Abstract

Visible light-induced Pd catalysis has emerged as a promising subfield of photocatalysis. The hybrid nature of Pd radical species has enabled a wide array of radical-based transformations otherwise challenging or unknown via conventional Pd chemistry. In parallel to the ongoing pursuit of alternative, readily available radical precursors, notable discoveries have demonstrated that photoexcitation can alter not only oxidative addition but also other elementary steps. This Minireview highlights the recent progress in this area.

Keywords: Excited-State Reactivity, Olefins, Palladium, Photochemistry, Radical

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Since the first report by the Gevorgyan group in 2016, a tremendous progress has been made in the field of visible light-induced Pd catalysis.[1] In this new paradigm,[2–9] Pd catalyst plays a dual role by harvesting photon energy as a photocatalyst, as well as by catalyzing the bond forming/breaking events, thus, obviating the use of an exogeneous photosensitizer.[10] In contrast to the traditional ground-state Pd catalysis[11] relying on 2-electron redox events,[12] contemporary excited-state Pd chemistry usually involves single electron transfer (SET) processes, leading to novel radical transformations via the intermediacy of hybrid Pd radicals.[2–8] A majority of them involve oxidative quench of the photoexcited Pd0 with an electrophile (Figure 1A). In this mode, ‘oxidative addition’ is facilitated via an inner-sphere SET, which has low or even no activation barrier according to the computational studies by Rueping,[13] Shang,[14] and Koenigs.[15] Additionally, Arndtsen group showed that photoexcitation can also facilitate ‘reductive elimination’ via homolysis of C–Pd bond and followed by halogen atom transfer (XAT) (Figure 1B).[16] Recently, the Gevorgyan group reported various PdII–H-enabled transformations, including uncommon, chemoselective ‘hydridic’ hydropalladation driven by hydricity enhancement upon photoexcitation (Figure 1C).[17] Traditional cross-coupling reactions can also be accelerated by irradiation, though the origin remains unclear.[18] Significant development has been made in the field, in particular the exploration of various electrophiles as radical precursors (Figure 1D). Commonly used Pd sources, ligands, solvents, and bases are also briefly summarized (Figure 1E). This topic has been reviewed by several research groups;[2–8] this minireview will therefore focus on the recent advances in this emerging area accompanied with mechanistic discussion. The UV-induced transformations are not discussed herein.[19]

Figure 1.

General overview of visible light-induced Pd catalysis.

2. Desaturation

In 2016, the Gevorgyan group reported a directed desaturation of silyl ethers 1.1 to the corresponding silyl enol ethers 1.2 (Scheme 1).[1] This transformation begins with the SET from photoexcited Pd0 catalyst to substrate to produce a hybrid Pd aryl radical intermediate A, which undergoes 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) to form intermediate B. A subsequent β-H loss occurs to afford product 1.2. Meanwhile, regeneration of Pd0 from PdII by base completes the catalytic cycle. Given the paucity of literature reports on aryl radical intermediate in Pd catalysis,[20] mechanistic studies were performed to corroborate its formation. Accordingly, radical probe experiment showed that substrate 1.3 was converted exclusively to 1.4 via radical intermediate C. The absence of 1.5 and 1.6 argued against a classical 2-electron mechanism. Besides, D-labeled substrate 1.7 underwent desaturation with ≥98% deuterium incorporation at the phenyl ring, thus supporting the proposed HAT process. In addition, radical traps such as galvinoxyl and TEMPO completely shut down the reaction, further indicating the involvement of radical species. Due to the hybrid nature of intermediate B, several pathways toward 1.2 become plausible. In the first case, B can collapse to a classical closed-shell PdII intermediate B1, which upon β-hydride elimination affords the product. Alternatively, the direct formation of double bond via HAT to PdI is also feasible (B2). In addition, radical-polar crossover (RPC) and halogen atom transfer (XAT), both leading to intermediates prone to further base-mediated elimination (B3 and B4 respectively), are also possible pathways.

Scheme 1.

Desaturation of silyl ethers involving hybrid Pd aryl radical species.

This radical approach of desaturation has since then been applied to other classes of substrate, including aliphatic alcohols and amines for remote desaturation, as well as carboxylic acid derivatives for desaturation at proximal site (Scheme 2).[21–23]

Scheme 2.

Desaturation of aliphatic alcohols, amines, and carboxylic acids.

More recently, the groups of Chen and Dong reported the desaturation of amides 3.1 toward α,β-unsaturated amides 3.2 (Scheme 3).[24] Alkyl and aryl bromides (3.3 and 3.4), both of which known to react with photoexcited Pd catalyst (see below), are well tolerated. Interestingly, a series of kinetic isotope effect (KIE) studies revealed that both HAT (d-3.6-α) and β-H loss (d-3.6-β) are not the turnover-limiting step (TLS) in this transformation. The authors therefore suggested that the TLS could be the formation of aryl radical or the reduction of PdII.

Scheme 3.

Desaturation of amides via aryl radical.

In 2021, the Yu group utilized N-centered radical[25] for the remote desaturation of amide derivatives 4.1 (Scheme 4).[26] This protocol is applicable to the desaturation at the carbonyl end (4.3 and 4.4), as well as the amine end (4.5). The intermediacy of N-centered radical was established based on the formation of diene 4.7 from radical probe substrate 4.6.

Scheme 4.

Remote desaturation of amides via N-centered radical.

Later, the same group employed N-alkoxypyridinium salts 5.1 for the synthesis of alkenols 5.2 (Scheme 5).[27] In contrast to the previous reports, a radical chain mechanism was proposed for this transformation, as supported by a measured quantum yield of 82. Thus, the Pd catalyst only serves to initiate the radical chain through the initial formation of alkoxy radical A. Subsequent 1,5-HAT leads to transposed alkyl radical B, which undergoes SET with 5.1 to produce carbocation C and regenerates A to propagate the radical chain. Eventual proton loss of C furnishes product 5.2. The involvement of carbocation C rather than the respective hybrid Pd alkyl radical intermediate[21] may explain the relatively low regioselectivity in certain cases, such as 5.5.

Scheme 5.

Radical chain remote desaturation of N-alkoxypyridinium salts via O-centered radical.

3. Heck and Heck-Type Reactions

3.1. Direct Heck and Heck-Type Reactions

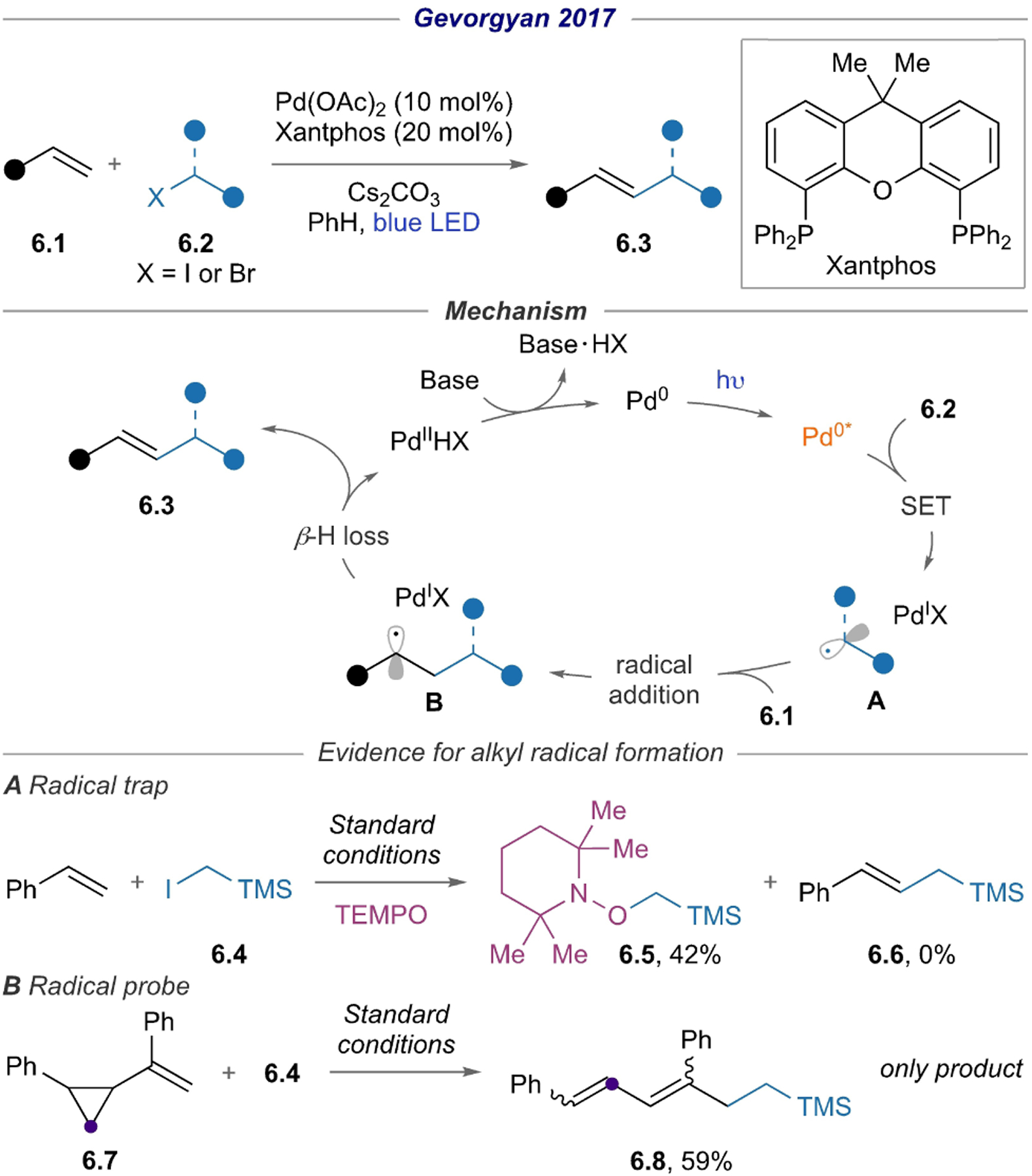

Leveraging the radical nature of hybrid Pd alkyl species, the Gevorgyan group first demonstrated that these intermediates readily undergo radical addition to styrene derivatives 6.1, thereby producing alkyl Heck products (Scheme 6).[28] The reaction conditions are notably mild compared to the previously known methods,[29–33] as reflected by the compatibility of various α-functionalized alkyl halides, as well as the excellent stereoselectivity of the products. The presence of alkyl radical was confirmed by the formation of TEMPO adduct 6.5 and radical ring-opening product 6.8.

Scheme 6.

Alkyl Heck reaction using α-functionalized alkyl halides.

Shortly after, Fu, Shang and co-workers reported the use of unactivated alkyl bromides for the same transformation (Scheme 7).[34] Likewise, radical probe studies support the involvement of alkyl radicals. A small intramolecular KIE value was obtained using substrate 7.9, arguing against XAT pathway in this case (B4, Scheme 2). Notably, X-ray photo-electron spectroscopy revealed the signals of PdII, PdI, and Pd0, providing additional evidence of the intermediacy of PdI.

Scheme 7.

Alkyl Heck reaction using unactivated alkyl bromides.

Several alkyl Heck reactions have since then been developed.[13,14.35–40] Importantly, the scope of electrophile has been extended to redox-active esters (RAEs) by the groups of Shang and Fu[36] and Glorius[37] respectively, and later to alkyl chlorides by Hong and co-workers.[40]

In addition to alkenes, the Gevorgyan group showed that oximes were also amenable to related Heck-type reaction.[41] More recently, the same group reported the analogous process with α-ester hydrazones (Scheme 8).[42] This protocol enables access to elusive E-isomers when primary and secondary alkyl electrophiles are used (8.4), while a reversal of stereochemistry was observed in case of the tertiary counterparts, presumably due to 1,3-allylic strain (8.5). Importantly, the E configuration situates the N atom on the alkyl side for intramolecular SN2, thus allowing for the synthesis of heterocycles when bishalides are employed (8.6).

Scheme 8.

Alkyl Heck-type reaction of α-ester hydrazones.

Rueping and co-workers demonstrated that imines are also viable substrates (Scheme 9).[43] In this case, stoichiometric PPh3 was employed to effect a reductive Heck-type reaction. Various α-alkylated anilines were prepared, including amino acid derivative 9.7. Notably, the products could be accessed in a three-component fashion with comparable efficiency (9.8).

Scheme 9.

Reductive alkylation of imines.

3.2. Relay Heck Reactions

Building on their experience with hybrid Pd alkyl reactivities, the Gevorgyan group achieved remote C(sp3)–H alkenylation of aliphatic alcohols via radical relay (Scheme 10).[44] This transformation involves a cascade of intramolecular HAT and subsequent Heck reaction with the transposed alkyl radical. Ligand turned out to be the key factor in this process: desaturation (10.5) was the major pathway when the previously optimal ligand L1 was used, while switching to Xantphos, which slows down β-H elimination due to a larger bite angle, effectively promoted the desired relay Heck sequence (10.4).

Scheme 10.

Radical relay alkyl Heck reaction using aliphatic alcohols.

Very recently, Chen, Yang, and co-workers employed aryl iodides as radical source for the relay α-alkenylation of amides (Scheme 11).[45] Of note, the product stereoselectivity appears to be largely substrate-dependent, and moderate E/Z ratio was obtained in some cases.

Scheme 11.

Radical relay α-alkenylation of amides.

A related transformation utilizing N-centered radical was later reported by the groups of Chen and Teng (Scheme 12).[46] This protocol is predominantly appliable to o-methylbenzamides, as the ethyl analogue was predisposed to premature desaturation (12.7).

Scheme 12.

Radical relay Heck reaction using of o-methylbenzamides.

Besides intramolecular HAT, alkyl radicals can also be generated intermolecularly for relay Heck reactions. In 2022, the Yin group employed hexabromobenzene (HBB) for the C(sp3)–H alkenylation of activated substrates (Scheme 13).[47] Only 0.3 equivalents of HBB were required, indicating that each HBB molecule can undergo multiple HAT events. As with most reactions involving aryl radical-mediated intermolecular HAT,[48] the activated substrate was used as a solvent to ensure good yields. Substrates containing multiple activated sites gave a mixture of regioisomers (13.6). The HAT step was supported by D-labeling experiment (d-13.8) and found to be the TLS based on the KIE value of 5.0.

Scheme 13.

Radical relay Heck reaction involving intermolecular HAT.

In continuation of the previous work on 1,2-spin-center shift (SCS) toward transposed alkyl radicals,[49] Ngai, Liu and co-workers reported a migratory alkyl Heck reaction for C-2 alkenylation of carbohydrates (Scheme 14).[50] Both elevated temperature (90°C) and highly diluted conditions (0.025 M) are crucial to ensure C-2 selectivity over C-1. Alkenylation preferentially occurred at the axial position, though the equatorial isomer was observed in all cases. The SCS process starts with the photoinduced formation of alkyl radical A (substituents and Pd are omitted for clarity), which readily undergoes conformational change to B due to favorable nO↔SOMO↔σ*C–O interactions. Subsequent concerted [2,3]-acyloxy rearrangement via transition state C leads to more stable transposed alkyl radical D, as supported by DFT calculations. Interestingly, primary KIE was observed in both inter- and intramolecular KIE studies using 14.8 and its deuterated analogues, in contrast to previous studies (Scheme 7).[34] More recently, the same group employed silyl enol ethers as alkene partner for the C-2 carbonylation of carbohydrates (Scheme 15).[51]

Scheme 14.

Radical relay C-2 alkenylation of carbohydrates via SCS.

Scheme 15.

C-2 carbonylation of carbohydrates.

4. Difunctionalization of Unsaturated Systems

In 2018, the Gevorgyan group reported a 1,5-HAT/atom transfer radical cyclization (ATRC) cascade of vinyl iodides 16.1 leading to iodomethyl carbocycles or heterocycles 16.2 (Scheme 16).[52] Proposed mechanism involves formation of the hybrid vinyl palladium radical A upon SET from photoexcited Pd0 to 16.1, which undergoes 1,5-HAT to generate translocated radical B. A subsequent 5-exo-trig cyclization of B leads to intermediate C, which undergoes XAT from PdII species, instead of β-hydrogen loss, to afford 16.2. A radical chain mechanism via XAT of C from another substrate molecule is unlikely due to unfavorable BDE difference between vinyl- and alkyl-iodide bonds.[53] The results of deuterium labeling experiments indicated formation of the vinyl radical species and that HAT is the TLS.

Scheme 16.

Difunctionalization via HAT/ATRC cascade involving hybrid Pd vinyl radical.

In 2022, Marchese, Lautens, and co-workers reported photoinduced ATRC reaction of aryl iodides 17.1 (Scheme 17).[54] This mild protocol tolerated functional groups sensitive under traditional Pd catalysis, such as Lewis basic (17.3), acidic protons (17.4) and can be applied to afford a variety of hetero- or carbocycles (17.3–17.5). In addition to previously mentioned SET pathway (Scheme 16), the authors proposed migratory insertion of the oxidative addition complex A′ via 2e– pathway and followed by photoinduced homolysis for the generation of hybrid Pd radical species B′. Likewise, a subsequent XAT from PdII afforded 17.2. Studies with the stoichiometric Pd0 species supported formation of the photolabile migratory insertion complex B′ (17.7). A series of mechanistic studies revealed involvement of a reversible XAT process for the C–I bond formation. First, D-labeled substrate 17.9 afforded carboiodination product 17.10 with 1:1 mixture of diastereomers, instead of diastereo enrichment expected in case of stereospecific reductive elimination.[55] Besides, when diastero-enriched 17.10 was subjected to Pd-catalyzed conditions, the diastereo enrichment was deteriorated.

Scheme 17.

ATRC cascade via reversible XAT.

Previously, two-component difunctionalization of alkenes or alkynes involving radical cyclization was reported by Yu,[56] Cheng,[57] Glorius,[58] and Koenigs.[59] In 2022, the Sharma group utilized intermolecular radical cyclization for a two-component dearomatizative difunctionalization of indoles 18.1 (Scheme 18).[60] An alkyl Heck type endgame afforded alkenylated tetracyclic indolines (18.4–18.6) with high diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 18.

Difunctionalization via dearomatizative radical cyclization/alkenylation cascade.

Recently, the Wu group employed similar type of cascade difunctionalization (19.3→19.4) for synthesis of polyarylfurans 19.6–19.8 (Scheme 19).[61]

Scheme 19.

Synthesis of polyarylfuran skeletons involving tandem difunctionalization.

Cascade difunctionalization involving intermolecular hybrid Pd alkyl radical addition to electron-deficient alkenes (20.1) followed by cyclization provides access to various heterocycles 20.3 (Scheme 20). In 2021, the Zhang group reported difunctionalization of N-aryl acrylamides with alkyl bromides leading to oxindoles (20.4–20.5) or its derivatives (20.6).[62] Simultaneously, Muralirajan, Rueping and co-workers employed alkyl chlorides and bromides to afford oxindole derivatives (20.7–20.8).[63] Later, the Singh group reported a difunctionalization of N-heteroaryl acrylamides (20.9) as well as an alkylation of quinoxalinone derivatives (20.10).[64]

Scheme 20.

Difunctionalization via intermolecular radical addition/cyclization cascade.

In 2022, the Koenigs group reported a cascade 1,1-difunctionalization of isocyanides (21.1) with alkyl iodides (21.2) to afford phenanthridines (21.4–21.6) (Scheme 21).[15] Radical nature of this transformation was supported by the statistical D-loss observed in the product (21.7) in the cyclization of imidoyl radical A to either side of the deuterated aromatic ring.[65]

Scheme 21.

Cascade 1,1-difunctionalization of isocyanides.

In addition to cyclization of translocated radical as mentioned before, it can be intercepted by a radical trap. In 2021, Gevorgyan group developed a three-component radical difunctionalization of vinyl (hetero)arenes 22.1 (Scheme 22).[66] A selective radical addition to 22.1, followed by trapping of the translocated radical with isocyanides 22.3 and a subsequent β-H loss of the formed imidoyl radical,[15] leads to ketenimine intermediate 22.4. The in situ treatment of 22.4 with Brønsted or Lewis acid afforded modular access to amides (22.7–22.8) or nitriles (22.9).

Scheme 22.

Three-component difunctionalization via trapping of translocated radical with isocyanides.

Later, the Koenigs group reported a three-component difunctionalization of electron-rich vinyl (hetero)arenes 23.1 via RPC of the corresponding translocated radical (Scheme 23).[67] The electron-donating groups on the vinyl arenes are crucial for the RPC step, which was supported by the DFT studies. A nucleophilic trapping with heterocycles 23.3 led to C–C and C–N bond formations (23.5–23.6). Formation of a carbocationic intermediate was supported by highly diastereoselective functionalization (23.8) using a chiral methyl ester 23.7 via a neighboring group participation of the pendant chiral ester (A).

Scheme 23.

Three-component difunctionalization via RPC of the translocated radical.

5. Cross-Coupling

5.1. C–C Bond Formations

In 2017, the Yu group disclosed a C(sp3)–H alkylation of tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) derivative 24.1 with alkyl bromide 24.2 (Scheme 24).[68] In this case, alkyl radical species A underwent radical recombination with α-amino radical intermediate C, generated via a second SET event involving PdI and THIQ derivative, followed by a facile deprotonation. Of note, analogous benzyl amines, such as N-methylbenzylamines, lack reactivity likely due to their higher oxidation potential. Radical trapping experiment with ethyl vinyl ketone supported formation of the α-amino radical intermediate.

Scheme 24.

Cross-coupling via radical recombination.

In the same report, the authors also demonstrated intraand intermolecular alkylation of heteroarenes. Later, radical cross-coupling was explored by Zhou,[69] Shang and Fu,[70] Liang and Chen,[71] Gevorgyan,[65] Hong[72] employing various coupling partners, including aryl triflates and unactivated arenes. Recently, following up with their previous work on Dowd-Beckwith ring expansion/Heck reaction cascade,[73] the Duan group reported a C(sp3)–H alkylation of THIQ derivatives 25.1 (Scheme 25).[74] Electronically different substituents including N-heteroaryl group containing THIQ derivatives (25.4) were found to be capable substrates along with a variety of cyclic and acyclic α-bromomethyl-β-keto esters (25.5–25.6). In contrast to the Yu’s mechanism involving a free radical recombination (Scheme 25), the authors proposed recombination of both alkyl radicals with PdI, followed by reductive elimination of the PdIII intermediate, which was supported by the HRMS results.

Scheme 25.

Cross-coupling via Dowd-Beckwith ring expansion.

In 2021, the Zhang group developed a defluorinative Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction involving activation of strong C–F bond of trifluoromethylarenes 26.1 (Scheme 26).[75] Various aryl boronic acids underwent cross-coupling with electron-deficient or neutral trifluoromethyl arenes (26.4–26.6). In contrast to the traditional Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction which involves direct oxidative addition, this photoinduced method involves an SET process leading to formation of the difluoromethylaryl radical B. A subsequent recombination with PdI species and reductive elimination (RE) affords 26.3. Oxidation potential of photoexcited Pd0 is calculated to be −2.76 V vs Fc+/Fc. Due the redox potential match, it is capable of reducing II–IV. However, in case of trifluoromethylarenes possessing electron withdrawing group (e.g. III), although SET is possible, an unproductive back electron transfer occurred from enolate-stabilized radicals instead of C–F bond cleavage. Formation of radical B was supported by the results of radical probe experiment with 26.8.

Scheme 26.

Defluorinative Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of trifluoromethylarenes.

Later, Murakami, Miura and co-workers reported a Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of α-chloroacetyl derivatives 27.1 to afford α-(hetero)aryl-acetates or -acetamides (27.4–27.6) (Scheme 27).[76] Likewise, this method also involves a photoinduced SET bypassing a direct oxidative addition.

Scheme 27.

Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of α-chloroacetyl compounds.

5.2. C–X Bond Formations

In 2020, the Arndtsen group demonstrated that a broad range of organic halides and nucleophiles can be employed in carbonylative cross-coupling reaction under photoinduced Pd-catalyzed conditions (Scheme 28).[16] The authors proposed a dual role of light for the success of this transformation. First, photoexcited Pd0 undergoes SET with 28.1, leading to acyl PdII species C via carbonylation and ligand exchange. The second photoinduced event leads to homolysis of Pd–C bond thus generating acyl PdI hybrid radical species. A subsequent XAT affords acid chloride 28.3, which can be trapped by nucleophile in situ or ex situ to deliver 28.4. The crucial role of light in the reductive elimination via acyl radical formation was supported by the control experiments with complex 28.6.

Scheme 28.

Carbonylative coupling of organic halides.

Later, the same group developed a carbonylative coupling method to furnish acyl fluorides 29.2, which can be trapped with nucleophiles in one-pot fashion (Scheme 29).[77] Contrary to acyl chlorides, which are often more susceptible to SET than the corresponding halides, acyl fluoride did not undergo SET. Thus, this method represents a more general way to access acyl halides and does not require an in situ trap to drive the reaction forward. Densely functionalized alkyl and (hetero)aryl halides (29.5–29.7) can be employed in this transformation. In contrast to the previous report, in this case, light does not influence the reductive elimination step.

Scheme 29.

Carbonylative coupling of organic halides to acyl fluoride.

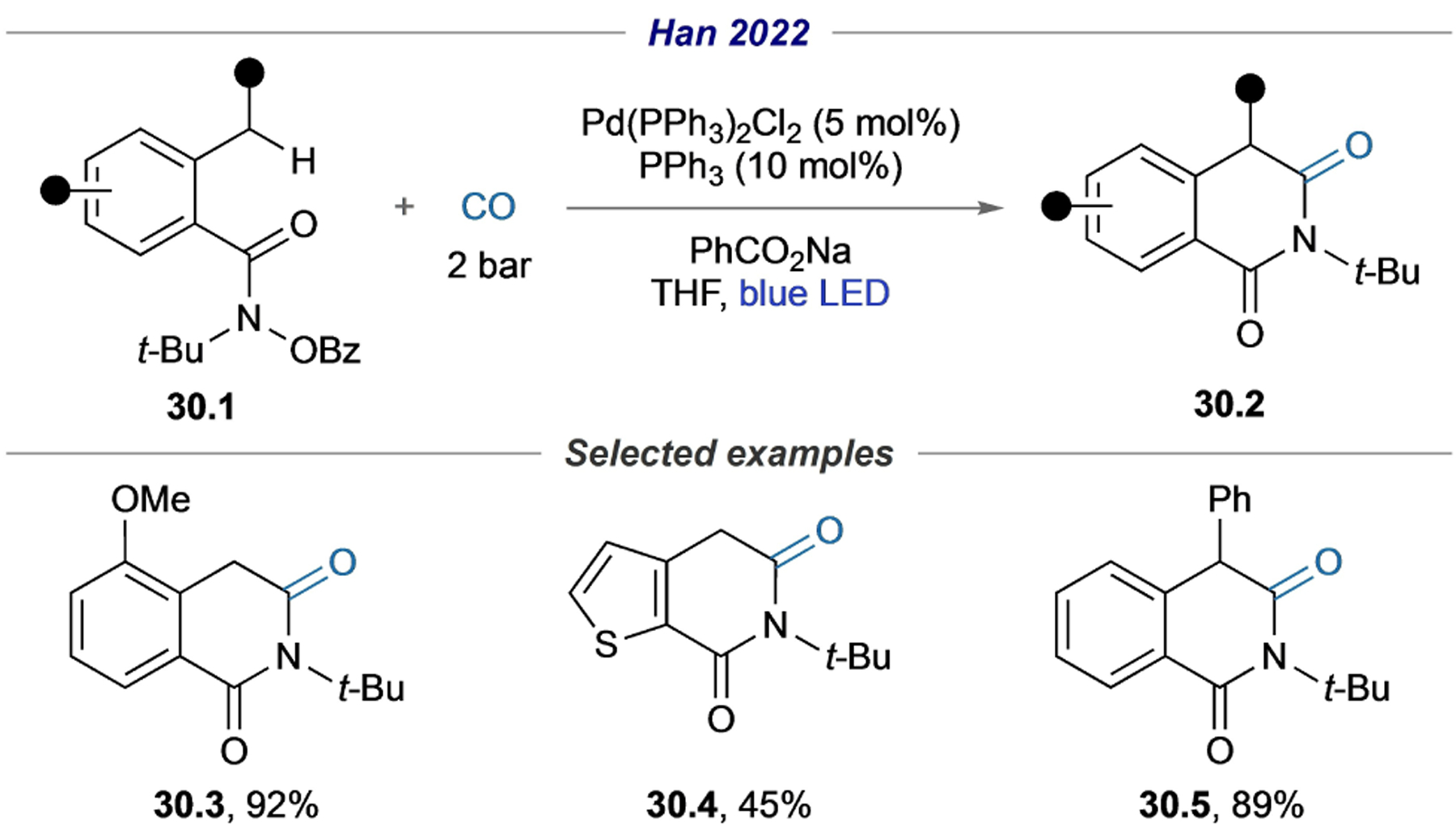

Recently, the Han group employed intramolecular radical translocation by N-center radical[25,26] in a remote C–H carbonylation/annulation cascade (Scheme 30).[78] Various homophthalimides were found to be capable substrates in this transformation (30.3–30.5).

Scheme 30.

Remote carbonylative coupling via radical translocation by N-centered radical.

6. Allylic Functionalization via π-Allyl Pd Complexes

6.1. Reactions with Dienes

In 2020, the Glorius group demonstrated that synthetically versatile π-allyl Pd intermediates[79,80] could be accessed from 1,3-dienes and RAEs (Scheme 31).[81] In this case, alkyl radical addition to diene leads to hybrid Pd allyl species A, which then collapses into classical π-allyl Pd intermediate B upon RPC. A subsequent nucleophilic substitution with phthalimide anion, previously formed along with alkyl radical, affords 1,4-difunctionalized products 31.3. The same group then extended this methodology to a three-component reaction using alkyl bromides and various C-, N-, O-, and S-nucleophiles in the follow-up studies.[82,83]

Scheme 31.

1,4-Carboamination of dienes via radical generation of π-allyl Pd species.

Simultaneously, the Gevorgyan group described a similar transformation leading to 1,2-carbofunctionalization products (Scheme 32).[84] AgNTf2 was found to be a crucial additive, without which a substantial formation of side product 32.6 was observed, likely arising from recombination of allyl radicals. It was also found that π-allyl Pd complexes bearing iodide or triflimide displayed different reactivities toward TEMPO. For the former, both visible light and thermally-induced conditions led to appreciable amounts of adduct 32.9. In contrast, complex 32.8 was only reactive upon irradiation. These results suggest that triflimide stabilizes π-allyl Pd species from undesirable homolysis, thereby facilitating the nucleophilic substitution step.

Scheme 32.

Three-component 1,2-carbofunctionalization of dienes.

Such combination of excited and ground state reactivity of palladium has been further explored by other research groups. In 2022, Yang, Xiang and co-workers employed bromodifluoroacetamides and sulfinates or cyclic amines for the 1,4-difunctionalization of dienes (Scheme 33).[85] The same group also developed an annulative protocol for synthesis of N-heterocycles using amine-tethered alkyl halides.[86] Meanwhile, the Li and Cui groups reported perfluoroalkylamination using perfluoroalkyl iodides and amines.[87] Interestingly, the authors observed a regioselectivity switch when more electron-withdrawing perfluoroalkyl iodides were used (33.9 vs 33.10). Combining radical relay strategy via HAT to N-centered radical (cf. Scheme 4), Gong, Han and co-workers developed carboacyloxylation reaction using hydroxamides as bifunctional reactants.[88]

Scheme 33.

Carbofunctionalization of 1,3-dienes.

In 2022, Zi, Zhang and co-workers achieved synergistic Pd/Cu-catalyzed 1,4-bisalkylation of butadiene (Scheme 34).[89] This protocol features a chiral Cu catalyst capable of activating aldimine pronucleophiles, thereby furnishing valuable enantioenriched α-amino esters. While an (S)-BINAP-based Pd catalyst was found to be optimal, the authors showed that using the rac-BINAP version only led to a slight decrease of enantioselectivity, thus indicating that chirality is largely controlled by the chiral Cu complex.

Scheme 34.

Synergistic Pd/Cu-catalyzed enantioselective 1,4-bisalkylation of butadiene.

6.2. Reactions with Simple Alkenes

While it has been established that π-allyl Pd intermediates are accessible via allylic C–H activation of alkenes with a PdII catalyst,[79,80] this approach is chiefly limited to unhindered α-olefins. Besides, aliphatic amines can be challenging nucleophiles due deactivation of the Lewis acidic PdII complexes.[90,91] In 2022, the Gevorgyan group accomplished allylic C–H amination of internal alkenes with aliphatic amines via a distinct Pd(0/I/II) manifold (Scheme 35).[92] In this case, the allylic C–H bond is activated by means of intermolecular HAT to aryl radical, formed via single electron reduction of aryl bromide 35.4. A subsequent RPC with PdI leads to multi-substituted π-allyl Pd intermediate A. As such, the aryl bromide serves as a mild oxidant for this transformation, which is unorthodox in Pd catalysis. This protocol works with electronically diverse alkenes, including Michael acceptors bearing a pendant aliphatic amine unit (35.5). Site-selective amination could also be achieved in case of alkenes possessing multiple allylic C–H sites (35.6). In addition, chelating diamines are also compatible nucleophiles (35.7). Notably, diastereo- and enantioselective processes were achieved by switching Xantphos to chiral BINAP ligands, representing the only example of Pd photocatalysis where the Pd complex is also responsible for asymmetric induction.

Scheme 35.

Allylic C–H amination of internal alkenes with aliphatic amines.

7. Hydroalkenylation

In 2022, the Gevorgyan group disclosed a novel Brønsted acid-assisted hydroalkenylation of diazo compounds 36.1 and N-tosylhydrazones 36.2 (Scheme 36).[93] In line with previously discussed alkyl Heck-type transformations,[28,34,35] it involves formation of the alkyl PdI hybrid radical intermediate C, which may form via several plausible pathways, including 1,2-hydride shift of PdII-carbene intermediate A formed upon denitrogenative reaction of 36.1 with PdIIH species, followed by photoinduced homolysis of C–Pd bond. Alternatively, intermediate C could be generated via an SET to diazonium salt D or a proton coupled electron transfer (PCET) to 36.1. A series of mechanistic studies supported radical nature of the transformation, including the cyclopropyl ring opening of 36.8 via E. D-labeling studies supported HX to be the sole source of hydrogen for the formation of PdIIH species.

Scheme 36.

Brønsted acid-assisted hydroalkenylation of diazo compounds.

Later, the same group reported PdIIH-enabled hydroalkenylation of strained molecules, such as bicyclo-[1.1.0]butanes (BCBs) 37.1 and gem-difluorocyclopropenes 37.2 toward alkenylated cycloalkanes 37.4 and 37.5. A highly diastereoselective rearrangement of 37.5. to 37.6 has also been demonstrated (Scheme 37).[94] The key conceptual highlight of this work was the merger of the traditional two-electron hydropalladation step of strained systems (37.1→A, 37.2→B) with the contemporary one-electron photoinduced hybrid PdI radical (C, D) chemistry. Involvement of the PdIIH species was corroborated by a series of mechanistic studies. First, the in situ formation of PdIIH species was supported by 1H NMR studies, and by smooth hydropalladation reactions of independently synthesized (PPh3)2- (Cl)PdH species. The C–Pd bond homolysis was validated by the reduction of 37.14 in the absence of a vinyl arene. This reaction afforded a diastereomeric mixture of 37.15 via intermolecular HAT of the radical intermediate E, thus opposing an alternative path involving protodepalladation,[95] which would selectively produce the cis-product.

Scheme 37.

PdIIH-enabled hydroalkenylation of strained molecules.

Recently, the Gevorgyan group disclosed an unusual head-to-tail hydroalkenylation of electron-deficient alkenes 38.1 (Scheme 38).[17] This chemo- and regioselective method worked with a wide range of alkenes (38.4–38.5) and allowed for highly challenging cross-dimerization of vinyl (hetero)arenes (38.6). Mechanistically, this method showcased a switch from the conventional protic hydropalladation (A) to a hydridic hydropalladation (B) enabled by the enhanced excited-state hydricity[96] of PdIIH species. In line with Gevorgyan’s previous work,[93] photoinduced homolysis of B generates electrophilic alkyl radical C, which upon trapping with relatively electron-rich alkene 38.2 leads to alkyl Heck type product 38.3. Mechanistic studies supported the enhanced hydricity of the photoexcited PdH species, which led to the switch of the chemoselectivity of the hydropalladation step. Thus, the control experiments with butyl acrylate and styrene, as well as with electron-deficient (38.9) and electron-rich (38.10) vinyl arenes exhibited a dramatic difference of the hydropalladation chemoselectivity between photoinduced and dark conditions. This was further supported by a striking rate enhancement of hydride transfer (38.14→38.15) under photoinduced conditions.

Scheme 38.

PdIIH-enabled head-to-tail hydroalkenylation of alkenes.

8. Summary and Outlook

As can be seen from this Minireview, in the area of hybrid Pd-radical chemistry, a continuous effort has been made toward the development of new radical precursors, as well as novel transformations such as allylic C–H amination and hydroalkenylation of alkenes. Notably, it has been established that photoexcitation can play a role at different stages of a catalytic cycle, thereby facilitating various elementary steps, including oxidative addition, reductive elimination, and migratory insertion. Furthermore, stereoselective process has been achieved recently, affirming the viability of combining excited-state radical chemistry and ground state asymmetric transformations with a single Pd catalyst. It is believed that such versatility of excited-state Pd catalysis will in turn fuel the design of other novel catalytic transformations and the search of other fundamental processes that can be altered upon irradiation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM120281), National Science Foundation (CHE-2246075), and Welch Foundation (Chair, AT-0041) for financial support.

Biographies

Sumon Sarkar received his BSc from Jadavpur University, India and MSc from Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur. In 2017, he joined the Gevorgyan group at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) as a PhD student and later moved to the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD). His research work has focused on the development of novel photoinduced methodologies.

Kelvin Pak Shing Cheung received his BSc and MPhil in chemistry from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In 2018, he joined the Gevorgyan group at UIC as a PhD student, and later at UTD. His research revolves around the development of visible light-induced transition metal-catalyzed transformations.

Vladimir Gevorgyan received his PhD from the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis. After postdoctoral research at Tohoku University, Japan with Prof. Y. Yamamoto as a JSPS and then Ciba Geigy International Postdoctoral Fellow, in 1996, he joined the faculty position there. In 1999, Vladimir moved to USA to join UIC (Associate Professor, 1999; Professor, 2003; LAS Distinguished Professor, 2012). In 2019, he joined UTD as a Robert. A. Welch Distinguished Chair in Chemistry, with a secondary appointment at the UT Southwestern Medical Center. His group is interested in the development of novel synthetic methods.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- [1].Parasram M, Chuentragool P, Sarkar D, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6340–6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Parasram M, Gevorgyan V, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 6227–6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kancherla R, Muralirajan K, Sagadevan A, Rueping M, Trends Chem 2019, 1, 510–523. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cheng WM, Shang R, ACS Catal 2020, 10, 9170–9196. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chuentragool P, Kurandina D, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 11586–11598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhou WJ, Cao GM, Zhang ZP, Yu DG, Chem. Lett 2019, 48, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cheung KPS, Sarkar S, Gevorgyan V, Chem. Rev 2022, 122, 1543–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jardim GAM, Dantas JA, Barboza AA, Paixão MW, Ferreira MAB, Synthesis 2022, 54, 4629–4645. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pei C, Empel C, Koenigs RM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, 61, e202201743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].For an example of visible light-induced Pd-catalyzed reaction with a photosensitizer, see:; Kalyani D, McMurtrey KB, Neufeldt SR, Sanford MS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 18566–18569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].For a selected example, see:; de Meijere A, Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis (Ed.: Negishi E), Wiley, New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [12].For an example of ground-state Pd catalysis involving 1e-process, see:; Powers DC, Ritter T, Nat. Chem 2009, 1, 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kancherla R, Muralirajan K, Maity B, Zhu C, Krach PE, Cavallo L, Rueping M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 3412–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhao B, Shang R, Wang G-Z, Wang S, Chen H, Fu Y, ACS Catal 2020, 10, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pei C, Yang Z, Koenigs RM, Tetrahedron 2022, 123, 132939. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Torres GM, Liu Y, Arndtsen BA, Science 2020, 368, 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sarkar S, Ghosh S, Kurandina D, Noffel Y, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 12224–12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].For a selected example, see:; Abdiaj I, Huck L, Mateo JM, de la Hoz A, Gomez MV, Diaz-Ortiz A, Alcazar J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 13231–13236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sumino S, Fusano A, Fukuyama T, Ryu I, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 1563–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Manolikakes G, Knochel P, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Parasram M, Chuentragool P, Wang Y, Shi Y, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 14857–14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chuentragool P, Parasram M, Shi Y, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 2465–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cheng WM, Shang R, Fu Y, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang S, Fan H, Xie L, Dong G, Chen M, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 6460–6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xing W-L, Shang R, Wang G-Z, Fu Y, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 14291–14294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jin W, Yu S, Org. Lett 2021, 23, 6931–6935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jin W, Yu S, J. Org. Chem 2022, 87, 14715–14722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kurandina D, Parasram M, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 14212–14216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Firmansjah L, Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 11340–11341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bloome KS, Alexanian EJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12823–12825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McMahon CM, Alexanian EJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 5974–5977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zou Y, Zhou JS, Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 3725–3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Parasram M, Iaroshenko VO, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 17926–17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang G-Z, Shang R, Cheng W-M, Fu Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 18307–18312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kurandina D, Rivas M, Radzhabov M, Gevorgyan V, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang GZ, Shang Y Fu R, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Koy M, Sandfort F, Tlahuext-Aca A, Quach L, Daniliuc CG, Glorius F, Chem. Eur. J 2018, 24, 4552–4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Adamik R, Földesi T, Novák Z, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 8091–8095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li M, Qiu YF, Wang CT, Li XS, Wei WX, Wang YZ, Bao QF, Ding YN, Shi WY, Liang YM, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 6288–6293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee GS, Kim D, Hong SH, Nat. Commun 2021, 12, 991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kvasovs N, Iziumchenko V, Palchykov V, Gevorgyan V, ACS Catal 2021, 11, 3749–3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kvasovs N, Gevorgyan V, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 4176–4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kancherla R, Muralirajan K, Rueping M, Chem. Sci 2022, 13, 8583–8589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chuentragool P, Yadagir D, Morita T, Sarkar S, Parasram M, Wang Y, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 1794–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Du Y-J, Sheng X-X, Li J-H, Chen J-M, Yang S, Chen M, Chem. Sci 2023, 14, 3580–3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sheng X-X, Du Y-J, Li J-H, Teng Q-Q, Chen M, Org. Lett 2023, 25, 3664–3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen L, Jiang K, Zeng G, Yin B, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 9071–9075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sarkar S, Cheung KPS, Gevorgyan V, Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 12974–12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhao G, Yao W, Mauro JN, Ngai M-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 1728–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yao W, Zhao G, Wu Y, Zhou L, Mukherjee U, Liu P, Ngai M-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 3353–3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhao G, Mukherjee U, Zhou L, Wu Y, Yao W, Mauro JN, Liu P, Ngai M-Y, Chem. Sci 2022, 13, 6276–6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ratushnyy M, Parasram M, Wang Y, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 2712–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Blanksby SJ, Ellison GB, Acc. Chem. Res 2003, 36, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Marchese AD, Durant AG, Reid CM, Jans C, Arora R, Lautens M, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 20554–20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Liu H, Li C, Qiu D, Tong X, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 6187–6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sun L, Ye JH, Zhou WJ, Zeng X, Yu DG, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 3049–3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sun S, Zhou C, Yu JT, Cheng J, Org. Lett 2019, 21, 6579–6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Koy M, Bellotti P, Katzenburg F, Daniliuc CG, Glorius F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 2375–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Yang Z, Koenigs RM, Chem. Eur. J 2021, 27, 3694–3699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chen S, Van Meervelt L, Van der Eycken EV, Sharma UK, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 1213–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Li Y, Zhang S-Y, Yan X-L, Zhu J, Luo K, Wu L, Org. Lett 2023, 25, 4720–4724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Du J, Wang X, Wang H, Wei J, Huang X, Song J, Zhang J, Org. Lett 2021, 23, 5631–5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Muralirajan K, Kancherla R, Gimnkhan A, Rueping M, Org. Lett 2021, 23, 6905–6910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Upreti GC, Singh T, Khanna K, Singh A, J. Org. Chem 2023, 88, 4422–4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ratushnyy M, Kvasovs N, Sarkar S, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 10316–10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Jia X, Zhang Z, Gevorgyan V, ACS Catal 2021, 11, 13217–13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Fang H, Empel C, Atodiresei I, Koenigs RM, ACS Catal 2023, 13, 6445–6451. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zhou W-J, Cao G-M, Shen G, Zhu X-Y, Gui Y-Y, Ye J-H, Sun L, Liao L-L, Li J, Yu D-G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 15683–15687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Jiao Z, Lim LH, Hirao H, Zhou JS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6294–6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wang GZ, Shang R, Fu Y, Synthesis 2018, 50, 2908–2914. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zhou ZZ, Zhao JH, Gou XY, Chen XM, Liang YM, Org. Chem. Front 2019, 6, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kim D, Lee GS, Kim D, Hong SH, Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Chen L, Guo L-N, Liu S, Liu L, Duan XH, Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 1791–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Xin H, Guo L-N, Yang M, Guan C, Yuan Z-H, Duan X-H, Org. Chem. Front 2023, 10, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Luo Y-C, Tong F-F, Zhang Y, He C-Y, Zhang X, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 13971–13979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Oku N, Murakami M, Miura T, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 1616–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Liu Y, Zhou C, Jiang M, Arndtsen BA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 9413–9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ding W-W, Zhou Y, Song S, Han Z-Y, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 7350–7354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pàmies O, Margalef J, Cañellas S, James J, Judge E, Guiry PJ, Moberg C, Bäckvall J-E, Pfaltz A, Pericàs MA, Diéguez M, Chem. Rev 2021, 121, 4373–4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Fernandes RA, Nallasivam JL, Org. Biomol. Chem 2019, 17, 8647–8672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Huang H-M, Koy M, Serrano E, Pflüger PM, Schwarz JL, Glorius F, Nat. Catal 2020, 3, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- [82].Huang H-M, Bellotti P, Pflüger PM, Schwarz JL, Heidrich B, Glorius F, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 10173–10183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Bellotti P, Koy M, Gutheil C, Heuvel S, Glorius F, Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 1810–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Cheung KPS, Kurandina D, Yata T, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 9932–9937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Liu Z-L, Ye Z-P, Chen Y-X, Zheng Y, Xie Z-Z, Guan J-P, Xiao J-A, Chen K, Xiang H-Y, Yang H, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 924–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Zheng Y, Lu W, Xie Z, Che K, Xiang H, Yang H, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 5407–5411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Fu C, Zhang Z, Li Y, Gao D, Cui Z-N, Li Z, Chem. Commun 2022, 58, 5614–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ruan X-Y, Zhang T, Li W-A, Yin Y-Z, Hong Z-Y, Gong L-Z, Sci. China Chem 2022, 65, 863–869. [Google Scholar]

- [89].Yu H, Zhang Q, Zi W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, 61, e202208411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Ali SZ, Budaitis BG, Fontaine DFA, Pace AL, Garwin JA, White MC, Science 2022, 376, 276–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Jin Y, Jing Y, Li C, Li M, Wu W, Ke Z, Jiang H, Nat. Chem 2022, 14, 1118–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Cheung KPS, Fang J, Mukherjee K, Mihranyan A, Gevorgyan V, Science 2022, 378, 1207–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Zhang Z, Kvasovs N, Dubrovina A, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, 61, e202110924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Zhang Z, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 20875–20883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].O’Duill ML, Engle KM, Synthesis 2018, 50, 4699–4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].For enhancement of hydricity of Ir–H complexes, see:; Barrett SM, Pitman CL, Walden AG, Miller AJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14718–14721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.