Abstract

Background.

Systematically recorded smoking data is not always available in vital statistics records, and even when available it can underestimate true smoking rates.

Objective.

To develop a prediction model for maternal tobacco smoking in late pregnancy based on birth certificate information using a combination of self- or provider-reported smoking and biomarkers (smoking metabolites) in neonatal blood spots as the alloyed gold standard.

Methods.

We designed a case-control study where childhood cancer cases were identified from the California Cancer Registry and controls were from the California birth rolls between 1983 and 2011 who were cancer-free by the age of 6. In this analysis, we included 894 control participants and performed high-resolution metabolomics analyses in their neonatal dried blood spots where we extracted cotinine [mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) = 177.1023] and hydroxycotinine (m/z = 193.0973). Potential predictors of smoking were selected from California birth certificates. Logistic regression with stepwise backward selection was used to build a prediction model. Model performance was evaluated in a training sample, a bootstrapped sample, and an external validation sample.

Results.

Out of seven predictor variables entered into the logistic model, five were selected by the stepwise procedure: maternal race/ethnicity, maternal education, child’s birth year, parity, and child’s birthweight. We calculated an overall discrimination accuracy of 0.72 and an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.81 (95% CI 0.77, 0.84) in the training set. Similar accuracies were achieved in the internal (AUC 0.81, 95% CI 0.77, 0.84) and external (AUC 0.69, 95% CI 0.64, 0.74) validation sets.

Conclusions.

This easy-to-apply model may benefit future birth registry-based studies when there is missing maternal smoking information; however, some smoking status misclassification remains a concern when only variables from the birth certificate are used to predict maternal smoking.

Keywords: maternal pregnancy smoking, tobacco biomarkers, neonatal blood spots, prediction model, birth certificates

Background

Tobacco use remains prevalent in US adult females, even though it decreased from 34% to 23% in the past 5 decades,1 and in pregnant women from 25.7% in 1985 to 10.1% in 2014.2 In California, maternal pregnancy smoking prevalence declined from ~50% in the late 1970s 3 to 15% from 1995–2002 4 and 5% from 2008–2018.5 Tobacco smoke contains multiple toxic compounds that can cross the placenta and has been associated with adverse infant and child outcomes, including low birth weight, preterm birth, congenital anomalies, and childhood cancers.6, 7

Maternal pregnancy smoking is an important confounding variable to consider in studies of maternal exposures and child outcomes, such as childhood cancers.8 Record-linkage studies are advantageous due to their (often) population-based nature, larger sample size, and lower cost, but frequently have limited or no information on lifestyle factors such as smoking. Systematically recorded smoking data may not be available in vital statistics records for some periods or in some regions possibly resulting in uncontrolled confounding.

Even when records collect smoking status, the quality of the data might be a concern as self-reported data on pregnancy smoking may be unreliable due to social stigma, thus, missing data are not missing at random. Two studies in the United States in the 2000s and 2010s showed that approximately 14% of smokers deny smoking in interviews.9, 10 Compared with CDC surveys and medical records, it has been estimated that birth certificates only capture 70.6–82.0% of prenatal smoking.11–13 Maternal smoking may be underreported on birth records because women fail to disclose or providers fail to record smoking; medical records are unavailable; or birth certificates are inaccurately filled out.12

Given concerns about the accuracy of smoking recorded on the birth certificate, measurement of tobacco smoking using a biomarker of exposure is preferable in research studies. Cotinine levels in newborns’ dried blood spots can be used as a biomarker of maternal smoking for pregnant women close to the time of delivery, with high sensitivity (92.3%) and specificity (99.7%).14, 15 Cotinine is the best marker of recent smoking including active and secondhand smoke.16, 17 However, although cotinine has a longer half-life than its parent compound, nicotine, it is only detectable for about 17 hours.18 Hydroxycotinine, metabolized by the hepatic enzyme cytochrome P450 2A6, is the major metabolite of cotinine in most individuals,19, 20 and is detectable for a longer period with an approximated half-life of 18 hours.21 Thus, a combination of cotinine and hydroxycotinine measures in biospecimens can identify active smokers.

Clinical prediction models have been used to predict tobacco-related disease,22 calibrate self-reported maternal smoking using urinary cotinine,23 and to characterize smoking patterns in older adults.24 Since biomarker assessments in large population-based studies is costly, we generated a clinical prediction model 25 for maternal late-pregnancy smoking based on variables routinely collected on birth certificates and a combination of self- or provider-reported smoking information and metabolomics-derived smoking biomarkers used together as the alloyed gold standard for maternal smoking.

Methods

Study design and participants

We utilized data from 899 control participants of a population-based case-control study of childhood cancers drawn from from California birth rolls between 1983 and 2011 who were cancer-free by the age of 6. Covariates were obtained from California birth certificates, including mothers’ tobacco use information. From 1989 to 2005 medical staff provided some limited maternal smoking information answering the question “Were there pregnancy complications due to tobacco use during pregnancy?”. Starting in 2007, the “number of cigarettes per day (3 months before pregnancy and during each trimester)” was reported on the birth certificate.8

Neonatal dried blood spots

We obtained neonatal dried blood spots from the Genetic Disease Screening Program (GDSP),26 from babies’ heel sticks between 12 and 48 hours after birth.27 Blood was put into six small circles on a specialized filter paper, dried at room temperature for at least 3 hours, and shipped to the Neonatal and Prenatal Screening Laboratory within 24 hours of collection.27 After screening, left-over specimens were packed and stored at −20°C.27 We analyzed neonatal blood spots using liquid chromatography with ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry.28 Additional details concerning dried blood specimens and metabolomics analysis were previously described.29 After excluding 6 outliers, 894 subjects remained for analysis.

Outcome definition

We extracted cotinine (m/z = 177.1023) and hydroxycotinine (m/z = 193.0973) from the feature table generated by xMSanalyzer.30 As a large volume of blood is needed to detect enough metabolites to discern secondhand smoke exposure,15 we considered both metabolites’ presence to be evidence of maternal active smoking. We considered mothers to be active smokers if they were self- or provider-reported smokers on birth certificates or if we detected cotinine or hydroxycotinine in the newborn’s blood at intensities greater than the 86th percentile, a cut-off chosen based on the prevalence reported by contemporaneous surveys of California women across our study period.3–5, 31 This yielded an overall mean prevalence of smoking of 17% from any smoking indicator.32

Predictors

We identified potential predictors as factors that were associated in our data with maternal smoking in univariate analysis. We excluded candidate predictors missing data in >10% of the sample to minimize misclassification when imputing missing values for predictors.33 To improve model performance for predicting a rare event, we followed the events per variable (EVP) rule requiring that at least 10 individuals have the event of interest for every predictor variable included in the model.33 After excluding variables with missingness >10%, very unbalanced distributions, only available for a short period, or highly correlated with other factors included, we selected 7 variables as predictors, including maternal race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, Hispanic any race, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, other), maternal age at childbirth (continuous), parity (0, 1, or 2+), gestational age in weeks (preterm birth <37 weeks, term births ≥ 37 weeks), birthweight in grams (1499 or less, 1500–2499, 2500–3999, 4000+), child’s birth year (1983–1991, 1992–1996, 1997–2001, 2002–2011), and maternal education in years (≤8, 9–11, 12, 13–15, 16+).

Statistical analysis

As the outcome is binary, we utilized a stepwise logistic prediction model for model specification and estimation. We fitted a full model and then performed backward selection to generate a simplified model estimating coefficients with maximum likelihood methods. Model performance was assessed using two criteria: calibration and discrimination. We fitted a calibration plot and used calibration plot intercept and slope to describe the model fit. We reported accuracy, area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) and 95% confidence interval (CI), sensitivity, specificity, and sample-level positive predicted value (PPV) and negative predicted value (NPV) to evaluate the ability of our model to classify outcomes correctly. The threshold of classifying smokers vs. non-smokers was determined by the “closest.topleft” method, which sets the optimal threshold to be the point closest to the top-left part of the plot representing perfect sensitivity or specificity. Internal validation was performed with bootstrap methods and accuracy was reported.

To assess the external validity of the model, we obtained data from the Environment and Pregnancy Outcomes Study (EPOS).34 EPOS is a case-control study nested within the 2003 birth cohort of all women residing in Los Angeles County. Preterm birth and low birth weight cases and controls matched by birth month and zip code were randomly selected from 111 zip codes. A total of 2543 subjects were enrolled in EPOS with a response rate of 40%. In addition to variables on birth certificates, EPOS collected information on lifestyle factors including smoking status (pregnancy smoker, former smoker, never smoker). There were 2493 subjects without missing information in EPOS. We conducted sensitivity analysis limiting our data to children born in 2003 and compared the model performances in this 2003 subset with information provided in EPOS.

We performed additional sensitivity analyses to examine model performance in different settings. To assess whether additional predictors only available starting in 1989 would enhance model performance, we added ‘month when mothers started prenatal care’ and ‘neonatal intensive care unit admission’ as predictors. Given the large drop in smoking prevalence across the study period, we split the sample into birth year ≤ 1996 vs. > 1996 and tested model performance during the earlier period with high smoking rates versus the later period.

Missing data

We excluded candidate predictors missing data in >10% of the sample to minimize possible misclassification when imputing missing values for predictors. Missing values were imputed with the R package “missForest”, a Random Forest algorithm based non-parametric imputation method, with 4 iterations.

Ethics approval

Human subject permissions were obtained from the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of North Texas.

Results

Overall, 149 out of 894 women were smokers according to our criteria, including 17 mothers identified by self-report (N=2 from 2007–2011) or having tobacco-related pregnancy complications reported on the birth certificate (N=15 mothers from 1989–2005) (for demographics see Table 1). Smokers were more often White non-Hispanic (47.0% among smokers vs. 31.3% among non-smokers) or Black (10.1% among smokers vs. 5.1% among non-smokers) and less likely to be Hispanic (33.6% among smokers vs. 49.9% among non-smokers) or Asian (7.4% among smokers vs. 11.0% among non-smokers), more often <29 years of age when the index child was born (69.8% among smokers vs. 61.6% among non-smokers), living in low to medium socioeconomic status (SES) neighbourhoods (77.1% among smokers vs. 70.6% among non-smokers), and with high school graduation as the highest education (72.5% among smokers vs. 55.3% among non-smokers). Children whose mothers were smokers were less likely to be firstborn (37.6% among smokers vs. 42.2% among non-smokers) and born after the year 2002 (10.1% among smokers vs. 41.1% among non-smokers), but more likely to be male (56.4% among smokers vs. 47.4% among non-smokers). Preterm births were similarly distributed among smoking mothers and non-smokers in our population (9.2% vs. 9.9%) based on small numbers.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population (N = 894)

| Non-smoker (N=745) | Smoker (N=149) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Birth year | ||

| 1983–1991 | 147 (19.7%) | 84 (56.4%) |

| 1992–1996 | 145 (19.5%) | 35 (23.5%) |

| 1997–2001 | 147 (19.7%) | 15 (10.1%) |

| 2002–2011 | 306 (41.1%) | 15 (10.1%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 355 (47.7%) | 84 (56.4%) |

| Female | 390 (52.3%) | 65 (43.6%) |

| Birthweight | ||

| 1499 g or less | 10 (1.3%) | <5 |

| 1500–2499 | 26 (3.5%) | 15 (10.1%) |

| 2500–3999 | 624 (84.0%) | 118 (79.2%) |

| 4000 + | 83 (11.2%) | 14 (9.4%) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 |

| Maternal age | ||

| <20 | 82 (11.0%) | 18 (12.1%) |

| 20–24 | 182 (24.4%) | 42 (28.2%) |

| 25–29 | 195 (26.2%) | 44 (29.5%) |

| 30–34 | 179 (24.0%) | 35 (23.5%) |

| 35+ | 107 (14.4%) | 10 (6.7%) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 233 (31.3%) | 70 (47.0%) |

| Hispanic | 372 (49.9%) | 50 (33.6%) |

| Black | 38 (5.1%) | 15 (10.1%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 82 (11.0%) | 11 (7.4%) |

| Other | 20 (2.7%) | <5 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 314 (42.2%) | 56 (37.6%) |

| 1 | 230 (30.9%) | 37 (24.8%) |

| 2+ | 200 (26.9%) | 56 (37.6%) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Preterm birth | ||

| Preterm | 71 (9.9%) | 13 (9.2%) |

| Term | 646 (90.1%) | 129 (90.8%) |

| Missing | 28 | 7 |

| Census-based neighbourhood SES level | ||

| 1 (low) | 161 (21.7%) | 34 (22.8%) |

| 2 | 208 (28.1%) | 40 (26.8%) |

| 3 | 154 (20.8%) | 41 (27.5%) |

| 4 | 116 (15.7%) | 20 (13.4%) |

| 5 (high) | 102 (13.8%) | 14 (9.4%) |

| Missing | 4 | 0 |

| Maternal education | ||

| 8 or fewer years | 80 (11.9%) | 12 (11.8%) |

| 9–11 years | 137 (17.9%) | 23 (22.5%) |

| 12 years | 195 (25.5%) | 39 (38.2%) |

| 13 to 15 years | 134 (17.5%) | 21 (20.6%) |

| 16 or more years | 128 (16.8%) | 7 (6.9%) |

| Missing | 71 | 47 |

EPOS data information is reported in eTable 1. Questionnaire-based pregnancy smoking prevalence was approximately 5% in EPOS.

Out of the 7 predictors entered into the logistic model for smokers (being positive for any of the smoking indicators), five remained in the final model. Important predictor variables were identified based on the maximum likelihood ratio in the logistic regression. They were maternal race/ethnicity, maternal education, child birth year, parity, and birthweight, in descending order of importance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Maternal smoking logistic regression prediction model using birth data, outcome defined as having any of the smoking indicators (N = 894)

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Hispanic | 0.36 (0.20, 0.64) |

| Black | 1.14 (0.52, 2.41) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.58 (0.26, 1.20) |

| Other | 0.93 (0.20, 3.26) |

| Maternal Education | |

| 8 or fewer years | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 9–11 years | 1.38 (0.69, 2.80) |

| 12 years | 1.06 (0.50, 2.24) |

| 13 to 15 years | 0.73 (0.33, 1.64) |

| 16 or more years | 0.22 (0.07, 0.62) |

| Birth Year | |

| 1983–1991 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1992–1996 | 0.46 (0.28, 0.74) |

| 1997–2001 | 0.18 (0.09, 0.33) |

| 2002–2011 | 0.09 (0.05, 0.16) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1 | 0.90 (0.54, 1.46) |

| 2+ | 1.86 (1.17, 2.97) |

| Birth Weight | |

| 1499 g or less | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1500–2499 | 2.85 (0.48, 24.80) |

| 2500–3999 | 0.99 (0.19, 7.77) |

| 4000 + | 0.68 (0.12, 5.68) |

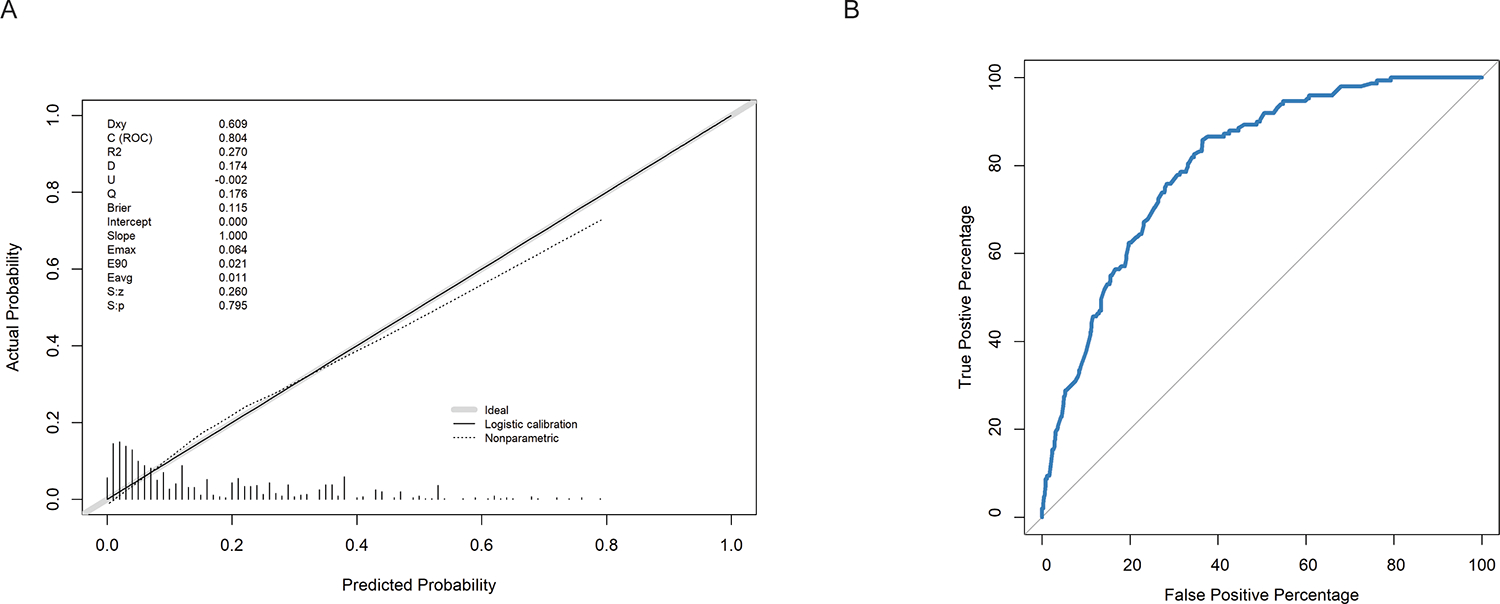

We selected the optimal threshold to classify smokers vs. non-smokers and evaluated the model performance in the training, bootstrapped internal validation, and external validation data sets (Table 3 and Figure 1). The optimal thresholds approximately equalled the prevalence of the outcome in each set. The overall accuracy and AUC were approximately 0.7–0.8 in all 3 samples. When adjusting the threshold to assess the maximum sensitivity or specificity while the other is better than chance (>0.5), we reached a maximum sensitivity of 0.91 and a maximum specificity of 0.86.

Table 3.

Performance of the maternal smoking prediction model using the optimal threshold when classifying probabilities to a binary outcome

| Metrics | Training set | Bootstrapped set | External validation set (EPOS data) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Optimal threshold | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| Accuracy | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.67 |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.81 (0.77, 0.84) | 0.81 (0.77, 0.84) | 0.69 (0.64, 0.74) |

| Sensitivity | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.65 |

| Specificity | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.67 |

| PPV | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.09 |

| NPV | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

Figure 1.

Model performance in the training set. 1A) Calibration plot of the prediction model in the training set. 1B) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the prediction model in the training set.

Adding additional predictors into the model did not appreciably enhance the discrimination performance compared with the final stepwise model selected (AUC 0.81 vs. 0.81). eTable 2 shows the performance of our model in 3 validation data sets containing children born in different time periods. We reached a higher AUC of 0.79 in a subgroup with lower smoking prevalence than when smoking was more prevalent (AUC=0.66). In the validation data set limited to births in 2003, two mothers were identified as smokers and both were correctly classified by the model. Among non-smokers, 36 out of 46 were correctly classified, which yielded an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI 0.77, 1.00).

Comment

Principal findings

Our study utilized self- and provider-reported birth registry data on maternal smoking in pregnancy in combination with smoking biomarker data from neonatal blood spots and built a maternal tobacco use in late pregnancy prediction model with variables from birth certificates. Five demographic characteristics predicted maternal pregnancy smoking in our sample. Compared with non-smokers, smoking mothers were more often White non-Hispanic, less educated, had children in the earlier period, multipara, and had lower weight infants. This model can be used to predict maternal smoking in epidemiologic studies.

Strengths of the study

Strengths of our study include developing a smoking prediction model that is validated, easy to apply, and with a relatively good discrimination performance comparable with other smoking prediction models. Utilizing our model may enhance the use of existing birth data by helping to predict maternal smoking status missing on many birth certificates due to changes in data collection or lack of reporting and to obtain a more reliable proxy for this important confounding variable needed for adjustment in many maternal and child health studies.

Limitations of the data

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, although much more reliable than self-reported smoking, the gold standard for our smoking outcome still is an imperfect measure. Neonatal dried blood spots are typically collected from the infant during the postpartum hospital stay, or by trained midwives for out-of-hospital births, though the latter accounts for <1% of California births.35, 36 Only if the mother smoked close to giving birth or after birth and attempted breast feeding would we have been able to capture smoking in neonatal biomarkers. In California, 67%–86% of mothers attempted any breast feeding from 2004 to 2008, while as many as 90% initiated breast feeding in 2010.37, 38 After smoking a cigarette, about 10% of its nicotine and nicotine metabolites (cotinine, hydroxycotinine, and cotinine N-oxide) pass through the epithelial cells of mammary glands into breast milk. Prolonged labour may also affect the transmission of nicotine metabolites from maternal blood to offspring due to its short half-life, but we expect that effect to be minimal as less than 1% of women in our sample had prolonged labour. In addition, although most of the nicotine metabolites detected were expected to come from active smoking, we could not differentiate the sources. Second, we had to eliminate variables that may predict pregnancy smoking for various reasons. Adding more predictors might have helped the model to achieve a better AUC but the model would become less universally applicable. Third, the EPOS validation data set we relied on only captured births in 2003 in Los Angeles County and had a 40% response rate and may have been subject to tobacco underreporting due to stigma. However, we previously conducted extensive analyses comparing responders, non-responders, and the overall birth cohort and observed few differences in the characteristics of interest to this study.34 In addition, the EPOS data is representative of most of the LA population as it was sampled from birth records in a population-based manner rather than being a select sample of women recruited from prenatal clinics and hospitals.39

Interpretation

Research studies of maternal and child health often rely on registry data, especially from state-administered birth certificates. Nicotine metabolites, cotinine and hydroxycotinine, have been used as biomarkers of maternal smoking in newborn dried blood spots but these are resource-intensive and costly to analyze. We combined the metabolite-derived biomarker measures and the data on birth certificates to build a prediction model that can help future studies using state-based birth registry data to predict maternal smoking status. The model can be applied to registry-based studies, even for years when maternal smoking was not collected on the birth certificate. In the United States and globally, pregnancy smoking prevalence and uptake are higher among disadvantaged groups who usually have low socioeconomic status (SES) and/or are related to racial/ethnic disparities.40–42 In addition, smoking co-occurs with other environmental or lifestyle exposures or adverse health conditions, such as ambient air pollution, maternal underweight, small gestational age, and drug abuse.43, 44 Thus, lack of ascertainment of smoking as well as other unhealthy lifestyle characteristics might lead to bias in effect estimates due to uncontrolled confounding. Therefore, our study may enhance the use of existing birth data by helping to predict maternal smoking status missing on many birth certificates due to changes in data collection or lack of reporting and to obtain a more reliable proxy for this important confounding variable needed for adjustment in many maternal and child health studies.

Moreover, our model is validated and easy to apply to other registry studies that collect the same data elements. We used stepwise logistic regression to predict a binary maternal smoking variable and obtained an overall discriminant accuracy of around 70%−80% for apparent model performance, internal validation, and external validation. Previous studies identified pregnancy smoking or pregnancy smoking cessation predictors using univariate analysis usually aimed to identify clinically meaningful intervention groups. Some also had detailed smoking behaviour information available as predictors such as the frequency, amount, and duration of smoking and even second-hand smoke exposure.41, 45, 46 However, these models were not validated against internal and external test data and these smoking predictors are rarely if ever available in routine register-based data, which limits the transportability of these models outside the study population. This applies to a study that randomly split the sample into a training and test data set and reached an overall percentage of correct smoking status classification of 76%. Their model used predictors such as interview-based smoking behaviour variables and, thus, cannot apply to studies with missing maternal smoking information.46 With the purpose of having the model as transportable as possible, we selected a limited number of predictor variables that are routinely reported on birth certificates.47 While we do not have the capability to validate the model using out of state data, our model reached the level 2 of validation according to the Hierarchy of External Validity for Predictive Systems.48 Although the external performance may vary across states, applying the model to other jurisdictions is possible but external validity of the model needs to be further assessed in such instances.

Researchers have shown that demographic characteristics including maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, maternal education, parity, prenatal care, household income, unemployment, and antenatal stress are related to maternal smoking.40–42, 49 In addition, maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy increases the risk for pregnancy complications and poor pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery, restricted fetal growth, and low birthweight.42, 50 Our model identified the same predictors that were available to us on birth certificates and overlapped with this list but we reached good prediction performance with fewer predictors.

Our predictor selection process balanced adding all potential predictors and making the model easy to apply in future studies. We did not include SES or prenatal care information (month when prenatal care began, principal source of payment for prenatal care, number of prenatal care visits) in the model input. Although smokers were more likely to live in neighbourhoods with lower SES, census-based neighbourhood SES is not available on the birth certificate and was created for our sample after an extensive geocoding process. Moreover, SES of neighbourhoods changes over time and one would have to generate a time-varying SES variable for usage in future studies. We also decided to leave out potential predictors like month of initiation of prenatal care, pregnancy complications and labour complications because they were only collected for a short period or had very few events recorded, including complications such as placenta previa, abruption placenta, premature rupture of membranes, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. We added month of initiation of prenatal care and neonatal intensive care unit admission as predictors in a sensitivity analysis as they had relatively few missing data points and an adequate number of events, but the model performance was very similar to our selected model. One variable that was eliminated during model simplification (from full to final model after stepwise reduction) was preterm birth. This may be due to the fact that it is highly correlated with birthweight, which also was more complete in our study.

Our model has a relatively good discrimination performance comparable with other smoking prediction models and is easy to apply in birth data. A study that used a much more complex decision tree model and a multinomial logistic regression model to characterize the smoking patterns among seniors obtained classification accuracies of 0.67 and 0.52, respectively.24 Another study employed machine learning methods to predict smoking cessation and their best model reached an accuracy of 0.64 and an AUC of 0.66.51 The performance of our model was the highest in the training set and slightly lower in the external validation set. Moreover, when comparing subsets for earlier and later years, the model performed was better among children born after 1996 when smoking became less prevalent compared to earlier years (according to the negative and positive predictive values).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we constructed a prediction model using birth certificate data to predict maternal smoking reaching an AUC of 0.81. The model may benefit future studies that employ birth registry data. It can help to improve adjustment for maternal smoking and guide clinical interventions to reduce smoking. Further studies with multiple diverse validation sets to test the model generalizability may be needed and we would welcome other research teams adapting our model in their settings.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

Study question:

Can researchers use birth certificate variables to predict maternal pregnancy smoking?

What’s already known:

Many studies have linked maternal smoking to adverse birth outcomes and maternal smoking is a key variable in research on maternal and prenatal health. However, assessing maternal smoking status in interviews or from birth certificates is not always available and can underestimate true smoking rates due to the stigma attached.

What this study adds:

We built a prediction model for maternal tobacco smoking in pregnancy based on birth certificate information using a combination of self- or provider-reported smoking and biomarkers (smoking metabolites) in neonatal blood spots as the alloyed gold standard. This easy-to-apply model may benefit future birth registry-based studies when there is missing maternal smoking information.

Acknowledgements

The biospecimens and data used in this study were obtained from the California Biobank Program (SIS request number 565). The California Department of Public Health is not responsible for the results or conclusions drawn by the authors of this publication.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (grant# 24RT-0033H, T29DT0485) and the US National Institutes of Health (R21ES019986, R21ES018960, R03CA252788).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

None declared.

Data availability statement

Data availability is under the regulation of the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

References

- 1.Reports of the Surgeon General. In: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen AR, Akomolafe TO, McGalliard Z, Belle-Isle L, Zhang J. Striving to Meet Healthy People 2020 Objectives: Trend Analysis of Maternal Smoking. Public Health Reports. 2018; 133:644–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keyes KM, March D, Link BG, Chilcoat HD, Susser E. Do socio-economic gradients in smoking emerge differently across time by gender? Implications for the tobacco epidemic from a pregnancy cohort in California, USA. Social Science and Medicine. 2013; 76:101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ, Li DK, Hakimian S, Kane S, Corley DA. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Large Community-Based Study From Northern California. Gastroenterology. 2007; 133:1106–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Y, Li X, Benmarhnia T, Chen J-C, Avila C, Sacks DA, et al. Exposure to air pollutant mixture and gestational diabetes mellitus in Southern California: Results from electronic health record data of a large pregnancy cohort. Environment International. 2022; 158:106888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollack H, Lantz PM, Frohna JG. Maternal smoking and adverse birth outcomes among singletons and twins. American Journal of Public Health. 2000; 90:395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hackshaw A, Rodeck C, Boniface S. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review based on 173 687 malformed cases and 11.7 million controls. Human Reproduction Update. 2011; 17:589–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heck JE, Contreras ZA, Park AS, Davidson TB, Cockburn M, Ritz B. Smoking in pregnancy and risk of cancer among young children: A population-based study. International journal of cancer. 2016; 139:613–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Himes SK, Stroud LR, Scheidweiler KB, Niaura RS, Huestis MA. Prenatal Tobacco Exposure, Biomarkers for Tobacco in Meconium, and Neonatal Growth Outcomes. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2013; 162:970–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickett KE, Rathouz PJ, Kasza K, Wakschlag LS, Wright R. Self-reported smoking, cotinine levels, and patterns of smoking in pregnancy. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2005; 19:368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ventura SJ, Hamilton BE, Mathews TJ, Chandra A. Trends and Variations in Smoking During Pregnancy and Low Birth Weight: Evidence From the Birth Certificate, 1990–2000. Pediatrics. 2003; 111:1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietz PM, Adams MM, Kendrick JS, Mathis MP. Completeness of ascertainment of prenatal smoking using birth certificates and confidential questionnaires: Variations by maternal attributes and infant birth weight. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998; 148:1048–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howland RE, Mulready-Ward C, Madsen AM, Sackoff J, Nyland-Funke M, Bombard JM, et al. Reliability of Reported Maternal Smoking: Comparing the Birth Certificate to Maternal Worksheets and Prenatal and Hospital Medical Records, New York City and Vermont, 2009. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015; 19:1916–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardy AH, Seppälä T, Lillsunde P, Kataja JM, Koskela P, Pikkarainen J, et al. Objectively measured tobacco exposure during pregnancy: neonatal effects and relation to maternal smoking. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1993; 100:721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J, Pearl M, Jacob Iii P, DeLorenze GN, Benowitz NL, Yu L, et al. Levels of cotinine in dried blood specimens from newborns as a biomarker of maternal smoking close to the time of delivery. American journal of epidemiology. 2013; 178:1648–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koskela P, Anttila T, Bjørge T, Brunsvig A, Dillner J, Hakama M, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection as a risk factor for invasive cervical cancer. International journal of cancer. 2000; 85:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki S, Braimoh TS, Yila TA, Yoshioka E, Kishi R. Self-reported tobacco smoke exposure and plasma cotinine levels during pregnancy – A validation study in Northern Japan. Science of the Total Environment. 2011; 412–413:114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wall MA, Johnson J, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Cotinine in the serum, saliva, and urine of nonsmokers, passive smokers, and active smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 1988; 78:699–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy SE, Wickham KM, Lindgren BR, Spector LG, Joseph A. Cotinine and trans 3′-hydroxycotinine in dried blood spots as biomarkers of tobacco exposure and nicotine metabolism. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2013; 23:513–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob P, Yu L, Duan M, Ramos L, Yturralde O, Benowitz NL. Determination of the nicotine metabolites cotinine and trans-3′-hydroxycotinine in biologic fluids of smokers and non-smokers using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry: Biomarkers for tobacco smoke exposure and for phenotyping cytochrome P450 2A6 activity. Journal of Chromatography B. 2011; 879:267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dempsey D, Jacob III P, Benowitz NL. Nicotine metabolism and elimination kinetics in newborns. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2000; 67:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markaki M, Tsamardinos I, Langhammer A, Lagani V, Hveem K, Røe OD. A validated clinical risk prediction model for lung cancer in smokers of all ages and exposure types: a HUNT study. EBioMedicine. 2018; 31:36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dukic VM, Niessner M, Benowitz N, Hans S, Wakschlag L. Modeling the relationship of cotinine and self-reported measures of maternal smoking during pregnancy: a deterministic approach. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007; 9:453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon SS, Kang S-Y, Jitpitaklert W, Kim SB. Decision tree models for characterizing smoking patterns of older adults. Expert Systems with Applications. 2012; 39:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models. Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genetic Disease Screening Program. California Department of Public Health2021 [updated November 17, 2021; cited 2022 March 22]; Available from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DGDS/Pages/GDSP-Program-and-Services.aspx.

- 27.Newborn Screening Program. California Department of Public Health2023 [updated August 16, 2023; cited 2023 August 30]; Available from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DGDS/Pages/nbs/default.aspx.

- 28.Liu KH, Nellis M, Uppal K, Ma C, Tran V, Liang Y, et al. Reference Standardization for Quantification and Harmonization of Large-Scale Metabolomics. Analytical Chemistry. 2020; 92:8836–8844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He D, Yan Q, Uppal K, Walker DI, Jones DP, Ritz B, et al. Metabolite Stability in Archived Neonatal Dried Blood Spots Used for Epidemiological Research. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2023; 192: 1720–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uppal K, Soltow QA, Strobel FH, Pittard WS, Gernert KM, Yu T, et al. xMSanalyzer: automated pipeline for improved feature detection and downstream analysis of large-scale, non-targeted metabolomics data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013; 14:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebrahim SH, Floyd RL, Merritt RK, 2nd, Decoufle P, Holtzman D. Trends in pregnancy-related smoking rates in the United States, 1987–1996. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000; 283:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He D, Huang X, Uppal K, Coleman AL, Walker DD, Ritz B, et al. Biomarkers of Maternal Smoking and the Risk of Retinoblastoma in Offspring. Retina. 2023; 43:481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shipe ME, Deppen SA, Farjah F, Grogan EL. Developing prediction models for clinical use using logistic regression: an overview. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2019; 11:S574–S584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritz B, Wilhelm M, Hoggatt KJ, Ghosh JKC. Ambient Air Pollution and Preterm Birth in the Environment and Pregnancy Outcomes Study at the University of California, Los Angeles. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007; 166:1045–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newborn Screening Process. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Health Resources & Services Administration2021 [updated December 2021]; Available from: https://newbornscreening.hrsa.gov/newborn-screening-process#:~:text=If%20your%20baby%20has%20an,before%20your%20baby%20is%20born. [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDorman MF, Mathews T, Declercq E. Trends in out-of-hospital births in the United States, 1990–2012. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breastfeeding Data and Reports. California Department of Public Health; 2019. [cited 2022 March 22]; Available from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DMCAH/Breastfeeding/Pages/Data.aspx.

- 38.Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state - National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004–2008. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010; 59:327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghosh JKC, Wilhelm MH, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lombardi CA, Ritz BR. Paternal support and preterm birth, and the moderation of effects of chronic stress: a study in Los Angeles County mothers. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2010; 13:327–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondracki AJ. Prevalence and patterns of cigarette smoking before and during early and late pregnancy according to maternal characteristics: the first national data based on the 2003 birth certificate revision, United States, 2016. Reproductive health. 2019; 16:142–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Wolff MG, Backhausen MG, Iversen ML, Bendix JM, Rom AL, Hegaard HK. Prevalence and predictors of maternal smoking prior to and during pregnancy in a regional Danish population: a cross-sectional study. Reproductive health. 2019; 16:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. Trends in Smoking Before, During, and After Pregnancy — Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 Sites, 2000–2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries. 2009; 58:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyd CJ, Esteban McCabe S, Teter CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription pain medication by youth in a Detroit-area public school district. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006; 81:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nohr EA, Vaeth M, Baker JL, Sørensen TIA, Olsen J, Rasmussen KM. Pregnancy outcomes related to gestational weight gain in women defined by their body mass index, parity, height, and smoking status. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009; 90:1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey BA. Factors predicting pregnancy smoking in Southern Appalachia. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2006; 30:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodby LL, Windsor RA, Snyder SW, Kohler CL, Diclemente CC. Predictors of smoking cessation during pregnancy. Addiction. 1999; 94:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Specifications for Collecting and Editing the United States Standard Certificates of Birth and Death−-2003 Revision. National Center for Health Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999; 130:515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Härkönen J, Lindberg M, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Scheinin NM. Education is the strongest socio-economic predictor of smoking in pregnancy. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2018; 113:1117–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaddoe VWV, Troe E-JWM, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EAP, et al. Active and passive maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight and preterm birth: the Generation R Study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2008; 22:162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lai C-C, Huang W-H, Chang BC, Hwang L-C. Development of Machine Learning Models for Prediction of Smoking Cessation Outcome. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is under the regulation of the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.