Abstract

Visual assessment is currently used for primary screening or triage of screen-positive individuals in cervical cancer screening programs. Most guidelines recommend screening and triage up to at least age 65 years old. We examined cervical images from participants in three National Cancer Institute funded cervical cancer screening studies: ALTS (2,864 participants recruited between 1996-1998) in the United States (US), NHS (7,548 in 1993) in Costa Rica, and the Biopsy study (684 between 2009-2012) in the US. Specifically, we assessed the visibility of the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ), which is the susceptible zone for precancer/cancer by age, as reported by colposcopist reviewers either at examination or review of cervical images. The visibility of the SCJ declined substantially with age: by the late 40s the majority of people screened had at most partially visible SCJ. On longitudinal analysis, the change in SCJ visibility from visible to not visible was largest for participants from ages 40-44 in ALTS and 50-54 in NHS. Of note, in the Biopsy study, the live colposcopic exam resulted in significantly higher SCJ visibility as compared to review of static images (Weighted kappa 0.27 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.21, 0.33), Asymmetry chi-square P-value<0.001). Lack of SCJ visibility leads to increased difficulty in diagnosis and management of cervical precancers. Therefore, cervical cancer screening programs reliant on visual assessment might consider lowering the upper age limit for screening if there are not adequately trained personnel and equipment to evaluate and manage participants with inadequately visible SCJ.

Keywords: cervical cancer screening, squamocolumnar junction, transformation zone, visibility, age

Introduction

Cervical cancer screening programs can effectively identify and treat precancerous lesions on the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) prior to the transition to cancer (1). The SCJ is the area of the cervix that is most susceptible to precancerous lesions capable of progressing to cervical cancer when left untreated (2). Therefore, visibility of the SCJ is necessary for any visual primary screening or triage method for cervical cancer screening, including Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA), Automated Visual Evaluation (AVE), and colposcopy. Additionally, treatment by thermal ablation requires the visualization of the SCJ in order to assess the precancerous lesions (3).

The position of the SCJ changes throughout the life course by shifting inward and out of sight, and it is theorized that this transition occurs in perimenopause and menopausal states of life due to the changes in hormonal exposure (4). However, some limited evidence suggests that the SCJ moves into the endocervix earlier than perimenopause in at least some proportion of people screened (5).

Current screening guidelines recommend screening until approximately age 65 (3). However, once the SCJ has moved into the canal, VIA and visual triage of positive screened individuals may miss precancerous lesions, thus requiring more invasive procedures (4). Therefore, it is very important to know at what age group the proportion of SCJ invisibility rises to levels that would affect screening and management procedures (6–9). We assessed the association between age and SCJ visibility in participants from several studies conducted by the National Cancer Institute.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

The ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) study was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial to study immediate colposcopy, cytological follow-up, or HPV (Human Papillomavirus) triage of ASCUS (Atypical Squamous Cell of Undetermined Significance) and LSIL (Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) in the United States (10). A total of 3,488 participants with ASCUS and 1,572 participants with LSIL and no previous treatment or hysterectomy were enrolled in this study and followed every 6 months for two years between 1996 and 1998 (10).

The Guanacaste HPV Natural History Study (NHS) was a population-based study launched in 1993 of HPV and cervical neoplasia in approximately 10,000 participants from randomly selected census tracts in Guanacaste, Costa Rica (11). Guanacaste had moderately high incidence of cervical cancer at the time of study (11). At enrollment, eligible participants were given a questionnaire, interview, cervicovaginal sample collection for multiple screening methods, had a pair of cervical photographs (Cervigrams) taken, and were followed with repeated examinations for seven years.

The Biopsy Study conducted between 2009 and 2012, was an observational study of 690 colposcopy patients to study the incremental benefit of multiple biopsies at colposcopy at the Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City, United States (12). All participants were ages 18-67 years old and were referred to colposcopy because of abnormal cytological results (12).

In ALTS and NHS, the evaluation was based on an expert evaluation of Cervigram images on whether components of the Transformation Zone (TZ) were visible or not visible. We will refer to this herein as SCJ (see limitations in the discussion section). The evaluation was limited to images of technically good quality with negative Cervigram classification since the presence of lesion could bias the interpretation of SCJ visibility. In the Biopsy study, SCJ visibility was a 5-part classifier based on the percentage SCJ visible, 0%, <25%, 50%, 75%, or 100% visible. There were two independent assessments of SCJ visibility by two different expert colposcopists: one based on real-time evaluation during colposcopy (13) and the second on the digital (DSLR-Digital Single-Lens Reflex) colposcopic photographs of the cervix.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were restricted to the enrollment visit for all three studies included in the analyses. SCJ visibility was examined by age, generally grouped into 5-year age bands. The ALTS and the Biopsy studies had a much younger population as compared to NHS. However, for uniformity, the upper age limit was grouped at 65+ years for all three study analyses. In NHS and ALTS, within-participant change in SCJ visibility from the enrollment visit to the last study visit by age was also analyzed. This was not possible in the Biopsy study due to small numbers of repeat visits. For uniformity between the three studies, the static image evaluation of the Biopsy study data was used for main analysis. In the Biopsy study, the agreement in SCJ visibility assessment during live colposcopy vs. static image evaluation by independent colposcopists was also examined.

All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel and SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) (Build 1.0.0.1089).

Ethics Statement

All three study were approved by IRB and informed consent were obtained from the participants.

Results

Valid SCJ visibility and age data at the enrollment visit were available for 2,864 participants attending colposcopy in ALTS, 7,548 participants in NHS, and 684 participants in the Biopsy study. SCJ was visible for 55.8% of participants in ALTS and 60.1% of participants in NHS. In the Biopsy study, SCJ was fully visible (100%) in 81.5% of participants (Supplementary Table 1).

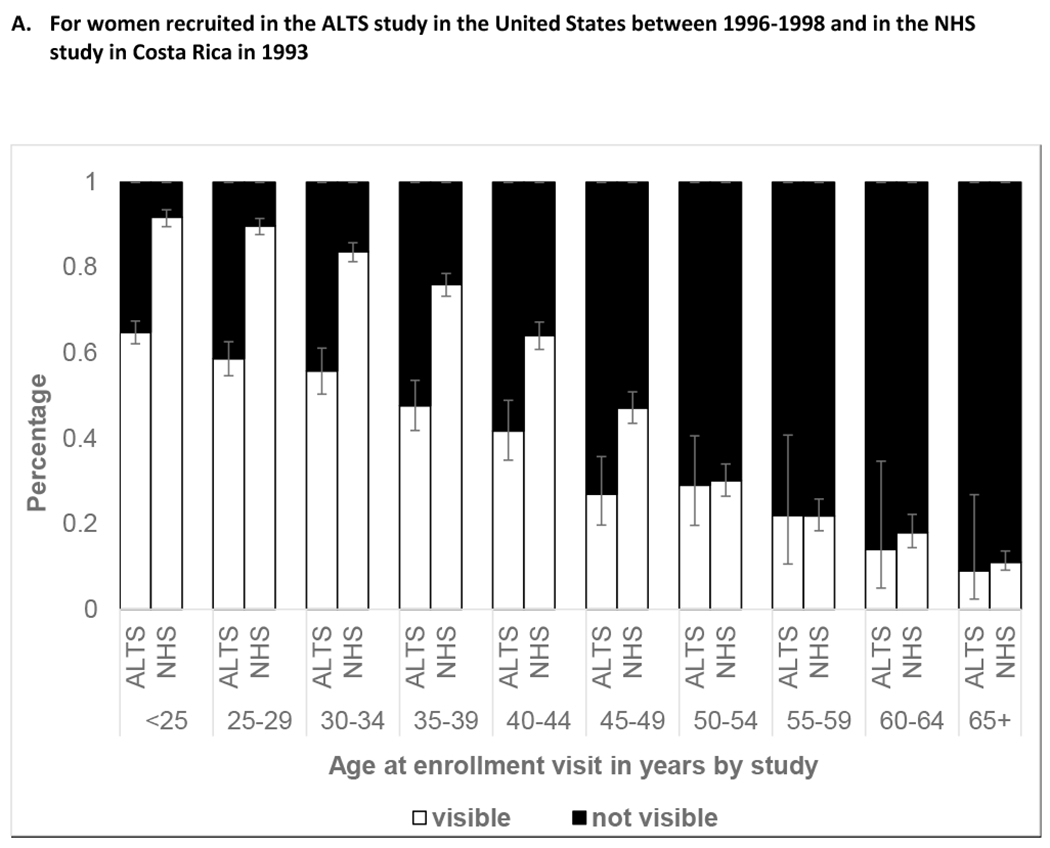

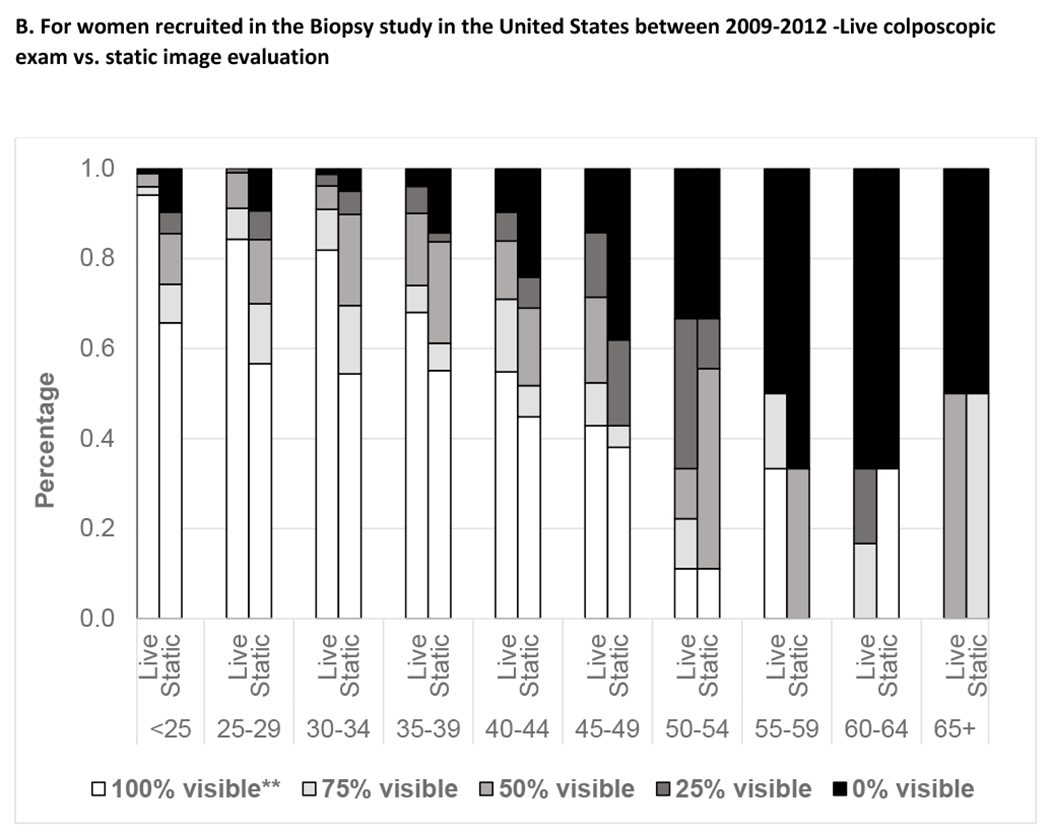

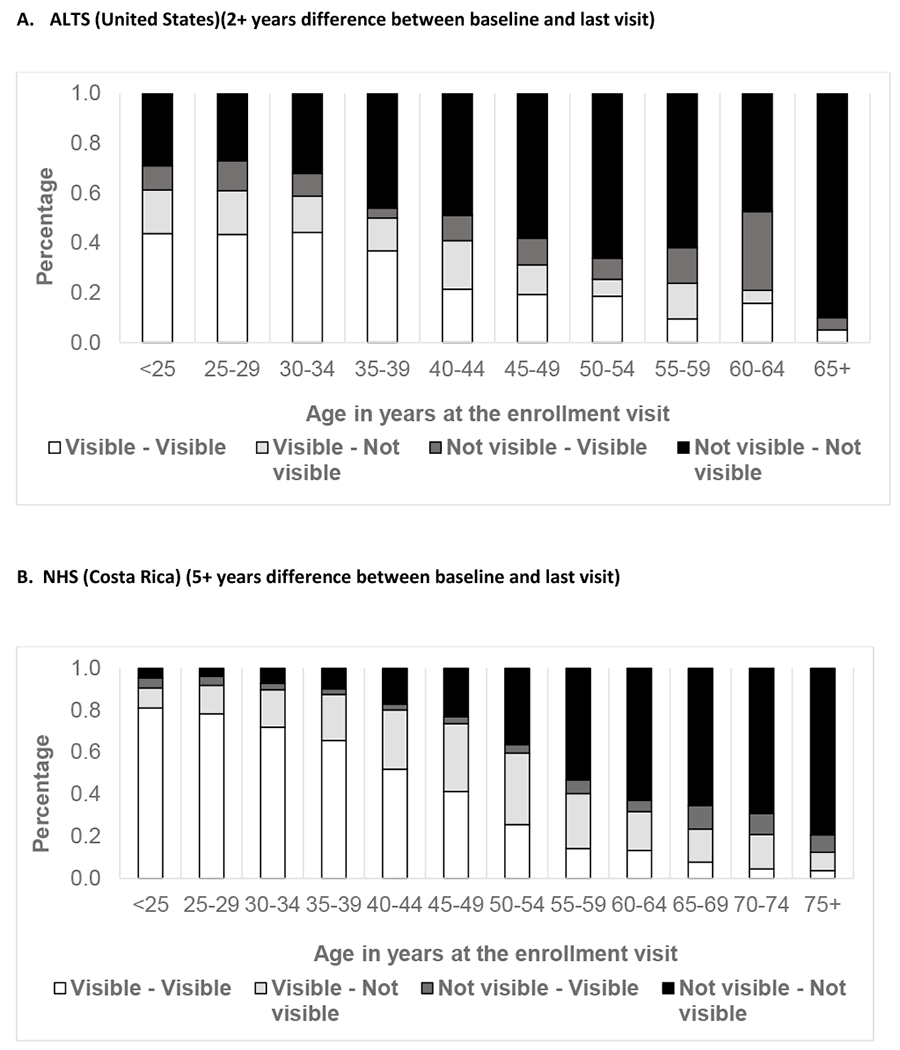

Figure 1 exhibits age at enrollment visit and SCJ visibility. Participants in all three studies had a decline in SCJ visibility by age. Analysis of age as a continuous variable within the age group of 40-49 years showed a linear decline in SCJ visibility with increasing age (data not shown). In the Biopsy study, the live colposcopy exam was associated with a significantly higher proportion of women with higher SCJ visibility than static image evaluation [Unweighted kappa 0.17 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.10,0.24); Weighted kappa 0.27 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.21, 0.33), Asymmetry chi-square P-value<0.001]. Supplementary Table 3 shows the agreement of the SCJ visibility evaluation on static digital images with the live colposcopy exam. Figure 2 depicts the change in SCJ visibility over two years in ALTS and over five years in NHS study. We found that SCJ visibility decreased between study enrollment and exit, with older participants experiencing increased loss of visibility. There were differences in the changes experienced in the SCJ visibility in women in the ALTS and the NHS. The proportion of women with change from visible to not visible over two years was largest for participants from ages 40-44 at enrollment in ALTS (19.1%), while in the NHS, this change was more marked for women aged 45-49 (32.2%) and 50-54 (33.9%) at enrolment who were 50 to 60 at exit.

Figure 1. SCJ Visibility by Age among women recruited across three study sites.

*Error bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals for percentage of participants with visible SCJ, when image evaluators were not given a choice of partially visible

***Number of participants in each category is available in Supplementary Table 2

**95% Confidence Intervals for the proportion of participants with 100% visible SCJ on live evaluation were as follows: in age group <25 (90.6, 96.3), 25-29 (78.6, 88.6), 30-34 (71.8, 88.9), 35-39 (54.2, 79.2), 40-44 (37.8, 70.8), 45-49 (24.5, 63.5), 50-54 (2.0, 43.5), 55-59 (9.7, 70.0), 60-64 (0, 39.0), 65+ (0, 65.8); 95% Confidence Intervals for the proportion of participants with 100% visible SCJ on static digital image evaluation were as follows: in age group <25 (59.9, 71.2), 25-29 (49.8, 63.3), 30-34 (43.5, 64.9), 35-39 (41.3, 68.1), 40-44 (28.4, 62.4), 45-49 (20.7, 59.1), 50-54 (2.0, 43.5), 55-59 (0, 39.0), 60-64 (9.7, 70.0), 65+ (0, 65.8)

**** Number of participants in each category is available in Supplementary Table 2

Figure 2A.

Change in SCJ visibility between baseline and last visits for women at two study sites

Analyses were also done on parity, smoking, BMI (Body Mass Index), vaginal PH (Potential of Hydrogen), and contraceptive method when data were available for each study. Parous women (vs. nulliparous), current smoker (vs. non-smoker), hormonal contraceptive user (vs. not user) were found to have higher SCJ visibility, with some statistically significant difference, particularly at premenopausal age (Supplementary Figure 1). Using the NHS and ALTS datasets we also looked at percent HPV positivity by SCJ visibility across all age categories and found no significant difference (data not shown).

Discussion

Using three datasets from the NHS, ALTS, and Biopsy studies, SCJ visibility decreases markedly with age. Cofactors, including recent hormonal contraception use, BMI, smoking, and parity, had limited clinically significant differences on SCJ visibility after adjustment by age despite some statistically significant differences. Age was the main clinically significant factor determining SCJ visibility on a population level. An analysis using dataset from Peru based on SCJ visibility assessment by midwives also found very similar results (14).

The reasons for an overall lower proportion of women changing from visible to not visible at any age in ALTS compared to NHS is not entirely clear but could be explained by the fact that for each age group, ALTS had a higher proportion of women with no visible SCJ than NHS. This, along with the relatively younger age for change in visible to not visible SCJ in ALTS compared to NHS, could be explained by higher nulliparity and smoking in ALTS. The possibility of difference in the reading of partially visible SCJ as visible versus not visible between NHS and ALTS by different expert reviewers could also not be excluded. It is also mentionable that in both the studies across age group, there were a small proportion (~5-10%) of women with changes in SCJ visibility from not visible to visible, except in ALTS for age 60-64 there were 31% women with such non-intuitive change. However, the small numbers at upper ages and known subjectivity in assessing SCJ visibility (21) limit any meaningful interpretation. Though, some clinicians do conform to the possibility of such change even biologically, particularly after applying topical estrogen (22).

Based on the Biopsy study dataset, it was reassuring to see that live colposcopy examination had higher SCJ visibility as compared to static image evaluation. In contrast, in a study in Nigeria, it was found that the image review and the live colposcopy examination showed a similar trend of increasing partial visibility (data not shown) (5). It is very important to distinguish visibility assessed on images versus real life. Images underestimate the visibility in real life which allows for manipulation of the cervix that might not be capturable even on multiple static images. For evaluating an image-based application like automated visual evaluation (AVE), the image-based estimates of SCJ visibility are relevant since the percentage of women with not fully visible SCJ on static images is a surrogate for the percentage of women with valid images for accurate AVE diagnostic assessment (15). In contrast, the percentage of incomplete visualization in the live colposcopy examination could be considered the “ceiling” of what one could achieve with one or multiple static images or even live visual examination; one cannot get better than that ceiling with any visual evaluation method.

Most guidelines recommend screening up to age 65 years in previously screened normal patients and beyond in those who were under surveillance due to previous abnormal results. For example, UK (United Kingdom) National Health Service recommends screening until age 64 (16), the European Union recommends up to age 60 or 65 (17), the USPTF (United States Preventive Services Taskforce) recommends screening up to age 65 (18), and the WHO (World Health Organization) recommends screening until age 65 when resources are available (3). Screening programs based on screen-treat or screen-triage-treat must understand and address the impacts associated with half of people undergoing cervical screening over the age of 45 that do not have a fully visible SCJ even during live assessment. These people would need more expensive and complex screening and diagnostic procedures, such as cytology and/or endocervical sampling (ECC) and associated resources (i.e., cytopathologists, histopathology laboratory). Endocervical sampling is known to have high percentage of insufficient sampling, even when collected by providers and handled in laboratories in experienced settings with organized cervical screening programs (9). Furthermore, more invasive treatment modes with higher associated risk of complications and more resource utilization will be required as treatment with thermal ablation is not possible when the SCJ is not completely visible (3). LLETZ (Large Loop Excision of the Transformation Zone) and cone excision have higher risks, such as bleeding (19). Referral to LLETZ is even more consequential in resource-limited settings where there is lack of equipments and trained health providers.

Lastly, newer cervical cancer screening technologies based on artificial intelligence, like AVE, like all other visual methods (i.e., VIA, colposcopy) also rely on a visible SCJ on a static digital image to avoid false negative test results (15). Therefore, limiting the use of AVE for diagnosis in women up to age 45 or 49 is recommended. An effort to develop a second AVE algorithm to assist with evaluating SCJ is also underway to help minimize the use of AVE in women with fully visible SCJ only (20).

Limitations

It is important to point out here an area of confusion about the terminology (i.e., SCJ, TZ, adequacy of colposcopy), differences of opinion between the US and the international nomenclature, and evolution in thinking. The SCJ is a circular line at the junction of squamous and columnar epithelium. The TZ is a cylindrical plane of metaplastic squamous epithelium between old and new SCJ and is the area susceptible to HPV-induced carcinogenesis. The distal end of the TZ (i.e., the old SCJ) cannot be assessed visually. Hence, the assessment of the visibility of the proximal end of the TZ (i.e., the current SCJ) is used as an inexact approximation of the visibility of TZ which is the region of interest (ROI). In NHS and ALTs, visibility assessment was based only on static images and was only recorded as to whether the components of the TZ are visible or not visible. The question asked was ambiguous and it is not clear which way the partial visibility was categorized. For the Biopsy study on the other hand the question was: “% SCJ visualized: 0, 25, 50, 75, 100%”. Because of this ambiguity, we cannot be sure what absolute % of the ROI is visible. However, because of the strong association, we can be sure that regardless of definition, visibility declines such that the majority of women had substantially incomplete visibility by age 50. Screening programs that include older women will have trouble visualizing the area of concern among HPV-positive women and treating them simply without morbidity.

Conclusions

SCJ visibility declines with age, with upwards of at least 50% of people not having a fully visible SCJ by the age of 45 years old. Individual-level cofactors, such as contraceptive use, BMI, or parity, are not as clinically important as age itself for SCJ visibility. Live colposcopic exam has higher SCJ visibility as compared to static image evaluation. Regardless, cervical cancer screening programs dependent on visual evaluation, either live or image-based, might need to consider reducing the upper age limit for screening because of the increased challenges in treatment and management of screen-positive patients after approximately age 45. Cost-effectiveness analysis in this realm is increasingly warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the support from IMS, Inc., MD for data organization.

Funding

This research was funded by the NCI Cancer MoonshotSM and NIH intramural research program.

Abbreviations

- ALTS

ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study

- ASCUS

Atypical Squamous Cell of Undetermined Significance

- AVE

Automated Visual Evaluation

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CIN

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- DSLR

Digital Single-Lens Reflex

- HPV

Human Papillomavirus

- HR

High-risk

- IRB

Institutional Review Boards

- LSIL

Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- NHS

Natural History Study

- PH

Potential of Hydrogen

- SCJ

Squamocolumnar Junction

- TZ

Transformation Zone

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- UK

United Kingdom

- USPSTF

United States Preventive Services Taskforce

- VIA

Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Credit Author Statement

The work reported in the paper has been performed by the authors, unless clearly specified in the text. Conceptualization KD, NH, MS, SDS, JJ; methodology KD, NH, JJ, MS, SDS; formal analysis KD, NH, DE, BB; ALTS field investigation MS; NHS field investigation ACR; Biopsy study field investigation NW, data curation, KD, BB; writing—original draft preparation KD, NH; writing—review and editing, all. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Vol. 370, Lancet. Elsevier B.V.; 2007. p. 890–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doorbar J, Griffin H. Refining our understanding of cervical neoplasia and its cellular origins. Vol. 7, Papillomavirus Research. Elsevier B.V.; 2019. p. 176–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical precancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention, Second edition [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2021. [cited 2021 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prendiville W, Sankaranarayanan R. Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer. Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2023 Feb 2];85–99. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568370/ [PubMed]

- 5.Desai KT, Ajenifuja KO, Banjo A, Adepiti CA, Novetsky A, Sebag C, et al. Design and feasibility of a novel program of cervical screening in Nigeria: self-sampled HPV testing paired with visual triage. Infect Agent Cancer. 2020;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Ueda Y, Kakuda M, Kubota S, Matsuzaki S, Iwamiya T, et al. Predictors for recurrent/persistent high-grade intraepithelial lesions and cervical stenosis after therapeutic conization: a retrospective analysis of 522 cases. Int J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2017. Oct 1 [cited 2023 Feb 2];22(5):921–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28451844/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baasland I, Hagen B, Vogt C, Valla M, Romundstad PR. Colposcopy and additive diagnostic value of biopsies from colposcopy-negative areas to detect cervical dysplasia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand [Internet]. 2016. Nov 1 [cited 2023 Feb 2];95(11):1258–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27564523/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cremer M, Conlisk E, Maza M, Bullard K, Peralta E, Siedhoff M, et al. Adequacy of visual inspection with acetic acid in women of advancing age. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics [Internet]. 2011. Apr 1 [cited 2023 Feb 2];113(1):68–71. Available from: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai KT, Ajenifuja KO, Banjo A, Adepiti AC, Novetsky AP, Sebag C, et al. Design and feasibility of a novel program of cervical screening in Nigeria: self-sampled HPV testing paired with visual triage. Infectious Agents and Cancer (submitted). 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiffman M, Adrianza ME. ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study: Design, methods and characteristics of trial participants. Acta Cytol [Internet]. 2000. [cited 2021 Jun 21];44(5):726–42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11015972/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrero R, Schiffman MH, Bratti C, Hildesheim A, Balmaceda I, Sherman ME, et al. Design and methods of a population-based natural history study of cervical neoplasia in a rural province of Costa Rica: The Guanacaste Project. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica/Pan American Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 1997. [cited 2021 Feb 3];1(6):411–25. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9180057/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, Smith KM, Zuna RE, Mathews C, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. Journal of Clinical Oncology [Internet]. 2015. Jan 1 [cited 2021 Feb 5];33(1):83–9. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4268255/?report=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu AH, Gold MA, Schiffman M, Smith KM, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, et al. Comparison of Colposcopic Impression Based on Live Colposcopy and Evaluation of Static Digital Images [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://links.lww. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez-Ampuero C, Hansen N, Larraondo MA, Taipe-Quico R, Cerna AJ, Desai KT, et al. Squamocolumnar Junction Visibility among Cervical Cancer Screening Population in Peru Might Influence Upper Age For Screening Programs. Preventive Medicine (Submitted). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai K, Befano B, Xue Z, Kelly H, Campos NG, Egemen D, et al. The development of “Automated Visual Evaluation” for cervical cancer screening: The promise and challenges in adapting deeplearning for clinical testing (Accepted). Int J Cancer. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cervical screening: programme overview - GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/cervical-screening-programme-overview

- 17.von Karsa L, Arbyn M, de Vuyst H, Dillner J, Dillner L, Franceschi S, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Summary of the supplements on HPV screening and vaccination. Papillomavirus Research. 2015. Dec;1:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2012. Jun 19 [cited 2023 Feb 2];156(12):880–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22711081/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyrgiou M, Athanasiou A, Kalliala IEJ, Paraskevaidi M, Mitra A, Martin-Hirsch PPL, et al. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for cervical intraepithelial lesions and early invasive disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017. Nov 2 [cited 2023 Feb 2];11(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29095502/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiffman M, Desai K. Automated Visual Evaluation (AVE) for cervical cancer screening [Internet]. HPV world. 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.hpvworld.com/articles/automated-visual-evaluation-for-cervical-cancer-screening/

- 21.Benkortbi K, Catarino R, Wisniak A, Kenfack B, Tincho Foguem E, Venegas G, Mulindi M, Horo A, Jeronimo J, Vassilakos P, & Petignat P (2023). Inter- and intra-observer agreement in the assessment of the cervical transformation zone (TZ) by visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and its implications for a screen and treat approach: a reliability study. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1). 10.1186/s12905-022-02131-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards A, & Dalrymple C (2015). Abnormal cervicovaginal cytology, unsatisfactory colposcopy and the use of vaginal estrogen cream: An observational study of clinical outcomes for women in low estrogen states. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 41(3), 440–444. 10.1111/jog.12545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.