Abstract

Background:

Impairment in social cognition, particularly eye gaze processing, is a shared feature common to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia. However, it is unclear if a convergent neural mechanism also underlies gaze dysfunction in these conditions. The present study examined whether this shared eye gaze phenotype is reflected in a profile of convergent neurobiological dysfunction in ASD and schizophrenia.

Methods:

Activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analyses were conducted on peak voxel coordinates across the whole brain to identify spatial convergence. Functional coactivation with regions emerging as significant was assessed using meta-analytic connectivity modeling. Functional decoding was also conducted.

Results:

Fifty-six experiments (n=30 with schizophrenia and n=26 with ASD) from 36 articles met inclusion criteria, which comprised 354 participants with ASD, 275 with schizophrenia and 613 healthy controls (1,242 participants in total). In ASD, aberrant activation was found in the left amygdala relative to unaffected controls during gaze processing. Across ASD and schizophrenia, aberrant activation was found in the right inferior frontal gyrus and right fusiform gyrus during gaze processing. Functional decoding mapped the left amygdala to domains related to emotion processing and cognition, the right inferior frontal gyrus to cognition and perception, and the right fusiform gyrus to visual perception, spatial cognition, and emotion perception. These regions also showed meta-analytic connectivity to frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry.

Conclusion:

Alterations in frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry emerged as neural markers of gaze impairments in ASD and schizophrenia. These findings have implications for advancing transdiagnostic biomarkers to inform targeted treatments for ASD and schizophrenia.

Keywords: Amygdala, Autism spectrum disorder, Schizophrenia, Eye gaze, Cognitive control, Lateral prefrontal cortex

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia share overlapping clinical symptoms of impairments in social cognitive functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Fernandes et al., 2018; Martínez et al., 2019; Morrison et al., 2017; Pinkham et al., 2020), despite broad differences in symptom presentations, ages of onset, and developmental courses. Emerging evidence also suggests that social cognitive impairment, such as face and eye gaze perception, is a potential marker for ASD and schizophrenia (Martínez et al., 2019; Oliver et al., 2021). Given the interest in cross-disorder or transdiagnostic research on social cognition that is consistent with the NIMH Research Domain Criteria framework—which prioritizes circuits and systems for improving functional outcomes—examination of social cognitive functioning across ASD and schizophrenia can advance understanding of convergent neural disruptions in social cognitive circuitry that may lead to related but distinct diagnostic presentations (Gur and Gur, 2016; Sasson et al., 2011; Tso et al., 2020). Thus, identification of neural disruptions across ASD and schizophrenia has potential to contribute to development of brain-based biomarkers to inform screening/early detection, diagnosis, and/or targeted treatments (Sasson et al., 2011; Sasson et al., 2021). The current study investigates neural circuit disruptions in ASD and schizophrenia across domains of eye gaze processing.

1.1. Eye Gaze Processing Impairments Common to ASD and Schizophrenia

ASD is a developmental disorder characterized by impairment in social communication and interaction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) including emotion recognition (Rutherford et al., 2002), reduced eye contact and eye gaze abnormalities (Frazier et al., 2017). Impairments in higher-order social cognitive skills are also common in ASD, such as the ability to represent the mental states of others or mentalizing (i.e., ‘theory of mind’) (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985; Senju et al., 2009). Similarly, impairments in social communication, interaction, and cognition are prominent features of schizophrenia (Brekke et al., 2005; Eack et al., 2010) including abnormalities in emotion perception (Chung et al., 2014; Kohler et al., 2010; Pinkham et al., 2007; Sasson et al., 2011), mentalizing (Bora et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2014; Sprong et al., 2007), making complex social judgments (Baas et al., 2008; Haut and MacDonald III, 2010), and emotional expression such as reduced eye gaze (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Tso et al., 2012). Studies directly comparing ASD and schizophrenia suggest convergent abnormalities in social cognitive processes (Bliksted et al., 2016; Chung et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2018; Pinkham et al., 2008; Sasson et al., 2011) including emotion recognition and solving emotion-based problems (2013), and mentalizing (2016). Studies that have directly compared individuals with ASD and schizophrenia report similar levels of impairments in social cognitive tasks relative to unaffected controls (Martínez et al., 2019; Pinkham et al., 2020). In support of this, a recent meta-analysis comparing ASD and schizophrenia reported similar deficits across subdomains of social cognition including emotion processing, theory of mind, and eye gaze processing (Oliver et al., 2021). There is also evidence to suggest similar impairment levels in those with ASD and schizophrenia vs typically developing individuals on tasks spanning domains of eye gaze processing (Dalton et al., 2005; Li et al., 2020; Loughland et al., 2002; Oliver et al., 2021). For example, studies directly comparing ASD and schizophrenia during eye gaze processing reported less time fixating on face stimuli than controls as well as reduced accuracy and visual attention during congruent emotional contexts (Sasson et al., 2007; Sasson et al., 2016). However, it is unclear if a convergent neural mechanism also underlies this gaze dysfunction within and across disorders. Thus, the current study investigated whether shared or differentiated neural correlates underpin eye gaze impairments in ASD and schizophrenia using an activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis.

Impairments are observed in ASD and schizophrenia across different gaze processing paradigms (Itier and Batty, 2009; Pinkham et al., 2011; Tso et al., 2020). Imaging studies have consistently shown functional abnormalities during gaze and eye movement paradigms within frontotemporal and frontoparietal circuitry—implicated in social cognition and cognitive control—in ASD (Dalton et al., 2005; Davies et al., 2011) and schizophrenia (Kohler et al., 2010; Pinkham et al., 2011). For instance, hypoactivation in the superior temporal sulcus (Pelphrey et al., 2005; Vaidya et al., 2011), temporoparietal junction (von dem Hagen et al., 2014), and lateral prefrontal cortex (Davies et al., 2011; Zurcher et al., 2013) has been shown in ASD during gaze perception. Amygdala (Kliemann et al., 2012; Tottenham et al., 2014; von dem Hagen et al., 2014) and fusiform gyrus (Corbett et al., 2009; Critchley et al., 2000; Dalton et al., 2005; Pelphrey et al., 2007; Pierce et al., 2001) hypoactivation are also implicated in ASD during the perception of gaze (Baron-Cohen et al., 1999; Pinkham et al., 2008). In schizophrenia, disruptions in frontoparietal circuitry have been shown during eye movement paradigms, such as smooth eye pursuit and antisaccades (Dyckman et al., 2011; McDowell et al., 2002; Nagel et al., 2007; Rodrigue et al., 2018). Similar to ASD, perturbations in lateral prefrontal cortex, fusiform gyrus and amygdala are also shown in schizophrenia during gaze processing tasks (Kohler et al., 2010; Pinkham et al., 2011). Additionally, disruptions in frontotemporal and frontoparietal circuits have been shown in ASD and schizophrenia across broader social cognition tasks, such as face, emotion, and eye gaze processing (Barlati et al., 2020; Nair et al., 2020; Samaey et al., 2020). However, no imaging meta-analysis to date has examined if a shared neural mechanism underlies gaze dysfunction across these disorders.

1.2. Evaluating a Neurobiological Mechanism of Gaze Processing Impairments in ASD and Schizophrenia

The primary aim of the current study was to quantitatively summarize the existing imaging literature to identify convergent patterns of neural disruptions associated with gaze processing within ASD and within schizophrenia samples. Analyses assessed regions associated with aberrant activation in ASD and schizophrenia relative to unaffected controls. Sub-analyses were then conducted to test for the contribution of gaze processing paradigms and activation patterns (hyper- vs hypoactivation). Based on prior studies (Di Martino et al., 2009; Dickstein et al., 2013; McTeague et al., 2017; McTeague et al., 2020; Pinkham et al., 2008; Pinkham et al., 2011; Sasson et al., 2011), we hypothesized that ASD and schizophrenia samples would each show deficits in frontotemporal and frontoparietal circuitry implicated in social perception (amygdala, fusiform gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex) and cognitive control (lateral prefrontal cortex).

The second aim was to examine cross-disorder convergence in ASD and schizophrenia across domains of gaze processing. Thus, we pooled coordinates of differential activation across both disorders compared to controls to assess aberrant activation in hubs associated with gaze processing. Sub-analyses were conducted to test for the contribution of paradigms and patterns of hyper- vs hypoactivation. We hypothesized that disruptions in frontotemporal and frontoparietal circuitry would emerge as a convergent neural marker across disorders.

The third aim was to examine the connectivity and functionality of the identified activation clusters using meta-analytic connectivity modelling (MACM) and functional decoding with regions emerging as significant in ALE analysis. Here, MACM was conducted to identify patterns of coactivation with clusters resulting from the meta-analysis, which can then be described in terms of behavior constructs and linked to functional properties. Similarly, functional decoding was conducted on identified ALE clusters. Consistent with recent meta-analytic studies leveraging MACM and functional decoding (Buhle et al., 2014; Cortese et al., 2016; Kohn et al., 2014; Langner et al., 2018; Tahmasian et al., 2017), we used these approaches exploratorily to gain insight into the pathophysiology of gaze abnormalities in ASD and schizophrenia. Thus, we did not have a priori hypotheses for MACM and functional decoding given that these approaches served to interrogate regions emerging as significant.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Selection

The literature review and selection of manuscripts was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015). Functional MRI studies investigating the neural correlates of gaze processing in subjects with ASD or schizophrenia were identified through a literature search for functional neuroimaging (fMRI or Positron Emission Tomography) experiments examining eye gaze, eye movement, and gaze cueing conducted in ASD and/or schizophrenia samples (exact terms and detailed search strategy are in the Supplemental Methods). The search was conducted using the Cochrane, PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ERIC, and Sociological Abstracts databases as well as additional searches through reference lists of included studies. The web-based software platform Covidence (https://www.covidence.org) was used for independent title and abstract screening, full text review and data extraction. See Figure S1 for the PRISMA flow chart.

The inclusion criteria for studies were: 1) full text was written in English and published between January 1990 and December 2021 in a peer-reviewed journal; 2) measured brain function using task-based fMRI or blood flow positron emission tomography across domains of gaze processing; 3) examined ASD or schizophrenia vs healthy control contrasts; and 4) foci of significant activations were reported in standardized stereotaxic space (Talairach or Montreal Neurological Institute [MNI] atlases). Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) studies that used a region-of-interest (ROI) approach with a priori hypotheses related to specific regions, or 2) was a review or meta-analysis of other literature. Please note that only fMRI studies conducting analyses using a whole-brain approach (i.e., inclusion of a voxel-wise analysis with coordinates reported across the entire brain) were included in the current meta-analysis to avoid inflating or biasing significance for particular regions (Müller et al., 2018; Samea et al., 2019). Studies were also inspected to confirm that they reported results from independent samples. If overlapping samples were reported, data from only one report were included in the meta-analysis. Group-x-Condition interactions were included if studies provided relevant contrasts for sub-analyses.

After abstract screening, full texts were reviewed by two reviewers for inclusion (I.I.-S., M.V.). Disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer (K.I.). For all studies meeting inclusion criteria, data was extracted regarding sample characteristics, fMRI task design, statistical analyses, stereotaxic coordinates and statistical values of BOLD responses, and a summary of brain regions showing significant activation. A common coordinate system was used for the ALE meta-analysis, which was MNI space. Where relevant, stereotaxic coordinates of included studies using Talairach space were converted to MNI space prior to conducting the ALE analysis.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.2.1. Activation Likelihood Estimation.

A quantitative synthesis was conducted using Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) (Eickhoff et al., 2009). The revised ALE algorithm, implicated in MATLAB, was used to identify regions of spatial convergence of reported coordinates for ASD and schizophrenia vs healthy controls for gaze processing tasks that were higher than expected under a random spatial association across the whole brain (Eickhoff et al., 2012; Eickhoff et al., 2009; Turkeltaub et al., 2012). The ALE algorithm treats the reported foci as centers for 3D Gaussian probability distributions (not as single points) to capture the spatial uncertainty associated with each focus. The width of these uncertainty functions was determined based on empirical data on between-subject variance (i.e., uncertainty of spatial localizations between different subjects) and between-template variance (i.e., uncertainty of spatial localizations between different spatial normalization strategies). The between-subject and between-template variance represent the main components of this uncertainty. Importantly, the between-subject variance is weighted by the number of examined subjects per study, accommodating the notion that larger sample sizes should provide greater reliability and approximations of the true activation effect. The modelled uncertainty is scaled by the number of subjects to accommodate higher uncertainty of findings from smaller samples. The probabilities of all foci reported in each experiment were then aggregated for each voxel to create a modelled activation map for each experiment (Turkeltaub et al., 2012). The union across modelled activation maps yields voxel-wise ALE scores describing the convergence of results at each location of the brain. ALE scores were then compared to an analytically derived null-distribution. Thus, a random-effects inference was implemented. The resulting non-parametric p values were thresholded using a cluster-level family-wise-error-corrected p < 0.05 and a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.001, which were then transformed into Z scores for visualization.

To investigate neural markers of gaze impairment in ASD and schizophrenia, we pooled across coordinates for hypo- and hyperactivation for ASD/schizophrenia vs controls to identify Group-x-Condition interactions representing potential hubs of aberrant activation. ALE sub-analyses were then conducted for activation coordinates to identify patterns of hyperactivation (ASD/schizophrenia > controls) and hypoactivation (controls > ASD/schizophrenia). Subanalyses tested for the contribution of diagnostic group (ASD, schizophrenia), age (children vs adults), and paradigms (e.g., gaze cueing, gaze direction, face perception, saccades). Given that fMRI results tend to represent Group-x-Condition interactions, often with heterogeneous effects of the baseline condition, we reasoned that pooling hyper-/hypoactivation across domains of gaze processing would also circumvent concerns due to directionality of activation patterns masked by decreased activation of healthy controls in the paradigm control condition (i.e., increased activation in patients vs controls driven by decreased activation in controls at baseline). Sub-analyses were then conducted to further characterize directionality of activations by examining contributions of individual experiments or gaze domains and study characteristics to the observed clusters of convergence emerging as significant from the ALE analyses. It is important to note that we modelled analyses based on recent fMRI ALE meta-analytic studies of psychopathology leveraging a similar workflow for consistency in methodology and to facilitate comparison of findings (Cortese et al., 2016; Langner et al., 2018; McTeague et al., 2020; Morawetz et al., 2020).

2.3. Meta-Analytic Connectivity Modeling

Meta-analytic connectivity modeling (MACM) consists of testing whole-brain coactivation patterns of a seed region across large imaging datasets (Eickhoff et al., 2011; Laird et al., 2009). This approach identifies brain areas of coactivation above chance with a particular seed region (i.e., here, each region emerging from the primary ALE meta-analyses) across imaging experiments in the BrainMap database (Eickhoff et al., 2011). To conduct MACM, the BrainMap database was used, which includes coordinates of activation foci and meta-data for imaging studies (accessed April 2021, >20,000 studies at time of analysis). Consistent with prior work (Cortese et al., 2016; Kohn et al., 2014), we constrained MACM analyses to activations and experiments from normal mapping imaging studies (no interventions or group comparisons) in healthy participants. See the Supplemental Methods for more details.

For comparison of findings with recent meta-analytic connectivity work, we also conducted a modified version of MACM using the specific co-activation likelihood estimation algorithm (SCALE), which controls for the base rate (Langner and Camilleri, 2021; Langner et al., 2014). See the Supplemental Methods for more details. We reasoned that the heightened specificity of SCALE could be helpful for defining networks and informative for future studies of biomarkers that aim to develop targeted or neuroscience-informed treatments. While we primarily conducted MACM using the standard algorithm for consistency with prior ALE studies, we also present findings from both the standard MACM and revised algorithm (SCALE) for the interested reader.

2.4. Functional Decoding

To further unpack findings, functional decoding was performed on regions emerging as significant in the ALE analyses. Functional characterization of gaze processing derived clusters from the ALE analyses was based on ‘Behavioral Domain’ and ‘Paradigm Class’ meta-data categories available in the BrainMap database (Fox and Lancaster, 2002). We reasoned that leveraging the BrainMap database for functional decoding would allow comparison to other transdiagnostic studies of cognitive control networks based on the same database (Cortese et al., 2016; Yeo et al., 2015). Consistent with prior work (Cortese et al., 2016; Kohn et al., 2014), studies from BrainMap were included that reported experiments (i.e., within-group contrasts between two experimental conditions) in healthy participants. See the Supplemental Methods for more details.

2.5. Code and Data Availability

To promote data transparency, code and data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

The final set of experiments consisted of 56 experiments from 36 articles (see Figure S1 and Tables S1–S2 in the Supplemental Methods). This included 30 experiments with ASD patients and 26 experiments with schizophrenia patients. For ASD, this represented a total of 354 individuals with ASD (Mean age = 19.6 years; 86.4% males) and 348 healthy controls (Mean age = 19.5 years; 82.2% males). For schizophrenia, this represented a total of 275 individuals with schizophrenia (Mean age = 30.0 years, 70.6% males) and 265 healthy controls (Mean age = 29 years; 65.4% males). On the task level, ASD experiments represented the following gaze processing domains: gaze direction (n=12) and gaze cueing (n=18). Schizophrenia experiments represented the following gaze processing domains: saccades/antisaccades (n=10), smooth pursuit (n=13), and face perception (n=3). See Tables S1–S3 for a summary of medication status for participants.

3.2.1. Analyses Based on ASD

Within ASD studies (n=20), aberrant activation was observed in the left amygdala (Table 1 and Figure 1). Experiments with gaze cueing and gaze direction paradigms contributed to the convergence in the amygdala cluster. In addition, both child and adult samples contributed to this convergent finding. Aberrant amygdala activation was also characterized by patterns of hypo- and hyperactivation in ASD during gaze processing. Results of contribution sub-analyses are shown in Figure 1 inset and in Supplemental Table S4. As a follow-up, repeating all analyses with an alternative, potentially more liberal statistical threshold (i.e., threshold-free cluster enhancement [TFCE]) (Smith and Nichols, 2009), fully corroborated these amygdala results and revealed significant convergence in the right inferior frontal gyrus (see Supplemental Information).

Table 1.

Peak Coordinates of Clusters for Activation Within ASD and Schizophrenia versus Healthy Controls

| MNI Coordinates |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | BA H Cluster Size (mm3) | x | y | z | Z value | |

| Aberrant activation in ASD vs healthy controls | ||||||

| Amygdala | L | 720 | −24 | −6 | −20 | 4.2 |

| Aberrant activation in schizophrenia vs healthy controls | ||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 44/45R | 944 | 46 | 20 | 4 | 5.5 |

| Supplementary motor area | 6 R | 1368 | 2 | 8 | 54 | 5.7 |

Note. ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; BA = probable Brodmann area; H = hemisphere; L and R = left and right hemispheres, respectively; x, y, and z = the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively. Clusters denote the maximum peak value.

Figure 1.

Regions of aberrant activation within ASD during gaze processing. Aberrant activation in the left amygdala emerged in ASD. Sub-analyses pooled coordinates across hyper- and hypoactivation in ASD vs healthy controls. The right panel indicates the contribution of paradigm type or gaze subdomains, age group, and contrast (indicating hyper- vs hypoactivation in ASD) to the convergence on this region.

3.2.2. Analyses Based on Schizophrenia

Analyses were then conducted within schizophrenia studies (n=16), which showed aberrant activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus and right supplementary motor area (Table 1 and Figure 4). Saccade and face perception tasks contributed to convergence for the inferior frontal gyrus cluster, while predominately saccades tasks contributed to convergence for the supplementary motor area cluster. Both clusters were characterized by hypoactivation in schizophrenia vs controls (Supplemental Table S4). Follow-up analyses using TFCE revealed a highly similar pattern of convergence in the right inferior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area (see Supplemental Information).

Figure 4.

Aberrant activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area in schizophrenia during gaze processing. Sub-analyses pooled coordinates across hyper- and hypoactivation in schizophrenia vs healthy controls. The right panel indicates the contribution of paradigm type or gaze subdomains and contrast (indicating hyper- vs hypoactivation in schizophrenia) to the convergence on these regions.

3.3. Analyses Across ASD and Schizophrenia

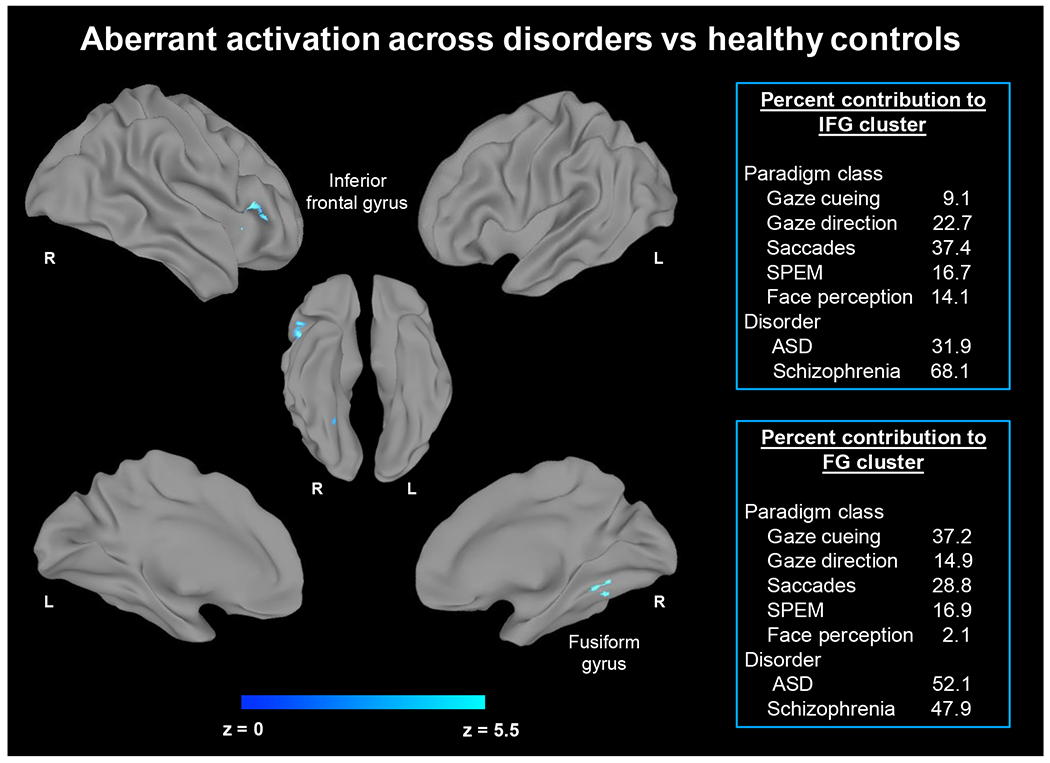

Next, we examined shared neural correlates of gaze processing pooling across disorders (n=20 for ASD and n=16 for schizophrenia). Aberrant patterns of activation were observed in the right inferior frontal gyrus and right fusiform gyrus (Figure 2). The corresponding clusters and Z values are shown in Table 2. Gaze cueing, gaze direction, saccadic and face perception tasks contributed to convergence (inset of Figure 2 and Supplemental Table S5). Importantly, data from both ASD and schizophrenia studies contributed to these clusters. Follow-up analyses using TFCE fully corroborated these findings and convergence in the right inferior frontal gyrus and fusiform gyrus (see Supplemental Information).

Figure 2.

Regions of aberrant activation across ASD and schizophrenia during gaze processing. Aberrant activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus and right fusiform gyrus emerged across ASD and schizophrenia. Primary ALE analyses pooled coordinates across hyper- and hypoactivation in ASD and schizophrenia vs healthy controls. The right panel indicates the contribution of gaze subdomains and disorder subgroups to the convergence on these regions.

Table 2.

Peak Coordinates of Clusters for Activation Pooled Across Disorders versus Healthy Controls

| MNI Coordinates |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | BAH Cluster Size (mm3) | x | y | z | Z value | |

| Aberrant activation across ASD and schizophrenia vs healthy controls | ||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 45 R | 1144 | 48 | 20 | 4 | 5.5 |

| Fusiform gyrus | 37 R | 744 | 30 | −52 | −14 | 4.5 |

| Hypoactivation across ASD and schizophrenia vs healthy controls | ||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 45 R | 1144 | 48 | 20 | 4 | 5.8 |

| Supplementary motor area | 6 R | 880 | 2 | 10 | 54 | 5.0 |

Note. ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; BA = probable Brodmann area; H = hemisphere; L and R = left and right hemispheres, respectively; x, y, and z = the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively. Clusters denote the maximum peak value.

Next, sub-analyses tested for convergent patterns of hyper- vs hypoactivation across ASD and schizophrenia (i.e., pooled across disorders) vs controls. Hypoactivation in ASD and schizophrenia was observed in the right inferior frontal gyrus and right supplementary motor area (Table 2 and Figure 3). Paradigms including gaze cueing and direction, saccades, and face perception contributed to convergence in both clusters (Supplemental Table S5). For the inferior frontal gyrus, both ASD and schizophrenia studies contributed to the convergence. For the supplementary motor area, predominately saccades tasks and schizophrenia samples contributed the most to convergence (Supplemental Table S5). Follow-up analyses using TFCE fully corroborated these findings and convergence in the right inferior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area (see Supplemental Information). No regions emerged as significant for convergent patterns of hyperactivation across disorders.

Figure 3.

Regions of disruption based on hypoactivation across ASD and schizophrenia during gaze processing. Hypoactivation in the right inferior frontal gyrus and right supplementary motor area emerged in ASD and schizophrenia. Sub-analyses pooled coordinates across gaze processing tasks and across ASD and schizophrenia vs healthy controls. The right panel indicates the contribution of gaze subdomains and disorder subgroups to the convergence on these regions.

As an additional check on our findings of shared disruption in the inferior frontal gyrus across ASD and schizophrenia during gaze processing, we conducted a conjunction analysis (i.e., ASD is different from controls and schizophrenia different from controls). A conjunction analysis of hypoactivation across both disorders showed a shared dysfunction in the right inferior frontal gyrus (see Supplemental Information Figure S12).

3.4. Meta-Analytic Connectivity Modeling (MACM)

To further explore the findings of the ALE analyses (Tables 1–2, Figures 1–3)—which includes volumes of interest for the left amygdala (MNI peak coordinates: −24, −6, −20), right inferior frontal gyrus (MNI peak coordinates: 48, 20, 4), right fusiform gyrus (MNI peak coordinates: 30, −52, −14), and supplementary motor area (MNI peak coordinates: 2, 10, 54)—we conducted MACM to identify coactivation with other regions. The functional coactivation patterns of each volume of interest are displayed in Figure 5. The amygdala showed convergent coactivation with the fusiform gyrus, subcortex (caudate, putamen, thalamus, hypothalamus), medial prefrontal cortex, lateral prefrontal cortex including the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortices, insula, middle temporal gyrus, and posterior cingulate. The inferior frontal gyrus showed convergent coactivation with the lateral prefrontal cortex, frontal eye fields, superior temporal gyrus, and parietal regions including the supramarginal gyrus. The fusiform gyrus showed convergent coactivation with the visual cortex, lateral prefrontal cortex including the inferior frontal gyrus, supplementary motor area, and parietal cortex including the angular gyrus. The supplementary motor area showed convergent coactivation with the lateral prefrontal cortex, frontal eye fields, fusiform gyrus, cerebellum, and parietal cortex. Details for all MACM results including peak clusters, coordinates and Z values are shown in Supplemental Tables S6–S9.

Figure 5.

Connectivity maps for the volumes of interest emerging as significant clusters in ALE analyses. Depicted are coactivation maps for the left amygdala (A), right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (B), the right fusiform gyrus (FG) (C), and the supplementary motor area (SMA) (D). For comparison of findings, results are also shown with a modified version of MACM using the specific co-activation likelihood estimation algorithm (SCALE). Coactivation patterns are labelled in blue and seed volumes of interest are labelled in yellow.

Repeating MACM analyses using the revised algorithm (SCALE) revealed a highly similar pattern of co-activation for each volume of interest (left amygdala, right inferior frontal gyrus, right fusiform gyrus, and supplementary motor area). The functional coactivation patterns of each volume of interest are displayed in Figure 5. As expected with SCALE, these patterns tended to be smaller relative to MACM, but aligned closely with similar frontoparietal, frontotemporal and frontolimbic circuitry as found with standard MACM. For the interested reader, details for all SCALE results including peak clusters, coordinates and Z values are also shown in Supplemental Tables S12–S15.

3.5. Functional Decoding

Functional decoding was then conducted on regions emerging as significant in the ALE analyses. The amygdala volume of interest was associated with domains related to emotion processing (including positive and negative emotions), sensory perception, and cognition (memory) (Figure 6A). The inferior frontal gyrus volume of interest was associated with domains related to cognition including music and language (e.g., music comprehension and production, speech and language, attention), emotion processing, perception and somesthesis, and audition (Figure 6B). The fusiform gyrus volume of interest was associated with domains related to action (e.g., motor learning, speech), visual perception, emotion processing, cognition (e.g., spatial perception, and executive function including memory) (Figure 6C). The supplementary motor area volume of interest was associated with domains related to visual perception, action (e.g., speech, motor, inhibition), and cognition (e.g., language and speech, music, spatial processing) (Figure 6D). For the interested reader, we also provide uncorrected and FDR corrected findings for each region (Supplemental Figures S2–S9).

Figure 6.

Functional characterization of the four core regions from the ALE meta-analysis. Behavioral domain meta-data from BrainMap were used for quantitative forward (left panels in A-D) and reverse (right panels in A-D) inference on significant functional associations of each region or volume of interest (corrected FDR < 0.05). Values at the bottom of each figure represent the likelihood of activation. For example, considering forward inference, 0.01 means that one in 100 studies features an activation in that particular cluster; for the significant domains/paradigms, their likelihoods are higher than the base rate. For reverse inference, the value represents the probability that this task was present given activation in that particular cluster.

3.6. Follow Up Supplemental Analyses of Gaze Task Domains

As a point of reference for the pooled analyses across domains of gaze processing, we also conducted exploratory term-based meta-analyses using Neurosynth (https://neurosynth.org) to identify the neural correlates for gaze domains included in the current study. Findings from Neurosynth show that the neural correlates of different task domains examined in the current study (using the terms: ‘gaze’, ‘eye movement’, ‘visual cueing’, ‘saccades’, and ‘face recognition’ for separate meta-analyses in Neurosynth) are similar to one another and elicit activation in frontoparietal and frontotemperal circuits spanning regions including the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices, sensorimotor cortex, supplementary motor area, fusiform gyrus, amygdala, and visual cortex. For the interested reader, we provide findings from these supplementary Neurosynth meta-analyses of gaze domains in the Supplemental Information. To complement this, we also include an overview of normative neural substrates implicated in gaze processing in the Supplement (see Supplemental Background: Brain Regions Involved in Gaze Processing).

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this meta-analysis was to examine convergent neural correlates of gaze processing impairments in ASD and schizophrenia. Analyses also tested cross-disorder convergence in ASD and schizophrenia across domains of gaze processing. Three key findings were observed. First, sub-analyses within each disorder identified convergence of disorder-specific patterns of aberrant activation in the amygdala for ASD and in the inferior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area for schizophrenia during the processing of gaze relative to unaffected controls. Second, aberrant activation was found in the inferior frontal gyrus across ASD and schizophrenia during gaze processing. As hypothesized, a pattern of aberrant activation in frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry—implicated in cognitive control and social perception—was observed in ASD and schizophrenia across domains of gaze processing. These findings may suggest deficits in the functional brain organization associated with gaze processing impairments in ASD and schizophrenia that spans emotion processing, cognitive control and sensorimotor processes.

4.1.1. Aberrant Activation of the Amygdala in ASD During Eye Gaze Processing

Primary analyses within ASD studies indicated aberrant amygdala activation, which is consistent with prior work implicating this region in social cognitive deficits. Social deficits of ASD are associated with disruptions in frontoparietal and frontotemporal networks involved in social cognition including the amygdala (Di Martino et al., 2009; Nomi and Uddin, 2015; Philip et al., 2012). The amygdala is also involved in the processing of eye gaze (Adams et al., 2003; Kawashima et al., 1999; Sato et al., 2004). In addition, amygdala hypoactivation has been implicated in ASD during the perception of gaze (Kliemann et al., 2012; Perlman et al., 2011; Sato et al., 2017; Tottenham et al., 2014; von dem Hagen et al., 2014). Our finding of aberrant amygdala activation in ASD is also notable in light of prior meta-analyses investigating broader social cognitive deficits in ASD (e.g., theory of mind, emotion processing, language/prosody processing). For instance, DiMartino et al. (2009) reported perturbed activation in the amygdala in ASD during social tasks relative to controls. A recent meta-analysis of ASD from Dickstein et al. (2013) observed a similar pattern of aberrant activation in the amygdala during social cognitive tasks. However, inspection of the contribution of the amygdala cluster of aberrant activation irrespective of directionality (Figure 1 and Table S4 in the supplement) indicated that patterns of hyper- and hypoactivation contrasts in autistic individuals contributed equally (51% and 48% of all contrasts, respectively), which suggests neural heterogeneity in response profiles. This heterogeneity has implications for identifying ASD subtypes that could also help inform personalized interventions (Lefort-Besnard et al., 2020).

While the amygdala is implicated in the processing of affect from faces (Fusar-Poli et al., 2009), empathic concern for others (Decety et al., 2008; Mutschler et al., 2013), and theory of mind (Di Martino et al., 2009), this region also plays a key role in mediating the cognitive control of emotion (Kohn et al., 2014; Ochsner et al., 2012; Pozzi et al., 2021). For instance, interactions between the amygdala and prefrontal control regions are involved in the top-down regulation of emotion (Buhle et al., 2014; Silvers et al., 2016). Similarly, aberrant activation of the amygdala is also reported in ASD during emotion regulation tasks involving reappraisal (Pitskel et al., 2014; Richey et al., 2015). Thus, our findings of amygdala hypoactivation during gaze processing may reflect disruptions in the recruitment of neural resources involved in the top-down regulation of emotion as well as alterations in the perceived salience of social vs non-social cues involving gaze. Alternatively, aberrant activation of the amygdala in ASD could indicate disruptions in the recruitment of attentional control processes associated with the modulation of emotion reactivity in response to social cues (e.g., direct eye gaze) (Ochsner and Gross, 2008; Powers and LaBar, 2019). It is also possible that deficits in processing gaze could be associated with impairments in mentalizing—specifically, in the ability to extract pertinent information for social communication from the face and/or eye region (Itier and Batty, 2009; Nation and Penny, 2008). In support of this, some gaze studies have found hypoactivation in frontotemporal and frontoparietal regions involved in theory of mind processes including the amygdala (Amodio and Frith, 2006; Frith and Frith, 1999; Frith and Frith, 2006; Frith, 2001; Gallagher and Frith, 2003; Saxe et al., 2004; Van Overwalle, 2011) when individuals with ASD were prompted to attend to the eye region (Georgescu et al., 2013; von dem Hagen et al., 2014). MACM analyses showed that amygdala activation converges with activation across social cognitive and cognitive control circuitry in the general population spanning regions in the lateral and medial prefrontal cortex as well as the subcortex. Given that the lateral and medial prefrontal cortex is involved in top-down biasing of information as socially relevant (Frith and Frith, 2012), atypical activation of the amygdala during gaze tasks may indicate broader deficits in social cognition that could be linked to deficits in gaze processing in ASD, particularly in deriving goal-directed intentions or saliency from gaze cues.

4.1.2. Aberrant Activation of the Inferior Frontal Gyrus and Supplementary Motor Area in Schizophrenia During Eye Gaze Processing

Analyses within schizophrenia indicated aberrant activation of the inferior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area. The current study is the first to examine the convergence of neural activation in schizophrenia across fMRI studies of eye gaze and movements. Thus, these findings are particularly important to promote future fMRI studies focusing on eye gaze in schizophrenia including antisaccade tasks. Antisaccade tasks, which recruit a range of cognitive control processes including goal-directed behavior, attention, working memory, learning, and decision-making (Hutton, 2008; Jamadar et al., 2013). Further, antisaccade deficits have been suggested as a potential endophenotype for schizophrenia (Benson et al., 2012; Caldani et al., 2017). Meta-analytic work implicates a fronto-striatal-parietal network in saccades (antisaccades, prosaccades) in healthy control populations including the parietal cortex and lateral prefrontal cortex/inferior frontal gyrus (Jamadar et al., 2013). Additionally, these frontoparietal regions functionally interact with cognitive control regions necessary for selecting, inhibiting, sequencing, and/or recalling correct responses (Jamadar et al., 2013; Jarvstad and Gilchrist, 2019; Sweeney et al., 2007), which have been implicated in the neuropathology underlying cognitive control difficulties in schizophrenia (Camchong et al., 2008; Carter et al., 2001; Perlstein et al., 2003; Weiss et al., 2007).

Our findings of aberrant activation in frontoparietal regions in schizophrenia relative to controls could indicate disruptions in early sensory and attentional processes after stimulus presentation. Because frontoparietal regions, including sensorimotor cortex and supplementary motor area, also have reciprocal connections with limbic and prefrontal regulatory regions, such as the dorsal and ventral prefrontal cortex, forming a frontoparietal and frontolimbic network that is tightly coupled with the cognitive control of emotion (Etkin et al., 2011), it is possible that top-down control of sensory and attentional processes are compromised during stimulus evaluation and response preparation in schizophrenia (Martínez et al., 2019; Perlstein et al., 2003). For instance, disruption of cognitive control networks could compromise executive control processes needed for proper task performance and/or saccade generation or inhibition (Brown and Braver, 2005; Clementz et al., 2007; Jamadar et al., 2013; Satterthwaite et al., 2007). Additionally, in schizophrenia, deficits in early visual processing are shown to contribute to impaired facial emotion processing (Martínez et al., 2018), and these impairments were more recently shown to have shared behavioral and neural dysfunction in the middle temporal complex in both individuals with ASD and schizophrenia (Martínez et al., 2019). Antisaccade tasks also involve executive functioning/response inhibition and emotion regulation processes (Jamadar et al., 2013), which represent subdomains of cognitive control that are consistently associated with deficits in the neural correlates of schizophrenia including emotion processing (Camchong et al., 2008).

4.2. Neural Markers of Gaze Impairments Across ASD and Schizophrenia

Aberrant activation was observed in the right inferior frontal gyrus across disorders compared to unaffected controls. The inferior frontal gyrus is implicated in social perception and cognitive processes (Dal Monte et al., 2014; Fusar-Poli et al., 2009) including processing negative affect (Hariri et al., 2000; Hariri et al., 2003), empathy (Lamm et al., 2011), emotion regulation (Buhle et al., 2014; Silvers et al., 2016), mentalization (Dal Monte et al., 2014), biological motion (Kaiser et al., 2010), evaluation of trustworthiness (Pinkham et al., 2008), and gaze perception (Davies et al., 2011). In line with these findings, functional decoding suggested that this region may be linked to domains of cognition and sensory perception. MACM analyses indicated that activation of this inferior frontal gyrus cluster converges with activation across cognitive control circuitry in the general population, which spans the lateral prefrontal cortex, sensorimotor regions including the supplementary motor area, insula, and the parietal cortex. These findings also reflect the vast cortico-cortical connections of the inferior frontal gyrus and aligns with prior studies emphasizing the rich interconnectedness of this region (Aron et al., 2014).

Additionally, the inferior frontal gyrus is involved in cognitive control processes including emotion regulation (Kohn et al., 2014) and response inhibition (Aron et al., 2014). The inferior frontal gyrus also plays a salient role in the inhibition of the prepotent prosaccade response in gaze tasks including saccades/antisaccades (Hung et al., 2018; Jamadar et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017). This is relevant to the current work since several studies utilized gaze tasks involving fixation on a target in the presence of distractor stimuli. Since the inferior frontal gyrus—particularly the right hemisphere—is thought to act as a ‘brake’ over response tendencies (Aron et al., 2014), it is possible that disruption of the inferior frontal gyrus in ASD and schizophrenia could hinder processing of socially and emotionally salient stimuli. However, it is also important to note that hypoactivation of the inferior frontal gyrus has been found in other psychiatric disorders including Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder during tasks of inhibitory control (Cortese et al., 2016; Samea et al., 2019), potentially indicating a transdiagnostic implication of the lateral prefrontal cortex beyond ASD and schizophrenia. Future longitudinal studies will also be important to assess the timing effects associated with inferior frontal gyrus pathophysiology in ASD and schizophrenia as well as transdiagnostically in other psychiatric disorders.

Aberrant activation was also observed in the right fusiform gyrus across disorders relative to controls. The fusiform gyrus is associated with face processing (Kanwisher et al., 1997), gaze perception (Boyarskaya et al., 2015; Hooker et al., 2003; Madipakkam et al., 2015; Pageler et al., 2003; Zurcher et al., 2013) and attention to gaze (Nummenmaa and Calder, 2009). Activation of the fusiform gyrus has been implicated in expertise for distinguishing objects (Foss-Feig et al., 2016; Gauthier and Tarr, 2002; McGugin et al., 2014), mental state attribution tasks (Castelli et al., 2000), and visuo-attentional and perceptual processes (Dolcos et al., 2020). In ASD, a vast neuroimaging literature implicates fusiform gyrus dysfunction with social and gaze impairments (Corbett et al., 2009; Critchley et al., 2000; Dalton et al., 2005; Di Martino et al., 2009; Dickstein et al., 2013; Hooker et al., 2003; Pelphrey et al., 2007; Pierce et al., 2001). Similarly, in schizophrenia, studies report aberrant activation of the fusiform gyrus during social cognitive (Pinkham et al., 2008) and face emotion processing (Quintana et al., 2003) tasks, as well as during eye saccades (Tregellas et al., 2004) and attentional control (Hahn et al., 2021; Maher et al., 2016). In support of this, functional decoding suggested that this fusiform gyrus region may be linked to domains of spatial cognition, sensorimotor learning, emotion perception, and visual processing in the general population. In line with recent work suggesting a role of the fusiform gyrus beyond face processing, findings from MACM analyses indicated that activation of this region converges with activation across the visual cortex, lateral prefrontal cortex, sensorimotor cortex, and parietal regions. It is possible that our findings of fusiform gyrus dysfunction could reflect a disorder-general, transdiagnostic marker of impaired attentional control aspects of gaze processing (e.g., impaired attentional filtering leading to hypo- or hyperfocusing on stimuli), which may hinder social functioning and cognitive control processes.

Contribution sub-analyses indicated that hypoactivation in the supplementary motor area was largely driven by schizophrenia studies. In addition to controlling volitional aspects of motor movements (Nachev et al., 2008), sensorimotor regions, including the supplementary motor area, are also implicated in the affective aspect of social cognition (Pozzi et al., 2020; Schurz et al., 2020). In support of this, functional decoding indicated a broad domain of function associated with the supplementary motor area including aspects of cognition (i.e., language and spatial processing), cognitive control including inhibitory control, and visual perception. Additionally, findings from MACM analyses indicated that activation of this region converges with activation across the lateral prefrontal cortex and parietal regions implicated in cognitive control—such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus. Impairment of the supplementary motor area has also been identified as a hub of cortico-basal ganglia network dysfunction related to disturbances in volitional motor control in schizophrenia (Bracht et al., 2013). Further, perturbations in supplementary motor area volume are associated with impaired executive functioning in schizophrenia (Exner et al., 2006; Stegmayer et al., 2014). Here, it is possible that aberrant activation of the supplementary motor area during gaze processing may reflect broader cognitive control dysfunction in schizophrenia. In support of this, a meta-analysis found that hypoactivation of the supplementary motor area was associated with executive function impairments in schizophrenia (Wu and Jiang, 2020). Given that recent work implicates associations between cognitive dysfunction and sensorimotor dysconnectivity and structure across mental disorders, particularly schizophrenia (Kebets et al., 2019; Parkes et al., 2021), our results also converge on the notion that disruptions in lower-order brain systems could be disorder-general biomarkers linked to cognitive control deficits.

As a point of reference for interpreting the main ALE findings, supplemental and exploratory meta-analyses were conducted for terms used in the current study. Regions identified in the Neurosynth meta-analysis indicated preferential activation across domains of gaze processing within similar circuitry (frontoparietal, frontotemporal) identified in the current study that spans the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices, sensorimotor cortex, fusiform gyrus, amygdala, and visual cortex (see Supplemental Information). Thus, despite the heterogeneity of tasks across ASD and schizophrenia, these gaze domains were shown to elicit activation in similar frontoparietal and frontotemporal networks, which suggests shared neural circuitry implicated in gaze processing.

Given recent work leveraging a dimensional framework to understand domains of psychopathology that map onto brain circuits (Casey et al., 2014; Insel and Cuthbert, 2015), it is possible that disruptions in frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry during gaze processing may converge on shared clinical symptoms in ASD (e.g., core deficits in social communication and interaction including nonverbal communication and mentalizing) and schizophrenia (e.g., negative symptoms). Indeed, deficits in eye gaze and mentalizing in ASD as well as negative symptoms in schizophrenia have been associated with dysconnectivity in frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry (Davies et al., 2011; Di Martino et al., 2009; Dickstein et al., 2013; Ibrahim et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2020; Tu et al., 2013). Alternatively, recent models of psychopathology have integrated a dimensional framework with the goal of reconceptualizing mental health to addresses challenges of diagnostic heterogeneity, comorbidity, and unreliability (Kotov et al., 2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy Of Psychopathology (HiTOP) was developed to address these aforementioned challenges across psychopathology (Kotov et al., 2022; Kotov et al., 2017; Kotov et al., 2021). Thus, altered lateral prefrontal cortex activation—spanning frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry—during gaze processing could also suggest a common etiological risk factor such as thought problems (e.g., disorganization, reality distortion) or detachment (e.g., reduced emotional expression, avolition, lack of social motivation and appropriate social interactions) as defined by the HiTOP model (Kotov et al., 2022; Kotov et al., 2021). However, ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders are not currently included in the HiTOP model. Therefore, future work will be important to understand the link between impairments in social functioning and cognitive control domains, and network dysfunction across frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuits beyond categorial diagnoses of ASD and schizophrenia and along a dimensional continuum or framework.

4.3. Study Limitations

Some limitations should be considered. First, inherent to all meta-analyses, there is the potential role of publication bias because we could only include published studies. Second, our data do not provide information on the causal relationship between social cognitive and cognitive control networks, and gaze impairments in ASD and schizophrenia. Third, there were relatively fewer studies in schizophrenia relative to ASD, emphasizing the need for future studies in schizophrenia that leverage a range of eye gaze tasks (Tso et al., 2020). Additionally, sub-analyses could not be conducted within experiments using the same paradigms due to limited sample size. While future studies directly comparing the neural correlates of eye gaze dysfunction in ASD and schizophrenia using homogenous paradigms are ideal, this was not possible due to sample size considerations. However, follow up analyses using Neurosynth indicated synergy across gaze processing domains examined in the current study, with activation emerging in similar frontoparietal and frontotemporal networks (see Supplemental Information). Despite task heterogeneity, prior meta-analyses have combined across broader social perception tasks encompassing both lower- and higher-order social cognitive processes, showing that integrating a range of paradigms can help advance development of biomarkers (Hajdúk et al., 2022). We did conduct supplementary analyses restricted to adult samples across ASD and schizophrenia, which showed a highly similar pattern of convergence as the findings in the right inferior frontal gyrus (Supplemental Results Figure S10 and Table S10). Thus, we were able to replicate findings in a relatively homogeneous sample of adults. While there was heterogeneity of paradigms and samples (adult vs child) across the combined ASD and schizophrenia studies, the omnibus meta-analysis was well powered as a supplemental analysis with 36 studies and 56 experiments. This cross-disorder supplemental analysis was intended to inform future work and advance understanding of transdiagnostic neural disruptions in social perception and cognitive control circuitry in clinical samples. Fourth, ASD studies included children and adults (vs adults only in schizophrenia studies). Developmental aspects may affect activation patterns reported here and future longitudinal work will be necessary to understand how age-related differences map onto neural deviations and symptom trajectories. However, we relied on the contrast of ASD vs controls and imaging data from age-matched controls to control for developmental effects. Fifth, most participants with schizophrenia were taking psychotropic medications, while the majority of ASD studies did not report psychotropic medication status. There is evidence that psychotropic medications may have long-term effects on brain function and structure in ASD and schizophrenia (Chopra et al., 2021; Fusar-Poli et al., 2013; Linke et al., 2017), but it was not possible to establish the extent to which our results were influenced by medication effects. Additionally, potentially influential factors beyond medication types, such as illness duration and/or severity and comorbidities, could not be assessed because of inconsistent reporting across studies. Sixth, while there are other statistical packages for conducting coordinate-based meta-analyses (e.g., MKDA), we selected ALE for comparison to recent meta-analyses in ASD (Di Martino et al., 2009; Dickstein et al., 2013) and schizophrenia (Sugranyes et al., 2011). Future studies may also consider conducting mega-analyses in which raw functional and/or structural MRI data are pooled across studies and sites. Nevertheless, our meta-analysis can provide a map of anatomical regions (e.g., a priori regions-of-interest) for testing causal implications in such mega-analyses. Lastly, we acknowledge that MACM and functional decoding refer to healthy populations and do not necessarily clarify coactivations or possible functionality of the clusters as related to mental health conditions. Nonetheless, MACM and functional decoding are commonly used approaches in imaging meta-analyses for further exploring and contextualizing regions emerging as significant and associated cognitive processes (Cortese et al., 2016; Kohn et al., 2014; Morawetz et al., 2020), especially in the context of the RDoC framework in which biobehavioral dimensions and symptom domains are thought to occur along continua in the population (Casey et al., 2014; Ibrahim and Sukhodolsky, 2018). Related to this, we also acknowledge the challenges in accounting for phenotypic multifinality in the current meta-analysis: that is, potential differences in behavioral and/or cognitive abnormalities in ASD and schizophrenia within a given domain (e.g., differential performance on eye gaze tasks or executive functioning) may converge on shared neurobiological substrates. Stated differently, heterogeneity in disruptions in behavioral and/or cognitive domains could also reflect multiple paths to the same outcome (in this case, alterations in frontoparietal and frontotemporal circuitry implicated in gaze processing), termed “equifinality” (Cicchetti and Rogosch, 1996; Giedd et al., 2015; Simmons et al., 2019). Thus, it will be important for future work to examine subgroups of ASD and schizophrenia based on cognitive domains or abnormalities that may be associated with neural heterogeneity or unique brain-based markers of gaze processing deficits. The use of a transdiagnostic approach may also contribute to elucidating neural heterogeneity related to gaze impairments.

Given the increasing shift toward transdiagnostic research related to social cognition leveraging the NIMH Research Domain Criteria framework (Barlati et al., 2020; Gur and Gur, 2016; Tso et al., 2020), future work is needed to examine social cognitive impairments across a range of psychiatric conditions. Because impaired social cognitive functioning, including aberrant eye gaze perception, are symptoms common in multiple psychiatric conditions (Cotter et al., 2018), task-based imaging studies will be important to explicitly test social cognitive networks in other disorders such as disruptive behavior disorders and anxiety disorders.

4.4. Conclusion

The current ALE meta-analysis examined underlying neural mechanisms associated with gaze processing in ASD and schizophrenia. In autistic individuals, altered amygdala activation was found during eye gaze processing, which may reflect disruptions in the recruitment of ‘social brain’ circuitry and neural resources involved in social cognition including mentalizing, emotion regulation, and/or attentional control. Cross-disorder analyses revealed aberrant activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus and fusiform gyrus in ASD and schizophrenia across domains of gaze processing. Shared features of neural dysfunction may be related to abnormal gaze processing, particularly in large-scale networks involved in social cognition and cognitive control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

K.I. is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23-MH128451). This work was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant KL2 TR001862 (K.I.) and TL1 TR001864 (K.I.), a Yale Child Study Center Junior Faculty Development Pilot Award (K.I.), and the Yale Child Study Center Translational Developmental Neuroscience Training Program (T32 MH18268) (K.I.). S.B.E. is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (grant agreements 945539 (HBP SGA3) and 826421 (VBC), the National Institute of Health (R01-MH074457) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 1451 and IRTG 2150). We thank Ms. Carolyn Marsh, Ms. Kimberly Cimino, and Mr. Anthony Anzano for their assistance with the literature search and review, and Ms. Julia Zhong at the Yale Child Study Center for her assistance with reviewing the final version of the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Vermetha Polite of the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library for technical support.

Role of the Funding Source

Financial support for the conduct of this research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23-MH128451; PI: K.I.), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant KL2 TR001862 (K.I.), TL1 TR001864 (K.I.), a Yale Child Study Center Junior Faculty Development Pilot Award (K.I.), and the Yale Child Study Center Translational Developmental Neuroscience Training Program (T32 MH18268) (K.I.). The funding sources were not involved the preparation of the article or in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO CRD42021239132

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing interests.

Preprint Servers

A version of this manuscript was posted as a preprint on Research Square. The authors retain full copyright. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2297758/v1

References

- Adams RB Jr., Gordon HL, Baird AA, Ambady N, Kleck RE, 2003. Effects of gaze on amygdala sensitivity to anger and fear faces. Science (New York, N.Y.) 300(5625), 1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Author, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Amodio DM, Frith CD, 2006. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 7(4), 268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA, 2014. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends in cognitive sciences 18(4), 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas D, Van’t Wout M, Aleman A, Kahn R, 2008. Social judgement in clinically stable patients with schizophrenia and healthy relatives: behavioural evidence of social brain dysfunction. Psychological medicine 38(5), 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlati S, Minelli A, Ceraso A, Nibbio G, Carvalho Silva R, Deste G, Turrina C, Vita A, 2020. Social cognition in a research domain criteria perspective: a bridge between schizophrenia and autism spectra disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11, 806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Leslie A, Frith U, 1985. Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition 21(1), 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Ring H, Wheelwright S, Bullmore E, Brammer M, Simmons A, Williams S, 1999. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: an fMRI study. The European journal of neuroscience 11(6), 1891–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PJ, Beedie SA, Shephard E, Giegling I, Rujescu D, Clair DS, 2012. Simple viewing tests can detect eye movement abnormalities that distinguish schizophrenia cases from controls with exceptional accuracy. Biological psychiatry 72(9), 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliksted V, Ubukata S, Koelkebeck K, 2016. Discriminating autism spectrum disorders from schizophrenia by investigation of mental state attribution on an on-line mentalizing task: A review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia research 171(1-3), 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C, 2009. Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophrenia research 109(1-3), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyarskaya E, Sebastian A, Bauermann T, Hecht H, Tuscher O, 2015. The Mona Lisa effect: neural correlates of centered and off-centered gaze. Hum Brain Mapp 36(2), 619–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracht T, Schnell S, Federspiel A, Razavi N, Horn H, Strik W, Wiest R, Dierks T, Müller TJ, Walther S, 2013. Altered cortico-basal ganglia motor pathways reflect reduced volitional motor activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research 143(2-3), 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke J, Kay DD, Lee KS, Green MF, 2005. Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research 80(2-3), 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Braver TS, 2005. Learned predictions of error likelihood in the anterior cingulate cortex. Science (New York, N.Y.) 307(5712), 1118–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhle JT, Silvers JA, Wager TD, Lopez R, Onyemekwu C, Kober H, Weber J, Ochsner KN, 2014. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cerebral cortex 24(11), 2981–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldani S, Bucci MP, Lamy J-C, Seassau M, Bendjemaa N, Gadel R, Gaillard R, Krebs M-O, Amado I, 2017. Saccadic eye movements as markers of schizophrenia spectrum: exploration in at-risk mental states. Schizophrenia research 181, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camchong J, Dyckman KA, Austin BP, Clementz BA, McDowell JE, 2008. Common neural circuitry supporting volitional saccades and its disruption in schizophrenia patients and relatives. Biological Psychiatry 64(12), 1042–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, MacDonald AW III, Ross LL, Stenger VA, 2001. Anterior cingulate cortex activity and impaired self-monitoring of performance in patients with schizophrenia: an event-related fMRI study. American Journal of Psychiatry 158(9), 1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey B, Oliveri ME, Insel T, 2014. A neurodevelopmental perspective on the research domain criteria (RDoC) framework. Biological psychiatry 76(5), 350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli F, Happe F, Frith U, Frith C, 2000. Movement and mind: a functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. NeuroImage 12(3), 314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S, Fornito A, Francey SM, O’Donoghue B, Cropley V, Nelson B, Graham J, Baldwin L, Tahtalian S, Yuen HP, 2021. Differentiating the effect of antipsychotic medication and illness on brain volume reductions in first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal, randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled MRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology 46(8), 1494–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YS, Barch D, Strube M, 2014. A meta-analysis of mentalizing impairments in adults with schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder. Schizophrenia bulletin 40(3), 602–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, 1996. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and psychopathology 8(4), 597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Clementz BA, Brahmbhatt SB, McDowell JE, Brown R, Sweeney JA, 2007. When does the brain inform the eyes whether and where to move? An EEG study in humans. Cerebral Cortex 17(11), 2634–2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Carmean V, Ravizza S, Wendelken C, Henry ML, Carter C, Rivera SM, 2009. A functional and structural study of emotion and face processing in children with autism. Psychiatry Res 173(3), 196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Castellanos FX, Eickhoff CR, D’Acunto G, Masi G, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB, 2016. Functional decoding and meta-analytic connectivity modeling in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry 80(12), 896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter J, Granger K, Backx R, Hobbs M, Looi CY, Barnett JH, 2018. Social cognitive dysfunction as a clinical marker: a systematic review of meta-analyses across 30 clinical conditions. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 84, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley H, Daly EM, Bullmore ET, Williams SC, Van Amelsvoort T, Robertson DM, Rowe A, Phillips M, McAlonan G, Howlin P, Murphy DG, 2000. The functional neuroanatomy of social behaviour: changes in cerebral blood flow when people with autistic disorder process facial expressions. Brain : a journal of neurology 123(Pt 11), 2203–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Monte O, Schintu S, Pardini M, Berti A, Wassermann EM, Grafman J, Krueger F, 2014. The left inferior frontal gyrus is crucial for reading the mind in the eyes: Brain lesion evidence. Cortex 58, 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton KM, Nacewicz BM, Johnstone T, Schaefer HS, Gernsbacher MA, Goldsmith HH, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ, 2005. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience 8(4), 519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MS, Dapretto M, Sigman M, Sepeta L, Bookheimer SY, 2011. Neural bases of gaze and emotion processing in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain and behavior 1(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, Akitsuki Y, 2008. Who caused the pain? An fMRI investigation of empathy and intentionality in children. Neuropsychologia 46(11), 2607–2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Ross K, Uddin LQ, Sklar AB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP, 2009. Functional brain correlates of social and nonsocial processes in autism spectrum disorders: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry 65(1), 63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Pescosolido MF, Reidy BL, Galvan T, Kim KL, Seymour KE, Laird AR, Di Martino A, Barrett RP, 2013. Developmental meta-analysis of the functional neural correlates of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 52(3), 279–289. e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F, Katsumi Y, Shen C, Bogdan PC, Jun S, Larsen R, Heller W, Bost KF, Dolcos S, 2020. The impact of focused attention on emotional experience: a functional MRI investigation. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 20(5), 1011–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyckman KA, Lee AK, Agam Y, Vangel M, Goff DC, Barton JJ, Manoach DS, 2011. Abnormally persistent fMRI activation during antisaccades in schizophrenia: a neural correlate of perseveration? Schizophrenia research 132(1), 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Bahorik AL, McKnight SA, Hogarty SS, Greenwald DP, Newhill CE, Phillips ML, Keshavan MS, Minshew NJ, 2013. Commonalities in social and non-social cognitive impairments in adults with autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research 148(1-3), 24–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Mermon DE, Montrose DM, Miewald J, Gur RE, Gur RC, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS, 2010. Social cognition deficits among individuals at familial high risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin 36(6), 1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Kurth F, Fox PT, 2012. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. Neuroimage 59(3), 2349–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Roski C, Caspers S, Zilles K, Fox PT, 2011. Co-activation patterns distinguish cortical modules, their connectivity and functional differentiation. Neuroimage 57(3), 938–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT, 2009. Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: A random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Human brain mapping 30(9), 2907–2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R, 2011. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 15(2), 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner C, Weniger G, Schmidt-Samoa C, Irle E, 2006. Reduced size of the pre-supplementary motor cortex and impaired motor sequence learning in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research 84(2-3), 386–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes JM, Cajão R, Lopes R, Jerónimo R, Barahona-Corrêa JB, 2018. Social cognition in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Frontiers in psychiatry 9, 504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss-Feig JH, McGugin RW, Gauthier I, Mash LE, Ventola P, Cascio CJ, 2016. A functional neuroimaging study of fusiform response to restricted interests in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders 8(1), 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Lancaster JL, 2002. Mapping context and content: the BrainMap model. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 3(4), 319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Strauss M, Klingemier EW, Zetzer EE, Hardan AY, Eng C, Youngstrom EA, 2017. A meta-analysis of gaze differences to social and nonsocial information between individuals with and without autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 56(7), 546–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C, Frith U, 1999. Interacting minds--a biological basis. Science (New York, N.Y.) 286(5445), 1692–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C, Frith U, 2012. Mechanisms of social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 63, 287–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Frith U, 2006. The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron 50(4), 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U, 2001. Mind blindness and the brain in autism. Neuron 32(6), 969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Placentino A, Carletti F, Landi P, Allen P, Surguladze S, Benedetti F, Abbamonte M, Gasparotti R, Barale F, 2009. Functional atlas of emotional faces processing: a voxel-based meta-analysis of 105 functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Smieskova R, Kempton M, Ho B, Andreasen N, Borgwardt S, 2013. Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 37(8), 1680–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Frith CD, 2003. Functional imaging of ‘theory of mind’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7(2), 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier I, Tarr MJ, 2002. Unraveling mechanisms for expert object recognition: bridging brain activity and behavior. Journal of experimental psychology. Human perception and performance 28(2), 431–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu AL, Kuzmanovic B, Schilbach L, Tepest R, Kulbida R, Bente G, Vogeley K, 2013. Neural correlates of “social gaze” processing in high-functioning autism under systematic variation of gaze duration. Neuroimage. Clinical 3, 340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Raznahan A, Alexander-Bloch A, Schmitt E, Gogtay N, Rapoport JL, 2015. Child psychiatry branch of the National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal structural magnetic resonance imaging study of human brain development. Neuropsychopharmacology 40(1), 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Gur RE, 2016. Social cognition as an RDoC domain. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 171(1), 132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B, Robinson BM, Kiat JE, Geng J, Bansal S, Luck SJ, Gold JM, 2021. Impaired Filtering and Hyperfocusing: Neural Evidence for Distinct Selective Attention Abnormalities in People with Schizophrenia. Cerebral Cortex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdúk M, Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Harvey PD, Sasson NJ, 2022. Heterogeneity of social cognitive performance in autism and schizophrenia. Autism Research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Bookheimer SY, Mazziotta JC, 2000. Modulating emotional responses: effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. Neuroreport 11(1), 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Fera F, Weinberger DR, 2003. Neocortical modulation of the amygdala response to fearful stimuli. Biol Psychiatry 53(6), 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haut KM, MacDonald AW III, 2010. Persecutory delusions and the perception of trustworthiness in unfamiliar faces in schizophrenia. Psychiatry research 178(3), 456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker CI, Paller KA, Gitelman DR, Parrish TB, Mesulam MM, Reber PJ, 2003. Brain networks for analyzing eye gaze. Brain research. Cognitive brain research 17(2), 406–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung Y, Gaillard SL, Yarmak P, Arsalidou M, 2018. Dissociations of cognitive inhibition, response inhibition, and emotional interference: Voxelwise ALE meta-analyses of fMRI studies. Human brain mapping 39(10), 4065–4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton SB, 2008. Cognitive control of saccadic eye movements. Brain and cognition 68(3), 327–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]