Abstract

T cell receptor engineered T cell (TCR T) therapies have shown recent efficacy against certain types of solid metastatic cancers. However, to extend TCR T therapies to treat more patients across additional cancer types, new TCRs recognizing cancer-specific antigen targets are needed. Driver mutations in AKT1, ESR1, PIK3CA, and TP53 are common in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) and if immunogenic could serve as ideal tumor-specific targets for T cell receptor engineered T cell (TCR T) therapy to treat this disease. Through IFN-γ ELISpot screening of in vitro expanded neopeptide-stimulated T cell lines from healthy donors and MBC patients, we identified reactivity towards 11/13 of the mutations. To identify neopeptide-specific TCRs, we then performed single-cell RNA sequencing of one of the T cell lines following neopeptide stimulation. Here, we identified an ESR1 Y537S specific T cell clone, clonotype 16, and an ESR1 Y537S/D538G dual-specific T cell clone, clonotype 21, which were HLA-B*40:02 and HLA-C*01:02 restricted, respectively. TCR Ts expressing these TCRs recognized and killed target cells pulsed with ESR1 neopeptides with minimal activity against ESR1 WT peptide. However, these TCRs failed to recognize target cells expressing endogenous mutant ESR1. To investigate the basis of this lack of recognition we performed immunopeptidomics analysis of a mutant-overexpressing lymphoblastoid cell line, and found that the ESR1 Y537S neopeptide was not endogenously processed, despite binding to HLA-B*40:02 when exogenously pulsed onto the target cell. These results indicate that expansion of naïve T cells with pulsed minimal peptides may lead to expansion of clonotypes that recognize peptides that are not processed intracellularly, and highlights the importance of using methods that selectively

Keywords: T cell receptor engineered T cell, TCR T, immunotherapy, breast cancer, neoantigens

INTRODUCTION:

T cell receptor engineered T cell (TCR T) therapy has recently emerged as a promising therapeutic modality for solid cancers following clinical trials demonstrating their safety and efficacy against some types of metastatic solid cancers.1-5 A critical factor mediating the efficacy of TCR T therapies against solid cancers is the need for TCR antigen targets that are exclusively expressed by cancer cells. TCR T trials that have demonstrated efficacy to date have targeted only a handful of well-characterized cancer-germline or viral antigens.6 To extend the benefits of TCR T therapy to more patients across different cancer subtypes, there is an urgent need to identify novel TCRs that target antigens that are selectively expressed by the tumor, in order to induce potent and safe antitumor effects.

Neoantigens, which arise from somatic mutations exclusively present in malignant cells, represent such cancer-restricted targets. A relatively small subset of mutations known as ‘driver mutations’ have been demonstrated to directly enhance cell fitness and tumorigenesis, and are thus more likely to be homogeneously expressed across metastatic tumors and shared across patients within a particular cancer subtype.7-10 Thus, neoantigens that result from common driver mutations may provide safe and effective target antigens for TCR T therapy.6 However, few TCRs recognizing mutations within the 299 annotated driver genes8 have been discovered to date.

Breast cancer (BC) is responsible for the greatest number of cancer cases and cancer deaths in women world-wide.11 Despite significant advances in the treatment of metastatic BC (MBC) leading to prolonged survival of patients, MBC is still considered an incurable disease.12 There is thus urgent need for new treatment options for MBC patients. In MBC, missense driver mutations in AKT1, ESR1, PIK3CA, and TP53 are common13-18 and if immunogenic, could serve as targets for TCR T therapy of MBC. In this study, we aimed to discover TCRs with specificity for these common MBC mutations for use in TCR T therapy of MBC.

An early, critical step in many TCR discovery efforts is the selective expansion and enrichment of T cells that have a desired antigen specificity. This is often achieved by stimulating T cells with the antigen of interest, in the form of autologous tumor tissue, dendritic cells (DCs) edited to express the antigen of interest, or commonly, with DCs exogenously loaded with peptides of interest.6 However, the effect that these stimulation methods have on the functional outcome of identified TCRs has not been widely reported.

In this study, we expanded peripheral blood T cells from healthy donors and MBC patients through stimulation with DCs loaded with neopeptides derived from thirteen common missense mutations in AKT1, ESR1, PIK3CA, and TP53. ELISpot analysis of the expanded lines revealed the successful expansion of T cells with neopeptide specificity towards 10/13 mutations targeted. We further isolated and cloned two TCRs that were specific for ESR1 Y537S (HLA-B*40:01-restricted) or dual specific for ESR1 Y537S and D538G (HLA-C*01:02-restricted). However, we identified that while these TCRs mediated selective and efficient killing of ESR1 neopeptide-loaded targets, they failed to recognize target cells that expressed their cognate ESR1 mutation. Through immunopeptidomics analysis, we identified that the reason for the discrepancy between TCR recognition of ESR1 Y537S neopeptide-loaded vs mutant-expressing targets was due to a lack of endogenous processing of the cognate ESR1 Y537S neopeptide, despite the ability for this peptide to bind HLA and elicit a potent T cells response when exogenously loaded.

Our results demonstrate a potential consequence of using peptides as a means of selectively expanding T cells for TCR discovery, and highlights the importance of considering antigen processing upfront when identifying antigen targets and selecting appropriate methods for TCR discovery.

RESULTS:

Expansion of T cells with specificity for neopeptides derived from common MBC mutations

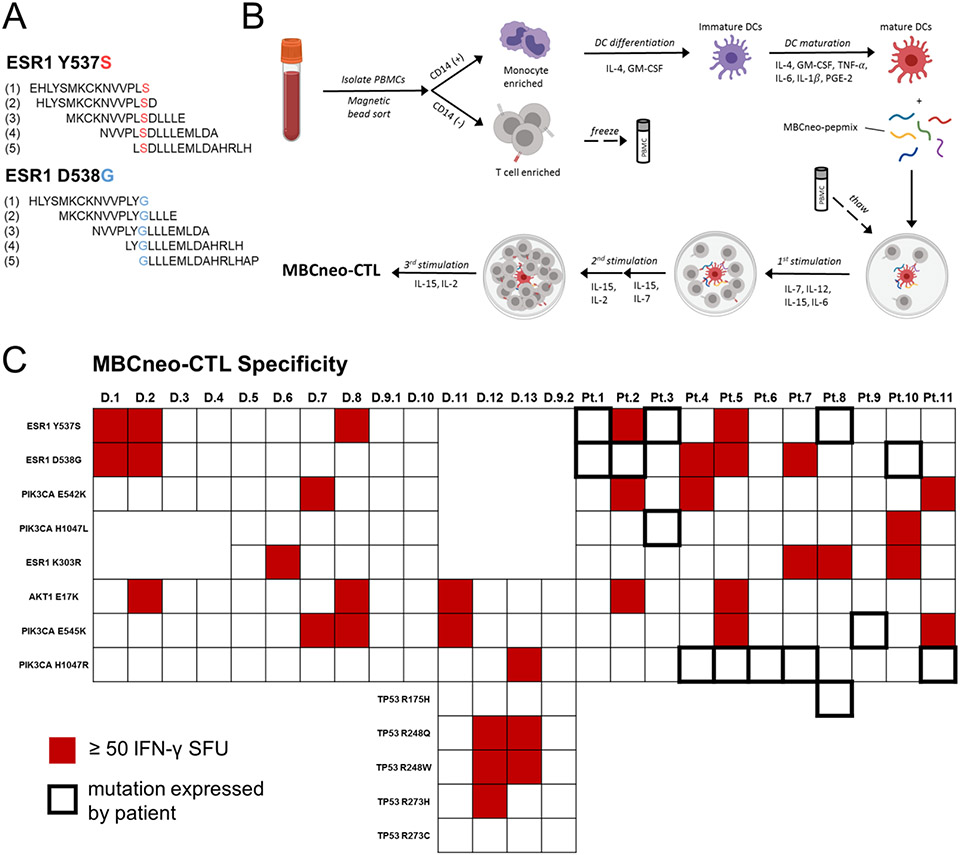

To determine whether we could generate T cell responses against neopeptides derived from common MBC driver mutations, we generated a library of overlapping 15-mer peptides that covered thirteen missense mutations in AKT1, ESR1, PIK3CA, and TP53 (Figure 1a), referred to as the MBCneo-pepmix. We used our group’s well-established protocol to expand antigen-specific T cells from peripheral blood.19 Briefly, we isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors and MBC patients whose tumors expressed at least one of the targeted mutations. We then generated monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DCs) and performed 2-3 rounds of T cell stimulations with MBCneo-pepmix pulsed DCs, with resulting expanded T cells referred to as MBCneo-CTL lines. To determine which of the stimulating peptides the MBCneo-CTL lines recognized, we performed IFN-γ ELISpot assays by stimulation with each individual peptide component of the MBCneo-pepmix. We observed T cell responses towards at least one neopeptide in 8/14 (57%) of healthy donor-derived lines and in 7/11 (64%) of MBC patient-derived lines (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). For each neopeptide that elicited a response by an MBCneo-CTL line, we also tested the line’s response towards the corresponding WT peptide. In most instances the MBCneo-CTL lines displayed minimal to no reactivity towards corresponding WT peptides, but we did observe several instances in which the MBCneo-CTLs failed to discern a neopeptide from a corresponding WT peptide (Supplementary Fig. 2). While we observed neopeptide reactivity in seven of the MBC patient-derived lines, unexpectedly none of these responses were directed towards the mutation(s) detected in the patients’ own tumors (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). These results demonstrated that many of the shared MBC neopeptides can be recognized by T cells.

Figure 1: Expansion of MBC neoantigen specific T cells from peripheral blood of healthy donors and MBC patients.

(A) Examples of overlapping 15 amino acid neopeptides that comprise the MBCneo-pepmix. (B) Cartoon illustrating the process by which peripheral blood T cells were stimulated with MBCneo-pepmix pulsed DCs to generate expanded MBCneo-CTL lines. (C) Heatmap displaying specificity of the MBCneo-CTL lines towards neopeptides derived from the target mutations as determined by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Lines were considered reactive for a target mutation, indicated with red shading, if they produced ≥ 50 IFN-γ SFU/2x105 cells following stimulation with at least one of the overlapping 15-mer peptides containing that mutation. MBCneo-CTL lines were generated from 13 healthy donors and 11 HR+MBC patients. Patient tumors that expressed the targeted mutations are indicated by bolded borders in the heatmap.

Isolation of TCRs recognizing ESR1 hotspot mutations

The donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line was highly specific for two 15-mer neopeptides derived from ESR1 Y537S (NVVPLSDLLLEMLDA) and D538G (NVVPLYGLLLEMLDA), with minimal reactivity towards the corresponding ESR1 WT peptide (NVVPLYDLLLEMLDA) (Fig. 1c and Fig. 2a). To determine whether this neopeptide response was mediated by CD8 or CD4 T cells, we performed intracellular cytokine staining following stimulation with ESR1 Y537S or D538G neopeptides or with an irrelevant peptide. We observed increased T cell production of IFN-γ and TNF-α in CD8+ T cells stimulated with ESR1 Y537S or D538G, but not irrelevant peptide, indicating HLA-class I restricted TCR recognition (Fig. 2b). To determine the cytotoxic potential of the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line, we pulsed autologous phytohemagglutinin-L (PHA) stimulated T cells (PHA blasts) with either ESR1 WT, Y537S, or D538G peptide and then performed a Cr-51 release cytotoxicity assay. The donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line killed PHA blasts pulsed with ESR1 Y537S or D538G neopeptide (64.8% and 55.8% cytotoxicity at a 40:1 E:T ratio, respectively), with minimal killing of ESR1 WT pulsed targets (13.4% specific lysis) (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2: Isolation and characterization of ESR1 mutant specific TCRs.

(A) Specificity of the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line for ERS1Y537S and ESR1D538G neopeptides and the corresponding ESR1WT peptide as determined by IFN-γ ELISpot. (B) Intracellular cytokine staining assay to determine HLA class I or II restricted response of the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line towards ESR1Y537S and ESR1D538G neopeptides. T cells were stimulated with or without ESR1Y537S or ESR1D538G neopeptides in the presence of monesin and brefeldin for 12 hours, after which the cells were fixed and permeabilized and stained for extracellular makers CD3, CD4, and CD8, and intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α. (C) In vitro cytotoxicity of the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line against autologous PHA blasts pulsed with ESR1Y537S or ESR1D538G neopeptide or corresponding WT peptide in a six hour Cr-51 release assay. (D) Cartoon illustrating scRNAseq based method to identify ESR1 neopeptide-specific TCRs from the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line. T cells were stimulated with ESR1WT, ESR1Y537S, or ESR1D538G for 12 hours. Each condition was then stained with oligo-tagged antibodies, pooled, and submitted for scRNAseq. (E) Following hashtag deconvolution neopeptide specific T cells were identified by expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Clones 16 and 21 were identified among the ESR1 neopeptide responsive clones and are highlighted. The clonotype 16 and 21 TCR α/β variable regions were obtained and cloned into the SFG TCR retroviral vector. (F) Construct design for SFG retrovirus expression of TCRs. TCR α/β variable regions were conjugated to murine TCR α/β constant regions with mutations conferring an additional disulfide bond and stabilizing hydrophobic residues in the transmembrane region of the TCRα chain. (G-H) Transduction efficiency of activated T cells transduced with the clonotype 16 (G) or 21 (H) TCRs as determined by flow cytometry detection of mTCRβ. (I) Specificity of NT or clonotype 16 TCR Ts for ESR1Y537S neopeptide or corresponding WT peptide as determined by IFN-γ ELISpot. (J) Specificity of clonotype 16 TCR Ts towards decreasing concentrations of ESR1Y537S neopeptide as determined by IFN-γ ELISpot (K) Specificity of clonotype 21 TCR Ts for ESR1Y537S or ESR1D58G neopeptide or corresponding WT peptide as determined by IFN-γ ELISpot. (L) In vitro cytotoxicity of NT or clonotype 21 TCR Ts against autologous PHA blasts pulsed with ESR1Y537S or ESR1D538G neopeptide or corresponding WT peptide in a six hour Cr-51 release assay. (M) Determination of the HLA restriction of the clonotype 16 TCR. Allogeneic OKT3 blasts were transduced with individual donor 1 HLA class I alleles, pulsed with ESR1Y537S-neopeptide, and used as targets for clonotype 16 TCR Ts in an IFN-γ ELISpot. (N) Determination of the HLA restriction of the clonotype 21 TCR. Allogeneic OKT3 blasts were transduced with individual donor 1 HLA class I alleles, pulsed with ESR1Y537S or ESR1D538G neopeptide, and used as targets for clonotype 21 TCR Ts in a six hour Cr-51 release cytotoxicity assay. (O-P) ESR1 Y537S minimal epitope determination of clonotype 16 (O) or 21 (P) TCR Ts. Various nine and ten amino acid peptides containing the ESR1Y537S mutation were tested for their ability to stimulate TCR Ts in an IFN-γ ELISpot.

The characterization of the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line, which demonstrated highly specific and HLA-class I restricted recognition and killing of ESR1 Y537S and D538G peptide pulsed targets, encouraged us to isolate reactive TCRs from this line. We used a single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) based TCR discovery approach, in which we stimulated the donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line with ESR1 WT, Y537S, or D538G peptide for twelve hours, after which we stained cells in each condition with oligo-tagged antibodies (Cell Hashing20), allowing us to pool the three conditions prior to performing scRNAseq (Fig. 2d). We then identified clonotypes that upregulated IFN-γ and/or TNF-α in response to stimulation with ESR1 Y537S or D538G peptide but not WT peptide. Clonotype 16 was the highest IFN-γ expressing clone in response to stimulation with ESR1 Y537S peptide, and clonotype 21 was identified as upregulating IFN-γ expression in response to stimulation with either ESR1 Y537S or D538G peptide (Fig. 2e).

We obtained the full-length TCR α/β sequences of clonotypes 16 and 21 and then assembled these TCRs into retroviral vectors (Fig. 2f). To prevent TCR mispairing, we incorporated three modifications into the transgenic TCR α/β constant regions, namely: 1) replacing the human with murine TCR constant regions21; 2) single point mutations in the α/β constant regions to facilitate an additional disulfide linkage22,23, and 3) three hydrophobic substitutions in the transmembrane region of the TCR α constant region24. We transduced CD3 and CD28 antibody activated T cells (OKT3 blasts) and observed >90% transduction efficiencies for both the clonotype 16 and 21 TCRs (Fig. 2g and h). Consistent with the scRNAseq results, T cells transduced with the clonotype 16 TCR were highly reactive towards the ESR1 Y537S peptide (5039 vs 138 IFN-γ SFUs, mutant vs WT) (Fig. 2i). By testing the clonotype 16 TCR T response towards decreasing concentrations of ESR1 Y537S neopeptide, we additionally observed a high antigen sensitivity of this TCR, responding to as low as 1.093 nM peptide (110 IFN-γ SFUs) (Fig. 2j). T cells transduced with the clonotype 21 TCR initially displayed minimal response towards ESR1 Y537S and D538G peptides but not WT peptide (46, 258, and 4 SFU, respectively) (data not shown). However, following stimulation of the clonotype 21 transduced TCR Ts with autologous DCs pulsed with ESR1 Y537S peptide, the TCR Ts demonstrated robust dual specificity towards ESR1 Y537S and D538G but not WT peptide (2094, 3194, and 79 IFN-γ SFUs, respectively) (Fig 2k) by ELISpot assay and specifically killed autologous PHA blasts pulsed with ESR1 Y537S and D538G but not WT peptide (31.3%, 77.8%, and 9.1% cytotoxicity, respectively at a 40:1 E:T) (Fig. 2I).

To determine the HLA restriction of the TCRs, we cloned each of the six HLA-class I alleles from donor 1 PBMCs into a retroviral vector with a truncated CD19 (tCD19) reporter. We transduced fully-HLA-class I mismatched allogeneic OKT3 blasts with each individual candidate HLA allele and then assessed TCR T response towards the HLA transduced targets that were pulsed with cognate ESR1 neopeptide in a coculture IFN-γ ELISpot assay or Cr-51 release cytotoxicity assay. Clonotype 16 TCR Ts responded to ESR1 Y537S neopeptide only when presented by target cells expressing HLA-B*40:02 (Fig. 2m), while clonotype 21 TCR Ts responded to ESR1 Y537S and D538G neopeptide pulsed target cells only when transduced with HLA-C*01:02 (Fig. 2n). To identify the minimal ESR1 Y537S epitope recognized by clonotype 16 and 21 TCR Ts, we tested their responses to 8- to 10-mer constituents of the ESR1 Y537S 15-mer (NVVPLSDLLLEMLDA). For clonotype 16 TCR Ts we observed a maximum response towards the 10-mer peptide (PLSDLLLEML) (Fig. 2o), while clonotype 21 TCR Ts showed the greatest response towards the 10-mer peptide (NVVPLSDLLL) (Fig. 2p).

Clonotype 16 and 21 TCR Ts fail to recognize ESR1 mutant-expressing target cells

To determine whether clonotype 16 TCR Ts could recognize target cells that express the full-length ESR1 Y537S mutated protein, we transduced an HLA-B*40:02 expressing EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) with full-length ESR1 Y537S, and co-transduced 293Ts with HLA-B*40:02 and full-length ESR1 Y537S. 293Ts and LCLs were specifically selected as these cell lines express predominantly standard proteasome and immunoproteasome, respectively.25-27 We selected the cells expressing full-length ESR1 Y537S or mock vector by detection of a truncated CD34 reporter (Q8)28 by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and confirmed the overexpression of ERα by western blot (Supplementary Fig. 3). We then cocultured these cells with clonotype 16 TCR Ts and assessed antigen recognition by ELISpot. While we observed a robust clonotype 16 TCR T response towards ESR1 Y537S peptide-loaded LCL and 293T targets, we observed no response to unpulsed ESR1 Y537S overexpressing targets, compared to the mock vector transduced targets (Fig. 3a). To assess if the clonotype 16 TCR Ts could recognize the ESR1 Y537S overexpressing targets in a longer-term assay, we cocultured the TCR Ts with target cells for 72 hours and then assessed target cell killing and TCR T activation by flow cytometry. While we observed robust T cell activation by 4-1BB upregulation and near complete clearance of peptide-loaded LCL and 293T target cells when cultured with clonotype 16 TCR Ts, there was no killing or upregulation of 4-1BB after culture with unpulsed ESR1 Y537S overexpressing LCLs and 293Ts (Fig. 3b-c). We observed similar results when assessing the ability of clonotype 21 TCR Ts to recognize targets that were peptide-pulsed or expressed the full-length ESR1 D538G mutation, which included both targeting of edited LCLs and 293Ts, as well as an ER+ BC cell line MCF7 that was CRISPR edited to endogenously express the ESR1 D538G mutation (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Investigation of clonotype 16 TCR response towards ESR1 Y537S expressing targets.

(A) Response of clonotype 16 TCR Ts against HLA-B*40:02-expressing LCLs or 293Ts transduced to express full length ESR1Y537S or mock vector with or without target pulsing with ESR1Y537S neopeptide in an IFN-γ ELISpot. (B-C) TCR response and antitumor activity of clonotype 16 TCR Ts against HLA-B*40:02-expressing LCLs (B) or 293Ts (C) transduced to express full length ESR1Y537S or mock vector with or without pulsing with ESR1Y537S neopeptide in long-term coculture assay. T cells were coculture with targets for 72 hours, after which cells were harvested for flow cytometry. TCR recognition was assessed by staining for the transient T cell activation marker 4-1BB, and the number of residual tumor cells was determined with counting beads.

Characterizing endogenous antigen processing of ESR1 Y537S

We hypothesized that the discrepancy in the clonotype 16 and 21 TCR T responses towards ESR1 neopeptide-loaded vs ESR1 mutant-expressing targets was a result of inefficient endogenous processing of the cognate ESR1 neopeptides. To test this hypothesis, we performed immunopeptidomics analysis of HLA-B*40:02-expressing LCLs that were transduced and FACs sorted by expression of full-length ESR1 Y537S (LCL-Y537S) or mock vector (LCL-Empty) (Supplementary Fig. 3). As a positive control we also analyzed LCL-Y537S cells that were preloaded with the cognate ESR1 Y537S 10-mer peptide (PLSDLLLEML) (LCL-Y537S-peptide). To confirm ESR1 Y537S overexpression and our ability to detect ESR1 peptides by mass spectrometry (MS) in LCL-Y537S cells, we performed ERα immunoprecipitation MS (IP-MS) on the negative fraction lysate following HLA-class I pull-down. In the ERα IP-MS of LCL-Y537S cells, we detected 24 unique ERα peptides that collectively covered 45.04% of the ERα sequence (Fig. 4a), which importantly included a peptide containing the ESR1 Y537S mutation (NVVPLSDLLLEMLDAHR) (Fig. 4b). This confirmed the overexpression of ESR1 Y537S in these LCLs and the ability to detect the mutation by MS. HLA-class I eluted peptides were Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) labeled for quantification. Across the three conditions (LCL-Empty, LCL-Y537S, LCL-Y537S-peptide), ten HLA-class I eluted ERα peptides were detected, eight of which were quantifiable by TMT labeling. Among the eight TMT quantified ERα peptides, six were within ERα WT region (ERα 319 – 507) and were detected at reporter ion intensities above the LCL-Empty control in both the LCL-Y537S and LCL-Y537S-peptide conditions. Two TMT quantified ERα peptides containing the ESR1 Y537S mutation were detected, that being the 10mer (PLSDLLLEML) and a related 8mer (SDLLLEML). Critically, these two ESR1 Y537S mutant peptides were detected at reporter ion intensities above the LCL-Empty control only in the LCLs that were pulsed with the ESR1 Y537S neopeptide (LCL-Y537S-peptide), and not in the unpulsed LCL-Y537S condition (Fig. 4c). Overall, this data demonstrates endogenous processing and HLA class I presentation of select WT ERα peptides within the region ERα 319 – 507 and lack of endogenous processing of the mutated Y537S peptides, despite binding to HLA-B*40:02 when exogenously pulsed as a minimal peptide.

Figure 4: Immunopeptidomics analysis of ESR1 Y537S endogenous processing and presentation.

(A) Coverage of detected peptides through ERα IP-MS of ESR1 Y537S overexpressing LCLs. Green and yellow shading indicates detection of ERα peptides at false discovery rates of 1% and 5 %, respectively. (B) Mirror plot showing the observed (top) and expected (bottom) spectra of an ESR1 Y537S containing peptide (NVVPLSDLLLEMLDAH) detected through ERα IP-MS of LCL-Y537S. (C) Immunopeptidomics detection and TMT reporter ion intensity per million cells input of HLA-class I eluted ERα peptides from 1 x 108 mock-transduced LCLs (LCL-Empty), 1 x 108 ESR1 Y537S overexpressing LCLs (LCL-Y537S), or 0.5 x 108 ESR1 Y537S overexpressing LCLs that were pulsed with ESR1 Y537S peptide (LCL-Y537S-peptide).

DISCUSSION:

Here, we describe the expansion of T cells from the peripheral blood of both healthy donors and MBC patients with specificity for neopeptides derived from MBC driver missense mutations in AKT1, ESR1, PIK3CA, and TP53, and the isolation of two TCRs specific for ESR1 hotspot mutations from one of the healthy donor-derived MBCneo-CTL lines. We achieved high transduction efficiencies with the engineered TCRs, which conferred the TCR Ts with the ability to efficiently and selectively recognize and kill ESR1 neopeptide pulsed targets. However, we demonstrated through several in vitro models that these TCRs fail to recognize target cells expressing endogenous ESR1 mutations. The discrepancy of these TCRs in recognizing ESR1 neopeptide pulsed targets but not ESR1 mutant expressing targets was explained through immunopeptidomics analysis of ESR1 Y537S overexpressing LCLs, which identified several endogenously processed and presented ERα peptides in WT regions of the protein, but confirmed lack of processing of the cognate ESR1 Y537S peptide.

Our ability to expand neopeptide-specific T cells from the peripheral blood of healthy donors (8/14 lines) is notable. As these MBC driver mutations are not present in healthy tissues, the healthy donor-derived neopeptide-specific T cells are most likely derived from the naïve T cell repertoire. These findings concur with other reports of the expansion of neoantigen-specific T cells from the naïve T cell repertoire of healthy donors.29-33 We also generated MBCneo-CTL lines from MBC patients that expressed at least one targeted driver mutation, which included: ESR1 Y537S (3 patients), ESR1 D538G (3 patients), PIK3CA E545K (1 patient), PIK3CA H1047L (1 patient), PIK3CA H1047R (5 patients), and TP53 R175H (1 patient). While we could expand neopeptide-specific T cells from the peripheral blood of 7/11 (64%) of the MBC patients, we were surprised to find that none of these patients’ MBCneo-CTL lines responded to the mutation(s) that were detected in their tumors. It therefore appears likely that, as for healthy donors, the neopeptide-specific T cells expanded from these patients were derived from the naïve T cell repertoire. This was surprising, as we had expected patients to have developed immunity towards the driver mutations their cancers expressed, in which case we would expand memory T cells specific for these neopeptides. Indeed, several recent reports have described the identification and/or expansion of neoantigen-specific T cells from the antigen-experienced repertoire of peripheral blood T cells from cancer patients.34-42 Ultimately, we observed T cell reactivity in at least one MBCneo-CTL line towards 11/13 MBC driver mutations screened. Among these, there have been prior reports of T cell responses against AKT1 E17K43, PIK3CA H1047L7, TP53 R248Q, and TP53 R248W40,44. To our knowledge, we are the first to report T cell responses towards neopeptides derived from ESR1 Y537S, ESR1 D538G, PIK3CA E542K, PIK3CA E545K, PIK3CA H1047R, and TP53 R273H. However, it is important to note that the T cell reactivities observed in our IFN-γ ELISpot screening of MBCneo-CTL lines were towards pulsed 15-mer neopeptides, and thus did not assess the ability of these neopeptides to be endogenously processed.

In this study, we isolated the clonotype 21 TCR, which we identified as being specific for both ESR1 Y537S (NVVPLSDLLLEMLDA) and ESR1 D538G (NVVPLYGLLLEMLDA) neopeptides, but not the corresponding ESR1 WT (NVVPLYDLLLEMLDA) peptide. We presume that the unique dual specificity of this HLA-C*01:02-restricted TCR results from the high sequence similarity between the ESR1 Y537S and ESR1 D538G peptides. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a single TCR recognizing multiple driver mutations without recognition of the corresponding WT sequence. Dual-targeting TCRs could be used to expand the number of patients who may benefit from a single TCR T product.

We ultimately isolated and characterized two neoantigen specific TCRs that were: 1) ESR1 Y537S-specific/HLA-B*40:02 restricted; and 2) ESR1 Y537S/D538G-specific/HLA-C*01:02 restricted. TCR Ts engineered with each of these TCRs selectively and efficiently recognized and killed targets pulsed with cognate neopeptides. However, we did not observe responses of these neopeptide-specific TCRs against target cells that expressed the target mutations, either endogenously or through overexpression. Therefore, these TCRs appear to recognize neopeptides that are not endogenously processed. This conclusion was supported by our immunopeptidomics study of LCLs transduced to overexpress full-length ESR1 Y537S. Here, we identified six HLA-class I presented ERα WT peptides within the region (ERα 319 – 507). Critically, while we detected HLA-class I bound ESR1 Y537S peptides (PLSDLLLEML and SDLLLEML) from LCLs pulsed with ESR1 Y537S peptide, these neopeptides were not detected in LCLs that overexpressed ESR1 Y537S in the absence of peptide pulsing. These data indicate that ESR1 Y537S neopeptides are not endogenously processed by predominantly immunoproteasome expressing cells, at least in the context of the HLA class I alleles expressed by this LCL line (HLA-A*02:01, HLA-A*01:01, HLA-B*40:02, HLA-B*08:01, HLA-C*15:02, and HLA-C*07:01). Collectively, our data demonstrate that while ESR1 Y537S and D538G neopeptides are capable of binding to HLA molecules and eliciting potent T cell responses, these peptides are not endogenously processed, ultimately rendering them non-immunogenic in a physiologically relevant sense. These findings may lend support to the cancer immunoediting hypothesis, which postulates that immune pressures lead to elimination of sufficiently immunogenic cancer cells resulting in the outgrowth of less immunogenic ones.45 Indeed, several recent studies in patients have demonstrated that immune pressures lead to the emergence of tumor cells that express fewer high-quality neoantigens than expected.46,47 Therefore, the lack of immunogenicity of ESR1 Y537S and D538G mutations observed in this study may offer new insights into the mechanisms underlying the high prevalence of these mutations.

Based on our data, we propose a framework for considering how strategies used to select neoantigen specific T cells will influence the likelihood that isolated TCRs recognize endogenously processed neopeptides (bona-fide neoantigens) vs non-endogenously processed neopeptides (non-processed neopeptides). The expansion of T cell clones specific for non-processed neopeptides observed in this study was likely a result of the specific aspect of the MBCneo-CTL manufacturing process whereby naïve T cells were stimulated with minimal peptides that could bypass steps in the HLA-class I antigen processing pathway. While similar approaches have led to the identification of TCRs recognizing bona-fide neoantigens, such approaches have also produced TCRs specific for non-processed neopeptides.29,31,32,34-36,39 As antigen-experienced T cells have been primed and activated by bona-fide antigens in vivo, methods that have specifically expanded neoantigen-specific T cells from the antigen-experienced compartment of cancer patients (e.g. selection of memory or PD1+ T cells) have typically reported high rates of isolating TCRs specific for bona-fide neoantigens.37,38,40-42 When neoantigen specific T cells are expanded from naïve populations, naïve T cell clones recognizing bona-fide neoantigens can be preferentially expanded through stimulating with APCs edited to express neoantigens in the form of full-length or minigene transgenes, thus ensuring that T cells are only stimulated by processed and presented neoantigens.7,30,33 An additional approach could be to stimulate T cells from the naïve repertoire with minimal neopeptides that have been identified in immunopeptidomics datasets, and thus represent bona-fide neoantigens.48-50 Ultimately, our study demonstrates lack of endogenous processing of specific ESR1 Y537S and D538G neopeptides, and highlights the importance of incorporating TCR discovery approaches that consider antigen processing upfront.

METHODS:

PBMC collection and DC generation

Blood was collected from healthy donors in accordance with BCM IRB protocol #H15152. Blood was collected from MBC patients, whose tumors had at least one driver mutation of interest detected through Tempus sequencing, in accordance with BCM IRB protocol #H21783. PBMCs were then isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (StemCell Technologies, # 1114544). PBMCs were separated into CD14 (+) and CD14 (−) fractions by performing magnetic bead selection with CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, # 130-050-201). The CD14 (−) cell fraction was immediately cryopreserved. The CD14 (+) monocytes were differentiated into immature DCs by suspending at 0.5 x 106 cells/mL of CellGenix GMP DC medium (CellGenix, # 20801-0500) containing IL-4 (400 U/mL) (R&D Systems, # 204-IL/CF-MTO) and GM-CSF (800 U/mL) (R&D Systems, # 215-GM/CF-MTO) and culturing 1 mL per well in 24-well tissue culture treated plates for 5-7 days with cytokines replenished on day 3. Immature DCs were then harvested with gentle cell scraping. A fraction of immature DCs were cryopreserved for future use. Fresh or thawed immature DCs were then matured by suspending at 0.35 – 0.7 x 106 cells/mL of CellGenix GMP DC medium containing IL-4 (400 U/mL), GM-CSF (800 U/mL), TNF-α (10 ng/mL) (R&D Systems, # 210TA100), IL-6 (100 ng/mL) (R&D Systems, # 206-IL-050/CF), IL-1β (10 ng/mL) (R&D Systems, # 201-LB-025), and PGE-2 (1 μg/mL) (Sigma, # P6532) and culturing at 2 mL per well of a 12-well tissue culture plate for 2 days. Mature DCs were harvested by gentle cell scraping.

Generation of MBCneo-CTL lines

Mature DCs (up to 2 x 106 cells) were suspended in 100 μL CellGenix GMP DC media containing 25 ng/mL MBCneo-pepmix and incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and then washed once with CellGenix GMP DC media. Peptide loaded DCs were then cocultured with thawed CD14 (−) PBMCs at 0.2 x 106 and 2 x 106 cells per well of a 24-well tissue culture treated plate, respectively, in a final volume of 2 mL per well of CTL media (1:1 CLICKs:RPMI-1640, 5% Human Ab Serum, 2 mM Glutamax) containing IL-7 (10 ng/mL) (R&D Systems, # BT-007-01M), IL-12 (10 ng/mL) (InvivoGen, # rcyc-hil12), IL-15 (5 ng/mL) (R&D Systems, # BT-015-01M) and IL-6 (100 ng/mL). On day 6 following stimulation, T cells were split 1:1 and each well was replenished with 1 mL of fresh CTL containing 2X cytokines to restore the day 0 concentrations. On day 8-10 the expanding T cells were harvested, and MBCneo-pepmix pulsed DCs were used to restimulate the expanding T cells by coculturing at 0.1 x 106 and 1 x 106 cells per well of a 24-well tissue culture treated plate, respectively, in a final volume of 2 mL per well of CTL media containing IL-7 (10 ng/mL) and IL-15 (5 ng/mL). On day 3-4 following the second stimulation, T cells were split 1:1 and each well was replenished with 1 mL of fresh CTL containing 2X concentrations of IL-15 and IL-2 (Teceleukin, Ro 23-6019) to achieve final concentrations of 5 ng/mL and 100 U/mL, respectively, and T cells were further expanded until day 6-10 following second stimulation. In some cases, T cell lines were stimulated a third time with MBCneo-pepmix loaded DCs following the same protocol as the second stimulation, with T cells maintained in IL-15 (5 ng/mL) and IL-2 (100 U/mL).

TCR identification through single-cell RNA sequencing

The donor 1 MBCneo-CTL line was plated at 2 x 106 cells/mL in 200 μL/well and stimulated with 12.5 μg/mL peptide encoding ESR1 WT (NVVPLYDLLLEMLDA), Y537S (NVVPLSDLLLEMLDA), or D538G (NVVPLYGLLLEMLDA) for 12 hours. The T cells were then harvested and dead cells were removed using the Dead Cell Removal Kit (Miltenyi, # 130-090-101). Cell Hashing was then performed whereby T cells in each condition were stained with oligo-tagged antibodies (Biolegend, TotalSeq-C0251, C0252, and C0253) at 0.125 μg/million cells, and then pooled at a 1:1:1 ratio and a total cell concentration of 1 x 106 cells/mL. Single-cell RNA sequencing was then performed and analyzed as described in Supplementary Methods.

T cell assays

IFN-γ ELISpot.

ELISpot plates (Millipore, # MSIPS4W10) were coated primary anti-IFN-γ antibody as per the manufacturer’s instructions. On the day of the experiment, the plates were washed twice with PBS and blocked with 100 uL/well of CTL media at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for at least 1 hour. The plates were then washed twice with PBS, after which T cells, target cells, and/or peptides were added in a final volume of 200 uL/well. Negative controls consisted of T cells in media alone and positive controls consisted of T cells stimulated with 2.5 μg/mL of PHA-L (Sigma, # L4144). Plated T cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for about 16 hours, after which plates were developed using AEC substrate as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were imaged on the Mabtech Iris plate reader.

Chromium-51 (Cr-51) release cytotoxicity assay.

The cytotoxic potential of T cells was measured in standard 6 hour Cr-51 release cytotoxicity assays using E:T ratios ranging from 40:1 to 5:1. Effector T cells (MBCneo-CTL lines, TCR Ts, or non-transduced controls) were cultured with Cr-51 labeled target cells in triplicate in wells of a 96-well V-bottom plate at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 6 hours. For cases in which target cells were pulsed with peptide, 1 x 106 target cells were suspended in 100 μL of 25 μg/mL peptide solution and incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C and 5% CO2 just prior to Cr-51 labeling. Following the 6-hour culture, supernatants were harvested and radioactivity was measured in a Wizard2 automatic gamma counter. Percentage of specific lysis was calculated as follows: % specific cytotoxicity=[experimental release (cpm)−spontaneous release (cpm)]/[maximum release (cpm)−spontaneous release (cpm)]×100.

HLA restriction determination.

To determine the HLA restriction of TCRs of interest, allogeneic HLA-class I mismatched OKT3 blasts were transduced individually with each class I HLA expressed by the donor from which the TCR was derived. In the case of the clonotype 16 TCR, TCR Ts were generated by transducing allogeneic OKT3 blasts and an ELISpot was then performed whereby 0.1 x 106 TCR Ts were cultured with 0.1 x 106 HLA-transduced targets in the presence of 12.5 μg/mL cognate peptide. For the clonotype 21 TCR, TCR Ts were generated from autologous OKT3 blasts. The allogeneic HLA transduced OKT3 blasts were selected by expression of the tCD19 reporter using CD19 microbeads (Miltenyi, # 130-050-301). Selected OKT3 blasts expressing each candidate HLA were pulsed with cognate peptide, and TCR T killing was assessed through a 6 hour Cr-51 cytotoxicity release assay at a 40:1 E:T ratio.

Clonotype 16 TCR T long-term tumor coculture.

The HLA-B*40:02 expressing LCL cell line FH87 was transduced with SFG.Y537S.Q8 or mock vector. 293Ts were cotransduced with SFG.HLA-B*40:02.tCD19 along with SFG.Y537S or mock vector. LCLs and 293Ts were FAC sorted by expression Q8 or Q8/tCD19, respectively, using a Sony SH800 Cell Sorter. Next, 5 x 104 clonotype 16 TCR Ts were cultured with 5 x 104 LCL or 293T targets in triplicate in wells of a 96-well U-bottom (LCLs) or flat bottom (293Ts) tissue culture treated plate at 200 μL per well. After 72 hours of culture, the entire contents of each well, including supernatant, were harvested and collected into FACs tubes and stained with CD19-FITC, 4-1BB-PE, mTCRB-PC7, CD34-APC, CD3-APCAF750, Annexin V-PB, and 7AAD. Stained samples were acquired on a BD FACSCanto.

Immunopeptidomics and ERα immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry

The HLA-B*40:02 expressing LCL cell line FH87 was transduced with SFG.Y537S.Q8 (LCL-YS) or mock vector (LCL-Empty) and FAC sorted by expression of an abrogated CD34 reporter using a Sony SH800 Cell Sorter. 1 x 108 LCL-Empty and LCL-YS cells were harvested and washed twice with 20 mL of ice-cold PBS and then pelleted and snap frozen. Separately, LCL-YS cells were peptide pulsed by collecting into several conicals at 1 x 107 cells/tube, pelleting, and suspending each in 100 μL of 25 μg/mL ESR1 Y537S peptide (PLSDLLLEML) and incubating for 1 hour at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells in each conical were washed once with 15 mL of ice-cold PBS, and pellets were then pooled for a total of 0.5 x 108 cells total, washed once more in 50 mL of ice-cold PBS, and then pelleted and snap frozen (LCL-YS-peptide). ERα immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry and immunopeptidomics was then performed as described in Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported in part by the Susan Komen Career Catalyst Research CCR19606699, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) RR170024, the NIH SPORE in Breast Cancer 5P50CA058183, the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy Research Training Program T32 HL092332, the Clinical Translational Research Certificate of Added Qualification Training Program T32 GM136554, the NIH R37 MERIT Award BMB: R37CA248478, the CPRIT HSL: RP200443, the Cancer Research Trust New Zealand, the Murray Jackson Clinical Fellowship, the HSANZ New Investigator Scholarship, the NIH R01 CA072038, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation BCRF-22-055. This work was performed in part at the Single Cell Genomics Core at BCM partially supported by NIH S10OD025240 and CPRIT RP200504, and the Genomic and RNA Profiling Core at Baylor College of Medicine with funding from the NIH S10 grant (1S10OD023469). The IP-MS and immunopeptidomics experiments were performed in the Proteomics Laboratory of the Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center at BCM. We thank Dr. Norihiro Watanabe for designing the TCR constant region modifications and providing the TCR retroviral backbone plasmid used in this study.

Funding:

This research was supported in part by the Susan Komen Career Catalyst Research CCR19606699, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) RR170024, the NIH SPORE in Breast Cancer 5P50CA058183, the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy Research Training Program T32 HL092332, the Clinical Translational Research Certificate of Added Qualification Training Program T32 GM136554, the NIH R37 MERIT Award BMB: R37CA248478, the CPRIT HSL: RP200443, the Cancer Research Trust New Zealand, the Murray Jackson Clinical Fellowship, the HSANZ New Investigator Scholarship, the NIH R01 CA072038, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation BCRF-22-055. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, collection and analysis of data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest:

PS, WKL, AL, and VH have submitted a patent application for TCR discovery.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research performed in accordance with BCM IRB protocols #H15152 and #H21783.

Consent for publication

Patient consent for publication not required.

Availability of data and material

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramachandran I, Lowther D, Dryer-Minnerly R, Wang R, Fayngerts S, Nunez D, et al. Systemic and local immunity following adoptive transfer of NY-ESO-1 SPEAR T cells in synovial sarcoma. J. Immunother. cancer 7, 276 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Angelo SP, Van Tine BA, Attia S, Blay J-Y, Strauss SJ, Morales CMV, et al. SPEARHEAD-1: A phase 2 trial of afamitresgene autoleucel (Formerly ADP-A2M4) in patients with advanced synovial sarcoma or myxoid/round cell liposarcoma [Conference presentation]. in 2021 ASCO Annual Meeting vol. 39 11504–11504 (Wolters Kluwer Health, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong DS, Van Tine BA, Olszanski AJ, Johnson ML, Liebner DA, Trivedi T, et al. Phase I dose escalation and expansion trial to assess the safety and efficacy of ADP-A2M4 SPEAR T cells in advanced solid tumors [Conference presentation]. in 2020 ASCO Annual Meeting vol. 38 102 (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins PF, Kassim SH, Tran TLN, Crystal JS, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, et al. A Pilot Trial Using Lymphocytes Genetically Engineered with an NY-ESO-1–Reactive T-cell Receptor: Long-term Follow-up and Correlates with Response. Clin. Cancer Res 21, 1019–1027 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagarsheth NB, Norberg SM, Sinkoe AL, Adhikary S, Meyer TJ, Lack JB, et al. TCR-engineered T cells targeting E7 for patients with metastatic HPV-associated epithelial cancers. Nat. Med 27, 419–425 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafer P, Kelly LM & Hoyos V. Cancer Therapy With TCR-Engineered T Cells: Current Strategies, Challenges, and Prospects. Front. Immunol 13, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandran SS, Ma J, Klatt MG, Dündar F, Bandlamudi C, Razavi P, et al. Immunogenicity and therapeutic targeting of a public neoantigen derived from mutated PIK3CA. Nat. Med 28, 946–957 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, Sengupta S, Bertrand D, Weerasinghe A, et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 173, 371–385 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez-Jiménez F, Muiños F, Sentís I, Deu-Pons J, Reyes-Salazar I, Arnedo-Pac C, et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 555–572 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGranahan N, Favero F, De Bruin EC, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z & Swanton C. Clonal status of actionable driver events and the timing of mutational processes in cancer evolution. Sci. Transl. Med 7, 1–12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin 71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waks AG & Winer EP. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc 321, 288–300 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spoerke JM, Gendreau S, Walter K, Qiu J, Wilson TR, Savage H, et al. Heterogeneity and clinical significance of ESR1 mutations in ER-positive metastatic breast cancer patients receiving fulvestrant. Nat. Commun 7, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dustin D, Gu G & Fuqua SAW. ESR1 mutations in breast cancer. Cancer 125, 3714–3728 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Priestley P, Baber J, Lolkema MP, Steeghs N, de Bruijn E, Shale C, et al. Pan-cancer whole-genome analyses of metastatic solid tumours. Nature 575, 210–216 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouaoun L, Sonkin D, Ardin M, Hollstein M, Byrnes G, Zavadil J, et al. TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum. Mutat 37, 865–876 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, et al. High Frequency of Mutations of the PIK3CA Gene in Human Cancers. Science (80-. ). 304, 554 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KRM, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer Analysis Project. Nat. Genet 45, 1113–1120 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerdemann U, Katari U, Christin AS, Cruz CR, Tripic T, Rousseau A, et al. Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes Simultaneously Targeting Multiple Tumor-Associated Antigens to Treat EBV negative Lymphoma. Mol. Ther 19, 2258–2268 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoeckius M, Zheng S, Houck-Loomis B, Hao S, Yeung BZ, Mauck WM, et al. Cell Hashing with barcoded antibodies enables multiplexing and doublet detection for single cell genomics. Genome Biol. 19, 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen CJ, Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Rosenberg SA & Morgan RA. Enhanced Antitumor Activity of Murine-Human Hybrid T-Cell Receptor (TCR) in Human Lymphocytes Is Associated with Improved Pairing and TCR/CD3 Stability. Cancer Res. 66, 8878–8886 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen CJ, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA & Morgan RA. Enhanced Antitumor Activity of T Cells Engineered to Express T-Cell Receptors with a Second Disulfide Bond. Cancer Res. 67, 3898–3903 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuball J, Dossett ML, Wolfl M, Ho WY, Voss R-H, Fowler C, et al. Facilitating matched pairing and expression of TCR chains introduced into human T cells. Blood 109, 2331–2338 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haga-Friedman A, Horovitz-Fried M & Cohen CJ. Incorporation of Transmembrane Hydrophobic Mutations in the TCR Enhance Its Surface Expression and T Cell Functional Avidity. J. Immunol 188, 5538–5546 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abi Habib J, De Plaen E, Stroobant V, Zivkovic D, Bousquet MP, Guillaume B, et al. Efficiency of the four proteasome subtypes to degrade ubiquitinated or oxidized proteins. Sci. Rep 10, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahman MC, Schmitt TM, Paulson KG, Vigneron N, Buenrostro D, Wagener FD, et al. Targeting an alternate Wilms’ tumor antigen 1 peptide bypasses immunoproteasome dependency. Sci. Transl. Med 14, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lautscham G, Haigh T, Mayrhofer S, Taylor G, Croom-Carter D, Leese A, et al. Identification of a TAP-Independent, Immunoproteasome-Dependent CD8 + T-Cell Epitope in Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 2. J. Virol 77, 2757–2761 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philip B, Kokalaki E, Mekkaoui L, Thomas S, Straathof K, Flutter B, et al. A highly compact epitope-based marker/suicide gene for easier and safer T-cell therapy. Blood 124, 1277–1287 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Çınar Ö, Brzezicha B, Grunert C, Kloetzel PM, Beier C, Peuker CA, et al. High-affinity T-cell receptor specific for MyD88 L265P mutation for adoptive T-cell therapy of B-cell malignancies. J. Immunother. Cancer 9, 1–12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali M, Giannakopoulou E, Böschen M, Strønen E, Yang W, Toebes M, et al. Induction of neoantigen-reactive T cells from healthy donors. Nat. Protoc 14, 1926–1943 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato T, Matsuda T, Ikeda Y, Park J, Yoshimura S, Hikichi T, et al. Effective screening of T cells recognizing neoantigens and construction of T-cell receptor-engineered T cells. Oncotarget 9, 11009–11019 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen JS, Chang AR, Wick DA, Sedgwick CG, Mungall AJ, Martin SD, et al. Mapping the human T cell repertoire to recurrent driver mutations in MYD88 and EZH2 in lymphoma. Oncoimmunology 6, 1–10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strønen E, Toebes M, Kelderman S, Van Buuren MM, Yang W, Van Rooij N, et al. Targeting of cancer neoantigens with donor-derived T cell receptor repertoires. Science (80-. ). 352, 1337–1341 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen CJ, Gartner JJ, Horovitz-Fried M, Shamalov K, Trebska-McGowan K, Bliskovsky VV., et al. Isolation of neoantigen-specific T cells from tumor and peripheral lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest 125, 3981–3991 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carreno BM, Magrini V, Becker-Hapak M, Kaabinejadian S, Hundal J, Petti AA, et al. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity ofmelanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science (80-. ). 348, 803–808 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen JS, Sedgwick CG, Shahid A, Zong Z, Brumme ZL, Yu S, et al. Toward Personalized Lymphoma Immunotherapy: Identification of Common Driver Mutations Recognized by Patient CD8+ T Cells. Clin. Cancer Res 22, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gros A, Parkhurst MR, Tran E, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, Ilyas S, et al. Prospective identification of neoantigen-specific lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Nat. Med 22, 433–438 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cafri G, Yossef R, Pasetto A, Deniger DC, Lu Y, Parkhurst M, et al. Memory T cells targeting oncogenic mutations detected in peripheral blood of epithelial cancer patients. Nat. Commun 10, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tubb VM, Schrikkema DS, Croft NP, Purcell AW, Linnemann C, Freriks MR, et al. Isolation of T cell receptors targeting recurrent neoantigens in hematological malignancies. J. Immunother. Cancer 6, 1–14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malekzadeh P, Yossef R, Cafri G, Paria BC, Lowery FJ, Jafferji M, et al. Antigen experienced T cells from peripheral blood recognize p53 neoantigens. Clin. Cancer Res 26, 1267–1276 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leko V, Cafri G, Yossef R, Paria B, Hill V, Gurusamy D, et al. Identification of neoantigen-reactive T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of a patient with glioblastoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 9, 1–7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foy SP, Jacoby K, Bota DA, Hunter T, Pan Z, Stawiski E, et al. Non-viral precision T cell receptor replacement for personalized cell therapy. Nature 615, 687–696 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith KN, Llosa NJ, Cottrell TR, Siegel N, Fan H, Suri P, et al. Persistent mutant oncogene specific T cells in two patients benefitting from anti-PD-1. J. Immunother. Cancer 7, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malekzadeh P, Rosenberg SA, Deniger DC, Malekzadeh P, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, et al. Neoantigen screening identifies broad TP53 mutant immunogenicity in patients with epithelial cancers Neoantigen screening identifies broad TP53 mutant immunogenicity in patients with epithelial cancers. J. Clin. Invest 129, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schreiber RD, Old LJ & Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science (80-. ). 331, 1565–1570 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.AI Kraemer, Chong C, Huber F, Pak H, Stevenson BJ, Müller M, et al. The immunopeptidome landscape associated with T cell infiltration , inflammation and immune editing in lung cancer. Nat. Cancer (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Łuksza M, Sethna ZM, Rojas LA, Lihm J, Bravi B, Elhanati Y, et al. Neoantigen quality predicts immunoediting in survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature 606, 389–395 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim GB, Fritsche J, Bunk S, Mahr A, Unverdorben F, Tosh K, et al. Quantitative immunopeptidomics reveals a tumor stroma-specific target for T cell therapy. Sci. Transl. Med 14, 1–18 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi J, Goulding SP, Conn BP, McGann CD, Dietze JL, Kohler J, et al. Systematic discovery and validation of T cell targets directed against oncogenic KRAS mutations. Cell Reports Methods 1, 100084 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bear AS, Blanchard T, Cesare J, Ford MJ, Richman LP, Xu C, et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of mutant KRAS epitopes validates this oncoprotein for immunological targeting. Nat. Commun 12, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.