Abstract

DTNA encodes α-dystrobrevin, a component of the macromolecular dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC) that binds to dystrophin/utrophin and α-syntrophin. Mice lacking α-dystrobrevin have a muscular dystrophy phenotype, but variants in DTNA have not previously been associated with human skeletal muscle disease.

We present 12 individuals from four unrelated families with two different monoallelic DTNA variants affecting the coiled-coil domain of α-dystrobrevin. The five affected individuals from family A harbor a c.1585G>A; p.Glu529Lys variant, while the recurrent c.1567_1587del; p.Gln523_Glu529del DTNA variant was identified in the other three families (family B: four affected individuals, family C: one affected individual, and family D: two affected individuals).

Myalgia and exercise intolerance, with variable ages of onset, were reported in 10 of 12 affected individuals. Proximal lower limb weakness with onset in the first decade of life was noted in three individuals. Persistent elevations of serum creatine kinase (CK) levels were detected in 11 of 12 affected individuals, one of whom had an episode of rhabdomyolysis at 20 years of age. Autism spectrum disorder or learning disabilities were reported in four individuals with the c.1567_1587 deletion.

Muscle biopsies in eight affected individuals showed mixed myopathic and dystrophic findings, characterized by fiber size variability, internalized nuclei, and slightly increased extracellular connective tissue and inflammation. Immunofluorescence analysis of biopsies from five affected individuals showed reduced α-dystrobrevin immunoreactivity and variably reduced immunoreactivity of other DGC proteins: dystrophin, α, β, δ and γ-sarcoglycans, and α and β-dystroglycans. The DTNA deletion disrupted an interaction between α-dystrobrevin and syntrophin.

Specific variants in the coiled-coil domain of DTNA cause skeletal muscle disease with variable penetrance. Affected individuals show a spectrum of clinical manifestations, with severity ranging from hyperCKemia, myalgias, and exercise intolerance to childhood-onset proximal muscle weakness. Our findings expand the molecular etiologies of both muscular dystrophy and paucisymptomatic hyperCKemia, to now include monoallelic DTNA variants as a novel cause of skeletal muscle disease in humans.

Keywords: α-dystrobrevin, dystrophin, hyperCKemia, muscle sarcolemmal proteins, myalgia, rhabdomyolysis

1. Introduction

Muscular dystrophies are associated with defects of muscle membrane stability and repair that lead to dystrophic changes in skeletal muscle and a combination of clinical symptoms including muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis, elevations of serum creatine kinase (CK) levels, exercise intolerance, and/or myalgias. Some affected individuals do not have prominent weakness, instead presenting with more subtle constellations of symptoms [28, 40]. In settings where genetic testing, and in particular next generation sequencing, is readily available, this diagnostic modality often yields a definitive, molecular diagnosis [31]. When genetic testing does not indicate a genetic/molecular etiology, muscle biopsy continues to be a useful diagnostic tool for confirming dystrophic histopathology and immunohistochemical findings which sometimes demonstrate a specific sarcolemmal protein defect.

Several genes linked to muscular dystrophy, including DMD, FKRP, DYSF, CAV3, SGCG, SGCB, and ANO5, have been associated with variable phenotypes including hyperCKemia/rhabdomyolysis, myalgia, and exercise intolerance, which have sometimes been referred to as ‘pseudometabolic phenotype’s [5, 11, 27, 32-34, 40, 44]. Despite this, in many individuals with paucisymptomatic hyperCKemia the genetic etiology remains elusive [43]. It is therefore likely that new muscular dystrophy genes remain to be identified in families with more subtle manifestations of this disease category.

DTNA encodes α-dystrobrevin, a component of the macromolecular dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC) that binds to dystrophin/utrophin and α-syntrophin [2, 30]. α-dystrobrevin plays a major role in stabilization of the DGC but also in mobility and turnover of acetylcholine receptors [2, 14]. A secondary deficiency of α-dystrobrevin has been described in individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and other muscular dystrophies [20, 29]. Absence of α-dystrobrevin is associated with muscular dystrophy in mice [16] and a single case report associated variants in DTNA with a dominantly inherited left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy without skeletal muscle involvement [17].

Here we present 12 individuals from four unrelated families with dominantly inherited missense variants in DTNA, presenting with phenotypes ranging from hyperCKemia to a mild form of muscular dystrophy (Figure 1). Our findings broaden the molecular etiologies of both muscular dystrophy and paucisymptomatic hyperCKemia.

Figure 1. Pedigrees of the four families with DTNA variants included in this study.

Arrows indicate probands, circles indicate females, squares indicate males, filled in symbols denote affected individuals (the gray colour indicates a milder phenotype), and a question mark in the box indicates that the phenotype is not known. Asterisks mark individuals from whom DNA samples were obtained.

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment of individuals, clinical examinations and sample collection

Individuals with muscular dystrophy and/or paucisymptomatic hyperCKemia were ascertained and enrolled from neuromuscular units in Spain and the United States. Data were collected and analyzed in accordance with ethics guidelines of Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Boston Children’s Hospital, the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Minnesota. Written informed consent for study participation was obtained. All individuals in this cohort underwent clinical examination. Blood and/or saliva samples for DNA analyses were collected from the 12 affected individuals, nine asymptomatic informative family members, and one family member with an undetermined phenotype (Figure 1). Symptomatic individuals were considered to be those with myalgias, exercise intolerance, muscle weakness, and/or hyperCKemia. Data on clinical electromyography studies, muscle MRIs, and muscle biopsies were collected for individuals who underwent one or more of these tests.

2.2. Molecular genetic analyses

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples of 12 affected individuals (A.II.2, A.II.4, A.II.7, A.III.1, A.III.2, B.I.1, B.II.4, B.III.1, B.III.3, C.II.1, D.II.3, and D.III.2), 9 of their unaffected relatives (A.II.1, A.II.3, A.II.5, AII.6, B.I.2, B.II.1, B.II.3, C.I.2, and D.II.4) and 1 relative with an undetermined phenotype (C.I.1) using standard techniques (Figure 1). Targeted exome sequencing was performed in individual A.III.2 using the TruSight One Sequencing Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) that provides coverage of 6710 genes associated with known human diseases based on the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (OMIM; http://www.omim.org). The protocol consisted of genomic DNA tagmentation with transposomes, PCR amplification, purification of libraries, hybridization and capture of target regions (the exons along with flanking intronic regions), followed by additional purification and amplification steps. Paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 System (Illumina). Targeted exome sequencing data was processed through an in-house pipeline. Alignment was performed using the BWA Aligner (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK) (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml) [25] to human genome build 37 (hg37). Variant calling was applied using the following four software tools: SAMtools v.1.5 (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute), GATK Haplotype Caller package v.3.7 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA), FreeBayes v.1.1.0 (Boston College, Boston, MA, USA), and VarScan v.2.4.0 (Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA). Finally, annotation was performed with SnpEff v.4.3 (Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA). Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed on genomic DNA samples from individuals B.I.1, B.I.2, B.II.1, B.II.3, B.II.4, B.III.1, and B.III.3 at Claritas Genomics (Cambridge, MA, USA) using Ampliseq Exome methodology on an Ion Proton sequencer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Variants were called by the Torrent Suite Variant Caller (https://github.com/iontorrent/TS/tree/master/plugin/variantCaller) and annotated using ANNOVAR (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA) [47]. Trio WES was performed on families C (C.I.1, C.I.2, C.II.1) and D (D.II.3. D.II.4, D.III.2) at the Broad Institute using previously described methods [41].

Variants were annotated using the reference sequences: NM_001390.5 (transcript) and Q9Y4J8 (protein). DTNA variant validation and segregation studies were completed using standard Sanger sequencing techniques.

2.3. In silico analyses of novel DTNA variants

In silico analyses of the genetic variants were performed using FATHMM-MKL (https://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/fathmmMKL.htm); Mutation taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org); DANN (https://cbcl.ics.uci.edu/public_data/DANN); PROVEAN (provean.jcvi.org/seq_submit.php); and CADD (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu) [8, 23]. Variant classification was assigned using Varsome following ACMG-AMP guidelines [42]. The mutational mapper plot was based on data available from the Human Gene Mutation Database. α-dystrobrevin tolerance lansdscape was analysed acoording to MetaDome software v.1.0.1 (https://stuart.radboudumc.nl/metadome). Structural models of α-dystrobrevin were built via homology modeling using Protein Homology/analogY Recognition Engine v2.0 (Phyre2) [22] and visualized using Chimera.

2.4. Muscle biopsy, histological, immunohistochemical, immunofluorescence, and ultrastructural studies

Clinical muscle biopsy specimens were obtained from biceps (A.II.2, A.II.7), deltoids (A.III.1, A.III.2), gastrocnemius (B.II.4), or quadriceps (B.III.3, C.II.1, D.III.2) in eight affected individuals. Sections of snap-frozen tissue were processed using routine histochemical stains, including hematoxylin & eosin (H&E), modified Gomori trichrome, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), cytochrome c oxidase (COX), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), and Oil Red O [10].

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on sections of the snap-frozen muscle biopsies of individuals A.II.2, A.II.7, A.III.1, A.III.2 and C.II.1 using the antibodies listed in Supplementary Table S1 (online resource), as well as monoclonal mouse anti-α-dystrobrevin (D-9) (1:100; sc271630; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), targeting amino acids 301-600 that map to an internal region of α-dystrobrevin. Goat anti-mouse Alexa fluor-594 (1:500; A21207; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was the secondary antibody. Samples from individual A.III.1 and a control were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (1 μg/mL; B13422; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) to label acetylcholine receptors in order to observe the structure of the neuromuscular junctions. Superresolution imaging was performed on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope using a 63× NA 1.12 objective (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ v.1.46 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Ultrathin sections were prepared for electron microscopy and examined with transmission electron microscopy (JEOL model 1100). Electron micrographs were obtained using the Gatan Orius CCD camera (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Münster, Germany).

2.5. Western Blot analysis

For total protein extraction from skeletal muscle specimens in family A, we used RIPA lysis buffer (Bio Basic, ON, Canada) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Bio Basic). The sample lysates were homogenized using pellet pestles (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The protein solutions were diluted in 2x Laemmli buffer prior to loading on gels. Western blots were performed following standard protocols. Precast gels TGX 4-15% gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) were used, with proteins transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membrane blocking was performed with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The membranes were subsequently incubated with the primary antibody monoclonal rabbit anti-DTNA (1:1000; ab191395; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) that targets amino acids 600-743, mapping to the C-terminal protein domain, at 4°C overnight with gentle agitation. Anti-α-tubulin (1:1000; T6199; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as a housekeeping protein loading control. IRDye 680CW goat-anti-rabbit IgG and IRDye 800CW goat-anti-mouse IgG (1:10000; LI-COR Biosciences) were used as secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized on the Odyssey LICOR fluorescent system (LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified using ImageJ v.1.46 (National Institutes of Health).

2.6. Vector construction, GST pulldown and immunoblotting assays

We generated constructs containing human control and mutant DTNA by cloning the cDNA of human WT DTNA into pEBG containing an N-terminal GST tag. The mutant containing the 21bp c.1567_1587 deletion was generated using the Quick Change Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with the primers designed using Agilent’s online primer design program. For transfection, C2C12 myoblasts were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). The cells were cultured to 70% confluency, then transfected with the control, mutant, GST only, or empty vector constructs using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent in Opti-MEM (Gibco) medium according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). At 48 hours post-transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4). Protein concentration was determined with the BioRad DC Protein Assay kit. For GST pull downs, the cell lysates were incubated with glutathione-agarose beads (ThermoFisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C under gentle rotation. After incubation, the beads and bound proteins were washed 4 times, and eluted in sample loading buffer by boiling for 10 min at 100°C. Whole cell lysates and GST pull downs were loaded onto 4-12% SDS-PAGE gels for immunoblotting analysis as described previously [4]. Primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: anti-syntrophin (ThermoFisher Scientific), anti-GST (Cell Signaling), and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). Immunoblotting was performed in triplicate.

2.7. RNA sequencing

We performed bulk transcriptome sequencing (RNAseq) as previously described [1, 36-38] on muscle biopsy samples from 3 affected individuals in family A and compared the data to muscle RNAseq data from 33 healthy control subjects, 132 individuals with myositis (44 with dermatomyositis, 18 with antisynthetase syndrome, 54 with immune-mediated necrotizing myositis, and 16 with inclusion body myositis). Briefly, RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries were either prepared with the NeoPrep system according to the TruSeqM Stranded mRNA Library Prep protocol (Illumina), or with the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module and Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs; #E7490 and #E7760).

Reads were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq/2.20.0 and preprocessed using fastp/0.21.0. The abundance of each gene was generated using Salmon/1.5.2 and quality control output was summarized using multiqc/1.11. Counts were normalized using the Trimmed Means of M values (TMM) from edgeR/3.34.1 for graphical analysis. Differential expression was performed using limma/3.48.3.

For visualization purposes, we used the ggplot2/3.3.5 package of the R programming language.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test and Student t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test were performed. P-values are indicated by the following symbols: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism v.8.0.2 (GraphPad Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.9. Data availability

Any data not published within the article will be shared by the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical features

Most affected individuals reported myalgia and exercise intolerance (10/12), with a variable age of onset, ranging from early childhood to the fourth decade of life. Exercise intolerance was defined as a significant decrease in the ability to perform moderate age-appropriate physical activities. Muscle weakness was not detected in any affected members of family A, but mild proximal lower limb weakness (Medical Research Council (MRC) Scale for Muscle Strength: 4/5) was identified in three of the affected individuals of families B and C. Muscle cramps associated with physical activity were reported by affected individuals from families A and C. No cramping or myotonia was elicited by hand grip in any individual. Calf hypertrophy was not reported in any individual. A persistent elevation of serum CK was detected in 11/12 affected individuals from the four families (Table 1). Individual A.III.1 had an episode of rhabdomyolysis with a peak serum CK of 87,800 IU/L at 20 years. Two affected individuals (B.III.3 and D.III.2) were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, and two additional individuals (B.I.1 and C.II.1) were reported to have milder neurodevelopmental issues; all four of these individuals harbor the DTNA c.1567_1587 deletion; brain MRI scans were not performed on any of these individuals, though D.III.2 had an electroencephalogram that was normal (Table 1). In contrast, none of the individuals from family A, with the DTNA c.1585G>A variant, showed cognitive impairment.

Table 1. Clinical features of individuals with dominantly inherited variants in DTNA.

Abbreviations: M = male; F = female; y= years; IU= International Units; NA/NP= Not available/Not performed.

| Individual | Family | Sex | Age last exam |

CK (IU/L) | Muscle weakness |

Myalgias | Exercise intol |

Rhabdomyolisis | Muscle biopsy | Cognitive impairment |

Genetic variant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.II.2 | A | M | 55y | 1780 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Variability in fibre size, fibres with internalized nuclei, irregular intermyofibrillar pattern, slightly increased endomysial and/or perimysial connective tissue. | No | c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys) |

| A.II.4 | A | F | 51y | 150-200 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Not performed | No | c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys) |

| A.II.7 | A | F | 49y | 380 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Variability in fibre size, fibres with internalized nuclei, irregular intermyofibrillar pattern, slightly increased endomysial and/or perimysial connective tissue. | No | c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys) |

| A.III.1 | A | M | 24y | 830-1590 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Variability in fibre size, fibres with internalized nuclei, irregular intermyofibrillar pattern, slightly increased endomysial and/or perimysial connective tissue. | No | c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys) |

| A.III.2 | A | F | 18y | 490-3990 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Variability in fibre size, fibres with internalized nuclei, irregular intermyofibrillar pattern, slightly increased endomysial and/or perimysial connective tissue. | No | c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys) |

| B.I.1 | B | M | 70’s | elevated | No | No | No | Unknown | Not performed | Learning delay | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

| B.II.4 | B | M | 40’s | elevated | No | Yes | No | Unknown | Internalized nuclei and focal areas of inflammation involving connective tissue. Mild to moderate fiber atrophy without regeneration. It was felt that the findings suggested myositis. | No | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

| B.III.1 | B | M | 8y | 3000-3500 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Not performed | Unknown | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

| B.III.3 | B | M | 16y | 4000-6000 | Yes (onset at 8y) | Yes | Yes | No | Severe fiber size variation, striking patchy endomysial and perimysial inflammation, focal patchy aggregates of regenerating fibers, some of which contain vacuoles. The inflammatory infiltrate is composed of lymphocytes, significant numbers of eosinophils and rare neutrophils and is centered on myofibers as well as blood vessels. | Autism spectrum disorder & ADHD | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

| C.II.1 | C | M | 12y | 8000 | Yes (hip adduction and hip extension 4+/5) | Yes | Yes | No | Mild myopathic features including internalized nuclei and type 1 fiber predominance | Learning disability | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

| D.II.3 | D | M | 43y | 388 | No | No | No | Unknown | Not performed | Unknown | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

| D.III.2 | D | M | 8y | 2500-5100 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Mild variation in fiber size, slight increase in internalized nuclei, focal rare endomysial lymphocytes and rare foci of myophagocytosis. Small foci of basophilic regenerative fibers are seen. | Autism spectrum disorder | c.1567_1587; p.(523_529del7) |

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography performed on individuals A.II.4 at the age of 51 years and C.II.1 at the age of 8 years demonstrated normal conduction velocities and low-amplitude, short duration motor unit potentials, consistent with a myopathic condition without membrane irritability. There was no evidence of a neuromuscular junction disorder since repetitive nerve stimulation in distal muscles at 3 and 50 Hz did not show a decremental or incremental response, respectively. Single fiber electromyography was not performed. Active fasciculations in the deltoid, biceps, triceps, forearm flexors, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius and hamstrings were detected on muscle ultrasound in individual C.II.1 at 12 years. An ischemic forearm exercise test performed in individual A.III.2 showed a normal trajectory of plasma lactate and ammonia levels during the test. Whole-body MRI of individual A.III.2 at 14 years revealed T1 signal hyperintensity suggestive of a mild focal fatty replacement in the gluteus maximii and tensor fascia latae, with no signs of oedema, while a lower extremity muscle MRI in individual C.II.1 at 12 years showed normal muscle bulk and signal intensities of all muscles (Supplementary Figure S1, online resource). Cardiac evaluations with echocardiography performed in individuals A.II.2, A.III.1, A.III.2, and C.II.1 at 54, 23, 18, and 12 years, respectively, were normal. Liver transaminases of all individuals were normal, as well as an abdominal ultrasound performed on individual A.III.2. Liver biopsy performed in individual C.II.1 at the age of 8 years showed rare foci of lobular inflammation and portal tracts with minimal ductular reaction and no evidence for glycogen storage disease, suggestive of a mild nonspecific reactive hepatitis.

3.2. Molecular genetic findings

WES identified the heterozygous DTNA (MIM*601239) variant [chr18:34,863,985G>A (GRCh38/hg38)] (NM_001390.5; c.1585G>A, p.(Glu529Lys)) in individual A.III.2, and a heterozygous in frame deletion in DTNA [chr18:34,863,966-34,863,986 (GRCh38/hg38)] (NM_001390.5; c.1567_1587del, p.(Gln523_Glu529del)) in individuals B.I.1, B.II.4, B.III.1, B.III.3, C.I.1, C.II.1, D.II.3, and D.III.2. These variants were absent from population databases [21], affected highly conserved residues of the protein and were predicted to be pathogenic by in silico predictors: variant c.1585G>A has a CADD score of 32 and variant c.1567_1587del a CADD score of 22.2 (Supplementary Table S2, online resource). Pathogenic variants in DTNA were not identified in the WES performed in the unaffected individuals B.I.2, B.II.1, B.II.3, C.I.2, and D.II.4. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the heterozygous c.1567_1587del variant in the 4 affected members of family B and its absence in the unaffected members of family B.

Segregation analysis performed by Sanger sequencing in the members of family A identified the heterozygous c.1585G>A variant in the five affected members of family A (A.II.2, A.II.4, A.II.7, A.III.1, A.III.2), while it was absent in the four unaffected members who were sequenced (A.II.1, A.II.3, A.II.5, A.II.6) (Figure 1).

No other pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in DTNA or other genes, except the monoallelic variant POMGNT1 (NM_001243766.1): c.187C>T, p.Arg63* that was found in individual A.III.2 and in her asymptomatic mother (A.II.1) but not in her affected brother (A.III.1) or in other relatives. No pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in SGCA, SGCB, SGCG, SGCD or any other known muscular dystrophy gene were identified in any of the exomes from affected individuals.

3.3. In silico and in vitro pathogenic role of novel DTNA variants

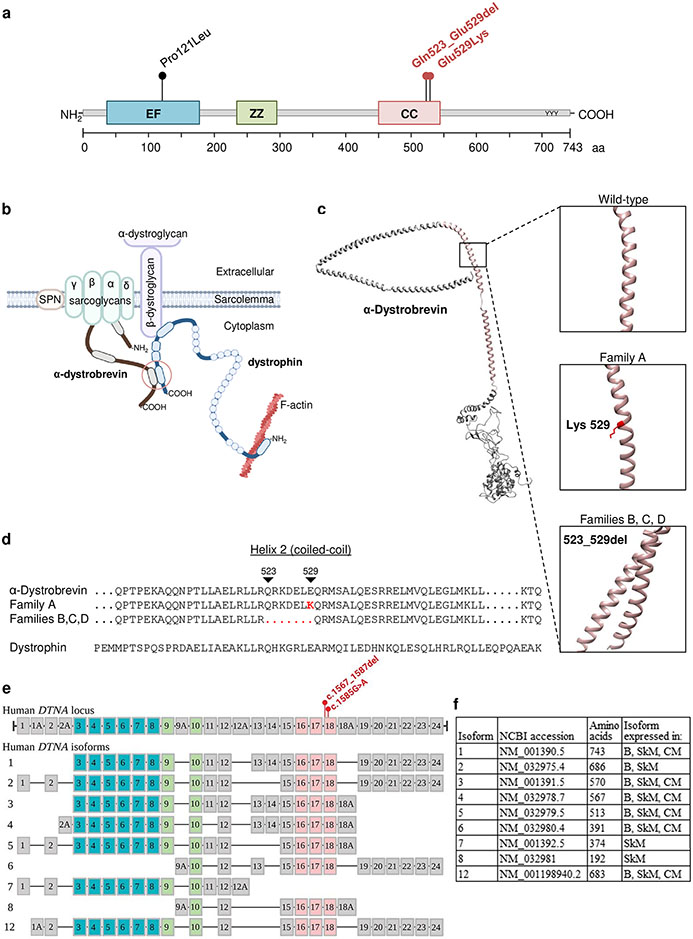

Both variants DTNA c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys) and c.1567_1587del; p.(Gln523_Glu529del) are located in the second helix of the coiled-coil domain of α-dystrobrevin. This coiled-coil domain mediates the interaction with dystrophin, indicating that α-dystrobrevin acts as a structural scaffold linking the DGC to the intracellular cytoskeleton (Figure 2 a-b). Structural protein prediction tools suggest that the variants introduce subtle changes in the secondary structure of the protein (Figure 2 c-d). Based on data from gnomAD, DTNA is not tolerant to loss-of-function variants [21], and MetaDome showed that the variants were located in a region mostly intolerant to genetic variation [48] (Supplementary Figure S2, online resource). Figure 2 e-f shows the genomic structure of human DTNA and common isoforms, including notations of the locations of the two variants found in the four families.

Figure 2. In silico analyses of α-dystrobrevin variants found in the four families included in our cohort.

(a) α-dystrobrevin domain structure (Uniprot: Q9Y4J8) and location of the variants found in families A, B, C, and D (in red), as well as the previously reported variant associated with left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) cardiomyopathy (in black). (b) Partial schematic representation of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (DGC). (c) Modeled 3D structure of wild-type α-dystrobrevin with coiled-coil domain indicated in salmon. Wild-type and affected individuals modeled residues indicated in boxes. All residues in all 3D structures were modelled at >90% confidence using Phyre2 software. (d) Sequence alignment of part of the coiled-coil domains of wild-type and mutated α-dystrobrevin and wild-type dystrophin. Abbreviations: EF, EF hand region; ZZ, zinc-binding domain; CC, coiled-coil. (e) The genomic structure of human DTNA indicating the two variants found in the four families. Also shown is a schematic representation of the exons included in 9 isoforms of DTNA that are expressed in skeletal muscle. Exons encoding the calcium-binding EF hand domains are shaded in teal, exons encoding the zinc finger domains are shaded in lime green, and exons encoding the coiled-coil domain are shaded in salmon. (f) The selected DTNA isoforms (Uniprot: Q9Y4J8-1 through Q9Y4J8-8 and Q9Y4J8-13) are listed with National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) transcript accession number, number of amino acids, and tissues in which the isoforms are highly expressed. B, brain; SkM, skeletal muscle; CM, cardiac muscle.

3.4. Morphological findings in muscle biopsies

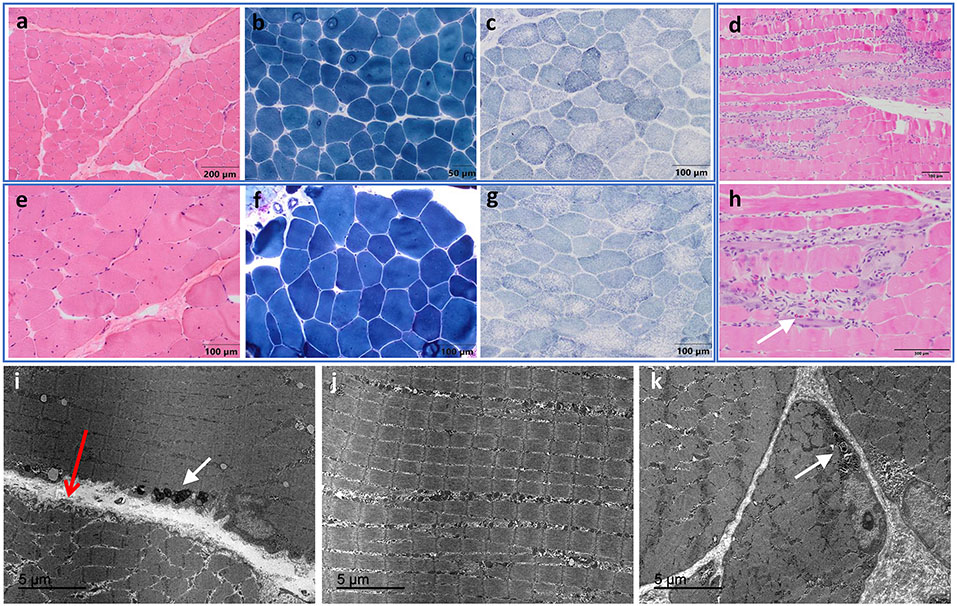

Muscle biopsies were performed on 8 individuals (4 individuals from family A, 2 individuals from family B, 1 individual from family C, and 1 individual from family D) at a mean age of 27 years (range: 8-48 years). The main features of muscle biopsies are shown in Figures 3 and 4 and in Table 1 and 2. Muscle histology showed variability in fibre size, some fibres with internalized nuclei, and irregular intermyofibrillar pattern, with some areas devoid of staining for oxidative enzymes (NADH and SDH). Fibre splitting and a few regenerating fibres were detected. Slightly increased endomysial or perimysial connective tissue with fibrosis or fatty infiltration was observed. Muscle biopsy obtained from the quadriceps on individual B.III.3 at 8 years of age showed fiber necrosis and regenerating fibers.

Figure 3. Muscle histology findings from biopsies of individuals with pathogenic DTNA variants.

The biopsy from individual A.III.2 was taken at 17 years (a-c) and the biopsy from individual A.III.1 at 23 years (e-g). Variability in fibre size (range: 31-105 μm in individual A.III.2; range: 37-178 μm in individual A.III.1) and fibres with internalized nuclei (10.9% in individual A.III.2 and 26% in individual A.III.1) were observed on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and modified Gomori trichrome stainings, as well as slightly increased endomysial or perimysial connective tissue with fibrosis or fatty replacement (a, b, e, f). An irregular intermyofibrillar pattern, with small areas devoid of staining for oxidative enzymes, were identified with SDH (c, g). Biopsy of individual B.III.3 showed necrotic and regenerating muscle fibers, as well as some eosinophils (white arrow in h) (d, h). Electron microscopy performed in individual A.III.1 showed muscle fibres with fibre size variability and normal sarcomeric structure. (i-k) Slight folds into the extracellular space were observed in the sarcolemma, as well as minimal redundancy of the basement membrane into the extracellular space, with no thickening of the basal lamina (long thin red open arrow in i). Note that the orientation of the lower fiber is not optimal. Non-specific lipofuscin granules (white arrow in i) and pseudomyelinic debris (white arrow in k) were observed. Scale bars are indicated in the panels.

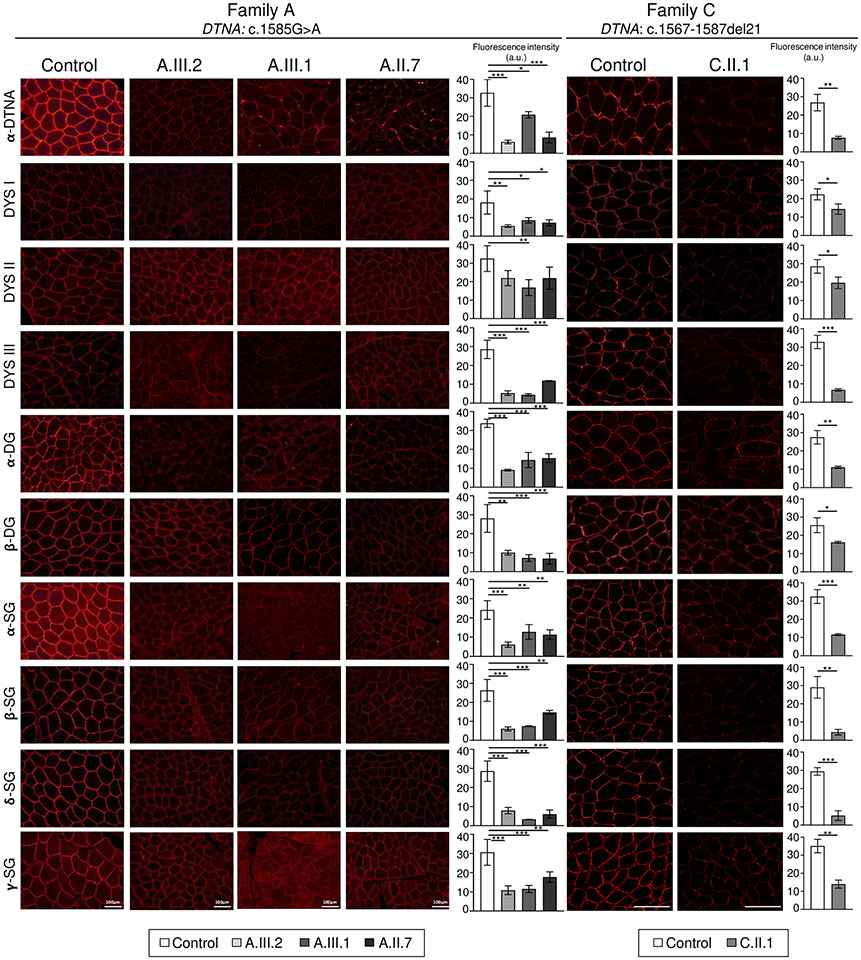

Figure 4. Immunofluorescence showed significantly reduced signal intensity in several sarcolemmal proteins in individuals from families A and C, who carry the DTNA c.1585G>A; p.Glu529Lys and c.1567_1587del21; p.Gln523_Glu529del7 variants.

Representative images of α-dystrobrevin and different dystrophin-glycoprotein complex proteins in healthy controls and affected individuals (family A: A.III.2, A.III.1, A.II.7; family C: C.II.1) and quantification of fluorescence intensity signal (mean ± SD; n = 3; statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test (family C) and one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test (family A). *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. In addition to reduced α-dystrobrevin immunoreactivity at the sarcolemma, variable reductions in immunoreactivity levels of other proteins in the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex were identified, including dystrophin, α, β, δ and γ-sarcoglycans and α and β-dystroglycans. β-DG, β-dystroglycan; DYS1, dystrophin antibody 1 (rod domain); DYS2, dystrophin antibody 2 (C-terminal domain); DYS3, dystrophin antibody 3 (N-terminal domain); α-DG, α-dystroglycan; α-SG, α-sarcoglycan; β-SG, β-sarcoglycan; δ-SG, δ-sarcoglycan; γ-SG, γ-sarcoglycan; α-DTNA, α-dystrobrevin. Scale bars, 100 μm; a.u., arbitrary units.

Table 2. Variability of sarcolemmal protein reduction in several individuals with DTNA-related muscular dystrophy with the same variant DTNA c.1585G>A; p.Glu529Lys (family A) and with variant c.1567_1587del21; p.Gln523_Glu529del7 (family C).

| A.III.2 | A.III.1 | A.II.7 | A.II.2 | C.II.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-spectrin | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | |

| DYS1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| DYS2 | +++ | + | ++++ | ++ | + |

| DYS3 | + | − | ++++ | + | + |

| Beta-dystroglycan | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ | +++ |

| Alpha-dystroglycan (VIA4) | ++ | + | ++++ | ++ | |

| Alpha-dystroglycan (IIH6) | + | + | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Alpha-sarcoglycan | +++ | − | ++ | + | + |

| Beta-sarcoglycan | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Delta-sarcoglycan | +++ | + | +++ | + | |

| Gamma-sarcoglycan | ++ | + | +++ | + | + |

| Alpha-dystrobrevin | +++ | ++ | + | + | + |

++++ = normal staining; +++ = mildly diminished; ++ = moderately diminished; + = severely diminished; − = absent.

Immunofluorescence analysis of the muscle samples from 4 affected individuals (3 from family A (DTNA c.1585G>A; p.(Glu529Lys)) and 1 from family C (DTNA c.1567-1587del; p.(Gln523_Glu529del)) demonstrated consistently reduced α-dystrobrevin immunoreactivity at the sarcolemma, as well as variably reduced immunoreactivity levels of several other proteins within the DGC, including dystrophin, α, β, δ and γ-sarcoglycans, and α and β-dystroglycans (Figure 4 and Table 2). A total absence of any of the proteins studied was not observed in any biopsy that was examined via immunofluorescence.Ten neuromuscular junctions were identified in the muscle biopsy of individual A.III.1 on immunofluorescence. The morphology of these neuromuscular junctions was slightly different from that of the neuromuscular junctions of a control specimen: the neuromuscular junctions of individual A.III.1 were thinner, in contrast to the large “crescent moon” appearance of a typical neuromuscular junction (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Neuromuscular junction imaging.

Immunofluorescence stains for α-dystrobrevin were merged with images of fluorescently-labeled α-bungarotoxin staining acetylcholine receptors to show that the neuromuscular junctions in individual A.III.1 were thinner compared to control neuromuscular junctions (arrows). Scale bars: 50 μm.

Electron microscopy performed on the biopsy from individual A.III.1 showed muscle fibres with variability in size and normal sarcomeric structure. In the sarcolemma, slight folds into the extracellular space were observed, as well as minimal redundancy of the basement membrane in the extracellular space, with no thickening of the basal lamina. Non-specific findings included lipofuscin granules and pseudomyelinic debris that were in the normal range (Figure 3).

3.5. Analysis of α-dystrobrevin expression and protein-protein interactions

In contrast to the reduced immunoreactivity at the sarcolemma found on immunofluorescence of histological slides, no alterations in protein expression levels of α-dystrobrevin were detected on western blot analysis of total protein extracts from muscle biopsy samples from affected individuals of family A. Western blots showed decreased expression of α, δ, and γ-sarcoglycans in muscle representing individuals from family A compared to controls, whereas protein expression levels of dystrophin using antibodies DYS1, DYS2 and DYS3 in individuals from family A were normal (Supplementary Figure S3, online resource).

An interaction between full-length α-dystrobrevin and syntrophin was detected by GST pulldown and immunoblotting assays. This interaction was disrupted when a variant-DTNA construct containing the c.1567_1587 deletion was expressed in C2C12 myoblasts (Figure 6). Proliferation, migration, and differentiation/fusion assays performed on C2C12 myoblasts transiently transfected with wild type DTNA fused to GST and a DTNA construct containing the c.1567_1587 deletion, also fused to GST, showed decreased proliferation of cells transfected with the DTNA c.1567_1587 deletion construct compared to those transfected with the WT-DTNA construct, with no differences in migration and differentiation/ myoblast fusion patterns (Supplementary Figure S4, online resource).

Figure 6. Immunoprecipitation and GST pulldown assays.

(a) Lysates were prepared from C2C12 cells that were transiently transfected with WT-DTNA (WT) fused to GST, variant-DTNA (Del) fused to GST, and empty vector containing GST as a negative control (EV). We also included a non-transfected cell control (NT). Input and GST pull downs were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-syntrophin, anti-GST, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (the asterisk indicates the GAPDH band). The anti-syntrophin immunoblot of the GST pull down shows decreased syntrophin for the deletion construct versus WT-DTNA, while the anti-GST immunoblot shows no discernable difference in α-dystrobrevin levels. In contrast, anti-syntrophin immunoblot of the whole cell lysate reveals no discernable differences in syntrophin levels. Anti-GAPDH was used as a loading control. (b) Quantification of syntrophin in GST pulldowns normalized to GST-α-dystrobrevin.

3.6. Transcriptome analysis

The expression levels of the 65 known DTNA transcripts were quantified from the RNAseq data. Among these, only transcript ENST00000681470 displays significant overexpression and none of the transcripts have significantly reduced expression in the skeletal muscle samples analysed from 3 individuals with the DTNA c.1585G>A variant compared to controls (data not shown).

4. Discussion

Here we present 12 individuals from four families who harbor monoallelic DTNA variants in the setting of persistent hyperCKemia (n=11), myalgia (n=10), exercise intolerance (n=9), rhabdomyolysis (n=1), and proximal muscle weakness in the lower limbs (n=3). Our findings suggest that variants in the coiled-coil domain of α-dystrobrevin lead to a mild skeletal muscle phenotype with variable penetrance. The p.Gln523_Glu529del deletion is associated with a more severe clinical phenotype, involving muscle weakness, while the p.Glu529Lys missense variant results in a milder phenotype of hyperCKemia, myalgia and exercise intolerance. It is notable that the coiled-coil domain of α-dystrobrevin mediates the interaction with dystrophin and its utrophin homolog, and no other pathogenic missense variants in this domain have been previously described in humans. The central nervous system manifestations in a few affected individuals are intriguing. α-dystrobrevin is expressed in multiple brain regions in humans [45] and zebrafish [3], suggesting that DTNA variants may be associated with neurodevelopmental impairments. Specifically, expression of DTNA rises during the late prenatal period, followed by a plateau and a potential slow decline after early childhood [45]. Based on these findings, Simon et al suggested that the elevated expression of DTNA at the earliest stages of astrogliogenesis may reflect a role of astrocytes in distributing secreted factors critical to developmental processes such as blood brain barrier maintenance and neuronal maturation [45].

Immunofluorescence of muscle biopsy specimens showed a marked reduction in α-dystrobrevin at the membrane, as well as of other components of the DGC, suggesting that potential mechanisms by which the variants p.Glu529Lys and p.Gln523_Glu529del give rise to the dystrophic phenotype may include disrupted interactions between α-dystrobrevin and one or more proteins in the DGC, thereby destabilizing the complex with reduced immmunohistochemical localization of multiple components at their expected membrane based location. In contrast to the immunohistochemical deficit at the membrane, western blots did not show a corresponding depletion of α-dystrobrevin in total muscle lysates from affected individuals. While the antibodies used for the two assays were different (the antibody we used for immunofluorescence targets the inner region of α-dystrobrevin (amino acids 366-422), whereas the antibody used for the Western blot targets the c-terminal region of α-dystrobrevin (amino acids 600-743) (Supplementary Figure S3, online resource), the targeted regions do not include the amino acids affected by the variants in our cohort. A more plausible explanation for the discordant findings between our immunohistochemical and western blot studies is that some variant forms of α-dystrobrevin such as the ones in our cohort are not able to localize properly to the DGC, leading to a dominant negative effect characterized by the destabilization of other components of the DGC while the total amount of α-dystrobrevin protein present in muscle remains unchanged. In support of this hypothesis we found that the interaction between α-dystrobrevin and syntrophin was disrupted by a mutant-DTNA construct containing the c.1567_1587 deletion. Also consistent with this scenario is that α-dystrobrevin interacts directly with dystroglycans through its EF domain [7]. As strong mechanical dissociation techniques were not applied to solubilize the muscle proteins prior to our western blots, another possible explanation for the discordant findings is that the variants reported here could lead to the formation of soluble aggregates, which would be an alternative explanation for the diminished expression of α-dystrobrevin on immunofluorescence but not on western blot.

A different monoallelic pathogenic variant in DTNA, (NM_001390.5) c.362C>T; p.(Pro121Leu), was previously identified in six individuals from one family with left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy [17] and more recently a different DTNA variant (NM_ 001198943.1) c.681G>C; p.(Glu227Asp) was associated with atrial fibrillation in another family; however, there are genotype-phenotype discordances in the latter family that were not resolved [26]. Neither hyperCKemia nor other skeletal muscle symptoms were described in any of the affected individuals in these two reports. No cardiac involvement was detected in any of the affected individuals in our cohort, suggesting a lack of overlap in these two phenotypes to date. The locations of the variants associated with muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy in different domains suggest that (i) the location of pathogenic variants in DTNA has a significant influence on the associated clinical phenotype and (ii) the coiled-coil domain of α-dystrobrevin is sensitive to variants that alter the structure and interactions of the DGC in skeletal muscle. This interpretation is supported by the high levels of conservation of the coiled-coil domain across evolutionarily divergent species, and the interaction between α-dystrobrevin and dystrophin at the coiled-coil domain. The identification of additional affected individuals and natural history data will be crucial to developing a better understanding of the phenotypic spectrum and long-term clinical manifestations of this form of muscular dystrophy, which is milder than the phenotype observed in Dtna knockout mice [14]. The absence of individuals reported to have biallelic pathogenic variants in DTNA suggests that a complete lack of DTNA in humans may be consequential enough to be incompatible with life.

In addition to being localised at the sarcolemma, α-dystrobrevin is abundant at the neuromuscular junction, especially at the crest of the junctional folds, with a key role in tethering acetylcholine receptors to the postsynaptic membrane [2]. In the affected individuals presented here, no typical symptoms of neuromuscular junction involvement were detected, including fatigability on clinical examination, ptosis or a decrement in compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitude after low frequency repetitive stimulation, thus we did not investigate whether either of the variants reported here disrupted normal acetylcholine receptor tethering. However, in the muscle biopsy of one affected individual we identified ten neuromuscular junctions with a slightly abnormal morphology, as they were thinner than those of the control (Figure 3). These findings should be interpreted with caution due to the variable labelling of neuromuscular junctions in cryostat sections and the limited number of visualized neuromuscular junctions. Future studies of the potential effects of variant forms of α-dystrobrevin on the neuromuscular junction would be illuminating, and it is possible that individuals with pathogenic variants in other domains of DTNA will be found to have a myasthenic phenotype in the future.

α-dystrobrevin is an integral and evolutionarily conserved component of the DGC (Supplementary Figure S5, online resource) [35]. Studies in multiple model organisms including the mouse (Mus musculus), zebrafish (Danio rerio), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) and nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans) have shown that dystrobrevin orthologs in these species (Dtna, dtna, Dyb and dyb-1, respectively) are expressed in skeletal muscles as well as in the central nervous system [3, 9]. The generation of Dyb-deficient animal models in these species facilitated investigations of this protein’s function at the post-synaptic neuromuscular junction, where it is enriched. Loss-of-function Dyb mutant organisms are viable; however abnormalities in motor activity, muscle fiber integrity, neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction, and neuromuscular junction structure have been reported in multiple species (Supplementary Table S3, online resource). These studies revealed an important role for DTNA/Dyb at the neuromuscular junction [16, 19].

Dominant forms of muscular dystrophy remain much less common than recessive forms, as illustrated by the genetic distribution seen in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) [46]. This likely reflects to some extent the true epidemiologic patterns in the muscular dystrophy population, but as our study shows, genetic analyses of dominant families are often hampered by milder phenotypes than are seen in recessive families, as is the case in some individuals with LGMD-1D [49]. This raises the possibility of phenotyping errors that could confound segregation analyses of candidate pathogenic variants as well as linkage analysis [24]. Thus, we believe that dominant forms of muscular dystrophy may be under-recognized and that additional genes with dominantly inherited causative variants are likely to be discovered in the future.

In summary, we provide clinical, genetic, and histopathological evidence for the pathogenicity of particular autosomal dominant variants in a specific domain of α-dystrobrevin, as well as a notable expansion of the phenotypic spectrum associated with DTNA to muscular dystrophy. Our observations suggest that the coiled-coil domain of α-dystrobrevin is intolerant of genetic variation in skeletal muscle. The identification of additional affected individuals will assist in a more comprehensive description of the phenotypic spectrum and long-term clinical manifestations of DTNA-associated muscular dystrophy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1 (online resource). T1-weighted MRI sequences of shoulder girdle (a), pelvic girdle (b), thighs (c), and calves (d) of individual A.III.2 at 14 years of age revealed T1 signal hyperintensity suggestive of very mild focal fatty replacement in the gluteus maximii and tensor fascia latae.

Supplementary Figure S2 (online resource). Variants DTNA c.1585G>A; p.Glu529Lys and c.1567-1587del21; p.Gln523_Glu529del7 are located in a region mostly intolerant to genetic variation. The tolerance to variation analysed with Metadome is showed for (1) α-dystrobrevin, (2) coiled-coil domain, (3) the second helix, and (4) the location of the variants.

Supplementary Figure S3 (online resource). Western blots of α-dystrobrevin (antibody targeting C-terminus), dystrophin and sarcoglycans (α, γ, and δ) were performed on protein lysates from muscle biopsy samples representing three affected individuals and one control. α-dystrobrevin and dystrophin showed comparable band intensities in affected samples and the control. Sarcoglycan band intensities were reduced in all affected individuals compared to control.

Supplementary Figure S4 (online resource). Proliferation, migration, and differentiation/myoblast fusion assays were performed on C2C12 myoblasts that were transiently transfected with wild type DTNA (WT-DTNA) fused to GST, variant-DTNA (Del-DTNA) fused to GST, and empty vector containing GST as a control. The Del-DTNA construct contains the c.1567_1587 deletion. (a) Direct cell counts showed a decrease at 24 hours post-transfection in proliferation of cells transfected with Del-DTNA as compared to WT-DTNA. Cyquant assays showed corresponding decreases at 24 and 48 hours post-transfection in cells transfected with Del-DTNA compared to WT-DTNA. (b) Scratch-test assays of C2C12 migration showed no visible differences in cell migration at 24 and 48 hours post-transfection between cells transfected with WT-DTNA, Del-DTNA, and empty vector. (c) There were no visible differences in differentiation and myoblast fusion between C2C12 cells transfected with WT-DTNA and Del-DTNA, based on desmin and DAPI staining.

Supplementary Figure S5 (online resource). A high degree of conservation was found between DTNA and its orthologs across species. (a) Clustal O (1.2.4) multiple sequence alignment of human, mouse, zebrafish, fruit fly, and worm protein sequences. (b) Expasy prosite analysis of protein domains and functional sites showing the presence of the zinc finger (ZZ) domain in all analyzed species. The ZZ domain which binds two zinc ions was first identified in dystrophin homologs [39], and is required for dystrophin and utrophin to bind β-dystroglycan [18].

Supplementary Table S1 (online resource). List of antibodies used in studies for inmmunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence and western-blot.

Supplementary Table S2 (online resource). Pathogenic effect of DTNA genetic variants found in the individuals of this study. Allele frequency in the total population (gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database) and in the Spanish population (CSVS, Collaborative Spanish Variant Server). Genetic variant classification based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines, using VarSome (last accessed June 7, 2022). Variant effect predictors used were: FATHMM-MKL, Mutation taster, and DANN (with scores ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 is the most damaging), PROVEAN (with scores equal or below −2.5 being deleterious and above −2.5 being neutral), CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion) (with scores ≥ 20 indicating that the variant is predicted to be among the 1% of the most deleterious substitutions in the human genome). Abbreviations: NR, not reported; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Supplementary Table S3 (online resource). Summary of phenotypes observed in DTNA/α-dystrobrevin loss-of-function (LOF) mutants in different model organisms [6, 12-15, 19].

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the “Biobanc de l’Hospital Infantil Sant Joan de Déu per a la Investigació”, part of the Spanish Biobank Network of ISCIII for the sample and data procurement.

Financial Disclosure Statement:

Daniel Natera-de Benito was supported by the Miguel Servet program from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (CP22/00141).

Jordi Pijuan was supported by a Carmen de Torres fellowship of the SJD Research Institute.

Francesc Palau was supported by Fundacion Isabel Gemio and AGAUR (2017 SGR 324).

Janet Hoenicka was supported by the Torro Solidari-RAC1 i Torrons Vicens.

The work in Peter B. Kang's laboratory was supported in part by NIH R01 NS080929.

The work in Louis M. Kunkel's laboratory was supported in part by NIH R01AR064300 and the Bernard F. and Alva B. Gimbel Foundation.

Work in Carsten G. Bönneman’s laboratory is supported by intramural funds by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Sequencing and analysis of families C and D were provided by the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Center for Mendelian Genomics (Broad CMG) and was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Eye Institute, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant UM1HG008900 and in part by National Human Genome Research Institute grant R01HG009141.

The other authors report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethics/Consent to participation This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu Clinical Research Ethics Committee (reference PIC-04-18). Data were collected in accordance with ethical guidelines of each of the institutions involved. Written informed consent for study participation was obtained by qualified clinicians.

Data availability

Any data not published within the article will be shared from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Amici DR, Pinal-Fernandez I, Mázala DAG, Lloyd TE, Corse AM, Christopher-Stine L, Mammen AL, Chin ER (2017) Calcium dysregulation, functional calpainopathy, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in sporadic inclusion body myositis. Acta neuropathologica communications 5:24. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0427-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belhasan DC, Akaaboune M (2020) The role of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex on the neuromuscular system. Neuroscience Letters 722:134833. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.134833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Böhm S, Jin H, Hughes SM, Roberts RG, Hinits Y (2008) Dystrobrevin and dystrophin family gene expression in zebrafish. Gene Expression Patterns 8:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruels CC, Li C, Mendoza T, Khan J, Reddy HM, Estrella EA, Ghosh PS, Darras BT, Lidov HGW, Pacak CA, Kunkel LM, Modave F, Draper I, Kang PB (2019) Identification of a pathogenic mutation in ATP2A1 via in silico analysis of exome data for cryptic aberrant splice sites. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine 7:e552. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cagliani R, Comi GP, Tancredi L, Sironi M, Fortunate F, Giorda R, Bardoni A, Moggio M, Prelle A, Bresolin N, Scarlato G (2001) Primary beta-sarcoglycanopathy manifesting as recurrent exercise-induced myoglobinuria. Neuromuscular Disorders 11:389–394. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(00)00207-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen B, Liu P, Zhan H, Wang ZW (2011) Dystrobrevin controls neurotransmitter release and muscle Ca 2+transients by localizing BK channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Neuroscience 31:17338–17347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3638-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung W, Campanelli JT (1999) WW and EF hand domains of dystrophin-family proteins mediate dystroglycan binding. Molecular Cell Biology Research Communications 2:162–171. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.1999.0168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davydov EV, Goode DL, Sirota M, Cooper GM, Sidow A, Batzoglou S (2010) Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++. PLoS Computational Biology 6:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekkers LC, van der Plas MC, van Loenen PB, den Dunnen JT, van Ommen GJB, Fradkin LG, Noordermeer JN (2004) Embryonic expression patterns of the Drosophila dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex orthologs. Gene Expression Patterns 4:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2003.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.<B/>Dubowitz V, Sewry C, Oldfors A (2013) Muscle Biopsy: A Practical Approach, 4th editio. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, USA [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figarella-Branger D, Machado AMB, Putzu GA, Malzac P, Voelckel MA, Pellissier JF (1997) Exertional rhabdomyolysis and exercise intolerance revealing dystrophinopathies. Acta Neuropathologica 94:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s004010050671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gieseler K, Mariol MC, Bessou C, Migaud M, Franks CJ, Holden-Dye L, Ségalat L (2001) Molecular, genetic and physiological characterisation of dystrobrevin-like (dyb-1) mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Molecular Biology 307:107–117. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grady RM, Akaaboune M, Cohen AL, Maimone MM, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR (2003) Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated isoforms of α-dystrobrevin: Roles in skeletal muscle and its neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions. Journal of Cell Biology 160:741–752. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grady RM, Grange RW, Lau KS, Maimone MM, Nichol MC, Stull JT, Sanes JR (1999) Role for α-dystrobrevin in the pathogenesis of dystrophin-dependent muscular dystrophies. Nature Cell Biology 1:215–220. doi: 10.1038/12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grady RM, Wozniak DF, Ohlemiller KK, Sanes JR (2006) Cerebellar synaptic defects and abnormal motor behavior in mice lacking α- and β-dystrobrevin. Journal of Neuroscience 26:2841–2851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4823-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady RM, Zhou H, Cunningham JM, Henry MD, Campbell KP, Sanes JR (2000) Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse: Genetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Neuron 25:279–293. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80894-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichida F, Tsubata S, Bowles KR, Haneda N, Uese K, Miyawaki T, Dreyer WJ, Messina J, Li H, Bowles NE, Towbin JA (2001) Novel gene mutations in patients with left ventricular noncompaction or Barth syndrome. Circulation 103:1256–1263. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.9.1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa-Sakurai M, Yoshida M, Imamura M, Davies KE, Ozawa E (2004) ZZ domain is essentially required for the physiological binding of dystrophin and utrophin to β-dystroglycan. Human Molecular Genetics 13:693–702. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jantrapirom S, Nimlamool W, Temviriyanukul P, Ahmadian S, Locke CJ, Davis GW, Yamaguchi M, Noordermeer JN, Fradkin LG, Potikanond S (2019) Dystrobrevin is required postsynaptically for homeostatic potentiation at the Drosophila NMJ. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 1865:1579–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones KJ, Compton AG, Yang N, Mills MA, Peters MF, Mowat D, Kunkel LM, Froehner SC, North KN (2003) Deficiency of the syntrophins and α-dystrobrevin in patients with inherited myopathy. Neuromuscular Disorders 13:456–467. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(03)00066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, Collins RL, Laricchia KM, Ganna A, Birnbaum DP, Gauthier LD, Brand H, Solomonson M, Watts NA, Rhodes D, Singer-Berk M, England EM, Seaby EG, Kosmicki JA, Walters RK, Tashman K, Farjoun Y, Banks E, Poterba T, Wang A, Seed C, Whiffin N, Chong JX, Samocha KE, Pierce-Hoffman E, Zappala Z, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Minikel EV, Weisburd B, Lek M, Ware JS, Vittal C, Armean IM, Bergelson L, Cibulskis K, Connolly KM, Covarrubias M, Donnelly S, Ferriera S, Gabriel S, Gentry J, Gupta N, Jeandet T, Kaplan D, Llanwarne C, Munshi R, Novod S, Petrillo N, Roazen D, Ruano-Rubio V, Saltzman A, Schleicher M, Soto J, Tibbetts K, Tolonen C, Wade G, Talkowski ME, Aguilar Salinas CA, Ahmad T, Albert CM, Ardissino D, Atzmon G, Barnard J, Beaugerie L, Benjamin EJ, Boehnke M, Bonnycastle LL, Bottinger EP, Bowden DW, Bown MJ, Chambers JC, Chan JC, Chasman D, Cho J, Chung MK, Cohen B, Correa A, Dabelea D, Daly MJ, Darbar D, Duggirala R, Dupuis J, Ellinor PT, Elosua R, Erdmann J, Esko T, Färkkilä M, Florez J, Franke A, Getz G, Glaser B, Glatt SJ, Goldstein D, Gonzalez C, Groop L, Haiman C, Hanis C, Harms M, Hiltunen M, Holi MM, Hultman CM, Kallela M, Kaprio J, Kathiresan S, Kim BJ, Kim YJ, Kirov G, Kooner J, Koskinen S, Krumholz HM, Kugathasan S, Kwak SH, Laakso M, Lehtimäki T, Loos RJF, Lubitz SA, Ma RCW, MacArthur DG, Marrugat J, Mattila KM, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Meigs JB, Melander O, Metspalu A, Neale BM, Nilsson PM, O’Donovan MC, Ongur D, Orozco L, Owen MJ, Palmer CNA, Palotie A, Park KS, Pato C, Pulver AE, Rahman N, Remes AM, Rioux JD, Ripatti S, Roden DM, Saleheen D, Salomaa V, Samani NJ, Scharf J, Schunkert H, Shoemaker MB, Sklar P, Soininen H, Sokol H, Spector T, Sullivan PF, Suvisaari J, Tai ES, Teo YY, Tiinamaija T, Tsuang M, Turner D, Tusie-Luna T, Vartiainen E, Ware JS, Watkins H, Weersma RK, Wessman M, Wilson JG, Xavier RJ, Neale BM, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG (2020) The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE (2015) The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nature Protocols 10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J (2014) A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nature Genetics 46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruglyak L, Daly MJ, Reeve-Daly MP, Lander ES (1996) Parametric and nonparametric linkage analysis: A unified multipoint approach. American Journal of Human Genetics 58:1347–1363 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Durbin R (2010) Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malakootian M, Jalilian M, Kalayinia S, Hosseini Moghadam M, Heidarali M, Haghjoo M (2022) Whole-exome sequencing reveals a rare missense variant in DTNA in an Iranian pedigree with early-onset atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 22:37. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-02485-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathews KD, Stephan CM, Laubenthal K, Winder TL, Michele DE, Moore SA, Campbell KP (2011) Myoglobinuria and muscle pain are common in patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2I. Neurology 76:194–195. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182061ad4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercuri E, Bönnemann CG, Muntoni F (2019) Muscular dystrophies. The Lancet 394:2025–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32910-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metzinger L, Blake DJ, Squier MV, Anderson LVB, Deconinck AE, Nawrotzki R, Hilton-Jones D, Davies KE (1997) Dystrobrevin deficiency at the sarcolemma of patients with muscular dystrophy. Human Molecular Genetics 6:1185–1191. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamori M, Takahashi MP (2011) The role of alpha-dystrobrevin in striated muscle. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 12:1660–1671. doi: 10.3390/ijms12031660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nallamilli BRR, Chakravorty S, Kesari A, Tanner A, Ankala A, Schneider T, da Silva C, Beadling R, Alexander JJ, Askree SH, Whitt Z, Bean L, Collins C, Khadilkar S, Gaitonde P, Dastur R, Wicklund M, Mozaffar T, Harms M, Rufibach L, Mittal P, Hegde M (2018) Genetic landscape and novel disease mechanisms from a large LGMD cohort of 4656 patients. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 5:1574–1587. doi: 10.1002/acn3.649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen K, Bassez G, Krahn M, Bernard R, Laforêt P, Labelle V, Urtizberea JA, Figarella-Branger D, Romero N, Attarian S, Leturcq F, Pouget J, Lévy N, Eymard B (2007) Phenotypic study in 40 patients with dysferlin gene mutations: High frequency of atypical phenotypes. Archives of Neurology 64:1176–1182. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panadés-de Oliveira L, Bermejo-Guerrero L, de Fuenmayor-Fernández de la Hoz CP, Cantero Montenegro D, Hernández Lain A, Martí P, Muelas N, Vilchez JJ, Domínguez-González C (2020) Persistent asymptomatic or mild symptomatic hyperCKemia due to mutations in ANO5: the mildest end of the anoctaminopathies spectrum. Journal of Neurology 267:2546–2555. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09872-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pena L, Kim K, Charrow J (2010) Episodic myoglobinuria in a primary gamma-sarcoglycanopathy. Neuromuscular Disorders 20:337–339. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pilgram GSK, Potikanond S, Baines RA, Fradkin LG, Noordermeer JN (2010) The roles of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex at the synapse. Molecular Neurobiology 41:1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinal-Fernandez I, Amici DR, Parks CA, Derfoul A, Casal-Dominguez M, Pak K, Yeker R, Plotz P, Milisenda JC, Grau-Junyent JM, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Paik JJ, Albayda J, Corse AM, Lloyd TE, Christopher-Stine L, Mammen AL (2019) Myositis Autoantigen Expression Correlates With Muscle Regeneration but Not Autoantibody Specificity. Arthritis and Rheumatology 71:1371–1376. doi: 10.1002/art.40883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Derfoul A, Pak K, Miller FW, Milisenda JC, Grau-Junyent JM, Selva-O’callaghan A, Carrion-Ribas C, Paik JJ, Albayda J, Christopher-Stine L, Lloyd TE, Corse AM, Mammen AL (2020) Machine learning algorithms reveal unique gene expression profiles in muscle biopsies from patients with different types of myositis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79:1234–1242. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Derfoul A, Pak K, Plotz P, Miller FW, Milisenda JC, Grau-Junyent JM, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Paik J, Albayda J, Christopher-Stine L, Lloyd TE, Corse AM, Mammen AL (2019) Identification of distinctive interferon gene signatures in different types of myositis. Neurology 93:e1193–e1204. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ponting CP, Blake DJ, Davies KE, Kendrick-Jones J, Winder SJ (1996) ZZ and TAZ: New putative zinc fingers in dystrophin and other proteins. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 21:11–13. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(06)80020-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quinlivan R, Jungbluth H (2012) Myopathic causes of exercise intolerance with rhabdomyolysis. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 54:886–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy HM, Cho KA, Lek M, Estrella E, Valkanas E, Jones MD, Mitsuhashi S, Darras BT, Amato AA, Lidov HG, Brownstein CA, Margulies DM, Yu TW, Salih MA, Kunkel LM, Macarthur DG, Kang PB (2017) The sensitivity of exome sequencing in identifying pathogenic mutations for LGMD in the United States. Journal of Human Genetics 62:243–252. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubegni A, Malandrini A, Dosi C, Astrea G, Baldacci J, Battisti C, Bertocci G, Donati MA, Dotti MT, Federico A, Giannini F, Grosso S, Guerrini R, Lenzi S, Maioli MA, Melani F, Mercuri E, Sacchini M, Salvatore S, Siciliano G, Tolomeo D, Tonin P, Volpi N, Santorelli FM, Cassandrini D (2019) Next-generation sequencing approach to hyperCKemia: A 2-year cohort study. Neurology: Genetics 5:e352. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scalco RS, Gardiner AR, Pitceathly RDS, Hilton-Jones D, Schapira AH, Turner C, Parton M, Desikan M, Barresi R, Marsh J, Manzur AY, Childs AM, Feng L, Murphy E, Lamont PJ, Ravenscroft G, Wallefeld W, Davis MR, Laing NG, Holton JL, Fialho D, Bushby K, Hanna MG, Phadke R, Jungbluth H, Houlden H, Quinlivan R (2016) CAV3 mutations causing exercise intolerance, myalgia and rhabdomyolysis: Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of caveolinopathies. Neuromuscular Disorders 26:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon MJ, Murchison C, Iliff JJ (2018) A transcriptome-based assessment of the astrocytic dystrophin-associated complex in the developing human brain. Journal of Neuroscience Research 96:180–193. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straub V, Murphy A, Udd B (2018) 229th ENMC international workshop: Limb girdle muscular dystrophies – Nomenclature and reformed classification Naarden, the Netherlands, 17–19 March 2017. Neuromuscular Disorders 28:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H (2010) Analysing biological pathways in genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics 11:843–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiel L, Baakman C, Gilissen D, Veltman JA, Vriend G, Gilissen C (2019) MetaDome: Pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants through aggregation of homologous human protein domains. Human Mutation 40:1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/humu.23798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zima J, Eaton A, Pál E, Till Á, Ito YA, Warman-Chardon J, Hartley T, Cagnone G, Melegh BI, Boycott KM, Melegh B, Hadzsiev K (2020) Intrafamilial variability of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, LGMD1D type. European Journal of Medical Genetics 63:103655. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1 (online resource). T1-weighted MRI sequences of shoulder girdle (a), pelvic girdle (b), thighs (c), and calves (d) of individual A.III.2 at 14 years of age revealed T1 signal hyperintensity suggestive of very mild focal fatty replacement in the gluteus maximii and tensor fascia latae.

Supplementary Figure S2 (online resource). Variants DTNA c.1585G>A; p.Glu529Lys and c.1567-1587del21; p.Gln523_Glu529del7 are located in a region mostly intolerant to genetic variation. The tolerance to variation analysed with Metadome is showed for (1) α-dystrobrevin, (2) coiled-coil domain, (3) the second helix, and (4) the location of the variants.

Supplementary Figure S3 (online resource). Western blots of α-dystrobrevin (antibody targeting C-terminus), dystrophin and sarcoglycans (α, γ, and δ) were performed on protein lysates from muscle biopsy samples representing three affected individuals and one control. α-dystrobrevin and dystrophin showed comparable band intensities in affected samples and the control. Sarcoglycan band intensities were reduced in all affected individuals compared to control.

Supplementary Figure S4 (online resource). Proliferation, migration, and differentiation/myoblast fusion assays were performed on C2C12 myoblasts that were transiently transfected with wild type DTNA (WT-DTNA) fused to GST, variant-DTNA (Del-DTNA) fused to GST, and empty vector containing GST as a control. The Del-DTNA construct contains the c.1567_1587 deletion. (a) Direct cell counts showed a decrease at 24 hours post-transfection in proliferation of cells transfected with Del-DTNA as compared to WT-DTNA. Cyquant assays showed corresponding decreases at 24 and 48 hours post-transfection in cells transfected with Del-DTNA compared to WT-DTNA. (b) Scratch-test assays of C2C12 migration showed no visible differences in cell migration at 24 and 48 hours post-transfection between cells transfected with WT-DTNA, Del-DTNA, and empty vector. (c) There were no visible differences in differentiation and myoblast fusion between C2C12 cells transfected with WT-DTNA and Del-DTNA, based on desmin and DAPI staining.

Supplementary Figure S5 (online resource). A high degree of conservation was found between DTNA and its orthologs across species. (a) Clustal O (1.2.4) multiple sequence alignment of human, mouse, zebrafish, fruit fly, and worm protein sequences. (b) Expasy prosite analysis of protein domains and functional sites showing the presence of the zinc finger (ZZ) domain in all analyzed species. The ZZ domain which binds two zinc ions was first identified in dystrophin homologs [39], and is required for dystrophin and utrophin to bind β-dystroglycan [18].

Supplementary Table S1 (online resource). List of antibodies used in studies for inmmunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence and western-blot.

Supplementary Table S2 (online resource). Pathogenic effect of DTNA genetic variants found in the individuals of this study. Allele frequency in the total population (gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database) and in the Spanish population (CSVS, Collaborative Spanish Variant Server). Genetic variant classification based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines, using VarSome (last accessed June 7, 2022). Variant effect predictors used were: FATHMM-MKL, Mutation taster, and DANN (with scores ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 is the most damaging), PROVEAN (with scores equal or below −2.5 being deleterious and above −2.5 being neutral), CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion) (with scores ≥ 20 indicating that the variant is predicted to be among the 1% of the most deleterious substitutions in the human genome). Abbreviations: NR, not reported; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Supplementary Table S3 (online resource). Summary of phenotypes observed in DTNA/α-dystrobrevin loss-of-function (LOF) mutants in different model organisms [6, 12-15, 19].

Data Availability Statement

Any data not published within the article will be shared by the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Any data not published within the article will be shared from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.