Abstract

Upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is an uncommon malignancy involving the renal pelvis and ureter. Careful pathological analysis plays a critical role in the diagnosis and clinical management of UTUC. In combination with clinical and radiological evaluation, pathological features can be used to stratify patients into low-risk and high-risk groups. This risk stratification can help clinicians select the optimal treatment for patients with UTUC, such as kidney-sparing (conservative) treatment, radical nephroureterectomy or ureterectomy, and perioperative systemic therapy. However, due to the technical difficulty of obtaining sufficient tissue from the upper urinary tract, it is often challenging for pathologists to accurately grade the tumor and assess tumor invasion in small biopsy specimens. Although the majority of UTUCs are pure urothelial carcinoma, a considerable subset of UTUCs shows histological subtypes or divergent differentiation. Recent studies have identified genetically distinct molecular subtypes of UTUC by examining DNA, RNA, and protein expression profiles. The prognosis of pT3 UTUC, particularly renal pelvic UC, remains controversial, and several studies have proposed subclassification of pT3 UTUC. Lynch syndrome is a significant risk factor for UTUC, and screening tests may be considered in young patients and those with familial histories of the disease. Despite significant progress in recent years, several issues remain to be addressed in the pathological diagnosis, molecular classification, and treatment of UTUC.

Keywords: Upper urinary tract, urothelial carcinoma, histological subtype, Lynch syndrome, molecular classification, pathological staging

Introduction

Upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is a rare malignancy that arises in the renal pelvis and ureter (Figure 1). The annual incidence is estimated to be 1–2 cases per 100,000 people in Western countries, accounting for approximately 5–10% of urothelial cancer cases (1). However, approximately 60% of UTUC cases are invasive at initial presentation, and approximately 7% have already metastasized at the time of diagnosis (2, 3). The incidence has increased in the past decades due to improved detection by imaging/endoscopic techniques and improved cancer survival due to novel therapies (2–5).

Figure 1.

Gross specimens of radical nephroureterectomy show urothelial carcinoma in the renal pelvis (A) with invasion into the renal parenchyma and in the ureter (B).

Careful pathological analysis plays a critical role in the diagnosis and clinical management of UTUC. In combination with clinical and radiological evaluations, careful pathologic assessment of UTUC can be used to stratify patients into low-risk and high-risk groups (Table 1) (3). This risk stratification can help clinicians identify patients who are likely to benefit from different treatments, such as kidney-sparing (conservative) treatment, radical nephroureterectomy, and ureterectomy, and consider perioperative systemic therapy(6). Furthermore, pathological findings of UTUC in surgical resection specimens provide essential information for prognosis and post-operative systemic therapy. These pathological findings include tumor grade, stage, location, size, multifocality, histological subtype, lymph node involvement, lymphovascular invasion, and surgical margins. In addition, other pathological features have been reported as prognostic factors for UTUC, such as tumor necrosis, sessile growth pattern, concomitant carcinoma in situ (CIS) in organ-confined UTUC, and history of bladder CIS (7–9). All these features are associated with higher risk of recurrence and poorer outcome and should be part of the standard pathologic report.

Table 1.

Risk stratification of nonmetastatic upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). This is adapted from “European Association of Urology Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma (2023 Update)”(3).

| Low-Risk UTUC | High-Risk UTUC |

|---|---|

|

| |

| • Unifocal disease | • Multifocal disease |

| • Tumor size < 2 cm | • Tumor size ≥ 2 cm |

| • Negative for high-grade cytology | • High-grade cytology |

| • Low-grade biopsy | • High-grade biopsy |

| • No invasive aspect on CT | • Local invasion on CT |

| • Hydronephrosis | |

| • Previous radical cystectomy for | |

| • high-grade bladder cancer | |

| • Histology subtypes | |

| *All these factors need to be present. | *Any one of these factors needs to be present. |

In this review, we discuss recent advances in the pathology of UTUC, including diagnostic challenges in the evaluation of biopsy specimens, histological subtypes, molecular classification, subclassification of pT3 UTUC, and its association with Lynch syndrome.

Diagnostic Challenges in UTUC biopsy specimens

Diagnostic flexible ureteroscopy has been widely used for the diagnosis of UTUC by directly visualizing the upper urinary tract and performing biopsies of suspicious lesions or cytologic sampling (3). This procedure can determine the presence, appearance, multifocality, and size of tumors. Meanwhile, the histological grade of tumor determined by biopsy is often used for clinical decision-making, as it is strongly associated with the pathological stage. Similar to urinary bladder, papillary neoplasms in the upper urinary tract are classified as urothelial papilloma, papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP), low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, and high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Because of technical difficulties in obtaining sufficient tissue from the upper urinary tract, it is often challenging for pathologists to accurately grade the tumor and assess the invasion on biopsy (10–12). Other factors, such as large tumor size, histological heterogeneity, superficial sampling, and cautery artifact, also contribute to the diagnostic difficulty (Figure 2).

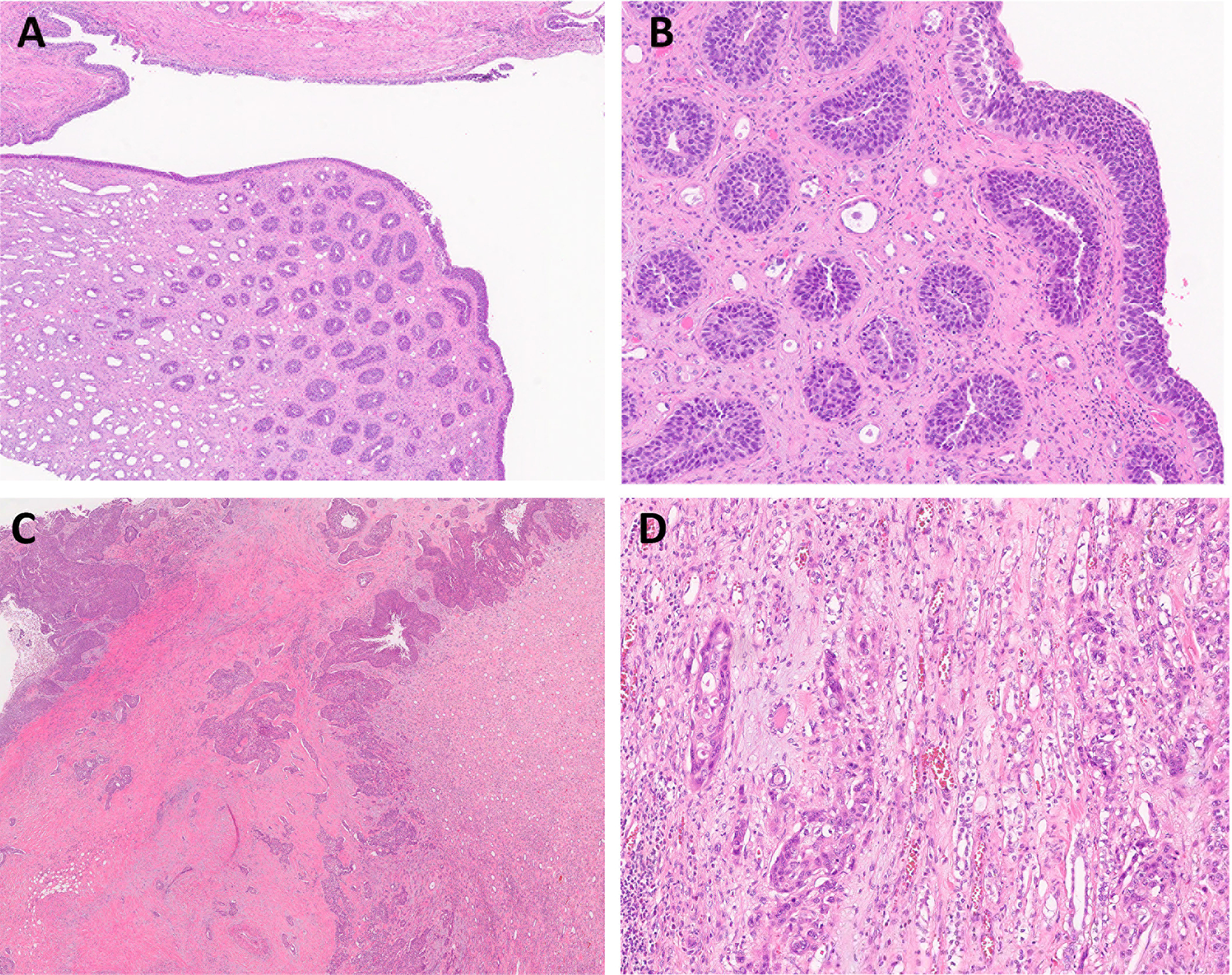

Figure 2.

UTUC shows histological heterogeneity with mixed low-grade and high-grade components. (A) Low-power view of high-grade papillary UC of the renal pelvis (magnification ×5). (B) Low-grade (on the left) with adjacent high-grade (on the right) UC components. (C) Low-grade UC component in the same tumor. (D) High-grade UC component in the same tumor. (B, C, D: magnification ×100)

Although the concordance of tumor grading between the biopsy and surgical resection specimens is relatively high, ranging from 63% to 92.6%, the invasive component of invasive UTUC is often missed in superficial small biopsy specimens (10, 13). Case series in the literature have reported discrepancies ranging from 16–50%, wherein tumors are upstaged on subsequent surgical resection when compared with the tumor stage initially reported on biopsy (13). Additionally, one study showed that approximately 5% of tumors were downstaged on the subsequent resections (14). In a large multi-institutional cohort study of 314 patients with UTUC, Margolin et al. showed that about 50% of patients had muscle-invasive UTUC during surgical resection, but fewer than half of these patients had evidence of tumor invasion on biopsy (15). In addition to the small sample size, superficial sampling is another common issue in discordant biopsies, as there is limited or no subepithelial stroma present for evaluation, which precludes the accurate invasion assessment. It has been proposed to use a larger biopsy device or a multi-biopsy approach to improve biopsy quality, and cytology should also be included to improve clinical grading (13). For pathologists, it is helpful to include a comment when the biopsy is superficial so that clinical team can know the evaluation of invasion in this biopsy is limited.

Histological subtypes of UTUC

The histopathology of UTUC is essentially identical to that of bladder urothelial carcinoma. The majority of UTUCs are histologically pure urothelial carcinoma, and approximately 25% of UTUCs show histological subtypes as well as divergent differentiation (squamous, glandular, and trophoblastic) (7). The histological subtypes include micropapillary, nested, large nested, microcystic, plasmacytoid, sarcomatoid, lipid-rich, lymphoepithelioma-like, clear cell (glycogen-rich), giant cell, and poorly differentiated (16) (Figure 3). In theory, any subtype of urothelial carcinoma in the urinary bladder may also be seen in the upper urinary tract. Some high-grade UTUC may transform to high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. Because of the rarity of UTUC, the clinical and research data of these histological subtypes in UTUC are relatively fewer than those of the urinary bladder. Rink et al. reported variant (or subtype) histology was present in 398 (24.2%) of 1648 UTUC cases, and squamous differentiation was the most common variant histology, followed by glandular, sarcomatoid, micropapillary, small cell, plasmacytoid, and others (17). Like similar tumor in the urinary bladder, several subtypes of UTUC, such as micropapillary, plasmacytoid, sarcomatoid, and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, show very aggressive behavior and poor outcome.

Figure 3.

UTUC with different histological subtypes and divergent differentiation. Here is an example of high grade UC of the renal pelvis (A, magnification ×5). This tumor has conventional high-grade UC mixed with sarcomatoid UC (B). Focal squamous (C) and glandular (D) features were also found in the same tumor. (B, C, D: magnification ×100)

It is of clinical significance to recognize and report the histological subtype of UTUC for accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. As mentioned earlier, histologic subtype is regarded as one of risk-stratifying factors for high-grade UTUC. It has been shown that some histologic subtypes can be associated with advanced stage and aggressive behavior (17, 18). In patients with adverse histologic subtypes of UTUC, tumor recurrence and cancer-specific mortality are generally worse than those with pure UC on univariate analysis, although there is no significant effect on multivariate analysis. When patients are treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, there are no significant differences in tumor recurrence and survival between histological subtypes and pure UC (7, 17, 19). Duplisea et al. identified 19 (4.6%) of 416 patients with micropapillary subtype of UTUC at MD Anderson Cancer Center over a 23-year period, and most of them had ≥pT3 disease at the time of extirpative surgery (20). In their case series, micropapillary subtype of UTUC did not appear to respond to perioperative chemotherapy, and most patients died of the disease within 2 years. Fatima et al. studied 15 cases of nested subtype of UTUC and demonstrated that, in comparison with the nested subtype in the urinary bladder, this subtype of UTUC is more frequently associated with overlying papillary urothelial carcinoma, more commonly has a large nested pattern, and appears to behave less aggressively (21).

Molecular classification of UTUC

A few studies have identified genetically distinct molecular subtypes of UTUC by examining DNA, RNA, and protein expression profiles. Moss et al. reported the first comprehensive, integrated genomic analysis of 31 UTUC samples and identified four expression subtypes with unique molecular profiles and clinical correlates (22). Cluster 1: no PIK3CA mutations, nonsmokers, high-grade <pT2 tumors, and high recurrence. Cluster 2: 100% FGFR3 mutations, low-grade tumors, tobacco use, noninvasive disease, and no bladder recurrence. Cluster 3: 100% FGFR3 mutations, 71% PIK3CA, no TP53 mutations, five bladder recurrences, tobacco use, tumors all <pT2. Cluster 4: KMT2D (62.5%), FGFR3 (50%), TP53 (50%) mutations, no PIK3CA mutations, high-grade pT2+ disease, tobacco use, carcinoma in situ, and shorter survival. In comparison with the bladder subtypes (23), cluster 1 shows similarity to the bladder luminal subtype, cluster 2 is similar to the basal subtype, and cluster 4 has a high rate of upregulated immune checkpoint genes.

More recently, Fujii et al. performed a larger scale genetic study of 199 UTUC specimens, and classified UTUC into five mutational subtypes, including TP53/MDM2-mutated, FGFR3-mutated, RAS-mutated, hypermutated, and triple-negative subtypes (24). In their study, these five subtypes showed discrete profiles of gene expression, tumor location/histology, and clinical outcome. The TP53/MDM2-mutated subtype is the largest (37.7%) UTUC subtype in their cohort with mutated TP53 or MDM2 amplification and showed the most aggressive phenotype with a high rate of metastasis (40%) and the shortest disease-specific survival. In addition, this molecular classification might provide a useful guidance for the choice of novel target therapeutic agents. For example, pan-FGFR inhibitors are promising therapeutic choices for patients with the hypermutated and FGFR3-mutated subtypes of UTUC. Although these molecular classification studies provided us important information to understand the molecular pathogenesis of UTUC, their clinical significance is still not well established, and therefore they have limited use in daily practice (3).

Subclassification of pT3 UTUC

Pathological tumor (pT) stage is one of the most important prognostic parameters to determine clinical outcome and guide clinical application of postsurgical adjuvant chemotherapy. However, the prognosis of pT3 UTUC, particularly renal pelvic UC, remains controversial with notable survival heterogeneity reported in the literature (19, 25–27). According to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual, pT3 UTUC includes renal pelvic UC with invasion into peripelvic fat or renal parenchyma, and ureteral UC with invasion into periureteric fat. Unlike the bladder and ureter, the muscular wall (muscularis) is not well developed in the renal pelvis and can be absent in some areas of major calyces (28) (Figure 4). Thus, most tumors in this location are assigned either pT1 or pT3 depending on the depth of invasion. In the minor calyces, the urothelium directly lies on the renal parenchyma without subepithelial tissue or muscularis, and any amount of invasive carcinoma that involves the renal parenchyma is staged as pT3 disease. The current AJCC manual does not comment on the extent of renal parenchyma invasion in the staging. If urothelial carcinoma involves the collecting ducts without definitive invasion of renal parenchyma, it is not staged as pT3 (28) but is rather considered to be pTis or pTa tumor showing retrograde involvement of the renal tubules and collecting ducts (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The muscular wall (muscularis) in the renal pelvis. (A) The muscularis is not well developed in the renal pelvis and can be thin or absent in some areas. (B) High-grade urothelial carcinoma involves the muscularis of renal pelvis and staged as pT2. (C) In minor renal calyx, the urothelium is immediately adjacent to the renal parenchyma without any subepithelial tissue or muscularis. (D) Any amount of invasive urothelial carcinoma in minor calyx is staged as pT3 disease. (A-D: magnification ×20)

Figure 5.

Urothelial carcinoma in situ involves the collecting ducts without definitive invasion of renal parenchyma (A, B), staged as pTis (not pT3). (C, D) High-grade urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis invades through muscularis into renal parenchyma, staged as pT3. (A: magnification ×20; C: magnification ×10; B &D: magnification ×100).

There are several proposals to subclassify pT3 UTUC, but they have not been adopted by the international classification system (25, 29, 30). Wong et al. compared patient survival of pT3 renal pelvic UC based on the extent of renal parenchyma invasion (31). Their study of 145 cases demonstrated that pT2 and pT3 tumors with only renal medulla invasion had similar overall survival, whereas pT3 tumors with peripelvic fat and/or renal cortex invasion had a worse prognosis. They recommended redefining renal pelvic UC with invasion into renal medulla only as pT2 (31, 32). Yamada et al. studied 323 patients with pT3 UTUC who underwent nephroureterectomy, and subclassified them into two groups: those with renal parenchymal invasion only (pT3a) and those with peripelvic or periureteral fat invasion (pT3b)(33). Their cohort showed that pT3b UTUC was associated with significantly worse survival rates than pT3a UTUC, and it was also associated with worse histological features such as hydronephrosis, nodal metastasis, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), carcinoma in situ, and positive surgical margin.

UTUC and Lynch syndrome

Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant familial cancer syndrome with an increased risk of a variety of cancers such as colorectal, gastrointestinal, urothelial, endometrial, ovarian, and skin cancers. It is caused by germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes or high-level microsatellite instability (MSI). Approximately 6–9% of patients with UTUC are associated with Lynch syndrome (34–36) in comparison with 1% of patients with bladder urothelial carcinoma. Recognition of these patients is clinically significant (37). The Amsterdam criteria (AMS) I and II are clinical criteria for identifying patients with potential Lynch syndrome based on personal and family histories of colorectal cancer (AMS I) or Lynch syndrome-related cancers (AMS II). Metcalfe et al. used AMS I/II and tissue-based tests to screen 115 patients with UTUC without a history of Lynch syndrome. Among them, 16 (13.9%) were positive for potential Lynch syndrome, and 6 (5.2%) were confirmed Lynch syndrome at the point of care (38). According to the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines (3), it is recommended to screen all patients aged < 60 years with UTUC and those with a family history of UTUC, or personal history of a Lynch-spectrum cancer, or those with a first-degree relative aged <50 years/two first-degree relatives with Lynch-spectrum cancer (39–42). There are two screening methods: immunohistochemistry (IHC) for MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) and MSI analysis (39, 43). IHC method has been widely utilized by pathologists as a cost-effective procedure. A positive screening result should prompt subsequent testing for germline DNA mutations. If the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome is confirmed, the patient should undergo clinical evaluation for other lynch-related cancers, as well as close monitoring and follow-up. Familial genetic counselling is also indicated.

Patients with Lynch syndrome have a 14–22 fold higher risk and a cumulative lifetime risk of 3–6% to develop UTUC than the general population (35, 38, 44, 45). Compared with sporadic UTUC, patients with Lynch syndrome-associated UTUCs have a female predominance, younger age at diagnosis, higher mutational burden, more likely bilateral, and more frequent in the ureter (34, 46). Several studies suggested that some histological features of UTUC were more commonly associated with Lynch syndrome, such as increased intratumoral lymphocytes, inverted growth pattern, pushing tumor-stromal interface, lack of nuclear pleomorphism, and low tumor stage(35, 36). However, no one morphological feature has been well defined as sensitive or specific enough to suggest Lynch syndrome. Genetic studies have shown different mutational profiles between sporadic and Lynch syndrome-associated UTUC. Sporadic UTUC has a significantly higher frequency with mutations in KMT2D, CREBBP, ARID1A or in DNA damage response/repair genes, whereas mutations in NOTCH1, NOTCH3, RB1, and CDKN1B were almost exclusively detected in Lynch syndrome-UTUC (34, 46).

Summary:

Significant progress has been made in recent years in the diagnosis, treatment, and molecular classification of UTUC. There are still many issues that require more clinical and basic research in the near future, such as improving the diagnostic accuracy of UTUC biopsy, identifying useful biomarkers for clinical and pathological practice, subclassification of pT3 UTUC, etc. Histology-based examination of UTUC remains the gold standard for the diagnosis and management of these patients. However, there is a trend toward a transition from histology to personalized molecular characterization in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of patients with UTUC. Further molecular studies of UTUC, including different histologic subtypes, may help us develop a practical molecular classification of UTUC to guide routine practice as well as to discover new prognostic factors and therapeutic targets. Finally, although current imaging technologies have greatly improved the sensitivity to detect UTUC, there are still some cases missed by imaging, particularly in early stage UTUC. On imaging study, UTUC may only present as wall thickening of the ureter or renal pelvis, not as mass lesion, which is challenging for radiologists to distinguish between neoplastic and inflammatory process. UTUC may be identified as an incidental finding in nephrectomy specimens for renal neoplasms or for non-neoplastic reasons (Figure 6). Pathologists should keep this in mind and routinely examine the urothelial lining in every nephrectomy specimen.

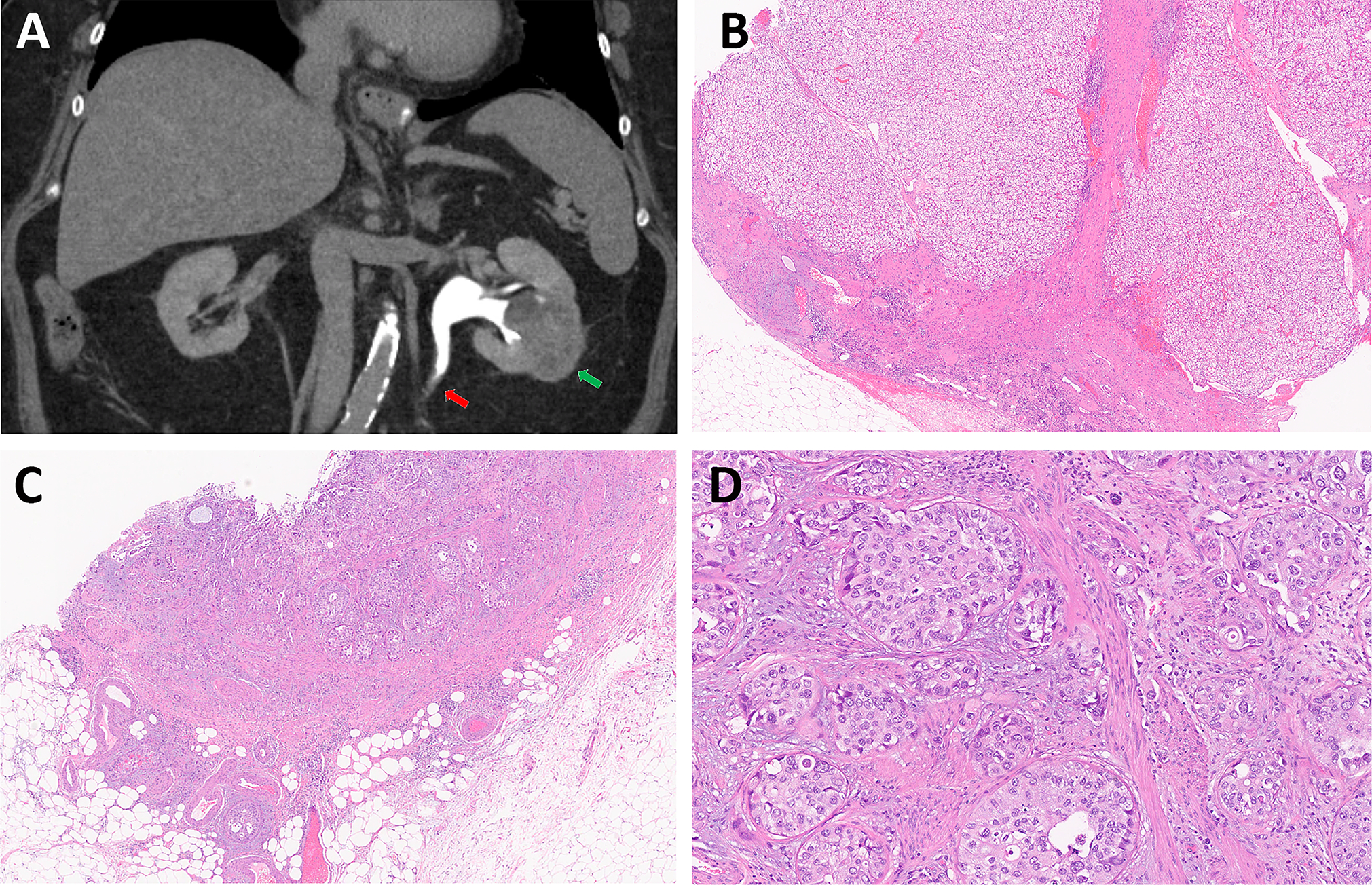

Figure 6.

High grade UTUC is incidentally identified in a radical nephrectomy specimen for renal cell carcinoma. (A) CT image demonstrates a 5.2 cm heterogeneous solid mass in the left kidney (Green arrow), and a subtle wall thickening (Red arrow) in the proximal left ureter with asymmetric ectasia of the upstream ureter and collecting system. (B) Renal mass shows clear cell renal cell carcinoma. (C, D) High grade urothelial carcinoma of the proximal ureter invades transmurally into periureteral fat. (B &C: magnification ×20; D: magnification ×100).

Funding:

The study was supported by the NIH/NCI under award number P30 CA016672.

Footnotes

Competing interest: All authors declare they have not conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soria F, Shariat SF, Lerner SP, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis, preoperative evaluation and prognostic assessment of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). World J Urol. 2017;35:379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roupret M, Seisen T, Birtle AJ, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: 2023 Update. Eur Urol. 2023;84:49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almas B, Halvorsen OJ, Johannesen TB, et al. Higher than expected and significantly increasing incidence of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. A population based study. World J Urol. 2021;39:3385–3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K, et al. Bladder Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2020;324:1980–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines: Bladder Cancer (Version 3.2023) for Upper GU Tract tumor (UTT-1/2/3). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimadamore A, Scarpelli M, Santoni M, et al. Upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma and its variants: transition from morphology to personalized molecular characterization in diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2018;18:1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheat JC, Weizer AZ, Wolf JS Jr, et al. Concomitant carcinoma in situ is a feature of aggressive disease in patients with organ confined urothelial carcinoma following radical nephroureterectomy. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zigeuner R, Shariat SF, Margulis V, et al. Tumour necrosis is an indicator of aggressive biology in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Eur Urol. 2010;57:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AK, Stephenson AJ, Lane BR, et al. Inadequacy of biopsy for diagnosis of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: implications for conservative management. Urology. 2011;78:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavora F, Fajardo DA, Lee TK, et al. Small endoscopic biopsies of the ureter and renal pelvis: pathologic pitfalls. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1540–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vashistha V, Shabsigh A, Zynger DL. Utility and diagnostic accuracy of ureteroscopic biopsy in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon CT, Skala SL, Weizer AZ, et al. Clinical utility and concordance of upper urinary tract cytology and biopsy in predicting clinicopathological features of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2019;86:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chitale S, Mbakada R, Irving S, et al. Nephroureterectomy for transitional cell carcinoma - the value of pre-operative histology. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolin EJ, Matulay JT, Li G, et al. Discordance between Ureteroscopic Biopsy and Final Pathology for Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. J Urol. 2018;199:1440–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Classification of Tumours: Urinary and Male Genital Tumours (5 th Ed). 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rink M, Robinson BD, Green DA, et al. Impact of histological variants on clinical outcomes of patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2012;188:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolim I, Henriques V, Rolim N, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of upper urinary tract carcinoma with variant histology. Virchows Arch. 2020;477:111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raman JD, Ng CK, Scherr DS, et al. Impact of tumor location on prognosis for patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma managed by radical nephroureterectomy. Eur Urol. 2010;57:1072–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duplisea JJ, Petros FG, Li R, et al. Outcomes of nonmetastatic micropapillary variant upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2019;37:354 e319–354 e326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fatima A, Russell DH, Epstein JI. Nested Subtype of Urothelial Carcinoma in the Upper Urinary Tract: A Series of 15 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2023;47:461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss TJ, Qi Y, Xi L, et al. Comprehensive Genomic Characterization of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2017;72:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507:315–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujii Y, Sato Y, Suzuki H, et al. Molecular classification and diagnostics of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:793–809 e798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sassa N, Tsuzuki T, Fukatsu A, et al. Is pT3 urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis a homogeneous disease entity? Proposal for a new subcategory of the pT3 classification. Histopathology. 2012;61:620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu CF, Pang ST, Chen CS, et al. The impact factors on prognosis of patients with pT3 upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;178:446–450, dicussion 450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isbarn H, Jeldres C, Shariat SF, et al. Location of the primary tumor is not an independent predictor of cancer specific mortality in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2009;182:2177–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eble JA P; Cheng L; Grignon DJ. Tumors of the Kidney, Bladder, and Related Urinary Structures (AFIP Atlases, Series 5). 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shariat SF, Zigeuner R, Rink M, et al. Subclassification of pT3 urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvicalyceal system is associated with recurrence-free and cancer-specific survival: proposal for a revision of the current TNM classification. Eur Urol. 2012;62:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J, Habuchi T, Arai Y, et al. Reassessment of prognostic heterogeneity of pT3 renal pelvic urothelial carcinoma: analysis in terms of proposed pT3 subclassification systems. J Urol. 2014;192:1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong MN, Wu DJ, Lee CT, et al. Renal Pelvic Urothelial Carcinoma With Invasion Into Renal Medulla Can Be Redefined as pT2 to Improve Correlation With Survival. Mod Pathol. 2023;36:100140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu D, Lee CT, Zynger DL. Reclassifying pT3 renal pelvic urothelial carcinoma with renal parenchyma invasion to pT2 improves correlation with overall survival. Hum Pathol. 2022;125:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada Y, Nakagawa T, Miyakawa J, et al. Subclassification of pT3 upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective study. World J Urol. 2023;41:767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donahu TF, Bagrodia A, Audenet F, et al. Genomic Characterization of Upper-Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in Patients With Lynch Syndrome. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindner AK, Schachtner G, Tulchiner G, et al. Lynch Syndrome: Its Impact on Urothelial Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harper HL, McKenney JK, Heald B, et al. Upper tract urothelial carcinomas: frequency of association with mismatch repair protein loss and lynch syndrome. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pradere B, Lotan Y, Roupret M. Lynch syndrome in upper tract urothelial carcinoma: significance, screening, and surveillance. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metcalfe MJ, Petros FG, Rao P, et al. Universal Point of Care Testing for Lynch Syndrome in Patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. J Urol. 2018;199:60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gayhart MG, Johnson N, Paul A, et al. Universal Mismatch Repair Protein Screening in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grobet-Jeandin E, Pinar U, Roupret M. Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in Lynch Syndrome Patients: The Urologist Still Has a Role in Genetic Screening. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5:42–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ju JY, Mills AM, Mahadevan MS, et al. Universal Lynch Syndrome Screening Should be Performed in All Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1549–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lonati C, Moschini M, Simeone C, et al. Lynch syndrome in urological practice: diagnosis, therapeutic strategies, and screening for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Curr Opin Urol. 2022;32:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rasmussen M, Madsen MG, Therkildsen C. Immunohistochemical Screening of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinomas for Lynch Syndrome Diagnostics: A Systematic Review. Urology. 2022;165:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson P, Vasen HFA, Mecklin JP, et al. The risk of extra-colonic, extra-endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:444–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crockett DG, Wagner DG, Holmang S, et al. Upper urinary tract carcinoma in Lynch syndrome cases. J Urol. 2011;185:1627–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comperat E, Oszwald A, Wasinger G, et al. Molecular uropathology and cancer genetics for the urologist: key findings for classification and diagnosis. Curr Opin Urol. 2022;32:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]