Abstract

Organisms determine the transcription rates of thousands of genes through a few modes of regulation that recur across the genome1. In bacteria, the relationship between a gene’s regulatory architecture and its expression is well understood for individual model gene circuits2,3. However, a broader perspective of these dynamics at the genome-scale is lacking, in part because bacterial transcriptomics has hitherto captured only a static snapshot of expression averaged across millions of cells4. As a result, the full diversity of gene expression dynamics and their relation to regulatory architecture remains unknown. Here we present a novel genome-wide classification of regulatory modes based on each gene’s transcriptional response to its own replication, which we term the Transcription-Replication Interaction Profile (TRIP). Analyzing single-bacterium RNA-seq data, we found that the response to the universal perturbation of chromosomal replication integrates biological regulatory factors with biophysical molecular events on the chromosome to reveal a gene’s local regulatory context. While the TRIPs of many genes conform to a gene dosage-dependent pattern, others diverge in distinct ways, and this is shaped by factors such as intra-operon position and repression state. By revealing the underlying mechanistic drivers of gene expression heterogeneity, this work provides a quantitative, biophysical framework for modeling replication-dependent expression dynamics.

Bacterial gene regulation occurs primarily at the level of transcription5, and decades of research has produced a wealth of knowledge about RNA polymerase and its interactions with promoters, repressors, and activators of transcription. However, this work has been primarily based on measurements averaged across a population of millions of cells, thus limiting our resolution of gene circuits. Unlike in eukaryotic cells, transcription in rapidly proliferating bacteria occurs on a chromosome that is under continuous replication6,7. Although there has been some exploration of the effects of replication on individual genes8,9, the transcriptome-wide consequences of this perturbation are largely unknown10,11. Traditionally, measuring global gene expression during the replication cycle has been hampered by the requirement for analysis of synchronized populations at a bulk level, limiting this analysis to organisms such as Caulobacter crescentus12–14 where natural biological features facilitate synchronization, or to populations synchronized by batch synchronization methods such as starvation15 or temperature shift16 that may be both of questionable efficacy and liable to introduce artefacts17. Bacterial single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)18–21 has recently emerged as a tool to understand variation in gene expression in unperturbed, unsynchronized bacterial populations. By applying this approach to two distant species under rapid growth conditions, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, we uncovered unexpected drivers of gene expression throughout the cell cycle in prokaryotes.

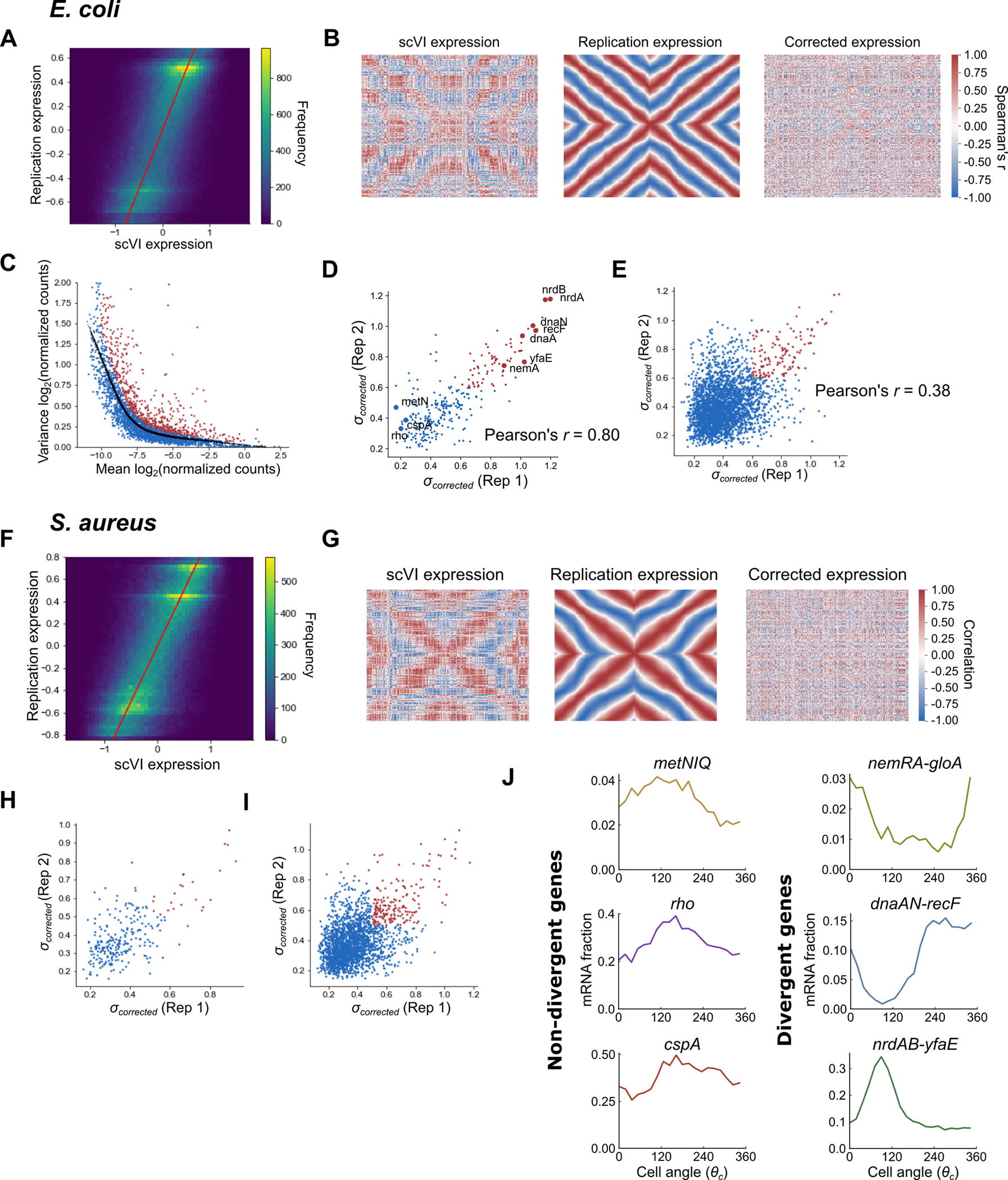

Global gene covariance in bacteria

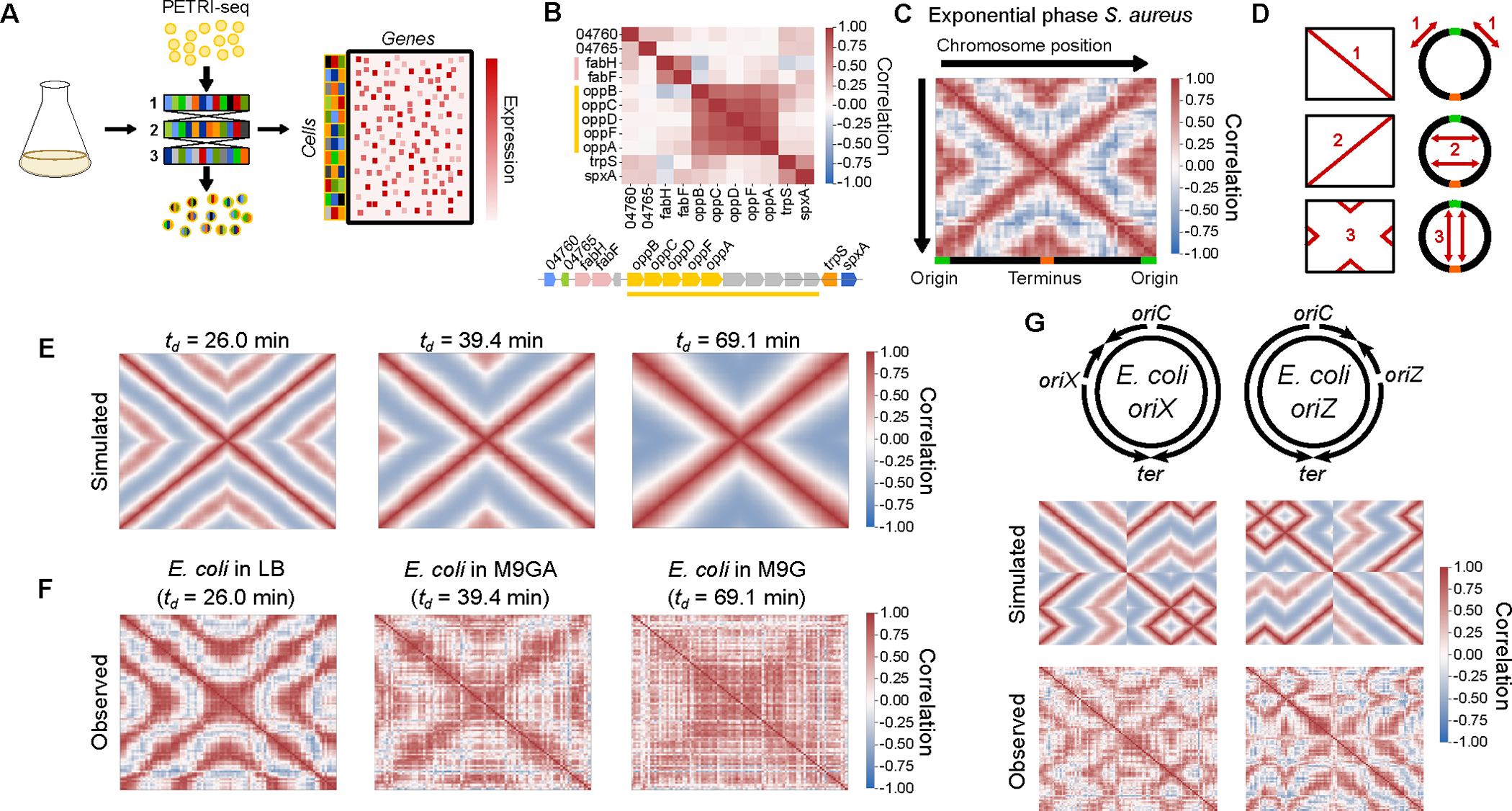

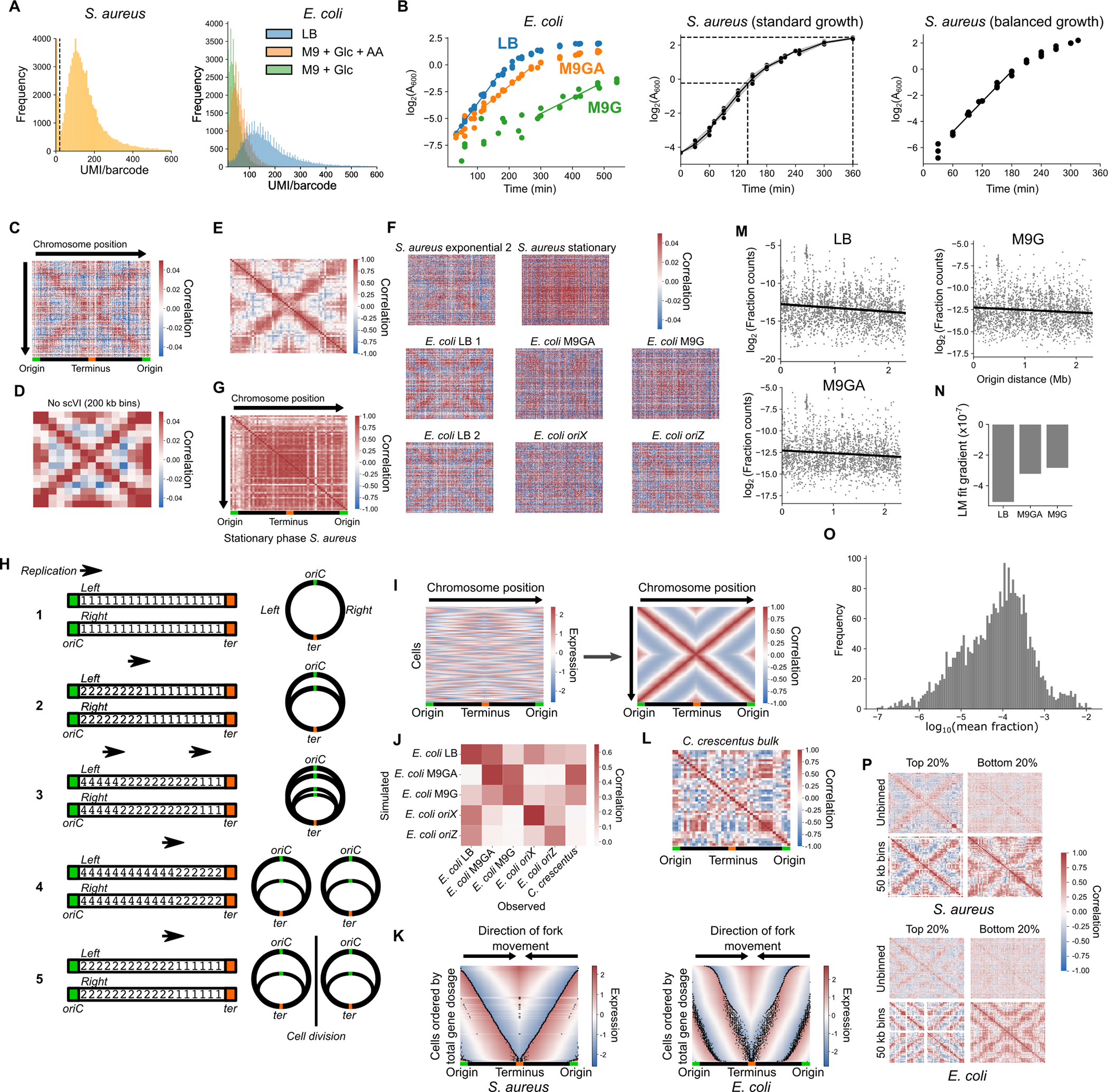

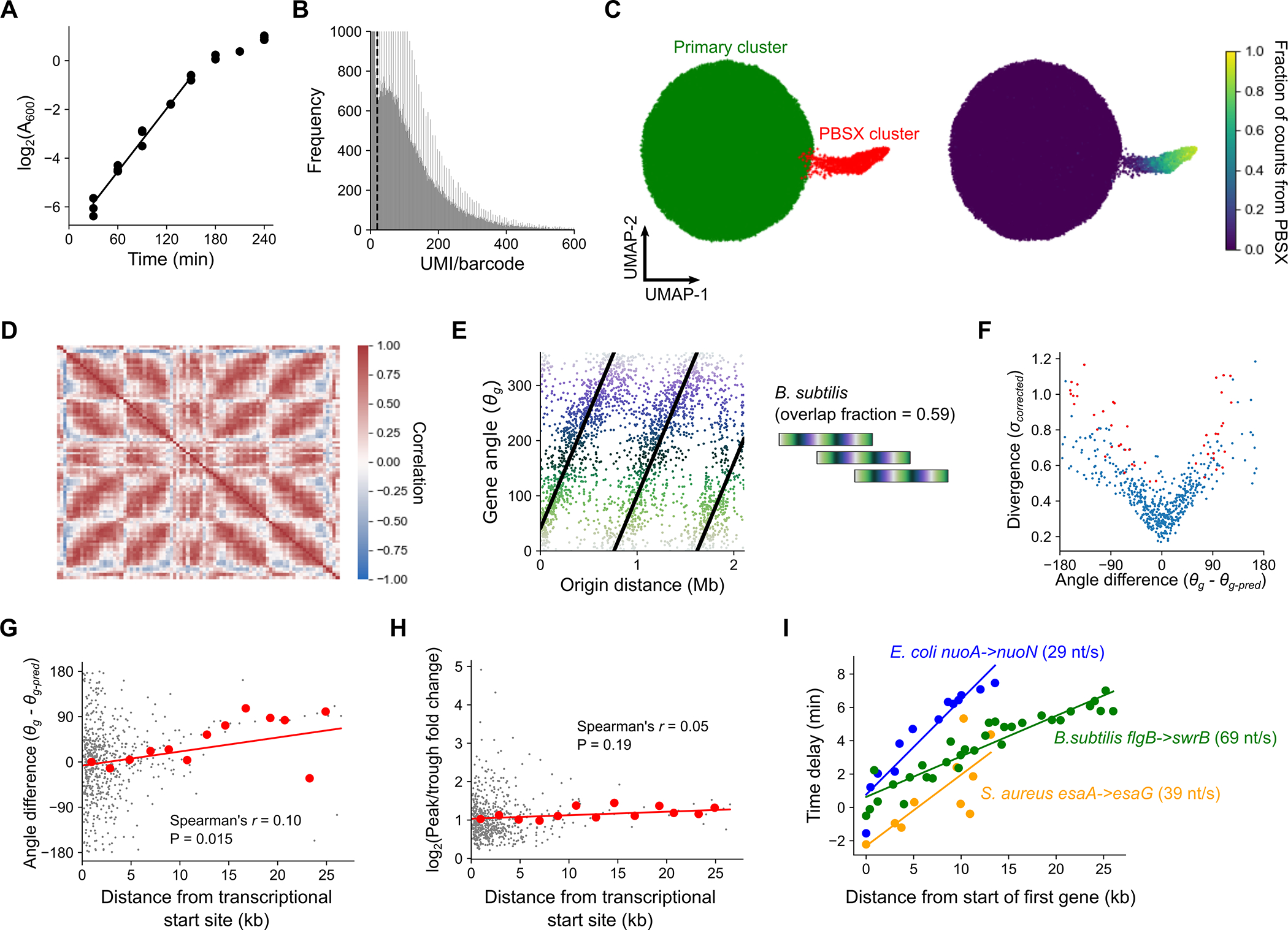

We first aimed to study gene expression at the single cell level in proliferating bacterial populations by applying the recently-described PETRI-seq18 method for scRNA-seq to S. aureus cells in exponential phase (Fig. 1A). We detected on average 135 transcripts across 73,053 individual cells (Extended Data Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 1). As the transcriptome measurements were highly sparse, we denoised them using the single-cell variational inference (scVI) method22. Studying gene-gene correlations on a local scale, we observed the expected high correlations between the expression profiles of genes residing in the same operon (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, when we investigated gene-gene correlations on a genomic scale, we discovered a striking “X-shaped” pattern of gene expression correlations (Fig. 1C). We can break this pattern into three major elements (Fig. 1D): 1) correlation between genes near to each other on the chromosome; 2) correlation between genes equidistant from the origin of replication; 3) correlation between origin-proximal and terminus-proximal genes. This pattern was also evident in a second independent dataset of 21,257 cells (Extended Data Fig. 1E), however we did not observe it for cells in stationary phase (Extended Data Fig. 1G), suggesting that it is a property of proliferating cells.

Fig. 1: scRNA-seq reveals a global pattern of replication-associated gene covariance.

A) PETRI-seq workflow18. B) Local operon structure is captured by gene-gene correlations (Spearman’s r) in S. aureus strain USA300 LAC. Operons are indicated by shared colors of genes. Gray genes indicate those removed by low-count filtering. C) Heatmap of the global gene-gene correlations according to chromosomal position. Spearman correlations were calculated based on scVI-smoothed expression averaged in 50 kb bins by chromosome position. D) Schematic depicting the individual elements of positive gene-gene correlations in (C) according to their chromosomal locations E) Simulated correlation patterns in unsynchronized E. coli populations at three different growth rates. F) Spearman correlations between scaled data averaged into 50 kb bins, as for (C) but for E. coli grown at indicated growth rates (see Supplementary Table 1 & Methods). G) Top: schematic of predicted replication patterns in two E. coli strains with ectopic origins. Middle: Predicted correlation patterns based on the copy number simulation. Bottom: Real correlation patterns in oriX and oriZ mutant strains, as in (C).

This proliferation-dependence and correlation of genes equidistant from the origin of replication (Fig. 1D), led us to hypothesize that the “X-shaped” pattern reflects the effect of DNA replication on gene expression. In the model organism E. coli, when the cell doubling time is less than the approximately constant ~40–50 minute period for one complete round of DNA replication from the origin to the terminus (the “C-period”), simultaneous overlapping cycles of replication occur6,23,24. This leads to growth rate dependence in replication patterns and suggests that any effects of replication on global gene correlations should also be growth rate-dependent. To test this, we developed a simulation to predict growth rate-dependent gene expression correlations arising from replication-dependent changes in gene dosage (Fig. 1E & Extended Data Fig. 1H–K). Of three growth rates simulated, the intermediate growth rate ( = 39.4 min) led to a pattern most similar to S. aureus (Fig. 1C). However, simulating faster growth produced a nested “multi-X” pattern resulting from overlapping cycles of replication, and slower growth greatly reduced origin-terminus correlations (Fig. 1E). When we measured expression patterns in E. coli grown at these three rates, we found that each pattern closely corresponded to its respective simulation (Fig. 1F, Extended Data Fig. 1J). This and further arguments (Extended Data Fig. 1L–P & Methods) demonstrate that replication-driven gene dosage changes are a plausible mechanism driving chromosome-wide expression correlation patterns.

To further test our ability to predict global gene expression correlations from expected replication patterns, we examined strains in which normal replication is perturbed. We studied two E. coli strains with ectopic origins of replication at either the 9 o’clock (oriX) or 3 o’clock (oriZ) positions in addition to oriC25–27. In these strains, replication was shown to initiate simultaneously at both native and inserted origins, while ending at the same terminus25. Again, our simulation effectively predicted the perturbed correlation patterns in these strains (Fig. 1G). Collectively, these results support the notion that DNA replication produces a predictable effect on transcriptional heterogeneity within a population of proliferating bacteria, and that this effect is sensitive to growth rate and genetic perturbations.

Cell cycle state inference

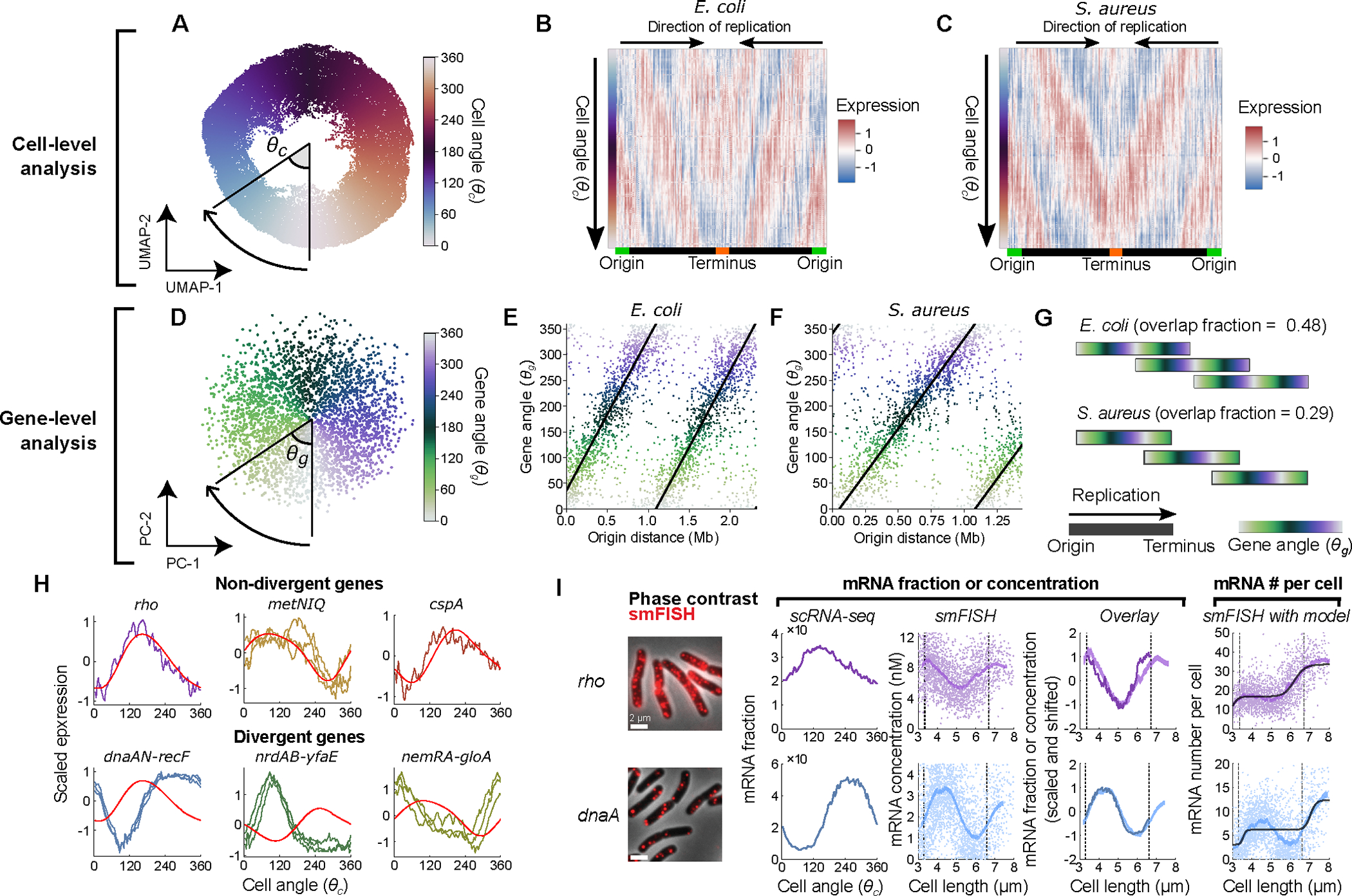

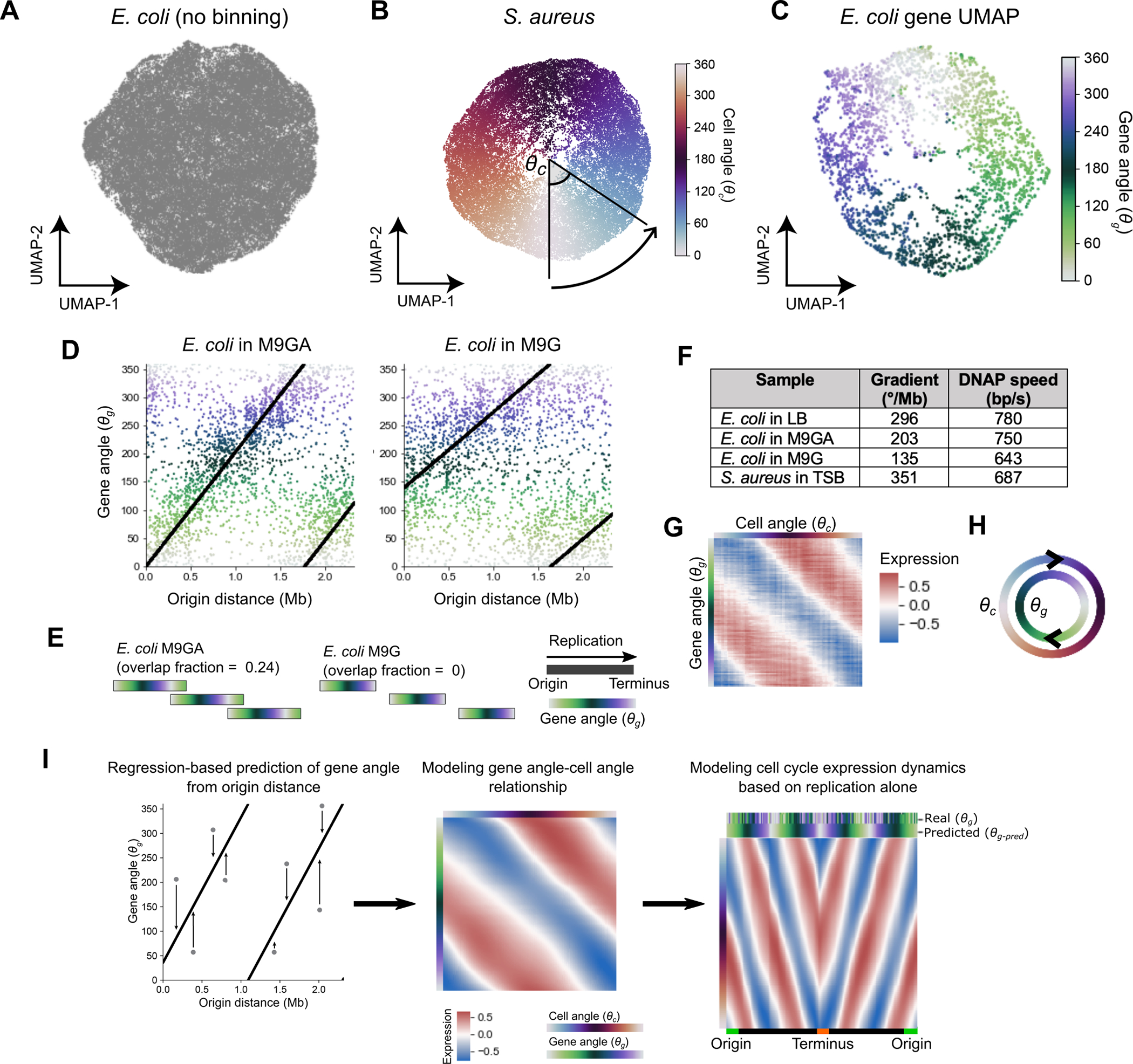

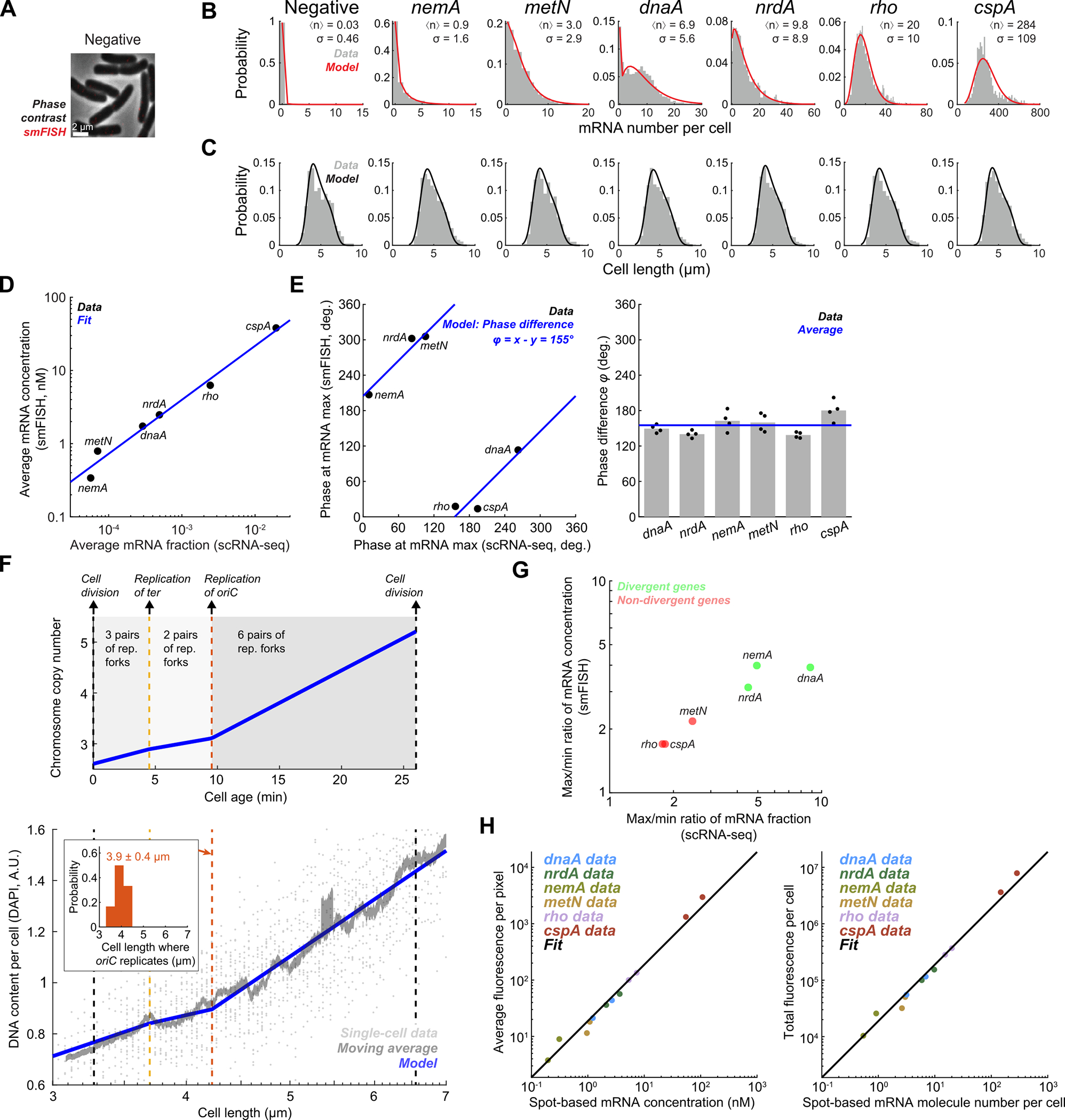

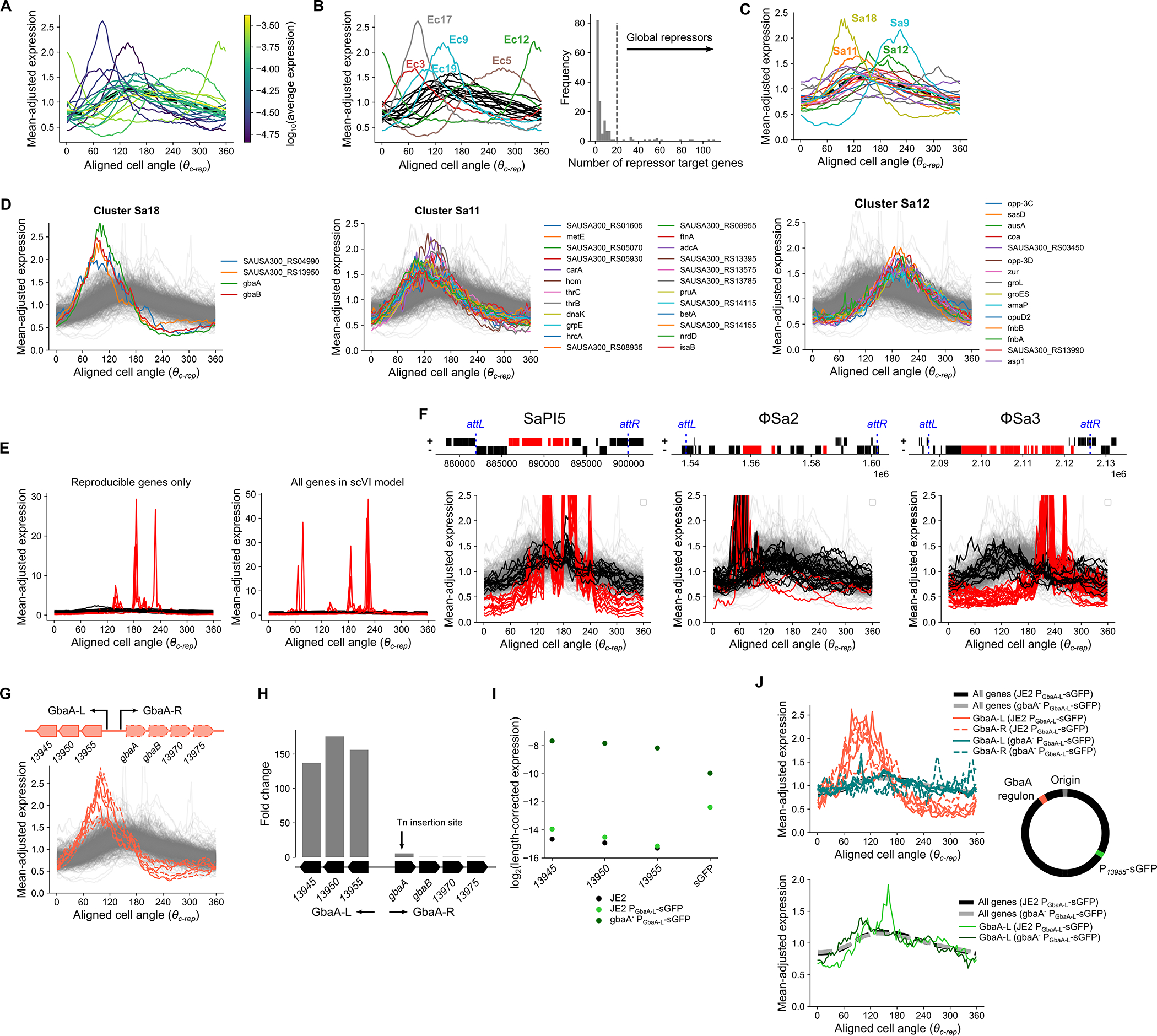

As our gene-level analysis revealed the effect of replication on gene expression, we next carried out a cell-level analysis that exploited this insight to resolve individual cells based on their replication state. To observe cell-cell relationships, we projected the transcriptomes of LB-grown E. coli cells, into a two-dimensional space, after collapsing the expression of individual genes into 100 kb regions to strengthen the chromosome position-dependent signal (as in Fig. 1C). We found a distinctive wheel-shape arrangement of the cells (Fig. 2A), indicating the capturing of a cyclical process occurring within the population. Hypothesizing that this wheel reflects the cell cycle, we computed a “cell angle” index – – which simply orders the cells according to their geometric angle from the center in this space. Examining gene expression as a function of , we observed waves of gene expression progressing from the origin to the terminus (Fig. 2B), suggesting that cells’ positions on this wheel indeed reveal their replication state. Similar periodical patterns were observed in simulated data (Extended Data Fig. 1K & F) and in S. aureus cells (Fig. 2C, Extended Data Fig. 2B). These data suggest that the transcriptome alone can be used to infer a cell’s replication state, and that this holds across different bacterial species.

Fig. 2: Cell cycle analysis of bacterial gene expression.

A) Two-dimensional projection by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) of LB-grown E. coli with expression averaged in 100 kb bins by chromosome position. Cell angle is the angle between UMAP dimensions relative to the center. B & C) Heatmaps of scaled gene expression in E. coli (B) and S. aureus (C) averaged in 100 bins by . D) Principal component analysis at the gene level; is defined as the angle between principal components (PCs) 1 and 2. E & F) The relationship between and origin distance for E. coli grown in LB (E) and S. aureus grown in TSB (F). G) Predicted replication patterns in LB-grown E. coli and TSB-grown S. aureus. Overlapping replication rounds lead to shared in simultaneously-replicated chromosomal regions. H) Expression of genes in operons across 100 bins averaged by . Expression is z-scores derived from scVI (jagged lines) or predicted as a replication effect (smooth, red lines). I) Comparison of scRNA-seq and smFISH data for two genes (see Extended Data Fig. 6A for more genes and further details). Left to right: 1) Microscopy images of E. coli cells labeled using gene-specific smFISH probes; 2) scRNA-seq expression shown as fraction of total cellular mRNA; 3) mRNA concentration, measured using smFISH, as a function of cell length. Single cell measurements are indicated alongside the moving average. Dashed lines indicate the inferred mean values at birth and division; 4) Alignment of scaled data from smFISH and scRNA-seq measurements; 5) Absolute mRNA copy number, measured using smFISH, as a function of cell length. Representative of two independent experiments.

As we observed that gene expression moved in waves during progression along the cell angle trajectory, we reasoned that we should also be able to order genes according to their expression profiles. We thus developed a similar ordering metric, which we denoted the gene angle, (Fig. 2D). Consistent with a role of replication in driving expression patterns, we observed a linear relationship between a gene’s and its genomic distance from the origin of replication in both species (Fig. 2E & F). This suggested that may be ordering genes according to their order of replication. The relationship however is not a simple ordering of genes from origin to terminus. For E. coli, we observed that the period of (i.e. the chromosomal distance associated with a 360° rotation) was much less than the full origin-terminus distance, meaning that genes at multiple positions on the origin-terminus axis had the same value (Fig. 2E). This intuitively relates to the fact that at high growth rates, multiple overlapping rounds of replication lead to simultaneous replication of genes at different distances from the origin. To quantify this further, we used the gradient between the and the distance from the origin to estimate an “overlap fraction” (Fig. 2G), meaning the fraction of one round of replication happening before the previous one has finished. When we compared E. coli at different growth rates, we observed that, in line with expectations6,23, decreasing proliferation speed in E. coli is associated with reduced overlap in rounds of replication (Extended Data Fig. 2D & E). In S. aureus, too, we observed that genes close to the origin and terminus had similar values, in line with our observation of a direct correlation between genes in these regions (Fig. 1C & D). This implies that S. aureus can also exhibit multiple rounds of simultaneous replication at fast growth rates.

If the gene angle captures the order of replication of a gene then it should be possible to compute the average speed of DNA polymerase using the doubling time and the -origin distance gradient. For E. coli in LB, this estimate was 780 bp/s (Extended Data Fig. 2F), which is very close to previously reported values of ~800 bp/s28,29. This would correspond to a C-period of ~50 min to replicate the full 2.3 Mb distance from origin to terminus. In S. aureus, we predict a slightly slower replication speed of 687 bp/s. However, its smaller genome (1.4 Mb from origin to terminus) means that a shorter C-period (~35 min) is inferred, leading to less overlap in rounds of replication than E. coli (Fig. 2G) despite very similar doubling times. Therefore, the gene angle provides a quantitative and interpretable description of the relationship between gene expression and global replication patterns. Given the relationship between and the cell angle, (Extended Data Fig. 2G & H) we could therefore devise an inference model that predicts expression of a given gene (by ) at a given point in the cell cycle (by ), based purely on its distance from the origin of replication (Extended Data Fig. 2I). This model effectively captured the global chromosome position-dependent expression pattern (Extended Data Fig. 4A & B) and, crucially, gives us a baseline prediction for determining whether or not individual genes behave according to global, replication-driven trends.

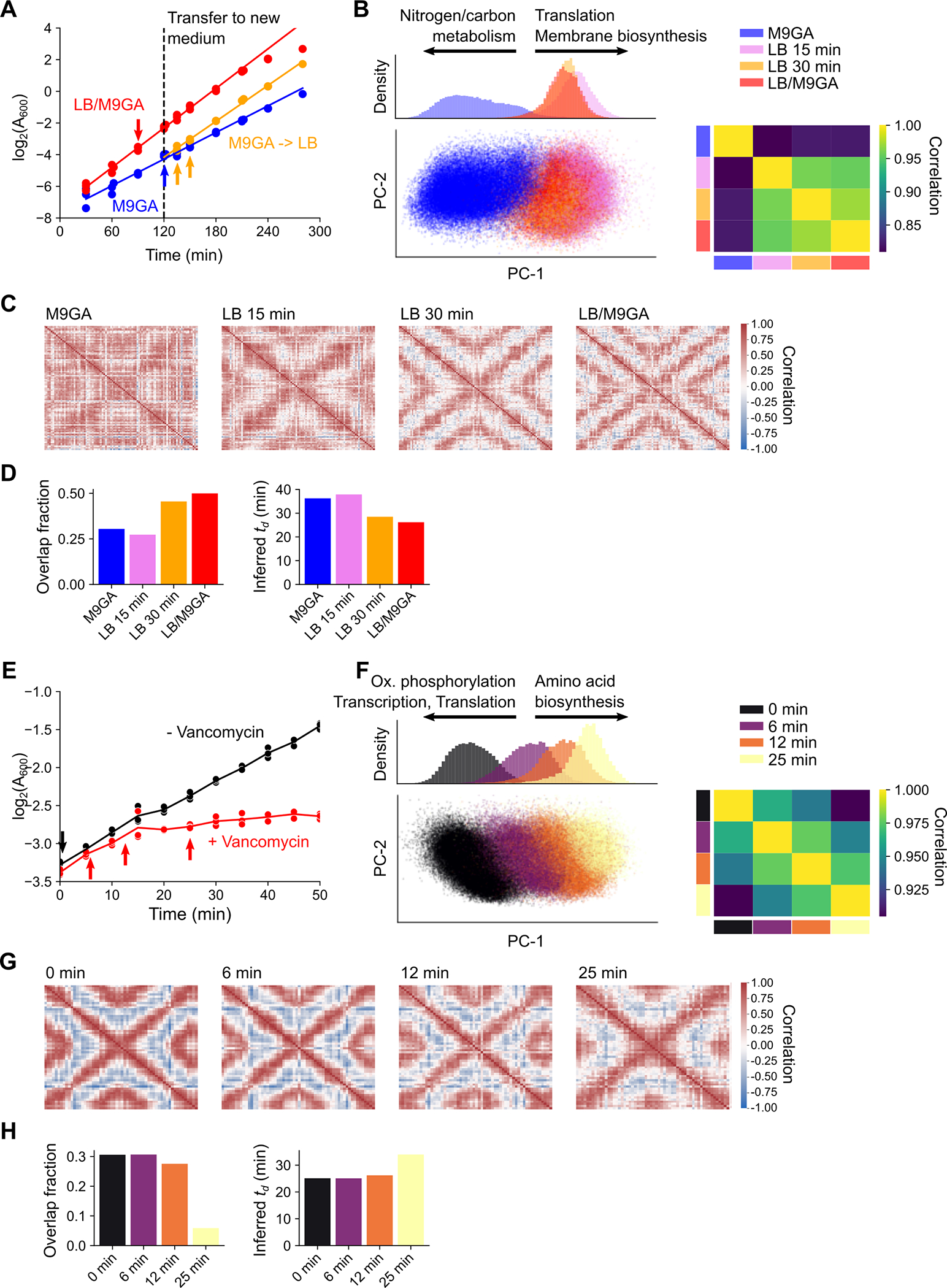

Finally, we wished to test whether we could use this framework to infer replication dynamics under changing growth rates. We considered two scenarios: a growth rate “shift-up” upon transferring E. coli into a richer growth medium30 (Extended Data Fig. 3A–D) and a “shift-down” upon exposing S. aureus to high concentrations of the antibiotic vancomycin (Extended Data Fig. 3E–H). Consistent with previous observations30, we found that in both cases while the transcriptional response to these stimuli happened very rapidly, the shift in the replication pattern (more- or less-overlapping in growth acceleration and deceleration, respectively), occurred only after a delay. Therefore, our analysis of replication dynamics from scRNA-seq data is not only robust to external perturbations to the global transcriptome, but also provides information on relative changes to replication patterns independent of other transcriptional changes.

Canonical and divergent gene expression

To test if the wheel-shaped distribution of cells indeed reflected cell cycle-dependent gene expression, we turned to single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH)8,31, a scRNA-Seq-independent approach that uses microscopy to detect individual transcripts in single cells. We first identified operons whose genes’ expression both did and did not fit the pattern predicted by our inference model (Fig. 2H). We then compared our measurements for genes within the selected operons to cell cycle-dependent gene expression measurements obtained using smFISH8,31. Between scRNA-Seq and smFISH, the overall expression levels of the genes were in close quantitative agreement (Extended Data Fig. 5D). The smFISH approach resolves E. coli cell cycle states by using cell length to infer cell age, thus defining the cell cycle relative to division timing (i.e. the time since cell birth)8. By contrast, we defined cell angle = 0 to be the assumed time of replication initiation (see Methods). As expected given these differing “start” points, we observed a phase shift in expression profiles between the two methods that was consistent across genes (Extended Data Fig. 5E). Modeling of total DNA content as a function of cell length supported that this phase shift was roughly consistent with our choice of = 0 as the point of replication initiation (Extended Data Fig. 5F), albeit with some discrepancy (see Methods). By correcting for this phase shift between methods, we aligned the scRNA-seq profile to that of the smFISH data (Fig. 2I, Extended Data Fig. 6A). In doing so, we observed that expression dynamics inferred by the two methods were highly correlated, confirming that our scRNA-seq approach indeed captures cell cycle-dependent expression.

When we analyzed cell cycle expression patterns of genes that did and did not diverge from the expected pattern (Fig. 2H), we noted a number of key differences. Both scRNA-seq and smFISH showed that the amplitude of cell cycle expression (i.e. the relative change between cell cycle minimum and maximum expression) was higher for these divergent genes than the non-divergent ones (Extended Data Fig. 5G). Moreover, while our scRNA-seq measurements capture only relative expression of a gene as a fraction of total cellular mRNA, the smFISH experiments additionally provide us with absolute abundance (i.e. mRNA copy number). This revealed that in non-divergent genes, there was a discrete twofold stepwise increase in expression (Fig. 2I, Extended Data Fig. 6C), consistent with genes that are sensitive to gene dosage but otherwise exhibit constant transcription rates8. Divergent genes, however, did not conform to this simple step function (although there was variation between replicates in the low-expressed nemA, Extended Data Fig. 6A & C). These observations support an interpretation that the inference model-predicted pattern corresponds to a canonical cell cycle expression pattern driven by gene dosage: genes that fit this pattern increase in expression only upon their replication, whereas divergent genes are governed by additional factors, leading to a higher amplitude in cell cycle expression than be explained by copy number effects alone.

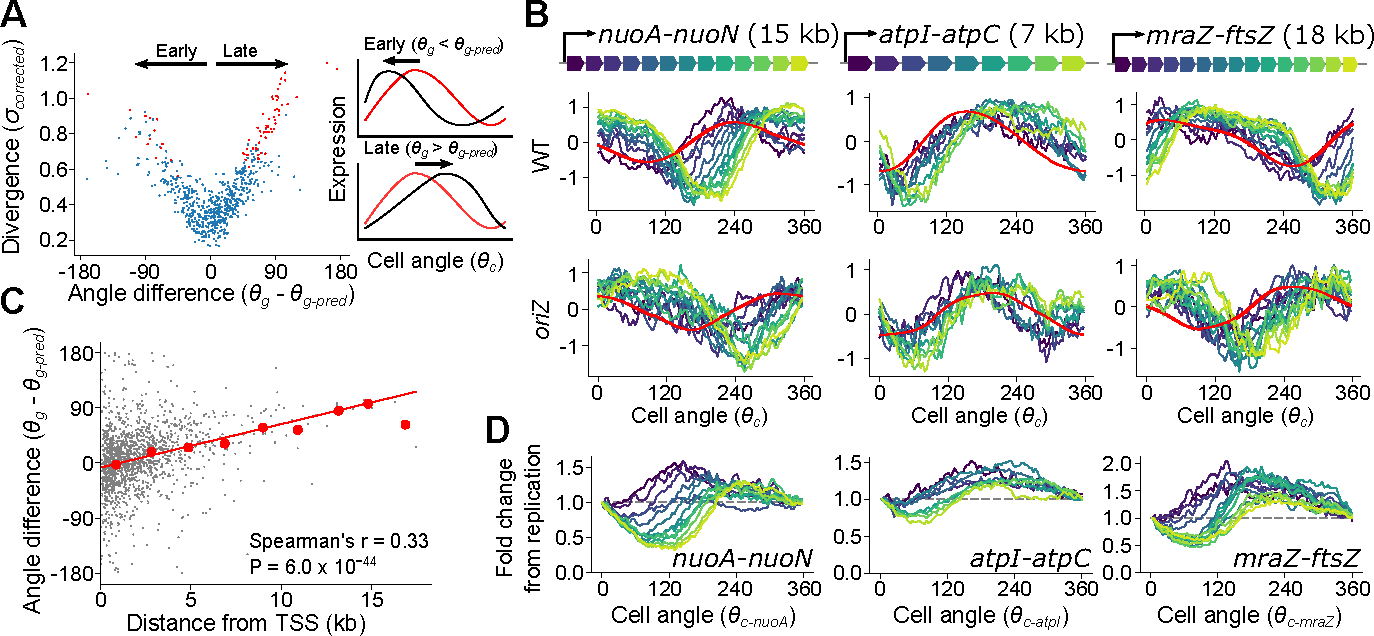

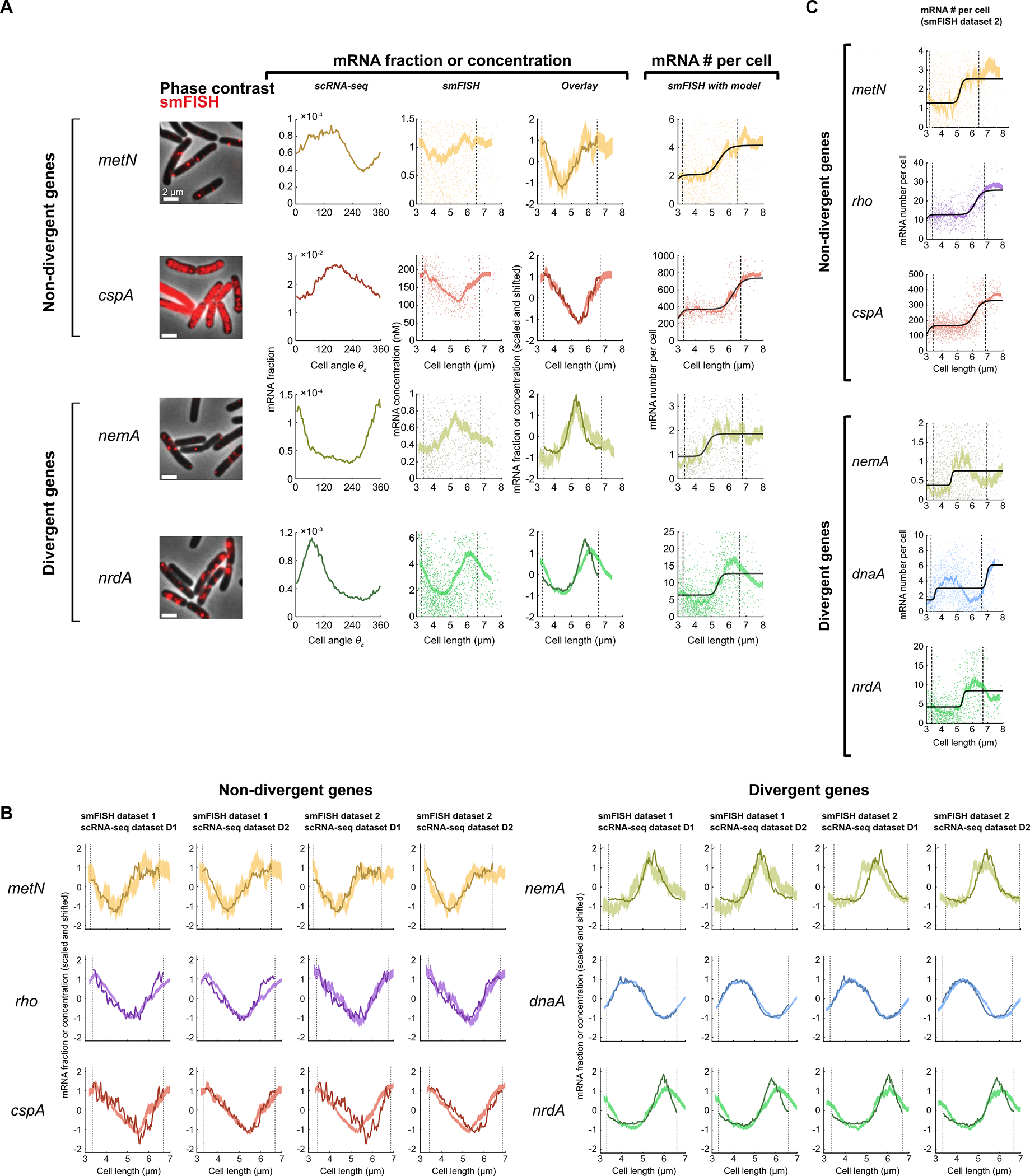

Expression timing and promoter distance

We next investigated those genes whose phase in cell cycle expression differed from predictions. Divergent genes can vary in phase of expression by peaking either earlier or later in the cell cycle than predicted (Fig. 3A). In E. coli, we observed a systemic bias where the majority of divergent genes showed delayed expression, meaning that the peak of expression was later than expected based upon chromosomal location (Fig. 3A). Many of these genes were encoded in large operons, such as those involved in energy biogenesis (e.g. nuo and atp operons) and cell surface synthesis (e.g. the mraZ-ftsZ operon). We found that genes with a more distal position within these operons exhibited a greater delay (Fig. 3B, Extended Data Fig. 7A). Globally, this correlation between the delay – measured as “angle difference” (see Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 5) – and distance from the transcriptional start site (TSS) pattern was highly significant (Fig. 3C). Moreover, this delay was clearly relative to the timing of replication: in genes whose replication-predicted pattern changed in the oriZ mutant, expression also shifted in this strain such that the delay was relative to their new replication time (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3: Intra-operon position produces a characteristic delay in expression dynamics in E. coli.

A) Left: Plot of divergence from predictions against the difference between predicted and observed angles, with divergent genes in red. Shown for all genes with high cell cycle variance (see Methods). Angle difference () represents whether a gene is expressed earlier or later ( than expected (black arrows). Right: Schematic of angle difference effects. Black and red lines represent observed and predicted cell cycle expression, respectively. B) Cell cycle expression of operons containing “delayed” genes, colored by position within the operon. Model-predicted expression is represented in red. Shown for WT and the oriZ mutant. C) Plot of distance from the transcriptional start site against angle difference. Red line indicates the linear model fit and red points indicate averages of 2 kb bins. The P-value was calculated based on a two-sided hypothesis test (see Methods). D) Fold change in expression of genes within an operon relative to expression at the operon’s predicted time of replication. Genes are colored by their position within the operon and cell angle is adjusted so that the zero point is the predicted replication time of the first gene within each operon (nuoA, atpI, mraZ). Dotted gray lines indicate the level of expression upon replication.

We hypothesized that this delayed phenotype arises due to the time for RNA polymerase (RNAP) to reach genes after replication by DNA polymerase (DNAP) has occurred. The speed of RNAP has previously been estimated as ~40 nt/s8,32 in E. coli, much slower than the ~800 nt/s speed for DNAP28,29 (see also Extended Data Fig. 2F). By performing linear regression to measure the angle difference/transcriptional distance relationship (Fig. 3C) and converting into time by assuming that 360° is equivalent to one doubling time of 26 min, we inferred that distance from the TSS is associated with a delay that is consistent with an average RNAP speed of 35nt/s (33 nt/s and 38 nt/s in two replicates, Extended Data Fig. 7C). Therefore, our data support the hypothesis that when a gene is replicated, the time for its expression to increase to the higher-expressed state (due to higher gene dosage) correlates with the time for RNAP to reach that same gene after transcription from the replicated locus restarts.

In addition to the delay, however, we also observed that when examining how expression changes after an operon is replicated, genes close to the TSS immediately increase to a new higher state, as expected from the increase in gene dosage, whereas genes far from the TSS initially drop before then recovering to the new state (Fig. 3D). This manifests as an increasing cell cycle expression amplitude (peak expression vs trough expression) of genes far from their TSS, a trend that was present as a weak but highly significant correlation across the genome (Extended Data Fig. 7D). We can interpret this effect as follows: the replication of an operon produces local disruption of ongoing transcription33. For genes close to the TSS, expression can immediately resume at a higher rate from the duplicated locus. However, for genes far from the TSS, the new rounds of transcription may take several minutes to reach them, during which time a drop in expression is observed due to mRNA degradation. An implication of this is that internal promoters should buffer the effects of replication-associated loss of transcription. While the nuo operon contains no well-evidenced internal promoters, a substantial amount of transcription at the distal end of the mraZ-ftsZ operon is driven from internal promoters34,35. Therefore, expression amplitude rises linearly with TSS distance in the nuo operon whereas it tails off at the location of the internal promoters within the mraZ-ftsZ operon (Extended Data Fig. 7B), supporting our inference. Thus internal promoters may prevent excessive fluctuations in key genes such as ftsZ, which determines the timing of cell division36, and in principle it may even be possible to use these signatures to infer the presence of internal promoters within operons.

Finally, we asked whether similar trends could be observed in S. aureus. In contrast to E. coli, we observed neither an excess of “delayed” genes among the divergent genes (Extended Data Fig. 7F), nor an effect of distance from the TSS on expression amplitude (Extended Data Fig. 7D). We did however measure a delay as a function of distance from the TSS (Extended Data Fig. 7C), which we found to be consistent with an RNAP elongation speed of 71 nt/s (59, 64, and 92 nt/s across three replicates). The difference between the two species persisted even when operons were redefined according to unified criteria37 (Extended Data Fig. 7E). The RNAP speed of S. aureus has not been measured, but in B. subtilis, which is, similarly to S. aureus, a firmicute of the order Bacillales, experimental measurement of RNAP by a reporter system suggested that it was substantially faster (75–80 nt/s) than its counterpart in E. coli measured by the same method (~48 nt/s)38,39. Therefore, we tested whether we could use our method to detect this faster RNAP speed in B. subtilis (Extended Fig. 8). Despite multiple additional sources of heterogeneity in this species – including multicellular chain growth, prophage activation and sporulation programs19 – we nevertheless resolved a highly overlapping replication pattern (Extended Data Fig. 8D & E) from which we inferred a DNAP speed of 632 bp/s (631 and 634 bp/s across two replicates), which is close to that of S. aureus and, as previously reported40, ~80% of the E. coli speed. However, as predicted, we estimated a faster RNAP speed for B. subtilis of 96 nt/s (Extended Data Fig. 8G) (95 and 98 nt/s in two replicates). Similar trends could be observed across species for individual long operons (Extended Data Fig. 8I). Therefore, the intra-operon effect we observe in E. coli is not conserved across species, and likely follows from variation in RNAP elongation speed.

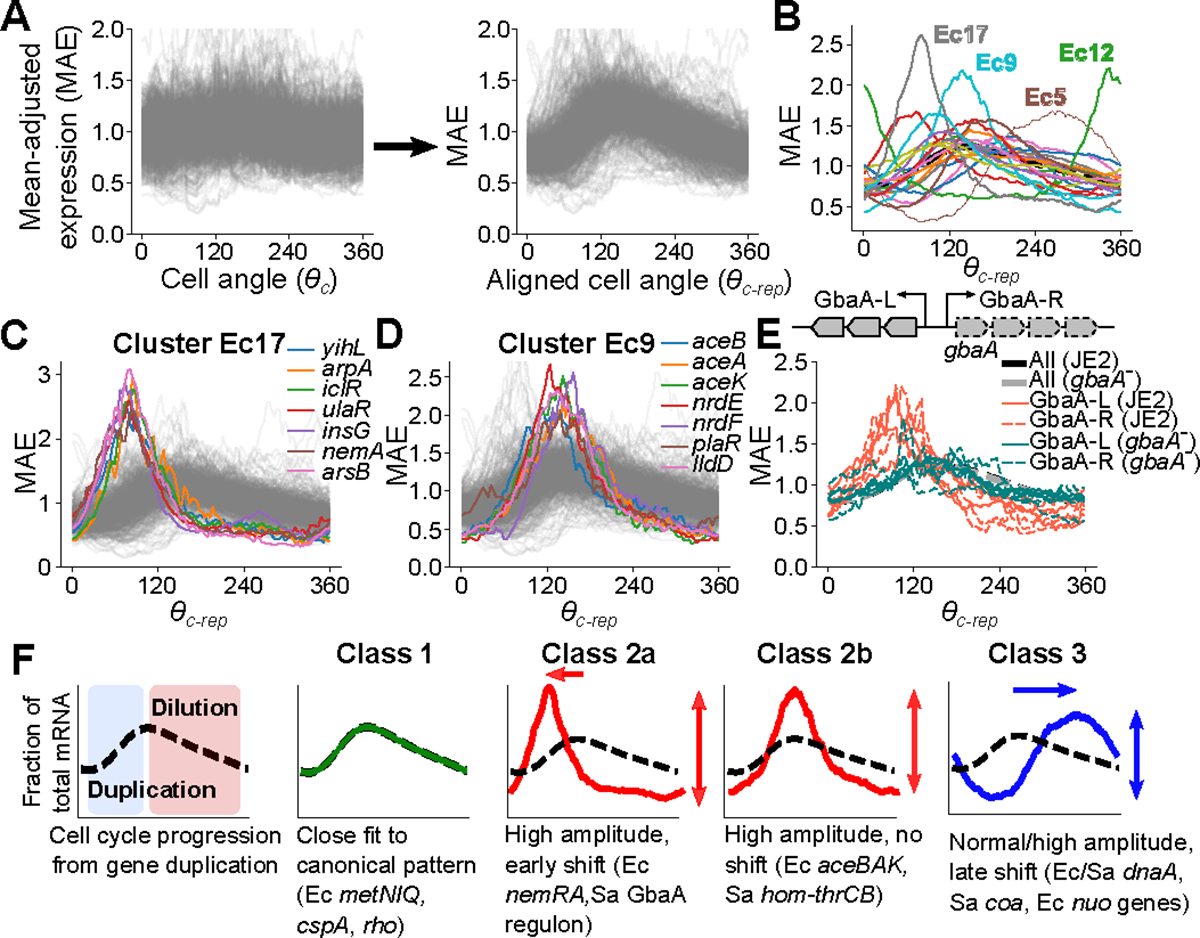

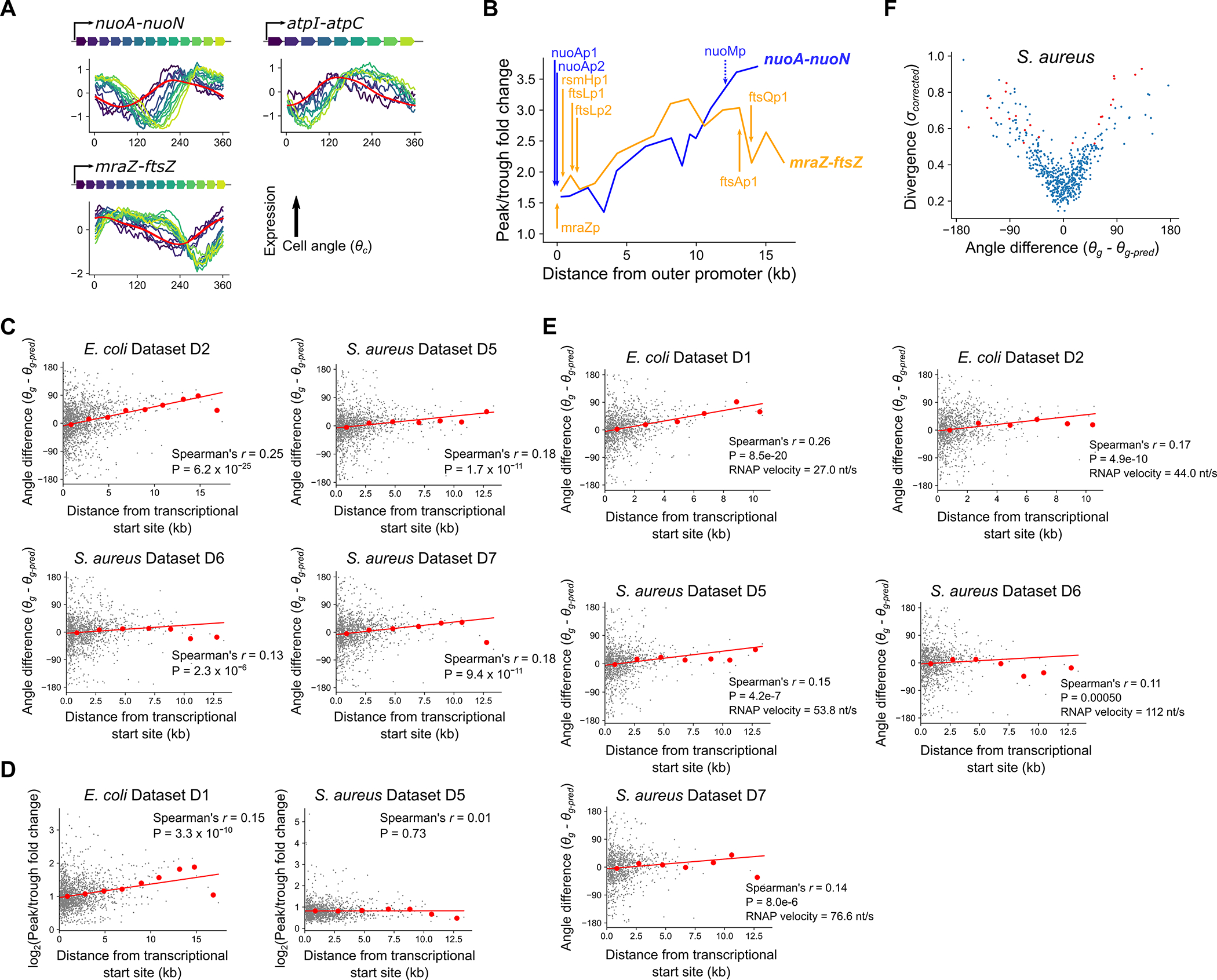

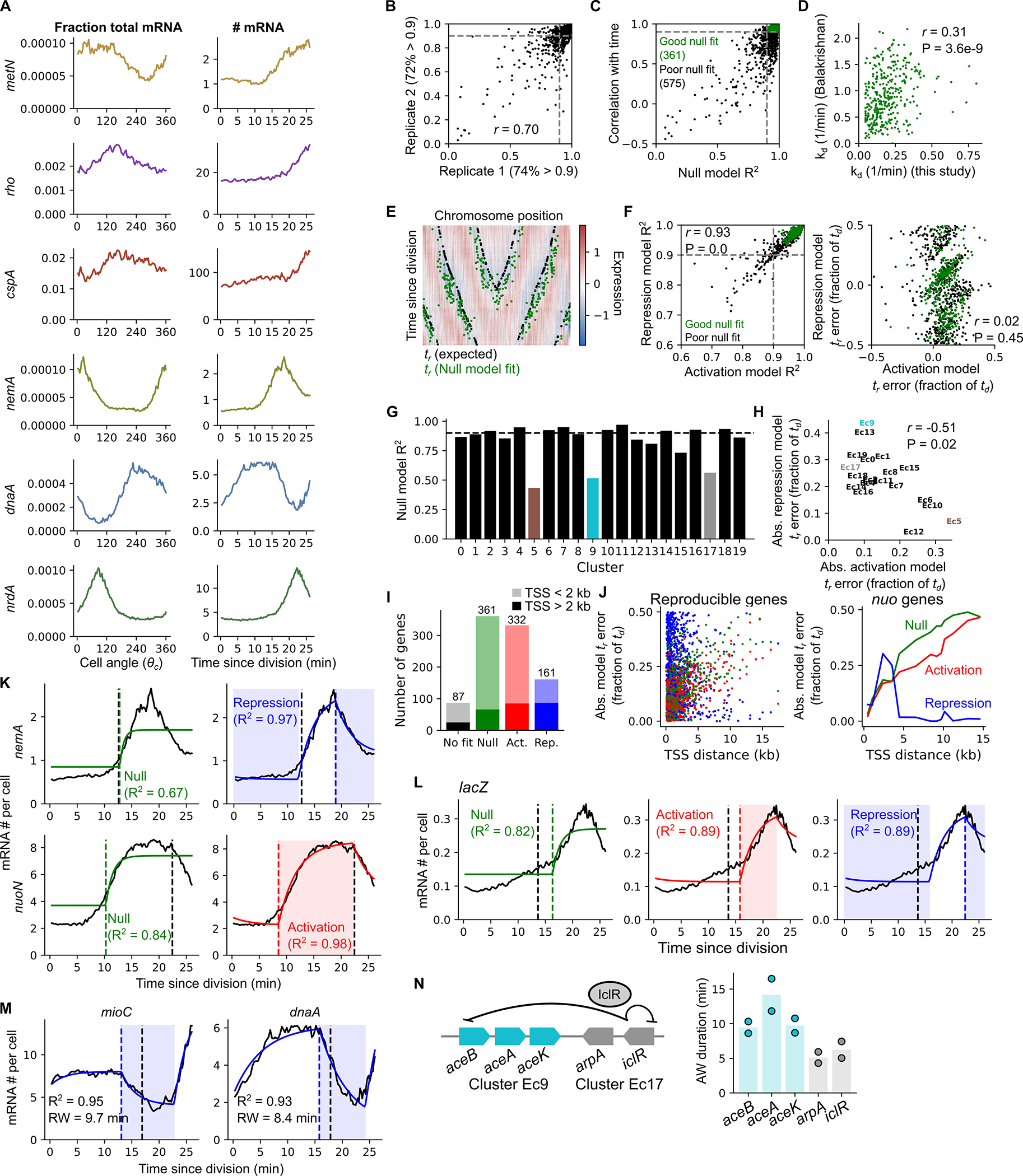

Repression-driven expression pulses

Our analysis above revealed recurrent, replication-coupled patterns of cell cycle expression. To enable comparison of replication-coupled expression dynamics across different chromosomal loci, we aligned their mean-standardized expression profiles such that zero on the x-axis represents the point of a gene’s replication and the cell cycle progression from this point (Fig. 4A). We refer to this as the “Transcription-Replication Interaction Profile” (TRIP) and propose that it enables an explicit focus on the transcriptional response of each gene to the perturbation caused by its replication, independent of when in the cell cycle that gene is replicated. Among genes whose cell cycle expression was reproducible across replicates (Supplementary Table 6), the profile for most genes was similar, rising rapidly due to a doubling of gene dosage before declining as a relative fraction of the transcriptome as other genes are replicated and hence increase their own fractional abundance. Many genes, however, exhibited patterns that could not be explained by gene dosage effects alone.

Fig. 4: Transcription-replication interaction profiles (TRIPs).

A) Procedure to generate TRIPs. Expression is mean-adjusted by division of each gene by its mean (left), then aligned by rotating cell angle so the predicted replication time expression is at zero (see Methods). B) Average aligned expression profiles for 20 k-means clusters in E. coli. The dotted black line represents average expression across all reproducible genes. C & D) Plots of individual genes from the indicated clusters. E) TRIPs for GbaA regulon genes in JE2 and a gbaA− (SAUSA300_RS13960) transposon mutant. Operon structure is shown above. Thick black and gray lines represent average expression across all reproducible genes. F) TRIP Classes. Left: Canonical TRIP driven by gene dosage. Other panels: Archetypal classes of TRIPs that adhere to (Class 1) or diverge (Classes 2–3) from this pattern. Genes in E. coli and S. aureus are represented as Ec and Sa, respectively.

To identify the range of behaviors, we partitioned E. coli genes into 20 clusters based on their TRIPs (Fig. 4B). Of these, several exhibited particularly divergent expression, differing from the expected pattern in both the timing of their dynamics (e.g. when their peak or trough expression occurs) and the amplitude (i.e. the relative difference between maximum and minimum cell cycle expression). Cluster 12 in E. coli (Ec12) comprised the nrdAB-yfaE operon and cluster Ec5 contained the dnaAN-recF operon and other delayed expression genes, including some nuo genes. Cluster Ec17 showed an early-peaking pulse in expression with greater amplitude than most genes (Fig. 4C). Many genes in these clusters were in operons that encode repressors, at least some of which have autorepressive activity (including nemA, which is co-transcribed with the autorepressor nemR) (Supplementary Table 4). Cluster Ec9, whose members peak at the expected time but show increased amplitude (Fig. 4D), also included several repressed genes (Supplementary Table 4), such as the glyoxylate shunt operon, aceBAK, which is IclR-repressed. Other clusters composed of low-expressed genes showed similar trends (Extended Data Fig. 9A), and low-expressed clusters that showed high amplitude were enriched for repressor targets (FDR = 0.1, Extended Data Fig. 9B). This suggested a broad association between repression state and replication-associated pulses in gene TRIPs.

When we extended this analysis to S. aureus, we noted extreme divergence in TRIP clusters within the core genes of genome-integrated mobile genetic elements (MGEs) (Extended Data Fig. 9E & F). Beyond MGE genes, however, a range of behaviors were evident, similar to those observed in E. coli (Extended Data Fig. 9C). For example, we observed high amplitude and delayed dynamics in cluster S. aureus (Sa) 9, comprised of dnaAN, as well as several high-amplitude clusters (Extended Data Fig. 9D). Sa18 was almost exclusively composed of genes in the GbaA regulon (Extended Data Fig. 9G). In contrast, cluster Sa12 showed delayed dynamics (Extended Data Fig. 9D). Notably, this included several genes involved in stress and virulence.

We reasoned that transcriptional repression could be driving the high amplitude pulses observed for TRIPs of genes in certain clusters (Ec9, Ec17, Sa11, Sa18), because of the enrichment of repressors and the low expression levels among high-amplitude clusters (Extended Data Fig. 9A & B), and based on previous observations8,41,42. Therefore, we focused on genes of the S. aureus GbaA regulon (Extended Data Fig. 9G), which showed a particularly strong early pulse in expression. This regulon consists of two oppositely-oriented operons (referred to here as “GbaA-L” and “GbaA-R”, Fig. 4E) that are repressed by GbaA. GbaA is an electrophile-sensitive transcriptional repressor encoded by gbaA within the GbaA-R operon43,44. To test whether GbaA repression was responsible for the divergent dynamics of its regulon, we compared wild-type TRIPs to those of a gbaA transposon mutant, where GbaA-mediated repression should be relieved. Since transposon insertion happens within the GbaA-R operon, transcription of this locus was disrupted. However, in the GbaA-L operon we observed a >100-fold increase in expression (Extended Data Fig. 9H) due to loss of repression. As predicted, this loss of repression was accompanied by a clear reversion of GbaA-L TRIPs to the expected pattern in the transposon mutant, as well as reduced expression amplitude (Fig. 4E). To further verify that relief of GbaA repression at the promoter was directly responsible for this change, we measured transcription of a reporter gene from the GbaA-L promoter at an alternative chromosomal locus. While repression by GbaA was less efficient at this locus than for native GbaA-L (Extended Data Fig. 9I), we nonetheless observed a spike in reporter expression on a wild-type JE2 background that was GbaA-dependent (Extended Data Fig. 9J). These observations suggest that repression drives the high-amplitude pulses in expression seen for low-expressed genes.

By comparing TRIPs across the genome, we identify several archetypal classes (Fig. 4F). Class 1 TRIPs reflect the canonical dosage-driven response. For genes outside this category, we observe divergence of TRIPs along two main axes: heterochrony, or differential expression phase (i.e. timing of expression changes), and heterometry, or differential amplitude (or “peak/trough ratio”). Many repressed operons exhibit heterometry (Class 2a & 2b), while a subset of these peak earlier than expected (heterochrony) (Class 2b). Genes can also exhibit heterochrony as a “delayed” expression profile (Class 3). Each class of TRIP may therefore reveal distinct features of local gene regulatory contexts.

Biophysical modeling of TRIPs

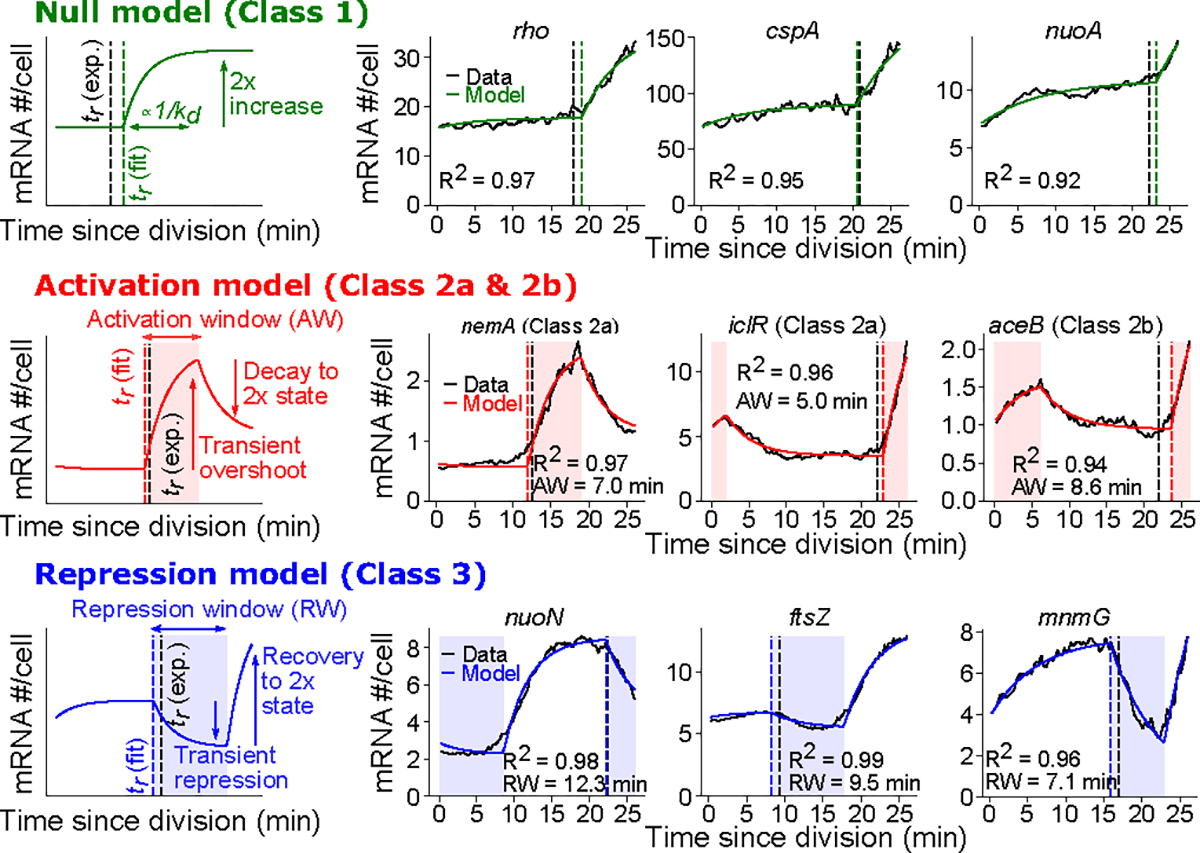

The presence of shared classes among TRIPs may suggest recurrent mechanistic drivers. To explore these hypothetical mechanisms in a quantitative manner, we interpreted the expression patterns using several biophysical models for cell-cycle dependent transcription. We first leveraged the procedure developed above of aligning scRNA-seq and smFISH data (Fig. 2I) to convert our E. coli scRNA-seq measurements (fraction mRNA as a function of ) to the estimated absolute mRNA copy number as a function of time since the last cell division (Extended Data Fig. 10A). This produced traces analogous to those measured by smFISH (Fig. 2I and Extended Data Fig. 6C). We next fitted those traces to a biophysical model11 where mRNA production rate is proportional to gene dosage. In this model, gene replication at time results in the doubling of mRNA level over a time inversely proportional to the mRNA degradation rate kd (Fig. 5). We found that 39% of reproducible genes were well fitted by this model (Extended Data Fig. 10B, C & I), with good consistency between replicates (Extended Data Fig. 10B). Moreover, the fitted values of kd were significantly correlated with published values (Extended Data Fig. 10D), and the inferred replication times, , mirrored the expectations based on each gene’s chromosomal location (Extended Data Fig. 10E). Thus, a large proportion of genes evaluated show cell cycle-dependent expression that is consistent with a simple biophysical model of dosage-dependent transcription.

Figure 5: TRIP classes can be explained by simple biophysical models of expression.

Fits of gene expression patterns to biophysical models of cell-cycle dependent transcription. Gene expression data from E. coli grown in LB was converted to absolute mRNA copy number as a function of time (see Methods). Black traces show observed expression, colored lines represent model fits. Vertical dashed lines indicate expected replication times based on predicted minimum gene expression (based on chromosome position) ( (exp.), black lines) or based on biophysical model fits ( (fit), colored lines) (see Methods). For each model, the left column is a schematic description of the fit and how it relates to model parameters (the “null” model parameters also apply to the expanded “activation” and “repression” models). The accompanying panels show these fits for individual genes (for two of these genes, nemA and nuoN, alternative plots of poorly fitting models are shown for comparison in Extended Data Fig. 10K).

To capture the dynamics of the TRIPs of genes with more complex expression patterns, we expanded our modeling approach. TRIP classes 2a & 2b exhibit “pulses” of expression upon replication (Fig. 4F). We thus developed an “activation model” in which mRNA production rate transiently increases upon replication before mRNA abundance decays back to a level driven by gene dosage (Fig. 5). Genes in high amplitude expression clusters Ec17 (Fig. 4C e.g. nemA, iclR) and Ec9 (Fig. 4D e.g. aceB) had a good fit (R2 > 0.9) and well-predicted gene replication times, (Extended Data Fig. 10H), but were poorly fitted by the null (dosage-driven) model (Extended Data Fig. 10G). Genes fitting to the activation model were also enriched for repressors (P < 10−4, hypergeometric test as in Extended Data Fig. 9B), whereas genes fitting to the null model were not (P = 1.00). Moreover, expression of lacZ was best-described by the activation model (Extended Data Fig. 10L). Previously, Wang and colleagues8 observed a replication-associated pulse in lacZ expression associated with the activity of its repressor, LacI, further supporting our inference that many genes fitting to the activation model are in a repressed state. Finally, the activation model enabled us to interrogate what determines whether a gene displays early-peaking behavior (Class 2a) or not (Class 2b). The IclR regulon encompasses both its own gene, iclR, and the neighboring aceBAK operon. While iclR peaks early (Class 2a, Fig. 4C), aceBAK genes peak at the expected time (Class 2b, Fig. 4D). In this case, model fits suggested that this difference is driven by a longer activation window for aceBAK, implying that it takes longer for IclR-dependent repression to be restored at aceBAK than at iclR (Extended Data Fig. 10N). Therefore, analysis of model fits can suggest useful hypotheses regarding specific regulatory circuits.

Neither of these models, however, can accurately describe genes with delayed expression timing (“Class 3” TRIPs). Specifically, each fails to predict the replication timing both in the delayed cluster Ec5 (Fig. 4B, Extended Data Fig. 10H) and for genes far from their promoter (Extended Data Fig. 10J). Since many of these genes show a drop in transcript abundance upon replication (Fig. 3D), we introduced a “repression model” that features a transient window of reduced mRNA production rate upon gene replication. This model effectively captured genes distant from their TSS, including for those genes at the far end of nuo and mraZ-ftsZ operons (Fig. 5, Extended Data Fig. 10J), while the promoter-proximal nuoA was sufficiently described by the null model (Fig. 5). Other genes with a “delayed” (Class 3) TRIP that were well-described by the repression model included genes immediately adjacent to the oriC locus (mioC and mnmG, Fig. 5, Extended Data Fig. 10M), as well as dnaA (Extended Data Fig. 10M), all of which have previously been suggested to experience transient repression around the time of their replication45,46. Of the genes not captured by the null model, the repression model explained fewer genes than the activation model, and most of the former genes’ repressed dynamics can be linked to their position within operons (Extended Data Fig. 10I). Thus, replication-dependent repression for other reasons appears to be a relatively unusual phenomenon. Overall, the simple biophysical modeling provides gene-level estimation of testable gene regulatory parameters, including mRNA decay, transcription activation and repression.

Discussion

Here we reveal the cell cycle transcriptional dynamics of rapidly dividing bacteria. Our work differs substantially not only from scRNA-seq analysis of cell cycle phase-specific genes in eukaryotic cells47, but also from previous studies of cell cycle transcriptomes in bulk, synchronized bacterial populations. It was previously suggested that, at least for ɑ-proteobacteria12,15, transcription of cell cycle genes was temporally regulated according to function. Our observations, however, suggest that the more general situation in prokaryotes, at least under rapid growth conditions, is one where cytoplasmic content is relatively invariant throughout the cell cycle48, and rather that the major perturbation to gene expression is the local effect of chromosomal replication itself. For example, cell cycle fluctuation in mRNA of ftsZ, the major cell division regulator, was described previously49,50. A direct link between ftsZ replication and transcriptional inhibition was postulated50, but the authors could not provide a satisfactory mechanistic explanation. Here, we provide a simple explanation of these augmented fluctuations in ftsZ abundance as the natural consequence of replication of a gene transcribed from a distant promoter (Fig. 3D), and not due to a cell division-coupled signaling event. While global factors may still play a role, such as competition for RNA polymerase between genes51, our work points to a central role of gene replication in driving cell cycle transcriptional dynamics.

We introduce the notion of the TRIP as a gene-level summary of the response of each gene to the perturbation of its own replication. This profile is analogous to the electrocardiogram (ECG), a time-resolved electrical pattern whose sophisticated, quantitative interpretation yields a wealth of information about cardiac function. Similarly, by continuing to refine the capture and analysis of TRIPs we expect to gain an ever more detailed diagnostic picture of gene regulation. Presently, we can distinguish a number of broad classes of TRIPs (Fig. 4G). For many genes, expression changes upon replication are sensitive primarily to copy number increases, and their dynamics can be described simply by their mRNA production and decay rates, as well as their replication timing. Other classes exhibit heterometry (here, primarily high amplitude) and heterochrony (early or delayed expression) that reveal important features of their regulatory environment, from repression state to promoter usage. These models, however, can be extended to other regulatory motifs. For example, many operons with genes displaying particularly strong “pulses” of expression upon replication are under autorepression (Supplementary Table 4), a network motif that facilitates rapid peaking of expression52. Biophysical models that can account for these specific motifs will allow us to both test and generate increasingly specific hypotheses about the regulatory context of a gene. While a gene’s fit to a specific biophysical model does not automatically entail a specific regulatory mechanism, nevertheless it places constraints on the plausible molecular processes leading to that TRIP. Crucially, the ability to reveal regulatory motifs without genetic perturbations, as well as to infer relevant global parameters such as DNAP and RNAP speeds, will allow expansion of our approach across non-model organisms or strains where the regulatory network is poorly characterized. We expect that the rapid improvement in scale and capture efficiency of bacterial scRNA-seq methodologies4,53–55 will allow us to perform ever deeper and more quantitative analyses.

Single cell analysis of eukaryotic cells has led to the development of a suite of analysis tools based principally on clustering and interpreting cell populations from specific marker genes56. While these approaches may be applicable to prokaryotes in certain circumstances, a hallmark of bacterial systems biology has been the use of quantitative, model-driven analysis of gene regulation and physiology2,57. This arises from both the simplicity of bacteria and the reproducibility - with careful experimental design - of bacterial measurements. Physically-inspired modeling has been applied to eukaryotic scRNA-seq, particularly in the context of RNA velocity58, but in practice these approaches are typically used to infer cellular behaviors such as developmental processes59. Our work demonstrates that bacterial scRNA-seq can produce quantitative estimates of molecular-level dynamics on a genome-wide scale and in a wide range of organisms. Our cell cycle analysis and TRIP frameworks, however, are likely only the first examples of such quantitative analyses now enabled by single-cell technologies.

Methods

Bacterial strains and media

Strains used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All E. coli strains (a gift from Dr. Christian Rudolph) and B. subtilis (ATCC) were routinely grown in modified Luria Broth (LB) (1% tryptone (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5% yeast extract (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.05% NaCl, pH adjusted to 7.4)26. For growth in minimal media, an M9 base (1X M9 minimal salts (Gibco), 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM CaCl2) was supplemented with 0.4% glucose (M9 + glucose: M9G) or with both 0.4% glucose and 0.2% acid casein peptone (Acros Organics) (M9 + glucose + amino acids: M9GA). All S. aureus strains were routinely grown in Bacto tryptic soy broth (TSB) (BD Biosciences). The gbaA transposon mutant was provided by the Biodefence and Emerging Infections (BEI) Resources Repository (cat. # NR-46898).

Growth curves and harvesting for PETRI-seq

All growth experiments were performed at 37° with shaking at 225 rpm.

Constant growth conditions

Strains were grown overnight in LB (E. coli & B. subtilis) or TSB (S. aureus). For initial experiments with S. aureus (Datasets D3 & D4), strains were diluted to an A600 value of 0.05 in prewarmed TSB, after which A600 was measured at the times specified. A600 was measured on a BioMate 3S spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). For experiments with S. aureus in balanced growth (Datasets D5-D8), overnight cultures were diluted in TSB first to 0.005, then after 3 hr diluted again to 0.005 before measuring A600 at the time intervals specified. Growth of B. subtilis was the same except with LB used as the growth medium. For E. coli growth curves, strains were diluted to an A600 value of 0.05 and incubated for 2 hr in the desired medium then diluted again in the same prewarmed medium to an A600 value of 0.005, after which A600 was measured at the time intervals specified. Where E. coli cells were diluted into a different medium, cells were washed once with PBS prior to dilution. To measure growth rate, a linear model log2(A600) ~ mT + c was calculated for the linear portion of this relationship (where T is the time in minutes) using the LINEST function in Microsoft Excel and the doubling time in minutes was calculated as 1/m. All doubling times are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

For harvesting for PETRI-seq, cells were grown as described except that after specific time intervals (for S. aureus, 2 hr 20 min in initial experiments, 1 hr 30 min in balanced growth experiments; for E. coli, 2 hr, 3 hr, and 7 hr in LB, M9GA, and M9G, respectively, when growth rates appeared constant (Extended Data Fig. 1B); for B. subtilis, 1 hr 30 min) cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspension in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. For S. aureus initial experiments, centrifugation was at 10,000 × g, 1 min at room temperature and for E. coli, B. subtilis, and balanced growth S. aureus experiments, centrifugation was at 3,220 × g, 5 min, 4°C. For B. subtilis, because sensitivity in the transcriptome to cold shock was previously noted upon gradual cooling during centrifugation at 4°C19, cells were initially cooled to <10°C by rapid agitation in a dry ice ethanol bath followed by retention on ice to prevent further transcriptional changes after harvesting.

For growth under perturbed conditions, see SI Methods Section “Growth perturbation conditions”.

PETRI-seq

PETRI-seq was carried out as described previously18 with modifications as described in the SI Methods Section “PETRI-seq modifications”.

Analysis of PETRI-seq data

Pre-processing of scRNA-seq data

Initial demultiplexing of barcodes, alignment, and feature quantification was performed using the analysis pipeline described in 18 except that feature quantification was performed at the gene level rather than operon level. Reference sequences and annotations were obtained from Genbank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). E. coli reads were aligned to the K-12 MG1655 reference assembly (GCA_000005845.2), S. aureus to the USA300_FPR3757 reference assembly (GCF_000013465.1), and B. subtilis to the 168 reference assembly (GCF_000009045.1). After initial processing, counts by cell barcode were pooled across different libraries (no batch effects were noted between libraries) and initial filtering was performed using Scanpy v1.7.160. Barcodes with UMI below a threshold (10 for Dataset D9 rep 2, 15 for Dataset D1, D2, D4, and D10 (all samples but M9GA); 20 for Dataset D3, D5–7, D9 rep 1, and D10 M9GA, 40 for Dataset D8) were removed, as well as any genes with fewer than 50 UMI across all included barcodes (100 for Dataset D3 & D9). Note that within the main text, we refer to UMI as simply “transcripts” for the sake of clarity, although we acknowledge that with random priming more than one unique read could originate from a single mRNA molecule.

Data denoising and generation of gene-gene correlations

To generate the denoised representation of the data, scVI v0.9.022 was applied with the following hyperparameters, chosen through grid search to distinguish between closely related S. aureus strains in a pilot dataset: two hidden layers, 64 nodes per layer, five latent variables, a dropout rate of 0.1, and with a zero-inflated negative binomial gene likelihood (other hyperparameters maintained as defaults). The model was trained with default parameters. Denoised expression values based on the scVI model were obtained using the scVI function “get_normalized_expression”. Initial gene-gene correlations without binning (Extended Data Fig. 1C & F) were calculated from scVI-normalized counts using the “get_feature_correlation_matrix” function. For correlations with position-dependent binning, scVI-normalized expression matrices were first log2-transformed and then converted to z-scores by mean centering followed by division by the standard deviation. For Extended Data Fig. 1D, this was carried out using raw counts normalized by total UMI per cell, and transformation by log2(x + 1) (to allow for zero values). After removing extrachromosomal genes, expression z-scores were averaged within bins (50 kb unless otherwise stated) and Spearman correlations between bins were calculated. For B. subtilis analysis, UMAP of initial scVI smoothed data revealed two clusters in initial analysis, with one cluster arising due to PBSX mobilization (Extended Data Fig. 8C). To generate the final scVI models, we removed this cluster and repeated scVI on the remaining cells. Note that for PBSX annotation and for annotation in S. aureus MGEs (Extended Data Fig. 9F), the online tool Phaster61 (phaster.ca) was used. For further discussion of evidence supporting our analysis of global gene correlations, see SI Methods Section “Quality assessment of global correlations in gene expression”.

Cell cycle analysis

Our quantitative framework describing gene expression as a function of replication cycle state (Fig. 2) is parameterized as the relationship between gene expression and two further parameters, cell angle (describing the position of cells within the cell cycle) and gene angle (describing the ordering of expression of genes within the cell cycle).

Derivation of cell angle, .

The position of cells within the cell cycle was determined as follows. First, scVI-derived z-scores (Section ”Data denoising and generation of gene-gene correlations”) were averaged into bins according to chromosomal location (50–400 kb bins, depending on the dataset). Binned data were then projected into two dimensions by UMAP analysis using the umap-learn v0.5.1 library in Python (https://umap-learn.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) with the “correlation” distance metric, generating the “wheel” plots shown (Fig. 2A & Extended Data Fig. 2B). To assign cells to a particular replication cycle phase based on their position, the embeddings were first mean-centered and then the angle of each cell relative to the origin between x and y coordinates in a two-dimensional UMAP embedding was calculated as tan−1(x / y), similar to the ZAVIT method our lab has described previously62,63. To get the expression by cell angle matrix used in Fig. 2B & C, scVI-denoised gene expression z-scores were then averaged within 100 equally spaced bins of to produce a cell angle-binned expression matrix. For UMAP without averaging, see Extended Data Fig. 2A.

Derivation of gene angle, .

After averaging gene expression within 100 equally spaced bins of (as in Fig. 2B & C), principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the transpose of this matrix to generate a low-dimensional projection of genes based on their cell cycle expression (Fig. 2D). Analogous to the derivation of , gene angle was calculated as the angle between PCs 1 and 2 relative to the origin. As discussed, this parameter roughly relates to genes’ order of expression within the cell cycle and indeed recapitulates the order in which genes are replicated (Fig. 2E & F). We chose to use PCA instead of UMAP to derive because while UMAP produces a “wheel” similar to the cell-level analysis (Extended Data Fig. 2C), we reasoned that as a linear dimensionality reduction PCA would be more likely to give a consistent gene angle/origin distance relationship. However PCA-derived values still broadly capture the ordering when UMAP is performed (Extended Data Fig. 2C).

Predicting expression dynamics based on DNA replication alone

We developed two regression models to infer predicted a gene’s predicted gene angle from its distance from the origin of replication (SI Methods Section “Modeling the gene angle-origin distance relationship”) and then to predict cell cycle expression from this value (SI Methods Section “Modeling the cell angle-gene angle relationship”). These models were combined to yield the pipeline in Extended Data Fig. 2I. Firstly, the gene angle-origin distance model (SI Methods Section “Modeling the gene angle-origin distance relationship”) was used to predict the expected value from origin distance D. Next, cell cycle expression was predicted using the cell angle-gene angle regression model (SI Methods Section “Modeling the cell angle-gene angle relationship”) using values. For cell angle , values used were the average values of cells binned into 100 equally spaced bins by . This gives a replication-predicted gene expression matrix of 100 bins × number of genes. The success of this model fit was evaluated based on the correlation with the -binned expression z-scores derived from scVI (Extended Data Fig. 4A & F), as well as the loss of global chromosome position-dependent gene-gene correlations upon correction of scVI expression with replication-predicted expression (Extended Data Fig. 4B & G). Additionally, we used this modeling approach to set the zero angle for gene expression plots.

Setting the position of

Initially, the cell angle orders cells by their cell cycle position within a circle but the start point, when , is arbitrary. This is not only challenging to interpret but impedes comparing across replicates. Therefore, we standardized so that was the predicted point of replication initiation. Using the inference approach described above, we predicted the gene expression profile by for an imaginary gene at (i.e. at the origin of replication). We then determined the value of giving the minimum predicted expression, reasoning that if increased expression in this model is responsive to a doubling of copy number, the doubling event should occur approximately at the expression minimum. Therefore, we determined this angle, to be the most likely value of at which replication initiation occurs, rotating the angles by the operation () mod 360 to set this point as 0°. This interpretation is roughly in accordance with the estimated timing of replication initiation as determined directly from smFISH data (Extended Data Fig. 5F and SI Methods Section “Inferring cell-cycle phase from the DAPI signal”). Crucially, however, it also provides a point of standardization that allows in-phase comparison of cell cycle expression profiles across independent replicates.

Identifying replication-divergent genes

We identified replication-divergent genes based on two criteria: absolute variability by cell angle and divergence from the replication model. For details, see SI Methods Sections “Identifying genes with high cell cycle variance” and “Identifying genes with high divergence from predicted expression”.

Plotting expected and observed cell cycle expression patterns.

To visualize the degree of divergence from predicted expression, (e.g. Fig. 2H, Fig. 3B), we take scVI-derived z-scores averaged in 100 bins by along with model predictions (Section “Predicting expression dynamics based on DNA replication alone”). We then adjust as described above (Section “Setting the position of = 0”). Importantly, we are able to validate our analysis from the raw (non-scVI-derived) data by averaging normalized counts (Extended Data Fig. 4J). This demonstrates that cell cycle expression patterns are not an artifact of scVI denoising.

Analyzing the effect of operon gene position on expression dynamics

We identified the excess of genes with a “delayed” expression profile by calculating the angle difference as where and are the observed and predicted gene angles in radians, respectively. For operon annotations, E. coli and B. subtilis transcription units from Biocyc 64,65 (https://biocyc.org/) were used. To investigate the relationship between gene distance from transcriptional start sites and angle difference in E. coli, all genes in polycistrons (transcription units with more than one gene) were included. The distance was measured from the annotated transcription unit start site to the midpoint of each gene. Where genes were in multiple transcription units, the longest distance from a start site was taken. Angle difference was converted into time by dividing the angle by 360° then multiplying by the doubling time in seconds. For S. aureus, operon annotation was obtained from AureoWiki66 (aureowiki.med.uni-greifswald.de). Since this provided only the genes within an operon and not its start, the first base of the first gene was taken as the transcriptional start site.

Analysis of operon expression trends relative to timing of operon replication.

For each operon shown (Fig. 3D), the predicted replication timing in degrees of was calculated as the predicted minimum in expression for the first gene in that operon (similar to calculation of TRIPs, Section “Defining gene Transcription-Replication Interaction Profiles (TRIPs)”). The cell angle, , was then redefined such that is the point of operon replication (denoted , and for each operon). With an expected DNA polymerase speed of ~800 bp/s28,29, replication of the whole operon is expected to take <20 s so it is assumed that genes within the operon are replicated simultaneously. Next, -derived normalized expression of the nuo, atp, and mraZ-ftsZ operons, averaged in 100 bins by , was converted to fold change relative to the replication point by dividing cell cycle expression by when , or , respectively, were equal to zero degrees. As shown in Fig. 3D, this reveals that genes far from, but not close to, the TSS display transient decreases in expression.

For analysis of correlations between a gene’s position within its operon and its expression timing or amplitude, Spearman correlations were calculated using the “spearmanr” function in the Python package scipy v1.9.367. This function was also used to calculate P-values based on a two-sided test with the null hypothesis of no correlation.. See documentation in https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.stats.spearmanr.html for details.

Defining gene Transcription-Replication Interaction Profiles (TRIPs)

Our work uncovered evidence that cell cycle-dependent fluctuations in each gene’s expression can arise from the diverse responses of that gene to perturbation by replication. Therefore, we define the TRIP as a gene’s expression profile relative to its predicted timing of replication. We did this for all genes that showed good reproducibility between replicates (Spearman correlation > 0.7 between expression averaged in 100 bins by . To produce each gene’s TRIP, we first take scVI-normalized expression and average in 100 positions by . To preserve information on the dynamics of each gene (since amplitude in cell cycle fluctuations is an important parameter in interpreting TRIPs), we do not log-transform or scale expression but instead divide by the mean expression across the cell cycle (to allow comparison of genes with different baseline expression levels). For each gene, we then determine the predicted timing of replication as the minimum in the predicted expression (Section “Predicting expression dynamics based on DNA replication alone”). We then rotate for that gene so that = 0 corresponds to this predicted replication timing. We denote this as , calculated by the transformation () mod 360 where is the predicted expression minimum. Therefore, the TRIP preserves replication dynamics while allowing standardization across different replication timings and baseline expression values.

Clustering of TRIPs.

Reproducible genes were clustered based on the TRIPs derived as above using k-means clustering. TRIPs for genes within each cluster were then averaged to give the cluster profiles in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 9. To analyze for enrichment of repressed genes in E. coli, repressor annotations were obtained from Biocyc64,65 (https://biocyc.org/). We then assessed whether genes within each cluster were enriched for genes that had an annotated repressor, using the hypergeometric test to assess significance. Since we noticed that a handful of regulators had a much higher number of target genes than others (Extended Data Fig. 9B, Right), we decided to exclude these “global repressors” (20 or more repressive targets annotated), which decreased the background fraction of reproducible genes with an annotated repressor from 35% to 18%, thus improving the sensitivity and focusing the analysis on more specific repressor-target interactions. After performing the analysis on each cluster, we then adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, choosing a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.1. Note that while most of the clusters showing enrichment were those early peaking clusters with or without high amplitude, clusters Ec5 and Ec12 were also significant. Ec5 is dominated by nuo genes and dnaA, and Ec12 is the nrdAB-yfaE operon, all of which have annotated repressors.

Simulating the effect of DNA replication on gene expression

We predicted the gene-gene correlation patterns arising from DNA replication using a simulation written in Python (see Extended Data Fig. 1H–K) as follows. Cells were represented by genomes with 200 genes, each represented as a single integer and divided into individual replication units. In the simplest case, genomes were divided into two units of 100 genes (i.e. the two “arms” of the chromosome). In each cell, replication initiation events were simulated at intervals determined by a Poisson distribution with expected value μ. After an initiation event, replication proceeds in stepwise fashion along the length of each replication unit, doubling the copy number at each point until the end of that replication unit has been reached. We also simulate “cell division” events in which all copy numbers are halved. These are timed independently from replication initiation but in the same way (at Poisson-distributed intervals with rate μ), with an additional offset from the first replication initiation event. In practice, we found that this offset did not affect correlations, since all genes are scaled equally. We used an initial offset of 150 steps (i.e. 1.5x the time to replicate a 100 gene replication unit, equivalent to the 40 min C-period + 20 min D-period originally proposed for E. coli B/r6). For each simulation, we generated 1,000 cells. Cells were initiated one at a time to yield an unsynchronized population, then the simulation was run for a further 1,000 steps with the whole population. We then normalized expression by total counts and calculated Spearman correlations across all genes. In order to simulate specific doubling times, the rate was calculated as where is the number of genes in the longest replication unit (here, 100 genes), is the doubling time, and is the C-period (here a value of 42 min was chosen for E. coli MG1655 based on 24). The ratio represents the fraction of one round of chromosomal replication that can take place in one cell cycle. Finally, for simulation of cells with additional origins of replication, genes were split into replication units according to the following assumptions: a) all origins initiate replication simultaneously; b) replication stops at the termination site ter, which is halfway along the chromosome; c) genes are replicated by the nearest origin (unless the replication fork must pass through ter to reach that gene).

Bulk RNA-seq analysis

For the analysis of bulk RNA-seq from 13 (Extended Data Fig. 1L), we accessed data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession ID GSE46915. Counts were size factor-normalized with DESeq2 v1.32.0 68, then data were standardized to z-scores and averaged into 100 kb bins by chromosomal position. Spearman correlations of binned values across all time points and replicates are shown.

Single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH)

For a full description of smFISH experimental procedures and analysis, see SI Methods Section “smFISH experiments and analysis”.

Biophysical modeling of TRIPs

For biophysical modeling of scRNA-seq data, expression profiles were first converted into inferred copy number as a function of time and then specific models were fitted. See SI Methods Sections “Transformation of scRNA-seq data for biophysical modeling” and “Biophysical modeling” for detailed descriptions.

Generation of chromosome-integrated reporter constructs in S. aureus

For generation of the reporter construct, we modified the pJC1111 vector69, which integrates at the SaPI1 chromosomal attachment (attC) site. The vector was linearized with restriction enzymes SphI and XbaI (New England Biolabs) and insertion fragments were amplified using Q5 polymerase (New England Biolabs). For the GbaA-L promoter, the intergenic region of the GbaA regulon (130 bp upstream of the SAUSA300_RS13955 start codon) amplified from USA300 LAC genomic DNA using primers 5’-CCGTATTACCGCCTTTGAGTGAGCTGGCGGCCGCTGCATGGATTACACCTACTTAAAATTCTCTAAAATTGACAAACGG-3’ and 5’-AGTTCTTCTCCTTTGCTCATTATCAACACTCTTTTCTTTTATGATATTTAATAGTTATTGCAAATTCA-3’. S. aureus codon-optimized sGFP was amplified from the genomic DNA of S. aureus USA300 LAC previously transformed with the pOS1 plasmid (VJT67.6370) using primers 5’-AAAAGAAAAGAGTGTTGATAATGAGCAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTCACTG-3’ and 5’-ATAGGCGCGCCTGAATTCGAGCTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCTTTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGG-3’. Fragments were assembled using the NEBuilder HiFi assembly kit (New England Biolabs) and transformed into competent E. coli DH5ɑ (New England Biolabs). The plasmid was purified and then electroporated into RN9011 (RN4220 with pRN7023, a CmR shuttle vector containing SaPI1 integrase), and positive chromosomal integrants were selected with 0.1 mM CdCl2. Finally, this strain was lysed using bacteriophage 80ɑ and the lysate was used to transduce JE2 and JE2 gbaA− strains, selecting for transduction on 0.3 mM CdCl2.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1: Growth and single cell analysis of E. coli and S. aureus.

A) mRNAs captured per cell by PETRI-seq. mRNA captured is quantified as unique molecular identifiers (UMI) per unique cell barcode combination in S. aureus in TSB (left, Dataset D3) and E. coli in different media (right, Dataset D1). B) Growth curves of bacterial strains. Left: E. coli in three medium conditions, LB (n = 4), M9GA (n = 4), and M9G (n = 3). Doubling times were calculated based on the linear portions of growth (marked as fitted lines). Center: Growth of S. aureus under standard growth conditions, with the time and log2(A600) values when exponential and stationary phase samples were taken (Datasets D3 & D4) marked with dotted lines. The line is fitted to the mean at each time point, with the gray area representing standard deviation (n = 5). Right: Growth of S. aureus under balanced growth conditions (n = 3). The black line indicates the linear portion from which doubling time was estimated. C) Spearman correlations from Fig. 1C without binning by chromosome position. D) Correlations from Fig. 1C without the use of scVI, binning in 200 kb bins by chromosome position. E) Spearman correlations in exponential S. aureus data from Dataset D4, averaged in 50 kb bins, as for Dataset D3 in Fig. 1C. F) Initial correlations from unbinned, scVI-denoised gene expression data. Sample “S. aureus exponential 2” is from Dataset D4, whereas E. coli LB replicates 1 and 2 are from Dataset D1 and Dataset D2, respectively. G) Gene-gene correlations in 50 kb bins as depicted in Fig. 1C but for stationary phase S. aureus (Dataset D4). H) Schematic figure of the simulation. Each “arm” of the circular chromosome is represented as an array of integers (initially ones), representing each gene. Replication proceeds stepwise from origin to terminus, doubling copy number as it does (steps 1 to 2). At high replication rates, a second round of replication will initiate before the first has finished (step 3). When one round of replication reaches the terminus, that round finishes and after a given time interval copy numbers are globally halved, reflecting cell division (steps 4 to 5). Figures on the right indicate the represented states on the circular chromosome. See Methods for details. I) Simulation of DNA copy number effects predicts the global gene covariance pattern. For 1,000 simulated, unsynchronized cells where the doubling time is equal to the C-period, the normalized, scaled gene expression matrix (left) is used to calculate gene-gene correlations (right). J) Quantitative comparison between simulated and observed datasets. For each simulated and observed dataset, expression was first averaged in 40 bins by chromosome position. After calculating the correlation matrix of this binned data, the lower triangle was taken (excluding self-self correlations along the central diagonal) and flattened into a one-dimensional vector. These vectors were then used to calculate Spearman correlations. For all E. coli samples, the strongest correlations are between matched simulated and observed pairs. K) Simulated gene copy abundance data with cells ordered by increasing total gene dosage in S. aureus (left, from simulation in (I)) and E. coli (right, from simulation in Fig. 1E Left panel). Fork positions are indicated by black dots. Note that because our simulation results in subsets of cells that diverge from the normal chromosomal copy number range (because of the lack of checkpoints between replication and division that would be present in real bacterial cells), the raw sum of total gene copies is first divided by the copy number of genes at the terminus to provide the total gene dosage used here. L) Gene expression correlations in synchronized C. crescentus bulk RNA-seq from. Scaled gene expression is averaged into 100 kb bins. M) The relationship between origin distance and expression levels. For each E. coli growth condition, the average fraction of total mRNA UMI from each gene was calculated and log2-transformed. A linear regression model (black line) was fitted between log-fraction counts and origin distance. Spearman correlations are −0.13 (LB, P = 3.8 × 10−10), −0.09 (M9GA, P = 2.2 × 10−5), and −0.07 (M9G, P = 6.0 × 10−4). P-values indicate the statistical significance of the Spearman correlation based on a two-sided test using the “spearmanr” function in the Python package scipy v1.9.3. See Methods for details. N) The gradient of the linear model fits in (M). Note that in each case, there is a negative relationship, with a steeper gradient for faster growth rates. This is expected given that at fast growth rates, genes near the origin may attain higher copy number states (>2) than at slow growth rates. O) Histogram showing that length-adjusted average gene expression varies over several orders of magnitude in exponentially growing S. aureus. This is a broad distribution that would not be expected from genomic DNA. Raw expression counts were normalized by library size (to sum to 1 per barcode) and the average expression was calculated. Length correction was performed as expression divided by gene length then multiplied by median gene length. P) Spearman correlations between genes in the top and bottom 20% of genes ranked by expression level (Left: S. aureus; Right: E. coli). Genes are arranged by chromosomal order. Shown for both unbinned expression (Top) and expression grouped in 50 kb bins as in Fig. 1C (bottom). If the pattern was driven by low-level contaminating genomic DNA, it would be expected to be more evident in low-expressed genes (since a higher proportion of reads from these genes should come from genomic DNA) than in high-expressed genes. The opposite is true, with a much stronger pattern in high-expressed genes (presumably due to less noise in these measurements). Taken together, these observations strongly support that the pattern is driven by variation in the transcriptome rather than contaminating genomic DNA.

Extended Data Fig. 2: Cell and gene angle analysis to model replication-dependent gene expression.

A) UMAP analysis of LB-grown E. coli based on scVI-predicted expression. B) UMAP of S. aureus with gene expression averaged in 50 kb bins by chromosome position. Cells are colored by the cell angle between UMAP dimensions relative to the center of the projection. C) UMAP of E. coli genes, performed on the same data as the PCA in Fig. 2D. Gene angles shown are those derived from PCA. D) The relationship between and origin distance for E. coli grown in M9 + glucose + amino acids (M9GA) or M9 + glucose (M9G). The black line indicates the model fit as described in SI Methods Section “Modeling the gene angle-origin distance relationship”. E) Predicted replication patterns as for Fig. 2G but for E. coli under slower growth conditions. F) Gradients of the gene angle-origin distance relationship and estimates of DNA polymerase speed from these gradients. See Methods for details. G) Expression in LB-grown E. coli is first averaged in 100 bins by then averaged in 100 bins by to yield the 100 × 100 matrix represented here as a heatmap. This is used to train the model to predict gene expression at a given point in the cell cycle () for a given gene (). H) Conceptual representation of the cell cycle expression parameterization. Cells are ordered in their cell cycle state by , whereas genes are ordered by their cell cycle expression by . Cell cycle expression can be described as the concurrent cycling of cells and genes ordered by these metrics. I) Predicting gene expression dynamics based on distance from the origin. The following pipeline predicts cell cycle expression for a given gene based only on its distance from the origin of replication. A regression model predicts gene angle based on origin distance alone (left) and this is converted into a prediction of expression by cell angle using a second regression model (middle). Ordering genes by chromosome position (right) shows a smoothed version of the expression pattern in Fig. 2B. The bar at the top of this figure shows the real and predicted gene angles. Data are from E. coli grown in LB. See Methods for full details.

Extended Data Fig. 3: Transcriptional and replication dynamics during environmental shifts.

A-D) Nutritional shift-up in E. coli from M9GA (here, measured as 36.0 min) to a 1:1 mix of M9GA and 2x LB (LB/M9GA, measured as 24.2 min). Samples LB 15 min and LB 30 min are 15 min and 30 min, respectively, after cells grown in M9GA are mixed 1:1 with 2x LB. Samples M9GA and LB/M9GA are in balanced growth conditions. See Methods for details. A) Growth curve. After 120 min, cells were diluted 1:1 into either the same growth medium (for M9GA and LB/M9GA conditions) or M9GA into 2x LB (M9GA -> LB). A600 measurements are corrected for this 2x dilution. Arrows represent the times at which PETRI-seq samples were taken, colored according to the condition of these samples. Lines represent linear model fits to data from 30–180 min (M9GA & LB/M9GA conditions) or from 135–280 min (M9GA -> LB condition). Data are from three biological replicates. B) Shifts in the transcriptome upon nutritional shift-up. Left: PCA of all cells, colored by sample. The top is a plot of density along the PC-1 axis, the bottom is a scatter plot of PCs 1 and 2. Prior to PCA, scVI denoising was performed jointly on all samples. Annotated arrows at the top summarize enriched KEGG pathways based on gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). GSEA was performed on the PC-1 loadings, where the direction of the arrows indicates the sign of the GSEA normalized enrichment score. PC-1 represents the transition from M9GA to LB/M9GA since PC-1 loadings strongly correlated with the fold change in gene expression between these samples (Spearman’s r = 0.88). Right: Direct sample-sample Spearman correlations between bulk-averaged per-sample gene expression (measured as total UMI-normalized counts). Note that M9GA has a relatively low correlation to other samples, suggesting that the shift in the transcriptome has already occurred 15 min after the shift-up. C) Chromosome-wide expression correlations measured between 50 kb regions as in Fig. 1C. Note that the noisy pattern for the M9GA sample is caused by the low UMI/cell acquired for this sample (42 UMI/cell). D) Replication pattern statistics. Left: Estimated overlap in rounds of replication for each sample. Right: Inferred doubling time, . By assuming that the C-period is unchanged from the M9GA sample (here, 52 min), we can convert replication patterns into inferred estimates of doubling time based on replication alone. See Methods. E-H) Inhibition of S. aureus growth by vancomycin. S. aureus cells in balanced growth in TSB were exposed to vancomycin and measured over time. E) Growth curve after addition of vancomycin. Arrows represent the times at which PETRI-seq samples were taken, colored according to the condition of these samples. Lines represent sample averages of three biological replicates at each timepoint. F) Shifts in the S. aureus transcriptome after vancomycin treatment. See (B) for details. G) Chromosome-wide expression correlations measured between 50 kb regions as in Fig. 1C. H) Replication pattern statistics. See (D) for details.

Extended Data Fig. 4: Correcting for and measuring divergence from predicted replication-associated patterns.