Abstract

Camptothesome is a sphingomyelin-conjugated camptothecin (SM-CSS-CPT) nanovesicle that fortified the therapeutic delivery of CPT in diverse cancer types. To mitigate the Camptothesome-induced IDO1 negative feedback mechanism, we had co-encapsulated, indoximod (IND, IDO1 inhibitor) into Camptothesome using doxorubicin-derived IND (DOX-IND). To maximize the therapeutic potential of DOX-IND/Camptothesome, herein, we first dissected the synergistic drug ratio (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT) via systematical in vitro screening. DOX-IND/Camptothesome with optimal drug ratio synchronized in vivo drug delivery with significantly higher tumor uptake compared to free drugs. This optimum DOX-IND/Camptothesome outperformed the combination of Camptothesome, Doxil and IND or other IDO1 inhibitors (BMS-986205 or epacadostat) in treating mice bearing late-stage MC38 tumors, and combination with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) enabled it to eradicate 60% of large tumors. Further, this optimized co-delivery Camptothesome beat Folfox and Folfiri, two first-line combination chemotherapies for colorectal cancer in antitumor efficacy and exhibited no side effects as compared to the severe systemic toxicities associated with Folfox and Folfiri. Finally, we demonstrated that the synergistic DOX-IND/Camptothesome was superior to the combined use of Onivyde + Doxil + IND in curbing the advanced orthotopic CT26-Luc tumors and eliminated 40% tumors with complete metastasis remission when cooperated with ICB, eliciting stronger anti-CRC immune responses and greater reversal of immunosuppression. These results corroborated that with precise optimal synergistic drug ratio, the therapeutic potential of DOX-IND/Camptothesome can be fully unleased, which warrants further clinical investigation to benefit the cancer patients.

Keywords: Camptothesome; Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Indoximod; Colorectal cancer; Immunochemotherapy

Introduction

Camptothesome is a sphingolipid-derived camptothecin (CPT) liposomal nanovesicle in which CPT was covalently conjugated to the hydroxyl group on the sphingomyelin (SM)[1]. This SM-CSS-CPT conjugate blocked the conversion of active lactone to the inactive carboxylate form in CPT, improving its chemical stability[1, 2]. Compared to the physical loading of CPT into the lipid bilayer of various types of conventional liposomes, Camptothesome drastically increased drug loading capacity and efficiency with improved formulation stability[1]. Camptothesome also minimized the systemic toxicities associated with free CPT with markedly higher maximum tolerated (MTD) dose[1]. Via systematic structure activity relationship study, SM-CSS-CPT nanovesicle with a disulfide bond and longer linker performed better than other conjugates (ester, glycine, and disulfide bond) and free CPT on pharmacokinetics and tumor delivery efficiency and boasted deep tumor penetration ability and best anticancer efficacy in colorectal tumor model.

While immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy has been regarded as the paradigm-shifting cancer immunotherapy, it only works for a select patient population[3, 4]. For colorectal cancer (CRC), patients with mismatch repair deficiency or microsatellite instability-high tumors are responsive to ICB, but who only account for ~4% of the total CRC population[5, 6]. We demonstrated that Camptothesome can turn the “cold” CRC tumors into “hot” environment by upregulating the tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) through eliciting the immunogenic cell death in an IFN-γ-dependent manner, which synergized with the PD-1/PD-L1 ICB therapy to eradicate a significant portion of established MC38 CRC tumors[1, 7]. While Camptothesome-induced IFN-γ favorably modulated the T cell immunity, it also involuntarily heightened the level of another independent immune checkpoint, the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1)[1]. IDO1 can suppress CTLs activity while activating the regulatory T cells (Treg) via degrading an essential amino acid, tryptophan[8]. To abrogate the IDO1-triggered negative immune feedback loop, we intended to co-deliver an IDO1 inhibitor, indoximod (IND) with Camptothesome. However, direct IND loading met with limited success[1]. To address this bottleneck, we creatively engineered a doxorubicin (DOX)-derived IND (DOX-IND) conjugate, which can be efficiently and remotely loaded into the core of the Camptothesome and formed stable drug precipitates, using the lipid bilayer-crossing ability of DOX[1, 9]. This design imparted the nanotherapeutic with an additional ICD inducer, DOX, and enabled DOX-IND-laden Camptothesome to further enhance the anti-CRC activity and immunity.

In this work, to unleash the full therapeutic potential of DOX-IND/Campothesome, we systematically screened DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT combination at various ratios and pinpointed the best synergistic drug ratio. This optimal drug ratio was implemented into the Camptothesome, which underwent comprehensive physicochemical characterization. We identified the maximum tolerated dose for this optimal co-delivery nanosystem that synchronized the drug delivery of different payloads to tumors with significantly improved blood circulation time and tumor accumulation compared to free drugs. To figure out if the coordinated drug delivery would offer advantages over the separate drugs, we compared the efficacy of optimum DOX-IND/Camptothesome with the co-administration of “Camptothesome + IND + Doxil (FDA-approved liposomal DOX)”. To elucidate the superiority of our co-delivery nanotherapeutic to other frequently used IDO1 inhibitors drug combination, in addition to the IND, the optimized DOX-IND/Camptothesome was also compared with BMS-986205 or epacadostat along with Camptothesome and Doxil. Surprisingly, our optimal combined nanomedicine beat these additional IDO1 inhibitors combination regimen, particularly when ICB was co-used.

FOLFOX and FOLFIRI are two standard of care combinations of chemotherapy drugs for treating advanced colorectal cancer clinically. FOLFOX comprises folinic acid (leucovorin, FOL), fluorouracil (5-FU, F), and oxaliplatin (OX)[10], and FOLFIRI consists of FOL, 5-FU, and irinotecan[11]. While both FOLFOX and FOLFIRI showed promising clinical outcome in CRC patients, the co-administration of different chemo-drugs yielded more adverse side effects, greatly limiting their clinical applications. We posit that our synergistic DOX-IND/Camptothesome would show better therapeutic activities than FOLFOX and FOLFIRI against CRC tumors with less adverse effects via an improved drug co-delivery approach. Furthermore, we also evaluate the merit of our combined nanodelivery approach over the co-use of Onivyde + Doxil + IND because Onivyde is only FDA-approved nanodrug from the CPT-based drug category. Strikingly, DOX-IND/Camptothesome also beat this combination therapy and completely curbed the late-stage orthotopic CT26-Luc tumor and drastically reduced the metastasis to healthy organs. These effects were more notable when ICB was also applied. More importantly, our nano-enabled co-delivery strategy elicited stronger CTL anti-CRC immunity via instigating greater immunogenic cell death and Treg suppression. Taken together, our optimized Camptothesome carrying precise and synergistic drug ratio represents a powerful combination regimen for improved intervention of advanced late-stage CRC tumors.

Methods

Cells and mice

The CT26 and CT26-Luc cell lines were purchased from UArizona Cancer Center and cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium. MC38 cell line was purchased from Kerafast and cultured in complete DMEM medium. Normal cell lines 293T and BEAS-2B were purchased from ATCC and cultured in complete DMEM medium. The cells were cultured in the corresponding medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37 °C with a CO2 incubator. C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice (Charles Rivers, ~6 weeks old, female) were used. Tumor size was mersured by a digital caliper at indicated times and calculated using the formula = 0.5 × length × width2. Mice were euthanized and removed from the respective study when individual tumor reached ~2000 mm3 in size or animals became moribund with severe weight loss, extreme weakness, or inactivity. The animals were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and all animal experiments were approved by the UArizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

DOX-IND/Camptothesome and Camptothesome preparation

The synthesis of SM-CSS-CPT and DOX-IND were according to our previous methods[1]. The preparation of DOX-IND/Camptothesome followed the standard thin-film hydration approach. Briefly, SM, SM-CSS-CPT, Cholesterol and DSPE-PEG2K in the indicated molar ratio of Supplementary Fig. 1a were dissolved in ethanol in a round-bottom glass flask, the solvent was evaporated under ultra-high vacuum (MaximaDry, Fisherbrand) with a rotatory evaporator (RV 10 digital, IKA®) to generate a thin film. An aqueous solution of 80 mM (NH4)2SO4 was added into the round-bottom glass flask to hydrate the film at 50 °C for 30 min. The solution was transferred to a tube and sonicated under a 3/2 s on/off pulse at a power output of 60 W (VCX130, Sonics & Materials Inc) for 12 min. The unencapsulated (NH4)2SO4 was removed by running through a PD-10 column (Sephadex G-25, GE Healthcare) using PBS as the eluent. To remotely encapsulate of DOX-IND into the Camptothesome, 1–10 mg/mL of DOX-IND was incubated with (NH4)2SO4 buffer-laden Camptothesome at 65 °C for 1 h. Afterwards, the solution was left at 4 °C for 30 min, and the unencapsulated DOX-IND was removed by running through a PD-10 column (Sephadex G-25, GE Healthcare) using PBS buffer as eluent. The preparation of Camptothesome was according to the ratio listed above, SM, SM-CSS-CPT, Cholesterol and DSPE-PEG2K in the molar ratio of 79.85/4.98/11.28/3.89 were dissolved in ethanol in a round-bottom glass flask, the solvent was evaporated under ultra-high vacuum (MaximaDry, Fisherbrand) with a rotatory evaporator (RV 10 digital, IKA®) to generate a thin film. An aqueous solution of 5% dextrose was added into the round-bottom glass flask to hydrate the film at 50 °C for 30 min. The solution was transferred to a tube and sonicated under a 3/2 s on/off pulse at a power output of 60 W (VCX130, Sonics & Materials Inc) for 12 min. The size, zeta potential and PDI, morphology, and drug content of the DOX-IND/Camptothesome were determined by DLS, Cryo-EM and HPLC, respectively. The DOX-IND, CPT or IND drug loading capacity [DLC, equation (1)] and drug loading efficiency [DLE, equation (2)] were calculated using the formulas shown below:

Combination index (CI) study

The drug combination study of SM-CSS-CPT with DOX-IND or DOX-IND/camptothesome in MC38 and CT26 cells or in normal cells 293T and BEAS-2B were performed according to the previous method[12]. Briefly, 12 h after the cells seeded in 96-well plates at the density of 2000 cells/well, the combination molar ratio of 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 8:1, 16:1, 20:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, 1:20 and the drugs alone (drug concentration: 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.312, 0.156, 0.078 and 0.039 μM, in normal cells 293T and BEAS-2B, drug concentration: 400, 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.78 and 0.39 μM) were added into the wells and incubated for 48 h, respectively. The IC50 values of each compound were calculated by the cell viabilities that were measured by MTT. The combination index (CI) plot depicts the IC50 values of each compound at different combination ratios by using the following equation:

CI < 1 indicates the synergy, CI = 1 indicates the additive effect, CI > 1 indicates the antagonism.

Release kinetics of DOX-IND/Camptothesome

PBS (pH = 7.4, pH = 6.5, pH = 5.5, pH = 5 or GSH = 10 mM) containing 0.5% (w/v) Tween 80 was used as the release medium for the drug release kinetics study of DOX-IND/Camptothesome in vitro. Briefly, two mL of DOX-IND/Camptothesome were transferred into dialysis tubes (MWCO = 12 kDa, Spectrum Laboratories), and then suspended in 200 mL release medium inside a beaker shielded with aluminum foil. The temperature of the release medium was kept at 37 °C and stirred at 100 rpm. Before incubation (0 h) and at indicated time points, 5 and 100 μL of solution were taken from the dialysis tubes and dialysate, respectively. The concentration of DOX-IND remaining in the dialysis tubes and dialysate were measured by HPLC.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC experiments were investigated by MicroCal VP-capillary DSC (Malvern Panalytical). Data were obtained over a range of 10–90 °C at 60 °C/h with DI water as the reference. For DSC testing, DOX-IND/Camptothesome was prepared as described above, the samples were diluted to 2 mg lipid/mL with DI water. Afterwards, samples were cooled to room temperature, degassed, and 400 μL of each sample were used for the DSC study. The software (run by VPViewer 2000; analyzed by Microcal, LLC Cap DSC Version: Origin70-L3) package from Microcal was used to convert the raw data into molar heat capacity (MHC). Data were then imported into Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software) for further processing and calculation.

Leakage profile of DOX-IND/Camptothesome

DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 4.30/3.02 mg/mL) was prepared as described above and kept under 4 °C. After indicated time, 1 mL of DOX-IND/Camptothesome was extracted from the stock solution and the leaked drug was removed by running through a PD-10 column (Sephadex G-25, GE Healthcare) using PBS buffer as eluent. Sample was then digested by Methanol and the DOX-IND fluorescence intensity was detected on a SpectraMax M3 reader (SoftMax Pro (v. 7.1.0), Molecular Devices) with an excitation wavelength of 470 nm and emission wavelengths of 590 nm. The fraction of drug left in DOX-IND/Camptothesome was calculated as following:

Maximum tolerated dose (MTD)

Balb/c mice (3 mice/group) were administered intravenously with DOX-IND/Camptothesome (5.4/3.8, 10.8/7.5, 16.2/11.3, 21.5/15.1 and 26.6/18.9 DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT mg/kg). Changes in body weight and survival of mice were monitored for two weeks. The MTD was defined as the maximal dose that causes neither mouse death due to the toxicity nor greater than 15% of body weight loss or other remarkable changes in the general appearance within the entire period of the experiments.

Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution

Free CPT (4 mg/kg), SM-CSS-CPT (15.1 mg/kg), free DOX (12.5 mg/kg), free DOX-IND (21.5 mg/kg), Doxil (12.5 mg DOX/kg), free IND (5.0 mg/kg) or DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg) were intravenously injected into orthotopic CT26 tumor bearing mice (n = 3, tumor size: ~400 mg) via tail vein, respectively. At 0.083, 0.333, 1, 2.5, 8, 12 and 24 h after drug administration, blood was withdrawn; and plasma was collected by using a plasma tube (BD Microtainer) and then digested in methanol prior to HPLC measurement for the CPT, DOX, IND, DOX-IND and SM-CSS-CPT, respectively[1]. To visualize DOX-IND/Camptothesome tumor delivery, tumor tissues and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidneys) were dissected and imaged using a Lago optical imager (CPT, excitation at 360 nm, emission at 490 nm; DOX, excitation at 500 nm, emission at 590 nm, Aura 64 bit analysis software (v. 3.2.0)) at 24 h after drug administration. The tissues were homogenized in acidified methanol (0.075 M HCl, 900 μL/100 mg tissue) before HPLC drug content analysis, respectively. The pharmacokinetic parameters of free CPT, SM-CSS-CPT, DOX-IND, Doxil, free DOX, free IND, DOX-IND/Camptothesome were assessed by using PKSolver software (version 2.0)[13].

Therapeutic efficacy study in subcutaneous MC38 tumor model

A total of 1 × 105 MC38 cells in 100 μL of serum free medium were subcutaneously inoculated into the C57BL/6 mice (n = 5). In Fig. 3, when tumors reached to ~300 mm3 in size on day 16, mice were intravenously injected with a single dose of 5% Dextrose (vehicle control), DOX-IND (21.5 mg/kg), Camptothesome (SM-CSS-CPT, 15.1 mg/kg), DOX-IND (21.5 mg/kg) plus Camptothesome (SM-CSS-CPT, 15.1 mg/kg), DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg) Doxil (MTD dose of 25 mg DOX/kg) or Camptothesome (15.1 mg SM-CSS-CPT/kg) plus Doxil (12.5 mg DOX/kg) and free IND (5.0 mg/kg) or their combination with α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1. α-PD-L1 (BioXCell, clone 10F.9G2) and α-PD-1 (BioXCell, clone RMP1–14) were intraperitonerally administered at 100 μg/mouse/3 days for 3 times[14, 15]. Tumor growth, mouse body weight and survival were closely monitored as indicated. In Fig. 3g–i, the blood was collected in lithium heparin tubes (BD Microtainer™) and the primary tumors were dissected on day 22. The tumors and plasma were used to measure the concentration of Trp and Kyn by ELISA. The dissected tumor from each mouse was homogenized in 4 °C PBS (900 μL/100 mg tissue), respectively. After centrifugation at 2,000 g under 4 °C for 5 minutes, the supernatant was collected and used to measure the Trp and Kyn concentration by a kynurenine/tryptophan ratio ELISA pack (ImmuSmol, ISE-2227) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For the plasma, it was directly measured by the ELISA pack according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Fig. 3. DOX-IND/Camptothesome is superior to the combination of Camptothesome, IND, and Doxil in large subcutaneous MC38 tumor mouse model.

a-c, therapeutic efficacy of DOX-IND/Camptothesome in comparison to the combination of Camptothesome + IND + Doxil in MC38 tumor model (tumors: ~300 mm3, n = 5). On day 16 post tumor cells inoculation, mice were intravenously injected once at 21.5/15.1 (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT) mg/kg, Doxil 12.5 DOX mg/kg, 5 mg IND/kg. a, tumor growth curves. b, Kaplan-Meier survival curves. c, the mice tumor images taken on day 22. d-f, combination with PD-L1/PD-1 ICB in treating large MC38 tumor model (tumors ~300 mm3, n = 5). ICB was intrapearinatally injected at 100 μg per mouse per 3 days for a total of 3 times. d, tumor growth curves. e, Kaplan-Meier survival curves. f, the mice tumor images taken on day 22. Red circle: tumor-free mouse. g-j, therapeutic efficacy in large MC38 tumor model (~300 mm3, n = 5). The MTD dose of Doxil (25 mg/kg) was adopted according to previous report[29]. g, tumor growth curves. The ratio of Trp (nM)/kyn (nM) in plasma (h) and tumors (i) on day 22. j, the mice tumor images taken on day 22. Red circle: tumor-free mouse. Data in a,d,g-i are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; survival curves were compared using the log-rank Mantel–Cox test.

In Fig. 4a–c, when tumors reached to ~200 mm3 in size on day 14, mice were intravenously injected with a single dose of 5% Dextrose (vehicle control), DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg) or Camptothesome (15.1 mg SM-CSS-CPT/kg) plus Doxil (12.5 mg DOX/kg) or free IND (5.0 mg/kg, p.o. daily), free BMS-986205 (5.0 mg/kg, p.o. daily) or free EPA (5.0 mg/kg, p.o. daily). In Fig. 4d–f, when tumors reached ~400 mm3 in size on day 15, mice intravenously received the same dose as above and their combination with α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1 or α-PD-L1 + α-CTLA-1. α-PD-L1 (BioXCell, clone 10F.9G2), α-PD-1 (BioXCell, clone RMP1–14) or α-CTLA-4 (BioXCell, clone 9H10) were intraperitoneally administered at 100 μg/mouse/3 days for 3 times[14–16]. Tumor growth, mouse body weight and survival were closely monitored as indicated.

Fig. 4. DOX-IND/Camptothesome outperforms the combination of Camptothesome and Doxil with other IDO1 inhibitors in large subcutaneous MC38 tumor model.

a-c, anticancer activity of co-delivery Camptothesome in comparison to the co-injection of Camptothesome + Doxil + other IDO1 inhibitors (BMS-986205 (BMS), epacadostat (EPA)) in large MC38 tumor model (tumors: 200 mm3, n = 5). Mice received a single intravenous injection of 21.5/15.1 mg DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT/kg, Doxil 12.5 DOX mg/kg. Free IDO1 inhibitors were daily oral administration at 5 mg IND/kg, 5 mg BMS/kg, 5 mg EPA/kg from day 14 post cancer cells inoculation. a, tumor growth curves. b, Kaplan-Meier survival curves. c, the mice tumor images taken on day 20. d-f, combination with various ICB in treating large MC38 tumor model (tumors: 400 mm3, n = 5), drug dose were given as same a-c, ICB was intraperitoneally injected at 100 μg per mouse per 3 days for a total of 3 times. d, tumor growth curves. e, Kaplan-Meier survival curve. f, the mice tumor images taken on day 20. Red circle: tumor-free mouse. Data in a,d are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; survival curves were compared using the log-rank Mantel–Cox test.

In Fig. 5a–c, when tumors reached to ~400 mm3 in size on day 15, mice were intravenously received single dose of 5% Dextrose (vehicle control), DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg), FOLFOX [5-Fu (100 mg/kg), oxaliplatin (2.5 mg/kg), and leucovorin (90 mg/kg)] or FOLFIRI [5-FU (100 mg/kg), irinotecan (24 mg/kg), and leucovorin (90 mg/kg)] or their combination with α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1. α-PD-L1 (BioXCell, clone 10F.9G2) and α-PD-1 (BioXCell, clone RMP1–14) were intraperitoneally administered at 100 μg/mouse/3 days for 3 times[14, 15]. Tumor growth, mouse body weight and survival were closely monitored as indicated. In an independent study, healthy C57BL/6 mice (n = 3) received the same treatment as above, on day 20, blood was withdrawn by cardiac puncture. Blood was collected in lithium heparin tubes (BD Microtainer™) followed by centrifuging at 2,000 g for 10 minutes in a refrigerated centrifuge. The supernatant (serum) was sent to University Animal Care Pathology Services Core at UArizona for serum chemistry analysis (Liasys 330). The whole blood in dipotassium EDTA tube (BD Microtainer™) were used for leukocytes, erythrocytes, and thrombocytes analysis (Hemavet 950FS).

Fig. 5. DOX-IND/Camptothesome performed better than FOLFOX and FOLFIRI, two standard of care combination chemotherapies for CRC with diminished adverse effects.

a-c, anti-CRC activity compared to FOLFOX and FOLFIRI in a late-stage subcutaneous MC38 tumor mouse model (tumors: ~400 mm3, n = 5). In FOLFOX: 5-FU (100 mg/kg), oxaliplatin (2.5 mg/kg), and leucovorin (90 mg/kg); and in FOLFIRI: 5-FU (100 mg/kg), irinotecan (24 mg/kg), and leucovorin (90 mg/kg) were intravenously injected to mice, these doses were inferred from the reported literatures[30–33]. DOX-IND/Camptothsome was injected at 21.5 mg/kg for DOX-IND, and 15.1 mg/kg for SM-CSS-CPT. ICB was used as Fig. 3. a, Monitoring of the tumor development. b, Kaplan-Meier survival curves. c, mice tumor images on day 20. Red circle: tumor-free mouse. d-g, the serum chemistry, and hematological cell studies on day 20 from an independent study after healthy C57BL/6 mice received the same treatment as Fig. 5a. Data in a,d-g are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; survival curves were compared using the log-rank Mantel–Cox test.

Therapeutic efficacy study in orthotopic CT26-Luc tumor model

The orthotopic CT26-Luc tumor model in Balb/c mice was established according to our previous method[1]. Nine days after CT26-Luc cells inoculation (primary tumor weight: ~400 mg), orthotopic CT26-Luc tumor-bearing Balb/c mice were randomly allocated into 6 groups (n = 5). Mice were intravenously injected with a single dose of 5% Dextrose (vehicle control), DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg) or Onivyde (6.7 mg irinotecan/kg, at equivalent 4 mg CPT/kg) plus Doxil (12.5 mg DOX/kg) and IND (5.0 mg/kg) or their combination with α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1. α-PD-L1 (BioXCell, clone 10F.9G2) and α-PD-1 (BioXCell, clone RMP1–14) were intraperitonerally administered at 100 μg/mouse/3 days for 3 times[14, 15]. Tumor burden of a whole mouse body was determined by bioluminescence radiance intensity using Lago optical imaging after mice were intraperitoneally injected with 150 mg/kg D-Luciferin (GoldBio, MO, USA). The whole-body tumor burden was monitored by Lago optical imager on day 9, 12, 16 and 19 and quantified as bioluminescence radiance intensity (p/sec/cm2/sr) using Aura 3.2.0 imaging software. On day 19, following injection of D-Luciferin, mice were dissected, and gastrointestinal tract and other major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidneys, stomach, small and large intestines, caecum and rectum) were quickly obtained and then subject to photographing and ex vivo Lago imaging to investigate the tumor metastasis. The primary tumor blocks were divided into two parts, one part was for IHC study. Three tumor parts were randomly chosen from each group and subjected to flow cytometry analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis

The collected tumors were divided into small pieces by scissors on ice, and then digested in DMEM medium (0.5 mg/mL collagenase type I, Worthington Biochemical Corporation) for 1 h at 37 °C. The samples were meshed through a 70 μM cell strainer twice to obtain single cells for analysis. To lyse the red blood cells, the cell solution was incubated with Ack lysing buffer (Gibco, 2217610) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The cell solution was washed with 4 °C PBS twice and resuspended in 4 °C staining buffer followed by counting and aliquoting. To avoid nonspecific binding, the cell suspensions were pre-incubated with FcBlock (TruStain fcXTM anti-mouse CD16/32, clone 93, 101320, BioLegend, 0.5 μg/100 μL) at 4 °C for 20 min. Cells were stained with fluorescence-labelled antibodies at 4 °C for 30 min[17]. CD45-APC-Cy™7 (30-F11, #557659, 1/100), CD8a-PE (53–6.7, #561095, 1/100), CD11c-PerCP-Cy5.5 (HL3, #560584, 1/100), CD80-APC (16–10A1, #553766, 1/100), CD86-PE (GL1, #553692,1/100), CD3-APC-eFluor 780 (17A2, #47-0032-82, 1/100) and CD25-APC (PC61.5, #17-0251-82, 1/100) were purchased from BD Biosceinces. Foxp3-PE (MF23, #563101, 1/100) and Granzyme B-eFluor 660 (NGZB, #50-8898-82, 1/100) were purchased from eBiosciences. Zombie Violet™ Fixable Viability Kit (#423114), CD4-Alexa Fluor 488 (RM4–5, #100529, 1/100) and IFN-γ-APC (XMG1.2, #505810, 1/100) were purchased from BioLegend. Multi-parameter staining was used to measure the T cells: (i) IFN-γ+ T cells (CD3+/CD8+/IFN-γ+), (ii) granzyme B+ T cells (CD3+/CD8+/granzyme B+), (iii) CD25+ T cells (CD3+/CD8+/CD25+), (iv) Tregs (CD3+/CD4+/Foxp3+), DCs cells: (i) CD80+/CD86+ DCs (CD45+/CD11c+/CD80+/CD86+), (ii) CD11c+/CD103+ DCs (CD45+/CD11c+/CD103+). For IFN-γ staining, cells were first stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail (eBioscience, #00-4975-93) for 4 h prior to extracellular and intracellular staining according to the manufacture’s protocol. Cells were fixed and permeabilized using a staining Buffer Set (eBioscience, #00-5523-00) followed by intracellular staining of IFN-γ, granzyme B or Foxp3. After washing, cells were measured on flow cytometry and analyzed by FlowJo software (version 10.0.7, TreeStar). The numbers presented in the flow cytometry analysis images were percentage based.

Statistical analysis

The level of significance in all statistical analyses was set at P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. and were analysed using the two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test for two groups or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for three or more groups followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared with the log-rank Mantel–Cox test.

Results

Constructing synergistic co-delivery DOX-IND/Camptothesome

To determine the optimal drug ratio for DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, we performed the systematic anticancer activity in two CRC cell lines (MC38 and CT26) using different drug combination ratios at various concentrations (Fig. 1a–f). After 48 h treatment, MTT assay was used to assess the cell viability. The combination index (CI) is a commonly used indicator to determine the drugs’ synergistic (CI<1), additive (CI=1), and antagonistic (CI>1) effects[12]. Upon analyzing the CI for various molar ratios of DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT or SM-CSS-CPT/DOX-IND, we revealed that 2/1 molar ratio for DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT imparted the lowest CI, signaling the strongest synergy at this drug ratio (Fig. 1c,f). To confirm if this is the best drug ratio when co-loaded into Camptothesome, we have developed DOX-IND/Camptothesome with different drug molar ratios of DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT and examined the synergy in MC38 and CT26 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our results demonstrated that 2/1 molar ratio of DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT in DOX-IND/Camptothesome imparted the lowest combination index (CI), which indicated optimal drug ratio and was consistent with the cytotoxicity study by combination of DOX-IND and SM-CSS-CPT in Fig. 1a–f. We also used normal cell lines 293T and BEAS-2B to study the cytotoxicity of DOX-IND/Camptothesome (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, our results elucidated that DOX-IND/Camptothesome possess combination index (CI) > 1 and didn’t exhibit synergistic cytotoxic effect under the tested drug ratios. In contrast, we also observed that in tumor cell lines (Fig. 1a–f), the IC50 values for DOX-IND/Camptothesome were ~ 50–200-fold higher in normal cell lines than in tumor cell lines (Fig. 1a–f), which suggested significant lower cytotoxicity towards normal cells. This could be due to the higher concentration of GSH in the tumor cells[18], which triggered efficient drug release from DOX-IND/Camptothesome through attacking the disulfide linkers (Fig. 1n). Thus, these findings demonstrated that the negligible side effects in vivo could be attributed to selective cytotoxicity against tumor cells. Afterwards, this ratio was integrated into Camptothesome following the previously established nanoformulation synthesis and preparation process based on thin-film hydration and remote loading methods[1]. This optimal co-delivery nanovesicle was around ~99 nm, which is consistent with our prior report[1], and boasted good formulation stability as there was no marked size and zeta potential change over 2 weeks, as well as sustained the spheric bilayer structure with column-like drug precipitates inside that can prevent the drugs from diffusing back out of the membrane, avoiding untoward drug leakage (Fig. 1h–k). DOX-IND/Camptothesome presented phase transition temperature of ~38.8 °C (Fig. 1l) and maintained more than 95% drug retention inside Camptothesome for up to 2 weeks at 4 °C (Fig. 1m). Via drug release kinetics study, we confirmed that DOX-IND/Camptothesome had very limited drug release at physiological pH, which was accelerated in the presence of GSH or acidic pH (Fig. 1n)[1], suggesting its excellent stability during blood circulation and can readily liberate drugs from Camptothesome once inside tumors as which have high GSH and lower pH levels[18–20].

Fig. 1. Determination of synergistic drug molar ratio and development of the optimal co-delivery DOX-IND/Camptothesome.

a-f, cytotoxicity study of drug combination with varied molar ratios in MC38 (a-c) and CT26 (d-f) cells for 48 h by MTT assay. c,f, the IC50 values and combination index at different drug ratios. g-j, Schematic depicting the synthesis and preparation (g), representative size distribution by dynamic light scattering (DLS, h), cryoEM (i), and formulation stability monitoring (j) for DOX-IND/Camptothesome with optimal drug ratio (2/1). k, Physicochemical characterizations. l, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms of DOX-IND/Camptothesome. Thermotropic phase transition behavior was determined by MicroCal VP-capillary DSC. m, Leakage profile of DOX-IND in DOX-IND/Camptothesome under 4 °C. n, The release kinetics of DOX-IND from DOX-IND/Camptothesome under different conditions at 37 °C. Data in a,b,d,e,j,k,m,n are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Prolonged circulation and coordinated tumor delivery with precise drug ratio

The MTD of optimal DOX-IND/Camptothesome was determined and defined at the dose which did not kill mouse or cause more than 15% weight loss during the monitoring period[1, 21–23]. After a single intravenous administration of DOX-IND/Camptothesome at various drug doses, we observed that 26.6/18.9 (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT) mg/kg caused 2 mouse death, while 21.5/15.1 mg/kg neither did not kill mouse nor trigger significant mouse weight loss (Fig. 2a,b). Thus, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg was the MTD for DOX-IND/Camptothesome. Then, we investigated the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution in late-stage orthotopic CRC CT26 tumor model. Following an intravenous injection of DOX-IND/Camptothesome at MTD, blood was withdrawn at predetermined timepoints and was then processed for HPLC drug analysis[1]. Free CPT, SM-CSS-CPT, DOX, DOX-IND, Doxil and IND were also intravenously administered at the equivalent doses. At 24 h, the major organs were excised and imaged, then processed for the HPLC drug content measurement. Notably, while the free drugs were quickly eliminated from the blood with half-lives less than 0.6 h, our co-delivery nanomedicine elongated the blood circulation by providing 63.9-fold (vs free CPT), 37.3-fold (vs free IND), and 47.9-fold (vs free DOX) longer half-lives (Fig. 2c–e). More importantly, we confirmed that there was negligible difference in individual drug blood kinetics in DOX-IND/Camptothesome, indicating that the co-encapsulated drugs remained closely associated with each other in Camptothesome during circulation, further proving the excellent stability in vivo. Moreover, we showed that DOX-IND/Camptothesome was able to deliver drastically more drugs (54-fold vs free CPT, 40-fold vs free IND, and 45-fold vs free DOX) to tumor (Fig. 2g–j and Supplemental Fig. 3). The tumor delivery enhancement was also confirmed by ex vivo imaging based on CPT and DOX’s respective fluorescence (Fig. 2f–j). Lago ex vivo imaging corroborated that DOX-IND/Camptothesome markedly increases the drug delivery to tumors as evidenced by significantly higher intensity of CPT and DOX as compared to free CPT, SM-CSS-CPT, DOX, DOX-IND and Doxil. Cellular uptake of DOX-IND/Camptothesome in CT26 and MC38 colon cancer cells by flow cytometry indicated that DOX-IND/Camptothesome displayed higher cellular uptake in comparison with free CPT, SM-CSS-CPT, DOX, DOX-IND and Doxil (Supplementary Fig. 4). These results further demonstrated the superiority of tumor uptake of DOX-IND/Camptothesome. The remarkable improvement in pharmacokinetics and tumor delivery efficiency underpins a strong premise to boost antitumor efficacy in subsequent CRC tumor mouse models.

Fig. 2. DOX-IND/Camptothesome synchronized drug delivery to orthotopic tumors with synergistic drug ratio.

a,b, maximum tolerated dose (MTD) investigation. a, mouse weight change after intravenously injecting DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 2/1 molar ratio) once to mouse at various doses. b, a table depicting the mouse death and weight loss. c-g, blood kinetics (c-e) and tumor delivery (f-j) in orthotopic CRC CT26 tumor model (tumor: ~400 mg, n = 3) following single i.v. injection of DOX-IND/Camptothesome (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT, 21.5/15.1 mg/kg), free DOX (12.5 mg/kg), free IND (5 mg/kg), free DOX-IND (21.5 mg/kg), Doxil (12.5 mg/kg), SM-CSS-CPT (15.1 mg/kg) and free CPT (4 mg/kg). Blood kinetics and drug tumor uptake were analyzed by HPLC according to the established method[1]. In addition, CPT (g,h) and DOX (i,j) biodistribution was also assessed by drug’s fluorescence intensity through Lago optical imager and HPLC, respectively. Data in a-e, g-j are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

DOX-IND/Camptothesome beat the combination of Camptothesome and Doxil with diverse IDO1 inhibitors

The rationale of co-delivering drugs in a nanocarrier is to synchronize their in vivo pharmacokinetic profile and target to tumors with the precise drug ratio as determined and optimized via in vitro screening, as which could not be achieved via individual drug combination because of their different pharmacokinetic properties. Our comprehensive pharmacokinetics study corroborated that Camptothesome indeed can well orchestrate the in vivo delivery fate of co-loaded drugs and further improve the circulation time and tumor distribution. We posited that coordinated drug delivery in a single nanocarrier would render therapeutic benefits over separate drug co-injection, thus, enhancing the antitumor efficacy. To answer this question, we compared the antitumor efficacy between co-delivery Camptothesome and the co-administration of Camptothesome + Doxil + IND in a large subcutaneous MC38 CRC tumor mouse model (Fig. 3a–c). The equivalent doses for each drug were intravenously injected to mice via tail vein once when tumors reached ~300 mm3. Vehicle control-treated tumor grew rapidly, demonstrating the aggressive nature of this tumor type. Interestingly, the combination of separate drugs suppressed the tumor development significantly as compared to vehicle control. Nevertheless, DOX-IND/Camptothesome enabled notable tumor shrinkage from the starting points (~300 mm3) to ~80 mm3 on day 22 when vehicle control tumor reached the endpoint (Fig. 3a). Similarly, while co-injecting Camptothesome + Doxil + IND extended the mouse survival rate, but the survival time from the co-delivery nanomedicine group was far more significant longer, particularly when combined with PD-L1/PD-1 ICB therapy where 60% mice became tumor free (Fig. 3e,f). Moreover, to better decipher the benefits of using the DOX-IND/Camptothesome, DOX-IND, Camptothesome, DOX-IND + Camptothesome and Doxil (MTD dose) + α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1 were included as additional controls (Fig. 3g–j). While DOX-IND, Camptothesome, DOX-IND + Camptothesome or the combination with ICB showed significant tumor inhibition, DOX-IND/Camptothesome shrank tumors in six out of six mice, and its combination with PD-L1/PD-1 ICB resulted in tumor free in three out of five mice. Based on our previous study[1], Camptothesome can significantly upregulate intratumoral IDO1 expression, which were corroborated by the decreased ratios of Trp/Kyn in both plasma and tumors (Fig. 3h,i). In addition, our data unraveled that the ratios of Trp/Kyn in both plasma and tumors were markedly bolstered by the DOX-IND/Camptothesome, substantiating the enhanced IDO1 inhibitory ability in vivo. In addition to IND, BMS-986205 (BMS) and epacadostat (EPA) are another two frequently used IDO1 inhibitors[24–26]. Therefore, we were interested in understanding how our optimal DOX-IND/Camptothesome performs when compared to the combination of Camptothesome + Doxil with these IDO1 inhibitors. To full fill this goal, we intravenously treated mice bearing large MC38 tumors at equivalent drug doses. Our data showed that while BMS or EPA co-administration with Camptothesome + Doxil showed better tumor inhibition than that of IND combinatory therapy, the DOX-IND/Camptothesome elicited drastic tumor reduction that was more significant than various separate drug combination therapies, resulting in much longer mouse survival time (Fig. 4a–c). Apart from the PD-L1/PD-1 ICB combinations, we also analyzed the PD-1/CTLA-4 ICB combination as which is another pair of ICB commonly used in treating diverse cancers[6, 27, 28]. We found that combination with α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1 greatly fortified antitumor effects for DOX-IND/Camptothesome as compared to α-PD-L1 + α-CTLA-4, as well as rendered ICB combinations with co-use of separate drugs (Fig. 4d–f). These findings clearly upheld the notion that our co-delivery nanotherapeutic offers considerable advantages over drug combination for improved therapeutic delivery in treating CRC tumors.

DOX-IND/Camptothesome outperforms FOLFOX and FOLFIRI on anti-CRC efficacy and reduces systemic toxicities

FOLFOX and FOLFIRI, two combinations of chemotherapeutic drugs, are clinic benchmarks for treating CRC. Despite the improved therapeutic index against CRC, the combined chemodrgus integrated into one therapy gave rise to severe systemic toxicities[34, 35]. Here, we intended to investigate whether our optimal co-delivery nanotherapy could edge out these two toxic combination chemotherapies. To that end, DOX-IND/Camptothesome, and FOLFOX and FOLFIRI were intravenously injected into mice and tumor growth was closely monitored. The doses for both FOLFOX and FOLFIRI were adopted from the reported literatures[30–33]. Compared to vehicle control, FOLFOX and FOLFIRI delayed tumor development in a significant manner and prolonged mouse survival (Fig. 5a,b). However, these therapeutics effects were drastically enhanced in our DOX-IND/Camptothesome as which shrank the tumors from ~400 mm3 to half the size at the termination. And when ICB was co-used, our co-delivery nanotherapeutic eradiated tumors in 3 out of 6 mice (Fig. 5c). On day 20 post various treatments, blood was collected from mice. Comprehensive serum chemistry (Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Alanine Transaminase (ALT), glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), total protein, and creatinine) and the hematological cell counts (leukocytes, erythrocytes, hematocrit, and platelet) were analyzed (Fig. 5d–g). Noteworthily, FOLFOX caused significantly deviated levels for ALP, ALT, white blood cell, neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte, red cell distribution width, mean corpuscular volume/hemoglobin, and platelet; while ALP, neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte, eosinophil, mean corpuscular volume, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit were markedly affected by FOLFIRI. These data demonstrated the severe and widespread toxicities associated with the use of FOLFOX and FOLFIRI. In stark contrast, DOX-IND/Camptothesome did not trigger any noticeable side effects, confirming its outstanding safety profile.

DOX-IND/Camptothesome enhanced therapeutic outcome in metastatic orthotopic CRC model with enhanced CTL immunity

Metastatic CRC is an advanced form of CRC, compared to local CRC, it has greatly lower patient survival rate[37–39]. Our synergistic co-delivery Camptothesome enhanced efficacy in large subcutaneous CRC model. We wondered if it can also offer benefits in treating advanced metastatic CRC tumors. To answer this critical question, a late-stage metastatic orthotopic CRC model was established via injecting the CT26-Luc cells into the cecum subserosa[1, 36]. On day 9 post cancer cells injection, a big tumor mass (~400 mg) was observed in the cecum area and metastasis tumor nodules were noticed in many healthy tissues (liver, spleen, stomach, small and large intestine, rectum), confirming the advanced metastatic CRC model (Fig. 6a). In this study, we compared DOX-IND/Camptothesome with the combination of Onivyde + Doxil + IND. Onivyde was used because it is the liposomal irinotecan nanoformulation, and irinotecan is the FDA-approved CPT analogue and standard of care for treating metastatic CRC[40–42]. ICB was also applied alongside with other drugs. Based on the whole body bioluminescence imaging (BLI), we showed that α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1 regimen had negligible effect in inhibiting the tumor growth, as was reflected by the similar tumor development pattern and uncontrollable widespread metastasis as vehicle control (Fig. 6b–f), revealing the high aggressiveness of this tumor type. The co-administration of Onivyde + Doxil + IND regimen resulted in marked tumor suppression effect with reduced metastatic rates, but unfortunately its combination with ICB did not produce further improvements. DOX-IND/Camptothesome exhibited significant tumor inhibition in a way that was much greater than Onivyde + Doxil + IND, and with α-PD-L1 + α-PD-1 ICB, its antitumor efficacy was further enhanced. These were manifested by the minimized whole-body tumor BLI and inappreciable tumor metastatic frequency (Fig. 6b–f).

Fig. 6. DOX-IND/Camptothesome defeated the Onivyde-based drug combination in advanced metastatic orthotopic CT26-Luc CRC tumor models.

Late-stage orthotopic CRC model was established by inoculating the CT26-Luc cells into the cecum subserosa of mouse[1, 36]. On day 9, when primary tumors reached ~ 400 mg, various drug combinations were given to mice at equivalent doses (DOX-IND/SM-CSS-CPT 21.5/15.1 mg/kg, Doxil 12.5 DOX mg/kg, IND 5 mg/kg, 6.7 mg/kg for irinotecan in Onivyde). ICB was injected as described in Fig. 3. a, the whole mouse body and ex vivo images showing the primary tumor and metastasis. b, Primary tumor growth curve based on bioluminescence imaging (BLI). c, BLI to show the whole body tumor development. Red circle: tumor-free mouse. d, ex vivo tumor metastasis imaging (upper panel: photograph; lower panel: BLI). e, Normalized organ BLI radiance (vs liver in vehicle control). f, Heat map summarizing the metastasis frequency in diverse organs and tissues. Data in b,e are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

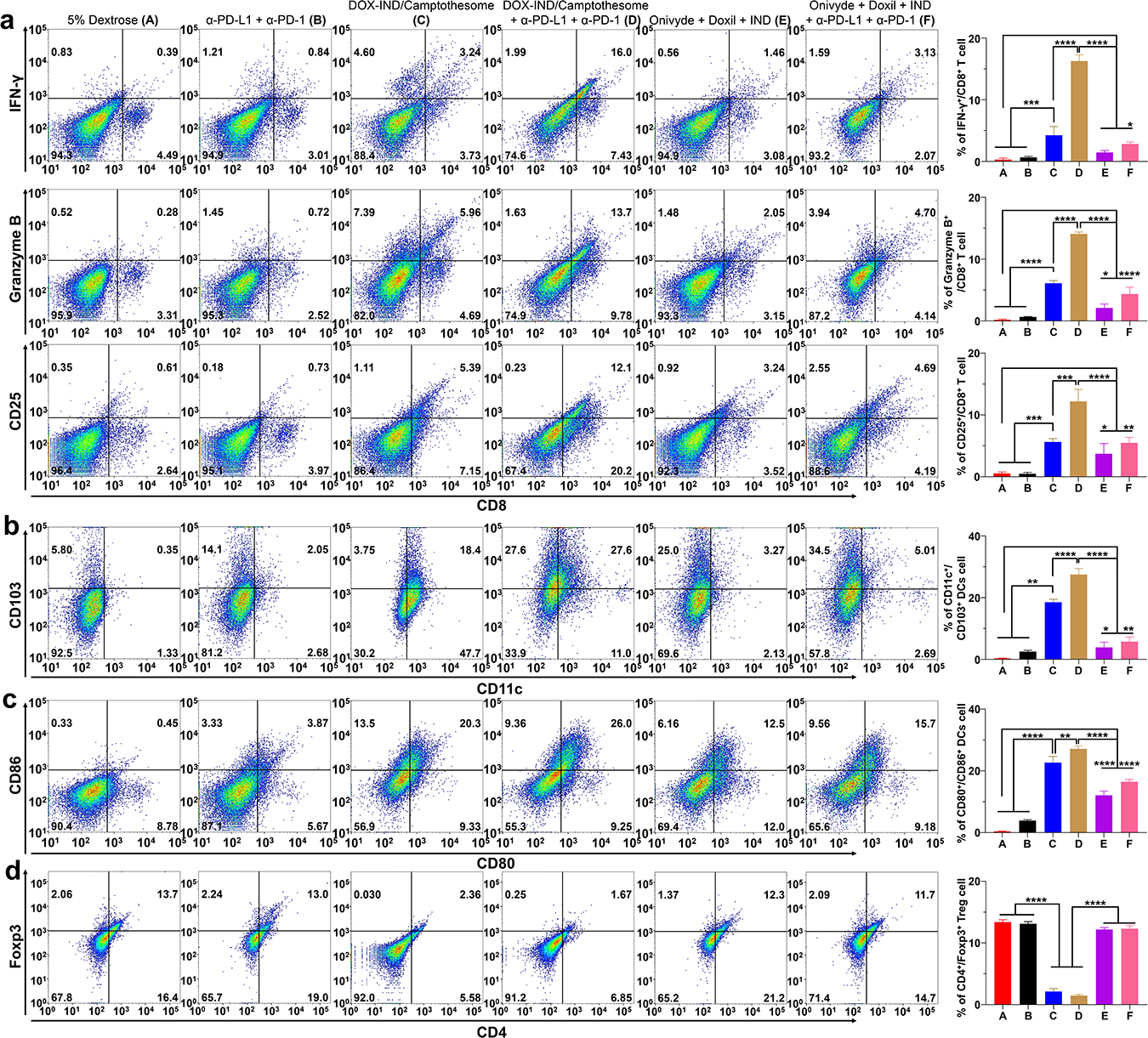

Further, to elucidate how this improved DOX-IND/Camptothesome modulates the immune responses, comprehensive immunophenotyping was performed using flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig. 5). This co-delivery strategy elicited potent antitumor immune responses by significantly enhancing calreticulin (the ‘eat-me’ signal hallmarks involved in triggering the immunogenic cell death (ICD)) and HMGB1 (adjust stimulus) expression (Supplemental Fig. 5). We demonstrated that there was a significant enhancement on the tumor-infiltrating IFN-γ+/CD8+, Granzyme B+/CD8+, and CD25+/CD8+ T cells, and CD103+/CD11c+ and CD86+/CD80+ dendric cells (DCs) in our co-delivery nanotherapeutic as compared to Onivyde + Doxil + IND (Fig. 7). These favorable immune modulation for recruitment and activation of CTLs and DCs were far more superior when ICB was combined. Of note, DCs with high CD103 expression is conducive to guiding CD8+ T cell development and anticancer immunity[43–45]. Moreover, to evaluate the effectiveness of IND-mediated reversal of IDO1-induced immunosuppression, intratumoral Tregs level was determined by measuring the Foxp3+/CD4+ T cells. While Onivyde + Doxil + IND did not significantly inhibit Tregs, the IND delivered in our DOX-IND/Camptothesome was attuned to drastically downregulate Tregs levels, thus overcoming the Tregs-modulated immunosuppression. We speculated that this immunosuppression reversal worked together with the ICD potential from CPT and DOX to markedly potentiate the efficacy of ICB in treating CRC tumors.

Fig. 7. Potent anti-CRC immune responses with reversal of immunosuppression.

On day 19, the tumors (from Fig. 6b) were excised and processed for comprehensive immunophenotyping analysis using flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometric plots of tumor-infiltrating IFN-γ+/CD8+, Granzyme B+/CD8+, and CD25+/CD8+ T cells (a); CD103+/CD11c+ (b) and CD86+/CD80+ (c) dendric cells and Foxp3+/CD4+ Tregs (d) cells and their respective quantification (right panel). Data (right panel) are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

Discussion

Combination therapy has been merging as the cornerstone in treating diverse cancers due to the insufficient efficacy from monotherapy and its ability to provide therapeutic interventions to different molecular targets[46–48]. These multidrug regimens are commonly attuned to realize therapeutic synergy, or a pharmacological effect that is greater than the sum of individual drug [49, 50]. Moreover, for advanced forms of cancers such as late-stage metastatic cancers, more aggressive therapies such as two or more drugs combination treatment is preferred in order to mitigate the tumor metastasis and improved patient survival time[51, 52]. These are the rationales underpinning the use of combination therapy. However, owing to the poor solubility and bioavailability, non-specific distribution to healthy tissues, and developed drug resistance, drug combination regimen has yet to produce the anticipated efficacy but bring about more severe adverse effects. While optimum drug ratios can be determined in vitro via systematic anticancer activity screening, it is challenging to deliver the combination regimen at the refined drug ratios to the targets (e.g., tumors) due to the chemical structure and pharmacokinetic property discrepancies of therapeutic agents.

To facilitate the administration of optimal drug combinations for enhanced CRC therapy, we developed a Camptothesome nanovesicle co-delivery platform, which can carry a DOX-derived IDO1 inhibitor, IND (DOX-IND) at a synergistic ratio that elongated the drug circulation half-lives, and synchronized pharmacokinetics of co-laden payloads, and delivered more drugs to tumor sites simultaneously at the precise optimal ratio, resulting in improved anti-CRC efficacy compared to co-administration of physical mixture of multiple drugs (Camptothesome + Doxil + IND, or Onivyde + Doxil + IND). More importantly, this synergistic combination nanotherapeutics outperformed the FOLFOX and FOLFIRI in controlling the tumor development and radically diminished detrimental systemic toxicities associated with FOLFOX and FOLFIRI. The minimized adverse effects were correlated to the stimuli-responsive drug release mechanism engineered in the SM-CSS-CPT[1], which was bridged via a disulfide linkage that is sensitive to the high glutathione levels in tumors[18–20].

This is significant as FOLFOX and FOLFIRI are two first-line combinatorial chemotherapeutic regimens for CRC, but their applications were hindered due to the toxicities. Our optimized co-delivery Camptothesome has the potential to replace those toxic combination treatment options and offer safer and more effective therapeutic efficacy for combating late-stage CRC. In addition to the improved pharmacokinetics and tumor uptake, the endocytic cellular uptake pathway may also account for the better anti-CRC effects in co-delivery Camptothesome[7, 53], as which can bypass the multidrug resistance mechanisms[54–59]. What’s more, FOLFOX and FOLFIRI, or co-injection of Onivyde + Doxil + IND, yielded significantly less synergy with ICB therapy than DOX-IND/Camptothesome in treating advanced CRC tumors. These were attributable to the facts that 1) FOLFOX and FOLFIRI had marked toxicities to lymphocytes, damaging the immune systems (Fig. 5d–g), and 2) the Onivyde + Doxil + IND regimen elicited much less CTLs responses (Fig. 7).

Vyxeos, comprised by the two chemotherapeutics, daunorubicin and cytarabine, is the first FDA-approved dual drug delivery liposomal nanodrug[60, 61]. Daunorubicin and cytarabine are directly loaded into the core of the liposome at the precise ratio via fixing the feeding amounts and ratios of both drugs. The regulatory approval of Vyxeos shed light to the feasibility of using nanocarrier to delivery multi-drugs simultaneously. In our co-delivery nanosystem, CPT was automatically embedded into the bilayer during the spontaneous nanovesicle self-assembly process, and then DOX-IND was encapsulated into the liposomal core via classic remotely loading strategy used in many FDA-approved nanoliposomes (Doxil, Onivyde, etc).

In summary, we implemented the best synergistic drug ratio into Camptothesome. The resultant optimal DOX-IND/Camptothesome nanosystem radically improved the pharmacokinetics and coordinated and controlled the delivery of co-entrapped payloads spatial-temporally, achieving the predefined precise and synergistic ratiometric doses in tumor sites, which led to the superior efficacy to the mixture of individual drug formulations as well as the FOLFOX and FOLFIRI, and the Onivyde-based combinatorial therapy. Considering 1) the procedures for preparing the co-delivery Camptothesome nanovesicle is well-established and similar to the FDA-approved liposomes, 2) the remarkable anti-CRC efficacy achieved against hard-to-treat advanced metastatic CRC tumors, 3) the ability to potentiate ICB therapy to eradicate late-stage CRC tumors with complete metastasis remission, and 4) the broad applicability to other cancer therapeutic agents, our fine-tuned DOX-IND/Campothesome nanotherapeutic regimen portends considerable translational potential and warrants further clinical investigation in treating various types of cancers, particularly the CRC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Startup Fund from the R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy at The University of Arizona and a PhRMA Foundation Research Starter Grant in Drug Delivery, and by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R35GM147002 and R01CA272487). We acknowledge the use of Mass Spectrometry in Analytical and Biological Mass Spectrometry Core Facility at the UArizona BIO5 Institute; the UArizona Translational Bioimaging Resource Core for the Lago live animal imaging; Tissue Acquisition and Cellular/Molecular Analysis Shared Resource (TACMASR) at UArizona Cancer Center (UACC) for the immunohistochemical staining; the UArizona University Animal Care Pathology Services for the serum chemistry and hematological counts; and the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource (FCSR) for flow cytometry studies at UACC, which are supported by NIEHS P30 ES006694 and NCI P30 CA023074. We also thank the Arizona State University’s John Cowley Center for Hight Resolution Electron Microscopy (the specific instrumentation used was supported by the NSF, MRI grant NSF1531991) for Cryo-EM.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

J.L. has applied for patents related to this technology. The other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.L.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplemental Information. All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable requests.

Reference

- [1].Wang Z, Little N, Chen J, Lambesis KT, Le KT, Han W, Scott AJ, Lu J, Immunogenic camptothesome nanovesicles comprising sphingomyelin-derived camptothecin bilayers for safe and synergistic cancer immunochemotherapy, Nat. Nanotechnol 16(10) (2021) 1130–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhao H, Lee C, Sai P, Choe YH, Boro M, Pendri A, Guan S, Greenwald RB, 20-O-acylcamptothecin derivatives: evidence for lactone stabilization, J Org Chem 65(15) (2000) 4601–4606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Haslam A, Prasad V, Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients With Cancer Who Are Eligible for and Respond to Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Drugs, JAMA Netw. Open 2(5) (2019) e192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Catenacci DVT, Hochster H, Klempner SJ, Keeping Checkpoint Inhibitors in Check, JAMA Netw. Open 2(5) (2019) e192546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Overman MJ, Ernstoff MS, Morse MA, Where We Stand With Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Deficient Mismatch Repair, Proficient Mismatch Repair, and Toxicity Management, Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 38 (2018) 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Huyghe N, Baldin P, Van den Eynde M, Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in colorectal cancer: what is the future beyond deficient mismatch-repair tumours?, Gastroenterol Rep. (Oxf) 8(1) (2020) 11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang Z, Li W, Park J, Gonzalez KM, Scott AJ, Lu J, Camptothesome elicits immunogenic cell death to boost colorectal cancer immune checkpoint blockade, J. Controlled Release 349 (2022) 929–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Muller AJ, DuHadaway JB, Donover PS, Sutanto-Ward E, Prendergast GC, Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an immunoregulatory target of the cancer suppression gene Bin1, potentiates cancer chemotherapy, Nat. Med 11(3) (2005) 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barenholz Y, Doxil(R)--the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned, J. Controlled Release 160(2) (2012) 117–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, Yoshino T, Paul J, Taieb J, Souglakos J, Shi Q, Kerr R, Labianca R, Meyerhardt JA, Vernerey D, Yamanaka T, Boukovinas I, Meyers JP, Renfro LA, Niedzwiecki D, Watanabe T, Torri V, Saunders M, Sargent DJ, Andre T, Iveson T, Duration of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer, N. Engl. J. Med 378(13) (2018) 1177–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Neugut AI, Lin A, Raab GT, Hillyer GC, Keller D, O’Neil DS, Accordino MK, Kiran RP, Wright J, Hershman DL, FOLFOX and FOLFIRI Use in Stage IV Colon Cancer: Analysis of SEER-Medicare Data, Clin. Colorectal Cancer 18(2) (2019) 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chou TC, Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies, Pharmacol. Rev 58(3) (2006) 621–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang Y, Huo M, Zhou J, Xie S, PKSolver: An add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel, Comput. Methods Programs Biomed 99(3) (2010) 306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Song W, Shen L, Wang Y, Liu Q, Goodwin TJ, Li J, Dorosheva O, Liu T, Liu R, Huang L, Synergistic and low adverse effect cancer immunotherapy by immunogenic chemotherapy and locally expressed PD-L1 trap, Nat. Commun 9(1) (2018) 2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Edwards SC, Hedley A, Hoevenaar WHM, Wiesheu R, Glauner T, Kilbey A, Shaw R, Boufea K, Batada N, Hatano S, Yoshikai Y, Blyth K, Miller C, Kirschner K, Coffelt SB, PD-1 and TIM-3 differentially regulate subsets of mouse IL-17A-producing gammadelta T cells, J. Exp. Med 220(2) (2023) e20211431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stephan SB, Taber AM, Jileaeva I, Pegues EP, Sentman CL, Stephan MT, Biopolymer implants enhance the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy, Nat. Biotechnol 33(1) (2015) 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang Z, Li W, Jiang Y, Tran TB, Cordova LE, Chung J, Kim M, Wondrak G, Erdrich J, Lu J, Sphingomyelin-derived nanovesicles for the delivery of the IDO1 inhibitor epacadostat enhance metastatic and post-surgical melanoma immunotherapy, Nat. Commun 14(1) (2023) 7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gamcsik MP, Kasibhatla MS, Teeter SD, Colvin OM, Glutathione levels in human tumors, Biomarkers : biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals 17(8) (2012) 671–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kuppusamy P, Li H, Ilangovan G, Cardounel AJ, Zweier JL, Yamada K, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Noninvasive imaging of tumor redox status and its modification by tissue glutathione levels, Cancer Res. 62(1) (2002) 307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xiong Y, Xiao C, Li Z, Yang X, Engineering nanomedicine for glutathione depletion-augmented cancer therapy, Chem. Soc. Rev 50(10) (2021) 6013–6041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lu J, Zhao W, Huang Y, Liu H, Marquez R, Gibbs RB, Li J, Venkataramanan R, Xu L, Li S, Li S, Targeted delivery of Doxorubicin by folic acid-decorated dual functional nanocarrier, Mol Pharmaceut 11(11) (2014) 4164–4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lu J, Huang Y, Zhao W, Marquez RT, Meng X, Li J, Gao X, Venkataramanan R, Wang Z, Li S, PEG-derivatized embelin as a nanomicellar carrier for delivery of paclitaxel to breast and prostate cancers, Biomaterials 34(5) (2013) 1591–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lu J, Zhao W, Liu H, Marquez R, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Xie W, Venkataramanan R, Xu L, Li S, An improved D-alpha-tocopherol-based nanocarrier for targeted delivery of doxorubicin with reversal of multidrug resistance, J. Controlled Release 196 (2014) 272–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cheong JE, Ekkati A, Sun L, A patent review of IDO1 inhibitors for cancer, Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat 28(4) (2018) 317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yue EW, Sparks R, Polam P, Modi D, Douty B, Wayland B, Glass B, Takvorian A, Glenn J, Zhu W, Bower M, Liu X, Leffet L, Wang Q, Bowman KJ, Hansbury MJ, Wei M, Li Y, Wynn R, Burn TC, Koblish HK, Fridman JS, Emm T, Scherle PA, Metcalf B, Combs AP, INCB24360 (Epacadostat), a Highly Potent and Selective Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) Inhibitor for Immuno-oncology, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 8(5) (2017) 486–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Beatty GL, O’Dwyer PJ, Clark J, Shi JG, Bowman KJ, Scherle PA, Newton RC, Schaub R, Maleski J, Leopold L, Gajewski TF, First-in-Human Phase I Study of the Oral Inhibitor of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase-1 Epacadostat (INCB024360) in Patients with Advanced Solid Malignancies, Clin. Cancer Res 23(13) (2017) 3269–3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Marin-Acevedo JA, Kimbrough EO, Lou Y, Next generation of immune checkpoint inhibitors and beyond, J. Hematol. Oncol 14(1) (2021) 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu Q, Qian W, Sun X, Jiang S, Small-molecule inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and more: FDA-approved novel therapeutic drugs for solid tumors from 1991 to 2021, J. Hematol. Oncol 15(1) (2022) 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu CM, Lee WC, Yu CY, Lan KL, Chang CH, Ting G, Lee TW, Comparison of the therapeutic efficacy of 188Rhenium-liposomes and liposomal doxorubicin in a 4T1 murine orthotopic breast cancer model, Oncol. Rep 27(3) (2012) 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wagner M, Roh V, Strehlen M, Laemmle A, Stroka D, Egger B, Trochsler M, Hunt KK, Candinas D, Vorburger SA, Effective treatment of advanced colorectal cancer by rapamycin and 5-FU/oxaliplatin monitored by TIMP-1, J. Gastrointest Surg 13(10) (2009) 1781–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Guan Y, Kraus SG, Quaney MJ, Daniels MA, Mitchem JB, Teixeiro E, FOLFOX Chemotherapy Ameliorates CD8 T Lymphocyte Exhaustion and Enhances Checkpoint Blockade Efficacy in Colorectal Cancer, Front. Oncol 10 (2020) 586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhu G, Zhao M, Han Q, Tan Y, Sun YU, Bouvet M, Clary B, Singh SR, Ye J, Hoffman RM, Combination of Trabectedin With Irinotecan, Leucovorin and 5-Fluorouracil Arrests Primary Colorectal Cancer in an Imageable Patient-derived Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Model, Anticancer Res. 39(12) (2019) 6463–6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ishihara Y, Matsunaga K, Iijima H, Hasegawa G, Suzuki T, Sato A, Kobayashi T, Yang M, Hoffman RM, The combination of 5-FU, leucovorin and CPT-11 (FOLFIRI) prolongs survival through inhibition of metastasis in an orthotopic model of colon cancer, Anticancer Res. 30(2) (2010) 403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gresham G, Sidhu J, Malhi N, Cheung WY, Predicting toxicities from adjuvant treatment in a population-based cohort of early colon cancer (CC) patients (pts): A strategy to improve use of curative chemotherapy, J. Clin. Oncol 32(3_suppl) (2014) 412–412. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huy TL, Bui MH, Dinh TC, Xuyen HTH, Efficacy and Toxicity of Folfoxiri for Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer, Open Access Maced. J. Med .Sci 7(24) (2019) 4244–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang Y, Davis C, Ryan J, Janney C, Pena MM, Development and characterization of a reliable mouse model of colorectal cancer metastasis to the liver, Clin. Exp. Metastasis 30(7) (2013) 903–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gustavsson B, Carlsson G, Machover D, Petrelli N, Roth A, Schmoll HJ, Tveit KM, Gibson F, A review of the evolution of systemic chemotherapy in the management of colorectal cancer, Clin. Colorectal Cancer 14(1) (2015) 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Marques RP, Duarte GS, Sterrantino C, Pais HL, Quintela A, Martins AP, Costa J, Triplet (FOLFOXIRI) versus doublet (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) backbone chemotherapy as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol 118 (2017) 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ismaili N, Treatment of colorectal liver metastases, World J. Surg. Oncol 9 (2011) 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, Rosen LS, Fehrenbacher L, Moore MJ, Maroun JA, Ackland SP, Locker PK, Pirotta N, Elfring GL, Miller LL, Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. Irinotecan Study Group, N. Engl. J. Med 343(13) (2000) 905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rougier P, Van Cutsem E, Bajetta E, Niederle N, Possinger K, Labianca R, Navarro M, Morant R, Bleiberg H, Wils J, Awad L, Herait P, Jacques C, Randomised trial of irinotecan versus fluorouracil by continuous infusion after fluorouracil failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, Lancet 352(9138) (1998) 1407–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fuchs C, Mitchell EP, Hoff PM, Irinotecan in the treatment of colorectal cancer, Cancer Treat. Rev 32(7) (2006) 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lu J, Liu X, Liao YP, Salazar F, Sun B, Jiang W, Chang CH, Jiang J, Wang X, Wu AM, Meng H, Nel AE, Nano-enabled pancreas cancer immunotherapy using immunogenic cell death and reversing immunosuppression, Nat. Commun 8(1) (2017) 1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Broz ML, Binnewies M, Boldajipour B, Nelson AE, Pollack JL, Erle DJ, Barczak A, Rosenblum MD, Daud A, Barber DL, Amigorena S, Van’t Veer LJ, Sperling AI, Wolf DM, Krummel MF, Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity, Cancer cell 26(5) (2014) 638–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF, Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity, Nature 523(7559) (2015) 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bastos DA, Ribeiro SC, de Freitas D, Hoff PM, Combination therapy in high-risk stage II or stage III colon cancer: current practice and future prospects, Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol 2(4) (2010) 261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yeku OO, Longo DL, Combination Therapy, Including Bevacizumab, for Advanced Colorectal Cancer, N. Engl. J. Med 388(18) (2023) 1711–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jaaks P, Coker EA, Vis DJ, Edwards O, Carpenter EF, Leto SM, Dwane L, Sassi F, Lightfoot H, Barthorpe S, van der Meer D, Yang W, Beck A, Mironenko T, Hall C, Hall J, Mali I, Richardson L, Tolley C, Morris J, Thomas F, Lleshi E, Aben N, Benes CH, Bertotti A, Trusolino L, Wessels L, Garnett MJ, Effective drug combinations in breast, colon and pancreatic cancer cells, Nature 603(7899) (2022) 166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Duarte D, Vale N, Evaluation of synergism in drug combinations and reference models for future orientations in oncology, Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov 3 (2022) 100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zoetemelk M, Ramzy GM, Rausch M, Koessler T, van Beijnum JR, Weiss A, Mieville V, Piersma SR, de Haas RR, Delucinge-Vivier C, Andres A, Toso C, Henneman AA, Ragusa S, Petrova TV, Docquier M, McKee TA, Jimenez CR, Daali Y, Griffioen AW, Rubbia-Brandt L, Dietrich PY, Nowak-Sliwinska P, Optimized low-dose combinatorial drug treatment boosts selectivity and efficacy of colorectal carcinoma treatment, Mol. Oncol 14(11) (2020) 2894–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hernandez Dominguez O, Yilmaz S, Steele SR, Stage IV Colorectal Cancer Management and Treatment, J. Clin. Med 12(5) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Carethers JM, Systemic treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: tailoring therapy to the tumor, Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol 1(1) (2008) 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wang Z, Cordova LE, Chalasani P, Lu J, Camptothesome Potentiates PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Improved Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Immunochemotherapy, Mol. Pharm 19(12) (2022) 4665–4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wong HL, Bendayan R, Rauth AM, Xue HY, Babakhanian K, Wu XY, A mechanistic study of enhanced doxorubicin uptake and retention in multidrug resistant breast cancer cells using a polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticle system, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 317(3) (2006) 1372–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li Y, Gao L, Tan X, Li F, Zhao M, Peng S, Lipid rafts-mediated endocytosis and physiology-based cell membrane traffic models of doxorubicin liposomes, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858(8) (2016) 1801–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ortiz R, Quinonero F, Garcia-Pinel B, Fuel M, Mesas C, Cabeza L, Melguizo C, Prados J, Nanomedicine to Overcome Multidrug Resistance Mechanisms in Colon and Pancreatic Cancer: Recent Progress, Cancers 13(9) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sivak L, Subr V, Tomala J, Rihova B, Strohalm J, Etrych T, Kovar M, Overcoming multidrug resistance via simultaneous delivery of cytostatic drug and P-glycoprotein inhibitor to cancer cells by HPMA copolymer conjugate, Biomaterials 115 (2017) 65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Liu J, Zhao Z, Qiu N, Zhou Q, Wang G, Jiang H, Piao Y, Zhou Z, Tang J, Shen Y, Co-delivery of IOX1 and doxorubicin for antibody-independent cancer chemo-immunotherapy, Nat. Commun 12(1) (2021) 2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Oh JM, Choi SJ, Lee GE, Kim JE, Choy JH, Inorganic metal hydroxide nanoparticles for targeted cellular uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, Chem. Asian J 4(1) (2009) 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mayer LD, Tardi P, Louie AC, CPX-351: a nanoscale liposomal co-formulation of daunorubicin and cytarabine with unique biodistribution and tumor cell uptake properties, Int. J. Nanomedicine 14 (2019) 3819–3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Dicko A, Kwak S, Frazier AA, Mayer LD, Liboiron BD, Biophysical characterization of a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin, Int. J. Pharm 391(1–2) (2010) 248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplemental Information. All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable requests.