Summary

Expansions of CAG trinucleotide repeats cause several rare neurodegenerative diseases. The disease-causing repeats are translated in multiple reading frames, without an identifiable initiation codon. The molecular mechanism of this repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation is not known. We find that expanded CAG repeats create new splice acceptor sites. Splicing of proximal donors to the repeats produces unexpected repeat-containing transcripts. Upon splicing, depending on the sequences surrounding the donor, CAG repeats may become embedded in AUG-initiated open reading frames. Canonical AUG-initiated translation of these aberrant RNAs may account for proteins that have been attributed to RAN translation. Disruption of the relevant splice donors or the in-frame AUG initiation codons is sufficient to abrogate RAN translation. Our findings provide a molecular explanation for the abnormal translation products observed in CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion disorders and add to the repertoire of mechanisms by which repeat expansion mutations disrupt cellular functions.

Graphical Abstract

Blurb

Anderson et al., show that expanded CAG trinucleotide repeats produce 3’ splice sites. Proximal donors splice into the repeats in a repeat-length dependent manner generating unexpected repeat-containing mRNAs. This splicing may place repeats in AUG-initiated frames, potentially explaining aberrant, out-of-frame protein products.

Introduction

Expansions of CAG trinucleotide repeats are associated with at least twelve degenerative disorders, including Huntington’s disease (HD), dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA), spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), and several spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs)1,2. In each of these diseases, the associated gene is polymorphic for the number of CAG repeats, and disease manifests when the repeat number exceeds a certain threshold1. In most CAG repeat expansion disorders (including HD; SCA types 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 17; DRPLA; and SBMA), the CAG repeat tract is located in the protein coding region, and codes for a polyglutamine stretch1. An expanded polyglutamine tract renders proteins aggregation prone, and this repeat-dependent protein aggregation contributes to disease pathology1.

Besides encoding for polyglutamine-containing proteins, CAG repeat expansions can produce cellular dysfunction via at least two additional routes, even when they occur outside of the canonical protein coding regions. First, repeat-containing RNAs can agglomerate in the nucleus as pathogenic foci3,4. RNA foci result from multivalent intermolecular base-pairing interactions templated by the GC-rich repeat tract5. These foci sequester various RNA binding proteins, and cause widespread RNA processing defects6. Second, repeat-containing RNAs undergo translation without requiring an identifiable AUG start codon, in a process known as repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation7-10. RAN translation produces repeat-containing proteins in multiple reading frames, which may form protein aggregates, and are potentially lethal to the cell11. The molecular mechanism of RAN translation is not entirely clear.

In our earlier work, we showed that RNAs that consist primarily of expanded CAG trinucleotide repeats, which are not present in a canonical open reading frame (ORF), accumulate at nuclear foci. These repeat-containing RNAs did not undergo RAN translation even when the repeat number was increased to >400 tandem CAGs5,12. RAN translation is reported to be influenced by the sequences adjacent to the repeat tract10,13. To assess the role of flanking sequences, we previously generated a library of CAG repeat-containing plasmids where various 250 nucleotide long sequences were cloned upstream of 240×CAG repeats12. We found that a subset of these flanking sequences led to RAN translation of the CAG repeat, while others were still retained at nuclear foci12. We were not able to identify sequence motifs in the upstream flanking sequences that differentiated the two classes.

Here, we set out to identify the features of the flanking sequences that determine whether a given CAG repeat-containing RNA will be sequestered at nuclear foci or would undergo RAN translation. We hypothesized that an expanded CAG repeat itself could provide new splicing acceptor site(s), and produce aberrant repeat-containing transcripts. Our hypothesis was guided by three observations. One, live-cell RNA imaging experiments showed that RNAs that undergo RAN translation are first retained at nuclear foci for a prolonged period where they colocalize with the splicing machinery12. Two, mammalian 3’ splice sites have a nearly invariant 'AG' dinucleotide that marks the splice junction (minimal splice acceptor represented as Y6-12NAGNNN, where Y6-12 indicates the upstream pyrimidine rich tract, N is any nucleotide, and the bold bases mark the exon)14. In fact, at least 141,000 (~64%) annotated human splicing acceptor sites harbor a CAG trinucleotide at the splice junction, and >1400 of these sites exhibit two or more (up to nineteen) consecutive CAG trinucleotides (Supp. Fig. 1 A). Three, CAG repeat expansions induce transcriptome-wide splicing changes6,15, and in some cases, are reported to induce mis-splicing of the gene harboring the expanded repeat16-18.

GC-rich repeat-containing sequences are difficult to analyze using standard RNA sequencing approaches, and thus, aberrantly spliced repeat-containing transcripts may have been missed in previous analyses. Thus, we developed an analysis pipeline that specifically captures splicing events at tandem CAG repeats. We find that cognate and near-cognate splicing donors in the surrounding sequences can splice into an expanded CAG repeat tract. This splicing is dependent on the number of CAG repeats, and can place the repeats in unexpected sequence contexts. Interestingly, disease models where expanded CAG repeats are observed to undergo RAN translation, produce RNAs that harbor CAG repeats in AUG-initiated ORFs. Disruption of the relevant splicing donor site or the AUG initiation codon is sufficient to abrogate the production of proteins that are attributed to RAN translation. Our findings provide a cogent mechanistic explanation for how expanded CAG repeats produce abnormal protein products and suggest yet another pathomechanism by which repeat expansions can interfere with RNA processing and cellular functions.

Results

Sequence analysis pipeline for detecting splicing to CAG repeats.

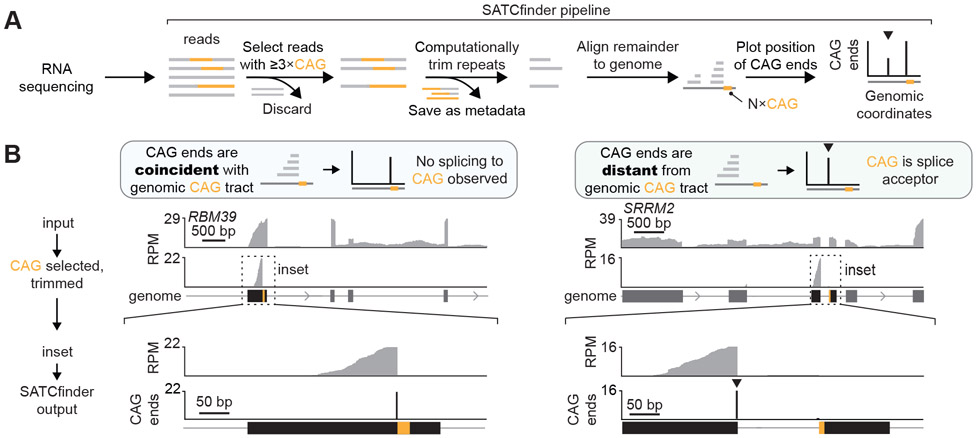

Analysis of repeat-containing RNAs using short-read sequencing technologies is challenging. GC-rich repeats are difficult to reverse transcribe and amplify, and these sequences are substantially under-represented in standard RNA sequencing libraries19,20. The commonly used sequence alignment pipelines also exclude these regions, as repeat-containing reads may map to multiple locations in the genome, or because the reference genome lacks an expanded repeat tract21. To address the first issue, we optimized the library preparation protocol, notably by using a group II intron reverse transcriptase that can reverse transcribe structured22 and GC-rich23,24 RNAs with high fidelity (see STAR Methods). To address the issue of aligning repetitive reads, we developed a pipeline, SATCfinder, to identify and visualize splicing at tandem CAG repeats in RNA sequencing data (Fig. 1A). In brief, SATCfinder’s input is paired end RNA sequencing data. All reads that contain ≥3×CAG/CTG repeats (to capture both sense and antisense transcripts) and at least 15 additional bases that are not a part of the CAG repeat (to allow appropriate alignment and junction identification) are selected. The CAG repeats are computationally trimmed and the remaining non-repetitive portion of the reads, together with the paired read mates, are aligned to the reference genome (see STAR Methods). The mapping coordinate of the CAG end of the trimmed reads (hereafter, CAG end) is tracked. The number of CAG ends coinciding with the genomic coordinate of the CAG repeat versus those aligning farther away to upstream splicing donors allows us to quantitatively assess the extent of splicing to the repeat tract (Fig. 1 A). For example, when CAG repeats are not a part of the splicing acceptor (i.e., they are contained entirely in an exon or an intron), the position of the CAG repeats in mRNA matches the location of the repeat tract in the genome. For a representative gene in this class, RBM39, the CAG ends in RNA identified using SATCfinder coincide with the end of the CAG repeats in the genome (in 99.5% of reads, Fig. 1B left, Supp. Fig. 1B). Likewise, we examined several other genes where CAG repeats are annotated to be in the middle of an exon, and in each case, >99% of CAG ends mapped immediately adjacent to the CAG repeat tract in the genome (Supp. Fig. 1B, D).

Figure 1. Sequence analysis pipeline for detecting splicing to CAG repeats.

A. Schematic for SATCfinder. Reads with >3xCAG/CTG repeats are selected. The CAG repeats are computationally removed and these trimmed reads are aligned to the genome. The genomic coordinates of the base immediately before the repeat (CAG end) in the trimmed and mapped reads is tracked. SATCfinder outputs the number of CAG ends per million mapped reads at a given genomic coordinate. The peak at the repeat reflects reads where CAG repeats are not a part of the splice junction, while a distal upstream peak (at the nearest upstream exon, typically within a few kb) indicates the location of the splicing donor (marked by an arrowhead ▼). B. Representative genes comparing standard RNA sequencing analysis to SATCfinder output.

Sixty-eight human genes are annotated to have ≥3×CAG at splice acceptor sites (Supp. Fig. 1A, Supplemental Table 1). For this class, the non-repetitive sections of CAG-containing reads map to a location upstream of the CAG repeat in the genome (see representative example SRRM2, Fig. 1B, right). A vast majority (~95%) of upstream CAG ends align to the annotated splicing donor site upstream from the tandem CAG acceptor site (Fig. 1B, right, Supp. Fig. 1C, E-F). The remainder (~5%) of CAG ends coincide with the repeat tract in the genome, likely arising from unspliced pre-mRNAs (Fig. 1B, right, Supp. Fig. 1C). Treatment with a splicing inhibitor increased the proportion of reads corresponding to the unspliced CAG repeat-containing RNAs by ~10-fold (from 3% to 33% of CAG ends on treatment with 25 nM pladienolide B, Supp. Fig. 1G). Similar results are observed for other genes in this class (Supp. Fig. 1C-D). Altogether, these results demonstrate that our library preparation protocol coupled with SATCfinder allow us to examine events where CAG repeats form splicing acceptor sites.

CAG repeat expansions result in mis-splicing of repeat-containing RNAs.

We used SATCfinder to examine whether CAG repeat expansions could induce mis-splicing of repeat-containing RNAs. We previously generated a small library of sequences where 240×CAG repeats were cloned downstream of various 250 nucleotide flanking sequences12 (Fig. 2A). In these constructs, multiple stop codons were incorporated immediately upstream of the CAG repeats to eliminate translation readthrough from any upstream ORFs into the repeats. In about half of these constructs, the CAG repeat-containing RNA was retained in the nucleus at foci, while in other cases, the repeat-containing RNA was exported to the cytoplasm, underwent RAN translation, and formed perinuclear aggregates (Fig. 2A). Cytoplasmic localization also coincided with substantial cellular toxicity12.

Figure 2. CAG repeat expansions result in mis-splicing of repeat-containing RNAs.

A. Schematic for constructs with 240xCAG repeats with a variable 250-base flanking sequence12. Some flanking sequences result in retention of the repeat-containing RNA in the nucleus while others induce RAN translation and cell toxicity. B, C, D. Top, SATCfinder output for representative CAG constructs, where the x-axis is the base coordinate within the flanking sequence region and the y-axis indicates the number of CAG ends per million mapped reads. Bottom, Representative fluorescent images of cells expressing the indicated constructs. Micrographs are representative of > 2 independent experiments. Scale bar depicts 10 pm. E. Left, sequence logos for 5’ splice sites annotated in the human genome and those observed in the CAG flanking sequence library, where the x-axis indicates the position within the 9-base donor sequence and the letter height depicts the probability of observing the base. Right, 5’ MaxEnt scores for 220419 annotated human splice donors, all 262144 possible randomly generated 9-mers, and the 20 detected splice donors in the CAG flanking sequence library. F. Quantification of the percentage of cells with cytoplasmic RNA aggregates by fluorescence microscopy. Each data point represents an independent experiment with > 500 cells per experiment, and are summarized as mean ± SD. G. Real-time quantitative PCR quantification of the relative expression of CAGran intron normalized to the expression of the 5’ end of the CAGran transcript. Splicing inhibitor reflects treatment with 25 nM pladienolide B. Data show the mean ± SD for three independent RNA isolations. H. Schematic for CAGran, depicting the transcription initiation site (as a right-facing arrow), flanking sequence, and 240xCAG repeats intervened by stop codons in each frame. The sequence of a representative donor that splices to the CAG tract is shown, with bases in the exon in uppercase. After splicing, the stop codons are removed and the CAG repeat is embedded in an AUG-initiated ORF. I. Immunoblot for cells expressing CAGfoci and CAGran using a polyglutamine antibody. J. Percentage of repeat-containing transcripts where the repeats are observed in AUG-initiated ORFs for constructs that produce RNA foci only or exhibit RAN translation. Each data point is one construct. K. Immunoblot for the indicated samples using a polyglutamine antibody. CAGRAX*donors has point mutations at all splice donor sites; CAGran*ai g has point mutations at two AUGs. Immunoblots are normalized first to tubulin, then to the parent cell line without a repeat-containing construct (mock). Immunoblots and quantification of relative polyglutamine abundance (as mean ± SD) are representative of > 2 independent experiments. *An endogenous protein (TBP) is also detected by this polyglutamine antibody10,65. Significance values in F, G, and J are calculated using Student’s t-test. MS2CP-YFP: bacteriophage MS2 coat protein tagged with YFP.

We performed RNA sequencing on cells expressing the various 240×CAG repeat-containing RNAs that either form nuclear foci (6 cell lines, with CAGFOCI as a representative of this class, full sequences are provided in Supplemental Table 4) or undergo RAN translation (7 cell lines, with CAGRAN as a representative of this class). Our analysis using SATCfinder revealed that the CAG repeats in RNA were frequently stitched to regions in the upstream flanking sequences, and the intervening region had been removed (see representative examples for CAGFOCI and CAGRAN in Fig. 2B-C, top; and other examples in Supp. Fig. 2A-B).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the junctions identified by SATCfinder arise from splicing to CAG repeats. One, quantitative and end-point PCR on the genomic DNA and RNA confirmed that the desired sequences were integrated into the genome but the intervening sequences were removed from the RNA (Supp. Fig. 2C-E). Two, the readjunctions identified by SATCfinder harbor signatures of splicing donors (Fig. 2E, left,, sequences in Supplemental Table 2). We evaluated these identified donor sites using a computational splice-site prediction algorithm, MaxEntScan25. This algorithm reports a log-odds ratio of observing a motif in true versus decoy splice sites, where a higher MaxEnt score indicates a stronger putative splice site26. Known human splice donors score in the range 0 to 12 (>95% score above 2; median 8.6, Fig. 2E, right). The donors that were identified by SATCfinder to splice to CAG repeats in our library had positive 5’ MaxEnt scores (1.59 – 9.40, median 4.95; Fig. 2E, Supplemental Table 2), indicating that these sequences are canonical splice donors. Three, chemical inhibition of splicing using pladienolide B27 led to a dose-dependent reduction in the frequency of splicing from the upstream flanking region to the CAG repeats (Supp. Fig. 2F, G). Finally, point mutations to the crucial GGU motifs of the donors (GGU→GGA) were sufficient to eliminate splicing to the repeats (Fig. 2D, Supp. Fig. 2H).

Splicing was dependent on the number of CAG repeats, and its frequency progressively increased with the repeat number (Fig. 2G, Supp. Fig. 3 A-G). Similar splicing patterns were observed across various cell lines (Supp. Fig. 21). A variety of donor sequences could be spliced to the CAG repeats, and the consensus sequence of the donors identified in our flanking sequence library closely resembles the consensus sequence for the annotated donor sites in the human genome (Fig. 2E, Supp. Fig. 2J-K). In summary, these results show that splicing from putative donors, occurring by chance in our library of flanking sequences, resulted in unexpected CAG repeat-containing RNAs that differ from the intended sequences that were integrated in the genome.

Even though we engineered stop codons in each frame immediately upstream of the CAG repeats, a subset of these constructs produced polyglutamine-containing proteins (Fig. 2H-I). Splicing to CAG repeats could create mature transcripts where the proximal stop codons are spliced out and the repeats are placed within AUG-initiated ORFs. To test this idea, we assembled the full-length mature mRNAs produced from these constructs using our RNA sequencing data. In all cases where we observed translation of the repeat region, we found AUG-initiated ORFs, generated after splicing, that contain the repeat region (Fig. 2J, Supp. Fig. 4A). On the other hand, sequences that formed nuclear foci either did not exhibit substantial splicing to CAG repeats or, upon splicing, did not produce AUG-initiated ORFs that contain the CAG repeats (Fig. 2J, Supp. Fig. 4A). Across the various cell lines, the abundance of RNAs with repeat-containing AUG-initiated ORFs correlated with the levels of polyglutamine protein produced (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = 0.83, between polyglutamine immunofluorescence and RPM of transcripts carrying an AUG-initiated ORF, Supp. Fig. 4B-C).

We chose one representative sequence, CAGRAN, to further examine the role of splicing in the translation of the repeat region. We isolated the polysome fraction from cells expressing CAGRAN and found that a vast majority of CAGRAN transcripts on actively translating ribosomes were spliced (Supp. Fig. 4D-F). Mutation of the identified splice donor sites in CAGRAN, which eliminated splicing to the repeat tract, also abrogated the production of aberrant polyglutamine proteins (Fig. 2K). The mature repeat-containing transcripts produced from CAGRAN contained an ORF with two in-frame AUG codons (Fig. 2H). Disruption of these AUG codons by single-base mutations at each site similarly eliminated the polyglutamine product (Fig. 2K). N-terminal sequencing of the polyglutamine protein produced in CAGRAN confirmed that it is methionine-initiated, and the first six amino acids in this protein (MRFLAT) are as expected for translation initiation from the first AUG in the ORF (Supp. Fig. 4G). Interestingly, pharmacological inhibition of splicing led to the retention of the repeat-containing RNA in the nucleus at foci (Supp. Fig. 4H-I). Likewise, point mutations to the splice donors in CAGRAN were sufficient to convert this sequence to the foci-forming class (Fig. 2D, bottom, and Fig. 2F). Unlike CAGRAN, expression of this sequence with mutated donors (CAGRAN*donors) did not induce cell toxicity (Supp. Fig. 4J), consistent with our earlier report that expression of repeat-containing RNAs that only produce nuclear foci, do not induce overt cell death12. Thus, the aberrant translation products in CAGRAN result from canonical AUG-initiated translation of aberrant transcripts that arise from splicing to expanded CAG repeats, and disruption of splicing or the appropriate AUG start codons is sufficient to eliminate the translation of the repeat tract.

CAG repeats with native disease-associated flanking sequences form splice acceptors.

Besides an acceptor site, splicing requires cis-acting elements, such as a polypyrimidine tract, that facilitate spliceosome assembly. The splicing potential of a putative acceptor site can be evaluated by the 3’ MaxEnt model that takes into account these cis-acting sequences. Most annotated splice sites in the human genome score in the range 0 to 16, with a median score of 8.6 (Supp. Fig. 5A). In our library of flanking sequences, CAG repeats were placed in a synthetic sequence context which likely provided the polypyrimidine tract (3’ MaxEnt score = 2.45; sequence in Supplemental Table 4). We examined whether disease-associated CAG repeats in their native upstream sequence context may also act as splicing acceptors. These loci, in general, have lower 3’ MaxEnt scores than typical human acceptor sites (range −13.3 – 5.9, median = 1.6) (Supp Fig. 5B).

We experimentally examined the prevalence of splicing in cases where expanded CAG repeats are reported to produce aberrant RAN translation products. The first report on RAN translation of CAG repeats utilized a minigene with 107×CAG repeats flanked by sequences native to the ATXN8 gene10, associated with SCA8 (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, Zu et al. also observed splicing from an upstream splice donor to the CAG repeats, but the resulting spliced transcript did not contain ORFs that explained the observed aberrant translation products (Fig. 3A). To investigate whether there were additional donor sites, we transfected HEK293T cells with this ATXN8 minigene, similar to the previous study, and analyzed the resulting RNA using SATCfinder. Our analysis revealed that only about half of the CAG-containing reads were unspliced and mapped to the expected minigene sequence (Fig. 3B). The remaining CAG-containing reads mapped to distant sites on the plasmid, suggesting that additional mature CAG-repeat-containing RNAs are produced in these cells (Fig. 3B). Using a conservative threshold of ≥100 unique reads supporting a putative splice donor, we identified six donor sites (Fig. 3B, Supp. Fig. 5C-D). The donors contain the nearly invariant ‘GGU’ motif found in human splice donors, and have positive 5’ MaxEnt scores (2.7 – 9.82, Fig. 3D). Splicing inhibition using pladienolide B or isoginkgetin28 significantly decreased the number of reads that reflect splicing to the repeat tract (84% and 98% reduction in splicing for 25 nM pladienolide B and 15 μM isoginkgetin treatments, respectively, Fig. 3B). Point mutations to the donor sites completely abolished splicing from the respective donors (Fig. 3C), further validating that these donors are spliced to the CAG repeat tract. Similar results were observed for other CAG-containing mini-genes where the proximal sequences are derived from the genes HTT, JPH3-AS, ATXN3, and DMPK-AS, associated with the diseases HD, Huntington disease-like 2, SCA3, and myotonic dystrophy type 1 respectively (Supp. Fig. 5E).

Figure 3. CAG-repeats with native disease-associated flanking sequences form splice acceptors.

A. Schematic for the ATXN8 mini-gene expressing -100 bp of endogenous A TXN8 sequence directly upstream from 107><CAG repeats10. The ampicillin resistance gene (AS-AmpR) and colEl origin of replication are indicated. B. Left, SATCfinder output for cells transfected with the ATXN8 construct in the presence of splicing inhibitors 25 nM pladienolide B (PB), or 15 μM isoginkgetin (IGG), or 0.1% DMSO (DMSO) as control. Right, quantification of the % of CAG ends that reflect splicing to the repeat. C. Similar to B but for ATXN8 constructs without or with point mutations to identified donor sites. D. Sequences of the identified splicing donors in the ATXN8 construct with corresponding percentage of reads arising from each donor. The sequence logo for the consensus human splice donor is presented for comparison. E. Schematic for the various CAG repeat-containing transcripts produced upon splicing from the ATXN8 construct.

We examined the origin of the splicing donor sequences in these mini-genes, and to our surprise, we found that a significant fraction of the spliced reads arose from a donor located in the ampicillin resistance cassette more than 1 kilobase upstream from the CAG repeats (Fig. 3B). The AmpR gene is encoded in the antisense direction (AS-AmpR) with respect to the CAG repeats. The bacterial AmpR promoter should not initiate transcription in mammalian cells nor would it produce CAG repeat-containing transcripts (see full sequence map in Supp. Fig. 5F). To determine how a donor in the AS-AmpR sequence could splice to the CAG repeats, we examined the raw (non-CAG-selected) read alignments. We noted a region of high coverage beginning within the colE1 E. coli origin of replication and continuing through the AS-AmpR region (Supp. Fig. 5G). This coverage did not result from readthrough of the polyadenylation signal from the adjoining neomycin resistance gene (Supp. Fig. 5G). Transcript assembly using StringTie29 confirmed that the AS-AmpR transcript originated within the colEl region (Supp. Fig. 5H). Reads corresponding to this region were also observed in other plasmids that harbor colEl origin of replication (Supp. Fig. 51), and the transcripts initiating from colEl were ~30% as abundant as those from the SV40 and CMV promoters (Supp. Fig. 5J). This observation is consistent with reports that the colEl origin of replication acts as a cryptic promoter in eukaryotic cells and may result in spurious unintended transcripts in cells transfected with plasmids carrying this bacterial sequence30,31. Thus, transcription from the cryptic colEl promoter and splicing from donor sites in the AS-AmpR region to the repeat tract gives rise to mature transcripts containing CAG repeats embedded in various 5’ sequence contexts (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that an expanded CAG repeat tract flanked by sequences native to the disease-causing gene can act as splice acceptor sites, and splicing from upstream donors may result in unexpected repeat-containing transcripts.

Canonical translation of aberrantly spliced CAG-repeat-containing RNAs accounts for RAN products.

We then investigated whether the spliced RNAs produced from disease associated mini-genes with repeat-containing ORFs might explain the production of spurious repeat-containing proteins. We examined the ATXN8 mini-gene, where the CAG repeat is immediately preceded by an AUG codon in the polyglutamine frame (Fig. 4A). Transfection of the ATXN8 plasmid in HEK293T cells resulted in the production of multiple polyglutamine-containing proteins (Fig. 4B), as has been previously reported10. Prior work demonstrated that mutation of the in-frame start codon immediately preceding the CAG repeats (construct ATXN8KKQ, Fig. 4A) eliminated one of the polyglutamine products, while other polyglutamine-containing proteins produced from this plasmid are not affected. These products have been attributed to non-canonical RAN translation of the repeat region10.

Figure 4. Canonical translation of aberrantly spliced CAG-repeat-containing RNA results in aberrant protein products.

A. Schematic for ATXN8 mini-gene. Upon splicing, the upstream stop codon is removed and the CAG repeat is embedded in an AUG-initiated ORF. B, C, D. Immunoblots from cells expressing the indicated ATXN8- and ATXN8KKQ- derived constructs that interrupt the predicted ORF by mutating the splice donor (B), mutating the identified in-frame AUG initiation codon (C), or by introducing a stop codon (D). Band intensities are normalized first to NPT (neomycin phosphotransferase), expressed in cis from the plasmid, and then to the endogenous protein (TBP, marked with an asterisk) in the control transfected with a similar vector but encoding for GFP (vector). Tubulin is included to show equivalent loading between conditions, but is not used for normalization due to potential variations in transfection efficiency. Immunoblots and quantification of relative polyglutamine abundance (as mean ± SD) are representative of > 2 independent transfections.

We found that these plasmids produced several spliced RNAs with AUG-initiated ORFs that contain the CAG repeats (Fig. 4A; see other ORFs in Supp. Fig. 5K). One of the major transcripts with an ORF in the polyglutamine frame arises due to splicing from a donor in the AS-AmpR cassette. Point mutations to this donor in AS-AmpR, ~1800 bases upstream from the CAG repeats, that abolished splicing at this site (Fig. 2C), also eliminated the aberrant polyglutamine product in both ATXN8 as well as ATXN8KKQ constructs (Fig. 4B). Splicing from this donor to CAG repeats creates an ORF with an AUG start codon located 135 nucleotides upstream from the donor site. Again, a single mutation to this AUG site, located in AS-AmpR, completely abolished the aberrant polyglutamine protein without affecting the canonical translation product (Fig. 4C). As an additional test for our model, we interrupted the AUG-initiated ORF with a single stop codon. This single-base mutation in the AS-AmpR region to generate a stop codon likewise eliminated the aberrant polyglutamine product (Fig. 4D).

Finally, we deleted a single nucleotide 10 bases upstream from the donor site, which would shift the translation frame for CAG repeats from polyglutamine to polyserine. Consistent with this expectation, the single-base deletion abrogated aberrant polyglutamine production with a concomitant ~500% increase in high-molecular weight polyserine-containing protein (Supp. Fig. 5L). Taken together, these results demonstrate that at least a subset of abnormal translation products arising from these mini-genes can be accounted for by splicing of upstream donors to CAG repeats followed by canonical AUG-initiated translation of the repeat-containing RNA. Even though the splicing donor sequences in these mini-genes used to model disease are non-native, our results suggest that disease-associated expanded CAG repeats, flanked by their native sequences, can act as splicing acceptors and potentially generate aberrant transcripts with repeat-containing ORFs.

Splicing from an endogenous donor in ATXN8 generates AUG-initiated ORFs.

Our observations raise the possibility that a similar mechanism may account for spurious, out of frame protein products observed in disease, where the region upstream of the repeat tract may provide a splice donor. We examined the sequence upstream of CAG repeats in the ATXN8 gene and found several potential splicing donor sites (5’ MaxEnt scores ≥ 1, Supp. Fig. 5M). We cloned 400 nucleotides of this native 5’ flanking sequence and placed it immediately upstream of 47×CAG repeats. Downstream of the repeats, we incorporated distinct epitope tags in each reading frame (Fig. 5A, sequence in Supplemental Table 4). Upon transducing this construct in U-20S cells, we observed one major splice donor that underwent splicing to the CAG repeat (5’ MaxEnt = 8.49). More than 90% of CAG ends reflected splicing to the repeats from this specific site (Fig. 5B). Disruption of this donor by a single-base mutation eliminated splicing from this location (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, when we mutated the original donor site, several new donor sites in the flanking sequence were spliced to the CAG repeats (5’ MaxEnt score for these sites ranging from 1.76 to 5.17 Fig. 5B, Supp. Fig. 5M). This observation is similar to other reports indicating that mutation of a splice donor can result in the activation of cryptic donor sites32, and suggests that the CAG repeat sequence in ATXN8 creates a strong splicing acceptor.

Figure 5. Splicing from an endogenous donor in ATXN8 generates AUG-initiated ORFs.

A. Schematic for design of ATXN8 mini-gene with 400 bases of endogenous ATXN8 sequence fused directly to 47><CAG repeats, followed by epitope tags in each reading frame. B. SATCfinder output for ATXN8 constructs with native upstream sequence, without or with a point mutation to the predicted donor site. C. Schematic for ORF resulting from ATXN8 minigene. Upon splicing, the CAG repeat is embedded in a new AUG-initiated ORF. D. Immunoblot for the indicated samples using an anti-HA antibody. The HA epitope is in the polyalanine frame. Immunoblots are normalized first to tubulin, then to the parent cell line without a repeat-containing construct (mock). Immunoblots and quantification of relative HA abundance (as mean ± SD) are representative of > 2 independent experiments.

Splicing from the identified donor site in ATXN8 creates an AUG-initiated ORF in the polyalanine frame (Fig. 5C). Polyalanine products have been observed in brain tissue from SCA8 patients10. In our synthetic construct, this spliced ORF encodes for an ~7 kD polyalanine containing protein which is detected via an HA-tag encoded downstream of the repeats in the polyalanine frame (Fig. 5D). Point mutations to the splicing donor or to the relevant AUG initiation codon abrogate polyalanine protein production (Fig. 5D, Supp. Fig. 5N-0). Although polyserine products have also been reported in SCA8 patient brains7, we do not observe translation of the repeat in the poly serine frame in this model (Supp. Fig. 5O). The small fragment of the ATXN8 gene that we cloned does not produce RNA with AUG-initiated ORFs in the poly serine frame. Nonetheless, further characterization of the 5’ end of the full-length ATXN8 transcript may reveal splice donors that could account for additional aberrant translation products that are observed in disease.

Discussion

The diseases caused by simple repeat expansions have diverse pathomechanisms that encompass dysfunction at DNA, RNA, and protein levels. Expanded CAG repeats in DNA form secondary structures that induce repeat instability during DNA replication and repair33-36. The repeat-containing RNAs may form inter-molecular base pairs and agglomerate in the nucleus to form foci that sequester essential RNA binding proteins3,4. When translated, the repeats produce aggregation-prone homopolymeric proteins37-39. Our work uncovers yet another route by which the disease-causing CAG repeats may trick the cellular machinery (see model in Fig. 6). Expanded CAG repeats may create new splicing acceptor sites. Nearby donors may splice into the repeats, and thus generate a variety of repeat-containing transcripts. These transcripts may contain AUG-initiated ORFs that encompass the repeat tract and produce unexpected, but canonically translated, polypeptides. This mechanism may account for a subset of abnormal polypeptides that are observed in various CAG repeat expansion disorders40-42.

Figure 6. Model for the sub-cellular localization of RNA with expanded CAG repeats.

In the absence of an expanded repeat, the RNA is normally processed and exported to the cytoplasm. If the RNAs contain expanded CAG repeats outside of an ORF, the RNAs are retained at nuclear foci, where they sequester splicing factors. If the CAG repeats are located downstream of potential splice donors, the donors may be spliced to the CAG repeat in a repeat number dependent manner. Splicing generates new RNA isoforms where the CAG repeat may be present in AUG-initiated ORFs. Translation of these AUG-initiated repeat-containing ORFs produces aberrant homopolymeric proteins that may aggregate and contribute to cellular toxicity.

Mechanistically, how the expanded CAG repeat tract induces mis-splicing of the repeat-containing transcript remains to be investigated. One possibility is that the expanded CAG repeats may provide a battery of alternative acceptor sites. More than 800 human genes contain tandem CAG repeats (≥2×CAG) at the 3’ splice sites43. In several cases, these repeats create alternative splice junctions, with the upstream donor being spliced to either of the two CAGs43. This differential utilization of the tandem splice sites, referred to as NAGNAG splicing, contributes to proteome diversity43,44. To test whether the expanded CAG repeats could be acting as alternative acceptor sites, we analyzed the RNA sequencing reads that span the entire repeat tract for relatively short repeats (10 and 22×CAG) that are accessible via short-read sequencing (Supp. Fig. 3E). At these repeat lengths, we observed that the primary acceptor was the first CAG of the repeat unit, accounting for at least 75% of the splicing events for 10×CAG and 50% of the splicing events for 22×CAG (Supp. Fig. 3F). Similar results were observed for a 47×CAG tract analyzed with long-read sequencing (Supp. Fig. 3G). It is important to note that PCR amplification, such as during sequencing library preparation, can lead to truncation in repeat number45,46. We observe substantial truncations during PCR even when using DNA with a fixed number of CAG repeats (Supp. Fig. 3G). Such truncations increase with repeat number and make it challenging for us to precisely identify the acceptor CAG within the repeat region. Another possibility is that the expanded repeats sequester proteins that alter splice site choice and efficiency. Splicing factors such as MBNL1 and SRSF6 bind RNAs with tandem CAG repeats6,47,48. An expanded repeat tract may recruit multiple copies of these splicing factors and affect splice site utilization. Supporting this model, CAG repeat-dependent RNA processing defects have been documented in multiple diseases6,15,17,18,47. A third possibility is that the repeats may undergo post-transcriptional splicing. CAG-repeat containing RNAs are retained at nuclear foci where they co-localize with numerous splicing factors. This retention at foci increases with repeat number5,49. Increased nuclear retention may augment post-transcriptional splicing, possibly even from moderately strong donor sites. These three models are not mutually exclusive and future work may shed light on the precise mechanisms driving increased splicing to expanded CAG repeats.

To what extent does splicing to tandem CAG repeats occur in disease? To address this question, we examined the publicly available RNA sequencing datasets generated from post-mortem brain and iPSC-derived neural cells from patients affected by HD, the best studied CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion disease50-55. From this composite dataset (~8 billion total reads), we mapped only 396 reads adjacent to the HTTCAG repeat tract (Supp. Fig. 6A), a notoriously under-represented region in sequencing data19 (Supp. Fig. 6B). We did not find statistically significant evidence supporting splicing to the HTT CAG repeat in this dataset beyond the background noise (Supp. Fig. 6A). These observations suggest that splicing to the expanded CAG repeat in HTT is likely rare, and occurs at a frequency of <0.5%, barring potential biases in RNA sequencing library preparation. By necessity, these studies were conducted on regions of the brain that were present in the postmortem tissue and may underrepresent the most affected cells. One potential implication of splicing to repeats would be the production of aberrant RAN translation products. RAN translation is only observed in a subset of cells (up to ~20% cells in the highly affected striatum) in HD postmortem tissue8. It is possible that splicing to the HTT CAG tract is rare and occurs only in a small fraction of cells and is below the detection limit of our current assays (Supp. Fig. 6C). Future studies employing appropriate disease samples and assays with increased coverage in the repeat region may allow us to unequivocally assess the extent of splicing to CAG repeats in disease.

It is also possible that some CAG repeat expansion disorders may not exhibit abnormal splicing to CAG repeats. Most CAG repeat loci in the genome do not serve as splicing acceptors (Supp. Fig 5A, Supp. Fig. IE), and evolutionary pressure may have purged cis-acting splicing-associated features (such as polypyrimidine tract) from these neighboring regions. To assess whether CAG repeat expansions at new genomic locations (i.e., locations that do not endogenously harbor a CAG repeat) could lead to splicing from adjacent donors, we introduced CAG repeats in an intron of ACTB in HEK293T cells (Supp. Fig. 6E). This intron has 8 isolated CAGs, four of which are predicted to be strong splice acceptor sites (3’ MaxEnt 2.76 – 9.47, Supp. Fig. 6F). These native single CAG trinucleotides do not act as splicing acceptors (Supp. Fig. 6G). We incorporated varying numbers of CAG repeats in this intron, isolated monoclonal cells at each repeat number, and characterized the transcribed RNAs using SATCfinder (Supp. Fig. 6H-L). We observed numerous reads where the upstream exon was spliced to the CAG repeats, in a repeat-number dependent manner (Supp. Fig. 6K-L). These reads reflecting splicing to the inserted CAG repeat were ~1% as abundant as the reads corresponding to the correctly spliced ACTB transcript (Supp. Fig. 6M). ACTB is an essential gene and only one locus in our polyploid cells was modified with the repeat insertion (see STAR Methods). Although the fraction of transcripts that are mis-spliced due to the repeat insertion is modest, these results underscore that expansions of CAG trinucleotide repeats in an appropriate context can produce de-novo splicing acceptors that sequester adjacent donor sites and result in aberrantly spliced mRNAs.

Our findings add to various molecular mechanisms that contribute to the aberrant proteins that are attributed to RAN translation40. Besides CAG repeat-expansion disorders, RAN translation has also been observed in several other repeat-expansion diseases. In fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), caused by CGG repeat expansion in FMR1, the RAN products in the polyglycine frame results from translation initiation at a near-canonical ACG start site56. Likewise, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, associated with GGGGCC repeat expansion in c9orf72, RAN translation in the glycine-alanine frame is dependent on the presence of a near-cognate CUG initiation codon in the upstream sequence57. Another possibility is that the secondary structures formed by GC-rich repeat containing RNAs may provide internal ribosome entry sites facilitating cap-independent translation58-60. GC-rich repetitive sequences can also result in ribosomal frameshifting, and generate chimeric proteins57,61-63. We show that in addition to these mechanisms, aberrant splicing of the repeat-containing transcript followed by canonical or potentially near-canonical translation initiation may also contribute to the production of RAN proteins. The location of repeats within a gene is usually annotated based on the wild-type gene without pathogenic expansion. Splicing aberrations may create new isoforms, and modify exon/intron annotations, as has recently been proposed for the c9orf72 repeat expansion64. Advances in long read sequencing technologies in conjunction with methods that allow mapping repetitive regions may reveal the full-length transcripts that are produced in disease, and help elucidate the disease mechanisms.

In conjunction with prior research, our findings help piece together a model for how CAG repeat-expansions affect RNA processing and sub-cellular localization (see model in Fig. 6). CAG repeats potentiate intermolecular RNA-RNA interactions, and an expanded repeat tract results in the sequestration of the repeat-containing RNA at nuclear foci. These foci co-localize with nuclear speckles and sequester various splicing factors, often inducing mis-splicing of other transcripts. If the repeat-containing RNA also harbors an appropriate splice donor, this donor may be spliced to the expanded CAG repeats, facilitating its export to the cytoplasm. Splicing may place the repeats in AUG-initiated ORFs. Canonical translation of such repeat-containing ORFs may produce homo-polymeric peptides that form pathogenic aggregates. Our results provide a new lens to examine the role of cis-acting sequences as modifiers of CAG-repeat induced cell toxicity, and suggest that modulating RNA splicing could be a potential target for the development of therapeutic interventions.

Limitations of the Study

Untargeted RNA sequencing approaches do not provide sufficient coverage in the repeat region and we were unable to detect splicing to CAG repeat tract in RNA-sequencing data in HD patient samples. The contribution of such splicing events to disease thus remains to be determined. Target-enrichment approaches or amplicon sequencing by designing primers based on putative donors in the upstream region may potentially allow one to assess the prevalence of splicing when the pathogenic repeats are expressed from their endogenous loci. The molecular mechanism by which an expanded CAG repeat stimulates splicing has not been addressed by this work and remains to be investigated.

STAR Methods

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Ankur Jain (ajain@wi.mit.edu).

Materials Availability

All cell lines and plasmids generated in this study are listed in the key resources table and are available upon request to the lead contact.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F1804, RRID:AB_262044 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA | BioLegend | Cat# 901501, RRID:AB_2565006 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-polyglutamine | Millipore | Cat# MAB1574, RRID:AB_94263 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Neomycin Phosphotransferase II | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# MA5–15275, RRID:AB_10979669 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-β-tubulin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2146, RRID:AB_2210545 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit, HRP conjugate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A0545, RRID:AB_257896 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse, HRP conjugate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A9044, RRID:AB_258431 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Stbl3 E. coli | Invitrogen | Cat# C7373–03 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| doxycycline | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# D9891 |

| dimethyl sulfoxide | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# D2650 |

| pladienolide B | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | CAT# SC391691 |

| isoginkgetin | Tocris Bioscience | CAT# 6483 |

| sodium chloride | Invitrogen | CAT# AM9760G |

| NP-40 | Fisher Scientific | CAT# AAJ19628AP |

| sodium deoxycholate | Sigma-Aldrich | CAT# D6750 |

| sodium dodecyl sulfate | Bio-Rad | CAT# 1610302 |

| HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitors | Thermo Scientific | CAT# 78429 |

| Benzonase nuclease | EMD Millipore | CAT# E1014 |

| dithiothreitol | Thermo Scientific | CAT# R0861 |

| methanol | VWR | CAT# EM-MX0475–1 |

| Coomassie Brilliant blue R 250 | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# 1125530025 |

| acetic acid | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# 695092 |

| Hybridase RNase H | Lucigen | CAT# H39500 |

| Turbo DNase | Invitrogen | CAT# AM2238 |

| TGIRT reverse transcriptase | Ingex | CAT# TGIRT |

| Ambion RNase-free buffer kit | Invitrogen | CAT# AM9010 |

| Cycloheximide | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# C1988–1G |

| RNasin Plus | Promega | CAT# N2615 |

| cOmplete protease inhibitor | Roche | CAT# 11836170001 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| xGen Broad-Range RNA Library Preparation Kit | IDT | CAT# 10009813 |

| MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit | Invitrogen | CAT# AMB13345 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw RNA sequencing data | This paper | SRA: PRJNA1007766 |

| Raw western blot images | This paper | Mendeley DOI: 10.17632/2r2scm54sn.1 |

| Raw representative fluorescent micrographs | This paper | Mendeley DOI: 10.17632/2r2scm54sn.1 |

| Original code & SATCfinder pipeline | This paper | Zenodo DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10080617 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, brain tissue | Labadorf et al.50 | GEO: GSE64810 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, brain tissue | Lin et al.51 | GEO: GSE79666 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, iPSC-derived | Mehta et al.52 | GEO: GSE109534 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, brain tissue | Agus et al.53 | GEO: GSE129473 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, iPSC-derived | Smith-Geater et al.54 | GEO: GSE144559 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, iPSC derived | Świtońska et al.55 | GEO: GSE124664 |

| Huntington’s disease RNA-seq, brain tissue | n/a | GEO: GSE159940 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human: U-2 OS cells | ATCC | Cat# HTB-96; RRID:CVCL_0042 |

| Human: HEK293T cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216; RRID:CVCL_0063 |

| Human: RPE-1 cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-4000; RRID:CVCL_4388 |

| Mouse: NIH/3T3 cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1658, RRID:CVCL_0594 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Supplemental Table 3 for Oligonucleotides. | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Unmodified CAGRAN lines | Das et al.12 | Supp. Table 4 |

| Unmodified CAGFOCI lines | Das et al.12 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN*donors 240×CAG 12×MS2 WPRE | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN*AUGs 240×CAG 12×MS2 WPRE | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN5×CAG 5×CAG 12×MS2 WPRE | Das et al.12 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN10×CAG 10×CAG 12×MS2 WPRE | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN22×CAG 22×CAG 12×MS2 WPRE | Das et al.12 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN47×CAG 47×CAG 12×MS2 WPRE | Das et al.12 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR CAGRAN-BFP 240×CAG EBFP2 12×MS2 WPRE | Das et al.12 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATNX8 100×CAG | Zu et al.10 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KKQ 100×CAG | Zu et al.10 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 HTT 100×CAG | Zu et al.10 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 HDL2 100×CAG | Zu et al.10 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 SCA3 100×CAG | Zu et al.10 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 DMPK-AS 100×CAG | Zu et al.10 | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KKQ*flanking donor 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KMQ*AS-AmpR donor 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KMQ*AS-AmpR AUG 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KKQ*AS-AmpR donor 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KKQ*AS-AmpR AUG 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KKQ,AS-AmpR stop 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 ATXN8KKQ,AS-AmpR frameshift 100×CAG | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR ATNX8 400bp endogenous sequence | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR ATXN8*donor 400bp endogenous sequence | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pHR ATXN8*AUG 400bp endogenous sequence | This paper | Supp. Table 4 |

| pcDNA3.1 EGFP, vector control | Xiao et al.66 | Addgene plasmid #129020 |

| pCMV-VSV-G, Lentivirus packaging | Stewart et al.67 | Addgene plasmid #8454 |

| psPAX2, Lentivirus packaging | n/a | Addgene plasmid #12260 |

| pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 | Cong et al.68 | Addgene plasmid #42230 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism v10.0.3 | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 http://www.graphpad.com/ |

| ImageJ v1.53q | Schneider et al.71 | RRID:SCR_003070 https://imagej.net/ |

| samtools v1.11 | Danecek et al.80 | RRID:SCR_002105 http://www.htslib.org/ |

| BBTools v38.86 | Brian Bushnell | RRID:SCR_016968 https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/ |

| STAR v2.7.1a | Dobin et al.79 | RRID:SCR_004463 https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| pysam v0.16.0.1 | n/a | RRID:SCR_021017 https://github.com/pysam-developers/pysam |

| StringTie v2.2.1 | Pertea et al.29 | RRID:SCR_016323 http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/ |

| featureCounts v1.6.2 | Liao et al.81 | RRID:SCR_012919 |

| ggsashimi v1.0.0 | Garrido-Martin et al.84 | https://github.com/guigolab/ggsashimi |

| MaxEntScan | Yeo and Burge.25 | http://hollywood.mit.edu/burgelab/maxent/Xmaxentscan_scoreseq.html |

| MaxEntPy | n/a | https://github.com/kepbod/maxentpy |

| CHOPCHOP | Labun et al.72 | RRID:SCR_015723 http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/ |

| Canu v2.1.1 | Koren et al.73 | RRID:SCR_015880 https://github.com/marbl/canu |

| minimap2 v2.24-r1122 | Li.82 | RRID:SCR_018550 https://github.com/lh3/minimap2 |

| LIQA v1.3.0 | Hu et al.83 | https://github.com/WGLab/LIQA |

| Other | ||

| Fetal bovine serum | Gibco | CAT# 26140079 |

| Penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine 100X | Gibco | CAT# 10378016 |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium | Gibco | CAT# 11965126 |

| Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium | Gibco | CAT# 12440053 |

| Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Solution | Gibco | CAT# 14190144 |

| Opti-Mem | Gibco | CAT# 31985070 |

| Trypsin-EDTA 0.25% | Gibco | CAT# 25200072 |

| Lipofectamine LTX | Invitrogen | CAT# 15338100 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Invitrogen | CAT# L3000001 |

| Polybrene | Millipore Sigma | CAT# TR1003G |

| Tris-HCl pH 7.5 | Invitrogen | CAT# 15567027 |

| PBS, pH=7.2 | Gibco | CAT# 20012–027 |

| Nuclease-free water | Invitrogen | CAT# AM9932 |

| Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | Sigma-Aldrich | CAT# A7906 |

| NuPAGE 4x LDS sample buffer | Invitrogen | CAT# NP0008 |

| 4–12% Bis-tris polyacrylamide gel | Invitrogen | CAT# NW04122 |

| iBlot 2 Transfer Stacks, PVDF | Invitrogen | CAT# IB24002 |

| iBlot 2 Dry Blotting System | Invitrogen | CAT# IB21001 |

| 26-gauge needle | Becton Dickinson | CAT# 305110 |

| 22-gauge needle | Becton Dickinson | CAT# 511055 |

| Skim milk powder | BD Biosciences | CAT# 232100 |

| Tris-buffered saline | Fisher Scientific | CAT# AAJ60764K3 |

| Tween-20 | Fisher Scientific | CAT# BP337 |

| SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate | Thermo Scientific | CAT# 34095 |

| Novex Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer | Fisher Scientific | CAT# LC2676 |

| UltraPure Agarose | Invitrogen | CAT# 16500500 |

| DNA Clean & Concentrate | Zymo | CAT# D4004 |

| PureLink RNA mini kit | Invitrogen | CAT# 12183018A |

| PureLink DNA mini kit | Invitrogen | CAT# K182001 |

| ezDNase | Invitrogen | CAT# 11766050 |

| SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix | Invitrogen | CAT# 11756050 |

| DNA QuickExtract solution | Lucigen | CAT# QE09050 |

| KOD Hot Start 2× Master Mix | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# 71842–3 |

| Advantage GC 2 polymerase | Takara Bio | CAT# 639114 |

| Trypan Blue Stain (0.4%) | Invitrogen | CAT# T10282 |

| RNAClean XP beads | Beckman Coulter | CAT# A63987 |

Data and Code Availability

RNA-seq data have been deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. Original western blot images and fluorescent micrographs were deposited at Mendeley and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is listed in the key resources table. This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for these datasets are listed in the key resources table.

All source code for the SATCfinder pipeline has been deposited at Zenodo and is publicly available as of the date of publication. Other bioinformatic pipelines used in this work are described in STAR Methods.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell lines

HEK293T (CRL-3216; RRID:CVCL_0063), RPE-1 (CRL-4000; RRID:CVCL_4388), U-20S (HTB-96; RRID:CVCL_0042), andNIH-3T3 (CRL-1658; RRID:CVCL_0594) were obtained from ATCC and were tested for mycoplasma at least quarterly using MycoAlert (Lonza LT07-318). Cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco 11965126) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco 26140079) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine (PSG; Gibco 10378016). Cells were passaged 3 times per week at 1:10 dilution using Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Solution (DPBS; Gibco 14190144) and trypsin (Gibco 25200072).

Organisms/Strains

Plasmids were propagated in Stbl3 E. coli (Invitrogen C737303) grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. AS-AmpR mutants grew poorly on LB/agar plates supplemented with 100 μg/mL carbenicillin without an extended outgrowth period (>1 hour). All plasmids were verified by Oxford Nanopore sequencing (Plasmidsaurus or Quintara Bioscience) or by Sanger sequencing using a modified protocol with added 7-deaza dGTP and betaine to allow sequencing through tandem repeats.

Methods details

Cloning and plasmid generation

Complete sequences for all plasmids used in this study are provided in Supplemental Table 4. Lentiviral transfer plasmids with CAG-repeats and MS2-hairpins were previously described5, as were the plasmids with 240×CAG repeats with various upstream flanking sequences (including CAGRAN and CAGFOCI)12. Plasmids with ~110 CAG repeats and endogenous flanking sequences from ATXN8, JPH3, DMPK, HTT and ATXN3 were a generous gift from Dr. Laura Ranum10. pcDNA3.1(+) EGFP was a gift from Jeremy Wilusz (Addgene plasmid #129020)66. pCMV-VSV-G was a gift from Bob Weinberg (Addgene plasmid #8454)67. psPAX2 was a gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #12260). pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 was a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid #42230)68. Expanded CAG repeats are difficult to amplify using polymerase chain reaction, and make it challenging to incorporate point mutations using site-directed mutagenesis. Instead, mutations were incorporated by using synthetic double stranded DNA fragments that replaced the corresponding fragments in the plasmids. Double stranded DNA fragments with mutations to CAGRAN splice donor and AUG sites (to generate CAGRAN*donors and CAGRAN*AUGs, respectively) were prepared by overlap extension PCR (see oligo sequences in Supplemental Table 3), and inserted between MluI and EcoRI sites in CAGRAN. CAGRAN constructs with varying repeat lengths were prepared by oligo annealing and inserted between the EcoRI and NotI sites. ATXN8 mutants to AS-AmpR were generated with overlap extension PCR, then inserted between BspHI sites in the ATXN8 or ATXN8KKQ constructs. Splice donors adjacent to the CAG repeat tract were mutated by overlap extension PCR, then Gibson assembled into XbaI and SacI-digested ATXN8KKQ. The endogenous 400 bp ATXN8 constructs, and splice donor and AUG mutants, were prepared by overlap extension PCR and inserted between MluI and NotI sites.

Cell culture

U-2OS cells stably expressing a TetOn 3G transactivating protein and MS2-hairpin binding protein fused to YFP were previously described5. RPE-1 and NIH-3T3 cells expressing the same proteins were prepared similarly by sequential lentiviral transduction and selection.

For transient transfections, HEK293T cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at 750,000 cells/well overnight. 2-4 μg of plasmid was mixed with 500 μL Opti-Mem (Gibco 31985070), after which 2.5 μL Plus Reagent and 8 μL Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen 15338100) were added. After a 10-minute incubation at room temperature (22 °C), the mixture was added dropwise to wells containing 1 mL Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM; Gibco 12440053). After 6 hours, the media was exchanged for DMEM with FBS and PSG.

To prepare lentivirus, HEK293T cells were transfected as described above in 6-well plates with 2 pg of transfer plasmid, 0.5 μg envelope plasmid (Addgene #8454), and 1 μg packaging plasmid (Addgene #12260). 24 hours post transfection, the viral supernatant was collected and spun at 24,000×g for 10 minutes at room temperature. U-20S cells were transduced at varying viral titer in fresh DMEM with FBS and PSG and 10 μg/mL polybrene (Millipore Sigma TR1003G) to increase transduction efficiency.

To induce transgene expression, cells were plated to be 80% confluent at time of use and were treated with 1 μg/mL doxycycline (Sigma Aldrich D9891) for 24 hours prior to use. For splicing inhibition, Tet-inducible cells were induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline and co-treated with 0.1% DMSO (Sigma Aldrich D2650) or pladienolide B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC391691) at the indicated concentrations (12.5, 25, or 50 nM, depending on the assay) for 24 hours prior to analysis. For splicing inhibition during transient transfection, cells were transfected as above, and after 6 hours, the media was exchanged for DMEM with FBS and PSG, with 25 nM pladienolide B, or 15 μM isoginkgetin (Tocris Bioscience 6483), or 0.1% DMSO as control.

Western blot

Cells were washed with DPBS and lysed with 160 μL RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 (Invitrogen 15567027), 150 mMNaCl (Invitrogen AM9760G), 1% (v/v) NP-40 (Fisher Scientific AAJ19628AP), 1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate (Sigma-Aldrich D6750), 0.1% (w/v) SDS (Bio-Rad 1610302)) supplemented with 1% (v/v) HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific 78429) and 125 U/mL Benzonase nuclease (EMD Millipore E1014). The cell lysate was homogenized by passing through a 26-gauge needle (Becton Dickinson 305110) 5 times, and incubated on a nutator for 30 minutes at 4 °C. We noticed that polyglutamine-containing proteins were frequently lost in the pellet fraction after centrifugation at 21000×g or even at 3000×g for 5 minutes. Thus, homogenized lysate was used without further clean-up for electrophoresis. Lysates were incubated with NuPAGE 4× LDS buffer (Invitrogen NP0008) with 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT; Thermo Scientific R0861) at 70 °C for 5 minutes for most assays. When probing polyalanine-containing proteins, we observed substantial aggregation when lysates were heat denatured at or above 70 °C. Instead, when detecting polyalanine proteins, denaturation was performed at 37 °C for 5 minutes, as is recommended for hydrophobic transmembrane proteins69,70, and this denaturation condition substantially reduced polyalanine aggregation (Supp. Fig. 8C). Samples were separated on a Bolt 4-12% Bis-tris polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen NW04122) run at 200 V for 30 minutes (for 7 kD MW endogenous ATXN8 constructs) or 42 minutes (all other samples). Samples were transferred to PVDF membranes (Invitrogen IB24002) using the iBlot 2 dry blotting system (Invitrogen IB21001). Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) skim milk (BD Biosciences 232100) in TBST (tris-buffered saline (Fisher Scientific AAJ60764K3) with 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (Fisher Scientific BP337) for one hour at room temperature, then incubated with primary antibodies in 1% (w/v) skim milk in TBST at 4 °C overnight. The membranes were washed 4 times for five minutes each with TBST, then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody in 1% (w/v) skim milk for one hour at room temperature. After 4 five-minute washes in TBST, chemiluminescence was detected using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific 34095) with a ChemiDoc XRS+ imager (Bio-Rad). Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: mouse anti-FLAG (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich FI804), mouse anti-HA (1:1000, BioLegend 901501), mouse anti-polyQ (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich MAB1574), mouse anti-NPT (1:2000, Invitrogen MA5–15275), rabbit anti-β-tubulin (Cell Signaling Tech. 2146). Secondary antibodies: goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugate (Sigma Aldrich A0545), rabbit anti-mouse HRP conjugate (Sigma Aldrich A9044). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.53q)71, with background subtraction performed per-lane.

N-terminal protein sequencing of CAGRAN

Four 10-cm dishes expressing CAGRAN fused to BFP at the C-terminus12, downstream of the repeat tract, were induced with doxycycline. After 24 hours, the cells were washed once with DPBS and then lysed with 1 mL of RIP A buffer supplemented with HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitors and DTT. The cell lysate was collected by scraping and homogenized by passing through a 22-gauge needle (Becton Dickinson 511055) 10 times, and incubated on a nutator for 30 minutes at 4 °C. The lysate was loaded onto 70 μL of GFP-Trap beads (Chromotek gtma-20) which were pre-washed once with RIPA wash buffer (as above, but with 0.15% NP-40). The lysates were incubated on a nutator for 90 minutes at 4 °C, after which the beads were sedimented at 2,500×g for 5 minutes at 4 °C, then washed with 500 μL RIPA wash buffer. After four total wash steps, 80 μL of 2× SDS buffer (Fisher Scientific LC2676) and 8 μL of 1 M DTT was added. The beads were boiled at 95 °C for 10 minutes, then the supernatant was separated on a Bolt 4-12% Bis-tris polyacrylamide gel run at 200 V for 32 minutes, and finally transferred to PVDF membrane using the iBlot 2 dry blotting system. The membrane was rinsed with water, then soaked in 100% methanol (VWR EM-MX0475-1) for 10 seconds, and stained with Coomassie blue staining solution (40% (v/v) methanol, lg/L Coomassie R250 (Sigma Aldrich 1125530025), 1% acetic acid (Sigma Aldrich 695092) for one minute. The membrane was destained with 50% (v/v) methanol until the destaining solution remained colorless, rinsed with water, and dried at room temperature. Bands extracted from the PVDF membrane were subjected to N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation (Molecular Structure Facility, UC Davis).

Generation of ACTBCAG knock-in cell lines

A CRISPR guide was designed using CHOPCHOP72 to select a site which might be able to act as a polypyrimidine tract. We designed a ssDNA repair template with 40×CAG repeats and 40 base homology arms targeting the cut site in intron 3 of ACTB (sequence in Supplemental Table 3, and see Supplemental Fig. 7E-N). This repair template was obtained as a synthetic oligonucleotide (IDT) and transfected in HEK293T cells. In brief, 2 μg of plasmid expressing CRISPR-Cas9 and guide (Addgene #42230) and 40 pmol ssDNA repair template were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen L3000001) following manufacturers’ instructions, using 7.5 μL of L3000 reagent. A GFP plasmid (0.2 μg) was co-transfected to facilitate isolation of transfected cells. After 48 hours, cells were dissociated using trypsin, resuspended in DPBS, and sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using an Aria III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences). The top 25% of GFP positive cells were plated as single cells and expanded to monoclonal populations.

Approximately 50 clones were isolated and examined for the incorporation of CAG repeats at the desired locus using PCR screening as follows. Approximately ~5000 cells were pelleted and after removing the residual media, 50 μL DNA QuickExtract solution (Lucigen QE09050) was added. The mixture was vortexed, heated at 65°C for 10 minutes and 95 °C for 5 minutes, and then diluted to 200 μL with nuclease-free water. The locus with expected insertion was amplified by PCR using 5 μL KOD Hot Start 2× Master Mix (Sigma Aldrich 71842-3), 0.2 μL each primer at 10 μM, 0.5 μL DMSO, 1 μL gDNA, and 3.1 μL water, with denaturation at 95 °C for 20 seconds, annealing at 60 °C for 10 seconds, and extending at 70 °C for8 seconds for 40 cycles. The ~300 bp thus generated amplicons were visualized by 2% agarose gel (Invitrogen 16500500). Unexpectedly, we found wide variability in the amplicon size for 40×CAG reflecting that each clone had a different number of CAG repeats. The number of CAG repeats in each clone were stable and did not measurably vary on our experimental timescales.

We selected 20 clones with variable insertion sizes for further validation using nested PCR. The outer PCR was performed as above, but for 25 cycles with 15 second extension to amplify a ~1300 bp region. Excess primers were degraded by adding 0.5 μL of thermolabile exonuclease I (NEB m0568) at 37 °C for 15 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 80 °C for 5 minutes. 1 μL of this mixture was used as template in a 25 μL reaction for inner PCR for 25 cycles, amplifying an ~800 bp region as above. The final amplicons were subjected to PCR clean up (Zymo D4004) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and single molecule sequencing using Oxford Nanopore (Plasmidsaurus). Reads entirely spanning the CAG repeat insertion site were selected with sequential runs of bbduk with options "k=20 literal={5’ ACTCTCTTCTCTGACCTGAG or 3’ CTCTCTTCTCTGACCTGAGT} rcomp=t hdist=0 mm=f", then assembled using Canu73 v2.1.1 using options "-p asm useGrid=0 genomeSize=1000 minReadLength=100 minOverlapLength=100 corMinCoverage=50 corMaxEvidenceErate=0.15-nanopore-raw {file.fq}". From 20 clones screened, we found repeats tracts of length 5 – 39×CAG. We speculate that this variability is caused by a hairpin formed by the ssDNA template during repair. The clones we selected for RNA-seq had consistent repeat lengths among the sequencing reads, indicating that a single allele was edited. ~30% of reads spanning the insert region had a CAG repeat, suggesting the ACTB gene is triploid in our HEK293T cells, consistent with prior reports74.

Real-time quantitative and endpoint PCR

RNA and DNA were isolated from ~106 cells using PureLink RNA (Invitrogen 12183018A) and PureLink Genomic DNA (Invitrogen K182001) mini kits, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For reverse transcription, contaminating genomic or plasmid DNA was removed using ezDNase (Invitrogen 11766050), followed by reverse transcription using Superscript IV VILO master mix (Invitrogen 11756050). Briefly, 1 μg total RNA in a 5 μL volume was incubated with ezDNase at 37 °C for 2 minutes. This reaction was diluted with 3 μL nuclease-free water before addition of 2 μL Superscript IV VILO master mix. The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 minutes to anneal primers, 50 °C for 20 minutes for reverse transcription, followed by inactivation at 85 °C for 5 minutes.

For quantitative PCR, 2.5 ng of total RNA, or 5 pg of plasmid DNA, or 10 ng of genomic DNA, were quantified with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems 4309155) using the QuantStudio 3 RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems A28567). For determination of relative abundance of the CAGRAN intron region, primers targeted the intronic region or the 5’ end of the transcript region. Intron abundance was normalized relative to the 5’ end of the transcript. For CAGRAN*AUG, which has mutations in the 5’ region, the intron was normalized relative to the 3’ end of the repeats. For estimation of transgene copy number, the 5’ end of the transcript was normalized to primers targeting ACTB. See primer sequences in Supplemental Table 3.

For endpoint PCR, 10 ng of total RNA, or 100 ng of genomic DNA was amplified with Advantage GC 2 polymerase (Takara Bio 639114) using 1 M GC Melt and primers spanning the region from upstream of the splice donors to the 3’ end of the repeat, or to the 3’ end of the transcript. The reactions were cycled 25 (cDNA) or 35 (genomic DNA) times, with denaturation at 94 °C for 10 seconds, annealing at 58 °C for 10 seconds, and extension at 68 °C for 25 or 45 seconds. The amplicons were separated on a 3% agarose gel. For sequencing, the PCR reaction was cleaned up with Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrate kit (D4004) and Sanger sequenced (Quintara Biosciences), or by Nanopore long-read sequencing (Plasmidsaurus).

Cell toxicity assays

Cell toxicity assays were performed as previously described 12. In brief, ~10,000 cells were plated into a 6-well plate. The next day, the media was replaced with DMEM with FBS and PSG supplemented with or without doxycycline. After five days, when the cells were approximately 75% confluent, the supernatant containing floating (dead) cells was collected. Cells were washed with DPBS to collect loosely attached cells, and were added to the supernatant. The adherent cells were trypsinized and added to the supernatant. Cells were pelleted at 500×g for 3 minutes, then resuspended in 200 μL DMEM. Dead cells were stained with trypan blue (Invitrogen T10282). The cell count and proportion of dead cells were quantified for ≥ 3 technical replicates using a Countess IIFL Automated Cell Counter (ThermoFisher AMQAflOOO). The cell count for doxycycline induction was normalized to the without-doxycycline condition for each of three biological replicates per condition. The percent of dead cells reflects the number of cells with non-intact membranes, which take up trypan blue.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from ~106 (6-well) or ~8x106 (10 cm dish) cells using the PureLink RNA mini kit. RNA quality was verified by denaturing agarose gel or Bioanalyzer. In-house ribodepletion was performed as described previously75. In brief, 2.5 μg of total RNA was mixed with 5 μg of ribodepletion oligos (IDT oligo pool, sequences in Supplemental Table 3) and 2 μL of 5× hybridization buffer (100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), to a total volume of 10 μL. The RNA and oligos were hybridized by heating to 95°C for 2 minutes and cooling to 45 °C at −0.1 °C/s. While maintaining samples at 45 °C, 1.5 μL of Hybridase RNase H (Lucigen H39500), 3 μL of 5× RNase H buffer (167 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2), and 0.5 μL of water were added, and the reaction was incubated at 45 °C for 30 minutes. The ribodepleted RNA was cleaned using 2× RNAClean XP beads (Beckman Coulter A63987), eluting with 20 μL DNase digestion reaction mixture (1.5 μL Turbo DNase (Invitrogen AM2238), 2 μL Turbo DNase 10X buffer, and 16.5 μL RNase-free water). The residual DNA oligos were digested at 37 °C for 30 minutes, and the resulting mRNA was cleaned using 2× RNAClean XP beads and eluted in 11.5 μL nuclease-free water.

The ribodepleted RNA (typically ~5% of input, or about 100 ng) was reverse transcribed using a group II intron reverse transcriptase (TGIRT, Ingex) using primers provided by the xGen library preparation kit (IDT 10009813). In brief, 10 μL ribodepleted RNA was mixed with 4 μL 5× TGIRT buffer (2.25 MNaCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; Ambion RNase-free Buffer Kit AM9010), and 1 μL random hexamer primers (xGen). The mixture was heated to 94 °C for 12 minutes to induce RNA fragmentation. After cooling at 4 °C for 2 minutes to allow primer binding, 1 μL 100 mM DTT (xGen), 1 μL TGIRT enzyme, and 1 μL RNase inhibitor (xGen) was added and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes to allow TGIRT binding to RNA-primer duplexes. To initiate reverse transcription, 2 μL dNTPs (xGen) were added, followed by sequential incubation for 15 minutes each at 20 °C, 42 °C, 55 °C, and 65 °C for elongation. This step-wise protocol is needed for TGIRT to extend the unstable RNA-DNA duplexes formed by random hexamer primers76. At completion, TGIRT was dissociated from the RNA-DNA duplexes by addition of 1 μL 5 M NaOH (VWR BDH7225-1) with incubation at 95 °C for 3 minutes, then neutralized with 1 μL 5 M HC1 (VWR BDH7419-1). The remainder of the library preparation was performed according to the xGen protocol except that post-ligation, the library was eluted in 30 μL nuclease-free water, followed by a modified protocol for final amplification and incorporation of sequencing adaptors. The final amplification was performed in a 50 μL reaction with 1 μL Advantage GC2 polymerase, 10 μL 5× GC2 buffer, 5 μL (1M) GC melt, 1 μL of 10 mM dNTPs (NEB N0447L), 1 μL GC2 polymerase, 4 μL xGen adapter mix, and 29 μL eluted library. Typically, ~10 cycles of PCR with denaturation at 94 °C for 20 seconds, annealing at 58 °C for 20 seconds, and extension at 68 °C for 45 seconds, for final amplification yielded sufficient material for quality control and sequencing. Libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) by the Whitehead Institute Genome Technology Core or by Novogene.

SATCfinder pipeline and RNA-seq analysis

The SATCfinder pipeline and full documentation are available at https://github.com/AnkurJainLab/SATCfmder. In brief, the SATCfinder pipeline first selected reads containing ≥3×CAG or CTG, along with their read mates, if available, using bbduk (BBTools 38.86)77 with options “k=9 hdist=0 mm=f literal=CAGCAGCAG rcomp=t”. At this step, read pairs not containing any repeats were discarded. Low quality read ends and sequencing adapters were removed from the reads using cutadapt (version 3.7)78 with commands “-a AGATCGGAAGAG —error-rate=0.1 —times=1 —overlap=5 — minimum-length=20 --quality-cutoff=20”. Next, the CAG-selected reads were processed using a custom Python script, the SATCfinder trim module. This script converts FASTQ files to unmapped SAM files, during which CAG/CTG repeats (minimum 3, maximum unlimited) are computationally trimmed from the read according to the following rules: (1) CAG repeats and anything downstream of the repeat, is trimmed and saved to a SAM field; (2) CTG repeats, and anything upstream of them, is trimmed and saved to a SAM field. In both cases, the length of the trimmed repeat tract (but not any additional removed sequences) is saved in a SAM field. Repeats will be trimmed from both reads if paired end reads are provided. Reads with at least 15 bases post-trimming and their corresponding read mates are stored in the SAM file. These reads were then aligned to hg38 with GRCh GTF annotation file (38.93) using the short-read alignment tool STAR (version 2.7.1a)79. STAR alignment arguments were outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate “--outSAMunmapped Within -- genomeFastaFiles {construct.fa} --readFilesType SAM (library type}”, where construct.fa refers to a relevant transgene fasta sequence if required, and library type refers to SE or PE for single and paired end libraries respectively.

The aligned BAM files were indexed using samtools (version l.l)80. Trimmed reads were separated from their read mates and stored in a BAM file which only contains reads with trimmed repeats. This file is then processed by a second SATCfinder module, SATCfinder ends. This script takes as input a BAM file, along with genomic coordinates and strand information for a region of interest, and uses pysam (version 0.16.0.1) to generate a .csv file containing the base position and the number of CAG ends at that base for the given region. This csv file can then be used in standard plotting software to generate bar plots as in Fig. 1A-B, which were prepared with GraphPad Prism.