Abstract

Through whole exome sequencing of 60 FFPE Nigerian (NGRn) benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) samples, we identified germline and somatic alterations in apoptotic pathways impacting BPH development and progression. Prostate enlargement is a common occurrence in male aging; however, this enlargement can lead to lower urinary tract symptoms that negatively impact quality of life. This impact is disproportionately present in men of African ancestry. BPH pathophysiology is poorly understood and studies examining non-European populations are lacking. In this study, NGRn BPH, normal prostate and prostate cancer (PCa) tumor samples were sequenced and compared to characterize genetic alterations in NGRn BPH. 202 non-benign, ClinVar annotated germline variants were present in NGRn BPH samples. Six genes [BRCA1 (92%), HSD3B1 (85%), TP53 (37%), PMS2 (23%), BARD1 (20%) and BRCA2 (17%)] were altered in at least 10% of samples; however, compared to NGRn normal and tumor, the frequency of alterations in BPH samples showed no significant differences at the gene or variant level. BRCA2_rs11571831 and TP53_rs1042522 germline alterations had a statistically significant co-occurrence interaction in BPH samples. In at least two BPH samples, 173 genes harbored somatic variants known to be clinically actionable. 3 genes (COL18A1, KIF16B and LRP1) showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) higher frequency in BPH. NGRn BPH also had five gene pairs (PKD1/KIAA0100, PKHD1/PKD1, DNAH9/LRP1B, NWD1/DCHS2 and TCERG1/LMTK2) with statistically significant co-occurring interactions. 279 genes contained novel somatic variants in NGRn BPH. Three genes (CABP1, FKBP1C and RP11–595B24.2) had a statistically significant (p < 0.05) higher alteration frequency in NGRn BPH and three were significantly higher in NGRn tumor (CACNA1A, DMKN and CACNA2D2). Pairwise Fisher’s exact tests showed fourteen gene pairs with statistically significant (p < 0.05) interactions and four interactions approaching significance (p < 0.10). Mutational patterns in NGRn BPH were similar to COSMIC signatures associated with aging and dysfunctional DNA damage repair. NGRn BPH contained significant germline alteration interactions (BRCA2_rs11571831 and TP53_rs1042522) and increased somatic alteration frequencies (LMTK2, LRP1, COL18A1, CABP1 and FKBP1C) that impact apoptosis. Normal prostate development is maintained by balancing apoptotic and proliferative activity. Dysfunction in either mechanism can lead to abnormal prostate growth. This work is the first to examine genomic sequencing in Nigerian BPH and provides data that fills known gaps in the understanding BPH and how it impacts men of African ancestry.

Keywords: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, African Ancestry, Whole Exome Sequencing, somatic variants, germline variants, apoptosis

Statement of Significance

BPH disparities in Black men are poorly understood but could be the product of African ancestry. This is the first study utilizing whole-exome sequencing in Nigerian men to identify West African Ancestry-linked variant patterns that are associated with BPH.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common male disease whose prevalence increases with age1, 2. It is a non-cancerous over-proliferation of fibromuscular and epithelial tissue within the transition zone and periurethral area of the prostate. This proliferation leads to progressive prostatic enlargement, which can cause lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), including erectile dysfunction, retention, renal failure, and stones3. Starting at age 50, histological BPH will be detected in approximately 50% of men and 10–20% will report significant LUTS. After 50 years of age, the prevalence of BPH increases 10% each subsequent decade of life4.

Though BPH is a common feature of male aging, studies have shown ethnic/racial disparities in BPH/LUTS prevalence, pathology, and genetic variation. The Flint Men’s Health Study showed that 34% of European American men reported moderate to severe LUTS compared to 41% of African American men (p < 0.001)5. African American men also have a significantly larger transition zone index (TZI) when compared to Hispanic and European American men6. TZI is the ratio of transition zone volume to total prostate volume and higher ratios are associated with increased BPH severity. In terms of genetic variation, a study of 620 healthy African American men identified two SNPS associated with LUTS severity. Specifically, CASC21_rs445114 was associated (OR=0.78) with marginally decreased urinary symptoms and NUDT11_rs5945572 was significantly associated (OR=1.33) with increased urinary symptoms7.

No causal link between BPH and prostate cancer has been established but African Americans with BPH have been shown to have a two times higher incidence of prostate cancer when compared to European American men8. A review of the literature provides evidence that this disparity is both genetic and inheritable. A trans-ethnic GWAS study, using samples from the eMERGE network, determined that roughly 60% of BPH phenotypic variation is accounted for by genetic factors9 and a study of 214,717 white men, from the population-based UK Biobank, reported that 49 out of 250, GWAS derived, prostate cancer (PCa) and BPH risk-associated SNPs were significantly (p=0.05) associated with the risk of both diseases. The extent to which the observed BPH disparities in African American men is driven by ancestry linked genomic alterations has not been established. The ancestral populations of African American men are in countries along the Atlantic coast of Africa, especially Nigeria10, 11. To date, no BPH genomic studies have been done to characterize the disease within Nigerian (NGRn) men. Having such data would be informative of any ancestral genetic links associated with BPH and any cross-disease genetic associations between BPH and PCa. We previously reported African ancestry associated PCa germline and somatic alterations that diminished DNA damage repair in Men of African ancestry12. In the current study, we used whole exome sequencing of 60 NGRn archival BPH samples to not only characterize the disease within NGRn men but to also validate the previously reported alterations that could reveal a link between BPH and PCa in men of African ancestry.

Methods

Sample Collection and Genomic DNA Extraction.

This study utilized 60 FFPE benign prostatic hyperplasia, 11 non-tumor prostate and 45 tumor samples collected from six participating clinical sites within the CaPTC network (Supplemental Table 1). In accordance with the U.S. Common Rule, the archived samples used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of their respective clinical institutions (University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, National Hospital Abuja, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Federal Medical Centre, and Ahmadu Bello University) and by the Institutional Review Board at Tuskegee University. Due to the retrospective nature of this study and the usage of de-identified archived samples, the review boards deemed informed written consent to be unnecessary for this study. Five 10 μm-thick curls were obtained and shipped to Q2 Solutions (Morrisville, NC) for DNA extraction and quality analysis. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, genomic DNA and total RNA were purified using Allprep DNA/RNA FFPE kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA quality and quantity were checked with Qubit 2.0 fluorometry (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and with KAPA hgDNA quantification and QC kits (Kappa Biosystems [Roche], Basel, Switzerland). DNA quality and quantity thresholds were >0.2 μg and a Q129/Q41 ratio >0.00225, respectively.

Whole exome sequencing (WES).

Library preparation was performed using Agilent SureSelectXT Human All Exon V6 r2 Exome Kits (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequencing (2×150 bp) was performed on either an Illumina HiSeq4000 or on an Illumina NextSeq500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), to a target of 100 (± 10) million raw data reads per each sample library. Following sequencing, raw fastq files were transferred to the NIH Biowulf supercomputing cluster and analysed using the Center for Cancer Research Collaborative Bioinformatics Resource (CCBR) Whole Exome pipeline (https://github.com/CCBR/Pipeliner). Reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.3313 and mapped to the hs37d5 version of the human reference genome (ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/technical/reference/phase2_reference_assembly_sequence/hs37d5.fa.gz) using BWA-MEM v07.1714. Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files were processed using Samtools v1.8 (http://www.htslib.org/)15, and Picard v1 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was used to mark duplicates. GATK v3.816 was used to perform indel realignment and base recalibration. Read and alignment-level quality analysis was performed using Qualimap v2.2.117. Alignment quality metrics were analysed and visualized using RStudio 1.2.5003 (http://www.rstudio.com) [R 3.6.3 (https://www.R-project.org)], the ggstatsplot v0.3.0 (https://indrajeetpatil.github.io/ggstatsplot/) package, and the compareGroups v4.2.018 package.

Genetic Admixture Estimation.

HaplotypeCaller19 and Admixture v1.3.020 was used to estimate ancestry proportions, based on reference populations from the 1000 Genomes Project phase 3° superpopulations. Rare variants (i.e., <5% across all phase 321 1000 genomes), all INDELs and any SNPs that were not biallelic were removed prior to analysis.

Variant Calling and Filtration.

With a few modifications, variant calling and filtering methods followed those used in our previous NGRn prostate cancer study12. Germline variant calling was completed using HaplotypeCaller22, and Annovar v2019Oct24 was used for variant annotation. Variant filtration followed GATK Best practices16. Cohort single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels were separated, filtered. and recombined for downstream analysis. SNP filters were Qual < 30.0, QD < 2.0, FS > 60.0, MQ < 40.0, MQRanksum < −12.5, and ReadPosRankSum < −8.0. Indel filters were Qual < 30.0, QD < 2.0, FS > 200.0, and ReadPosRankSum < −20.0. Once the variants were recombined, cohort germline variants were compared to a ClinVar-derived list (downloaded Oct 2022) of known PCa-associated variant regions (Supplemental Table 2) to target variants of known clinical importance. Germline variants with a read depth > 3 and a variant allele frequency > 50% were retained for downstream analysis (Supplemental Figure 1). Somatic variant calling was completed using MuTect223, and Annovar v2019Oct2424 was used for variant annotation. As described by Jones et al., a single unmatched NGRn normal FFPE exome was paired with each BPH exome to filter false-positive variant calls25. Mutation tables were imported into RStudio for visualization and analysis using the maftools26 (v2.4.10) package. Variants were 1] screened for strand bias using GATK FisherStrand Phred Score, 2] separated into variants within known PCa-associated genes and variants within novel PCa-associated gene, using the ClinVar derived list of clinically actionable variants and 3] and filtered using two filtering regimes. After filtering, retained variants within genes identified in ClinVar were considered “Known”; conversely, variants within genes not identified in ClinVar were called “Novel”. Filtering steps included 1] exclusion of silent and non-protein coding mutations, 2] variant allele read depth ≥3, 3] variant allele frequency >5% [10% for variants within novel PCa associated genes], 4] dbNSFP27 Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)28 exome allele frequency < 0.01 [< 0.001 for variants within novel PCa-associated genes and variants lacking allele frequencies were retained for downstream filtration], 5] not identified as Benign or likely Benign in ClinVar v 2020041929, 6] removal of dbSNP-annotated variants identified in NGRn unmatched normal samples (n = 11), 7] present in genes altered in least 2 BPH samples, and 8] manual validation in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (Supplemental Figure 2).

Mutation Frequency and Interactions.

For genes or variants mutated across at least five samples, Within maftools, Fisher’s exact test was used to compare cohort mutation/variant frequencies and interactions. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

COSMIC Signature Enrichment.

Using the maftools package, filtered single nucleotide variants across each cohort was used to estimate the representation of Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) (cancer.sanger.ac.uk)30 mutation signatures within each tumor sample. Maftools uses cophenetic correlation and nonnegative matrix factorization to determine the optimal number of SNV signatures (across the cohort), extracts those signatures and compares them to the known (n=30) COSMIC signatures.

Results

To determine the somatic and germline variants associated with BPH in NGRn men we collected formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples from multiple institutions within the CaPTC. Specifically, we collected 60 BPH samples, 45 intermediate (Gleason scores 4+3) and high-grade (Gleason scores ≥ 4+3) tumors and 11 non-tumor unmatched prostate samples. 31 samples were collected from Northern Nigeria, 67 samples from Central Nigeria, and 18 samples from Southwest Nigeria (Supplemental Table 1).

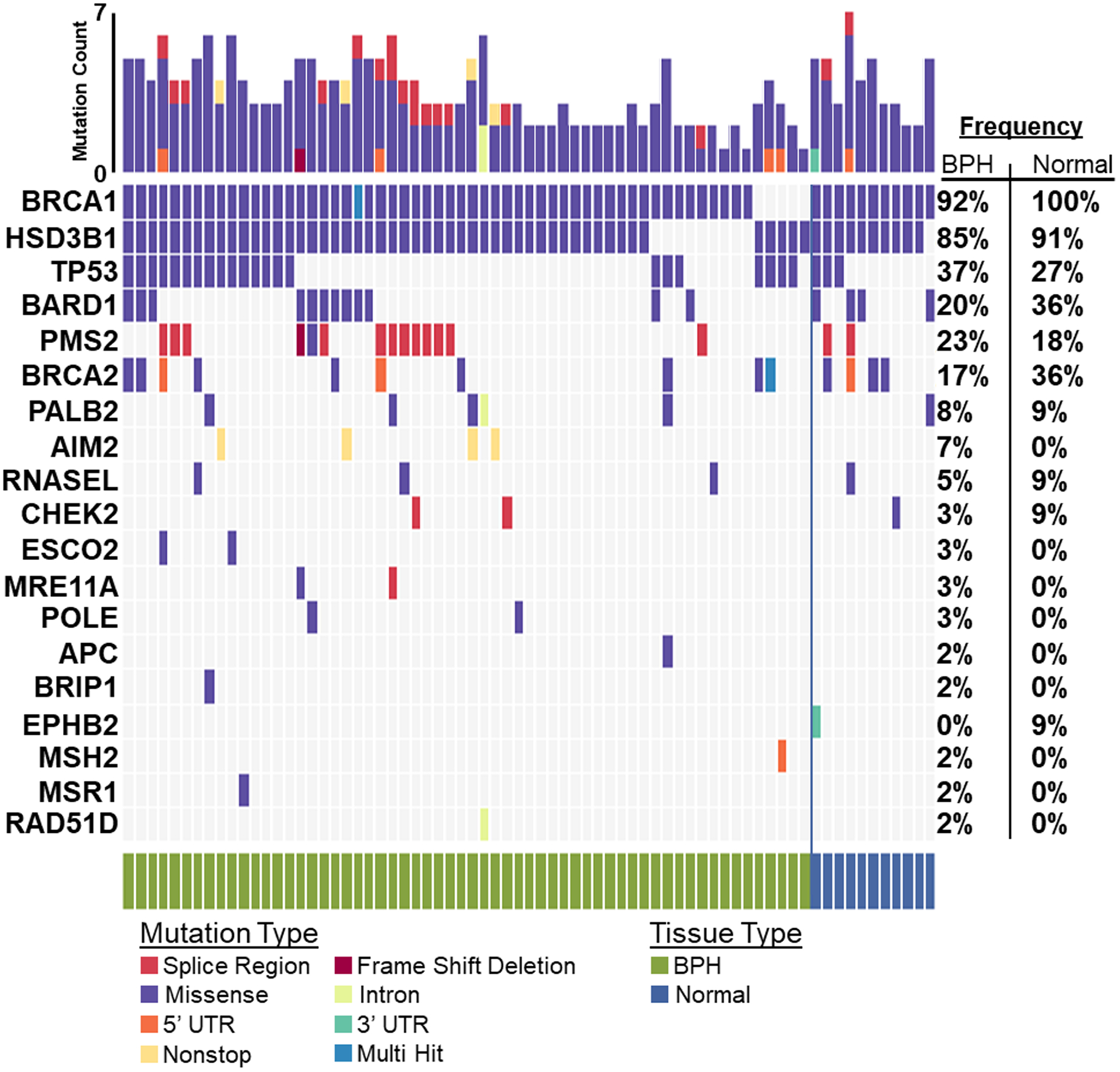

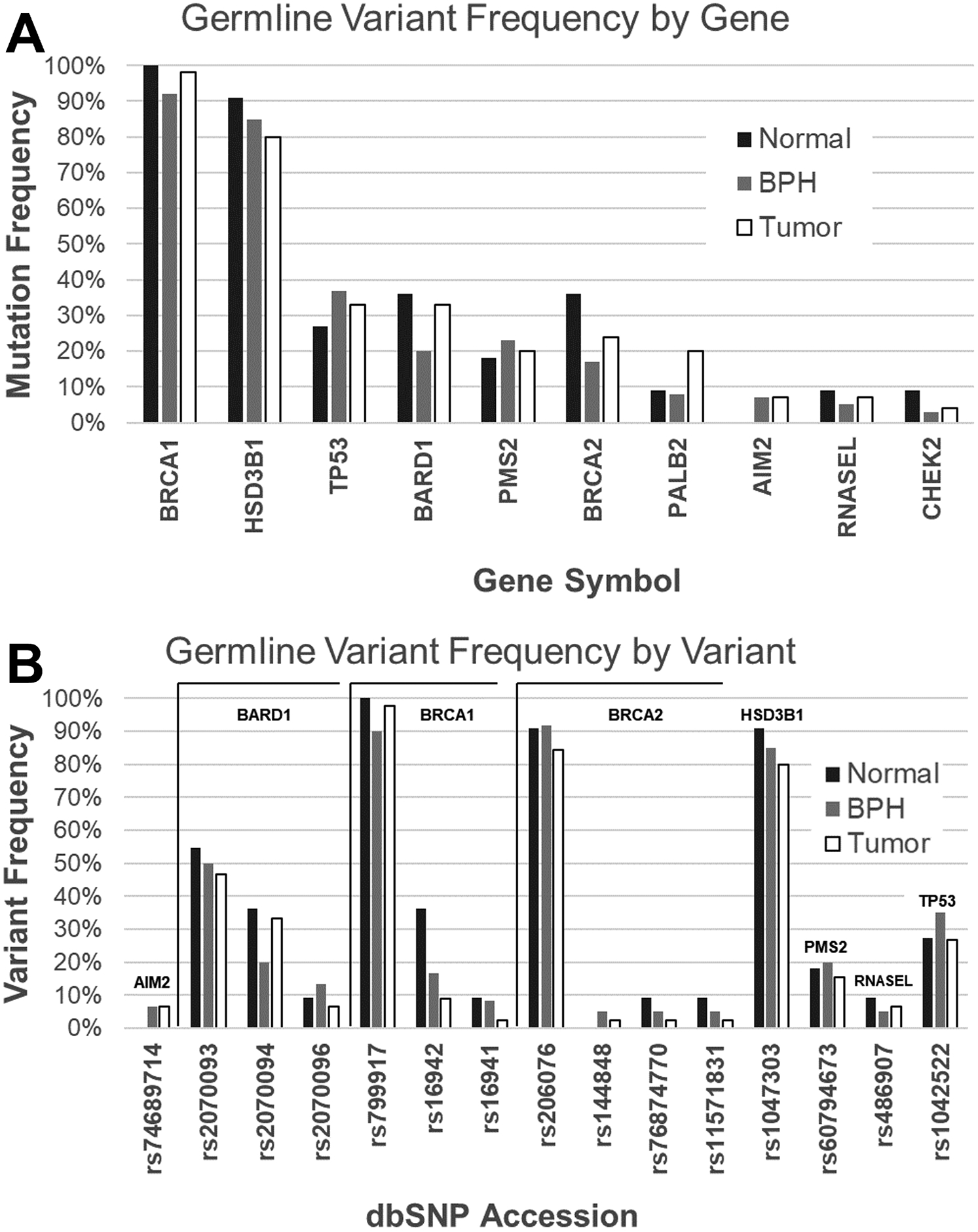

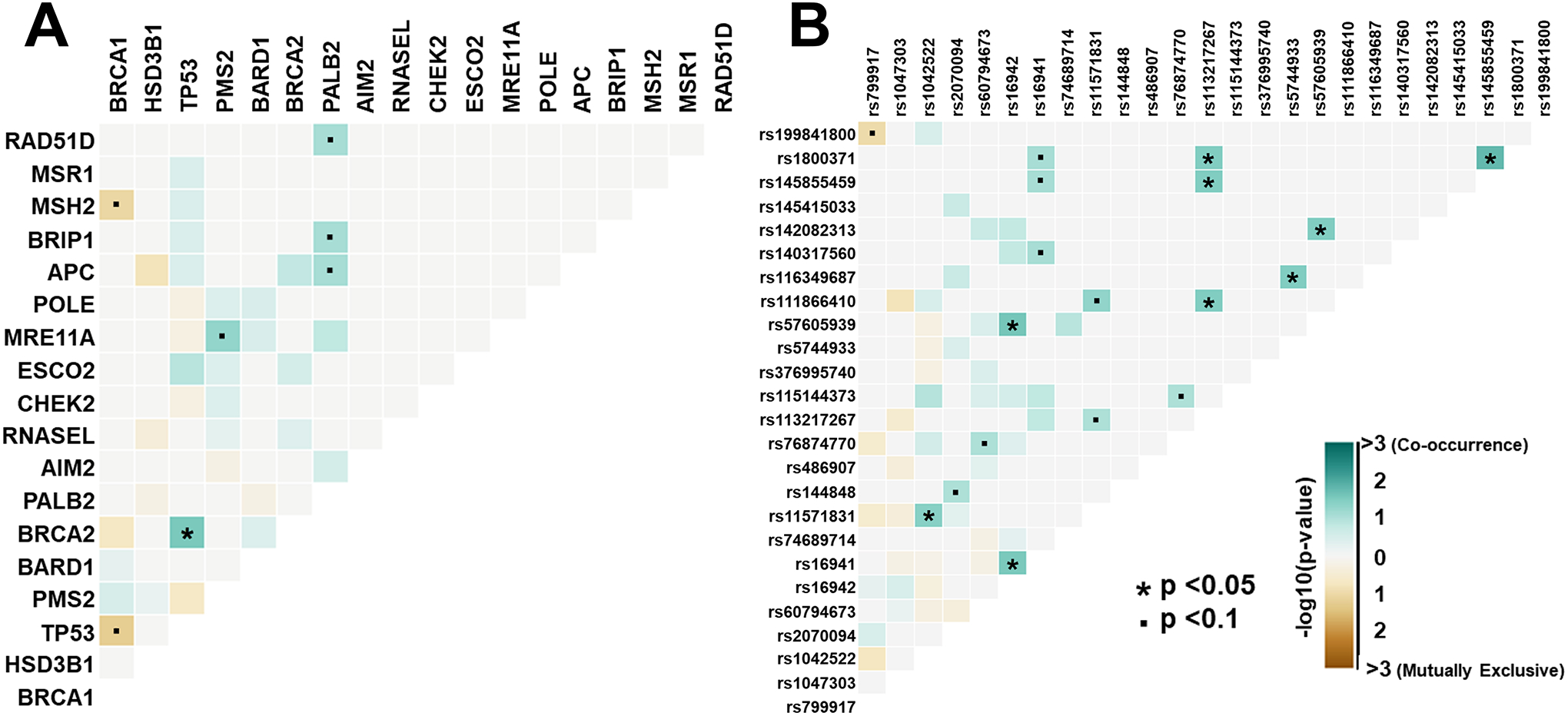

Across 13 genes, NGRn BPH harboured 202 non-benign, ClinVar annotated germline variants altered in at least two samples (Figure 1). Six genes [BRCA1 (92%), HSD3B1 (85%), TP53 (37%), PMS2 (23%), BARD1 (20%) and BRCA2 (17%)] were altered in at least 10% of samples. Compared to normal and tumor, the frequency of alterations in BPH samples showed no significant differences at the gene or variant level (Figure 2). TP53 and BRCA2 had a statistically significant co-occurrence interaction in BPH samples (Figure 3A and Supplemental Table 3). Five gene pair interactions had p-values approaching (p <0.1) significance. Three (MRE11A/PMS2, APC/PALB2 and BRIP1/PALB2) of the five were co-occurring and two (TP53/BRCA1 and MSH2/BRCA1) were mutually exclusive. The gene pair interactions observed in NGRn BPH showed either no significance or no interaction in NGRn normal or NGRn PCa tumor samples. Nine variant pairs showed significant (p < 0.05) interactions and nine approached significance (p <0.1) (Figure 3B and Supplemental Table 4). Like gene level interactions, the variant pair interactions observed in BPH showed either no significance or no interaction in NGRn normal or NGRn PCa tumor samples.

Figure 1: BPH and Normal Germline Variant Oncoplot.

Germline variants detected across 60 BPH and 11 unmatched normal samples were filtered against a list of non-benign variants catalogued by ClinVar. In at least two samples, 13 genes harboured variants. The top five most frequently mutated genes in BPH were BRCA1 (BRCA1 DNA Repair Associated) – 92%, HSD3B1 (Hydroxy-Delta-5-Steroid Dehydrogenase, 3 Beta- And Steroid Delta-lsomerase 1) – 85%, TP53 – 37%, PMS2 (PMS1 Homolog 2, Mismatch Repair System Component) – 23% and BARD1 (BRCA1 Associated RING Domain 1) – 20%. BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Figure 2: Gene and Variant Level Germline Mutation Frequencies.

Gene and variant level germline mutation frequencies were compared between NGRn cohorts, unmatched normal (n = 11), BPH (n = 60) and PCa tumor (n = 45) samples. No significant differences in frequencies were detected at the, A) gene or B) variant level. NGRn – Nigerian, BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, PCa – Prostate Cancer

Figure 3: BPH Germline Gene and Variant Interactions.

Fisher exact tests were used to determine gene and variant pair interactions within BPH samples. A) TP53 and BRCA2 showed a statistically significant (p = 0.028) co-occurrence interaction with an odds ratio of 5.27. Six gene pairs showed interactions approaching significance (p <0.1). B) Nine variant pairs showed statistically significant (p < 0.05) interactions and 9 had interactions approaching (p ≤ 0.1) significance. The variant pairs with the most statistically significant interactions were, 1) TP53_rs 1800371 and BRIP1_rs145855459, 2) PALB2_rs57605939 and BRCA1_rs16942 and 3) BRCA1_rs16942 and BRCA1_rs16941. BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

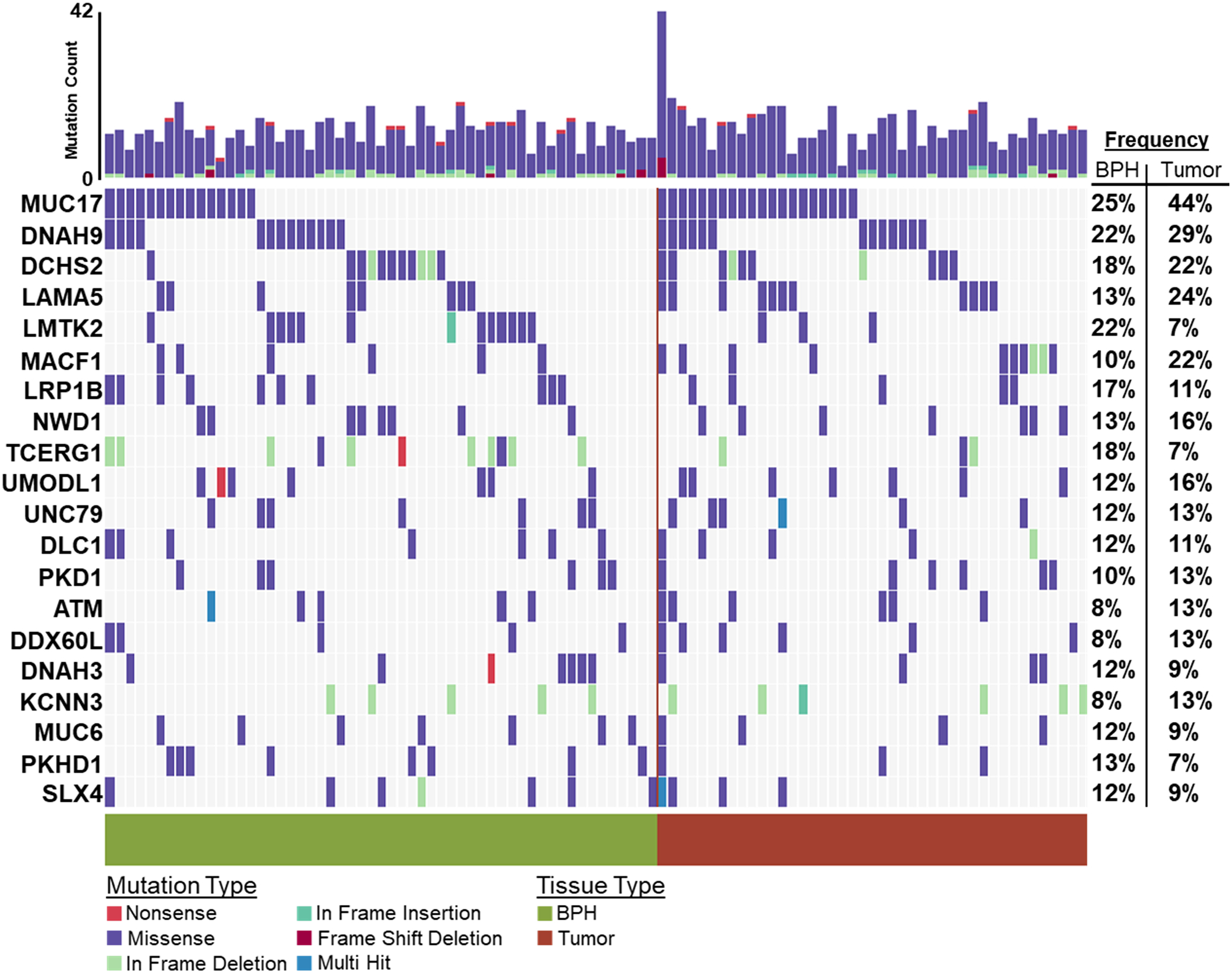

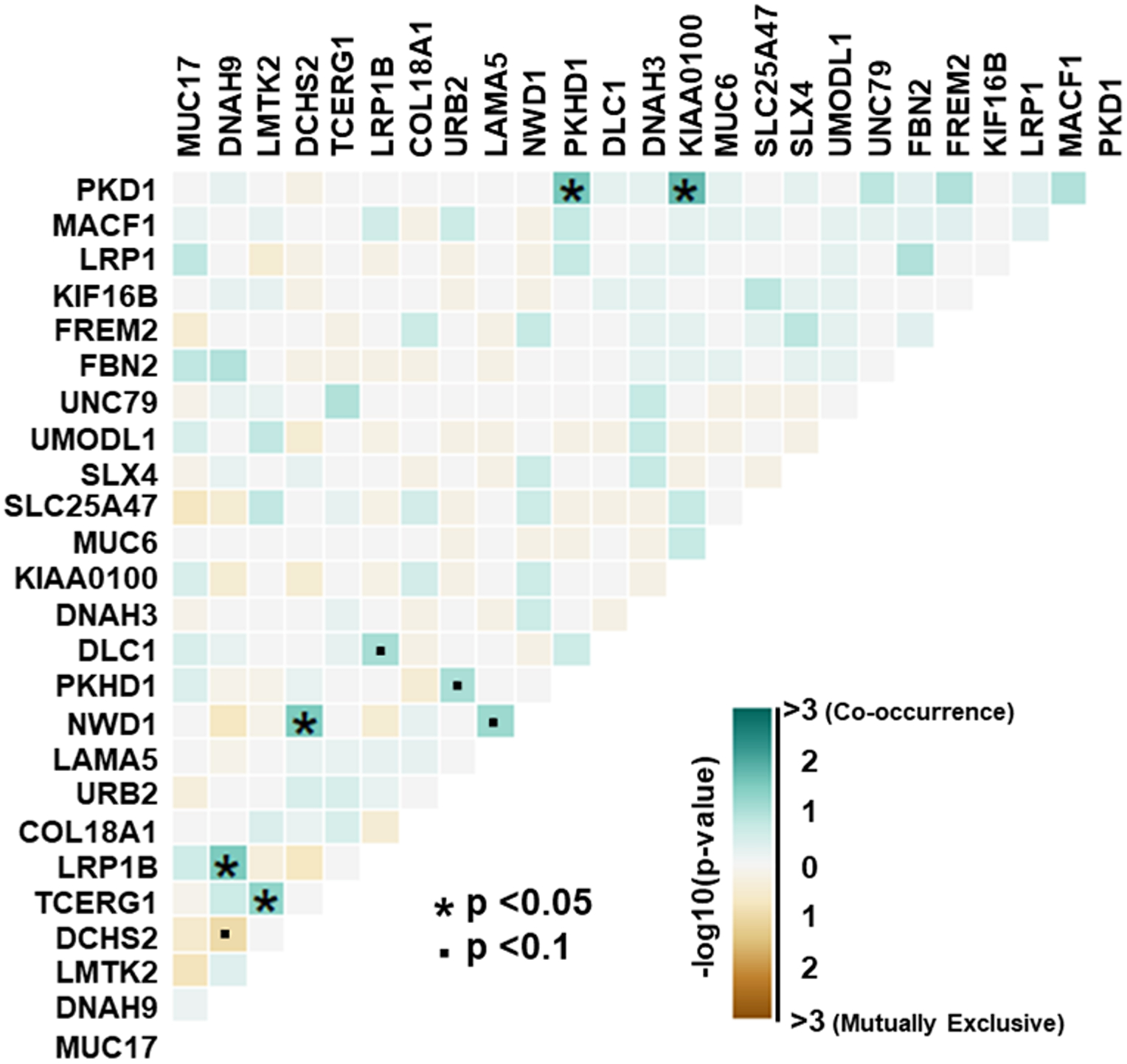

In at least two BPH samples, the top five most frequently somatically altered genes were MUC17 (Mucin 17 Cell Surface Associated) – 25%, DNAH9 (Dynein Axonemal Heavy Chain 9) – 22%, LMTK2 (Lemur Tyrosine Kinase 2) – 22%, DCHS2 (Dachsous Cadherin-Related 2) – 18% and TCERG1 (Transcription Elongation Regulator 1) – 18%. (Figure 4). Comparing gene alteration frequencies between NGRn BPH and NGRn PCa tumor, MUC17 and LMTK2 had frequency differences approaching statistical significance (Supplemental Table 5). MUC17 alteration frequency was higher in NGRn tumor and LMTK2 was higher in BPH. DNAH9, DCHS2 and TCERG1 showed no difference. In total, 8 genes (SDK1, COL18A1, AXIN2, EGFR, PLEKHG4B, PTPRJ, KIF16B and LRP1) showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference. BPH gene alteration frequencies were higher in COL18A1, KIF16B and LRP1. In addition, 4 genes (CCDC171, EHBP1, OR4C12 and APC) showed higher BPH alteration frequencies approaching significance (p < 0.08). In addition to comparing alteration frequencies, each cohort was tested for the presence of gene pairs with co-occurring or mutually exclusive gene interactions. NGRn BPH had five gene pairs (PKD1/KIAA0100, PKHD1/PKD1, DNAH9/LRP1B, NWD1/DCHS2 and TCERG1/LMTK2) with statistically significant (p < 0.05) co-occurring interactions and four interactions (three co-occurring [NWD1/LAMA5, DLC1/LRP1B and PKHD1/URB2] and one mutually exclusive [DCHS2/DNAH9]) approaching significance (p < 0.10) (Figure 5 and Supplemental Table 6) in genes containing clinically actionable somatic variants. In NGRn tumor samples, the nine interacting BPH gene pairs showed either no interaction or no significant interaction; however, NGRn tumor did have twelve known gene pairs with co-occurring interactions that were either significant or approaching significance (Supplemental Figure 3A and Supplemental Table 7)

Figure 4: BPH and Tumor Known Somatic Variant Oncoplot.

60 NGRn BPH and 45 NG Tumor were analyzed for somatic variants. Variants were filtered against a list of NG normal and non-benign ClinVar variants. In at least two BPH samples, 173 genes harbored variants. The top five most frequently mutated genes were MUC17 (Mucin 17 Cell Surface Associated) − 25%, DNAH9 (Dynein Axonemal Heavy Chain 9) − 22%, LMTK2 (Lemur Tyrosine Kinase 2) – 22%, DCHS2 (Dachsous Cadherin-Related 2) − 18% and TCERG1 (Transcription Elongation Regulator 1) − 18%. NGRn − Nigerian, BPH − Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Figure 5: NGRn BPH Gene Interactions in Known PCa Associated Genes.

Within BPH samples, genes containing clinically actionable somatic variants were analyzed for the presence of gene pairs with co-occurring or mutually exclusive interactions. Pairwise Fisher’s exact tests showed five gene pairs with statistically significant (p < 0.05) co-occurring interactions and four interactions (three co-occurring and one mutually exclusive) approaching significance (p < 0.10). NGRn – Nigerian, BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, PCa – Prostate Cancer

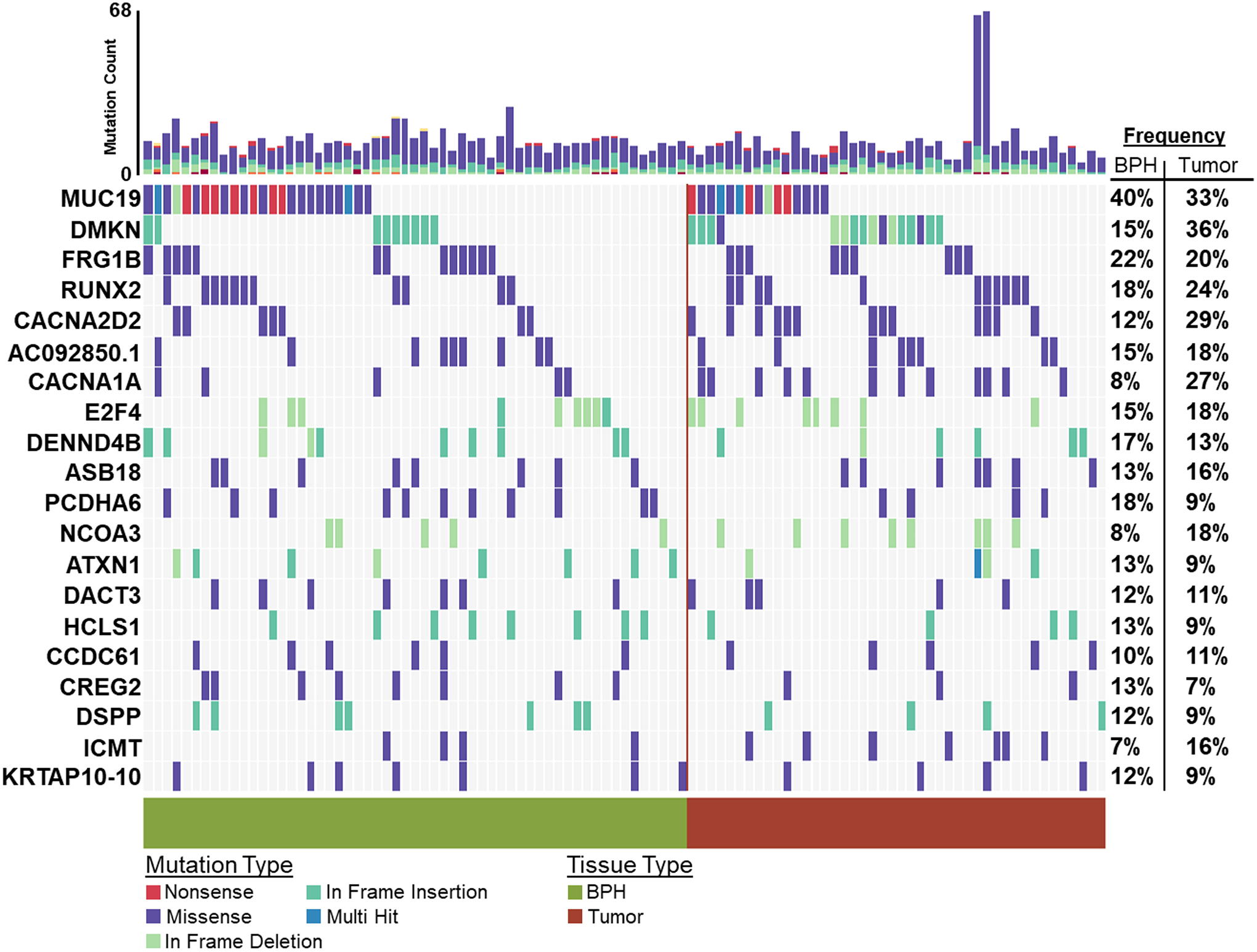

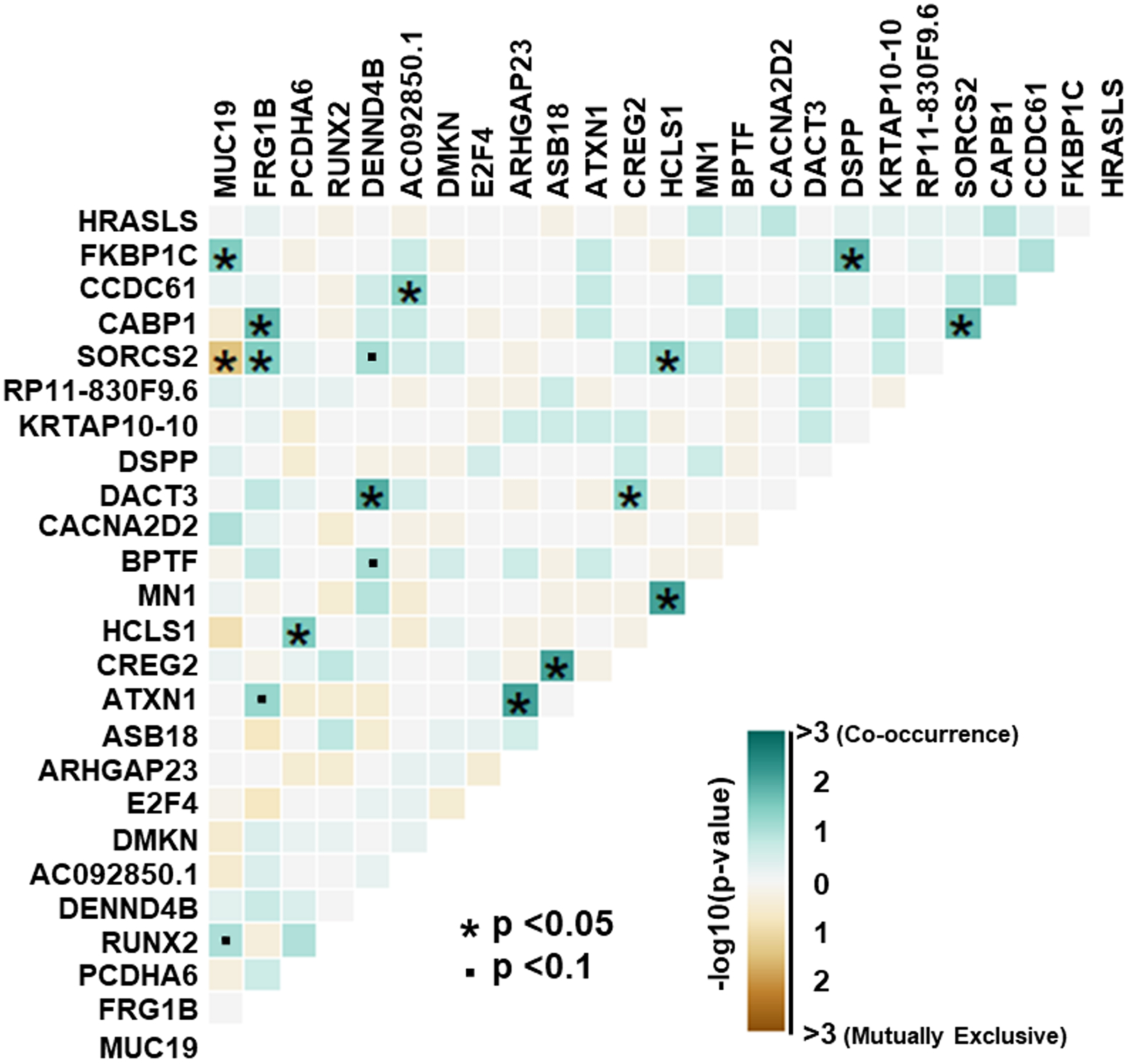

Due to the lack of published sequencing, data in Nigerian BPH we also sought to characterize somatic variants that are not currently clinically actionable. 279 genes contained novel somatic variants in at least 2 NGRn BPH samples. The top five most frequently mutated genes were MUC19 (Mucin 19, Oligomeric) – 40%, FRG1B (LOC102724813) – 22%, RUNX2 (RUNX Family Transcription Factor 2) – 18%, PCDHA6 (Protocadherin Alpha 6) – 18% and DENND4B (DENN Domain Containing 4B) – 17% (Figure 6). Three genes (CABP1, FKBP1C and RP11–595B24.2) showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) higher alteration frequency NGRn BPH and three were significantly higher in NGRn tumor (CACNA1A, DMKN and CACNA2D2) (Supplemental Table 8). Four genes (KANK3, LRRC53, MUC4, and NOTCH4) had frequency differences approaching significance (p < 0.10). KANK3 and LRRC53 frequencies were higher NGRn BPH and MUC4 and NOTCH4 were higher in NGRn tumor. Like the analysis of the known somatic variants we also assessed the novel variants for gene pair interactions. Pairwise Fisher’s exact tests showed fourteen gene pairs with statistically significant (p < 0.05) interactions and four interactions approaching significance (p < 0.10). SORCS2/MUC19 was the only interaction identified as mutually exclusive (Figure 7). Two of the observed NGRn BPH gene interactions were identified in NGRn PCa tumor samples; however, those interactions were not statistically significant (Supplemental Table 9). NGRn tumor samples had six statistically significant novel gene pair interactions and nine interactions approaching significance. All significant interactions were co-occurring. Of the nine novel interactions, three were mutually exclusive and six were co-occurring (Supplemental Figure 3B and Supplemental Table 7).

Figure 6: BPH and Tumor Novel Somatic Variant Oncoplot.

60 NGRn BPH and 45 NGRn Tumor samples were analyzed for somatic variants not known to be clinically actionable. In at least two BPH samples, 279 genes harbored novel variants. The top five most frequently mutated genes were MUC19 (Mucin 19, Oligomeric) – 40%, FRG1B (LOC102724813) – 22%, RUNX2 (RUNX Family Transcription Factor 2) – 18%, PCDHA6 (Protocadherin Alpha 6) – 18% and DENND4B (DENN Domain Containing 4B) – 17%. NGRn – Nigerian, BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Figure 7: NGRn BPH Gene Interactions in Novel PCa Associated Genes.

Within NGRn BPH samples, genes not known to contain clinically actionable somatic variants were analyzed for the presence of gene pairs with co-occurring or mutually exclusive interactions. Pairwise Fisher’s exact tests showed fourteen gene pairs with statistically significant (p < 0.05) interactions and four interactions approaching significance (p < 0.10). SORCS2/MUC19 was the only interaction identified as mutually exclusive. NGRn – Nigerian, BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, PCa – Prostate Cancer

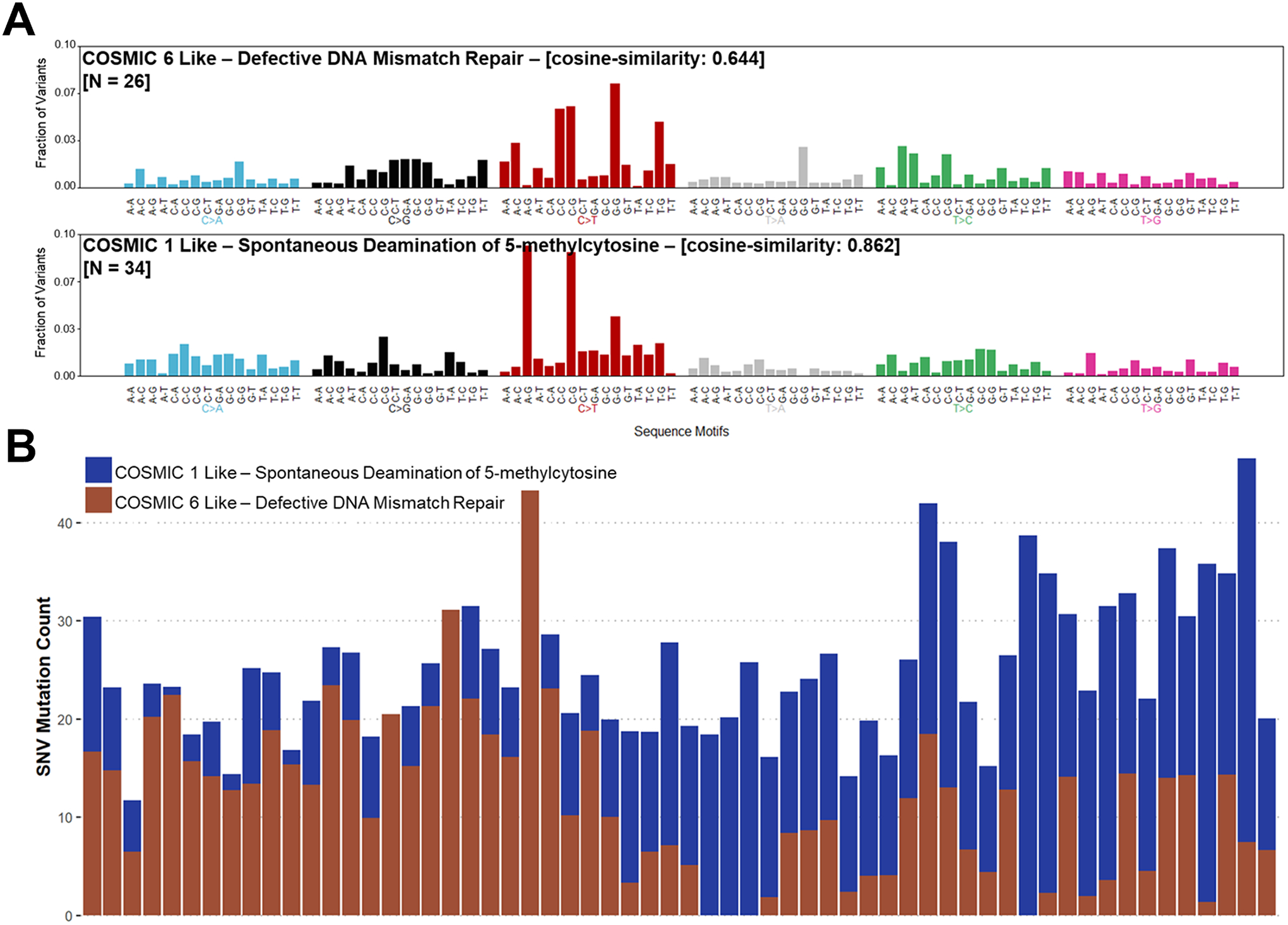

Lastly, we sought to characterize and compare the overall somatic single nucleotide variations (SNV) mutational patterns of NGRn BPH and PCa tumors. Mutational patterns in NGRn BPH were similar to COSMIC signature 1 (cosign similarity ≥ 0.862) and 6 (cosign similarity ≥ 0.644) (Figure 8A). Both signatures are characterized by C>T substitutions at NpCpG trinucleotides and are associated with aging and dysfunctional DNA damage repair. 34 BPH samples were composed predominantly of substitutions associated with signature 1. The remaining samples were predominantly signature 6 (Figure 8B). NGRn Tumor mutation patterns were similar to signatures 1 (cosign similarity ≥ 0.717) and 5 (cosign similarity ≥ 0.758) (Supplemental Figure 4A). Signatures 1 and 5 are two of the most often observed mutational patterns in prostate cancer. 31 samples were composed predominantly of substitutions associated with signature 1 (Supplemental Figure 4B). 14 samples were predominantly signature 14.

Figure 8: NGRn BPH COSMIC Gene Signature.

Single nucleotide variations in the Nigerian BPH cohort were compared to known cancer related mutation signatures within the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC). A) Nigerian BPH mutation patterns are similar to signatures 1 (cosign similarity ≥ 0.862) and 6 (cosign similarity ≥ 0.644). Both signatures are signatures are characterized by C>T substitutions at NpCpG trinucleotides and are associated with aging and dysfunctional DNA damage repair. B) 34 samples were composed predominantly of substitutions associated with signature 1. The remaining samples were predominantly signature 6. NGRn – Nigerian, BPH – Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to perform whole exome sequencing on Nigerian benign prostatic hyperplasia samples. Analysing 60 NGRn BPH, 11 normal NGRn prostate and 45 Nigerian PCa samples we identified germline and somatic variants that help to characterize BPH in Nigerian men. This work also provides additional validation of population specific variants in men of African ancestry that we have identified previously. BPH can have a significant negative impact on the lives of aging men. That impact is even more pronounced in men of African ancestry; however, they are severely underrepresented in studies investigating the underlying biology of BPH and the LUTS that it can cause. This work addresses that understanding gap and sets a foundation from which meaningful clinical interventions can be developed for this patient population.

Within NGRn BPH we observed a significant co-occurrence between germline variants BRCA2_rs11571831 and TP53_rs1042522, that was not present in NGRn normal or NGRn PCa samples. According to ClinVar, BRCA2_rs11571831 has conflicting clinical significance. However, we have previously identified it as a variant specific to men of African ancestry12. TP53_rs1042522 also shows conflicting clinical significance in ClinVar; however, this variant has been shown to affect the structure and function of TP5331, 32. Moreover, Osorio et al. reported that when TP53_rs1042522 is present in BRCA2 mutation carriers apoptotic activity is reduced in breast cancer33. Normal prostate development is maintained by balancing apoptotic and proliferative activity34. Dysfunction in either mechanism can lead to abnormal prostate growth. Taken together, these findings suggest that one of the genomic mechanisms underlying NGRn BPH is a disruption of prostate cellular maintenance in patients harbouring TP53_rs1042522 and BRCA2_rs11571831.

Our analysis also identified increased somatic mutation frequency of apoptosis-related genes in NGRn BPH, compared to NGRn PCa tumors. Specifically, LMTK2, LRP1 and COL18A1 demonstrated increased alteration frequencies in NGRn BPH that were significant or approaching significance. Of these genes, LMTK2 was identified as a susceptibility gene associated with prostate cancer in a large genome-wide association study (GWAS)35. LMTK2 is a serine/threonine kinase that can regulate cellular sensitivity to apoptosis by modulating BCL2 family members36 and BCL2 has been determined to play an important role in the onset of BPH37. In addition to impacting apoptotic pathways, loss of LMTK2 has been strongly associated with increased AR activity in prostate hyperplasia and cancer38. AR plays a well-documented role in BPH development39 and is more highly expressed in BPH samples from men of African descent40. LRP1 (aka IGFBP-3R) is a single-span membrane protein that specifically binds IGFBP-3 and induces apoptosis in caspase-8-dependent manner41. LRP1 activity alters apoptosis by directly binding TGFβ42, 43 and through the triggering ERK phosphorylation44. COL18A1 is an extracellular matrix protein that codes for the alpha chain of type XVIII collagen. In endothelial cells, COL18A1 induces apoptosis by altering BCL2 expression45. It can also impact apoptotic pathways through regulation of TNF-α46, 47. The increased frequencies of these alterations in NGRn BPH, as compared to BG PCa tumor, would suggest that these genes play a larger role in BPH progression than tumorigenesis; however, follow-up analysis is needed to validate this observation.

In addition to the known clinically annotated genes, NGRn BPH also contained significantly different somatic alteration frequencies in CABP1 (Calcium Binding Protein 1), and FKBP1C (FKBP Prolyl Isomerase Family Member 1C). These genes are not currently annotated in ClinVar, meaning they are variants of unknown significance (VUS). Non-European populations are known to have higher VUS rates48, 49. These gaps, coupled with the poorly understood pathophysiology of BPH increases the need for studies into disparately impacted patient groups. CABP1 is a calcium binding protein that shares similarities with calmodulin. Calcium signalling has been shown to be vital for normal prostate development and in vitro studies have demonstrated that calcium signalling disruptions can lead to BPH cell proliferation50, 51. A study in yeast also provides evidence that CABP1 can inhibit insulin aggregation52. Insulin has been linked to the pathogenesis of BPH, as such CABP1 alterations could limit insulin regulation and in turn enhance BPH development53, 54. FKBP1C is a member of a family of receptor accessory proteins that are involved in chaperone-mediated protein folding55. This family of isomerases contains a tetrtricopeptide repeat domain that allows them to interact and regulate HSP90 (Heat Shock Protein 90)56. Animal studies suggest that HSP90 can promote prostate hyperplasia by activating the classical complement pathway or by enhancing testosterone-induced nuclear AR expression57, 58. Whether these alterations are drivers or passengers in BPH progression requires more investigation; however, their increased frequency does justify that investigation.

The results of this study are foundational and important; however, this work does have noteworthy caveats. The lack of matched BPH controls and the high amount of inherent genetic diversity within African populations required a significant amount of variant filtering. This approach was necessary but increased the likelihood that true somatic variants were unintentionally excluded. Additionally, the unmatched normal controls were all collected from a single collection site; however, the BPH samples came from sites throughout central and southwest Nigeria. This collection site incongruence increases the difference in genetic background between the two comparison groups. This study is the first to examine genomic sequencing of Nigerian BPH and despite the limitations begins to fill important research gaps for an underserved patient population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Prostate Cancer Translatlantic Consoritium (including our community partners) and members of each respective lab that contributed to this study. We also thank members of the CCR Collaborative Bioinformatics Resource group (Mayank Tandon and Skyler Kuhn), Justin Lack of the NIAID Collaborative Bioinformatics Resource group, and numerous staff within the NIH High-Performance Computing group. This work was supported by funding from Leidos contract YT16-010 (Project ID# 001.050.0010); NCI contract HHSN261201600732P (University of Florida); NCI grants U54-MD007585-26 (NIH/NIMHD) and U54 CA118623 (NIH/NCI); and Department of Defense Grant (PC170315P1, W81XWH-18-1-0589) awarded to CYates.

Dr. Yates is a consultant for PreludeDX, QED Therapeutics, and Riptide Biosciences. Dr. Yates has received speaker fees from Regeneron and Amgen.

References

- 1.Bushman W, Etiology, epidemiology, and natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Clin North Am, 2009. 36(4): p. 403–15, v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calogero AE, et al. , Epidemiology and risk factors of lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia and erectile dysfunction. Aging Male, 2019. 22(1): p. 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glina S and Glina FP, Pathogenic mechanisms linking benign prostatic hyperplasia, lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction. Ther Adv Urol, 2013. 5(4): p. 211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry SJ, et al. , The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol, 1984. 132(3): p. 474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarma AV, et al. , Comparison of lower urinary tract symptom severity and associated bother between community-dwelling black and white men: the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status and the Flint Men’s Health Study. Urology, 2003. 61(6): p. 1086–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan SA, et al. , Is the ratio of transition zone to total prostate volume higher in African-American men than in their Caucasian or Hispanic counterparts? Br J Urol, 1998. 82(6): p. 804–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helfand BT, et al. , 1740 GENETICS VARIANTS THAT INCREASE SEVERE LOWER URINARY TRACT SYMPTOMS IN AFRICAN-AMERICAN MEN. Journal of Urology, 2013. 189(4S): p. e715–e715. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettaway CA, et al. , Benign prostatic hyperplasia: racial differences in treatment patterns and prostate cancer prevalence. BJU Int, 2011. 108(8): p. 1302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellwege JN, et al. , Heritability and genome-wide association study of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in the eMERGE network. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zakharia F, et al. , Characterizing the admixed African ancestry of African Americans. Genome Biol, 2009. 10(12): p. R141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatia G, et al. , Genome-wide comparison of African-ancestry populations from CARe and other cohorts reveals signals of natural selection. Am J Hum Genet, 2011. 89(3): p. 368–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White JA, et al. , Whole-exome Sequencing of Nigerian Prostate Tumors from the Prostate Cancer Transatlantic Consortium (CaPTC) Reveals DNA Repair Genes Associated with African Ancestry. Cancer Research Communications, 2022. 2(9): p. 1005–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolger AM, Lohse M, and Usadel B, Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 2014. 30(15): p. 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:1303.3997v1, 2013. [q-bio.GN] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, et al. , The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics, 2009. 25(16): p. 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna A, et al. , The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research, 2010. 20(9): p. 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Alcalde F, et al. , Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics, 2012. 28(20): p. 2678–2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subirana I, Sanz H, and Vila J, Building Bivariate Tables: The compareGroups Package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 2014. 57(12). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Auwera GA, et al. , From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics, 2013. 43: p. 11 10 1–11 10 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander DH, Novembre J, and Lange K, Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res, 2009. 19(9): p. 1655–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genomes Project C, et al. , A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 2015. 526(7571): p. 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DePristo MA, et al. , A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature Genetics, 2011. 43(5): p. 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cibulskis K, et al. , Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nature Biotechnology, 2013. 31(3): p. 213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, Li M, and Hakonarson H, ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research, 2010. 38(16): p. e164–e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones S, et al. , Personalized genomic analyses for cancer mutation discovery and interpretation. Science Translational Medicine, 2015. 7(283). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayakonda A, et al. , Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Research, 2018. 28(11): p. 1747–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, et al. , dbNSFP v3.0: A One-Stop Database of Functional Predictions and Annotations for Human Nonsynonymous and Splice-Site SNVs. Human Mutation, 2016. 37(3): p. 235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lek M, et al. , Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature, 2016. 536(7616): p. 285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landrum MJ, et al. , ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018. 46(D1): p. D1062–D1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tate JG, et al. , COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019. 47(D1): p. D941–D947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matlashewski GJ, et al. , Primary structure polymorphism at amino acid residue 72 of human p53. Mol Cell Biol, 1987. 7(2): p. 961–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas M, et al. , Two polymorphic variants of wild-type p53 differ biochemically and biologically. Mol Cell Biol, 1999. 19(2): p. 1092–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osorio A, et al. , A haplotype containing the p53 polymorphisms Ins16bp and Arg72Pro modifies cancer risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat, 2006. 27(3): p. 242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyprianou N, Tu H, and Jacobs SC, Apoptotic versus proliferative activities in human benign prostatic hyperplasia. Hum Pathol, 1996. 27(7): p. 668–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eeles RA, et al. , Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet, 2008. 40(3): p. 316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conti A, et al. , Lemur tyrosine kinase 2 (LMTK2) is a determinant of cell sensitivity to apoptosis by regulating the levels of the BCL2 family members. Cancer Lett, 2017. 389: p. 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavelic J, Zeljko Z, and Bosnar MH, Molecular genetic aspects of prostate transition zone lesions. Urology, 2003. 62(4): p. 607–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah K and Bradbury NA, Lemur Tyrosine Kinase 2, a novel target in prostate cancer therapy. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(16): p. 14233–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Izumi K, et al. , Androgen receptor roles in the development of benign prostate hyperplasia. Am J Pathol, 2013. 182(6): p. 1942–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoke G, et al. , Racial differences in pathogenetic mechanisms, prevalence, and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 2006. 68(5): p. 924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ingermann AR, et al. , Identification of a novel cell death receptor mediating IGFBP-3-induced anti-tumor effects in breast and prostate cancer. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(39): p. 30233–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang SS, et al. , Identification of insulin receptor substrate proteins as key molecules for the TbetaR-V/LRP-1-mediated growth inhibitory signaling cascade in epithelial and myeloid cells. FASEB J, 2004. 18(14): p. 1719–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tseng WF, Huang SS, and Huang JS, LRP-1/TbetaR-V mediates TGF-beta1-induced growth inhibition in CHO cells. FEBS Lett, 2004. 562(1–3): p. 71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muratoglu SC, et al. , Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) forms a signaling complex with platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta in endosomes and regulates activation of the MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(19): p. 14308–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhanabal M, et al. , Endostatin induces endothelial cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem, 1999. 274(17): p. 11721–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu W, et al. , Recombinant human endostatin inhibits adjuvant arthritis by down-regulating VEGF expression and suppression of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta production. Inflamm Res, 2012. 61(8): p. 827–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rath PC and Aggarwal BB, TNF-induced signaling in apoptosis. J Clin Immunol, 1999. 19(6): p. 350–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ndugga-Kabuye MK and Issaka RB, Inequities in multi-gene hereditary cancer testing: lower diagnostic yield and higher VUS rate in individuals who identify as Hispanic, African or Asian and Pacific Islander as compared to European. Fam Cancer, 2019. 18(4): p. 465–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDonald JT and Ricks-Santi LJ, Hereditary variants of unknown significance in African American women with breast cancer. PLoS One, 2022. 17(10): p. e0273835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maly IV and Hofmann WA, Calcium and Nuclear Signaling in Prostate Cancer. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang N, et al. , Regulation of Prostate Development and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia by Autocrine Cholinergic Signaling via Maintaining the Epithelial Progenitor Cells in Proliferating Status. Stem Cell Reports, 2016. 6(5): p. 668–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herbert AP, et al. , NMR structure of Hsp12, a protein induced by and required for dietary restriction-induced lifespan extension in yeast. PLoS One, 2012. 7(7): p. e41975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nandeesha H, et al. , Hyperinsulinemia and dyslipidemia in non-diabetic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Chim Acta, 2006. 370(1–2): p. 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z and Olumi AF, Diabetes, growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor pathways and association to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Differentiation, 2011. 82(4–5): p. 261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schiene-Fischer C and Yu C, Receptor accessory folding helper enzymes: the functional role of peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerases. FEBS Lett, 2001. 495(1–2): p. 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biebl MM and Buchner J, Structure, Function, and Regulation of the Hsp90 Machinery. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2019. 11(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hata J, et al. , Complement activation by autoantigen recognition in the growth process of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 20357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim HT, et al. , NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 silencing aggravates hormone-induced prostatic hyperplasia in mice. Andrologia, 2018. 50(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.