Abstract

Prenatal alcohol exposure is the leading nongenetic cause of human intellectual impairment. The long-term impacts of prenatal alcohol exposure on health and well-being are diverse, including neuropathology leading to behavioral, cognitive, and emotional impairments. Additionally negative effects also occur on the physiological level, such as the endocrine, cardiovascular, and immune systems. Among these diverse impacts is sleep disruption. In this review, we describe how prenatal alcohol exposure affects sleep, and potential mechanisms of those effects. Furthermore, we outline the evidence that sleep disruption across the lifespan may be a mediator of some cognitive and behavioral impacts of developmental alcohol exposure, and thus may represent a promising target for treatment.

Keywords: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, NREM sleep, Sleep homeostasis, Insomnia, sleep-dependent memory consolidation

1. INTRODUCTION

Prenatal alcohol exposure is the leading nongenetic cause of human intellectual impairment (O’Leary et al., 2013; Siegel et al., 2020), with current estimates of the rate of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) near 5% among school children (May et al., 2018) despite high rates of under and missed diagnoses (Chasnoff et al., 2015). The neural and behavioral outcomes of prenatal alcohol exposure in both humans and animal models are shaped by the intensity, frequency and timing of exposure, as well as risk- and protective-factors derived from genetic variation, maternal health, and postnatal environment (Bandoli et al., 2023; Kable and Jones, 2023; Mead and Sarkar, 2014; Popova et al., 2023; Price et al., 2017; Riley and McGee, 2005). In alignment with the “Developmental Origins of Health and Disease” (DOHaD) concept (Gluckman and Hanson, 2004), prenatal alcohol exposure can create an adverse intrauterine environment that negatively alters the developmental trajectory, putting the individual on a pathway to pathology (Moore and Riley, 2015; Streissguth et al., 2004). Indeed, the long-term impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on health and well-being are diverse including neuropathology leading to behavioral, cognitive and emotional impairments, but also including endocrine (Keiver et al., 2015; Lam et al., 2018; McLachlan et al., 2016), cardiovascular (Lunde et al., 2016), and immune (Raineki et al., 2017) system dysfunction. Importantly, early identification and treatment can significantly improve long-term outcomes (Fagerlund et al., 2011; Kodituwakku, 2010; Rangmar et al., 2015; Temple et al., 2021). Indeed, postnatal experience can strongly shape neural, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes of prenatal alcohol exposure (Ernst et al., 2022; Hemingway et al., 2020; Uban et al., 2020; Wozniak et al., 2015), though there are still relatively few interventions for improving the life-long outcomes of developmental alcohol exposure. In this review, we outline the evidence that sleep disruption across the lifespan may be a mediator of some cognitive and behavioral impacts of developmental alcohol exposure, and thus may represent a promising target for treatment.

2. NEUROBEHAVIORAL AND HEALTH OUTCOMES OF DEVELOPMENTAL ALCOHOL EXPOSURE

2.1. Neuroanatomical outcomes

Both clinical and preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that the central nervous system (CNS) is particularly vulnerable to the teratogenic effects of alcohol (Figure 1). In clinical studies, a common finding is that prenatal alcohol exposure leads to a decrease in the overall brain volume, as well as smaller volumes of both white and grey matter across the entire brain (Boateng et al., 2023; Donald et al., 2015; Lebel et al., 2011; Mattson et al., 2019). Examination of the corpus callosum, the largest white matter tract responsible for the communication between the two hemispheres, revealed that prenatal alcohol exposure can result in a range of effects, from the total absence of the corpus callosum to reduced volume or alterations in its shape (Astley et al., 2009b; Boateng et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 1996; Riley et al., 1995; Sowell et al., 2001; Subramoney et al., 2022; Uban et al., 2020). Deep grey matter structures are also vulnerable to the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure, as studies have shown smaller hippocampus, basal ganglia, caudate nucleus, amygdala, and thalamus in exposed individuals compared to controls (Archibald et al., 2001; Boateng et al., 2023; Donald et al., 2016; Nardelli et al., 2011; Willoughby et al., 2008).These prenatal alcohol-related changes in brain structure may set the stage for the myriad of brain activation abnormalities reported, ranging from global to neurocircuitry-specific deficits (Astley et al., 2009a; Malisza et al., 2005; Santhanam et al., 2009; Sowell et al., 2007; Ware et al., 2021; Wozniak et al., 2017).

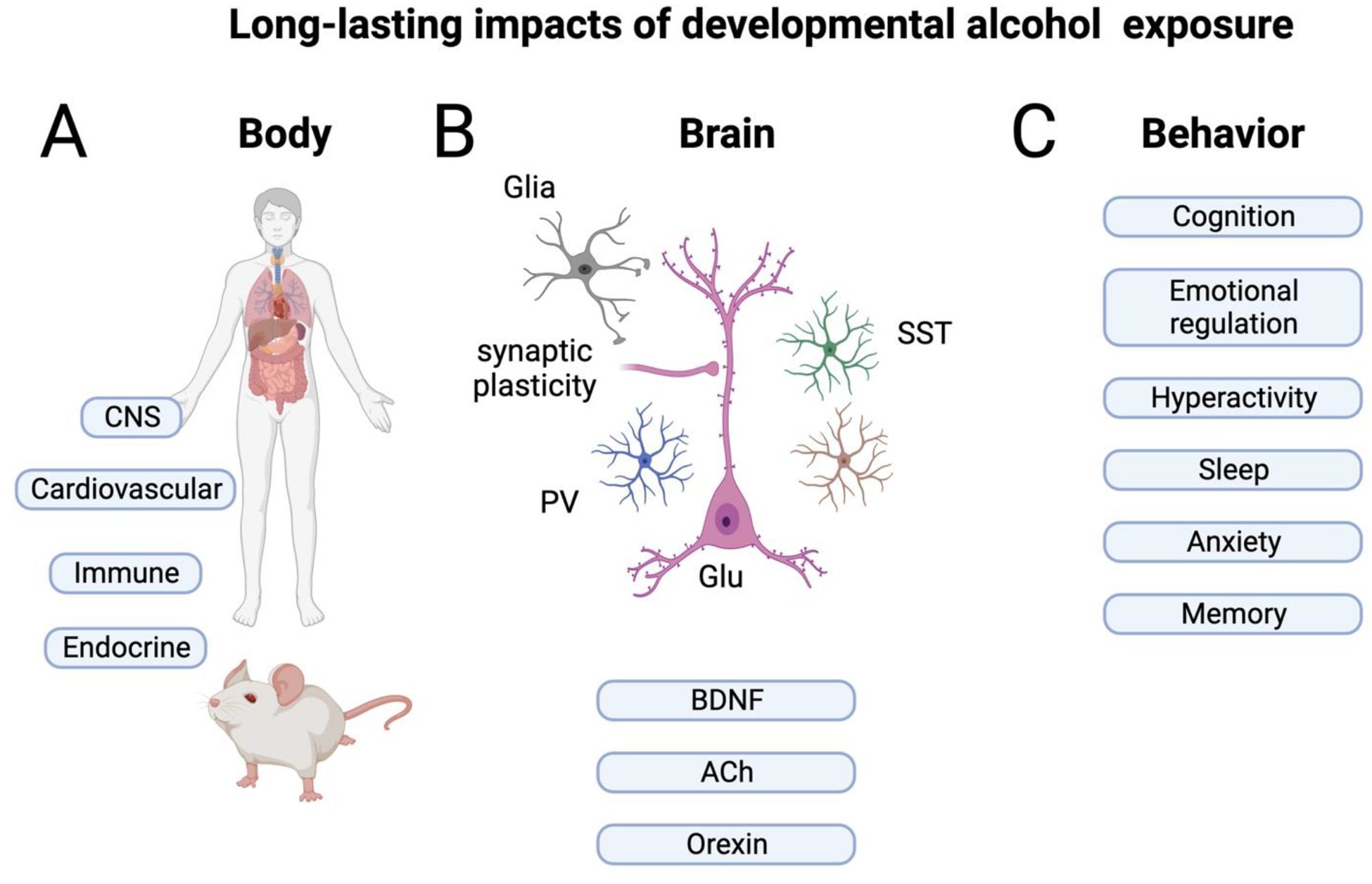

Figure 1.

A) Prenatal alcohol exposure has impacts throughout the body and brain in both humans and animal models. B) In the brain, both glutamatergic (Glu) neurons and GABAergic neurons, including those expressing parvalbumin (PV) and somatostatin (SST) are impacted. Glial cells are also modified both anatomically and functionally. In addition, both growth factors such as Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and neuromodulators such as acetylcholine (ACh) and orexin are modified, all of which may impact sleep-wake states. While other cells and systems may be impacted, those listed here are most relevant for sleep/wake cycling. C) Finally, these biological changes contribute to a wide range of behavioral, cognitive and emotional symptoms, including sleep disturbances. Created with BioRender.com

Preclinical studies of prenatal alcohol exposure vary widely in route of administration, dose, and timing (e.g., acute vs chronic, gestational age), and can also vary in the extent of caloric/nutritional control in comparison groups (for excellent reviews on diversity of animal models of prenatal alcohol exposure see (Marquardt and Brigman, 2016; Petrelli et al., 2018)). Thus, both the magnitude and nature of neurobehavioral changes induced by developmental alcohol can be impacted by the dose and timing of the exposure (e.g., (Maier et al., 1999; Sadrian et al., 2014)). These different models may be useful for insights relevant to clinical translation to highlight different impacts of, for example, binge drinking versus chronic consumption and different developmental stages.

Despite this diversity in protocol details, rodent models have corroborated the clinical findings, demonstrating that developmental alcohol exposure is linked to a reduction in overall brain volume (Coleman et al., 2012; Leigland et al., 2013; Nakano et al., 2023; Parnell et al., 2009). Furthermore, rodent models have also demonstrated that developmental alcohol exposure induces reductions in the volume of cortical and several deep grey matter structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, caudate, putamen, amygdala, hypothalamus, and thalamus (Archibald et al., 2001; Coleman et al., 2012; Nakano et al., 2023; Parnell et al., 2009; Smiley et al., 2019). These decreases in volume are due to loss of neurons, dendritic and synaptic pruning, as well as glial cell loss across many brain regions (Climent et al., 2002; Delatour et al., 2020; Gursky et al., 2019; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Olney et al., 2002a; Olney et al., 2002b; Saito et al., 2010; Saito et al., 2007; Smiley et al., 2023; Smiley et al., 2019; Wozniak et al., 2004; Young and Olney, 2006) (Figure 1B). Depending on the age of exposure, GABAergic inhibitory interneurons appear to be especially affected (Kenton et al., 2020; Madden et al., 2020; Smiley et al., 2015) leading to changes in excitation/inhibition balance (Sadrian et al., 2013a). Indeed, both clinical and preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that the negative effects of prenatal alcohol exposure are widespread, affecting most areas of the brain.

2.2. Behavioral outcomes

The prenatal alcohol-induced structural and functional alterations in the CNS may underlie the widespread behavioral and cognitive changes observed in clinical studies (Jacobson et al., 2021; Kable et al., 2016; Kully-Martens et al., 2012; Mattson et al., 2019; Rasmussen, 2005) (Figure 1C). Individuals with prenatal alcohol exposure often display cognitive deficits across various domains. The most common finding being an overall impairment in general intelligence as individuals with FASD can show lower average IQ scores compared to controls (Mattson et al., 1997; Streissguth et al., 1996). Executive function is notably impaired in individuals with FASD (Rasmussen, 2005). Indeed, children with prenatal alcohol exposure demonstrate lower performance on verbal fluency tasks (Kodituwakku et al., 2006; Schonfeld et al., 2001), exhibit problems with response inhibition (Connor et al., 2000; Mattson et al., 2019), struggle with planning and problem-solving tasks (Green et al., 2009; Kodituwakku et al., 1995), and show deficits in working memory (Green et al., 2009; Kodituwakku et al., 1995). Learning and memory domains are significantly impaired following prenatal alcohol exposure; notably, these impairments persist even when controlling for IQ (Coles et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2015; Willoughby et al., 2008). Prenatal alcohol exposure also adversely impacts language skills, leading to deficits in articulation, grammar, as well as both expressive and receptive language (Becker et al., 1990; Church et al., 1997; Thorne, 2017). Not surprising, children with FASD often struggle in academic settings, experiencing difficulties in mathematics, spelling, and reading (Glass et al., 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2011). Importantly, these behavioral and cognitive challenges often persist into adulthood, affecting various aspects of daily life and decrease life quality (Lynch et al., 2015; McLachlan et al., 2020; Shapiro et al., 2023).

Using various animal models of developmental alcohol exposure, the preclinical literature has replicated the cognitive impairments described in the clinical literature (Harvey et al., 2019; Marquardt and Brigman, 2016). Indeed, rodent models have consistently shown that developmental alcohol exposure induces deficits in spatial memory tasks such as the Morris water maze (An and Zhang, 2013; Wagner et al., 2014), the Barnes maze (Kleiber et al., 2011), and the radial-arm maze (Reyes et al., 1989), tests that can provide clues to human working memory function. Importantly, many of these deficits become more apparent with the increasing difficulty/demands of the task (Brady et al., 2012; Savage et al., 2010). Other forms of cognitive function are also negatively affected by developmental alcohol exposure, including decreased freezing in trace fear conditioning (Brady et al., 2012; Hunt et al., 2009), decreased freezing in contextual fear conditioning (Apuzzo et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2016), disrupted eye-blink conditioning (Green et al., 2002; Tran et al., 2007), impaired novel object recognition (Shirasaka et al., 2012), and reduced cognitive control in the 5-choice serial reaction time task (Olguin et al., 2023; Olguin et al., 2021). These tests can provide clues to human cognitive deficits seen following prenatal alcohol exposure.

In clinical studies, prenatal alcohol-related social behavior deficits are also documented across the lifespan (Kully-Martens et al., 2012). In early development, alcohol-exposed infants exhibit disorganized attachment and reduced “social monitoring” behaviors towards the caregiver (Jirikowic et al., 2016; O’Connor et al., 1992). These social deficits persist into adolescence and adulthood, indicated by poor performance in various social behavior assessments, unresponsiveness to social cues, difficulties in establishing friendships, and an increased likelihood of disrupted school experiences and legal problems (Kully-Martens et al., 2012; Olson et al., 1998; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Streissguth et al., 1996). Animal models of developmental alcohol exposure have replicated several of the social behavioral deficits observed in clinical studies (Kelly et al., 2009). Prenatal alcohol exposure disrupts mother-pup attachment, resulting in increased latency to nipple attach, reduced overall time spent nipple attached, and increased vocalizations (Barron et al., 2000; Marino et al., 2002; Raineki et al., 2017). Developmental alcohol-related social deficits persist into adolescence and adulthood, with disruptions in play behavior (Holman et al., 2019; Mooney and Varlinskaya, 2011) impaired social interaction (Hamilton et al., 2010; Hellemans et al., 2010; Mooney and Varlinskaya, 2011), diminished social motivation (Diaz et al., 2016), and altered social memory recognition (Holman et al., 2018; Holman et al., 2021) indicating that the effects of developmental alcohol exposure on social behavior endure throughout the lifespan in both humans and nonhuman animals.

2.3. Developmental alcohol exposure and health

Clinical research has shown that approximately 90% of individuals with FASD will experience some form of mental health problem, including depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and other mood and behavioral disorders, such as bipolar and conduct disorder (Coles et al., 2022; Himmelreich et al., 2020; O’Connor and Paley, 2009; O’Connor et al., 2002; Pei et al., 2011). These psychopathologies manifest as early as the toddler and childhood years and persist into adulthood, with increasingly aggravating symptoms (Coles et al., 2022; Steinhausen and Spohr, 1998). Rodent studies, using various models of developmental alcohol exposure, are in line with clinical findings suggesting that developmental alcohol exposure is associated with emotional dysregulation (Hellemans et al., 2010). Increased anxiety-like behaviors following prenatal alcohol exposure are observed across several behavioral tasks, including the elevated plus maze (Brocardo et al., 2012; Cullen et al., 2013; Hellemans et al., 2008; Oubraim et al., 2022), the light-dark emergence box (Cullen et al., 2013; Lam et al., 2018), and the open field (Lam et al., 2018; Raineki et al., 2016). Increased depressive-like behaviors in prenatal alcohol exposed animals are observed in the forced swim test (Brocardo et al., 2012; Raineki et al., 2016) and social behavior (Boschen et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2000; Meyer and Riley, 1986). Additionally, prenatal alcohol exposure increases vulnerability to substance abuse/use-like behaviors, including an enhanced preference for alcohol (Barbier et al., 2009), increased voluntary alcohol consumption (Chotro et al., 2007; Fabio et al., 2013), and an increased learning of drug-associated cues in the conditioned place preference paradigm (Barbier et al., 2009; Spear and Molina, 2005; Wang et al., 2019).

Despite the overwhelming number of studies focusing on the negative effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the brain and behavior, FASD has recently been recognized as a “whole-body” disorder (Figure 1A) (Himmelreich et al., 2020). Indeed, prenatal alcohol exposure has been associated with a plethora of physical health problems, including cardiovascular issues (e.g., congenital heart defects, hypertension, and cardiomyopathy) (Cook et al., 2019; Himmelreich et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2019a; Reid et al., 2021), endocrine/metabolic disturbances (e.g., type 2 diabetes, low HDL, high triglycerides, and thyroid hormone dysregulation) (Akison et al., 2019; Himmelreich et al., 2020; Kable et al., 2021; Reid et al., 2021; Weeks et al., 2020) - though see (Amos-Kroohs et al., 2018), changes in the gut microbiome (Bodnar et al., 2022; Upreti et al., 2023), cancers (Gottesfeld and Abel, 1991; Latino-Martel et al., 2010), kidney problems (Himmelreich et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2021), and immune/autoimmune issues (e.g., chronic ear infection, asthma, allergies, and rheumatoid arthritis) (Gauthier et al., 2005; Himmelreich et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2019b). Importantly, dysregulation of the immune and stress regulatory systems are known to be key mechanistic drivers of many of the diseases/disorders that have a higher prevalence following prenatal alcohol exposure (Duan et al., 2019; Gold, 2015; Moss and Blaser, 2005; Neeck et al., 2002; Pradhan et al., 2001; Raff and Magill, 2016). Not surprisingly, both the clinical and preclinical literature have demonstrated that developmental alcohol exposure affects the development and function of the immune (Bodnar et al., 2023; Bodnar et al., 2016; Bodnar et al., 2020; Drew and Kane, 2014; Raineki et al., 2017) and stress systems (Keiver et al., 2015; Lam et al., 2018; McLachlan et al., 2016; Raineki et al., 2018; Raineki et al., 2019).

Recognizing the critical role that sleep plays in various aspects of health, neurobehavioral functioning, cognition, and emotional well-being, this review aims to explore the potential impact of developmental alcohol-related sleep issues on the many health, neurobehavioral, cognitive, and emotional challenges described above.

3. SLEEP AND INSOMNIA

Sleep is a state of reduced physical and cognitive activity that is expressed in most if not all animals. While the overall temporal structure of sleep can vary widely across animals, with for example rodents sleeping in short bouts of a few minutes and humans sleeping in bouts generally of many hours, quality sleep is critical for optimal functioning of the body and brain. In mammals, impaired sleep due to insomnia (i.e., weakened ability to fall or stay asleep, or having low quality sleep) or imposed sleep deprivation is associated with modifications of neural circuit function and negative cognitive and emotional outcomes such as memory impairment, attention deficits, poor emotional regulation, anxiety, and depression (Fernandes et al., 2021; Jamieson et al., 2020; Krause et al., 2017; Tarokh et al., 2016). In fact, nearly all neuropsychiatric disorders have some link with sleep dysfunction (Wulff et al., 2010) and nearly half of all individuals reporting sleep problems also meet criteria for one or more Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV (Roth et al., 2006). Beyond the brain, sleep loss is also associated with more general changes in physiology including poor cardiometabolic outcomes, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes (Dejenie et al., 2022; Pigeon, 2010).

Sleep allows neural circuits to adapt to and assess the activities that occurred during the previous awake period, restore optimal conditions for the next awake period, and efficiently eliminate metabolic waste that could impede function or lead to disorders (Bushey et al., 2011; Goldstein and Walker, 2014; Hobson and Pace-Schott, 2002; Stickgold and Walker, 2007; Tononi and Cirelli, 2014). During wakefulness, neural activity can strengthen the connections between co-active neurons, which is a common way of storing information. However, not all of these strengthened synapses carry useful information, and excessive strengthening can reduce the capacity of circuits. Sleep addresses these issues through two functions. First, it consolidates and strengthens the synapses and circuits involved in storing important memories (Brodt et al., 2023; Diekelmann and Born, 2010; Klinzing et al., 2019; Stickgold et al., 2001), allowing for long-term storage. Second, it resets synaptic changes that are unrelated to significant events, bringing them back to an optimal range and preparing them for the next awake period (Tononi and Cirelli, 2014). This sleep-dependent synaptic change occurs both in adults (Vyazovskiy et al., 2011) and neonatal brains (de Vivo et al., 2019). Sleep also facilitates the removal of metabolic waste from the brain, particularly through the glymphatic system, which increases the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and aids in waste removal (Rasmussen et al., 2022; Shokri-Kojori et al., 2018).

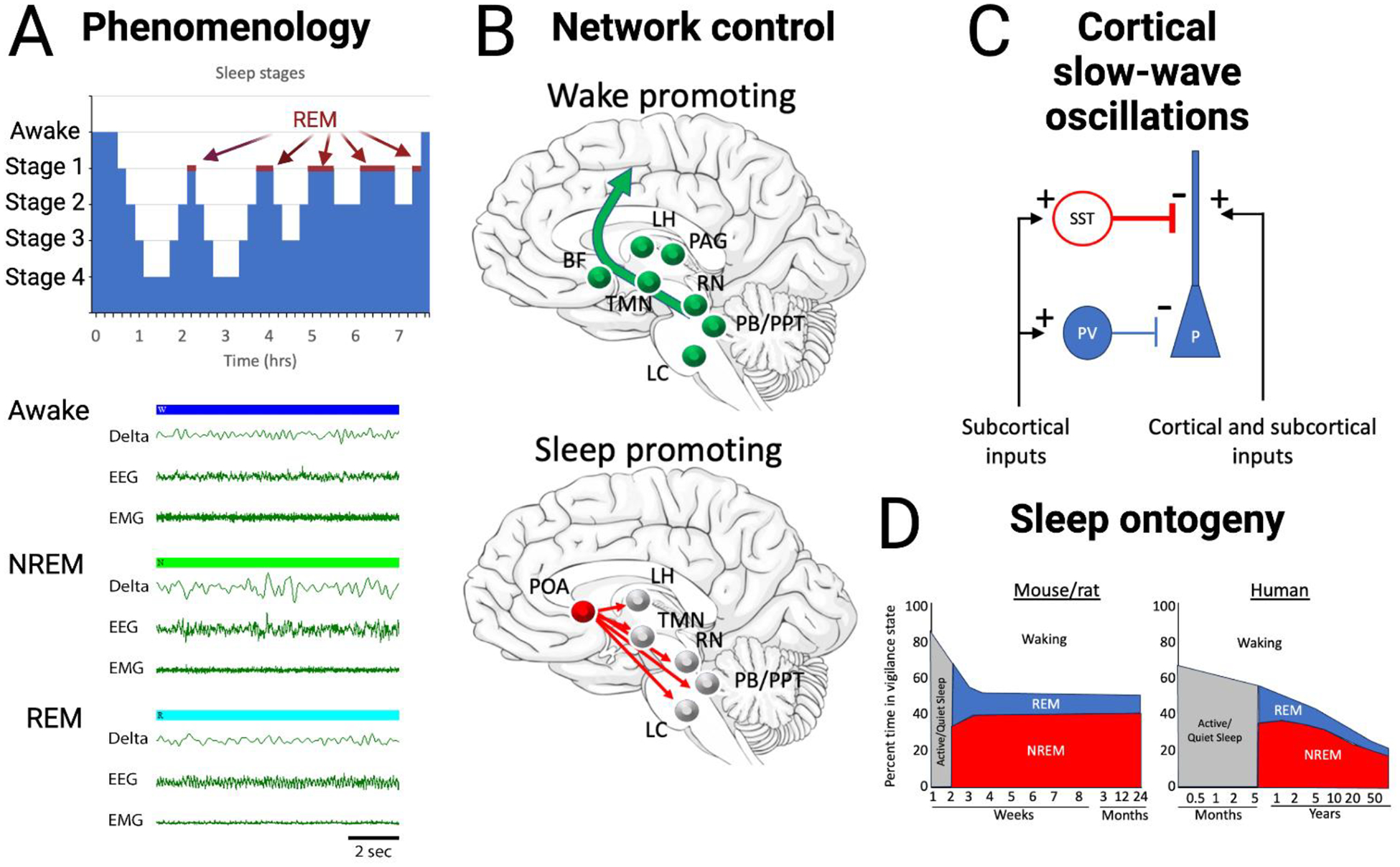

Sleep consists of different stages characterized by cortical and motor activity. These stages contribute differently to sleep-related functions and modulate sensitivity to sensory input (Adamantidis et al., 2019; Lewin et al., 2019b). In humans, the brain transitions from wakefulness to Stage 1 and 2 sleep at the beginning of the night, which are lighter sleep stages characterized by theta band oscillations and sleep spindles (Figure 2A) (Hobson and Pace-Schott, 2002). Slow-wave sleep represents the deepest sleep and, as the name implies, is characterized by large delta wave (1–4Hz) cortical oscillations. Finally, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is characterized by eye movements and reduced muscle tone elsewhere in the body (Hobson and Pace-Schott, 2002). During REM sleep, cortical activity resembles that of wakefulness with low-amplitude, high-frequency oscillations. Collectively, Stages 1–2 and slow-wave sleep are known as non-REM (NREM) sleep. Throughout a typical night’s sleep in humans, the brain cycles between NREM and REM sleep stages multiple times before waking up in the morning.

Figure 2.

A) Sleep and wake states, in both humans and animal models, can be divided into waking, NREM sleep and REM sleep states based on EEG and EMG activity. Waking is characterized by high frequency cortical oscillations and high levels of EMG activity. NREM activity is characterized by high levels of slow-wave and delta band oscillations and reduced EMG activity. REM sleep is characterized by high frequency cortical activity similar to that in waking and very low EMG activity. Recordings displayed are from rat. B) Circuit schematic of networks controlling in sleep and waking. Primary contributors promoting waking are the excitatory projections from the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) and the parabrachial nucleus (PB) to basal forebrain (BF) which broadly projects throughout neocortex. Lateral hypothalamic (LH) neurons contribute to inhibition of sleep promoting regions. Dopamine release by the periaqueductal grey (PAG) area promotes waking, while histamine from the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN), serotonin from the raphe nucleus (RN) and norepinephrine from the locus coeruleus (LC) have more modulatory roles in promoting cortical arousal. Sleep promoting regions include the preoptic area (POA), specifically the ventrolateral preoptic (VLPO) and median preoptic (MnPO) areas which send GABAergic projections to nodes of the waking system. C) An example of the role of inhibitory interneurons in in sleep features such as slow-waves and delta oscillations. During NREM sleep, subcortical inputs, such as from the claustrum, activate GABAergic interneurons to induce down-states in cortical pyramidal cells, with somatostatin neurons especially critical in this process (Funk et al., 2017; Niethard et al., 2018). D) Summary of the ontogeny of vigilance states in rodents and humans. In both rodents and humans, following an early period of sleep not easily classified as REM or NREM, the percentage of time in REM is relatively high and then reduces as the balance of REM/NREM shifts toward greater NREM. Overall, the amount of time in waking increases with development. Created with BioRender.com based on (Wintler et al., 2020).

Sleep initiation is influenced by multiple factors (Duhart et al., 2023; Hobson and Pace-Schott, 2002; Saper et al., 2010) though two key regulators are sleep pressure, a homeostatic process resulting from a period of wakefulness (process S), and the circadian rhythm (process C), which modulates sleep based on the time of day (Borbely and Achermann, 1999). Sleep pressure, which increases with the time spent awake increases the likelihood of falling asleep and can also affect sleep physiology. For instance, after a long period of wakefulness, high sleep pressure leads to enhanced delta wave activity during slow-wave sleep compared to sleep with lower sleep pressure (Donlea et al., 2017; Greene et al., 2017). This increase in sleep pressure following sleep deprivation can result in a homeostatic sleep rebound during the post-deprivation period (Borbely and Achermann, 1999; Donlea et al., 2017; Frank, 2021). The sleep rebound can be stage specific (e.g., REM or NREM) depending on the nature of the deprivation (Benington and Heller, 1999; Park and Weber, 2020; Rechtschaffen et al., 1999). Sleep initiation is often preceded by specific behaviors and physiological states (Eban-Rothschild et al., 2017). In rodents this sleep preparatory behavior can be called nesting and in humans is sometimes called sleep hygiene behavior. The mechanisms of sleep preparatory behavior have recently begun to be explored and involve circuits distinct from sleep itself, including neurons in the prefrontal cortex (Tossell et al., 2023), preoptic area, and hypothalamus (Sotelo et al., 2022).

The transitions between wakefulness and sleep, as well as between different sleep stages, and the maintenance of these states, are controlled by neurons and glia in various brain regions, including the basal forebrain, hypothalamus, brainstem, and thalamocortical circuits (Liu and Dan, 2019; Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002; Saper et al., 2010; Weber and Dan, 2016). These circuits can be broadly categorized into wake-promoting circuits, sleep-promoting circuits involved in REM or NREM sleep, and regions that act as switches between these states (Figure 2B). Wake-promoting circuits are most active during wakefulness and can induce arousal when stimulated directly (Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002). They include cholinergic neurons from the brainstem such as the pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei, both cholinergic neurons and glia (Ingiosi et al., 2023) in the basal forebrain, serotonergic neurons in the raphe nucleus, noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus, and orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (Hobson and Pace-Schott, 2002; Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002; Sakurai, 2007; Sulaman et al., 2023). For example, cholinergic tone is elevated during waking and REM sleep, but reduced during slow-wave sleep. Impaired sleep-wake related cholinergic cycling reduces normal sleep-dependent processes such as memory consolidation (Gais and Born, 2004). Furthermore, waking is associated with elevated activity in basal forebrain astrocytes (Ingiosi et al., 2023) These ascending pathways lead to cortical arousal and desynchronized, high-frequency cortical oscillations characteristic of wakefulness.

Sleep-promoting circuits function by suppressing the wake-promoting circuits. The preoptic area, particularly the ventrolateral and median preoptic nuclei, inhibit activity in the brainstem and basal forebrain wake-promoting circuits (Gent et al., 2018; Lazarus et al., 2013; Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002; Redinbaugh et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2018; Saper et al., 2010). The preoptic area can act as a switch between sleep and wake states (Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002; Saper et al., 2010). The basal forebrain nuclei, which contain different types of neurons, also contribute uniquely to the sleep-wake cycle. For example, activation of basal forebrain inhibitory parvalbumin+ neurons can promote wakefulness, while activation of inhibitory somatostatin+ neurons promotes sleep (Xu et al., 2015). The transitions between REM and NREM sleep are controlled by inhibitory circuits in the pons, modulated by monoamines and orexins. REM-off neurons are suppressed by serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons, while REM-on neurons are excited by brainstem cholinergic neurons (Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002; Saper et al., 2010). Thalamic and cortical activity plays a crucial role in generating specific electrographic features of sleep. The slow, delta band oscillations during NREM sleep result from a thalamocortical loop, with cortical neurons alternating between active and suppressed states (Destexhe et al., 2007; Steriade et al., 2001). Cortical sleep spindles, which are brief (1–3sec) 10–15Hz oscillations and occur during slow-wave sleep, have been linked to memory consolidation (Eschenko et al., 2006; Luthi, 2014). Sleep spindles are driven by the thalamic reticular nucleus, a GABAergic group of neurons that project to other thalamic nuclei and receive a strong neocortical excitatory input (Luthi, 2014). For a more thorough description of sleep and sleep mechanisms see (Adamantidis et al., 2019; Cirelli and Tononi, 2011; Liu and Dan, 2019; Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002; Saper et al., 2010; Sulaman et al., 2023).

3.1. Behavioral outcomes of poor sleep

This brief overview of sleep function and mechanisms suggests that high quality sleep is characterized by relatively short sleep onset latency after going to bed in phase with the circadian rhythm, smooth cycling between NREM and REM sleep stages, large amplitude cortical delta oscillations during slow-wave sleep, high sleep spindle density during Stage 2 sleep, and relatively few awakenings during a prolonged, consolidated sleep bout (Goldstein and Walker, 2014; Hobson and Pace-Schott, 2002; Krause et al., 2017). In addition, robust sleep homeostasis as reflected in sleep rebound following a period of sleep deprivation helps maintain normal sleep pressure (Franken and Dijk, 2023; Tononi and Cirelli, 2006). Furthermore, GABAergic, cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons play critical roles in sleep onset and maintenance, sleep stage transitions, and electrographic features of quality sleep (e.g., delta waves and sleep spindles) (Adamantidis et al., 2019; Sulaman et al., 2023). Thus, disruption of any of these sleep features or underlying neural mechanisms could result in impairment of sleep-dependent cognitive, emotional and/or behavioral outcomes and promote or enhance psychopathology.

For example, acute and/or prolonged sleep deprivation in humans is associated with impaired emotional regulation (Ben Simon et al., 2020a; Ben Simon et al., 2020b), increased anxiety (Mughal et al., 2020b; Pace-Schott et al., 2017), impaired memory consolidation (Davidson and Pace-Schott, 2020; Diekelmann and Born, 2010), impaired social behavior (Bian et al., 2022), exacerbated depressive illnesses (Borbely and Wirz-Justice, 1982) and suicidal ideation or behavior (Lopez-Castroman and Jaussent, 2020), increased substance use disorders (Ahrens and Ahmed, 2020), and increased hyperactivity/attention deficit disorders (Al Lihabi, 2023) among many other adverse outcomes. Increasing evidence in both humans and animal models suggests in many cases sleep disorders are causal or at least contribute to these other disorders. Thus, rather than being a simple side-effect of a primary disorder, sleep in fact can be an effective target for therapeutic approaches to these diverse psychopathologies in adults and adolescents (Blanken et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2023; Freeman et al., 2020; Hertenstein et al., 2022).

3.2. Sleep during early development

Importantly, sleep changes over the course of development and aging (Fig. 2D). In many animals including humans, sleep characteristics and mechanisms mature postnatally (Alfoldi et al., 1990; Carskadon, 2011; Davis et al., 1999; Frank et al., 2017; Jouvet-Mounier et al., 1970; Kayser and Biron, 2016; Knoop et al., 2021; Peirano et al., 2003; Wintler et al., 2020). For example, human newborns spend up to 20hrs/day asleep in 2–4hr sleep bouts and REM sleep constitutes a much higher proportion of total sleep time than in adults. As the child matures, total sleep time reduces and sleep becomes more consolidated (e.g., fewer and longer bouts). Furthermore, with maturation the balance between REM and NREM shifts toward predominantly NREM, similar to that of adults. Finally, the amplitude of cortical slow-waves increases from birth to puberty and then decreases over adolescence to adult levels (Ringli and Huber, 2011). These changes in sleep during early development may play critical roles in neural circuit maturation and plasticity (Blumberg et al., 2022).

However, as with many other neural functions that emerge during early development, early life is a sensitive period during which genetic and/or environmental perturbations can modify the emergence and expression of mature sleep (for an excellent overview of developmental vulnerabilities see (Rice and Barone, 2000)). Thus, given the central role of sleep in so many aspects of cognition, emotion and behavior as noted above, disrupting sleep during development can have both immediate and life-long consequences for brain function and behavior (Carskadon, 2011; Jones et al., 2019; Kayser and Biron, 2016; Lewin et al., 2019b; Mindell et al., 1999; Tesler et al., 2013), providing a robust component of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). For example, in humans, early trauma impairs sleep both in the short-term and into adulthood (Bader et al., 2007; Brindle et al., 2018; Chapman et al., 2011; Palagini et al., 2015). Similar lifelong impairment in sleep has been reported in animal models following early life trauma in the context of the mother (Lewin et al., 2019a). Specifically, providing a rat mother with insufficient bedding to make a nest from postnatal day 8–12, which induces pup maltreatment (Doherty et al., 2017; Raineki et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2017), produces later expression of depressive-like behavior, impaired social behavior, and home cage hyperactivity in the pups that extends to adolescence and adulthood (Naeem et al., 2022; Perry and Sullivan, 2014). This adverse early life event also induces NREM sleep fragmentation, delayed developmental decrease in NREM delta amplitude, and decreased sleep spindle density through adulthood. The change in sleep spindle density statistically mediates the abnormal behavioral activity (Lewin et al., 2019a). Similarly, experimentally imposed sleep deprivation during early development in voles induces changes in cortical inhibitory interneurons and affect social bonding in adulthood (Jones et al., 2019), as well as changes in adult REM and NREM sleep expression (Jones-Tinsley et al., 2023). Finally, sleep disruption during early development can disrupt sleep-dependent synaptic homeostasis in infant/adolescent mice during the period critical for normal synaptic development and pruning, and circuit development (de Vivo et al., 2019; Nagai et al., 2021). These sleep-dependent effects can have long-lasting impacts on cortical development (Anastasiades et al., 2022; Billeh et al., 2016).

In summary, early life events can impair sleep for the remainder of life, potentially via changes in neural development and plasticity. In turn, sleep impairment is strongly correlated with, and in some cases mediates adverse cognitive, emotional and/or behavioral outcomes. How does developmental alcohol exposure impact sleep and is sleep impairment related to behavioral outcomes?

4. DEVELOPMENTAL ALCOHOL EXPOSURE AND SLEEP

Developmental alcohol exposure disrupts sleep in humans (Alvik et al., 2011; Chandler-Mather et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2012; D’Angiulli et al., 2006; Ehlers and Criado, 2010; Goril et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2020; Inkelis and Thomas, 2018; Jan et al., 2010; Lund and Ystrom, 2022; Mughal et al., 2020b; Pesonen et al., 2009; Popova et al., 2016; Shang et al., 2006; Troese et al., 2008; Wengel et al., 2011) and other animals (Cadena et al., 2020; Criado et al., 2008; Lewin et al., 2018; Mokashi et al., 2021; Stone et al., 1996; Veatch, 2006; Wilson et al., 2016). In fact, sleep disruption was noted in some of the earliest descriptions of FASD (Abel, 1984). This disruption is present in pre-adolescence and can last into adulthood (Steinhausen and Spohr, 1998). Given the importance of sleep for a myriad of cognitive, emotional and behavioral functions, this lifelong sleep disruption could significantly contribute to diverse developmental alcohol outcomes.

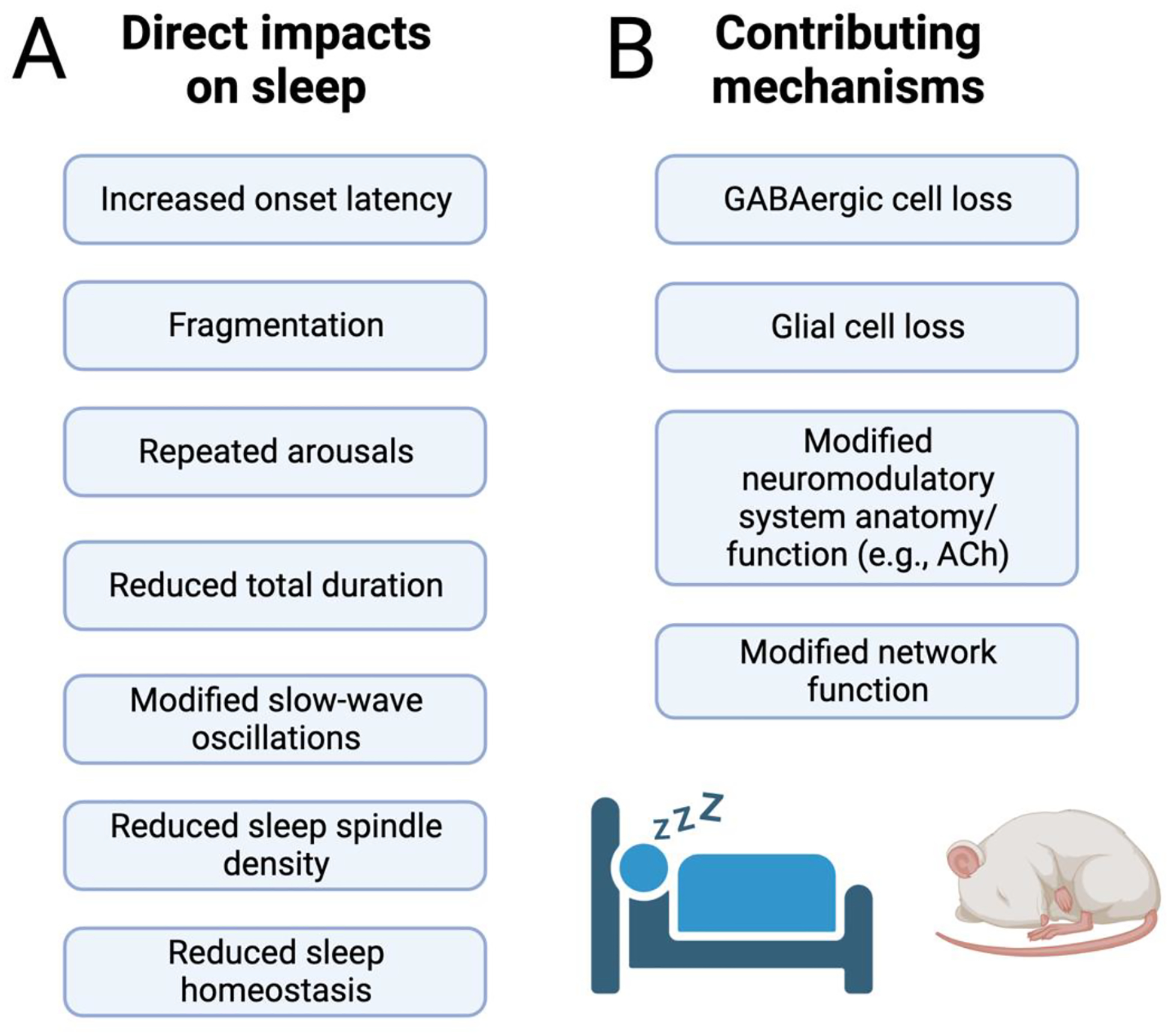

Developmental alcohol exposure impacts a variety of sleep features (Al Lihabi, 2023; Chandler-Mather et al., 2021; Dylag et al., 2021; Hammond et al., 2022; Hanlon-Dearman et al., 2018; Mughal et al., 2020a; Mughal et al., 2020b; Pesonen et al., 2009; Wengel et al., 2011) – for reviews see (Inkelis and Thomas, 2018; Jan et al., 2010). Though there is variation in the nature of sleep assays used, ranging from polysomnography to parental reports, and variation in sleep features assayed, there is currently strong evidence of difficulty falling asleep (Gerstner et al., 2023; Hayes et al., 2020), sleep fragmentation (Chen et al., 2012; Goril et al., 2016; Troese et al., 2008; Wengel et al., 2011), reduced sleep bout duration (Inkelis and Thomas, 2018; Wengel et al., 2011), reduced total sleep duration (Benson et al., 2023; Hayes et al., 2020; Wengel et al., 2011), repeated arousals (Hayes et al., 2020; Inkelis and Thomas, 2018; Wengel et al., 2011), modified slow-wave activity (Havlicek et al., 1977; Inkelis and Thomas, 2018), and reduced sleep homeostasis (Shah et al., 2023), with many of these effects observed in infants, adolescents and/or adults in humans and/or animal models (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A) Summary of the diverse impacts of prenatal alcohol exposure on sleep. Most of these effects have been observed in both humans and animal models. B). Of the diverse impacts of prenatal alcohol exposure on the brain, these specific factors are likely to be the main contributors to sleep disruption. See text for specific examples and details. Created with BioRender.com

For example, children (< 18 years old) prenatally exposed to alcohol have a 3-fold increased risk for short and low efficiency sleep (Pesonen et al., 2009). FASD-associated sleep fragmentation and insomnia have been documented with caregiver surveys, actigraphy, and polysomnography (Alvik et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Inkelis and Thomas, 2018; Ipsiroglu et al., 2019; Jan et al., 2010). Controlling for maternal smoking, commonly associated with alcohol consumption, did not reduce the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on childhood sleep (Chandler-Mather et al., 2021), though the addition of other early adverse events can further exacerbate sleep disturbances (Chandler-Mather et al., 2023).

For comparison, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which impacts a smaller proportion of children as compared to FASD, is also associated with sleep disorders (Humphreys et al., 2014). In fact, insomnia is the second most common comorbidity reported with ASD after epilepsy (Mammarella et al., 2023; Matson and Goldin, 2013). In a direct comparison of children classified as typically developing, having ASD, or having FASD, children with FASD showed impaired sleep duration either similar to ASD (Mughal et al., 2020a) or significantly worse than ASD (Benson et al., 2023), and both were reduced from that of typically developing children.

Preclinical rodent studies, using a variety of developmental alcohol exposure paradigms, have found similar disruptions of sleep duration and quality. These studies have primarily relied on electrophysiological recordings though video analyses of behavior (Ipsiroglu et al., 2019) have detected similar results. For example, pregnant rats fed alcohol diet from gestational day 8 through parturition gave birth to pups that showed a significant decrease in REM sleep at 6 months old, compared to iso-caloric pair-fed controls (Stone et al., 1996). Following intra-gastric alcohol exposure during postnatal days 4–9, to mimic third trimester human exposure, alcohol-exposed adults rats showed increased latency to initiate REM and NREM sleep bouts and an overall reduction in total duration of REM sleep, with a trend toward reduced NREM duration compared to sham controls (Volgin and Kubin, 2012). Similarly, adolescent rats exposed in utero to alcohol from conception to gestation day 21 (birth at day 22–23) via an alcohol diet fed to the pregnant female showed abnormally prolonged latency to sleep, sleep fragmentation and reduced total sleep time compared to offspring of mothers fed an isocaloric diet (Ipsiroglu et al., 2019). As a final example, adult mice exposed to alcohol injections on postnatal day 7 (P7) in a model of human third trimester binge exposure showed reduced time in NREM sleep, NREM sleep fragmentation, reduced sleep spindle density, and reduced slow-wave activity (cortical delta band oscillation amplitude) compared to saline-injected controls (REM sleep was not assessed in these studies) (Apuzzo et al., 2020; Lewin et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2016).

All of these diverse models reveal a strong impact of prenatal/perinatal alcohol exposure on various aspects sleep, with effects emerging in infancy and continuing throughout the lifespan. Similar results were observed after adolescent alcohol exposure in rats. Rats were exposed to alcohol vapor for 12 hr/day for 5 weeks during adolescence, and then assayed for sleep characteristics after 5 weeks of withdrawal. Alcohol-exposed rats showed NREM sleep fragmentation and reduced total time in NREM sleep compared to no exposure controls, similar to that observed following perinatal exposure (Criado et al., 2008; Ehlers and Criado, 2010). However, in these animals delta band activity was enhanced in the alcohol animals (Criado et al., 2008), as opposed to the decrease observed in P7 binge-exposed mice (Apuzzo et al., 2020). It should be noted that in addition to these rodent studies, developmental alcohol exposure also impairs sleep in Drosophila (Mokashi et al., 2021) and zebrafish (Cadena et al., 2020) compared to no alcohol exposure controls.

These developmental alcohol exposure-induced changes in sleep in animal models have also been tied to cognitive/behavioral outcomes. In the P7 binge model just described, alcohol exposed animals showed reduced time in NREM sleep, reduced NREM bout duration, and increased numbers of slow-wave to fast wave transitions over a 24hr period compared to saline controls (Wilson et al., 2016). These NREM effects were observed during both the light and dark phases of the 24hr day. In addition, adult cortical delta oscillation amplitude and sleep spindle density were also decreased by P7 alcohol (Apuzzo et al., 2020). Reductions in delta oscillations have been linked to impaired sleep quality, including reduced sleep-dependent memory consolidation and adverse cognitive/emotional outcomes (Harmony, 2013; Khatami et al., 2007; Mander et al., 2013; Molle and Born, 2011). Similarly, cortical spindle density has been linked to memory and cognition (Cowan et al., 2020; Molle et al., 2009). In fact, the magnitude of sleep impairment in adults exposed to P7 alcohol significantly correlated with contextual fear conditioning memory – worse cognitive performance correlated with poorer sleep (Wilson et al., 2016). Importantly, these effects on sleep, as well as cognitive behavior and neuroanatomy, could be prevented by lithium chloride exposure at the time of P7 alcohol exposure (Lewin et al., 2018) or reversed by later life exercise and environmental enrichment (Apuzzo et al., 2020). Similarly, rats in the maternal alcohol diet from gestational day 8 through parturition model showed impaired spontaneous alternation as adults which strongly correlated with the observed impairment in REM sleep (Stone et al., 1996).

Together, these results suggest that in both humans and animal models, developmental alcohol exposure induces long-lasting impairments in diverse metrics of sleep quantity and quality, and these impairments in sleep can correlate with cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

4.1. Potential mechanisms of developmental alcohol impacts on sleep

There are a variety of potential mechanisms for developmental alcohol’s impact on life-long sleep. First, as noted above, sleep-wake cycling, sleep architecture and local neural network function during sleep are all dependent on GABAergic neuron activity in diverse brain regions (Chowdhury et al., 2019; Krishnan et al., 2016; Ognjanovski et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2015). Indeed, brainstem (Anaclet et al., 2014) and basal forebrain (Saper et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2015) GABAergic neurons mediate sleep/wake state switching, hippocampal GABAergic interneurons modulate activity during NREM that is critical for sleep-dependent memory consolidation (Ognjanovski et al., 2017), and cortical GABAergic interneurons contribute to slow-wave activity (Funk et al., 2017; Niethard et al., 2018). Even sleep preparatory behaviors like nesting are dependent on prefrontal cortical somatostatin (SST+) GABAergic neurons (Tossell et al., 2023). Recent work suggests that developmental alcohol exposure is especially harmful to GABAergic neurons in multiple brain regions (Sadrian et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2019; Smiley et al., 2015), even in moderate doses (Kenton et al., 2020; Madden et al., 2020), and disrupts local circuit excitation/inhibition balance (Delatour et al., 2020; Sadrian et al., 2014; Sadrian et al., 2013b).

As a specific example, cortical GABAergic neurons expressing SST are involved in cortical slow-waves occurring during slow-wave sleep (Figure 2C) (Funk et al., 2017; Niethard et al., 2018). These neurons are reduced by developmental alcohol exposure in mice (Smiley et al., 2019). Optogenetic excitation of frontal cortex SST+ neurons evokes cortical slow-waves that propagate to posterior cortex, similar to naturally occurring slow-waves (Funk et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2023). Furthermore, closed-loop stimulation of SST+ neurons in phase with naturally occurring cortical slow-waves, enhances cortical delta oscillation power (Wilson et al., 2023). Neither of these effects are observed in adult mice that were developmentally exposed to alcohol (Wilson et al., 2023), suggesting a strong link between alcohol-induced loss of SST+ neurons and observed decreases in slow-wave activity.

Developmental alcohol can also impact neuromodulators involved in sleep and arousal, such as acetylcholine and serotonin (Fulginiti et al., 1992; Maier et al., 1996; Milbocker and Klintsova, 2021; Olateju et al., 2017; Smiley et al., 2021). For example, adult mice exposed to binge alcohol on P7 exhibited a loss of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain (40%) and the striatum (12%), although the neurons in the pedunculopontine/lateral dorsal tegmental nuclei of the brainstem were largely spared (Smiley et al., 2021). A similar loss of basal forebrain (nucleus basalis) cholinergic neurons is seen in adult rats exposed to alcohol from P4–9 (Milbocker and Klintsova, 2021). In addition to anatomical changes, function of neuromodulatory systems can also be impacted by developmental alcohol. While Smiley et al, reported no change in serotonergic cell number in the dorsal raphe nucleus in adult mice exposed to developmental alcohol (Smiley et al., 2021), Fulginiti et al. found diminished behavioral responses to serotonin receptor agonists in adult rats exposed to binge alcohol on P8 (Fulginiti et al., 1992). A third neuromodulator known to be involved in sleep/wake function is orexin which has wake-promoting properties (Sakurai, 2007). Developmental alcohol exposure reduces hypothalamic orexinergic cells in the hypothalamus (Smiley et al., 2021), and reduces orexinergic pre-synaptic boutons in the anterior cingulate cortex (Olateju et al., 2017). It is unknown whether other physiological functions of these neuromodulatory neurons are affected by developmental alcohol, such as hypo- or hyperexcitability. Obtaining these kinds of functional data could be informative in relation to sleep. For example, hyperexcitability of orexinergic neurons can lead to sleep fragmentation (Li et al., 2022). Thus, if spared orexinergic neurons were left hyperexcitable due to loss of GABAergic input or membrane properties, this could over-compensate for the reduced numbers and lead to sleep impairment.

A final potential mechanism of impaired sleep following developmental alcohol exposure is modified glial cell structure and/or function. Developmental alcohol affects astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, radial glia, and microglia, in addition to their precursor cells (Guizzetti et al., 2014). In addition to a variety of other functions, glial cells play a critical role in sleep/wake regulation, for example as noted above activation of basal forebrain astrocytes induces wakefulness (Artiushin and Sehgal, 2020; Ingiosi et al., 2023). Developmental alcohol exposure can impact glial cell survival and function (Aghaie et al., 2020; Guizzetti et al., 2014; Rubert et al., 2006; Valles et al., 1996). For example, developmental alcohol impacts oligodendrocyte development and survival, which could have direct effects on myelination. Furthermore, microglial morphology in the VTA is modified by gestational alcohol exposure in rats (Aghaie et al., 2020), potentially impacting dopaminergic system function.

Together, these and other diverse mechanisms could lead not only to disruption of specific sleep features and physiology, but also to impacts on either of the two main processes in sleep/wake regulation – sleep pressure and circadian rhythm. For example, developmental alcohol exposure disrupts circadian/diurnal rhythms (Earnest et al., 2001; Keiver et al., 2015; McLachlan et al., 2016). As noted above, the circadian clock is an important mediator of sleep in humans and other animals, with for example high sleep pressure at the appropriate phase of the circadian rhythm being the most effective for inducing sleep onset (Franken and Dijk, 2023; Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002). At the cellular level, circadian cycles reflect expression of a set of clock genes that vary over 24hr periods and influence the biology of cell within which they are expressed, as well as broader neural and physiological networks in the brain and body (Mohawk et al., 2012). Developmental alcohol exposure from P4–9 modifies clock gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, cerebellum and liver of adult rats (Farnell et al., 2008). This leads to variable behavioral entrainment to light-dark cycles (Allen et al., 2005) which could directly impact sleep. One sleep-related factor regulated by the circadian rhythm is melatonin, which has been shown to display abnormal secretion pattens over a 24-hr period in children with FASD (Goril et al., 2016). Sleep pressure and sleep homeostasis are also impacted by developmental alcohol. In adult mice exposed to alcohol at P7, NREM sleep pressure as assessed by both time spent in NREM sleep and slow-wave activity after a period of sleep restriction is reduced compared to saline-exposed controls (Shah et al., 2023). In fact, while adult saline controls show rebound NREM sleep during the first hr after a 4-hr sleep deprivation period, alcohol-exposed mice continue to stay awake, with only minimal sleep during this immediate post-deprivation period and only returning to baseline levels of NREM sleep over the following hour.

Finally, developmental alcohol impacts brain function at the larger functional network level. In both humans and animal models, functional networks of brain regions have been identified which are active during, and contribute to a variety of behavioral and cognitive functions. For example, in humans resting quietly and thinking about their daily activities, a Default Mode Network is active which involves a group of specific regions that are all functionally coherent, including the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and hippocampus (Raichle et al., 2001). Another identified network is the Salience Network which is active in response to salient, rewarding or potentially biologically relevant stimuli is composed of the insular cortex, ventral striatum and anterior cingulate cortex (Seeley, 2019). Activation of the Salience Network can suppress the Default Mode Network and promote appropriate behavioral responses in humans and animal models (Menon, 2023; Menon et al., 2023). Disruption of normal Salience Network function is associated with insomnia (Khazaie et al., 2017). Recent work in the mouse P7 binge model suggests that developmental alcohol-exposed adult mice express Salience Network functional connectivity similar to that of sleep deprived saline control mice (Shah et al., 2023). Disruption of the Salience Network has also been observed in individuals with FASD (Little et al., 2018). These changes in network function may arise from the developmental alcohol exposure-induced cellular changes described above, and could directly impact sleep and cognition.

In addition to this partial list of direct neural/glial/network mechanisms of sleep impairment, comorbid outcomes of developmental alcohol exposure could also reciprocally interact with sleep. For example, FASD is associated with high anxiety (Mughal et al., 2020b) which can impair sleep and sleep deprivation promotes anxiety (Ben Simon et al., 2020a; Mughal et al., 2020b; Roth et al., 2006). FASD is also associated with substance use/abuse disorders (Moore and Riley, 2015). Substance use and sleep disorders share a similar reciprocal relationship as that of anxiety and sleep (Ahrens and Ahmed, 2020).

Together, these mechanisms may directly or indirectly contribute to long-lasting sleep impairment observed after developmental alcohol exposure. In turn, for reasons outlined in Section III, this sleep impairment may directly contribute to the cognitive, emotional and behavioral outcomes of developmental alcohol exposure. In fact, in animal models, manipulations targeting the neural consequences of developmental alcohol exposure have been shown to improve both sleep and cognitive behavior (Apuzzo et al., 2020; Lewin et al., 2018).

5. SLEEP AS A THERAPEUTIC TARGET

Sleep disorders are comorbid with wide variety of psychiatric, developmental, and neurodegenerative disorders, and therapeutic targeting of sleep is recognized as a treatment and/or preventative for some (Freeman et al., 2020; Wulff et al., 2010). For example, depression is very strongly linked with insomnia, including enhanced latency to sleep onset and sleep fragmentation (Riemann et al., 2020). In adolescents, insomnia can precede the onset of depression symptoms and is believed to contribute to the emergence of depression (Gradisar et al., 2022). Treating insomnia through hormonal and/or cognitive behavioral therapy improves both sleep and depressive symptoms in adolescents (Gradisar et al., 2022). In fact, some evidence exists suggesting treatment of insomnia can serve as a preventative for depression (Riemann et al., 2020). Similarly, sleep disorders are a risk factor for onset of dementia (de Almondes et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018), with high quality NREM sleep serving as a protective factor (Zavecz et al., 2023). These findings have led to the suggestion that targeting impaired sleep may be a preventative or restorative therapy for aging related dementia (Mander et al., 2016). Finally, sleep disorders are common in ASD and other developmental disorders that may have more direct relevance for FASD (Al Lihabi, 2023; Blackmer and Feinstein, 2016; Mammarella et al., 2023; Ogundele and Yemula, 2022). Sleep disorders are the second most common comorbidity with ASD (Mammarella et al., 2023), and play a role in mood, anxiety and other behavioral features of ASD. Sleep treatments in ASD include pharmacology, melatonin, and behavioral therapy, though with each having rather variable efficacy (Blackmer and Feinstein, 2016; Mammarella et al., 2023). Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is also associated with sleep disorders and symptoms are moderately impacted by sleep treatment (Hiscock et al., 2015; Larsson et al., 2023)

Thus, there is growing evidence of 1) sleep being comorbid with, and in some case preceding, a variety of disorders including developmental disorders, and 2) targeting sleep may be an effective intervention and/or preventative of a variety of disorders. Can sleep treatment be effective for some aspects of FASD? Neurobehavioral outcomes of FASD and developmental alcohol exposure models can be impacted by post-exposure environment and treatments ranging from targeting the gut microbiota and nutrition (Ernst et al., 2022; Upreti et al., 2023), to exercise and environmental enrichment (Apuzzo et al., 2020; Caldwell et al., 2015; Fagerlund et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2015; Hannigan et al., 2007; Streissguth et al., 2004), to behavioral and pharmacological therapies (Glass et al., 2023). Thus, although developmental alcohol exposure impairs synaptic plasticity and learning, plasticity-dependent, treatmentbased recovery, at least in some domains is possible.

Thus, treatment of sleep disorders in children with FASD has been shown to be at least partially effective for sleep itself (Hanlon-Dearman et al., 2018). However, there is currently little to no direct evidence of an impact of sleep restoration on improved waking cognitive, emotional and behavioral outcomes (Rigney et al., 2018). Nevertheless, some evidence suggests that improving sleep quality in children with FASD can improve caregiver and family stress, and working memory and executive function in FASD correlate with sleep quality (Chen et al., 2012; Hanlon-Dearman et al., 2018). In animal models of developmental alcohol exposure, adolescent exercise and environmental enrichment restores NREM sleep quality, duration, and sleep spindle density, as well as contextual memory and home cage hyperactivity, though again, these are correlated outcomes and are not directly indicative of a causal relationship (Apuzzo et al., 2020).

6. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While both clinical and preclinical data show strong effects of developmental alcohol exposure on sleep, there are still many issues yet to be resolved. These include:

Sensitivity to the timing, duration and dose of alcohol exposure. Most effects of developmental alcohol exposure are timing- and dose-dependent, thus it is likely to be the same with impacts on sleep. Given that sleep is a multifaceted phenomenon dependent on multiple brain networks, using animal models to relate exposure parameters to specific impact on sleep may help identify mechanisms of sleep disturbance induced by developmental alcohol. Appropriate control groups, for example for caloric or nutritional status are also critical in pre-clinical studies.

Mechanisms of developmental alcohol induced sleep impairment, including identifying the role of specific cell types, brain networks, and brain-body interactions. As in point 1, effects on different aspects of sleep (e.g., sleep spindle density, sleep fragmentation, cortical delta wave amplitude) may be dependent on different mechanisms. This work should include assessments of diurnal and circadian rhythms.

Further define the relationship between sleep impairment and other outcomes of developmental alcohol. As described above, there is evidence now that developmental alcohol’s effects on cognitive, emotional, and behavior outcomes may at least partially be mediated by developmental alcohol’s impacts on sleep. More thorough assessment of this relationship, including direct analysis of causal impacts is required.

The data clearly highlights a need for careful assessment of the impact of sleep targeted therapy, such as light therapy, melatonin treatment, sleep hygiene and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on both sleep and cognitive/emotional/behavioral outcomes of developmental alcohol exposure (Hanlon-Dearman et al., 2018).

Further understanding of the mechanisms of developmental alcohol-induced sleep disturbance may help guide this approach, as will a better understanding of the reciprocal interaction between sleep and cognition.

Highlights.

Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) is the leading nongenetic cause of intellectual impairment

PAE impairs sleep which may directly contribute to cognitive and behavioral outcomes

Sleep may be an effective target for treatment of some aspects of PAE.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from NIAAA (R01AA023181) to DAW, MS, and JFS, a grant from NICHD (R37-HD083217) to RMS, and by grants from NIAAA (R01AA022460) and The Azrieli Foundation to CR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

DAW, RMS, JFS, MS and CR declare that the work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abel EL, 1984. Prenatal effects of alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend 14, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamantidis AR, Gutierrez Herrera C, Gent TC, 2019. Oscillating circuitries in the sleeping brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 20, 746–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghaie CI, Hausknecht KA, Wang R, Dezfuli PH, Haj-Dahmane S, Kane CJM, Sigurdson WJ, Shen RY, 2020. Prenatal ethanol exposure and postnatal environmental intervention alter dopaminergic neuron and microglia morphology in the ventral tegmental area during adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 44, 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens AM, Ahmed OJ, 2020. Neural circuits linking sleep and addiction: Animal models to understand why select individuals are more vulnerable to substance use disorders after sleep deprivation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 108, 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akison LK, Reid N, Wyllie M, Moritz KM, 2019. Adverse Health Outcomes in Offspring Associated With Fetal Alcohol Exposure: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Studies With a Focus on Metabolic and Body Composition Outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43, 1324–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Lihabi A, 2023. A literature review of sleep problems and neurodevelopment disorders. Front Psychiatry 14, 1122344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfoldi P, Tobler I, Borbely AA, 1990. Sleep regulation in rats during early development. Am J Physiol 258, R634–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GC, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ, 2005. Neonatal alcohol exposure permanently disrupts the circadian properties and photic entrainment of the activity rhythm in adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29, 1845–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvik A, Torgersen AM, Aalen OO, Lindemann R, 2011. Binge alcohol exposure once a week in early pregnancy predicts temperament and sleeping problems in the infant. Early Hum Dev 87, 827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos-Kroohs RM, Nelson DW, Hacker TA, Yen CE, Smith SM, 2018. Does prenatal alcohol exposure cause a metabolic syndrome? (Non-)evidence from a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. PLoS One 13, e0199213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An L, Zhang T, 2013. Spatial cognition and sexually dimorphic synaptic plasticity balance impairment in rats with chronic prenatal ethanol exposure. Behav Brain Res 256, 564–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaclet C, Ferrari L, Arrigoni E, Bass CE, Saper CB, Lu J, Fuller PM, 2014. The GABAergic parafacial zone is a medullary slow wave sleep-promoting center. Nat Neurosci 17, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiades PG, de Vivo L, Bellesi M, Jones MW, 2022. Adolescent sleep and the foundations of prefrontal cortical development and dysfunction. Prog Neurobiol 218, 102338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apuzzo J, Saito M, Wilson DA, 2020. Post-exposure environment modulates long-term developmental ethanol effects on behavior, neuroanatomy, and cortical oscillations. Brain Res 1748, 147128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Gamst A, Riley EP, Mattson SN, Jernigan TL, 2001. Brain dysmorphology in individuals with severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Med Child Neurol 43, 148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiushin G, Sehgal A, 2020. The glial perspective on sleep and circadian rhythms. Annu Rev Neurosci 43, 119–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ, Aylward EH, Olson HC, Kerns K, Brooks A, Coggins TE, Davies J, Dorn S, Gendler B, Jirikowic T, Kraegel P, Maravilla K, Richards T, 2009a. Functional magnetic resonance imaging outcomes from a comprehensive magnetic resonance study of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Neurodev Disord 1, 61–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ, Aylward EH, Olson HC, Kerns K, Brooks A, Coggins TE, Davies J, Dorn S, Gendler B, Jirikowic T, Kraegel P, Maravilla K, Richards T, 2009b. Magnetic resonance imaging outcomes from a comprehensive magnetic resonance study of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33, 1671–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader K, Schafer V, Schenkel M, Nissen L, Schwander J, 2007. Adverse childhood experiences associated with sleep in primary insomnia. Journal of sleep research 16, 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandoli G, Hayes S, Delker E, 2023. Low to Moderate Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes: A Narrative Review and Methodological Considerations. Alcohol Res 43, 01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier E, Houchi H, Warnault V, Pierrefiche O, Daoust M, Naassila M, 2009. Effects of prenatal and postnatal maternal ethanol on offspring response to alcohol and psychostimulants in long evans rats. Neuroscience 161, 427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron S, Segar TM, Yahr JS, Baseheart BJ, Willford JA, 2000. The effects of neonatal ethanol and/or cocaine exposure on isolation-induced ultrasonic vocalizations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 67, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Warr-Leeper GA, Leeper HA Jr., 1990. Fetal alcohol syndrome: a description of oral motor, articulatory, short-term memory, grammatical, and semantic abilities. J Commun Disord 23, 97–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Simon E, Rossi A, Harvey AG, Walker MP, 2020a. Overanxious and underslept. Nat Hum Behav 4, 100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Simon E, Vallat R, Barnes CM, Walker MP, 2020b. Sleep loss and the socio-emotional brain. Trends Cogn Sci 24, 435–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benington JH, Heller HC, 1999. Implications of sleep deprivation experiments for our understanding of sleep homeostasis. Sleep 22, 1033–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AA, Mughal R, Dimitriou D, Halstead EJ, 2023. Towards a distinct sleep and behavioural profile of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): A comparison between FASD, Autism and Typically Developing Children. J Integr Neurosci 22, 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian WJ, Brewer CL, Kauer JA, de Lecea L, 2022. Adolescent sleep shapes social novelty preference in mice. Nat Neurosci 25, 912–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeh YN, Rodriguez AV, Bellesi M, Bernard A, de Vivo L, Funk CM, Harris J, Honjoh S, Mihalas S, Ng L, Koch C, Cirelli C, Tononi G, 2016. Effects of Chronic Sleep Restriction during Early Adolescence on the Adult Pattern of Connectivity of Mouse Secondary Motor Cortex. eNeuro 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmer AB, Feinstein JA, 2016. Management of Sleep Disorders in Children With Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Review. Pharmacotherapy 36, 84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanken TF, Borsboom D, Penninx BW, Van Someren EJ, 2020. Network outcome analysis identifies difficulty initiating sleep as a primary target for prevention of depression: a 6-year prospective study. Sleep 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg MS, Dooley JC, Tiriac A, 2022. Sleep, plasticity, and sensory neurodevelopment. Neuron 110, 3230–3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boateng T, Beauchamp K, Torres F, Ruffaner-Hanson CD, Pinner JFL, Vakamudi K, Cerros C, Hill DE, Stephen JM, 2023. Brain structural differences in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and its subtypes. Front Neurosci 17, 1152038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar TS, Chao A, Holman PJ, Ellis L, Raineki C, Weinberg J, 2023. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: linking immune function to mental health status. Front Neurosci 17, 1214100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar TS, Hill LA, Weinberg J, 2016. Evidence for an immune signature of prenatal alcohol exposure in female rats. Brain Behav Immun 58, 130–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar TS, Lee C, Wong A, Rubin I, Wegener Parfrey L, Weinberg J, 2022. Evidence for long-lasting alterations in the fecal microbiota following prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 46, 542–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar TS, Raineki C, Wertelecki W, Yevtushok L, Plotka L, Granovska I, Zymak-Zakutnya N, Pashtepa A, Wells A, Honerkamp-Smith G, Coles CD, Kable JA, Chambers CD, Weinberg J, and the C, 2020. Immune network dysregulation associated with child neurodevelopmental delay: modulatory role of prenatal alcohol exposure. J Neuroinflammation 17, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbely AA, Achermann P, 1999. Sleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulation. J Biol Rhythms 14, 557–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbely AA, Wirz-Justice A, 1982. Sleep, sleep deprivation and depression. A hypothesis derived from a model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol 1, 205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen KE, Hamilton GF, Delorme JE, Klintsova AY, 2014. Activity and social behavior in a complex environment in rats neonatally exposed to alcohol. Alcohol 48, 533–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ML, Allan AM, Caldwell KK, 2012. A limited access mouse model of prenatal alcohol exposure that produces long-lasting deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36, 457–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindle RC, Cribbet MR, Samuelsson LB, Gao C, Frank E, Krafty RT, Thayer JF, Buysse DJ, Hall MH, 2018. The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Poor Sleep Health in Adulthood. Psychosom Med 80, 200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocardo PS, Boehme F, Patten A, Cox A, Gil-Mohapel J, Christie BR, 2012. Anxiety- and depression-like behaviors are accompanied by an increase in oxidative stress in a rat model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Protective effects of voluntary physical exercise. Neuropharmacology 62, 1607–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodt S, Inostroza M, Niethard N, Born J, 2023. Sleep-A brain-state serving systems memory consolidation. Neuron 111, 1050–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushey D, Tononi G, Cirelli C, 2011. Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: structural evidence in Drosophila. Science 332, 1576–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadena PG, Cadena MRS, Sarmah S, Marrs JA, 2020. Folic acid reduces the ethanol-induced morphological and behavioral defects in embryonic and larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a model for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Reprod Toxicol 96, 249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell KK, Goggin SL, Labrecque MT, Allan AM, 2015. The impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on hippocampal-dependent outcome measures is influenced by prenatal and early-life rearing conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39, 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA, 2011. Sleep’s effects on cognition and learning in adolescence. Prog Brain Res 190, 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Wong CYF, Yu BYM, Hui VKY, Ho FYY, Cuijpers P, 2023. Treating depression with a smartphone-delivered self-help cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a parallel-group randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 53, 1799–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler-Mather N, Betts J, Donovan C, Shelton D, Dawe S, 2023. Understanding the impacts of childhood adversity on sleep problems in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A comparison of cumulative and dimensional approaches. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler-Mather N, Occhipinti S, Donovan C, Shelton D, Dawe S, 2021. An investigation of the link between prenatal alcohol exposure and sleep problems across childhood. Drug Alcohol Depend 218, 108412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Wheaton AG, Anda RF, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Liu Y, Sturgis SL, Perry GS, 2011. Adverse childhood experiences and sleep disturbances in adults. Sleep Med 12, 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasnoff IJ, Wells AM, King L, 2015. Misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses in foster and adopted children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Pediatrics 135, 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, Olson HC, Picciano JF, Starr JR, Owens J, 2012. Sleep problems in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Clin Sleep Med 8, 421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotro MG, Arias C, Laviola G, 2007. Increased ethanol intake after prenatal ethanol exposure: studies with animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 31, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Matsubara T, Miyazaki T, Ono D, Fukatsu N, Abe M, Sakimura K, Sudo Y, Yamanaka A, 2019. GABA neurons in the ventral tegmental area regulate non-rapid eye movement sleep in mice. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church MW, Eldis F, Blakley BW, Bawle EV, 1997. Hearing, language, speech, vestibular, and dentofacial disorders in fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21, 227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C, Tononi G, 2011. Molecular neurobiology of sleep. Handb Clin Neurol 98, 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Climent E, Pascual M, Renau-Piqueras J, Guerri C, 2002. Ethanol exposure enhances cell death in the developing cerebral cortex: role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its signaling pathways. J Neurosci Res 68, 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG Jr., Oguz I, Lee J, Styner M, Crews FT, 2012. Postnatal day 7 ethanol treatment causes persistent reductions in adult mouse brain volume and cortical neurons with sex specific effects on neurogenesis. Alcohol 46, 603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Grant TM, Kable JA, Stoner SA, Perez A, Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum, D., 2022. Prenatal alcohol exposure and mental health at midlife: A preliminary report on two longitudinal cohorts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 46, 232–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Lynch ME, Kable JA, Johnson KC, Goldstein FC, 2010. Verbal and nonverbal memory in adults prenatally exposed to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34, 897–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor PD, Sampson PD, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Streissguth AP, 2000. Direct and indirect effects of prenatal alcohol damage on executive function. Dev Neuropsychol 18, 331–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JC, Lynch ME, Coles CD, 2019. Association Analysis: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Hypertension Status in Children and Adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43, 1727–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan E, Liu A, Henin S, Kothare S, Devinsky O, Davachi L, 2020. Sleep spindles promote the restructuring of memory representations in ventromedial prefrontal cortex through enhanced hippocampal-cortical functional connectivity. J Neurosci 40, 1909–1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criado JR, Wills DN, Walker BM, Ehlers CL, 2008. Effects of adolescent ethanol exposure on sleep in adult rats. Alcohol 42, 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen CL, Burne TH, Lavidis NA, Moritz KM, 2013. Low dose prenatal ethanol exposure induces anxiety-like behaviour and alters dendritic morphology in the basolateral amygdala of rat offspring. PLoS One 8, e54924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angiulli A, Grunau P, Maggi S, Herdman A, 2006. Electroencephalographic correlates of prenatal exposure to alcohol in infants and children: a review of findings and implications for neurocognitive development. Alcohol 40, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P, Pace-Schott E, 2020. The role of sleep in fear learning and memory. Curr Opin Psychol 34, 32–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FC, Frank MG, Heller HC, 1999. Ontogeny of sleep and circadian rhythms, in: Turek FW, Zee PC (Eds.), Regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. CRC Press, pp. 45–106. [Google Scholar]

- de Almondes KM, Costa MV, Malloy-Diniz LF, Diniz BS, 2016. Insomnia and risk of dementia in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 77, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vivo L, Nagai H, De Wispelaere N, Spano GM, Marshall W, Bellesi M, Nemec KM, Schiereck SS, Nagai M, Tononi G, Cirelli C, 2019. Evidence for sleep-dependent synaptic renormalization in mouse pups. Sleep 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejenie TA, MT GM, Admasu FT, Adella GA, Enyew EF, Kifle ZD, Seid MA, Mengstie MA, Abebe EC, 2022. Impact of objectively-measured sleep duration on cardiometabolic health: A systematic review of recent evidence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13, 1064969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delatour LC, Yeh PWL, Yeh HH, 2020. Prenatal Exposure to Ethanol Alters Synaptic Activity in Layer V/VI Pyramidal Neurons of the Somatosensory Cortex. Cereb Cortex 30, 1735–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Hughes SW, Rudolph M, Crunelli V, 2007. Are corticothalamic ‘up’ states fragments of wakefulness? Trends Neurosci 30, 334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz MR, Mooney SM, Varlinskaya EI, 2016. Acute prenatal exposure to ethanol on gestational day 12 elicits opposing deficits in social behaviors and anxiety-like behaviors in Sprague Dawley rats. Behav Brain Res 310, 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekelmann S, Born J, 2010. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci 11, 114–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TS, Blaze J, Keller SM, Roth TL, 2017. Phenotypic outcomes in adolescence and adulthood in the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources outside the home cage. Dev Psychobiol 59, 703–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]