Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic halted many in-person programs of research and required researchers to pivot to technology-enhanced approaches. To date, there are no examples or guidelines on how to use technology to implement health promotion programs rooted in the community-based participatory research (CBPR) model among low-income older Black adults. The aims of this paper are (a) to describe and report on the health-related outcomes of an in-person CBPR model-based health promotion intervention program for older Black adults in a low-income community, and (b) to describe the process of adapting this program to a technology-enhanced and Zoom-delivered format and provide preliminary evidence on the health-related outcomes and acceptability of this program. This paper highlights the potential benefits of a technology-enhanced and Zoom-delivered health promotion program among low-income older Black adults and provides recommendations to optimize such efforts to foster these benefits. These recommendations are aligned with the four domains of the CBPR model (i.e., contexts, partnership processes, intervention and research, and outcomes). We conclude that CBPR model-based, technology implemented health promotion interventions for low-income older Black adults are acceptable to such adults and should attend to the values, perspectives, and preferences of these individuals. The information in this manuscript is relevant to health promotion specialists at this seemingly ongoing though post-pandemic era because technology-enhanced interventions are scalable and cost-effective and those anchored in CBPR are well-positioned to promote health equity.

Keywords: African American, health promotion, community-based participatory research, mHealth, technology, implementation

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act of 1993 mandated the proportional representation of racial and ethnic minority groups in health research. It is alarming that over two decades later certain groups remain grossly underrepresented in such research1,2. For example, despite constituting over 14% of the United States population, Black Americans represent between 2% to 7% of those enrolled in clinical trials1,3. Given the many widening health disparities between White Americans and Black Americans, there is a clear need to use intervention approaches that are tailored to the circumstances of Black Americans. Use of such tailored approaches in Black communities is responsive to the fact that traditional “one-size-fits-all” health promotion approaches (i.e., approaches that do not intentionally align with the preferences and values of the priority community) are increasingly viewed as not viable4,5. This reality has resulted in the increased use of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) model to develop, implement, and evaluate interventions to promote health among Black Americans6.

CBPR model-based health promotion interventions and intervention research programs center the voices of the priority population in order to create action-based health promotion efforts7,8. This centering results in interventions and related research that are likely aligned with values and perspectives of the priority population. The CBPR model has four domains – (1) contexts, (2) partnership processes, (3) intervention and research, and (4) intermediate and long-term outcomes8–10. The model is often represented as a flow diagram with each domain directly influencing the following domain. Each domain in turn is composed of several factors. Contexts is composed of contextual factors such as the health issue of importance, capacity and readiness, and cultural factors. These contextual factors ground the partnership processes of the community-academic partnership. This partnership processes domain includes factors such as partnership structures (e.g., diversity of who is involved, partnership values), individual characteristics (e.g., cultural humility, personal values), relationships (e.g., respect, trust, participatory decision making), and level of commitment to collective empowerment. These partnership processes impact interventions and research. This domain (i.e., interventions and research) includes two main factors – processes (e.g., integration of community knowledge, empowering processes, community involvement in research) and outputs (e.g., culture-centered interventions, partnership synergy, appropriate research design). The final domain is outcomes. This includes both intermediate (e.g., capacity) and long-term outcomes (e.g., health equity). See Belone et al. for a detailed description and visual depiction of the CBPR model. 9

CBPR is a collaborative approach to health promotion that inherently involves all stakeholders (e.g., members of the priority population, researchers) in the research process. 7,8 Because of this involvement, health promotion interventions based in CBPR are often well-aligned with the needs and concerns of the priority population. This approach differs from the traditional approach to health promotion in the following assumptions: (1) approach (i.e., CBPR is collaborative, whereas the traditional approaches are often top-down); (2) focus (i.e., CBPR addresses priority population-identified concerns, whereas traditional approaches often address researcher-identified concerns); (3) outcomes (i.e., CBPR is designed to be sustainable, whereas the traditional approach often is implemented one-time); and (4) mechanisms (i.e., CBPR leverages the strengths of the priority population, whereas the traditional approach often applies approaches derived from other groups). By employing the CBPR approach, medical and health promotion professionals can gain unique insights into the health-related needs of the priority population and develop/implement health promotion programming that is culturally relevant and sustainable. Because this approach is ongoing and iterative, and centers the voice of the priority population, it can be adapted (e.g., modifications to the protocol and/or cessation of the program) to rapidly changing contextual circumstances (e.g., natural events that constrain resources).

The CBPR model has been praised for its potential to promote health equity and eliminate health disparities that have a disproportionately negative impact on marginalized communities11–13, such as Black American communities14. This praise has provided the impetus for prioritizing patient (or participant) engagement by federal organizations such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute15, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality16, and the NIH17. Additionally, the NIH has increased its funding for programs of research using CBPR18. A comprehensive review of interventions developed and implemented using a CBPR model to promote health among Black Americans has shown that this model can facilitate positive health outcomes19.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic posed challenges for those engaging in CBPR given that this type of research typically involves in-person research activities that help build rapport with the priority community20—activities that were prevented by the social distancing measures that were mandated in response to COVID-19. Many of the federal funding organizations mandated that researchers halt any in-person research activities, which in turn negatively impacted research using the CBPR model. While health disparity researchers conducting CBPR struggled to adapt their health promotion research to the restrictions that came with the COVID-19 pandemic, existing health disparities in the United States were amplified21. Thus, heath disparity researchers and other researchers had to quickly adapt and implement existing programs of research using novel methods that could be implemented at a distance, though little guidance existed20,22. This is particularly true for investigators implementing CBPR-based programs of research among Black American communities.

This paper fills an important gap in the health promotion literature by providing an example of a technology-enhanced and Zoom-implemented, CBPR model-based and evidence-supported health promotion intervention program for older Black Americans living in low-income communities – a population disproportionately impacted by high rates of adverse health, 23,24 low health-related quality of life,25 and loneliness26,27. Such intervention programs will be practical long after the COVID-19 pandemic given the increasing access to high speed internet throughout the United States, including in rural communities28, and given that technology-delivered interventions are cost-effective and scalable29–31. The specific aims of this manuscript are to:

Describe and report on the health-related outcomes of an in-person CBPR model-based health promotion intervention program for older Black adults in a low-income community; and

Describe the process of adapting this program to a Zoom technology-enhanced format and provide preliminary evidence on the acceptability of this program when it was implemented with a different group of older Black adults in a low-income community who chose to participate in the program either via Zoom or in-person.

In-Person Holistic Health Intervention Program for Older Black Adults in Low-Income Communities

1.1. Partnership Structure

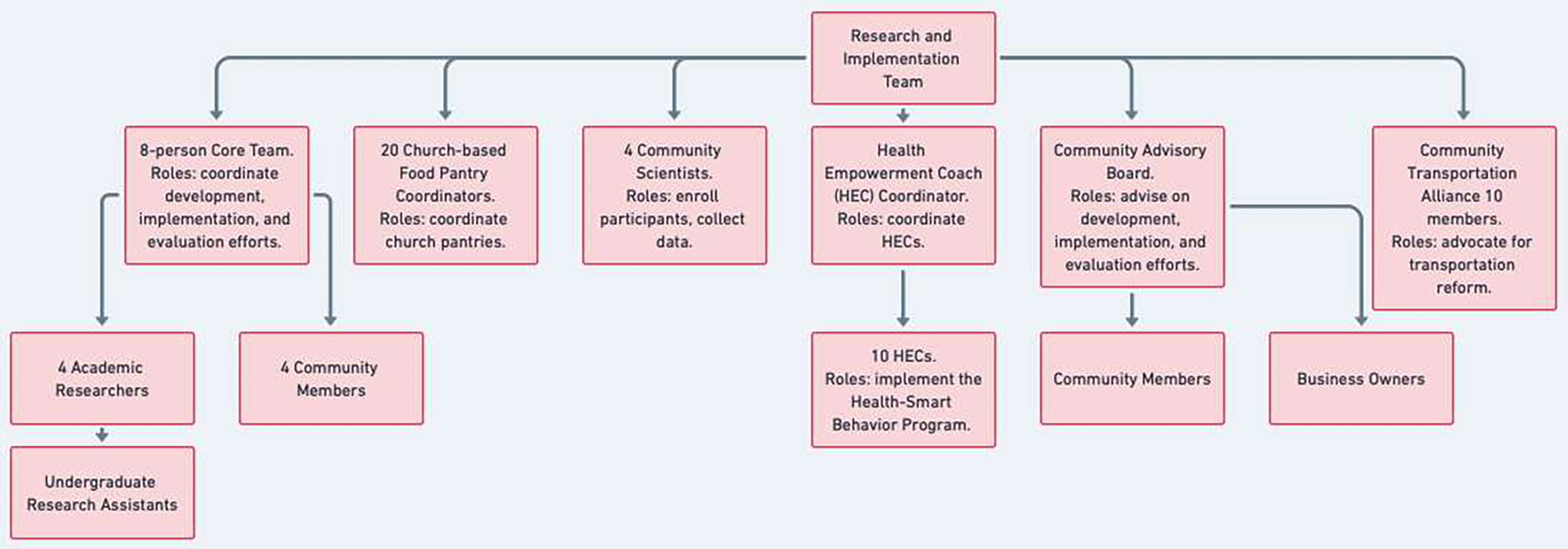

The partnership structure of this program consisted of various academic and community-based stakeholders. There was an 18-person core team, which was composed of by an equal number of academic researchers and community members. In addition to this core team, the partnership team consisted of 20 church-based food pantry coordinators, 4 community scientists, 10 health empowerment coaches (HECs), and undergraduate research assistants. All these individuals (including the core team) formed the research and implementation team and were required to participate in a cultural sensitivity training. Finally, a community advisory board that included community members and business owners was established. Following the need for transportation assistance to healthy food options and health care services as identified in the needs assessment described below, a 10-member Community Transportation Alliance was also later formed. The roles and responsibilities of each partner are discussed in the next section. See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the research and implementation team with position descriptions. This partnership structure also applies to the technology-implemented adaptation of this program that is later described.

Figure 1.

Research and implementation team with position descriptions.

1.2. Design of the In-Person CBPR Model-Based Health Promotion Intervention Program for Older Adults in Low-Income Black American Communities

This program is called the Health-Smart Holistic Health (HSHH) Centers Program and it was a multi-year, multi-level, and multi-component health promotion program based in the CBPR model and Health Self-Empowerment Theory (HSET)32. The program received external funding and was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at the University of Florida. Consent to participate was obtained from all of the participating Black older adults. The intention of this program was to improve health outcomes among 193 (Year 1), 190 (Year 2), and 255 (Year 3) older Black Americans living in the communities that constitute the lowest income, mostly Black, and most underserved health zone (i.e., Health Zone 1) in a large city in the southern part of the United States. Health Zone 1 also has a low mean level of education, high rate of diabetes mortality, and a high rate of emergency room visits33.

The primary goals of the HSHH Centers Program were to promote: (1) healthy behaviors, (2) food security, (3) social connection, and (4) family member employment with a living wage. The secondary program goals were to improve quality of life, increase the number of healthy days, and decrease blood pressure, cholesterol, body mass index, and depression among the program participants. This program was developed through the collaborative efforts of the partnership team, and it was informed by a needs assessment and research evidencing (1) the interrelationship among physical, psychological, and spiritual well-being, (2) the association of these variables with food security and social connection, and (3) the need for transportation to healthy food options and health care services. As previously indicated the HSHH Centers Program was a multi-year program – beginning in 2019 and concluding in 2022. Thus, the original design and implementation of the program had to be adapted to the social distancing requirements necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.3. Implementation of the In-Person CBPR-Model Based Health Promotion Intervention Program for Older Adults in Low-Income Black American Communities

Eight community scientists were hired and trained to enroll participants into the study and to administer the questionnaires used to help evaluate the impact of the program. In addition to these eight community scientists, the program leveraged a train-the-trainer framework34 in which 20 individuals called HECs were hired and trained to implement the healthy behaviors-focused intervention program (i.e., Health-Smart6,35). Applicants to the community scientist and HEC positions were interviewed by a project manager, who assessed personal values and strengths, cultural competency and sensitivity, and professional development. In addition to residing in the priority community, all community scientists and HECs were older Black adults. Each of the community scientists and HECs completed an IRB-required researcher training program. The training lasted 24 hours and was conducted by the primary investigator (PI) and the PI’s research team. The additional program implementation training received by the HECs was based on the Health-Smart Training Manual – a comprehensive, culturally-sensitive implementation manual that has been used in a number of CBPR health promotion interventions6,35. In addition to being trained, HECs received weekly Zoom-based supervision and technical assistance regarding intervention implementation concerns.

Health-Smart, which was implemented by the HECs at the churches participating in the HSHH Centers Program, consisted of four components: (1) an individual session with a HEC for setting achievable healthy eating and physical activity goals and for instruction on and practice using an online social connection application and using a cellphone for texting and other social connection activities, (2) a HEC-facilitated Health-Smart group discussion sessions, (3) group physical activities, and (4) a Health-Smart expert panel to which participants can ask anonymous and open health-related questions. Following the individual goal setting session, the HECs facilitated nine, consecutive, weekly 2-hour Health-Smart group discussions sessions involving up to 10 participating older adults. The Health-Smart group discussion sessions consisted of (1) short presentations from the Health-Smart Behavior Resource Guide for Adults (i.e., a culturally-sensitive resource guide that includes health promoting information to enable healthy eating and physical activity even with a disability, and strategies for managing stress, anger, and depression), (2) discussions by the participating older adults on strategies for applying the information in the aforementioned short presentations to their own lives, and strategies for increasing social connection, and (3) HECs encouraging and facilitating participants’ engagement in 150 minutes a week of moderate-to-intense physical activity with other participants in the group. Participants were also given the opportunity to ask their health- or disease-related questions to a Health-Smart Expert Panel (consisting of a physician, dietician, physical fitness expert, psychologist/counselor, pharmacist, and a community member who had adopted a health promoting lifestyle).

In addition to the Health-Smart Behavior Program, participants were also given the opportunity to obtain free, healthy food from the food pantries based at the earlier mentioned participating churches and to receive assistance with full-time employment of a family member in their household. The food pantries were church-based and were established for the program. Furthermore, employment assistance for family members of participants was provided by a subcontract to a local urban league that specialized in helping jobless individuals train for and find employment. The rationale for focusing on employing family members is that having family members work will have a positive impact on access to healthy food and transportation by the older adults—a group among whom most members were retired. Older adults who wanted part-time jobs were assisted with finding such jobs, though asking for such assistance was rare.

1.4. Outcomes of the In-Person CBPR-Model Based Health Promotion Intervention for Older Black Adults in Low-Income Black American Communities

Outcome data of the HSHH Centers Program consisted of body mass index (BMI), physical health-related quality of life, psychological health-related quality of life, loneliness, and food insecurity. Data were collected at baseline, immediately post-intervention, and 3-months post-intervention. Results indicated that BMI, physical health-related quality of life, psychological health-related quality of life, and loneliness significantly improved from baseline to immediately post-intervention and that improvements were maintained at 3-months post-intervention. Additionally, it was found that food insecurity did not significantly change from baseline to immediately post-intervention, though there was a significant improvement between baseline and 3-months post-intervention, suggesting a delayed effect of the program on food insecurity. A full description of the results and analytical approach are published elsewhere.36

Adaptation of the HSHH Centers Program to a Technology-Implemented Version

2. Adaptation of the Technology-Enhanced HSHH Centers Program by Each Domain of the CBPR Model

2.1. Domain #1 of CBPR: Contexts

The onset of the pandemic caused the program to be paused for 6 months. During this pause, the entire partnership team conducted a thorough assessment of the unique context created by the pandemic for older Black adults. The team immediately began following and noting relevant emerging research. This research was quick to recognize that older individuals and those with pre-existing health conditions were at an increased risk for adverse health outcomes (e.g., death) 37,38. The risks were compounded for older Black adults26, given that race is as a proxy for other racism-related factors such as insurance status, income, and number of chronic health conditions – factors also associated with an increased risk of adverse pandemic-related health outcomes. Additionally, due to guidance from public health organizations, many individuals and workplaces shifted to teleconferencing. The assessment of relevant research conducted by the research team found this shift problematic given that older Black adults are more likely to be at-risk for adverse health outcomes and to endorse low technology-related health literacy39,40.

In light of this emerging research, the research team consulted with the community scientists and HECs. These consultations focused on: (1) whether the community had the capacity and/or continued need for this program to proceed during the pandemic and (2) how to best proceed with the program if it were desired given the pandemic-related guidelines.

Following the assessment of relevant emerging research and the consultation meetings, decisions to further tailor the intervention to the unique context of older Black adults during the COVID-19 pandemic were made. It was collectively decided that (a) a Zoom-delivered version of Health-Smart would be developed and implemented to include virtual group discussions, panels, and physical activity sessions; (b) the church-based food pantries would operate a no-contact pick-up service, where individuals would drive to the pantry, open the trunk of their car, and a volunteer would place the food in the trunk; and (c) the employment assistance sessions would occur virtually and/or by phone. It was also collectively decided that the in-person version of Health-Smart would also be an option since about 35% of the program participants wanted the option of participating in this version but with social distancing and provided masks. The groups of participants had to be reduced in size (i.e., reduced from 15 members per group to 10 members per group) in order to accommodate social distancing at the program sites.

Following the decision to develop and implement a technology-implemented version of the HSHH Centers Program, the HECs worked with the researchers to develop the Zoom-delivered version of Health-Smart and the other components of the HSHH Centers Program. Materials were adapted for virtual implementation that integrated flexibility and cultural sensitivity given the new context. Simultaneously, strategies were then developed to overcome another challenge brought on by the context of the pandemic – the lower likelihood that low-income older Black adults would have access to a videoconferencing-enabled device. Each participant was contacted by their HEC to ensure that the participant had access to such a device. If the participants did not have access to such a device, arrangements were made to safely access a computer at their church or with the help of a close family member.

The physical activity component of Health-Smart required that the research team develop a physical activity-focused website. This website was linked to Zoom-based fitness programs (e.g., Zumba and yoga for seniors) that fostered social connection. It also included a platform that could be used by the participants to interact with one another and participate in fitness-based games. In the spirit of “meeting participants where they are at”, HECs ensured that the participants knew how to use and navigate the physical activity-focused website program. Additionally, undergraduate students led low-impact physical activities via Zoom three times a week for all program participants.

2.2. Domain #2 of CBPR: Partnership Processes

In addition to involving the HECs in all aspects of the development and re-development process, intentional efforts were made to ensure that the community partners felt “heard” throughout the technology-enhanced implementation. There was infrastructure in place to make sure that all those participating in the HSHH Centers Program were heard and that the community member program leaders and the academic researchers had power equity and made joint decisions that reflected this equity. This infrastructure for equitable decision-making and a respectful academic-community partnership involved: (a) hiring community member staff for the leadership roles (i.e., community scientists and HECs) in the HSHH Centers Program; (b) weekly meetings of the academic researchers and the community staff leaders to plan the HSHH Centers Program and address any program related questions and/or concerns; (c) bi-weekly meetings of the HEC Coordinator with the HECs – meetings that the PI and the PI’s research staff attended to help address problems or concerns; (d) monthly meetings with the pantry staff and pastors at each church to address the operational needs of the pantries; (e) program agendas that included reports from all the HSHH Centers Program Staff; and (f) cultural sensitivity training provided by the PI to all the HSHH Centers Program Staff. Along with this infrastructure, there was evidence that the community leadership was viewed as legitimately representing the community because (1) these individuals were from the community, (2) many participated in previous iterations of the HSHH Centers Program, (3) the community utilized these individuals as a liaison to the academic HSHH team, and (4) community concerns were conveyed through these individuals.

2.3. Domain #3 of CBPR: Intervention & Research

In addition to tailoring the HSHH Centers Program to the unique context of older Black adults, the technology-enhanced program also integrated cultural knowledge that aligned with the values, preferences, and perspectives of the participants. Attention was given to integrating surface-level and deep-level structures during the technology-enhanced implementation. Evidence of surface-level structures included involving members of the priority community in creating recruitment materials and during the implementation of the program, whereas evidence of deep-level structures included the intentional alignment of the intervention with cultural values41. Integration of these two structures occurred by developing and implementing the technology-enhanced intervention by HECs who identified as Black and from the community. Doing this facilitates the alignment of the program with cultural knowledge. It does not ensure alignment. Alignment of the HSHH Centers Program with the cultural knowledge of Black individuals occurred during the implementation of the Health-Smart portion of the program. The Health-Smart Program is a group-based program with ample opportunities for participants to brainstorm culturally relevant and context-salient strategies to overcome barriers to health-promoting behaviors. Specifically, this alignment was ensured by the Health-Smart Behavior Resource Guide, which was a previously developed resource that was to be used in conjunction with the Health-Smart discussion groups. This resource integrates cultural knowledge (e.g., the importance of prayer and spirituality) that matches community values, norms and practices and has been used in previous interventions6,35, though was tailored for the present intervention for older Black adults by consulting with the community scientists and HECs. Examples of such tailoring included intentional discussions of barriers to health promotion experienced by older Black adults in Health Zone 1 and strategies to overcome these barriers, framing discussions that were congruent with cultural norms, and instruction on using the technology.

Tailoring the intervention to the unique values, preferences, and perspectives of the participants is necessary, though not sufficient. Interventions based in CBPR must also empower participants. The Health-Smart program is anchored in HSET32 – a novel empowerment-based health promotion theory that highlights the impact of cognitive-behavioral variables on health promotion for individuals with limited autonomy. Participants in the HSHH Centers Program were taught how to take charge of their health despite their current circumstances using this cognitive-behavioral approach that focuses on individual and community empowerment. Individual empowerment occurred through the program’s focus on increasing health motivation, health self-praise, adaptive coping, health responsibility and knowledge, and health self-efficacy - cognitive-behavioral variables that can be tailored to the experiences of the individual and which are sustainable, modifiable, and low-cost to implement.

Additionally, community empowerment occurred by teaching members of the community (i.e., HECs) how to implement the program and tasking the Community Transportation Alliance with advocating for policy changes. This advocacy was facilitated by data from a transportation satisfaction/dissatisfaction survey that the members of the transportation alliance and the researchers administered to 150 older adult residents in Health Zone 1.

It is expected that the community will continue to implement iterations of Health-Smart after the formal program has been completed, as has been observed by the research team in other similar programs 6,35. This likelihood of continued implementation of the HSHH Centers Program is supported by the emphasis on equitable decision-making that enables the community to have a thorough understanding of the program and become “owners” of the program. This is also supported by engaging each church in setting a Health-Smart sustainability plan that involved identifying parts of Health-Smart that that would occur at least monthly at their church.

2.4. Domain #4 of CBPR: Outcomes

The outcomes of the HSHH Centers Program were established based on a needs assessment conducted among the participating community, in addition to meetings with local pastors and church leaders. The outcomes were assessed using self-report questionnaires that were completed at home. Biometric data (weight, height, and blood pressure) were collected at one health clinic rather than at the participating community health centers where these measures were initially being taken and that were closed because of the pandemic. Regarding this last change, participants could choose to collect biometric data at home if they had the appropriate equipment to do so.

Results of the HSHH Centers Program were made available to the community in a variety of formats. Specifically, three videos were made on the impact of the program that were distributed to the community. Outcomes were published in an annual report that was disseminated to the community. In addition to these health-related outcomes, it is expected that there will be systemic and capacity-related changes among the community as a result of the program. For example, the work of the Community Transportation Alliance resulted in policy changes which increased accessible bus transportation for individuals in this Health Zone and resulted in $2 car transportation to the only grocery store and pharmacy in Health Zone 1. These changes are likely to enable the continued implementation of the program after the formal program concludes. Given the positive results of the program, it is expected that continued health benefits to the community will be observed..

2.5. Evidence of the acceptability and Impact of the Technology-Implemented HSHH Centers Program

An exploratory study was conducted to evaluate the impact of the technology-enhanced HSHH Centers Program. Participants in this portion of the study chose to participate in the in-person HSHH Centers Program (using masks and social distancing) or the technology-enhanced HSHH Centers Program. It was found that the participants in these two 2.5-month programs had similar increases in healthy eating and physical quality of life and similar decreases in perceived stress, depression, and unhealthy days. Those in the in-person and the technology-enhanced HSHH Centers Program highly endorsed the program as indicated via structured interviews. Approximately 50% of the participants in the in-person HSHH Centers Program said that they would have chosen the virtual HSHH Centers Program if they had the Internet access needed to participate in the program via Zoom. Most of the participants who participated in the technology-enhanced HSHH Centers Program said that they would have appreciated more training in using Zoom early in the program, including, for example, more training in how to use the chat feature on Zoom.

Discussion

Many health promotion efforts are limited in their ability to produce meaningful changes in health-related outcomes among older Black adults. This is because many of these efforts are “one-size-fits-all” and are not tailored to the unique values, perspectives, and preferences of these individuals. The CBPR model has been praised for its ability to promote meaningful changes in health-related outcomes among residents of traditionally underserved communities, such as Black adults. This is because health promotion programs based in the CBPR model involve the priority community in the development, implementation, and evaluation of the program. The COVID-19 pandemic halted many health promotion efforts due to social distancing and stay-at-home public health mandates. While many health promotion efforts transitioned to technology-based implementation, there was little guidance on how to transition a health promotion program for older Black adults that was based on the CBPR model. This paper is responsive to calls that highlight the lack of guidance available for technology-implemented CBPR model-based health promotion interventions20,22.

Consistent with Aim 1 set forth in this paper, we described and reported positive health outcomes of an in-person HSHH Centers Program for older Black adults living in low-income communities. This information derived from this program suggests that this program is feasible and holds much potential for promoting health and health equity in such communities. Consistent with Aim 2 we described the process of adapting this program to a technology-enhanced Zoom-delivered format and provided preliminary evidence on the health-related outcomes and acceptability of this program when it was implemented with a different group of older Black adults in a low-income community who had the option to participate in the program either via Zoom or in person. Specifically, the preliminary findings from the described exploratory study that compared the outcomes of the technology-enhanced Zoom-implemented version of this program with the in-person version of this program (that incorporated social distancing and mask wearing) produced comparable positive health outcomes. Together, all of the reported findings suggest that CBPR model-based, technology-implemented health promotion programs for older Black adults in low-income communities are feasible and acceptable to these adults and can foster beneficial health outcomes.

The aforementioned findings suggesting that the CBPR-based, technology implemented health promotion program for older Black adults in low-income communities described in this paper is feasible and acceptable elucidate some notable benefits of this program. One such benefit is that this program is potentially scalable; that is, it can likely be expanded from an effort that focuses on a small proportion of the population to one that focuses on a large proportion of the population, while retaining effectiveness42. The ability to focus on a larger proportion of the population, while being cost-effective29, well-positions the described technology-enhanced health promotion program and other such programs to play an important role in advancing health equity among older Black adults43 – a group that experiences health disparities.

A second important benefit of the aforementioned technology-implemented program is that it is usable by older adults who do not have transportation to in-person health promotion programs or who have physical health challenges that make it impossible for them to attend such programs. Additionally, this program included training health empowerment coaches (HECs) and community scientists as well HEC trainers, all of whom are prepared to sustain the program and to partner with future health promotion researchers committed to reducing health disparities and promoting health equity in Black communities. A third important benefit of the aforementioned technology-implemented health promotion program is that it meets the need identified by primary care physicians for community-based health promotion programs to which they can refer their patients who need such programs.44 It is also the case that specialty physicians such as oncologists and cardiologists can also refer patients to such programs. Recommendations to foster and maximize these benefits in similar efforts are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations.

| CBPR Domain | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Contexts | Conduct a rapid review of existing research with attention given to individual (e.g., technological literacy, chronic health conditions), societal (e.g., impacts of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and hesitancy to participate), and policy-related (e.g., data privacy and security, availability of health resources in the community) contextual factors that may impact the intervention and the technology-enhanced implementation of the intervention. |

| Consult with community partners on their capacity to proceed with a technology-enhanced intervention (e.g., assess if they or their churches have the infrastructure to implement technology-based interventions). Discuss potential barriers (e.g., technological literacy of leadership) and strategies to overcome these barriers. (e.g., providing technical assistance) | |

| Tailor the technology-enhanced intervention to the context of the priority population (e.g., using appropriate and relevant language, larger text size, offering text to audio options and voie commands). | |

| Partnership Processes | Ensure technology-based infrasvuciure is in place for equitable decision-making on all program-related decisions (e.g., ensure all stakeholders are represented in decision-making, ensure stakeholders have access and ability to use technology). Pay them for their time and give them titles such as “community scientists.” |

| Schedule regular and frequent meetings with community partners and be mindful of who is in attendance. It is easy for a community partner to be overlooked during a technology-enhanced intervention, especially if they are unfamiliar with the platform. | |

| Check in with community partners who are regularly absent and/or are muted during teleconferencing meetings. Implement anonymous feedback mechanisms for individuals who might hesitate to speak up. | |

| Intervention & Research | Tailoring the technology-enhanced program to the unique values, preferences, and perspectives of the target population is necessary, but not sufficient. The program should also empower the participants. Ensure that tools provided by the program are consistent with the lives of older Black adults prior to the introduction of the program, so that the tools can be used after the termination of the program. Assist community members with passing IRB trainings so that they can collect research data. |

| Involving the community members in the implementation of the research program facilitates alignment with the unique values, preferences, and perspectives of the target population, though additional efforts should be taken to ensure this alignment. Regular feedback should be gathered from the older Black adult participants to ensure alignment if contexts change. | |

| Collecting data to justify policy changes that enable engagement in healthy lifestyles, including transportation access policies. Older Black adults may experience systemic barriers to health promotion (e.g., residing in food deserts). Form a community-led, policy change committee. | |

| Outcomes | Plans should be made for data to be collected using a variety of strategies (e.g., at-home options for those with limited mobility/transportation, text to audio). |

| The program’s outcomes should be made readily available to the target community (e.g., outcomes should be available in a manner that is easily accessible to older Black adults). A variety of dissemination efforts should be used, including holding a Town Hall Meeting and disseminating a community-friendly program report. |

The implementation of a feasible and effective technology-enhanced CBPR intervention program for older Black adults has implications for other health disparity groups, such as rural older Black adults—a group that experiences lower health than other rural residents45,46. Although there is a continued need to reduce the digital divide between urban and rural residents, this divide is shrinking. Only 20% of rural residents have concerns about their ability to acquire high-speed internet47 and roughly 70% of rural adults with the internet report using the internet for health-related purposes47. The need for these interventions is underscored by qualitative focus groups with rural residents which indicate that these individuals are interested in technology-enhanced health promotion interventions48. There is also research showing that technology-based health promotion efforts among older rural residents improve health outcomes and are regarded as acceptable/feasible by participants49. Given that technology-enhanced health promotion interventions can be participated in from one’s home, these interventions are uniquely situated to promote health among groups of rural and older Black adults as well as others in low-income communities who might be difficult to reach through traditional in-person healthcare efforts.

Declaration of Interest:

None. Dr. Carolyn M. Tucker and the HSHH project were funded by the Humana Foundation (AWD05408; AWD07906; AWD09725). Dr. Guillermo M. Wippold is funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23MD016123. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Humana Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Guillermo M. Wippold, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Carolyn M. Tucker, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Aashna Farishta, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Erin Kim, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Rhonda Hill, UF College of Community Health and Family Medicine (Jacksonville), Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Alexanderia Burwell, University of Florida – Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Paul Sapia, Humana Inc., Jacksonville, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Chen MS, Lara PN, Dang JHT, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty Years Post- NIH Revitalization Act: Enhancing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials ( EMPaCT): Laying the Groundwork for Improving Minority Clinical Trial Accrual. Cancer. 2014;120:1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vickers SM, Fouad MN. An overview of EMPaCT and fundamental issues affecting minority participation in cancer clinical trials: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual. In:2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Awidi M, Al Hadidi S. Participation of Black Americans in Cancer Clinical Trials: Current Challenges and Proposed Solutions. Jco Oncology Practice. 2021;17(5):265-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minivielle E Toward Customized Care. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2018;7:272–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wippold GM, Frary SG, Abshire DA, Wilson DK. Improving Recruitment, Retention, and Cultural Saliency of Health Promotion Efforts Targeting African American Men: A Scoping Review. Ann Behav Med. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker CM, Wippold GM, Williams JL, Arthur TM, Desmond FF, Robinson KC. A CBPR Study to Test the Impact of a Church-Based Health Empowerment Program on Health Behaviors and Health Outcomes of Black Adult Churchgoers. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(1):70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel BA. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. In: 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass,; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belone L, Lucero JE, Duran B, et al. Community-Based Participatory Research Conceptual Model: Community Partner Consultation and Face Validity. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(1):117–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez V, Sanchez-Youngman S, Dickson E, et al. CBPR Implementation Framework for Community-Academic Partnerships. Am J Community Psychol. 2021;67(3–4):284–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De las Nueces D, Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, Hicks LS. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1363–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health : from process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004(99):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elgazzar R, Nolan TS, Joseph JJ, Aboagye-Mensah EB, Azap RA, Gray DM. Community-engaged and community-based participatory research to promote American Heart Association Life’s Simple 7 among African American adults: A systematic review. Plos One. 2020;15(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient Engagement In Research: Early Findings From The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitlock EP, Lopez SA, Chang S, Helfand M, Eder M, Floyd N. AHRQ series paper 3: identifying, selecting, and refining topics for comparative effectiveness systematic reviews: AHRQ and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatfield PM, Sorkness CA, Esmond SL, Adams AK. Achievements in Health Equity: Nesting an NIMHD Center of Excellence within a CTSA. Cts-Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(1):5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elwood WN, Corrigan JG, Morris KA. NIH-Funded CBPR: Self-Reported Community Partner and Investigator Perspectives. J Community Health. 2019;44(4):740–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coughlin SS, Smith SA. Community-Based Participatory Research to Promote Healthy Diet and Nutrition and Prevent and Control Obesity Among African-Americans: a Literature Review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2017;4(2):259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valdez ES, Gubrium A. Shifting to Virtual CBPR Protocols in the Time of Corona Virus/COVID-19. Int J Qual Meth. 2020;19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krouse HJ. COVID-19 and the Widening Gap in Health Inequity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tami-Maury I, Brown L, Lapham H, Chang S. Community-based participatory research through virtual communities. J Commun Healthc. 2017;10(3):188–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Annals of Epidemiology. 2020;47:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips N, Park IW, Robinson JR, Jones HP. The Perfect Storm: COVID-19 Health Disparities in US Blacks. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2021;8(5):1153–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes-Larson E, Mobley TM, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life in Persons With and Without Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatters LM, Taylor HO, Taylor RJ. Older Black Americans During COVID-19: Race and Age Double Jeopardy. Health Education & Behavior. 2020;47(6):855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wippold GM, Tucker CM, Roncoroni J, Henry MA. Impact of Stress and Loneliness on Health-Related Quality of Life Among Low Income Senior African Americans. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2020;34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center PR. Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet. 2021; https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/?menuItem=6b886b10-55ec-44bc-b5a4-740f5366a404. Accessed April 14, 2022.

- 29.Iribarren SJ, Cato K, Falzon L, Stone PW. What is the economic evidence for mHealth? A systematic review of economic evaluations of mHealth solutions. PLoS ONE. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akter S, Ray P. mHealth - an Ultimate Platform to Serve the Unserved. Yearb Med Inform. 2010:94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavero-Redondo I, Martinez-Vizcaino V, Fernandez-Rodriguez R, Saz-Lara A, Pascual-Morena C, Alvarez-Bueno C. Effect of Behavioral Weight Management Interventions Using Lifestyle mHealth Self-Monitoring on Weight Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tucker CM, Butler AM, Loyuk IS, Desmond FF, Surrency SL. Predictors of a health-promoting lifestyle and behaviors among low-income african american mothers and white mothers of chronically III children. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.County D Community Health Assessment and Community-Health Improvement Plan 2012. 2012; http://duval.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/community-health-planning-and-statistics/_documents/chip.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2021.

- 34.Yarber L, Brownson CA, Jacob RR, et al. Evaluating a train-the-trainer approach for improving capacity for evidence-based decision making in public health. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tucker CM, Smith TM, Wippold GM, et al. Impact of a University-Community Partnership Approach to Improving Health Behaviors and Outcomes Among Overweight/Obese Hispanic Adults. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2017;11(6):479–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tucker CM, Wippold GM, Roncoroni J, et al. Impact of the Health-Smart Holistic Health Program: A CBPR Approach to Improve Health and Prevent Adverse Outcomes for Black Older Adults. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion. 2022;3(4):589–607. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID-19 and Older Adults: What We Know. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020;68(5):926–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, Chi JW, Lv WS, Wang YG. Obesity and diabetes as high-risk factors for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Diabetes-Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2021;37(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senteio CR, Hershey DS, Campbell T, Mandal S. Intergenerational Technology Transfer: Enhancing African American Older Adults’ Self-Efficacy for Diabetes Self-Management. Progress in Community Health Partnerships-Research Education and Action. 2021;15(4):453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Still CH, Jones LM, Moss KO, Variath M, Wright KD. African American Older Adults’ Perceived Use of Technology for Hypertension Self-Management. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11(5):249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity and Disease. 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, Redman S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promotion International. 2013;28(3):285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwasnicka D, Keller J, Perski O, et al. White Paper: Open Digital Health - accelerating transparent and scalable health promotion and treatment. Health Psychol Rev. 2022:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tucker CM, Shah NR, Ukonu NA, et al. Views of primary care physicians regarding the promotion of healthy lifestyles and weight management among their patients. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 2017;24:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henning-Smith C, Hernandez AM, Kozhimannil KB. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Self-Rated Health Among Rural Residents. Journal of Community Health. 2021;46(2):434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abshire DA, Wippold GM, Wilson DK, Pinto BM, Probst JC, Hardin JW. A qualitative study of ecological and motivational factors to inform weight management interventions for Black men in the rural South of the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2023:115898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foundation RWJ. Life in Rural America: Part II. 2019; https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/05/life-in-rural-america--part-ii.html.

- 48.Schoenberg N, Dunfee M, Yeager H, Rutledge M, Pfammatter A, Spring B. Rural Residents’ Perspectives on an mHealth or Personalized Health Coaching Intervention: Qualitative Study With Focus Groups and Key Informant Interviews. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(2):e18853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batsis JA, Petersen CL, Clark MM, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a technology-based, rural weight management intervention in older adults with obesity. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]