Abstract

Objective.

HER2 mutations are associated with poor prognosis and are detected in 3–6% of cervical cancers. Neratinib, an irreversible pan-HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor, had activity in several HER2-mutant cancer types in the phase 2 SUMMIT basket study. We present updated and final results from the cervical cancer cohort of SUMMIT.

Methods.

Eligible patients had HER2-mutant, metastatic or recurrent cervical cancer progressing after platinum-based treatment for advanced/recurrent disease. Patients received neratinib 240 mg/day; loperamide was mandatory during cycle 1. Confirmed objective response rate (ORR) was the primary endpoint. Duration of response (DoR), clinical benefit rate (CBR), progression-free survival (PFS), and safety were secondary endpoints.

Results.

Twenty-two patients were enrolled; 18 (81.8%) had endocervical adenocarcinoma; median two prior systemic chemotherapy regimens (range 1–4). The most common HER2 variant was S310F/Y mutation (n=13; 59.1%). Four patients had confirmed partial responses (ORR 18.2%; 95% CI 5.2–40.3); 6 had stable disease ≥16 weeks (CBR 45.5%; 95% CI 24.4–67.8). Median DoR was 7.6 months (95% CI 5.6, 12.3). Median PFS was 5.1 months (95% CI 1.7–7.2). All-grade diarrhea (90.9%), nausea (54.5%), and constipation (54.5%) were the most common adverse events. Five patients (22.7%) reported grade 3 diarrhea. There were no grade 4 adverse events, no diarrhea-related treatment discontinuations, and two grade 5 adverse events, unrelated to neratinib: dyspnea (n=1) and embolism (n=1).

Conclusions.

Neratinib resulted in durable responses and disease control in patients with HER2-mutant metastatic/recurrent cervical cancer in SUMMIT. These findings support next-generation sequencing and tailored therapy for select patients with advanced cervical cancer. All responses occurred in patients with endocervical adenocarcinoma. Further assessment of neratinib in this setting is warranted.

Trial registration number.

NCT01953926 (ClinicalTrials.gov), 2013-002872-42 (EudraCT).

Keywords: Cervical cancer, HER2 mutation, Neratinib, Clinical trial, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

1. Introduction

The treatment of recurrent and metastatic cervical cancer remains an ongoing therapeutic challenge. In 2021, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy, with or without bevacizumab, as first-line treatment for patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer whose tumors have a PD-L1 combined positive score ≥1 [1]. This is now the standard first-line systemic treatment for persistent, recurrent, and metastatic cervical cancer. Tisotumab vedotin-tftv, an antibody–drug conjugate targeting tissue factor (CD142), was also granted accelerated approval in 2021 for the treatment of patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer whose disease had progressed on or after chemotherapy [2]. Furthermore, cemiplimab was approved by the EMA for use after platinum failure, irrespective of PD-L1 expression [3]. Although these new treatments have expanded the therapeutic options available to patients with advanced cervical cancer, drug resistance remains a major clinical challenge and response rates to single-agent chemotherapy are low. There is thus an urgent need for novel treatment approaches for this patient population.

Somatic HER2 mutations have been identified in a variety of solid tumors including bladder, biliary tract, breast, lung, and cervical cancers [4, 5]. HER2 mutations, which appear to be associated with poor prognosis, are present in 3–6% of cervical cancers [6, 7], and may be inhibited by some HER2-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Neratinib is an irreversible, pan-HER TKI that has been approved by the United States FDA for the treatment of patients with early-stage or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer [8–10]. Neratinib has demonstrated the ability to inhibit cell growth and tumor proliferation of HER2-mutant cell lines, xenograft, and patient-derived xenograft models, including HER2-mutant cervical cancer cell line and xenograft models [7, 11–14].

The phase 2 SUMMIT basket study evaluated the efficacy and safety of neratinib in patients whose tumors harbor somatic HER2 mutations [4]. SUMMIT included patients with a variety of solid tumors, including cervical cancers. We previously reported interim results from the cohort of patients with HER2-mutant, metastatic cervical cancer [15]. Here, we present the final results from the expanded cohort of cervical cancer patients with HER2 mutations who were treated with neratinib.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design and oversight

The open-label, multicohort, multi-tumor, phase 2, SUMMIT basket trial accrued patients at 57 centers internationally (NCT01953926; EudraCT 2013-002872-42). The study has been described in detail previously [4]. In brief, eligible patients received oral neratinib 240 mg once daily on a continuous basis, with or without other agents depending on the tumor cohort. Loperamide prophylaxis was mandatory during cycle 1 (12 mg/day on days 1–14; 8 mg/day on days 15–28) and as needed thereafter (but not exceeding 16 mg/day). Patients were treated until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent.

SUMMIT included patients with a range of solid tumors, including bladder, breast, biliary tract, cervical, colorectal, endometrial, lung, ovarian, and salivary tumors. Patients in the cervical cancer cohort, which is now complete, were women ≥18 years of age with histologically confirmed recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer for whom no curative treatment existed and with documented evidence of a somatic, activating HER2 mutation as reported by any Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified (or regionally equivalent) tissue- or plasma-based sequencing assay. Patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, and adequate hematopoietic, hepatic, kidney, and cardiac function (defined as left ventricular ejection fraction ≥50%). No prior therapy with HER2-directed TKIs was allowed, and radiotherapy must have been completed >14 days before treatment initiation. Patients with treated and/or asymptomatic brain metastases were eligible.

The SUMMIT study was conducted in compliance with the principles of good clinical practice and in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. SUMMIT was approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study site. All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

2.2. Assessments

Tumor response was assessed every 8 weeks by investigators using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST; version 1.1) [16]. If the patient did not have measurable disease by RECIST, measurement using Positron Emission Tomography Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST version 1.0) [17] was permitted. The primary endpoint was confirmed objective response rate (ORR). Secondary endpoints included clinical benefit rate (CBR), duration of response (DoR), progression-free survival (PFS), and safety. Adverse events were classified according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0) and monitored from the first administration until 28 days after study drug was discontinued.

Patients were requested to provide archival or pre-treatment tumor tissue when available. For those who provided tissue, central retrospective next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed using Memorial Sloan Kettering Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) assay [18].

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) samples were obtained from a single patient at the following timepoints: screening, cycles 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13. These samples were analyzed using MSK Analysis of Circulating cfDNA to Examine Somatic Status (MSK-ACCESS), a high-depth NGS assay with molecular barcoding technology for the detection of very low frequency somatic alterations in 129 genes. MSK-ACCESS data were demultiplexed using BCL2FASTQ (version 2.1.9 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), unique molecular barcodes were trimmed with Trim Galore (version 0.2.5) and Marianas (https://github.com/mskcc/Marianas), and read pairs were aligned to the human GRCh37 reference genome with further post-processing, as previously described [19]. Variant calling was performed in a matched tumor-informed manner (“genotyping”) using GetBaseCountMultiSample (https://github.com/mskcc/GetBaseCountsMultiSample), and required at least one duplex consensus read to call a somatic single nucleotide variant at a site known to be altered in the tumor sample from a given patient at the time of diagnosis [19].

2.3. Statistical analyses

The data cut-off, which is the final database lock, for this report was January 4, 2023. The RECIST efficacy-evaluable set included patients with RECIST-measurable disease at baseline plus at least one post-baseline tumor assessment per RECIST, or who discontinued treatment before the first scheduled post-baseline tumor assessment. If a patient was followed using PERCIST only, PERCIST data were used for all appropriate analyses. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate PFS. The Clopper–Pearson method was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for ORR and CBR. The safety analysis set included all patients who received at least one dose of neratinib. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient demographics, characteristics, and tumor mutation spectrum

Twenty-two patients with histologically confirmed metastatic cervical cancer were enrolled and comprised the safety analysis set. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients had a median age of 55 years (range 29–74 years), most had endocervical adenocarcinoma (81.8%), and an ECOG performance status of 1 (68.2%); patients had a median of two prior systemic chemotherapy regimens (range 1–4). Further details on patient/disease characteristics and previous treatments are provided in Table S1.

Table 1.

Demographics and patient characteristics - safety analysis cohort

| HER2-mutant cervical cohort (N = 22) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Median age (range), years | 55 (29–74) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 15 (68.2) |

| Asian | 1 (4.5) |

| Black | 1 (4.5) |

| Unknown/other | 5 (22.7) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 7 (31.8) |

| 1 | 15 (68.2) |

| FIGO stage at diagnosis, n (%)a | |

| I | 7 (31.8) |

| II | 5 (22.7) |

| III | 2 (9.1) |

| IV | 6 (27.3) |

| Missing | 2 (9.1) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 18 (81.8) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4 (18.2) |

| HPV status, n (%) | |

| Positive | 13 (59.1) |

| Negative | 2 (9.1) |

| Unknown/missing | 7 (31.8) |

| Previous therapeutic interventionsb, n (%) | |

| Platinum-based | 22 (100) |

| Bevacizumab | 16 (72.7) |

| Pembrolizumab | 4 (18.2) |

| Prior radiotherapyd, n (%) | 17 (77.3) |

| Prior surgery, n (%) | 14 (63.6) |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HPV: human papillomavirus.

2018 criteria.

A complete list of previous systemic therapies is available in Supplementary Table S1.

Three patients (13.6%) had radiotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting, eight (36.4%) had radiotherapy in the adjuvant setting, and six (27.3%) had palliative radiotherapy. The setting for radiotherapy was unknown for three patients.

All patients had previously been treated with platinum-based chemotherapy; 16 (72.7%) had previously received bevacizumab and four (18.2%) had received pembrolizumab monotherapy. Patients had a median of two prior systemic chemotherapy regimens (range 1–4).

The spectrum of HER2 mutations for patients in the cervical cancer cohort is shown in Fig. 1. The most common variant was the hotspot S310F/Y mutation, which was identified in 13 patients (59.1%). Ten patients had tumors with S310F/Y as a single mutation and three had S310F/Y as one of two mutations. No co-occurring HER2 copy number amplification was detected. The spectrum of HER2 mutations in the SUMMIT cervical cancer cohort was consistent with that of patients with cervical cancer patients in American Association for Cancer Research (ACCR) Project GENIE (version 9.4) [20, 21]. PIK3CA co-mutation was observed in six patients, including an E545K helical domain mutation in one of the responding patients.

Fig 1.

Spectrum of HER2 mutations. aa: amino acids; furin-like: furin-like cysteine-rich region; GF_recept-IV: growth factor receptor domain IV; Pkinase_Tyr: protein tyrosine kinase domain; recep_L: receptor L domain.

3.2. Efficacy

Twenty patients were evaluable for efficacy by RECIST (Fig. 2A); two patients were evaluated using PERCIST only [22]. At the time of analysis, neratinib treatment was ongoing in one patient and 15 patients had died. One patient had a complete metabolic response and three had partial responses for a confirmed ORR of 18.2% (95% CI 5.2–40.3; Table 2). Six patients had stable disease lasting ≥16 weeks, for a CBR of 45.5% (95% CI 24.4–67.8; Table 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Best change in tumor size and tumor characteristics in RECIST efficacy-evaluable patients (n=20); 2 other patients not shown in part A were PERCIST evaluable only. (B) Duration of treatment and best response in all patients (n=22). *Note: extreme responder had surgical resection at week 95 and was not evaluable. Cut-off date: January 4, 2023. Co-mutation data based on central NGS when tumor tissue was provided, or by enrollment assay genomic report when not provided. ^Patient developed new lesion (progressive disease) and had no post-baseline target lesion measurement.

PERCIST: Positron-Emission Tomography Response Criteria in Solid Tumors; RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SD: stable disease.

Table 2.

Efficacy summary

|

|

Histology |

HER2 mutation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy endpoint | HER2-mutant cervical cancer cohort (n=22) | Adenocarcinoma (n=18) | Squamous cell carcinoma (n=4) | S310F or S310Y single mutation (n=10) | S310F or S310Y double mutation (n=3) | D769H or D769N (n=2) | Other kinase domain mutationa (n=2) | Transmembrane domain mutationb (n=5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Objective response, n (%) (confirmed; 95% CI) | 4 (18.2) (5.2–40.3) | 4 (22.2) (6.4–47.6) | 0 (0–60.2) | 3 (30.0) (6.7–65.2) | 1 (33.3) (0.8–90.6) | 0 (0–84.2) | 0 (0–84.2) | 0 (0–52.2) |

| CRc | 1 (4.5) | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 3 (13.6) | 3 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SD ≥16 weeks | 6 (27.3) | 6 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (40.0) |

| Median DoR, months (95% CI) | 7.6 (5.6–12.3) | 7.6 (5.6–12.3) | 0 | 9.3 (5.6–12.3) | 5.9 (NE-NE) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical benefit, n (%) | 10 (45.5) | 10 (55.6) | 0 | 4 (40.0) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (40.0) |

| CBR, % (95% CI)d | 45.5 (24.4–67.8) | 55.6 (30.8–78.5) | 0 (0–60.2) | 40.0 (12.2–73.8) | 66.7 (9.4–99.2) | 100.0 (15.8–100.0) | 0 (0–84.2) | 40.0 (5.3–85.3) |

| Median PFS, months (95% CI) | 5.1 (1.7–7.2) | 5.5 (3.7–10.9) | 1.7 (0.7–3.5) | 3.7 (0.5–14.1) | 6.5 (1.7–7.7) | 11.9 (5.5–18.3) | NE (1.7-NE) | 5.1 (1.7–7.2) |

Cut-off date: January 4, 2023.

G776V, G823E.

R678Q, V697L, E695D.

Complete metabolic response (evaluated using PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumors; no Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors-evaluable lesion).

CBR = CR + PR + SD >16 weeks.

CBR: clinical benefit rate; CI: confidence interval; CR: complete response; DoR: duration of response; NE: not estimable; ORR: objective response rate; PET: positron emission tomography; PFS: progression-free survival; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease.

All responses were observed in patients with adenocarcinoma: 10 of the 18 patients (55.6%) with cervical adenocarcinoma experienced clinical benefit, whereas none of the four patients with squamous cell carcinoma demonstrated clinical benefit. Prior treatment with bevacizumab did not appear to influence the efficacy of neratinib (Table S2).

Fig. 2B depicts tumor response and duration of treatment for each of the 22 patients. Treatment duration ranged from 1 to >74 months. Response durations for the four responders were 5.6, 5.9, 9.3, and 12.3 months and the median DoR was 7.6 months (95% CI 5.6–12.3). One patient had a prophylactic thoracoscopy with wedge resection of her single site of disease at week 95 and remained on neratinib without progression with >74 months of follow-up. Confirmed objective response was observed in three of the ten patients (30.0%) whose tumors harbored a single S310F/Y mutation, one of whom (33.3%) had S310F plus a HER2 V842I co-mutation. Long-term stable disease was observed across multiple HER2 mutation types, including two patients with a D769H/N mutation in the kinase domain and two with mutations in the transmembrane domain (V697L; R678Q). Median PFS was 5.1 months (95% CI 1.7–7.2). Six- and 12-month estimates for PFS were 38.8% (95% CI 18.8–58.5) and 19.4% (95% CI 6.1–38.3), respectively.

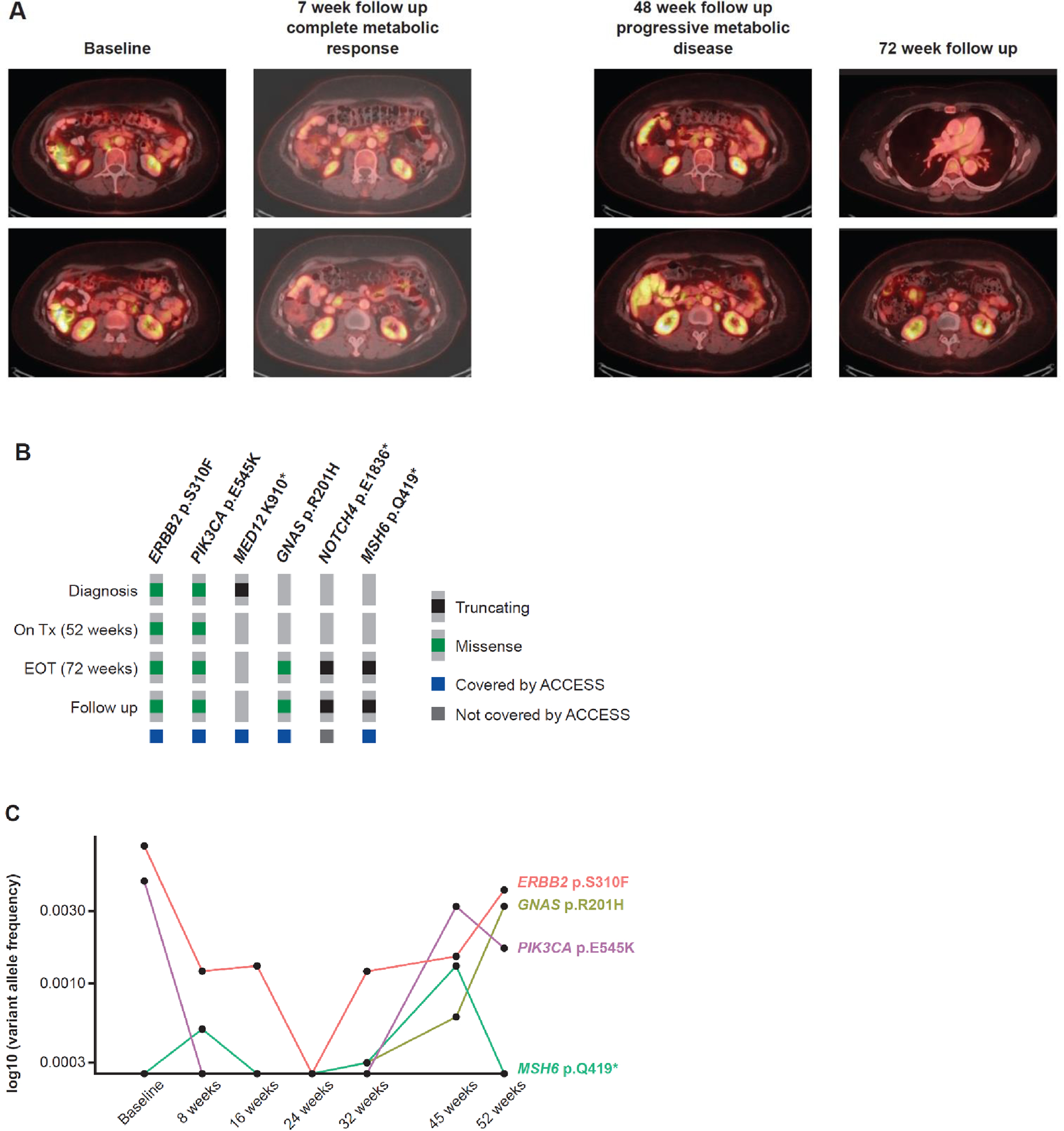

Imaging and ctDNA variant allele fractions (VAFs) for the patient who experienced complete metabolic response are depicted in Fig. 3. This patient had recurrent endocervical adenocarcinoma that harbored both a HER2 S310F and an activating PIK3CA mutation (E545K). Upon neratinib treatment, complete metabolic response was observed at the first follow-up scan. Disease progression was observed at 48 weeks (Fig. 3A) and the patient underwent radiotherapy to the area of growing disease and remained on study for an additional 5 months until new mediastinal lymphadenopathy was noted. In parallel with clinical observations, HER2 S310F and PIK3CA E545K VAFs decreased from 0.8% and 0.4% at baseline to undetectable at 24 weeks, with re-emergence coincident with clinical progression, along with an emergent oncogenic mutation in GNAS (R201H) and truncating mutations in NOTCH4 and MSH6 (Figures 3B and 3C).

Fig. 3.

(A) Scans demonstrating response to neratinib in a patient with endocervical adenocarcinoma harboring a HER2 S310F mutation, (B) DNA alterations detected from tissue biopsies taken at diagnosis, on treatment, at end of treatment, and during follow-up, and (C) longitudinal circulating tumor DNA variant allele frequencies observed throughout the course of treatment. ACCESS, Memorial Sloan Kettering Analysis of Circulating cfDNA to Examine Somatic Status; EOT: end of treatment; Tx: treatment.

3.3. Safety

The safety profile of neratinib in patients with cervical cancer was consistent with other reports of neratinib monotherapy (Table 3). Diarrhea (90.9%), constipation (54.5%), and nausea (54.5%) were the most common adverse events. There were no grade 4 diarrhea events. Two diarrhea events resulted in neratinib dose interruptions or holds. None of the diarrhea events resulted in dose reductions or discontinuation of neratinib.

Table 3.

Most common adverse events and treatment-related adverse events occurring in ≥4 patients (safety analysis set)

| Adverse event, n (%) | Any cause (N=22) | Treatment-related (N=22) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Any grade | Grade ≥3a | Any grade | Grade ≥3a | |

|

| ||||

| Patients with ≥1 adverse event | 22 (100) | 10 (45.5) | 19 (86.4) | 5 (22.7) |

| Diarrhea | 20 (90.9) | 5 (22.7)b | 18 (81.8) | 5 (22.7) |

| Constipation | 12 (54.5) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | 0 |

| Nausea | 12 (54.5) | 0 | 9 (40.9) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 9 (40.9) | 0 | 4 (18.2) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 9 (40.9) | 0 | 5 (22.7) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 8 (36.4) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (18.2) | 1 (4.5) |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (22.7) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 5 (22.7) | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 5 (22.7) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 4 (18.2) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 0 |

| Pain | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malaise | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 4 (18.2) | 0 |

| Dry skin | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | 0 |

Cut-off date: January 4, 2023.

There were no grade 4 adverse events and two grade 5 (fatal) adverse events: dyspnea (n=1) and embolism (n=1). Neither grade 5 event was reported as related to neratinib treatment.

Two diarrhea events resulted in neratinib dose interruptions or holds. None of the diarrhea events resulted in dose reductions or discontinuation of neratinib.

4. Discussion

In the phase 2 SUMMIT basket study, neratinib demonstrated acceptable toxicity and promising clinical activity in patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer whose tumors harbored activating HER2 mutations. The confirmed ORR and median PFS were 18.2% and 5.1 months, respectively; a subset of responses were durable, with median DoR of 7.6 months. Neratinib was generally well tolerated in this cohort of heavily pretreated patients and no new safety signals were identified. Diarrhea was not a treatment-limiting toxicity when neratinib was administered with antidiarrheal prophylaxis. Two grade 5 adverse events, dyspnea and embolism, were observed but considered to be unrelated to treatment with neratinib.

The recent FDA approvals of pembrolizumab [23] and dostarlimab [24] for tumor mutational burden-high/mismatch repair deficiency advanced solid tumors now provide justification for clinical tumor genomic profiling of all patients with advanced cervical cancer for whom treatment options in the advanced setting are lacking. As such, we are only just beginning to understand the clinical utility of NGS in patients with advanced cervical cancer. The identification of HER2 as a genomic driver in a subset of cervical cancers, particularly cervical adenocarcinomas, represents an important step forward in the treatment of this molecularly defined subgroup given the current therapeutic landscape. Beyond neratinib, treatment with trastuzumab deruxtecan, an antibody–drug conjugate, is associated with improved survival in patients with HER2-amplified breast [25] and gastric cancers [26]. Interim results from the phase 2 DESTINY-PanTumor-02 study demonstrated activity for this agent across tumor types, including an ORR of 50% in patients with HER2-overexpressing cervical cancer and 75% in those with immunohistochemistry 3+ tumors; trastuzumab deruxtecan is now NCCN-listed for HER2-positive advanced or recurrent cervical cancer [27].

The predominance of S310F/Y mutations in the SUMMIT cervical cancer cohort is consistent with the genomic spectrum of HER2 mutations reported in public datasets for HER2-mutant cervical cancer, including the AACR Project GENIE cohort [21]. In studies of neratinib to date, the likelihood of response appears to be influenced by both tumor lineage and HER2 mutation allele [4]. Conversely, HER2 mutations have not consistently been shown to be predictive of sensitivity to HER2 antibody therapy; however, there is growing recognition that not all hotspot mutations have similar biologic effects and clinical implications. Further understanding is limited by the lack of stratification of results based on HER2 alteration class in prior studies. Interestingly, in breast cancer, most reported HER2 mutations are clustered in the kinase domain [28, 29]. S310F/Y is a mutational hotspot localized to the extracellular domain that has been shown to promote noncovalent dimerization and subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways [30, 31], and cells expressing this mutation have demonstrated sensitivity to small-molecule HER2 kinase inhibitors and the HER2-targeted antibody trastuzumab [20, 32]. With the advent of HER2-directed antibody–drug conjugates such as trastuzumab deruxtecan, which has compelling clinical activity in HER2-mutant lung cancer [33], there may be further differentiation of HER2-directed therapies based on the specific HER2 mutation detected in individual patients. Notably, all patients with cervical cancer enrolled in SUMMIT had tumors with HER2 mutations without copy number amplification (CNA). The prevalence of HER2 CNA in cervical cancer is roughly equal to that of HER2 mutation in cervical cancer [20, 34]. Therefore, response to HER2-targeted therapies in cervical cancer patients whose tumors harbor HER2 CNA should be explored in the future. Finally, PIK3CA co-mutation did not appear to preclude response to neratinib: one patient who experienced a partial response and one patient with a metabolic complete response had tumors harboring activating PIK3CA co-mutations (Figs 2 and 3). Despite this observation, studies testing the combination of neratinib and a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor are warranted in patients with co-mutation of HER2 and PIK3CA to determine if the combination results in more complete or durable response.

Objective responses in the cervical cancer cohort of SUMMIT were limited to patients with endocervical adenocarcinoma, and no responses were observed in the four patients who had squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix. This may be a function of the small cohort size but may also reflect the fact that HER2 mutations are enriched in cervical adenocarcinoma.

Nonetheless, this correlation is hypothesis-generating and important to note, given the rising incidence of adenocarcinoma compared with squamous histology [35], particularly in patients with advanced cervical cancer [36]. Moreover, with more widespread adoption of prophylactic human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination, it is anticipated that rarer, non-HPV-associated histologies will represent a larger proportion of the cervical cancer population in the future. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma is one such histology, with approximately 15% of tumors of this histologic subtype harboring HER2 alterations [37]. Gastric-type cervical adenocarcinomas also tend to behave aggressively [38], and are thought to be less sensitive to radiotherapy [39] and chemotherapy [40] than other cervical cancer subtypes; thus, HER2-directed therapy will likely represent a particularly important approach for this subgroup of patients.

Of note, in a single patient with longitudinal ctDNA profiling, mutations present in ctDNA were consistent with those identified by tumor molecular sequencing, and the change in ctDNA VAFs mirrored radiologic response by RECIST. This result supports the routine incorporation of cfDNA collections in future cervical cancer trials, as well as the potential use of ctDNA to screen for targetable mutations in the clinical setting. This may be especially relevant for patients with cervical cancer, for whom archival tissue can be scarce.

This study had several limitations, including a small sample size and limited access to archival tissue, which affected our ability to perform additional correlative studies such as PD-L1 or HER2 IHC. The cervical cohort was a part of the larger pan-cancer SUMMIT basket study, and this was therefore a single-arm study without a comparator group. This population may also not be reflective of the broader cervical cancer population due to patient recruitment from large phase 1 study centers.

In conclusion, treatment with neratinib led to durable responses and disease control in a subset of patients with metastatic or recurrent HER2-mutant cervical cancer. The results support the routine use of tumor genomic profiling in patients with advanced or recurrent disease, particularly in those with endocervical adenocarcinoma, as a guide to therapy selection. Moreover, neratinib represents a viable treatment option for patients with cervical cancer following disease progression on prior platinum agents.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Somatic HER2 mutations occur in approximately 3–6% of cervical cancers and have been associated with poor prognosis.

Four of 22 patients with HER2-mutant cervical cancer had a confirmed response to neratinib; ten had clinical benefit.

13 patients had S310F/Y mutation in line with public datasets; all cervical cancer cohort responders had S310F/Y mutation.

Long-term stable disease was observed across multiple HER2 mutation types.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Independent Data Monitoring Committee, study investigators, research staff, clinical research organizations, and other vendors, as well as the patients who participated in the SUMMIT trial. The authors would like to acknowledge Alvin Wong (Puma Biotechnology) for thoughtful guidance and review, Bo Zhang (Puma Biotechnology) for statistical support, Jane Liang and Fauzia Ihsanullah (Puma Biotechnology) for programming support, Bethann Hromatka (Puma Biotechnology) for publications support, and Lee Miller and Deirdre Carman (Miller Medical Communications Ltd) for medical writing/editorial support.

Funding

The SUMMIT trial was sponsored by Puma Biotechnology, Inc, 10880 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 2150, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA. Puma Biotechnology Inc. also funded the provision of editorial/writing support provided by Miller Medical Communications. Claire F. Friedman and David B. Solit at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA, received support from Cycle for Survival, the Marie-Josee and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology, and P30-CA008748 for their involvement in the SUMMIT trial.

Role of the funding source

The sponsor was involved in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

C.F. Friedman: grants, non-financial support and other from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants and other from Merck, grants from AstraZeneca, grants and other from Genentech, grants from Daiichi, grants from Hotspot Therapeutics, grants from Mersana, personal fees from Aadi Biosciences/GOG Partners outside the submitted work.

D. Bello Roufai: consulting or advisory role from Lilly and Rain Oncology; support for travel and meeting attendance from GlaxoSmithKline, Rain Oncology, and AstraZeneca.

A. Tinker: honoraria (paid to the author) from GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, Merck, and AstraZeneca; travel costs from GlaxoSmithKline.

M. de Miguel: consulting fees from Syneoshealth; honoraria or speakers fees from MDS, Janssen, and Roche.

V. Gambardella: advisory Board: Boehringer; research funding: Bayer, Boehringer, Roche Institutional Funding: Genentech, Merck Serono, Roche, BeiGene, Bayer, Servier, Lilly, Novartis, Takeda, Astelas, Fibrogen, Amcure, Natera, Sierra Oncology, AstraZeneca, Medimmune, BMS, and MSD.

J. Goldman: institutional research funding from Puma Biotechnology Inc. Consultant for Puma Biotechnology, Inc.

S. Loi: research funding to institution from Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb, MSD, Puma Biotechnology, Eli Lilly, Nektar Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, and Seattle Genetics. She has received consulting fees (paid to institution) from Aduro Biotech, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche-Genentech, AstraZeneca, Silverback Therapeutics, G1 Therapeutics, Puma Biotechnology, Inc., Pfizer, Gilead Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Amunix, Tallac Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, and Bristol Meyers Squibb; payment for expert testimony (to institution) from Aduro Biotech, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche-Genentech, Astra Zeneca, Silverback Therapeutics, G1 Therapeutics, PUMA Biotechnologies, Pfizer, Gilead Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Amunix, Tallac Therapeutics, Eli Lilly and Bristol Myers Squibb; uncompensated consultant to Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Gilead Therapeutics, and Roche-Genentech.

M. E. Melisko: research funding (to institution) from OBI Pharma, KCRN Research, and Novartis; expert lecture honoraria from Puma Biotechnology, Inc.

A. Oaknin: grants to institution from AbbVie Deutschland, Advaxis, Aeterna Zenraris, Amgen, Aprea Therapeutics AB, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology Inc., Eisai Ltd, F. Hoffmann –La Roche, Immunogen Inc., MDS, Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc, PharmaMar SA, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Tesaro Inc; consulting fees from Agenus, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Corcept Therapeutics, Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, EMD Serono, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genmab, GlaxoSmithKline, ImmunoGen, Itheos, MSD, Mersana Therapeutics, Novocure, OneXerna Therapeutics, Inc., PharmaMar, Regeneron, Sattucklabs, Seagen, and Sutro Biopharma; payments or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology Inc., Eisai Ltd, F. Hoffmann –La Roche, Genmab, GlaxoSmithKline, ImmunoGen, MSD, and Seagen; support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca, PharmaMar, and Roche; payment for advisory board participation from Agenus, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Corcept Therapeutics, Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, EMD Serono, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genmab, GlaxoSmithKline, ImmunoGen, Itheos, MSD, Mersana Therapeutics, Novocure, OneXerna Therapeutics, Inc., PharmaMar, Regeneron, Sattucklabs, Seagen, and Sutro Biopharma; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (all unpaid): ESMO (member, Officer, Co-Chair of the ESMO Gynaecological Cancers Congress 2023–2025, chair of the Gynaecological Track ESMO 2019, scientific track member Gynaecological Cancers ESMO 2018, ESMO 2020, ESMO 2022, member of the Gynaecological Cancers Faculty, subject editor for the Gynaecological Clinical Practice Guidelines), GCIG (member and Cervix Cancer Chair on behalf of GEICO).

I. Spanggaard: institutional Research Funding: Roche/Genentech, Puma Biotechnology, Inc., MSD, Merck, AstraZeneca, Incyte, Orion, Genmab, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bayer/Loxo Oncology, Lilly Pharmaceuticals/Loxo Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, Amgen, Repare Therapeutics; honoraria: AstraZeneca; support for travel and meeting attendance: Roche, Novartis, Merck/Pfizer, Incyte, and AstraZeneca.

G. I. Shapiro: grants or contracts from Merck KGaA/EMD Serono, Tango Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Pfizer, and Eli Lilly; consulting fees from Merck KGaA/EMD Serono, Bicycle Therapeutics, Bayer, Concarlo Holdings, Janssen, Syros, Zentaris, Blueprint Medicines, Kymera Therapeutics, and XinThera; and patents Dosage Regimen For Sapacitabine And Seliciclib (with Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals) and Compositions and Methods for Predicting Response and Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibition (with Liam Cornell).

A. ElNaggar: employee and shareholder of Natera, Inc.

S. Panni: payments or honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, and AstraZeneca.

A. L. Frazier: employed by and holds stocks and options in Puma Biotechnology, Inc.

D. DiPrimeo: employed by and holds stocks and options in Puma Biotechnology, Inc.

L.D. Eli: employed by and shareholder of Puma Biotechnology, Inc.

D.B. Solit: has acted in a consulting/advisory role for and received personal fees from Function Oncology, Pfizer, Vividion Therapeutics, Scorpion Therapeutics, Rain Therapeutics, Elsie Biotechnologies, Inc., FORE Therapeutics, Fog Pharma, PaigeAi, and BridgeBio; participated in a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Rain Therapeutics; and holds stock or stock options in Scorpion Therapeutics, Function Oncology, FORE Therapeutics, and Elsie Biotechnologies, Inc.

V. Ravichandrana and A. D’Souza declared no interests other than support for the present study from Puma Biotechnology, Inc.

Previously presented at: ESMO Congress, 9–13 September, 2022.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, Caceres MV, Hasegawa K, Shapira-Frommer R, et al. , Pembrolizumab for Persistent, Recurrent, or Metastatic Cervical Cancer, New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (2021) 1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Coleman RL, Lorusso D, Gennigens C, González-Martín A, Randall L, Cibula D, et al. , Efficacy and safety of tisotumab vedotin in previously treated recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer (innovaTV 204/GOG-3023/ENGOT-cx6): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study, The Lancet Oncology. 22 (2021) 609–619. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tewari KS, Monk BJ, Vergote I, Miller A, de Melo AC, Kim H-S, et al. , Survival with Cemiplimab in Recurrent Cervical Cancer, New England Journal of Medicine. 386 (2022) 544–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hyman DM, Piha-Paul SA, Won H, Rodon J, Saura C, Shapiro GI, et al. , HER kinase inhibition in patients with HER2- and HER3-mutant cancers, Nature. 554 (2018) 189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature25475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Connell CM, Doherty GJ, Activating HER2 mutations as emerging targets in multiple solid cancers, ESMO Open. 2 (2017) e000279. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xiang L, Jiang W, Ye S, He T, Pei X, Li J, et al. , ERBB2 mutation: A promising target in non-squamous cervical cancer, Gynecol. Oncol. 148 (2018) 311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zammataro L, Lopez S, Bellone S, Pettinella F, Bonazzoli E, Perrone E, et al. , Whole-exome sequencing of cervical carcinomas identifies activating ERBB2 and PIK3CA mutations as targets for combination therapy, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116 (2019) 22730–22736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911385116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Awada A, Colomer R, Inoue K, Bondarenko I, Badwe RA, Demetriou G, et al. , Neratinib plus paclitaxel vs trastuzumab plus paclitaxel in previously untreated metastatic ERBB2-positive breast cancer: The NEfERT-T randomized clinical trial, JAMA oncology. 2 (2016) 1557–1564. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chan A, Moy B, Mansi J, Ejlertsen B, Holmes FA, Chia S, et al. , Final efficacy results of neratinib in HER2-positive hormone receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer from the phase III ExteNET trial, Clin Breast Cancer 21 (2021) 80–91.e87. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Saura C, Oliveira M, Feng YH, Dai MS, Chen SW, Hurvitz SA, et al. , Neratinib plus capecitabine versus lapatinib plus capecitabine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer previously treated with ≥ 2 HER2-directed regimens: Phase III NALA trial, J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (2020) 3138–3149. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bose R, Li S, Primeau TM, Highkin MK, Tipton AR, Vemalapally N, et al. , Abstract PS4–13: Irreversible inhibition of HER2 activating mutations with neratinib enhances the pre-clinical efficacy of trastuzumab emtansine and trastuzumab deruxtecan, Cancer Res. 81 (2021) PS4–13. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.Sabcs20-ps4-13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kavuri SM, Jain N, Galimi F, Cottino F, Leto SM, Migliardi G, et al. , HER2 activating mutations are targets for colorectal cancer treatment, Cancer Discov. 5 (2015) 832–841. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-14-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rabindran SK, Discafani CM, Rosfjord EC, Baxter M, Floyd MB, Golas J, et al. , Antitumor activity of HKI-272, an orally active, irreversible inhibitor of the HER-2 tyrosine kinase, Cancer Res. 64 (2004) 3958–3965. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-03-2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim K, Hu W, Audenet F, Almassi N, Hanrahan AJ, Murray K, et al. , Modeling biological and genetic diversity in upper tract urothelial carcinoma with patient derived xenografts, Nat Commun. 11 (2020) 1975. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15885-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oaknin A, Friedman CF, Roman LD, D’Souza A, Brana I, Bidard FC, et al. , Neratinib in patients with HER2-mutant, metastatic cervical cancer: Findings from the phase 2 SUMMIT basket trial, Gynecol. Oncol. 159 (2020) 150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. , New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1), Eur J Cancer. 45 (2009) 228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].O JH, Lodge MA, Wahl RL, Practical PERCIST: A simplified guide to PET response criteria in solid tumors 1.0, Radiology. 280 (2016) 576–584. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016142043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, et al. , Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology, J. Mol. Diagn. 17 (2015) 251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rose Brannon A, Jayakumaran G, Diosdado M, Patel J, Razumova A, Hu Y, et al. , Enhanced specificity of clinical high-sensitivity tumor mutation profiling in cell-free DNA via paired normal sequencing using MSK-ACCESS, Nat Commun. 12 (2021) 3770. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics. Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas: ). 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [21].AACR Project GENIE Consortium, AACR Project GENIE: Powering precision medicine through an international consortium, Cancer Discov. 7 (2017) 818–831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-17-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ulaner GA, Saura C, Piha-Paul SA, Mayer I, Quinn D, Jhaveri K, et al. , Impact of FDG PET imaging for expanding patient eligibility and measuring treatment response in a genome-driven basket trial of the pan-HER kinase inhibitor, neratinib, Clinical Cancer Research. 25 (2019) 7381–7387. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-19-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, et al. , Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study, Lancet Oncol. 21 (2020) 1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Andre T, Berton D, Curigliano G, Ellard S, Pérez JMT, Arkenau H-T, et al. , Safety and efficacy of anti–PD-1 antibody dostarlimab in patients (pts) with mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) solid cancers: Results from GARNET study, J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (2021) 9–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.3_suppl.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cortés J, Kim S-B, Chung W-P, Im S-A, Park YH, Hegg R, et al. , Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine for breast cancer, N. Engl. J. Med. 386 (2022) 1143–1154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shitara K, Bang Y-J, Iwasa S, Sugimoto N, Ryu M-H, Sakai D, et al. , Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive gastric cancer, N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (2020) 2419–2430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Meric-Bernstam F, Makker V, Oaknin A, Oh D-Y, Banerjee SN, Martin AG, et al. , Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) in patients (pts) with HER2-expressing solid tumors: DESTINY-PanTumor02 (DP-02) interim results, J Clin Oncol 41 (2023) abstr LBA3000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.17_suppl.LBA3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Smyth LM, Piha-Paul SA, Won HH, Schram AM, Saura C, Loi S, et al. , Efficacy and determinants of response to HER kinase inhibition in HER2-mutant metastatic breast cancer, Cancer Discov. 10 (2020) 198–213. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-19-0966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zuo WJ, Jiang YZ, Wang YJ, Xu XE, Hu X, Liu GY, et al. , Dual characteristics of novel HER2 kinase domain mutations in response to hER2-targeted therapies in human breast cancer, Clin. Cancer Res. 22 (2016) 4859–4869. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bose R, Kavuri SM, Searleman AC, Shen W, Shen D, Koboldt DC, et al. , Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer, Cancer Discov. 3 (2013) 224–237. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Greulich H, Kaplan B, Mertins P, Chen TH, Tanaka KE, Yun CH, et al. , Functional analysis of receptor tyrosine kinase mutations in lung cancer identifies oncogenic extracellular domain mutations of ERBB2, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109 (2012) 14476–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jasra S, Opyrchal M, Norton L, Mehta R, A rare case of S310F somatic ERBB2 mutation in a HER2-nonamplified breast cancer, Clinical Breast Cancer. 17 (2017) e37–e41. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Li BT, Smit EF, Goto Y, Nakagawa K, Udagawa H, Mazières J, et al. , Trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2-mutant non–small-cell lung cancer, N. Engl. J. Med. 386 (2021) 241–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Li Z, Chen S, Feng W, Luo Y, Lai H, Li Q, et al. , A pan-cancer analysis of HER2 index revealed transcriptional pattern for precise selection of HER2-targeted therapy, EBioMedicine. 62 (2020) 103074. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Smith HO, Tiffany MF, Qualls CR, Key CR, The rising incidence of adenocarcinoma relative to squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix in the United States--a 24-year population-based study, Gynecol. Oncol. 78 (2000) 97–105. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Francoeur AA, Liao C-I, Caesar MA, Chan A, Kapp DS, Cohen JG, et al. , The increasing incidence of stage IV cervical cancer in the USA: what factors are related?, Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 32 (2022) 1115–1122. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ehmann S, Sassine D, Straubhar AM, Praiss AM, Aghajanian C, Alektiar KM, et al. , Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the cervix: Clinical outcomes and genomic drivers, Gynecol. Oncol. 167 (2022) 458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Karamurzin YS, Kiyokawa T, Parkash V, Jotwani AR, Patel P, Pike MC, et al. , Gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma: An aggressive tumor with unusual metastatic patterns and poor prognosis, Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 39 (2015) 1449–1457. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kuruma A, Kodama M, Hori Y, Sato K, Fujii M, Isohashi F, et al. , Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix associated with poor response to definitive radiotherapy, Cancers (Basel). 15 (2022). doi: 10.3390/cancers15010170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kojima A, Shimada M, Mikami Y, Nagao S, Takeshima N, Sugiyama T, et al. , Chemoresistance of gastric-type mucinous carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A study of the sankai gynecology study group, Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 28 (2018) 99–106. doi: 10.1097/igc.0000000000001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.