Abstract

Developmental literature suggests that susceptibility to social conformity pressure peaks in adolescence and disappears with maturity into early adulthood. Predictions about these behaviors are less clear for middle-aged and older adults. On the one hand, while age-related increases in prioritization of socioemotional goals might predict greater susceptibility to social conformity pressures, aging is also associated with enhanced emotion regulation that could support resistance to conformity pressures. In this exploratory research study, we used mobile experience sampling surveys to naturalistically track how 157 healthy adults between the ages of 18 and 80 practice self-control over spontaneous desires in daily life. Many of these desires were experienced in the presence of others enacting that desire. Results showed that middle-aged and older adults were better at controlling their desires than younger adults when desires were experienced in the presence of others enacting that desire. Consistent with the literature on improved emotion regulation with age, these results provide evidence that the ability to resist social conformity pressure is enhanced across the adult life span.

Keywords: aging, self-control, motivation, social conformity, experience sampling methods

Introduction:

Every day we encounter temptations that conflict with our goals of long-term health and wellbeing. Should I have a slice of chocolate cake at my niece’s birthday party if I’m trying to lose weight? Should I grab an expensive latte with coworkers if I’m trying to save money? These situations require us to exert self-control in the presence of others who are engaging in the temptation. Self-control involves the integration of immediate desires with higher order personal goals that are often associated with long-term benefits (Kotabe & Hofmann, 2015). Here, the conflict between these two forces (driven by their incompatibility) provides motivation to exert the control effort required to resist desires. If the amount of control effort exerted outweighs the strength of the desire, then, assuming there are no other constraints (like conformity pressures), the desire will be resisted. There is extensive empirical data demonstrating that the influence of others in the same social group, or social conformity effects, changes across early development. Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence suggests that resistance to social conformity increases from age 10 to young adulthood (Steinberg, 2005; Sumter et al., 2009) and a recent longitudinal meta-analysis showed a small but reliable effect of social conformity that is stable across childhood and adolescence (Giletta et al., 2021). According to dual process models (which contrast automatic and deliberative systems of decision making) (Evans, 2008), the development of competing affective and controlled brain systems favor greater balance between subcortical (affective) and prefrontal (control) systems in young adulthood (versus adolescence), which should decrease risk-taking and the influence of peers (Albert et al., 2013). Nevertheless, there is little empirical literature examining how social context impacts self-control in later development and aging.

Recent concerns over the sharing of misinformation among late-middle aged and older adults (Brashier & Schacter, 2020), along with the growing proportion of older adults in the US population, have raised new concerns about age-related susceptibility to social influence. Although no theories directly address the role of social context in adulthood, theoretical and empirical work can be combined to make predictions about how social context could have differential effects as people age. For instance, according to socioemotional selectivity theory (SST), socioemotional goals become more important with age (Carstensen, 1995, 2006). Specifically, prioritization of socioemotional goals (consistent with SST) has been demonstrated to begin in middle adulthood and strengthen in older age (Carstensen et al., 1999; Carstensen & Hershfield, 2021). Although SST does not make specific predictions about shifts in social conformity with age, this mechanism could drive middle-aged and older adults to be more susceptible to social context than younger adults. Evidence for SST-driven susceptibility to social contexts comes from work showing that older adults exhibit some degree of emotional closeness to strangers in storytelling (Bar-Tur & Levy-Shiff, 1994) and more generosity to strangers (Pornpattananangkul et al., 2019). One interpretation of this behavior is that as people age, they shift their goals to be “ego-transcending” and less focused on instrumental benefits to oneself (Brandtstädter et al., 2010). While much of the research on SST has identified that with age, socioemotional goals shift towards being with close others over strangers, ego-transcendence is not incompatible with SST (which emphasizes the importance placed on emotional closeness and meaningfulness). Both theories center shifts toward intrinsic goals and away from instrumental goals. A more closely related study investigating the influence of others’ preferences and motivations on older adults’ decisions to engage in physical activity found that whereas younger adults (aged 18–26 years) chose to exercise alone in pursuit of instrumental fitness goals, adults older than 59 years old preferred group exercises with strangers (Steltenpohl et al., 2019). Here, aging is associated with a shift away from instrumental goals and increased motivation to be around strangers to support more intrinsic emotional goals. One potential explanation is that shifts in socioemotional goals (associated with aging) increase susceptibility to conformity pressures from others. As the value of socioemotional connection increases, middle aged and older adults may be more likely to avoid social tension and go along with what others are doing. Conforming to others’ self-control behaviors could support socioemotional goals in middle aged and older adulthood by enhancing the intrinsically rewarding aspects of shared experiences, which have been shown to evoke activation in reward-related brain regions (Burke, 2010; Izuma & Adolphs, 2013; Klucharev et al., 2009).

On the other hand, middle-aged and older adults may be less susceptible to social context than younger adults. Despite cognitive control declines with age (Amer et al., 2016; Braver & Barch, 2002), emotional control and emotional stability has been shown to increase with age (Burr et al., 2020; Carstensen et al., 2011, 2020; Urry & Gross, 2010). SST might also predict that an increased focus on maximizing well-being in general might lead middle aged and older adults to better resist social influence. Additionally, people acquire knowledge, experience, and wisdom across their lives (Grossmann et al., 2010; Jeste & Lee, 2019; Park et al., 2002). An improvement in regulation in the face of social influence could be also consistent with the selective optimization with compensation (SOC) theory, which argues that increased motivation to invest in accumulated knowledge and familiar environments emerges in late-middle adulthood (50s) and strengthens in older age in order to maintain the status quo in the face of inevitable losses (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Teshale & Lachman, 2016). Here, SOC-driven stability in emotion regulation could enhance self-control in the face of social pressures. The very limited empirical evidence on this topic is mixed. One study found that Russian men become more resistant to social pressures of drinking alcohol from the 30s to the 60s (Keenan et al., 2015) and another study found that older adults conform less to social pressure than younger adults in a task during which participants categorized faces and shapes according to provided labels (Pasupathi, 1999). These findings are consistent with an early study that used a personality questionnaire in an adult life span sample to show that aging was correlated with less self-monitoring tendencies for behaving according to social cues (Reifman et al., 1989). These studies contrast an early finding that older adults are more susceptible to social influence during a visual perception decision experiment in which each participant was exposed to three additional participants and their decisions in the task (Klein, 1972). Further, a recent study has shown that younger and older adults are equally susceptible to social influence during a delay discounting task, exhibiting more similar preferences to a social partner after collaborating on the task (Bixter & Rogers, 2019). Since most of these studies test decisions made in controlled lab experiments in extreme group comparisons (younger adults versus older adults), it is unclear if they generalize to spontaneous everyday behaviors outside the lab and across adulthood.

Here we present an exploratory study of existing data to begin to fill in these gaps. Using experience sampling data collected across three samples of healthy women and men, we examined the influence of others enacting a spontaneously experienced desire on self-control across adulthood.

Method:

Transparency and Openness

We report how we determined our sample size, any data exclusions, and all measures in the study. The deidentified data, materials, and code for statistical analysis are available on OSF (See Author’s Note) (Castrellon et al., 2023). Data were analyzed using R Statistical Software (v4.0.3; (R Core Team, 2020)). The study design, hypotheses, and analyses were not pre-registered.

Participants and Materials

157 healthy adults across the adult life span (ages 18–80, M = 34.6, SD = 11.7, 86 women) across 3 study samples received surveys delivered via text message three times per day for 10 days as part of an experience sampling protocol adapted from (Hofmann, Baumeister, et al., 2012; Hofmann, Vohs, et al., 2012). Participants were recruited as part of larger multi-visit neuroimaging studies of decision making and self-control. Sample 1 included 20 younger adults (ages 18–24, M = 21.1, SD = 1.92, 10 females) recruited from the Vanderbilt University community in Nashville, TN between 2012 and 2013 using an online campus study recruitment website and paper flyers. Sample 2 (40 adults (ages 22–80, M = 44.7, SD = 17.6, 21 females)) and Sample 3 (43 healthy adults (ages 20–65, M = 42.0, SD = 15.4, 22 females)) were recruited from the Greater Nashville area (from 2013–2016 and 2016–2018, respectively) using online databases (ResearchMatch, Craigslist, and 50Forward), word-of-mouth, paper flyers, radio and television advertisements, and Facebook advertisements. Data from all samples were collected at Vanderbilt University. Exclusion criteria included major medical disorders, psychiatric illness on a screening interview (a Structural Interview for Clinical DSM-IV Diagnosis was also available for all subjects and confirmed no history of major Axis I disorders) (First et al., 1997), substance use, and contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging as part of larger studies. Partial data from samples 2 and 3 were previously reported in (Burr et al., 2020). Data collection for each sample was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board under the following study titles: Dopamine influences on self-regulation and impulsivity (sample 1), Dopaminergic modulation of subjective valuation across adulthood (sample 2), and Dopaminergic neuromodulation of decision making in young and middle-aged adults (sample 3). Participant demographics are presented in Table 1. Since this analysis was exploratory, we did not run an a priori power analysis however we report the results of a sensitivity analysis in the results section to evaluate the smallest effect size we could have detected given our sample size.

Table 1.

Participant demographics across samples.

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 49 | 45 | 63 | - |

| Mean Age | 20.4 ± 1.92 | 44.1 ± 17.7 | 39.4 ± 15.6 | F(2,154) = 40.8, p < 0.001 |

| Age Group N | ||||

| 18–29 | 49 | 12 | 34 | - |

| 30–39 | 0 | 10 | 0 | - |

| 40–49 | 0 | 6 | 0 | - |

| 50–59 | 0 | 7 | 26 | - |

| 60–69 | 0 | 5 | 3 | - |

| 70–80 | 0 | 5 | 0 | - |

| Sex | 30 F, 19 M | 24 F, 21 M | 32 F, 31 M | Χ2 (2, N=157) = 1.26, p = 0.532 |

| Mean Years Education | 14.3 ± 1.53 | 16.1 ± 1.99 | 16.1 ± 2.17 | F(2,148) = 14.4, p < 0.001 |

| Mean Household Income | - | $60K – 70K | $60K – 70K | F(1,100) = 0.00, p = 0.995 |

| Race/Ethnicity N | ||||

| White | 28 | 32 | 31 | - |

| Black | 3 | 6 | 6 | - |

| Hispanic | 3 | 1 | 3 | - |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 13 | 1 | 2 | - |

| More than 1 Race | 2 | 0 | 1 | - |

Note: Not all participants indicated their race/ethnicity (5 in Sample 2 and 20 in Sample 3).

Experience Sampling

During a visit to the lab, participants were first asked to provide their typical times for: waking, sleeping, eating lunch, and eating dinner. These time-points served as individually-tailored boundaries for text message deliveries to ensure that messages were not disruptive of participants’ sleep. Text messages with links to the web-based survey were programmed for delivery using OhDontForget.com. Each participant received three text messages per day for ten days (90 messages total). The exact time of delivery per day was pseudorandomized based on the time points of waking, sleeping, and eating provided by the participant. The experience sampling protocol was adapted from (Hofmann, Baumeister, et al., 2012; Hofmann, Vohs, et al., 2012).

Participants were instructed to respond to the messages (by clicking on the link and completing the survey in the web browser on their phone) as soon as they received them as long as they could safely do so (e.g. if participants received a text message while driving, they were instructed to wait until their drive was complete/when it was safe to respond). If participants did not have a smartphone that could render the survey webpage, a smartphone was provided for them to use during the course of experience sampling data collection. Participants were instructed to report their strongest desires experienced in the last three hours. Each survey permitted entry of up to three desires.

Each participant was first asked to indicate where they were and if they experienced a desire (craving, urge, longing) in the past three hours. They were provided with 13 desire options:

Eating, snacking, nonalcoholic drinks

Alcohol, cigarettes, tobacco, other drugs

Entertainment media (TV, movies, web browsing, video games)

Social Media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.)

Spending

Sex

Sleep

Social Contact (in person or phone conversation, texting, FaceTime, etc.)

Leisure and relaxation

Exercise

Work

Other

None

If participant selected “Other,” they were prompted to provide a description of their desire. After selecting a desire, the participant indicated the strength of the desire on a scale from 0 (no desire at all) to 7 (irresistible). Next, each participant was asked how much the desire conflicted with personal goals on a scale from 0 (no conflict at all) to 4 (very high conflict). If they identified that the desire conflicted with a goal, the participant was asked to categorize the conflicting goal. They were provided with 12 goal options:

Healthy living (healthy eating, healthy drinking, reducing health damage, bodily fitness, good appearance, ending dependency)

Saving money

Abstinence

Educational achievement

Professional achievement

Sport achievement

Social goals (social appearance, social recognition, socializing)

Moral Integrity (fidelity, religious/cultural beliefs)

Using time efficiently

Not delaying things and getting things done

Leisure and Relaxation

Other

If participants selected “Other” they were once again prompted to provide a description of their desire. Finally, the participants were asked to indicate if they attempted to resist the desire (Yes or No), if they enacted the desire (Yes or No), and if other people present (either physically or via media (phone call, text messaging, etc.)) were enacting the desire (Yes or No). The most frequently reported desires were “Eating, snacking, nonalcoholic drinks,” “Sleep,” and “Leisure and Travel.” Desires reported as “other” included activities that ranged from playing music and writing to chores like cleaning or showering.

Statistical Analysis

The data analyzed includes participants who responded to at least half of the minimum possible number of surveys (15/30 minimum surveys). Data also excludes participants who did not vary at all in either their goal conflict or desire strength ratings. Prior to analysis, we excluded extreme desire and goal conflict ratings with a within-participant standardized Z-score +/− 3. This resulted in exclusion of 50 individual desires. These exclusions did not amount to exclusion of any participants. This provided a final sample size of N = 157. All descriptive statistics (including those indicated in the Participants and Procedures section above) reflect data from these final 157 participants.

To test the interaction between age and social context on self-control decisions, we used multi-level logistic regression in R using the “lme4” package and fit using the “glmer” function with the BOBYQA (Bound Optimization BY Quadratic Approximation) (Powell, 2009) optimizer with random intercepts for participants (to account for inter-individual variability). The dependent variable was resistance attempt (attempt versus no attempt) and, separately, resistance success (note we use the term resistance success for all cases in which the person did not enact the desire, regardless of whether the person reported a conscious effort to resist the desire). We report standardized regression coefficients of predictor variables of interest and use these measures to capture sensitivity to social conformity pressure in decisions to attempt and successfully resist desires. All analyses controlled for participant sex and study sample and standardized ages across participants in the entire dataset. Specifically, our models tested (1) the interaction between age and social context (others present enacting) on resistance attempts and (2) the interaction between age, resistance attempt, and social context on resistance success. To facilitate interpretation of cross-level interactions, we conducted simple slopes analysis to identify effects for participants belonging to younger (−1 SD, approximately 18 years old), average (approximately 35 years old), and older (+1 SD, approximately 52 years old) ages. Simple slopes analysis was carried out using the “jtools” and “interactions” R packages.

On average, across the 10 days of experience sampling, participants reported 56.5 (SD = 19.7) individual desires, of which they attempted to resist 19.8 desires (SD = 13.4). The average desire strength rating was 6.28 (SD = 0.25) out of 7 and the average personal goal conflict was rated 2.97 (SD = 0.40) out of 4. We report the relationship between desire regulation and ratings in a separate manuscript (Castrellon et al., 2021). The participant and observation-level sample sizes were based on the original reports by Hofmann and colleagues which sampled 205 adults to obtain 7,827 reported experienced desires (Hofmann, Baumeister, et al., 2012; Hofmann, Vohs, et al., 2012). The entire dataset we report here included 8,905 observations of experienced desires for analyses. See Table 2 for frequencies of desire and personal goal conflict types that were reported by young, middle-aged, and older adult participants. We note that the main effects of desires and personal goals on self-control in this experience sampling protocol (reported in (Castrellon et al., 2021)) have been replicated by other labs sampling 225 younger adults (Krönke et al., 2018), 31 younger adult females (Lopez et al., 2014), and 338 younger adults (Wolff et al., 2021).

Table 2.

Reported desire and personal goal conflict frequency for young, middle-aged, and older adults.

| Younger adults (18–30) | Middle-aged adults (31–59) | Older adults (60+) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Desire Type | N | % of total desires | N | % of total desires | N | % of total desires |

| Snacks or soft drinks | 1493 | 28 | 831 | 30 | 191 | 26 |

| Alcohol or drugs | 205 | 4 | 64 | 2 | 18 | 2 |

| Entertainment media | 529 | 10 | 259 | 9 | 94 | 13 |

| Social media | 341 | 6 | 155 | 6 | 33 | 4 |

| Spending | 111 | 2 | 68 | 2 | 23 | 3 |

| Sex | 175 | 3 | 66 | 2 | 14 | 2 |

| Sleep | 851 | 16 | 213 | 8 | 49 | 7 |

| Social Contact | 533 | 10 | 303 | 11 | 81 | 11 |

| Leisure and Travel | 552 | 10 | 294 | 11 | 92 | 12 |

| Exercise | 268 | 5 | 168 | 6 | 20 | 3 |

| Work | 274 | 5 | 241 | 9 | 80 | 11 |

| Other | 88 | 2 | 83 | 3 | 45 | 6 |

|

| ||||||

| Conflict Type | N | % of total conflicts | N | % of total conflicts | N | % of total conflicts |

|

| ||||||

| Healthy living | 533 | 19 | 192 | 21 | 27 | 12 |

| Saving money | 156 | 6 | 37 | 4 | 12 | 5 |

| Abstinence | 16 | 1 | 27 | 3 | 1 | <1 |

| Educational achievement | 597 | 21 | 25 | 3 | N/A | N/A |

| Professional achievement | 283 | 10 | 114 | 13 | 21 | 9 |

| Sport Achievement | 18 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Social goals | 135 | 5 | 14 | 2 | 13 | 6 |

| Moral Integrity | 74 | 3 | 41 | 5 | 9 | 4 |

| Using time efficiently | 465 | 17 | 189 | 21 | 90 | 39 |

| Not procrastinating | 366 | 13 | 190 | 21 | 34 | 15 |

| Leisure and Relaxation | 131 | 5 | 41 | 5 | 13 | 6 |

| Other | 43 | 2 | 30 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

Results:

To test the influence of age and social context on self-control, we first modeled the two-way interaction between age and whether others were present enacting the desire on resistance attempts. Although the main effects of social context (β = −1.22, 95% CI [−1.33, −1.11], Z = −21.4, p < 0.001) and age (β = −0.40, 95% CI [−0.63, −0.18], Z = −3.51, p < 0.001) were statistically significant, their interaction (β = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.17, 0.08], Z = −0.74, p = 0.462) did not indicate that age-related differences were present in decisions to attempt to resist desires when conformity pressures vary. See Table 3 for regression coefficients.

Table 3. Effects of age and social context on attempts to resist desires.

Regression coefficients are standardized. 95% confidence intervals appear beside coefficients in brackets.

| Resistance Attempt | |

|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.30 [−0.63, 0.02] |

| Male | 0.15 [−0.20, 0.49] |

| Sample 1 | 0.08 [−0.39, 0.55] |

| Sample 2 | −0.23 [−0.66, 0.20] |

| Age | −0.40 *** [−0.63, −0.18] |

| Others Present Enacting | −1.22 *** [−1.33, −1.11] |

| Age x Others Present Enacting | −0.05 [−0.17, 0.08] |

| N (Observation) | 8904 |

| N (Subject) | 157 |

| AIC | 9783.04 |

| BIC | 9839.80 |

| R2 (fixed) | 0.13 |

| R2 (total) | 0.34 |

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

While attempts capture motivation to practice self-control, they do not necessarily reflect successful regulation. We therefore examined the three-way interaction between age, social context, and resistance attempt on successful resistance of desires. Here, we identified statistically significant main effects of age (β = −0.36, 95% CI [−0.58, −0.14], Z = −3.26, p = 0.001), social context (β = −1.60, 95% CI [−1.82, −1.39], Z = −14.5, p < 0.001), and resistance attempt (β = 3.14, 95% CI [2.96, 3.32], Z = 34.6, p < 0.001). The significant two-way interaction between social context and resistance attempt (β = 0.62, 95% CI [0.33, 0.90], Z = 4.23, p < 0.001) indicated that conformity pressures have a greater influence on successful regulation for consciously-resisted desires than desires for which no attempt was made to resist. The significant two-way interaction between age and resistance attempt (β = 0.56, 95% CI [0.37, 0.76], Z = 5.62, p < 0.001) indicated that higher age was associated with better success at regulating consciously resisted desires compared to desires for which no attempt was made to resist. Central to our interest here, the significant two-way interaction between age and social context (β = 0.44, 95% CI [0.24, 0.64], Z = 4.23, p < 0.001) indicated that aging was associated with a lower influence of the presence of others enacting a desire. Finally, the significant three-way interaction (β = −0.31, 95% CI [−0.61, −0.02], Z = −2.07, p = 0.039) indicated that age-related differences in sensitivity to social context depended on whether desires were actively resisted. See Table 4 for regression coefficients. To evaluate the robustness of the interaction between age and social context on resistance success, we ran a sensitivity analysis to determine the minimum detectable effect size given our sample size (Davis et al., 2018). We used the “simr” package in R to simulate different effect sizes between 0.1 and 0.6 (incremented by 0.1) for the interaction between age and social context and estimated statistical power for an alpha of 0.05. Each effect size was simulated 1,000 times. This test indicated that our observed effect size (0.44) had over 98% power and that an effect size of 0.3 would have 84% power.

Table 4. Effects of age and social context on successful resistance of desires.

Regression coefficients are standardized. 95% confidence intervals appear beside coefficients in brackets.

| Resistance Success | |

|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.87 *** [−2.17, −1.57] |

| Male | 0.11 [−0.19, 0.41] |

| Sample 1 | 0.37 [−0.04, 0.78] |

| Sample 2 | −0.22 [−0.59, 0.16] |

| Age | −0.36 ** [−0.58, −0.14] |

| Resistance Attempt | 3.14 *** [2.96, 3.32] |

| Others Present Enacting | −1.60 *** [−1.82, −1.39] |

| Resistance Attempt x Others Present Enacting | 0.62 *** [0.33, 0.90] |

| Age x Resistance Attempt | 0.56 *** [0.37, 0.76] |

| Age x Others Present Enacting | 0.44 *** [0.24, 0.64] |

| Age x Resistance Attempt x Others Present Enacting | −0.31 * [−0.61, −0.02] |

| N (Observation) | 8904 |

| N (Subject) | 157 |

| AIC | 6782.33 |

| BIC | 6867.46 |

| R2 (fixed) | 0.48 |

| R2 (total) | 0.57 |

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

We next tested the robustness of the desire resistance success model with additional covariates. In this dataset, age was not related to years of education (β = 0.21, CI [−0.130, 0.548], t(149) = 1.22 p = 0.225) but it was related to income level β = 1.66, CI [0.90, 2.42], t(100) = 4.33 p < 0.001) and differences in race/ethnicity in the sample (Kruskal-Wallis test H(4) = 20.8, p = 0.0003). However, due to differences in study reporting protocols and non-reported information by participants, race/ethnicity and income data were not available for 74 participants. Nevertheless, a follow-up model for resistance success with the remaining 84 participants indicated that the interaction between age and social context remained largely unchanged (β = 0.44, CI [0.15, 0.74], Z = 2.97, p = 0.003). See Table S1 in Supplementary Materials for full regression results of the covariate model.

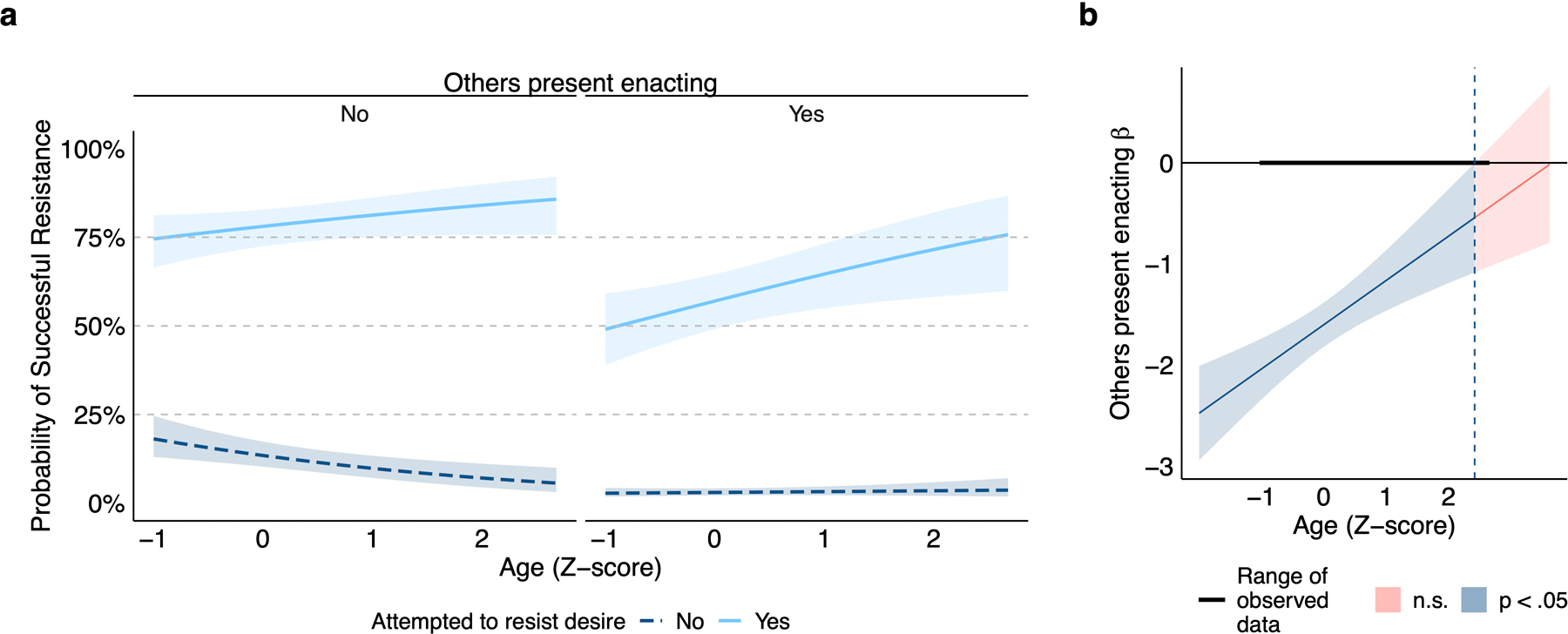

To facilitate interpretation of the cross-level interaction between age and social context on desire resistance success, we conducted simple slopes analysis to identify estimates for participants with from younger adults (−1 SD), middle-aged adults, and older adults (+1 SD) in the sample and plotted the marginal effects using a Johnson-Neyman plot (Fig. 1). Inspection of the coefficients from the simple slopes analysis indicated that whereas younger adults are less successful at regulating desires when experienced in the presence of others enacting those desires (−1 SD, approximately 18 years old: β = −2.04, CI [−2.34, −1.74], Z = −13.4, p < 0.001), middle-aged adults (Mean, approximately 35 years old: β = −1.60, CI [−1.82, −1.39], Z = −14.5, p < 0.001) were less affected by this conformity pressure. Critically, older adults (+1 SD, approximately 52 years old: β = −1.16, CI [−1.46, −0.87], Z = −7.69, p < 0.001) were substantially less affected by social conformity pressures evidenced by a less negative regression coefficient. It is important to note that 32.5% of the participants in the +1 SD group are over the age of 59, and this +1 SD group is comprised of primarily middle-aged and late middle-aged adults. A follow-up regression controlling for sex and study sample tested whether age was related to the proportion of reported desires that were experienced with social conformity pressures. One possibility is that middle-aged and older adults might have fewer social interactions which could translate into fewer opportunities to be influenced by others. However, age was not correlated with the proportion of reported desires experienced in the presence of conformity pressure (β = 0.19, CI [−0.005, 0.38], Z = 1.92, p = 0.056), indicating that age is associated with greater resistance to social conformity pressure despite invariance in exposure to others enacting a desire they are experiencing.

Figure 1.

Social conformity effects on everyday self-control. (a) Whereas younger adults are less successful at regulating desires when others are present enacting those desires, older adults are less affected by a conformity pressure social context. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval. (b) Johnson-Neyman plot for the conditional effect of social context on successful desire resistance (regardless of resistance attempt). The standardized slope (β) is less negative for middle-aged and older compared to younger adults, indicating that these age groups experience a lower negative effect of conformity pressure on self-control success compared to younger adults. The area shaded in red indicates the slopes that are not statistically different from zero. The dashed vertical line indicates the boundary at which the slope becomes non-significant. Age is standardized across the sample with the following estimations for interpretation: −1z = 17.9actual, 0z = 34.8 actual, 1z = 51.7 actual, 2z = 68.6 actual). All shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Using experience sampling, we examined the influence of others enacting a desire on self-control across the adult life span. Results revealed that adult age-related differences partially explain sensitivity to social conformity pressure in real-world self-control decisions. Whereas younger adults were less successful at regulating desires when others were around enacting those desires, middle-aged and older adults successfully resisted desires despite this social context. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine social conformity on self-control across the adult life span.

These results are somewhat surprising. The developmental literature suggests that the influence of others on behavior wanes across late adolescence, possibly disappearing in adulthood (Chein et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2015). This developmental change has largely been explained using dual process models, where choices are influenced by two brain systems: an affective system and a controlled system (Albert et al., 2013). Whereas the affective system is comprised of regions like the ventral striatum and insular cortex that are sensitive to the hedonic value of actions, the controlled system is comprised of the prefrontal cortex and is focused on goal-directed action. Critically, these two systems differ in their age-related development; adolescence is marked by increased reactivity of the affective system coupled with continued development of the controlled system. The relative imbalance of activity in these systems during adolescence is thought to lead to increased risk-taking (Albert et al., 2013). Further, in adolescence, the reactivity of the affective system is even more increased by the presence of peers (Chein et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2015). As the prefrontal cortex matures in young adulthood, the two systems become more balanced, risk-taking declines, and the influence of peers is eliminated (Albert et al., 2013). Indeed, in risk taking paradigms the effect of peer presence is substantially diminished after adolescence (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005).

Here, we find that the social presence effect is present though more limited in middle age compared to young adulthood. While the present age differences in social conformity are consistent with a linear developmental trajectory of deliberative decision making from adolescence to young adulthood, there are important distinctions between our study and prior developmental work. First, the developmental literature has largely focused on extreme, anti-social and/or risky behavior (e.g., substance abuse, drunk driving, risky sex), while this study focused on regulating more mundane, everyday desires (i.e., checking social media, having a single glass of wine). It is possible that the middle-aged individuals in our study would not be strongly influenced by others if queried about more extreme behaviors. Second, prior literature has largely focused on retrospective self-report on experiences in past days, months, or years, while this study used experience sampling in which participants reported experiences within the past 3 hours. Retrospective self-reports rely on memory, and biases in the accurate recall of experience can influence these measurements (Shiffman et al., 2008). By using experience sampling, we minimized the influence of recall bias for temporally distant events, and it is possible that using experience sampling in developmental populations would lead to less extreme estimates of peer influence on behavior.

We found that that the effect of social conformity pressures on regulating everyday desires generally diminishes across adulthood. One possible explanation for this is that age-related enhancement of emotion regulation (Burr et al., 2020; Urry & Gross, 2010) extends to social conformity. As discussed above, dual process models suggest that social conformity acts through emotional arousal. It is possible that middle-aged and older adults are better able to regulate emotional responses to social conformity pressure, and thus overcome everyday temptations. Support for this explanation in survey data indicates that as people age, they engage in less self-monitoring of their behaviors (Reifman et al., 1989). Since enhanced emotion regulation has been associated with a greater sense of self-consistency or authenticity of one’s own behaviors among older adults (English & John, 2013), aging may limit the impact of others as a result of increased confidence in a person’s sense of self and what is congruent with their history of desire regulation. Additional support for a reduced influence of social conformity pressure in aging comes from lab experiments showing greater resistance to conformity pressure in perceptual decision making (Pasupathi, 1999) and delay discounting (Bixter & Rogers, 2019). Whereas these experiments manipulated participants’ exposure to others’ decisions, we find that middle-aged and older adults are also resistant to a more naturalistic presence that could induce pressure to conform.

In laboratory studies, inhibitory control involving response interference and intertemporal choice is preserved in older adults (Rey-Mermet & Gade, 2018; Seaman et al., 2022; Williams et al., 1999). These preserved abilities may contribute to the self-control in daily life observed in our study. Paired with a greater ability to regulate emotional responses, middle-aged and older adults’ preserved motivation for long term goals when spontaneous desires arise may be sufficient to overcome social conformity pressures. Consistent with selective optimization with compensation theory of aging (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Penningroth & Scott, 2012; Teshale & Lachman, 2016), middle-aged and older adults rely on their preserved cognitive resources to focus their efforts toward goals that minimize age-related health losses and maintain current wellbeing when social pressures might detract from such goals like consumption of alcohol or unhealthy snacks.

While age was not significantly related to the average strength of desires in this sample (t(155) = 1.67, p = 0.097), there was a negative correlation between age and average personal goal conflict ratings (t(155) = −5.0853, p < 0.001). This could suggest that: (1) relative to younger adults, middle-aged and older adults perceive their goals to be less conflicted with their desires or (2) the goals they set for themselves do not actually conflict as strongly with their desires compared to younger adults. Future experience sampling studies with larger sample sizes could probe the consequences of these differences by testing whether age differences modulate sensitivity to personal goal conflict when deciding whether to practice self-control around others. The kinds of desires and personal goal conflicts reported might contribute to age differences in susceptibility to conformity pressures. For example, whereas alcohol and drugs accounted for 4% of desires reported by younger adults, these substances were only 2% of the desires reported by middle-aged and older adults. Many of the younger adults in our study were in college, where they are more likely to encounter substance-related peer pressure (Borsari & Carey, 2001). This likely increases the potential to enact a desire to consume alcohol or other drugs compared to non-college student participants. Time-related personal goal conflicts (using time efficiently and not procrastinating) accounted for 30% of younger adults’ personal goal conflicts, 42% of middle-aged adults’ personal goal conflicts, and 54% of older adults’ personal goal conflicts. These linear age differences likely reflect a perceived limited time horizon with increasing age (Fredrickson & Carstensen, 1990; Lang & Carstensen, 2002; Strough et al., 2016), which may increase the cost of engaging in specific desires that participants might consider “wasteful” of time. Perhaps an increased salience of future time among middle-aged and older adults boosts the importance of time-related personal goals that conflict with social conformity pressures. Future self-control experience sampling studies should probe participants about their future time perspective to test this hypothesis.

There are some limitations to our work, which point to important considerations for future studies. For example, future work will require higher representation of older adults as this study included few participants in typical older adult age range (ages 60+). Specifically, the present data includes 39 participants between 40 and 59 years old and 13 participants over 60 years old. This limits our confidence in how representative our results are of older adulthood experiences beyond the age of 60 years old. Nevertheless, middle-aged individuals are an overlooked group who experience age-related shifts in socioemotional and cognitive function (to a lesser degree than older adults). Accordingly, our inclusion of these individuals offers important insight about how self-control abilities might begin to shift since middle-adulthood represents a time when the future begins to feel more limited (Strough et al., 2016) and inhibitory control is relatively spared (Williams et al., 1999) compared to young adulthood. Our observation that middle-aged adults show greater resistance to social conformity pressures than younger adults indicates that these differences in social-cognitive functions may follow a linear trajectory. Future longitudinal work could therefore identify whether self-control abilities in middle adulthood predict such abilities in older adulthood.

We did not query participants about their relationship to the individuals present when resisting a desire. Better characterization of the nature and quality of the social relationships involved is critical, as it is possible that only close social partners would successfully exert social conformity pressure on older individuals, given prior data on the manner in which older adults prioritize social close partners compared to younger and middle-aged adults (Fredrickson & Carstensen, 1990; Fung et al., 1999). Prior work indicates that older adults narrow their social circles to close others over strangers (Carstensen, 1992), yet their behaviors are still motivated by unknown others (Pornpattananangkul et al., 2019; Steltenpohl et al., 2019), even if shifting toward intrinsic socioemotional goals (Brandtstädter et al., 2010). It thus remains to be seen whether middle-aged and older adults (compared to younger adults) show a differential sensitivity to the influence of strangers and close others in self-control behaviors.

It is also important to consider the type of behavior being regulated. In this and in most developmental studies, social conformity effects are measured in reference to engaging in self-serving temptations or desires. It is possible that social conformity pressure could act on prosocial goals that are also in conflict with an individual’s long-term goals. A growing body of research suggests that older adults are more prosocial than younger adults (Cutler et al., 2021; Sparrow et al., 2021); thus, we may see adult age differences in resistance to social conformity when engaging in prosocial behavior. Social conformity pressure can also push people to engage in behaviors that are ultimately good for them. For instance, a recent study found that gamification of geocaching, and the resulting social competition, encouraged older adults to engage in physical activity (Fornasini et al., 2020). Thus, it is possible that social conformity pressures have a differential impact based on what kind of behavior individuals are engaging in. Another important design limitation is that this is a cross-sectional study. These results are susceptible to the problems associated with assuming rates of change over time from the behavior of different individuals. Carefully designed longitudinal experiments are needed to characterize how susceptibility to social pressure changes across the life span into middle adulthood and older age. Another limitation of the study design is that desires are self-reported. It is not possible for us to know whether participants selectively reported desires. Here, most participants indicated nearly two times the minimum number (30) of desires that could be reported (median = 59) and only 19 participants reported fewer than 30 desires, alleviating some concerns about compliance. Importantly, age was not correlated with the number of desires reported (r = 0.03, t(155) = 0.48, p = 0.628), suggesting that age-related differences cannot solely be explained by compliance. A greater concern is the extent to which accurate reporting is dependent on retrospective memory quality. We attempt to alleviate this by sampling three times per day and asking participants to recall experiences in the past three hours. Nevertheless, age-related changes in memory retrieval abilities (Burke & Light, 1981; Korkki et al., 2020) could bias experience sampling reporting. Future iterations of this study could sample more frequently to determine the extent to which selective or accurate desire reporting depends on age differences in memory quality. Further, we did not ask participants to identify whether others enacting their desire were doing so over social media versus in-person. Given recent concerns about spreading of false information online among older adults (Brashier & Schacter, 2020), future work should identify whether age-related increases in resilience to conformity pressures is specific to the physical presence of others or generalizes to online/social media environments.

The general behavioral patterns we observed are consistent with prior studies using the same experience sampling paradigm in young adults (Krönke et al., 2018; Lopez et al., 2014; Wolff et al., 2021). Nevertheless, there are countless individual differences and situational factors, like time of day (Hofmann, Vohs, et al., 2012) or location (Hofmann, Baumeister, et al., 2012), that may contribute to self-reported self-control abilities. Future work should explore how these factors might depend on age to shape susceptibility to social conformity pressures. Finally, this was a purely data-driven, exploratory study. Hypothesis-driven research designs are needed to test all the interpretations presented here.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the susceptibility to social conformity pressures on urges across adulthood. The finding that social conformity pressures are negatively associated with age raises important questions about the nature of social conformity as people are increasingly more interconnected through online social media and middle-aged and older adults are the most susceptible to misinformation (Brashier & Schacter, 2020). More research is needed to better characterize how social conformity pressure changes across adulthood, particularly as older adults become an increasingly more prominent and powerful subset of our society.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement:

People regularly experience and resist temptations in daily life. Successful resistance of desires can be especially difficult when others are around enacting those desires. The current study demonstrates that compared to younger adults, middle-aged and older adults are less susceptible to conformity pressures from others enacting a desire when practicing self-control in daily life.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging grants R01-AG044838 and R01-AG043458, and National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R21-DA033611. J.J.C. was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (grant no. NSF DGE-1644868). Thanks to Kalila Houston and Nubia Celis-Etienne for assistance with the literature review when preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this manuscript was posted on the PsyArXiv preprint server (https://psyarxiv.com/6s8vr) in January 2023.

Data Availability:

De-identified data, materials, and code used in the manuscript can be viewed and downloaded from OSF: https://osf.io/4kf3a/

References

- Albert D, Chein J, & Steinberg L (2013). The Teenage Brain: Peer Influences on Adolescent Decision Making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 114–120. 10.1177/0963721412471347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer T, Campbell KL, & Hasher L (2016). Cognitive Control As a Double-Edged Sword. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(12), 905–915. 10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, & Baltes MM (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Baltes PB & Baltes MM (Eds.), Successful Aging: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences (pp. 1–34). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511665684.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tur L, & Levy-Shiff R (1994). Holocaust Review and Bearing Witness as a Coping Mechanism of an Elderly Holocaust Survivor. Clinical Gerontologist, 14(3), 5–16. 10.1300/J018v14n03_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bixter MT, & Rogers WA (2019). Age‐related differences in delay discounting: Immediate reward, reward magnitude, and social influence. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 32(4), 471–484. 10.1002/bdm.2124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, & Carey KB (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391–424. 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Rothermund K, Kranz D, & Kühn W (2010). Final Decentrations: Personal Goals, Rationality Perspectives, and the Awareness of Life’s Finitude. European Psychologist, 15(2), 152–163. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brashier NM, & Schacter DL (2020). Aging in an Era of Fake News. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 096372142091587. 10.1177/0963721420915872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Braver TS, & Barch DM (2002). A theory of cognitive control, aging cognition, and neuromodulation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 26(7), 809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke. (2010). Striatal BOLD response reflects the impact of herd information on financial decisions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burke DM, & Light LL (1981). Memory and aging: The role of retrieval processes. Psychological Bulletin, 90(3), 513–546. 10.1037/0033-2909.90.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr DA, Castrellon JJ, Zald DH, & Samanez-Larkin GR (2020). Emotion dynamics across adulthood in everyday life: Older adults are more emotionally stable and better at regulating desires. Emotion 10.1037/emo0000734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carstensen LL (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 331–338. 10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL (1995). Evidence for a Life-Span Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 151–156. 10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL (2006). The Influence of a Sense of Time on Human Development. Science, 312(5782), 1913–1915. 10.1126/science.1127488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, & Hershfield HE (2021). Beyond Stereotypes: Using Socioemotional Selectivity Theory to Improve Messaging to Older Adults. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(4), 327–334. 10.1177/09637214211011468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, & Charles ST (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Shavit YZ, & Barnes JT (2020). Age Advantages in Emotional Experience Persist Even Under Threat From the COVID-19 Pandemic 10.31124/advance.13022042.v1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Brooks KP, & Nesselroade JR (2011). Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging, 26(1), 21–33. 10.1037/a0021285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrellon JJ, Young JS, Dang LC, Smith CT, Cowan RL, Zald DH, & Samanez-Larkin GR (2021). Dopamine biases sensitivity to personal goals and social influence in self-control over everyday desires [Preprint]. Neuroscience 10.1101/2021.09.10.459829 [DOI]

- Castrellon Jaime, Zald David, Samanez-Larkin Gregory, & Seaman Kendra. (2023). Adult age-related differences in susceptibility to social conformity pressures in self-control over daily desires [dataset]. The Open Science Framework osf.io/4kf3a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chein J, Albert D, O’Brien L, Uckert K, & Steinberg L (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), F1–F10. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler J, Wittmann M, Abdurahman A, Hargitai L, Drew D, Husain M, & Lockwood P (2021). Ageing disrupts reinforcement learning whilst learning to help others is preserved. Nature Communications, 12(4440), 1–46. 10.1038/s41467-021-24576-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis WE, Giner-Sorolla R, Lindsay DS, Lougheed JP, Makel MC, Meier ME, Sun J, Vaughn LA, & Zelenski JM (2018). Peer-Review Guidelines Promoting Replicability and Transparency in Psychological Science. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(4), 556–573. 10.1177/2515245918806489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English T, & John OP (2013). Understanding the social effects of emotion regulation: The mediating role of authenticity for individual differences in suppression. Emotion, 13(2), 314–329. 10.1037/a0029847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J St. B. T. (2008). Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 255–278. 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Benjamin LS, & Williams JB (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis II Personality Disorders SCID-II. American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Fornasini S, Dianti M, Bacchiega A, Forti S, & Conforti D (2020). Using Geocaching to Promote Active Aging: Qualitative Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e15339. 10.2196/15339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Carstensen LL (1990). Choosing social partners: How old age and anticipated endings make people more selective. Psychology and Aging, 5(3), 335–347. 10.1037/0882-7974.5.3.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Carstensen LL, & Lutz AM (1999). Influence of time on social preferences: Implications for life-span development. Psychology and Aging, 14(4), 595–604. 10.1037/0882-7974.14.4.595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, & Steinberg L (2005). Peer Influence on Risk Taking, Risk Preference, and Risky Decision Making in Adolescence and Adulthood: An Experimental Study. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 625–635. 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giletta M, Choukas-Bradley S, Maes M, Linthicum KP, Card NA, & Prinstein MJ (2021). A meta-analysis of longitudinal peer influence effects in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 147, 719–747. 10.1037/bul0000329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I, Na J, Varnum MEW, Park DC, Kitayama S, & Nisbett RE (2010). Reasoning about social conflicts improves into old age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(16), 7246–7250. 10.1073/pnas.1001715107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Baumeister RF, Förster G, & Vohs KD (2012). Everyday temptations: An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1318–1335. 10.1037/a0026545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Vohs KD, & Baumeister RF (2012). What People Desire, Feel Conflicted About, and Try to Resist in Everyday Life. Psychological Science, 23(6), 582–588. 10.1177/0956797612437426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuma K, & Adolphs R (2013). Social Manipulation of Preference in the Human Brain. Neuron, 78(3), 563–573. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, & Lee EE (2019). Emerging Empirical Science of Wisdom: Definition, Measurement, Neurobiology, Longevity, and Interventions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(3), 127–140. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Saburova L, Bobrova N, Elbourne D, Ashwin S, & Leon DA (2015). Social Factors Influencing Russian Male Alcohol Use over the Life Course: A Qualitative Study Investigating Age Based Social Norms, Masculinity, and Workplace Context. PLOS ONE, 10(11), e0142993. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL (1972). Age, Sex, and Task Difficulty as Predictors of Social Conformity. Journal of Gerontology, 27(2), 229–236. 10.1093/geronj/27.2.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klucharev V, Hytönen K, Rijpkema M, Smidts A, & Fernández G (2009). Reinforcement Learning Signal Predicts Social Conformity. Neuron, 61(1), 140–151. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkki SM, Richter FR, Jeyarathnarajah P, & Simons JS (2020). Healthy ageing reduces the precision of episodic memory retrieval. Psychology and Aging, 35(1), 124–142. 10.1037/pag0000432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotabe HP, & Hofmann W (2015). On Integrating the Components of Self-Control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 618–638. 10.1177/1745691615593382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krönke K-M, Wolff M, Mohr H, Kräplin A, Smolka MN, Bühringer G, & Goschke T (2018). Monitor yourself! Deficient error-related brain activity predicts real-life self-control failures. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 18(4), 622–637. 10.3758/s13415-018-0593-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR, & Carstensen LL (2002). Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychology and Aging, 17(1), 125–139. 10.1037/0882-7974.17.1.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez RB, Hofmann W, Wagner DD, Kelley WM, & Heatherton TF (2014). Neural Predictors of Giving in to Temptation in Daily Life. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1337–1344. 10.1177/0956797614531492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Lautenschlager G, Hedden T, Davidson NS, Smith AD, & Smith PK (2002). Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging, 17(2), 299–320. 10.1037/0882-7974.17.2.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M (1999). Age differences in response to conformity pressure for emotional and nonemotional material. Psychology and Aging, 14(1), 170–174. 10.1037/0882-7974.14.1.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penningroth SL, & Scott WD (2012). Age-Related Differences in Goals: Testing Predictions from Selection, Optimization, and Compensation Theory and Socioemotional Selectivity Theory. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 74(2), 87–111. 10.2190/AG.74.2.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pornpattananangkul N, Chowdhury A, Feng L, & Yu R (2019). Social Discounting in the Elderly: Senior Citizens are Good Samaritans to Strangers. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(1), 52–58. 10.1093/geronb/gbx040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell MJ (2009). The BOBYQA algorithm for bound constrained optimization without derivatives

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing

- Reifman A, Klein JG, & Murphy ST (1989). Self-monitoring and age. Psychology and Aging, 4(2), 245–246. 10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Mermet A, & Gade M (2018). Inhibition in aging: What is preserved? What declines? A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(5), 1695–1716. 10.3758/s13423-017-1384-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman KL, Abiodun SJ, Fenn Z, Samanez-Larkin GR, & Mata R (2022). Temporal discounting across adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 37(1), 111–124. 10.1037/pag0000634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, & Hufford MR (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Applied Clinical Trials, 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Steinberg L, Strang N, & Chein J (2015). Age differences in the impact of peers on adolescents’ and adults’ neural response to reward. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 11, 75–82. 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow EP, Swirsky LT, Kudus F, & Spaniol J (2021). Aging and altruism: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 36, 49–56. 10.1037/pag0000447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 69–74. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steltenpohl CN, Shuster M, Peist E, Pham A, & Mikels JA (2019). Me Time, or We Time? Age Differences in Motivation for Exercise. The Gerontologist, 59(4), 709–717. 10.1093/geront/gny038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J, Bruine De Bruin W, Parker AM, Lemaster P, Pichayayothin N, & Delaney R (2016). Hour glass half full or half empty? Future time perspective and preoccupation with negative events across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 31(6), 558–573. 10.1037/pag0000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumter SR, Bokhorst CL, Steinberg L, & Westenberg PM (2009). The developmental pattern of resistance to peer influence in adolescence: Will the teenager ever be able to resist? Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 1009–1021. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshale SM, & Lachman ME (2016). Managing daily happiness: The relationship between selection, optimization, and compensation strategies and well-being in adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 31(7), 687–692. 10.1037/pag0000132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, & Gross JJ (2010). Emotion Regulation in Older Age. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(6), 352–357. 10.1177/0963721410388395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BR, Ponesse JS, Schachar RJ, Logan GD, & Tannock R (1999). Development of inhibitory control across the life span. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 205–213. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Enge S, Kräplin A, Krönke K, Bühringer G, Smolka MN, & Goschke T (2021). Chronic stress, executive functioning, and real‐life self‐control: An experience sampling study. Journal of Personality, 89(3), 402–421. 10.1111/jopy.12587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data, materials, and code used in the manuscript can be viewed and downloaded from OSF: https://osf.io/4kf3a/