Abstract

We report that newly synthesized mRNA poly(A) tails are matured to precise lengths by the Pab1p-dependent poly(A) nuclease (PAN) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These results provide evidence for an initial phase of mRNA deadenylation that is required for poly(A) tail length control. In RNA 3′-end processing extracts lacking PAN, transcripts are polyadenylated to lengths exceeding 200 nucleotides. By contrast, in extracts containing PAN, transcripts were produced with the expected wild-type poly(A) tail lengths of 60 to 80 nucleotides. The role for PAN in poly(A) tail length control in vivo was confirmed by the finding that mRNAs are produced with longer poly(A) tails in PAN-deficient yeast strains. Interestingly, wild-type yeast strains were found to produce transcripts which varied in their maximal poly(A) tail length, and this message-specific length control was lost in PAN-deficient strains. Our data support a model whereby mRNAs are polyadenylated by the 3′-end processing machinery with a long tail, possibly of default length, and then in a PAN-dependent manner, the poly(A) tails are rapidly matured to a message-specific length. The ability to control the length of the poly(A) tail for newly expressed mRNAs has the potential to be an important posttranscriptional regulatory step in gene expression.

The majority of eukaryotic mRNAs have at their 3′ end a poly(A) tail. The mRNA poly(A) tail is synthesized in the nucleus in a reaction that is thought to be tightly coupled to RNA polymerase II transcription (18, 40, 50). Addition of the poly(A) tail requires endonucleolytic cleavage of the precursor RNA (pre-RNA), creating a new RNA 3′ end which serves as a substrate for the poly(A) polymerase (16, 30, 68). The length of the poly(A) tail is subject to cellular control throughout the life span of the mRNA (5). For instance, an mRNA’s poly(A) tail is added to a species-specific length in the nucleus, shortened at an mRNA-specific rate in the cytoplasm, and in certain instances, lengthened again by cytoplasmic readenylation. The regulated control of mRNA poly(A) tail length likely serves two major purposes: to regulate mRNA translation (27, 55) and mRNA turnover (6, 28, 64).

The importance of an mRNA’s poly(A) tail length for translational control is elegantly highlighted during oogenesis and early embryogenesis, when regulated changes in poly(A) tail length often correlate with changes in gene expression (17, 71, 72). In these cells, deadenylation of an mRNA usually results in a reduced efficiency of translation (for example, see references 22, 65 and 74), whereas specific cytoplasmic readenylation stimulates the recruitment of an mRNA to the translation machinery (for example, see references 56 and 59). Furthermore, studies by Sheets et al. (58, 59) suggest that differences in poly(A) tail length may contribute to quantitative differences in translational stimulation, with longer poly(A) tails having a stronger stimulatory effect.

The poly(A) tail is also an important modulator of mRNA stability. The rate of poly(A) tail shortening is tightly regulated and message specific and can range over 10-fold in magnitude. Poly(A) tail-shortening rates can be determined by cis-acting RNA sequences often found within the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the mRNA. Rates of mRNA deadenylation usually correlate with rates of degradation, and mutations or RNA sequences that alter the rate of poly(A) tail shortening alter the rate of mRNA decay correspondingly (for instance, see references 48 and 60). A deadenylation-dependent pathway of mRNA turnover has been proposed for both stable and unstable mRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (20, 46, 47). This pathway in yeast is modeled to require poly(A) tail shortening to 5 to 15 nucleotides and then decapping of the mRNA by the Dcp1p enzyme (7, 35). Upon removal of these terminal structures, mRNAs are rapidly destroyed in yeast by the 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1p (25, 46, 47) and the 3′-5′ exosome complex (26, 43). Thus, shortening of the mRNA poly(A) tail can result in both a decrease in translation and stimulation of mRNA degradation.

The most well-characterized protein associated with the mRNA poly(A) tail is the highly conserved poly(A)-binding protein Pab1p. Yeast Pab1p, encoded by the essential PAB1 gene, is necessary to mediate many aspects of poly(A) tail function. The Pab1p-poly(A) complex has been shown to synergistically increase the efficiency of 40S ribosomal subunit recruitment during translation initiation (33, 61–63, 70). Pab1p also appears to be important for the coupling of deadenylation and decapping, and it is thought that shortening of the poly(A) tail to lengths incapable of binding Pab1p is necessary for subsequent steps in the deadenylation-dependent pathway of mRNA turnover (14). However, the timing and interrelationship between deadenylation and decapping are not fully understood, since rates of mRNA decay are not dramatically altered in Pab1p yeast mutants that exhibit impaired deadenylation rates (44). More recently, Pab1p has been shown to function in the mRNA polyadenylation reaction (see below). Pab1p cofractionates with CFI (32, 42), one of the four purified yeast fractions necessary for accurate RNA 3′-end processing in vitro, and has been shown to physically interact with Rna15p (1), an essential subunit of CFI required for both cleavage and polyadenylation (41).

The RNA cleavage and polyadenylation reactions for both mammalian and yeast cells can be reconstituted in vitro with purified fractions. Many of the components required for RNA 3′-end processing have now been identified and appear to be conserved between yeast and mammals (31, 39). An inherent property of the polyadenylation reaction, hereafter referred to as poly(A) tail length control, is that the mRNA poly(A) tail is synthesized to a homogenous and defined length that is organism specific, ranging from ∼55 to 90 nucleotides for yeast mRNAs and from ∼150 to 250 nucleotides for mammalian mRNAs. This precise poly(A) length for newly processed mRNAs can be recapitulated in crude extracts and/or with purified proteins in vitro. Length control does not appear to be determined by the poly(A) polymerase itself but seems to require other factors that can either influence the processivity of this enzyme or postsynthetically process the poly(A) tail to the proper length. One factor that is thought to be required for mammalian poly(A) tail length control is the nuclear poly(A)-binding protein PABII (66, 69). In a purified system, PABII promotes processive poly(A) tail addition to approximately 250 nucleotides (67). For S. cerevisiae, the Pab1 protein appears to be required for proper poly(A) tail length control, as evidenced by the increase in length of the mRNA poly(A) tails produced in Pab1p-deficient 3′-end processing extracts (1, 32, 42) and in pab1 mutant yeast strains (53).

Once synthesized, the mRNA poly(A) tail is shortened by cellular deadenylases. Several poly(A) nucleases have been purified and characterized biochemically: a poly(A) nuclease purified from HeLa cell nuclear extract (3, 4), the DAN poly(A) nuclease purified from calf thymus tissue (34), and the poly(A) nuclease deadenylase, discussed in this study, which was purified from S. cerevisiae (10). All three deadenylases exonucleolytically degrade poly(A), releasing 5′-AMP as a product. These deadenylases require a 3′-OH group and degrade poly(A) by a Mg2+-dependent mechanism, likely analogous to the 3′-5′ exonucleolytic activity of DNA polymerases (8, 29). Although the mechanism for RNase digestion may be similar, the effect of Pab1p on the activity of each enzyme appears to be unique. The HeLa deadenylase is inhibited by Pab1p, as are several other poly(A) tail-shortening activities that have been detected (9, 73). The DAN RNase activity can be both stimulated and inhibited by Pab1p, depending on the in vitro conditions used (34). The yeast PAN RNase physically interacts with Pab1p (10), and this deadenylase will efficiently degrade only RNA that is bound by Pab1p (19, 37).

PAN is composed of at least two subunits, Pan2p and Pan3p, and is the first deadenylase for which the genes encoding the enzymatic activity have been identified (10, 12). Pan2p is presumed to be the catalytic subunit of the complex, since it is a member of the RNase T family of 3′-5′ exoribonucleases (45). Yeast that are deficient for either of the nonessential PAN2 and/or PAN3 genes contain mRNAs with aberrantly long poly(A) tails, suggesting an important role for PAN in mRNA metabolism. In this study, we further investigate this poly(A) tail metabolism defect. Most deadenylase activities have been characterized for their ability to shorten mRNA poly(A) tails to an oligo(A) length. We find that the PAN deadenylase matures newly synthesized poly(A) tails to defined poly(A) tail lengths of 50 to 90 nucleotides and that this initial poly(A) tail-shortening phase is necessary for message-specific poly(A) tail length control in S. cerevisiae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth conditions.

Yeast strains used in this study are listed on Table 1. The parent strain for all mutants is a W303 derivative, YAS306 (MATa ade2-1 his3-11 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 can1-100). The yeast strains harboring the rpb1-1 temperature-sensitive mutation in RNA polymerase II (51) were backcrossed at least twice into the YAS306 strain background. Standard media, growth conditions, and techniques for handling yeast were used (23). Strains were grown in rich medium (YP) or minimal medium (YM) supplemented with nutrients required for auxotrophic deficiencies and with either 2% glucose, 2% galactose, or 2% raffinose and 2% sucrose, pH 6.5.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| YAS306a | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 can1-100 |

| YAS1254 | MATa pab1::HIS3 pPAB1 TRP1 CEN (pAS82 [54]) |

| YAS1255 | MATa pab1::HIS3 ppab1-55 TRP1 CEN (pAS401 [54]) |

| YAS1942 | MATa pan2::LEU2 (10) |

| YAS1943 | MATa pan3::HIS3 (12) |

| YAS2283 | MATa pan2::LEU2 pan3::HIS3 |

| YAS2284 | MATα rpb1-1b pGAL1 MFA2pG URA3 CEN (pRP485 [46]) |

| YAS2285 | MATα rpb1-1 pan2::LEU2 pan3::HIS3 pGAL1 MFA2pG URA3 CEN (pRP485) |

| YAS2286 | MATα rpb1-1 pGAL1 B55TPGK1pG URA3 CEN (pRL602 [47]) |

| YAS2287 | MATα rpb1-1 pan2::LEU2 pan3::HIS3 pGAL1 B55TPGK1pG URA3 CEN (pRP602) |

| YAS2288 | MATα rpb1-1 pGAL1 RPL46 URA3 CEN (pAS582) |

| YAS2289 | MATα rpb1-1 pan2::LEU2 pan3::HIS3 pGAL1 RPL46 URA3 CEN (pAS582) |

Parental yeast strain.

RNA polymerase II temperature-sensitive mutation (51).

DNA manipulations.

To construct the GAL1:RPL46 vector, a fragment containing the entire open reading frame of RPL46 and 187 nucleotides 3′ of the stop codon (nucleotides 1 to 1461, including intron sequences) was amplified by PCR with 10 ng of yeast genomic DNA, 0.5 μM OAS322 (5′ GCTCTAGACATGGCTGTATGTTAGAAAGATATT) and OAS324 (5′ TTCCCACACGTGCTTATGGG), and 2.5 U of Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) in a 100-μl reaction mixture. The PCR product was gel purified, digested with XbaI and AciI (nucleotide +1345), and ligated into the XbaI-ClaI-digested pAS516 vector (pGAL1URA3CEN [49]), creating pAS582, a galactose-inducible RPL46 gene with GAL1 5′ leader sequences.

Protein extract preparation and immunological techniques.

RNA 3′-end processing extracts were prepared from ∼2 liters of yeast grown in YP supplemented with 2% glucose (YPD) to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 1.0). Yeast cells were harvested, washed once with sterile water, and resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 2 mM magnesium acetate (MgOAc), 50 mM potassium acetate (KOAc), 5% glycerol, 14.4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin) (0.5 volume/g of cell). The yeast slurry was dribbled directly into liquid nitrogen to form small pellets which were then ground into a fine powder with a mortar and pestle (on dry ice), with liquid nitrogen being added frequently. The desired amount of yeast powder (typically 4 g) was thawed rapidly in a 37°C water bath, placed immediately on ice, and diluted with an equal amount (in milliliters per gram) of G-50 buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.4], 50 mM KOAc, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 20% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin). Cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 30,000 × g (Beckman 60Ti rotor, 18,000 rpm) for 30 min at 4°C. The S-100 extract was prepared by centrifugation of the supernatant at 100,000 × g (60Ti rotor, 37,000 rpm) for 60 min at 4°C and typically yielded a protein concentration of ∼5 mg/ml. Ammonium sulfate was added to 40% saturation (0.226 g/ml of starting solution [21]) at 4°C, and the precipitated proteins were pelleted in a Sorvall SS34 rotor at 15,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of G-50 buffer per g of starting material (typically 400 μl) and dialyzed twice against 1 liter of G-50 buffer for 2 to 3 h each. The dialysate was microcentrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The protein concentration of extracts typically ranged from 4 to 6 mg/ml, which corresponded to approximately 5% of the protein being precipitated. Tight coupling of cleavage with the subsequent polyadenylation step in vitro was found to be dependent on the method of extract preparation (data not shown). When extracts were prepared by glass bead lysis, the 5′-cleaved unadenylated RNA product accumulated, whereas with liquid nitrogen-derived extracts, very tight coupling between cleavage and polyadenylation was observed.

Immunoneutralization of Pab1p and addition of exogenous Pab1p to the 3′-end processing extracts was performed by the method of Minvielle-Sebastia et al. (42). Recombinant Pab1p was purified as described by Sachs et al. (54). The purification of PAN and a silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel of the poly(U)-Sepharose eluate is presented in Boeck et al. (10). For the PAN add back experiments, 0.25 μl of the poly(U)-Sepharose eluate was preincubated with 10 μg of extract for 10 to 15 min on ice.

Immunoblot analysis was carried out by standard procedures (57). Proteins were resolved on 0.75-mm-thick SDS–8% polyacrylamide minigels, electroblotted onto nitrocellulose (Amersham) in Tris-glycine transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine, 20% methanol, 0.05% SDS). The blot was blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and incubated for at least 1 h at room temperature with the primary antibody diluted in TBS-T with 5% milk. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Pan3p (12) and anti-Rna15p (41) antibodies were used at dilutions of 1/5,000 and 1/1,000, respectively. Mouse monoclonal anti-Pab1p (2) and anti-PGK1 (Molecular Probes) antibodies were used at dilutions of 1/5,000 and 1/50,000, respectively. After blots were washed three times (10 min each) with TBS-T, they were incubated for a minimum of 30 min at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Amersham) diluted 1:5,000 in TBS-T, washed again as described above, and then developed by the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection system (Amersham).

PAN assay.

The homogeneously labeled [α-32P]poly(A)300+ substrate used for the PAN activity assay was prepared as described previously (12). Briefly, a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1× polymerase buffer, 0.5 μM oligo(A)12 (Pharmacia), 167 μM ATP, 50 μCi of [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol), and 500 U of recombinant yeast poly(A) polymerase (United States Biochemical) were incubated at 30°C for 60 min. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by spin column (S-200) chromatography (Pharmacia).

PAN activity was assayed by diluting (on ice) the protein fraction of interest and 500 ng of recombinant Pab1p or pab1-55p (when specified) in a final volume of 10 μl with dilution buffer (5 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 2 mM MgCl2, 14.4 mM β-mercaptoethanol [BME]). Reaction mixtures were further diluted to 200 μl with dilution buffer containing 0.01 mg of tRNA per ml and ∼50,000 cpm of homogeneously labeled [α-32P]poly(A)300+ (final concentration). After incubating for 30 min at 30°C, reactions were quenched with 200 μl of 20% trichloroacetic acid, precipitated on ice for 10 min, and microcentrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. Two hundred microliters of the supernatant, containing the soluble radionucleotide, was added to 200 μl of unbuffered 1 M Tris base and 4 ml of Aquasol (New England Nuclear), and the resulting solution was subjected to scintillation counting.

In vitro 3′-end processing assay.

Capped and uniformly labeled CYC1 pre-RNA was prepared from the EcoRI-linearized pG4-CYC1 vector (41) by in vitro transcription with bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. The precleaved CYC1 RNA was prepared from the NdeI-linearized pG4-CYC1-pre vector in an identical manner (52a). A 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1× T7 polymerase buffer, 1.2 μg of DNA, 7.5 mM ATP and CTP, 0.75 mM GTP, 0.075 mM UTP, 3 mM GppG (cap analog) (New England Biolabs), 50 μCi of [α-32P]UTP, and 2 μl of T7 polymerase (Ambion) was incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The transcript was purified on a gel containing 6% polyacrylamide, 8.3 M urea, 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) and resuspended in 100 μl of RNase-free double-distilled water, yielding approximately 100 fmol of RNA/μl.

Cleavage and polyadenylation assays were carried out in a 25-μl reaction mixture volume containing ∼10 μg of extract protein (prepared as described above) and 20 fmol of RNA in a solution containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 75 mM KOAc, 1.5 mM MgOAc, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 2% polyethylene glycol 8000, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 1 μg of creatine phosphokinase, 1.8 mM ATP, and 0.125 μl of RNasin (Promega) (41). To inhibit polyadenylation, reaction mixtures were treated equivalently except that 1.5 mM EDTA was substituted for MgOAc and 1.8 mM CTP was substituted for ATP. After incubation for a specified amount of time, usually 60 min at 30°C, reactions were stopped with 75 μl of proteinase K stop solution (final concentration, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 12.5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.2 mg of proteinase K per ml, 0.05 mg of glycogen per ml) and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. RNA was precipitated with 250 μl of 100% ethanol at −80°C for at least 30 min, washed with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in 40 μl of formamide loading dye (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA). Reaction products (10 μl) were resolved on a gel containing 6% acrylamide, 8.3 M urea, and 1× TBE and visualized by autoradiography.

Northern blot analysis.

For steady-state mRNA poly(A) tail length analysis, ∼15 OD600 units of yeast culture, grown to early log phase (0.3 to 0.6 OD600) at 30°C, was harvested, washed once with water, and extracted by a modified hot-phenol method as described previously (12). Yeast strains were grown in rich medium (YPD) for the endogenous RPL46 and PGK1 mRNA experiments, whereas strains were grown in minimal medium YM supplemented with 2% glucose (YMD) for the detection of endogenous MFA2 mRNA. For reasons not known at this time, higher expression of endogenous MFA2 mRNA was observed when yeast cells were grown in minimal medium, but the composition of the medium did not affect the maximal mRNA poly(A) tail length. Transcriptional pulse experiments were carried out by procedures similar to those described previously (20), except that the amount of time for which yeast cells were grown in raffinose-containing medium was minimized because pan mutant strains tended to aggregate. Strains were patched onto YMD plates lacking uracil, and freshly grown cells were inoculated into 25 ml of YM medium containing 2% raffinose and 2% sucrose lacking uracil (pH 6.5). The following day, yeast strains were diluted in 300 ml of raffinose-containing medium to an OD600 of 0.07 to 0.1, and when the culture reached an OD600 of 0.3, a 50-ml zero time point was taken. The rest of the 250-ml culture was then harvested and resuspended in 7 ml of YM medium containing 4% galactose lacking uracil, and 1.5-ml time points were taken at 4, 8, and 12 min after the shift to the different medium.

RNase H cleavage of RNA was carried out in a 10-μl reaction mixture volume containing ∼10 μg of total yeast RNA, and 300 ng of oligo(dT) or 100 ng of message-specific oligonucleotide with 0.25 U of RNase H (Gibco BRL) in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 30 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml (20). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and 10 μl of formamide loading dye was added to stop the reaction.

RNA samples (10 to 20 μg) were resolved on 0.75-mm-thick gels containing 5 or 6% polyacrylamide, 8.3 M urea, and 0.5× TBE and run for 3,000 to 4000 V · h. RNA was electroblotted to Zetaprobe membrane (Bio-Rad) in 0.5× TBE at 50 V for 3 h and fixed to the membrane by cross-linking with the UV Stratalinker 1800 apparatus (Stratagene). Zetaprobe membranes were hybridized in a solution containing 7% SDS, 250 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.2), and 2 mM EDTA as described by the manufacturer. Oligonucleotide (50 ng) was 32P labeled at the 3′ end with terminal deoxytransferase (Gibco BRL), and hybridization was performed at 50°C. DNA template (100 ng), derived either from a PCR reaction mixture or from a plasmid, were 32P labeled by using random primers and the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase and used for hybridization at 65°C. Membranes were washed at 50°C for oligonucleotide probes and at 65°C for hexamer-labeled probes as recommended by the manufacturer. RNA blots were visualized by autoradiography and/or PhosphorImager analysis. To quantify maximal mRNA poly(A) tail lengths, the ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics) was used to generate line graphs of pixel intensity versus distance. The longest tail was measured as the distance at which the Northern blot signal was three- to fivefold over background. The distance was converted to nucleotide length by standardization to pBR322 and MspI DNA markers, and the tail length was determined by direct comparison to the size of the unadenylated RNA (A0).

RESULTS

Coprecipitation of PAN with the mRNA 3′-end processing activity.

Mutations in both Pab1p and the Pab1p-dependent PAN result in abnormally long mRNA poly(A) tails in vivo (10, 12, 53). We therefore hypothesized that the Pab1p requirement for poly(A) tail length control in 3′-end processing extracts (1, 42) may be due to the necessity of Pab1p in the activation of PAN. If true, this would represent a previously uncharacterized phase of mRNA poly(A) tail shortening that is distinct from the more thoroughly characterized cytoplasmic deadenylation event that precedes mRNA turnover.

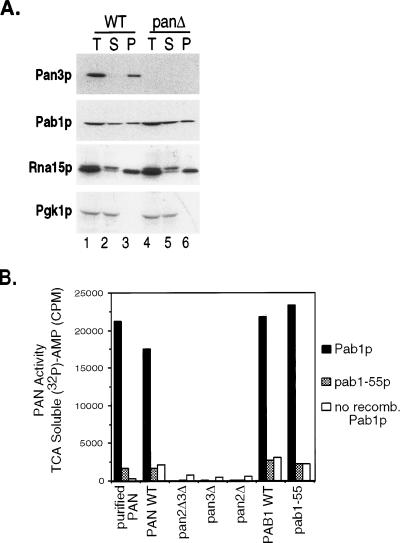

To investigate the possibility that PAN plays a role in RNA 3′-end processing, we tested for the presence of PAN in partially purified cleavage and polyadenylation extracts. Yeast S-100 extracts can be enriched for the 3′-end processing machinery by ammonium sulfate fractionation (0 to 40% saturation) (13). Equivalent percentages of the starting S-100 extract (total [T]) and the ammonium sulfate supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and the fractionation properties of several proteins were analyzed by Western blot analysis. Pan3p, the 76-kDa subunit of PAN, was used as a marker to study the fractionation properties of the PAN enzyme. Pan2p could not be detected by Western blot analysis, since the Pan2p antibodies were not of high enough titer to recognize Pan2p in crude extracts. As shown in Fig. 1A (lanes 1 to 3), the majority of Pan3p cofractionated with the ammonium sulfate precipitant (P), suggesting that the PAN enzyme is present in fractions enriched for the cleavage and polyadenylation machinery.

FIG. 1.

The PAN RNase is present in RNA 3′-end processing extracts. (A) Wild-type (WT) and Pan3p-deficient (panΔ) yeast S-100 extracts were ammonium sulfate precipitated as described in Materials and Methods. The total starting extracts (T), soluble fractions (S), and precipitatant fractions (P) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the indicated proteins were detected by Western blot analysis. Wild-type and Pan3p-deficient cell extracts were prepared from strains YAS306 and YAS1943, respectively. Equivalent percentages of the fractions were loaded onto the lanes. (B) Detection of PAN activity in 3′-end processing extracts prepared from pan and pab1 mutant yeast strains. One microgram of total protein was incubated with radiolabeled poly(A) and either recombinant Pab1p (black bars), pab1-55p (grey stippled bars), or no additional Pab1p (white bars) as described in Materials and Methods. Nuclease activity was measured by quantifying the release of trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-soluble [32P]AMP (y axis). The purified PAN enzyme serves as a positive control for the Pab1p-stimulated RNase activity. The yeast strains used to prepare the 3′-end processing extracts were (from left to right) YAS306, YAS2283, YAS1943, YAS1942, YAS1254, and YAS1255. Abbreviations: recomb., recombinant; WT, wild type.

The ammonium sulfate fractionation properties of several other proteins were also analyzed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 to 3). In contrast to Pan3p, only about half of the Pab1 protein fractionated with the ammonium sulfate precipitant. For Rna15p, a required component of the 3′-end processing machinery (41), a doublet is detected in the S-100 extract. The lower Rna15p band was almost exclusively found in the ammonium sulfate precipitants, whereas the upper band, possibly a modified form of Rna15p or a cross-reacting species, remained soluble. Pgk1p remained soluble and was not precipitated under these fractionation conditions. We note that the absence of Pan3p in the extracts did not alter the fractionation profiles of any of the other proteins examined, including Pab1p (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 to 6).

To confirm that the PAN enzyme was functional in the 3′-end processing extracts, we assayed for Pab1p-dependent PAN activity. The activation of PAN by Pab1p is allele specific, and PAN will not efficiently degrade poly(A) that is bound by pab1-55p (Fig. 1B, purified PAN), a 137-amino-acid C-terminal deletion mutant (54). A Pab1 protein containing a deletion of the C terminus is, however, equivalent to the wild-type Pab1 protein for all other activities tested. This allele has high-affinity RNA-binding activity and is capable of maximally stimulating translation (33, 54).

Various pan and pab1 mutant extracts were fractionated with ammonium sulfate and analyzed for PAN RNase activity. The extracts do contain endogenous Pab1p; however, when the extract was diluted, the amount of Pab1p in the extracts (5 ng) did not efficiently activate PAN. This observation was exploited to demonstrate that the purified PAN enzyme and the RNase activity in the 3′-end processing extracts exhibited the same Pab1p allele specificity. Diluted 3′-end processing extracts were programmed with either recombinant Pab1p, pab1-55p, or no excess protein and then incubated with homogeneously radiolabeled poly(A). PAN activity can be monitored by assaying for released AMP (trichloroacetic acid soluble). Robust PAN activity was detected in wild-type extracts programmed with recombinant Pab1p (Fig. 1B, PAN WT and PAB1 WT). This activity was dependent on both Pan2p and Pan3p, since extracts lacking either protein did not exhibit significant RNase activity upon addition of Pab1p (Fig. 1B, pan2Δ3Δ, pan3Δ, and pan2Δ). Efficient degradation of the poly(A) substrate occurred only in the presence of wild-type Pab1p, with background levels of RNA degradation detected when either recombinant pab1-55p or no Pab1 protein was added. PAN activity is still detected in the pab1-55 extract (Fig. 1B, pab1-55), indicating that this mutant Pab1p does not affect the cofractionation of PAN with the ammonium sulfate precipitants. Together with the Western blots described above, the PAN activity assays confirm that PAN is present and active in the 3′-end processing extracts. Thus, any explanation for the requirement of Pab1p in 3′-end processing must also consider the ability of Pab1p to activate PAN.

PAN is required for proper poly(A) tail length control in vitro.

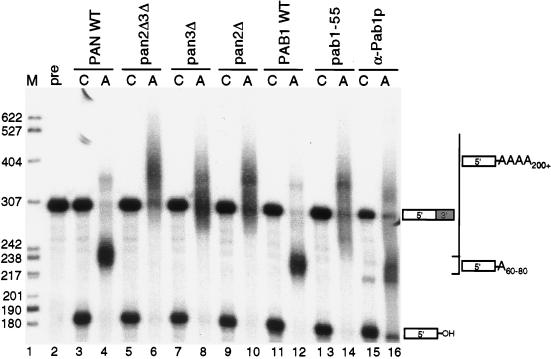

To investigate a possible role for PAN in 3′-end processing, we monitored cleavage and polyadenylation efficiencies in the extracts described in the legend to Fig. 1B. Extracts were programmed with in vitro-transcribed CYC1 pre-RNA (Fig. 2, lane 2), and polyadenylation reactions were performed as previously described (41) (see Materials and Methods). Wild-type extracts were found to polyadenylate the CYC1 substrate to the previously reported lengths of 60 to 80 nucleotides (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 12). In comparison, extracts deficient for the Pan2p and Pan3p subunits polyadenylated the CYC1 RNA to the anomalously long and heterogeneous lengths of 90 to ≥200 nucleotides (Fig. 2, compare lanes 4 and 12 with lanes 6, 8, and 10).

FIG. 2.

pan and pab1 mutant yeast extracts polyadenylate RNA substrates to aberrantly long lengths in vitro. The six 3′-end processing extracts (10 μg of total protein) described in the legend to Fig. 1B and a wild-type extract (YAS306) immunoneutralized for Pab1p (lanes 15 and 16) were programmed with CYC1 pre-RNA as described in Materials and Methods. Reaction products were visualized on a 6% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Products of the cleavage reaction only (C) or of cleavage and polyadenylation of the CYC1 pre-RNA (A) are shown. Lane 1; DNA markers (M); lane 2, input CYC1 pre-RNA (precursor [pre]). The migration positions of the 5′-upstream cleavage product and the polyadenylated products are indicated to the right, and the sizes (in nucleotides) of the DNA markers are indicated to the left. WT, wild type; α-Pab1p, anti-Pab1p.

The longer poly(A) tails synthesized in the pan mutants are reminiscent of the loss of poly(A) tail length control previously reported for pab1 mutants (1, 32, 42). To compare the pab1 and pan mutant phenotypes, a wild-type extract in which Pab1p had been immunoneutralized and an extract in which PAN was not activated (pab1-55p) were analyzed for in vitro 3′-end processing. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, both of these pab1 mutant extracts exhibited a loss of poly(A) tail length control in a manner similar to that observed in the pan mutant extracts (lanes 14 and 16 versus lanes 6, 8, and 10). Equivalent results for all extracts were also obtained with the precleaved CYC1 substrate (data not shown). The observation that the PAN-deficient, pab1-55p, and anti-Pab1p immunoneutralized extracts all exhibit a similar defect in poly(A) tail length control suggests that one important role of Pab1p in polyadenylation is to activate the PAN RNase.

The two PAN subunits, Pan2p and Pan3p, are both required for RNase activity, and deletions in either subunit result in an equivalent long-tailed mRNA phenotype in vivo (10, 12). Similarly, we find that a deletion of either Pan2p, Pan3p, or both results in a similar defect in poly(A) tail length control in vitro (Fig. 2, lanes 6, 8, and 10). The data in Fig. 2 may suggest that the in vitro phenotype for the pan2Δ pan3Δ mutant is slightly more severe than that for either single pan mutant. This possibility is being further investigated, but at the current time, it seems more likely that the slight differences are due to variations in the extracts.

The cleavage efficiencies of the extracts were also examined by using conditions that inhibited polyadenylation (see Materials and Methods). Under such conditions, the efficiency of the cleavage reaction was reduced, with only about half of the pre-CYC1 substrate being cleaved in wild-type extracts (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 11). Pab1p has been previously shown to have no effect on the cleavage step of RNA 3′-end processing in extracts (1, 32, 42), and as expected, we did not detect a decrease in cleavage efficiency with either the anti-Pab1p immunoneutralized or pab1-55p extracts (Fig. 2, lanes 13 and 15). Likewise, the cleavage efficiencies were also unaffected in the pan mutant extracts (Fig. 2, lanes 5, 7, and 9), demonstrating that PAN does not play a role in the pre-RNA cleavage reaction.

To further demonstrate a specific requirement for PAN in poly(A) tail length control, the PAN-deficient extracts were complemented with the purified PAN enzyme. The penultimate step in the PAN purification scheme is poly(U)-Sepharose chromatography (10). Purified PAN in the poly(U) eluate was used as the source of PAN in all assays presented. This poly(U) eluate is active (Fig. 1B, purified PAN), contains the Pan2p and Pan3p subunits, and is highly pure, as only one other major unidentified protein of ∼110 kDa is detected by silver staining (10, 12). An amount of purified enzyme comparable to the level of PAN activity and Pan3p in the wild-type extract was used for these complementation experiments. Addition of excess PAN to wild-type extracts resulted in a slight trimming of the poly(A) tail from 60 to 80 nucleotides to 50 to 70 nucleotides (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 4 and 5 and lanes 12 and 13). The excess enzyme did not appear to efficiently deadenylate the RNA to a length shorter than ∼50 adenylate residues. Addition of purified PAN to the pan mutant extracts, prior to the start of the reaction, restored poly(A) length control (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 6 and 7, lanes 8 and 9, and lanes 10 and 11). Notably, the longer, heterogeneous polyadenylated products formed in the pan mutants did not accumulate when the purified enzyme was present. A time course of 3′-end processing further demonstrated that the purified PAN enzyme was able to fully complement the pan mutant extracts (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 3 to 7, lanes 8 to 12, and lanes 13 to 17).

FIG. 3.

Deadenylation by the PAN RNase is required for proper poly(A) tail length control in vitro. (A) Cleavage and polyadenylation reactions were performed and visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 2. RNA 3′-end processing extracts described in the legend to Fig. 1B were incubated with (+) or without (−) purified PAN. Lane 1, DNA markers (M); lane 2, input CYC1 pre-RNA (precursor [pre]); lane 3, product of cleavage reaction only. The migration positions of the 5′-upstream cleavage product and the polyadenylated products are indicated to the right, and the sizes (in nucleotides) of the DNA markers are indicated to the left. WT, wild type. (B) Time course of CYC1 3′-end processing was carried out in either wild-type extracts of strain YAS306 (lanes 3 to 7), pan3Δ mutant extracts of YAS1943 (lanes 8 to 12), or pan3Δ mutant extracts, containing exogenously added purified PAN (lanes 13 to 21). The purified enzyme was either added at the beginning of the reaction (lanes 13 to 17) or 60 min post-CYC1 cleavage and polyadenylation (lanes 18 to 21). Cleavage and polyadenylation reactions were carried out and visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Lane 1, DNA markers (M); lane 2, input CYC1 pre-RNA (precursor [pre]). The migration positions of the 5′-upstream cleavage product and the polyadenylated products are indicated to the right, and the sizes (in nucleotides) of the DNA markers are indicated to the left.

The inability of purified PAN to restore proper poly(A) tail length control in the pab1-55p extract suggested that poly(A) tail shortening, not inhibition of the yeast poly(A) polymerase (Pap1p), was responsible for determining poly(A) tail lengths in vitro (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 14 and 15). The PAN enzyme was also unable to rescue anti-Pab1p immunoneutralized extracts (data not shown). Thus, purified PAN could complement the PAN-deficient length control defect only when an allele of Pab1p capable of stimulating PAN’s RNase activity was present in the extract. To address more specifically whether poly(A) tail length control requires deadenylation, long poly(A) tails were first formed in the pan mutant extract and then purified PAN was added to the reaction mixture. A time course following PAN addition to the extract demonstrates that PAN shortens long poly(A) substrates to 60 to 80 adenylate residues, a length which is normally observed in the wild-type extract (Fig. 3B, lanes 18 to 21). Moreover, deadenylation by PAN was rapid, occurring within 10 min after addition of the enzyme (Fig. 3B, lanes 18 and 19). After shortening the long tails to 60 to 80 residues, the poly(A) tails appeared to be only slowly trimmed over the next 20 min of the reaction. We conclude from these experiments that deadenylation by PAN is required for poly(A) tail length control in vitro and that under the conditions used for the 3′-end processing reaction, PAN does not efficiently deadenylate mRNA poly(A) tails past a length of approximately 50 nucleotides.

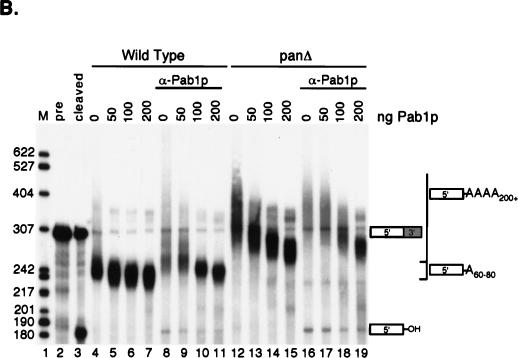

Excess Pab1p reduces the severity of the polyadenylation defect in PAN-deficient extracts.

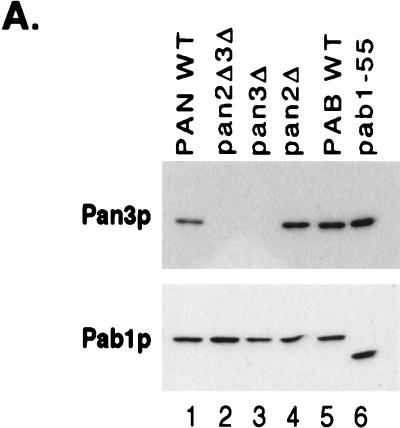

Other investigators have suggested that Pab1p’s role in yeast poly(A) tail length control is due to inhibition of processive polyadenylation (1, 42). It was therefore important to determine if the extracts lacking either Pan2p or Pan3p also lacked Pab1p. Equivalent amounts of the various extracts used in this study were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the amount of Pab1p in each fraction was determined by Western blot analysis. As observed both in Fig. 1A and 4A, the Pab1 protein levels were not dramatically altered when subunits of the PAN enzyme were absent. Thus, we conclude that wild-type levels of endogenous Pab1p in the absence of PAN are not sufficient for proper poly(A) tail length control in vitro.

FIG. 4.

Excess Pab1p reduces the severity of the pan mutant polyadenylation phenotype. (A) Western blot analysis of Pan3p and Pab1p in the previously described 3′-end processing extracts (Fig. 2). A 1.5-μg amount of total protein was loaded in each lane. WT, wild type. (B) Excess Pab1p inhibits polyadenylation in vitro. Recombinant Pab1p was added to the wild-type (YAS306 [lanes 4 to 7]) or pan2Δ pan3Δ mutant (YAS2283 [lanes 12 to 15]) extracts. Alternatively, the endogenous Pab1p was first immunoneutralized in wild-type (lanes 8 to 11) or pan mutant (lanes 16 to 19) extracts with monoclonal anti-Pab1p (α-Pab1p) antibodies (see Materials and Methods). The amount of recombinant Pab1p (in nanograms) added to each reaction mixture is indicated above the blot. Cleavage and polyadenylation reactions were performed and visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 2, except that reaction mixtures were incubated for 90 min. Lane 1, markers (M); lane 2, input CYC1 pre-RNA (precursor [pre]); lane 3, product of cleavage reaction only. The migration positions of the 5′-upstream cleavage product and the polyadenylated products are indicated to the right, and the sizes (in nucleotides) of the DNA markers are indicated to the left.

We also observed that addition of excess recombinant Pab1p could reduce the severity of the poly(A) tail length defect observed in pan mutants. Pab1p was estimated to comprise approximately 0.5% of the total protein in the extract (data not shown). Addition of up to fourfold excess Pab1p (200 ng) did not have a dramatic affect on the 3′-end processing of wild-type extracts (Fig. 4B, lanes 4 to 7). This amount of recombinant Pab1p was determined to be in excess of that needed for Pab1p function in the extract, since both 100 and 200 ng of Pab1p were able to fully rescue the deficiency of an anti-Pab1p immunoneutralized extract (Fig. 4B, lanes 8 to 11). When equivalent amounts of excess recombinant Pab1p were added to the pan mutant extracts, the length of the CYC1 polyadenylated product did decrease, but not to wild-type poly(A) tail lengths (Fig. 4B, lanes 12 to 15 and 16 to 19). Thus, the severity of the length control defect in PAN-deficient extracts appears to be sensitive to the level of Pab1p. Although the amount of Pab1p added in this assay is in excess of the physiological concentration of Pab1p, Fig. 4 suggests that Pab1p could be playing an additional role in poly(A) tail length control, in which it limits the processive polyadenylation length.

Steady-state mRNA poly(A) tails are longer in PAN-deficient yeast strains.

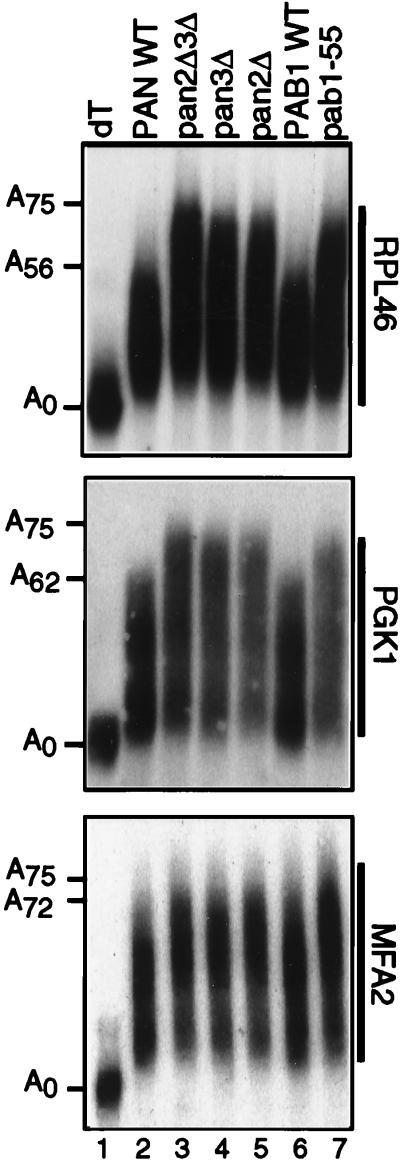

What effect does the loss of poly(A) tail length control due to the absence of PAN have on in vivo mRNA poly(A) tail lengths? To address this question, poly(A) tail lengths of three different mRNAs were compared: MFA2, RPL46, and PGK1. These mRNAs represent three general classes of mRNA stability (52). The MFA2 mRNA is unstable, decaying with a half-life of ∼3.5 min. RPL46 is an intron-containing mRNA, and its mRNA is moderately stable with a half-life of ∼12 min. PGK1 mRNA is stable, with a half-life of ∼45 min. In addition, MFA2 and PGK1 were chosen because their degradation patterns have been well characterized (20, 46, 47).

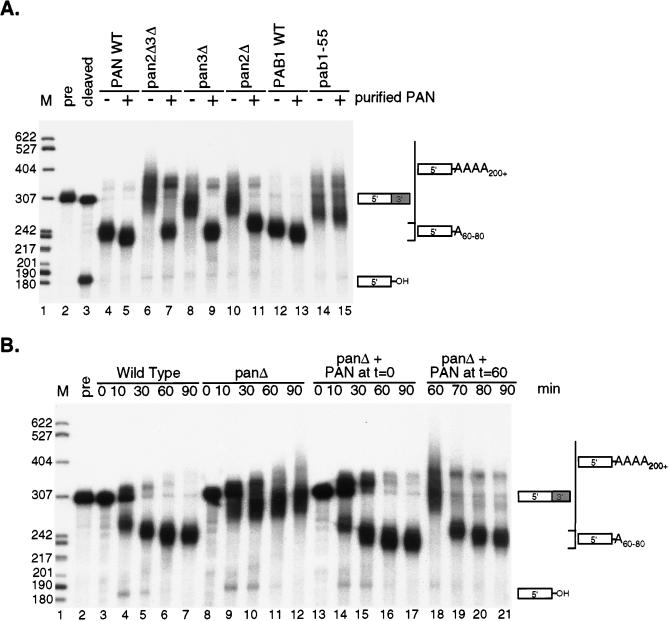

The size distribution of steady-state mRNAs visualized by high-resolution Northern blot analysis shows transcripts with various poly(A) tail lengths (Fig. 5). These mRNAs are in different phases of the deadenylation process, with the longest mRNAs corresponding to the most recently synthesized message. Comparison of transcript lengths in the wild type (Fig. 5, lane 2) and in pan mutants (Fig. 5, lanes 3 to 5) demonstrate that all three messages have longer poly(A) tails at steady state. The transcript sizes of the deadenylated mRNA, achieved by RNase H-directed cleavage in the presence of oligo(dT) (Fig. 5, lane 1), and of the longest polyadenylated transcript can be determined by standardizing to molecular size markers (not shown). Their size difference represents the approximate maximal poly(A) tail length on the mRNA. Table 2 summarizes the maximal poly(A) length measured for each mRNA. In pan mutants, RPL46 and PGK1 mRNAs are approximately 20 and 15 adenylate residues longer, respectively. MFA2 mRNA poly(A) tails are the least affected by a PAN deficiency and are less than 5 adenylate residues longer. However, the distribution of the steady-state MFA2 RNA population is shifted in pan mutants, with a greater percentage of the mRNAs having longer poly(A) tails. The pab1-55 allele also results in a long poly(A) tail phenotype indistinguishable from that of the pan mutants (Fig. 5, compare lane 7 and lanes 3 to 5). This again is consistent with the requirement for the C terminus of Pab1p for the activation of PAN. On the basis of these and our in vitro data, we hypothesize that the longer poly(A) tails observed in the PAN-deficient and pab1-55 yeast strains arise from aberrant length control during or just after the polyadenylation reaction.

FIG. 5.

Maximal mRNA poly(A) tail lengths are increased in pan and pab1 mutant yeast strains. A polyacrylamide Northern blot was hybridized with probes specific for RPL46 (top panel), PGK1 (middle panel) and MFA2 (bottom panel) mRNAs. To resolve PGK1 poly(A) tails, total RNA was first treated with RNase H in the presence of oligonucleotide ORP70 (20). The RPL46 and MFA2 mRNAs were detected with a randomly primed, labeled BamHI-SalI probe of pAS142 and a HindIII probe of pAS139, respectively. The PGK1 mRNA was detected with the end-labeled oligonucleotide OAS325 (5′ TTGATCTATCGATTTCAATTCAATTCAATTT). Lane 1, deadenylated transcript (A0) by RNase H treatment of total RNA in the presence of oligo(dT); lane 2, wild-type (WT) yeast strain YAS306; lane 3, pan2Δ pan3Δ mutant strain YAS2283; lane 4, pan3Δ mutant yeast strain YAS1943; lane 5, pan2Δ mutant yeast strain YAS1942; lane 6, PAB1 wild-type yeast strain YAS1254; lane 7, pab1-55 mutant yeast strain YAS1255. The estimated sizes of the poly(A) tails are indicated to the left.

TABLE 2.

Maximal mRNA poly(A) tail lengths

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Maximal poly(A) tail lengtha in endogenous mRNA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPL46 | PGK1 | MFA2 | ||

| YAS306 | PAN | 55 ± 5 | 61 ± 3 | 71 ± 2 |

| YAS1254 | PAB1 | 57 ± 6 | 63 ± 1 | 72 ± 6 |

| YAS2283 | pan2Δ pan3 | 76 ± 3 | 75 ± 3 | 74 ± 5 |

| YAS1943 | pan3Δ | 74 ± 2 | 74 ± 4 | 75 ± 5 |

| YAS1942 | pan2Δ | 75 ± 2 | 76 ± 2 | 75 ± 5 |

| YAS1255 | pab1-55 | 74 ± 1 | 74 ± 4 | 77 ± 7 |

Maximal poly(A) tail lengths were quantified by using Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software. Values are the averages ± standard deviations from three experiments. Poly(A) tail lenths were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

PAN processing is rapid and message specific.

An interesting observation that arose from our in vivo analysis was that the RPL46, PGK1, and MFA2 mRNAs in wild-type strains each had different maximal steady-state poly(A) tail lengths, measured to be ∼55, ∼60, and ∼70 adenylate residues, respectively. In comparison, the maximum poly(A) tail lengths detected for pan mutants appeared to be more homogeneous, averaging 75 adenylate residues independent of the mRNA examined (Table 2). We hypothesized that the longer poly(A) tails harbored in pan mutants represent a default polyadenylation length that occurs in the absence of intact length control mechanisms. Therefore, the RPL46 mRNA would be the most severely affected by a PAN deficiency because it possesses the shortest maximal poly(A) tail lengths of the three mRNAs analyzed in wild-type yeast strains.

Intuitively, one may expect differences in steady-state poly(A) tail lengths to be affected by differences in mRNA stability. For instance, at steady state, the maximal poly(A) tail length for MFA2 could be rationalized to be longer than other more-stable messages because the MFA2 mRNA is rapidly degraded, and this biases the steady-state RNA population toward the newly synthesized, long-tailed transcripts. However, we do not find a correlation between RNA stability and the maximal poly(A) tail length observed. RPL46 mRNA harbors the shortest maximal poly(A) tail length, and its stability is intermediate in value, whereas PGK1 appears to have an intermediate maximal poly(A) tail length and is the most stable of the three mRNAs analyzed.

It is also possible that the maximal steady-state poly(A) tail length could be influenced by the rate of mRNA production. For instance, a stronger promoter could increase the abundance of the newly synthesized mRNA population [i.e., mRNA with long poly(A) tails]. To address this possibility, RPL46, PGK1, and MFA2 were expressed from the GAL1 promoter and again steady-state poly(A) tail lengths were measured (Fig. 6). For the RPL46 construct, the 5′ leader was replaced with the GAL1 leader to allow for specific detection of the GAL1:RPL46 mRNA. The GAL1:PGK1pG and GAL1:MFA2pG constructs have been extensively characterized previously (46, 47). A 3′-UTR poly(G) insertion allows for their specific detection with an oligo(C) hybridization probe. Similar to the previous findings with the natural promoters, the maximal poly(A) tail lengths for GAL1:RPL46, GAL1:PGK1pG, and GAL1:MFA2pG were message specific in wild-type yeast strains and were measured to be 47, 61, and 87 residues, respectively. PAN-deficient yeast strains were again found to harbor longer poly(A) tails in a message-specific manner. Although there are some differences between the maximal poly(A) tail length measured for the endogenous versus galactose-induced mRNAs (i.e., the MFA2 mRNA), the relative effect was the same: RPL46 mRNA has the shortest poly(A) tails, PGK1 has intermediate poly(A) tail lengths, and MFA2 has the longest maximal poly(A) tails. Based on these data, we conclude that the message-specific poly(A) tail lengths measured for RPL46, PGK1, and MFA2 mRNAs are not solely explained by differences in promoter strength and/or mRNA stability. Instead, our observations suggest that mRNAs may be polyadenylated to a default length in the absence of PAN and that PAN is required for a message-specific poly(A) tail length maturation phase.

FIG. 6.

Steady-state poly(A) tail lengths for galactose-induced mRNAs are longer in the absence of PAN. Wild-type (WT) and pan mutant yeast strains harboring the GAL1:RPL46 vector (pAS582), the GAL1:PGK1pG vector (pRP602), and the GAL1:MFA2pG vector (pRP485), were grown to early log phase in galactose-containing medium (YM with 2% galactose lacking uracil). RNA was isolated, and poly(A) tails were resolved as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The GAL1:RPL46 mRNA was detected with the end-labeled oligonucleotide OAS326 (5′ GTTTTTTCTCCTTGACGTTAAAGTATAGAGGTATATTAACAATTTTTTGTTGATAC), complementary to the GAL1 leader. PGK1pG and MFA2pG mRNAs were detected with the end-labeled oligo(C) probe, ORP121 (46). Lanes 1, deadenylated transcript (A0) by RNase H treatment of total RNA in the presence of oligo(dT); lanes 2, wild-type (WT) yeast strains YAS2288 (GAL1:RPL46), YAS2286 (GAL1:PGK1pG), and YAS2284 (GAL1:MFA2pG); lanes 3, pan2Δ pan3Δ mutant yeast strains YAS2289 (GAL1:RPL46), YAS2287 (GAL1:PGK1pG), and YAS2285 (GAL1:MFA2pG). The estimated sizes of the poly(A) tails are indicated to the left.

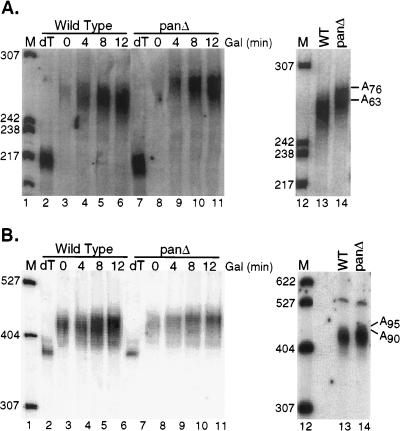

The hypothesis that mRNA poly(A) tails are matured to different maximal tail lengths in vivo is not ideally addressed by examining a steady-state mRNA population but by examining an mRNA population derived from a transcriptional pulse. Such experiments have been previously performed by Decker and Parker (20), whereby the synthesis of several different mRNAs was induced by using the GAL1 promoter. In this work, message-specific poly(A) tail lengths were observed for the newly synthesized pool of transcripts. For instance, induced MFA2, PGK1, STE3, and GAL10 mRNAs were reported to have maximal poly(A) tail lengths of 88 ± 12, 72 ± 17, 62 ± 10, and 58 ± 6 residues, respectively. We chose to carry out similar transcriptional pulse experiments in wild-type and pan mutant yeast strains to analyze the effects of a PAN deficiency on the newly synthesized mRNA population.

Wild type and pan mutant yeast strains harboring plasmids containing GAL1:PGK1pG or GAL1:MFA2pG were pregrown in raffinose-containing medium and transferred to galactose-containing medium. RNA was prepared from culture aliquots removed 0, 4, 8, and 12 min after the galactose shift. New transcription of PGK1pG and MFA2pG was detected as an increase in mRNA abundance following induction with galactose. For the pan mutant yeast strain, the newly synthesized PGK1 mRNA was produced with a maximal poly(A) tail length of ∼76 adenylate residues, whereas in the wild-type yeast strain, PGK1 mRNA was synthesized with maximal poly(A) tail length of ∼63 adenylate residues (Fig. 7A). The maximal MFA2 poly(A) tail length for wild-type and pan mutant yeast strains were measured as ∼90 and ∼95 residues, respectively (Fig. 7B). These lengths are similar to the poly(A) tail lengths measured on the steady-state population of mRNAs derived from the GAL1:PGK1 and GAL1:MFA2 genes (compare Fig. 6 and 7). From the steady-state and transcriptional pulse data, we conclude that PAN activity allows different mRNAs to have different maximal poly(A) tail lengths.

FIG. 7.

Transcriptional pulse of the PGK1 and MFA2 mRNAs in pan mutant and wild-type yeast strains. (A) Wild-type yeast strain YAS2286 and pan mutant yeast strain YAS2287 were pregrown in raffinose and sucrose-containing medium and then shifted to galactose (Gal)-containing medium to induce PGK1pG mRNA. Time points were taken at 0, 4, 8, and 12 min following the galactose (Gal) shift. Lanes 1 and 12, DNA markers (M) with sizes (in nucleotides) indicated to the left; lanes 2 and 7, PGK1pG mRNA treated with RNase H and oligo(dT) to remove the poly(A) tail (A0); lanes 13 and 14, the wild-type (WT) and pan mutant PGK1pG mRNA produced after a 12-min galactose induction were electrophoresed side by side to more easily visualize poly(A) tail length differences. (B) Transcriptional pulse was carried out as described above for panel A, except MFA2pG mRNA was induced in the wild-type yeast strain YAS2284 and the pan mutant yeast strain YAS2285.

A critical observation is that for wild-type yeast, the first PGK1 transcripts detected by Northern blot analysis have already undergone PAN-specific processing. This result implies that in vivo PAN processing is rapid and cannot be functionally separated from the nuclear 3′-end processing of the mRNA with our assays. Although the rapidity with which PAN functions in vivo suggests that the PAN enzyme may reside in the nucleus, further work defining its site of action needs to be performed.

DISCUSSION

Fundamental to the RNA 3′-end processing reaction is the specific and discrete length to which the newly synthesized mRNA poly(A) tail is processed. In this report, we demonstrate that proper poly(A) tail length control in the yeast S. cerevisiae requires deadenylation by the Pab1p-dependent PAN. Our evidence that PAN RNase activity is necessary to determine proper poly(A) tail synthesis lengths is based on both in vitro and in vivo results. RNA 3′-end processing extracts, lacking PAN, produced transcripts with longer than normal poly(A) tails, and wild-type poly(A) tail lengths could be restored by adding the purified PAN enzyme before or after the long, heterogeneous poly(A) tails were synthesized. Furthermore, yeast strains deficient for either or both of the two PAN subunits harbor mRNAs with longer than normal poly(A) tails in vivo. Interestingly, only two of the three mRNAs analyzed showed a significant increase in poly(A) tail length in the absence of PAN, demonstrating that the PAN effect on poly(A) tail length is message specific (see below). The first synthesized mRNAs detected in vivo have already undergone PAN-dependent poly(A) tail shortening, indicating that PAN processing is rapid. Our data support the model that pre-mRNAs are polyadenylated to a longer default length by the poly(A) polymerase machinery and then deadenylated to a message-specific length by PAN (Fig. 8). Maturation of the mRNA poly(A) tail by PAN occurs rapidly and appears to precede translation and mRNA degradation. Future experiments will address whether PAN-dependent deadenylation occurs in the nucleus as an integral step of the 3′-end processing reaction or instead as an early cytoplasmic mRNA maturation event.

FIG. 8.

Model for mRNA poly(A) tail length control in the yeast S. cerevisiae. Processing of the 3′ end of a pre-RNA begins with cleavage and polyadenylation of the substrate to a default length, ranging from 70 to 90 nucleotides. This default length may, in part, be determined by Pab1p. The PAN RNase then rapidly matures the mRNA poly(A) tail to a message-specific length, ranging from 50 to 90 nucleotides. The fully processed mRNA is then a substrate for both the translation apparatus and the mRNA degradation machinery.

The Pab1 protein has previously been shown to be required for poly(A) tail length control (1, 32, 42). Pab1p can inhibit the activity of the purified yeast poly(A) polymerase (36). Furthermore, we find that addition of excess Pab1p to RNA 3′-end processing extracts decreases the efficiency of polyadenylation in the PAN-deficient extract. Our results suggest that at high concentrations of Pab1p, the necessity for PAN in poly(A) tail length control in vitro becomes less obvious. This putative role for Pab1p in limiting the length of the synthesized poly(A) tail would be most similar to the role ascribed to the mammalian nuclear PABII protein, a poly(A)-binding protein distinct from Pab1p. The PABII protein, in combination with the cleavage and specificity factor CPSF, has been shown to specify the synthesis length of the poly(A) tail in vitro by promoting the termination of processive polyadenylation (67). Our observations suggest that Pab1p can also inhibit, at certain concentrations, the polyadenylation reaction. We are currently investigating the specificity and physiological relevance of this inhibition.

It is important to note that the Pab1p-dependent inhibition of polyadenylation is not sufficient to determine proper poly(A) tail length control (Fig. 4). Instead, we have demonstrated that a major role for Pab1p in the polyadenylation reaction is to activate the PAN RNase. The PAN enzyme is present in 3′-end processing extracts and is required for proper poly(A) tail length control. The yeast 3′-end processing machinery has been separated into four fractions (CFI, CFII, PFI, and PAP1) by ion-exchange chromatography (15), and future experiments will be aimed at addressing the possible copurification of the PAN enzyme with one of these fractions. Our conclusions are in opposition to the those of Amrani et al. (1), who were unable to detect exonuclease activities involved in poly(A) tail length control; at this time, the reason for the difference between our observations is not readily apparent.

Is deadenylation a conserved mechanism for poly(A) tail length control in other eukaryotes? The Pan2 and Pan3 subunits are homologous to proteins in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Caenorhabditis elegans, suggesting that the PAN enzyme has been evolutionarily conserved. Furthermore, variations in nuclear mRNA poly(A) tail length distributions have been previously reported in other eukaryotes (reviewed in reference 5), but it is unclear which aspect of poly(A) tail metabolism is responsible for these changes. Two kinetic phases of poly(A) tail shortening have been reported in mammalian cells: a rapid initial phase and a slower phase, yielding heterogeneous poly(A) tails (5). It is possible that maturation of the poly(A) tail by PAN in S. cerevisiae may be equivalent to the initial phase of deadenylation observed in mammalian cells.

The long poly(A) tail phenotype observed in vivo is not as severe as that observed in vitro. This could be due to several factors. One possibility is that our designation of the maximal poly(A) tail length as being the size at which the Northern blot signal was three- to fivefold over background underestimates the true maximal length. It may be difficult to detect newly synthesized mRNAs with very long and heterogeneous poly(A) tails, since they would most likely constitute only a minority of the steady-state population. Alternatively, there may be a second mechanism that is critical for regulating the processive polyadenylation length in vivo which is lost during the ammonium sulfate fractionation of the extract for the in vitro assays. Such a factor could be a yeast PABII-like molecule or may be related to the different concentrations of Pab1p in the in vitro and in vivo assays. Furthermore, in the competitive cellular environment, there are likely to be competing forces, such as mRNA export or recruitment of the 3′-end processing complex to other newly synthesized pre-RNAs, that limit the time that the polyadenylation machinery associates with the RNA and thus the length of the newly synthesized poly(A) tail.

One major conclusion from our work is that in wild-type yeast strains, mRNAs are produced with message-specific poly(A) tail lengths ranging from between 50 and 90 adenylate residues and that this message specificity is the result of PAN activity. The message-specific differences in poly(A) tail length could affect gene expression by regulating the number of Pab1p proteins bound to the poly(A) tail. The possible mRNA determinants responsible for the message-specific processing by PAN have not been elucidated. However, previous characterization of the purified PAN enzyme demonstrated that its activity could be differentially modulated by various 3′-UTR sequences (37). Future experiments will be aimed at testing the possibility that 3′-UTR sequences are important in regulating message specific poly(A) tail synthesis lengths.

An intriguing property of the PAN RNase is that it does not efficiently shorten poly(A) tails to lengths below ∼50 adenylate residues (Fig. 3). This observation suggests that PAN may be sensitive to the number of Pab1 proteins bound to the poly(A) tail. It is possible that PAN is able to detect a change in RNP structure that occurs at a defined poly(A) tail length or that direct activation of the enzyme requires a minimal number of Pab1 proteins. This observation also suggests that PAN is probably not the major cytoplasmic deadenylase involved in mRNA decay, since this deadenylase activity shortens mRNA poly(A) tails to oligo(A) lengths of approximately 5 to 15 nucleotides (20). Previously, we characterized the ability of the purified PAN enzyme to completely remove the mRNA poly(A) tail (37). This is in contrast to our current findings and may be a consequence of several differences in these two assays. For instance, the ionic conditions used in this study are higher than that used in the previous study, a circumstance that might affect the structure of the Pab1p-poly(A) RNP complex. Alternatively, in this study, the purified enzyme is added to a more complex mixture of proteins, including RNA-binding proteins, that may limit the binding of Pab1p and thus the activity of PAN.

The absence of proper poly(A) tail length control in pan mutants does not lead to cell inviability. However, loss of PAN function does stabilize a subset of cellular mRNAs approximately twofold (11a). Furthermore, pan mutants also exhibit growth phenotypes under alternative growth conditions. For instance, mutations in PAN have been shown to cause hypersensitivity to Calcofluor white (38), a drug that has high affinity for yeast cell wall chitin (24). PAN mutants also show increased resistance to high concentrations of copper and hygromycin B (unpublished observations). Most likely, these phenotypes arise because of changes in gene expression due to increases in stability and/or translatability of certain mRNAs.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that correct polyadenylation length control in S. cerevisiae requires a poly(A) tail-shortening phase. This represents a novel and previously uncharacterized role for mRNA deadenylation. The regulation of poly(A) tail synthesis length may allow for yet another level of posttranscriptional control of gene expression. In support of this hypothesis, trinucleotide expansion mutations in the human PABII gene have been reported to cause a form of muscular dystrophy (11). Future research into the mechanism underlying message-specific length control and its ramifications will allow for a deeper understanding of this process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We especially thank Pascal Preker for advice and expertise with the in vitro 3′-end processing reaction and insightful scientific discussions. We thank Roy Parker for generously sharing many critical reagents, including the MFA2pG and PGK1pG vectors. We thank Lev Osherovich and Jen Blanchette for excellent technical and scientific contributions. We thank Terry Platt, Eric Powers, Sandra Wells, and members of the Sachs lab for fruitful comments and for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by NIH grant 50308 to A.B.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amrani N, Minet M, Le Gouar M, Lacroute F, Wyers F. Yeast Pab1 interacts with Rna15 and participates in the control of the poly(A) tail length in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3694–3701. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J, Paddy M, Swanson M. PUB1 is a major nuclear and cytoplasmic polyadenylated RNA-binding protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6102–6112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astrom J, Astrom A, Virtanen A. In vitro deadenylation of mammalian mRNA by a HeLa cell 3′ exonuclease. EMBO J. 1991;10:3067–3071. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astrom J, Astrom A, Virtanen A. Properties of a HeLa cell 3′ exonuclease specific for degrading poly(A) tails of mammalian mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18154–18159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker E J. Control of poly(A) length. In: Belasco J G, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 367–415. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker E J. mRNA polyadenylation: functional implications. In: Harford J B, Morris D R, editors. mRNA metabolism and post-transcriptional gene regulation. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1997. pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beelman C A, Stevens A, Caponigro G, LaGrandeur T E, Hatfield L, Fortner D M, Parker R. An essential component of the decapping enzyme required for normal rates of mRNA turnover. Nature. 1996;382:642–646. doi: 10.1038/382642a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beese L S, Steitz T A. Structural basis for the 3′-5′ exonuclease activity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I: a two metal ion mechanism. EMBO J. 1991;10:25–33. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein P, Peltz S W, Ross J. The poly(A)-poly(A)-binding protein complex is a major determinant of mRNA stability in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:659–670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeck R, Tarun S, Rieger M, Deardorff J, Muller-Auer S, Sachs A B. The yeast Pan2 protein is required for poly(A)-binding protein stimulated poly(A)-nuclease activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:432–438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brais B, Bouchard J-P, Xie Y-G, Rochefort D L, et al. Short GCG expansions in the PABII gene cause oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;18:164–167. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Brown C E. Ph.D. thesis. Berkeley: University of California; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown C E, Tarun S Z, Boeck R, Sachs A B. PAN3 encodes a subunit of the Pab1p-dependent poly(A) nuclease in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5744–5753. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler J S, Sadhale P P, Platt T. RNA processing in vitro produces mature 3′ ends of a variety of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2599–2605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caponigro G, Parker R. Multiple functions for the poly(A)-binding protein in mRNA decapping and deadenylation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2421–2432. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Moore C. Separation of factors required for cleavage and polyadenylation in yeast pre-mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3470–3481. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colgan D F, Manley J L. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis D, Lehmann R, Zamore P D. Translational regulation in development. Cell. 1995;81:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dantonel J-C, Murthy K G K, Manley J L, Tora L. Transcription factor TFIID recruits factor CPSF for formation of 3′ end of mRNA. Nature. 1997;389:399–402. doi: 10.1038/38763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deardorff J A, Sachs A B. Differential effects of aromatic and charged residue substitutions in the RNA binding domains of the yeast poly(A)-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:67–81. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Decker C J, Parker R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1632–1643. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deutscher M P, editor. Methods in enzymology. 182. Guide to protein purification. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox C A, Wickens M. Poly(A) removal during oocyte maturation: a default reaction selectively prevented by specific sequences in the 3′ UTR of certain maternal mRNAs. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2287–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guthrie C, Fink G R, editors. Methods in enzymology. 194. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hampsey M. A review of phenotypes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1099–1133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970930)13:12<1099::AID-YEA177>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu C L, Stevens A. Yeast cells lacking 5′→3′ exoribonuclease 1 contain mRNA species that are poly(A) deficient and partially lack the 5′ cap structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4826–4835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs Anderson J S, Parker R. The 3′ to 5′ degradation of yeast mRNAs is a general mechanism for mRNA turnover that requires the SKI2 DEVH box protein and 3′ to 5′ exonucleases of the exosome complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:1497–1506. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson A. Poly(A) metabolism and translation: the closed-loop model. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Vol. 30. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 451–480. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson A, Peltz S W. Interrelationships of the pathways of mRNA decay and translation in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:693–739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joyce C M, Steitz T A. Function and structure relationships in DNA polymerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:777–822. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller W. No end yet to messenger RNA 3′ processing. Cell. 1995;81:829–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller W, Minvielle-Sebastia L. A comparison of mammalian and yeast pre-mRNA 3′-end processing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:329–336. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler M M, Henry M F, Shen E, Zhao J, Gross S, Silver P A, Moore C L. Hrp1, a sequence-specific RNA-binding protein that shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, is required for mRNA 3′-end formation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2545–2556. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler S H, Sachs A B. RNA recognition motif 2 of yeast Pab1p is required for its functional interaction with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:51–57. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korner C G, Wahle E. Poly(A) tail shortening by a mammalian poly(A)-specific 3′-exoribonuclease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10448–10456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaGrandeur T E, Parker R. Isolation and characterization of Dcp1p, the yeast mRNA decapping enzyme. EMBO J. 1988;17:1487–1496. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lingner J, Radtke I, Wahle E, Keller W. Purification and characterization of poly(A) polymerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8741–8746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowell J E, Rudner D Z, Sachs A B. 3′-UTR-dependent deadenylation by the yeast poly(A) nuclease. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2088–2099. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lussier M, White A M, Sheraton J, diPaolo T, et al. Large scale identification of genes involved in cell surface biosynthesis and architecture in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:435–450. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manley J L, Takagaki Y. The end of the message—another link between yeast and mammals. Science. 1996;274:1481–1482. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCracken S, Fong N, Yankulov K, Ballantyne S, Pan G, Greenblatt J, Patterson S D, Wickens M, Bentley D L. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature. 1997;385:357–361. doi: 10.1038/385357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minvielle-Sebastia L, Preker P, Keller W. RNA14 and RNA15 proteins as components of a yeast pre-mRNA 3′-end processing factor. Science. 1994;266:1702–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.7992054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minvielle-Sebastia L, Preker P J, Wiederkehr T, Strahm Y, Keller W. The major yeast poly(A)-binding protein is associated with cleavage factor 1A and functions in premessenger RNA 3′-end formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7897–7902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Tollervey D. The exosome: a conserved eukaryotic RNA processing complex containing multiple 3′→5′ exoribonucleases. Cell. 1997;91:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrissey, J. P., and A. B. Sachs. Unpublished observations.

- 45.Moser M J, Holley W R, Chatterjee A, Mian I S. The proofreading domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and other DNA and/or RNA exonuclease domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:5110–5118. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muhlrad D, Decker C J, Parker R. Deadenylation of the unstable mRNA encoded by the yeast MFA2 gene leads to decapping followed by 5′→3′ digestion of the transcript. Genes Dev. 1994;8:855–866. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muhlrad D, Decker C J, Parker R. Turnover mechanisms of the stable yeast PGK1 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2145–2156. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muhlrad D, Parker R. Mutations affecting stability and deadenylation of the yeast MFA2 transcript. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2100–2111. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Regulatable promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison of transcriptional activity and their use for heterologous expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5767–5768. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neugebauer K M, Roth M B. Transcription units as RNA processing units. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3279–3285. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nonet M, Scafe C, Sexton J, Young R. Eucaryotic RNA polymerase conditional mutant that rapidly ceases mRNA synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1602–1611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.5.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peltz S W, Jacobson A. mRNA turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Belasco J, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 291–328. [Google Scholar]

- 52a.Preker P J, Lingner J, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Keller W. The FIP1 gene encodes a component of a yeast pre-mRNA polyadenylation factor that directly interacts with poly(A) polymerase. Cell. 1995;81:379–389. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sachs A B, Davis R W. The poly(A) binding protein is required for poly(A) shortening and 60S ribosomal subunit-dependent translation initiation. Cell. 1989;58:857–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sachs A B, Davis R W, Kornberg R D. A single domain of yeast poly(A)-binding protein is necessary and sufficient for RNA binding and cell viability. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3268–3276. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sachs A B, Sarnow P, Hentze M W. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eucaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salles F J, Lieberfarb M E, Wreden C, Gergen J P, Strickland S. Coordinate initiation of Drosophila development by regulated polyadenylation of maternal messenger RNAs. Science. 1994;266:1996–1999. doi: 10.1126/science.7801127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheets M, Wu M, Wickens M. Polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA as a control point in Xenopus meiotic maturation. Nature. 1995;374:511–516. doi: 10.1038/374511a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheets M D, Fox C A, Hunt T, Woude G V, Wickens M. The 3′-untranslated regions of c-mos and cyclin mRNAs stimulate translation by regulating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:926–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shyu A-B, Belasco J G, Greenberg M E. Two distinct destabilizing elements in the c-fos message trigger deadenylation as a first step in rapid mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 1991;5:221–231. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tarun S, Sachs A B. A common function for mRNA 5′ and 3′ ends in translation initiation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tarun S Z, Sachs A B. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tarun S Z, Wells S E, Deardorff J A, Sachs A B. Translation initiation factor eIF-4G mediates in vitro poly(A) tail-dependent translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9046–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tharun S, Parker R. Mechanisms of mRNA turnover in eukaryotic cells. In: Harford J B, Morris D R, editors. mRNA metabolism and post-transcriptional gene regulation. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1997. pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Varnum S M, Wormington W M. Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation does not require specific cis-sequences: a default mechanism for translational control. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2278–2286. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wahle E. A novel poly(A)-binding protein acts as a specificity factor in the second phase of messenger RNA polyadenylation. Cell. 1991;66:759–768. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90119-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wahle E. Poly(A) tail length control is caused by termination of processive synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2800–2808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wahle E, Kuhn U. The mechanism of 3′ cleavage and polyadenylation of eukaryotic pre-mRNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1997;57:41–71. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]