Abstract

Thalidomide, pomalidomide and lenalidomide, collectively referred to as immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs), are frequently employed in proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) as cereblon (CRBN) E3 ligase-recruiting ligands. However, their molecular glue properties that co-opt the CRL4CRBN to degrade its non-natural substrates may lead to undesired off-target effects for the IMiD-based PROTAC degraders. Herein, we reported a small library of potent and cell-permeable CRBN ligands, which exert high selectivity over the well-known CRBN neo-substrates of IMiDs by structure-based design. They were further utilized to construct bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) degraders, which successfully depleted BRD4 in the tested cells. Overall, we reported a series of functionalized CRBN recruiters that circumvent the promiscuity from traditional IMiDs, and this study is informative to the development of selective CRBN-recruiting PROTACs for many other therapeutic targets.

Keywords: CRBN, IMiDs, Targeted Protein Degradation, PROTAC

Graphical Abstract

A small library of compounds based on isoindolinone or 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole were constructed as potential cereblon binders. Their activity was explored using cell-based and biochemical binding assays. Several potent, selective, and cell-permeable CRBN ligands were identified. A potent BRD4 degrader was successfully developed from the 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole-derived ligand, suggesting the potential for these ligands to develop PROTAC degraders against many other therapeutic targets.

Introduction

About two decades ago, proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) was first introduced as an intriguing concept for targeted protein degradation (TPD).[1] Since then, this strategy has achieved significant advancement in TPD therapeutic modality and has progressed from academic exercise to clinical trials.[2] These heterobifunctional small molecules have a ligand targeting E3 ubiquitin ligase tethered with a warhead targeting protein of interest (POI). In this way, they are able to recruit an E3 ubiquitin ligase to selectively degrade the POI by hijacking the intracellular ubiquitin-proteasome system. There are more than 600 E3 ubiquitin ligases available in human proteome, but these large multicomponent protein complexes are proven difficult to target as many of them lack appropriate binding sites to accommodate small-molecule ligands,[3] therefore limiting their application in PROTAC development.

Cereblon (CRBN) is the substrate receptor of CUL4-RBX1-DDB1-CRBN (CRL4CRBN) E3 ubiquitin ligase, and it is found to be a target of immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs) including thalidomide, pomalidomide and lenalidomide.[4] IMiDs showed significant therapeutic efficacy in a variety of hematological malignancies. Studies on the mechanism of action of IMiDs revealed that CRL4CRBN could mediate downregulation of a number of CRBN neo-substrates such as transcription factors Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3), or casein kinase 1α (CK1α).[5][6] IMiDs facilitate the interaction between CRBN and CRBN neosubstrates, leading to their poly-ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. In the crystal structure of CRBN-pomalidomide-IKZF1 (PDB 6H0F), the glutarimide moiety of pomalidomide binds to the Tri-Trp pocket on CRBN surface, the phthalimide ring packs against IKZF1 ZF2-ZF3, and its C4 amino group forms a water-mediated hydrogen bond with the IKZF1 Q146 (IKZF3 Q147), contributing to the binding to IKZFs.[5f] With a C4 amino substituent introduced to the phthalimide ring, pomalidomide and lenalidomide have significantly increased IKZF1/3 depletion rates and potency. New generations of cereblon E3 ligase modulating drugs are under development. For example, CC-122 in which the phthalimide motif is replaced by an amino-methylquinazoline moiety degrades only IKZF1/3 without any effect on CK1α.[7] CC-885 and CC-90009 with an extended urea and chlorophenyl group could recruit CRBN to degrade the translation termination factor G1 to S phase transition 1 (GSPT1), which cannot be degraded by the first-generation IMiDs.[8] Recently, selective degraders of IKZF2 (e.g. DKY-709) was also reported and it has a great potential for cancer immunotherapy.[9] These compounds possess the binding ability to CRBN by sharing a common substituted glutarimide core structure, but subtle differences in the remainder of the molecule resulted in significant differences in their neosubstrate specificity. It suggests that the activity of IMiDs can be fine-tuned by mutating the phthalidomide motif to facilitate or disrupt their interaction with different CRBN neosubstrates, raising the potential of developing more selective CRBN ligands via structural modification.

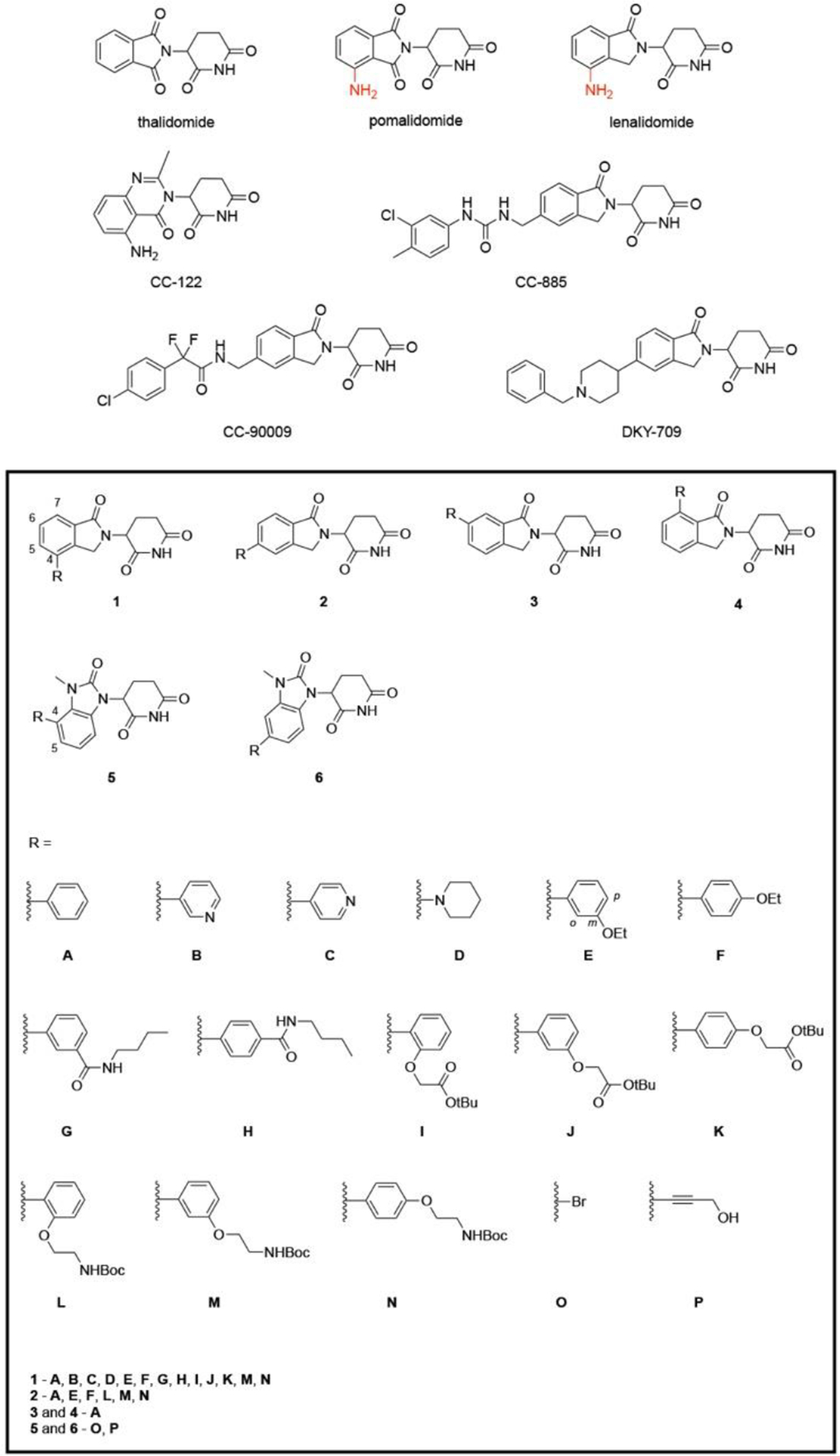

Since IMiD-derived PROTACs are likely to trigger off-target degradation, we aim to develop more selective ligands for CRBN recruitment. In our previous study, 4-phenyl lenalidomide 1A has been identified as a better binder of CRBN in the in-cell ELISA assay.[10] Meanwhile, it does not induce the degradation of IKZF1 or IKZF3. Based on this lead compound, we designed a small library of lenalidomide analogs, where the isoindolinone was substituted by an aromatic group or a saturated six-membered ring (Scheme 1). There are 4 modifiable positions on the isoindolinone, but based on our result, phenyl substituents on positions C6 and C7 are less tolerated than C4 and C5 positions for binding to CRBN. Therefore, most compounds with phenyl substituents are designed with 4- and 5-substitutions. Meanwhile, we also designed a series of CRBN ligands based on a distinct pharmacophore in CRBN binders 5 and 6 bearing a 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole reported in patent literature.[11]

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures of immunomodulatory agents and CRBN ligands bearing isoindolinone or 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole cores.

Results and Discussion

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) of CRBN Ligands Were Analysed by Cellular and Biochemical Assays

We previously reported a cell-based target engagement (TE) assay for the identification of cell-permeable CRBN E3 ligase ligands.[10] The principle of this assay is illustrated in Figure 1a. When cells are co-treated with CRBN ligands and a CRBN-recruiting PROTAC, the former would compete with PROTAC for the active binding site on CRBN, leading to different degrees of abolishment of the POI degradation. Our group developed a potent Histone Deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) degrader (Figure 1a) by tethering a selective HDAC6 inhibitor Nexturastat A (Next-A) with pomalidomide. Degrader 1 exhibits remarkably degradation efficiency for HDAC6 with half maximal degradation concentration (DC50) of 1.6 nM and maximal degradation (Dmax) of 86%.[12] By analyzing HDAC6 level in this in-cell ELISA after the treatment of degrader 1 and a potential CRBN ligand, this assay can differentiate the cellular activity of CRBN ligands to the native stage of CRBN. The cell-based assay also allows us eliminate ligands with poor cell permeability, low cellular stability and/or short in-cell retention time.

Figure 1.

Relative binding affinities of CRBN ligands to CRBN in cellular and biochemical assays. a) Principle of the cellular target engagement binding assay, and the structure of HDAC6-targeting PROTAC degrader 1. b) Results of the cell-based TE assay. MM.1S cells were pretreated with 3 μM CRBN ligand or DMSO for 1 h, then with 100 nM degrader 1 or DMSO for 5 h, HDAC6 levels are analyzed by in-cell ELISA. Bar graphs were generated as means of HDAC6 relative level (n = 3) with ±SD as the error bar. c) Result of the FP competition assay. 100 nM recombinant DDB1/CRBN protein complex was incubated with 8 nM fluorescent probe (FITC-thalidomide) and 150 nM CRBN binder or DMSO in the assay buffer 50 mM HEPES, 75 mM NaCl, 0.01% Triton X-100, pH 7.4, the total volume is 20 uL. Fluorescence polarization signal was converted to % inhibition by comparing to DMSO control.

Using this assay, we screened a library of synthetic lenalidomide derivatives with various building blocks (A-D) installed at different sites of the isoindolinone motif (1-4) as shown in Scheme 1. Pomalidomide and thalidomide were selected as positive controls for comparison with these compounds. As CRBN binders, the affinity drops in the order of pomalidomide, lenalidomide, and thalidomide.[5f] According to our previous study,[10] 3 μM of pomalidomide or lenalidomide can abolish approximate 50% of HDAC6 degradation induced by 100 nM degrader 1 relative to the vehicle control, therefore providing an ideal window for comparing the potency of these analogs with the parent compounds. The same condition was adopted in this study. All the compounds including two IMiD controls were tested in triplicate at the concentration of 3 μM, and the average were taken as the final result.

To learn the impact of the substitution position of the phenyl group to potency, we synthesized compounds 1A, 2A, 3A and 4A with 4-, 5-, 6- or 7-substituted phenyl group, respectively. The introduction of 4-substituent in 1A brought the greatest improvement in the cellular binding to CRBN, while the second-best came from the 5-substituted 2A. The 6- and 7-phenyl substituted ligands 3A and 4A are much less potent than 1A and 2A (Figure 1b). This potency trend could be explained by the steric hinderance introduced by the substituent. Based on the CRBN-lenalidomide-DBB1 complex crystal structure (PDB 4CI2), the carbonyl in isoindolinone formed a hydrogen bond with ASN337 at the ligand-protein interface. The 6- and 7-substitution nearby the carbonyl may block the interaction and impede the complex formation. We also replaced the 4-phenyl group by an aromatic pyridine or a saturated piperidine ring. Our data in Figure 1b indicated that pyridine-substituted compounds 1B and 1C slightly decreased the cellular activity to CRBN, while piperidine-substituted compound 1D had similar activity as 1A or 2A.

In the next stage SAR study, more compounds with substituted phenyl group (E-N) installed on the C4- and C5-positions were prepared using a modular chemistry platform we reported in a recent study.[13] Various substituents including ethoxy, amide, tBu ester and Boc-protected amino groups were introduced to the ortho-, meta-, or para-positions of the phenyl group. Linkers can be easily attached to the phenyl group by replacing the tBu and NHBoc moiety, enabling further development of CRBN-recruiting PROTACs derived from these ligands. No obvious correlation was observed between the activity and the substitution pattern (Figure 1b). For example, the activity of compounds bearing meta-OEt (E) are weaker than those bearing para-OEt (F), whereas the compound 1G with meta-CONH-nBu is stronger than compound 1H with para-CONH-nBu. For the compounds with the tBu-protected substituent, ortho-substitution (1I) is better than meta- and para-substitution (1J, 1K), but this rule does not apply to compounds bearing the Boc-protected amino group (L, M, and N).

In addition to many of the lenalidomide analogs, we also prepared four compounds (5O, 5P, 6O, 6P) with a distinct core structure. A bromo (O) or a propargyl hydroxyl group (P) is attached to the phenyl ring as precursors. It turned out that the bromo-substituted ligands 5O and 6O exhibited highest cellular activity among all the tested compounds, especially 5O, which abolished approximately 96% of HDAC6 degradation in this condition. Compound 6O also abolished nearly 90% of HDAC6 degradation. Replacing the bromo group with the propargyl hydroxyl group slightly decreased the cellular activity, but the activity is still comparable to that of pomalidomide. Our studies indicate that the isoindolinone core in lenalidomide can be replaced by a 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole motif and still maintain high cellular activity.

After screening of the library of compounds, we discovered several promising ligands that possess higher cellular potency than pomalidomide. Assuming other properties of these analogs are similar in the given cellular context, the difference in readouts is likely a result of different binding affinities in the cell. We next selected ligands with activity that is higher than or comparable to pomalidomide in the cellular context for further evaluation of their binding affinity using a fluorescence polarization (FP) competition assay. Lenalidomide was included as a positive control. Compounds were incubated with his8-DDB1ΔB/his8-CRBN protein complex to displace the bound FITC-thalidomide on CRBN, and percentage of displacement was calculated as % inhibition. As shown in Figure 1c, the CRBN binding affinity of the phenyl substituted ligands 1A and 2A was still stronger than that of the pyridine-substituted ligands 1B and 1C in this biochemical assay, comparable to the parent IMiD compounds and the piperidine-substituted ligand 1D. The lenalidomide-derived compounds 2E, 1F and 2L, as well as the benzimidazole-based compounds 5O and 5P exhibited strong binding to CRBN in both biochemical and cellular assays, indicating they are promising CRBN binders. The benzimidazole-type ligands are significantly better than other lenalidomide derivatives in cellular assay compared to their performance in FP assay, probably resulted from their relatively higher permeability, suggesting the benzimidazole-type compounds might be an interesting class of cellular active CRBN ligands that are worth further exploration. Compounds 1E, 1G and 2M also showed better performance in the cellular binding test than in FP assay, this difference may reflect physiochemical and metabolic properties of the compounds besides binding affinity. Overall, the results from FP assay and cellular TE assay are relatively consistent to each other.

New CRBN Ligands Do not Induce the Degradation of Classical CRBN Neosubstrates

To investigate the activity of our ligands against some of well-known CRBN neosubstrates, we selected ten representative ligands from the previous binding assays, most of which have a functional group where a linker could be attached. They are tested in MM.1S cell line, and no significant degradation of IKZFs were observed at 1 μM concentration of the compounds in western blot result (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Selectivity of new CRBN ligands and structural modeling of CRBN-pomalidomide/1A complexes. a) Activity of selected CRBN ligands towards CRBN neosubstrate degradation. MM.1S cells were treated with 1 μM CRBN ligands or DMSO for 6 h and degradation of CRBN neosubstrates were examined by immunoblot assay. b) Crystal structure of CRBN-pomalidomide-IKZF1 (PDB 6H0F). C5 and C6 positions on the ligand for potential ring substituent are circled out in green, which are too close to IKZF1. Replacing NH2 with a ring disrupts the important H-bond network between CRBN E377 and IKZF1 GLN146. c) It is impossible to fit ligand 1A into the pocket without disturbing the known ternary binding pose of CRBN-IKZF1, as further evidenced by docking which only gave poses outside of pocket with poor scores. d) The same docking as in (c) but was performed with pomalidomide, the docked pose fully overlaps with the correct crystal pose, and with a favorable score of −12.4. e) Docking of 1A to CRBN only from a different crystal structure (PDB 4TZ4) with E377 more open gives crystal overlapping poses, and with a favorable score of −10.9, slightly better than the 3 canonical CRBN ligands, consistent with the experimental results.

Computational modeling was conducted to rationalize the selectivity of these ligands over CRBN neosubstrates. With our ligands sharing the same pharmacophore of the classic IMiDs, the ligand binding pocket on CRBN should be the same, and the core structure in the binding pose should overlap between our ligands and pomalidomide in the crystal structure. Based on crystal structure 6H0F (Figure 2b), aromatic rings on C5 and C6 positions are too close to IKZF1, directly disrupting its crystal binding pose, therefore leading to the observed abolishment of molecular glue properties seen as no IKZF1 degradation. Although potential C4 substituents do not clash with IKZF1, in this region there is an important water-mediated hydrogen bond bridge formed between CRBN E377 and IKZF1 GLN146. A ring substituent on C4-position would not fit without disturbing this hydrogen bond bridge. The NH2 group that helps IKZF1 binding is also replaced in our ligands.

An attempt was made to force ligand 1A into the pocket of the CRBN-IKZF1 crystal structure by docking (by smina, same below), and it turns out that 1A cannot fit into the pocket, only giving poses on the outside with poor scores of −5.6 the best (Figure 2c). As a control, pomalidomide was docked into the crystal structure of CRBN-IKZF1 (Figure 2d). The best scoring pose perfectly aligns with the crystal pomalidomide, with a favorable docking score of −12.4. As a second control, our ligand 1A was docked into the CRBN-lenalidomide crystal structure (PDB 4TZ4, no IKZF1 or other substrate) where the E377 is more open, the docked pose of 1A overlaps well with the crystal lenalidomide, with a very favorable score of −10.9, slightly better than lenalidomide (−9.5), pomalidomide (−9.3) or thalidomide (−9.3) (Figure 2e). The docking result of the second control is consistent with the good experimental binding achieved for our ligands with CRBN. Overall, our new ligands with ring substituents on C4, C5, or C6 positions make IKZF1 structurally incompatible for E3 ligase binding and the downstream ubiquitin degradation, thus abolishing the molecular glue properties of the ligands for IKZFs.

BRD4 PROTACs Derived from the New CRBN Ligands Are Potent BRD4 Degraders

In order to demonstrate the utility of new CRBN ligands from our study, we incorporated the benzimidazole-based CRBN binders into PROTACs. We previously reported a Rapid-TAC platform for rapid and high-throughput preparation of PROTACs via the aldehyde-hydrazide coupling reaction.[14] As shown in Figure 3a, intermediates 5X and 6X with an aldehyde group installed at the ortho-, meta- and para-positions of the C4 or C5 phenyl group on the 2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole core were conjugated with a BRD4 inhibitor, JQ1 bearing a hydrazide functional group, to construct a series of PROTACs 5Y and 6Y that target BRD4 for degradation.

Figure 3.

BRD4 PROTACs derived from CRBN ligands with a 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole core. a) Structures of aldehyde intermediates 5X, 6X and BRD4 degraders 5Y, 6Y derived from CRBN ligands with a 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole core. b) Western blot result of BRD4 degradation induced by BRD4 degraders 5Y and 6Y series. SU-DHL-4 cells were treated with 100 nM or 1 μM degrader or DMSO for 24 h. c) Time course of the most potent BRD4 degrader 5Y-3. SU-DHL-4 cells were treated with 100 nM 5Y-3 and incubated for different times up to 12 h as indicated. d) Mechanism study of 5Y-3. SU-DHL-4 cells were pretreated with 1 μM bortezomib, MG132, MLN4924 or DMSO for 1 h, followed by treatment of 100 nM 5Y-3 for 24 h. e) Dose response of 5Y-3 in SU-DHL-4 and MV-4–11 cells. Cells were treated with 5Y-3 of different concentrations as indicated for 24 h. f) Selectivity test of 1G, 5P, 6P and 5Y-3. SU-DHL-4 cells were treated with 1 μM CRBN ligands or 100 nM 5Y-3 or DMSO for 8 h.

BRD4 degradation activity of these PROTACs were tested in a human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell line, SU-DHL-4, as well as a human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell line, MV-4–11, in which BRD4 has been identified as an effective therapeutic target and they are more sensitive to BRD4 inhibition and knockdown.[15] 5Y and 6Y were first screened at 100 nM and 1 μM concentrations in SU-DHL-4 cells. Among them, 5Y-3 was the most potent one and it completely depleted BRD4 at 100 nM after 24 h treatment (Figure 3b). Since all linkers are relatively rigid, it is not surprising that only one of them worked. Result from the time course analysis showed that 5Y-3 started to degrade BRD4 after 6 h, and most of BRD4 was depleted after 12 h (Figure 3c). Furthermore, BRD4 was rescued by the co-treatment of the proteasome inhibitors, bortezomib and MG132, and the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 (Figure 3d), indicating that the BRD4 degradation mediated by 5Y-3 followed the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Dose response of 5Y-3 was also tested in both SU-DHL-4 and MV-4–11 cell lines. Results showed that the effective dose of 5Y-3 is 100 nM or higher in SU-DHL-4 cell line, but it can be as low as 10 nM in MV-4–11 cell line (Figure 3e). Compared to the previous BRD4 inhibitors or BRD4 PROTAC degraders such as dBET1, the PROTAC 5Y-3 exhibits favorable cellular activity of BRD4 degradation.

We further examined the activity of 5Y-3 and selected ligands 1G, 5P and 6P on neosubstrate degradation in SU-DHL-4 cell line. Ligands were treated at a concentration of 1 uM, while 5Y-3 was treated at its effective dose 100 nM. We found that neither the selected ligands nor the PROTAC induced IKZFs degradation (Fig 3f). It suggests that the ligands reported in this study have a great potential to be further developed into CRBN-recruiting PROTACs against the desired therapeutic target with high selectivity.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a small library of compounds based on isoindolinone or 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole cores as potential CRBN E3 ligase ligands. In-cell ELISA based target engagement assay and FP competition assay were employed to evaluate the relative binding affinity of these compounds to cereblon. Their structure-activity relationship was explored, and our results suggested that introducing a 4-phenyl group to the IMiD core structures contribute the most to the binding to CRBN. Encouragingly, several promising cell-permeable ligands were identified from the binding assays. These ligands did not induce the degradation of well-known CRBN neosubstrates IKZFs. Structural modeling analysis provided further evidence and rationalization for this selectivity. The selective CRBN ligands do not degrade known neosubstrates IKZFs, and may expand the utility of CRBN-recruiting PROTACs. PROTACs derived from these ligands can be used as selective chemical probes to knock down specific targets with higher selectivity. We also found that the replacement of the isoindolinone by a 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole core could lead to CRBN ligands with potent activity in cellular and biochemical assays. The new CRBN ligands were applied to developing potent BRD4 PROTAC degraders which do not induce IKZFs degradation. Further studies on CRBN ligands based on the 2,3-dihydro-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazole core are ongoing and will be reported in the near future.

Experimental Section

Expression and Purification of DDB1/CRBN

All protein constructs were generated by standard PCR molecular cloning strategy. The insert DNAs of human DDB1ΔB and human CRBN were amplified from the plasmids pESF140_HisSpy_DDB1ΔB (Addgene, 124213) and pAJ075_hsCRBN (Addgene, 124214), respectively, and then cloned into pFastBac vector. Recombinant proteins were expressed as N-terminal His8 tagged DDB1ΔB, CRBN fusions in Trichoplusia ni Hi5 insect cells using Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen). Cells were resuspended in buffer containing 25 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and lysed by dounce homogenizer. Following ultracentrifuge, the supernatant of cell lysate was purified over Ni-NTA resins (Qiagen). Proteins were further purified by ion exchange chromatography (Source 15Q, GE Healthcare) and then size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200, GE Healthcare) in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). The protein complex-containing fraction was concentrated using 30K MWCO Pierce protein concentrators (Thermo Scientific, 88529) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen at 80 μM.

Fluorescence Polarization

The fluorescence probe was prepared by labelling thalidomide 4’-oxyacetamide-alkylC4-amine (TOCRIS, 6469) by 5(6)-SFX(TOCRIS, 6488). The assay was carried out in black Nunc™ ShallowWell 384-well assay microplates (267461) using the buffer 50 mM HEPES, 75 mM NaCl, 0.01% Triton X-100, pH 7.4. After mixing the DDB1ΔB/CRBN protein (100 nM in 10 μL), fluorescence probe (8 nM in 5 μL) and compound (150 nM in 5 μL), the plate was incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. The polarization signals (mP) were acquired by PHERAstar FS Plate Reader (FP 485-520-520nM Optic module).

Cell Culture

Human cell lines MM.1S (CRL-2974, derived from female), SU-DHL-4 (CRL-2957, derived from male) and MV-4–11 (CRL-9591, derived from male) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). MM.1S cells and SU-DHL-4 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. MV-4–11 cells were cultured in Iscove’s modification of DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. All the cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Western Blotting

Cells were treated with test compounds at indicated doses. After incubation for indicated time, cells were collected, washed twice with cold PBS, and then lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor and 1 mM PMSF. Supernatant was collected after centrifuge at 16,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes. Protein concentration was measured by the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein was mixed with 4X Laemmli Loading Dye and denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes. Equivalent amounts of protein were loaded to 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat milk (Bio-Rad) in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at RT, and probed with primary antibody at 1:1000 dilution in 5% BSA/TBST with 0.02% NaN3 at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed 3 times with TBST, incubated with secondary HRP-linked antibodies diluted in 1% BSA/TBST for 1 h at RT, and washed 3 more times with TBST. Bound antibodies were visualized using Clarity and Clarity Max ECL substrates (Bio-Rad), and imaged by ChemiDoc MP Imaging Systems (Bio-Rad). Antibodies used in this study were HDAC6 (Cell Signaling Technology, 7558), IKZF1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9034), IKZF3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 15103), BRD4 (Abcam, ab128874), β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-47778), anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074) and anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 7076).

In-cell ELISA

Cells were fixed by adding 125 μL 8% formaldehyde in TBS and incubated at RT for 15 minutes. After removal of fixing solution, cells were rinsed once and washed twice with TBST. Then, cells were permeabilized by adding 100 μL 0.1% Triton-X in TBS and incubated at RT for 15 minutes. After removing permeabilization solution, cells were rinsed once and washed twice with TBST. Cellular endogenous peroxidases were quenched by adding 100 μL 1% H2O2 in TBS and incubation at RT for 20 minutes. After removal of quenching solution, cells were rinsed once and washed twice with TBST. 200 μL 5% BSA/TBST with 0.02% NaN3 was added and incubated at 4°C overnight for blocking. After removing blocking buffer, 50 μL HDAC6 Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, 7558) 1:1000 diluted in 5% BSA/TBST with 0.02% NaN3 was added and incubated at RT for 2 h. Cells were rinsed once and washed three times with TBST. Anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074) 1:2000 diluted in 1% BSA/TBST was added and incubated at RT for 1 h. After antibody incubation, cells were rinsed once and washed four times with TBST. TMB substrates were premixed, added into cells and incubated in dark at RT for 20 minutes. 2N H2SO4 was added into reaction mixture and incubated at RT for 5 minutes. The optical density (OD) of each well was read at 450 nm and 570 nm by FLUOstar Omega microplate reader (BMG LABTECH). ELISA OD was obtained by subtracting the OD570 from OD450. Normalization of ELISA OD to cell number was processed by Janus Green Stain. Stop solution was removed, followed by one rinse and three washes with TBST. 50 μL 0.3% Janus Green B in TBS was added and incubated for 5 minutes. Cells were rinsed twice and wash three times with TBST, then quickly rinsed with 100 μL 140 mM NaCl solution, and exposed to 0.5 M HCl in 100 μL 140 mM NaCl. After 5-minute incubation at RT, the Janus Green OD of each well was read at 595 nm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

W.T. thanks the financial support from the University of Wisconsin- Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) through a UW2020 award and National Institutes of Health under the award number R35 GM148266 (W.T.) and R01 GM137090 (Y.X.). C.M.A.R. was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32GM008505 (Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Program). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study made use of the Medicinal Chemistry Center at UW-Madison instrumentation funded by the Lachman Institute for Pharmaceutical Development and UW Carbone Cancer Center (NIH P30 CA014520).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Supporting Information

The authors have cited additional references within the Supporting Information.[16]

References

- [1].Sakamoto KM, Kim KB, Kumagai A, Mercurio F, Crews CM, Deshaies RJ, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001, 98, 8554–8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Flanagan JJ, Qian Y, Gough SM, Andreoli M, Bookbinder M, Cadelina G, Bradley J, Rousseau E, Willard R, Pizzano J, Crews CM, Crew AP, Taylor I, Houston J, Cancer Research. 2019, 79, P5–04–18; [Google Scholar]; b) I. Foghorn Therapeutics, clinicaltrials.gov, 2023;; c) He Y, Koch R, Budamagunta V, Zhang P, Zhang X, Khan S, Thummuri D, Ortiz YT, Zhang X, Lv D, Wiegand JS, Li W, Palmer AC, Zheng G, Weinstock DM, Zhou D, J Hematol Oncol. 2020, 13, 95; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Khan S, Zhang X, Lv D, Zhang Q, He Y, Zhang P, Liu X, Thummuri D, Yuan Y, Wiegand JS, Pei J, Zhang W, Sharma A, McCurdy CR, Kuruvilla VM, Baran N, Ferrando AA, Kim Y.-m., Rogojina A, Houghton PJ, Huang G, Hromas R, Konopleva M, Zheng G, Zhou D, Nat Med. 2019, 25, 1938–1947; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Neklesa T, Snyder LB, Willard RR, Vitale N, Pizzano J, Gordon DA, Bookbinder M, Macaluso J, Dong H, Ferraro C, Wang G, Wang J, Crews CM, Houston J, Crew AP, Taylor I, Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019, 37, 259–259; [Google Scholar]; f) Robbins DW, Kelly A, Tan M, McIntosh J, Wu J, Konst Z, Kato D, Peng G, Mihalic J, Weiss D, Perez L, Tung J, Kolobova A, Borodovsky S, Rountree R, Tenn-McClellan A, Noviski M, Ye J, Basham S, Ingallinera T, McKinnell J, Karr DE, Powers J, Guiducci C, Sands A, Blood. 2020, 136, 34. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bulatov E, Ciulli A, Biochemical Journal. 2015, 467, 365–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, Ogura T, Hotta K, Imamura Y, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H, Science. 2010, 327, 1345–1350; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lopez-Girona A, Mendy D, Ito T, Miller K, Gandhi AK, Kang J, Karasawa S, Carmel G, Jackson P, Abbasian M, Mahmoudi A, Cathers B, Rychak E, Gaidarova S, Chen R, Schafer PH, Handa H, Daniel TO, Evans JF, Chopra R, Leukemia. 2012, 26, 2326–2335; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Palumbo A, Facon T, Sonneveld P, Blade J, Offidani M, Gay F, Moreau P, Waage A, Spencer A, Ludwig H, Boccadoro M, Harousseau J-L, Blood. 2008, 111, 3968–3977; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Quach H, Ritchie D, Stewart AK, Neeson P, Harrison S, Smyth MJ, Prince HM, Leukemia. 2010, 24, 22–32; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zhu YX, Braggio E, Shi C-X, Bruins LA, Schmidt JE, Van Wier S, Chang X-B, Bjorklund CC, Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Orlowski RZ, Stewart AK, Blood. 2011, 118, 4771–4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Chamberlain PP, Lopez-Girona A, Miller K, Carmel G, Pagarigan B, Chie-Leon B, Rychak E, Corral LG, Ren YJ, Wang M, Riley M, Delker SL, Ito T, Ando H, Mori T, Hirano Y, Handa H, Hakoshima T, Daniel TO, Cathers BE, Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014, 21, 803–809; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fischer ES, Böhm K, Lydeard JR, Yang H, Stadler MB, Cavadini S, Nagel J, Serluca F, Acker V, Lingaraju GM, Tichkule RB, Schebesta M, Forrester WC, Schirle M, Hassiepen U, Ottl J, Hild M, Beckwith REJ, Harper JW, Jenkins JL, Thomä NH, Nature. 2014, 512, 49–53; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Krönke J, Fink EC, Hollenbach PW, MacBeth KJ, Hurst SN, Udeshi ND, Chamberlain PP, Mani DR, Man HW, Gandhi AK, Svinkina T, Schneider RK, McConkey M, Järås M, Griffiths E, Wetzler M, Bullinger L, Cathers BE, Carr SA, Chopra R, Ebert BL, Nature. 2015, 523, 183–188; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Krönke J, Udeshi ND, Narla A, Grauman P, Hurst SN, McConkey M, Svinkina T, Heckl D, Comer E, Li X, Ciarlo C, Hartman E, Munshi N, Schenone M, Schreiber SL, Carr SA, Ebert BL, Science. 2014, 343, 301–305; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Petzold G, Fischer ES, Thomä NH, Nature. 2016, 532, 127–130; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Sievers QL, Petzold G, Bunker RD, Renneville A, Słabicki M, Liddicoat BJ, Abdulrahman W, Mikkelsen T, Ebert BL, Thomä NH, Science. 2018, 362, eaat0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Donovan KA, An J, Nowak RP, Yuan JC, Fink EC, Berry BC, Ebert BL, Fischer ES, eLife. 2018, 7, e38430; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shimizu N, Asatsuma-Okumura T, Yamamoto J, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H, Ito T, Commun Biol. 2021, 4, 1277; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yamanaka S, Murai H, Saito D, Abe G, Tokunaga E, Iwasaki T, Takahashi H, Takeda H, Suzuki T, Shibata N, Tamura K, Sawasaki T, EMBO J. 2021, 40, e105375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hagner PR, Man H-W, Fontanillo C, Wang M, Couto S, Breider M, Bjorklund C, Havens CG, Lu G, Rychak E, Raymon H, Narla RK, Barnes L, Khambatta G, Chiu H, Kosek J, Kang J, Amantangelo MD, Waldman M, Lopez-Girona A, Cai T, Pourdehnad M, Trotter M, Daniel TO, Schafer PH, Klippel A, Thakurta A, Chopra R, Gandhi AK, Blood. 2015, 126, 779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Matyskiela ME, Lu G, Ito T, Pagarigan B, Lu C-C, Miller K, Fang W, Wang N-Y, Nguyen D, Houston J, Carmel G, Tran T, Riley M, Nosaka LA, Lander GC, Gaidarova S, Xu S, Ruchelman AL, Handa H, Carmichael J, Daniel TO, Cathers BE, Lopez-Girona A, Chamberlain PP, Nature. 2016, 535, 252–257; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lu G, Surka C, Lu CC, Jang IS, Wang K, Rolfe M, Blood. 2019, 134. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bonazzi S, d’Hennezel E, Beckwith REJ, Xu L, Fazal A, Magracheva A, Ramesh R, Cernijenko A, Antonakos B, Bhang HC, Caro RG, Cobb JS, Ornelas E, Ma X, Wartchow CA, Clifton MC, Forseth RR, Fortnam BH, Lu H, Csibi A, Tullai J, Carbonneau S, Thomsen NM, Larrow J, Chie-Leon B, Hainzl D, Gu Y, Lu D, Meyer MJ, Alexander D, Kinyamu-Akunda J, Sabatos-Peyton CA, Dales NA, Zecri FJ, Jain RK, Shulok J, Wang YK, Briner K, Porter JA, Tallarico JA, Engelman JA, Dranoff G, Bradner JE, Visser M, Solomon JM, Cell Chem Biol. 2023, 30, 235–247 e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang K, Zhao Y, Nie X, Wu H, Wang B, Almodovar-Rivera CM, Xie H, Tang W, Cell Chemical Biology. 2020, 27, 866–876.e868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kazantsev A, Krasavin M, Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2022, 32, 171–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wu H, Yang K, Zhang Z, Leisten ED, Li Z, Xie H, Liu J, Smith KA, Novakova Z, Barinka C, Tang W, J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 7042–7057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Almodóvar‐Rivera CM, Zhang Z, Li J, Xie H, Zhao Y, Guo L, Mannhardt MG, Tang W, ChemBioChem. 2023, 24, e202300482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Roberts BL, Ma Z-X, Gao A, Leisten ED, Yin D, Xu W, Tang W, ACS Chem. Biol 2020, 15, 1487–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Zuber J, Shi J, Wang E, Rappaport AR, Herrmann H, Sison EA, Magoon D, Qi J, Blatt K, Wunderlich M, Taylor MJ, Johns C, Chicas A, Mulloy JC, Kogan SC, Brown P, Valent P, Bradner JE, Lowe SW, Vakoc CR, Nature. 2011, 478, 524–528; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trabucco SE, Gerstein RM, Evens AM, Bradner JE, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Zhang H, Clin Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 113–122; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chapuy B, McKeown MR, Lin CY, Monti S, Roemer MG, Qi J, Rahl PB, Sun HH, Yeda KT, Doench JG, Reichert E, Kung AL, Rodig SJ, Young RA, Shipp MA, Bradner JE, Cancer Cell. 2013, 24, 777–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Li Y, Yang J, Aguilar A, McEachern D, Przybranowski S, Liu L, Yang C-Y, Wang M, Han X, Wang S, J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 448–466; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu J, Plewe MB, Wang J, Han X, Chen, Zhang C, (Ed.: O. World Intellectual Property), Cullgen (Shanghai) , Inc., 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.