Abstract

All psychological research on morality relies on definitions of morality. Yet the various definitions often go unstated. When unstated definitions diverge, theoretical disagreements become intractable, as theories that purport to explain “morality” actually talk about very different things. This article argues for the importance of defining morality and considers four common ways of doing so: The linguistic, the functionalist, the evaluating, and the normative. Each has encountered difficulties. To surmount those difficulties, I propose a technical, psychological, empirical, and distinctive definition of morality: obligatory concerns with others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice, as well as the reasoning, judgment, emotions, and actions that spring from those concerns. By articulating workable definitions of morality, psychologists can communicate more clearly across paradigms, separate definitional from empirical disagreements, and jointly advance the field of moral psychology.

Keywords: moral psychology, moral philosophy, definitions, meta-theory

“I’ll tell you what real love is,” Mel said. “I mean, I’ll give you a good example. And then you can draw your own conclusions.” He poured more gin into his glass. He added an ice cube and a sliver of lime. We waited and sipped our drinks. Laura and I touched knees again. I put a hand on her warm thigh and left it there.

“What do any of us really know about love?” Mel said.

Raymond Carver (1981), “What we talk about when we talk about love,” p. 176

In Raymond Carver’s (1981) short story “What we talk about when we talk about love,” two couples hold a conversation about love that grows increasingly tense and drunken. The four protagonists try to talk about the same thing but lack a shared notion of love. The last word goes to the loudest of the party—the cardiologist Mel—before the conversation awkwardly dies. For anyone who has studied moral psychology, it is easy to imagine a similar story about four psychologists discussing morality. In the latter story, each psychologist would make claims based on their own, unstated definition of morality. Each protagonist, and every reader of the story, would be unsure what the other three were talking about when they said “morality.” This, I will argue, is the predicament of today’s science of moral psychology.

Seeking a way out of this predicament, I will engage the four protagonists, each representing a contemporary approach to defining morality (see e.g., Machery, 2018; Stich, 2018). One protagonist defines morality as whatever people call “moral” (the linguistic approach); a second defines morality in terms of its social function (the functionalist); a third defines morality as the collection of right actions (the evaluating); and a fourth defines morality to comprise all judgments about right and wrong (the normative). These four ways of defining morality are not themselves theories of morality, although they undergird such theories. They are different ways of demarking the domain that psychological theories of morality seek to explain, just as definitions of planets demark the domain of planetary science.

In this article, I will first argue that it is both possible and useful for psychologists to define morality, countering the arguments of some scholars (e.g., Greene, 2007; Stich, 2018; Wynn & Bloom, 2014). Without definitions, disagreements about morality will stalemate; with definitions, we can research and communicate more clearly. I will then discuss how, despite their intuitive appeal, each of the four approaches to defining morality—the linguistic, functionalist, evaluating, and normative—runs into difficulties.

The last part of the article will seek a definition of morality that achieves its goals without the corresponding difficulties. In brief, I propose to define morality as obligatory concerns with others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice, as well as the reasoning, judgment, emotions, and actions that spring from those concerns (Dahl et al., 2018; Dahl & Killen, 2018a; Turiel, 1983; Turiel & Dahl, 2019).1 This definition is technical in that it achieves considerable, but not complete, overlap with ordinary language use; it is psychological in that it captures psychological characteristics that most people in all communities have; it is empirical in that it does not rely on researchers’ ideas about morally good and bad behaviors; and it is distinctive in that it distinguishes moral judgments from other normative judgments. I will not claim that the proposed definition is the only technical, psychological, empirical, and distinctive definition of morality we might adopt. I claim only that the proposed definition avoids some common problems and has proven useful for empirical research.

Do We Need to Define Morality to Study it?

Two transformational decades of psychological research on morality have intensified the need for definitions (Kohlberg, 1971; Turiel, 1983, 2010). The 2000s saw seminal publications on moral reasoning, judgments, emotions, and actions across the lifespan and in diverse cultural groups (e.g., Blake et al., 2015; Bloom, 2013; Greene et al., 2001; Haidt, 2001; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Hamlin et al., 2007). In the intervening years, scholars built on these advances in thousands of publications (see Cohen Priva & Austerweil, 2015; Ellemers et al., 2019; Gray & Graham, 2018; Malle, 2021; Thompson, 2012). Adding to the empirical wealth, the vast psychological literature on morality overlaps—often seamlessly—with other psychological literatures on prosociality and social norms (e.g., Legros & Cislaghi, 2020; Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2016).

For all its empirical advances, psychological research on morality has lacked theoretical integration. Some scholars have argued that morality is innate, while others have argued that morality first emerges around age three (Bloom, 2013; Carpendale et al., 2013; Hamlin, 2013; Tomasello, 2018). Many developmental psychologists have proposed that moral judgments spring from reasoning; many cognitive and social psychologists have countered that most moral judgments spring from affective intuitions and not reasoning (e.g., Greene, 2013; Haidt, 2012; Turiel, 2018). And some scholars have proposed that each cultural-historical community has its own morality, challenging the idea of a universal moral sense (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Machery, 2018; Shweder et al., 1997).

A major impediment to integration has been that moral psychologists have disagreed sharply about whether and how to define morality (Malle, 2021; Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012). Those who claim that morality is innate rely on different definitions of morality than those who claim that morality emerges by age three, even though the differences between their definitions mostly go unacknowledged. The same holds true for debates about the roles of emotion in morality and for debates about cultural variability. So when two psychological theories make opposing claims about “morality,” it is hard to know if they are speaking about the same thing.

The hope behind this paper is that clarity on definitions will help our field capitalize on its empirical advances and achieve greater theoretical integration. This does not mean that all scientific disagreements about morality come down to differing definitions: To know when morality emerges, we still need empirical research about what children can and cannot do at a given age. But we cannot resolve any empirical disagreements about morality without knowing what the protagonists of those disagreements mean when they write “morality.”

The Problems of Lacking Definitions

To see what happens when we lack definitions, consider the debate about whether obedience to authorities is a moral concern (see e.g., Haidt & Graham, 2007; Turiel, 2015). Is it a moral matter to follow the commands of a god, parent, or military commander? Or does that fall outside the moral and into a non-moral domain, such as a domain of social conventions? The answer depends on what the questioner means by “moral.” If “moral” means “relevant to judgments of right and wrong,” virtually all theorists would say “yes” (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Smetana, 2013; Turiel, 2015). If “moral” means “whatever people call ‘moral’” the answer will vary from person to person, and occasion to occasion, since people use “moral” in a variety of ways—and some languages have no equivalent term (Simpson & Weiner, 1989; Wierzbicka, 2007). If “moral” means “concerns with welfare, rights, justice, and fairness” (Turiel, 1983), concerns with authority commands would fall outside the moral domain. And if, as they often do, two debaters unknowingly operate with different definitions of “morality,” the debate verges on the meaningless.

Similar confusions have arisen in debates about whether all moral judgments derive from perceived harm. In their Theory of Dyadic Morality, Gray and colleagues (2012) proposed that “all moral transgressions are fundamentally understood as agency plus experienced suffering—that is, interpersonal harm” (p. 101). According to this theory, there are no “harmless wrongs” (Gray et al., 2014), and perceptions of harm prompt judgments of wrongness.

Critics of Gray’s Theory of Dyadic Morality have countered with examples that, in their view, separate morality from harm: People can judge harmless actions as immoral and harmful actions as moral (Graham & Iyer, 2012; Royzman & Borislow, 2022). In response to such critics, Gray has broadened the definition of harm to include variety consequences (e.g., Schein & Gray, 2018b). The harm in question is not just bodily harm, but virtually any actual or potential negative consequence—to a soul, a group, a society, an animal, the environment, or even oneself. With this broader notion of harm, the Theory of Dyadic Morality can defend itself against examples of moral wrongs that, while harmless in a narrow sense, are harmful in the broader sense.

But ambiguity still surrounds the word “moral.” Let us say a critic wants to challenge the Theory of Dyadic Morality by identifying harmless moral violations. Such a counterexample would have to belong to the intersection of two sets: the set of harmless actions and the set of moral violations. Schein and Gray’s (2018b) redefinition of harm sharpens the boundary of the set of harmless actions. But we also need to sharpen the boundary of the set of moral violations. To know what would count as a counter-example, we need to know what counts as a “moral” example. We need a definition of morality.

In some places, Gray and colleagues have written as if all judgments about right and wrong are “moral” judgments (Gray et al., 2014; Schein & Gray, 2018a). In a chapter entitled: “Moralization: How acts become wrong,” Schein and Gray’s (2018a) begin by asking “What makes an act wrong?” (p. 363). The answer, they suggest, “lie with perceptions of harm.” In other places, the theory distinguishes moral judgments from other judgments of right and wrong, as when Gray et al. (2012) wrote that the “presence or absence of harm also distinguishes moral transgressions from conventional transgressions” (p. 109; also Schein & Gray, 2018b, p. 36). This leaves us with two potential definitions of morality in the Theory of Dyadic Morality. Moral judgments are either all of normative judgments or a specific subset of normative judgments.

The choice between these two definitions determines the kind of evidence needed to evaluate the Theory of Dyadic Morality. The claim that all right-wrong judgments spring from perceptions of harm is a much broader claim, and requires more evidence, than the claim that some (moral) subset of right-wrong judgments springs from perceptions of harm. Moreover, if the theory took the latter path, it would need to identify that subset of normative judgments without reference to perceived harm. Otherwise, the core claims of the theory become tautological: If, say, the theory defined moral violations as “violations perceived as harmful,” it would have ruled out the possibility of “harmless” moral violations a priori (Smedslund, 1991).

Resolving the debates about the Theory of Dyadic Morality requires a definition of morality. Equipped with a definition of morality, we can test the theory’s empirical hypothesis that all moral judgments are rooted in perceptions of dyadic harm. Here too, empirical claims and questions are conditional on a definition of morality.

Why Defining Morality is so Hard

All scientific inquiries depend on definitions. An inquiry begins with a question. How many planets are there? When do moral judgments emerge? Are all moral judgments based on perceptions of harm? The answer to each empirical question depends on the meaning of its words. Astronomers who want to count the number of planets in our solar system first need to decide what counts as a planet (Metzger et al., 2022). Definition in hand, the astronomer can then peer through their telescopes and decide whether Pluto, the Moon, and other heavenly bodies count as planets. (It is not strictly necessary that all astronomers use the same definition of planets, as long as each astronomer is clear on what they mean when they count their planets.) Before discovering that the structure of DNA had a double-helix structure, biologists first had to define and identify DNA (Wade, 2004). And so on.

Among scientific concepts, morality has proven unusually vexing to define. One cause for vexation is the myriad of meanings that “moral” and “morality” have in ordinary language (Graham et al., 2011; Malle, 2021). In the Oxford English Dictionary, “moral” has over twenty meanings, ranging from considerations about right, wrong, good, or bad to descriptions of practical certainty (“moral certainty,” Simpson & Weiner, 1989). Fortunately, everyday polysemy is not scientifically fatal. The many meanings of the word “cell” did not stop biologists from arriving at a workable definition—one that differentiates bodily cells from battery cells and prison cells.

A related complication is that research participants, whose morality psychologists study, have their own uses of “moral” and “morality.” Participants’ word usage do not generally align with psychologists’ word usage. (Biological cells, by contrast, do not mind their homonymy with battery cells.) To avoid such misalignment in word use, some researchers have proposed to rely on what “ordinary people” call moral (Greene, 2007). As we will see later, this solution—despite its appeal—brings its own trouble.

What is worse, “moral” can take on both evaluative and descriptive meanings (Gert & Gert, 2017; Machery & Stich, 2022). In its evaluative sense, “moral” means “morally good/right” and contrasts with “immoral.” A person may call the execution of a murderer a “moral action” in the evaluative sense if they positively evaluate the use of capital punishment. In its descriptive sense, “moral” means “evoking views about what is morally good or bad” and contrasts with “non-moral” or “amoral.” A person may call legal executions a “moral issue” in a descriptive sense if they mean to describe capital punishment as a topic about which people hold strong views about the rights and wrongs of murderers. “Moral” also has a descriptive meaning in the phrase “moral psychologists.” We label someone a moral psychologist because they study moral psychology—not because they are morally better than other psychologists (see Schwitzgebel & Rust, 2014). When researchers call a phenomenon “moral,” a reader may wonder whether they use “moral” in an evaluative or descriptive sense.

Such difficulties have led to pessimism about definitions. Many psychologists and philosophers have argued that defining “morality” is either unfeasible or counterproductive in psychological research (Greene, 2007; Stich, 2018; Wynn & Bloom, 2014). Perhaps sharing the same pessimism, other psychologists have tacitly avoided defining morality in their writings. Let us consider arguments against defining morality.

Arguments Against Defining Morality

One common argument is that we cannot define morality until philosophers and psychologists have reached a consensus on how to define it. Wynn and Bloom (2014) wrote that “starting with a definition is ill advised. After all, there is no agreed-upon definition of morality by moral philosophers […], and psychologists sharply disagree about what is and is not moral” (p. 436). They argue that only a definition of morality widely shared by philosophers or psychologists would do; until we reach that agreement, morality is better left undefined.

True, philosophers and psychologists have no consensual definition of morality (Gert & Gert, 2017; Stich, 2018). But the lack of a shared definition is not usually a reason against explaining what we mean. More often, the lack of a shared definition is a reason for providing one’s own definition, to help readers understand us. Clear communication demands specification, especially when our words has several possible meanings. If I am flying from Paris to the London that lies in the Canadian province of Ontario, I should say which London I mean. If I am flying from Paris to the New York City that lies in the U.S. state of New York, such specification is superfluous. And if I am proposing to explain morality, I should say which morality I mean.

The definition we provide does not need to be the definitive definition. There is no shame in settling for an inquiry-specific or technical definition. Philosophers—experts in defining terms—routinely provide definitions that their colleagues do not share. In his classic book about conventions, Lewis (1969) wrote: “If the reader disagrees [with his definition of conventions], I can only remind him that I did not undertake to analyze anyone’s concept of convention but mine” (p. 46). Even if his definition differs from the definitions of others, Lewis views his philosophical investigation of conventions is a worthwhile one. For another philosophical project, another definition of conventions might be better. Nutritionist and botanists have different definitions of fruits. For nutritionists, who study healthy eating, tomatoes are vegetables; for botanists, who study the biology of plants, tomatoes are fruits (Petruzzello, 2016). Each discipline lives happily with its own definition, tailored to its purpose, and with the knowledge that others define fruits differently. These are reassuring precedents for moral psychologists. We can safely adopt a definition of morality in our own work without requiring that our definition be shared by everyone else.

Others have contended psychologists constrict their vision if they define morality. Greene (2007) wrote that “[f]or empiricists, rigorously defining morality is a distant goal, not a prerequisite. If anything, I believe that defining morality at this point is more of a hindrance than a help, as it may artificially narrow the scope of inquiry” (p. 1). Greene’s worry is that, if we define morality, we might miss out on important phenomena by defining them out of our inquiry. But if having a definition might render the inquiry too narrow, lacking a definition might render the inquiry too broad. For without definitions, we cannot separate the phenomena that our theory seeks to explain from the phenomena that the theory does not seek to explain. When we develop a theory of morality, do we hope to explain how people judge violations of dress codes, of drink recipes, or of the manual that came with our new coffee machine? Our answers to these questions reveal the perimeter of our definition and shape the choice of stimuli for our studies.

Furthermore, the scope of our inquiry is not chained to a single, defined term. A researcher who defines morality can still choose to study things other than morality. Researchers in the Social Domain Tradition have used a fairly narrow definition of morality (issues of welfare, rights, justice, and fairness), but this has not prevented them from studying other normative issues, such as social conventions (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 2015).

The sheer formidability of the task might be a further reason why psychologists leave morality undefined (Stanford, 2018; Stich, 2018). Spanning several millennia, debates about the nature of morality have enlisted enough intellectual giants to intimidate us into silence. Who are we to enter a fray that already has Plato and Kant in it? Luckily, we do not need to shoot for the ultimate definition of the One True Morality, forever immune to revision. Any researcher is free to abandon their old definitions if new ones turn out more useful—and scientists often do (Kuhn, 1962; Lazarus, 2001; Mukherjee, 2016). We need a car today even if we can buy a safer and more self-driving car next year. And we need a definition today even if we will find a better definition in the future.

If a reader grants that a definition of morality would be useful—even a definition not shared by all psychologists—one empirical challenge remains. Communities seem to differ radically in their values, in what their members judge as right and wrong,2 and in their way of life (Henrich et al., 2010; Rogoff, 2003; Shweder et al., 1987; Turiel, 2002). Eating beef is wrong for Hindus but not for Muslims (Srinivasan et al., 2019). Brits must drive on the left side of the road, and Americans must drive on the right. In the United States, most Democrats say that abortion should be legal under most or all circumstances, whereas only a minority of Republicans agree (Gallup Inc., 2018). Faced with such cultural variability, can a single definition of morality really work for all communities? On closer inspection, the cultural differences in values and normative judgments coexist with profound cultural similarities. These cultural similarities make a universal definition of morality possible.

The Cultural Similarities that Make a Universal Definition of Morality Possible

In cross-cultural research, cultural differences usually get more attention than cultural similarities (Schwartz & Bardi, 2001; Turiel, 2002). Psychology has a history of characterizing some countries or continents as individualist and others as collectivist; some cultures as “loose” in their application of rules and others as tight (Gelfand, 2018; Triandis, 2001; for discussion, see Rogoff, 2003).

Our attention to cultural differences tempts us to overlook the similarities in the values, principles, and judgments of most people in all communities. Around the globe, children, adolescents, and adults think it is generally wrong to cause harm, disobey legitimate authorities or traditions, or engage in dangerous behaviors (see Turiel, 2002). Several research paradigms have revealed that communities share fundamental values and norms, even if they apply those values and norms differently to different situations.

One questionnaire that has revealed such similarities is the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ). The MFQ assesses five moral “foundations” or values: Harm, fairness, group loyalty, authority, and purity (Graham et al., 2011, 2013; Haidt & Graham, 2007). The questionnaire asks participants which considerations are relevant when they “decide whether something is right or wrong.” Participants report the relevance of 15 normative considerations—three for each foundation—such as whether “someone suffered emotionally” (harm) and whether someone “showed a lack of loyalty” (loyalty). They indicate the relevance of each consideration on a 6-point scale from 1 (“not at all relevant”) to 6 (“extremely relevant”).

The original goal of the MFQ was to “gauge individual differences in the range of concerns that people consider morally relevant” (Graham et al., 2011, p. 369). Researchers have also used the MFQ in comparisons of U.S. conservatives to U.S. liberals and other cultural comparisons (Haidt & Graham, 2007). In the United States and Turkey, politically conservative participants rated concerns with authority, loyalty, and purity as more important than politically liberal participants (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Yilmaz et al., 2016). In a cross-country comparison, Zhang and Li (2015) found that participants in China, on average, rated group loyalty, authority, and purity as more important than participants in the United States. The findings with the MFQ echo prior findings by Shweder and colleagues (1987, 1997; see also J. G. Miller et al., 2017). The latter work reported that children and adults in India placed, on average, more emphasis on concerns with community and religion, and less on individual autonomy, than children and adults in the United States.

But group differences in value ratings, while statistically significant, are smaller than we think: Graham and colleagues (2012) found that U.S. adults overestimate the size of political differences in value ratings. People in all groups are concerned with harm fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity, and the studies with the MFQ show as much. Yes, liberals give lower relevance ratings to loyalty, authority, and purity than conservatives do. But even the most extreme liberals studied by Haid and Graham (2007) rated loyalty, authority, and purity as being, on average, between 3 (“slightly relevant”) and 4 (“somewhat relevant”) on the 6-point scale. The most extreme conservatives gave average ratings between 4 and 5 (“very relevant”). To summarize: We all care about loyalty, authority, and purity—as well as harm and fairness.

Moreover, the average cultural differences in value ratings depend on the issue people are evaluating. Conservative participants give greater weight to the commands of military officers; liberals, by contrast, place greater weight than conservatives on other authorities, such as environmentalists experts or U.S. presidents from the Democratic party (Frimer et al., 2014; Turiel, 2015). These findings show that we have to be careful when we say that conservatives care more about authorities, loyalty, and purity in general. People are, after all, never making judgments based on authorities, group loyalties, or purities in general but always with respect to some specific authority, group, or purity.

Other research paradigms have yielded similar findings: People care about the same fundamental values everywhere, even if their weighting and specific implementation of those values vary. And even the weighting of values shows consistency. In one cross-cultural study with participants from over 50 countries, benevolence and universalism consistently emerged among the most important values (Schwartz & Bardi, 2001).

Humanity’s shared basic values and concerns do not guarantee agreement on all issues. In war, the loyalties and authorities of one side conflict with the loyalties and authorities of the other. People who care about fairness can nonetheless disagree about whether the current distribution of wealth is fair (Arsenio, 2015; Jost & Kay, 2010). Still, the cross-cultural similarities in basic values and concerns provide a basis for a universally applicable definition of morality. Defining morality for psychological science is not only desirable; it is also attainable.

What We Do When We Define Morality: Four Contemporary Approaches

Once we resolve to define morality, we have to decide how to go about it. Carver’s short story asks what we do when we talk about love. This section will ask what we do when we define morality. To define morality has meant different things to different psychologists. Taking divergent paths, those psychologists arrived at disparate definitions. If we reflect on what we do when we define morality in psychology, we realize that our definitions serve different ends. Some definitions serve those ends well, other definitions serve them less well. By surveying those ends, and our success in reaching them, we can make more informed choices about what to do when we define morality.

I will consider four contemporary approaches to defining morality: the linguistic, the functionalist, the evaluating, and the normative (Table 1). Each approach represents a different idea of what we do when we define morality in psychological research; each runs into its own difficulties. The four approaches to defining morality for psychological research have had multiple instantiations over the past century. Though I provide examples below, my goal is not to list all the definitions of morality proposed by psychologists, as extant papers provide excellent surveys (Graham et al., 2013; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Machery, 2018; Malle, 2021; Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012; Stich, 2018). My goal is to initiate a taxonomy of common and appealing ways of defining morality in psychology.

Table 1.

Overview of Approaches to Defining Morality

| Common approaches to definitions | Difficulty | To overcome the difficulty, a definition has to… | Proposed definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| (a) Linguistic | Capturing how people use the word “moral” | “Moral” has many uses in ordinary language | …overlap with some but not all common uses of the word “moral” (technical definition) | Morality is… |

| (b) Functionalist | Capturing morality by its function or consequences | Psychological phenomena do not have a 1:1 mapping with functions or consequences | …identify widely shared psychological phenomena (psychological definition) | … rooted in a set of obligatory concerns |

| (c) Evaluating | Capturing the set of (morally) right characteristics | An empirical science has no methods for separating right from wrong actions or traits | …that shape people’s normative judgments without committing the researchers to specific views about right and wrong actions or traits (empirical definition) | …that give rise to reasoning, judgments, emotions, and actions about right and wrong |

| (d) Normative | Capturing all considerations about right and wrong | Normative considerations comprise a heterogenous group of social and non-social considerations | …and separate moral judgments from other normative judgments. (distinctive definition) | …ways of treating others (i.e., concerns with welfare, rights, fairness, and justice). |

The discussion of the linguistic, functionalist, evaluating, and normative approaches will set the stage for an alternative approach to defining morality, one designed to avoid difficulties encountered by the four other approaches. I will instantiate this alternative approach by proposing a definition of morality. The definition I propose is not the only valid or useful definition of morality; it is merely one useful definition, better than some, possibly worse than others, and—like all definitions—a candidate for future revision.

(a). The Linguistic: Capturing How People use the Word “Moral”

One common way of defining morality in psychology, which we have already encountered, is to rely on what people call “moral” (Greene, 2007; Levine et al., 2021; Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012; Stich, 2018). I will call this the linguistic approach. Embracing a linguistic approach, Greene (2007) writes: “I and like-minded scientists choose to study decisions that ordinary people regard as involving moral judgment” (p. 1).3 Similarly, Sinnott-Armstrong and Wheatley (2012) write: “We define moral judgments to include all judgments that are intended to resemble paradigm moral judgments” (p. 356). In this approach, moral psychologists are to study anything that fits within non-scientists’ conceptions of “morality.”

Some have asserted that the linguistic approach frees psychologists from having to define morality. In their review of research on moral conviction, Skitka and colleagues (2021) write:

Rather than start with a definition of what counts as a moral concern, researchers working on moral conviction have instead asked people whether they see their position on given issues as a reflection of their personal moral beliefs and convictions. In other words, unlike most approaches that define a priori what counts as part of the moral domain, the moral conviction approach allows participants to define the degree to which their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs reflect something moral (p. 349).

But by counting as moral anything that people call “moral,” the linguistic approach is undoubtedly an approach to defining morality—even if the researchers do not put forth their own substantive definition. Via the responses of research participants, the linguistic approach offers a criterion for separating the moral from the non-moral. This separation sets the science in motion, for what falls inside the moral domain demands an explanation from moral psychologists. The linguistic approach has to hope that people’s use of the word “moral” picks out phenomena of sufficient unity to make a psychological theory possible (Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012).

The problem for the linguistic approach is that the meaning of “morality” varies enormously, both within and between persons. The same person can use the word “morality” in multiple ways: I already mentioned the twenty-plus meanings listed in the Oxford English Dictionary. All of these meanings are available to any one English speaker. This is essentially what Wittgenstein (1953) pointed out, using the example of games. In Wittgenstein’s view, we have no reason to think that any one characteristic unites board games, card games, and Olympic games—not to mention wild game (Daston, 2022). Nor have we any reason to think that any one feature unites bodily cells, battery cells, prison cells, terrorist cells, and whatever else people call “cell.” The collections of entities called “game,” “cell,” or “moral” are too heterogenous and unbounded to support interesting theories. This is why biologists do not take a linguistic approach to definitions. No biologist would commit themselves to theorizing about whatever it is that people call “cells.” Biologists theorize about cells as defined by biologists and, thanks to their technical definition, can demonstrate cellular truths like: “Cells break down sugar molecules to generate energy.”

A further complication is that people differ in their use of the word “moral.” Even two people who agree completely on what is right and what is wrong might use the word “moral” in distinctly idiosyncratic ways. The Catholic Church talks about “moral certainty” and the Islamic Republic of Iran has a “morality police.” Philosophers and laypersons also use the word “morality” in disparate ways (Graham et al., 2011; Levine et al., 2021; Machery, 2018; Stich, 2018). When Malle (2021) asked 30 people to define “morally wrong,” he got 30 answers. One person answered that “morally wrong” meant “against the will of God.” Another answered: “Deliberately causing real harm is definitely a confident morally wrong. Accidental harm is more gray, and causing no one harm isn’t morally wrong.” (Also, I doubt that people’s definitions captured every way they actually use the word “moral” or “morality” in their speech.) Interpersonal variability in word use is troublesome enough when working within one language community. It borders on intractable when we look across multiple languages and time periods (Daston, 2022; Machery, 2018; Wierzbicka, 2007).

What reason do we have for assuming that, underneath these differences, everyone has a shared notion of “morality”? And, if two people disagree about what is “moral,” which persons should moral psychologists listen to when they decide what to study? Is it enough that one person calls an issue “moral” for it to count, even if that one person is being careless or manipulative in their choice of words? The upshot: Everyday language is an unreliable guide for psychologists wanting to study morality. It seems impossible for psychologists and philosophers to concoct a definition that covers all the many uses of the word “moral” (Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012; Wittgenstein, 1953). And even if psychologists somehow devised a definition that captured every use of the word “moral”—perhaps an extremely long and ever-changing catalog of word usage—the definition would be useless for psychological science. The phenomena falling under the definition would lack the psychological unity necessary for theorizing and hypothesis testing (Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012).

Still, we should not completely abandon everyday language. A partial overlap between the scientific and ordinary usages of “morality” seems desirable. Some of the things that scientists call “moral” should also be things that other people call “moral.” It would cause needless confusion to define “morality” as, say, a component of low-level color perception. A definition for scientific purposes that partially overlaps with everyday word use, but that has a singular and well-defined meaning, is a technical definition.

Technical definitions diverge from everyday word use for a reason. In scientific discourse, clear and consistent word use is essential for progress. Technical definitions ensure that readers know which phenomena our theories and hypotheses are about. In everyday language, polysemy is generally tolerable, probably unavoidable, and sometimes desirable (Vicente & Falkum, 2017). We deploy the multiple meanings of words to make puns, obfuscate when we want to obfuscate, and insinuate when we want to insinuate. At its best, science seeks none of these. In science, polysemy produces imprecision.

Science has a history of technical definitions that partially overlaps everyday usage. From Antiquity until the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th century, most people thought whales were fish (Romero, 2012). 4 As long as “fish” meant “anything swimming in water,” whales fit the definition. Eventually, modern scientists like Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) stopped counting whales as fish. They realized that whales—unlike most swimming creatures—are mammals who breathe with lungs and produce milk. Non-scientists, though, persisted in pooling whales and fishes. In Moby Dick, Herman Melville (1851)—the most famous whale aficionado of the 19th century—had the narrator Ishmael define the whale as “a spouting fish with a horizontal tail” (p. 111). Ishmael concedes that Linnaeus separated whales from fish, only to deem Linnaeus’s reasons “altogether insufficient” (p. 111). The first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, published around 1900, said that in “popular language,” a fish is “any animal living exclusively in the water“ (Murray & Bradley, 1900, p. 254).5 It added: “In modern scientific language (to which popular usage now tends to approximate),” the word “fish” is “restricted to a class of vertebrate animals provided with gills throughout life, and cold-blooded” (p. 254).

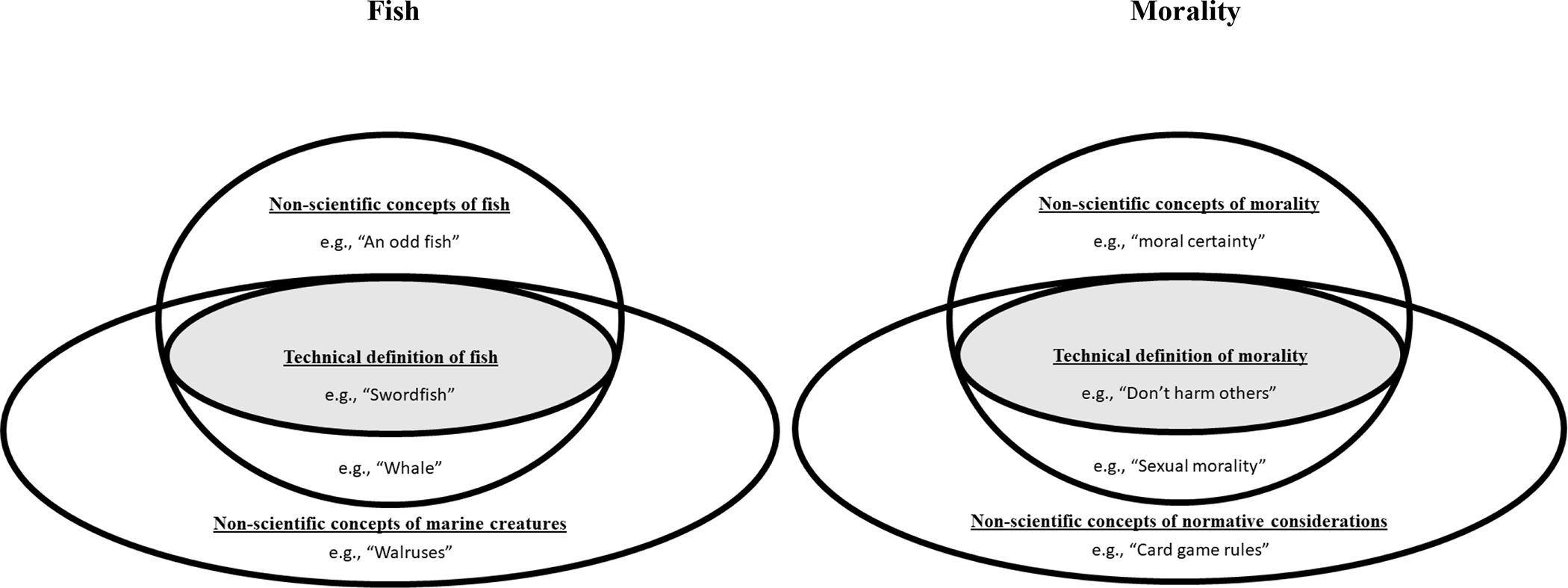

The separation of whales and fishes is an example of how scientists let technical usage overlap partially with ordinary usage (Figure 1). Even after Linnaeus put the whales with the mammals, most creatures that ordinary people called “fish”—shark, swordfish, herring—continued to meet the scientific definition of “fish.” But it was scientifically convenient to split the scientific notion of fish from certain creatures that ordinary people called fish, like whales and shellfish. It was also convenient to distinguish the scientific notion of fish from various other uses of “fish.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “fish” can also mean “a turtle,” “a dollar,” “a torpedo,” and—”unceremoniously”—a person, as in: “He was an odd fish” (Simpson & Weiner, 1989). Biologists eventually convinced people to stop calling whales “fish.” Yet this history began, and continues, with partial overlap between scientific and ordinary usage.

Figure 1: Representation of Relation between Non-Scientific Concepts and Technical Definitions for “Fish” and “Morality ”.

Note. The quoted phrases are examples of what would fit into each segment of the diagram. The particular visualization of a technical definition of morality illustrates the definition I propose in this paper. For other technical definitions, the everyday phrases included and excluded in the definition will be different.

Following the example of marine biologists, moral psychologists could be looking for a technical definition of morality: one that sacrifices a complete overlap with everyday usage for scientific clarity. Indeed, many philosophers rely on technical definitions of morality. In doing so, they are not demanding that their technical usage capture or replace ordinary usage. In explaining his definition of “moral” values, Scanlon (1998) writes that “what seems to me most important is to recognize the distinctness of the various values I have discussed […] Once the nature and motivational basis of these values is recognized, it does not matter greatly how broadly or narrowly the label ‘moral’ is applied” (Scanlon, 1998, p. 176; for similar arguments, see Dahl, 2014; D. Lewis, 1969). Scanlon’s main goal here is not to force others to use his definition: he does not seek to monopolize the term “morality.” His goal—one that all scholars have—was to communicate his views clearly, and a technical definition of morality did the trick.

How much overlap with everyday usage to seek—how large the gray section in Figure 1 should be—depends on at least two things. First, how much overlap to seek depends on the unity of the entities picked out by ordinary word use. If more of the phenomena identified by the ordinary usage shares basic features, they allow more theorizing. Second, it on the scientific aims behind the technical definition. Scientific theorizing about fish became easier, and richer, when theories of fish no longer had to account for whales (Sinnott-Armstrong & Wheatley, 2012, provide an analogous example from mineralogy). For psychologists, theories about morality become more interesting if the theories can explain judgments about right and wrong without also having to explain the legal notion of “moral certainty.”

No easy formula tells us where to draw the line between the technically moral and the technically non-moral. In drawing this line, we trade overlap with everyday word usage against the psychological unity of the phenomena that fall under our definition of morality. As we increase the overlap with everyday usage, we incorporate a larger and more heterogeneous set of phenomena that need explaining. Later in this article, I will discuss my proposal for where to draw the line.

(b). The Functionalist Approach: Capturing Morality by its Societal or Evolutionary Function

A second, popular approach is to define morality by its societal or evolutionary function. Exemplifying this functionalist approach, Haidt (2008) defined morality as follows: “Moral systems are interlocking sets of values, practices, institutions, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make social life possible” (Haidt, 2008, p. 70; Greene, 2014; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010; Krebs, 2008; Curry et al., 2021). In a similar vein, from an evolutionary perspective, Krebs (2008) wrote: “The domain of morality pertains to the formal and informal rules and sanctions that uphold the systems of cooperation that enable members of groups to survive, to reproduce, and to propagate their genes” (p. 108). Focusing on the social function of morality, Kochanska and Aksan (2006) define morality as an inner guiding system that ensures “people’s compliance with shared rules and standards” (p. 1588). Each quote defines morality by its function or consequences, whether socially or evolutionarily. The definitions reference no psychological characteristics, such as cognitive or affective components.

When we define “morality” by its function or consequences, the risk is that we will capture phenomena that lack any shared psychological characteristics. Without shared psychological characteristics, we cannot form a meaningful psychological theory. Any number of characteristics might suppress selfishness and make social life possible, such as language, fear of punishment, and the ability to remember threats from others. Grammatical rules, for instance, make it possible to form verbal agreements of cooperation. Nonetheless, our understanding of grammatical rules have little in common with our capacity to form judgments about violence. To understand language, we will want a theory of language, not a theory of morality. Thus, even if the characteristics picked out by a functionalist theory are research-worthy, their heterogeny impedes interesting generalizations.

There is an even bigger challenge for functionalist theories. If morality is defined by its consequences, we might not know whether a psychological characteristic belongs to the moral domain until much later. It may take minutes, days, or years to know which characteristics ultimately promote cooperation or suppres selfishness in the long run. A well-intentioned effort to help another person might strengthen cooperation in one context, whereas an identical initiative might be rebuffed as a bothersome act of interference in another context (Oakley et al., 2011). Protests against social injustice can promote peaceful coexistence in some circumstances but increase societal conflict in other circumstances (Killen, 2016; Killen & Dahl, 2020). And who would know, prior to years of systematic research, whether a constitutional right to smoke weed or own a gun would be beneficial or detrimental to “peaceful coexistence”? If we rely on the functionalist criterion, we might only know if the acts of helping or protest counted as moral long after the acts occurred, if ever. Whereas this indeterminacy is not a problem for normative ethics, it is a problem for psychological science.6

In psychological science, we make and test empirical claims about psychological phenomena. To test our hypotheses against reality, we need criteria for picking out the psychological phenomena we are interested in. Definitions provide such criteria. To see the distinction between definitions and empirical claims, imagine an evolutionary biologist who said: “Primate hands evolved for climbing.”7 This is an empirical claim about the evolutionary function of hands and not a definition. We can tell it is an empirical claim because we can picture an empirical reality that would have falsified the claim. We can imagine that primate hands evolved for cracking nuts, or some other purpose, and only later became instruments for climbing. Similarly, we can ask questions about how morality—or a certain element of morality—affects coexistence or survival. These, too, are empirical questions that we can address once we have identified the phenomena that count as moral.

Definitions allow us to test our claims. To test whether hands evolved for climbing, the biologist would need a way of identifying hands across evolutionary time regardless of their function. The biologist might define hands as “five bendable fingers and a palm at the end of each arm.” Then, the biologist could see whether primates developed hands because of the survival benefits of climbing or because of some other benefit, such as tool use. Analogously, if moral psychologists are to examine the social or evolutionary consequences of morality, we need a definition of morality that identifies psychological phenomena irrespective of their empirical consequences. We need a psychological technical definition of morality.

(c). The Evaluating: Capturing the Set of (Morally) Right Actions

A third approach is to define morality in terms of right or good actions and traits. Much research on character development and moral identity takes this evaluating approach (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Krettenauer & Hertz, 2015; Nucci et al., 2014; Walker, 2014). These researchers define morality as the traits we ought to have—or that a plurality of research participants think we ought to have. In their influential study on moral identity, Aquino and Reed (2002) asked a sample of undergraduate students to list traits that “a moral person possesses” (p. 1426). Through content analysis, Aquino and Reed created a list of nine traits mentioned by at least 30% of their participants. (That the cut-off had to be 30% and not 100% hints at how differently people use the word “moral,” even people from same language community.) Their list, which became the basis for their Self-Importance of Moral Identity Questionnaire (SMI-Q), included the following nine traits: caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest, and kind.

After the publication of Aquino and Reed’s (2002) paper, numerous studies on moral identity have used the SMI-Q (for reviews, see Hertz & Krettenauer, 2016; Jennings et al., 2015). With time, researchers began to treat the nine traits of the SMI-Q as defining traits of morality. In their meta-analysis paper, Hertz and Krettenauer (2016) wrote that the SMI-Q “contains a list of nine attributes that are characteristic of a highly moral person” (p. 131). Here, the nine traits in the SMI-Q are no longer treated as traits that some of Aquino and Reed’s (2002) participants associated with morality. The traits become part of the scientific definition of a moral person, and individuals who possess these characteristics are said to have a “strong moral identity” (Hertz & Krettenauer, 2016, p. 129).

In a similar vein, research on moral disengagement tends to define morality based on what researchers evaluate as right and wrong behaviors (Bandura, 2002, 2016; McAlister et al., 2006). For instance, Bandura (1990, 2018) defines moral disengagement “a phenomenon in which moral self-sanctions are disengaged from detrimental behavior” (Bandura, 2018, p. 247). That is, to disengage morally means to engage in a “detrimental behavior” without viewing oneself negatively. Crucially, the literature on moral disengagement offers no separate criterion for determining which behaviors are detrimental. Rather, Bandura (2016) asserted that certain behaviors—capital punishment or efforts to increase birthrates in Western countries (pp. 392–393)—were inherently and self-evidently detrimental. He held these to be behaviors that a morally engaged person would condemn. By that logic, anyone who engages in such behaviors without feeling bad, and anyone who judges the actions to be okay, must have disengaged or “turned off” their morality (for discussion, see Dahl & Waltzer, 2018).

Kohlberg (1971) famously challenged those who defined morality as a list of desirable traits, colorfully calling such a list a “bag of virtues.” He wrote: “the trouble with the bag of virtues approach is that everyone has his own bag. The problem is not only that a virtue like honesty may not be high in everyone’s bag, but that my definition of honesty may not be yours” (p. 184). Indeed, reviews of lists of virtues across time, communities, and scholars reveal little consensus on which virtues are desirable (Nucci, 2004, 2019). In the face of disagreement, should morality be defined by the virtues that the researcher happens to prefer? Or the virtues preferred by some proportion of survey participants?

More fundamentally, to define morality via morally desirable traits traverses the old barrier between ought and is (Hume, 1738; Moore, 1903). Psychology, like any empirical science, is equipped to find out what is the case—what people actually do—but not what people ought to do. If psychological science defined morality as traits that are good or desirable, it would lack the means to determine which traits or actions actually fit within this definition.8 Even if most people in a community happened to believe that some trait constituted a virtue, it would not follow that this trait was actually (morally) good. The briefest reflection on societies that accepted slavery reminds us why we do not settle all moral questions by majority vote (Davis, 2006).

Although an empirical science cannot tell which actions are right and which are wrong, it can study how people judge which actions are right and which are wrong. Research on moral psychology investigates how some people come to support abortion rights while others oppose such rights (Craig et al., 2002; Dworkin, 1993; Gallup Inc., 2018; Helwig, 2006). This kind of investigation is the focus of the fourth approach to defining morality.

(d). The Normative: Capturing all considerations about right and wrong?

The normative approach is to define morality as comprising all normative considerations that generate judgments about right, wrong, good, or bad. We saw earlier how the Moral Foundations Questionnaire asks participants what they consider when they “decide whether something is right or wrong” (Graham et al., 2011; Haidt & Graham, 2007). In a similar spirit, Haidt (2001) and Schein and Gray (2018b) defined moral judgments as any evaluations based on virtues taken to be obligatory by a culture or subculture. And Hamlin (2013) defines our moral sense as a “tendency to see certain actions and individuals as right, good, and deserving of reward, and others as wrong, bad, and deserving of punishment” (p. 186; see also Malle, 2021). Here, too, morality is defined to incorporate all judgments of right, wrong, right, or bad, regardless of subject matter.

There is nothing wrong with studying norms—many people do (Bicchieri, 2005; Heyes, in press; Legros & Cislaghi, 2020; Schmidt & Tomasello, 2012; Sripada & Stich, 2006). But those who do “norm psychology” usually treat morality either as a subcategory of norms or a category altogether different from norms. Laying out their framework for the psychology of norms, Sripada and Stich (2006) write that the “category of moral norms is not coextensive with the class of norms that can end up in the norm database posited by our theory” (p. 291). To exemplify non-moral norms, they mention “rules governing what food can be eaten, how to dispose of the dead, how to show deference to high-ranking people” (p. 291). In her influential treatise on social norms, Bicchieri (2005) writes that “[s]ocial norms should also be distinguished from moral rules” (p. 8). While these authors do not agree on where to draw the line, they agree that there should be a line between morality and (other) norms.

For if we define morality to include all normative considerations, we blur some common-sense distinctions. People make normative judgments about right and wrong about almost any human activity (Daston, 2022). As Kohlberg (1971) observed, there is a right and a wrong way of mixing a martini, training for a sports race, and playing solitaire. And people do judge violations of instrumental norms or board game rules differently from how they judge harming or stealing from others (Dahl & Schmidt, 2018; Dahl & Waltzer, 2020a; Turiel, 1983). For instance, most adults think it is okay to violate norms of instrumental rationality (e.g., how to train for a race, how to bake a cake) if the person does not care about the goal served by that norm (e.g., doing well in the race, Dahl & Schmidt, 2018). In contrast, they judge that it is generally wrong to harm another person, whether or not you care about harming them (Dahl & Schmidt, 2018; Knobe, 2003). It is up to you whether you should try to do well in the marathon you signed up for. It is not up to you whether you should respect the welfare and rights of other people.

One feature that sets most game rules apart from prototypical norms is alterability. Children and adults view the rules of board games or sports as somewhat arbitrary and, accordingly, somewhat alterable (Dahl & Waltzer, 2020a; Hardecker et al., 2017; Köymen et al., 2014). They imagine that alternative rules would do equally well. Wikipedia currently lists 26 invented and regional variants of checkers (“Checkers,” 2022). In one variant—“Russian Column Draughts”—captured pieces are not removed but placed under the capturing piece to form a tower. Even if Russian checker players preferred Russian Column Draughts, they would probably recognize that alternative variants can be just as fun. In contrast, many standard moral norms, like the prohibition against hitting or stealing, are not seen as alterable. Even if the government legalized stealing or unprovoked violence, most people would judge such actions wrong (see Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 2015).

I will return to the distinction between moral and non-moral judgments in the next section. My point here is that, in ordinary language, many normative judgments about right, wrong, good, and bad fall outside what most people call “morality.” Some divergence between scientific and everyday usage is unavoidable—we already abandoned the idea of complete overlap. But do pool moral judgments with all normative judgments is like pooling the whales with the fishes. We seek a technical definition that overlaps with everyday usage yet retains enough psychological unity to theorize over. For this reason, we will seek a technical definition that sets moral judgments apart from at least some other normative judgments. This way, our technical definition will not force us to say that judgments about mixing partinis or playing checkers are moral judgments, and our theories of morality will not have to account for those judgments. We seek a definition that renders moral considerations distinctive among normative considerations

Summary: Four Approaches to Defining Morality and Their Difficulties

I have discussed four approaches to defining morality (Table 1). The linguistic approach defines morality as what people call “morality.” The functionalist defines morality in terms of its external function or consequences. The evaluating defines morality as a set of right or good characteristics. And the normative approach defines morality to incorporate all considerations about right, wrong, good, or bad. My goal was to provide a taxonomy of common and intuitive approaches to defining morality—of things we could do when we define morality for psychological research.

On inspection, each approach revealed its rubs. The linguistic approach faced the difficulty that the word “morality” has sundry uses, within and between individuals. To cope, we need a technical definition. For the functionalist approach, the trouble was we could not know whether something counted as moral without knowing its consequences, which could be unknowable or not knowable for a long time. When studying a psychological phenomenon, we need a definition that refers to psychological characteristics. The evaluating approach had the downside that empirical psychological science lacks a method for identifying (morally) good or bad traits or acts. Empirical science needs a descriptive definition of morality. And the normative approach failed to distinguish morality from other normative considerations, which would deviate unnecessarily from ordinary usage—and from current scientific usage. We will look for a definition that distinguishes morality from at least some normative considerations. In the next section, I will propose a definition that meets these four criteria.

What to Do When We Define Morality: A Proposal

When we define morality for psychological science, we can look for a definition that is (a) technical in that it overlaps with some, but not all, everyday uses of the words “moral” and “morality”; (b) psychological in that it identifies widely shared psychological phenomena without reference to their external functions or consequences; (c) descriptive in that it captures people’s evaluative judgments without committing scientists themselves to making evaluative judgments; and (d) distinctive in that it separates moral considerations from at least some other kinds of considerations about right and wrong.

Guided by these four criteria, I propose to define morality as obligatory concerns with how to treat other sentient beings (i.e., with others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice), as well as the reasoning, judgments, emotions, and actions that spring from these concerns (Dahl, 2019; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 1983, 2015; Turiel et al., 2018). For instance, a judgment about hitting is moral if it springs from an obligatory concern with others’ rights or welfare; the judgment is non-moral if it springs from a concern with staying out of trouble. An angry outburst at injustice is moral if it reflects the emoter’s obligatory concern with fairness or justice; the anger is not moral if the person is merely angry about not getting what they wanted (Batson et al., 2009; Wakslak et al., 2007).

The definition is not the sole sensible definition of morality for psychological research. Others may adopt different definitions that serve other ends. In this respect, my attitude is like Wittgenstein’s: “Say what you choose, so long as it does not prevent you from seeing the facts. (And when you see them, there is a good deal that you will not say)” (Wittgenstein, 1953, p. 37). If another definition suits a researcher’s project better—and allows the researcher to better “see the facts”—researchers could state that definition and their reasons for adopting it. Or if psychologists come together to develop a different, shared definition of morality—as Grossman and colleagues (2020) did for wisdom or as Scherer and Mulligan (2012) did for emotion—that would be a welcome development. In the meantime, each researcher can advance the field by explaining which definition of morality they adopt and why they adopt it. What follows is my attempt.

Morality as Rooted in Obligatory Concerns With Others’ Welfare, Rights, Fairness, and Justice

My definition of morality, rooted in obligatory concerns with how to treat others, builds on the work of Turiel (1983, 2015) and his collaborators (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Nucci, 2001).9 I single out these four types of obligatory concerns because they are inherently about how to treat other sentient beings, be they individuals, social groups, or animals. Concerns with others’ welfare are about promoting and protecting the psychological and physical well-being of others (Dahl et al., 2018; Schein & Gray, 2018b). Concerns with rights are about the protections and entitlements people owe to each other (Helwig, 2006; Hunt, 2008). Concerns with fairness are about distributing resources and privileges among others (Blake et al., 2015; Killen et al., 2018). And concerns with justice, as I define them here, are about the rewards and punishment that others deserve (D. Miller, 2017; Turiel et al., 2016).

Philosophers and psychologists have proposed both formal and substantive properties that distinguish morality from other normative domains (Gert & Gert, 2017; Kohlberg, 1971; Stich, 2018; Turiel, 1983). Formal properties are properties that can apply regardless of content. One common formal criterion is universalizability: A norm is moral if you can want it to be a universal law that every one followed (Kant, 1785; Kohlberg, 1971; Levine et al., 2020). This criterion imposes no limits on what those norms are about. We could imagine universalizing any norm, even if there are many norms we would not want to universalize. A person could treat a norm that everyone play Russian Column Draughts as a moral norm—as long as they could will that norm to become a law for law for all of humanity.

Substantive properties are properties that refer to specific content. A requirement that moral judgments always be about the relation between an agent and a suffering patient is a substantive requirement (Gray et al., 2012). This substantive requirement would preclude norms about how to play solitaire from being counted as a moral norm.

My definition includes both formal properties (the obligatoriness of concerns) and substantive properties (the concerns with others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice). I will first clarify the notion of obligatory concerns. Next, I will discuss why I separate (moral) obligatory concerns with others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice from other (non-moral) obligatory concerns.

Obligatory Concerns

The notion of concern, common in theories of emotion, is a cognitive-motivational construct (Dahl et al., 2011; Frijda, 1986; Lazarus, 1991; Mulligan & Scherer, 2012). Concerns are cognitive representations that we care about, such as human welfare, the will of God, or the success of our sports team (Dahl, 2017b; M. Lewis, 2007). Individuals map concerns onto specific situations or issues (C. S. Carver & Scheier, 2001). When we see one person hit another, we perceive a connection between the event and our concern for the welfare of others. When we watch our team play, we map our concern for the team’s success onto goals for our team (good news) and goals against our team (bad news).

Obligatory concerns are concerns that it would be wrong not to have (Dahl et al., 2020; Dahl & Schmidt, 2018). Obligatory concerns are those we believe others could not “reasonably reject,” if we borrow Scanlon’s (1998, p. 189) phrase.10 If you hold that everyone ought to concern themselves with the welfare of others, and that it would be wrong to lack this concern, then you would be treating that concern as obligatory. We can distinguish obligatory concerns from non-obligatory concerns, such as personal preferences, by two features: obligatory concerns, unlike non-obligatory concerns, can give rise to judgments that are both categorically negative and agent-neutral (Dahl & Freda, 2017; Kohlberg, 1971; Scanlon, 1998; Tomasello, 2018). Let me pause briefly to unpack each notion.

To consider a concern obligatory, a person must judge that it is categorically wrong to lack this concern, not merely suboptimal or non-preferred. Someone might wish others shared their love for red wine or soccer (Nucci, 1981, 2001). Still, unless they viewed concerns with red wine and soccer as obligatory, they would not view the indifference to red wine or soccer negatively. They would not experience frustration or disappointment upon learning that others preferred white wine or basketball. In contrast, if others were wholly unconcerned with women’s right to abortion, and the person viewed the concern with a right to abortion as obligatory, the person would condemn this lack of concern.

To demonstrate the categorical judgments that evidence obligatory concerns, we need categorical assessments. We cannot, for instance, use measurements of preferences to tell which concerns a person views as obligatory and which they view as non-obligatory. In research on the infant precursors of morality, one common paradigm is to show infants puppet shows involving three puppets: a helpful puppet, a hindering puppet, and a recipient puppet (Hamlin, 2013; Hamlin et al., 2007; Margoni & Surian, 2018). The helpful puppet always helps the recipient puppet, for instance, by retrieving a ball that the latter dropped; the hindering puppet always hinders the recipient puppet, taking the dropped ball instead of returning it. In a subsequent assessment, infants have the choice of reaching toward the helpful or hindering puppet. Most studies find that most infants reach toward the helpful puppet, suggesting that infants prefer helpful over hindering puppets. But such a preference for helpful over hindering puppets does not demonstrate categorically negative evaluations of the sort that obligatory concerns give rise to. The preference for the helpful puppet does show that infants had a categorically negative view of the hindering puppet; you can prefer Rome over Paris and still adore Paris (Dahl & Waltzer, 2020b).

The second characteristic of obligatory concerns is agent neutrality. Agent neutrality means that a person will condemn the lack of obligatory concerns regardless of their own role in the situation (Nagel, 1989; Scanlon, 1998; Tomasello, 2018). When you deem a concern obligatory, you will demand it from a first-, second-, and third-person point of view. Let us stipulate that a person who engages in unprovoked violence is unconcerned with the welfare of others. Let us also stipulate that I deem the concern with others’ welfare as obligatory. Then, I would reprehend unprovoked violence regardless of whether I am hitting someone else (first person), whether someone else is hitting me (second person), or whether I observe one person hit another (third person). If I merely thought it was bad for others to hit me, but completely fine for me to hit others, I would not be viewing the concern with others’ welfare as obligatory.

Third-person evaluations set humans apart from non-human primates. Chimpanzees do not like to be hit by others (second person), and they often refrain from violence against kin (first person). Still, chimpanzees do not generally react negatively when they observe unrelated individuals hitting each other (Silk & House, 2011; Tomasello, 2016).

Agent neutrality does allow moral judgments to consider social roles (Korsgaard, 1996). We can make agent-neutral evaluations about doctors’ duties toward their patients and about parents’ duties toward their children. What agent neutrality precludes is that the person makng the evaluation takes into account which role they—the evaluator—have in the situation. Imagine that I say that a soldier is obligated to concern themselves with the commands of an officer. I am saying that the soldier has to concern themselves with the officer commands irrespective of whether I am the soldier, the officer, or a bystander. I am not thereby saying that everyone, even civilians, has to concern themselves with the officer commands. Obligatory concerns can be specific to a social role or relationship; but they are not specific to me as me, nor to you as you.

Obligatory concerns do give rise to judgments other than judgments of obligation. Obligatory concerns can give rise to judgments about which of two permissible actions is better. And obligatory concerns generate judgments that an act is supererogatory: good, but not required (McNamara, 2011). People often judge some acts of helping others as supererogatory, especially when the helping would be costly to the helper (Dahl et al., 2020; Kahn, 1992; Killen & Turiel, 1998; J. G. Miller et al., 1990). Many of these supererogatory judgments about helping spring from obligatory concerns with others’ welfare: Helping would be a good thing to do because it benefits the welfare of others (Dahl et al., 2020).

Judgments of supererogation illustrate a broader characteristic of obligatory concern. To treat a concern as obligatory is to hold that the concern should always be considered, not that it always should be prioritized (Dahl & Schmidt, 2018; Scanlon, 1998). In dilemmas that pit two obligatory concerns against each other, it would actually be impossible to prioritize both concerns (Dahl et al., 2018; Turiel, 2002; Turiel & Dahl, 2019). If the rights of one person conflicts with the welfare of others, you cannot prioritize both your concerns with the former’s right and your concerns with the latter’s welfare. You can still think it obligatory to consider both concerns as you make your judgment.

And even after the judgment, the down-prioritized concerns continue to influence how we think and feel about the situation. When people harm others, they can still experience conflict and guilt about their decisions, even if they deem the harm justified (Hoffman, 2000; Wainryb, 2011). People who judge that they should disclose fraudulent practices in their company, and decide to blow the whistle, are often torn. Their actions prioritize their obligatory concern with honesty, but it violates their obligatory concerns with loyalty to their company and their co-workers. Whistleblowers can therefore feel deeply conflicted about their actions (Alford, 2002; Waytz et al., 2013). Other examples of dilemmas and conflicts are more mundane Since each person’s obligatory concerns form an incoherent whole, we often encounter situations that pit one concern against another. To make sense of those conflicts, we will want to draw some distinctions among kinds of obligatory concern, which I will consider next.

Separating Obligatory Concerns with Sentient Beings From Other Obligatory Concerns

Moral concerns are a subset of obligatory concerns, namely obligatory concern with the promotion and protection of others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice. Unlike other obligatory concerns, these deal intrinsically with how to treat other sentient beings. Whenever we consider others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice, it is somebody’s welfare, rights, fairness, and justice, whether that somebody is an adult, a child, an animal, or a social group.

People need not have a specific victim in mind when they map a situation onto moral concerns.11 To meet my definition of a moral judgment, a judgment needs only to deem that a transgressor showed insufficient concern for others’ welfare, rights, fairness, or justice, whether or not the transgressor harmed a specific victim. Within my framework, a person may judge that racist slurs are (morally) wrong even if nobody hears the slurs; and a person may judge a deceased person has (moral) rights to respectful treatment without assuming that the deceased person is harmed in an afterlife (Jacobson, 2012).

Thus defined, moral concerns differ from other obligatory concerns, such as concerns with authority commands. As we saw earlier, most people deem that we ought to concern ourselves with the demands of legitimate authorities, even if people disagree about which authorities are legitimate (Frimer et al., 2014; Laupa, 1991). Religious individuals also view concerns with gods or other religious authorities as obligatory entities (Nucci & Turiel, 1993; Srinivasan et al., 2019). In contrast to moral concerns, concerns with authority commands regulate social as well as non-social actions. Some authority concerns do tell us how to act toward another person (e.g., military officers requiring soldiers to salute them). But unlike moral concerns, authority concerns can also tell us how to promote our own wellbeing, as when health authorities tell us to smoke less and exercise more.

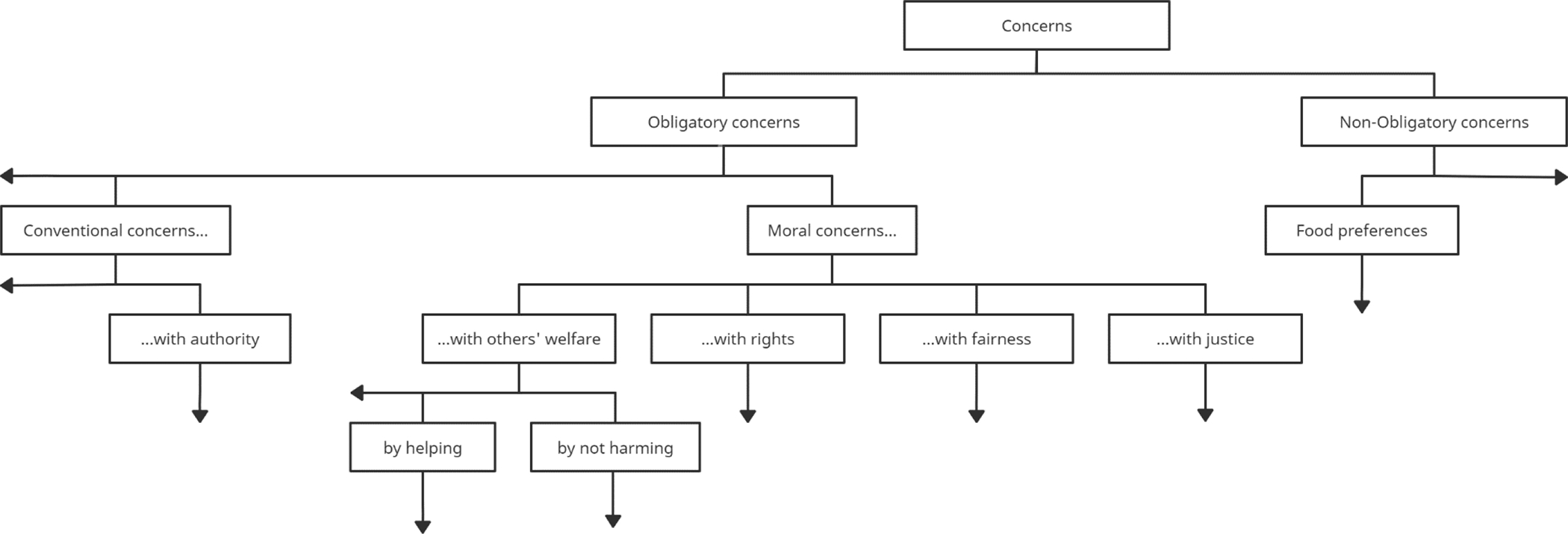

As Figure 2 shows, I classify concerns with authorities as a type of conventional concern (Dahl & Waltzer, 2020a; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 1983, 2015), along with concerns with traditions and consensus. Conventional concerns are obligatory concerns with the requirements of social institutions, be it the authorities atop those institutions (e.g., requests from a president or boss), the traditions that characterize the institutions (e.g., customs for how to dress in the office or how to behave a ceremony), or the consensus that the institution produces (e.g., the laws passed by a parliament or the agreement among checker players on which rules to use before a game).

Figure 2: Classification of Concerns.

Note. The figure illustrates different kinds of concerns. The top-level division separates obligatory and non-obligatory concerns. (To reiterate: A person deems a concern obligatory if they deem it wrong to lack this concern.) Obligatory concerns are divided into moral, conventional, and other obligatory concerns. Moral concerns are subdivided into concerns with others’ welfare, rights, fairness, and justice. Vertical arrows indicate further concerns within a given category. For instance, concerns with rights may be divided into concerns with property rights, rights to free speech, and so on (Helwig, 2006; Hunt, 2008; Turiel et al., 2016). Horizontal arrows indicate additional categories at the same level. For instance, in addition to moral and conventional concerns, individuals may also deem prudential (personal wellbeing) or pragmatic (material order) concerns obligatory (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Smetana, 2013; Srinivasan et al., 2019). Non-obligatory concerns are as multifarious as—if not more multifarious than—obligatory ones. Beyond food preferences, there are preferences for sports teams, romantic partners, and so on, many of which we might call “values” (Schwartz & Bardi, 2001)

A common misconception is that the label “conventional” implies lower importance compared to “moral”. Critics of the moral-conventional convention have asked why some norms should be relegated to “mere conventions” (Haidt & Graham, 2007, p. 100)? There is nothing “mere” about conventions, as I talk about them here. I use “moral” and “conventional” in a descriptive sense that implies no ranking of their importance. Individuals sometimes judge that they should violate a moral concern to prioritize a conventional concern, as when soldiers judge that they should follow an officer’s orders to harm another (Osiel, 2001; Turiel, 2002). From an empirical point of view, there is nothing inherently irrational or wrong about prioritizing conventional concerns over moral ones.

The technical distinction between moral and conventional concerns is useful because, like whales and fish, they tend to operate differently (see Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 1983, 2015). For instance, children and adults treat norms that serve (moral) concerns with others’ welfare, rights, justice, and fairness as more generalizable and less authority-dependent than norms that serve conventional concerns. Most judge that unprovoked violence would be wrong even in a place that had no rule against unprovoked violence (generalizability) and even if authorities gave permission (authority independence). In contrast, most would judge that it is okay to wear casual clothes to an office that has no dress code and that wearing casual clothes to the office is okay if the company C.E.O. gave permission.

People treat moral concerns as more generalizable and less authority-dependent than conventional concerns because moral concerns map onto intrinsic features of interpersonal relations (Turiel, 1983). Hitting another tends to cause pain to a victim no matter what the context is and no matter what authorities—even gods—permit (Nucci & Turiel, 1993; Srinivasan et al., 2019). Taking something that already belongs to another violates that person’s property rights, no matter where you are and no matter what authorities permit. (Of course, there is tremendous contextual variability in the procedures for establishing ownership rights; but the violation presupposes that ownership is established.) In contrast, showing up to the office in sweatpants has no intrinsic connection to others’ welfare: How your clothing affects others depends on how your clothing relates to prevailing dress codes and other customs.