Abstract

Bisexual individuals may experience pervasive binegativity originating from both heterosexual and lesbian/gay (L/G) individuals as a result of various psychosocial and relational factors. The present study aimed to explore how partner gender is particularly associated with experiences of binegativity from heterosexual and L/G persons and to examine how such experiences are related to internalized binegativity. A total of 350 self-identified cisgender bisexual men and women from across the United States were recruited online for this study. Participants completed an online survey battery assessing levels of both experienced and internalized binegativity. Regression analysis results indicated that binegativity from L/G persons, but not heterosexual persons, was significantly and positively associated with internalized binegativity. A significant interaction between binegativity from L/G persons and partner gender revealed a stronger association among those in same-gender relationships, such that those with same-gender partners who reported binegativity from L/G persons experienced more internalized binegativity than those with other-gender partners. When further examined by gender, these findings appeared to be driven by the relation among women, but not men, as women in same-gender relationships who reported binegativity from L/G persons reported the highest levels of internalized binegativity. Among men, binegativity from heterosexual, but not L/G, persons was significantly related to internalized binegativity independent of partner gender. The present study highlights key gender differences in interpersonal factors related to binegativity and have important implications for clinical practice with bisexual clients facing stigma and advocacy work addressing bisexual discrimination.

Keywords: binegativity, bisexual, internalized stigma, minority stress, partner gender

Numerous investigations have explored the associations between minority stress—chronic stress experienced by members of stigmatized minority groups—and the health and wellness of sexual minority populations (Meyer, 2003). Minority stress includes distal stressors (i.e., experiences in the environment), such as discrimination and marginalization, and proximal stressors (i.e., internal to the individual), such as internalized negativity about one’s sexual identity (Meyer, 2003). Minority stressors have been linked to negative psychological and behavioral health outcomes for sexual minority groups (Hughes & Eliason, 2002; Lewis, Derlega, Griffin, & Krowinski, 2003; Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Meyer, 1995). Bisexual individuals face prominent and unique stressors, yet a limited number of studies on minority stress have specifically explored the experiences of bisexual individuals. In particular, the gender of one’s partner can uniquely contribute to bisexual-specific stressors, as partner gender influences assumptions about an individual’s sexual orientation (Barker, Bowes-Catton, Iantaffi, Cassidy, & Brewer, 2008; McLean, 2018). The present study sought to build on existing literature on minority stress as applied to bisexual persons by considering how binegativity, a unique form of distal minority stress encountered by bisexual individuals, may be experienced as a function of one’s partner gender and contribute to proximal minority stress, experienced as internalized negativity about one’s bisexual identity.

Binegativity

In research on minority stress within sexual minority populations, bisexual individuals are often grouped with other sexual minorities rather than assessed as a unique group (Barker, 2008; McLean, 2018; Moradi, Mohr, Worthington, & Fassinger, 2009). Including bisexual persons among general sexual minority samples may be useful to capture aspects of shared experiences among sexual minority individuals, yet there are unique experiences and stressors common among bisexual individuals not experienced by their lesbian and gay (L/G) counterparts (Koh & Ross, 2006; Puckett, Horne, Herbitter, Maroney, & Levitt, 2017; Worthen, 2013). Indeed, bisexual individuals notably differ from L/G populations in many of their specific experiences of minority stress. Bisexual persons face unique stress because of the pervasiveness of binegativity—the constellation of prejudiced beliefs and attitudes about individuals who identify as bisexual (Dyar & Feinstein, 2018; Yost & Thomas, 2012). One such belief is that bisexual people regularly have multiple, uncommitted sexual partners. This assumption of sexual irresponsibility further promotes a view of bisexual individuals as being untrustworthy romantic partners and being more likely to have sexually transmitted infections (Brewster & Moradi, 2010; Mohr & Rochlen, 1999). Another belief is that bisexuality is an unstable or transitory sexual orientation, marked by commonly expressed assertions that bisexuals are going through a phase or that bisexual women are actually heterosexual, whereas bisexual men are actually gay (Eliason, 1997; Worthen, 2013). Binegativity has also been linked with hostile attitudes and behaviors toward bisexual persons from heterosexual persons, especially those who view sexual minority identities as being immoral or threatening to traditional values (Brewster & Moradi, 2010; Mulick & Wright, 2002).

In addition to binegativity from heterosexual persons, experiences of binegativity may originate from L/G persons. L/G persons may believe bisexuality is not a legitimate sexual orientation or may view bisexual individuals as being untrustworthy partners, in addition to potentially perceiving that bisexual persons are not supportive of issues related to sexual and gender minority rights (Flanders, 2018; Hayfield, Clarke, & Halliwell, 2014; Israel & Mohr, 2004; Mulick & Wright, 2002). The prevalence of binegativity among L/G and heterosexual persons manifests as what Ochs (1996) refers to as “double discrimination” (p. 1) for bisexual persons, a compounded sense of mistreatment unique to bisexual individuals who face discrimination even in circles in which sexual minority individuals might expect to find solace and support.

One notably adverse effect that results from such prevalent discrimination is the delegitimization of bisexuality (Belmonte & Holmes, 2016; Erickson-Schroth & Mitchell, 2009; Flanders, 2018; J. P. Paul, 1984; McLean, 2008), a harmful process that can serve to instill a sense of internalized binegativity in an individual (Puckett et al., 2017; Sheets & Mohr, 2009). Internalized binegativity is characterized by the adoption of negative attitudes toward one’s own bisexual identity and bisexuality in general, often stemming from persistent exposure to binegative perspectives (R. Paul, Smith, Mohr, & Ross, 2014; Roberts, Horne, & Hoyt, 2015). Internalized binegativity has been linked to adverse outcomes including low self-esteem, depression, problem drinking, substance abuse, and sexual identity uncertainty (Brewster, Moradi, DeBlaere, & Velez, 2013; Feinstein, Dyar, & London, 2017; Lambe, Cerezo, & O’Shaughnessy, 2017; R. Paul et al., 2014; Weber, 2008). Though community support has been found to buffer against such outcomes as internalized binegativity (Lambe et al., 2017), prevailing findings in the literature detailing a lack of social support for bisexual individuals from heterosexual and L/G persons have long been a cause for concern on the health and well-being of bisexual persons (Bradford, 2004; McLean, 2018; Ochs, 1996; J. P. Paul, 1984).

Binegativity and Partner Gender

It is necessary to consider the unique psychosocial and relational factors that may relate to experiences of binegativity across heterosexual and L/G networks. One factor that has gained recent attention in this domain is partner gender, which may be perceived by heterosexual and L/G persons as an indicator of one’s sexual orientation (Dyar, Feinstein, & London, 2014; Ross, Dobinson, & Eady, 2010). Partner gender may thus serve to influence bisexual individuals’ experiences of minority stress stemming from interactions with heterosexual and L/G persons. For instance, a bisexual woman with a male-identified partner may be assumed to be heterosexual (and a person who has not explicitly revealed their bisexual status with no partner may be assumed to be heterosexual, as this appears to be the default assumption for most individuals; Bem, 1995; Rich, 1980). This assumption could potentially reduce the frequency of binegativity she encounters among heterosexual individuals who may be unaccepting of sexual minority individuals, but could also reinforce the erasure of her bisexual identity and provoke increased binegativity among L/G individuals who may view this partnership as proof of an inauthentic sexual minority identity. Conversely, if the same bisexual woman later had a female-identified partner, she may be assumed to really be a lesbian woman (and a person who has openly revealed their bisexual identity with no partner may be assumed to be lesbian/gay; Eliason, 1997; Worthen, 2013). Although this could result in increased binegativity from heterosexual persons as a result of homonegativity, it could also lead to support from some L/G persons who feel a stronger sense of community with the woman as a result of her partner gender.

As is illustrated by the above examples, the assumptions about a bisexual individual based on their partner gender may dually serve to protect against and increase experiences of binegativity differentially when considering interactions with heterosexual and L/G persons. Given our society’s tendency to assume heterosexuality as a default orientation unless visible cues suggest otherwise (Bem, 1995; Rich, 1980), this is an important distinction to make for the present study, as it ultimately informed our decision to group participants without partners with those in other-gender relationships.

Whereas much of the limited work related to romantic/sexual partners and the wellness of bisexual individuals has homed in on how a partner’s gender can contribute to assumptions about sexual orientation, reinforce stereotypes about bisexual individuals’ qualities as romantic partners, and influence future partner selection (Bradford, 2004; Feinstein et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2010; Spalding & Peplau, 1997), partner gender has rarely been considered as a unique correlate of both experienced and internalized binegativity. Further, the differences in experiences of binegativity stemming from heterosexual and L/G persons has to date only been examined in two investigations identified by the authors of the present study. The first of these, conducted by Dyar and colleagues (2014), focused on an online sample of 106 bisexual women recruited as part of a greater study on the health of sexual minority women. This study considered differences in bisexual minority stress variables and dimensions of identity based on one’s partner gender status, uncovering the mediating effect of binegativity on the high rates of depression experienced by bisexual women with different-sex partners (Dyar et al., 2014). Though the findings from Dyar et al. highlighted the unique links between heterosexual- and L/G-specific binegativity and partner gender, the present study aims to expand upon how such relations may also influence experiences of internalized binegativity. Similarly, a recent study by Molina and colleagues (2015) also examined a subset of 470 bisexual women recruited online for a greater study on the health of sexual minority women. In this study, the authors examined partner gender and partner number, experienced and internalized binegativity, and depression and alcohol use. Women with single male and multiple male and female partners experienced greater levels of depression and alcohol-related problems, as mediated by experienced and internalized binegativity (Molina et al., 2015). It is worth noting, however, that although the measure of binegativity used in this study was described as capturing binegative experiences across heterosexual and L/G settings, the resulting findings were not explained in relation to these differential experiences of binegativity.

Although these two studies have helped to forward the bisexual health literature by elucidating the nuanced role of partner gender in experiences of binegativity, they were notably conducted exclusively with women and thus cannot reflect the experiences of bisexual men. In the absence of a more explicit rationale for their circumscribed sample, Molina et al.’s (2015) focus on bisexual women appeared to be driven by the primary focus of the parent study on the health of sexual minority women. Citing a more specific justification for their central focus on women, Dyar and colleagues’ (2014) investigation sought to highlight the unique forms of discrimination that may be prevalent within this subset of the bisexual population as a direct result of gender. Considering the implications of these studies for the wellbeing of bisexual persons, it is evident that there is still a pressing need to evaluate how the wellness of bisexual men might be uniquely affected by such factors as partner gender in the experiences of binegativity. Such efforts to extend the current literature to the experiences of bisexual men are paramount to building a more comprehensive knowledge base on the health and wellness concerns facing the bisexual population as a whole and developing and delivering appropriate health and wellness interventions within this community. As such, the present study aimed to explore both cisgender men and women’s experiences of binegativity originating from heterosexual and L/G persons, and assess how one’s partner gender is associated with experiences of binegativity across these networks. Further, we sought to investigate how these experiences of binegativity are related to internalized stigma in the form of internalized binegativity.

Informed by Meyer’s (2003) minority stress framework, we hypothesized that (a) having a same-gender partner, (b) experiencing binegativity from heterosexual persons, and (c) experiencing binegativity from L/G persons would be associated with greater internalized binegativity. We further hypothesized that (d) partner gender would interact with heterosexual and L/G binegativity, such that those in same-gender relationships who experienced binegativity from heterosexual people would exhibit more internalized binegativity, and that the converse would be true for those in other-gender relationships (e.g., women in relationship with men) encountering binegativity from L/G persons. We further sought to explore the nature of these relationships within men and women participants separately.

Method

Participants

A total of 460 participants consented to participate in the study. Of these, 30 were excluded from analyses because of endorsement of attraction to only one gender. In observing response data, an additional 26 were excluded for responding incorrectly to attention check items, and 15 were excluded for having completely missing data on key variables. Because of our inability to detect whether systematic differences existed for these participants as a result of the low cell sizes, we excluded from analyses 11 participants who identified as transgender or nonbinary, 12 participants who identified as a nonmonosexual identity other than bisexual, 14 individuals who reported having a partner who was nonbinary, transgender without specification of “man” or “woman,” or “a different gender,” and individuals who did not provide a response to the inquiry on partner gender. The final sample included 350 cisgender bisexual-identified participants. Participants identified as women (58.3%) and men (41.2%). Participants ranged in age from 18–73 years, with a median age of 31 (M = 32.25 years, SD = 8.56 years). Of the United States regions represented in the sample, 14.9% of participants were from Western states, 11.7% were from the Southwest, 20% were from the Midwest, 23.7% were from the Northeast, 26.6% were from the Southeast, and 3.1% did not provide their location. New York (8.3%), California (8%), and Florida (7.7%) were the most prominently represented states in the sample. Regarding to race/ethnicity, 72% of participants identified as White (n = 253), 11% as Black/African American, 6% as Hispanic/Latino/a, 5% as Asian/Asian American, 4% as mixed-race, 1% as American Indian or Alaska Native, and less than 1% as another race/ethnicity. Regarding relationship status, 77% of participants (n = 271) reported currently being in a relationship. Of these, 22% reported relationships with a same-gender partner only, 61% reported relationships with an other-gender partner only, and 17% reporting relationships with partners of both same and other genders.

Measures

Partner gender.

A single item was used to identify the gender of a participant’s current romantic and/or sexual partner(s). Participants could report current partners who were men, women, transgender, nonbinary, and/or a different gender (participants could select more than one of these options if they were in more than one romantic/sexual relationship), or that they were not currently in a relationship. A dichotomous variable was created to indicate whether participants were in a same-gender relationship or not, the latter of which included those in other-gender or no relationships. As previously discussed, we included those who reported no partners with those in other-gender relationships as those participants would be assumed by others to be heterosexual by others (Bem, 1995; Rich, 1980).

Experiences of binegativity.

Binegativity was measured using the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale (ABES; Brewster & Moradi, 2010). The ABES is a 17-item measure that explores experiences of prejudicial treatment of bisexually identified individuals, as is characterized by assumptions of sexual orientation instability (sample item, “People have acted as if my sexual orientation is just a transition to a gay/lesbian orientation.”). The ABES has a six-point response scale (1 = This has never happened to you, 6 = This has happened to you almost all of the time). Participants were instructed to answer each item twice, with the first reflecting experiences with heterosexual individuals (ABES-H) and the second reflecting experiences with lesbian and gay individuals (ABES-LG). Mean scores for ABES-H and ABES-LG were calculated. Gender-specific mean ABES-H and ABES-LG scores for men and women were also calculated for separate analyses.

Internalized binegativity.

Internalized binegativity was measured using the three-item internalized homonegativity subscale from the revised Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS; Mohr & Kendra, 2011). The internalized homonegativity subscale uses a six-point rating scale (1 = disagree strongly to 6 = agree strongly) and includes items related to the negative self-view of one’s bisexual identity (e.g., “If it were possible, I would choose to be straight”). Mean scores were calculated for the full sample, men only, and women only.

Procedure

Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to data collection from the authors’ institution. Participants for this study were recruited online through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online marketplace in which individuals post job requests and users opt in to complete these requests for money (Ipeirotis, 2010). In considering online data collection sources, MTurk has been found to be a particularly effective means of collecting quality data (Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010), capturing diverse samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011), and conducting sound behavioral research (Mason & Suri, 2012; Paolacci & Chandler, 2014).

The present study was described as an investigation of bisexual individuals’ wellness. Eligibility criteria stipulated that participants had to be 18 years of age, live in the United States, express attraction to more than one gender, and have a prior task approval rating of 95% or better on MTurk. After electronically providing informed consent and answering demographic questions, participants were screened via a single question on whether they were attracted to one gender or more than one gender (see below), to ensure that the participants met eligibility criteria. Participants who reported attraction to more than one gender were then directed to complete the remainder of the survey. Embedded in the survey were two attention check items (e.g., “Please check strongly agree”). Participants who did not respond to these items correctly were exited from the survey and their data were excluded from this report. Those who completed the study received $1.00 credited to their MTurk account.

Results

A power analysis indicated that, at alpha of .05, β = .08 for the most complex model in this study, a sample size of 85 would be sufficient to detect a medium-sized effect. Thus, our sample size was sufficient for the analysis undertaken. Bivariate correlations, descriptive statistics, and Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability coefficients for the total sample are presented in Table 1, and for the sample divided by gender in Table 2. The sample consisted of individuals who were currently in same-gender relationships only (23 men, 37 women), other-gender relationships only (63 men, 103 women), relationships with partners of both same and different genders (23 men, 22 women), or not currently in relationships (37 men, 42 women).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Model Variables (Total Sample)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SGR | — | .20** | .22** | .12* | .02 | .00 | .30 | .46 | — |

| 2. ABES-H | — | .80** | .34** | −.14* | .07 | 2.35 | 1.07 | .96 | |

| 3. ABES-LG | — | .40** | −.14* | .06 | 1.99 | 1.02 | .97 | ||

| 4. IB | — | −.10 | .06 | 2.65 | 1.44 | .87 | |||

| 5. Age | — | −.12* | 32.25 | 8.56 | — | ||||

| 6. Race/ethnicity | — | .28 | .45 | — |

Note. SGR = same-gender relationship status, where 0 = not in same-gender relationship, 1 = in same-gender relationship; ABES-H = binegativity from heterosexual persons; ABES-LG = binegativity from lesbian/gay persons; IB = internalized binegativity. Race/ethnicity is coded such that White = 0, all other identities (including multiracial including White) = 1. The range of possible scores is 0–6 for both ABES measures and 0–7 for IB.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Model Variables (By Gender)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SGR | — | .19** | .19** | .11 | .08 | −.01 | .29 | .45 | — |

| 2. ABES-H | .20* | — | .81** | .22** | −.09 | .02 | 2.21 | 1.01 | .96 |

| 3. ABES-LG | .24** | .78** | — | .33** | −.06 | .02 | 1.84 | 0.91 | .96 |

| 4. IB | .13 | .42** | .39** | — | .01 | −.05 | 2.36 | 1.35 | .87 |

| 5. Age | −.07 | −.19* | −.23** | −.22** | — | −.10 | 32.76 | 9.24 | — |

| 6. Race/ethnicity | .00 | .15 | .11 | .21** | −.16 | — | .27 | .45 | — |

| M | .32 | 2.54 | 2.20 | 3.06 | 31.55 | .28 | |||

| SD | .47 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.46 | 7.48 | .45 | |||

| α | — | .96 | .97 | .86 | — | — |

Note. Coefficients below the diagonal represent correlations for men (n = 146); those above the diagonal represent correlations for women (n = 204). SGR = same-gender relationship status, where 0 = not in same-gender relationship, 1 = in same-gender relationship; ABES-H = binegativity from heterosexual persons; ABES-LG = binegativity from lesbian/gay persons; IB = internalized binegativity. Race/ethnicity is coded such that White = 0, all other identities (including multiracial including White) = 1. The range of possible scores is 0–6 for both ABES measures and 0–7 for IB.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Across the entire sample, ABES-H and ABES-LG means were comparable with means for these measures previously found in studies with similarly composed samples (Brewster & Moradi, 2010; Brewster et al., 2013; Lambe et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2015). However, internalized binegativity means in our sample were somewhat higher than those found in prior studies with bisexual individuals, with this difference ranging from .52 to .84 points based on the comparison studies examined (Mohr & Kendra, 2011; Sheets & Mohr, 2009). Results of the Pearson correlations indicated that being in a same-gender relationship was weakly and positively correlated with internalized binegativity. Binegativity from heterosexual people was moderately and positively correlated with internalized binegativity, as was binegativity from lesbian and gay people. For men only, being in a same-gender relationship was not correlated with internalized binegativity. However, binegativity from heterosexual people and from lesbian and gay people was moderately and positively correlated with internalized binegativity. For women, the results were similar for all relations of interest; being in a same-gender relationship was not correlated with internalized binegativity, whereas binegativity from heterosexual people and lesbian and gay people was weakly/moderately and positively correlated with internalized binegativity.

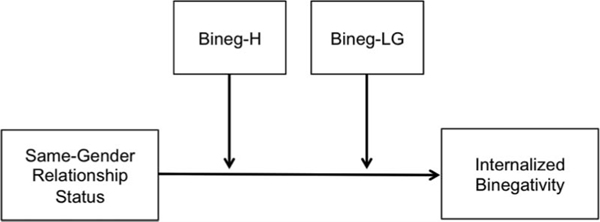

Moderation analyses were conducted using Hayes’ (2012) PROCESS Macro, Model 2, to examine a model with one predictor (same-gender relationship vs. not), two moderators ([1] experiences of binegativity from heterosexuals and [2] L/G people), and one dependent variable (internalized binegativity). In an effort to avoid confounds related to the complex effects of racial/ethnic identity (Bowleg, 2013; Dyar & Feinstein, 2018; Huang et al., 2010) and age (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013) on experiences of sexual minority discrimination, we also included race/ethnicity (coded such that White = 0, all other groups = 1) and age as covariates. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. The overall model was significant, F(7, 342) = 10.66, p = .001, R2 = .18. With regard to our first hypothesis, being in a same-gender relationship was not significantly related to internalized binegativity (B = .07, SE = .16, p = .68). With respect to our second and third hypotheses, we found that although binegativity from heterosexual persons was not significantly associated with greater internalized binegativity (B = .09, SE = .11, p = .40), binegativity from L/G persons was (B = .41, SE = .12, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for relation between same-gender relationship status and internalized binegativity as is moderated by binegativity from heterosexual (Bineg-H) and lesbian/gay (Bineg-LG) persons.

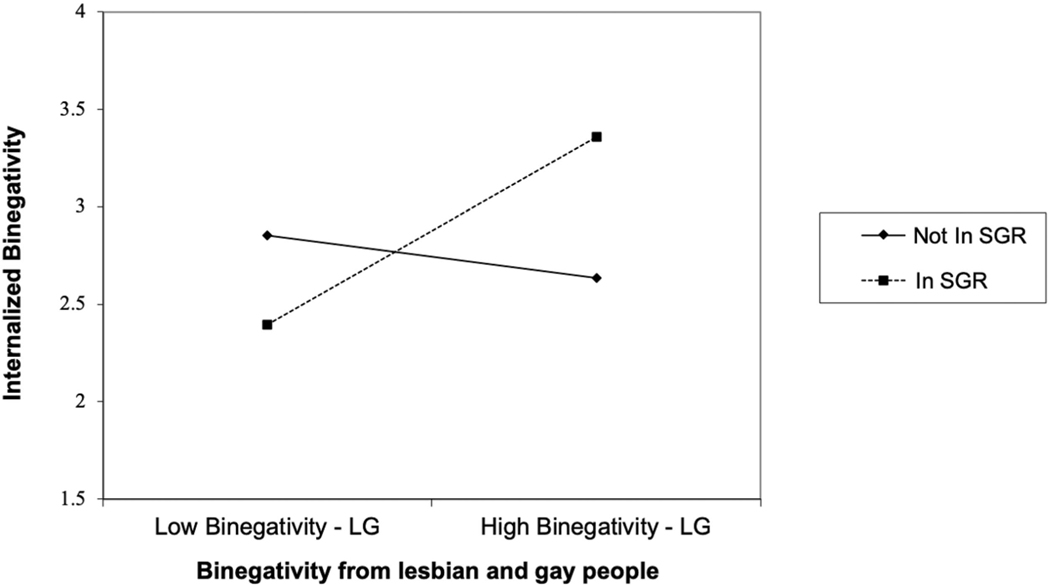

Our fourth hypothesis regarding the interactions between partner gender and experiences of binegativity from heterosexual and L/G persons was partially confirmed. The interaction between partner gender and binegativity from heterosexual people was not significantly associated with internalized binegativity (B = −.25, SE = .24, p = .31) and its inclusion in the model did not improve R2; F(1, 342) = 1.05, p = .31, ΔR2 = .00. However, the interaction between binegativity from L/G persons and partner gender was significant (B = .63, SE = .25, p < .05) and improved R2; F(1, 342) = 6.46, p < .05, ΔR2 = .02. Simple slopes for this interaction are displayed in Figure 2. For individuals who were in same-gender relationships, there was a positive relation between experiences of binegativity from L/G persons and internalized binegativity. For individuals who were not in same-gender relationships, this relation was weaker.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect between binegativity from lesbian and gay (LG) people and same-gender relationship (SGR) status on internalized binegativity (N = 350).

We further examined our hypotheses by gender. Among women, the results related to our first two hypotheses remained consistent with the findings for the entire sample. For women, the entire model was significantly associated with internalized binegativity, F(7, 196) = 5.49, p < .001, R2 = .16. Being in a same-gender relationship (B = .11, SE = .20, p = .59) and binegativity from heterosexual persons (B = −.14, SE = .15, p = .36) were not significantly related to internalized binegativity. The relationship between binegativity from L/G persons and internalized binegativity was significant (B = .50, SE = .17, p < .01). As was the case in our overall sample, the interaction between partner gender and binegativity from heterosexual people was not significantly associated with internalized binegativity among women (B = −.39, SE = .31, p = .21), but the interaction between binegativity from L/G persons and partner gender (B = .91, SE = .34, p < .01) was significant and in the same pattern as within the total sample. The influence of the significant interaction in the model improved R2; F(1, 196) = 7.34, p < .01, ΔR2 = 0.03.

Among men, our results were notably varied when compared with those in the overall and women-only samples. The entire model was significantly associated with internalized binegativity, F(7, 138) = 6.06, p < .001, R2 = .24. Being in a same-gender relationship was not significantly associated with internalized binegativity for men (B = .04, SE = .25, p = .87). There was a significant relationship between binegativity received from heterosexuals (B = .36, SE = .16, p < .05), but not L/G persons (B = .16, SE = .16, p = .32) and internalized binegativity. Neither of the interactions related to partner gender and binegativity from heterosexuals (B = .13, SE = .38, p = .72) and L/G persons (B = .19, SE = .38, p = .62) was significantly associated with internalized binegativity among men. Thus, though binegativity impacted both women and men, the interaction with partner gender appeared to be most influential for women.

Discussion

The present study sought to examine reported experiences of binegativity experienced from heterosexual and L/G persons and their relation to internalized binegativity in a sample of bisexual men and women. Further, we aimed to examine this relation as it is moderated by partner gender. Our results suggest key gender differences with regard to these differential experiences of binegativity from heterosexual and L/G individuals and their relation to internalized binegativity.

Our overall findings with regard to the significant relation between binegativity from lesbian and gay persons and internalized binegativity were ultimately informed by a prominent effect among women, which masked the additional effect of binegativity from heterosexual persons for men. For women, experiences of bisexual stigma from L/G but not heterosexual persons were found to be significantly related to internalized binegativity, whereas for men the opposite was true. This finding speaks to differential influences of L/G and heterosexual community perceptions for bisexual men and women. Although cisgender bisexual women and men have been generally found to face comparable levels of binegativity from L/G persons (Dyar, Feinstein, & Davila, 2019; Friedman et al., 2014), such identity-related discrimination for bisexual women typically involves a stereotypical assumption that they are actually heterosexual, whereas bisexual men are often believed to be actually gay (Yost & Thomas, 2012). For women, this assumption may essentially compromise the in-group support they might otherwise receive from L/G persons if they endorsed a monosexual identity (Hayfield et al., 2014; McLean, 2008). As the sexual orientations of bisexual women have indeed been found to be especially scrutinized by lesbian women (Belmonte & Holmes, 2016; Mohr & Rochlen, 1999), the further rejection experienced from other sexual minority women may certainly serve to compound this experienced sense of societal rejection and identity invalidation already prevalent among bisexual individuals (Ochs, 1996; J. P. Paul, 1984) and produce increased feelings of internalized binegativity (Puckett et al., 2017; Sheets & Mohr, 2009).

For men, our finding that binegativity from heterosexual but not L/G individuals relates significantly to elevations in internalized binegativity is consistent with the previous findings in the literature on such effects of reduced social support for bisexual individuals (Puckett et al., 2017), and men in particular (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009). Bisexual men have often been found to be viewed less favorably among heterosexual individuals—and especially heterosexual men—when compared with bisexual women (Dodge et al., 2016; Eliason, 1997; Herek, 2002; Yost & Thomas, 2012). Such a prevalence of binegativity in heterosexual spheres may in part be explained by commonly held stereotypical beliefs that bisexual men are actually gay, and thus are, like gay men, often perceived as sexually irresponsible, untrustworthy in relationships, and perpetrators of unwanted sexual advances toward other men, among other prejudiced beliefs (Eliason, 1997; Worthen, 2013). Independent of the identity-related difficulties such experiences of hostility might promote, bisexual men may also find these stereotypes difficult to overcome when seeking relationships with heterosexual women (Feinstein, Dyar, Bhatia, Latack, & Davila, 2016; Spalding & Peplau, 1997), which may further lead to sexual identity concealment, uncertainty, or other practices that contribute to internalized negativity about one’s own sexual orientation. As the negative reactions toward bisexual men may also serve to attack their perceived nonconformity to desirable masculine norms (Eliason, 2001; Worthen, 2013), experiences of binegativity in heterosexual settings may prove to be especially challenging in regard to internalized perceptions of sexual identity.

The overall significant interaction found between partner gender and binegativity from L/G persons in relation to internalized binegativity was also a reflection of the pronounced effect among women, but not men, in our sample. The finding that women in same-gender relationships who encounter binegativity from lesbian and gay individuals experience the highest rates of internalized binegativity was contrary to our hypothesis and initially perplexing. Indeed, similar studies have previously found that bisexual women in relationships with men often tend to see more negative effects related to binegativity from L/G persons than those in relationships with women (Dyar et al., 2014; Molina et al., 2015). However, the nature and direction of this interaction might be reasonably explained by the jarring quality of experienced binegativity from L/G persons for bisexual women in same-gender relationships. That is, bisexual women in same-gender relationships might expect to be more accepted by lesbian and gay individuals, so if they still found themselves experiencing binegativity in this group, they might feel exponentially invalidated and thus would view their bisexual identities even more negatively that women who already expected to encounter stigma (i.e., bisexual women in other-gender relationships). As we did not include a measure related to expectations of stigma, this particular interpretation cannot be statistically confirmed, but future research would benefit from inclusion of such variables in examining the nuances of heterosexual- and L/G-specific binegativity. In any case, this finding suggests that, at least for bisexual women, partner gender may serve to impact the resonant effects of binegativity on internalized perceptions of one’s sexual identity.

The present results have notable implications for work with bisexual clients. Foremost, our findings provide further support of extant research that has long found bisexual individuals at a heightened risk for double discrimination across both heterosexual and L/G networks (Ochs, 1996). Research has long found that support from one’s own community can often be an invaluable buffer against the negative health and wellness effects of chronic societal stressors that often affect minority-identified individuals (Meyer, 2003). However, even despite the increasing acceptance of sexual minority individuals in our modern society, our investigation finds that community support may still be difficult to come by for bisexual women and men across heterosexual and L/G settings alike. In working with members of the bisexual population, mental health professionals should thus be mindful to take an affirmative approach to identity-related concerns, and also remain sensitive to the complex social challenges this population faces, especially when discussing potential supportive resources for dealing with experiences of stigma.

Even further, our findings highlight a need for more nuanced approaches to addressing intra- and intercommunity conflicts for sexual minority individual in both research and advocacy—notably with regard to gender differences. Although bisexual individuals have often been lumped together with other sexual minority individuals in discussions related to social justice and discrimination, it is important to consider the unique community experiences—like those examined in the current study—that differentiate such groups from one another and thus beg for a reconsideration of such homogeneous approaches. As bisexual women have been particularly found to be at risk for adverse health and wellness issues (Belmonte & Holmes, 2016; Bostwick et al., 2007; Kerridge et al., 2017), our findings particularly highlight a need for crucial dialogues within sexual minority communities regarding the detrimental effects of intragroup discrimination and prejudice. Additionally, although the inclusion of bisexual men in our study further serves to expand the knowledge base of the experiences of such individuals, our findings point to a need for efforts that continue to promote acceptance for bisexual men within the majority population. As there is a dearth of studies in the literature specifically focused on the health and wellness correlates of bisexual men in isolation, additional work with this subset of the population is also recommended.

Although we believe our study has helped to expand the knowledge surrounding heterosexual- and L/G-specific binegativity, partner gender, and internalized binegativity, there are a number of limitations to our efforts that warrant mention. First, our analyses did not consider the effect of having relationships with multiple partners as opposed to a single partner. Indeed, polyamorous relationship practices may contribute to unique experiences of stigma in their own right (Burleigh, Rubel, & Meegan, 2017). Though we did not measure variables that established self-identified polyamorous practices or confirmed the knowledge of multiple partners by others in our participants’ lives, and thus did not adjust our model to include such considerations, it has been found that having multiple partners may contribute uniquely to experiences of binegativity (Molina et al., 2015). That said, we recognize that it is certainly worth exploring and disentangling experiences of polyamory- or consensual nonmonogamy-based discrimination versus sexual orientation-based discrimination in future studies. Further, given the prevalence of such relationships among bisexual individuals compared to lesbian and gay individuals (Balzarini et al., 2018; Rust, 2003) and the complexities related to such relationships for bisexual individuals (Manley, Diamond, & Van Anders, 2015), it is imperative that future researchers also work to develop a more expansive view of how support in polyamorous relationships may uniquely relate to how one manages experiences of binegativity. Second, we did not include individuals in our sample whose gender identification was transgender or nonbinary. Given the notably elevated levels of stigma and adverse health outcomes experienced by gender minority individuals (Grant et al., 2011; Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Miller & Grollman, 2015) and the compounded minority stress uniquely experienced by gender minority individuals who hold bisexual identities (Katz-Wise, Mereish, & Woulfe, 2017), we believed a focus on cisgender individuals would aid in a more direct examination of sexual-orientation–based stigma as opposed to stigma resulting from gender minority status for the purposes of our study. Additionally, the binary nature of our partner status variable (same-gender relationship vs. other-gender relationship) further precluded our ability to include non-binary–identified individuals. That said, we believe that future work in this area should certainly seek to investigate the unique experiences and challenges facing transgender and non-binary bisexual individuals. Third, our analyses were primarily limited to examining the relation among binegativity, partner gender, and internalized binegativity, though we acknowledge that internalized binegativity may also be related to other subsequent adverse mental health outcomes. For the sake of further expanding upon the impact of heterosexual- and L/G-based binegativity, we thus aim to conduct future analyses that acknowledge such relations not examined in the present investigation. Fourth, although we made all conscious efforts to recruit a racially/ethnically diverse sample, our MTurk sample was composed primarily of White-identified individuals, and cells sizes were not large enough to conduct comparisons between racial/ethnic groups. Our findings thus may not accurately reflect the experiences of non-White sectors of the bisexual population. Sexual minority individuals of color have been found to experience more complex forms of discrimination as a result of dual minority status (Balsam, Molina, Beadnell, Simoni, & Walters, 2011), and though we controlled for race/ethnicity in our study, further work would benefit from shifting focus toward these intersectional issues and gathering larger samples of racially/ethnically diverse bisexual individuals for more representative analyses. Similarly, we did not collect information regarding socioeconomic status, which we recognize may be relevant in understanding how social class may influence how bisexual individuals differentially perceive discrimination. Future studies should aim to gather such information in an effort to elucidate these potential relations between class, bisexual identity, and experiences and perceptions of stigma.

Despite such limitations we believe that our findings provide a solid framework for future investigations that could further consider the role of interpersonal relationships—romantic, sexual, or otherwise—in experiences of binegativity. Although partner gender may speak to the salience of one’s sexual identity across various settings, it is only part of the story behind experiences of bisexual discrimination that we hope will be further elucidated by work that builds upon these ideas. We further hope that drawing attention to an oft-overlooked intracommunity concern of binegativity from L/G persons will inspire future research on the treatment and compounded marginalization of various other subsets of the sexual minority population, such as gay and lesbian people of color or LGB individuals living with disabilities. Ultimately, our study highlights the need for continued research on the experiences and health of bisexual individuals that can be translated to both practice and advocacy efforts in the name of equality and social acceptance.

Public Significance Statement.

Results from an analysis of 350 bisexual individuals shed light on binegativity experienced by women in same-gender relationships from lesbian/gay persons, binegativity experienced by men from heterosexual persons, and the influence of these experiences on increased internalized stigma. This study highlights the differential influence of relationships on bisexual prejudice experienced by men and women and calls attention to potential interpersonal barriers relevant to clinical and advocacy work with bisexual people.

References

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, & Walters K. (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Micro-aggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 163–174. 10.1037/a0023244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini RN, Dharma C, Kohut T, Holmes BM, Campbell L, Lehmiller JJ, & Harman JJ (2018). Demographic comparison of American individuals in polyamorous and monogamous relationships. Journal of Sex Research. Advance online publication. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1474333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker M. (2008). Heteronormativity and the exclusion of bisexuality in psychology. In Clarke V. & Peel E. (Eds.), Out in psychology (pp. 95–117). West Sussex, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Barker M, Bowes-Catton H, Iantaffi A, Cassidy A, & Brewer L. (2008). British bisexuality: A snapshot of bisexual representations and identities in the United Kingdom. Journal of Bisexuality, 8, 141–162. 10.1080/15299710802143026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte K, & Holmes TR (2016). Outside the LGBTQ “safety zone”: Lesbian and bisexual women negotiate sexual identity across multiple ecological contexts. Journal of Bisexuality, 16, 233–269. 10.1080/15299716.2016.1152932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL (1995). Dismantling gender polarization and compulsory heterosexuality: Should we turn the volume down or up? Journal of Sex Research, 32, 329–334. 10.1080/00224499509551806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, McCabe SE, Horn S, Hughes T, Johnson T, & Valles JR (2007). Drinking patterns, problems, and motivations among collegiate bisexual women. Journal of American College Health, 56, 285–292. 10.3200/JACH.56.3.285-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2013). “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 68, 754–767. 10.1007/s11199-012-0152-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. (2004). The bisexual experience: Living in a dichotomous culture. Journal of Bisexuality, 4, 7–23. 10.1300/J159v04n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, & Moradi B. (2010). Perceived experiences of antibisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 451–468. 10.1037/a0021116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Moradi B, DeBlaere C, & Velez BL (2013). Navigating the borderlands: The roles of minority stressors, bicultural self-efficacy, and cognitive flexibility in the mental health of bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 543–556. 10.1037/a0033224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, & Gosling SD (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. 10.1177/1745691610393980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh TJ, Rubel AN, & Meegan DV (2017). Wanting ‘the whole loaf’: Zero-sum thinking about love is associated with prejudice against consensual non-monogamists. Psychology & Sexuality, 8, 24–40. 10.1080/19419899.2016.1269020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge B, Herbenick D, Friedman MR, Schick V, Fu TJ, Bostwick W, . . . Sandfort TGM (2016). Attitudes toward bisexual men and women among a nationally representative probability sample of adults in the United States. PLoS ONE, 11, e0164430. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, & Feinstein BA (2018). Binegativity: Attitudes toward and stereotypes about bisexual individuals. In Swan DJ & Habibi S. (Eds.), Bisexuality: Theories, research, and recommendations for the invisible sexuality (pp. 95–111). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. 10.1007/978-3-319-71535-3_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, & Davila J. (2019). Development and validation of a brief version of the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48, 175–189. 10.1007/s10508-018-1157-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, & London B. (2014). Dimensions of sexual identity and minority stress among bisexual women: The role of partner gender. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 441–451. 10.1037/sgd0000063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ (1997). The prevalence and nature of biphobia in heterosexual undergraduate students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 317–326. 10.1023/A:1024527032040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ (2001). Bi-negativity: The stigma facing bisexual men. Journal of Bisexuality, 1, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson-Schroth L, & Mitchell J. (2009). Queering queer theory, or why bisexuality matters. Journal of Bisexuality, 9, 297–315. 10.1080/15299710903316596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Dyar C, Bhatia V, Latack JA, & Davila J. (2016). Conservative beliefs, attitudes toward bisexuality, and willingness to engage in romantic and sexual activities with a bisexual partner. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1535–1550. 10.1007/s10508-015-0642-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Dyar C, & London B. (2017). Are outness and community involvement risk or protective factors for alcohol and drug abuse among sexual minority women? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1411–1423. 10.1007/s10508-016-0790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE (2018). The male bisexual experience. In Swan DJ & Habibi S. (Eds.), Bisexuality: Theories, research, and recommendations for the invisible sexuality (pp. 127–143). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. 10.1007/978-3-319-71535-3_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Emlet CA, Kim HJ, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Goldsen J, & Hoy-Ellis CP (2013). The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. The Gerontologist, 53, 664–675. 10.1093/geront/gns123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MR, Dodge B, Schick V, Herbenick D, Hubach R, Bowling J, . . . Reece M. (2014). From bias to bisexual health disparities: Attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. LGBT Health, 1, 309–318. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, & Keisling M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved from https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. 10.1016/j.dss.2003.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayfield N, Clarke V, & Halliwell E. (2014). Bisexual women’s understandings of social marginalisation: ‘The heterosexuals don’t understand us but nor do the lesbians’. Feminism & Psychology, 24, 352–372. 10.1177/0959353514539651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, & Testa RJ (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43, 460–467. 10.1037/a0029597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2002). Heterosexuals attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 264–274. 10.1080/00224490209552150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, & Cogan JC (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 32–43. 10.1037/a0014672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YP, Brewster ME, Moradi B, Goodman MB, Wiseman MC, & Martin A. (2010). Content analysis of literature about LGB people of color: 1998–2007. The Counseling Psychologist, 38, 363–396. 10.1177/0011000009335255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, & Eliason MJ (2002). Substance use and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 22, 263–298. 10.1023/A:1013669705086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ipeirotis PG (2010). Analyzing the Amazon Mechanical Turk marketplace. XRDS Crossroads: The ACM Magazine for Students, 17, 16. 10.1145/1869086.1869094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israel T, & Mohr JJ (2004). Attitudes toward bisexual women and men: Current research, future directions. Journal of Bisexuality, 4, 117–134. 10.1300/J159v04n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Mereish EH, & Woulfe J. (2017). Associations of bisexual-specific minority stress and health among cisgender and transgender adults with bisexual orientation. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 899–910. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1236181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, . . . Hasin DS (2017). Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM–5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 170, 82–92. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh AS, & Ross LK (2006). Mental health issues: A comparison of lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual women. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 33–57. 10.1300/J082v51n01_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe J, Cerezo A, & O’Shaughnessy T. (2017). Minority stress, community involvement, and mental health among bisexual women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4, 218–226. 10.1037/sgd0000222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ., Derlega VJ., Griffin JL., & Krowinski AC. (2003). Stressors for gay men and lesbians: Life stress, gay-related stress, stigma consciousness, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 22, 716–729. 10.1521/jscp.22.6.716.22932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manley MH, Diamond LM, & Van Anders SM (2015). Polyamory, monoamory, and sexual fluidity: A longitudinal study of identity and sexual trajectories. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2, 168–180. 10.1037/sgd0000098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, & Suri S. (2012). Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 44, 1–23. 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K. (2008). Inside, outside, nowhere: Bisexual men and women in the gay and lesbian community. Journal of Bisexuality, 8, 63–80. 10.1080/15299710802143174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K. (2018). Bisexuality in society. In Swan DJ & Habibi S. (Eds.), Bisexuality: Theories, research, and recommendations for the invisible sexuality (pp. 77–93). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. 10.1007/978-3-319-71535-3_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH, & Poteat VP (2015). A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 425–437. 10.1037/cou0000088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56. 10.2307/2137286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LR, & Grollman EA (2015). The social costs of gender nonconformity for transgender adults: Implications for discrimination and health. Sociological Forum, 30, 809–831. 10.1111/socf.12193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, & Kendra MS (2011). Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 234–245. 10.1037/a0022858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, & Rochlen AB (1999). Measuring attitudes regarding bisexuality in lesbian, gay male, and heterosexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 353–369. 10.1037/0022-0167.46.3.353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molina Y, Marquez JH, Logan DE, Leeson CJ, Balsam KF, & Kaysen DL (2015). Current intimate relationship status, depression, and alcohol use among bisexual women: The mediating roles of bisexual-specific minority stressors. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 73, 43–57. 10.1007/s11199-015-0483-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Mohr JJ, Worthington RL, & Fassinger RE (2009). Counseling psychology research on sexual (orientation) minority issues: Conceptual and methodological challenges and opportunities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 5–22. 10.1037/a0014572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulick PS, & Wright LW Jr. (2002). Examining the existence of biphobia in the heterosexual and homosexual populations. Journal of Bisexuality, 2, 45–64. 10.1300/J159v02n04_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs R. (1996). Biphobia: It goes more than two ways. In Firestein BA (Ed.), Bisexuality: The psychology and politics of an invisible minority (pp. 217–239). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G, & Chandler J. (2014). Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 184–188. 10.1177/0963721414531598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G, Chandler J, & Ipeirotis P. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP (1984). The bisexual identity: An idea without social recognition. Journal of Homosexuality, 9, 45–63. 10.1300/J082v09n02_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Smith NG, Mohr JJ, & Ross LE (2014). Measuring dimensions of bisexual identity: Initial development of the bisexual identity inventory. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 452–460. 10.1037/sgd0000069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Horne SG, Herbitter C, Maroney MR, & Levitt HM (2017). Differences across contexts: Minority stress and interpersonal relationships for lesbian, gay, and bisexual women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41, 8–19. 10.1177/0361684316655964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rich A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5, 631–660. 10.1086/493756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TS, Horne SG, & Hoyt WT (2015). Between a gay and a straight place: Bisexual individuals’ experiences with monosexism. Journal of Bisexuality, 15, 554–569. 10.1080/15299716.2015.1111183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, Dobinson C, & Eady A. (2010). Perceived determinants of mental health for bisexual people: A qualitative examination. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 496–502. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust PC (2003). Monogamy and polyamory: Relationship issues for bisexuals. In Garnets LD & Kimmel DC (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences (pp. 475–496). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets RL., & Mohr JJ. (2009). Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 152–163. 10.1037/0022-0167.56.1.152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding LR, & Peplau LA (1997). The unfaithful lover: Heterosexuals’ perceptions of bisexuals and their relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 611–625. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00134.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber GN (2008). Using to numb the pain: Substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30, 31–48. 10.17744/mehc.30.1.2585916185422570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthen MGF (2013). An argument for separate analyses of attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual men, bisexual women, MtF and FtM transgender individuals. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 68, 703–723. 10.1007/s11199-012-0155-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yost MR, & Thomas GD (2012). Gender and binegativity: Men’s and women’s attitudes toward male and female bisexuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 691–702. 10.1007/s10508-011-9767-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]