Abstract

Objectives

CT is the clinical standard for surgical planning of craniofacial abnormalities in pediatric patients. This study evaluated three MRI cranial bone imaging techniques for their strengths and limitations as a radiation-free alternative to CT.

Methods

Ten healthy adults were scanned at 3 T with three MRI sequences: dual-radiofrequency and dual-echo ultrashort echo time sequence (DURANDE), zero echo time (ZTE), and gradient-echo (GRE). DURANDE bright-bone images were generated by exploiting bone signal intensity dependence on RF pulse duration and echo time, while ZTE bright-bone images were obtained via logarithmic inversion. Three skull segmentations were derived, and the overlap of the binary masks was quantified using dice similarity coefficient. Craniometric distances were measured, and their agreement was quantified.

Results

There was good overlap of the three masks and excellent agreement among craniometric distances. DURANDE and ZTE showed superior air-bone contrast (i.e., sinuses) and soft-tissue suppression compared to GRE.

Discussions

ZTE has low levels of acoustic noise, however, ZTE images had lower contrast near facial bones (e.g., zygomatic) and require effective bias-field correction to separate bone from air and soft-tissue. DURANDE utilizes a dual-echo subtraction post-processing approach to yield bone-specific images, but the sequence is not currently manufacturer-supported and requires scanner-specific gradient-delay corrections.

Keywords: Cranial bone, UTE, ZTE, Black-bone MRI

Introduction

CT is the clinical standard imaging modality for evaluation and surgical planning of craniofacial skeletal pathologies. One example is craniosynostosis; the premature fusion of the cranial sutures causing skull shape deformities in 1 in 2000 infants [1]. However, there are concerns of early exposure to ionizing radiation for children who may require multiple imaging procedures at a young age [2, 3]. The adverse radiation effects are greater for children due to the increased sensitivity of their developing organs and their higher lifetime attributable risk of malignancy [4]. High-resolution bone-selective MRI can serve as an ionizing-radiation-free alternative to CT [5–9]. In addition, MRI allows for both bone and soft-tissue imaging contrasts in a single scan session, which can be advantageous for assessing other common indications such as head trauma and parenchymal brain injuries.

Standard MRI is generally not suited for imaging bone because of its relatively low proton density (~ 20% by volume) and short T2 relaxation time (~ 0.4–0.5 ms) [10, 11], and thus both bone and air appear black. Recently, “black-bone” MRI (BB-MRI) has been espoused as a technique for craniofacial imaging based on a conventional 3D gradient-echo (GRE) sequence with very low flip angles to generate proton-weighted soft-tissue contrast [7, 9, 12–15]. Since it relies on the absence of signal from bone as a means to isolate it from soft tissues, it cannot distinguish between air and bone (e.g., sinuses), complicating skull tissue segmentation and thus 3D rendering and surgical planning. Ultra-short/zero echo time (UTE/ZTE) sequences are solid-state techniques that capture signal from protons with “solid-like” properties in osseous tissues (i.e., short lifetime of excited spins) which are undetectable with conventional sequences. UTE dual-echo subtraction approaches rely on the large difference in T2s to produce bone contrast while simultaneously suppressing soft-tissues. One recently conceived UTE method is the 3D dual-radiofrequency and dual-echo (DURANDE) technique that exploits the sensitivity of bone protons to RF pulse duration to further suppress soft tissues [5, 16], previously validated against CT both ex vivo and in vivo [17, 18]. Alternatively, ZTE approaches assume two unique proton-density signals from skull bone and soft-tissue, and use inverse logarithmic scaling to isolate three signal intensity compartments pertaining to bone, soft-tissues, and air. This has been demonstrated to resolve the bone–air–tissue interface in healthy adults and in pediatric patients [6, 19–21].

While these bone-selective MRI techniques have each demonstrated their utility for craniofacial imaging, no study has directly compared them for their strengths and limitations. The purpose of the present work was to quantitatively assess the performance of UTE and ZTE solid-state MRI methods compared to each other and to BB-MRI for the purposes for cranial bone imaging. This objective was achieved in a cohort of healthy adults by evaluating the methods’ ability to discriminate bone from soft tissues and air and examining the mutual bias of their binary images, along with the relative agreement in standard craniometric measurements derived from 3D skull reconstructions.

Methods

Study participants

Ten healthy participants (ages 26.1 ± 2.3 years) were recruited with no craniofacial anomalies, no prior craniofacial surgeries, and no ferromagnetic implants such as prosthetic joints, pacemakers, tattoos, or metallic braces. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Full participants’ characteristics are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Participants’ characteristics | Count |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Number of participants | 10 |

| Age (mean ± STD, years) | 26.1 ± 2.3 |

| Age (range, years) | 23–27 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 (60%) |

| Female | 4 (40%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian | 5 (50%) |

| Caucasian | 4 (40%) |

| African American | 1 (10%) |

MRI pulse sequences and imaging protocol

DURANDE’s sequence diagram (Online Resource Fig. S1) and detailed explanation can be found in previous work [5, 22]. Briefly, two radiofrequency (RF) pulses of different durations and amplitudes but identical flip angle are applied along two successive TRs, and following each RF pulse, two echoes are acquired at two TEs (Fig. S1A). The short echo of the first RF pulse captures the short T2 signal from bone, while the longer T2 signal from soft tissues is retained in all four echoes. Applying different RF pulse durations exploits the high sensitivity of the short T2 signals to variable RF widths [16], thus enhancing bone–signal contrast in the echo difference images when compared to standard dual-echo UTE. Each of the four echoes samples a different portion of k-space, then view-sharing [23] enables echoes at the same TEs to be combined for a fully sampled dataset, at no expense of increased scan time [5, 16]. Echoes at the same TEs are combined into two independent k-spaces, from which two images are reconstructed (Fig. S1B). The final bone image is generated by subtracting the two echo images (Fig. S1C). ZTE sequence with pointwise-encoding and time reduction with radial acquisition (ZTE–PETRA) [24–26] uses a center-out radial readout to sample most of k-space, except for a small inner portion that is missed immediately following the end of the RF pulse. The latter is acquired via single point imaging on a Cartesian grid.

All participants were imaged at 3.0 T (Prisma, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 20-channel head- and-neck coil using the three imaging sequences in one scan session, yielding three skull scans per participant. Imaging parameters for DURANDE [5] were TR/TE1/TE2 = 7/0.06/2.40 ms, RF1/RF2 = 0.04/0.52 ms, flip angle = 12°, dwell time = 4 μs, number of spokes = 50,000, FOV = 280 mm isotropic, matrix size = 256 × 256 × 256, and scan time = 6 min. The ZTE–PETRA [25] is a Siemens “Work in Progress” sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE = 2.85/0.07 ms, flip angle = 2°, dwell time = 8 μs, number of spokes = 100,000, FOV = 280 mm isotropic, matrix size = 256 × 256 × 256, and scan time = 5 min. The GRE [7, 9] product sequence had the following parameters: flip angle = 5°, TR/TE = 8.6/4.2 ms, FOV = 280 × 280 × 288 mm, matrix size = 288 × 288 × 144, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2, and scan time = 5.5 min.

Image post-processing

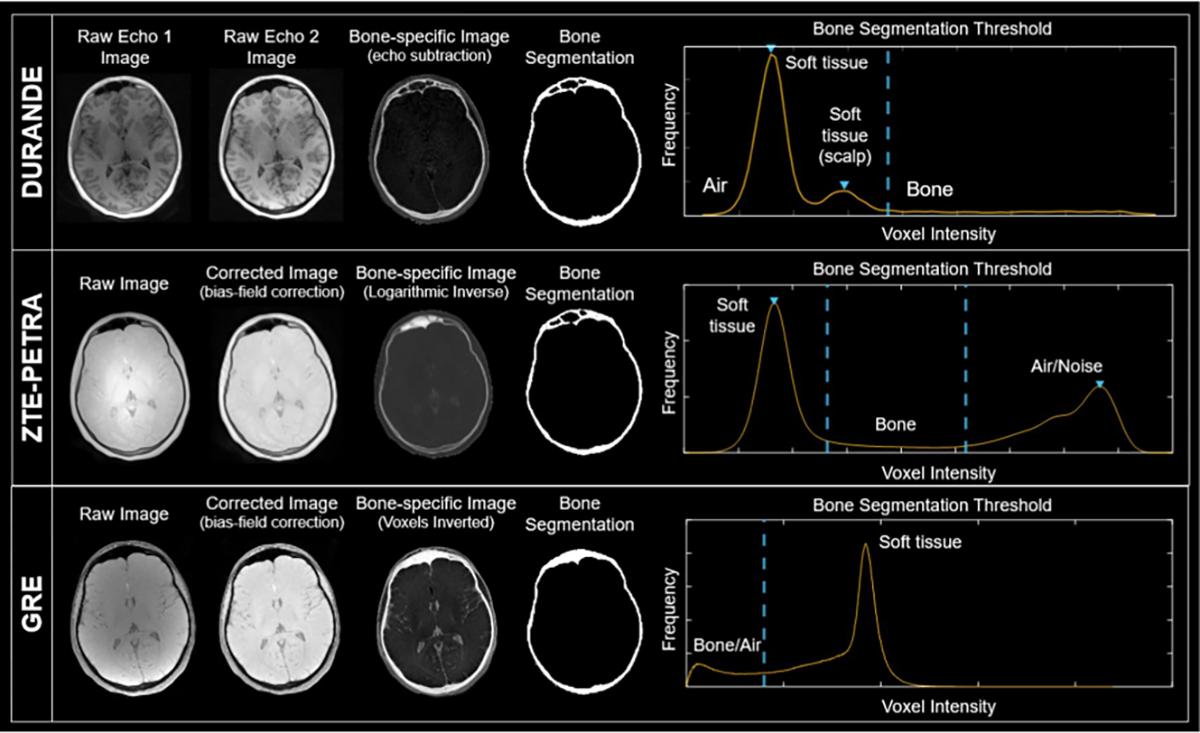

DURANDE bone-specific images are generated by weighted echo subtraction of the short- and long T2 images, such that Imagebone = (Imageecho1 − Imageecho2)/(Imageecho1 + Imageecho2) (Fig. 1C). A custom offline reconstruction was used; details of the reconstruction algorithm is discussed in previous work [5]. A calibration correction scan was done once in a phantom to correct for gradient timing delay causing k-space trajectory mismatches [5, 27]. For ZTE–PETRA and GRE, we applied bias-field correction using the nonparametric N4ITK method [28]. Soft-tissue suppression of ZTE–PETRA was done by logarithmic inversion to yield preliminary bright-bone images, but without the delineation of bone–air tissues [6, 19, 21].

Fig. 1.

Raw and processed images from the three MRI sequences: DURANDE, ZTE–PETRA, and GRE (BB-MRI) of the same anatomical slice in one participant. The ZTE–PETRA and GRE raw images are corrected for inhomogeneities in voxel intensities (bias-field correction) using the nonparametric N4ITK method. The bright-bone image in DURANDE is generated by echo subtraction, while that for ZTE–PETRA is obtained via logarithmic inversion. GRE images are inverted to make the bone appear bright. For DURANDE and GRE, a single threshold was used to segment the bone from other voxel compartments, while ZTE–PETRA required two thresholds. Note, air in the frontal sinus is correctly classified as such in both DURANDE and ZTE segmented images but not in GRE

A semi-automatic segmentation method was designed for each sequence to obtain the corresponding bone masks using custom code in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). For DURANDE, we used a custom histogram-based thresholding approach, where the bone-specific threshold was derived from the Gaussian fit of the intensity distribution for each axial slice. GRE images were segmented using a single global threshold. As for ZTE–PETRA, we utilized a histogram-thresholding approach proposed previously, involving two thresholds for bone/soft-tissue and bone/air separation [6, 19]. For all three sequences, the raw generated segmentations were refined by a series of morphological operations to remove small, artificially connected components near the edges of the head and fill in gaps in the skull. Finally, the masks were manually edited using the brush tool in ITK–SNAP version 3.8.0 [29] to further fill in gaps and remove erroneous segments, which took around 45 min to two hours per dataset. The final 30 segmented skull masks (10 participants × 3 scans) were then cropped to include only the cranial vault, orbit, and upper parts of the maxilla. Additional notes regarding the segmentation method are in the Online Resource Sect. 3.

Data and statistical analysis

To quantitatively compare the binary masks from the three sequences, six craniometric landmarks were identified on the 3D renderings to calculate three distances: glabella to opisthocranion, left frontozygomatic to right frontozygomatic sutures, and vertex to basion. These measurements were made using the ruler tool in 3D Slicer [30], performed by a trained craniofacial clinical research fellow at the Division of Plastic, Reconstructive and Oral Surgery at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. After registering the ZTE–PETRA and GRE masks to the DURANDE masks, Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) was calculated to evaluate the similarity of the binary segmentations among the three sequences. Among the three sequences, repeated measures ANOVA (RMA) was used to assess within-subject differences in craniometric measurements, while Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) and Bland–Altman plots were used to measure the agreement of each craniometric distance. Statistical analysis was performed in MATLAB and SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The contrast-to-noise (CNR) was quantified as an image quality metric, measured as the difference in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) between bone and soft-tissue using the equation: CNR=SNRbone −SNRsoft−tissue, where SNR is the average signal intensity in the tissue’s region-of-interest (ROI) divided by the standard deviation of the background (air). The ROIs were manually drawn in three different axial slices per subject per image type, and the average CNR was calculated from the three ROIs.

Results

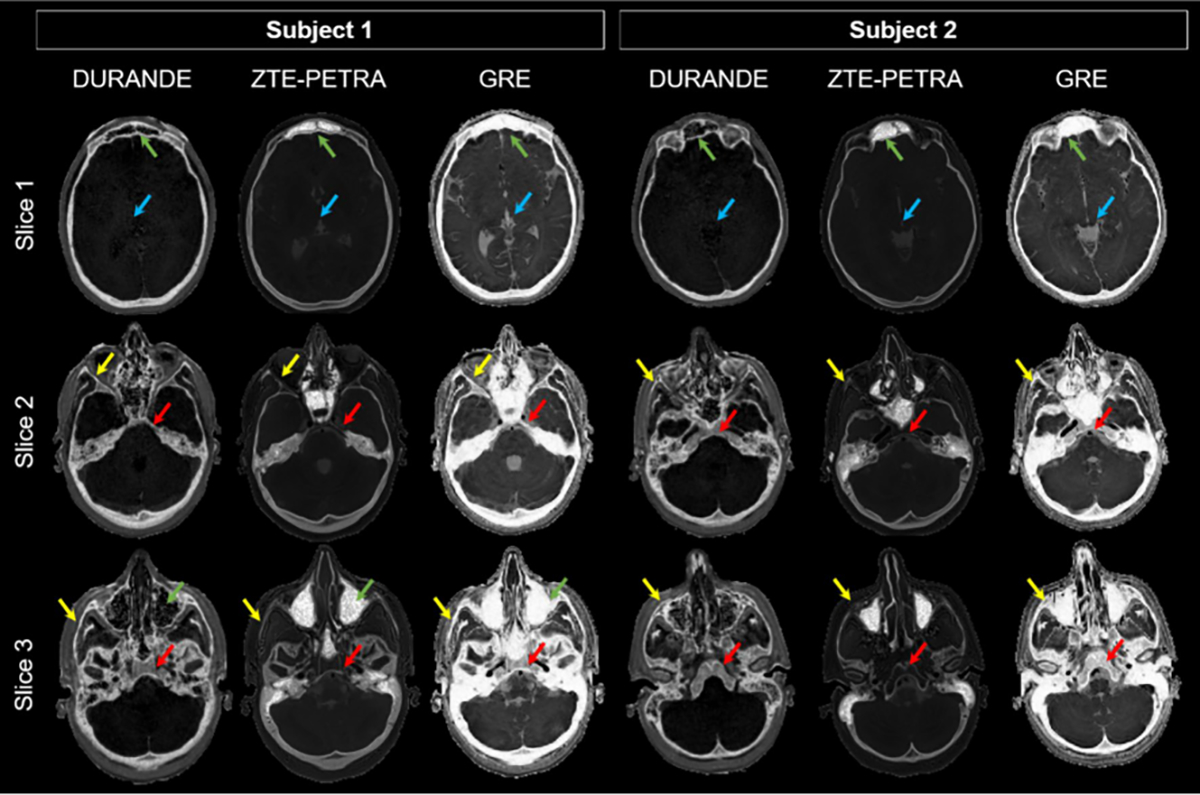

Full participants’ characteristics are in Table 1. The 10 healthy participants were 26.1 ± 2.3 years old, of whom 4 were females. The DURANDE bone-selective image generated from subtracting two echo images with highest and lowest bone signals is demonstrated in the Online Resource Fig. S1. Examples of the raw and corresponding processed bright-bone images for all MRI sequences are in Fig. 1. Comparisons of bone image sections from DURANDE, ZTE–PETRA and low-flip-angle short-TE GRE are depicted in Fig. 2 (for additional comparisons, see Online Resource Figs. S2 and S3). Note that air appears black (background intensity) in DURANDE and white (highest voxel intensity) in ZTE–PETRA, while both air and bone are indistinguishable in GRE since they both appear with background intensity. The average ± standard deviation of the CNR was 4.49 ± 0.44, 4.41 ± 1.67, and 94.21 ± 10.36 for DURANDE, ZTE–PETRA, and GRE, respectively. The CNR values per participant are listed in the Online Resource Table S1 and example ROIs are in Fig. S4.

Fig. 2.

Axial images in two participants acquired with three sequences (24 years old female, 23 years old female); DURANDE, ZTE–PETRA, and GRE. The bright-bone image in DURANDE is generated by echo subtraction, while that for ZTE–PETRA is obtained via logarithmic inversion after bias field correction. GRE images are inverted to make the bone bright. Note that intracranial air appears with background intensity in DURANDE as expected but with highest intensity in ZTE–PETRA, while both air and bone have the same voxel intensity in GRE. DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA resolve thin bone structures, with DURANDE clearly having higher contrast in thinner facial bones (yellow arrows). Unlike GRE, DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA can differentiate bone from air at the sinuses (green arrows) and have superior soft-tissue suppression (blue arrows). Since ZTE–PETRA is proton-density weighted, the bone marrow is fully attenuated after logarithmic inversion in thicker bone regions (red arrows, e.g., vertebrae), unlike DURANDE which retains part of the bone marrow’s signal in the echo subtraction image

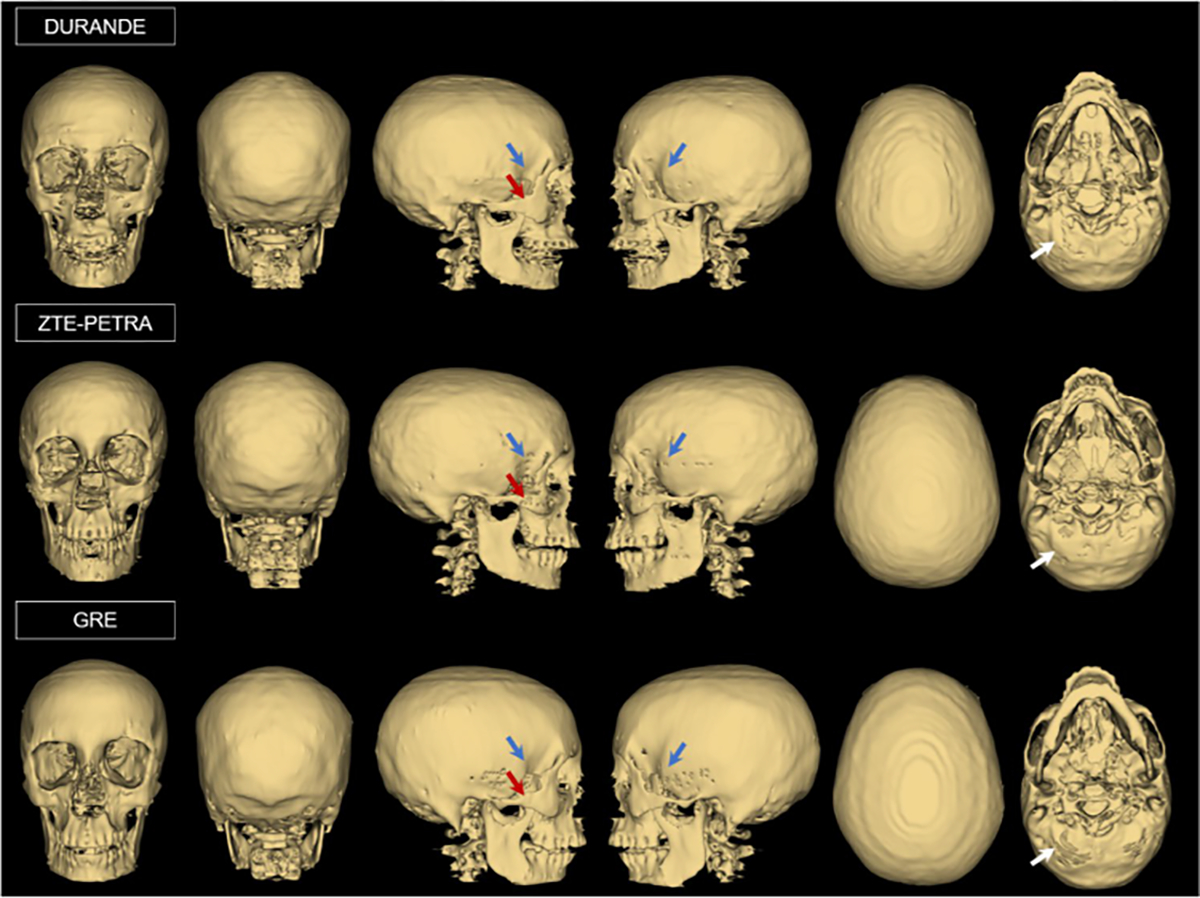

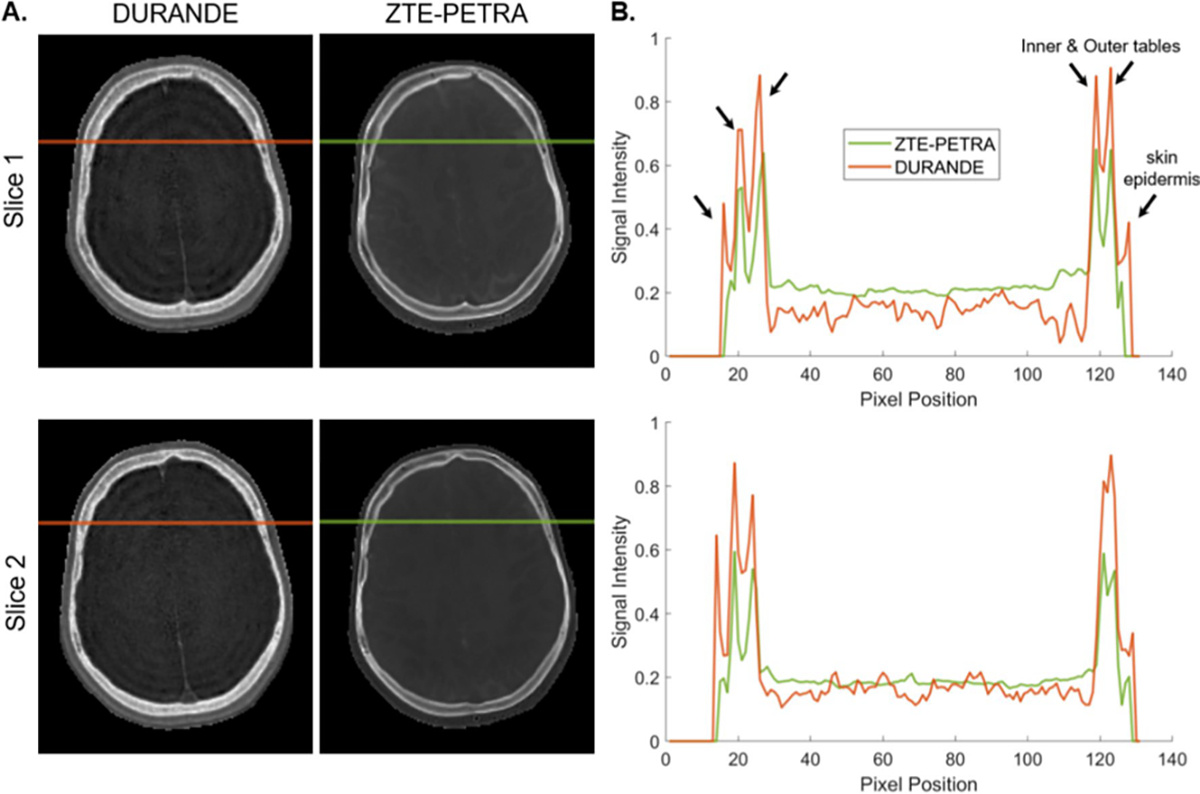

Whole-skull 3D renderings (Fig. 3) are overall similar across all three types of scans; however, differences are seen in missing thin bone regions such as the zygomatic arch and temporal bone, as well as the occipital bone. These regions were sometimes not selected by the bone-specific threshold or the morphological operations (Online Resource Sect. 3) due to their thin nature and lower voxel intensity, and hence, required further manual editing in the segmentation process. In addition, in all three MRI methods, thin bone regions may be completely unresolved if slight motion artifacts occur. Comparison of the bone signal intensity between DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA clearly depicts the outer and inner tables of the skull (Fig. 4), with ZTE–PETRA images displaying sharper contrast for the inner and outer tables than DURANDE due to free water and fat in the bone marrow being fully attenuated after the inverse logarithmic operation. Since ZTE–PETRA is proton-density weighted, the bone marrow is fully suppressed after logarithmic inversion in thicker bones (e.g., vertebrae and zygomatic bone), unlike DURANDE which retains part of the bone marrow’s signal in the echo subtraction image (Fig. 2). Therefore, for DURANDE images, even when the cortical bone is not resolved, the integrity of the bone structure is preserved due to the signal intensity from the bone marrow. On the contrary, for ZTE–PETRA images, any uncertainty in the cortical bone boundary may not be compensated for due to the attenuation of bone marrow signal in the inverse logarithmic image. Of note is the hyperintense signal observed from skin in DURANDE due to signal from very short T2 water protons in the epidermis of the scalp [31]. Furthermore, there is hyperintense signal from a portion of the temporalis tendon in the DURANDE/GRE images due to part of the tendon being closely orientated with the static field, effectively lowering its T2 to ~ 1–2 ms [32, 33], therefore imparting it bone-like signal properties. We note that GRE images exhibit minimal (or no) differentiation of the skull bone tables due to bone signal decay at the time of echo acquisition.

Fig. 3.

Skull 3D renderings of one participant (24 years old female) from DURANDE, ZTE–PETRA, and GRE. Note slight differences in regions of thin bone (blue arrows), zygomatic bone (red arrows), and occipital bone (white arrows) among the three sets of images

Fig. 4.

Signal intensity profiles for DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA along the horizontal-colored lines, depicting bone signal of the outer and inner tables of the skull (arrows). A Both sequences clearly differentiate between the inner and outer tables. B Signal profile shows the bone peaks on the right only partially resolved due to the bone tables being closer to each other. The sharp outermost peak is due to - signal from very short T2 water protons in the epidermis of the scalp

The average ± standard deviation of DSC among scan pairs and across all participants were 81.2% ± 12.7%, 78.3% ± 12.8%, and 76.3% ± 14.2% for DURADE vs ZTE–PETRA, DURANDE vs GRE, and ZTE–PETRA vs GRE, respectively (Table 2). Overall, all scan pairs have comparable DSC results with no statistical significance among the three groups (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.31). However, DSC among the three types of images vary considerably depending on the slice location; the overlap in bone segmentations was higher for superior slices in the cranial vault, which is essentially devoid of bone–air interfaces. The mean DSC and craniometric measurements per participant are in the Online Resource Tables S2 and S3. In addition, a large portion of the facial bones were excluded in this analysis, such that the lower part of the maxilla, teeth, and mandibles were removed from the final bone masks. The teeth and the lower part of the maxilla were more challenging to image consistently among the three sequences because of motion artifacts (e.g., mouth breathing and swallowing), which subsequently blurred the bone structures and artificially increased differences in the segmented bone masks.

Table 2.

Mean dice similarity coefficient (DSC), mean difference in craniometrie measurements, and Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) between scan pairs across all participants (n = 10)

| Scan pair | DSC (mean ± STD) | Mean difference in craniometrics (mm, mean ± STD) |

Lin’s CCC (r, [95% confidence interval]) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glabella to opisthocranion | Left to right frontozygomatic suture | Vertex to basion* | Glabella to opisthocranion | Left to right frontozygomatic suture | Vertex to basion | ||

|

| |||||||

| DURANDE vs ZTE-PETRA | 81.2% ± 12.7% | 0.25 ± 1.16 | 0.38 ± 1.25 | 1.73 ± 1.21 | 0.99 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.95 [0.81, 0.99] | 0.96 [0.88, 0.99] |

| DURANDE vs GRE | 78.3% ± 12.8% | 0.21 ± 1.13 | 0.01 ± 1.26 | 0.90 ± 1.06 | 0.99 [0.97, 0.99] | 0.95 [0.83, 0.99] | 0.98 [0.94, 1.00] |

| ZTE-PETRA vs GRE | 76.3% ± 14.2% | 0.04 ± 1.14 | 0.37 ± 0.83 | 0.83 ± 1.55 | 0.99 [0.95, 1.00] | 0.97 [0.89, 0.99] | 0.97 [0.91, 0.99] |

All craniometric values were determined from the 3D renderings using the ruler tool in 3D Slicer [30]

DSC dice similarity coefficient, CCC Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient

Using repeated measures of ANOVA, there is a significant within-subject differences among DURANDE, ZTE-PETRA, and GRE (p = 0.002). p value estimated using Mauchly’s sphericity assumed test

The mean differences in craniometric measurements are shown in Table 2. Among all scan pairs, the mean difference in measurements was 0.17 ± 1.1, 0.25 ± 1.14, and 1.15 ± 1.65 for glabella-to-opisthocranion, left-to-right frontozygomatic sutures, and vertex-to-basion, respectively. The RMA test was applied for each craniometric distance to evaluate within-subject differences among the three MRI sequences. Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated equal variances for glabella-to-opisthocranion (p = 0.99), left-to-right frontozygomatic sutures (p = 0.41), and vertex-to-basion (p = 0.46). For the vertex-to-basion distance, there was a significant within-subject differences among DURANDE, ZTE–PETRA, and GRE (p = 0.002). There were no significant within-subject differences among scan types for glabella-to-opisthocranion (p = 0.79) and left-to-right frontozygomatic sutures (p = 0.50).

Lin’s CCC for the three craniometric distances are in Table 2. There was high agreement among all scan pairs across all craniometric distances (rc > 0.90). Bland–Altman and correlation analysis between scan pairs for all three distances are displayed in the Online Resource Fig. S5. For the vertex-to-basion distance, DURANDE had a significant mean bias of − 1.7 mm (± 1.96 SD = [− 4.1, 6.5], p < 0.01) and − 0.9 mm (± 1.96 SD = [− 3.0, 1.2], p = 0.03) when compared to ZTE–PETRA and GRE, respectively. DURANDE vs ZTE–PETRA had insignificant bias for glabella-to-opisthocranion (mean − 0.25 mm, ± 1.96 SD = [− 2.5, 2.0], p = 0.51) and left to right frontozygomatic suture (mean − 0.38 mm, ± 1.96 SD = [− 2.8, 2.1], p = 0.36). DURANDE vs GRE had insignificant bias for glabella-to-opisthocranion (mean − 0.21 mm, ± 1.96 SD = [− 2.4, 2.0], p = 0.57) and left to right frontozygomatic suture (mean 0.01 mm, ± 1.96 SD = [−2.5, 2.5], p = 0.98). Furthermore, none of the craniometric distances showed significant bias between ZTE–PETRA and GRE.

Discussion

CT is the standard utilized by craniofacial surgeons for preoperative and postoperative assessment of their patients. The downside of this approach is the risk that early exposure to ionizing radiation entails in pediatric patients, some of whom may require multiple imaging sessions at a very young age. MRI for high-resolution bone imaging is thus of interest as it may provide a radiation-free alternative to CT, as well as its ability to achieve both bone and soft-tissue contrasts in a single scan session. We quantitatively compared two bone-selective MRI techniques (DURANDE and ZTE) and one conventional approach (GRE, or “BB-MRI”) for cranial bone imaging by assessing the similarities among their tissue classifications and craniometric measurements in healthy adults. We observed overall good agreement in the segmented bone images of the cranial vault among the three methods; however, the level of agreement was dependent on slice location. The overlap was higher for superior slices in the cranial vault, and lower in inferior slices containing sinuses and occipital bones. In addition, the measured vertex-to-basion distance was more variable when calculated from the three imaging methods because of partial volume errors in the vertex and occipital bone regions, making it especially challenging to accurately identify the vertex. The bias in the vertex-to-basion distance might have also been exaggerated due to the limitations of the manual refinement of the skull masks and the small sample size.

While surface-based craniometric measurements of the skull agreed well among all scan pairs across all craniometric distances (rc > 0.90), close examination of the inner anatomy shows differences in resolving thin bones around the sinuses and facial bones. Assuming only three voxel compartments of bone, soft-tissues, and air, the bright-bone image histogram of DURANDE has bone and air with the highest and lowest voxel intensities, respectively. Therefore, any bone voxel misclassification can potentially occur between bone and soft-tissues interfaces only. In ZTE–PETRA bright-bone images, however, bone voxels are located between soft-tissues (lowest intensity) and air (highest intensity). Segmenting the bone requires two thresholds at the boundaries of bone/soft-tissues and bone/air. As a result, bone voxel misclassification can occur at both interfaces, increasing the ambiguity of soft-tissue suppression and separation of bone from air compared to the DURANDE images. ZTE–PETRA images were generally found to have poor contrast in the facial bones (e.g., maxilla, zygomatic, and nasal bones), which may be attributed to insufficient bias-field correction. On the other hand, DURANDE is self-normalized due to the voxelwise echo subtraction (and therefore not dependent on the global intensity histogram), and hence, has greater contrast in the facial bones. ZTE–PETRA images had sharper contrast for the inner and outer tables than DURANDE due to free water and fat in the bone marrow being fully attenuated after the inverse logarithmic operation. However, DURANDE and GRE images had hyperintense bone-like signal from a portion of the temporalis tendon [32, 33]. Unlike DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA, BB–MRI does not differentiate between bone and air, which resulted in discrepancies in the segmented skull images in regions with bone–air boundaries.

DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA are superior to BB–MRI being solid-state MRI techniques that capture short T2 signal from bone. In addition to ZTE sequences being manufacturer-supported, the high level of gradient acoustic noise suppression is beneficial for patient comfort, especially when children are evaluated [34]. However, a limitation of ZTE-type sequences is the need for effective bias-field correction to fully suppress soft tissues and increase the separation between bone and air [6, 19, 21], especially near the sinuses and the facial bones (maxilla, zygomatic, and nasal bones). Bone segmentation is further limited by the ambiguity of the overlap of the histograms pertaining to bone and air and bone and soft-tissues, resulting in erroneous classification of bone voxels in thinner regions and the sinuses. In comparison, UTE-type dual-echo subtraction techniques, including DURANDE, are self-normalized and are designed to selectively yield signal only from bone with suppression of soft-tissue and separation from air. Moreover, when compared to ZTE, DURANDE has superior bone contrast for bone anatomies with thinner cortical shells (e.g., zygomatic bone) because it does not fully suppress the bone marrow and trabecular compartment.

Relative to ZTE, DURANDE might be more sensitive to blurring caused by off-resonant spins, for instance at the interface of tissues differing in magnetic susceptibility [35] (i.e., bone and soft-tissue) resulting in local induced field inhomogeneity causing spin dephasing during the second echo time. Off-resonance effects from fat–water chemical shift, on the other hand, should be minimal given the choice of TE2 (2.4 ms) corresponding to a full period of the fat–water difference frequency at 3 T field strength [36]. Lastly, even ZTE is not immune to blurring from off-resonant spins occurring during sampling though corrections are possible to mitigate this effect [37]. DURANDE is currently not manufacturer-supported, and requires scanner-specific gradient delay correction for offline image reconstruction [5]. The gradient delay calibration scan is performed once in a phantom and is later used for all subject scans. It is noted that scanner-specific gradient delay correction is required for both ZTE and UTE-type sequences, which can impact the effective image resolution and subsequently the accuracy of craniofacial distance metrics. Finally, filling the dead-time gap with PETRA generally achieves better image quality at the expense of potentially longer TR periods if acoustic noise levels are to be minimized [38]. The Siemens’ ZTE–PETRA “Work in Progress” sequence was set to have the shortest TR available to the user (i.e., TR = 2.85 ms). However, other variants of ZTE sequences may allow for shorter TRs and may thus achieve overall shorter scan time, which can also be beneficial for reducing motion artifacts [6, 19, 21] albeit at some penalty in SNR.

Past studies are largely based on conventional BB–MRI in pediatric patients [7, 9, 12–15, 39], of which only a few quantitatively compared MRI’s diagnostic accuracy against CT using reader ratings [8, 13, 15, 39–41] or the agreement of craniometric distances [7]. Only a few studies quantitatively investigated the overlap of the segmented skull images between MRI and CT [17–19] similar to the work presented here. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study has directly compared MRI cranial bone imaging techniques against each other. The present study may therefore shed light on strengths and limitations of different techniques and guide future studies for better quantitative evaluation of bone-selective MRI.

Healthy adults were chosen because they are able to lay still inside the scanner for longer periods of time without sedation. We believe an adult population is suitable given the goal of this study, which was to quantitatively compare various MRI cranial imaging techniques. However, employment of these methods in pediatric patients will pose particular challenges; notably the need for smaller voxel size to account for the smaller skull dimensions of children, demanding a tightly coupled pediatric head coil to compensate for some of the lost SNR from reduced voxel size. Moreover, bone-selective MRI is highly sensitive to head movements due to many cranial bones being thin in nature, and hence, a robust motion-correction strategy would be needed when imaging children [22, 42]. Compared to MRI, segmenting the bone for 3D skull renderings from CT images is straightforward, typically achieved by setting a single threshold since CT Hounsfield units are substantially higher for bone than for soft-tissues and air. Segmenting the skull from MR images is more labor intensive and requires expert knowledge of the skull anatomy due to the overlap in voxel intensities of bone, soft-tissues, and air in MR images. One potential solution is to train a deep-learning model to automatically segment the skull from MR images using CT images as the ground-truth segmentation [43–45]. Finally, craniometric distances were included in this analysis because they are routinely used by craniofacial surgeons for pre-operative and post-operative assessment of pediatric patients. In addition to craniometric distances, future work on pediatric patients should include Likert score analysis by trained radiologists to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the three MRI sequences as compared to clinical-standard CT.

The present study has limitations. First, the MRI-derived segmented skull images were not evaluated against the clinical standard CT. However, concerns of radiation exposure dissuaded us from subjecting healthy volunteers to CT. Nevertheless, DURANDE demonstrated strong agreement with CT in previous studies both ex vivo and in vivo [17, 18], and a ZTE-type sequence and BB–MRI were previously compared to CT as well [6, 9, 12, 19, 21]. Second, the semi-automatic segmentation approach relies on manual editing of the segmented skull images, which may introduce subjective errors especially near the sinuses and thinner bone regions. In addition, the sinuses were included in the BB–MRI segmentation since bone and air cannot be discerned, which may have affected the bias among the three sequences. Training a deep-learning model for automatic skull segmentation requires ground-truth labels derived from CT images, which were not available at the time this study was conducted. In addition, deep-learning models require large datasets for training and testing, and the current sample size without ground-truth CT would therefore not be adequate for training, especially since three distinct models would be required to segment the DURANDE, ZTE, and GRE images separately.

Conclusions

In conclusion, two bone-selective MRI techniques (DURANDE and ZTE) and one conventional sequence (GRE, or “black-bone MRI”) were quantitatively assessed for their strengths and limitations for cranial bone imaging by scanning healthy adults within one scan session. DURANDE and ZTE–PETRA yielded superior air-bone contrast and soft-tissue suppression compared to BB–MRI. The main benefit of ZTE–PETRA is its potential for shortened scan time and the very low level of acoustic noise it generates as the gradients are not ramped down between views [34]. DURANDE’s strength is that it is self-normalized and has superior bone-contrast for facial bones with thinner cortical shells. To further investigate the clinical utility of MRI for craniofacial bone imaging, future work should include quantitative evaluation of all three sequences against CT in a cohort of patients indicated for craniofacial surgery.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Study supported by the National Institutes of Health: NIH R21 DE028417, NIH T32 EB020087, F31 AR079925.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical standards All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board and made in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, in accordance with the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board requirements.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01125-8.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Johnson D, Wilkie AO (2011) Craniosynostosis. Eur J Hum Genet 19(4):369–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, McHugh K, Lee C, Kim KP, Howe NL, Ronckers CM, Rajaraman P, Sir Craft AW, Parker L, Berrington de González A (2012) Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 380(9840):499–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathews JD, Forsythe AV, Brady Z, Butler MW, Goergen SK, Byrnes GB, Giles GG, Wallace AB, Anderson PR, Guiver TA, McGale P, Cain TM, Dowty JG, Bickerstaffe AC, Darby SC (2013) Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 346:f2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, Greenlee RT, Weinmann S, Solberg LI, Feigelson HS, Roblin D, Flynn MJ, Vanneman N, Smith-Bindman R (2013) The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr 167(8):700–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H, Zhao X, Song HK, Zhang R, Bartlett SP, Wehrli FW (2019) Rapid dual-RF, dual-echo, 3D ultrashort echo time craniofacial imaging: a feasibility study. Magn Reson Med 81(5):3007–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesinger F, Sacolick LI, Menini A, Kaushik SS, Ahn S, Veit-Haibach P, Delso G, Shanbhag DD (2016) Zero TE MR bone imaging in the head. Magn Reson Med 75(1):107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eley KA, McIntyre AG, Watt-Smith SR, Golding SJ (2012) “Black bone” MRI: a partial flip angle technique for radiation reduction in craniofacial imaging. Br J Radiol 85(1011):272–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel KB, Eldeniz C, Skolnick GB, Jammalamadaka U, Commean PK, Goyal MS, Smyth MD, An H (2020) 3D pediatric cranial bone imaging using high-resolution MRI for visualizing cranial sutures: a pilot study. J Neurosurg Pediatr 26(3):311–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eley KA, Watt-Smith SR, Sheerin F, Golding SJ (2014) “Black Bone” MRI: a potential alternative to CT with three-dimensional reconstruction of the craniofacial skeleton in the diagnosis of craniosynostosis. Eur Radiol 24(10):2417–2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM (2003) Magnetic resonance: an introduction to ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 27(6):825–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichert ILH, Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, He T, Chappell KE, Holmes J, Girgis S, Bydder GM (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging of cortical bone with ultrashort TE pulse sequences. Magn Reson Imaging 23(5):611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eley KA, Watt-Smith SR, Golding SJ (2012) “Black bone” MRI: a potential alternative to CT when imaging the head and neck: report of eight clinical cases and review of the Oxford experience. Br J Radiol 85(1019):1457–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saarikko A, Mellanen E, Kuusela L, Leikola J, Karppinen A, Autti T, Virtanen P, Brandstack N (2020) Comparison of black bone MRI and 3D-CT in the preoperative evaluation of patients with craniosynostosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 73(4):723–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuusela L, Hukki A, Brandstack N, Autti T, Leikola J, Saarikko A (2018) Use of black-bone MRI in the diagnosis of the patients with posterior plagiocephaly. Childs Nerv Syst 34(7):1383–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonhardt Y, Kronthaler S, Feuerriegel G, Karampinos DC, Schwaiger BJ, Pfeiffer D, Makowski MR, Koerte IK, Liebig T, Woertler K, Steinborn MM, Gersing AS (2022) CT-like MR-derived images for the assessment of craniosynostosis and other pathologies of the pediatric skull. Clin Neuroradiol. 10.1007/s00062-022-01182-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson EM, Vyas U, Ghanouni P, Pauly KB, Pauly JM (2017) Improved cortical bone specificity in UTE MR imaging. Magn Reson Med 77(2):684–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman CE, Khandelwal P, Xie L, Lee H, Song HK, Yushkevich PA, Vossough A, Bartlett SP, Wehrli FW (2021) Automatic segmentation of bone selective MR images for visualization and craniometry of the cranial vault. Acad Radiol. 10.1016/j.acra.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Lee H, Zhao X, Song HK, Vossough A, Wehrli FW, Bartlett SP (2020) Bone-selective MRI as a nonradiative alternative to CT for craniofacial imaging. Acad Radiol 27(11):1515–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delso G, Wiesinger F, Sacolick LI, Kaushik SS, Shanbhag DD, Hüllner M, Veit-Haibach P (2015) Clinical evaluation of zero-echo-time MR imaging for the segmentation of the skull. J Nucl Med 56(3):417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho SB, Baek HJ, Ryu KH, Choi BH, Moon JI, Kim TB, Kim SK, Park H, Hwang MJ (2019) Clinical feasibility of zero TE skull MRI in patients with head trauma in comparison with CT: a single-center study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40(1):109–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu A, Gorny KR, Ho ML (2019) Zero TE MRI for craniofacial bone imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40(9):1562–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H, Zhao X, Song HK, Wehrli FW (2020) Self-navigated three-dimensional ultrashort echo time technique for motion-corrected skull MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 39(9):2869–2880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song HK, Dougherty L (2000) k-space weighted image contrast (KWIC) for contrast manipulation in projection reconstruction MRI. Magn Reson Med 44(6):825–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grodzki DM, Jakob PM, Heismann B (2012) Ultrashort echo time imaging using pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA). Magn Reson Med 67(2):510–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Magland JF, Seifert AC, Wehrli FW (2014) Correction of excitation profile in zero echo time (ZTE) imaging using quadratic phase-modulated RF pulse excitation and iterative reconstruction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 33(4):961–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Magland JF, Zhao X, Seifert AC, Wehrli FW (2017) Selective in vivo bone imaging with long-T(2) suppressed PETRA MRI. Magn Reson Med 77(3):989–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann K-H, Krämer M, Reichenbach JR (2016) Time efficient 3D radial UTE sampling with fully automatic delay compensation on a clinical 3T MR scanner. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0150371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA, Zheng Y, Egan A, Yushkevich PA, Gee JC (2010) N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 29(6):1310–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, Gerig G (2006) User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 31(3):1116–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S, Bauer C, Jennings D, Fennessy F, Sonka M, Buatti J, Aylward S, Miller JV, Pieper S, Kikinis R (2012) 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging 30(9):1323–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song HK, Wehrli FW, Ma J (1997) In vivo MR microscopy of the human skin. Magn Reson Med 37(2):185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodgson RJ, O’Connor PJ, Grainger AJ (2012) Tendon and ligament imaging. Br J Radiol 85(1016):1157–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du J, Chiang AJ-T, Chung CB, Statum S, Znamirowski R, Takahashi A, Bydder GM (2010) Orientational analysis of the Achilles tendon and enthesis using an ultrashort echo time spectroscopic imaging sequence. Magn Reson Imaging 28(2):178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiesinger F, Ho ML (2022) Zero-TE MRI: principles and applications in the head and neck. Br J Radiol 95(1136):20220059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Techawiboonwong A, Song HK, Magland JF, Saha PK, Wehrli FW (2005) Implications of pulse sequence in structural imaging of trabecular bone. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 22(5):647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wehrli FW, Perkins TG, Shimakawa A, Roberts F (1987) Chemical shift-induced amplitude modulations in images obtained with gradient refocusing. Magn Reson Imaging 5:157–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engström M, McKinnon G, Cozzini C, Wiesinger F (2020) In-phase zero TE musculoskeletal imaging. Magn Reson Med 83(1):195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Froidevaux R, Weiger M, Brunner DO, Dietrich BE, Wilm BJ, Pruessmann KP (2018) Filling the dead-time gap in zero echo time MRI: principles compared. Magn Reson Med 79(4):2036–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dremmen MHG, Wagner MW, Bosemani T, Tekes A, Agostino D, Day E, Soares BP, Huisman T (2017) Does the addition of a “Black Bone” sequence to a fast multisequence trauma MR protocol allow MRI to replace CT after traumatic brain injury in children? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38(11):2187–2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel KB, Eldeniz C, Skolnick GB, Commean PK, Eshraghi Boroojeni P, Jammalamadaka U, Merrill C, Smyth MD, Goyal MS, An H (2022) Cranial vault imaging for pediatric head trauma using a radial VIBE MRI sequence. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 10.3171/2022.2.Peds2224:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kralik SF, Supakul N, Wu IC, Delso G, Radhakrishnan R, Ho CY, Eley KA (2019) Black bone MRI with 3D reconstruction for the detection of skull fractures in children with suspected abusive head trauma. Neuroradiology 61(1):81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ljungberg E, Wood TC, Solana AB, Williams SCR, Barker GJ, Wiesinger F (2022) Motion corrected silent ZTE neuroimaging. Magn Reson Med 88(1):195–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eshraghi Boroojeni P, Chen Y, Commean PK, Eldeniz C, Skolnick GB, Merrill C, Patel KB, An H (2022) Deep-learning synthesized pseudo-CT for MR high-resolution pediatric cranial bone imaging (MR-HiPCB). Magn Reson Med 88(5):2285–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johansson A, Karlsson M, Nyholm T (2011) CT substitute derived from MRI sequences with ultrashort echo time. Med Phys 38(5):2708–2714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng W, Kim JP, Kadbi M, Movsas B, Chetty IJ, Glide-Hurst CK (2015) Magnetic resonance-based automatic air segmentation for generation of synthetic computed tomography scans in the head region. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 93(3):497–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.