Abstract

Of all the different risk factors known to cause cardiovascular disease (CVD), age and sex are considered to play a crucial role. Aging follows a continuum from birth to death, and therefore it inevitably acts as a risk for CVD. Along with age, sex differences have also been shown to demonstrate variations in immune system responses to pathological insults. It has been widely perceived that females are protected against myocardial infarction (MI) and the protection is quite apparent in young vs. old women. Acute MI leads to changes in the population of myeloid and lymphoid cells at the injury site with myeloid bias being observed in the initial inflammation and the lymphoid in the late-resolution phases of the pathology. Multiple evidence demonstrates that aging enhances damage to various cellular processes through inflamm-aging, an inflammatory process identified to increase pro-inflammatory markers in circulation and tissues. Following MI, marked changes were observed in different sub-sets of major myeloid cell types viz., neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. There is a paucity of information regarding the tissue and site-specific functions of these sub-sets. In this review, we highlight the importance of age and sex as crucial risk factors by discussing their role during MI-induced myelopoiesis while emphasizing the current status of myeloid cell sub-sets. We further put forth the need for designing and executing age and sex interaction studies aimed to determine the appropriate age and sex to develop personalized therapeutic strategies post-MI.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, age, sex, myelopoiesis, immunity

1. Cardiovascular Disease, Causes, and Risk Factors

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of death in the United States [1]. MI, also known as “heart attack” is caused by decreased or complete cessation of the blood flow to a portion of the myocardium due to partial or complete blockage of one or more coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart [2]. Prolonged ischemia in the affected region can lead to permanent tissue death (infarction) primarily through necrosis or apoptosis, and autophagy has also been associated with cell death [3]. Several traditional risk factors influence its initiation and progress. While some of these factors are modifiable, others are not. Though many modifiable risk factors are recognized, majorly five traditional risk factors that are associated with the development of CVDs are diabetes, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia [4]. Alongside, several non-modifiable risk factors include sex (and also gender in human beings), old age, hereditary or genetic make-up, family history of heart disease, race, etc. were also demonstrated to associate with CVDs [4]. Among these, age and sex represent the most promising risk factors in developing heart disease. Over the years, studies involving different age and sex groups have demonstrated differences in the cardiovascular outcomes. Here we review literature in this area and while doing that, we propose the need for extensive age and sex interaction studies. Such interactions would help the researchers in developing personalized therapeutics tailored towards patient-specific needs. We also aim to review key factors that should be considered while designing age-sex interaction studies.

2. Age and sex as emerging cardiovascular risk factors

2.1. Age and age linked-clonal hematopoiesis.

As an uncontrollable risk factor, aging, increases the risk of CVD due to incremental acquisition of several risk factors [5]. Five major traditional risk factors (i.e., diabetes, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) including frailty are key to note here. For e.g., the prevalence of diabetes being reported to be remarkable is in those aged 65 years or over. Older diabetics were shown to possess significantly higher risk of vascular complications, owing to chronic disease conditions [6, 7]. In similar line with age-linked diabetes and obesity, presence of frailty has been shown to predict CVD incidence to a major extent in older adults [8]. Frailty is determined to be a direct consequence of weekend physiological reserve, and its presence demonstrates greater vulnerability to chronic illness [9]. Central adiposity and inflammation has been shown to be crucial in positive correlation of this phenotype with CVD [10]. Studies based on Framingham Heart Study showed that the absence of traditional risk factors is associated with a reduction in the risk of CVD as well as decreased age-associated co-morbidities and mortality [11]. On the contrary, about 60% of older patients with atherosclerotic CVD haven’t either demonstrated the presence of all 5 traditional risk factors [12]. These patients had atleast 1 conventional risk factor, with smoking being the most common [12]. Also, evidences suggest that middle-age individuals with low CVD risk based on conventional risk factor were found to exhibit subclinical atherosclerosis [13, 14]. These findings describe the importance of other age-dependent risk factors and their contribution to CVD development [15].

Literature suggests that clonal hematopoiesis (CH); an aging-linked phenomenon is one of the key drivers behind aging being an independent risk factor [16–18]. It involves somatic mutations being incurred in hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells during the process of organismal aging [17]. Though most of the somatic mutations that humans accumulate in all cells throughout the body during lifetime have little phenotypic consequence, mutations in certain genes called driver genes confer a selective growth advantage allowing cells to outcompete neighboring cells and clonally expand. This process will account for a greater proportion of the population within the bone marrow [16, 17]. A relatively higher proinflammatory phenotype was observed in the progeny leukocytes of such clonally expanded cells, which was attributed to the maintenance of mutations in the driver genes [16]. With recent estimates suggesting a high turnover rate of hematopoietic cell generation nearly about 2.6×1011 cells per day [19], it is not surprising to predict that the detectable levels of CH become nearly ubiquitous as age advances [20]. Commonly associated CH driver genes include DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A), ten eleven translocation 2 (TET2), janus kinase 2 (JAK2), additional sex combs like 1 (ASXL1), protein phosphatase Mn2+/Mg2+-dependent 1D (PPM1D), and tumor suppressor protein 53 (TP53) [17]. Their impact in the context of CVD became quite evident when healthy individuals with acquired clonal mosaicism in the hematopoietic system showed higher prevalence for vascular complications of diabetes as well as greater incidence of atherosclerotic conditions and CVD-related deaths [21, 22]. This was further supported by the evidence that CH carriers with mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, and JAK2 were individually associated with an increased incidence of coronary heart disease with higher coronary-artery calcification burden [23]. At the molecular level, importance of NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasome in CH induced CVD incidence was demonstrated in a murine model, where partial bone marrow reconstitution with TET2- deficient cells in low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice was sufficient to exacerbate atherosclerosis [15]. TET2- deficient macrophages in the study demonstrated an increased NLRP3 inflammasome mediated by IL-1β secretion [15]. Similarly, monocytes of HF patients harboring DNMT3A driver mutations exhibited markedly increased expression of inflammatory genes including NLRP3 inflammasome [24]. All these evidence clearly indicate the importance of aging and CH in CVD.

2.2. Sex, sex-based hormones and sex chromosomes

For many decades, research on CVD was focused primarily on men but CVD is also a leading cause for death in women in the United States. The risk for the disease increases significantly in men beyond 45 years and 55 years or older in women [25, 26]. An increasing number of studies focusing on CVDs have shown that nearly half of the heart attack victims are women with 7.5 times more likely to die from heart attacks than breast cancer. A woman’s risk increases when her ovaries are removed or undergoing post-menopausal stages [27–29]. Along with traditional risk factors like hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity and overweight, and physical inactivity; women prone to CVD also present some non-traditional risk factors such as preterm delivery, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes, autoimmune disease, breast-cancer treatment and depression [4, 27]. These differences further extend to transgender and gender diverse (TGD) populations. Multivariate analyses of self-reported cross-sectional data revealed that transgender men show a >2-fold and 4-fold increase in the prevalence of MI compared with cisgender men and women, while transgender women show a >2-fold increase in the prevalence of MI compared with cisgender women [30]. Till date, multiple theories have been presented to determine the possible reasons behind the differences in the aging processes in men and women [31–34]. Two best described explanations are differences in the nature of sex chromosomal driven differences and sex-specific hormone driven mechanisms in biology [35].

Most common group of sex steroids are androgens (testosterone) in men, while in women estrogen (estradiol, estrone, and estriol) and progestogens are highly abundant [35]. Differences in the biological levels of these steroids (i.e. estrogen or testosterone) starts as early as in utero and continue lifelong [35]. Such differences influence the neuroanatomy and neurochemistry in a developing fetus [35]. In addition to giving rise to dimorphic phenotypic and sexual characteristics, differences in perinatal hormonal exposure can also contribute to sex-specific metabolic programming later in life, manifested with differences in risk profiles for metabolic diseases [36]. In females, apart from after birth, increased surge in estrogen is also observed at puberty, with the levels varying during each menstrual cycle and a drastic drop at menopause [37]. While in males, elevated levels of testosterone in utero is followed by further surge during puberty, while staying relatively stable throughout adulthood [37]. Unlike menopause in women, andropause in men is more difficult to define owing to an annual decrease rate of only about 1% in testosterone levels [38]. The symptoms of decreasing testosterone levels and the threshold at which they manifest greatly vary among individuals with many men being asymptomatic despite lower levels of the hormone [38]. Though subtle differences between male and female sex hormones were observed all throughout the life, remarkable differences were noticed in adulthood [39] (Fig. 1), which is preceded by a hormonal development (peak up) phase seen during the time of puberty and a follow-up old age phase showing decreased levels [39] (Fig. 1). Literature pertaining to immune system indicates that women in adulthood have a better immune health compared to male counterparts [40, 41]. Not only do females have higher numbers of T cells (particularly T helper cells), macrophages [42], and B cells [43]; these higher numbers are reciprocated as potent responses with greater antibody titers and inflammatory activities [44–47]. For e.g., their leukocytes show a greater capacity for mobilization to sites of chemotaxis and their phagocytes show improved phagocytosis activity [44, 45]. In addition, differences in sex chromosome also account for the differences in immune function [48, 49]. All the discussed facts put forth two important points: 1) Sex-specific changes significantly contribute to aging processes at various phases of organismal life (birth, puberty, adult, and old age), and 2) such changes can occur at all hierarchial levels viz., molecular, cellular, tissue and organ, functional, and whole organism (Fig. 1) [27, 35].

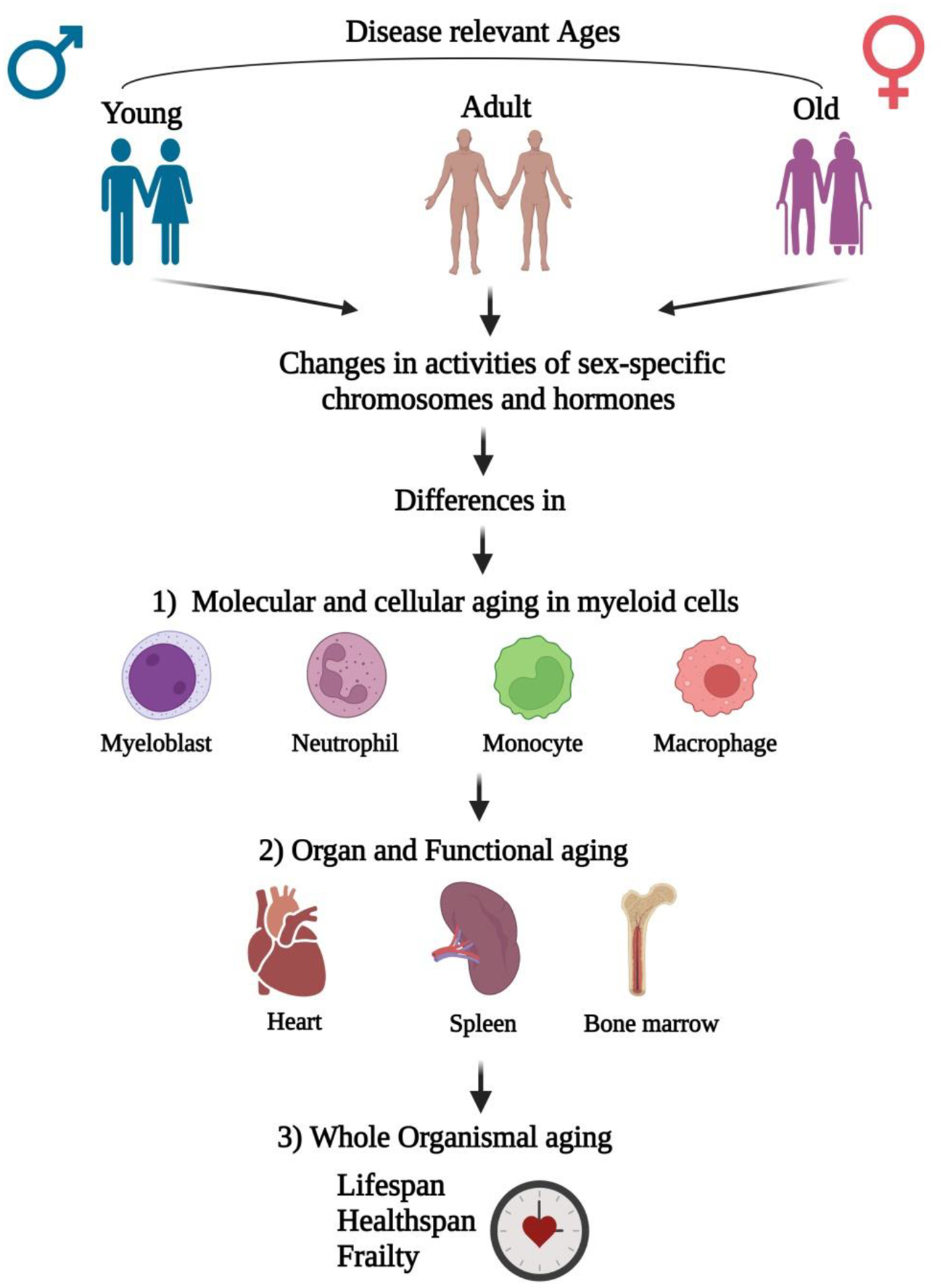

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of sex-based interactions on aging with respect to MI.

Differences in age (young, adult, and aged) manifest with changes in activities of sex-specific chromosomes and hormones. These changes lead to aging differences at three different hierarchal levels; with first being molecular and cellular, second being organ and its functional, and the last at the whole organismal level. Cells that are key to myelopoiesis viz., myeloblasts, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages are those majorly affected at molecular and cellular levels in response to MI injury with heart, spleen, and bone marrow at the organ levels. All such changes accompanied with disease associated co-morbidities may finally lead to whole-organismal aging, which involves decreased life and health spans along with development of frailty.

At the level of DNA, sex differences among men and women are majorly attributed to the differences in their sex-chromosomal makeup. Male-specific Y chromosome is relatively small in size with a limited number of genes that regulate sex determination and spermatogenesis [50]. The impact of the Y chromosome in determining the physiological effects in males was experimented in studies involving susceptibility to the mosaic loss of Y chromosome (mLOY) in the blood. This condition associates a fraction of hematopoietic cells displaying loss of Y chromosomal activity [51]. It is the most prevalent post-zygotic mutation in leukocytes [52] and has been shown to increase in frequency with age [53]. With evolving technology to assess mLOY, it was recently reported that mLOY is detectable in 40% of 70-year-old males and 57% of 93-year-old males [54, 55]. While mosaic loss of the X chromosome in women’s blood cells also happens, this appears to occur less frequently than mLOY and it inclines to preferentially inactive X chromosome [56, 57]. Defects in the X chromosome resulted to early menopause or premature ovarian failure (POF), which is an autoimmune disease [58]. POF was shown to occur in about 1% of the women and is defined as hypergonadotropic ovarian failure if it happens in age prior to 40 years [58]. While it is yet to be determined whether mLOY is a clonal event or it is a common event that is tolerated by leukocytes [17]; its role in cardiac dysfunction was studied [51]. Additionally, studies have reported two other types of mutations viz., mosaic alterations in autosomal chromosomes (mCA) [57] and clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) [59]. mCA in human blood cells refers to a condition that includes losses and gains of sections or entire chromosomes as well as loss of heterozygosity [57]; while CHIP involves mutations in genes recurrently mutated in hematological malignancies [59]. Aging has shown a significant impact on the frequency of occurrence of both mutations (mCA & CHIP) [57, 59]. Studies determined that there exists a dose-dependent relationship between CHIP and CVDs [60], whereas the association of mCAs with CVDs has received considerably less attention over years [17]. This evidence describe the importance of sex chromosomes in aging with the effects being pronounced due to increased genomic instability as we age.

3. Age and sex differences induced cardiovascular changes during MI (I/R)

3.1. Aging and associated changes

Aging is a condition that is related to a gradual decline in cardioprotective systems [61]. With aging, there are some structural and functional changes in the heart, and each of these can have significant implications for CVD [62]. It results in a significant increase in heart wall thickness [61]. In addition, the heart changes its overall shape with an increase in interventricular septum more than the free wall [61]. All such changes have a significant influence/stress on the cardiac wall [61]. Functionally, the cardiac mechanisms responsible for protection from injury or disease become increasingly defective with age. These increased dysfunctions of the aged heart lead to a progressive increase in CVD [62]. Also, aging is associated with changes in other organ systems that also affect cardiac structure-function [61]. [61–63]. Elderly patients are not only prone to suffer a MI but are more likely to develop heart failure or even die as a consequence [64]. The hypothesis that higher mortality rates are expected in the aged was also observed in a murine model where 18 months old aged mice demonstrated markedly elevated deaths than younger ones within 28 days post-MI [65]. Despite no marked changes being observed in infarct sizes among aged and young mice, aging hearts activated distinct apoptotic pathways, showed more cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and are resistant to anti-apoptotic therapies following MI [65]. The reason behind the lack of differences in infarct sizes in aged mice are possibly attributed to many factors that include life expectancy, survivor effect, fertility, genetic changes, diet, lifestyle, disease states, etc. [65]. Overall, the current state of evidence accounts that aging does increase the chance of post-infarction mortality depending on many factors [66]. As discussed earlier, CH plays significant role in CVDs and MI is not an exception. In permanent LAD ligation model, Tet2 deficiency in hematopoietic cells also shown to worsen late-stage cardiac remodeling and reduced cardiac function with involvement of IL-1β/NLRP3 inflammasome [67].

3.2. Sex and hormonal therapies

Though sex-based cardiovascular anatomy and physiology are comparable, the effects on cardiac electrophysiology and responses to pathological stimuli significantly vary among males and females [68]. The mammalian heart is more susceptible to changes in sex hormones as the myocardium expresses receptors for both androgens and estrogen [69, 70]. There are differences in the risk, timing, severity, and symptoms of heart disease between men and women. Premenopausal women experience lower chances of MI compared to men of the same age and menopausal women [71]. Following MI, female patients demonstrated reduced maladaptive remodeling and improved adaptation changes in the heart wall as evident through less pronounced left ventricle (LV) wall thickening and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [72]. Post-mortem and post-transplantation analyses of the myocardium of female patients revealed lesser cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the peri-infarct area and less necrosis in the cardiac ischemic region [73]. Additionally, studies aimed to understand the effect of sex in mouse models of heart failure and LV remodeling following MI showed that males have a higher incidence of mortality than females [74]. Female mice post-MI exhibited lower left ventricular dilatation and adverse cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, paralleled by a more preserved left ventricular function leading to minimal infarct expansion [75–78]. Furthermore, ovariectomized mice and rats have shown even bigger infarcts and more severe cardiac dysfunction upon I/R than male counterparts, which could be partly rescued by chronic estrogen supplementation [79, 80]. These data suggest the importance of estrogen and its cardioprotective effects. When estrogen levels decline due to menopause, levels of LDL cholesterol increase, and the HDL cholesterol level decreases leading to build up fat and cholesterol in the arteries, contributing to heart failure and stroke [4, 81, 82]. Multiple factors and changes that accompany the transition during menopause in women make them more vulnerable to CVD [28, 83]. Although estrogen contributes to some of the detrimental effects observed during menopause, it is not the only reason or cause of increased CVD [28]. On other hand, several clinical as well as experimental studies indicated aggravated outcomes after I/R owing to low testosterone levels in elderly men. Nevertheless, conflicting results on cardioprotection were observed while using testosterone replacement therapies with some pre-clinical and clinical studies showing beneficial effects and others reporting an inverse relationship [84, 85]. To date, no definite benefits were reported from the studies utilizing testosterone or estrogen replacement therapies in primary or secondary prevention [68]. Estrogen-based hormone therapies were also proven to be unsuccessful in transgenders due to elevated risk for venous thromboembolism [86]. One key reason behind the lack of better outcomes post testosterone therapies in aged MI patients may be attributed to hematopoietic mLOY. Male mice reconstituted with bone marrow cells lacking the Y chromosome displayed increased mortality and age-related profibrotic pathologies including reduced cardiac function [51]. It was observed that cardiac macrophages exhibited polarization towards a more fibrotic phenotype and treatment with a transforming growth factor β1-neutralizing antibody ameliorated cardiac dysfunction in mLOY mice [51]. With the fact that sex-specific alterations were observed in three prominent co-dependent progressive maladaptive remodeling processes post MI viz., hypertrophy, inflammation and fibrosis and as there exist conflicting outcomes utilizing steroids with loss of Y chromosome in men and menopause in women, it is imperative of the necessity to elicit sex including age-based differences in the type and extent of the different remodeling sub-processes [51, 87–89].

Additionally, a few studies explored interactions between sex and age and their combined impact on cardiac outcomes. Johansson et al studied the association of MI with mortality risk in women vs. males, especially at younger ages [90] and found that women below 45 years of age presented an over-representation of hypertension and diabetes before MI. Interestingly, the data revealed no similar and consistent differences between women and men of older ages and no sex differences were found in the recurrence rate of nonfatal reinfarctions [90]. The importance of sex-age interactions was also considered in a study that showed higher mortality of women compared with men after MI which were confined to younger age groups [91]. In another study involving Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Alkhouli M et al., recently investigated sex differences with a focus on ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) outcomes. Regardless of age, women demonstrated a lower incidence of MI (both STEMI and NSTEMI) and a less likelihood of undergoing invasive treatments. However, the detrimental impact of the female sex on most outcomes is age-dependent, with young and middle-aged women suffering the most [92]. While post-MI outcomes were age-specific, the negative impact of the female sex on most outcomes was more pronounced in young and middle-aged women [92]. Findings from ~7 million weighed hospitalizations for AMI indicate that younger women do generally worse and older women do better than their male counterparts [92]. In a nutshell, all the afore-discussed literature reveals that younger age is associated with a lower incidence of MI in women than men. Nevertheless, in cases of younger women suffering from MI events end up with worse outcomes compared to male counterparts. Multitude of the reasons is responsible behind the poorer outcomes in women over men after MI. They include excessive risk of traditional risk factors including socioeconomic influences and prevalence of non-traditional risk factors, the perception that women show low risk for MI resulting in delays in diagnosis and treatment post-MI, time delays to first medical contact and hospital arrival, less likely to undergo invasive testing and treatment, minimal guideline-directed medical therapy [93]. Having said that, it will be scientifically exciting to investigate and evaluate the impact of both sexes at different age groups to achieve a deeper understanding of the health disparities.

4. Role of myeloid cells in response to MI

Cells in the immune system are broadly divided into two types namely myeloid and lymphoid [94]. Myeloid cells include granulocytes, monocytes (the precursor to dendritic cells and macrophages), mast cells and megakaryocytes, while lymphoid cells are natural killer (NK) cells, T cells and B cells [94]. In a healthy adult heart, resident immune cells include B and T cells, mast cells and macrophages [95]. Leukocytes constitute 9% of non-myocyte cells with this number further breaking to 7% myeloid cells (mostly macrophages) and roughly 1% lymphocytes [95]. During acute myocardial injury, participation of cardiac-resident, splenic and bone-marrow-derived immune cells occurs in two cellular phases viz., inflammation and resolution, both of which are critical for effective tissue repair [94]. Within the first 24 h, and up to 3 days post myocardial injury, myeloid cells are responsible for the tissue inflammation while about 5–7 days post-injury, their cellular behavior takes on a reparative phenotype with increased infiltration of lymphoid cells. A gradual induction of an inflammatory response takes place after MI, where early local events in the heart release DAMP’s [96]. These include cytokines and chemokines like monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1/CCL-2), Interleukin IL-1α, IL-6, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 16 (CXCL16), the macrophage-inhibitory factor (MIF) and CXCL12, which recruit leukocytes to the heart [96]. Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages are the three major myeloid cell types participating in inflammation post-MI. Neutrophils are the first-line responders (within 24 hrs. of injury) known to possess dual roles as phagocytes and granulocytes and play a pivotal role by infiltrating massively to the infarct region post-injury [97, 98]. This was evident with bone marrow rapidly shifting to emergency granulopoiesis from steady-state within a few hours after MI and this has been shown to enhance the proliferation of neutrophil precursors to respond to higher demand of neutrophils [99]. Recently, our lab demonstrated the importance of neutrophil alarmins, S100A8 and S100A9, in emergency granulopoiesis [100]. Induction of MI resulted in rapid recruitment of neutrophils, which released S100A8 and S100A9, and these alarmins bind to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) and prime the NLRP3 inflammasome in naive neutrophils to promote interleukin-1β (IL-1β) secretion. Further, IL-1β interacts with its receptor IL-1R on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the bone marrow to stimulate granulopoiesis in a cell-autonomous manner [100, 101]. Initial populations of neutrophils participate in the amplification of tissue injury through monocyte recruitment and by the production of cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, CCL3, and IL-12 [102, 103], while during the resolution phase, they act as an anti-inflammatory switch in macrophages possibly by modulating the local microenvironment, or by programming macrophage behavior from within after efferocytosis [104]. Although they play a crucial role during initial tissue injury; conversely, complete depletion of neutrophils was shown to be detrimental that leads to adverse cardiac remodeling, including uncontrolled fibrosis and reduced macrophage efferocytosis [105]. This signifies that a certain threshold of their counts is necessary to promote beneficial cardiac healing in the ischemic myocardium though excessive amount above that threshold is detrimental [105].

Post-MI, monocytes contribute to both inflammatory and reparative phases and they infiltrate the heart between days 1 and 5. Splenic monocytes supply numbers for the initial infiltration in an IL-1β dependent manner [106–109], while the progenitors from the bone marrow will later replenish the spleen in a c-Kit-dependent process [110]. In addition to IL-1β, Ly6Chi monocytes are also recruited to the heart via MCP-1/CCL2, which acts on C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2 (CCR2) [111–113]. Pro-inflammatory Ly6Chi (classical) monocytes, which appear first post-MI, differentiate into CCR2+ macrophages; but as tissue undergoes healing, Ly6Chi monocytes give rise to Ly6Clo (non-classical) monocytes [114–116]. Ly6Clo monocytes express CX3CR1 instead of CCR2 [117]. These Ly6Clo monocytes differentiate at a lower rate into macrophages that primarily functions as pro-reparative cells and survey endothelial cell health for clearance [114–116]. Conversion from Ly6Chi to Ly6Clo monocytes as a part of the reparative process becomes essential as cardiac tissue-resident CCR2- macrophages that promote heart function via cardiomyocyte proliferation and angiogenesis die after MI [118]. The importance of macrophages in initial inflammation [119] and later tissue resolution [120] in injury conditions such as MI differentiates them into two types, M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory). Response in M2 macrophages is slightly more complex than classically activated M1 macrophages as there are three subsets of M2 macrophages been characterized to date. With both M2a and M2c being associated with tissue repair and extracellular matrix deposition, M2b has an immunomodulatory role [121]. Quantification of M1 TNF-α+ macrophages and M2 ARG1+ macrophages on days 2-, 5-, and 10- post-MI in mice revealed that TNF-α+ macrophages began to decline by day 5 while ARG1+ macrophages were still increasing at day 10 corresponding with the phenotype changes [119]. Significant complexities in macrophage phenotypes came into play with the discovery of seven different cardiac macrophage populations in infarcted hearts from single-cell RNA-seq analyses [112, 113]. An attempt to target a sub-population of macrophages showed beneficial effects against MI as evidenced by improved heart function with deletion of interferon-inducible macrophages (IFNICs) subset of macrophages. This study revealed that pharmacological inhibitors that could inhibit IFNICs showed beneficial effects on heart function if inhibited within 48 hrs. of MI injury [122].

5. Effect of age and sex-related differences in immune responses

5.1. Inflamm-aging

Aging is associated with a systemic inflammatory phenomenon, known as inflamm-aging, which involves elevated production of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors. This phenotype is quite evident in heart and bone marrow of the elderly, both linked with incidence of MI (Fig. 2) [123, 124]. This type of inflammation markedly varies with acute inflammatory response observed post-MI as it is a low-grade immune reaction without injured tissue. Several factors that were identified to contribute to inflamm-aging include damaged macromolecules, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular as well as immune senescence, microbial molecules from the damaged gut, etc [125]. As discussed in section 3.1, ample evidence suggests that early stages of MI injury is accompanied by altered hematopoiesis with a greater bias towards myeloid cell production at the cost of lymphoid cell generation. And aging, per se, has also shown to promote myeloid cell lineages over lymphoid in cardiac tissue by altering cell fate decisions that arise within the bone marrow while markedly increasing inflammation in non-infracted hearts [126, 127]. Aging is also associated with the impaired potential of stem cell progenitors to regenerate myocardium during pathological states [94]. This clearly implicate that inflamm-aging can act as a key participant in exacerbating MI injury. And aging-linked phenomena such as myeloid skewing, trained immunity, and clonal hematopoiesis can act as strong influencers here. The importance of myeloid skewing and CH in inflamm-aging has been overviewed in the following section. In young to adult-aged humans, infection or injury involves initial protection of host tissues by neutrophils via several processes that include phagocytosis, degranulation, and ROS production [97]. And cellular aging has shown to affect the nature of neutrophils in both mice and human models [128]. Aged mice demonstrated decreased neutrophil generation, which resulted to marked decrease in the number of neutrophils recruited to the infection site [129]. In contrast, elderly humans demonstrated majorly functional deficits but not counts in neutrophils [129]. Such differences were also observed in other major myeloid cells such as monocytes and macrophages [130]. In both aged mice and humans, reductions were observed in macrophage surface receptor expression such as major histocompatibility class-II (MHC-II) [131]. Additionally, aged mice demonstrated a 50% reduction in the number of MHC-II molecules upon stimulation with IFN-γ [131] as well as a decline in the ability of phagocytic activity [132] accompanied by decreased generation of macrophage-specific chemokines [133]. In similar line, macrophages from aged rodents also showed an overall decrease in cytokine and chemokine production. While monocytes demonstrated an increased levels of inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, etc in older subjects [129]. Additionally, mutations in the driver genes causing CH also resulted in a proinflammatory cellular phenotype with any such mutations being maintained within all leukocyte progenies [16]. Having said that, the impact of age and age-linked changes on inflammation and resolution phases of the injury post MI in the hematopoietic system with a focus on inflamm-aging is still poorly understood and needs extensive investigations (Fig. 2) [134].

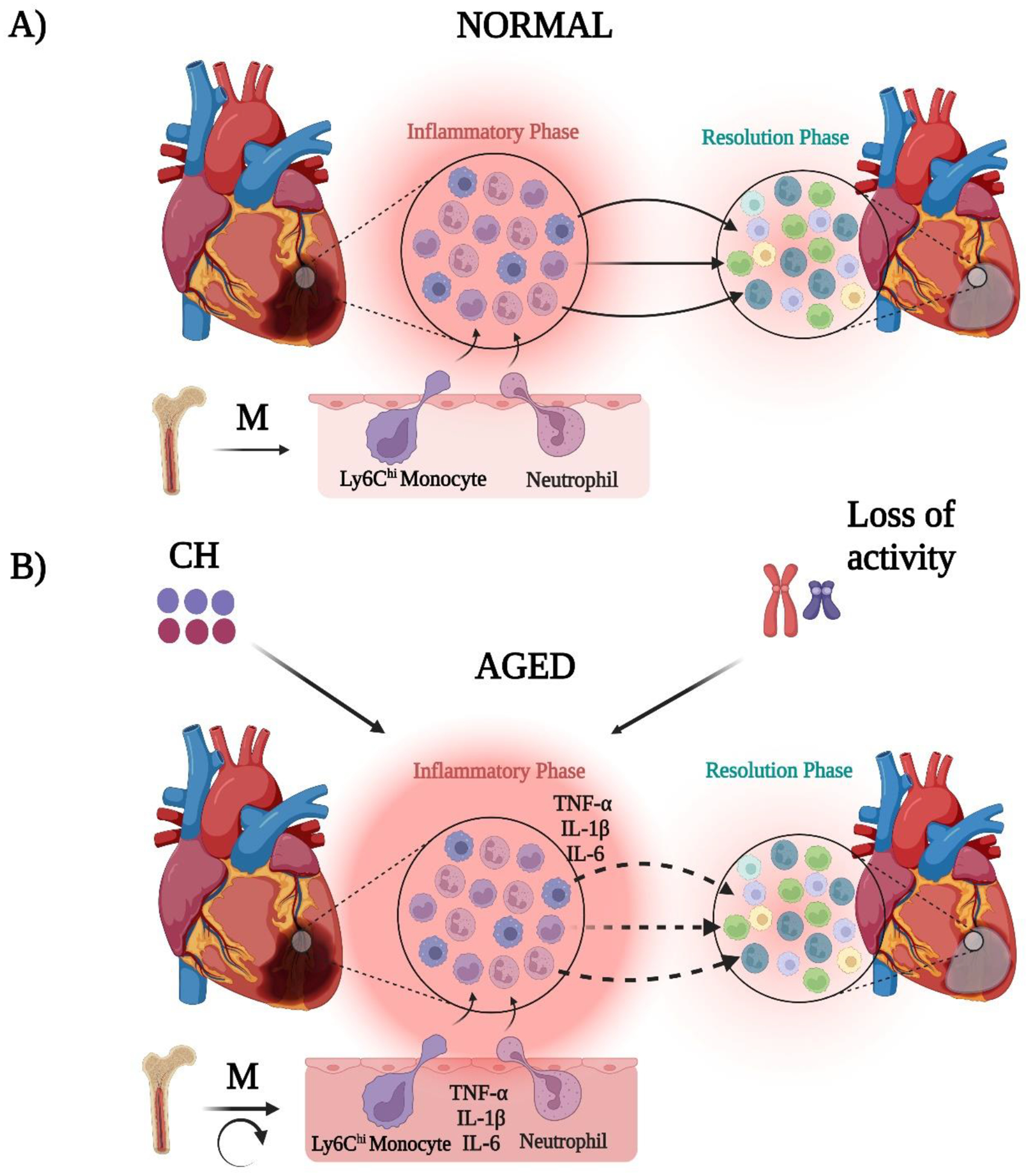

Fig. 2. Phases involved in MI injury in normal and aged hearts and factors affecting the tissue response.

Post-MI, a normal heart demonstrates an initial inflammation phase characterized with different myeloid cells such as N1 neutrophils, Ly6Chi monocytes, and M1 macrophages followed by a resolution phase, where neutrophils are N2, monocytes are Ly6Clo, and macrophages are M2 (further sub-divided as M2a, M2b, and M2c and represented by three different colors). Myeloid cells resulted from myelopoiesis in bone marrow switch from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory phenotype during transition from inflammation to resolution phases of injury. While in aged hearts, myelopoiesis gets enhanced due to feed-back loops thereby enriching inflammatory cytokines because of inflamm-aging and MI exacerbates the underlying tissue and systemic inflammation. This may result in delay of tissue repair due to differences in the rate and extent of myeloid cell phenotypic switch. This delayed may be further impacted with presence of aging associated factors like clonal hematopoiesis (CH) and mosaic loss of Y-chromosome (mLOR). Dotted arrows indicate the necessity for deep phenotyping of the cellular switches both between aged and normal hearts focusing on different myeloid cell sub-sets in future. Circular arrow indicates feed-back loops.

5.2. Sex

Despite clear differences in female and male immunity following myocardial infarction (MI), the exact mechanism that drives the stark contrast between sexes with a focus on myeloid cells remains insufficiently characterized [61, 135, 136]. In experimental model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R), female rats exhibited attenuated expression and coronary effluent levels of IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-6, and TNF-α along with reduced cardiac p38 activation. These effects culminated in better cardiac outcomes in female rats compared to their male counterparts [137]. Moreover, MI studies confirmed that infarct tissue in female mice exhibited lower expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-6 receptor at day 1 and 4 post-MI along with faster IL-6 resolving from plasma compared to males and no sex differences in TNF-α production were observed [78, 138]. Higher mortality rates observed in male mice in the same study were attributed to the marked deposition of infiltrated neutrophils at the ischemic border zones [77, 138, 139]. Infiltrating neutrophils secrete matrix metalloprotease 9 (MMP-9) and activation of this protease resulted in increased infarcted size and more cardiac rupture in male mice [77, 138, 139]. Lower neutrophil counts in female mice were accompanied by higher macrophage abundance at day 4, which revealed that they (females) demonstrate better wound healing abilities due to the prevention of excessive post-MI inflammation as well accelerated inflammation resolution [77]. Lower incidence of cardiac rupture, attenuated LV dilation, and an accelerated IL-6 plasma resolution were also observed in a recent study in which young female mice showed lower rates of mortality than males [78]. Despite no differences in infarct sizes at day 1 post-MI, females exhibited 2-fold lower mRNA expression of IL-13, CXCR3, CXCL4, and TIMP-1 along with IL-1 receptor 1 and IL-6 receptor α subunit in the infarct area. Though both male and female mice showed similar neutrophil infiltration kinetics, male myocardium demonstrated a higher neutrophil abundance at day 3 post-MI [78]. Neutrophils from the female mice were found to be more efficient at clearing necrotic tissues after MI, with lower N1 polarization (pro-inflammatory) and greater N2 polarization (anti-inflammatory) than males [78]. Furthermore, sex-based differences exist in cell clearance as evident from male neutrophils (isolated from humans) displaying CD36-dependent MMP-9 degranulation to clear necrotic tissue, while those from females cleared cell debris via phagocytosis [78]. Overall, young female mice in this study were found to be more efficient than young males or old mice of either sex at resolving the inflammatory response through differences in neutrophil functions [78]. Variations in menstrual cycle-based changes in myeloid cells is specific to females which gets significantly affected with aging. Though extensive studies haven’t been performed is this arena to date, some studies have determined the effects of menstrual cycles on markers of inflammation. During the periovulatory state, slight alterations in the phenotype of the circulating neutrophils were observed with diminished MMP-9 and TNF-α expression [140]. Additionally, sex differences in post-MI wound healing and remodeling were studied in both male and female mice of young (3–9 months; pre-menopausal) and old (11–36 months; post-menopausal) ages [78]. It was inferred that aging in females abolished the initial protection against excessive IL-6 production and signaling due to reduced liver X receptors/retinoid X receptor LXR/RXR activation.

6. Future perspectives

6.1. Studies to determine the age-sex interactions focusing on spatial and temporal variations in myeloid cell populations.

It is imperative that myeloid cells are crucial during the inflammatory phase of MI injury, while lymphocytes are critical for injury resolution. Evidence is also emerging that all three myeloid cell types viz., neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages participate in the inflammatory as well as resolution phases and the observed biphasic responses are based on the relative amounts of their cellular accumulation as well as the nature (sub-sets) of the specific cell types. Therefore, it is obvious that regulation of the cellular response at the initial phases of injury may be highly effective as this can limit infarct size [141]. Moreover, more precise control over different populations of myeloid cells is required to achieve a safe and effective treatment [94]. Earlier studies have attempted on reducing cardiac neutrophil recruitment or their function to limit tissue injury in myocardial I/R experimental models. Though some were successful, anti-neutrophil therapies have been largely unsuccessful to date [104]. The beneficial effects of MPO inhibitor (PF-1355) on acute inflammation and left ventricular inflammation despite its limited effect on infarct size, when administered orally for 7 days post-I/R is one classical example that exemplify the role of other aging and sex-linked factors that needs to be considered while designing appropriate therapeutic strategies. These mixed effects may be attributed to complex interactions between neutrophils and other myeloid cell populations and precise control of such interactions on infarct sizes. It is very important to study changes in each myeloid cell sub-set populations during inflammation and resolution phases of MI injury and this should include both male and female subjects coming from different age groups (young, adult, and aged). Most studies involving MI in female mice were performed in young (pre-menopausal) adults but not in old (menopausal) mice. These studies don’t account for the changes in elderly women affected by MI, and this indeed neglects the importance of the personalized requirement of the therapies according to their age-induced adaptations in hormones, cell renewal, proliferation, and regeneration capacities. And the outcomes from the published literature contribute to the tip of the iceberg concerning the complexity of the age and sex interactions on changes in myelopoiesis in the context of MI. It is quite encouraging that cardiovascular research fraternities are accepting the necessity of including age when studying sex differences in cardiometabolic diseases (CMD). A recent study in this line characterized how sex differences in cardiometabolic risk factors vary with age by examining 45 phenotypes and 6 lifestyle factors in 146,021 participants of the Dutch population aged between 20 to 80 years [142]. CMD risk factors showed all varieties of age-related sex differences, ranging from no sex differences to complex patterns of age and sex differences [142].

6.2. Factors to consider while designing interaction studies.

The process of aging is heterogeneous in nature where the rate of decline in functional activity at different levels viz., molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ levels varies enormously among individuals. These variations accompanied by differences in the activity of sex chromosomes (X-chromosome in females vs Y-chromosome in males) and sex hormones (estrogen in females vs testosterone in males) forms the basis behind the complexity in the initiation and progression of CVDs (Fig. 3). Understanding sex-specific myeloid cell activities with a focus on cell-specific sub-sets at different age groups could decipher key outcomes. Molecularly this could involve studying expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and inflammatory genes at given experimental conditions. Sex-specific effects of NLRP3 inflammasome in promoting atherosclerosis was evaluated by Chen and colleagues [143] and these findings may play an important role for studies to design personalized therapeutic targets based on age-sex interactions. One key additional factor to consider while designing the age-sex interaction studies involves determining the presence and absence of CH in different subjects (Fig. 3). Experiments involving rodents (especially mice) could potentially use models that show either global or tissue-specific deletion of the driver genes. Bone marrow transplant experiments reconstituting marrow cells showing absence or presence of driver genes among different age groups (young or adult or old) of both sexes (with complete or partial sex-chromosomal activity) will for sure play an important role in determining the reasons behind the differences in the myeloid cell sub-set populations as well as their activities. Outcomes from such studies may finally help in determining the reasons behind the variations in the extent of the tissue injury or mixed effects of the pharmacological modulators as well as hormonal therapies. To summarize, age-sex interaction studies in future will pave a way for designing personalized therapeutic approaches according to the patient needs.

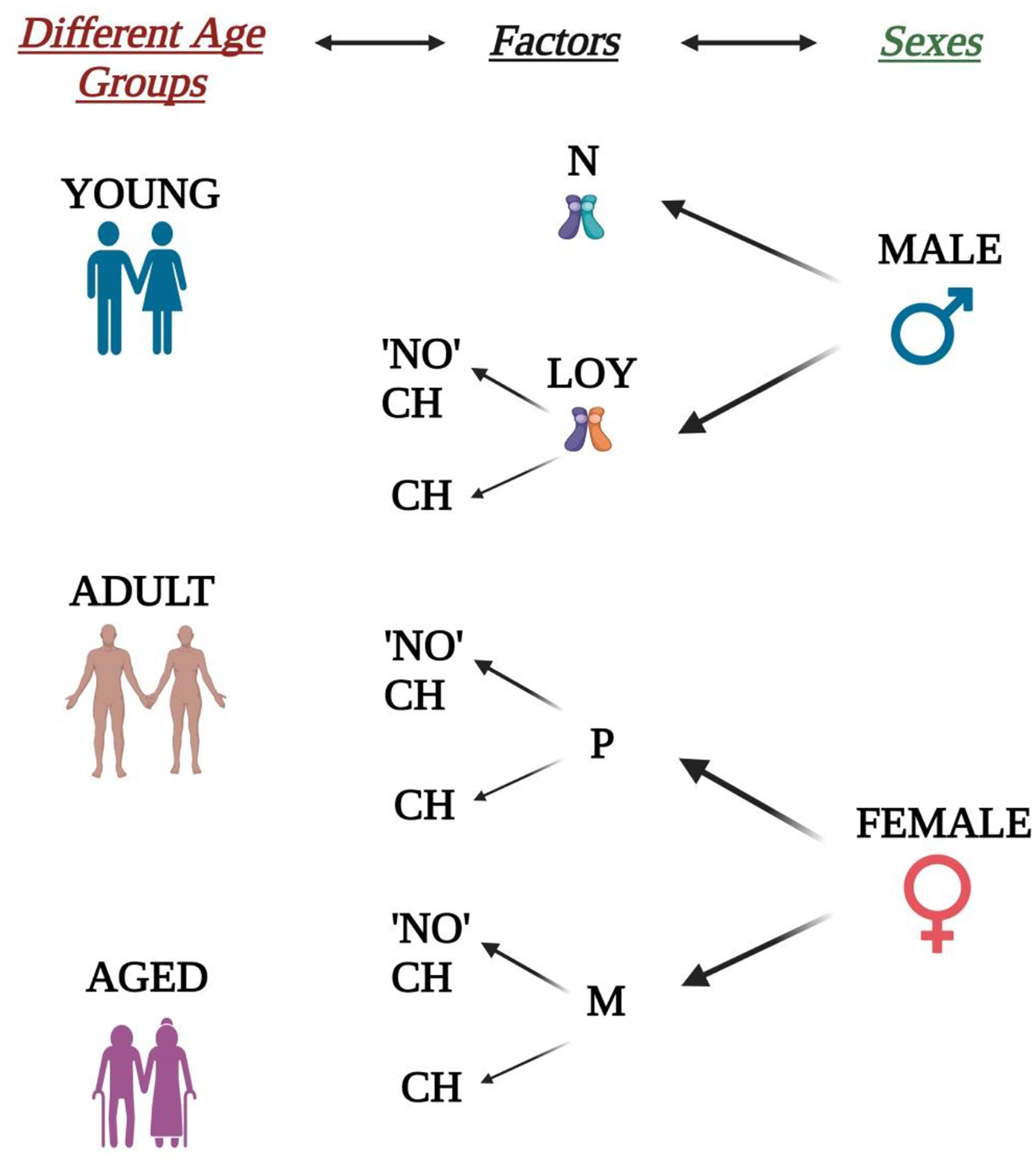

Fig. 3. Considerations for designing age and sex interaction studies.

Three different disease relevant ages (young, adult, and aged) and both sexes form the pillars while designing interaction studies. Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) in both sexes, alterations in Y-chromosomal activities in males as well as menopause in females can act as key factors while stratifying different experimental groups. Males with changes (decreased or complete loss) in Y-chromosomal activity (LOY) can be further classified based on whether they show CH. While in case of females, both pre-menopausal (P) and menopausal (M) stages shall be further stratified based on the presence or absence of CH. The complexity of the stratification in males may further depend on the extent or percent (%) Y-Chromosomal loss (LOR). In case of females, menopause associated other complexities may also take participation in designing groups. LOY and N refer to loss of Y-Chromosomal activity and normal Y-chromosomal activities, respectively. Y chromosomes in both N and LOR conditions were represented by different colors in the figure.

7. Conclusion

The current state of understanding on how age and sex interactions occur and their contribution to the changes in myelopoiesis in MI disease states is inconclusive and this necessitates extensive investigations in future. Involvement of different myeloid cells in response to MI injury and the existence of sub-sets for each cell type makes the disease pathogenesis a complex phenomenon. These complexities combined with the presence or absence of one or more risk factors such as sex, age, CH, etc. makes it difficult to consider a homogenous treatment plan across subjects. This brings into place the need for determining the nature and specific functions of cell-specific sub-sets as well as role of condition-specific molecular pathways (e.g., NLRP3 inflammasome) as a part of designing targeted therapeutics based on patient specific-needs. This strategy may be potentially beneficial as it will be based on the mediators that are of crucial interest rather than broader strategies targeting inflammatory phases of injury in general to mitigate MI.

Highlights.

Age and sex represent the most important risk factors for heart disease. Aging shows its harmful effects through a process known as inflamm-aging. Along with age, sex differences have also been shown to demonstrate variations in response to pathological insults. Increasing evidence suggests that acute inflammation driven by myelopoiesis is enhanced after acute MI, with a bias toward the formation of inflammatory monocytes. There is paucity of information on tissue and site-specific functions of different myeloid sub-sets post-MI injury.

There are multiple factors determinants in MI disease pathology. Clonal hematopoiesis (CH), mosaic loss of Y chromosome and menopause are some of the key determinants.

The current state of understanding on age and sex interactions in MI induced myelopoiesis is inconclusive. Designing and executing experiments focused on these interactions will be helpful in developing personalized therapeutic strategies post-MI in future.

Funding

PRN is supported by grants from the NIH (HL156856, HL137799) and AHA (TPA97002)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

AI-assisted technology is not used in the preparation of this work (except checking grammar and spelling).

References

- [1].Golforoush P, Yellon DM, Davidson SM. Mouse models of atherosclerosis and their suitability for the study of myocardial infarction. Basic research in cardiology. 2020;115:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ojha N, Dhamoon AS. Myocardial infarction. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Konstantinidis K, Whelan RS, Kitsis RN. Mechanisms of cell death in heart disease. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32:1552–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Buttar HS, Li T, Ravi N. Prevention of cardiovascular diseases: Role of exercise, dietary interventions, obesity and smoking cessation. Experimental & clinical cardiology. 2005;10:229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dhingra R, Vasan RS. Age as a risk factor. Medical Clinics. 2012;96:87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Halter JB, Musi N, McFarland Horne F, Crandall JP, Goldberg A, Harkless L, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in older adults: current status and future directions. Diabetes. 2014;63:2578–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Corriere M, Rooparinesingh N, Kalyani RR. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes complications in the elderly: an emerging public health burden. Current diabetes reports. 2013;13:805–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Martos R, Baugh J, Ledwidge M, O’Loughlin C, Conlon C, Patle A, et al. Diastolic heart failure: evidence of increased myocardial collagen turnover linked to diastolic dysfunction. Circulation. 2007;115:888–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Afilalo J, Karunananthan S, Eisenberg MJ, Alexander KP, Bergman H. Role of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. The American journal of cardiology. 2009;103:1616–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sergi G, Veronese N, Fontana L, De Rui M, Bolzetta F, Zambon S, et al. Pre-frailty and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly men and women: the Pro. VA study. Journal of The American college of cardiology. 2015;65:976–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, d’Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PW, et al. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006;113:791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Khot UN, Khot MB, Bajzer CT, Sapp SK, Ohman EM, Brener SJ, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. Jama. 2003;290:898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fernández-Friera L, Peñalvo JL, Fernández-Ortiz A, Ibañez B, López-Melgar B, Laclaustra M, et al. Prevalence, vascular distribution, and multiterritorial extent of subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle-aged cohort: the PESA (Progression of Early Subclinical Atherosclerosis) study. Circulation. 2015;131:2104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Laclaustra M, Casasnovas JA, Fernández-Ortiz A, Fuster V, León-Latre M, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, et al. Femoral and carotid subclinical atherosclerosis association with risk factors and coronary calcium: the AWHS study. Journal of the American college of cardiology. 2016;67:1263–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, Polackal MN, Ostriker AC, Chakraborty R, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science. 2017;355:842–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cochran J, Walsh K. Clonal Hematopoiesis: From Macrovascular to Microvascular Disease. Am Heart Assoc; 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Evans MA, Walsh K. Clonal hematopoiesis, somatic mosaicism, and age-associated disease. Physiological Reviews. 2023;103:649–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chavkin NW, Min K-D, Walsh K. Importance of clonal hematopoiesis in heart failure. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022;32:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cosgrove J, Hustin LS, de Boer RJ, Perié L. Hematopoiesis in numbers. Trends in Immunology. 2021;42:1100–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Young AL, Challen GA, Birmann BM, Druley TE. Clonal haematopoiesis harbouring AMLassociated mutations is ubiquitous in healthy adults. Nature communications. 2016;7:12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bonnefond A, Skrobek B, Lobbens S, Eury E, Thuillier D, Cauchi S, et al. Association between large detectable clonal mosaicism and type 2 diabetes with vascular complications. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1040–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371:2488–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:111–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Abplanalp WT, Cremer S, John D, Hoffmann J, Schuhmacher B, Merten M, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis–driver DNMT3A mutations alter immune cells in heart failure. Circulation Research. 2021;128:216–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Netherlands Heart Journal. 2010;18:598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Merz AA, Cheng S. Sex differences in cardiovascular ageing. Heart. 2016;102:825–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Bairey Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE. Cardiovascular disease in women: clinical perspectives. Circulation research. 2016;118:1273–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Naftolin F, Friedenthal J, Nachtigall R, Nachtigall L. Cardiovascular health and the menopausal woman: the role of estrogen and when to begin and end hormone treatment. F1000Research. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dalal PK, Agarwal M. Postmenopausal syndrome. Indian journal of psychiatry. 2015;57:S222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, Dwairy A, McCaffrey J, Yunus R, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and myocardial infarction in the transgender population. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019;12:e005597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Austad SN, Fischer KE. Sex differences in lifespan. Cell metabolism. 2016;23:1022–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fischer KE, Riddle NC. Sex differences in aging: genomic instability. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2018;73:166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Maklakov AA, Lummaa V. Evolution of sex differences in lifespan and aging: causes and constraints. BioEssays. 2013;35:717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sampathkumar NK, Bravo JI, Chen Y, Danthi PS, Donahue EK, Lai RW, et al. Widespread sex dimorphism in aging and age-related diseases. Human genetics. 2020;139:333–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hägg S, Jylhävä J. Sex differences in biological aging with a focus on human studies. Elife. 2021;10:e63425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dearden L, Bouret SG, Ozanne SE. Sex and gender differences in developmental programming of metabolism. Molecular metabolism. 2018;15:8–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kadlecova M, Freude K, Haukedal H. Complexity of Sex Differences and Their Impact on Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines. 2023;11:1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Singh P Andropause: current concepts. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;17:S621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Suarez LM, Diaz-Del Cerro E, Felix J, Gonzalez-Sanchez M, Ceprian N, Guerra-Perez N, et al. Sex differences in neuroimmunoendocrine communication. Involvement on longevity. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2023;211:111798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Oertelt-Prigione S The influence of sex and gender on the immune response. Autoimmunity reviews. 2012;11:A479–A85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wilkinson NM, Chen H-C, Lechner MG, Su MA. Sex differences in immunity. Annual review of immunology. 2022;40:75–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Scotland RS, Stables MJ, Madalli S, Watson P, Gilroy DW. Sex differences in resident immune cell phenotype underlie more efficient acute inflammatory responses in female mice. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2011;118:5918–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bouman A, Schipper M, Heineman MJ, Faas MM. Gender difference in the non specific and specific immune response in humans. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2004;52:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fuente MDL, Baeza I, Guayerbas N, Puerto M, Castillo C, Salazar V, et al. Changes with ageing in several leukocyte functions of male and female rats. Biogerontology. 2004;5:389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Baeza I, De Castro NM, Arranz L, Fdez-Tresguerres J, De la Fuente M. Ovariectomy causes immunosenescence and oxi-inflamm-ageing in peritoneal leukocytes of aged female mice similar to that in aged males. Biogerontology. 2011;12:227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Härkönen PL, Väänänen HK. Monocyte–macrophage system as a target for estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1089:218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jaillon S, Berthenet K, Garlanda C. Sexual dimorphism in innate immunity. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2019;56:308–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bianchi I, Lleo A, Gershwin ME, Invernizzi P. The X chromosome and immune associated genes. Journal of autoimmunity. 2012;38:J187–J92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Libert C, Dejager L, Pinheiro I. The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2010;10:594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jobling MA, Tyler-Smith C. Human Y-chromosome variation in the genome-sequencing era. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2017;18:485–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sano S, Horitani K, Ogawa H, Halvardson J, Chavkin NW, Wang Y, et al. Hematopoietic loss of Y chromosome leads to cardiac fibrosis and heart failure mortality. Science. 2022;377:292–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Forsberg LA, Rasi C, Malmqvist N, Davies H, Pasupulati S, Pakalapati G, et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in peripheral blood is associated with shorter survival and higher risk of cancer. Nature genetics. 2014;46:624–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pierre RV, Hoagland HC. Age associated aneuploidy: Loss of Y chromosome from human bone marrow cells with aging. Cancer. 1972;30:889–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Thompson DJ, Genovese G, Halvardson J, Ulirsch JC, Wright DJ, Terao C, et al. Genetic predisposition to mosaic Y chromosome loss in blood. Nature. 2019;575:652–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Forsberg LA, Halvardson J, Rychlicka-Buniowska E, Danielsson M, Moghadam BT, Mattisson J, et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in leukocytes matters. Nature Genetics. 2019;51:4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Machiela MJ, Zhou W, Karlins E, Sampson JN, Freedman ND, Yang Q, et al. Female chromosome X mosaicism is age-related and preferentially affects the inactivated X chromosome. Nature communications. 2016;7:11843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Loh P-R, Genovese G, Handsaker RE, Finucane HK, Reshef YA, Palamara PF, et al. Insights into clonal haematopoiesis from 8,342 mosaic chromosomal alterations. Nature. 2018;559:350–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sammaritano LR. Menopause in patients with autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity reviews. 2012;11:A430–A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, Lindsley RC, Sekeres MA, Hasserjian RP, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2015;126:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yu B, Roberts MB, Raffield LM, Zekavat SM, Nguyen NQH, Biggs ML, et al. Association of clonal hematopoiesis with incident heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;78:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Strait JB, Lakatta EG. Aging-associated cardiovascular changes and their relationship to heart failure. Heart failure clinics. 2012;8:143–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Fleg JL, Strait J. Age-associated changes in cardiovascular structure and function: a fertile milieu for future disease. Heart failure reviews. 2012;17:545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Aging Weisfeldt M., changes in the cardiovascular system, and responses to stress. American journal of hypertension. 1998;11:41S–5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Carro A, Kaski JC. Myocardial infarction in the elderly. Aging and disease. 2011;2:116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Boyle AJ, Hwang J, Ye J, Shih H, Jun K, Zhang Y, et al. The effects of aging on apoptosis following myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular therapeutics. 2013;31:e102–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].McMechan SR, Adgey AJ. Age related outcome in acute myocardial infarction: elderly people benefit from thrombolysis and should be included in trials. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 1998. p. 1334–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, MacLauchlan S, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, et al. Tet2-mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates heart failure through a mechanism involving the IL-1β/NLRP3 inflammasome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71:875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Corti R, de Wit C, Dorobantu M, Hall A, et al. Ischaemic heart disease in women: are there sex differences in pathophysiology and risk factors? Position paper from the working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovascular research. 2011;90:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bernasochi GB, Boon WC, Delbridge LM, Bell JR. The myocardium and sex steroid hormone influences. Current Opinion in Physiology. 2018;6:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Menazza S, Murphy E. The expanding complexity of estrogen receptor signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circulation research. 2016;118:994–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Peterson ED, Rogers WJ, Kiefe CI, Canto J. Sex differences in mortality after acute myocardial infarction: changes from 1994 to 2006. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:1767–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Crabbe DL, Dipla K, Ambati S, Zafeiridis A, Gaughan JP, Houser SR, et al. Gender differences in post-infarction hypertrophy in end-stage failing hearts. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41:300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Guerra S, Leri A, Wang X, Finato N, Di Loreto C, Beltrami CA, et al. Myocyte death in the failing human heart is gender dependent. Circulation research. 1999;85:856–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Patten RD. Models of gender differences in cardiovascular disease. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2007;4:227–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wu JC, Nasseri BA, Bloch KD, Picard MH, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Influence of sex on ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2003;16:1158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Gao X-M, Xu Q, Kiriazis H, Dart AM, Du X-J. Mouse model of post-infarct ventricular rupture: time course, strain-and gender-dependency, tensile strength, and histopathology. Cardiovascular research. 2005;65:469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Cavasin MA, Tao Z, Menon S, Yang X-P. Gender differences in cardiac function during early remodeling after acute myocardial infarction in mice. Life sciences. 2004;75:2181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].DeLeon-Pennell KY, Mouton AJ, Ero OK, Ma Y, Padmanabhan Iyer R, Flynn ER, et al. LXR/RXR signaling and neutrophil phenotype following myocardial infarction classify sex differences in remodeling. Basic research in cardiology. 2018;113:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zhai P, Eurell TE, Cotthaus R, Jeffery EH, Bahr JM, Gross DR. Effect of estrogen on global myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in female rats. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2000;279:H2766–H75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Menazza S, Sun J, Appachi S, Chambliss KL, Kim SH, Aponte A, et al. Non-nuclear estrogen receptor alpha activation in endothelium reduces cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2017;107:41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Knowlton A, Lee A. Estrogen and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2012;135:54–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Iorga A, Cunningham CM, Moazeni S, Ruffenach G, Umar S, Eghbali M. The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biology of sex differences. 2017;8:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].El Khoudary S, Aggarwal B, Beckie T, Hodis H, Johnson A, Langer R, et al. American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Pongkan W, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Chronic testosterone replacement exerts cardioprotection against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury by attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction in testosterone-deprived rats. PloS one. 2015;10:e0122503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Pongkan W, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Roles of testosterone replacement in cardiac ischemia–reperfusion injury. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 2016;21:27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Getahun D, Nash R, Flanders WD, Baird TC, Becerra-Culqui TA, Cromwell L, et al. Crosssex hormones and acute cardiovascular events in transgender persons: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2018;169:205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Harrington J, Fillmore N, Gao S, Yang Y, Zhang X, Liu P, et al. A systems biology approach to investigating sex differences in cardiac hypertrophy. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6:e005838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kararigas G, Dworatzek E, Petrov G, Summer H, Schulze TM, Baczko I, et al. Sex-dependent regulation of fibrosis and inflammation in human left ventricular remodelling under pressure overload. European journal of heart failure. 2014;16:1160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Michel FS, Magubane M, Mokotedi L, Norton GR, Woodiwiss AJ. Sex-specific effects of adrenergic-induced left ventricular remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2017;23:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].JOHANSSON S, BERGSTRAND R, ULVENSTAM G, VEDIN A, WILHELMSSON C, WEDEL H, et al. Sex differences in preinfarction characteristics and longterm survival among patients with myocardial infarction. American journal of epidemiology. 1984;119:610–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Vaccarino V, Horwitz RI, Meehan TP, Petrillo MK, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction: evidence for a sex-age interaction. Archives of internal medicine. 1998;158:2054–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Jneid H, Al Hajji M, Boubas W, Lerman A. Age-stratified sex-related differences in the incidence, management, and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Elsevier; 2021. p. 332–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Stehli J, Duffy SJ, Burgess S, Kuhn L, Gulati M, Chow C, et al. Sex disparities in myocardial infarction: biology or bias? Heart, Lung and Circulation. 2021;30:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Tobin SW, Alibhai FJ, Weisel RD, Li R-K. Considering cause and effect of immune cell aging on cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Cells. 2020;9:1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Pinto AR, Ilinykh A, Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, D’antoni ML, Debuque R, et al. Revisiting cardiac cellular composition. Circulation research. 2016;118:400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Ghigo A, Franco I, Morello F, Hirsch E. Myocyte signalling in leucocyte recruitment to the heart. Cardiovascular research. 2014;102:270–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Rosales C Neutrophil: a cell with many roles in inflammation or several cell types? Frontiers in physiology. 2018;9:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Puhl S-L, Steffens S Neutrophils in post-myocardial infarction inflammation: damage vs. resolution? Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2019;6:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Manz MG, Boettcher S. Emergency granulopoiesis. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2014;14:302–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Sreejit G, Abdel-Latif A, Athmanathan B, Annabathula R, Dhyani A, Noothi SK, et al. Neutrophil-derived S100A8/A9 amplify granulopoiesis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2020;141:1080–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Sreejit G, Nooti SK, Jaggers RM, Athmanathan B, Ho Park K, Al-Sharea A, et al. Retention of the NLRP3 Inflammasome-Primed Neutrophils in the Bone Marrow Is Essential for Myocardial Infarction-Induced Granulopoiesis. Circulation. 2022;145:31–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Iyer RP, Cannon PL, Flynn ER, Jung M, et al. Temporal neutrophil polarization following myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular research. 2016;110:51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Soehnlein O, Zernecke A, Eriksson EE, Rothfuchs AG, Pham CT, Herwald H, et al. Neutrophil secretion products pave the way for inflammatory monocytes. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2008;112:1461–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circulation research. 2012;110:159–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Horckmans M, Ring L, Duchene J, Santovito D, Schloss MJ, Drechsler M, et al. Neutrophils orchestrate post-myocardial infarction healing by polarizing macrophages towards a reparative phenotype. European heart journal. 2017;38:187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Leuschner F, Rauch PJ, Ueno T, Gorbatov R, Marinelli B, Lee WW, et al. Rapid monocyte kinetics in acute myocardial infarction are sustained by extramedullary monocytopoiesis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2012;209:123–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Saxena A, Chen W, Su Y, Rai V, Uche OU, Li N, et al. IL-1 induces proinflammatory leukocyte infiltration and regulates fibroblast phenotype in the infarcted myocardium. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;191:4838–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Sager HB, Heidt T, Hulsmans M, Dutta P, Courties G, Sebas M, et al. Targeting interleukin-1β reduces leukocyte production after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015;132:1880–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Dutta P, Courties G, Wei Y, Leuschner F, Gorbatov R, Robbins CS, et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature. 2012;487:325–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, Koerting A, Ren G, Abou-Khamis T, et al. CCL2/Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circulation research. 2005;96:881–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. Journal of interferon & cytokine research. 2009;29:313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo J-L, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:3037–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Carlin LM, Stamatiades EG, Auffray C, Hanna RN, Glover L, Vizcay-Barrena G, et al. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6Clow monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. 2013;153:362–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Hou X, Chen G, Bracamonte-Baran W, Choi HS, Diny NL, Sung J, et al. The cardiac microenvironment instructs divergent monocyte fates and functions in myocarditis. Cell reports. 2019;28:172–89. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Ma Y, Mouton AJ, Lindsey ML. Cardiac macrophage biology in the steady-state heart, the aging heart, and following myocardial infarction. Translational Research. 2018;191:15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Heidt T, Courties G, Dutta P, Sager HB, Sebas M, Iwamoto Y, et al. Differential contribution of monocytes to heart macrophages in steady-state and after myocardial infarction. Circulation research. 2014;115:284–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Troidl C, Möllmann H, Nef H, Masseli F, Voss S, Szardien S, et al. Classically and alternatively activated macrophages contribute to tissue remodelling after myocardial infarction. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2009;13:3485–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Yan X, Anzai A, Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, Ito K, Endo J, et al. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2013;62:24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Rőszer T Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators of inflammation. 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].King KR, Aguirre AD, Ye Y-X, Sun Y, Roh JD, Ng RP Jr, et al. IRF3 and type I interferons fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction. Nature medicine. 2017;23:1481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Kovtonyuk LV, Fritsch K, Feng X, Manz MG, Takizawa H. Inflamm-aging of hematopoiesis, hematopoietic stem cells, and the bone marrow microenvironment. Frontiers in immunology. 2016;7:502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflammaging: an evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Annals of the new York Academy of Sciences. 2000;908:244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2014;69:S4–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Sudo K, Ema H, Morita Y, Nakauchi H. Age-associated characteristics of murine hematopoietic stem cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Pang WW, Price EA, Sahoo D, Beerman I, Maloney WJ, Rossi DJ, et al. Human bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells are increased in frequency and myeloid-biased with age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:20012–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Biasi D, Carletto A, Dell’Agnola C, Caramaschi P, Montesanti F, Zavateri G, et al. Neutrophil migration, oxidative metabolism, and adhesion in elderly and young subjects. Inflammation. 1996;20:673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Kovacs EJ, Palmer JL, Fortin CF, Fülöp T Jr, Goldstein DR, Linton P-J. Aging and innate immunity in the mouse: impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Trends in immunology. 2009;30:319–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nature reviews immunology. 2011;11:762–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Herrero C, Marqués L, Lloberas J, Celada A. IFN-γ–dependent transcription of MHC class II IA is impaired in macrophages from aged mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;107:485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Rabatić S, Sabioncello A, Dekaris D, Kardum I. Age-related changes in functions of peripheral blood phagocytes. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 1988;45:223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Swift ME, Burns AL, Gray KL, DiPietro LA. Age-related alterations in the inflammatory response to dermal injury. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2001;117:1027–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Schultze JL, Mass E, Schlitzer A. Emerging principles in myelopoiesis at homeostasis and during infection and inflammation. Immunity. 2019;50:288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]