Abstract

Aim:

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) is dysregulated after cardiac arrest. It is unknown if post-arrest CBF is associated with outcome. We aimed to determine the association of CBF derived from arterial spin labelling (ASL) MRI with outcome after pediatric cardiac arrest.

Methods:

Retrospective observational study of patients ≤18 years who had a clinically obtained brain MRI within 7 days of cardiac arrest between June 2005 and December 2019. Primary outcome was unfavorable neurologic status: change in Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) ≥1 from pre-arrest that resulted in hospital discharge PCPC 3–6. We measured CBF in whole brain and regions of interest (ROIs) including frontal, parietal, and temporal cortex, caudate, putamen, thalamus, and brainstem using pulsed ASL. We compared CBF between outcome groups using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum and performed logistic regression to associate each region’s CBF with outcome, accounting for age, sex, and time between arrest and MRI.

Results:

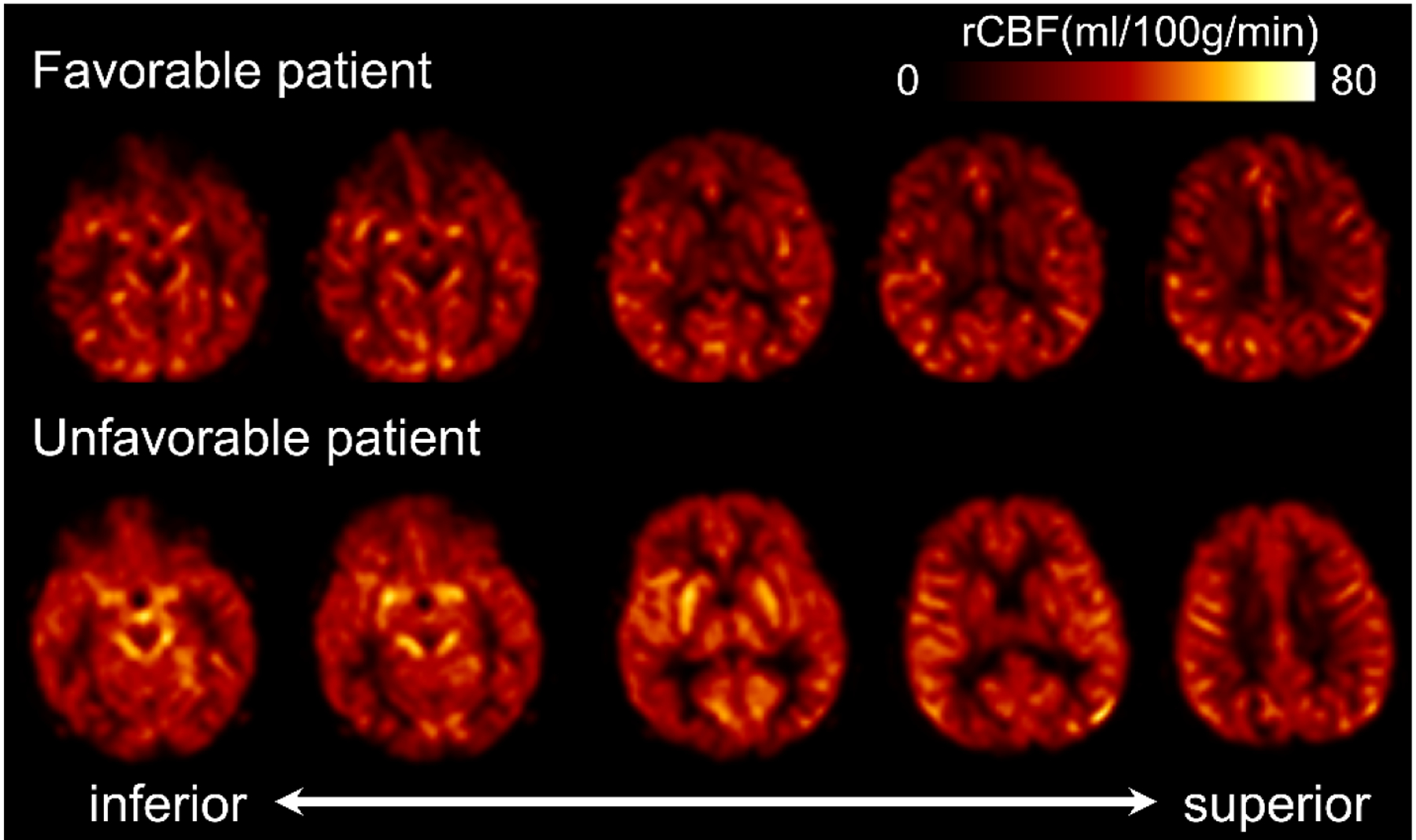

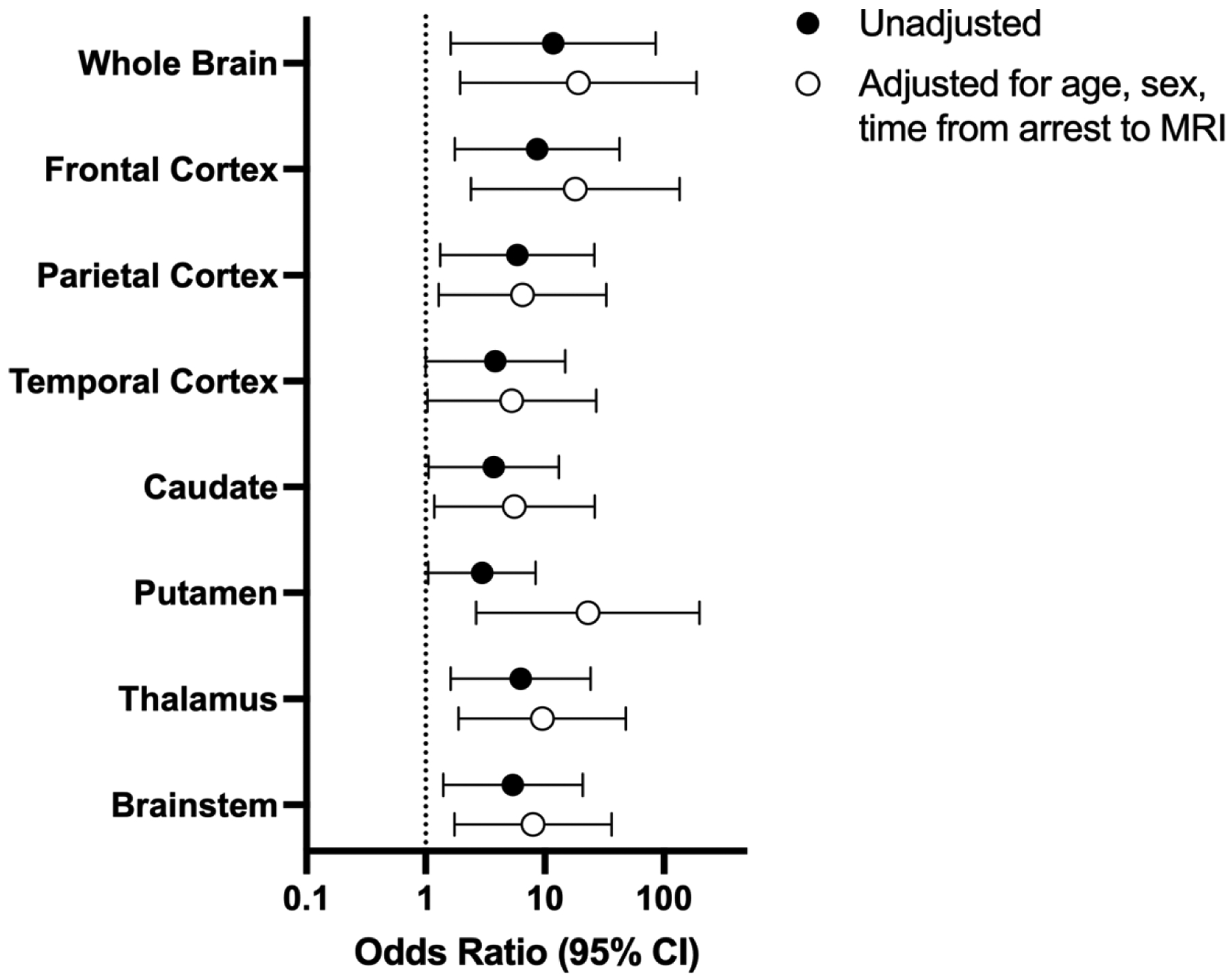

Forty-eight patients were analyzed (median age 2.8 [IQR 0.95, 8.8] years, 65% male). Sixty-nine percent had unfavorable outcome. Time from arrest to MRI was 4 [3, 5] days and similar between outcome groups (p=0.39). Whole brain median CBF was greater for unfavorable compared to favorable groups (28.3 [20.9,33.0] vs. 19.6 [15.3,23.1] ml/100g/min, p=0.007), as was CBF in individual ROIs. Greater CBF in the whole brain and individual ROIs was associated with higher odds of unfavorable outcome after controlling for age, sex, and days from arrest to MRI (aOR for whole brain 19.08 [95% CI 1.94, 187.41]).

Conclusion:

CBF measured 3–5 days after pediatric cardiac arrest by ASL MRI was independently associated with unfavorable outcome.

Keywords: pediatric cardiac arrest, neuroimaging, MRI, arterial spin labeling

Introduction

Hypoxic ischemic brain injury (HIBI) is the major cause of morbidity and mortality after pediatric cardiac arrest.1–3 Cerebral blood flow is dysregulated after resuscitation from cardiac arrest and may lead to cerebral hypo- or hyper-perfusion and secondary brain injury.4–6 This may be due to impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation, alterations in regional cerebral metabolic demand, or biochemical imbalances. Classically, after an immediate no-flow state, CBF transiently increases after return of circulation, then is severely reduced in the subsequent hours to days.7 These dynamic alterations in CBF vary by brain region and are impacted by many factors including cardiac arrest etiology, severity of primary HIBI, age, and time from cardiac arrest.5 The association between global and regional CBF and outcome is unknown.

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a noninvasive technique that can quantify CBF in the whole brain and specific regions of interest (ROIs).8,9 The time course of ASL-derived alterations in CBF after HIBI is unknown, although in neonates, abnormal ASL normalizes between weeks 1 and 2.10,11 Our objective was to determine the association between CBF measured by ASL MRI within 1 week of pediatric cardiac arrest and neurologic outcome. We hypothesized that CBF would be greater in the whole brain and in individual ROIs in children with unfavorable compared to favorable outcome.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective observational study between June 2005 and December 2019. Patients ≤18 years who experienced in- or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, received post-cardiac arrest care in the PICU, and had a clinically obtained brain MRI on a 3T scanner that included ASL imaging within 7 days of their arrest were included. Patients were included if they received any duration of CPR. If the arrest occurred in the out of hospital setting, patients were included independent of whether ROSC was obtained prior to arrival of emergency medical personnel or admission to the emergency department. We excluded patients with concomitant brain injury from a non-HIBI etiology, baseline Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) of 5 or evidence of severe brain atrophy or sequela of prior injury on MRI, and if technical issues precluded ASL analysis. Abstracted data included patient demographics, cardiac arrest characteristics, and post-cardiac arrest care. Post-cardiac arrest care was determined by the clinical team and guided by an institutional pathway.12 Patients were intubated and sedated for MRI scans. The study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent.

ASL acquisition and processing

Pulsed ASL perfusion MRI performed on a 3T Siemens scanner [Erlangen, Germany] was a standard clinical sequence for all patients. Sixteen patients had ASL acquired with a 3D pulsed ASL protocol with 700ms bolus time and 1990ms inversion time. Thirty-two patients were acquired with a 2D pulsed ASL protocol with 700ms bolus time and 1800ms inversion time. Motion correction by rigid registration aligned ASL images to first image volume using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM, University College London, UK). We used 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE (Magnetization Prepared RApid Gradient Echo) images for anatomical co-registration. We generated regional CBF maps from ASL data and manually outlined 13 regions of interest (ROIs) including right and left frontal, parietal, and temporal cortex, right and left caudate, putamen, and thalamus, and the brainstem using ROIEditor (www.mristudio.org; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD).9 ROIs were drawn on the same three consecutive axial slices at consistent anatomical locations across patients. Averaged regional CBF was calculated for the whole brain and each ROI. Given the expected homogenous nature of postarrest HIBI, right and left regions were averaged to yield 7 pre-specified regions for analysis.

Outcome measure

The primary outcome was unfavorable neurologic status based on change in PCPC score between pre-arrest and hospital discharge.13–15 PCPC is a 6-point scale of global neurologic function: (1) normal; (2) mild disability; (3) moderate disability; (4) severe disability; (5) coma or vegetative state; (6) death. Pre-arrest and hospital discharge PCPC scores were retrospectively assigned by 2 trained nurse raters via medical record review. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Unfavorable outcome was change in PCPC ≥1 from pre-arrest PCPC that resulted in hospital discharge PCPC of 3–6. Favorable outcome was hospital discharge PCPC 1–2 or no change from pre-arrest PCPC. PCPC raters were blinded to MRI data.

Statistical analysis

We report descriptive statistics as median with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. We used Wilcoxon rank sum, and χ2 and Fisher exact tests to evaluate associations between continuous and categorical variables, respectively, and outcome groups (unfavorable versus favorable). We performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression to assess the relationship between ASL-derived CBF in whole brain and ROIs and unfavorable outcome. CBF values were log-transformed to improve normality. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, and time from cardiac arrest to MRI. We performed sensitivity analyses excluding patients whose pre-arrest PCPC was >2 to account for potential changes in baseline CBF in children with chronic brain injury and patients who were ultimately declared brain dead since refractory intracranial hypertension from severe HIBI-related cerebral edema may impact CBF, and after defining unfavorable outcome as a change in PCPC ≥1 from pre-arrest PCPC that resulted in hospital discharge PCPC of 4–6.

Results

Eighty-six patients had a 3T brain MRI obtained for clinical indications within 7 days of cardiac arrest and 74 of those patients had ASL imaging (Supplementary Figure 1). Patients were excluded when ASL was not analyzable due to suboptimal brain coverage or artifact (n=14), presence of concomitant brain injury from a non-HIBI etiology (n=9), or severe pre-existing severe neurologic injury with a baseline PCPC of 5 or MRI evidence of pre-existing severe brain atrophy or injury (n=3). Thus, 48 patients were included in analyses (Table 1).

Table 1 –

Patient demographics and cardiac arrest characteristics by outcome

| Total | Favorable | Unfavorable | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | N=48 | N=15 | N=33 | |

| Age (median [IQR]) | 2.8 [0.9–8.8] | 1.2 [0.8–5.5] | 3.2 [1.2–10.0] | 0.097 |

| Male sex | 31 (65%) | 7 (47%) | 24 (73%) | 0.080 |

| Past medical history | ||||

| None | 25 (52%) | 7 (47%) | 18 (55%) | 0.76 |

| Prematurity | 8 (17%) | 3 (20%) | 5 (15%) | 0.69 |

| Chronic lung disease | 9 (19%) | 4 (27%) | 5 (15%) | 0.43 |

| Congenital heart disease | 4 (8%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 1.00 |

| Cancer | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1.00 |

| Epilepsy | 5 (10%) | 2 (13%) | 3 (9%) | 0.64 |

| Pre-arrest PCPC | 0.044 | |||

| 1 | 32 (67%) | 11 (73%) | 21 (64%) | |

| 2 | 7 (15%) | - | 7 (21%) | |

| 3 | 3 (6%) | - | 3 (9%) | |

| 4 | 6 (12%) | 4 (27%) | 2 (6%) | |

| Arrest location | 0.69 | |||

| IHCA | 8 (17%) | 3 (20%) | 5 (15%) | |

| OHCA | 40 (83%) | 12 (80%) | 28 (85%) | |

| Cause of arrest | 0.80 | |||

| ALTE/SIDS | 4 (8%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (9%) | |

| Drowning | 10 (21%) | 2 (13%) | 8 (24%) | |

| Respiratory | 19 (40%) | 7 (47%) | 12 (36%) | |

| Arrhythmia | 3 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (6%) | |

| Hypotension/Shock/Sepsis | 3 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (6%) | |

| Trauma | 6 (12%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (15%) | |

| Seizures | 3 (6%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (3%) | |

| CPR duration (n=39) | 10.0 [3.0–27.0] | 2.0 [2.0–3.0] | 22.0 [10.0–30.0] | <0.001 |

| Epinephrine doses (n=46) | 1.0 [0.0–3.0] | 0.0 [0.0–0.0] | 2.0 [0.0–3.0] | <0.001 |

| Initial rhythm | 0.33 | |||

| PEA/asystole | 18 (38%) | 3 (20%) | 15 (45%) | |

| Bradycardia | 9 (19%) | 4 (27%) | 5 (15%) | |

| Ventricular Fibrillation | 4 (8%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (9%) | |

| Unknown/Not Documented | 17 (35%) | 7 (47%) | 10 (30%) | |

| Initial pH (n=39) | 7.1 [6.9–7.3] | 7.3 [7.2–7.4] | 7.0 [6.8–7.1] | 0.004 |

| Initial lactate (n=23) | 5.0 [3.2–9.6] | 3.3 [2.1–4.2] | 7.5 [4.0–9.8] | 0.057 |

| Hospital discharge PCPC | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 7 (15%) | 7 (47%) | - | |

| 2 | 4 (8%) | 4 (27%) | - | |

| 3 | 5 (10%) | - | 5 (15%) | |

| 4 | 16 (33%) | 4 (27%) | 12 (36%) | |

| 5 | 6 (12%) | 6 (18%) | ||

| 6 | 10 (21%) | 10 (30%) |

Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IHCA: in hospital cardiac arrest; OHCA- out of hospital cardiac arrest; ALTE/SIDS: apparent life-threatening event/sudden infant death syndrome; PEA – pulseless electrical activity; PCPC: pediatric cerebral performance category score

Thirty-three (69%) patients had an unfavorable and 15 (31%) had a favorable outcome. Of those with an unfavorable outcome, 10 (30%) died prior to hospital discharge from either brain death (3/10, 30%) or withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies due to poor neurologic prognosis (7/10, 70%). Time from cardiac arrest to MRI was 4 [IQR 3,5] days and did not differ between outcome groups (unfavorable 4 [3,5] vs. favorable 3 [1,5] days, p=0.39). All patients were normothermic at time of MRI. One patient had previously received targeted temperature management to 33°C.

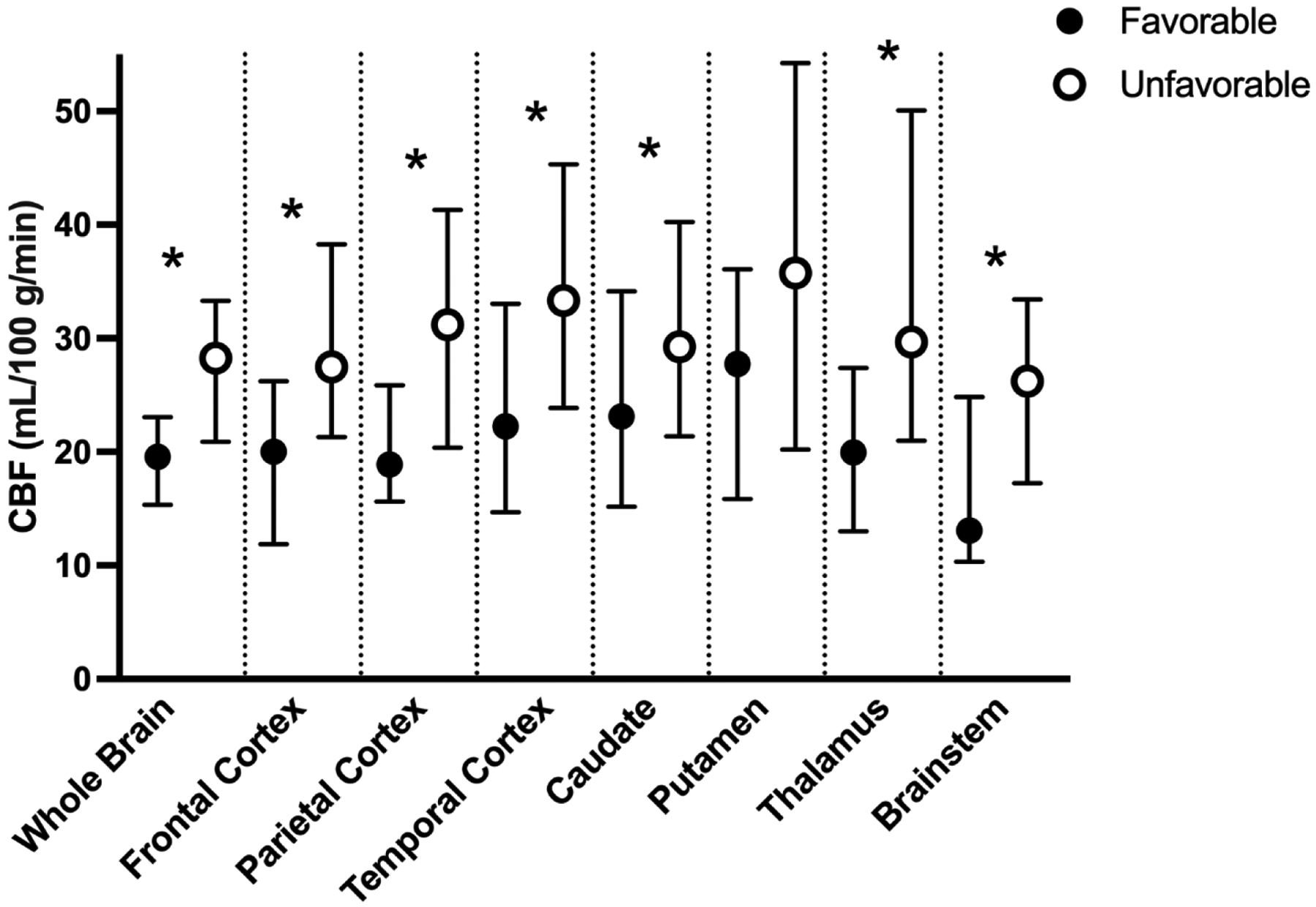

Patients with an unfavorable outcome had greater CBF in the whole brain and all ROIs except the putamen compared to patients with a favorable outcome (Figures 1 and 2). This association persisted in sensitivity analyses excluding patients who had pre-arrest PCPC scores >2 and those ultimately declared brain dead, and after defining unfavorable outcome as a change in PCPC ≥1 from pre-arrest PCPC that resulted in hospital discharge PCPC of 4–6. (Supplementary Table 1). Increased whole brain CBF was associated with greater odds of unfavorable outcome in both unadjusted analyses (Figure 3). This association was also observed in individual brain regions and after excluding patients with pre-arrest PCPC scores >2 and those ultimately declared brain dead, and after defining unfavorable outcome as a change in PCPC ≥1 from pre-arrest PCPC that resulted in hospital discharge PCPC of 3–6 (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1:

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) maps in a representative patient with a favorable (top) and an unfavorable (bottom) outcome. Brighter colors indicate higher CBF. In this example, the patient with an unfavorable outcome, has increased CBF in both the cortex and deeper brain structures compared to the patient with a favorable outcome. CBF was measured in milliliters of blood per minute per 100g brain tissue (ml/100g/min). rCBF: regional cerebral blood flow.

Figure 2:

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) in patients with favorable (black) and unfavorable (white) outcomes in the whole brain and bilateral regions of interest (ROIs). CBF is measured in mL/100g of brain tissue/minute (ml/100g/min) and plotted as medians with IQRs. * p<0.05.

Figure 3:

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for unfavorable outcome. Odds ratios represent “per 1 log increase” of each variable.

Discussion

In this single center retrospective observational study, CBF measured 3–5 days after cardiac arrest using ASL MRI was greater for patients with unfavorable compared to favorable neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. CBF was independently associated with unfavorable outcome after adjusting for patient age, sex, and time between cardiac arrest and MRI. This relationship persisted when excluding children with chronic brain injury, those who progressed to brain death, and after using a more liberal definition of unfavorable outcome.

Smaller studies in adults and children have demonstrated an association between greater CBF in patients with severe HIBI after cardiac arrest and poor outcomes, suggesting CBF may be a biomarker of brain injury severity.16–18 In one pediatric study of 14 patients imaged six days after cardiac arrest, brain regions with greater CBF had concomitant reduced apparent diffusion coefficient indicative of ischemia and cytotoxic edema.18 If CBF is increased in areas of ischemic injury, it is unclear whether this is an appropriate compensatory physiologic response to improve perfusion to injured tissue or a maladaptive response due to impaired cerebrovascular autoreactivity resulting in deleterious luxury perfusion that could contribute to secondary brain injury.

Greater CBF in injured brain tissue could also be in response to a higher cerebral metabolic rate, mitochondrial dysfunction, or increased dependance on oxidative phosphorylation in injured brain tissue.1,18–20 Future investigations, potentially using advanced neuromonitoring and neuroimaging technologies like positron emission tomography or optical imaging, are necessary to delineate whether the increased CBF is adaptive or maladaptive.21,22 Consideration of potential therapeutic approaches depends on more thorough understanding of these pathophysiologic processes.

Several factors could have impacted our CBF measurements. Patients were intubated and sedated for MRI scans. Sedative agents may differentially impact CBF depending on HIBI severity. Temperature and CO2 levels may inadvertently deviate from their baseline during transport or MRI scanning which could alter CBF. However, these effects are mild compared to the large magnitude CBF changes we observed as result of the HIBI itself. CBF is age-dependent, and while we controlled for age in our multivariable model, we had insufficient patients to examine individual age groups.23 Future studies should also account for arrest etiology as patterns of dysregulated CBF may differ for asphyxia compared to cardiac causes of arrest.24,25 ASL has been a standard sequence for post-cardiac arrest patients at our institution since 2008, however, in some situations, it was excluded at the discretion of the neuroradiologist. ASL is not routinely used by clinicians to predict neurologic outcome, unlike other MRI sequence such as diffusion weighted imaging. We log-transformed CBF values to decrease the skewness of the distribution for analyses in this study. The association of log-transformed CBF should be consistent with crude values, however, they are not the numbers available to clinicians for clinical care. The wide confidence intervals in our data are likely predominantly the result of our low number of patients. Future studies should utilize high-resolution pseudo-continuous ASL, which improves signal-to-noise ratio of CBF measurements in small anatomic structures.26

Conclusions

CBF derived from ASL MRI 3–5 days after pediatric cardiac arrest was greater in patients with unfavorable compared to favorable outcomes. Future studies should focus on understanding the pathophysiology of increased CBF after HIBI and whether it is amenable to therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Consort diagram.

Financial support:

K23NS116120, R01MH092535, and R01EB031284

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Kirschen received NIH support to his institution. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

Declarations of Interest

Dr. Kirschen received NIH support to his institution. The remaining authors have no declarations of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation 2008;118:2452–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topjian AA, de Caen A, Wainwright MS, et al. Pediatric Post-Cardiac Arrest Care: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019:CIR0000000000000697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topjian AA, Raymond TT, Atkins D, et al. Part 4: Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2020;142:S469–S523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buunk G, van der Hoeven JG, Meinders AE. Cerebral blood flow after cardiac arrest. Neth J Med 2000;57:106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iordanova B, Li L, Clark RSB, Manole MD. Alterations in Cerebral Blood Flow after Resuscitation from Cardiac Arrest. Front Pediatr 2017;5:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekhon MS, Ainslie PN, Griesdale DE. Clinical pathophysiology of hypoxic ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest: a “two-hit” model. Crit Care 2017;21:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safar P Cerebral resuscitation after cardiac arrest: research initiatives and future directions. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:324–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Licht DJ, Jahng GH, et al. Pediatric perfusion imaging using pulsed arterial spin labeling. J Magn Reson Imaging 2003;18:404–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 2015;73:102–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proisy M, Corouge I, Legouhy A, et al. Changes in brain perfusion in successive arterial spin labeling MRI scans in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. NeuroImage Clinical 2019;24:101939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Li J, Yin X, Zhou H, Zheng Y, Liu H. Cerebral hemodynamics of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy neonates at different ages detected by arterial spin labeling imaging. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2022;81:271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler JC, Wolfe HA, Xiao R, et al. Deployment of a Clinical Pathway to Improve Postcardiac Arrest Care: A Before-After Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020;21:e898–e907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiser DH, Long N, Roberson PK, Hefley G, Zolten K, Brodie-Fowler M. Relationship of pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scores at pediatric intensive care unit discharge with outcome measures collected at hospital discharge and 1- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Crit Care Med 2000;28:2616–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr 1992;121:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topjian AA, Scholefield BR, Pinto NP, et al. P-COSCA (Pediatric Core Outcome Set for Cardiac Arrest) in Children: An Advisory Statement From the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation 2020;142:e246–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollock JM, Whitlow CT, Deibler AR, et al. Anoxic injury-associated cerebral hyperperfusion identified with arterial spin-labeled MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarnum H, Knutsson L, Rundgren M, et al. Diffusion and perfusion MRI of the brain in comatose patients treated with mild hypothermia after cardiac arrest: a prospective observational study. Resuscitation 2009;80:425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manchester LC, Lee V, Schmithorst V, Kochanek PM, Panigrahy A, Fink EL. Global and Regional Derangements of Cerebral Blood Flow and Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging after Pediatric Cardiac Arrest. J Pediatr 2016;169:28–35 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiberg S, Stride N, Bro-Jeppesen J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in adults after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020;9:S138–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choudhary RC, Shoaib M, Sohnen S, et al. Pharmacological Approach for Neuroprotection After Cardiac Arrest-A Narrative Review of Current Therapies and Future Neuroprotective Cocktail. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:636651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko TS, Mavroudis CD, Baker WB, et al. Non-invasive optical neuromonitoring of the temperature-dependence of cerebral oxygen metabolism during deep hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in neonatal swine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020;40:187–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko TS, Mavroudis CD, Benson EJ, et al. Correlation of Cerebral Microdialysis with Non-Invasive Diffuse Optical Cerebral Hemodynamic Monitoring during Deep Hypothermic Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Metabolites 2022;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu C, Honarmand AR, Schnell S, et al. Age-Related Changes of Normal Cerebral and Cardiac Blood Flow in Children and Adults Aged 7 Months to 61 Years. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drabek T, Foley LM, Janata A, et al. Global and regional differences in cerebral blood flow after asphyxial versus ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in rats using ASL-MRI. Resuscitation 2014;85:964–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manole MD, Foley LM, Hitchens TK, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of regional cerebral blood flow after asphyxial cardiac arrest in immature rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009;29:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Q, Ouyang M, Detre J, et al. Infant brain regional cerebral blood flow increases supporting emergence of the default-mode network. Elife 2023;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Consort diagram.