Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K) plays an important role in signaling via a wide range of receptors such as those for antigen, growth factors, and a number of cytokines, including interleukin-2 (IL-2). PI 3-K has been implicated in both IL-2-induced proliferation and prevention of apoptosis. A number of potential mechanisms for the recruitment of PI 3-K to the IL-2 receptor have been proposed. We now have found that tyrosine residues in the IL-2 receptor β chain (IL-2Rβ) are unexpectedly not required for the recruitment of the p85 component of PI 3-K. Instead, we find that Jak1, which associates with membrane-proximal regions of the IL-2Rβ cytoplasmic domain, is essential for efficient IL-2Rβ–p85 interaction, although some IL-2Rβ–p85 association can be seen in the absence of Jak1. We also found that Jak1 interacts with p85 in the absence of IL-2Rβ and that IL-2Rβ and Jak1 cooperate for the efficient recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. This is the first report of a PI 3-K–Jak1 interaction, and it implicates Jak1 in an essential IL-2 signaling pathway distinct from the activation of STAT proteins.

High-affinity interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptors (IL-2Rs) are composed of three chains, denoted IL-2Rα, IL-2Rβ, and the common cytokine receptor γ chain, γc, which is shared by the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15 (17, 18, 31). IL-2 induces the heterodimerization of IL-2Rβ and γc, which together are necessary and sufficient for IL-2 signaling (18). Although neither IL-2Rβ nor γc has intrinsic protein tyrosine kinase catalytic activity, IL-2 rapidly induces tyrosine phosphorylation of these chains and a number of intracellular proteins (35). Many proteins can associate with the IL-2Rs. Whereas γc interacts with Jak3 (2, 22, 29) and calpain (23), IL-2Rβ interacts with Src family kinases (35), Syk kinase (35), Shc (5, 7, 25), Jak1 (2, 22, 29), Jak3 (29, 39), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K) (26, 36).

PI 3-K phosphorylates the D3 position of the inositol group of phosphoinositide lipids to generate phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate [PtdIns(3)P], PtdIns(3,4)P2, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3; the last two of these products have been shown to be important regulators of cellular proliferation (12). PI 3-K is composed of an 85-kDa regulatory subunit and a 110-kDa catalytic subunit. p85 associates with receptors and is tyrosine phosphorylated in a ligand-dependent fashion by many growth factors and cytokines (12), suggesting an involvement of PI 3-K in growth regulation. p85 can also associate with transmembrane proteins important in T-cell activation, including CD4, CTLA-4, CD28, and the ζ chain of the T-cell receptor (38). PI 3-K coupling to CD28 (38), CTLA-4 (30), the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β chain (4), and the IL-7 receptor α chain (37) occurs via a direct interaction between an SH2 domain of p85 and phosphorylated YXXM [(p)YXXM] binding motifs in the cytoplasmic regions of these molecules. In the insulin (32) and IL-4 (15) receptors, insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and IRS-2 bind to phosphorylated NPXY motifs on the receptors and provide SH2 docking sites for p85, whereas in the case of CD4 and the T-cell receptor, recruitment can occur via either the SH2 or SH3 domains of Src family kinases (p56lck and p59fyn) (28).

PI 3-K has been implicated in two important functions for IL-2: IL-2-induced proliferation (13) and prevention of apoptosis (1). Surprisingly, however, neither IL-2Rβ nor γc contains a (p)YXXM PI 3-K binding motif or an NPXY IRS binding motif, yet p85 has been reported to associate with IL-2Rβ and to be tyrosine phosphorylated following IL-2 stimulation (26). The bases for the recruitment and phosphorylation of p85 have remained unclear. Whereas one study suggested that p85 binding is mediated by tyrosine 392 (Y392) of IL-2Rβ (36), others indicated that the membrane-proximal serine-rich region (S region, amino acids 267 to 323) of IL-2Rβ is required for the tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 and the production of PtdInsPs (11, 21). Finally, the Src family kinases p56lck and p59fyn, which associate with the A region (amino acids 313 to 382 of IL-2Rβ), have been implicated in IL-2-induced recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 (14, 33), although it was suggested that another IL-2-induced kinase might also prove to be important (33). In accord with this hypothesis and because of the importance of the S region for both the generation of PtdInsPs (11, 21) and the association of Jak1 (22), we have further investigated the basis for PI 3-K recruitment to the IL-2R and now report the critical role of a novel PI 3-K p85–Jak1 interaction that implicates Jak1 in an essential IL-2 signaling pathway distinct from the activation of STAT proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Human IL-2Rβ and γc cDNAs were cloned into pME18S, in which expression is driven by the SRα promoter (34); the murine Jak1 cDNA was cloned in pMLCMV; human Jak3 cDNA was cloned in pME18S; the Lck cDNA was cloned in pTEJ8. IL-2Rβ mutants in pME18S were prepared by using the Altered Sites in vitro mutagenesis system (Promega) as previously described (7). The dominant negative Jak1 construct (DNJ1) was analogously prepared by using an oligonucleotide designed to change lysine 907 (AAG) in the JH1 kinase domain to arginine (AGG). Jak1 mutants in pME18S-FLAG were prepared by standard PCR-based methods. The human PI 3-K p85 cDNA (3) and the mutant forms of p85 (10) have been described elsewhere. Jak1, Jak1 mutants, Jak2, Jak3, and Lck were tagged with the FLAG epitope at their C termini by standard PCR-based methods. In each case, a 5′ primer spanning a unique restriction site in each kinase was prepared, whereas a 3′ primer contained the FLAG tag, a ClaI site, and a new stop codon. The FLAG-tagged kinases were then subcloned into pME18S, first subcloning into pBluescript as an extra step if additional restriction sites were needed.

Cell culture and transfections.

32D cells expressing wild-type and mutated IL-2Rβ have been described elsewhere (7). Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were isolated from blood of normal donors by using lymphocyte separation medium (Organon Teknika). Phytohemagglutin (PHA)-activated PBL (PHA blasts) were prepared by culturing PBL for 72 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 μg of PHA (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml. Cells were rested overnight in RPMI 1640–10% FBS, washed, and resuspended for 1 h in fresh medium prior to stimulation with 0 or 2 nM IL-2. YT, Molt4β, and MT-2 cells were grown in RPMI 1640–10% FBS. YT is an NK-like cell line, MT-2 is an human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-transformed T-cell line, and Molt4β cells represent Molt4 T cells stably transfected with IL-2Rβ (16). While parental Molt4 cells cannot respond to IL-2, Molt4β cells signal when stimulated with IL-2. For IL-2 stimulation, cells were rested for 4 h in RPMI 1640–1% FBS and then resuspended in RPMI 1640–10% FBS prior to treatment with 0 or 2 nM IL-2. IL-2-dependent CTLL-2 murine T cells were maintained in RPMI 1640–10% FBS containing 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol and 20 U of IL-2 per ml. 293 T+ and A49 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS and 100 U each of penicillin and streptomycin per ml and transfected with plasmids by the calcium phosphate method. Cells were harvested after 36 to 48 h. A49 is a murine fibroblast cell line derived from mice lacking expression of Jak1 (27).

Immunoprecipitations and Western blotting.

Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, lysed in lysis buffer [10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.875% Brij 96, 0.125% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 10 μg each of leupeptin and aprotinin per ml, 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF)], and centrifuged at 18,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with humanized Mikβ1 monoclonal antibody (MAb) to IL-2Rβ (hMikβ1) (8), MAb M2 to the FLAG epitope (Babco), or antiserum to PI 3-K p85 or Akt (anti-Akt1; Upstate Biotechnology Inc. [UBI] catalog no. 06-558), and protein A-agarose beads for 4 h at 4°C. The beads were washed four times in lysis buffer, and samples were run on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–8, 8 to 16, 4 to 20, or 16% gels (Novex), transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore), and immunoblotted with antiserum to either p85 (UBI) or Akt (Santa Cruz) or with MAb to Jak1 (Transduction Laboratories), IL-2Rβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FLAG, or phosphotyrosine (4G10; UBI). Blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham) after incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham).

Akt in vitro kinase assay.

32Dβ cells were rested overnight in RPMI without serum or IL-3 and then stimulated with 2 nM IL-2 for 15 min. Cells were washed, lysed, and immunoprecipitated as described above, using anti-Akt antibody (UBI). The beads were washed four times with lysis buffer and twice with kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5 μM ATP, 0.2 mM EGTA). The beads were then resuspended in 40 μl of kinase buffer containing 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and 500 ng of histone H2B peptide (Boehringer Mannheim) and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with 2× SDS sample buffer, and proteins were boiled and loaded on SDS–16% polyacrylamide gels. The gels were then dried and exposed to film.

RESULTS

Association of PI 3-K p85 with IL-2Rβ is not dependent on phosphorylated tyrosine residues.

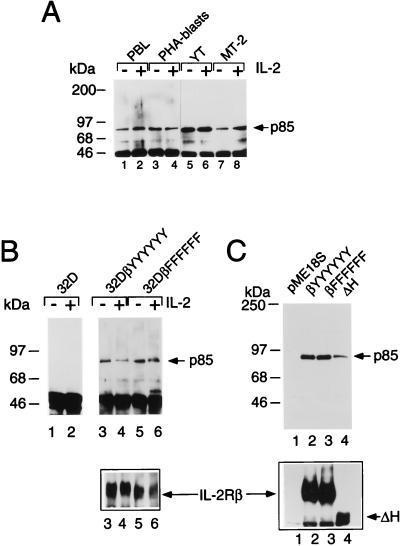

We first investigated whether PI 3-K p85 could associate with IL-2Rβ in different cell types and found that p85 could associate with IL-2Rβ in freshly isolated PBL, PHA blasts, YT NK-like cells, and HTLV-1-transformed MT-2 T cells (Fig. 1A). The interaction was also seen in 32D cells transfected with wild-type IL-2Rβ (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4). The fact that the interaction was seen in 32D-IL-2Rβ cells and in freshly isolated PBL in the absence of IL-2 stimulation suggested that phosphorylation of IL-2Rβ might not be required for this interaction. Indeed, p85 could also interact with a mutant form of IL-2Rβ in which all tyrosine residues, including the previously implicated Y392, were mutated to phenylalanines (βFFFFFF [lanes 5 and 6]), indicating that IL-2Rβ phosphotyrosine docking sites do not mediate this interaction. We confirmed this finding in assays using 293 T+ cells (Fig. 1C) and COS-7 cells (data not shown) by showing that p85 could associate not only with wild-type IL-2Rβ (lane 2) but also with a mutant form of IL-2Rβ in which all tyrosine residues had been mutated to phenylalanines (lane 3) or with an IL-2Rβ truncation mutant lacking residues 380 to 525 (ΔH mutant [lane 4]).

FIG. 1.

Tyrosine residues of IL-2Rβ are not required for its association with p85. (A) Constitutive association of IL-2Rβ and p85. Freshly isolated PBL (lanes 1 and 2), PHA blasts (lanes 3 and 4), YT cells (lanes 5 and 6), or MT-2 cells (lanes 7 and 8) were starved for ≥4 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% FBS and were not stimulated (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or were stimulated with 2 nM IL-2 (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) for 10 min; cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with hMikβ1 and immunoblotted with anti-p85. (B) Coprecipitation of p85 with IL-2Rβ in 32D cells expressing wild-type IL-2Rβ (lanes 3 and 4) or a mutated form of IL-2Rβ in which all six tyrosines were mutated to phenylalanines (lanes 5 and 6). Cells were starved of growth factor for 4 h, not stimulated or stimulated with 2 nM IL-2 for 10 min, washed, and lysed prior to immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. (C) Coprecipitation of p85 with IL-2Rβ constructs. 293 T+ cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing p85, Jak1, and either the empty vector (pME18S; lane 1) or pME18S driving expression of wild-type IL-2Rβ (βYYYYYY; lane 2), IL-2Rβ in which all tyrosines are mutated (βFFFFFF; lane 3), or an IL-2Rβ construct lacking residues 380 to 525 (ΔH mutant; lane 4). Cells were harvested 36 to 48 h posttransfection. Note that the decrease in apparent p85 coprecipitation (lane 4, top) corresponded to the decreased expression of IL-2Rβ ΔH (lane 4, bottom). Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting for panels B and C were performed as for panel A. The lower portions of panels B and C represent Western blots with goat antiserum to human IL-2Rβ (R & D Systems), as controls for expression.

Jak1 interacts with PI 3-K p85.

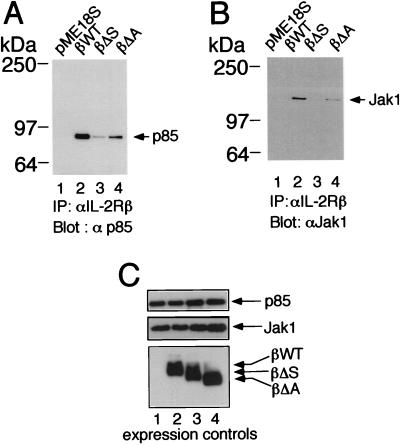

To investigate the regions of IL-2Rβ required for the association of p85, we used IL-2Rβ constructs lacking either the S or A region. Deletion of either region diminished association with p85 (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4 versus lane 2), correlating with the lower level of proliferation that is mediated by these constructs (35). As noted above, the S region has been shown to be important for the production of PtdInsPs and is known to be essential for the association of Jak1 (22) (Fig. 2B, lane 3). Interestingly, the A region not only is able to selectively mediate the association of Lck and Fyn (35), which as noted above have been suggested to play a role related to IL-2-mediated PI 3-K recruitment and phosphorylation (14, 33), but also is required for the optimal binding of both p85 (Fig. 2A, lane 4) and Jak1 (Fig. 2B, lane 4) to IL-2Rβ. The importance of both the A and S regions for IL-2-mediated activation of PI 3-K was next evaluated by assaying for the activity of Akt (protein kinase B), a kinase known to be activated by PI 3-K (6). Indeed, both the A and S regions are vital for downstream signaling from PI 3-K, as IL-2-induced activation of Akt in vitro kinase activity required the integrity of both regions (Fig. 3A; compare lanes 6 and 8 with lane 4).

FIG. 2.

Importance of the S and A regions of IL-2Rβ for the association of PI 3-K p85 and Jak1. (A) The S and A regions are required for optimal association of IL-2Rβ and p85. 293 T+ cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Jak1, p85, and either wild-type (βWT) or mutant forms of IL-2Rβ, immunoprecipitated (IP) with hMikβ1, and then Western blotted with anti-p85. (B) The S and A regions are required for optimal association of IL-2Rβ and Jak1. 293 T+ cells were cotransfected with plasmids as for panel A, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with hMikβ1 followed by Western blotting with MAb to Jak1. (C) Lysates of the transfected 293T+ cells used for panels A and B were blotted with anti-Jak1 (Transduction Laboratories), anti-p85 (UBI), or anti-IL-2Rβ (Santa Cruz).

FIG. 3.

Importance of the S and A regions of IL-2Rβ for Akt IL-2-induced activation. (A) 32D cells expressing either wild-type (βWT) or mutant forms of human IL-2Rβ were rested overnight and then stimulated with IL-2 for 15 min. In vitro kinase (IVK) assays were performed on Akt immunocomplexes, using histone H2B peptide as an exogenous substrate. (B) Loading control for the in vitro kinase assay. Immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Akt was followed by Western blotting with anti-Akt antibody. (C) Receptor expression controls are also shown for each cell line.

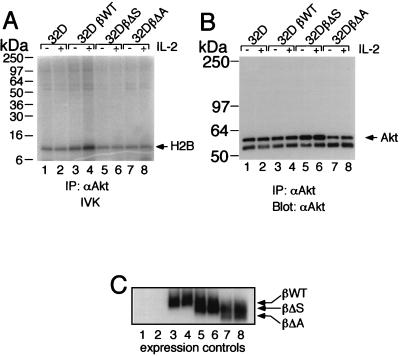

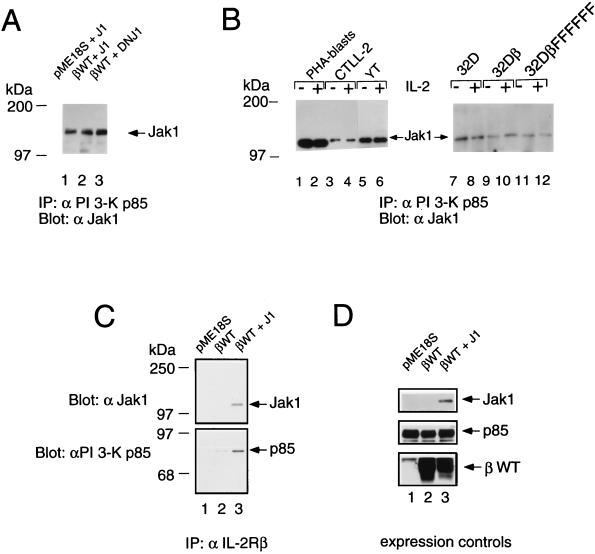

In view of the diminished association of PI 3-K p85 with both the A and S mutants, we investigated the importance of Jak1 in the recruitment of PI 3-K p85 to IL-2Rβ and whether Jak1 could itself associate with p85. We first transfected 293 T+ cells with p85 and Jak1 and found that p85 could be coprecipitated with Jak1, even in the absence of IL-2Rβ (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2). The catalytic activity of Jak1 was not required for this interaction, as demonstrated by the ability of the DNJ1 construct to also associate with p85 (lane 3; also discussed below in relation to Fig. 9). Constitutive association of Jak1 and p85 was also found in PHA blasts and in CTLL-2, YT, 32D, 32Dβ, and 32DβFFFFFF cells (Fig. 4B). Because parental 32D cells do not express IL-2Rβ, it is clear that IL-2Rβ was not required for this interaction, and correspondingly, IL-2 stimulation did not affect the interaction. Given that IL-2Rβ and Jak1 constitutively associate (2, 22, 29), to investigate whether IL-2Rβ could interact with p85 even in the absence of Jak1, we used Jak1-deficient murine fibroblasts (A49 cells) derived from a Jak1-deficient mouse (27). Transfection of IL-2Rβ into A49 cells allowed coprecipitation of p85 with anti-IL-2Rβ antibodies; however, this interaction was significantly augmented if Jak1 was cotransfected (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Jak1 and IL-2Rβ cooperate for efficient recruitment of PI 3-K p85. (A) Wild-type Jak1 (J1) and DNJ1 associate with p85. 293 T+ cells were cotransfected with a vector control or a plasmid expressing wild-type IL-2Rβ (βWT), Jak1, or DNJ1. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-p85 and then Western blotted with anti-Jak1. (B) Constitutive association of Jak1 and p85. PHA blasts and CTLL-2, YT, 32D, 32Dβ, and 32DβFFFFFF cells were starved for 4 h, stimulated with 2 nM IL-2 for 10 min, washed, and lysed. Immunoprecipitations and Western blotting were performed as for panel A. (C) The interaction of IL-2Rβ and p85 is augmented by the presence of Jak1. Murine fibroblasts lacking Jak1 (A49 cells) were transfected with pME18S, wild-type IL-2Rβ, or IL-2Rβ plus Jak1. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with hMikβ1 and then blotted with antiserum to Jak1 (top) or p85 (bottom). (D) Lysates of the cells described for panel C were Western blotted to confirm expression of transfected cDNAs. Note that there is somewhat more IL-2Rβ expressed in lane 2 than in lane 3. This makes it even more clear that the increased coprecipitation in panel C, lane 3, is due to the presence of Jak1.

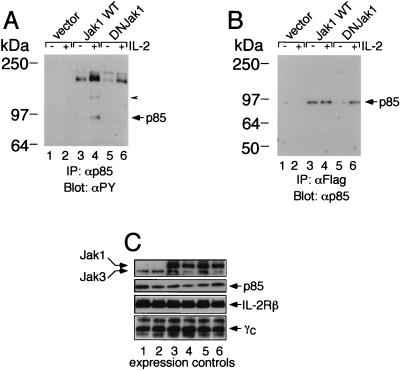

FIG. 9.

Jak1 is required for IL-2-induced phosphorylation of PI 3-K p85. (A) Transfection of Jak1 is required for IL-2-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PI 3-K p85 in A49 cells. A49 cells were transfected with IL-2Rβ, γc, and Jak3, with or without wild-type (WT) Jak1 or DNJ1 (DNJak1). Cells were washed and starved overnight in DMEM–1% FBS and then not stimulated or stimulated for 10 min with 2 nM IL-2. The arrowhead points to a band that we believe to be Jak1. IP, immunoprecipitation; αPY, antiphosphotyrosine. (B) The lack of phosphorylation of p85 in lane 6 of panel A was not due to lack of association of DNJ1 with p85. Note that the decreased association of DNJ1 with p85 in the absence of IL-2 was not expected; however, the key point is that the degree of association in lane 6 was similar to that seen with wild-type Jak1 (lane 4). (C) Controls for expression of Jak1, Jak3, p85, IL-2Rβ, and γc in the transfected A49 cells.

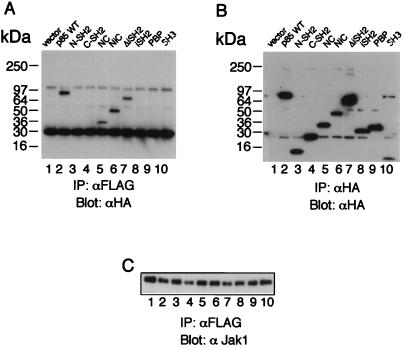

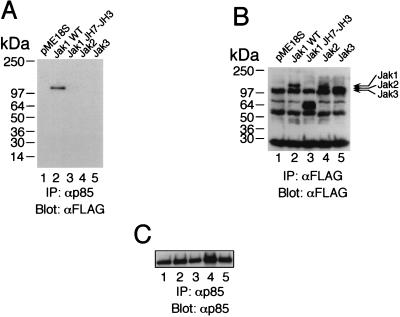

To better understand the nature of the interaction between p85 and Jak1, we mapped the regions on each protein that mediate the interaction (Fig. 5 and 6). We first used a series of constructs corresponding to different domains of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged p85 (10). Interestingly, constructs containing both SH2 regions of p85 mediated the interaction with Jak1 even when the inter-SH2 region was deleted (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 to 7). The N-terminal SH2 domain of p85 could not interact at all, and at most a weak interaction was detected with the C-terminal SH2 domain (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4, and data not shown). We next mapped the region of Jak1 that interacts with p85. As shown in Fig. 6A, full-length Jak1 (lane 2), but not a C-terminal truncation mutant of Jak1 lacking the JH1 and JH2 regions (containing the kinase and pseudokinase domains, respectively) (lane 3), could associate. However, given that p85 also can associate with the DNJ1 construct, the catalytic activity of Jak1 does not appear to be essential for the interaction. Interestingly, neither Jak2 nor Jak3 could associate with p85 (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 and 5), indicating that the ability of Jak1 to interact with p85 was specific and not a general property of Jak kinases. It is interesting that Jak1 has three YXXM motifs, including one in the JH1 region; it will be interesting to determine if this motif contributes to the association of Jak1 with p85.

FIG. 5.

Both of the SH2 domains of p85 are required for its efficient association with Jak1. (A) 293 T+ cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged Jak1 and with the indicated HA-tagged forms of p85. Immunoprecipitations (IP) with anti-FLAG M2 MAb were followed by Western blotting with anti-HA MAb. The p85 constructs (described in reference 10) are as follows: N-SH2, residues 329 to 439, spanning the more N-terminal of the two SH2 domains in p85; C-SH2, residues 563 to 724, spanning the more C-terminal SH2 domain; NC, residues 329 to 439 plus residues 563 to 724, containing both SH2 domains but lacking the p110 binding (inter-SH2) region; NiC, residues 329 to 724, like NC except that it includes the inter-SH2 region; ΔiSH2, full-length p85 that lacks the 439–563 inter-SH2 region; iSH2, residues 425 to 616, a construct that contains only the inter-SH2 region; PBP, residues 79 to 328, containing the Pro-Bcr-Pro region located between the SH3 and N-terminal SH2 domains of p85; and SH3, residues 1 to 78, spanning the SH3 domain. All constructs have N-terminally positioned HA tags. WT, wild type. (B) Expression control for the HA-tagged forms of p85. (C) Expression controls for Jak1.

FIG. 6.

The JH1 and JH2 regions of Jak1 are required for interaction with p85. Jak2 and Jak3 do not interact with p85. (A) 293 T+ cells were transfected with p85 and with the indicated forms of FLAG-tagged Jak1 C-terminal deletions or FLAG-tagged Jak2 or Jak3. Immunoprecipitations (IP) with anti-p85 antibody were followed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG M2 MAb. WT, wild type. (B) Expression control for the FLAG-tagged forms of Jak1, Jak2, and Jak3. (C) Expression controls for p85.

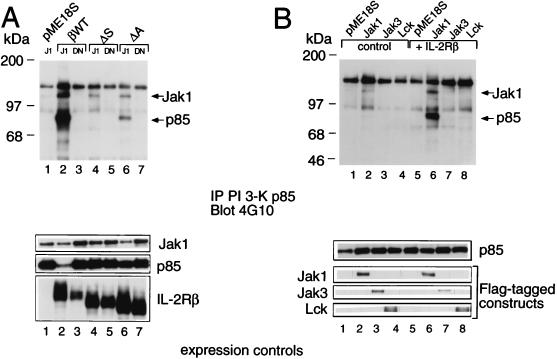

Jak1-mediated phosphorylation of p85 requires IL-2Rβ.

The ability of Jak1 to interact with p85 suggested that Jak1 might mediate the tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. We investigated this possibility by using 293 T+ cells cotransfected with plasmids expressing p85, Jak1, and either a vector control, wild-type IL-2Rβ, or a mutant form of IL-2Rβ. Interestingly, although Jak1 and p85 could associate in the absence of IL-2Rβ (e.g., in 32D cells [Fig. 4B, lanes 7 and 8]), essentially no tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 was seen in 293 T+ cells transfected with only Jak1 and p85, but substantial phosphorylation was seen when IL-2Rβ was additionally expressed (Fig. 7A, lane 2 versus lane 1). Note that an increase in the phosphorylation of Jak1 was also seen when IL-2Rβ was present (Fig. 7B, lane 6 versus lane 2), but the relative increase in phosphorylation in p85 exceeded the increase in phosphorylation of Jak1, suggesting that part of the effect may be due to augmented recruitment of p85 when both IL-2Rβ and Jak1 are present. This phosphorylation required catalytically active Jak1 since no tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 was seen with the DNJ1 construct (Fig. 7A, lane 3), even though p85 could associate with DNJ1 (Fig. 4A, lane 3). Efficient association of Jak1 with IL-2Rβ was required for optimal phosphorylation of p85, as demonstrated by the greatly diminished phosphorylation of p85 when the S region of IL-2Rβ was deleted (Fig. 7A, lane 4). Deletion of the A region of IL-2Rβ resulted in a smaller decrease in p85 phosphorylation (lane 6), corresponding with the lesser effect of this deletion on the association of Jak1 with IL-2Rβ (Fig. 2B). Unlike Jak1, Jak3 did not mediate detectable p85 phosphorylation (Fig. 7B, lane 7 versus lane 6) even though Jak3 can also associate with IL-2Rβ (29, 39). Wild-type Lck could mediate weak p85 phosphorylation but at a level much lower than that seen with Jak1, even in the presence of IL-2Rβ (lane 8 versus lane 6). These data indicate a specificity for the role played by Jak1.

FIG. 7.

p85 tyrosine phosphorylation is mediated by Jak1, but not by Jak3 or Lck, in an IL-2Rβ-dependent fashion. (A) Jak1 and IL-2Rβ are required for tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. 293 T+ cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing p85, Jak1, DNJ1, and either wild-type (βWT) or mutant forms of IL-2Rβ. Cells were harvested 36 to 48 h posttransfection, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in lysis buffer. Supernatants were boiled in SDS reducing sample buffer and immunoblotted to evaluate expression of transfected cDNAs; alternatively, lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with antiserum to p85 and immunoblotted with 4G10. Expression of transfected constructs (Jak1, p85, and IL-2Rβ constructs) was evaluated by Western blotting (bottom). (B) Neither Jak3 nor Lck can phosphorylate p85. 293 T+ cells were cotransfected with PI 3-K (all lanes), FLAG-tagged Jak1 (lanes 2 and 6), FLAG-tagged Jak3 (lanes 3 and 7), or FLAG-tagged Lck (lanes 4 and 8). In lanes 5 to 8, cells were additionally transfected with IL-2Rβ; cells in lanes 1 to 4 were not. Immunoprecipitations and Western blotting were performed as for panel A. Expression of p85 and FLAG-tagged kinases is shown at the bottom. The expression controls are all from one blot; the cut marks reflect the fact that the loading order for the controls was different from that used in the upper blot; the lanes were repositioned to correspond to the upper blot.

Jak1 is required for IL-2-induced phosphorylation of p85.

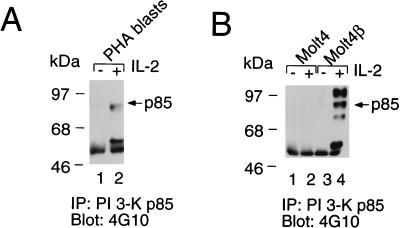

The above studies indicate that Jak1 can mediate phosphorylation of PI 3-K p85 in an overexpression system in which Jak1 is constitutively activated (19) but do not address the IL-2 inducibility of this phosphorylation event. We therefore evaluated p85 tyrosine phosphorylation in settings where Jak1 is not constitutively activated. IL-2 could induce tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 in normal PHA blasts (Fig. 8A) and in Molt4 T cells that were stably transfected with IL-2Rβ (so that they became responsive to IL-2) (Fig. 8B). To address the role of Jak1 in this process, given the ubiquitous expression of Jak1, we used a fibroblast cell line derived from Jak1-deficient mice (A49 cells) and transfected these cells with IL-2Rβ, γc, and Jak3, with or without Jak1 (Fig. 9). IL-2 could induce phosphorylation of PI 3-K p85 in the cells transfected with Jak1 (Fig. 9A, lane 4 versus lane 3), but this reconstituted fibroblast cell line exhibits lower IL-2-inducible phosphorylation of p85 than was seen in PHA blasts and Molt4β cells. No phosphorylation was seen in cells lacking Jak1 (lanes 1 and 2) or in cells transfected with the DNJ1 construct (lanes 5 and 6). The difference in tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 (lanes 4 and 6) cannot be explained by differences in the levels of p85 (Fig. 9B, lane 6 versus lane 4). Given the lack of endogenous Jak1 in A49 cells, this experiment also confirms the association of p85 with a catalytically dead form of Jak1. These data indicate the vital role played by Jak1 in tyrosine phosphorylation of p85.

FIG. 8.

IL-2-induced phosphorylation of PI 3-K. (A) IL-2 induces phosphorylation of p85 in normal PHA blasts. (B) IL-2 induces phosphorylation of p85 in Molt4β cells (lane 4 versus lane 3) but not in Molt4 cells (lanes 1 and 2). Immunoprecipitations (IP) and Western blotting were performed as for Fig. 7.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have investigated the basis for recruitment of PI 3-K to the IL-2R. Whereas PI 3-K p85 can associate with IL-2Rβ in the absence of Jak1 and with Jak1 in the absence of IL-2Rβ, both IL-2Rβ and Jak1 are simultaneously required for the most efficient recruitment of p85. The role of Jak1 is specific, as no coprecipitation of p85 with either Jak2 or Jak3 could be observed. Although Jak1 has been suggested to be dispensable for signaling by IL-2 (9) and IL-4 (20), our data are consistent with an important role for Jak1 in IL-2-mediated activation of PI 3-K. The essential role of Jak1 is consistent with activation of both Jak1 and Jak3 by IL-2 (reviewed in references 18, 31, and 35) and with the phenotype of Jak1 knockout mice (27).

Both the S (amino acids 267 to 323) and A (amino acids 313 to 382) regions of IL-2Rβ are required for p85 binding, with the S region being the more important. The importance of the S region is at least in part due to its role in mediating the binding of Jak1 to IL-2Rβ. This helps to explain prior observations (11, 21) that deletion of the S region results in a loss of IL-2-induced production of PtdInsPs. Interestingly, the coprecipitation of p85 with IL-2Rβ was not dependent on the phosphorylation of IL-2Rβ, as demonstrated by the ability of p85 to interact with an IL-2Rβ mutant in which all tyrosines were converted to phenylalanines. However, a previous study showed that a phosphorylated peptide spanning IL-2Rβ Y392 could partially inhibit the p85–IL-2Rβ interaction (36), raising the formal possibility that there is more than one contact point for p85 on IL-2Rβ. In addition to the S region, the A region was important for coprecipitation of p85. The A region not only is needed for maximal recruitment of Jak1 but also is vital for the recruitment of Src family kinases, consistent with previous reports indicating a role for Src family kinases in IL-2-mediated activation of PI 3-K. Thus, our data reveal a greater complexity than was previously appreciated for the recruitment and phosphorylation of PI 3-K wherein both Src family kinases and Jak1 are important. The identification of a role for Jak1 is consistent with an earlier hypothesis that an IL-2-induced tyrosine kinase besides an Src family kinase might be found to be important for IL-2-induced activation of PI 3-K (33).

We have shown that Jak1 is required for p85 phosphorylation, and as expected, catalytically active Jak1 was required for this as no p85 phosphorylation was seen with the DNJ1 construct. It was striking, however, that IL-2Rβ was also needed to achieve efficient tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 by Jak1. Thus, just as the most efficient recruitment of p85 required both IL-2Rβ and Jak1, IL-2-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 was also dependent on the presence of both proteins, suggesting cooperativity of IL-2Rβ and Jak1 in both interaction with and phosphorylation of p85. It is possible that IL-2Rβ serves to correctly position p85 so that it can be phosphorylated, most likely by Jak1, although we cannot exclude the formal possibility that p85 is instead phosphorylated by another kinase whose activity is dependent on the presence of Jak1. Such a hypothetical kinase would presumably be activated by Jak1 given that no tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 was seen with the dominant negative Jak1.

Together, our data not only indicate that IL-2Rβ and Jak1 cooperate for the recruitment and phosphorylation of PI 3-K but also indicate another essential function for Jak1 besides its role in mediating the activation of STAT proteins. Coupled to the demonstration that Stat3 can mediate the recruitment of p85 to the IFNAR-I chain of type I interferon receptors (24), it is now clear that both JAKs and STATs can play important roles in PI 3-K recruitment. Given the involvement of Jak1 activation in a range of cytokine receptors, these studies have important implications regarding the basis for PI 3-K recruitment, particularly to receptors lacking YXXM motifs but whose cognate cytokines are nevertheless known to induce the activation of PI 3-K.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. A. Cantrell for providing the PI 3-K p85 DNA (3), J. J. O’Shea for the human Jak3 cDNA, J. Hakimi for the hMikβ1 antibody, M. Tsang and R & D Systems for the anti-IL-2Rβ antiserum, K. Sugamura for Molt4β cells, I. Miyoshi for MT-2 cells, J. Yodoi for YT cells, J. Ihle for the murine Jak1 cDNA in pMLCMV, J. Ashwell for the Lck cDNA, and T. Mustelin for the multiple PI 3-K p85 truncation mutations. We thank J. H. Pierce, J. Ashwell, L. E. Samelson, A. Morimoto, and L. C. Cantley for valuable discussions and/or critical comments, and we thank A. Puel and S. John for assistance with preparing figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed N N, Grimes H L, Bellacosa A, Chan T O, Tsichlis P N. Transduction of interleukin-2 antiapoptotic and proliferative signals via Akt protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boussiotis V A, Barber D L, Nakarai T, Freeman G J, Gribben J G, Bernstein G M, D’Andrea A D, Ritz J, Nadler L M. Prevention of T cell anergy by signaling through the γc chain of the IL-2 receptor. Science. 1994;266:1039–1042. doi: 10.1126/science.7973657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhand R, Hiles I, Panayotou G, Roche S, Fry M J, Gout I, Totty N F, Truong O, Vicendo P, Yonezawa K, Kasuga M, Courtneidge S A, Waterfield M D. PI 3-kinase is a dual specificity enzyme: autoregulation by an intrinsic protein-serine kinase activity. EMBO J. 1994;13:522–533. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escobedo J A, Navankasattusas S, Kavanaugh W M, Milfay D, Fried V A, Williams L T. cDNA cloning of a novel 85 kd protein that has SH2 domains and regulates binding of PI 3-kinase to the PDGF B-receptor. Cell. 1991;65:75–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90409-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans G A, Goldsmith M A, Johnston J A, Xu W, Weiler S R, Erwin R, Howard O M, Abraham R T, O’Shea J J, Greene W C, Farrar W L. Analysis of interleukin-2-dependent signal transduction through the Shc/Grb2 adapter pathway. Interleukin-2-dependent mitogenesis does not require Shc phosphorylation or receptor association. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28858–28863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke T F, Kaplan D R, Cantley L C. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedmann M C, Migone T-S, Russell S M, Leonard W J. Different interleukin 2 receptor β-chain tyrosines couple to at least two signaling pathways and synergistically mediate interleukin 2-induced proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2077–2082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakimi J, Ha V C, Lin P, Campbell E, Gately M K, Tsudo M, Payne P W, Waldmann T A, Grant A J, Tsien W H, Schneider W P. Humanized Mikβ1, a humanized antibody to the IL-2 receptor β-chain that acts synergistically with humanized anti-TAC. J Immunol. 1993;151:1075–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higuchi M, Asao H, Tanaka N, Oda K, Takeshita T, Nakamura M, Van Snick J, Sugamura K. Dispensability of Jak1 tyrosine kinase for interleukin-2-induced cell growth signaling in a human T cell line. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1322–1327. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jascur T, Gilman J, Mustelin T. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in NFAT activation in T cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14483–14488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanazawa T, Keeler M I, Varticovski L. Serine-rich region of the IL-2 receptor β-chain is required for activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell Immunol. 1994;156:378–388. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapeller R, Cantley L C. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. BioEssays. 1994;16:565–576. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karnitz L M, Burns L A, Sutor S L, Blenis J, Abraham R T. Interleukin-2 triggers a novel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent MEK activation pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3049–3057. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karnitz L M, Sutor S L, Abraham R T. The src-family kinase, Fyn, regulates the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in an interleukin 2-responsive T cell line. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1799–1808. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keegan A D, Nelms K, White M F, Wang L M, Pierce J H, Paul W E. An IL-4 receptor region containing an insulin receptor motif is important for IL-4 mediated IRS-1 phosphorylation and cell growth. Cell. 1994;76:811–820. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumaki S, Asao H, Takeshita T, Kurahayashi Y, Nakamura M, Beckers T, Engels J W, Sugamura K. Cell type-specific tyrosine phosphorylation of IL-2 receptor β chain in response to IL-2. FEBS Lett. 1992;310:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81137-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonard W J. The molecular basis of X-linked combined immunodeficiency: defective cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:229–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin J-X, Leonard W J. Signaling from the IL-2 receptor to the nucleus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:313–332. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin J-X, Mietz J, Modi W S, John S, Leonard W J. Cloning of human Stat5B: reconstitution of interleukin-2-induced Stat5A and Stat5B DNA binding activity in COS-7 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10738–10744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malabarba M G, Kirken R A, Rui H, Koettnitz K, Kawamura M, O’Shea J J, Kalthoff F S, Farrar W L. Activation of JAK3, but not JAK1, is critical to interleukin-4 (IL4) stimulated proliferation and requires a membrane-proximal region of IL4 receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9630–9637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merida I, Williamson P, Kuziel W A, Greene W C, Gaulton G N. The serine-rich cytoplasmic domain of the interleukin-2 receptor β chain is essential for interleukin-2-dependent tyrosine protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6765–6770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyazaki T, Kawahara A, Fujii H, Nakagawa Y, Minami Y, Liu Z J, Oishi I, Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn B A, Ihle J N, Taniguchi T. Functional activation of Jak1 and Jak3 by selective association with IL-2 receptor subunits. Science. 1994;266:1045–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.7973659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noguchi M, Sarin A, Aman M J, Nakajima H, Shores E W, Henkart P A, Leonard W J. Functional cleavage of the common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc) by calpain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11534–11539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeffer L M, Mullersman J E, Pfeffer S R, Murti A, Shi W, Yang C H. STAT3 as an adapter to couple phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to the IFNAR1 chain of the type I interferon receptor. Science. 1997;276:1418–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravichandran K S, Burakoff S. The adapter protein Shc interacts with the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor upon IL-2 stimulation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1599–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remillard B, Petrillo R, Maslinsi W, Tsudo M, Strom T B, Cantley L, Varticovski L. Interleukin-2 receptor regulates activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14167–14170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodig S J, Meraz M A, White J M, Lampe P A, Riley J K, Arthur C D, King K L, Sheehan K C F, Yin L, Pennica D, Johnson E M, Jr, Schreiber R D. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudd C E, Janssen O, Cai Y C, da Silva A J, Raab M, Prasad K V. Two-step TCR zeta/CD3-CD4 and CD28 signaling in T cells: SH2/SH3 domains, protein-tyrosine and lipid kinases. Immunol Today. 1994;15:225–234. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell S M, Johnston J A, Noguchi M, Kawamura M, Bacon C M, Friedmann M, Berg M, McVicar D W, Witthun B A, Silvennoinen O, Goldman A S, Schmalstieg F C, Ihle J N, O’Shea J J, Leonard W J. Interaction of IL-2Rβ and γc chains with Jak1 and Jak3: implications for XSCID and XCID. Science. 1994;266:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7973658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider H, Prasad K V, Shoelson S, Rudd C. CTLA-4 binding to the lipid kinase phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;181:351–355. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugamura K, Asao H, Kondo M, Tanaka N, Ishii N, Ohbo K, Nakamura M, Takeshita T. The interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain: its role in the multiple cytokine receptor complexes and T cell development in XSCID. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:179–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun X J, Rothenberg P, Kahn C R, Backer J M, Araki E, Wilden P A, Cahill D A, Goldstein B J, White M F. Structure of the insulin receptor substrate IRS-1 defines a unique signal transduction protein. Nature. 1991;352:73–77. doi: 10.1038/352073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taichman R, Merida I, Torigoe T, Gaulton G N, Reed J C. Evidence that protein tyrosine kinase p56-Lck regulates the activity of phosphatidylinositol-3′-kinase in interleukin-2-dependent T-cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20031–20036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takebe Y, Seiki M, Fujisawa J, Hoy P, Yokota K, Arai K, Yoshida M, Arai N. SRα promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA expression system composed of the simian virus 40 early promoter and the R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:466–472. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taniguchi T. Cytokine signaling through nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases. Science. 1995;268:251–255. doi: 10.1126/science.7716517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Truitt K E, Mills G B, Turck C W, Imboden J B. SH2-dependent association of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase 85-kDa regulatory subunit with the interleukin-2 receptor β chain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5937–5943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkitaraman A R, Cowling R J. Interleukin-7 induces the association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with the alpha chain of the interleukin-7 receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2168–2174. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward S G. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and CD28-mediated T-cell co-stimulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:240–245. doi: 10.1042/bst0240240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu M-H, Berry J A, Russell S M, Leonard W J. Delineation of the regions of interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor β chain important for association of Jak1 and Jak3: Jak1-independent functional recruitment of Jak3 to IL-2Rβ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10719–10725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]