Abstract

Background:

The complexity of research informed consent forms makes it hard for potential study participants to make informed consent decisions. In response, new rules for human research protection require informed consent forms to begin with a key information section that potential study participants can read and understand. This research study builds on exiting guidance on how to write research key information using plain language.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to develop a valid and reliable tool to evaluate and improve the readability, understandability, and actionability of the key information section on research informed consent forms.

Methods:

We developed an initial list of measures to include on the tool through literature review; established face and content validity of measures with expert input; conducted four rounds of reliability testing with four groups of reviewers; and established construct validity with potential research participants.

Key Results:

We identified 87 candidate measures via literature review. After expert review, we included 23 items on the initial tool. Twenty-four raters conducted 4 rounds of reliability testing on 10 informed consent forms. After each round, we revised or eliminated items to improve agreement. In the final round of testing, 18 items demonstrated substantial inter-rater agreement per Fleiss' Kappa (average = .73) and Gwet's AC1 (average = .77). Intra-rater agreement was substantial per Cohen's Kappa (average = .74) and almost perfect per Gwet's AC1 (average = 0.84). Focus group feedback (N = 16) provided evidence suggesting key information was easy to read when rated as such by the Readability, Understandability and Actionability of Key Information (RUAKI) Indicator.

Conclusion:

The RUAKI Indicator is an 18-item tool with evidence of validity and reliability investigators can use to write the key information section on their informed consent forms that potential study participants can read, understand, and act on to make informed decisions. [HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2024;8(1):e29–e37.]

Plain language summary

Plain Language Summary: Research informed consent forms describe key information about research studies. People need this information to decide if they want to be in a study or not. A helpful form begins with a short, easy-to-read key information section. This study created a tool researchers can use to write the key information about their research people can read, understand, and use.

Informed consent is essential to the voluntary participation of human participants in research. The informed consent form (ICF) documents the essential elements of the consent conversation including research goals, expected procedures and risks, and other information a potential research participant needs to make an informed consent decision. However, in recent years, the addition of mandatory scientific content and legal language, and growing length has made the ICF a barrier to study participation (Emanuel & Boyle, 2021; Grant, 2021).

In response to the increasing complexity and length of informed consent documentation, the Health and Human Services Office of Human Research Protection added a new requirement to the 2018 Common Rule, stipulating that informed consent forms begin with “a concise and focused presentation of the key information that is most likely to assist prospective subjects in understanding the reasons why one might or might not want to participate in the research” and that it “must be organized and presented in a way that facilitates comprehension” (Office for Human Research Protections, 2021). The Secretary's Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) recommended empirical research be conducted in light of this new consent requirement to guide the writing of this new key information section to ensure its goals are met (Office for Human Research Protections, 2018). This research study builds on SACHRP and other guidance on how to present research key information in a manner that “facilitate[s] comprehension,” and measure subsequent improvement (Porter et al., 2021).

To make informed consent forms (ICFs) easier to read, many Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) require investigators to develop documents written at the 8th grade reading level. Yet, numerous studies document that research ICFs are frequently written at reading grade levels that far exceed readers' abilities (Hadden et al., 2017; Larson et al., 2015; Paasche-Orlow et al., 2003; Sherlock & Brownie, 2014; Tamariz et al., 2013). Consent forms that are hard to read impede access to the information and the opportunity to participate in clinical research and increase the risk of uninformed consent (Afolabi et al, 2018; Grant, 2021; Perrenoud et al., 2015; Porter et al., 2021).

Plain language writing reduces complexity and makes a written document easy to read. The approach applies language factors such as use of familiar words and active voice; and design features including short “chunks” of text with bold, informative headers (Plain Language Action and Information Network, n.d.). Readability formulas assess the reading grade level of written documents (Ley & Florio, 1996; Tekfi, 1987). However, they do not take into consideration many of the plain language writing and design principles that influence a document's reading ease or difficulty (Begeny & Greene, 2013; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, n.d.; Jindal & MacDermid, 2017; Redish, 2000).

Health literacy is an individual's ability to find, understand, and act on health information to make informed decisions and is dependent on the complexity of the information presented (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). A systematic review examining health literacy and informed consent practices concluded that low health literacy and the complexity of ICFs make it less likely people will participate in informed consent decision making. This systematic review also highlighted a gap in the informed consent process for minority and underserved populations who are underrepresented in clinical research and recommended practices such as simplification of written documents, clarification of verbal exchanges, assessment of understanding, and use of additional resources to aid in the communication process such as multimedia and computerized formats (Perrenoud et al., 2015).

Tools to reduce complexity of written health information adopt a checklist approach to apply criteria which leverage plain language principles to promote knowledge and self-action. The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) assesses understandability and actionability of print and audiovisual patient education materials for use in clinical practice (Shoemaker et al., 2014). Following iterative development, the final PEMAT includes 26 items that showed substantial agreement among users (Average Kappa = 0.57, Average Gwet's AC1 = 0.74). PEMAT scores correlated with consumer-testing responses. Similarly, the Health Literacy INDEX assesses the health literacy demands of public health education materials (Kaphingst et al., 2012). The final tool includes 63 items that demonstrated inter-rater agreement of 90% or better for half of the items, and above 80% for the remainder. Index scores correlated with material review ratings from 12 health literacy experts (r = 0.89, p < .0001).

To date, we are aware of no valid and reliable tools with criteria to evaluate the reading ease of key information sections required in ICFs. This study addresses that gap and adds to existing knowledge by incorporating previously validated plain language measures with informed consent concepts to improve the reading ease of key information on research consent forms and improve accessibility.

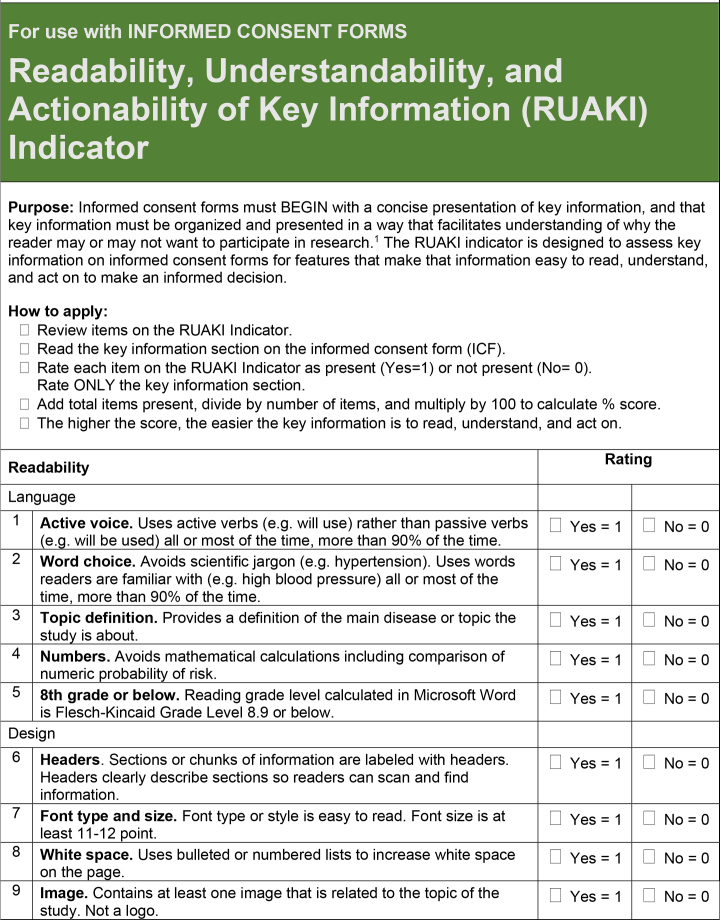

In developing the tool, we defined and measured three constructs of interest: readability, understandability, and actionability (Table 1). We distinguish readability as the ease of obtaining the desired information from the written page. We include the Flesch-Kincaid (Kincaid et al., 1975) as a component measure of readability reflecting sentence complexity, given the wide adoption of grade level as an IRB requirement. We expand the concept of readability to include features of plain language writing and design principles. We define understandability as the presentation of factual information about the study in a way that promotes comprehension. Use of familiar words and simple numeracy facilitate understanding. We define actionability as ease with which the participant can leverage the acquired knowledge to take the next step in the research. Specific instructions or demanded actions to affect participation include signing the consent document to indicate comprehension and consent. The tool development plan was reviewed and determined exempt by the Tufts Health Sciences IRB.

Table 1.

Constructs of Interest: Definitions and Indicators

| Constructs | Definitions | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Readability | Key information on informed consent form is easy to read when:

|

Plain language writing and design items on checklist

|

| Understandability | Key information on informed consent form is understandable when:

|

Key information content items on checklist

|

| Actionability | Key information on informed consent form is actionable when:

|

Action item on checklist |

Methods

Literature Review

We conducted a literature review beginning with a Medline search of articles using the following search terms: health literacy, informed consent, plain language, assessment criteria, tool development, clear communication, clinical research, reading grade level, and readability in October 2019. We restricted our results to English language and included years 2009 to 2019. We identified additional articles from the bibliographies of the selected article. We searched for tool development articles to identify indicators validated in previous studies relevant to each of the constructs: readability, understandability and actionability.

We also reviewed the 2018 Common Rule and SACHRP interpretation of the new key information requirement on informed consent forms to identify content needed by potential clinical research participants to make informed consent decisions (Office for Human Research Protections, 2018).

Expert Review

We refined the list of indicators by soliciting expert opinion and rater experience. We recruited an advisory group of eight experts including health literacy specialists, plain language writers, clinical investigators, institutional review board representatives, and advocates for populations under-represented in research. Expert advisors reviewed and commented on identified indicators' face validity, considering whether the individual indicators represented measurements of readability, understandability, or actionability; and on content validity, considering whether the sum of indicators encompassed all constructs of interest.

Reliability Testing

To create a test set of key information documents on which to establish reliability, the study team extracted key information sections from a convenience sample of research informed consent forms (ICFs) for 10 COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019)–related studies publicly available in full text on www.clinicaltrials.gov. A COVID-19 focus was selected for temporal familiarity. Interventional studies were selected for a greater degree of complexity and heighted associated risks of participation. Each key information section was identified by heading title and extracted without modification, maintaining content, style and format. We recruited raters familiar with the informed consent process with support from the Recruitment and Retention Support Unit at Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI). We conducted four tests of inter-rater reliability. Independent groups of raters for each round of testing were instructed to apply the tool to the test set of key information sections. We assessed Inter-rater reliability by comparing Readability, Understandability and Actionability of Key Information (RUAKI) Indicator scores for each item between each rater, averaging across four key information samples. We measured intra-rater reliability to confirm that raters would apply the tool consistently over time by presenting four of the key information samples twice in the final round of testing, 1 month apart to reduce recall bias. We calculated inter-rater and intra-rater reliability statistics, including percent agreement, Fleiss' Kappa (Fleiss, 1971), Gwet's first-order agreement coefficient (AC1) (Gwet, 2008), and Cohen's Kappa (Cohen, 1960) and collected qualitative comments from reviewers. While Kappa is the most common measure of inter-rater reliability, it can be unstable when responses fall into two diametrically opposed categories (some say strongly no others strongly yes) (Feinstein & Cicchetti, 1990). In this situation, Gwet's AC1 has been shown to be more stable (Gwet, 2008).

The inter-rater reliability of the tool was improved through an iterative process. After each round, we revised or eliminated items in the tool in response to feedback from the raters and according to overall percent agreement, Kappa and Gwet's scores. Kappa and Gwet's AC1, agreement were interpreted as poor (≤0), slight (0.01–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), or almost perfect (0.81–1.00) (Landis & Koch, 1977). To improve agreement, we reviewed, deleted, or made revisions to items with <80% agreement. Ultimately, our goal was for all items to achieve substantial or almost perfect Kappa and Gwet's AC1 agreement.

Construct Validity Testing

We evaluated construct validity through focus group interviews with potential study participants. To generate a test set of key information to be evaluated by focus groups, we extracted and scored the IRB-approved key information section from a recently completed COVID-19–related interventional study selected for convenience. Two researchers (S.K.R., A.K.) independently revised that key information according to the RUAKI tool to improve reading ease, and later compared and combined revised versions. We recorded RUAKI scores for the original key information section and the revised version.

We recruited two focus groups from the Tufts CTSI Stakeholder Expert Panel of community volunteers who agreed to be contacted for Tufts research related purposes including consumer feedback. Participants had to be age 18 years or older and speak English. We reviewed demographics and continued recruitment until the group included people of different ages, genders, races, ethnicities, and education levels.

Participants were asked to review the two versions of the key information (original and revised) sections and complete two surveys prior to attending the focus group. They were instructed to imagine their own potential involvement in the study described by the key information. They received an email 2 weeks prior to the scheduled focus group with a link to review the original IRB-approved key information and fill out a demographic survey. One week later, they received a second email with a link to review the revised key information document and fill out a survey with six questions asking about reading ease or difficulty of the revised version, and five true/false questions to assess understandability. The survey also included the five-part Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) developed by O'Connor (1995). The DCS serves as a global measure of perceived adequacy of consent as it reflects the participant's confidence or strength of conviction in their (imagined) decision to participate or not in the study. Scores range from 0 (no decisional conflict, full confidence in the decision) to 100 (extreme decisional conflict, no confidence in the decision).

The focus groups each met for a single session to reflect on participant experience with clinical research and the informed consent key information provided. The focus group discussions followed a script which included open-ended opinion questions about which key information document was easier to read and why. Focus group discussions were led by a research team member with experience facilitating focus groups (S.K.R.), conducted via Zoom, and recorded. Each focus group participant provided oral consent to be recorded. Three researchers from the study team (S.K.R., I.A.O., A.K.) reviewed the two focus group transcripts and using a grounded theoretical framework, conducted open coding to describe participant experiences related to the reading ease and difficulty of the informed consent key information they reviewed (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Researchers then compared notes to agree upon common themes.

Results

Face and Content Validity

The literature review identified 25 peer-reviewed articles. Five articles described developing a valid and reliable tool to assess the reading ease or difficulty of health-related information (Table A). From the five validity and reliability studies, we identified 32 items relevant to plain language writing principles, 25 items relevant to plain language design principles, and five items relevant to actionability, (Baur & Prue, 2014; Clayton 2009; Kaphingst et al., 2012; Shoemaker et al., 2014). From two sources, we identified 25 items relevant to the identification of the key information a prospective study participant needs to make an informed consent decision (Afolabi et al., 2018; Office for Human Research Protections, 2018).

Table A.

Summary of Articles. Medline search using terms health literacy, informed consent, plain language, assessment criteria, tool development, clear communication, clinical research, reading grade level, and readability, 1999 – 2019. Five articles described developing valid and reliable items to assess reading ease of health-related information.

| Title | Date | Objectives | Design | Results | Conclusion | Full Citation (APA) and Hyperlink |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An adapted instrument to assess informed consent comprehension among youth and parents in rural western Kenya: A validation study | 2018 | To adapt and validate a questionnaire originally developed for assessment of comprehension of consent information in a different cultural and linguistic research setting. | The adaptation process involved development of a questionnaire for each of the three study groups, modelled closely on the previously validated questionnaire. Questionnaires were further reviewed by two bioethicists and developer of original questionnaire for face and content validity. The questionnaire was programmed into an audio computerized format, with translations and back translations in three widely spoken languages by the study participants: Luo, Swahili and English. | Our study demonstrates that cross-cultural adaptation and validation of an informed consent comprehension questionnaire is feasible. However, further research is needed to develop a tool which can estimate a quantifiable threshold of comprehension thereby serving as an objective indicator of the need for interventions to improve comprehension. | Our study demonstrates that cross-cultural adaptation and validation of an informed consent comprehension questionnaire is feasible. However, further research is needed to develop a tool which can estimate a quantifiable threshold of comprehension thereby serving as an objective indicator of the need for interventions to improve comprehension. | Afolabi, M. O., Rennie, S., Hallfors, D. D., Kline, T., Zeitz, S., Odongo, F. S., Amek, N.O. & Luseno, W. K. (2018). An adapted instrument to assess informed consent comprehension among youth and parents in rural western Kenya: a validation study. BMJ open, 8(7), e021613. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/7/e021613?int_source=trendmd&int_medium=trendmd&int_campaign=trendmd |

| The CDC Clear Communication Index is a new evidence-based tool to prepare and review health information | 2014 | This article presents the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clear Communication Index (the Index), a tool that emphasizes the primary audience's needs and provides a set of evidence-based criteria to develop and assess public communication products for diverse audiences. | The Index consists of four open-ended introductory questions and 20 scored items that affect information clarity and audience comprehension, according to the scientific literature. A research team fielded an online survey to test the Index's validity. Respondents answered 10 questions about either an original health material or one redesigned with the Index. For 9 out of 10 questions, the materials revised using the Index were rated higher than the original materials. | Regardless of education level, respondents rated the revised materials more favorably than the original ones. | The results indicate that the Index performed as intended and made it more likely that audiences could correctly identify the intended main message and understand the words and numbers in the materials. The results also support the widely held view that audiences are more positive about clearly designed materials. The Index shows that an evidence-based scoring rubric can assess and improve the clarity of health materials. | Baur C. & Prue C. The CDC Clear Communication Index Is a New Evidence-Based Tool to Prepare and Review Health Information. Health Promotion Practice. 2014;15(5):629–637. doi:10.1177/1524839914538969. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24951489/ |

| TEMPtED: development and psychometric properties of a tool to evaluation materials used in patient education | 2009 | Development and psychometric properties of a Tool to Evaluate Materials Used in Patient Education (TEMPtEd), which was designed to assist healthcare professionals to evaluate and select printed patient educational materials for their clients. | Previously developed instruments included attribute checklists, readability formulae and rating scales, but they have not been shown to be valid or reliable. The instrument was developed using Strickland's framework, with pilot testing conducted from 2004 to 2007. | The overall ratings of a heart failure educational brochure between the TEMPtEd and the Suitability Assessment of Materials, a previously developed instrument, were not significantly different. Significant correlations were noted in the overall scale and four of the five subscales. Internal consistency was 0·68, a reduction in rating scale options resulted in IC of 0·83–0·84. | As a result of psychometric testing, the TEMPtEd appears to be a promising instrument for the evaluation of patient educational material. | Clayton, L. H. (2009). TEMPtEd: development and psychometric properties of a tool to evaluate material used in patient education. Journal of advanced nursing, 65(10), 2229–2238. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05049.x |

| Health Literacy INDEX: Development, Reliability, and Validity of a New Tool for Evaluating the Health Literacy Demands of Health Information Materials | 2012 | There is no consensus on how best to assess the health literacy demands of health information materials. Comprehensive, reliable, and valid assessment tools are needed. | The authors report on the development, refinement, and testing of Health Literacy INDEX, a new tool reflecting empirical evidence and best practices. INDEX is comprised of 63 indicators organized into 10 criteria: plain language, clear purpose, supporting graphics, user involvement, skill-based learning, audience appropriateness, user instruction, development details, evaluation methods, and strength of evidence. | In a sample of 100 materials, intercoder agreement was high: 90% or better for 52% of indicators, and above 80% for nearly all others. Overall scores generated by INDEX were highly correlated with average ratings from 12 health literacy experts (r = 0.89, p < .0001) | Additional research is warranted to examine the association between evaluation ratings generated by INDEX and individual understanding, behaviors, and improved health. Health Literacy INDEX is a comprehensive tool with evidence for reliability and validity that can be used to evaluate the health literacy demands of health information materials. Although improvement in health information materials is just one aspect of mitigating the effects of limited health literacy on health outcomes, it is an essential step toward a more health literate public. | Kaphingst, K. A., Kreuter, M. W., Casey, C., Leme, L., Thompson, T., Cheng, M. R., Jacobsen H., Sterling R., Oguntimein, J., Filler, C., Culbert, A., Rooney, M. & Lapka C. (2012). Health Literacy INDEX: development, reliability, and validity of a new tool for evaluating the health literacy demands of health information materials. Journal of health communication, 17(sup3), 203–221. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10810730.2012.712612 |

| Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information | 2014 | To develop a reliable and valid instrument to assess the understandability and actionability of print and audiovisual materials. | We compiled items from existing instruments/guides that the expert panel assessed for face/content validity. We completed four rounds of reliability testing and produced evidence of construct validity with consumers and readability assessments. | The experts deemed the PEMAT items face/content valid. Four rounds of reliability testing and refinement were conducted using raters untrained on the PEMAT. Agreement improved across rounds. The final PEMAT showed moderate agreement per Kappa (Average K = 0.57) and strong agreement per Gwet's AC1 (Average = 0.74). Internal consistency was strong (a = 0.71; Average Item-Total Correlation = 0.62). For construct validation with consumers (n = 47), we found significant differences between actionable and poorly actionable materials in comprehension scores (76% vs. 63%, p < 0.05) and ratings (8.9 vs. 7.7, p < 0.05). For understandability, there was a significant difference for only one of two topics on consumer numeric scores. For actionability, there were significant positive correlations between PEMAT scores and consumer-testing results, but no relationship for understandability. There were, however, strong, negative correlations between grade-level and both consumer-testing results and PEMAT scores. | The PEMAT demonstrated strong internal consistency, reliability, and evidence of construct validity. | Shoemaker, S. J., Wolf, M. S., & Brach, C. (2014). Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient education and counseling, 96(3), 395–403. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S073839911400233X |

The study team reviewed and narrowed the selection to 23 independent items based on relevance to constructs of interest in previously validated tools. Six members of the expert advisory group reviewed and commented on the wording and relevance of each item. The initial version for testing included seven writing and seven design items representing readability, eight content items representing understandability, and one informed consent process item representing actionability (Table B).

Table B.

List of Items and Revisions. Initial version of the tool for testing and revisions made to each item for each round of testing.

| Item Code | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readability: Plain Language Writing Items | ||||

| Language9 | Active voice. Uses active voice (e.g. we will use) rather than passive voice (e.g. It will be used) all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. | Active voice. Uses active voice all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. | Active voice. Uses active verbs (e.g. will use) rather than passive verbs (e.g. will be used) all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. | Active voice. Uses active verbs (e.g. will use) rather than passive verbs (e.g. will be used) all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. |

| Language10 | Concise writing. Sentences are short. Avoids multi clause sentences. Information is to the point. Avoids unnecessary detail. | NA | NA | NA |

| Language11 | Word choice. Avoids jargon. Uses words readers are familiar with all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. | Lay language. Uses words readers will be familiar with all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. | Word choice. Avoids scientific jargon. Uses words readers are familiar with all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. | Word choice. Uses words readers are familiar with all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time. |

| Language12 | Conversational. Tone of voice is conversational, friendly, caring, inviting and supportive | NA | NA | NA |

| Language13 | Defines key terms. Defines medical, scientific, and technical terms. Provides a definition of the disease or topic about which the study is focused. | Defines technical terms. Medical, scientific, technical and other jargon and abbreviations are defined. | Defines key terms. Provides a definition of the disease or topic the study is about. | Defines key terms. Provides a definition of the disease or topic the study is about. |

| gradelevel14 | 8th grade or below. Reading grade level calculated in Microsoft Word is Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level 8.0 or below. | 8th grade or below. Use the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level as calculated in Microsoft Word (see below) to determine if the reading grade level is 8th grade or below. | 8th grade or below. Reading grade level calculated in Microsoft Word is Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level 8.0 or below. | 8th grade or below. Reading grade level calculated in Microsoft Word is Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level 8.9 or below. |

| Readability: Plain Language Design Items | ||||

| Org15 | “Chunk” of information. Paragraphs are short and address single topics. Information is organized by topic in section or chunks. | NA | NA | NA |

| Org16 | Headers. Sections or chunks of information are labeled with descriptive headers. Headers clearly describe what is in sections or chunks so readers can scan and find information. | Headers. Sections or chunks of information are labeled with clear and descriptive headers. Headers clearly describe what is in sections or chunks so readers can find key information. | Headers. Sections or chunks of information are labeled with headers. Headers clearly describe each section or chunks so readers can scan and find information. | Headers. Sections or chunks of information are labeled with headers. Headers clearly describe each section so readers can scan and find information. |

| design17 | Font type and size. Font type or style is easy to read. Font size is at least 11–12 point. | Font type and size. Written in a font type or style that is easy to read. Size of text is at least 11–12 point. | Font type and size. Font type or style is easy to read. Font size is at least 11–12 point. | Font type and size. Font type or style is easy to read. Font size is at least 11–12 point. |

| Design18 | Bulleted or numbered lists. Text is presented and organized using bullet point or numbered lists to increase white space on the page. | NA | NA | NA |

| design19 | Contrast. Print is visible on background color. Uses dark text on a light background, high contrast. Text is not placed on top of a graphic background. | Contrast. Print is visible on background color. Uses dark text on a light background, high contrast. Text is not placed on top of a graphic background. | Contrast. Uses dark text on a light background, high contrast. Text is not placed on top of a graphic background. | Contrast. Uses dark text on a light background, high contrast. Text is not placed on top of a graphic background. |

| design20 | White space. Page does not look dense with words. White space between paragraphs and in margins makes page look open and easy to read rather than dense and hard to read. | White space. Page layout allows for plenty of white space. Page should not look dense with words. Add space between paragraphs and in margins to make the page look open and | White space. White space between paragraphs and in margins makes page look open and inviting to read. | White space. Uses bulleted or numbered lists to increase white space on the page. |

| easy to read, rather than dense and hard to read. | ||||

| Image21 | Image. Contains at least one image that is related to or reflective of the topic or content of the study. | Image. Contains at least one image that is related to or reflective of the topic or content of the study. | Image. Contains at least one image that is related to the topic of the study. | Image. Contains at least one image that is related to the topic of the study. |

| Numbers 22 | Numeric risk probability. If numerical probability is used to describe risk, the probability is also explained with words. If no numeric probability is described, answer not present. | Numeric risk probability. If numerical probability is used to describe risk, the probability is also explained with words. If no numeric probability is described, answer not applicable (NA). | Numeric risk probability. If numbers are used to describe risk, says “1 or 4” rather than 25% risk. If no numeric probability is described, answer not present. | Numeric risk probability. If numbers are used to describe risk, says “1 or 4” rather than 25%. If no numeric probability is described, answer not present. |

| Understandability: Key Information Content Items | ||||

| Keyinfo1 | Purpose of the study. The purpose of the study is stated, rather than implied. Includes a statement that says, “The purpose of the study is…” | Purpose of the study. Purpose is clearly stated rather than implied. Includes a statement that says, The purpose of the study is..” | Purpose of the study. Includes a statement that says, “The purpose of the study is…” The purpose of the study is stated, rather than implied. | Purpose of the study. Includes a statement that says, “the purpose of the study is …” purpose of the study is stated, rather than implied. |

| Keyinfo2 | Main reason to join the study – benefits. Describes reason(s) to join the study. Includes description or list of benefits to participants or others. | Main reason to join the study - benefits. Reason(s) to join the study including a description or list of benefits to participants or others are clearly included. | Main reason to join the study - benefits. Includes description of benefits to participants or others. | Main reason to join the study - benefits. Includes description of benefits to participants or others. |

| Keninfo3 | Main reasons not to join the study – risks. Describes reason(s) not to join the study. Includes description or list of risks. | Main reasons not to join the study - risks. Reason(s) not to join the study including a description or list of risks are clearly included. | Main reasons not to join the study - risks. Includes description or list of potential risks to participants. | Main reasons not to join the study - risks. Includes description or list of potential risks to participants. |

| Keyinfo4 | Information being collected. Describes the information and data that will be | Information being collected. Clearly describes the information that will | Information being collected. Describes the information that will be collected | Information being collected. Describes the information that will be collected from |

| collected from and about participants. | be collected from participants. | from participants and about participants. | participants and about participants. | |

| Keyinfo5 | Study procedures. Describes what will happen during the study. Includes what participants will do and how much time it will take. | Study procedures. Clearly describes what will happen during the study, what participants will have to do, and how much time it will take. | Study Procedures. Describe what participants will need to do, must include estimate of how much time it will take. | Study Procedures. Describe what participants will need to do, and how much time it will take. |

| Keyinfo6 | How treatment is different from standard care. Includes a statement that says participation is not the same as treatment from their doctor. | How treatment is different from standard care. Includes a statement that describes how participation is not the same as treatment from their doctor. | Study is research. Includes a statement that says, “study is research” and not just consenting to treatment. | Study is research. Includes a statement that says, “study is research” or “research study”, not just consenting to treatment. |

| Keyinfo7 | Participation is voluntary. States that participation is voluntary, that participants have a choice to join the study or not. | Participation is voluntary. Explains that participation is voluntary, that participants join of their own free will, that they have a choice to join the study or not. | Participation is voluntary. States that participation is voluntary, meaning participants have a choice to be in the study or withdraw at any time. | Participation is voluntary. States that participation is voluntary, participants have a choice to be in the study or not. |

| Keyinfo8 | Costs and compensation. Describes any financial cost of participation or payments to study participants. | Costs and compensation. Describes any financial cost of participation or payments to study participants. | Costs and compensation. Describes any financial payments (or costs) to study participants. | Costs and compensation. Describes any financial payments (or costs) to study participants. |

| Actionability: Action Items - Giving Informed Consent | ||||

| Action23 | Consent process. Describes the process by which the reader gives their consent, either by signing a document, verbal agreement, via computer, or other. | Consent process. Explains consent process. Describes the process by which the reader gives their consent, either by signing a document, verbal agreement, via computer, or other. | Consent process. Describes the process by which the reader gives their consent, either by signing a document, verbal agreement, via computer, or other. | Consent process. Describes the process by which the reader gives their consent, either by signing a document, verbal agreement, via computer, or other. |

Reliability

We conducted four sequential rounds of inter-rater reliability and one round of intra-rater reliability testing with a total of 24 raters applying the criteria for assessment items to key information sections from a total of 10 informed consent forms (Table 2). Prior to Rounds 1–3, raters were instructed to apply the tool but were not provided any guidance on interpreting the individual items. After each test we calculated percent agreement and Kappa for each item and compiled qualitative feedback from raters. Kappa scores were low for most items and negative for some in early testing rounds; low Kappa scores indicated poor inter-rater agreement, while negative Kappa scores indicated insufficient response variability. In the first round, rating three key information samples, agreement among raters was ≥80% on only eight out of 23 items.

Table 2.

Test Round Details

| Test | Tool Version (A, B, C, or D) and Number of Itemsa | Number of Raters | Number of Key Information Documents | Inter-Rater | Intra-Rater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | A: 23 items | 5 raters | 3 documents | X | - |

| Round 2 | B: 19 items | 5 new raters | 3 documents (same as in test round 1) | X | - |

| Round 3 | C: 19 items | 10 new raters | 4 documents (same 3 as in test rounds 1 and 2, plus 1 new document) | X | - |

| Round 4 | D: 19 items | 4 new raters | 10 documents (same 4 documents as in test round 3, plus 6 new documents) | X | - |

| Repeat test for Round 4 one month later | D: 19 items | 4 same raters as in test round 4 | 4 documents (same documents as in test round 3, a subset of test round 4) | - | X |

See Table B for evolution of the RUAKI (Readability, Understandability and Actionability of Key Information) tool over four rounds of iteration informed by inter-rater reliability testing and content expert reviews.

We edited 19 items and removed four items prior to Round 2. In the second test, inter-rater agreement was ≥80% on 11 out of 19 items. To increase response variability, we adjusted our strategy in test 3 by adding a fourth key information sample and in test 4 we added 6 more to further balance high and low scoring forms and items. We also added the Gwet's AC1 statistic. In Round 3 inter-rater agreement was ≥80% on 15 of 19 items. In Round 3 of testing, 9 items demonstrated moderate inter-rater agreement per Fleiss' Kappa (average = .48) and 15 items demonstrated substantial agreement per Gwet's AC1 (average = .81). Four items received negative Kappa scores.

We conducted a process of rater calibration prior to Round 4 to provide explicit instruction on interpreting each item. The process involved having raters read and score one sample key information section and discuss findings for each item collectively. In Round 4 raters again achieved ≥80% agreement on 15 of 19 items. In this final round of testing, 18 of 19 items demonstrated substantial inter-rater agreement per Fleiss' Kappa (average = .73) and Gwet's AC1 (average = .77) (Table 3). The tool demonstrated substantial intra-rater agreement in Round 4 per Cohen's Kappa (average = .74) and almost perfect agreement per Gwet's AC1 (average = 0.84).

Table 3.

Final Agreement Scores

| Construct Items | Percent Agreement | Fleiss' Kappa | Gwet's AC1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readability | |||

| Active voice. Uses active verbs (e.g. will use) rather than passive verbs (e.g. will be used) all or most of the time, more than 80% of the time | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.92 |

| Word choice. Uses words readers are familiar with all or most of the time, more than 80% of the timea | 0.50 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Defines key terms. Provides a definition of the disease or topic the study is about | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.47 |

| 8th grade or below. Reading grade level calculated in Microsoft Word is Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level 8.9 or below | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.92 |

| Headers. Sections or chunks of information are labeled with headers. Headers clearly describe each section so readers can scan and find information | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Font type and size. Font type or style is easy to read. Font size is at least 11–12 point | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Contrast. Uses dark text on a light background, high contrast. Text is not placed on top of a graphic background | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| White space. Uses bulleted or numbered lists to increase white space on the page | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Image. Contains at least one image that is related to the topic of the study | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Numeric risk probability. If numbers are used to describe risk, says “1 or 4” rather than 25%. If no numeric probability is described answer not presentb | 1.00 | - | - |

| Understandability | |||

| Purpose of the study. Includes a statement that says, “the purpose of the study is …” purpose of the study is stated, rather than implied | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.78 |

| Main reason to join the study - benefits. Includes description of benefits to participants or others | 0.77 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| Main reasons not to join the study - risks. Includes description or list of potential risks to participants | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.71 |

| Information being collected. Describes the information that will be collected from participants and about participants | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.47 |

| Study Procedures. Describe what participants will need to do, and how much time it will take | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| Study is research. Includes a statement that says, “study is research” or “research study,” not just consenting to treatment | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Participation is voluntary. States that participation is voluntary, participants have a choice to be in the study or not | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.77 |

| Costs and compensation. Describes any financial payments (or costs) to study participants | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.83 |

| Actionability | |||

| Consent process. Describes the process by which the reader gives their consent, either by signing a document, verbal agreement, via computer, or other | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| Tool Average | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.77 |

Items had higher than expected agreement compared to observed agreement causing negative Kappa.

Item had perfect agreement. Kappa and Gwet's AC1 undefined. In round 3 this item achieved .90 percent agreement, −0.05 Fleiss's Kappa, and .89 Gwet's AC1.

In a final assessment of functionality of the tool, a member of the study team (S.K.R.) interviewed members of the final rater cohort. Raters discussed all the items with <80% agreements in Rounds 3 and 4 and based on their feedback additional changes were made.

The order of items on the final tool was also discussed. The final 18-item RUAKI Indicator is presented in Figure A.

Figure A.

18-item tool designed to assess the readability, understandability, and actionability of key information on research informed consent forms.

1 Office for Human Research Protection (OHRP). (2021, March 10). 2018 Requirements (2018 Common Rule). 46.116 General Requirements for Informed Consent. HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/revised-common-rule-regulatory-text/index.html#46.116

Construct Validity

We collected evidence of construct validity from 16 potential research study participants via survey and focus groups. The majority (n = 12) of participants were women. One-half (n = 8) identified as Black/African American, Asian, or Hispanic. One-quarter of participants (n = 4) had only a high school education. One-half (n = 8) indicated that they sometimes needed help reading health information received from their doctor or pharmacy, an indication of low health literacy (Chew et al., 2008). Level of income was variable (Table 4). A majority (n = 14) said they or a family member had experienced a serious illness and one-half (n = 8) said they had experience participating in a clinical research study.

Table 4.

Demographics: Focus Group Participant (N = 16)

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Women | 12 (75) |

| Men | 4 (25) |

|

| |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–44 | 4 (25) |

| 45–64 | 8 (50) |

| 65 and older | 4 (25) |

|

| |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 3 (18) |

| Asian | 4 (25) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.3) |

| White | 8 (50) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| High school diploma | 4 (25) |

| Bachelor's degree | 3 (18.8) |

| Master's degree | 9 (56.3) |

|

| |

| Health literacy (single question screen) | |

| Inadequate | 6 (36.5) |

| Adequate | 10 (62.5) |

The RUAKI Indicator score for the original, IRB-approved ICF key information sample was 68%. The RUAKI Indicator score for the developed revised version was 90%. In focus group feedback, of the two key information samples, end-users indicated the RUAKI Indicator-developed version was easier to read. Common themes and supporting comments confirmed that the plain language writing and design principles were relevant to reading ease and comprehension (Table C).

Table C.

Themes and Supporting Comments. Three researchers reviewed the two focus group transcripts, coded participant comments, and compared notes to agree upon common themes.

| Focus Group Themes | Participant Comments |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Theme: Bullet points and white space |

|

| Rationale: According to end users, using bullet points and creating more white space on the page makes key information easier to read | |

|

| |

| Theme: Big, long blocks of text |

|

| Rationale: According to end users, big blocks of text make informed consent information hard to read | |

|

| |

| Theme: Meaningful pictures |

|

| Rationale: A number of end users said they liked the picture, but that it needs to convey meaning to be most useful. | |

|

| |

| Theme: Short, concise information |

|

| Rationale: End users said, what made key information on informed consent forms hard to read was jargon, block of text, and length (too long). There was lots of support for concise key information. | |

|

| |

| Theme: Informed consent and participation in research |

|

| Rationale: End users noted barriers to participating in research especially for underrepresented groups included hard to read informed consent information, lack of compensation, and issues of risks | |

| and side effects not clearly explained. | minimize the barrier a lot. Especially if there is not compensation at all.”

|

|

| |

| Good: Theme: Informed consent process |

|

| Rationale: The informed consent process matters. Having someone explain the study risks and side effects makes a difference and builds trust | |

|

| |

| Theme: Language and translation |

|

| Rationale: End users who speak a language other than English noted that jargon, synonyms, and passive voice made it very difficult to understand and translate content and concepts | |

|

| |

| Theme: Plain language, understanding and decisional capacity |

|

| Rationale: End users indicated that easier to read informed consent forms helped them understand the research process and thus aided them in their decisional capacity | |

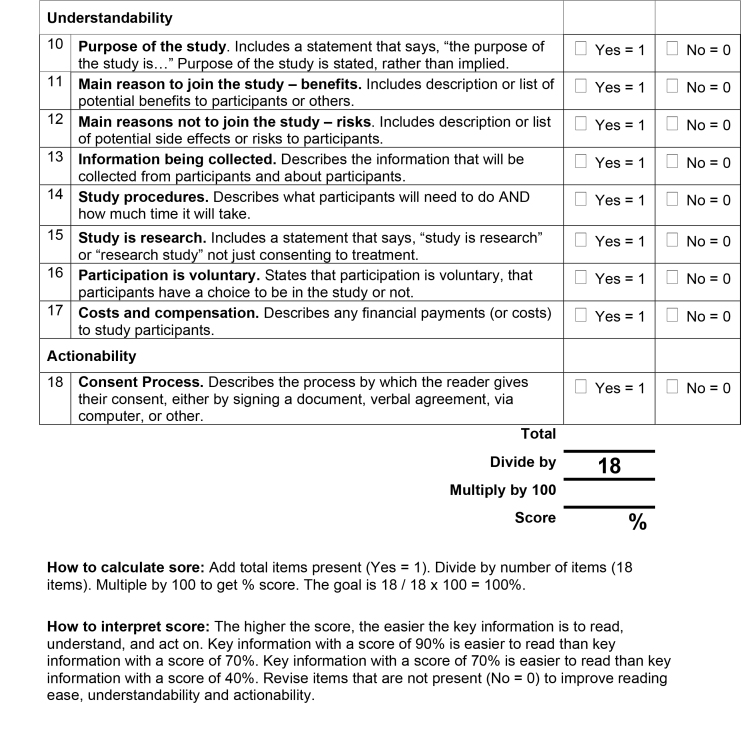

Fourteen of 16 focus group participants completed the study survey (Figure B). Eighty-six percent of participants identified the presence of plain language design elements and agreed or strongly agreed the developed key information sample was easy to read. Only 64% agreed all the words were familiar to them. Scores on the five true/false questions test-ing comprehension ranged from 60% correct to 87% correct (average 76% correct).

Figure B.

Participant Survey. Includes 5-point Decisional Conflict Scale, and questions to assess reading ease or difficulty, understanding, and demographics.

Imagining their own potential participation in the study presented, focus group participants scored from 0 to 42.2 on the five-part decisional conflict scale with a median score of 27.3 (first quartile [Q1]-third quartile [Q3]: 14.1–37.5). Participants rated conflict on the informed subscore, median 16.7 (Q1–Q3: 8.3–25.0), support subscore, median 25.0 (Q1–Q3: 0.0–33.3), effective decision subscore, median 25.0 (Q1–Q3: 6.3–37.5), values Clarity subscore (concerned with balancing risks and benefits) median 37.5 (Q1–Q3: 0.0–50.0) and uncertainty subscore, median 37.5 (Q1–Q3: 25.0–50.0).

Discussion

The RUAKI Indicator demonstrated strong face and content validity as assessed by an expert panel review. The indicator assesses readability, understandability, and actionability of key information on informed consent forms and comprises 18 items that demonstrated a high degree of inter-and intra-rater agreement. A key information sample developed with the RUAKI Indicator was presented to a group of potential patients. The group as a whole expressed that the sample was more accessible and comprehensible as compared to the IRB-approved original. Further, the informed domain of the DCS demonstrated the lowest score among all domains, reflecting the contribution of improved understanding to confidence in deciding to take part in the proposed research.

Consent forms that are hard to read deny equitable access to the information and the opportunity to participate in clinical research. It also increases the risk of uninformed consent. As part of a person-centered informed consent process, the RUAKI Indicator has the potential to support communication and understanding minority and underserved populations who are underrepresented in clinical research. The use of easier to read key information in the informed consent process is a step toward greater transparency and community trust.

The entirety of the research consent document serves as a resource to potential research participants, providing information about the clinical research both for their own reference and anyone with whom they share decision making. However, the consent document, let alone the key information section, cannot be presented as a substitute for an informed discussion with a knowledgeable representative of the research team. Using the RUAKI Indicator, research teams will be able to write easier to read key information and identify shortcomings of the written document they can then follow up on in informed consent conversations.

Facilitating the informed consent process and ensuring that all potential barriers to research participation are addressed is ultimately the responsibility of the investigator. In this study the RUAKI Indicator demonstrated validity and reliability to help guide investigators to create more accessible information about their research.

Limitations

We focused only on the summary key information section of the informed consent document, which was recently added as a requirement under the final common rule. This was a deliberate limitation in scope intended to focus attention on the potential impact and optimal construction of this new requirement.

Limitations related to the study design include issues associated with Kappa scoring. Despite good percent agreement on individual items within the RUAKI tool, inter-rater reliability (external consistency) as measured by Kappa was negative for some items in early rounds of testing. This is a known problem of the Kappa statistic (Feinstein & Cicchetti, 1990), which arises when responses fall into two diametrically opposed categories (some say strongly no others strongly yes). We addressed this by adding more summary samples to prompt a wider variability in responses and modifying our statistical plan to include Gwet's AC1 agreement coefficient.

The study only tested a small sample of informed consent key information sections. It is possible the reliability of the tool could vary for key information describing different types of study designs, topics, locations, and settings. Our experience in Round 4 of testing demonstrated that some level of instruction and practice on how to interpret the individual items is helpful for consistent application of the tool, without there may be risk of inconsistent results. The small number of potential research participants (n = 16) who attended the focus groups self-identified as interested in clinical research participation which may have introduced bias through a greater familiarity with informed consent. Administration of the survey after receiving the original and revised key information sections may also have introduced bias.

Ultimately, the stakes involved in decision making when the risks and benefits are real, are strikingly different in actual practice. A prospective evaluation of the impact of the RUAKI Indicator on informing research participation in the context of an actual clinical research trial will be required to demonstrate real world impact of plain language writing on informed decision making.

Implications

The RUAKI Indicator is designed to help investigators and research teams develop easy-to-read key information sections for informed consent forms. Potential study participants may better assimilate this key information when presented in plain, everyday language to make informed decisions about their participation in clinical research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants who rated the reading ease of key information on informed consent forms using the Readability, Understandability and Actionability of Key Information (RUAKI) Indicator; members of the Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) Stakeholder Expert Panel of community members for providing qualitative feedback that helped improve the RUAKI Indicator as an applied tool; the study team members including Christopher Oettgen and Noe Dueñas for study coordination; Stasia Swiadas for literature review and scheduling; Noelle Pinkerd and Robert Sege for participant recruitment and support; Ye Chen, Lori Lyn Price, Svetlana Rojevsky, and Benjamin Sweigart for data collection, management, and analysis; Timothy Bilodeau, Alice Rushforth, and the Tufts CTSI for their support and leadership; and our research advisory group including: Sylvia Baedorf-Kassis, Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard; Behtash Bahador, Center for Information & Study on Clinical Research Participation; Apollo Cátala, Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation, Tufts CTSI Stakeholder Expert Panel; Sara Couture, Division of Nephrology, Tufts Medical Center; Caitlin Farley, Tufts Institutional Review Board, Tufts Medical Center; Linda Hudson, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Tufts CTSI; Christopher Trudeau, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and UA Little Rock Bowen School of Law.

Funding Statement

Grant: This research was supported by grant UL1TR002544 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- Afolabi , M. O. , Rennie , S. , Hallfors , D. D. , Kline , T. , Zeitz , S. , Odongo , F. S. , Amek , N. O. , & Luseno , W. K. ( 2018. ). An adapted instrument to assess informed consent comprehension among youth and parents in rural western Kenya: A validation study . BMJ Open , 8 ( 7 ), e021613 . 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021613 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur , C. , & Prue , C. ( 2014. ). The CDC Clear Communication Index is a new evidence-based tool to prepare and review health information . Health Promotion Practice , 15 ( 5 ), 629 – 637 . 10.1177/1524839914538969 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begeny , J. C. , & Greene , D. J. ( 2014. ). Can readability formulas be used to successfully gauge difficulty of reading materials? Psychology in the Schools , 51 ( 2 ), 198 – 215 . 10.1002/pits.21740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . ( n.d.. ). Guidelines for effective writing . https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/WrittenMaterialsToolkit/ToolkitPart07 [Google Scholar]

- Chew , L. D. , Griffin , J. M. , Partin , M. R. , Noorbaloochi , S. , Grill , J. P. , Snyder , A. , Bradley , K. A. , Nugent , S. M. , Baines , A. D. , & Vanryn , M. ( 2008. ). Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 23 ( 5 ), 561 – 566 . 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton , L. H. ( 2009. ). TEMPtEd: Development and psychometric properties of a tool to evaluate material used in patient education . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 65 ( 10 ), 2229 – 2238 . 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05049.x PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen , J. ( 1960. ). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales . Educational and Psychological Measurement , 20 ( 1 ), 37 – 46 . 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel , E. J. , & Boyle , C. W. ( 2021. ). Assessment of length and readability of informed consent documents for COVID-19 Vaccine Trials . JAMA Network Open , 4 ( 4 ), e2110843 . 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10843 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein , A. R. , & Cicchetti , D. V. ( 1990. ). High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 43 ( 6 ), 543 – 549 . 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90158-L PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss , J. L. ( 1971. ). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters . Psychological Bulletin , 76 , 378 – 382 . 10.1037/h0031619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser , B. , & Strauss , A . ( 1967. ). The Discovery Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Inquiry . Aldin . [Google Scholar]

- Grant , S. C. ( 2021. ). Informed consent-we can and should do better . JAMA Network Open , 4 ( 4 ), e2110848 . 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10848 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwet , K. L. ( 2008. , May ). Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement . British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology , 61 ( Pt 1 ), 29 – 48 . 10.1348/000711006X126600 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadden , K. B. , Prince , L. Y. , Moore , T. D. , James , L. P. , Holland , J. R. , & Trudeau , C. R. ( 2017. ). Improving readability of informed consents for research at an academic medical institution . Journal of Clinical and Translational Science , 1 ( 6 ), 361 – 365 . 10.1017/cts.2017.312 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal , P. , & MacDermid , J. C. ( 2017. ). Assessing reading levels of health information: Uses and limitations of Flesch formula . Education for Health (Abingdon) , 30 ( 1 ), 84 – 88 . 10.4103/1357-6283.210517 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphingst , K. A. , Kreuter , M. W. , Casey , C. , Leme , L. , Thompson , T. , Cheng , M. R. , Jacobsen , H. , Sterling , R. , Oguntimein , J. , Filler , C. , Culbert , A. , Rooney , M. , & Lapka , C. ( 2012. ). Health Literacy INDEX: Development, reliability, and validity of a new tool for evaluating the health literacy demands of health information materials . Journal of Health Communication , 17 ( Suppl. 3 ), 203 – 221 . 10.1080/10810730.2012.712612 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid , J. P. , Fishburne , R. P. , Rogers , R. L. , & Chissom , B. S. ( 1975. ). Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count, and flesch reading ease formula) for Navy enlisted personnel . Research Branch Report 8 – 75 . Chief of Naval Technical Training: Naval Air Station Memphis. [Google Scholar]

- Landis , J. R. , & Koch , G. G. ( 1977. , March ). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data . Biometrics , 33 ( 1 ), 159 – 174 . 10.2307/2529310 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson , E. , Foe , G. , & Lally , R. ( 2015. ). Reading level and length of written research consent forms . Clinical and Translational Science , 8 ( 4 ), 355 – 356 . 10.1111/cts.12253 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley , P. , & Florio , T. ( 1996. ). The use of readability formulas in health care . Psychology Health and Medicine , 1 ( 1 ), 7 – 28 . 10.1080/13548509608400003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor , A. M. ( 1995. ). Validation of a decisional conflict scale . Medical Decision Making , 15 ( 1 ), 25 – 30 . 10.1177/0272989X9501500105 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . ( n.d.. ). Health literacy in Healthy People 2030 . https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 [Google Scholar]

- Office for Human Research Protections . ( 2018. ). Attachment C -new “Key information” informed consent requirements. SACHRP commentary on the new key information informed consent requirements . https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/attachment-c-november-13-2018/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Office for Human Research Protections . ( 2021. ). 2018 requirements (2018 Common Rule) . https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/revised-common-rule-regulatory-text/index.html#46.116

- Paasche-Orlow , M. K. , Taylor , H. A. , & Brancati , F. L. ( 2003. ). Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability . The New England Journal of Medicine , 348 ( 8 ), 721 – 726 . 10.1056/NEJMsa021212 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plain Language Action and Information Network . ( n.d.. ). Federal plain language guidelines . https://www.plainlanguage.gov/guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- Perrenoud , B. , Velonaki , V. S. , Bodenmann , P. , & Ramelet , A. S. ( 2015. ). The effectiveness of health literacy interventions on the informed consent process of health care users: A systematic review protocol . JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports , 13 ( 10 ), 82 – 94 . 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2304 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter , K. M. , Weiss , E. M. , & Kraft , S. A. ( 2021. ). Promoting disclosure and understanding in informed consent optimizing the impact of the Common Rule “Key Information” Requirement . The American Journal of Bioethics , 21 ( 5 ), 70 – 72 . 10.1080/15265161.2021.1906996 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish , J. ( 2000. ). Readability formulas have even more limitations than Klare discusses . ACM Journal of Computer Documentation , 24 ( 3 ), 132 – 137 . 10.1145/344599.344637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock , A. , & Brownie , S. ( 2014. ). Patients' recollection and understanding of informed consent: A literature review . ANZ Journal of Surgery , 84 ( 4 ), 207 – 210 . 10.1111/ans.12555 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker , S. J. , Wolf , M. S. , & Brach , C. ( 2014. ). Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audio-visual patient information . Patient Education and Counseling , 96 ( 3 ), 395 – 403 . 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.027 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamariz , L. , Palacio , A. , Robert , M. , & Marcus , E. N. ( 2013. ). Improving the informed consent process for research subjects with low literacy: A systematic review . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 28 ( 1 ), 121 – 126 . 10.1007/s11606-012-2133-2 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekfi , C. ( 1987. ). Readability formulas: An overview . The Journal of Documentation , 43 ( 3 ), 261 – 273 . 10.1108/eb026811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]