Abstract

Objective

To test the effectiveness of a telemedicine-based program in reducing asthma morbidity among children who present to the emergency department (ED) for asthma, by facilitating primary care follow-up and promoting delivery of guideline-based care.

Study Design

We included children (3–12 years) with persistent asthma who presented to the ED for asthma, were then randomly assigned to Telemedicine Enhanced Asthma Management through the Emergency Department (TEAM-ED) or enhanced Usual Care (eUC). TEAM-ED included: 1) school-based telemedicine follow-ups, completed by a primary care provider, 2) “point-of-care” prompting to promote guideline-based care, and 3) an opportunity for two additional telemedicine follow-ups. The primary outcome was the mean number of symptom-free days (SFDs) over 2 weeks at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Results

We included 373 children from 2016 through 2021 (participation rate 68%; 54% Black, 32% Hispanic, 77% public insurance, mean age: 6.4 years). Demographic characteristics and asthma severity were similar between groups at baseline. Most (91%) TEAM-ED children had ≥1 telemedicine visit; 41% completed 3 visits. At 3 months, caregivers of children in TEAM-ED reported more follow-up visits (66%vs.48%, aOR:2.07 [1.28–3.33]), preventive asthma medication actions (90%vs.79%, aOR:3.28 [1.56–6.89]), and use of a preventive medication (82%vs.69%, aOR:2.716 [1.45–5.08]), compared with eUC. There was no difference between groups in medication adherence or asthma morbidity. When only pre-pandemic data were included, there was greater improvement in SFDs over time for children in TEAM-ED versus eUC.

Conclusions

TEAM-ED significantly improved follow-up and preventive care after an ED visit for asthma. We also saw improved SFDs with pre-pandemic data. The lack of overall improvement in morbidity and adherence indicates the need for additional ongoing management support.

Trial Registration:

While well-established guidelines recommend preventive anti-inflammatory medications as part of a comprehensive management plan for children with persistent asthma to prevent emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations,(1, 2) many children who present to the ED for acute asthma care are not using any preventive asthma medication.(3) In order to provide optimal preventive care and prevent ED recidivism, guidelines recommend that children follow-up with a primary care provider (PCP) within 1–4 weeks of the ED visit.(4) The post-ED follow-up visit is an opportunity for the PCP to prescribe effective preventive asthma medications, step-up medications for children who demonstrate poor control, promote adherence, and provide education on self-management and trigger control to ultimately reduce morbidity. However, rates of follow-up after an asthma-related ED visit are low,(5–7) and preventive care is delivered inconsistently even when children are seen in follow-up,(8) resulting in preventable morbidity. In fact, ED visits and even hospitalizations may occur without a primary care provider’s knowledge.(9) Thus opportunities to optimize preventive care for asthma after an ED visit are frequently missed.

Our prior work demonstrated that a provider prompting intervention can enhance the delivery of guideline-based preventive asthma treatments at the time of a primary care office visit and ultimately reduce morbidity for historically marginalized children with asthma.(8) We have also found that telemedicine can effectively link children with persistent asthma to a provider for optimal chronic illness management.(10) Thus, the overall goal of this project was to test the effectiveness of a novel telemedicine-based program in reducing asthma morbidity among children who present to the ED for an asthma exacerbation by facilitating primary care follow-up and promoting the delivery of guideline-based preventive care.

Methods

We conducted a randomized trial of the TEAM-ED intervention versus an enhanced usual care (eUC) comparison group with children ages 3–12 years from the city of Rochester, NY (2016–2021), who presented to one of 2 emergency departments for an asthma exacerbation (Strong Memorial Hospital (SMH), Rochester General Hospital (RGH)). Children were systematically screened and eligible children were randomly assigned to either TEAM-ED or eUC. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Rochester and Rochester Regional Health.

Procedures

Screening and enrollment occurred prior to ED discharge. Children with an asthma diagnosis who presented with an acute asthma exacerbation were identified by trained recruitment staff and screened for eligibility using a brief assessment. Inclusion criteria included: 1) a prior physician-diagnosis of asthma, 2) a current emergency visit for asthma, requiring bronchodilator therapy, 3) age ≥3 and ≤12 years, and living in the Rochester metro area, 4) persistent asthma or poor asthma control, defined by national asthma guidelines.(1) Children were excluded if their caregiver was unable to speak and understand English, if they had no access to a telephone for follow-ups, if they were participating in another asthma study, and if the child had another significant medical condition that could interfere with the assessment of asthma-related measures. We also excluded children in foster care or other situations in which consent cannot be obtained from a legal guardian.

Baseline Assessment and Randomization

The baseline survey included an assessment of asthma symptoms, family and health history variables, and exposure to secondhand smoke. An asthma symptom diary was given to the caregiver for tracking asthma symptoms throughout the year and to assist with recall during the telephone follow-up assessments. Following completion of the baseline assessment, each child was randomly assigned to TEAM-ED or eUC. Randomization was stratified by enrollment site and use of a preventive asthma medication at baseline (yes/no). A permutated block design was used to ensure an equal balance of children in each group over time. The randomization scheme was developed by the Biostatistics Center, and was implemented electronically via REDCap™. All families received an educational packet including basic asthma information, smoking cessation resources, and information about the local asthma coalition. Once randomized, we sent a symptom report and notification of enrollment in the study to each child’s PCP. PCP’s of children in the eUC group also received a recommendation for guideline-based preventive actions. Screening, baseline, and randomization took approximately 30 minutes.

TEAM-ED Intervention:

For children in TEAM-ED, we scheduled a school-based telemedicine follow-up appointment that was targeted for 1-week after discharge from the ED. The visit was prepared by roaming clinical telehealth assistants (CTAs) who already worked in the schools. Training for the CTAs required 1–2 weeks of half-day sessions and demonstrated competency and sustained performance during a 2 month “internship”. The CTAs communicated with the caregiver (either by telephone or in person) and brought a small, backpack sized mobile telemedicine unit to the child’s school where they met with the child. The CTAs obtained clinical history and physical examination data (including medical images, height/weight, and breath sounds), which were either securely stored in the telemedicine system’s “virtual waiting room”, or viewed by the PCP in real time, using videoconferencing to link the child and PCP (the caregiver was also invited to meet the child at school for the visit). If the child did not return to school within 1 week of ED discharge (or during school breaks/closures), the telemedicine visit was prepared in the child’s home at a time convenient for the caregiver.

The PCP reviewed the recorded symptom information, viewed the child’s images, and listened to the breath sounds. The PCP then completed the assessment using a pre-developed template with age-appropriate guideline-based prompting based on our prior study,(8) with checklists of guideline based actions for preventive asthma care. They communicated with the child’s caregiver via teleconference (or telephone) to further discuss the child’s asthma, provide education, and develop a treatment plan. All of the children in the study had persistent or poorly controlled asthma at screening, warranting the use of a daily preventive asthma medication per guidelines. After the visit, a summary of the assessment and plan was added to the child’s medical record (via immediate upload or facsimile). The telemedicine visit modeled care that would be delivered at an outpatient asthma follow-up visit, and took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Similar to a standard asthma visit, reimbursement was submitted to the child’s health insurance (Rochester payers reimburse for telemedicine visits).

Several PCPs performed telemedicine visits as part of our current system, including 4 different practices that serve >60% of the children living in the city of Rochester. We scheduled asthma visits with the child’s primary care practice whenever possible. If there was no telemedicine provider available at the child’s practice, several providers were routinely available to perform visits. The telemedicine providers received asthma training (from Dr. Perry) prior to the beginning of each intervention year including an overview of asthma, the newest guideline recommendations, and recommendation for treatment with inhaled corticosteroids.

Following the initial telemedicine assessment, each TEAM-ED participant was eligible to receive two additional telemedicine-assisted follow-up assessments during the study period. These visits provided an opportunity for the provider to tailor each child’s asthma therapy, support asthma control, and promote long-term benefits of preventive therapy. Guideline based medication adjustments (or specialist referral, if appropriate) were recommended for children who continued to have persistent symptoms. The second telemedicine assessment was targeted for 4–6 weeks after the initial assessment, and the third 4–6 weeks after the second. After the final telemedicine-facilitated follow-up assessment we asked PCPs and families to schedule the next follow-up in the primary care office. The study team nurse reviewed records after telemedicine assessments to promote consistent delivery of guideline-based care, including appropriate prescription of preventive medications. Discrepancies were relayed back to the telemedicine provider with specific recommendations for preventive asthma care, and ultimate treatment decisions were left at the discretion of the provider.

Enhanced Usual Care (eUC) Comparison Condition:

Similar to children in TEAM-ED, children in the eUC group received a symptom assessment, a recommendation for appropriate preventive medications, and asthma education materials at the time of the ED visit. After baseline and randomization, we sent the child’s PCP a symptom report with guideline-based recommendations for preventive care and recommended a follow-up visit with the PCP. We provided systematic feedback to the family and PCP at intervals that paralleled the TEAM-ED group’s telemedicine assessments, including prompting caregivers to schedule a recommended asthma follow-up appointment and encouraging providers to adhere to care guidelines.

Participants were not masked to their group allocation; they were told that they were randomly assigned to two different ways of approaching asthma management. Because we used individual-level randomization, PCPs could have patients in either group.

Protocol Modifications Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, some modifications to the study protocol were required. We paused enrollment for 3 months, and discontinued enrollment at the RGH ED site. Due to the disruption of in-person school, we also transitioned temporarily from school-based telemedicine to home-based telemedicine via Zoom for all participants. These alterations impacted all intervention processes for 24 participants, and data collection occurred post-pandemic for 94 participants including 274 out of 1,228 follow-up time points (22%). We planned a-priori to analyze data with and without these data included.

Outcomes

Independent research staff masked to group allocation collected follow-up data by telephone at 3, 6, and 9 months after the baseline assessment, and through a final home follow-up visit at 12 months. Caregivers received a $25 gift card following the baseline, $20 after each telephone survey, and $50 at study completion. The primary outcome measure was the mean number of symptom-free days (SFDs) at the 3, 6, 9, and 12 month follow-ups.(11) At each follow-up, parents reported the number of days the child experienced no symptoms of asthma in the past 2 weeks. Caregivers were referred to their symptom diaries to help with symptom recall. Secondary measures included the number of nights with asthma symptoms and days needing rescue medications. Parents were also asked to report unscheduled (ED, acute office visits, hospitalizations) and scheduled asthma visits. We measured caregiver quality of life using the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (Juniper’s PACQLQ).(12) School absenteeism due to asthma was assessed by caregiver report.

To explore preventive asthma care, we measured the frequency of preventive asthma visits, preventive medication ‘actions’ (new prescriptions, dose adjustments, or adherence support), reported use of preventive asthma medications, and adherence to preventive medications (use in the prior 2 weeks), with a particular focus on the 3-month post-intervention follow-up assessment.

Independent Variables:

We measured standard demographics (i.e.; age, race, sex, ethnicity, insurance, and caregiver’s education, and environmental tobacco smoke exposure (measured using a validated caregiver survey(13)). The frequency and severity of all adverse events was systematically recorded during all follow-ups. Any child experiencing an acute exacerbation at the time of a home visit or follow-up call was referred immediately to their PCP.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS® 9.4 System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc. 2016. Cary, NC.). This study was designed to have adequate power to test the primary hypothesis that children in TEAM-ED will have more symptom-free days at 3, 6, 9, and 12-months compared with eUC. Based on our prior data,(10) we estimated a pooled standard deviation (SD) of SFD to be 3.5 and within-subject correlation (ICC) of 0.3. We calculated power for the intervention effect on SFD while justifying repeated outcomes assessments.(14) Accounting for a 15% attrition rate, a sample of 182 subjects per group would provide >90% power to detect a difference of 0.85 in SFD at a 2-sided 5% significance level.(15)

In accordance with the intention-to-treat principle,(16) all randomized participants were analyzed within the group to which they were assigned. We compared demographic characteristics, baseline symptoms, healthcare utilization, medications, and adherence between the study groups. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables were compared using t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test. For the primary outcome, the time-course of treatment effect on SFD during the follow-up period was evaluated using a linear mixed model accounting for repeated measures within each subject to test the intervention effect over time, where intervention was regarded as the fixed effect and subjects as the random effect.(17) Interaction effects between intervention and follow-up period were included to identify possible differences in how SFDs change over time between intervention groups. To adjust for potential confounding, demographics, baseline asthma symptoms, and factors that differentiated between groups were included in the model as covariates. Categorical outcomes such as acute asthma visits were analyzed by fitting Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models. Poisson error and log link function were specified for count data and binomial error and logit link function were used for binary outcomes. A zero-inflated model was fitted if overdispersion occurred due to extra zeros. Sandwich estimators were used to estimate standard errors. We planned a priori to conduct these analyses for participants stratified by both preventive medication use at baseline and by smoke exposure at home, and also planned to analyze pre-pandemic data separately.

Results

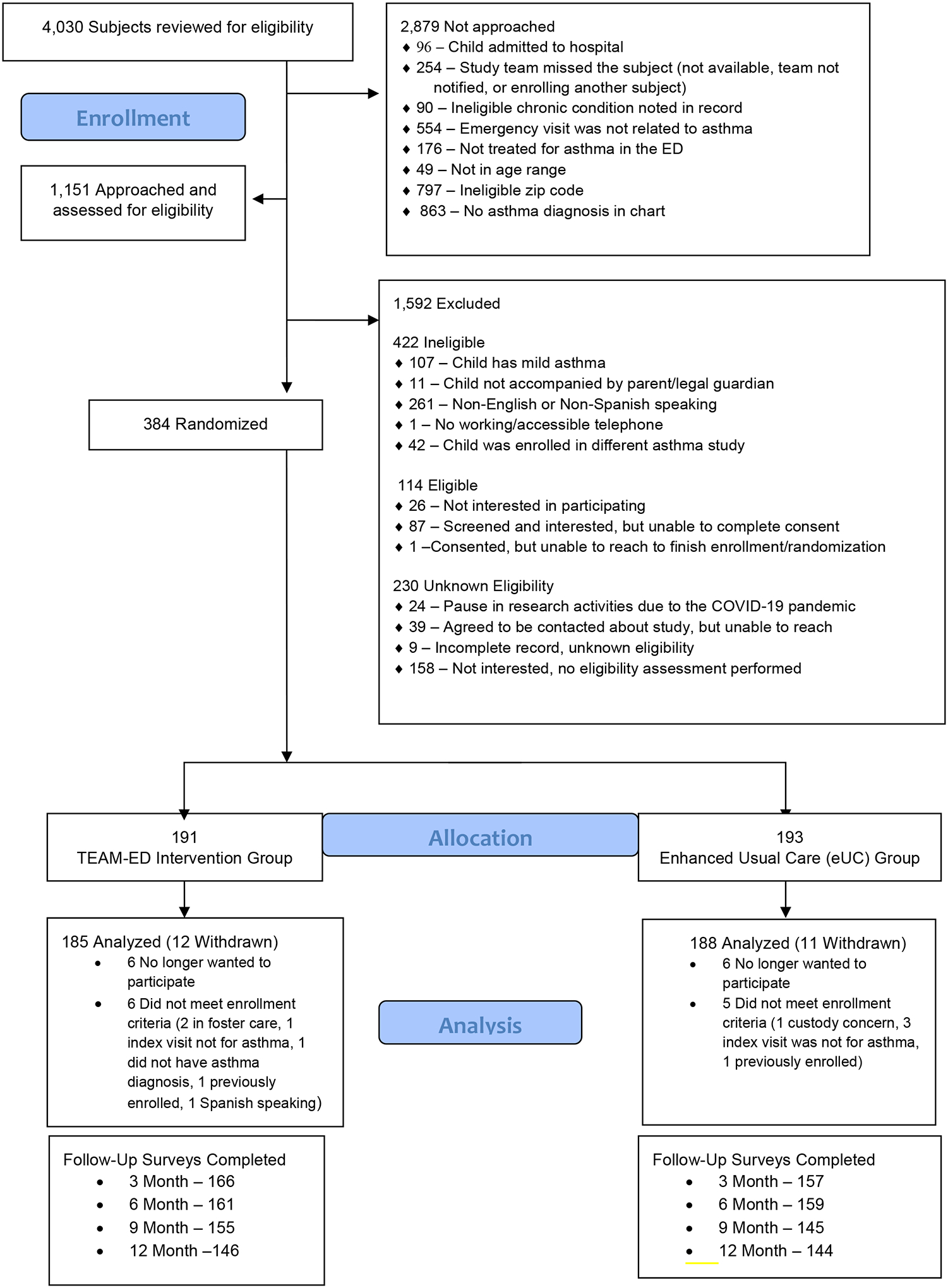

We approached 1,151 caregivers of children for potential study enrollment. Several caregivers declined eligibility assessment (n=158) and 26 caregivers of eligible children declined participation. Overall, we enrolled 384 children from the 2 ED sites (SMH-223 and RGH-161), with a 68% participation rate (Figure 1). For each enrolled participant, we obtained informed consent from caregivers and assent from children ≥7 years old, and conducted a detailed baseline assessment. For children assigned to the TEAM-ED intervention; 91% received at least one telemedicine assessment and 41% completed 3 visits. The time to the first telemedicine visit averaged 26 days. Overall, 26 providers participated in the intervention, and 46% of children received visits from a provider in their medical home.

Figure 1:

Consort Diagram

The average follow-up completion rate was 82%, and almost all (95%) of the participants had at least one follow-up for the primary outcome. There were 23 withdrawals from the study (12 TEAM-ED; 11 eUC). For 11 participants, withdrawal occurred when it was determined post-randomization that they were ineligible based on inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., foster care).

Results

Table I shows the demographic characteristics of children and caregivers in the study. Among the 373 in the study, 60% were male, 54% identified as African American or Black, 32% were Hispanic, and the mean age was 6.4 years. Approximately three-fourths (77%) of the enrolled children were covered by public insurance at the time of baseline assessment. There were no other differences in demographic characteristics between the 2 groups, except that there were more bilingual Spanish/English speakers in the TEAM-ED group (20% vs. 10%). At baseline, children had an average of 6.7 symptom-free days/2 weeks (SD =4.8), and 54% of caregivers reported their child used a preventive asthma medication in the prior 2 weeks. There were no baseline differences between groups in symptoms, healthcare utilization, or preventive medication prescription.

Table 1.

Population Demographics and Baseline Asthma Outcomes

| Variables Mean (SD), N (%) |

Overall (N=373) |

TEAM-ED (N=185) |

eUC (N=188) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Demographics | |||

| Child’s age, mean (SD) | 6.4 (2.7) | 6.27 (2.6) | 6.54 (2.8) |

| Child’s sex: Male | 224 (60%) | 111 (60%) | 113 (60%) |

| ≥1 Race / Other | 141 (38%) | 74 (40%) | 67 (35%) |

| Child’s ethnicity: Hispanic | 121 (32%) | 64 (35%) | 57 (30%) |

| Language: Bi-lingual Spanish/English speaking | 54 (14%) | 36 (20%) | 18 (10%) |

| Insurance: Public | 288 (77%) | 143 (77%) | 145 (77%) |

| Caregiver education: ≥ high school/GED | 254 (68%) | 132 (71%) | 122 (65%) |

| ≥1 Smoker(s) in the home | 163 (44%) | 86 (46%) | 77 (41%) |

| Enrollment site: Strong Memorial Hospital | 214 (57%) | 106 (57%) | 108 (57%) |

| Asthma Outcomes at Baseline | |||

| Symptom-free days in prior 2 weeks (range 0–14) | 6.7 (4.8) | 6.61 (4.9) | 6.88 (4.6) |

| Number of unscheduled acute visits for asthma in prior year (emergency, urgent care, hospitalization) | 4.59 (11.6) | 5.03 (15.0) | 4.16 (6.7) |

| Preventive asthma medication use in prior 2 weeks | 201 (54%) | 103 (56%) | 98 (52%) |

| Caregiver Quality of Life (range 1–7) | 5.07 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.2) | 5.13 (1.2) |

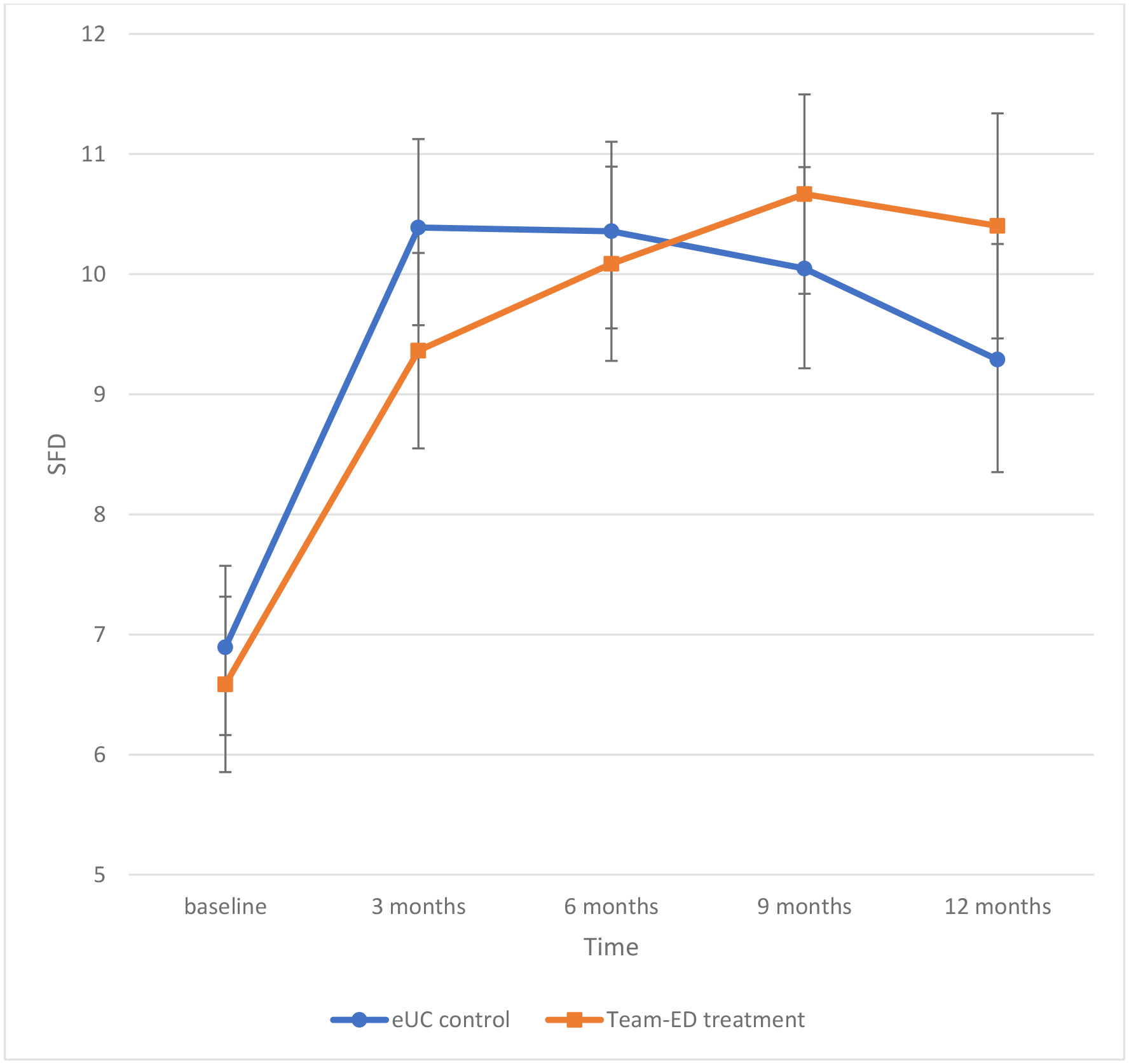

As shown in Table II, symptoms for children in both groups improved over time, and repeated measure analyses showed no difference in SFDs between groups average over the follow-up assessments (9.97 vs 10.2, difference: −0.026; 95%CI: −0.654, 0.602). We also found no differences between groups in daytime symptoms, nighttime symptoms, absenteeism due to asthma, unanticipated visits for asthma, and caregiver quality of life. The analyses stratified by preventive medication use and smoke exposure at baseline showed similar results. When considering only data collected before the pandemic, significant improvements in SFDs were seen between 3-months to 9-months, and 3-months to 12-months within the TEAM-ED group (adjusted p=.007 and p=.040, respectively), but not in the eUC comparison group. Further, there was a significant interaction effect between intervention and time (p=0.040), with the improvement in SFDs greater for the TEAM-ED group compared with eUC (Figure 2, interaction of treatment group × time, p=.040).

Table 2.

Asthma Outcomes Reported at Follow-up

| Variables Mean (SD), N (%) |

TEAM-ED | eUC | Estimate (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean # symptom-free days over 2 weeks (range 0–14) at all follow-ups | 9.97 (3.5) | 10.2 (3.5) | −.026 (−.654, .602) |

| Mean # days with symptoms over 2 weeks (range 0–14) at all follow-ups | 3.14 (3.0) | 3.12 (3.1) | −.118 (−.681, .446) |

| Mean # nights with symptoms over 2 weeks (range 0–14) at all follow-ups | 1.81 (2.4) | 1.71 (2.5) | .086 (−.369, .541) |

| Sum of missed school days due to asthma over the past year | 5.60 (7.9) | 7.20 (13.6) | .901 (.668, 1.217)* |

| ≥1 Unanticipated asthma visit during study year (emergency, urgent care, hospitalization) | 83 (46%) | 84 (48%) | .708 (.501, 1.00)^ |

| Mean caregiver quality of life score (3 and 12 months, range 1–7) | 6.14 (.96) | 6.15 (.90) | .050 (−.133, .232) |

Analysis adjusted for: age, sex, enrollment site, baseline symptoms, preventive medication use at baseline, bi-lingual language, smoke exposure, insurance, pre-pandemic

Estimate represents an adjusted rate ratio and 95% confidence intervals.

Estimate represents an adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals

Figure 2:

Symptom-Free Days over 2-weeks: Data Collected Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Figure 2 shows symptom-free days over time for children in the TEAM-ED group and children in the eUC group, including only data collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. After adjusting for covariates, significant improvement in SFDs were seen between 3-months to 9-months, and 3-months to 12-months within the TEAM-ED group (p=.007 and p=.040, respectively). There was also a significant interaction effect between intervention and time (p=0.040), with the improvement in SFD over time greater for the TEAM-ED vs. eUC group.

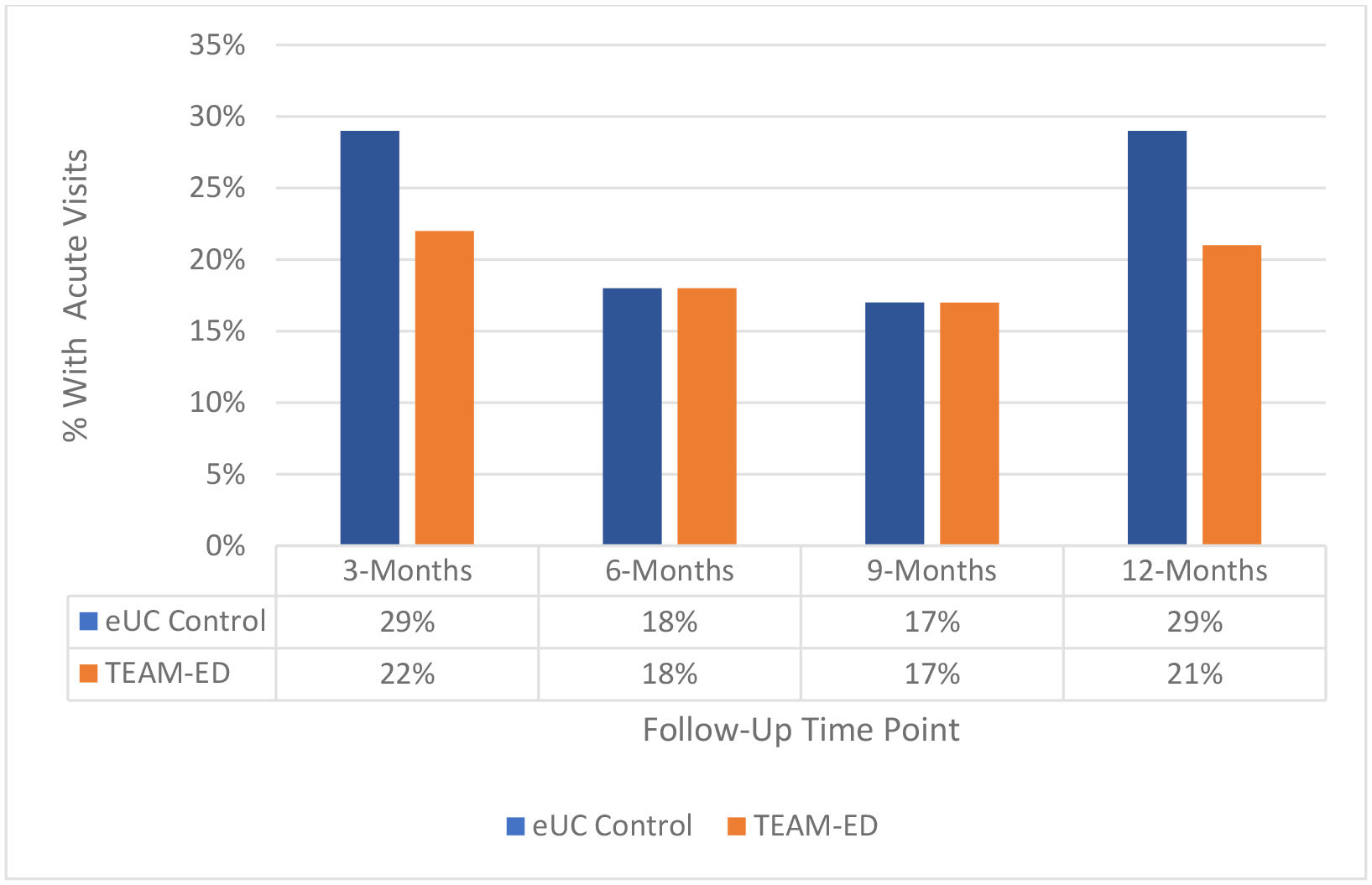

Figure 3 shows the percent of participants with acute visits for asthma at each follow-up time point. While children in the eUC group had more acute visits for asthma at the 3-month and 12-month follow-ups compared with TEAM-ED, this difference was not statistically significant. However, among the subgroup of children with no smoke exposure in the home, those in TEAM-ED had fewer acute visits compared with those in eUC (aOR: 0.61 [0.39, 0.94]). Among the subgroup with smoke exposure at home there was no difference in acute visits by group (data not shown). There were no differences in acute visits between groups when the data were stratified by preventive medication use at baseline and when only including pre-pandemic data.

Figure 3:

Unanticipated Acute Visits for Asthma Reported at Follow-up

Figure 3 shows the percent of children with ≥1 unanticipated acute visits for asthma by group reported at each follow-up time point. The number of acute visits were higher for children in the eUC group compared to children in the TEAM-ED group at the 3-month and 12-month time points; however, these findings were not statistically different.

Table III shows provider follow-up visits, preventive medication ‘actions’ (medication prescriptions, dose-adjustments, or adherence support), reported preventive asthma medication use, and adherence. At the 3-month time-point (immediately post-intervention), we found that caregivers of children in TEAM-ED reported more provider follow-up visits (66% vs. 48%, aOR 2.07 [1.28, 3.33], and were more likely to report preventive medication actions (90% vs. 79%, aOR 3.279 [1.56, 6.89]), compared with caregivers of children in eUC. Further, caregivers of children in TEAM-ED were more likely to report use of a preventive medication in prior 2 weeks (82% vs. 69%, aOR 2.72 [1.45, 5.08]). There was no difference between groups in report of ‘good adherence’ with preventive medications, indicating preventive medication use on at least 12 out of the prior 14 days (64% vs. 63%, aOR 1.08 [0.65, 1.79]).

Table 3.

Caregiver reported Asthma Care Actions and Preventive Medication Use at 3-months

| Variables N (%) | TEAM-ED (N=166) |

eUC (N=157) |

Estimate (95%CI)^ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up visit for asthma by 3-month follow-up | 108 (66%) | 76 (48%) | 2.07 (1.28, 3.33) |

| Preventive medication action (prescription, dose adjustment, or adherence support) | 147 (90%) | 124 (79%) | 3.28 (1.56, 6.89) |

| Any preventive medication use in prior 2 weeks | 134 (82%) | 109 (69%) | 2.72 (1.45, 5.08) |

| ‘Good Adherence’ with preventive medications (≥12 days out of 14 days) | 102 (64%) | 94 (62%) | 1.08 (0.65, 1.79) |

Estimate represents an adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. Analysis is adjusted for: age, sex, enrollment site, baseline symptoms, preventive medication use at baseline, bi-lingual language, smoke exposure, insurance, pre-pandemic.

Satisfaction with the program was high for all caregivers, with the majority in both groups agreeing the program was helpful to their children (93%), and they would welcome the opportunity to participate again (91%). Nearly all caregivers (97%) would recommend the program to other families of children with asthma. There were no significant adverse events for any of the children.

Discussion

This intervention was designed to reduce asthma morbidity by improving the delivery of preventive asthma care after an emergency visit for asthma. While our prior study demonstrated that provider prompting can improve preventive asthma care delivery at the time of an office visit, many children seen in the ED do not attend a primary care follow-up visit,(5–7, 18) leading to missed opportunities to improve care. We hypothesized that children receiving telemedicine asthma follow-up visits with provider prompting after an emergency visit would have more symptom-free days when compared with children receiving enhanced usual care. However, we found no difference between groups when evaluating our primary outcome in the full sample. We did find that more children receiving the TEAM-ED intervention had a follow-up visit for their asthma, had a preventive medication action to improve asthma management, and reported use of a preventive medication at the 3-month follow up. When only considering the children enrolled before the pandemic, we found greater improvement over time in symptom-free days for children in the TEAM-ED group.

The TEAM-ED intervention was designed to bridge gaps in care for children with asthma by making asthma follow-up accessible and efficient. Our existing school-based telemedicine model includes visits set up using mobile units that enable clinicians to provide assessments based on a full complement of clinically important information and to engage caregivers in education and counseling. Reimbursement for telemedicine visits, which is now standard in many states, makes it a sustainable system of care, and an efficient, cost-effective, and safe way to facilitate access to needed preventive treatments for patients.(19, 20) In fact, we have used this system of care in our prior school-based studies to facilitate asthma assessments and prescription of preventive medications to be delivered as directly observed therapy in school.(10) This current study adds to that body of work by demonstrating the ability to link children from acute to primary care for timely primary care follow up after an emergency visit, to enhance the delivery of guideline based asthma care.

Several studies have tested methods that improve the delivery of guideline-based asthma care in the office setting.(21–24) Other programs have attempted to facilitate primary care follow-up after an ED visit for asthma,(7, 25, 26) or provide specialized follow-up for patients right in the ED setting,(3) with some success. One study used telephone asthma coaching and incentives to improve attendance at asthma planning visits, but the improvements were not sustained following the intervention.(26) Another tested scheduled primary care follow-ups after an ED visit but saw no change in reutilization of emergency services.(25) A randomized controlled trial of ED interventions to improve primary care follow-up for patients with acute asthma increased follow-up rates with primary care physicians but found no difference in ED revisits or hospitalizations.(27) Similarly, a recent study using text messaging for asthma education after an emergency visit improved primary care follow-up, but not ED utilization.(28)

As we’ve found in our prior studies,(10, 29) both groups of children improved over time. This may be due to the feedback given to caregivers in the eUC group, which may have led to enhanced engagement with primary care and improved outcomes, as well as the impact of repeated contacts for follow up calls.(30) Further, when we eliminated data points collected after the COVID-19 pandemic, we discovered a difference in our primary outcome favoring the intervention group. We recognize that our intervention processes changed during the pandemic, since school-based telemedicine was not possible while children were in remote learning. The transition to home-based telemedicine visits created new challenges including difficulty scheduling and unpredictable timing of the visits. Further, our data were consistent with several studies that demonstrated a decrease in acute asthma events during the pandemic, likely due to decreased trigger exposure with masking, stay at home orders, and school closures,(31, 32) potentially making the clinical benefit of asthma interventions more difficult to detect.

Importantly, similar to our other studies,(33) the program seemed to be most effective for children not exposed to smoke in the home, with the intervention leading to reduced acute visits for asthma among this subgroup. For the children exposed to smoke, no intervention effect on asthma outcomes was detected. As we have found in our school-based studies, it appears more intensive intervention is required for these children, potentially including additional step-ups in treatment,(10) adherence support, specialist evaluation for possible biologic therapy or immunotherapy, and elimination or mitigation of smoke exposure.

In considering out study findings, children with asthma who are at high risk of poor outcomes clearly need more support over time. Enhancing access to care and prescription of guideline based preventive medications are necessary but not sufficient steps to ensure treatment is optimal. Additional support to ensure caregivers understand the treatment regimen, can fill prescriptions without difficulty, and can adhere to the daily routine is critical. Importantly, the current asthma guidelines recommend budesonide/formoterol single inhaler maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART)(1) as an option for children with moderate to severe persistent asthma, which could significantly reduce confusion about rescue versus preventive treatment. However, such therapy is not currently routinely prescribed and insurance coverage for the needed number of budesonide/formoterol inhalers may be a challenge. Importantly, while symptoms in this study improved for all of the children, many continued to suffer from asthma morbidity over time and almost one-half had repeat acute visits. Without additional support it is clear that the goals of therapy will not be met.

There are some limitations of this study that should be considered. The study was conducted in one medium-sized metro area, and therefore findings can only be generalized to similar communities. We capitalized on an existing school-based telemedicine program to implement intervention processes, which may limit the program’s reach to areas with similar programs. However, telemedicine has become much more commonly used since the pandemic, supporting the generalizability and sustainability of this model. While we performed masked outcomes assessments, masking of caregivers, children, and providers was not possible. Our primary outcome was based on caregiver report, and therefore recall bias is possible. There were challenges completing telemedicine visits for some intervention children due to difficulty scheduling, caregiver competing demands and cancellations, and school absenteeism. In addition, we provided recommendations, educational materials, and feedback for children in the eUC group, which we feel is appropriate when identifying a group of children with persistent asthma. However, this likely led to a conservative bias making differences between the two groups more difficult to detect. In addition, there may have been discrepancies between guideline-based care recommendations and provider-determined treatment plans. Lastly, we only included children of caregivers who could speak and understand English, and therefore further work is needed to address care gaps that may be compounded by language and cultural barriers.

In summary, the TEAM-ED intervention improved primary care follow-up, the provision of guideline-based preventive asthma care, and reported use of preventive asthma medication after an emergency visit for asthma. Among children enrolled prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the intervention led to improved symptom-free days. We feel this program could serve as a model for the care of children with asthma in communities that are under-resourced, however additional support measures are needed to ensure optimal treatment over time in order to meet the goals of therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HL091835). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests:

We declare no competing interests.

Ethics Committee Approval: This research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Rochester and Rochester Regional Health.

Contributor Information

Jill S. Halterman, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Maria Fagnano, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Paul Tremblay, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Arlene Butz, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Tamara T. Perry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences College of Medicine and Arkansas Children’s Research Institute.

Hongyue Wang, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Data sharing:

Upon publication, collected for the study, including de-identified individual participant data and a data dictionary defining each field in the set, will be made available to others upon request, pending approval of a signed data access agreement by the authors.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC); Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, Blake KV, Brooks EG, Bryant-Stephens T, DiMango E. 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines: A Report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. Dec;146(6):1217–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chipps BE, Murphy KR, Oppenheimer J. 2020 NAEPP Guidelines Update and GINA 2021-Asthma Care Differences, Overlap, and Challenges. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2022;10(1S):S19–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teach SJ, Crain EF, Quint DM, Hylan ML, Joseph JG. Improved asthma outcomes in a high-morbidity pediatric population: results of an emergency department-based randomized clinical trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(5):535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP). Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P, To T, Guttmann A. Follow-up care after an emergency department visit for asthma and subsequent healthcare utilization in a universal-access healthcare system. J Pediatr. 2012;161(2):208–13 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews AL, Teufel RJ 2nd, Basco WT Jr. Low rates of controller medication initiation and outpatient follow-up after emergency department visits for asthma. J Pediatr. 2012;160(2):325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorc JJ, Chew A, Allen JL, Shaw K. Beliefs and barriers to follow-up after an emergency department asthma visit: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1135–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halterman JS, Fisher S, Conn KM, Fagnano M, Lynch K, Marky A, et al. Improved preventive care for asthma: a randomized trial of clinician prompting in pediatric offices. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(10):1018–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halterman JS, Yoos HL, Kitzman H, Anson E, Sidora-Arcoleo K, McMullen A. Symptom reporting in childhood asthma: a comparison of assessment methods. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(9):766–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halterman JS, Fagnano M, Tajon RS, Tremblay P, Wang H, Butz A, et al. Effect of the School-Based Telemedicine Enhanced Asthma Management (SB-TEAM) Program on Asthma Morbidity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA pediatrics. 2018;172(3):e174938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szefler SJ. Challenges in assessing outcomes for pediatric asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(5 Suppl):S456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(1):27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matt GE, Wahlgren DR, Hovell MF, Zakarian JM, Bernert JT, Meltzer SB, et al. Measuring environmental tobacco smoke exposure in infants and young children through urine cotinine and memory-based parental reports: empirical findings and discussion. Tob Control. 1999;8(3):282–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Wu T. Sample size calculation and power analysis of time-averaged difference. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2005;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied Mixed Models in Medicine. 2nd Ed ed. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher LD, Dixon DO, Herson J, Frankowski RK, Hearron MS, Peace KE. Intention to treat in clinical trials. In: Peace KE, editor. Statistical Issues in Drug Research and Development. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1990. p. 331–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Signorini DF. Sample-Size for Poisson Regression. Biometrika. 1991;78(2):446–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bardach NS, Harder VS, McCulloch CE, Thombley R, Shaw JS, Hart VC, et al. Follow-Up After Asthma Emergency Department Visits and Its Relationship With Subsequent Asthma-Related Utilization. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(3S):S125–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConnochie K, Wood NE, Herendeen NE, Ng P, Noyes K, Wang H, et al. Acute illness care patterns change with use of telemedicine. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e989–e95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McConnochie K, Wood N, Herendeen N, ten Hoopen C, Denk L, Neuderfer J. Integrating telemedicine in urban pediatric primary care: provider perspectives and performance. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(3):280–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lozano P, Finkelstein JA, Carey VJ, Wagner EH, Inui TS, Fuhlbrigge AL, et al. A multisite randomized trial of the effects of physician education and organizational change in chronic-asthma care: health outcomes of the Pediatric Asthma Care Patient Outcomes Research Team II Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):875–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan SD, Lee TA, Blough DK, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Inui TS, et al. A multisite randomized trial of the effects of physician education and organizational change in chronic asthma care: cost-effectiveness analysis of the Pediatric Asthma Care Patient Outcomes Research Team II (PAC-PORT II). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(5):428–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butz AM, Walker J, Land CL, Vibbert C, Winkelstein M. Improving asthma communication in high-risk children. J Asthma. 2007;44(9):739–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kattan M, Crain EF, Steinbach S, Visness CM, Walter M, Stout JW, et al. A randomized clinical trial of clinician feedback to improve quality of care for inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1095–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorc JJ, Scarfone RJ, Li Y, Hong T, Harmelin M, Grunstein L, et al. Scheduled follow-up after a pediatric emergency department visit for asthma: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SR, Jaffe DM, Fisher EB Jr., Trinkaus KM, Highstein G, Strunk RC. Improving follow-up for children with asthma after an acute Emergency Department visit. J Pediatr. 2004;145(6):772–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baren JM, Boudreaux ED, Brenner BE, Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Clark S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of emergency department interventions to improve primary care follow-up for patients with acute asthma. Chest. 2006;129(2):257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coker TR, Mitchell SJ, Lowry SJ, Klein EJ, Stout JW, Brown JC, et al. Text2Breathe: Text-Message Intervention for Parent Communication and Pediatric Asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2023;23(1):123–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halterman JS, Fagnano M, Montes G, Fisher S, Tremblay P, Tajon R, et al. The school-based preventive asthma care trial: results of a pilot study. J Pediatr. 2012;161(6):1109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frey SM, Goldstein NPN, Fagnano M, Tajon RS, Halterman JS. Considering the Control Group: The Influence of Follow-Up Assessments on Asthma Symptoms. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(1):63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulrich L, Macias C, George A, Bai S, Allen E. Unexpected decline in pediatric asthma morbidity during the coronavirus pandemic. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(7):1951–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simoneau T, Greco KF, Hammond A, Nelson K, Gaffin JM. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pediatric Emergency Department Use for Asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):717–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halterman JS, Szilagyi PG, Yoos HL, Conn KM, Kaczorowski JM, Holzhauer RJ, et al. Benefits of a school-based asthma treatment program in the absence of secondhand smoke exposure: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(5):460–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon publication, collected for the study, including de-identified individual participant data and a data dictionary defining each field in the set, will be made available to others upon request, pending approval of a signed data access agreement by the authors.