Abstract

Objective:

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL), also known as presbycusis, is a debilitating sensory impairment that affects the elderly population. There is currently no ideal treatment for ARHL. Long-term caffeine intake was reported to have anti-aging effects in many diseases. This study is to identify whether caffeine could ameliorate ARHL in mice and analyze its mechanism.

Methods:

Caffeine was administered in drinking water to C57BL/6J mice from the age of 3 months to 12 months. The body weight, food intake and water intake of the mice were monitored during the experiment. The metabolic indicators of serum were detected by ELISA. The function of the hearing system were evaluated by ABR and H&E staining of the cochlea. Genes’ expression were detected by Q-PCR, immunofluorescencee and western-blot.

Results:

The results showed that the ARHL mice exhibited impaired hearing and cochlear tissue compared to the young mice. However, the caffeine-treated ARHL mice showed improved hearing and cochlear tissue morphology. The expression of inflammation-related genes such as TLR4, Myd88, NF-κB, and IL-1β was significantly increased in the cochleae of ARHL mice compared to young mice but was down-regulated in the caffeine-treated cochleae.

Conclusion:

Inflammation is involved in ARHL of mice, and long-term caffeine supplementation could ameliorate ARHL through the down-regulation of the TLR4/NF-κB inflammation pathway. Our findings provide a new idea for preventing ARHL and suggest new drug targets for ARHL treatment.

Keywords: Age-related hearing loss, caffeine, inflammation, TLR4/NF-κB

Introduction

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is the most common sensory disorder in older individuals and is characterized by the loss of cochlear hair cells, degeneration of spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs), and damage to the stria vascularis (SV). ARHL can have a significant impact on the cognition and overall quality of life of the elderly(1). However, the exact molecular mechanism of ARHL were not fully understood, and to date, there is no ideal treatment for ARHL except for the use of hearing aids.

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a common characteristic of aging tissue and plays a crucial role in various age-related pathologies and natural processes(2). There are many inflammatory factors and pathways, and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is important for inflammation activation. Upon recognition of ligands, TLR4 undergoes oligomerization and interacts with its downstream adaptors, the TIR (Toll-interleukin-1 receptor) domains, MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88), and then activates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which translocates to the nucleus and initiates the transcription of target pro-inflammatory genes. The TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway is involved in many age-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease(AD), and Parkinson’s disease(PD)(3–5). Furthermore, TLR4 polymorphisms play an essential role in the innate immune response(6). Although many studies have provided clues regarding whether inflammation is involved in ARHL, systematic studies are still lacking.

Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) is the most frequently consumed psychoactive substance in the world, and over 80% of total caffeine consumption comes from coffee and other caffeine-containing beverages, including tea and energy drinks(7, 8). Long-term caffeine intake was reported to have anti-aging effects on many age related diseases. Consumption of caffeine reduced risk of developing PD, and daily intraperitoneal administration of caffeine attenuates the inflammatory process of PD mouse model(9, 10). And the beneficial effects of caffeine intake was also found in AD patients and AD animal models(11).Increased caffeine levels in the plasma are associated with reduced inflammatory cytokine levels in the hippocampus (12). Chronic administration of caffeine to a mouse model of progressive AD mitigates several pro-inflammatory markers in the hippocampus and prevents the development of spatial memory deficits(13).Of courese, moderate coffee consumption also can decrease the mortality risk of many other diseases, such as CVD,etc (14, 15). These studies suggest that caffeine has anti-aging effects and chronic administration of caffeine can inhibit chronic, low-grade inflammation in age-related diseases. However, it remains to be explored whether caffeine has a positive effect on ARHL and the mechanisms underlying the role of caffeine in ARHL.In the present study, we added caffeine to the drinking water of C57BL/6J mice for 9 months and found that long-term caffeine intake ameliorated ARHL. We then explored the molecular mechanism and found that TLR4/NF-κB pathway was involved.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

Forty-five male 2-month-old C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Pengyue Laboratory Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China) for this study. The mice were randomly divided into three groups, with 15 mice in each group: a 2-month-old control group (referred to as the “2 m group”), a 12-month-old control group (referred to as the “12m group”), and a 12-month-old caffeine group (referred to as the “12m-caffeine group”). From the age of 3 months to 12 months, the 12 m caffeine group received drinking water containing 0.025%caffeine. We calculate the dose of mouse by the body surface area calculation method(16), and it’s equivalent to adult human 400 mg/day, which is a safe dose recommended by Health Canada and the European Food Safety Authority(8, 17). The 12 m group was given normal drinking water. All mice were tested using an auditory brainstem response (ABR) test at the ages of 2-3 months, and the 12m and 12m-caffeine groups were also tested at 9 and 12 months of age. The body weight and water and diet intake of the mice were recorded from 3 to 5 months old. The mice were euthanized at 12 months old, and their blood and cochleae were collected. The 2m group was euthanized earlier, and their blood and cochleae were collected for comparison.

To collect the materials, the mice were deeply anesthetized, and blood was collected from the eye vein by rapidly removing the eyeball. The blood was then centrifuged to obtain the serum. The inner ear was decapitated and quickly removed. The entire cochlea was used, and the vestibular portions of the inner ear, including the utricle, saccule, and semicircular canal ampulla, were removed. The cochleae were stored in a refrigerator at −80 °C or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The serum was also stored in a refrigerator at −80 °C.

The individual body weight (g) of the mice was measured once every two weeks (n =15). To record the food intake, the initial food weight, the weight of added food (Wa) when it was needed to provide food supplementation, and the remaining food after 1 week were recorded. The food intake for that week (Wi+ Wa − Wr) was calculated, and this process was repeated every week. To record water intake, the initial gross weight of water (including the standard mouse drinking bottle and the autoclaved water filled with it, GWi) and the remaining gross weight of water (GWr) were recorded when a new bottle of water was needed to provide enough water for the mice. The water intake (GWi − GWr) was then calculated every week. Food and water intake were normalized to mouse number and days. However, the statistics of food and water intake were calculated by cage, that is, the obtained results were the average value of each cage (n=3).

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the principles of Laboratory Animal Care and the rules of the Scientific and Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University (approval no: 20171028).

Chemicals

Caffeine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Company (St.Louis, MO, USA).

Auditory brainstem response test

ABR was performed in a double-wall sound isolated chamber. Mice were tested following sedation by intraperitoneal injection of 4% chloral hydrate (0.48g/kg). Body temperature was maintained at 37–38 °C by placing anesthetized mice on an isothermal pad. Needle electrodes were placed subcutaneously at the vertex (active electrode), beneath the left pinna (ground), and beneath the right ear (reference electrode). Acoustic stimuli were delivered directly to the right ear by using a ER3C insert Earphone (M015302, IHS6874, USA) at low frequency and a high-frequency transducer (M014600 IHS6874, USA) at high frequency, and they were placed in front of the mice external auditory canal. Briefly, ABR was evoked using a computer-aided, evoked potential system (IHS3.30 Intelligent Hearing Systems, Miami, FL, USA) as described previously(18), by both clicks and series of pure tone stimuli of 8, 16, or 32 kHz. ABRs were obtained at each frequency beginning with 70 dB SPL by reducing the SPL in 10 dB steps until a threshold intensity that evoked a reproducible ABR waveform with an identifiable peak II. If ABRs were not evoked by the beginning 70 dB SPL, ABRs were obtained by increasing the SPL in 10 dB steps to a maximum presentation level of 110 dB SPL. If 110 dB SPL could not be evoked, a nominal threshold of 115 dB was assigned for the maximum. The level around threshold was adequately sampled (±5dB). Responses to as many as 1,024 stimuli were amplified for 10,000 times, filtered at 0.15-1.5 kHz, and sampled at all frequency with 16-bit depth. Importantly, the equipment during this longitudinal study was calibrated every six months in the Institute of Metrology and Testing of Beijing to obtain reliable experimental values. Two independent, experimentally blind observers recorded the ABR thresholds and obtained the same thresholds in most of mice, and any discrepancies were rarely more than 5 dB. To assess the status of hearing loss, we recorded the ABR at the ages of 3, 9, and 12 months.

Insulin (INS), Insulin-like growth factor-1(IGF-1) and glucose detection

The serum levels of INS and IGF-1 were measured by ELISA (mlbio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The serum levels of glucose were measured by GOPOD method (mlbio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. OD450 and OD520 were detected by microplate reader (Thermo, Multiskan FC).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

After being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, the cochlea was decalcified in 10% EDTA in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 3 (2m tissue) or 7 days (12m tissue), embedded in paraffin, cut into 5μm sections, and stained with H&E for microscopic observations. For the determination of the spiral ganglion neuronal density in the cochlea, the area of each spiral ganglion was measured, and morphologically intact spiral ganglion neurons (criteria: SGN with a large round nucleus and homogenous cytoplasm) in which the nucleus comprised 40% of the soma area were counted within this area. The total number of SGNs in each spiral ganglion explant was obtained by summing the SGN counts in all consecutive sections. The density of SGNs was then calculated per unit area (0.01 mm2). The thickness of SVs was also measured. Image J software was used for all quantitative analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR)

Total RNAs were extracted from the cochlear of C57BL/6J mice using TRIzol reagent (Abcam, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA synthesis was performed using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase kit (AG, USA). Q-PCR was performed using a SYBR green-based PCR master mix kit (AG, USA) on a BIO RAD CFX96 real-time PCR system. Gene expression was normalized to Tublin. The sequences of primers used in the experiments are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Immunofluorescence

After being deparaffinized and hydrated, the paraffin sections were fixed in 2% PFA, permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100, and blocked in 10% BSA solution. Then, the samples were incubated using a primary antibody (NF-κB, 1:1000, Cell Signaling). Next, they were incubated with the appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (1:800 goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 Fluor, ab150077, Abcam) and then counterstained with DAPI. Sections were imaged at a resolution of 1,024×1,024, with eight-bit sampling (no z increment was used) with a Leica 710, Zeiss, Germany, confocal microscope using a Plan-Apochromat 40×DIC objective, corrected for both chromatic and spherical aberrations. Negative controls consisted of secondary antibody only and unstained sections to assess for background staining and autofluorescence, respectively. Negative controls exhibited minimal staining or autofluorescence (data not shown). Observations with the confocal microscope were done with objectives of 10×, 20×, and 40× at wavelengths of 405 and 488 nm in blue/green channels with the same settings each time. The slices were observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica, Germany). Fluorescence intensities were quantified using the clock scan protocol in ImageJ.

Protein Extraction and Western blot

Tissues were lysed on ice with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.4)), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitor phosphatase inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture, Roche). Protein concentration was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Takara, T9300A), and equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the indicated primary antibodies (TLR4 (19811-1-AP, Proteintech), Myd88 (66660-1-Ig, Proteintech), NF-κB (8242, Cell Signaling), IL-1β (16806-1-AP, Proteintech), Tublin (11224-1-AP, Proteintech)). Signals were detected with Tanon-5200 Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon, Shanghai, China). The protein levels were analyzed by Image J (NIH, Bethesda, USA) and normalized to the corresponding Tublin level.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test, and comparisons between three or more sets of data were made using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Student-Bonferroni post hoc test. Difference with p < 0.05 was considered be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

1. Caffeine showed otoprotection against ARHL in C57BL/6J mice

In our study, we employed C57BL/6J mice as an animal model for age-related hearing loss (ARHL) due to their characteristic progressive hearing decline with age, as reported by Zhao et al. in 2020(19). To assess the potential protective effect of caffeine on hearing, we administered caffeine by drinking water to the mice and measured their auditory brainstem response (ABR) thresholds at 3 months, 9 months, and 12 months of age. The experimental design is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scheme of the experimental procedure: the mice were purchased at 2 months of age. Caffeine was added to the drinking water for mice from 3 months old to 12 months old. The control group received water regularly. ABR was measured at the age of 3 months, 9 months and 12 months. Water and food intake and body weight were measured from 3 months old to 5 months old.

|

The results indicated that in the control group, ABR thresholds increased with age for all tested stimulus frequencies (click, 8 kHz, 16 kHz, and 32 kHz), as illustrated in Fig. 1. Before the experiment, there was no difference in ABR thresholds between the caffeine-treated and control groups at 3 months of age. However, after receiving caffeine treatment for six months, the caffeine-treated mice showed lower ABR thresholds than the control group at the stimulus frequency of 32 kHz at 9 months of age(p=0.035, 51.92±11.28 vs 68.19±12.99 dBSPL) (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, after receiving caffeine treatment for nine months, the caffeine-treated mice exhibited significantly lower ABR thresholds than the control group at click, 8 kHz, and 32 kHz stimulus frequencies at 12 months of age(p=0.021,45.50±8.32 vs 59.15±15.63; p=0.034, 26.25±13.67 vs 39.23±16.05; p=0.041,74.58±7.53 vs 84.92±5.84 dBSPL,respectively) (Fig. 1). These findings suggest that moderate long-term caffeine consumption can potentially alleviate ARHL in C57BL/6J mice.

Fig. 1. Effects of caffeine on ABR thresholds of mice.

(A-D): ABR thresholds were measured by click and tone bursts (8, 16, 32 kHz) in mice at the ages of 3 months, 9 months and 12 months. Numerical values are means ± SDs or p value. 3 months and 9 months: n=15. 12 months: 12m group, n=15; 12m-caffeine group, n=13. *: p < 0.05.

2. Caffeine administration didn’t affect metabolic process of C57BL/6J mice

Previous studies have suggested that caffeine consumption may influence energy metabolism in animals(7, 20), although some scholars maintain a skeptical view(21). We aimed to investigate the effects of long-term caffeine treatment on body weight, food and water intake, and serum levels of insulin (INS), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and glucose in mice aged between 3 and 5 months.

Over the course of the study, both groups of mice showed a gradual increase in body weight (Supplemental Figure 1A), but there was no significant difference between the caffeine-treated group and the control group at any time point. Food consumption levels were also similar in both groups (Supplemental Figure 1B). Although the caffeine-treated group had higher water intake at the beginning of the experiment, the difference was not statistically significant and gradually converged over time (Supplemental Figure 1C). Serum levels of INS, IGF-1, and glucose were measured in the 2-month, 12-month, and 12-month caffeine-treated mice, and no significant differences were found among the three groups (Supplemental Figure 1D–F). These results suggest that long-term caffeine administration did not have a significant impact on the metabolism of the mice.

3. Caffeine improved the cochlear histomorphology of ARHL mice

To investigate the effect of caffeine on the cochlear histomorphology of mice, a histological study was conducted. The results revealed integral and undamaged hair cells, SGNs, and SVs in the 2-month (2 m) group (Fig. 2A, D, and G). In contrast, both SGNs and hair cells, especially outer hair cells (OHCs), were severely lost in 12-month (12 m) mice, regardless of caffeine treatment (Fig. 2B, C, E, and F).

Fig. 2. Effects of caffeine on the cochlear histomorphology of mice.

The morphology of the Corti organ. Black arrow: OHCs; red arrow: IHCs. (D-F) The morphology of the spiral ganglion. *: SGNs. (G-I) The morphology of SVs. Blue arrow: SVs. (J, K) Quantification analysis of the SGN density and SV thickness. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. n=6. *: p < 0.05, **: p <0.01. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Interestingly, the cochlear histomorphology of the caffeine-treated mice exhibited less OHC and SGN loss than that of the 12 m group (Fig. 2B, C, E, and F). The quantified density of SGNs also showed a similar trend (F=45.78, P<0.01) (Fig. 2J). Additionally, the width of SVs decreased significantly in the 12 m group compared to the 2 m group (Fig. 2G, H, I, and K) but was markedly increased in the 12 m caffeine-treated group (F=8.034, P<0.01) (Fig. 2G, H, I, and K).

4. Caffeine treatment inhibited inflammatory genes in the cochleae of ARHL mice

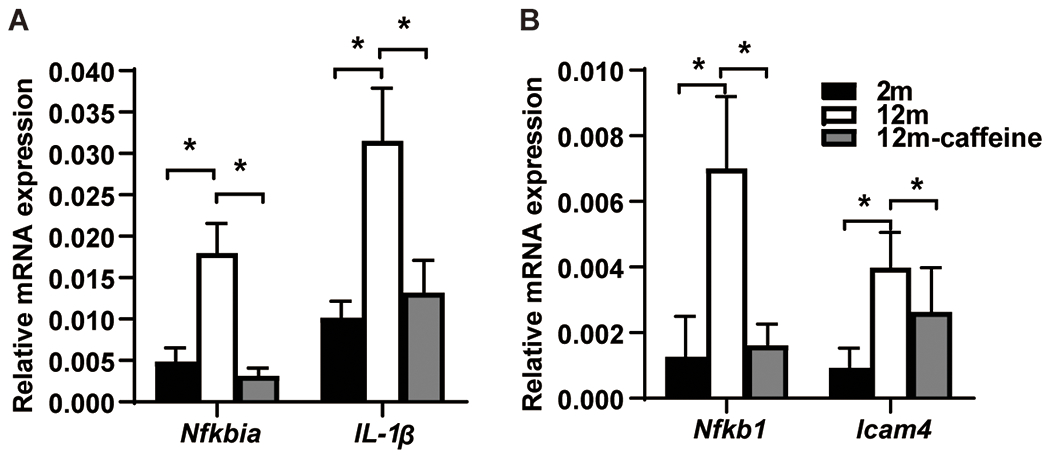

Based on previous reports suggesting that caffeine has anti-inflammatory properties and that age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is related to inflammation, we hypothesized that caffeine may have otoprotective effects by regulating inflammation-related genes. To test this hypothesis, we measured the expression levels of several inflammation-related genes in the cochleae using qPCR. We found that the mRNA levels of Nfkb1, Icam4, Nfkbia, and IL-1β were significantly increased in the 12-month group compared to the 2-month group (Fig. 3A and B), but were markedly down-regulated in the 12-month caffeine-treated group (Fig. 3A and B). There were no significant differences in the expression levels of these genes between the 2-month and 12-month caffeine-treated groups (Nfkb1: F=4.608, P<0.05; Icam4: F=2.103, P<0.05; Nfkbia: F=12.09, P<0.05; IL-1β: F=6.718, P<0.05) (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3. mRNA expression levels of Nfkbia, IL-1β, Nfkb1and Icam4 analyzed by Q-PCR.

Data shown as mean ± SD. n = 3; *: p < 0.05.

We also measured the protein expression levels of TLR4, Myd88, NF-κB, and IL-1β using Western blotting. The results showed that these genes were expressed in the cochleae of all three groups, and their protein levels increased in both 12-month groups compared to the 2-month group, regardless of caffeine treatment. However, compared to the 12-month control group, the protein levels of these genes decreased in the 12-month caffeine-treated group (TLR4: F=17.93, P=0.003; Myd88: F=38.81, P=0.001; NF-κB: F=36.62, P=0.001; IL-1β: F=8.034, P=0.004) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Protein expression levels of TLR4, Myd88, NF-κB and IL-1β analyzed by western blot.

(A) Immunoblotting of TLR4, Myd88, NF-κB and IL-1β protein levels. (B) Quantification analysis of TLR4, NF-κB, Myd88 and IL-1β protein levels. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. n = 3; *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01.

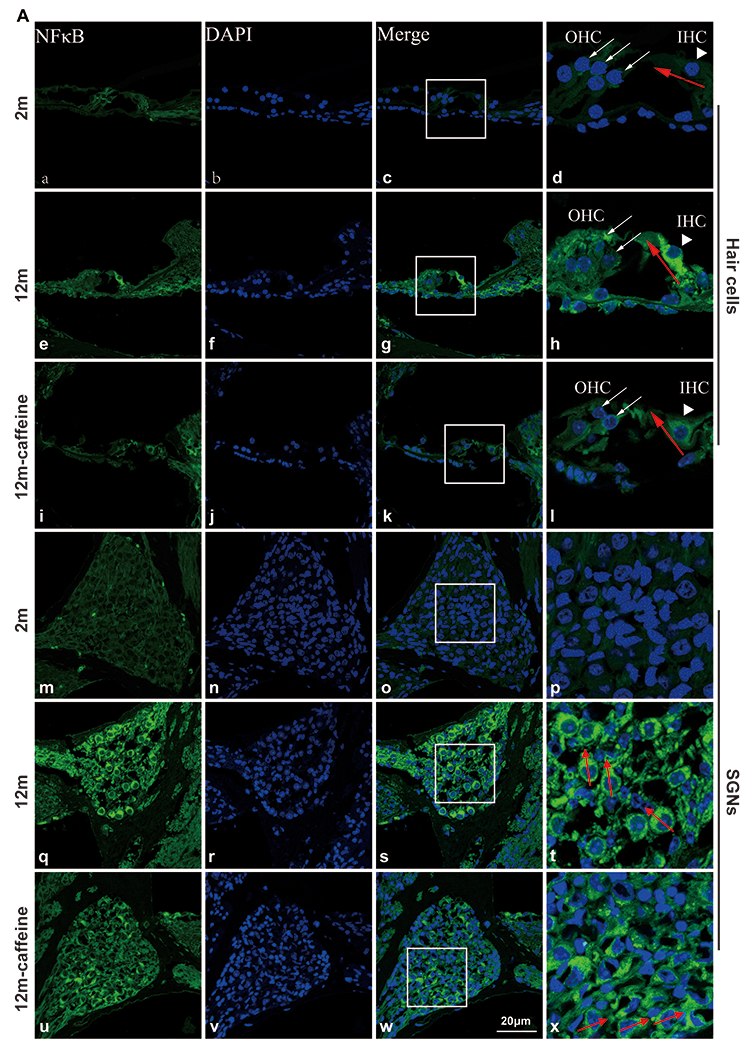

Additionally, we used immunofluorescence staining to detect the protein level of NF-κB in the cochlea of all three groups. We found that NF-κB was expressed in hair cells (HCs and SGNs) and its expression level was significantly lower in the 2-month group than in both 12-month groups, regardless of caffeine treatment (Fig. 5). However, compared to the 12-month control group, the protein level of NF-κB decreased in the 12-month caffeine-treated group (HCs: F=21.38, P=0.004; SGNs: F=58.22, P=0.0001) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Protein expression of NF-κB in the cochlea analyzed by immunofluorescence.

(A(a-l)) Immunostaining for NF-κB in the HCs of the cochleae of the three groups. (A(m-x)) Immunostaining for NF-κB in the SGNs of the cochleae of the three groups. (B, C, D) Line scans of NF-κB immunofluorescence intensity within the IHCs and SGNs in 2 m, 12 m, and 12 m caffeine mice. (E) Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity of NF-κB in IHCs and SGNs. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. n= 4, *: p <0.05, **: p <0.01. Scale bar=20 μm.

Discussion

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is a complex degenerative disease for which there is currently no ideal method of treatment or prevention. However, caffeine, one of the most widely used drugs worldwide and a major component of common drinks, has been shown in numerous studies to have potential protective effects against age-related chronic diseases, such as those studied by Grosso et al. (2017), Kaster et al. (2015), Londzin et al. (2021), and Stazi et al. (2021)(22–25). In the present study, we observed that hearing thresholds of C57BL/6J mice progressively increased with age at all frequencies, displaying typical ARHL characteristics. However, compared to the control group, the caffeine-treated mice exhibited less hearing loss. Specifically, ABR thresholds at the 32 kHz frequency were decreased in the caffeine-treated group after 6 months of caffeine administration (when the mice were 9 months old), and ABR thresholds at the click, 8 kHz, and 32 kHz frequencies were all decreased after 9 months of caffeine administration (when the mice were 12 months old). These results suggest that caffeine can ameliorate hearing loss in ARHL, and the longer the intake time, the more pronounced the effect.However, In this study, we clarified that hearing loss is not reversible. Caffeine cannot rescue or prevent this condition; instead, it just delays the ARHL. For example, caffeine decreased the ABR threshold in mice at the age of 12 m for 32 kHz (74 dB vs. 84 dB). Although this effect would not clinically change the deafness grades in humans, caffeine might ameliorate the progression of deafness. As shown in the following figure, when the ABR threshold was 60 dB, the control group will occur at about 7 months of age, while the caffeine group will occur at 10 months of age in mice. For humans, the age difference could be a decade or more, and this age difference is important for the quality of human life.

Extensive research reports have shown that caffeine can impact metabolism by affecting genes involved in metabolism in the hippocampus and renal cell carcinoma. Moreover, caffeine has been found to improve glucose homeostasis in both people with diabetes and rats. In the present study, we investigated the effects of caffeine on food and water intake as well as body weight over two months, and we found that caffeine did not affect body weight or food intake. However, the water intake of the caffeine group was initially higher than that of the control group, but it gradually normalized over time. It is important to note that we calculated water and food intake by cage (n=3 cages) rather than by individual mice, which could have affected the accuracy of our results. The data on water intake appeared to differ at some time points, but the difference was not statistically significant. If we had calculated intake for each mouse separately, we may have observed a statistically significant effect on water intake. Therefore, we believe that caffeine may affect water intake in mice during the first few weeks of treatment. At 12 months of age, after 9 months of caffeine administration, we measured the levels of INS, IGF-1, and glucose in the serum of the 2-month, 12-month, and 12-month caffeine mice. We found no significant differences in these indicators among the three groups, suggesting that short-term caffeine treatment may have some effect on metabolism, but long-term use may lead to tolerance and have no effect. It is worth noting that our study used a normal diet and mice, and the effects of caffeine on metabolism may differ in metabolic abnormality mouse models such as those with diabetes or those on special diets such as high-fat diets. However, in our study, caffeine did not appear to affect metabolism in normal mice.

Postmortem pathological analysis has indicated that ARHL in humans can be classified into three types: sensory hearing loss (loss of sensory hair cells), neuronal hearing loss (loss of SGNs), and metabolic hearing loss (atrophy of the SVs). However, it is now well established that most cases of ARHL exhibit mixed pathological changes(26) . The primary pathology of ARHL includes hair cell loss, stria vascularis atrophy, spiral ganglion neuron loss, and central auditory changes(27). In most cases, hair cell loss in the cochlea mainly occurs at the outer hair cells (OHCs), and OHC loss often occurs prior to inner hair cell (IHC) loss(28–30).In this study, compared with young mice, ARHL mice showed significant reductions in OHCs and SGNs and abnormal morphology of SVs, showing typical pathological characteristics of ARHL. However, these lesions were significantly reduced in caffeine-treated mice, suggesting that caffeine may improve ARHL in mice.

Satoh et al found that inflammatory factors such as IL-1α, IL-2, TNF-α, and NF-κB can infiltrate into inner ear cells, such as endolymphatic sac cells(31, 32) . Steroids have been used to treat hearing loss in a variety of cochlear disorders, and they can inhibit cytokine secretion from spiral ligament fibrocytes(33–35). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, is often used to induce inflammatory reactions in vitro and in vivo, and the TLR4/NF-κB pathway is the classical inflammation pathway induced by LPS. Experiments in vivo have indicated that LPS worsens hearing loss induced by bilirubin, aminoglycosides, and cisplatin(36). Furthermore, the inflammatory proteins IL-6 and TLR4/NF-κB were found to be increased in the cochlea of noise-induced hearing loss mice(37). Interestingly, it was reported that TLR4 polymorphisms, such as Asp299Gly (D299G) and Thr399Ile (T399I) that encode single amino acid substitutions in the ectodomain of TLR4, could result in significantly blunted responsiveness to LPS (38, 39). People with D299G/T399I polymorphisms are highly vulnerable to bacterial infections (40)and acute dental abscesses(41). Yang Y.found that the Lys694Arg (K694R polymorphism reduced the activation of NF-κB and the production of downstream inflammatory factors IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6, leading to blunted responsiveness to LPS(6). TLR4 polymorphism also has relation to hearing loss, and van Well GT et al. found that TLR4+896A>G mutant alleles (rs4986790) increased the risk of hearing loss(42). Therefore, there is a certain relationship between inflammation especially the TLR4/NF-κB pathway and hearing loss. However, the effect of inflammation on ARHL has not been elucidated. It has been reported that IL-6, CRP, white blood cell count, and neutrophil count are increased in ARHL-related human blood(43). In our present study, we initially identified IL-1β, a highly active proinflammatory factor and a member of the IL-1 family, which is generated through the TLR4/NF-κB pathway. We observed that its expression was significantly higher in the cochlea of ARHL mice compared to young mice. Additionally, we observed an increase in the protein expression of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB, as well as mRNA expression of target genes including Nfkb1, IL-1β, Nfkbia, and Icam in ARHL cochleae. Furthermore, we found that NF-κB was expressed in both the hair cells and SGNs. These results suggested that the high expression of NF-κB protein may lead to damage to these two types of cells in ARHL. In a recent study, IL-1β and Nfkb1 mRNA levels were also found to be upregulated in aged cochleae, and bioinformatic analyses predicted that NF-κB interacts with the immune gene network, which is consistent with our study. Therefore, we speculated that the TLR4/NF-κB inflammatory pathway may mediate the occurrence of ARHL and that targeting this pathway may improve ARHL.

Several studies have found that caffeine has anti-inflammatory properties. For example, Zhao et al. reported that caffeine inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation by suppressing MAPK/NF-κB and A2aR signaling in LPS-induced THP-1 macrophages(44). Badshah et al. found that caffeine can abrogate LPS-induced oxidative stress and neuroinflammation by regulating Nrf2/TLR4 in adult mouse brains(45). Chen et al. identified that caffeine can prevent hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal mice through the NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB pathway(46). Given that inflammation is an important character of ARHL and caffeine has an antiinflammation function, we detected the inflammation factors in our study. The TLR4/NF-κB pathway is an important inflammation pathway and might be related to ARHL. In this study, we observed an increase in the protein expression of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB and in the mRNA expression of target genes including Nfkb1, IL-1β, Nfkbia, and Icam in ARHL cochleae.These mRNAs and proteins were downregulated in the cochlea of caffeine-treated mice. Further experiments, such as RNA-seq, are required to present a whole gene expression profile to determine whether other inflammation pathways or molecular mechanisms are involved in the ARHL and treatment with caffeine.In addition, further experiments using the knockout mouse model must be performed. Owing to the limited data, we just proposed that caffeine may exert otoprotective effects on ARHL by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB pathway.

In our study, caffeine was administered in drinking water to mice from the age of 3 months to 12 months, which ameliorated ARHL.Then whether the duration of caffeine supplementation mattered? What would happen if the caffeine was stopped after 3 months. Or if the mice were followed to 2 years? We can’t give a direct answer here, for it need more experiments. However, I will try to predict the effect of the duration of caffeine supplementation according to previous studies. First, we will discuss the effect of caffeine consumption on hearing loss. Low incidences of hearing loss and tinnitus have been reported in coffee consumers; one study followed up 343 men and 345 women who developed disabling hearing impairment for 10 years and found that coffee consumption was associated with a low risk of disabling hearing impairment in men(47, 48). Another study found that coffee consumption could facilitate recovery from diabetes-induced auditory neuropathy in mice (49). These reports suggested that long-term coffee consumption might have otoprotective effects.

Second, we will discuss the effect of caffeine consumption on other age-related diseases. Cao C. et al. reported that acute caffeine administration to young adult (3–4 months old) and aged AD transgenic mice (14 months old) rapidly reduced Aβ levels in the brain interstitial fluid and plasma. Meanwhile, long-term oral caffeine treatment to aged AD mice provided sustained reductions in plasma Aβ and decreased the soluble and deposited Aβ in the hippocampus and cortex(12). Chronic caffeine treatment reduced hippocampal neuron loss, rescued learning and memory deficit, and ameliorated impaired neurogenesis in the mouse model of AD, it also exerts concerted pleiotropic effects in the hippocampus at the epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolic levels(50, 51) . Third, we will discuss the effect of coffee consumption on human health. Ruggiero E. et al. analyzed the data of 20 487 men and women (35–94 years old at baseline) in the Moli-sani Study and found that moderate consumption (3–4 cups/d) of coffee was associated with lower risks of all-cause and, specifically, of CVD mortality (15, 52). Caffeine, the main active ingredient of coffee, might be involved in the effect of coffee. Considering that coffee is almost the most popular beverage in the world, we aim to find a healthy lifestyle for hearing. In our study, the dose caffeine for mice were equivalent to a human intake of approximately 4 cups per day, which is a safe and beneficial dose for adult humans. From these studies, we can see that caffeine could exert protective function in age-related diseases regardless of the recipient age or the consumption duration. In our study, caffeine was administered in drinking water to C57BL/6J mice from the age of 3 months to 12 months, and this intervention ameliorated ARHL. Although we did not perform the experiments using different durations of caffeine consumption, we hypothesize that a long-term administration of caffeine is needed to ameliorate ARHL. The ARHL will develop on its own once the caffeine is withdrawn. When we use an accelerated ARHL mouse model, such as C57BL/6J mice whose hearing loss becomes serious at 12 months of age, the hearing loss would not be ameliorated even if the caffeine treatment is continued.

In our study, due to the limited size and long time(at least 10 months) of the experiments, only the male mice were used. So we should be cautious in drawing conclusions and evaluate our results objectively. There is often sex bias in basic and preclinical research on age-related hearing loss. First, hearing loss in humans and animals exhibits sex difference. Mattos LC et al found the prevalence of hearing loss is less in female than in male (53). However, Homans NC, et al conducted a large prospective cohort study of older adults and found that the difference in hearing between sexes was considerably less than previously reported(54). Henry KR. examined inbred strains of mice that are widely used as models of late- (CBA/J and CBA/CaJ) and early- (C57BL/6J) onset age-related hearing loss. In the former two genotypes, the thresholds to high frequency stimuli of the auditory brainstem response (ABR) are higher in the male than in the female. In contrast, the male C57BL/6J had more sensitive thresholds than the female, with both measures showing massive loss of sensitivity with increasing age(55). Second, caffeine interacts with estrogen, thus producing sex difference. In a study with over 10 years of follow-up, 343 men and 345 women developed disabling hearing impairment, and coffee consumption was associated with a low risk of disabling hearing impairment in men but not in womenonsumption was associated with a low risk of disabling hearing impairment in men but not in women(48).Fernandez K found that lovastatin reduces cisplatin-induced hearing loss in mice and the lovastatin-mediated protection was significantly greater among female than male mice(56). However, rapamycin treatment delayed the age-related loss of outer hair cells, and no significant difference in any of the conditions was observed between the male and female mice (57). From the above reports, we can conclude that the sex difference of ARHL is on a case-by-case basis. Regardless of its existence, we cannot ignore the sex difference. In our study, we were only able to use male mice. Whether caffeine has positive effect on female mice was not explored. To fully evaluate the effects of caffeine on ARHL, we should add female mice in future experiments.Our study still has its own significance. First, ARHL happens regardless of gender. Second, we can preliminary estimate caffeine’s effect on ARHL from our study. Third, given that caffeine is the most frequently consumed psychoactive substance in the world, our results provided important evidence about its benefits to hearing. Finally, inflammation, especially the TLR4/NF-kB pathway, might play an important role in ARHL, and gender causes minimal difference to this role. We demonstrated that caffeine might have otoprotective effects on ARHL via mitigating the TLR4/NF-kB signaling pathway, and this effect has minimal relation to gender.

Caffeine is a widely consumed substance found in beverages such as coffee and green tea, and it has a stable chemical structure that is not easily degraded. It is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration, and approximately 87% of the world’s population consumes an average of 193 mg of caffeine per day, which is below the caffeine intake recommendations by Health Canada and the European Food Safety Authority (400 mg/day for adults)(58). A prospective cohort study has suggested that habitual coffee consumption is associated with a lower risk of total mortality and the three leading causes of death, and it has also suggested that a dose of 3-4 cups/day is effective(59, 60) . In our study, the dietary levels of caffeine for mice were equivalent to a human intake of approximately 4 cups per day, which is a safe and beneficial dose for adult humans. Therefore, consuming caffeine by drinking coffee or other caffeinated beverages could be a beneficial and convenient strategy for preventing ARHL. However, the optimal dose and treatment time of caffeine, as well as the mechanisms by which caffeine regulates the inflammation pathway, require further research.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Effects of caffeine on the metabolic process of mice. The body weight, food intake and water intake of the mice during the experiment were monitored from 3 months old to 5 months old. (D-F) Serum levels of INS (insulin), IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1) and glucose. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. A: n=15 (mice), B, C: n=3 (cages). D-F: n=8 (mice).

Supplemental Table 1. Primers used for Q-PCR.

Highlight:

Long-term caffeine supplementation ameliorates ARHL in C57BL/6J mice

The TLR4/NF-κB inflammatory pathway has a close relationship with ARHL

Caffeine downregulates the TLR4/NF-κB inflammatory pathway in ARHL mice

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81873697), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (ZR2023MH186, ZR2023MH372), the Clinical Medicine + X project of Binzhou Medical University(BY2021LCX25), the Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Shandong Province(YDZX2022008), the US National Institute of Health (R01DC015111).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests to report.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data that support the findings in this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

REFERENCES

- 1.Slade K, Plack CJ, Nuttall HE. The Effects of Age-Related Hearing Loss on the Brain and Cognitive Function. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43(10):810–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson N, Ding B, Zhu X, Frisina RD. Chronic Inflammation - Inflammaging - in the Ageing Cochlea: A Novel Target for Future Presbycusis Therapy. Agng research reviews. 2017;40:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic Inflammation (Inflammaging) and Its Potential Contribution to Age-Associated Diseases. Journals of Gerontology. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132(3):344–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathways. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Y, Hu Y, Zhou Y, Liang T, Tang H, Ju H, et al. Lys694Arg polymorphism leads to blunted responses to LPS by interfering TLR4 with recruitment of MyD88. Innate Immun. 2021;27(6):483–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dulloo AG, Claudette D, Dorothée R, Lucien G, Nouri M, Marc F, et al. Efficacy of a green tea extract rich in catechin polyphenols and caffeine in increasing 24-h energy expenditure and fat oxidation in humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999(6):1040–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verster JC, Koenig J. Caffeine intake and its sources: A review of national representative studies. Critical Reviews In Food Science and Nutrition. 2018;58(8):1250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Lan X, Roche I, Liu R, Geiger JD. Caffeine protects against MPTP-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction in mouse striatum. J Neurochem. 2008;107(4):1147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren X, Chen J-F. Caffeine and Parkinson’s Disease: Multiple Benefits and Emerging Mechanisms. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:602697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson SC, Woolf B, Gill D. Plasma Caffeine Levels and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease: Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients. 2022;14(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao C, Cirrito JR, Lin X, Wang L, Verges DK, Dickson A, et al. Caffeine suppresses amyloid-beta levels in plasma and brain of Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(3):681–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurent C, Eddarkaoui S, Derisbourg M, Leboucher A, Demeyer D, Carrier S, et al. Beneficial effects of caffeine in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease-like tau pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(9):2079–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turnbull D, Rodricks JV, Mariano GF, Chowdhury F. Caffeine and cardiovascular health. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;89:165–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruggiero E, Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Persichillo M, De Curtis A, Cerletti C, et al. Daily Coffee Drinking Is Associated with Lower Risks of Cardiovascular and Total Mortality in a General Italian Population: Results from the Moli-sani Study. J Nutr. 2021;151(2):395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2016;7(2):27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nawrot P, Jordan S, Eastwood J, Rotstein J, Hugenholtz A, Feeley M. Effects of caffeine on human health. Food Addit Contam. 2003;20(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, Li B, Apisa L, Yu H, Entenman S, Xu M, et al. ER stress inhibitor attenuates hearing loss and hair cell death in Cdh23erl/erl mutant mice. Cell Death & Disease. 2016;7(11):e2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao T, Liu X, Sun Z, Zhang J, Zhang X, Wang C, et al. RNA-seq analysis of potential lncRNAs for age-related hearing loss in a mouse model. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Takano J, Murayama N, Tominaga M, Abe T, Park I, et al. Subacute Ingestion of Caffeine and Oolong Tea Increases Fat Oxidation without Affecting Energy Expenditure and Sleep Architecture: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blinded Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients. 2020;12(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acheson KJ, Gremaud G, Meirim I, Montigon F, Krebs Y, Fay LB, et al. Metabolic effects of caffeine in humans: lipid oxidation or futile cycling? Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(1):40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stazi M, Lehmann S, Sakib MS, Pena-Centeno T, Buschgens L, Fischer A, et al. Long-term caffeine treatment of Alzheimer mouse models ameliorates behavioural deficits and neuron loss and promotes cellular and molecular markers of neurogenesis. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2022(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grosso G, Godos J, Galvano F, Giovannucci EL. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017;37:131–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Londzin P, Zamora M, Kkol B, Taborek A, Folwarczna J. Potential of Caffeine in Alzheimer’s Disease-A Review of Experimental Studies. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaster MP, Machado NJ, Silva HB, Nunes A, Cunha RA. Caffeine acts through neuronal adenosine A2A receptors to prevent mood and memory dysfunction triggered by chronic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(25):7833–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivas-Chacón LDM, Martínez-Rodríguez S, Madrid-García R, Yanes-Díaz J, Riestra-Ayora JI, Sanz-Fernández R, et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in the Senescence Pattern of Auditory Cells in Age-Related Hearing Loss. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tavanai E, Mohammadkhani G. Role of antioxidants in prevention of age-related hearing loss: a review of literature. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2017;274(4):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalian Ding, Haiyan Jiang, Guang-Di Chen, et al. N-acetyl-cysteine prevents age-related hearing loss and the progressive loss of inner hair cells in γ-glutamyl transferase 1 deficient mice. Aging. 2016;8(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinheiro BP, Adel Y, Knipper M, Marcus Müller, Lwenheim H Auditory Threshold Variability in the SAMP8 Mouse Model of Age-Related Hearing Loss: Functional Loss and Phenotypic Change Precede Outer Hair Cell Loss. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2021;13:708190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu P-Z, O’Malley JT, de Gruttola V, Liberman MC. Primary Neural Degeneration in Noise-Exposed Human Cochleas: Correlations with Outer Hair Cell Loss and Word-Discrimination Scores. J Neurosci. 2021;41(20):4439–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satoh H, Firestein GS, Billings PB, Harris JP, Keithley EM. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, an initiator, and etanercept, an inhibitor of cochlear inflammation. [erratum appears in Laryngoscope. 2003 Jun;4(2):291]. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris JP. Satoh H, Firestein GS, Billings PB, Harris JP, Keithley EM. Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression in the Endolymphatic Sac During Inner Ear Inflammation. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 04(2):139–147, June 2003. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X, Zhang Q, Yang C, Liu Y, Li L. GRβ Regulates Glucocorticoid Resistance in Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fransson AE, Marta K, Kristian P, Curt P, Pernilla VP, Laurell GrFE. Hydrogen Inhalation Protects against Ototoxicity Induced by Intravenous Cisplatin in the Guinea Pig. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2017;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia L, Liu J, Sun Y, Shi H, Yin S. Rosiglitazone Improves Glucocorticoid Resistance in a Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss by Promoting MAP Kinase Phosphatase-1 Expression. Mediators of Inflammation. 2019;2019:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.A GZ, A HZ, B IP, B JZA. The TLR-4/NF-κB signaling pathway activation in cochlear inflammation of rats with noise-induced hearing loss. Hearing Research. 2019;379:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verschuur C, Agyemang-Prempeh A, Newman TA. Inflammation is associated with a worsening of presbycusis: evidence from the MRC national study of hearing. International Audiology. 2014;53(7):469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davoodi H, Hashemi SR, Seow HF. 5-Fluorouracil Induce the Expression of TLR4 on HCT116 Colorectal Cancer Cell Line Expressing Different Variants of TLR4. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(2):453–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long H, O’Connor BP, Zemans RL, Zhou X, Yang IV, Schwartz DA. The Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphism Asp299Gly but not Thr399Ile influences TLR4 signaling and function. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buduneli N, Özçaka Ö, Nalbantsoy A. Salivary and plasma levels of Toll-like receptor 2 and Toll-like receptor 4 in chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2011;82(6):878–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miri-Moghaddam E, Farhad-Mollashahi N, Baghaee E, Bazi A, Garme Y. Role of Thr399Ile and Asp299Gly polymorphisms of toll-like receptor-4 gene in acute dental abscess. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(2):e196–e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Well GTJ, Sanders MS, Ouburg S, van Furth AM, Morré SA. Polymorphisms in Toll-like receptors 2, 4, and 9 are highly associated with hearing loss in survivors of bacterial meningitis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uraguchi K, Maeda Y, Takahara J, Omichi R, Fujimoto S, Kariya S, et al. Upregulation of a nuclear factor-kappa B-interacting immune gene network in mice cochleae with age-related hearing loss. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao W, Ma L, Cai C, Gong X. Caffeine Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Suppressing MAPK/NF-κB and A2aR Signaling in LPS-Induced THP-1 Macrophages. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2019;15(8):1571–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Badshah H, Ikram M, Ali W, Ahmad S, Hahm JR, Kim MO. Caffeine May Abrogate LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation by Regulating Nrf2/TLR4 in Adult Mouse Brains. Biomolecules. 2019;9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen S, Wu Q, Zhong D, Li C, Du L. Caffeine prevents hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal mice through NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB pathway. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghahraman MA, Farahani S, Tavanai E. A comprehensive review of the effects of caffeine on the auditory and vestibular systems. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25(10):2181–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Machado-Fragua MD, Struijk EA, Yévenes-Briones H, Caballero FF, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E. Coffee consumption and risk of hearing impairment in men and women. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(5):3429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong BN, Yi TH, Park R, Kim SY, Kang TH. Coffee improves auditory neuropathy in diabetic mice. Neurosci Lett. 2008;441(3):302–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paiva I, Cellai L, Meriaux C, Poncelet L, Nebie O, Saliou J-M, et al. Caffeine intake exerts dual genome-wide effects on hippocampal metabolism and learning-dependent transcription. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stazi M, Lehmann S, Sakib MS, Pena-Centeno T, Büschgens L, Fischer A, et al. Long-term caffeine treatment of Alzheimer mouse models ameliorates behavioural deficits and neuron loss and promotes cellular and molecular markers of neurogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;79(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Dam RM, Hu FB. Caffeine consumption and cardiovascular health. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(7):429–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mattos LC, Veras RP. The prevalence of hearing loss in an elderly population in Rio de Janeiro: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73(5):654–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Homans NC, Metselaar RM, Dingemanse JG, van der Schroeff MP, Brocaar MP, Wieringa MH, et al. Prevalence of age-related hearing loss, including sex differences, in older adults in a large cohort study. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(3):725–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henry KR. Males lose hearing earlier in mouse models of late-onset age-related hearing loss; females lose hearing earlier in mouse models of early-onset hearing loss. Hearing Research. 2004;190(1–2):141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez K, Spielbauer KK, Rusheen A, Wang L, Baker TG, Eyles S, et al. Lovastatin protects against cisplatin-induced hearing loss in mice. Hearing Research. 2020;389:107905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altschuler RA, Kanicki A, Martin C, Kohrman DC, Miller RA. Rapamycin but not acarbose decreases age-related loss of outer hair cells in the mouse Cochlea. Hearing Research. 2018;370:11–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartman TJ, Knight CA, Teplansky Mitchell, et al. Beverage caffeine intakes in the U.S. Food and Chemical Toxicology: An International Journal Published for the British Industrial Biological Research. 2014;63:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park SY, Freedman ND, Haiman CA, Le Marchand LC, Wilkens LR, Setiawan VW. Association of Coffee Consumption With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Nonwhite Populations. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saito E, Inoue M, Sawada N, Shimazu T, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, et al. Association of coffee intake with total and cause-specific mortality in a Japanese population: the Japan Public Health Center–based Prospective Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;101(5):1029–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Effects of caffeine on the metabolic process of mice. The body weight, food intake and water intake of the mice during the experiment were monitored from 3 months old to 5 months old. (D-F) Serum levels of INS (insulin), IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1) and glucose. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. A: n=15 (mice), B, C: n=3 (cages). D-F: n=8 (mice).

Supplemental Table 1. Primers used for Q-PCR.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings in this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.