Abstract

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious and persistent psychiatric illness. Many individuals with AN cycle between stages of remission (i.e., relapse), with research documenting that cognitive remission generally lags behind nutritional/weight restoration. Yet, little is known about which mechanisms promote movement from partial remission in AN (defined as nutritional, but not cognitive, recovery) to full remission. Fear-based processes, including avoidance and approach behaviors, likely contribute to the persistence of cognitive-behavioral AN symptoms after nutritional restoration. The current study used intensive longitudinal data to characterize these processes during partial remission (N = 41 participants with partially remitted AN; 4,306 total observations). We aimed to a) characterize frequency of fear-based processes in real-time, b) investigate associations across fear-based processes and behavioral urges, and c) test if real-time associations among symptoms differed across commonly feared stimuli (e.g., food, social situations). On average, participants endorsed moderate fear and avoidance, with weight-gain fears rated higher than other feared stimuli. Momentary fear, avoidance, approach, and distress were all positively associated with AN behavior urges at one time-point and prospectively. Central symptoms and symptom connections differed across models with different feared stimuli. These findings provide empirical support for the theorized fear-avoidance-urge cycle in AN, which may contribute to the persistence of eating pathology during partial remission. Fear approach may be associated with temporary increases in urges, which should be considered during treatment. Future research should explore these associations in large, heterogeneous samples, and test the effectiveness of exposure-based interventions during partial remission.

Keywords: fear, avoidance, anorexia nervosa, remission, ecological momentary assessment

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious psychological disorder with low rates of full remission following treatment and high rates of relapse (Berends et al., 2018; Khalsa et al., 2017). Many patients with AN finish treatment in a state of partial remission (i.e., body mass index [BMI] > 18.5, but with continued eating disorder cognitive-affective symptoms; Bardone-Cone et al., 2018), and those in partial remission are more likely to relapse than those in full remission (Kordy et al., 2002). Thus, it is critical to better characterize partial remission in AN. Specifically, it is of utmost importance to investigate mechanisms that may determine relapse versus progression to full remission. In particular, fear-based processes, such as approach (i.e., behaviors that increase exposure to feared stimuli) and avoidance (i.e., behaviors to escape or prevent facing feared stimuli or outcome) may be maintaining factors present in AN (Christian & Levinson, 2022; Murray et al., 2018; Schaumberg et al., 2021). A better understanding of fear-based processes during AN in partial remission would allow for the development of evidence-based treatments to target these mechanisms directly, ultimately improving relapse-prevention interventions.

1.1. Fear, Approach, and Avoidance in AN

The anxiety-based model of AN posits that high levels of fear, avoidance, and anxiety play an important role in the development and maintenance of the disorder (Murray et al., 2018; Servatius, 2016; Steinglass et al., 2012). Specifically, AN is often conceptualized as a fear-based disorder, due to high rates of comorbidity and shared genetic links and personality factors with anxiety disorders, as well as a heightened predisposition to acquire fear, leading to development of core fears that maintain pathology (Lambert et al., 2021; Pallister & Waller, 2008; Strober, 2004). This model also suggests that ED behaviors develop from classical conditioning (e.g., pairing of food or weight gain with aversive outcomes, such as peer or parent rejection), and ED behaviors are reinforced through avoidance of feared outcomes (Cardi et al., 2019; Treasure et al., 2012). Recent preliminary empirical research supports these theoretical models, suggesting that those with AN have higher threat expectancy and negative affect during fear conditioning compared to controls (Lambert et al., 2021).

Avoidance and approach behaviors may modulate fear learning in AN, as in anxiety disorders (Christian & Levinson, 2022). For example, avoidance prevents learning that a feared stimulus is unlikely to lead to aversive outcomes, which inhibits extinction (Schlund et al., 2010). Additionally, reductions in anxiety following avoidance is a negative reinforcer and leads to increased reliance on avoidance behaviors (Mkrtchian et al., 2017). In EDs, avoidance can include compensatory behaviors, body avoidance, and ritualized eating behaviors, which reinforce and strengthen fear over time (Christian & Levinson, 2022). Conversely, approaching feared stimuli may lead to extinction of the conditioned fear by providing opportunities to form new associations with feared stimuli (Christian & Levinson, 2022). For those with AN, approach may occur, for example, when eating a feared food, confronting a feared body-related situation, or willingly experiencing uncomfortable physical sensations (e.g., fullness). Exposure therapy treatments, which involve fear approach behaviors, demonstrate that fear approach leads to reductions in fear and anxiety (e.g., Foa & Kozak, 1996; Forcadell et al., 2017). However, limited research has tested approach of feared stimuli explicitly outside of exposure therapy research, and there is a need to investigate how in vivo (i.e., in one’s real-life environment) approach of feared stimuli impacts anxiety and clinical outcomes.

1.2. Limitations in Understanding Fear in AN

There are several gaps in the literature related to the role of fear and avoidance in AN. First, almost all research to date on fear-related processes in AN has been either theoretical (Christian & Levinson, 2022; Murray et al., 2016, 2018; Schaumberg et al., 2021), or in the direct clinical application of exposure therapy (Butler & Heimberg, 2020; Cardi et al., 2019). The field has essentially skipped over the critical step of empirically testing theorized fear-related processes in AN to inform and optimize the use of exposure therapy interventions. A second important limitation is that most prior research on fear or avoidance in AN included samples with full-threshold AN (Brockmeyer et al., 2020; Cardi et al., 2019; Murray et al., 2018; Steinglass et al., 2007, 2012). Malnutrition present in acute AN impacts cognitive processes related to fear, decision making, and learning (Hemmingsen et al., 2021; Orquin & Kurzban, 2016; Riddle et al., 2013). Therefore, differences in cognitive resources between acute and partially remitted AN may theoretically result in differences in fear and avoidance patterns. This potential but untested disparity highlights the need to test processes related to fear learning and approach-avoidance decision making after patients have been nutritionally rehabilitated. Studying mechanisms of remission, such as fear and avoidance, during partial remission in AN can help elucidate what leads to relapse vs. full remission at this stage and inform relapse prevention and step-down care.

Third, there is a dearth of research in both the anxiety and eating disorder field that has utilized real-time measurement (e.g., ambulatory assessment) to study the theorized connections across fear, avoidance, and behavior. Laboratory measurement and surveys have limited ecological validity for understanding emotions and behaviors that occur in real time in participants’ naturalistic environment (Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2009). Two initial naturalistic studies examining the connections between fear-related processes and ED behavior have identified a relationship between anxiety lability and engagement in ED behaviors (Lavender et al., 2013) and a relationship between mealtime avoidance behaviors and higher anxiety and excessive exercise four hours later (Vanzhula et al., 2020). Thus, ambulatory assessment allows for increased sensitivity in identifying complex relationships in ED pathology across a shorter timeframe, which can aid in identifying and disrupting fear-related behavioral urges that an individual may experience over the course of hours or days. Lastly, most research examining the role of fear in eating disorders has focused on fear of food (Lender et al., 2018; Levinson et al., 2017) or fear of gaining weight (Levinson et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2018). Although fears of food and weight gain are core fears theorized to play an important role in EDs, and AN in particular (Fairburn, 2008; Murray et al., 2016), it is also important to investigate other specific fears in EDs to understand how different feared stimuli may uniquely relate to and maintain ED pathology (Brown & Levinson, 2022; Butler et al., 2023). Social fears (e.g., eating in public; judgment) and fears of physical discomfort (e.g., disliking how one’s body feels; feeling tense) are central to EDs (Levinson & Williams, 2020). Additionally, AN often is associated with high levels of emotion dysregulation and distress intolerance (Corstorphine et al., 2007; Prefit et al., 2019), such that individuals with AN may be more sensitive to and avoidant of uncomfortable emotions, leading to the use of ED behaviors to reduce emotional discomfort (Corstorphine et al., 2007; Espeset et al., 2012; Wildes et al., 2010). Thus, the relationships between fear of social situations, physical discomfort, and emotional discomfort with behavioral urges may be important to study across stages of AN remission, particularly partial remission, a period when there is nutritional, but not cognitive remission.

1.3. Current Study and Hypotheses

The current study (N = 41) aims to fill these gaps in the literature by 1) quantifying the endorsement of fear-based affective and behavioral symptoms in real time during partial AN remission, and 2) estimating vector autoregressive (VAR) models using intensive time-series data to elucidate prospective associations across fear-based processes (i.e., fear, fear approach, fear avoidance, distress) and common AN behavioral urges (restriction, purging, compensatory exercise, binge eating). We first estimated one VAR model focused on fear response to ED fears broadly (i.e., averaged at each timepoint) to understand the overarching relationships across fear-based symptoms and behavior urges. Next, as an exploratory aim, we estimated five separate models including specific feared stimuli assessed during the EMA period (i.e., food, weight gain, social situations, emotional discomfort, physical discomfort), to test if the relationship between fear-related processes and behavioral urges differed based on the unique feared stimuli. These exploratory models can elucidate potential trends in how different ED fears relate to different ED behaviors. We hypothesized that momentary approach, avoidance, distress, and fear would be associated with ED behavior urges, such that fear approach would be negatively related to behavioral urges and fear, avoidance, and distress would be positively related to ED behavior urges. Second, we hypothesized that avoidance and ED fears would be the most central (i.e., interconnected) symptoms in the overall model. Third, we hypothesized that the fear-specific models would differ in terms of central symptoms and symptom connections. However, given the exploratory nature of this research question, we did not make any specific hypotheses as to the pattern of these differences.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N = 41) were adults with AN in partial remission (i.e., individuals who 1) have a history of full-threshold AN in the past year, 2) are currently nutritionally restored and have achieved a healthy weight (as defined by a BMI at or above 18.5), and 3) continue to experience ED-related thoughts and urges), who were recruited from a lab research registry and social media. Participants completed all study procedures remotely from anywhere in the United States. Inclusion criteria included a past diagnosis of AN, current AN in partial remission (based on DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and age of at least 18 years. Exclusion criteria were active psychosis, mania, or active suicidal intent, as these comorbidities would make it difficult to complete study procedures and could compromise the safety of participants or reliability of data collected. No participants were excluded based on these exclusion criteria. See Table 1 for sample demographic information.

Table 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Information for Participants (N = 41)

| n (%) | M (SD) | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | 29.85 (8.92) | 18–58 | ||

| Past year lowest BMI | 17.47 (0.99) | 14.17–18.9 | ||

| T1 BMI | 20.05 (1.44) | 18.3–25.0 | ||

| T2 BMI | 20.32 (1.64) | 17.8–25.0 | ||

| Duration of illness (years) | 14.02 (8.18) | 1–33 | ||

| Gender Identity | ||||

| Cisgender women | 38 (92.7) | |||

| Nonbinary gender identity | 3 (7.3) | |||

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||

| Female | 41 (100) | |||

| AN subtype | ||||

| AN binge-purge | 24 (58.5) | |||

| AN restriction | 17 (41.5) | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 35 (85.4) | |||

| Asian or Asian-American | 1 (2.4) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2 (4.9) | |||

| Multiracial or Biracial | 1 (2.4) | |||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2 (4.9) | |||

| Current psychiatric medication use | ||||

| Yes | 29 (70.7) | |||

| No | 12 (29.3) | |||

| Currently in ED treatment | ||||

| Yes | 26 (63.4) | |||

| No | 13 (31.7) | |||

| Missing | 2 (4.9) | |||

| Comorbid anxiety diagnoses | ||||

| Social anxiety disorder | 2 (4.9) | |||

| Panic disorder | 3 (7.3) | |||

| OCD | 9 (22.0) | |||

| PTSD | 16 (39.0) | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 23 (56.1) | |||

Note. T1 = baseline; T2 = final study assessment; BMI = body mass index; AN = anorexia nervosa; OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder; ED = eating disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. As shown in this table, one participant had a baseline BMI of less than 18.5 (BMI = 18.3), This participants’ weight dropped slightly in between the phone screening and medical provider visit to confirm weight. This participant was allowed to remain in the study given eligibility on all study criteria during the screening.

2.2. Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB#: 21.0195). Participants completed a 30-minute diagnostic assessment over the phone, during which the principal investigator or trained graduate student reviewed informed consent, assessed eligibility and inclusion and exclusion criteria, and provided a brief training on the neurocognitive paradigms and EMA questionnaires. The training script is provided in the supplemental materials. Diagnosis of AN in partial remission was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (First, 2015) and the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Interview (Nobakht & Dezhkam, 2000). During the phone assessment, height/weight were collected through a timestamped picture or confirmation from a medical provider. Fifteen participants did not have confirmation of their weight because they opted out or because it was not feasible (e.g., limited access to scale and medical provider), so their self-report weight was used to determine eligibility for this study. However, past research suggests that self-reported height and weight are relatively accurate among individuals with AN (Ciarapica et al., 2010; McCabe et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 2009).

Eligible participants completed a short battery of self-report questionnaires and three neurocognitive tasks at baseline on their computer. After completing the neurocognitive paradigms and initial surveys, participants completed EMA questions sent to their mobile device five times a day for three weeks (105 timepoints per participant; 4,306 total observations). Surveys were sent on semi-random intervals between 9am and 8:30pm in the participants’ local time zone. Specifically, participants received the first daily survey at a random time between 9am and 10:30am daily, the next survey between 11:30am-1pm, then 2pm-3:30pm, 4:30pm-6pm, and 7pm-8:30pm. Each survey expired after one hour. Participants completed self-report questionnaires again at the completion of the three-week EMA period. A flow diagram to illustrate participant completion of study procedures is included in the supplemental materials.

Participants were compensated for their participation in the study. Specifically, participants were paid $10 for the initial surveys, $10 for the final surveys, $20 for the behavioral assessments, and up to $60 for the phone surveys, based on the percentage of phone surveys completed. Specifically, participants were paid $10 if they completed less than 50% of application-based surveys, $20 if they completed 50–60% of the surveys, $30 for 60%–70%, $50 for 70–80%, and $60 if they completed more than 80% of the surveys. In total, participants could be paid up to $100 for their participation. Most participants received the highest compensation (n = 29).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Interview measures.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5; First, 2015).

The SCID-5 is a semi-structured diagnostic interview used to determine DSM-5 diagnoses. Participants completed the module for AN to determine if they met DSM-5 criteria for AN in partial remission. The SCID-5 has good inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (First, 2015).

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Inventory (EDDI; Nobakht & Dezhkam, 2000).

The EDDI is a 31-item interview measure of ED symptoms based on the DSM-5. The EDDI assess frequency and intensity of ED behaviors and cognitions, as well as weight and menstrual history, over the previous year. In the current study, the EDDI was used to collect more detailed information about changes in participants’ AN presentation during the past year and confirm the diagnostic impression from the SCID-5.

2.3.2. Ecological Momentary Assessment.

Participants were sent brief questionnaires (1–3 minutes on average) via phone application on a semi-randomized, interval-contingent schedule. Items were adapted from existing valid and reliable assessments of ED symptoms, fear, and anxiety, including the EDE-Q, Eating Disorder Fear Questionnaire (EFQ), and Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS), which have been used in prior EMA research (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; Levinson et al., 2019; Wolpe, 1969). Items assessing approach and avoidance were created using empirically-established and common ED fears from the EFQ and Fear of Food Measure (Levinson et al., 2019; Levinson & Byrne, 2015). Specifically, participants were asked to what extent they approached or avoided ED-specific fears, to what extent they engaged in ED behaviors, and to what extent they have experienced cognitive-affective ED symptoms, ED fears, and anxiety since the last survey. Specific ED feared stimuli that were assessed for all participants at each EMA timepoint included feared foods, weight gain, social situations, physical discomfort, and emotional discomfort. All EMA items used in this study were rated on a 0–100 scale. Behavioral urges, rather than behavior engagement, were included in the models because measuring the strength of urges allows for quantification of behavior on a continuous scale (i.e., intensity of the desire to engage in a behavior), as opposed to a dichotomous scale (i.e., presence or absence of behavior). The EMA assessment is included in the supplemental materials.

2.4. Transparency and Openness

The study aims, hypotheses, and statistical analyses plan were not formally preregistered on the Open Science Framework or other platform. However, the proposed aims and analyses were presented to and approved by the first author’s dissertation committee prior to data collection as part of doctoral degree requirements. The R code used in the study is included in the supplemental materials. Deidentified data and any other measures or study materials are available upon request from the corresponding author. We report sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures in the study.

2.5. Data Analytic Procedure

2.5.1. Compliance, Missing Data, and Stationarity

Participants were included in the VAR analyses if they completed 40% of EMA surveys (42 surveys) or more, as imputation of missing data may lead to less reliable symptom networks for participants who completed less than half of surveys (Mansueto et al., 2020). Missing data from the EMA questionnaires was imputed with a Kalman smoothing filter, which is designed for time-series data, using the imputeTS package in R (Moritz & Bartz-Beielstein, 2017). One assumption of VAR models is stationarity, which assumes that the properties of time series data (e.g., mean or variance) do not change over time (Haslbeck et al., 2020; Horváth et al., 2014). Stationarity was tested using the Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) test using the tseries package in RStudio (Kokoszka & Young, 2016; Trapletti & Hornik, 2022). Variables in the model with significant nonstationarity were detrended by extracting the residuals of each variable regressed on cumulative time to meet the assumption of stationarity. Descriptive statistics for EMA variables are reported below.

2.5.2. VAR Models

Multi-level vector autoregressive (mlVAR) modeling was used to estimate group-level VAR models of momentary approach and avoidance behaviors, fear, and ED behavioral urges (Epskamp & Bringmann, 2019). mlVAR estimates temporal (i.e., directed network indicating unique time-lagged relationships; e.g., how variables predict on another across time), contemporaneous (i.e., undirected partial correlation network within one window of measurement; e.g., how variables are associated with each other at one time point) and between-subjects (i.e., an undirected partial correlation network of mean scores based on between-subjects variance; e.g., how participants scores relate to each other at one time point) models (Epskamp et al., 2018; Epskamp & Bringmann, 2019). Temporal models specifically examined relationships across one time lag (approximately 3–4 hours) to capture short-term relations across fears and behavioural urges, as both fear and urges are transient states that may fluctuate considerably across a short timescale. Models do not include associations that occurred overnight (e.g., the last timepoint of day 1 → first timepoint of day 2). Our interpretation focuses on the contemporaneous and temporal models because of the relatively small sample size (N = 41) for estimating between-subjects effects. The between-subjects model results are included in the supplemental materials.

We estimated six group-level network models. First, we estimated an overall model including the average overall approach, avoidance, ED fears, distress, and ED behavioral urges (restriction, compensatory exercise, purging, overeating), operationalized as the average scores at each EMA timepoint. Next, we estimated models for each specific feared stimuli (i.e., feared foods; weight gain; social situations; physical discomfort, and emotional discomfort) to understand how associations between fear, approach, avoidance, distress, and behavioral urges may differ based on the type of feared stimulus. Specifically, we wanted to test if approaching and avoiding specific fears were differently related to ED behavior urges. For example, approaching feared foods may be strongly associated with restriction urges, whereas avoiding social situations may be associated with binge eating urges. These exploratory models can provide insight into whether unique feared stimuli serve different functions in maintaining the ED. Strength centrality (i.e., the sum of the absolute value of a node’s connections) was used to identify the most interconnected symptoms across the temporal, between-subjects, and contemporaneous networks. Standardized beta weights (β) are reported for all significant (p < .05) edges in the models. R Code for the VAR models is included in Supplemental Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Compliance, Retention, and Missing Data

Fifty-five participants were eligible to participate in this study based on the screening, of which 47 participants downloaded the EMA application. The average compliance rate on the momentary surveys across participants who downloaded the application was 74.1% (SD = 27.4%; range = 2.0%–99.0%). After excluding participants who completed less than 40% of surveys (n = 6), the compliance rate of participants included in the VAR models was 83.3% (SD = 13.6%; range = 40.2%–99.0%). This rate of compliance for 105 surveys over the course of three weeks is considered very good (Wrzus & Neubauer, 2022). Before imputation, 18.7% of EMA data were missing. Visualization of patterns of missing data are included in the supplemental materials.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

Across the three-week EMA period, average overall fear was 37.19 (SD = 19.78; range = 0–94.2), avoidance was 31.45 (SD = 18.06; range = 0–88.6), approach was 24.15 (SD = 15.46; range = 0–85.6), and distress was 38.37 (SD = 24.10; range = 0–100). The average urge to restrict was 38.41 (SD = 26.26; range = 0–100), urge to purge was 6.25 (SD = 12.94; range = 0–90), urge to exercise was 28.38 (SD = 26.51; range = 0–100), and urge to binge eat was 5.88 (SD = 12.16; range = 0–100). See Table 2 for average endorsement of fear, approach, and avoidance for each feared stimulus (i.e., food, weight gain, social situations, physical discomfort, emotional discomfort). Zero order correlations among the average endorsement across all EMA items included in the networks are included in Table 3.

Table 2.

Average fear, approach, and avoidance during the EMA period (N = 41)

| Fear | Avoidance | Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| M (SD) | |||

| range | |||

| Food/eating | 38.39 (19.82) | 33.57 (16.80) | 21.79 (11.05) |

| 2.64–78.65 | 3.20–66.42 | 2–40.57 | |

| Social situations | 29.68 (16.97) | 22.24 (13.60) | 26.94 (13.96) |

| 1–80.86 | .04–63.59 | 1.18–61.75 | |

| Physical discomfort | 35.40 (21.38) | 31.25 (18.50) | 23.63 (13.85) |

| .21–83.5 | .39–64.80 | .37–50.83 | |

| Gaining weight | 46.18 (25.80) | 37.58 (20.95) | 24.44 (13.87) |

| 4.51–98.51 | 3.83–80.64 | .80–47.37 | |

| Emotional discomfort | 34.82 (21.90) | 30.72 (19.45) | 23.66 (12.97) |

| .40–85.23 | 1.24–75.04 | .37–50.60 | |

Note. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 0–100 visual analogue scale. Bolded values represent the stimulus/situation with the highest level of fear, avoidance, and approach in the sample during the ecological momentary assessment period.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations for Ecological Momentary Assessment Variables included in VAR Models

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1. | Fear | - | |||||||

| 2. | Avoidance | 0.81 | - | ||||||

| 3. | Approach | 0.37 | 0.20 | - | |||||

| 4. | Distress | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.24 | - | ||||

| 5. | Restriction urge | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.42 | - | |||

| 6. | Exercise urge | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.51 | - | ||

| 7. | Binge eating urge | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.16 | - | |

| 8. | Purging urge | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.50 | - |

Note. All correlations are significant at p < .05.

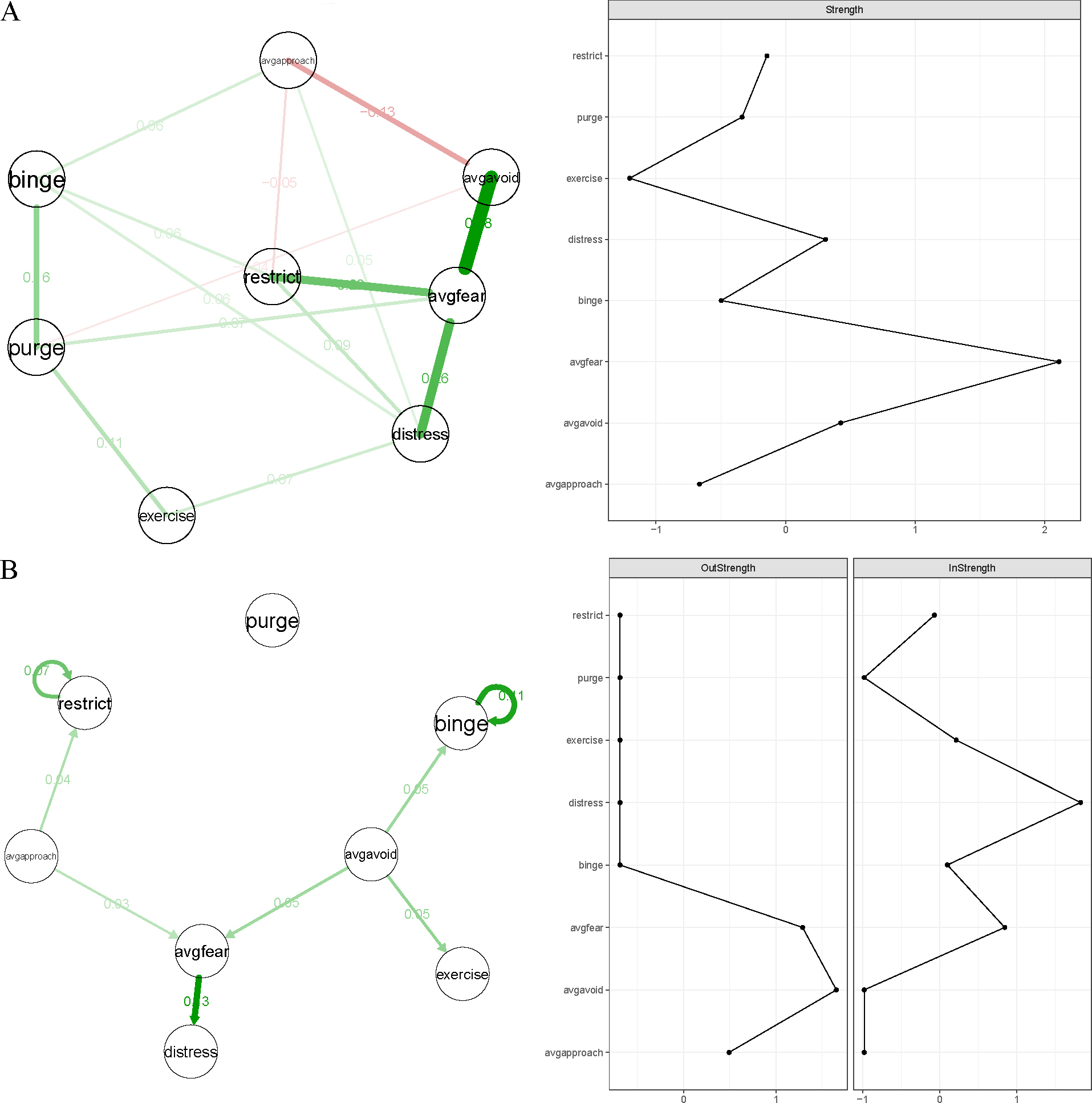

3.3. Overall VAR Models

The contemporaneous VAR model identified positive relationships between ED-related fears and avoidance (Standardized beta [β] = .38), distress (β = .26), restriction urges (β = .26), and purging urges (β = .07). ED-related avoidance was negatively related to fear approach (β = –.13) and purging urges (β = −.04). Fear approach behaviors were positively related with binge eating urges (β = .06) and distress (β = .05). Momentary distress was related to the urge to restrict (β = .09), binge eat (β = .06), and exercise excessively (β = .07). The most central symptom (i.e., the node with the strongest relationships to other nodes in the network) in the contemporaneous model was ED-related fears (ZStrength = 2.11).

In the temporal VAR model, avoidance of ED fears significantly, positively predicted ED-related fears (β = .05), binge eating urges (β = .05), and excessive exercise urges (β = .05) at the next timepoint (approximately three hours later). Approach of ED fears significantly, positively predicted ED-related fears (β = .03) and restriction urges (β = .04) at the next timepoint. ED-related fears positively predicted distress (β = .13) at the next timepoint. The node with the highest outStrength centrality (i.e., strongest predictor of other nodes at the next timepoint) in the temporal model was avoidance of ED-related fears (ZOutStrength = 1.65) and the node with the highest inStrength centrality (i.e., predicted most strongly by other nodes at the previous timepoint) in the temporal model was distress (ZInStrength = 1.83). See Figure 1 for a visual depiction and strength centrality graphs for the contemporaneous and temporal network models.

Figure 1.

VAR Models and Centrality Graphs

Note. Part A represents contemporaneous associations (at one timepoint) and part B represents temporal associations across approximately 3–4 hours. All edges depicted in the models were statistically significant at p < .05 (Epskamp & Fried, 2018).

3.4. Fear-specific VAR Models

The detailed results from the fear-specific VAR models and related figures are included in the supplemental materials. Briefly, these exploratory models suggest that there are differences in both central symptoms and the strength of connections between fear-based processes and ED symptoms depending on the type of ED fear (i.e., fear of food, weight gain, social situations, physical discomfort, emotional discomfort) included in the model. For example, fear was the most central symptom in the contemporaneous fear of food, social situations, and physical discomfort networks, whereas avoidance was the most central symptom in the fear of emotional discomfort network, and purging was the most central symptom in the fear of weight gain network. See Table 4 for an overview of descriptive information (i.e., central symptoms and bridge connections) in the fear-specific VAR models.

Table 4.

Summary of differences across fear-specific networks

| ED fear | Network type | Central Symptom | Strongest bridge connections |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Food | Contemporaneous | Fear of food | Food fear-restriction (.30) |

| Food approach-purging (.07) | |||

| Food avoid-purging (−.06) | |||

| Temporal | Food approach; purging | Purging → food fear (−.03) | |

| Food approach → binge (.03) | |||

| Weight gain | Contemporaneous | Purging | WG fear-purging (.11) |

| Distress-exercise (.11) | |||

| WG fear-exercise (.09) | |||

| Temporal | WG approach | ||

| No bridge connections | |||

| Social situations | Contemporaneous | Social fears | Social avoidance-restriction (.06) |

| Distress-binge (.06) | |||

| Social avoidance-binge (.06) | |||

| Temporal | Social fears | Exercise → social fear (.03) | |

| Social fear → exercise (.04) | |||

| Physical discomfort | Contemporaneous | Physical fears | Physical fear-restriction (.10) |

| Physical fear-purge (.07) | |||

| Distress-binge (.06) | |||

| Temporal | Physical fears | ||

| No bridge connections | |||

| Emotion discomfort | Contemporaneous | Emotion avoidance | Emotion approach-binge (.07) |

| Emotion approach-purge (.07) | |||

| Distress-purge (.06) | |||

| Temporal | Emotion avoidance | Emotional avoid → binge (.08) | |

| Emotional avoid → exercise (.05) | |||

| Exercise → emotion approach (.05) | |||

Note. Bridge connections are significant associations across fear-based nodes and behavioral urges. WG = weight gain; → = partial directed correlation; - = partial undirected correlation

4. Discussion

This study investigated how fear-related processes (i.e., fear, distress, avoidance, and approach) were related to ED behavioral urges (i.e., restriction, binge eating, purging, excessive exercise) in real time, for those in partial remission from AN. Overall, findings suggest that ED fears, avoidance behaviors, and distress are frequently endorsed during the stage of partial remission. These fear-related symptoms were positively, contemporaneously associated with urges to restrict, purge, exercise, and binge eat in real time. Temporally, avoidance predicted future binge eating and excessive exercise urges and approach predicted restriction urges at the next time-lag. These findings are partially consistent with our hypotheses, in that we predicted fear, avoidance, and distress would be positively associated with behavior urges, representing a potential positive-feedback loop maintaining AN pathology. However, fear approach was also positively associated with behaviors, which is contrary to our hypotheses and prior research suggesting approach of feared stimuli via exposure leads to symptom reductions (Butler & Heimberg, 2020). The timescale on which these associations were tested may provide important context for understanding these associations. Lastly, our exploratory models identified possible unique associations between fear-related processes and urges across different types of feared stimuli (i.e., food, weight gain, social situations, physical discomfort, and emotional discomfort). Below we discuss the potential implications of these findings for treatment optimization and relapse prevention for AN through the incorporation of fear-based mechanisms into treatment.

4.1. Endorsement of Fear-based Symptoms in Real Time

As there have been no real-time investigations of fear approach or avoidance in EDs, including AN, we first aimed to understand the frequency of fear and fear-related behaviors in our sample. We found that in our sample overall, participants endorsed moderate levels of fear (Ms = 29.68–46.18 on a 0 to 100 scale) and avoidance (Ms = 22.24–37.58), and slightly lower levels of fear approach (21.79–26.94) in response to commonly feared situations or stimuli. As such, participants with AN in partial remission on average may continue to experience moderate levels of fear and engage in more avoidance behaviors compared to approach behaviors, which may maintain AN symptoms. Importantly, there was high between-persons heterogeneity in the endorsement of these fear-based symptoms in our sample. For example, two participants with similar fear ratings (40.62 and 42.62), endorsed very different levels of fear approach (40.21 and 1.44). This heterogeneity highlights the importance of personalized assessment and treatment of fear-based symptoms during partially remitted AN. There was also considerable within-person heterogeneity (i.e., one individual experiencing fluctuations in fear-based symptoms across hours and days). Thus, another important direction for future research is to investigate which situational factors may impact the tendency to approach or avoid feared stimuli.

Although there was heterogeneity within and across participants, overall, there were significant differences in average endorsement of fear, approach, and avoidance across different feared stimuli. Situations that could lead to weight gain had significantly higher fear and avoidance ratings, compared to all other feared stimuli assessed in this study. This finding is consistent the DSM-5 conceptualization of AN, in which fear of weight gain is a core feature of the disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Additionally, high average endorsement of fear of weight gain during partial remission is consistent with prior research suggesting that weight and shape concerns are persistent across stages of recovery (Khalsa et al., 2017; Steinglass et al., 2020). As such, reduction of fear and avoidance related to gaining weight may be an important treatment target for many patients at this stage of recovery. Interventions focused on weight gain fears are needed for patients with AN in partial remission.

Social situations had significantly lower fear and avoidance ratings on average, compared to all other stimuli. This finding could have several possible explanations. First, social situations may be more rewarding than other feared stimuli (e.g., physical or emotional discomfort), leading to higher motivation to approach despite possible feared consequences (Tamir & Hughes, 2018). Second, many social situations are externally reinforced (e.g., sense of obligation to attend), which makes avoidance more difficult. Lastly, it is possible that this finding was driven by individual variability within our sample, as some participants did not have significant social fears as a part of their eating disorder. These descriptive statistics may not be generalizable, as this study used a relatively small sample size of individuals with AN in partial remission. However, these preliminary findings provide a foundation for understanding the prevalence of fear-based symptoms in real time, upon which future research should expand.

4.2. Relationships across Fear, Avoidance, and Behavior Urges

In the VAR models, fear and avoidance were positively related to several types of ED behavior urges, including binge eating, excessive exercise, purging, and restriction at one time and at the next lag (approximately 3–4 hours later). These associations are important, as this study is the first empirical research to support the theoretical proposition that fear and avoidance positively and prospectively predict each other and future ED symptoms in real time in AN. Additionally, avoidance predicted the urge to binge eat or exercise excessively at the next time point, which represents an important pathway that may contribute to the maintenance of AN. This finding aligns with the anxiety-based model of AN, which posits that ED behaviors are a form of avoidance (Christian & Levinson, 2022; Steinglass et al., 2011). These models may be helpful to incorporate into psychoeducation during treatment for AN by depicting how avoidance and fear may maintain the function or impairment related to one’s ED. Additionally, exposure-based treatment may be helpful during this stage of remission to prevent persistent fear and avoidance during partial remission from contributing to the relapse of ED behaviors.

4.3. Fear Approach and Behavior Urges

In addition to fear and avoidance, fear approach was also significantly associated with ED behavior urges. Surprisingly, in the contemporaneous model, fear approach was positively associated with the urge to overeat and momentary distress, and in the temporal model, fear approach positively predicted the urge to restrict at the next timepoint. These associations were against hypotheses, as we predicted that fear approach would be negatively associated with ED symptoms and anxiety. However, timescale may play an important role in the conceptualization of these relationships. Specifically, these relationships all occur across a few minutes (i.e., contemporaneous) or across a few hours (i.e., temporal). It is well established in the literature that exposure to feared stimuli is associated with a temporary increase in distress, and that repeated exposure leads to long-term reductions in anxiety (Abramowitz et al., 2019; Blakey & Abramowitz, 2016; Olatunji et al., 2009). Thus, it makes sense that fear approach may be associated with increased fear, distress, and ED symptoms over the course of a few minutes or hours. Based on these models alone, it is unclear whether fear approach is negatively associated with distress and ED symptoms over a longer timeframe. This question requires further testing with data collected over a longer time frame and using multiple time scales.

Additionally, it is important to consider these findings within the context of partial remission. It is possible that participants in the current study are at a point in recovery in which they are more likely to approach feared stimuli than earlier stages of recovery (i.e., acute AN), but still experience high levels of distress and urges afterwards. In line with habituation and inhibitory learning theories of exposure, this relationship between fear approach and distress may diminish in later stages of remission. Empirical research testing the relationship between fear approach and AN pathology across stages of remission is needed to further investigate this finding.

4.4. Fear-Specific Model Differences

As a final exploratory aim of this study, we also sought to investigate if there were differences in the presence or strength of connections across models with different feared stimuli (i.e., food, weight gain, social situations, physical discomfort, emotional discomfort). Although these results are preliminary, differences in both central symptoms and symptom connections were identified. For example, the strongest association in the fear of food model was the connection between fear of food and urge to restrict, compared to the fear of weight gain model, in which fear of weight gain-urge to purge and distress-urge to exercise were the strongest edges, and the fear of emotional discomfort model, in which emotion approach-urge to binge eat and emotion approach-urge to purge were most related symptoms. The most central symptom for most of the exploratory models was fear, except for the weight gain and emotional discomfort models. In the emotion discomfort models (contemporaneous and temporal), emotional avoidance was most central, which is in line with past research suggesting that emotional avoidance is related to ED behaviors in AN (Haynos et al., 2015; Wildes et al., 2010). It is important to investigate fear-related responses to specific fears in EDs, in addition to overall fear, to better understand how to effectively target these processes during treatment.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

There are limitations to the present study. Firstly, the sample size is relatively small and comprised primarily of cisgender, white women, both of which are limiting factors for generalizability of findings. Additionally, the sample is homogenous in terms of the stage of illness (i.e., partial remission). It is important to study this critical and understudied illness stage in AN, rather than the more commonly studied acute stage of the disorder; however, future research should investigate if these associations generalize to other stages of AN or individuals in partial recovery who did not meet the stringent definition used in this study (e.g., individuals recovering from atypical AN). A third limitation of this study is that the EMA measure utilized was developed for the current study, and its psychometric properties are unknown. The development of this measure was based on past valid and reliable measures of ED symptoms, ED fears, and anxiety (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; Levinson et al., 2019; Levinson & Byrne, 2015; Wolpe, 1969); however, this is a new adaptation of these measures to a EMA format. With the rapid expansion of EMA research, it is important to develop EMA measures with good validity, reliability, and real-world applicability. Relatedly, all EMA data and some of the height and weight data used to determine remission status were self-report and are limited by self-awareness and self-report biases. Fourth, this study examined associations between ED symptoms, ED fears, approach, and avoidance at one timepoint and at the next lag (approximately 3 hours later); the optimal lag for identifying meaningful relationships is unknown. The timescale of measurement has a significant impact on the findings of idiographic research (Jacobson et al., 2019; Levinson et al., 2022); thus, it is important to consider lived experience and statistical advancements to identify the optimal timescale for measuring these associations. Fifth, the symptoms included in our models may not represent all relevant constructs related to momentary fear learning and ED pathology. Other symptoms, such as distress tolerance, physiological response to feared situations, or expectancy violation, may be relevant to these models and should be explored in future conceptualizations and models of AN. Lastly, this study was not formally preregistered on a publicly available platform (e.g., OSF), which limits transparency.

Due to the pilot nature of this research, this project was largely exploratory, and results can serve as a springboard for multiple lines of study. Follow-up studies should extend this work to other EDs, anxiety-based disorders, and different stages of AN remission. For example, future research should test if ED-related fear approach and avoidance impact the development of AN in adolescents and young adults or if these mechanisms impact relapse after full remission. Further, the results of the current study identified that fear and avoidance may contribute to maintaining AN pathology in individuals with AN in partial remission across hours and days. This finding suggests that step-down care or relapse prevention interventions for partially remitted AN should address fear and avoidance. Future research should test whether exposure-based treatments designed to target fear and avoidance improve rates of remission and decrease relapse among those who have been weight restored from AN. Additionally, these models could inform just-in-the-moment adaptive interventions to intervene on these fear-based AN symptoms in real time.

4.6. Conclusions

This study investigated the relationships across fear-based processes and ED behavior urges in real time in partially remitted AN. ED fears and avoidance behaviors were frequently endorsed in our sample, and these symptoms were positively related to ED behavioral urges at one time and at the following lag (about 3–4 hours later). Fear approach behaviors were also related to higher urges to engage in restriction and binge eating, which may be attributed to momentary increases in distress during and immediately following fear approach. These findings provide preliminary evidence for momentary fear-based processes that may maintain ED pathology during partial remission in AN. Future research should investigate the integration of fear and avoidance into relapse prevention, step-down care, and supplementary just-in-time adaptive interventions to help more individuals with AN reach and maintain full remission.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Fear and avoidance were frequently endorsed during partial remission.

Fear and avoidance predicted future eating disorder behavior urges.

Approach behaviors were associated with momentary increases in distress and urges.

Associations between urges and fear-based symptoms differed across feared stimuli.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my dissertation committee, Dr. Ann Haynos, Dr. Sara Bufferd, Dr. Tamara Newton, and Dr. Brendan Depue for their support and feedback relevant to this project. Data collection would not have been possible without help from stellar research assistants, Sam Minrath, Lesley Hillmer, Callie Ernspiker, Sara Clark, and Emma Roberts.

Funding:

Caroline Christian is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health F31 National Research Service Award (F31MH127892). Data collection for this project was supported by the American Psychological Association Dissertation Research Grant and University of Louisville Graduate Network of Arts & Sciences Research Grant. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health, American Psychological Association, or Graduate Network of Arts & Sciences.

Footnotes

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, & Whiteside SPH (2019). Exposure Therapy for Anxiety, Second Edition: Principles and Practice. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.). (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone-Cone AM, Hunt RA, & Watson HJ (2018). An overview of conceptualizations of eating disorder recovery, recent findings, and future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(9), 79. 10.1007/s11920-018-0932-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berends T, Boonstra N, & van Elburg A (2018). Relapse in anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 31(6), 445. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakey SM, & Abramowitz JS (2016). The effects of safety behaviors during exposure therapy for anxiety: Critical analysis from an ihibitory learning perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 1–15. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer T, Burdenski K, Anderle A, Voges MM, Vocks S, Schmidt H, Wünsch-Leiteritz W, Leiteritz A, & Friederich H (2020). Approach and avoidance bias for thin-ideal and normal-weight body shapes in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, erv.2744. 10.1002/erv.2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ML, & Levinson CA (2022). Core eating disorder fears: Prevalence and differences in eating disorder fears across eating disorder diagnoses. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(7), 956–965. 10.1002/eat.23728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RM, & Heimberg RG (2020). Exposure therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 101851. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RM, Williams B, & Levinson CA (2023). An examination of eating disorder fears in imaginal exposure scripts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 326, 163–167. 10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi V, Leppanen J, Mataix-Cols D, Campbell IC, & Treasure J (2019). A case series to investigate food-related fear learning and extinction using in vivo food exposure in anorexia nervosa: A clinical application of the inhibitory learning framework. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 27(2), 173–181. 10.1002/erv.2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian C, & Levinson CA (2022). An integrated review of fear and avoidance learning in anxiety disorders and application to eating disorders. New Ideas in Psychology, 67, 100964. 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2022.100964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarapica D, Mauro B, Zaccaria M, Cannella C, & Polito A (2010). Validity of self-reported body weight and height among women including patients with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 15(1), e74–e80. 10.1007/BF03325282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corstorphine E, Mountford V, Tomlinson S, Waller G, & Meyer C (2007). Distress tolerance in the eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 8(1), 91–97. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, & Bringmann MKD and L. F. (2019). mlVAR: Multi-Level Vector Autoregression (0.4.4) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mlVAR

- Epskamp S, & Fried EI (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. 10.1037/met0000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ, Mõttus R, & Borsboom D (2018). The Gaussian Graphical Model in Cross-sectional and Time-series Data. ArXiv:1609.04156 [Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.04156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeset EMS, Gulliksen KS, Nordbø RHS, Skårderud F, & Holte A (2012). The link between negative emotions and eating disorder behaviour in patients with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 20(6), 451–460. 10.1002/erv.2183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG (2008). Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders | Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Cognitive-Behavior-Therapy-and-Eating-Disorders-Fairburn/c25dfa46ef03eced6c48e35e0acf50bcb7e1538f [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB (2015). Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID). In Cautin RL & Lilienfeld SO (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology (pp. 1–6). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, & Kozak MJ (1996). Psychological treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. In Long-term treatments of anxiety disorders (pp. 285–309). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Forcadell E, Torrents-Rodas D, Vervliet B, Leiva D, Tortella-Feliu M, & Fullana MA (2017). Does fear extinction in the laboratory predict outcomes of exposure therapy? A treatment analog study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 121, 63–71. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck JMB, Bringmann LF, & Waldorp LJ (2020). A Tutorial on Estimating Time-Varying Vector Autoregressive Models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 0(0), 1–30. 10.1080/00273171.2020.1743630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynos AF, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, & Le Grange D (2015). Initial test of an emotional avoidance model of restriction in anorexia nervosa using ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 68, 134–139. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmingsen SD, Wesselhoeft R, Lichtenstein MB, Sjögren JM, & Støving RK (2021). Cognitive improvement following weight gain in patients with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 29(3), 402–426. 10.1002/erv.2796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horváth L, Kokoszka P, & Rice G (2014). Testing stationarity of functional time series. Journal of Econometrics, 179(1), 66–82. 10.1016/j.jeconom.2013.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NC, Chow S-M, & Newman MG (2019). The Differential Time-Varying Effect Model (DTVEM): A tool for diagnosing and modeling time lags in intensive longitudinal data. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 295–315. 10.3758/s13428-018-1101-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SS, Portnoff LC, McCurdy-McKinnon D, & Feusner JD (2017). What happens after treatment? A systematic review of relapse, remission, and recovery in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(1), 20. 10.1186/s40337-017-0145-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszka P, & Young G (2016). KPSS test for functional time series. Statistics, 50(5), 957–973. 10.1080/02331888.2015.1128937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kordy H, Krämer B, Palmer RL, Papezova H, Pellet J, Richard M, Treasure J, & B6 CA (2002). Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence in eating disorders: Conceptualization and illustration of a validation strategy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(7), 833–846. 10.1002/jclp.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert ER, Treasure J, Purves K, McGregor T, Bergou N, Kan C, Breen G, Eley T, & Cardi V (2021). Fear conditioning in women with anorexia nervosa and healthy controls: A preliminary study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/fear-conditioning-in-women-with-anorexia-nervosa-and-healthy-controls-a-preliminary-study(9a8b6b5c-4fce-42e8-896b-26be4ffe88c3).html [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, De Young KP, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Peterson CB, & Le Grange D (2013). Daily patterns of anxiety in anorexia nervosa: Associations with eating disorder behaviors in the natural environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(3), 672–683. 10.1037/a0031823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lender A, Meule A, Rinck M, Brockmeyer T, & Blechert J (2018). Measurement of food-related approach–avoidance biases: Larger biases when food stimuli are task relevant. Appetite, 125, 42–47. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Brosof LC, Ma J, Fewell L, & Lenze EJ (2017). Fear of food prospectively predicts drive for thinness in an eating disorder sample recently discharged from intensive treatment. Eating Behaviors, 27, 45–51. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, & Byrne M (2015). The fear of food measure: A novel measure for use in exposure therapy for eating disorders: The Fear of Food Measure. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(3), 271–283. 10.1002/eat.22344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Hunt RA, Christian C, Williams BM, Keshishian AC, Vanzhula IA, & Ralph-Nearman C (2022). Longitudinal group and individual networks of eating disorder symptoms in individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 131(1), 58–72. 10.1037/abn0000727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Vanzhula IA, & Christian C (2019). Development and validation of the eating disorder fear questionnaire and interview: Preliminary investigation of eating disorder fears. Eating Behaviors, 35, 101320. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.101320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, & Williams BM (2020). Eating disorder fear networks: Identification of central eating disorder fears. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(12), 1960–1973. 10.1002/eat.23382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Williams BM, & Christian C (2020). What are the emotions underlying feeling fat and fear of weight gain? Journal of Affective Disorders. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansueto AC, Wiers R, van Weert J, Schouten BC, & Epskamp S (2020). Investigating the feasibility of idiographic network models [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/hgcz6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe RE, McFarlane T, Polivy J, & Olmsted MP (2001). Eating disorders, dieting, and the accuracy of self-reported weight. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(1), 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, Arcelus J, & Wright S (2009). Accuracy of self-reported weight and height among women with eating disorders: A replication and extension study. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(5), 366–370. 10.1002/erv.950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkrtchian A, Aylward J, Dayan P, Roiser JP, & Robinson OJ (2017). Modeling avoidance in mood and anxiety disorders using reinforcement learning. Biological Psychiatry, 82(7), 532–539. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S, & Bartz-Beielstein T (2017). imputeTS: Time Series Missing Value Imputation in R. The R Journal, 9(1), 207. 10.32614/RJ-2017-009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SB, Loeb KL, & Grange DL (2016). Dissecting the core fear in anorexia nervosa: Can we optimize treatment mechanisms? JAMA Psychiatry, 73(9), 891–892. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SB, Strober M, Craske MG, Griffiths S, Levinson CA, & Strigo IA (2018). Fear as a translational mechanism in the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 95, 383–395. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobakht M, & Dezhkam M (2000). An epidemiological study of eating disorders in Iran. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28(3), 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Deacon BJ, & Abramowitz JS (2009). The cruelest cure? Ethical issues in the implementation of exposure-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(2), 172–180. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orquin JL, & Kurzban R (2016). A meta-analysis of blood glucose effects on human decision making. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 546–567. 10.1037/bul0000035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallister E, & Waller G (2008). Anxiety in the eating disorders: Understanding the overlap. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 366–386. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prefit A-B, Cândea DM, & Szentagotai-Tătar A (2019). Emotion regulation across eating pathology: A meta-analysis. Appetite, 143, 104438. 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle MC, McKenna MC, Yoon YJ, Pattwell SS, Santos PMG, Casey BJ, & Glatt CE (2013). Caloric restriction enhances fear extinction learning in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(6), 930–937. 10.1038/npp.2012.268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaumberg K, Reilly EE, Gorrell S, Levinson CA, Farrell NR, Brown TA, Smith KM, Schaefer LM, Essayli JH, Haynos AF, & Anderson LM (2021). Conceptualizing eating disorder psychopathology using an anxiety disorders framework: Evidence and implications for exposure-based clinical research. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101952. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlund MW, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Silk JS, Cataldo MF, Forbes EE, Dahl RE, & Ryan ND (2010). Nothing to fear? Neural systems supporting avoidance behavior in healthy youths. NeuroImage, 52(2), 710–719. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servatius RJ (2016). Avoidance: From basic science to psychopathology. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 10. 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass JE, Albano AM, Simpson HB, Carpenter K, Schebendach J, & Attia E (2012). Fear of food as a treatment target: Exposure and response prevention for anorexia nervosa in an open series. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(4), 615–621. 10.1002/eat.20936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass JE, Glasofer DR, Dalack M, & Attia E (2020). Between wellness, relapse, and remission: Stages of illness in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(7), 1088–1096. 10.1002/eat.23237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass JE, Sysko R, Glasofer D, Albano AM, Simpson HB, & Walsh BT (2011). Rationale for the application of exposure and response prevention to the treatment of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(2), 134–141. 10.1002/eat.20784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass JE, Sysko R, Schebendach J, Broft A, Strober M, & Walsh BT (2007). The application of exposure therapy and D-Cycloserine to the treatment of anorexia nervosa: A preliminary trial. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 13(4), 238–245. 10.1097/01.pra.0000281484.89075.a8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M (2004). Pathologic fear conditioning and anorexia nervosa: On the search for novel paradigms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35(4), 504–508. 10.1002/eat.20029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir DI, & Hughes BL (2018). Social rewards: From basic social building blocks to complex social behavior. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(6), 700–717. 10.1177/1745691618776263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapletti A, & Hornik K (2022). tseries: Time Series Analysis and Computational Finance. (0.10–51.) [Computer software] https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tseries.

- Treasure J, Cardi V, & Kan C (2012). Eating in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 20(1), e42–e49. 10.1002/erv.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, & Ebner-Priemer UW (2009). Using experience sampling methods/ecological momentary assessment (ESM/EMA) in clinical assessment and clinical research: Introduction to the special section. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 457–462. 10.1037/a0017653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzhula IA, Sala M, Christian C, Hunt RA, Keshishian AC, Wong VZ, Ernst S, Spoor SP, & Levinson CA (2020). Avoidance coping during mealtimes predicts higher eating disorder symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, eat.23254. 10.1002/eat.23254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildes JE, Ringham RM, & Marcus MD (2010). Emotion avoidance in patients with anorexia nervosa: Initial test of a functional model. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(5), 398–404. 10.1002/eat.20730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe J (1969). The Practice of Behavior Therapy. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzus C, & Neubauer AB (2022). Ecological momentary assessment: A meta-analysis on designs, samples, and compliance across research fields. Assessment, 10731911211067538. 10.1177/10731911211067538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.