Abstract

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a significant global cause of mortality, necessitating the exploration of innovative treatments against the condition. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) such as sacubitril/valsartan have demonstrated promise in managing acute heart failure (HF). However, despite favorable evidence from clinical trials for the use of sacubitril/valsartan in AMI, its overall efficacy remains a subject of debate. Hence, we conducted this review and meta-analysis, by adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and aligned with European Society of Cardiology recommendations, to compare sacubitril/valsartan with traditional ACEI/ARB treatments for AMI. We employed Review Manager 5.4 for statistical analysis, the Risk of Bias Tool 2.0 was utilized for quality assessment, and publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this meta-analysis. Our findings revealed that participants treated with sacubitril experienced significantly improved outcomes in terms of HF (OR=0.79; 95% CI: 0.66-0.95; p=0.01; I2=23%), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels (MD = -1.58; 95% CI: -1.78 to -1.37, p<0.00001; I2=97%), and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (OR=0.84; 95% CI: 0.72-0.99; p=0.03; I2=44%). However, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (MD=3.68; 95% CI: 3.35-4.01, p<0.00001; I2=71%) showed greater improvement in the control group compared to the experimental group.

Our meta-analysis suggests that sacubitril offers a favorable balance between safety and effectiveness. Sacubitril significantly improved outcomes in terms of HF, MACE, and NT-proBNP levels when compared to the control group. However, improvement in LVEF was notably higher in the control group over the sacubitril/valsartan group.

Keywords: randomized controlled trials, meta-analysis, acute myocardial infarction, sacubitril/valsartan, early use, efficacy, safety

Introduction and background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), commonly known as a heart attack, arises from the total occlusion of a coronary artery, halting blood supply to cardiomyocytes or due to demand ischemia in a non-obstructed coronary artery [1]. Myocardial ischemia, an oxygen supply-demand imbalance, precedes MI and is diagnosed based on patient history, ECG, and elevated biomarkers. The symptoms include chest, upper limb, mandibular, or epigastric discomfort, with dyspnea and exhaustion [2]. Retrosternal chest pain, feeling like pressure, may occur intermittently or persistently, radiating to the left shoulder, neck, or upper extremities [3]. AMI is associated with the loss of around one million lives in the United States annually, with a global impact affecting approximately three million individuals [4]. Despite notable advancements in therapy, AMI continues to be a prominent cause of mortality [5].

The main objective of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is to improve blood flow to the ischemic area and relieve constriction or blockage of the coronary artery [6]. The efficacy of this intervention in managing AMI has been recognized, based on its ability to target coronary artery stenosis, chest discomfort, and related clinical symptoms [7-9]. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that there is a high incidence of postoperative problems, such as stent thrombosis and the need for target lesion blood transport reconstruction, which have been associated with increased death rates [10,11]. Also, left ventricular dysfunction is a prominent contributor to mortality among hospitalized patients, regardless of the patient population, especially in cases where initial PCI revascularization is unsuccessful [12].

Advancements in medical treatment have led to a significant reduction in overall and cardiovascular mortality rates, along with reduced hospitalizations for heart failure (HF) and other causes [13]. However, heart dysfunction after surgery persists despite technical advances. Studies in the literature have highlighted the advantages associated with the utilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEIs/ARBs) to enhance patient outcomes [14-17]. ACEIs have demonstrated efficacy in improving the survival rates of patients with congestive HF and asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction following MI. In addition, the aforementioned interventions have served to reduce the intensity and frequency of MIs as evidenced by several scholarly sources [18-20]. According to a seminal study conducted in 1986, the timely administration of intravenous lytic medicines to individuals experiencing MI resulted in a significant (50%) decrease in mortality rates [21]. This gave rise to the notion of "the golden hour," which posits that prompt thrombolysis could potentially avert mortality. Rapid revascularization techniques have been shown to provide substantial benefits for individuals diagnosed with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [22].

A better understanding of the mechanisms that underlie HF and cardiac remodeling has facilitated the development of innovative therapeutic strategies. The advent of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) represents a noteworthy advancement in the field [23,24]. Regulatory approval has been granted to sacubitril/valsartan, which is the pioneering drug within its respective category. Sacubitril is classified as a pro-drug that, upon undergoing activation, functions as a neprilysin inhibitor. The mechanism of action involves the inhibition of neprilysin, impeding the degradation of natriuretic peptides. Consequently, this results in an extended duration of the beneficial effects exerted by these peptides [25]. In the context of HF therapy, it is advisable to consider the utilization of sacubitril/valsartan as an alternative to ACEIs or ARBs. This recommendation is made in conjunction with the concurrent administration of other frequently prescribed medications such as beta-blockers and aldosterone antagonists [9,26]. Research has provided evidence that sacubitril-valsartan outperforms ARBs in terms of lowering HF exacerbations that result in hospitalizations or urgent ambulatory visits. Additionally, there is a positive correlation between a lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and greater rates of survival [23].

Although clinical trials have demonstrated potential in the early administration of sacubitril/valsartan for AMI, there exists a variety of viewpoints regarding its overall effectiveness. In light of this, to create a strong scientific basis for its use, a comprehensive analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted to specifically investigate the effects of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with AMI. The primary objective of this analysis was to provide practical guidance for the utilization of sacubitril/valsartan in the treatment of AMI. This meta-analysis thoroughly examined RCTs on early sacubitril/valsartan administration in AMI. Our findings strongly support its efficacy, revealing benefits such as lowered heart rate, improved ejection fraction, reduced N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and minimized major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in AMI patients with HF. Our findings underscore that initiating sacubitril/valsartan promptly after AMI is both safe and effective.

Review

Methods

This meta-analysis was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [27].

Search Strategy

Two authors conducted searches involving several databases, including Cochrane, PubMed, Embase, and Medline for articles, spanning the time from their initiation till October 5, 2023. The database searches were conducted by using a combination of the following terms: "Myocardial Infarction, Neprilysin Inhibitor, LCZ696, Sacubitril/Valsartan, and Entresto." There were no limitations placed on the use of language or any temporal constraints. The search approach is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Search strategy*.

| Database | Query | Search details | Number of patients |

| PubMed | Myocardial Infarction AND Neprilysin Inhibitor OR LCZ696 OR Sacubitril/Valsartan OR Entresto | (("myocardial infarction"[MeSH Terms] OR ("myocardial"[All Fields] AND "infarction"[All Fields]) OR "myocardial infarction"[All Fields]) AND (("neprilysin"[MeSH Terms] OR "neprilysin"[All Fields] OR "neprilysins"[All Fields]) AND ("antagonists and inhibitors"[MeSH Subheading] OR ("antagonists"[All Fields] AND "inhibitors"[All Fields]) OR "antagonists and inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "inhibitor"[All Fields] OR "inhibitor s"[All Fields]))) OR ("sacubitril and valsartan sodium hydrate drug combination"[Supplementary Concept] OR "sacubitril and valsartan sodium hydrate drug combination"[All Fields] OR "lcz696"[All Fields]) OR ("sacubitril and valsartan sodium hydrate drug combination"[Supplementary Concept] OR "sacubitril and valsartan sodium hydrate drug combination"[All Fields] OR "sacubitril valsartan"[All Fields]) OR ("sacubitril and valsartan sodium hydrate drug combination"[Supplementary Concept] OR "sacubitril and valsartan sodium hydrate drug combination"[All Fields] OR "entresto"[All Fields] OR "sacubitril"[Supplementary Concept] OR "sacubitril"[All Fields] OR "valsartan"[MeSH Terms] OR "valsartan"[All Fields]) | 5,882 |

| Embase | Neprilysin Inhibitor OR LCZ696 OR Sacubitril/Valsartan OR Entresto | 903 | |

| Cochrane Library | Neprilysin Inhibitor OR LCZ696 OR Sacubitril/Valsartan OR Entresto | 434 | |

| SCOPUS | Neprilysin Inhibitor OR LCZ696 OR Sacubitril/Valsartan OR Entresto | 783 | |

| Google Scholar | Neprilysin Inhibitor OR LCZ696 OR Sacubitril/Valsartan OR Entresto | 1,423 |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) studies including patients with MI, (II) studies including patients administered sacubitril/valsartan in the experimental group, (III) RCTs, and (IV) studies that provide outcomes of interest. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) non-RCTs, (II) studies that do not provide efficacy-related data, and (III) in cases where multiple publications on the same clinical research were found, only the publication with the most thorough data were considered eligible.

Data Extraction and Outcome Measures

The data were extracted by two researchers. The extracted information included the study title, author, publication year, baseline characteristics of the subjects (gender and age), source of research subjects, and sample size. The primary outcomes of our study were MACE and HF, while secondary outcomes included LVEF and NT-proBNP.

Quality Assessment and Statistical Analysis

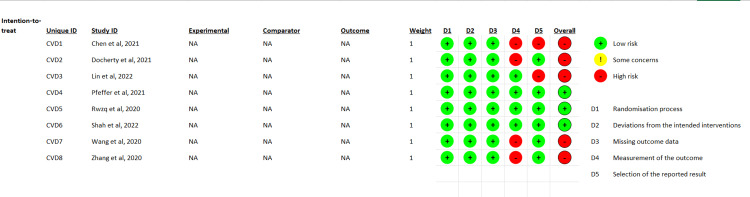

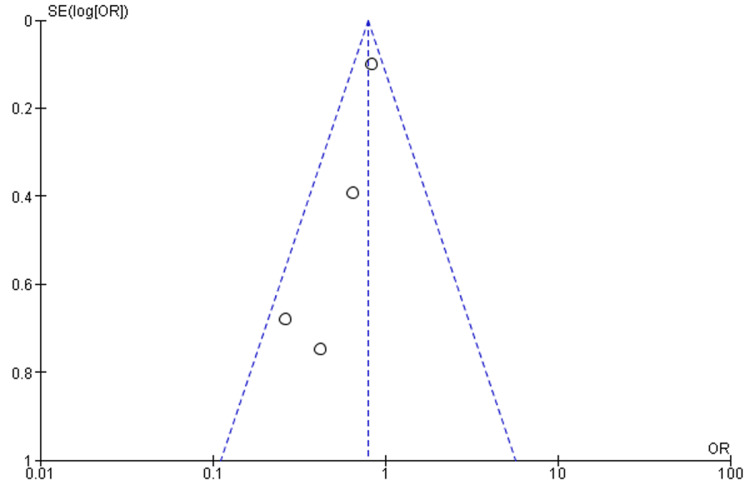

One researcher was tasked with using the Risk of Bias Tool 2 (ROB 2.0) to assess quality (Figure 1). Forest plots and statistical analysis were completed using Review Manager 5.4. The pooled effect size was calculated using forest plots by employing either random or fixed effects. The researchers employed a fixed-effects model in cases when the value of I2 was below 50%. Conversely, a random-effects model was utilized when I2 exceeded 50%. The evaluation of publication bias was conducted by employing a funnel plot, as depicted in Figure 2. The determination of the significance threshold (p<0.05) was made based on the Z value.

Figure 1. Quality assessment.

Figure 2. Funnel plot for the outcome of HF.

HF: heart failure

Results

Literature Search Results

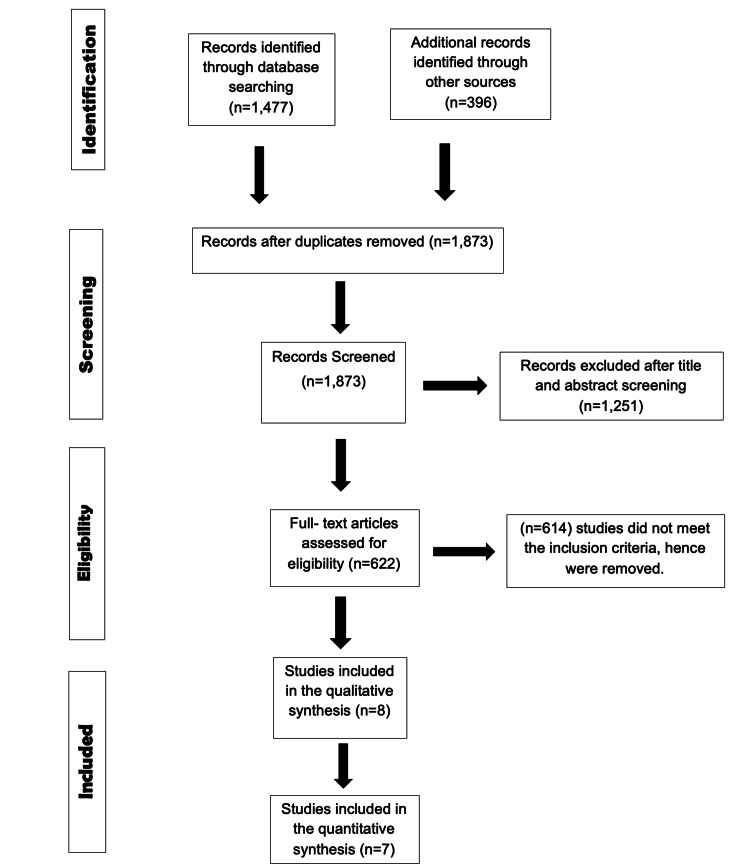

Figure 3 presents the PRISMA flow chart, which visually outlines the extensive screening procedure. After eliminating duplicate entries and implementing filters, a total of eight papers were selected for the final analysis.

Figure 3. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the selection of studies.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Baseline Characteristics

Table 2 provides an overview of the characteristics of the included studies and the demographic information of the participants. The studies involved 6,981 participants, with a mean age of 59.4 years in the experimental group and 59.2 years in the control group. The experimental group consisted of 76.65% males.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the included studies*.

| Author | Year | Disease | Sample size | Age, years, mean ±SD | Sex, male/total | Intervention | ||||

| Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | |||

| Chen et al. [45] | 2021 | Acute myocardial infarction | 42 | 39 | 51.28 ±6.27 | 51.3 ±6.21 | 27/42 | 24/39 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Bisoprolol |

| Docherty et al. [46] | 2021 | Myocardial infarction | 47 | 46 | 61.8 ±10.6 | 59.7 ±10.1 | 42/47 | 43/46 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Valsartan |

| Rezq et al. [47] | 2020 | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 100 | 100 | 52 ±9.2 | 57 ±11.6 | 86/100 | 88/100 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Ramipril |

| Wang et al. [44] | 2020 | Acute anterior wall myocardial infarction | 68 | 69 | 59.13 +7.15 | 60.56 ±7.62 | 52/68 | 54/69 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Enalapril |

| Zhang et al. [49] | 2020 | ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 79 | 77 | 60.3 ±11.7 | 60 ±10.9 | 59/79 | 55/77 | Sacubitril/valsartan | ACEI |

| Pfeffer et al. [50] | 2021 | Myocardial infarction | 2,830 | 2,831 | 64.0 ±11.6 | 63.5 ±11.4 | 2167/2830 | 2131/2831 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Ramipril |

| Lin et al. [51] | 2022 | Acute anterior wall ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 55 | 54 | 61.38 ±12.31 | 59.74 ±11.53 | 49/55 | 47/54 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Valsartan |

| Shah et al. [52] | 2022 | Acute myocardial infarction | 279 | 265 | 65.0 ±11.9 | 62.3 ±11.2 | 201/279 | 201/265 | Sacubitril/valsartan | Ramipril |

Results of the Meta-Analysis

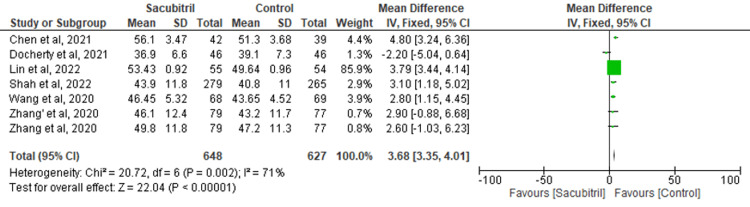

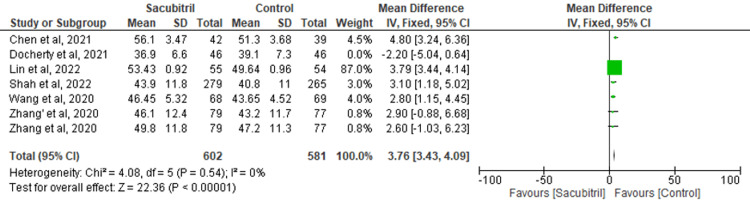

LVEF: Data from six studies were pooled to evaluate the effect of sacubitril on the outcome of LVEF. It was found that there was a significant improvement in LVEF in the control group versus the experimental group (MD=3.68; 95% CI: 3.35-4.01, p<0.00001; I2=71%) (Figure 4). To address the heterogeneity in the results, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Upon excluding the study by Docherty et al., the results remained significant (MD=3.76; 95% CI: 3.43-4.09, p<0.00001), but the heterogeneity lowered to 0% (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Forest plot for the outcome of LVEF.

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

Figure 5. Sensitivity analysis for the outcome of LVEF.

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

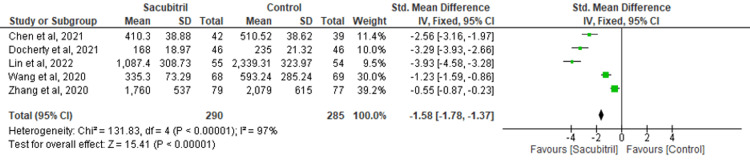

NT-proBNP: Five of the included studies assessed the effectiveness of sacubitril versus control for the outcome of NT-proBNP. The outcome of NT-proBNP was improved in the group of sacubitril as compared to the control group (MD = -1.58; 95% CI: -1.78 to -1.37, p<0.00001; I2=97%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Forest plot for the outcome of NT-proBNP.

NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide

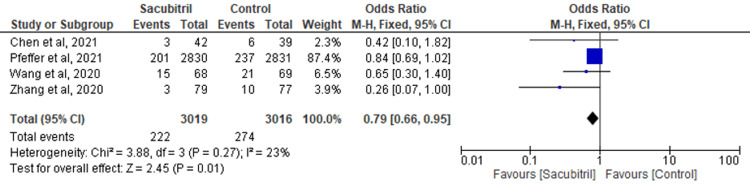

HF: The findings of four RCTs were combined to evaluate the outcome of HF. The results revealed that the participants taking sacubitril had a lower incidence of HF when compared to the control group (OR=0.79; 95% CI: 0.66-0.95; p=0.01; I2=23%) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Forest plot for the outcome of HF.

HF: heart failure

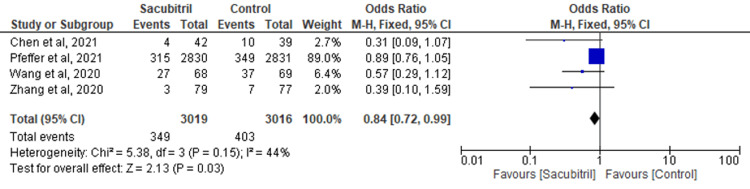

MACE: Four studies examined the efficacy of sacubitril in comparison to a control group concerning the occurrence of MACE as the outcome. The findings indicated that individuals who received sacubitril experienced a reduced occurrence of MACE in comparison to the control group (OR=0.84; 95% CI: 0.72-0.99; p=0.03; I2=44%) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Forest plot for the outcome of MACE.

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events

Discussion

In determining the impact of sacubitril on HF after MI, our meta-analysis revealed that the drug was successful in enhancing the outcomes of HF, NT-proBNP, and MACE, yielding significant results when compared to the control group. However, the improvement in the outcome of LVEF was greater in the control group versus the experimental group. A sensitivity analysis was performed to account for the heterogeneity in LVEF outcome results, and it was found that the results remained consistent, and heterogeneity was significantly reduced.

Several previous meta-analyses have been conducted on the effect of sacubitril on HF outcomes. A study by Liu et al. [28] reported similar results to our findings. This study highlighted the effectiveness of sacubitril in improving the outcome of HF (MD=0.49, 95% CI: 0.27-0.89, I2=0%, p=0.02), NT-proBNP (MD = -1.33%, 95% CI: -1.54 to -1.12, I2=96%, p<0.00001), and MACE (MD=0.49, 95% CI: 0.27-0.89, I2=0%, P=0.02). However, this research included only five RCTs, while our study encompassed seven RCTs, thereby reinforcing the strength of the evidence presented in this study. Xiong et al. [29] showed significant improvement in NT-proBNP (WMD = -310.23, 95% CI: -385.89 to -234.57, p<0.001), which aligns with the results of our meta-analysis. However, this study showed an improvement in LVEF (WMD=5.49, 95% CI: 3.62-7.36, p<0.001) in the sacubitril group, whereas our findings favored the control group. In line with our results, Zhao et al. [30] demonstrated a reduction in MACE among participants taking sacubitril (RR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.46-0.82, P=0.001). In contrast with our findings, a study by Nie et al. [31] failed to show any significant difference between ACEIs and sacubitril for the outcomes of NT-proBNP (WMD = -301.16; 95% CI: -602.77-0.437; p=0.05) and LVEF (WMD: 1.49; 95% CI: -1.33-4.32; p=0.30).

The pathophysiology of HF involves a maladaptive response characterized by an activated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to vasoconstriction, hypertension, increased aldosterone levels, heightened sympathetic tone, and ultimately, cardiac remodeling, all of which contribute to the progression of the disease [32]. In addition to impeding neprilysin, sacubitril concurrently blocks the AT1 receptor when combined with valsartan. Together, these two effects decrease aldosterone and increase natriuretic peptides. These results support the use of sacubitril/valsartan to control fluid balance in treating cardiovascular illnesses [33]. Sacubitril's enhanced NPs improve hemodynamics when the ejection fraction is lower. They lower levels of renin, aldosterone, and vasopressin, increase natriuresis, and inhibit the sympathetic nervous system. They also lower ventricular filling pressures in severe heart failure, primarily affecting preload without altering systemic vascular resistances [34]. To lower afterload and raise LVEF, combining neprilysin inhibition with RAAS inhibition is recommended.

Heart-secreted neuroendocrine hormones - BNP and NT-proBNP - have proven to be useful markers for the diagnosis, management, and prognosis of HF patients [35,36]. The measurement of the size of MI, the therapeutic effect of myocardial reperfusion, and the anticipation of myocardial remodeling are all significantly influenced by NT-proBNP [37]. Changes in NT-proBNP levels have been shown to correlate highly with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). When it comes to lowering NT-proBNP, sacubitril/valsartan is noticeably better than enalapril, highlighting its potential to lower morbidity and mortality. The fact that NT-proBNP is still a valid indicator of HF severity in the presence of neprilysin inhibition highlights the significance of this biomarker in determining the efficacy of treatment [38].

The main pathological cardiac remodeling is caused by the excessive stimulation of RAAS and sympathetic nerves [10,11]. Sacubitril inhibits RAAS by improving glomerular filtration rate and renal blood flow. Additionally, it provides anti-hypertrophic and anti-fibrotic benefits [39] and volume reduction [40]. MACE in patients with AMI after PCI poses a risk to the quality of life and health. A precise prediction of the risk of MACE following PCI enables the early implementation of appropriate measures for control and prevention, thereby reducing the occurrence of MACE [41].

The adverse effects include angioedema, renal failure, hyperkalemia, hypotension, and cough [42]. Sacubitril/valsartan increases hypotension and symptomatic hypotension. However, sacubitril/valsartan is associated with a reduced risk of cough and potassium/creatinine increase than enalapril. Angioedema has also been found to be more common with sacubitril/valsartan than enalapril [43]. Sacubitril/valsartan failed to improve LVEF in our study, and this could be attributed to study heterogeneity and publication bias. Understanding these limitations is crucial in evaluating the effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in enhancing LVEF and tailoring treatment strategies for optimal outcomes.

Sacubitril's use in the treatment of HF has significant implications for both clinical practice and research. Sacubitril has been demonstrated to enhance several important HF-related parameters, making it a compelling therapeutic alternative. Firstly, it has been effective in raising NT-proBNP levels, an important biomarker for the severity and prognosis of HF. Improved outcomes and enhanced heart function are indicated by lower NT-proBNP levels. Furthermore, sacubitril has demonstrated its capacity to raise LVEF, a critical measure of heart health. Sacubitril improves cardiac function and HF patients' overall quality of life [44] by raising LVEF. Additionally, sacubitril therapy's correlation with a decrease in MACE presents a significant benefit in terms of patient safety and long-term results. This finding highlights sacubitril's ability to lower the likelihood of adverse effects, including cardiovascular mortality, hospitalizations, and other complications.

From a scientific perspective, research on sacubitril's effect on HF outcomes advances both our knowledge of its mechanisms and the creation of more potent HF medicines. The usefulness of sacubitril in contemporary HF care is further supported by the consistent findings across several clinical investigations. However, further studies are required to fully understand the subtleties of its effects, long-term advantages, and possible combinations with other therapeutic approaches. To conclude, sacubitril's beneficial effects on NT-proBNP, LVEF, HF, and MACE signify a hopeful advancement in cardiovascular medicine that could greatly enhance the quality of life for patients who suffer from HF and improve our understanding of the treatment of HF.

This meta-analysis has a few limitations. The research included in the analysis exhibited a generally moderate degree of quality, and the sample sizes were considered inadequate. Certain papers did not explicitly mention the utilization of certain randomized procedures, while others failed to provide precise details regarding the pharmacological specifics pertaining to Western conventional drug treatment. Furthermore, the publications exhibited clinical heterogeneity due to variations in the age groups of the research participants and the coexistence of comorbidities. The funnel plot in our meta-analysis showed an element of publication bias. This potential bias could impact the robustness and generalizability of our findings. Our dedication to a responsible and thorough research approach is reinforced by our transparency in identifying limitations. Readers must take these elements into account while evaluating the data.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, the use of sacubitril appears to offer a favorable balance between safety and effectiveness. The outcomes of HF, MACE, and NT-proBNP showed significant improvement with sacubitril use when compared to the control group. However, the improvement in LVEF was significantly greater in the control group.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Muhammad Usama, Abdullah -, Majid Rashid, Cuauhtemoc Jeffrey Soto, Ghazala S. Virk, Favour C. Mekowulu, Sandipkumar S. Chaudhari, Saima Batool

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Muhammad Usama, Abdullah -, Majid Rashid, Cuauhtemoc Jeffrey Soto, Ghazala S. Virk, Favour C. Mekowulu, Sandipkumar S. Chaudhari, Saima Batool

Drafting of the manuscript: Muhammad Usama, Abdullah -, Majid Rashid, Cuauhtemoc Jeffrey Soto, Ghazala S. Virk, Favour C. Mekowulu, Sandipkumar S. Chaudhari, Saima Batool

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Muhammad Usama, Abdullah -, Majid Rashid, Cuauhtemoc Jeffrey Soto, Ghazala S. Virk, Favour C. Mekowulu, Sandipkumar S. Chaudhari, Saima Batool

Supervision: Muhammad Usama, Abdullah -, Majid Rashid, Cuauhtemoc Jeffrey Soto, Favour C. Mekowulu, Sandipkumar S. Chaudhari

References

- 1.Wu JC. Essential Echocardiography. Vol. 2. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. Acute myocardial infarction; pp. 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018) (Article in Polish) Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Kardiol Pol. 2018;76:1383–1415. doi: 10.5603/KP.2018.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction: 2008-09 revision. Mendis S, Thygesen K, Kuulasmaa K, Giampaoli S, Mähönen M, Ngu Blackett K, Lisheng L. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:139–146. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Impact of delay to reperfusion on reperfusion success, infarct size, and clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the INFUSE-AMI Trial (INFUSE-Anterior Myocardial Infarction) Guerchicoff A, Brener SJ, Maehara A, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.01.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Awareness of Myocardial Infarction Symptoms in General Population. Kim SJ. Korean Circ J. 2021;51:997–1000. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad M, Mehta P, Reddivari AKR, Mungee S. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure and end-stage renal insufficiency. Heyse A, Manhaeghe L, Mahieu E, Vanfraechem C, Van Durme F. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6:1331–1333. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Efficacy and safety of different doses of tirofiban combined with ticagrelor on diabetic patients with AMI receiving in emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) Liu Y, Liu H, Hao Z, et al. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4565334/ Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:11360–11369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Practical guidance on the use of sacubitril/valsartan for heart failure. Sauer AJ, Cole R, Jensen BC, Pal J, Sharma N, Yehya A, Vader J. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s10741-018-9757-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temporal trends in the prevalence and outcomes of geriatric patients with acute myocardial infarction in Japan-a report from the Miyagi AMI Registry Study. Sato K, Takahashi J, Hao K, et al. J Cardiol. 2020;75:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacubitril/valsartan across the spectrum of ejection fraction in heart failure. Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, L Claggett B, et al. Circulation. 2020;141:352–361. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Management of acute left ventricular dysfunction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction. Saia F, Grigioni F, Marzocchi A, Branzi A. Am Heart J. 2010;160:0–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Incremental benefit of drug therapies for chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis. Komajda M, Böhm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Tavazzi L, Pannaux M, Swedberg K. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1315–1322. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effects of sacubitril/valsartan versus irbesartan in patients with chronic kidney disease. Haynes R, Judge PK, Staplin N, et al. Circulation. 2018;138:1505–1514. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Effects of sacubitril-valsartan versus valsartan in women compared with men with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: insights from PARAGON-HF. McMurray JJ, Jackson AM, Lam CS, et al. Circulation. 2020;141:338–351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.B-type natriuretic peptide during treatment with sacubitril/valsartan: the PARADIGM-HF trial. Myhre PL, Vaduganathan M, Claggett B, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1264–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Effect of sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on glycaemic control in patients with heart failure and diabetes: a post-hoc analysis from the PARADIGM-HF trial. Seferovic JP, Claggett B, Seidelmann SB, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:333–340. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30087-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS) N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1429–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Lancet. 1993;342:821–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moyé LA, et al. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2868337/ Lancet. 1986;1:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ten years of benefit from a one-hour intervention. Califf RM. Circulation. 1998;98:2649–2651. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.24.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, et al. Circulation. 2015;131:54–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Anand IS, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.In brief: sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) expanded indication. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33976096/ Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021;63:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Exploring the Food and Drug Administration's review and approval of Entresto (sacubitril/valsartan) Eadie AL, Brunt KR, Herder M. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2021;9:0. doi: 10.1002/prp2.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. BMJ. 2021;372:0. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Effects and safety of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Liu L, Ding X, Han Y, Lv J. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:7840852. doi: 10.1155/2022/7840852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.The benefits of sacubitril-valsartan in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Xiong B, Nie D, Qian J, et al. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:4852–4862. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efficacy and safety of early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in patients after acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. Zhao J, Zeng Y, Shen X. Clin Cardiol. 2021;44:1354–1359. doi: 10.1002/clc.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The effect of sacubitril-valsartan in heart failure patients with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. Nie D, Xiong B, Qian J, Rong S, Yao Y, Huang J. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30:683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Titration and tolerability of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with heart failure in clinical practice. Du AX, Westerhout CM, McAlister FA, et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2019;73:149–154. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Can angiotensin II type 2 receptors have deleterious effects in cardiovascular disease? Implications for therapeutic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Lévy BI. Circulation. 2004;109:8–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096609.73772.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Combined angiotensin receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition. Hubers SA, Brown NJ. Circulation. 2016;133:1115–1124. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacubitril/valsartan: neprilysin inhibition 5 years after PARADIGM-HF. Docherty KF, Vaduganathan M, Solomon SD, McMurray JJ. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:800–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chronic kidney disease, heart failure and neprilysin inhibition. Haynes R, Zhu D, Judge PK, Herrington WG, Kalra PA, Baigent C. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:558–564. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The neprilysin pathway in heart failure: a review and guide on the use of sacubitril/valsartan. Jhund PS, McMurray JJ. Heart. 2016;102:1342–1347. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sacubitril/valsartan: a novel cardiovascular combination agent. Sible AM, Nawarskas JJ, Alajajian D, Anderson JR. Cardiol Rev. 2016;24:41–47. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association between atrial natriuretic peptide and cyclic GMP in hypertension and in chronic renal failure. Sagnella GA, Saggar-Malik AK, Buckley MG, Markandu ND, Eastwood JB, MacGregor GA. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;275:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The renal and cardiovascular effects of natriuretic peptides. Wong PC, Guo J, Zhang A. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41:179–185. doi: 10.1152/advan.00177.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The role of sacubitril/valsartan in the treatment of chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in hypertensive patients with comorbidities: from clinical trials to real-world settings. Mazza A, Townsend DM, Torin G, et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130:110596. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicolas D, Kerndt CC, Reed M. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. Vol. 7. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2016. Sacubitril-Valsartan; pp. 278–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Initiation, continuation, switching, and withdrawal of heart failure medical therapies during hospitalization. Bhagat AA, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC, Butler J. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on resistant hypertension and myocardial work in hemodialysis patients. Wang B, Wang GH, Ding XX, Tang HX, Zheng J, Liu BC, Zhang XL. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2022;24:300–308. doi: 10.1111/jch.14422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Study on the application effect of bisoprolol combined with sacubitril valsartan sodium tablets in the cardiac rehabilitation of patients with acute myocardial infarction combined with left heart failure after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) Chen C, Wu X, Li Y, Peng Y. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:5455–5461. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rationale and methods of a randomized trial evaluating the effect of neprilysin inhibition on left ventricular remodelling. Docherty KF, Campbell RT, Brooksbank KJ, et al. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:129–138. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Comparison of the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan versus ramipril in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Rezq A, Saad M, El Nozahi M. Am J Cardiol. 2021;143:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sex differences in clinical characteristics and outcomes after myocardial infarction with low ejection fraction: insights from PARADISE-MI. Wang X, Jering KS, Cikes M, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:0. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.028942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benefits of early administration of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Zhang Y, Wu Y, Zhang K, Ke Z, Hu P, Jin D. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:427–431. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibition in acute myocardial infarction. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Lewis EF, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1845–1855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The value of sacubitril/valsartan in acute anterior wall ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction before emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. Lin G, Chen W, Wu M, Dai C, Xu K. Cardiology. 2022;147:479–485. doi: 10.1159/000527357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Impact of sacubitril/valsartan compared with ramipril on cardiac structure and function after acute myocardial infarction: the PARADISE-MI echocardiographic substudy. Shah AM, Claggett B, Prasad N, et al. Circulation. 2022;146:1067–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]