 mice displayed moderately increased myelination (Figures 5E–5G), contrary to the finding of severe hypomyelination in SCA1 KI mice in which mutant ataxin-1 is ubiquitously expressed in all cell types (Figure 5H). Furthermore, primary OPCs isolated from SCA1 KI mice and differentiated in vitro in the absence of other cell types failed to up-regulate key myelin transcripts (Myrf, Plp1, and Mbp) upon directed terminal differentiation into myelinating OLs, while retaining expression of OPC markers (Cspg4 and Pdgfra) (Figures 5I–5K). Collectively, these data suggest that the early myelin-related changes observed in SCA1 KI mice and patients are not secondary to PC dysfunction, but rather, at least in part due to cell autonomous primary deficiencies in oligodendroglia.

Figure 5. SCA1 OPCs undergo a cell autonomous differentiation block.

(A) PHATE embedding of human oligodendroglia lineage (OPC+OL clusters).

(B-D) Immunohistochemistry (B) and quantification of total oligodendroglia number (C; Olig2+; WT, n=6; SCA1, n=6 mice) and relative OPC and OL proportions (D; Olig2+Plp1-EGFP− and Olig2+Plp1-EGFP+, respectively; WT, n=3; SCA1, n=3 mice) in the cerebellum of the 12-week WT and SCA1 KI mice. Scale bar=100μm.

(E) Representative transmission electron microscopy images of myelinated PC axons from 15-week WT and SCA1 B05 mouse cerebellum. Scale bar=2μm.

(F-H) Quantification of g-ratio from 15-week WT and SCA1 B05 mice (F and G) and 13-week WT and SCA1 KI animals (H) (WT, n=351; SCA1 B05, n=441 axons from 2 animals per genotype; WT, n=660; SCA1 KI, n=716 axons from 3 animals per genotype).

(I) Schematic of primary OPC isolation and in vitro differentiation into OLs.

(J and K) qRT-PCR for OPC (J) and OL (K) marker genes in primary OLs differentiated in vitro for 17 days (WT, n=3; SCA1, n=3 animals).

For bar plots, data presented are mean±s.e.m. The following statistical tests were used: Student’s t-tests to compare across genotypes for (C,D,G,H,J and K). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001.

See also Figure S16.

Interestingly, ultrastructural analysis of myelinated cerebellar axons also revealed a progressive reduction in axon caliber (Figures S16D and S16E), which was more pronounced in SCA1 KI animals compared to SCA1 PC-specific transgenic B05 animals (Figure S16F). Because the SCA1 B05 animal is a model of severe PC dysfunction in the disease, the relatively lesser degree of axon diameter reduction in these animals suggests non-cell autonomous mechanisms can contribute to changes in PC integrity in SCA1 KI mice and patients. Given the role of OLs in metabolically supporting axons99,102 and the well-documented phenomenon of demyelination-induced axon caliber reduction,119–121 it is possible that the primary oligodendroglial deficits we report here influence long-term PC structure involving adaptive responses to preserve proper physiology within the cerebellar circuitry in SCA1; however, a causal relationship between oligodendroglial dysfunction and PC axon ultrastructural changes remains to be determined.

Continuous transcriptional dynamics throughout disease

Although the differential gene expression analysis of time-series data above provides a granular view of transcriptional alterations at specific timepoints throughout disease, chronic neurodegenerative disorders involve long-term, progressive changes that are not necessarily able to be categorized into a small number of discrete stages. Furthermore, individual cells sampled at a specific timepoint exist on a continuum of transcriptional profiles that may resemble those from other timepoints. Recently developed trajectory inference methods have been applied to successfully reconstruct complex lineages of varying topologies through pseudotemporal ordering of cells from single-cell datasets that undergo profound transcriptional changes over time, such as during differentiation122,123 or cellular reprogramming.124 Similar studies of cell trajectories in the context of neurodegenerative diseases have involved sampling single cells captured from a single biological timepoint, usually post-mortem.11,14,19 Because these analyses order cells along an axis of transcriptional variation between healthy and diseased cells, the inferred trajectories do not necessarily capture the chronological processes that underlie progressive age-dependent pathological changes. Furthermore, although pseudotemporal analyses of time-series single-cell data from animal models of neurodegeneration have enabled the identification of emergent populations that are mostly found in late-stages of disease,125–127 how these methods perform in capturing more subtle age-related transcriptional changes in cells that retain their same overall transcriptional state over time remains to be determined.

To broadly characterize each cerebellar cell type’s variable contribution to SCA1, we aimed to generate cell trajectories that capture continuous gene expression changes over both chronological time and disease progression. To computationally infer continuous cell type-specific gene expression dynamics from our SCA1 KI mouse time-series data, we first compared the relationship of pseudotemporal ordering of single cells calculated using several methods123,128–131 with chronological time (Figure S17). Overall, the continuous trajectories constructed using MELD matched best with biological age (Figure 6A; Figures S17M–S17P), also visualized by PHATE (Figure S18). By constructing these trajectories, we were able to examine longitudinal expression patterns for individual genes or groups of genes, simultaneously comparing the heterogeneous dynamics of differential expression between genotypes over the course of disease in each cell type.

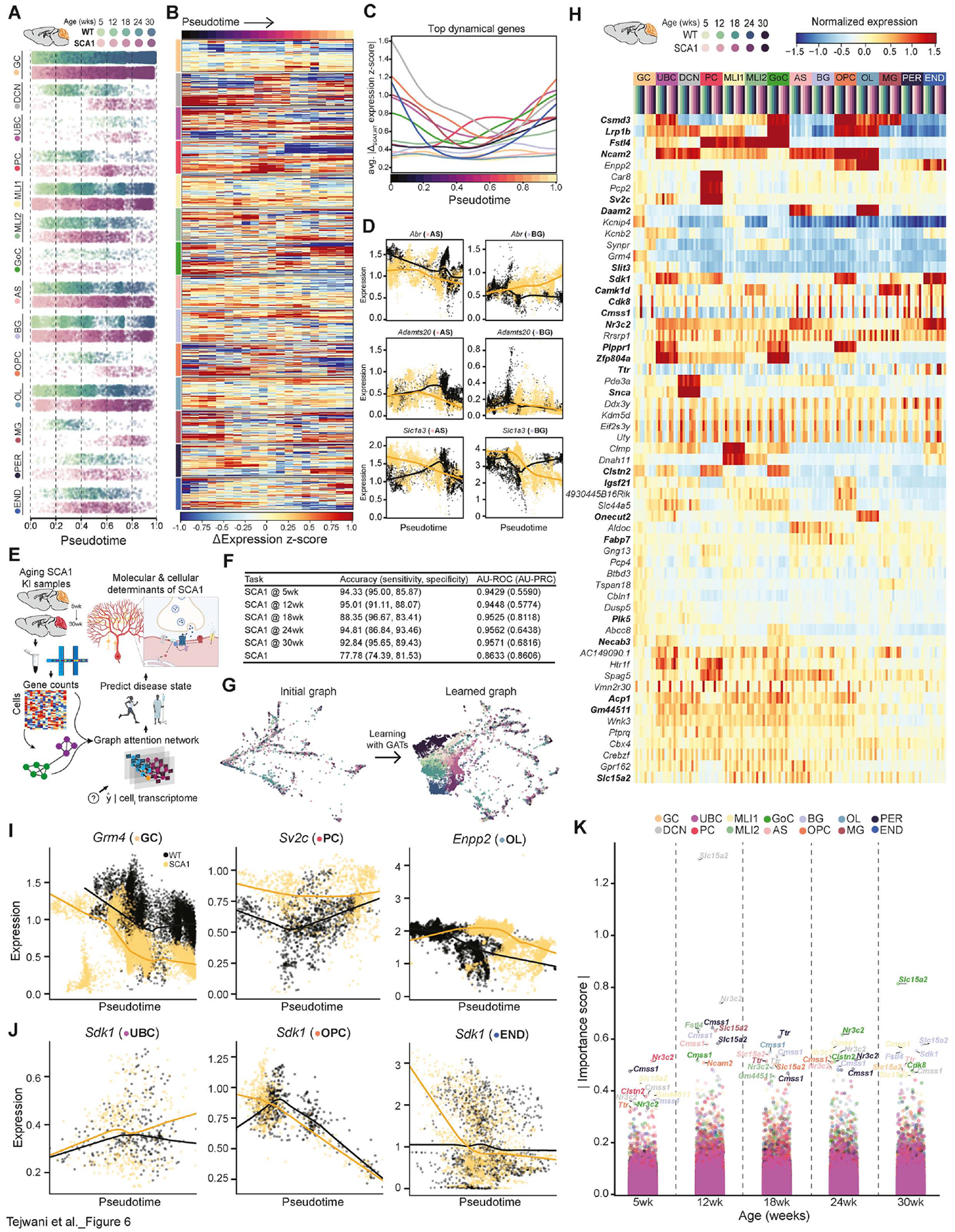

Figure 6. Cell trajectories and deep learning to predict disease state and progression.

(A) Pseudotemporal ordering of mouse time-series data using MELD to generate continuous progressions for each cell type cluster.

(B) Heatmap displaying ΔSCA1-WT expression z-score for top 100 WT and SCA1 dynamical genes within each cell type over pseudotime.

(C) Average |Δexpression| between genotypes of the top 100 WT and SCA1 dynamical genes within each cell type over pseudotime to highlight timing of each cell type’s dysregulation. Expression was represented as z-score to standardize the displayed units.

(D) Expression dynamics of select dynamical genes over pseudotime show differential patterns between AS (left) and BG (right) clusters.

(E) Schematic overview of approach using geometric deep learning on snRNA-seq data to predict disease state at single-cell resolution to gain insights into pathophysiology.

(F) Performance and evaluation of each model on the test set across 6 binary classification tasks.

(G) PHATE embeddings of test set cells based on the original cell-similarity graph (left), which served as input to each GAT model, and the graph learned by one of the attention heads in the GAT model discriminating between genotypes (right).

(H) Heatmap of z-score of mean expression of top 20 salient protein-coding genes per attention head in the five binary classification tasks predicting SCA1 at various timepoints.

(I and J) Expression dynamics of select salient genes from (H) over pseudotime shows that the GAT model pays attention to genes that are highly differentially expressed between genotypes (I), as well as genes with more nuanced patterns of differential expression (J).

(K) Importance scores for each gene across various cellular subsets. Importance was calculated by computing Integrated Gradients for the average expression of each cell subset across the test set, relative to a baseline of no expression. The top 10 important protein-coding genes for each timepoint are labeled. Bolded genes in (H and K) are salient/important for both the GAT and Integrated Gradient approaches.

See also Figures S17–S19, and Tables S16–S18.

Because Capicua (Cic) has been described to be the primary mediator of PC toxicity in SCA1,33 we first examined the expression dynamics of Cic target genes in each cell trajectory using a list of genes from Cic chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing (ChIP-seq) in the developing brain.132 Assessing differential expression trajectories of known Cic target genes for each cell type revealed several key insights. First, expression dynamics of Cic target genes were different across each cerebellar cell type, with DCN, PC, OPC, MG, and END populations displaying the largest differences between genotypes (Figure S19A). Additionally, consistent with previous studies,132,133 Cic target genes displayed both patterns of de-repression and hyper-repression that were dynamic over time. Examination of individual gene dynamics within the PC cluster revealed that a large number of Cic motif-containing genes was differentially down- (Grid2, Cdh18, etc.) or up-regulated (Nrxn1, Cntn4, Cntnap2, Cntn5, Lrp1b, Nrg3, etc.) in our dataset (Figure S19B; Table S6). Similarly, many Cic target genes were differentially expressed in the OPC cluster, with dynamic trajectories for many genes displaying a strong, early down-regulation (Figure S19C). These data demonstrate that for clusters that displayed the greatest overall differential expression and also showed robust differences in Cic target gene trajectories (i.e. PC, OPC, MG) (Figure 1K; Figure S19), alterations in ataxin-1-Cic signaling may be driving the observed gene expression changes. However, for cell types with high differential expression but minimal changes in Cic target gene expression, such as UBC (Figure 1K; Figure S19A), it is likely that alternate signaling complexes are involved in their transcriptional dysregulation.

We next utilized these trajectories to assess the top dynamical genes, as these were most likely to be involved in progressive events as the animals aged. To calculate dynamical genes, we used a machine learning model to regress the pseudotime per cell given each cell’s transcriptome, ranking features by information gain and selecting the top 100 WT and SCA1 predictive genes within each cell type (Table S16). By comparing the mean expression difference between WT and SCA1 for each dynamical gene across pseudotime (Figure 6B; Table S16) and averaging across all top dynamical genes within a cell type, we generated a roadmap of the SCA1 cerebellum that describes the degree of overall perturbation for each cell type throughout all points during disease (Figure 6C). In addition to confirming the results of our differential gene expression analyses regarding early dysfunction of UBCs and OPCs (Figure 1K) and the peak dysregulation of PCs at mid-late disease stages (Figure 2), this analysis also provided an overview of the transcriptional dysregulation in all other cell types over time. We also performed a targeted examination of specific dynamical genes in AS and BG (a specialized type of unipolar AS), which revealed varying longitudinal expression profiles between these related cell types (Figure 6D), highlighting the utility of our single-cell approach in precisely understanding diverse individual gene and gene set expression patterns in different cell populations.

Supervised geometric deep learning to nominate putative disease drivers

Conventional differential gene expression analyses rely on gene-by-gene comparisons to associate genes with disease but may fail to identify interaction effects between genes, as well as marginal signals that, although weaker, are nonetheless associated with disease.134,135 Deep artificial neural networks with supervised optimization can be used to identify complex non-linear interactions between input features; however, neural networks are challenging to train and difficult to interpret. To better understand the complex dependencies between a cell’s transcriptome, developmental trajectory, and cell type in SCA1, we trained a geometric deep learning model on a subset of our longitudinal SCA1 snRNA-seq data to perform multiple tasks and applied a novel explainability approach to interpret the features underlying task performance of these black-box models (see STAR★Methods).

To do this, we used Graph Attention Networks (GATs), a geometric deep learning architecture, to train models in an inductive setting across 6 binary classification tasks (Figure 6E). In predicting whether an individual cell exhibits transcriptional signatures of SCA1 at each timepoint, this approach yielded a minimum area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AU-ROC) of 0.94229 and accuracy of 88.35%, suggesting that our models learn to detect unique SCA1 signatures at various timepoints (Figure 6F). In addition, this approach allowed us to take a single cell, of any timepoint or cell type, and determine with ~78% accuracy (AU-ROC, 0.8633) whether the cell exhibits a SCA1 transcriptional signature. As such, we can use deep learning to determine SCA1 status at any point during the lifetime of the mouse at the organismal scale with high accuracy, as well as to detect cells that exhibit early signs of SCA1 within cerebellar tissue. Importantly, these data demonstrate that our models can effectively learn biologically meaningful patterns from our snRNA-seq dataset.

After confirming the predictive accuracies of our models (Figure 6F) and constructing new weighted embeddings based on aggregated learned coefficients (Figure 6G), we next applied local and global algorithms to interpret the features within the dataset to which the models pay the most attention when predicting age and disease status labels, which we refer to as “gene saliency” (Figure 6H; Table S17). We hypothesized that because expression patterns within these genes were crucial for the highly accurate genotype and age label predictions, these genes may represent features that are important to the pathogenesis and/or progression of SCA1. To more specifically interrogate how the top globally salient genes contribute to SCA1 biology, we first examined their expression within individual cell types over time using our longitudinal mouse snRNA-seq dataset (Figure 6H). Among the genes enriched in specific cell types, robust gene expression differences between genotypes were observed for some salient genes within that population (Figure 6I), while for other genes, significant differential expression was not apparent (Figure 6J), demonstrating that GATs pay attention to a combination of diverse transcriptional signals.

Examining global gene saliency may omit subtle differences between various types of cells. To overcome this limitation, we applied a recently developed approach in the field of explainable AI (XAI), Integrated Gradients,136 to each model in order to attribute the models’ output to the variable importance of input features for cells of different cell types and timepoints. Rather than looking at global model saliency for a single input layer, Integrated Gradients calculates the adjustment that the learned model would make for a given input transcriptome throughout the computation graph. This analysis revealed a second, independent set of important genes, many of which overlapped with top salient genes from the GAT, which we considered high-confidence salient genes (Figures 6H and 6K; Tables S17 and S18). In addition to validating our earlier deep learning approach, this method revealed the specific cell types and timepoints during which each important gene had the highest importance score (Figure 6K), providing additional granularity and interpretability of this approach. Collectively, these deep learning approaches identified both prominent and nuanced transcriptional signatures that potentially contribute to SCA1 pathogenesis and progression and offer a complementary approach to traditional clustering and differential expression analysis of single-cell data.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have generated a longitudinal transcriptomic atlas of the mouse and human SCA1 cerebellum that describes the simultaneous transitions of individual cell types within a heterogenous tissue with single-cell precision. These data reveal new insights into the molecular and cellular underpinnings of SCA1 pathogenesis, with broad implications for other cerebellar and neurodegenerative disorders. First, we have comprehensively examined the transcriptional dysregulation in PCs, the major cerebellar cell type lost in SCA1, throughout disease. Surprisingly, our snRNA-seq revealed a partial normalization of PC gene expression at late stages in our mouse dataset, which we validated using two additional modalities (MERFISH and immunoblotting) in distinct cohorts of mice. Although it is possible that the most severely affected PCs had already degenerated by the 30-week timepoint and that the data reflect the transcriptomes of the less-affected, surviving PCs, this is unlikely to be the sole explanation, as this timepoint immediately precedes the bulk of cell loss in the SCA1 KI model. Follow-up histological studies that longitudinally examine the relative quantities of PC subpopulations are necessary to conclusively rule out the possibility of differential abundance in PC subpopulations as an explanation for the observed partial transcriptional normalization at late stages. Furthermore, we have also detailed the transcriptional changes that affect the PF to PC synapse, a major site of dysfunction in SCA1. In doing so, we have not only validated the findings of earlier studies,63,64,67,137 but also provided a great degree of additional granularity into the extent and the precise timing of events underlying the impairment of glutamatergic signaling transmission at this synapse.

Next, our data also revealed a profound transcriptional dysregulation in various glial populations, including oligodendroglia. Although OPCs receive bona fide synaptic input from multiple neuron populations to stimulate their terminal differentiation,138–140 our data demonstrate that the early OL deficits observed in SCA1 are, at least in part, cell autonomous and result from an OPC differentiation block. Whether the impairments in OL differentiation reported here are solely due to cell autonomous expression of mutant ataxin-1 in differentiating OPCs or are also induced by dysfunction in additional populations of cells with which they interact, such as CFs from the inferior olivary nucleus,140 remains to be determined. Furthermore, although PC-specific expression of polyQ-expanded ataxin-1 may drive late-stage myelin deficits, as white matter atrophy has been reported at very late stages in the SCA1 B05 mouse model,141 high overexpression of polyQ-expanded ataxin-1 in PCs is not sufficient to induce early cerebellar demyelination, highlighting the importance of using multiple experimental models to discern primary and secondary glial changes in neurodegenerative disorders. Nonetheless, due to their integral role in regulating the metabolic health and survival of axons,99,102 and due to the well-documented observation that demyelination induces ataxia,142 future studies aimed at determining the extent to which oligodendroglial deficits specifically contribute to SCA1 behavioral and pathological phenotypes, both cerebellar and extracerebellar, are warranted. Beyond PCs and OPCs/OLs, this study uncovers the unique molecular signatures of all major cell types of the cerebellum, including UBCs, throughout the course of SCA1 and will serve as a resource for the future experimental dissection of the complex interplay between these cell types in cerebellar health and disease. Importantly, many DEGs were conserved between the mouse and human snRNA-seq datasets, validating genetically accurate animal models as reliable tools for studying disease pathogenesis.

In addition to revealing specific insights into the pathogenesis of SCA1, the analysis pipeline developed here represents an important advance in the integration of single-cell technologies with novel computational tools to better understand dynamic events. By constructing continuous single-cell trajectories of densely sampled chronic time-series data, we have enabled the examination of progressive gene expression changes within a cell type over the course of disease, overcoming limitations of traditional approaches in which analysis of gene expression differences is restricted to and within a small number of discrete timepoints. We have also applied an XAI approach that not only accurately predicts labels related to cells in the snRNA-seq dataset but can also be used to interpret the molecular determinants of those labels that underlie the models’ predictive power, going beyond gene-by-gene comparisons at discrete timepoints to include patterns in multi-gene dynamics that concomitantly contribute to disease. Although we have applied this approach to SCA1, a monogenic disorder with a known genetic cause, the application of our XAI approach to similar datasets for idiopathic disorders may reveal early disease signatures and molecular drivers of disease. In summary, we believe the pipeline developed here and applied to SCA1 can serve as a prototype for future studies of the dynamics of a variety of large-scale quantitative data in the context of neurodegeneration or any progressive event.

LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

Here, we have generated a single-cell transcriptomic atlas for the SCA1 cerebellum by extensively profiling a well-characterized rodent model of the disease, as well as human patient post-mortem cerebellar tissue using snRNA-seq. Due to the rarity of SCA1, access to a large number of high-quality frozen age- and sex-matched patient samples is limited; therefore, although we sequenced ten unique control and ten SCA1 patient samples, our sampling of SCA1 human tissue remains a limitation of the present study due to variability in patient age at death, polyQ length, sampled cerebellar subregion, and post-mortem interval. As additional patient samples are made available (with accompanying clinical and pathological characterization), it will be imperative to determine the extent to which findings from our dataset, as well as from SCA1 KI animals, are generalizable across diverse SCA1 patient cohorts that vary in age, polyQ length, ethnicity, and other parameters that may influence transcriptional readouts, and to evaluate how these transcriptional changes reflect clinical disease severity.

An additional limitation of the present study is related to the deep learning approach for our mouse snRNA-seq dataset. By having a relatively small sample size for a machine learning application, having completely independent cohorts of mice on which to train our models and to test their predictive accuracies was challenging; therefore, nuclei from the same 30 mouse cohort were assigned to the (non-intersecting) training, validation, or test sets. Although validation of the diagnostic utility of our models would require testing on truly independent holdout samples from the training set, these high predictive accuracies support the application of our models for the purpose of biological inference, as these data demonstrate the models’ ability to effectively learn features that distinguish WT and SCA1 nuclei in the present dataset beyond genes that emerge from differential expression analyses between groups. That said, the biological effect sizes of various salient genes from these XAI studies have yet to be determined. How and to what extent individual gene perturbations are related to specific SCA1 phenotypes remain outstanding questions. Future studies that experimentally interrogate individual genes identified with our approach will provide new insights into key dysregulated pathways and disease signatures in SCA1.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests should be addressed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Janghoo Lim (janghoo.lim@yale.edu).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

All raw fastq data files from human and mouse snRNA-seq were deposited into GEO under accession GSE246183. The data and additional details of protocols used for this study are available from the Lead Contact upon reasonable request. Scripts used to analyze the snRNA-seq data and the software for the Graph Attention Networks and Integrated Gradients with noise tunnels are also available at the following link for academic use: https://github.com/ChrLeeee/SCA1_snRNAseq_CB.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animal Husbandry

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Experimental animals and approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. SCA1 knock-in (SCA1 KI; Atxn1154Q/+)4 and PC-specific transgenic (SCA1 B05; Pcp2-ATXN1[82Q]/+),143 and Plp1-EGFP/+ reporter mice,115 along with their littermate controls, were maintained on a pure C57BL/6J background. Mice were maintained on a 12 hours light and 12 hours dark cycle with standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. For animal PCR genotyping, tail snips for DNA extraction were taken for between P14-P17 for all animals. Both male and female mice were used for biochemical and sequencing analyses (see Table S1). Mouse tissue for biochemical analysis was collected as previously described.63

Human Tissue Samples and Patient Information

Frozen human post-mortem tissue used for snRNA-seq, qRT-PCR, and western blotting was provided by the Michigan Brain Bank through Dr. Vikram Shakkottai and Dr. Hayley McLoughlin, the Center for NeuroGenetics (Florida) through Dr. Laura Ranum, the New York Brain Bank and NIH-Maryland through Dr. Phyllis Faust, and from Baylor College of Medicine through Dr. Huda Zoghbi. For histological analyses, ten human SCA1 cerebellar samples were obtained from a hereditary ataxia specimen repository at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Albany, New York (courtesy of Dr. A.H. Koeppen). Six age-matched control cerebellar samples were from the New York Brain Bank, acquired from prospectively followed individuals that were clinically free of neurodegenerative disorders on serial neurological examinations through the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center or the Washington Heights Inwood Columbia Aging Project at Columbia University, and subsequently confirmed with neuropathological examination of the post-mortem brain.144 Four control brains were obtained from the National Institutes of Health NeuroBioBank (University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA). Standardized measurements of brain weight (grams) and post-mortem interval (hours between death and placement of brain in a cold room or upon ice) were recorded. Brains from male and female donors were used for all analyses. All individuals signed informed consent forms approved by the respective university or institutional ethics boards.

Primary Mouse OPC Cultures

Purification and culturing of primary mouse oligodendroglia were performed as previously described,145 with minor modifications. Briefly, P0-P2 mice were sacrificed and the cerebral cortex was dissected in ice-cold MEM. Dissected pieces of cortex were transferred to a 1.5mL microcentrifuge tube containing 350μL ice-cold MEM and gently broken into smaller fragments by pipetting through a P1000 tip. OPC papain solution [1.54mg/mL Papain solution (Worthington Biochemical; LS003126), 360μg/mL L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich; C7352), 60μg/mL DNase I (Roche; 1010159001)] was freshly prepared and pre-warmed to 37°C for 20 minutes. Cortex suspensions were also warmed to 37°C for three minutes and 75μL of OPC papain solution was added to each tube of cortex suspension. The cell mixture was transferred to a 15 mL tube and papain digestion was performed at 37°C for 20 minutes with gentle mechanical agitation every 2 minutes. 2mL of mixed glia culture medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100units/mL Penicillin and 100μg/mL Streptomycin) was then added to each tube and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. The cell suspension was gently triturated 15 times with a Pasteur pipette to dissociate into a single-cell suspension. An additional 2mL of mixed glia medium was then added to each tube, and cells were centrifuged at 1,200rpm for 5 minutes. Cell pellets from each brain sample were resuspended in 1mL of mixed glia medium, plated onto a poly-L-lysine-coated (Sigma-Aldrich; P2636) T25 flask, and cultured at 37°C with 8.5% CO2. A complete medium change was performed 3~4 hours after plating, and the flask was returned to the incubator to allow further expansion of a mixed glial cell culture. Three days later, a 2/3 media change with mixed glial media was performed.

After another six days, another 2/3 medium change was performed and 5μg/mL insulin (Sigma-Aldrich; I0516) was supplemented to promote oligodendroglial development. On day 9, the flask was transferred to an orbital shaker in the incubator with 5% CO2. One hour later, the flask was shaken at 50rpm for 45 minutes to remove loosely attached contaminant cells, followed by a media change with mixed glia media supplemented with 5μg/mL insulin. The flask was returned to the orbital shaker and equilibrated in the incubator without shaking for two hours. Next, the flasks were securely fastened and shaken at 220rpm for 16 hours. Meanwhile, coverslips or tissue culture dishes were coated with Matrigel (BD; 354230) in the incubator with 8.5% CO2 overnight. The next day, cell suspensions were collected and transferred to a 10cm tissue culture dish. The cell suspension was incubated in the incubator with 5% CO2 for 30 minutes with gentle agitation after 15 minutes. The cell suspension was collected and OPCs were centrifuged at 1,200rpm for five minutes. The pellet containing OPCs was resuspended in one mL of OL medium (DMEM, 5μg/mL insulin, 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco; 35050–061), 49.5μg/mL Holo-transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich; T0665), 2% B27 (Gibco; 0080085-SA), 0.5% FBS, 0.05ng/mL CNTF (PeproTech Inc; 450–50), and 1% OL supplement). The OL supplement contains 10.2mg/mL BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; A4503), 6μg/mL Progesterone (Sigma-Aldrich; P8783), 1.61mg/mL Putrescine (Sigma-Aldrich; P7505), 0.5μg/mL Sodium Selenite (Sigma-Aldrich; S5261) and 40μg/mL 3,3’,5-Triiodo-L-thyronine (Sigma-Aldrich; 1368008). 25,000 to 50,000 OPCs were then plated on Matrigel-coated coverslips or tissue culture plates directly and cultured in the incubator with 8.5% CO2 with OL medium changed every other day.

METHOD DETAILS

Isolation of Nuclei from Frozen Tissue

Nuclei were isolated from frozen tissue as previously described.10 For mouse snRNA-seq, hemicerebella of three animals per genotype (WT and SCA1 KI) per timepoint (5, 12, 18, 24, and 30 weeks) were used, for a total of 30 animals. For human post-mortem samples, pieces of cerebellar cortex were harvested from frozen tissue of ten unique individuals per diagnosis (CTRL and SCA1), for a total of 20 human samples. Briefly, frozen mouse or human tissue was gently dounce homogenized in 2mL of ice-cold Nuclei EZ Prep buffer (Sigma; NUC101–1KT) with large clearance pestle “A” and then a small clearance pestle “B” for 25 strokes each, then incubated on ice for five minutes with an additional 2mL of cold EZ Prep buffer. Nuclei were centrifuged at 500xg for five minutes at 4°C. Pelleted nuclei were then washed in 4mL of cold EZ Prep buffer, incubated on ice at five minutes, and centrifuged again at 500xg for five minutes at 4°C. Pelleted nuclei were then washed in 4mL of Nuclei Suspension Buffer (NSB) containing 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS), 0.01% BSA, and 0.1% RNase inhibitor (Clontech/Takara; 2313B) and centrifuged at 500xg for five minutes at 4°C. Finally, nuclei were resuspended in 1mL of NSB, filtered through a 40μm cell strainer (Fisher Scientific; 22-363-547), and counted using a Countess II FL Cell Counter (Applied Biosystems; A27978). Single-nucleus suspensions were diluted to approximately 1000 nuclei per μl in NSB.

10x Genomics snRNA-seq

Libraries were prepared from diluted single-nucleus suspensions using the 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v.3 (mouse dataset) or v.3.1 (human dataset) through the Yale Center for Genome Analysis (YCGA). Briefly, 10,000 cells per sample were added to RT Master Mix, loaded on the Single Cell A Chip, and portioned with a pool of about 750,000 barcoded gel beads to form nanoliter-scale Gel Beads-In-Emulsions (GEMs). Each gel bead has primers containing the following: an Illumina R1 sequence (read 1 sequencing primer), a 16-nucleotide barcode, a 12-nucleotide unique molecular identifier (UMI), and a 30-nucleotide poly-dT primer sequence. Upon dissolution of the Gel Beads in a GEM, the primers were released and mixed with the cell lysate and Master Mix. Incubation of the GEMs then produced barcoded, full-length cDNA from poly-adenylated mRNA. Silane magnetic beads were then used to remove leftover biochemical reagents from the post-GEM reaction mixture.

Full-length, barcoded cDNA was then amplified by PCR to generate sufficient mass for library construction, and enzymatic fragmentation and size selection were used to optimize the cDNA amplicon size prior to library construction. P5, P7, a sample index, and R2 (read 2 primer sequence) were added during library construction via end repair, A-tailing, adaptor ligation, and PCR. The final libraries contained the P5 and P7 primers used in Illumina bridge amplification. Libraries were sequenced using the NovaSeq6000 at the YCGA.

Sample concentrations were normalized to 1.2nM and loaded onto an Illumina NovaSeq S4 flow cell at a concentration that yielded 20k-50k passing filter clusters per cell per sample. Samples were sequenced using paired-end sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 instrument according to Illumina protocols using 10x sequencing specifications. The 8bp index was read during an additional sequencing read that automatically followed the completion of read 1. Data generated during sequencing runs were simultaneously transferred to the YCGA high-performance computing cluster. A positive control (prepared bacteriophage Phi X library) provided by Illumina was spiked into every lane at a concentration of 0.3% to monitor quality in real time. Signal intensities were converted to individual base calls during a run using the system’s Real Time Analysis (RTA) software. Base calls were transferred from the machine’s dedicated personal computer to the Yale high-performance computing cluster via a 1 Gigabit network mount for downstream analysis.

Mouse Cerebellum Histology and Microscopy

For all mouse immunohistochemical analyses, animals were anesthetized with isofluorane and transcardially perfused with cold 1x PBS for two minutes, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for four minutes, and then in 1x PBS for two additional minutes. Brains were dissected and post-fixed in 4% PFA for an additional 24 hours, sequentially dehydrated in 20% and 30% sucrose solutions in PBS, cryoprotected in TissueTek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura; 4583), and serially sectioned into 30μm-thick sagittal sections. Four to six sections from matched cerebellar regions of each animal were washed three times in PBS-X [1x PBS + 0.025% Triton X-100 (American Bioanalytical; AB02025)] for five minutes each, blocked with blocking buffer [5% normal goat serum (NGS; Jackson ImmunoResearch; 005-000-121) diluted in PBS-X] for one hour at room temperature, and incubated in primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The following day, sections were washed three times with PBS-X for five minutes each, incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for one hour at room temperature protected from light, washed three times with PBS-X for five minutes each, and mounted onto slides using VECTASHIELD HardSet Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories; NC9029229). Tiled images were acquired from each section using a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope with a 20x objective (OPC Plp1-EGFP experiments) or 40x objective (PF-PC synaptic co-localization experiments) by an experimenter blinded to genotype. UBC synaptic experiments were imaged on a VS200 slide scanner with a 40x objective.

The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-vGlut1 (Synaptic Systems; 135316; 1:500), rabbit anti-PSD-95 (Abcam; ab238135; 1:100), mouse anti-Calb1 (Millipore; C9848; 1:1000), rabbit anti-Trpc3 (Cell Signaling; 77934; 1:500), chicken anti-Tbr2 (Millipore; AB15894; 1:100), mouse anti-calretinin (Millipore; MAB1568; 1:500), guinea pig anti-vGlut2 (Synaptic Systems; 135404; 1:500), rabbit anti-Olig2 (Abcam; ab109186; 1:500), and chicken anti-GFP (Abcam; ab13970; 1:1,000), The following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher; A11001; 1:500), goat anti-chicken IgY Alexa Fluor 647 (ThermoFisher; A32932; 1:500), goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher; A32931; 1:500), goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 555 (ThermoFisher; A32728; 1:500), goat anti-chicken IgY Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam; 150169; 1:500), and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 568 (ThermoFisher; A-11011; 1:500), and goat anti-guinea pig IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher; A-11073; 1:500).

MERFISH and smFISH Probe Design, Synthesis, and Antibody-Oligo Conjugation