Abstract

Background

Although oncology clinical practice guidelines recognize the need and benefits of exercise, the implementation of these services into cancer care delivery remains limited. We developed and evaluated the impact of a clinically integrated 8‐week exercise and education program (CaRE@ELLICSR).

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods, prospective cohort study to examine the effects of the program. Each week, participants attended a 1‐h exercise class, followed by a 1.5‐h education session. Questionnaires, 6‐min walk tests (6MWT), and grip strength were completed at baseline (T0), 8 weeks (T1), and 20 weeks (T2). Semi‐structured interviews were conducted with a sub‐sample of participants about their experience with the program.

Results

Between September 2017 and February 2020, 277 patients enrolled in the program and 210 consented to participate in the research study. The mean age of participants was 55 years. Participants were mostly female (78%), white/Caucasian (55%) and half had breast cancer (50%). Participants experienced statistical and clinically meaninful improvements from T0 to T1 in disability, 6MWT, grip strength, physical activity, and several cancer‐related symptoms. These outcomes were maintained 3 months after program completion (T2). Qualitative interviews supported these findings and three themes emerged from the interviews: (1) empowerment and control, (2) supervision and internal program support, and (3) external program support.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the impact of overcoming common organizational barriers to deliver exercise and rehabilitation as part of routine care. CaRE@ELLICSR demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in patient‐reported and functional outcomes and was considered beneficial and important by participants for their recovery and wellbeing.

Keywords: cancer, exercise, implementation, quality of life, rehabilitation, supportive care, survivorship

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer survivors endure physical, functional, and psychosocial challenges prior to, during and after cancer treatment. Cancer‐related impairments are often undertreated and can result in reduced ability to perform basic and instrumental activities of daily living, recreational activities, and consequently, quality of life. 1 , 2 Thus, efforts to support the integration of cancer rehabilitation into oncology practice have become a priority to prevent, minimize, and restore these functional and quality of life losses. 3 , 4 , 5

Comprehensive cancer rehabilitation encompasses the coordinated delivery of interventions by a multidisciplinary team, including physical and occupational therapists, exercise professionals, social workers and dieticians, to name a few. 6 A multidimensional approach including both physical and psychosocial interventions is recommended to treat and manage the numerous and concurrent impairments people with cancer experience. 7 These interventions have been shown to be cost‐effective 5 and mitigate the costs associated with reduced work productivity and early retirement. 8 , 9 Multidimensional cancer rehabilitation interventions typically include exercise and education. Strong evidence demonstrates exercise provides wide‐ranging health benefits for cancer survivors, including reduced fatigue, improved physical function, and improved quality of life. 10 , 11 , 12 Additionally, self‐management educational interventions centerd on improving patients' knowledge, skills, and confidence with managing cancer‐related impairments have the potential to improve various symptoms and quality of life. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 However, the implementation of multidimensional cancer rehabilitation programs into real‐world practice is limited.

Despite clinical practice guidelines defining exercise and education as core components of survivorship care, 7 they are sparsely implemented into routine clinical practice. Further, evidence of their effect in practice is limited. Accordingly, our team developed and implemented an 8‐week exercise and education program to be delivered as part of routine care.

We sought to overcome commonly reported organizational barriers to implementing exercise and rehabilitation programming into routine cancer care (e.g., inadequate infrastructure to support the delivery of exercise, absence of established referral pathways and networks, and limited resources to deliver the program). 17 First, funding was obtained to build the infrastructure needed for the program as well as to deliver the program free to participants. Second, the team conducted a series of presentations and case studies at disease site rounds to increase awareness of the program and receive feedback from clinicians on efficient and well‐organized referral pathways that could be developed. For instance, a brief and user‐friendly referral form was developed that was embedded into the centre's electronic medical record with auto‐fax to facilitate referrals to the program. Additionally, oncologists refer patients to a multidisciplinary rehabilitation staff at the cancer center to further assess the patient and refer to the program when appropriate. This process aimed to enable the identification and referral of patients with unmet needs who may significantly benefit from participating in cancer rehabilitation and exercise programming, similar to the suggested pathway described by Santa Mina et al. 18 Following its implementation, we sought to evaluate the program. As such, the objectives of the present study were to (1) examine the effects of the program, (2) examine whether those effects were maintained 3 months following participation in the program, and (3) explore participant experience of the program.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

We conducted a mixed methods, prospective cohort study to examine the effects of a multidimensional cancer rehabilitation program in a mixed population of cancer survivors. The evaluation of the program was guided by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim. 19 This study was approved by the University Health Network (UHN) Research Ethics Board.

2.2. Setting

At the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, the Cancer Rehabilitation and Survivorship (CRS) clinic offers numerous services for adult (18 years or older) cancer survivors. The services offered through the CRS clinic are funded through the cancer center's foundation and are free to participants. The CRS clinic receives referrals from oncologists who identify a physical, functional, or cognitive impairment that may be addressed by rehabilitation. Following a joint initial comprehensive assessment in the CRS clinic with a physiatrist and physiotherapist or occupational therapist, and a discussion with the patient regarding their rehabilitation goals, a care plan is developed that may include registration into an 8‐week exercise and education program. The 8‐week program is delivered in‐person at the Electronic Living Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Cancer Survivorship Research (ELLICSR): Health Wellness and Cancer Survivorship Centre at UHN, and is called Cancer Rehabilitation and Exercise at ELLICSR (CaRE@ELLICSR). The ELLICSR gym contains a variety of aerobic exercise equipment (e.g., treadmill, stationary cycle, elliptical) and resistance training equipment (e.g., resistance bands, free weights, stability balls). All CRS staff delivering the program were trained in motivational interviewing 20 , 21 by a certified Motivational Interviewing Network Trainer. CRS staff were instructed to utilize motivational interviewing skills when delivering the program components (e.g., goal setting, education, exercise delivery).

2.3. Participants and recruitment

Given that CaRE@ELLICSR is delivered as part of routine care at the cancer center, participation in the research study evaluating the program was optional and not required to participate in the program. Starting in September 2017, newly registered patients in the program were invited to participate in the study and recruitment was ongoing until February 2020. Participants were asked for their written consent to use the data collected as part of their clinical visits for research purposes. In addition, they were asked if they would agree to be contacted to participate in a qualitative interview about their experience in the program.

2.4. Intervention: CaRE@ELLICSR

CaRE@ELLICSR was adapted from the Wellness and Exercise for Cancer Survivors Program, which demonstrated clinically relevant improvements in functional outcomes and high participant satisfaction. 22 Over the course of the study period, CaRE@ELLICSR underwent routine quality improvement initiatives that resulted in additional program adaptations to enhance participant experience (Table 1). Notable changes included the addition of an online platform to prescribe exercise to participants (i.e., Physitrack®), and wearable technology (i.e., Fitbit™) to facilitate adherence to the prescribed exercise intensity and promote motivation for overall physical activity.

TABLE 1.

Modifications to CaRE@ELLICSR during the study period.

| Date | Number of participants receiving modifcation | Modification | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2018 | 174 | Addition of aerobic exercises | The format of weekly exercise classes was modified from resistance‐only classes to individualized circuits alternating between resistance and aerobic exercise |

| November 2018 | 102 | Addition of motivational interviewing techniques | Comprehensive training and ongoing supervision on motivational interviewing was provided to all health care providers in the program. Training was provided by a Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers certified trainer |

| January 2019 | 83 | Group exercise class and education booster sessions at follow up appointment (T2) | Format of T2 visit was changed from individual appointments with a RKin, to a group exercise class with an individual fitness assessment completed before, during, or after the exercise class. Additionally, a social worker facilitated a 30‐min group discussion about barriers experienced in the past 3 months |

| January 2019 | 83 | Online exercise prescription delivery | Participants were provided with access to an online application (i.e., Physitrack™) with video, audio, and written instructions for all exercises prescribed. Participants were able to track their adherence and progress and connect with their RKin if needed. RKins could also monitor and adjust participants' exercise prescriptions remotely |

| April 2019 | 52 | Additional exercise equipment for classes | Various types of aerobic exercise equipment (e.g., elliptical, recumbent bike) were purchased and incorporated into the exercise classes to facilitate the circuit‐based format |

| May 2019 | 40 | Wearable technology provided to participants | Each participant was offered a Fitbit™ for the duration of the program to track activity and sleep |

The CaRE@ELLICSR program is delivered in‐person, once per week over 8 weeks in groups of 8–10 cancer survivors. Each session includes a 1‐h exercise class, followed by a 1.5‐h educational session on topics that were identified through a large needs assessment. In addition to consultation and feedback from the CRS clinical team, the needs assessment included a survey with cancer survivors (n = 60) at the center to identify the most relevant topics for self‐management skills teaching, the length of the program, and the duration of the classes. Prior to beginning the program, each participant undergoes an in‐person assessment conducted by a Registered Kinesiologist (RKin). This assessment includes a review of the participant's clinical history, symptom burden, current level of physical activity, and functional capacity, which are used to create an individualized exercise prescription.

Each exercise prescription was orginally developed to target the 2010 American College of Sports Medicine exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. 23 This was modified during the study period to target the updated 2019 guidelines of a minimum of 90 min per week of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise (progressing to 150 min) and 2 to 3 days of resistance training (minimum 2 sets of 8–12 repetitions for major muscle groups). 24 Each exercise prescription is partially completed in‐person, with the remaining dose expected to be completed independently between classes. Participants are provided with resistance bands to take home to facilitate the completion of their resistance exercise prescription. Participants are provided with a workbook that contains information about the program, their detailed exercise prescription with descriptions of the prescribed exercises and a workout log to track their exercise (adapted to Physitrack®), and information to support each week's education class.

Each exercise class is supervised by two RKins, with additional support by a physiotherapist during the first week. During exercise classes, participants perform their individualized exercise prescriptions using a circuit of resistance training and aerobic exercise (adapted from a resistance‐only format). Following the completion of the first resistance exercise, participants are instructed to complete 3 min of aerobic exercise at 50%–80% of their estimated heart rate range using any of the available equipment. Participants are instructed to repeat this until the completion of their prescribed resistance exercises (i.e., 5–7 cycles).

After each exercise session, participants have a 15‐min break and are relocated as a group to an adjacent classroom where educational sessions are conducted. Each 90‐min class is led by clinicians with expertise in the weekly topic. Education topics include: Getting Started—Goal Setting; Eat and Cook for Wellness; Manage Fatigue and Improve Sleep; Managing your Emotions; Be Mindful; Boost Your Brain Health; Find Ways to Connect; and Plan for Your Future. During these classes, the facilitators review the importance of each topic and its relationship to cancer rehabilitation and survivorship, and participants are encouraged to share their experiences and engage with each other. Additionally, the facilitators review several self‐management techniques to manage cancer‐related impairments and promote behavior change, and they also provide an opportunity for participants to set goals related to incorporating these strategies into their routines (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Education topics and examples of self‐management strategies.

| Session Topic | Session Facilitator(s) | Discussion topics and self‐management strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Getting Started—Goal Setting | Occupational therapist or Kinesiologist |

|

| Eat and Cook for Wellness | Registered Dietician and Wellness Chef |

|

| Manage Fatigue and Improve Sleep | Occupational therapist |

|

| Managing your Emotions | Social worker |

|

| Be Mindful | Occupational therapist |

|

| Boost your Brain Health | Neuropsychologist |

|

| Find Ways to Connect | Occupational therapist |

|

| Plan for your Future |

|

2.5. Measurement

As part of routine care for those attending the survivorship clinic, participants completed a questionnaire package using a tablet that included measures for cancer‐related symptoms, disability, and physical activity. Participants also completed a fitness assessment conducted by an RKin at baseline (T0), and at 8 (T1) and 20 (T2) weeks. All assessments were completed at ELLICSR. Qualitative interviews were conducted after T2 with a sub‐sample of participants (n = 16) in‐person or over the phone.

2.6. Outcomes

Demographic and clinical information were obtained by chart review at baseline and from the initial assessment questionnaire. Data included age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, socioeconomic status, primary cancer location, time since diagnosis, comorbidities, treatment status, and reason for referral.

Disability was measured using the 12‐item World Health Organization's Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO‐DAS 2.0). 25 , 26 Symptom severity was measured using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Schedule revised (ESAS‐r). 27 Physical Activity was measured using the Godin‐Shephard Leisure‐Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (GSLTPAQ) Leisure Score Index (LSI). 28 The 6‐min walk test (6MWT) was used to assess aerobic functional capacity in accordance with the American Thoracic Society protocol. 29 Upper body muscular strength was assessed with grip strength measured bilaterally with a standard Jamar dynamometer in accordance with the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology protocol. Particiapnts' weight and height were used to calculate their body mass index.

2.6.1. Program attendance

Class attendance was obtained by chart review and was calculated as a percentage of classes attended out of 8. While participants were encouraged to use a workout log or Physitrack® to record their exercise during the program, these tools were used to assist the RKins leading the classes in reviewing the participant's exercise prescription in a timely manner. This information was not collected for research purposes. In addition, this study did not collect the number of referrals made to the CaRE@ELLICSR program, reasons for refusal to participate in the program, and reasons for missed classes or follow‐up assessments.

2.6.2. Qualitative assessment of participant experience

We employed qualitative research methods, collecting data using in‐depth, 1‐h, semi‐structured interviews to elicit an understanding of participants' experiences in CaRE@ELLICSR. A convenience sample of participants who had completed the 8‐week program and had completed their 3‐month follow‐up assessment were invited to participate in the interviews. Interviewing participants three or more months after completing program provided an opportunity to explore potential factors influencing the maintenance of exercise and other self‐management strategies. Each interview included open‐ended questions along with relevant prompts that inquired about perceptions of various program components, facilitators and barriers related to attendance, and impact of the program on aspects of their daily lives. The semi‐structured nature and iterative process also enabled a flexible interview script in which interesting findings that emerged from one interview could be probed for in subsequent interviews. Following several interviews with participants, we purposively sampled and recruited male participants to ensure the interviews reflected different perspectives prior to reaching saturation of responses and themes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim prior to analysis.

2.7. Statistical and qualitative analysis

Demographic and clinical data are reported using descriptive statistics. Continuous data are reported as means and standard deviations along with median and range and categorical data are reported as frequencies and percentages. Program effects were assessed in accordance with the intention‐to‐treat principle using linear mixed effects models. Models were fitted with the following covariates: age (years), household socioeconomic status (prefer not to answer, <40,000, 40,000–75,000, or >75,000), cancer stage (I/II or III/IV), number of comorbidities (0–1, 2–3, or >3), years since diagnosis (0–1 years, >1–2 years, >2–5 years, >5 years), and program status (complete or dropout). The proportion of participants with moderate or high disability (WHODAS 2.0) was also examined across time points using Generalized Estimating Equations procedures. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3. Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05.

Interview transcripts were analyzed for main themes using an inductive approach to thematic analysis. 30 All transcripts underwent an initial round of coding in which each transcript was coded line‐by‐line to generate a broad sense of the data. Two members of our team with expertise in qualitative research (VT and CP), developed an initial coding framework by reading and analyzing the same three transcripts. This coding framework was then applied to and refined as analysis of the remaining transcripts took place. This process resulted in the development of a codebook, consisting of code names, definitions, example data, and analytical summaries. The codebook was applied in a second round of coding to ensure consistency of analysis across the interviews. Once all transcripts were coded, final themes were assessed. Memoing was conducted throughout the process to keep track of initial perceptions of the data and interesting findings that would be probed for in subsequent interviews. 31

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

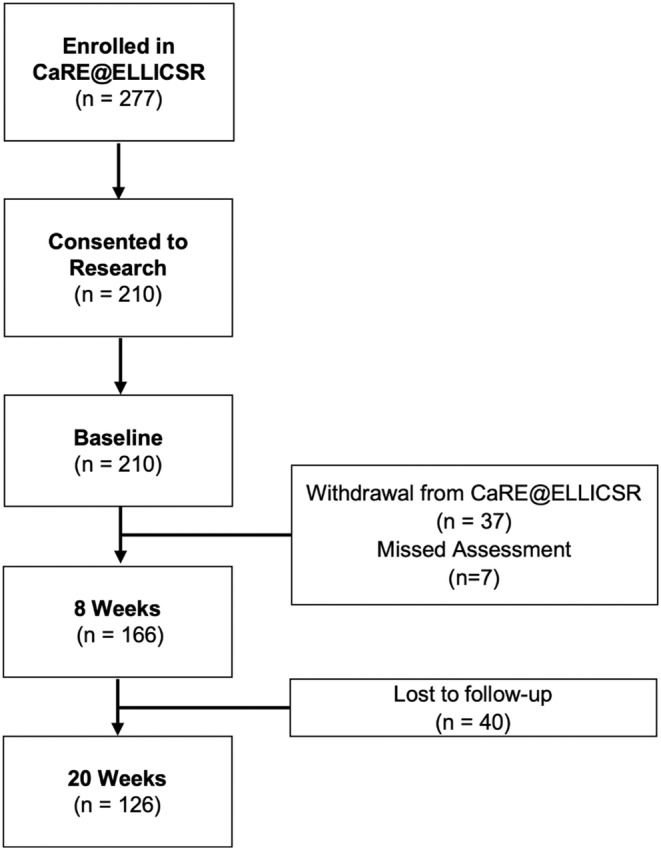

During the study period, 277 cancer survivors were registered into the CaRE@ELLICSR program, and 210 consented to participate in the research study (76%). The numbers of participants completing each assessment in the program are presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow and attendance.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are displayed in Table 3. Briefly, the mean age of participants was 55 years and participants were mostly female (78%), white/Caucasian (55%), and married or in a common‐law relationship (57%). The most common cancer types were breast cancer (50%), gynecologic cancer (21%), and lymphoma and myeloma (12%). At the start of program participation, 56% reported having completed primary treatment, and 33% reported currently receiving endocrine therapy. The median number of classes attended by participants was 7 (interquartile range = 6–8).

TABLE 3.

Participant demographic data (N = 210).

| Characteristic | Participants |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 55 (22–88) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 163 (78) |

| Male | 47 (22) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 115 (57) |

| South Asian | 28 (14) |

| East Asian | 17 (8) |

| Black/Afro‐Caribbean/African | 11 (5) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 9 (4) |

| Other | 23 (11) |

| Not reported | 7 |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |

| Married/Common‐law | 116 (57) |

| Single | 47 (23) |

| Divorced/Widowed/Other | 40 (20) |

| Not reported | 7 |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 20 (10) |

| Some university or college | 32 (16) |

| Finished university or college | 106 (53) |

| Other | 41 (21) |

| Missing | 11 |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | |

| <$75,000 | 60 (30) |

| >$75,000 | 69 (35) |

| Prefer not to answer | 71 (36) |

| Not reported | 10 |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Not employed/on disability/retired | 118 (62) |

| Employed | 73 (38) |

| Not reported | 19 |

| Cancer type, n (%) | |

| Breast | 105 (50) |

| Lymphoma and myeloma | 26 (12) |

| Gynecologic | 21 (10) |

| Genitourinary | 12 (6) |

| Head and neck | 10 (5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 9 (4) |

| Lung | 7 (3) |

| Leukemia | 6 (3) |

| Other a | 14 (7) |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | |

| I | 59 (30) |

| II | 61 (31) |

| III | 39 (20) |

| IV | 36 (18) |

| Missing or unavailable | 15 |

| Current treatment, n (%) | |

| None | 118 (56) |

| Endocrine therapy | 70 (33) |

| Targeted therapy | 11 (5) |

| Chemotherapy | 6 (3) |

| Immunotherapy | 4 (2) |

| Radiotherapy | 1 (1) |

| Reason for referral, n (%) b | |

| Fatigue | 149 (71) |

| Therapeutic exercise prescription/deconditioning | 105 (50) |

| Neurocognitive | 88 (42) |

| Psychosocial support | 81 (39) |

| Musculoskeletal | 66 (31) |

| Diet and nutrition | 41 (20) |

| Return to work | 19 (9) |

| Insominia | 12 (6) |

| Pain | 7 (3) |

| Time from diagnosis to initial assessment (years), median (range) | 1.26 (0.16–15.4) |

Includes central nervous system and eye, endocrine, melanoma, and sarcoma.

Participants can be referred for multiple reasons.

3.2. Outcomes

3.2.1. Quantitative findings

Figure 2 displays the proportion of participants who reported no disability, mild disability, moderate disability, or severe disability via the WHO‐DAS. From baseline (T0) to 20 weeks (T2), the proportion of participants reporting moderate to severe levels of disability significantly decreased, where the likelihood of reporting none or mild disability was 2.18 times higher at T2 when compared with baseline (p = 0.031).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of participants reporting each WHO‐DAS category at each study time point. Percentages are displayed for each time point in blue‐gray (no disability), light blue (mild disability), blue (moderate disability), and navy blue (severe disability).

Table 4 presents means and standard errors for each outcome over time. From baseline (T0) to the end of the 8‐week program (T1), statistically significant changes were observed for the WHO‐DAS (−1.81, 95% confidence interval (CI): −2.59 − (−1.04)), ESAS tiredness (−0.51, 95% CI: −0.84 − (−0.19)), ESAS anxiety (−0.45, 95% CI: −0.76 − (−0.14)), ESAS depression (−0.41, 95% CI: −0.73 − (−0.10)), ESAS wellbeing (−0.39, 95% CI: −0.77 − (−0.02)), total LSI (+13.3, 95% CI: 11.1–18.8) and moderate to strenuous LSI (+13.2, 95% CI: 9.88–16.5) via the GSLTPAQ, 6MWT (+37.4 m, 95% CI: 29.1–45.7), and grip strength (+4.78 kg, 95% CI: 3.55–6.02).

TABLE 4.

Estimates of outcomes measures.

| Outcome Measure | Time Point | N | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | Difference in the Estimates (95% CI) | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO‐DAS | T0 | 195 | 14.5 (0.87) | 12.7–16.2 | – | – |

| T1 | 134 | 12.6 (0.86) | 10.9–14.3 | −1.81 (−2.59 − (−1.04)) | <0.001 | |

| T2 | 111 | 12.0 (0.88) | 10.3–13.7 | −2.46 (−3.42 − (−1.50)) | <0.001 | |

| ESAS‐r Measures | ||||||

| Pain | T0 | 203 | 3.15 (0.24) | 2.67–3.63 | – | – |

| T1 | 141 | 3.09 (0.26) | 2.58–3.61 | −0.06 (−0.39–0.27) | 0.714 | |

| T2 | 113 | 2.92 (0.26) | 2.40–3.45 | −0.23 (−0.59–0.14) | 0.217 | |

| Tiredness | T0 | 203 | 4.69 (0.25) | 4.19–5.19 | – | – |

| T1 | 141 | 4.17 (0.26) | 3.65–4.70 | −0.51 (−0.84 − (−0.19)) | 0.002 | |

| T2 | 113 | 4.12 (0.29) | 3.56–4.69 | −0.56 (−0.99 − (−0.13)) | 0.012 | |

| Drowsiness | T0 | 203 | 3.05 (0.26) | 2.54–3.56 | – | – |

| T1 | 141 | 3.08 (0.27) | 2.55–3.61 | −0.03 (−0.33–0.38) | 0.178 | |

| T2 | 113 | 2.94 (0.28) | 2.39–3.50 | −0.11 (−0.58–0.36) | 0.238 | |

| Depression | T0 | 202 | 3.06 (0.28) | 2.51–3.60 | – | – |

| T1 | 141 | 2.65 (0.28) | 2.09–3.20 | −0.41 (−0.73 − (−0.10)) | 0.012 | |

| T2 | 113 | 2.87 (0.28) | 2.31–3.43 | −0.19 (−0.56–0.18) | 0.315 | |

| Anxiety | T0 | 202 | 3.52 (0.28) | 2.95–4.07 | – | – |

| T1 | 141 | 3.07 (0.28) | 2.51–3.63 | −0.45 (−0.76 − (−0.14)) | 0.005 | |

| T2 | 113 | 3.03 (0.29) | 2.46–3.61 | −0.48 (−0.85 − (−0.11)) | 0.010 | |

| Wellbeing | T0 | 202 | 4.41 (0.24) | 3.93–4.89 | – | – |

| T1 | 141 | 4.01 (0.25) | 3.52–4.51 | −0.39 (−0.77 − (−0.02)) | 0.038 | |

| T2 | 113 | 3.97 (0.26) | 3.93–4.89 | −0.44 (−0.85 − (−0.03)) | 0.034 | |

| GODIN | ||||||

| Total LSI | T0 | 210 | 16.7 (1.91) | 13.0–20.5 | – | – |

| T1 | 134 | 31.7 (2.49) | 26.8–36.6 | 14.9 (11.1–18.8) | <0.001 | |

| T2 | 115 | 24.0 (2.41) | 19.2–28.7 | 7.21 (3.28–11.1) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate to strenuous LSI | T0 | 210 | 6.85 (1.42) | 4.04–9.70 | – | – |

| T1 | 135 | 20.0 (2.06) | 16.0–24.1 | 13.2 (9.88–16.5) | <0.001 | |

| T2 | 115 | 13.2 (1.89) | 9.50–16.7 | 6.39 (3.37–9.40) | <0.001 | |

| Six minute Walk Test (Meters) | T0 | 203 | 442 (10.5) | 422–463 | – | – |

| T1 | 155 | 480 (10.1) | 460–500 | 37.4 (29.1–45.7) | <0.001 | |

| T2 | 106 | 480 (10.5) | 460–501 | 37.8 (28.5–47.2) | <0.001 | |

| Grip Strength (kg) | T0 | 210 | 50.9 (2.05) | 46.8–54.9 | – | – |

| T1 | 162 | 55.6 (2.08) | 51.5–59.7 | 4.78 (3.55–6.02) | <0.001 | |

| T2 | 118 | 56.6 (2.14) | 52.3–60.7 | 5.69 (4.16–7.24) | <0.001 | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | T0 | 196 | 28.2 (0.76) | 26.7–29.7 | – | – |

| T1 | 153 | 28.3 (0.76) | 26.8–29.8 | 0.10 (−0.10–0.31) | 0.325 | |

| T2 | 115 | 28.3 (0.75) | 26.8–29.8 | 0.08 (−0.15–0.32) | 0.474 | |

Bold indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

From baseline (T0) to 20‐weeks (T2), statistically significant changes in outcome measures were also observed for the WHO‐DAS (−2.46, 95% CI: −3.42 − (−1.50)), ESAS tiredness (−0.56, 95% CI: −0.99 − (−0.13)), ESAS anxiety (−0.48, 95% CI: −0.76 − (−0.14)), ESAS wellbeing (−0.44, 95% CI: −0.85 − (−0.03)), total LSI (+7.33, 95% CI: 3.28–11.1) and moderate to strenuous LSI (+6.39, 95% CI: 3.37–9.40) via the GSLTPAQ, 6MWT (+37.8 m, 95% CI: 28.5–47.2), and grip strength (+5.69 kg, 95% CI: 4.16–7.24). No other statistically significant changes were observed in any of the other measured variables during the 8‐week (T1) or 20‐week (T2) timepoints.

3.2.2. Qualitative findings

Twenty‐six participants were invited to be interviewed, and 16 agreed. Most interviewees were female (56%) and married (69%). Interview participants were treated for breast cancer (44%), genitourinary cancer (44%), or gynecological cancer (12%). The interviews revealed three key themes described in Table 5 along with representative quotes. Briefly, learning to prioritize exercise and healthy living as actionable strategies for rehabilitation and the improvements in physical and functional wellbeing observed through the quantitative surveys and fitness assessments, were often connected back to an improved sense of empowerment and control over their recovery in the qualitative interviews (theme 1, empowerment and control). Furthermore, the ability to meaningfully and successfully participate in the program and adhere to exercise and other program components was often connected back to having access to appropriate supports. Participants emphasized the importance of the supervision from the multidisciplinary staff delivering the program, as well as the benefits of exercising and socializing with other cancer survivors who had shared experiences (theme 2, supervision and internal program support). Participants also highlighted the importance of having access to quality supports outside the center to maintain the learned exercise and other self‐management stratagies at home, both during and after the program (theme 3, external program support).

TABLE 5.

Qualitative themes and representative quotes.

| Theme | Description | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Empowerment and Control |

|

“I [am less] focused on the disease and seeing myself as cycling through the same thing of like, ‘why did this happen to me.’ Now it's more like looking ahead. […] The exercise is good and now it's a priority for me. This is what I have to do to feel good. Same thing with nutrition—I'm more self‐aware at prioritizing my wellbeing.”—Female, gynecologic cancer. “I feel more confident, and I know what's going on and how to handle it. It's not like my life is perfect now, but it seems like I'm more in control of what's going on. I know myself more. […] The [program] has given me more opportunities to be more optimistic about my life.”—Female, gynecologic cancer |

| Supervision and Internal Program Support |

|

“Coming here and listening to lectures helped me get into a routine and after I get into a routine it's just a matter of maintaining it which I've been doing successfully. But if you just give me some books and say, ‘go home and do this’ I might not be able to. I might not even get started.”—Male, genitourinary cancer “There was an effort to encourage us to integrate the information into our lives but it's so challenging because you go [to ELLICSR] and it's an artificial world in a way. It's a nice little bubble. And when you leave, you can't take the ELLICSR people with you when you go back home. […] It's hard for it to carry over, to actually do the journaling, or to cook the recipes or trying to find the time for those things.”—Female, breast cancer |

| External Program Support |

|

“Your family expects you to do this, to do that. And I have to talk to them because of the chemo fog, I easily forget something. Don't blame me on that. It's stressful. They expect you to be normal.”—Female, breast cancer “My boss is a very nice, very understanding person, and he said, ‘no problem, whatever time you need, just take it off and do what you need to do.’”—Male, genitourinary cancer |

4. DISCUSSION

From a public health perspective, disability is considered as important as mortality 32 and cancer‐related disability is a prevalent adverse effect of cancer and its treatments. 1 Oncology clinical practice guidelines commonly recognize the need and benefits of rehabilitation and exercise and recommend these services for people living with and beyond cancer. 7 However, there is a gap in the implementation of these guidelines within the delivery of cancer care, which is reflected in the limited number of rehabilitation and exercise programs available for cancer survivors and the low rates of referrals to existing services. 33 , 34 , 35 While the evidence from systematic reviews and meta‐analyses clearly demonstrate the benefits of exercise interventions on managing cancer‐related impairments, 10 , 12 the inadequate number of exercise and rehabilitation programs embedded into clinical care limits our understanding of their effects in real‐world settings.

This study describes the effects of an 8‐week, group‐based, multidimensional cancer rehabilitation and exercise program for people with cancer delivered as part of routine care. Participants in the program achieved significant improvements in disability, physical activity, aerobic functional capacity, upper body muscular strength, as well as several cancer‐related symptoms. These findings are consistent with evaluations of real‐world community‐based exercise oncology programs in Canada. 36 , 37 , 38 Further, most of these outcomes were maintained 3 months after completing the CaRE@ELLICSR program. In fact, participants were approximately twice as likely to report mild or no disability after completing the program than at baseline. Additionally, the average increase of 37 metere via the 6MWT and 5.7 kg via grip strength observed in this study are considered clinically meaningful. 39 , 40 Given that cancer and its treatments can negatively impact functional capacity, improvements in these outcomes are essential for cancer survivors. 41

Participants in the current study also reported positive experiences with the program and highlighted its importance to their recovery and wellbeing. Results from the qualitative interviews indicate that attendance to the classes was in part facilitated by the group environment, including the ability for participants to share their experiences with each other and normalize many of the cancer‐related impairments they were experiencing. This is consistent with a systematic review describing the social benefits of exercise‐based rehabilitation. 42 Further, participants in the program were able to maintain improvements in their level of physical activity after the program, and they highlighted the benefits of the program on their ability to take control of their recovery and wellbeing. This reflects findings from a systematic review, where the most common facilitators of exercise reported by cancer survivors were gaining a sense of control over their health and managing emotions and mental well‐being. 43 Notably, participants in the program also underscored the importance of gaining confidence in exercise and other self‐management strategies and having support from family and employers to adhere to these behaviors during and after the program.

This study demonstrates the real‐world impact of overcoming common organizational barriers to deliver exercise and rehabilitation programming as part of routine care. However, it is important to highlight that CaRE@ELLICSR is delivered in a large urban cancer center that is highly resourced and supported through a well‐funded cancer foundation. As such, there may be significant challenges translating these findings to under‐resourced and under‐funded settings. These settings may need to adapt the in‐person model utilized by CaRE@ELLICSR to facilitate the implementation and delivery of critical multidimensional rehabilitation programming to their patient population. Distance‐based eHealth interventions have been suggested as one method to reduce barriers to accessing and providing rehabilitation. 44 , 45 Recognizing this challenge and opportunity, our team adapted CaRE@ELLICSR to develop the 8‐week CaRE@Home program, which consists of weekly remote check‐ins for exercise and behavior change support, as well as e‐modules providing interactive education to promote self‐management skills. Preliminary results indicate that the CaRE@Home program is feasible, acceptable, and may decrease disability, 46 highlighting the potential to translate the effects of CaRE@ELLICSR to settings that do not have sufficient resources and funding.

A limitation of this study is the lack of a control group. In the absence of a control group, it is possible that other factors could have contributed to the observed results (e.g., natural course of recovery, participation in additional rehabilitation services and programs within and outside of the hospital). Notably, the qualitative findings support the results of the quantitative outcomes, suggesting that participation in the program had a positive impact on participants' recovery and wellbeing. However, all participants interviewed had completed the program and the results do not include perspectives from participants who were unable to complete the program. In addition, about 80% of the participants in this study were female and half had breast cancer, potentially biasing the generalizability of the results. This may have been due to differences in referral patterns among physicians across disease site clinics at the cancer center (e.g., differences in screening for rehabilitation needs), as well as differences among patients in the likelihood to discuss rehabilitation services with their health care provider. The CRS clinic has a longstanding relationship with the breast clinic at the center and many oncologists were familiar with the clinic's services compared to providers working in other disease sites. Information on referral patterns to the CaRE@ELLICSR program will clarify the proportion and representativeness of participants referred and enrolled to the program, as well as reasons for non‐enrollment and participation. As such, the CRS clinic has developed a process for tracking this information through the electronic medical record system and internal databases which will inform ongoing quality improvement initiatives. Future studies would benefit from embedding an implementation science framework in the design of a comprehensive program evaluation. An improved understanding of a program's reach across the cancer center, barriers and enablers to adoption and sustainability, and costs of delivering the program would inform the selection of implementation strategies to embed these programs as part of routine clinical care. 47

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide important evidence on the health‐related benefits of a multidimensional cancer rehabilitation program, CaRE@ELLICSR, for cancer survivors delivered as part of routine care. This study provides further evidence supporting the integration of cancer rehabilitation and exercise programming within routine cancer care. CaRE@ELLICSR can serve as a model for the delivery of similar programs around the world.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Christian J. Lopez: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Daniel Santa Mina: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); supervision (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Victoria Tan: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Manjula Maganti: Data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); visualization (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Cheryl Pritlove: Data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Lori J. Bernstein: Conceptualization (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). David M. Langelier: Supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Eugene Chang: Conceptualization (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Jennifer M. Jones: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (supporting); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (lead); supervision (lead); visualization (supporting); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported through internal funding provided by the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation and the Butterfield/Drew Chair in Cancer Survivorship Research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was reviewed and approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (REB# 17‐5218).

PARTICIPANT CONSENT

All patients provided written consent for their data to be used for this analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the various contributions of the various clinicians and team members for supporting the development and delivery of the CaRE@ELLICSR program at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. We thank all of the study participants for their dedication and time to the study.

Lopez CJ, Santa Mina D, Tan V, et al. CaRE@ELLICSR: Effects of a clinically integrated, group‐based, multidimensional cancer rehabilitation program. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7009. doi: 10.1002/cam4.7009

Christian J. Lopez and Daniel Santa Mina should be considered joint first author.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to REB restrictions, we are not permitted to upload data to a public data repository. However, we can make data available upon request with a data transfer agreement.

REFERENCES

- 1. Neo J, Fettes L, Gao W, Higginson IJ, Maddocks M. Disability in activities of daily living among adults with cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;61:94‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joshy G, Thandrayen J, Koczwara B, et al. Disability, psychological distress and quality of life in relation to cancer diagnosis and cancer type: population‐based Australian study of 22,505 cancer survivors and 244,000 people without cancer. BMC Med. 2020;18:1‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duncan M, Moschopoulou E, Herrington E, et al. Review of systematic reviews of non‐pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life in cancer survivors. BMJ Open. 2017;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duijts SFA, Faber MM, Oldenburg HSA, Van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health‐related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors‐a meta‐analysis. Psychooncology. 2011;20:115‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mewes JC, Steuten LMG, IJzerman MJ, Harten WH. Effectiveness of multidimensional cancer survivor rehabilitation and cost‐effectiveness of cancer rehabilitation in general: a systematic review. Oncologist. 2012;17:1581‐1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alfano CM, Cheville AL, Mustian K. Developing high‐quality cancer rehabilitation programs: a timely need. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;36:241‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stout NL, Santa Mina D, Lyons KD, Robb K, Silver JK. A systematic review of rehabilitation and exercise recommendations in oncology guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;0:1‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silver JK, Baima J, Newman R, Galantino M, Shockney LD. Cancer rehabilitation may improve function in survivors and decrease the economic burden of cancer to individuals and society. Work. 2013;46:455‐472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Silver JK. Cancer rehabilitation and prehabilitation may reduce disability and early retirement. Cancer. 2014;120:2072‐2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sweegers MG, Altenburg TM, Chinapaw MJ, et al. Which exercise prescriptions improve quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer during and following treatment? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:505‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer‐related fatigue: a meta‐analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:961‐968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buffart LM, Kalter J, Sweegers MG, et al. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta‐analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:91‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howell D, Harth T, Brown J, Bennett C, Boyko S. Self‐management education interventions for patients with cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1323‐1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Agbejule OA, Hart NH, Ekberg S, Crichton M, Chan RJ. Self‐management support for cancer‐related fatigue: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;129:104206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self‐management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1585‐1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernstein LJ, McCreath GA, Nyhof‐Young J, Dissanayake D, Rich JB. A brief psychoeducational intervention improves memory contentment in breast cancer survivors with cognitive concerns: results of a single‐arm prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(8):2851‐2859. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4135-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kennedy MA, Bayes S, Newton RU, et al. Implementation barriers to integrating exercise as medicine in oncology: an ecological scoping review. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(4):865‐881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Santa Mina D, Sabiston CM, Au D, et al. Connecting people with cancer to physical activity and exercise programs: a pathway to create accessibility and engagement. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(2):149‐162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759‐769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(2):129‐140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santa Mina D, Au D, Auger LE, et al. Development, implementation, and effects of a cancer center's exercise‐oncology program. Cancer. 2019;125:3437‐3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American college of sports medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409‐1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Campbell KL, Winters‐Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2375‐2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luciano JV, Ayuso‐Mateos JL, Aguado J, et al. The 12‐item world health organization disability assessment schedule II (WHO‐DAS II): a nonparametric item response analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the world health organization disability assessment schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:88‐823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C, Johnson L, Myers J, Strasser F. A multicenter study comparing two numerical versions of the Edmonton symptom assessment system in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:456‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Godin G. The Godin‐Shephard leisure‐time physical activity questionnaire. Health Fit J Canada. 2011;4:18. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, et al. ATS statement: guidelines for the six‐minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Braun V, Clarke V. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association; 2012:57‐71. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bailey C. Coding, Memoing, and Descriptions. A Guide to Qualitative Field Research. 2014.

- 32. Üstün T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J. Measuring Health and Disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cheville AL, Kornblith AB, Basford JR. An examination of the causes for the underutilization of rehabilitation services among people with advanced cancer. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90:S27‐S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stubblefield MD. The underutilization of rehabilitation to treat physical impairments in breast cancer survivors. PM R. 2017;9:S317‐S323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raj VS, Pugh TM, Yaguda SI, Mitchell CH, Mullan SS, Garces NS. The who, what, why, when, where, and how of team‐based interdisciplinary cancer rehabilitation. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020;36:150974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santa Mina D, Au D, Brunet J, et al. Effects of the community‐based wellspring cancer exercise program on functional and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivors. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(5):284‐294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheifetz O, Park Dorsay J, Hladysh G, MacDermid J, Serediuk F, Woodhouse LJ. CanWell: meeting the psychosocial and exercise needs of cancer survivors by translating evidence into practice. Psychooncology. 2014;23(2):204‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Noble M, Russell C, Kraemer L, Sharratt M. UW WELL‐FIT: the impact of supervised exercise programs on physical capacity and quality of life in individuals receiving treatment for cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(4):865‐873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bohannon RW, Crouch R. Minimal clinically important difference for change in 6‐minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(2):377‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bohannon RW. Minimal clinically important difference for grip strength: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019;31(1):75‐78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Silver JK, Baima J, Mayer RS. Impairment‐driven cancer rehabilitation: an essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:295‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Midtgaard J, Hammer NM, Andersen C, Larsen A, Bruun DM, Jarden M. Cancer survivors' experience of exercise‐based cancer rehabilitation—a meta‐synthesis of qualitative research. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2015;54(5):609‐617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Clifford BK, Mizrahi D, Sandler CX, et al. Barriers and facilitators of exercise experienced by cancer survivors: a mixed methods systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:685‐700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tenforde AS, Hefner JE, Kodish‐Wachs JE, Iaccarino MA, Paganoni S. Telehealth in physical medicine and rehabilitation: a narrative review. PM R. 2017;9(5):S51‐S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hardcastle SJ, Maxwell‐Smith C, Kamarova S, Lamb S, Millar L, Cohen PA. Factors influencing non‐participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(4):1289‐1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. MacDonald AM, Chafranskaia A, Lopez CJ, et al. CaRE @ home: pilot study of an online multidimensional cancer rehabilitation and exercise program for cancer survivors. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11):3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Czosnek L, Richards J, Zopf E, Cormie P, Rosenbaum S, Rankin NM. Exercise interventions for people diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review of implementation outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to REB restrictions, we are not permitted to upload data to a public data repository. However, we can make data available upon request with a data transfer agreement.