Abstract

Drawing on the social compensation hypothesis, this study investigates whether Facebook use facilitates social connectedness for individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI), a common and debilitating medical condition that often results in social isolation. In a survey (N = 104 participants; n = 53 with TBI, n = 51 without TBI), individuals with TBI reported greater preference for self-disclosure on Facebook (vs. face-to-face) compared to noninjured individuals. For noninjured participants, a preference for Facebook self-disclosure was associated with the enactment of relational maintenance behaviors on Facebook, which was then associated with greater closeness with Facebook friends. However, no such benefits emerged for individuals with TBI, whose preference for Facebook self-disclosure was not associated with relationship maintenance behaviors on Facebook, and did not lead to greater closeness with Facebook friends. These findings show that the social compensation hypothesis has partial utility in the novel context of TBI, and suggest the need for developing technological supports to assist this vulnerable population on social media platforms.

Keywords: relationship maintenance, self-disclosure, social compensation hypothesis, traumatic brain injury, social media, computer-mediated communication

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects ∼1.7 million Americans annually and is a leading cause of long-term disability.1 TBI can disrupt survivors' sensorimotor, psychological, and cognitive functions2 and cause lifelong social disability.3 Indeed, individuals with TBI commonly report loss of friends4 and loneliness.5

Social media has gained prominence as a tool for connecting the world6 and could reduce social isolation after TBI. Individuals with TBI report both interest in social media and barriers in access,7,8 and potential benefits to this population are unknown. Thus, we ask: Does social media offer social benefits to people with TBI, fostering closeness with online friends?

Drawing on the social compensation hypothesis,9–11 we examine the extent to which individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI prefer to self-disclose on social media versus in face-to-face (FtF) interactions, enact relationship maintenance behaviors12,13 on social media, and report closeness with social media friends as a result. To understand the unique role of social media in these processes, we include a sample of noninjured adults for comparison. Our analyses focus on Facebook, the social media platform most consistently used by U.S. adults with14–16 and without6 TBI.

Moderate-to-Severe TBI and Social Challenges

TBI severity is classified according to acute injury characteristics (e.g., loss of consciousness, neuroimaging findings).17 Individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI typically experience problems recognizing and expressing emotions, understanding humor and sarcasm, remembering information, and following along on conversations as topics and speakers change.18,19 A particular issue is inappropriate self-disclosure, as this group typically overshare personal information20 and feel self-conscious in social interactions.4 These impairments can lead to loss of relationships and social support after injury,4,21 reduced participation in social and leisure activities,5 and difficulty making friends.22 While these negative social consequences can occur for anyone with a brain injury, they are more common for those with moderate-to-severe TBI. It is unsurprising then that the latter report more loneliness and poorer quality of life than those without TBI,23 prompting recommendations to consider friendship maintenance as a key element in supporting individuals well-being post-TBI.4,24

Social Compensation Hypothesis

The social compensation hypothesis proposes that individuals who struggle with initiating and maintaining relationships FtF could benefit from interacting online.9 The hypothesis delineates two categories of factors that cause relationship difficulties in FtF environments: stable individual differences (e.g., low social competence,25,26 introversion,27 low self-esteem28,29) and internalizing disorders (e.g., social anxiety,30,31 loneliness,32 depression23,33). Collectively, these factors are referred to as psychosocial vulnerabilities.34

The social compensation hypothesis makes two predictions. First, individuals with psychosocial vulnerabilities will prefer computer-mediated communication (CMC) over FtF because the former is more comfortable, controllable, and easily accessible.26,35–38 Second, the preference for CMC will lead these individuals to engage in more social interaction online and to derive more benefits from it, such as making new friends and feeling closer to online friends, than their counterparts without psychosocial vulnerabilities.

Supporting these predictions, a strong preference for CMC over FtF has been documented among socially anxious adolescents11 and adults,31,39,40 lonely adolescents,41 and online daters with anxiety and depression.34 Individuals with psychosocial vulnerabilities engage in more online communication, especially self-disclosure,10,32,40 and derive benefits from it such as higher friendship quality with online friends,30 more online friends,10 greater social capital,12 and more social support.31

Hypotheses

Since TBI interferes with relationship initiation4,21 and is frequently accompanied by internalizing symptoms,22 the social compensation hypothesis should help explain the preferences and behaviors of individuals with TBI. Thus, we predict that individuals with TBI will prefer Facebook over FtF communication. We focus on preferences for Facebook self-disclosure because self-disclosure is the building block of close relationships42 and is difficult for those with TBI due to cognitive limitations. Hence,

H1: Individuals with TBI will have a higher preference for self-disclosure on Facebook (vs. FtF) than individuals without TBI.

Second, we predict that preferences for Facebook self-disclosure among adults with TBI will be associated with the enactment of relationship maintenance behaviors, which, in turn, will produce relational benefits, specifically greater perceived closeness with Facebook friends. On Facebook, relationship maintenance behaviors take the form of offering one-click indicators of support (i.e., “likes” or other reactions), writing comments on others' posts, sending public and private messages, and responding to “friends’” public questions.12,43 These behaviors require little investment of time and effort and have been shown to promote closeness with Facebook friends.43,44

Self-disclosure and relationship maintenance are key, intertwined predictors of relationship closeness.45 Due to reciprocity norms, an individual's increased self-disclosure (a self-focused activity) tends to prompt that individual to also enact more relationship maintenance behaviors (an other-focused activity), resulting in greater relational closeness.46 These associations have been observed in the general population,47 and we expect them to also emerge among individuals with TBI interacting on Facebook, given the ease of enacting relationship maintenance behaviors on social media relative to FtF:

H2: For individuals with TBI, (a) a preference for Facebook self-disclosure will be positively associated with the enactment of Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors, which, in turn (b) will be positively associated with increased relational closeness with Facebook friends.

The social compensation hypothesis predicts that these associations should be stronger for adults with TBI than for those without, because the former should be more comfortable with and invested in managing their social lives online:

H3: The positive associations among preference for Facebook self-disclosure, relationship maintenance behaviors, and relational closeness with Facebook friends will be stronger for individuals with TBI than for those without TBI.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants were adults with moderate-to-severe TBI and a demographically matched comparison group of noninjured adults (Table 1). All participants were recruited from the Vanderbilt Brain Injury Patient Registry.48 Participants completed an online questionnaire regarding their social media preferences and practices.15 Procedures were Institutional Review Board-approved.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| TBI participants | Noninjured participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 53 | 51 |

| Sex/gender (n) | 28 women | 29 women |

| Mean age (years) | 37.7 (SD = 9.6) | 36.4 (SD = 10.4) |

| Mean years of education | 15.0 (SD = 2.6) | 15.1 (SD = 2.1) |

| Race | African American = 1 American Indian/Alaskan Native = 2 White = 5 |

African American = 4 Asian = 2 White = 41 More than one race = 3 Unknown or not reported = 1 |

| Mean years post TBI | 6.5 (SD = 5.5) | N/A |

N/A, not applicable; SD, standard deviation; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Measures

To accommodate cognitive challenges among participants with TBI, all scales contained simplified three-point response options (1 = disagree; 2 = neither agree nor disagree; 3 = agree), following best practices for this population.49–51 For each scale, responses were averaged into an index.

Preference for Facebook self-disclosure (compared to FtF) was measured using Ledbetter's52 well-validated scale for attitudes toward online self-disclosure (seven items; e.g., “When on Facebook, I feel more comfortable disclosing personal information than FtF”; Cronbach's α = 0.87–0.90).

Relational maintenance behaviors on Facebook were measured using the validated relationship maintenance scale by McEwan et al.53 (14 items; e.g., “I post on friends' Facebook newsfeeds”; Cronbach's α = 0.87–0.91).

Relational closeness with Facebook friends was measured using Dibble et al.'s54 relational closeness scale (12 items; e.g., “My relationships with my Facebook friends are close”; Cronbach’ α = 0.85–0.93).

Results

An independent sample t test showed that individuals with TBI displayed a greater preference for Facebook self-disclosure than individuals without TBI, t(83) = −2.856, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 0.51, supporting H1.

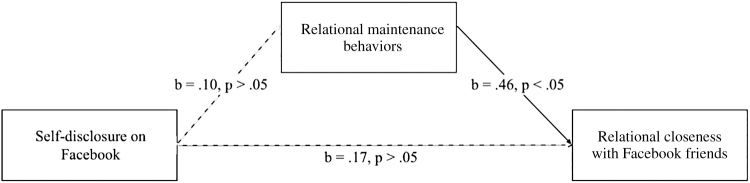

To test H2 and H3, separate mediation models were constructed for individuals with and without TBI. In each model, preference for Facebook self-disclosure was entered as the independent variable, relational closeness with Facebook friends as the dependent variable, and relational maintenance behaviors as the mediator (Figs. 1 and 2).

FIG. 1.

Mediation model for noninjured individuals. Note. Solid lines show significant relationships.

FIG. 2.

Mediation model for individuals with TBI. Note. Dashed lines show non-significant relationships; solid line shows significant relationship. TBI, traumatic brain injury.

For noninjured individuals, preference for Facebook self-disclosure was significantly associated with the enactment of relational maintenance behaviors (b = 0.41, p < 0.01), which was then significantly associated with relational closeness with Facebook friends (b = 0.34, p < 0.05). There was a direct relationship between preference for Facebook self-disclosure and relational closeness with Facebook friends (b = 0.58, p < 0.001), but it was weakened when the mediator (i.e., relational maintenance behaviors) was entered (b = 0.44, p < 0.01).

For H2, the TBI group's preference for Facebook self-disclosure was not significantly associated with the enactment of relational maintenance behaviors on Facebook (b = 0.10, p > 0.05). However, Facebook relational maintenance behaviors were significantly associated with relational closeness with Facebook friends (b = 0.46, p < 0.05). The direct relationship between preference for Facebook self-disclosure and relational closeness with Facebook friends did not reach significance (b = 0.22, p > 0.05), nor was it significant when the mediator (i.e., relational maintenance behaviors) was included (b = 0.17, p > 0.05) (Fig. 2), providing partial support for H2.

Associations between the study variables only emerged for noninjured individuals; thus, H3 was not supported. However, it is worth noting that there were no significant mean differences between those with and without TBI for Facebook relational maintenance behaviors or closeness with Facebook friends (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Variables

| Self-disclosure on Facebook |

Relational maintenance behaviors on Facebook |

Relational closeness with Facebook friends |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| TBI (n = 53) | 1.63 | 0.57 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 1.62 | 0.43 |

| NC (n = 51) | 1.32 | 0.44 | 0.83 | 0.46 | 1.49 | 0.50 |

NC, noninjured control.

Discussion

Social network sites are described as “social supernets”55 because they allow users to connect with others with low effort.28,56 We examined whether such benefits emerged for individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI, who are at high risk for loneliness.

Results paint a complex picture. On the one hand, adults with TBI reported greater preferences for self-disclosing on Facebook versus FtF. They also reported engaging in as many relationship maintenance behaviors and experiencing as much closeness with Facebook friends as those without TBI. These findings suggest that Facebook might help individuals with TBI combat social isolation.

On the other hand, the results reveal limitations in the way Facebook supports individuals with TBI. Among those with TBI, preferences for Facebook self-disclosure did not materialize into perceived closeness with Facebook friends because preferences were not linked with the enactment of relationship maintenance behaviors, as was the case for noninjured individuals. Participants with TBI showed a breakdown in this relationship-enhancing chain, as their preference for disclosing on Facebook was not associated with other-oriented communication, such as expressing support, showing interest, and responding to others' messages. These relational maintenance behaviors may be difficult to orchestrate because they involve high-level, theory-of-mind calculations, such as understanding the needs and preferences of relational partners.57,58 It is also possible that due to the tendency of adults with TBI to overshare,20 they might disclose indiscriminately rather than in a directed way that will maintain friendships. The controllability and ease of access of social media may be insufficient for redressing these cognitive difficulties.

While the social compensation hypothesis was useful in explaining preferences for Facebook interaction in adults with TBI, it did not adequately describe their behaviors on this platform, perhaps because participants' cognitive impairments prevented them from using Facebook in ways that would yield relational benefits.

Practical implications

There is evidence that individuals with TBI enjoy using social media platforms,7,8,14–16,59 so social media could be a tool to help this group combat social isolation. However, social media sites may currently lack accessibility and usability features to support users with cognitive impairments. Such features could include conversation prompts, reminders to respond to others' messages or to contact others, or a menu of suggestions from which to pick the best message.60 Streamlining and simplifying interfaces, especially by highlighting information from closer friends, might also be beneficial.

Limitations and Future Direction

Studying TBI has unique challenges. It is difficult to recruit individuals with TBI for lab studies, which restricts sample size. Since participants' cognitive impairments limited questionnaire length and complexity, we focused only on a small set of key variables and simplified response options. Our study was a cross-sectional survey. Future longitudinal studies may inform how social media engagement affects adults with TBI's friendships and provide evidence of causality. The self-reported measures, while appropriate for capturing participants' preferences and perceived closeness with online friends, may be less accurate in capturing their actual relationship maintenance behaviors. For instance, individuals with TBI may overreport the extent to which they engage in relationship maintenance. Future research should employ content analyses of posts and private messages to capture these behaviors more objectively.

Conclusion

Social media platforms like Facebook have been connecting the world, keeping relationships alive, and fostering new ones. This study shows that many of these social benefits extend to individuals with TBI, a vulnerable population. However, access is not enough; we must also support adults with TBI in using these platforms to their full social potential.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the participants in this study. We thank Nirav Patel for his role in participant recruitment.

Authors' Contributions

C.L.T.: Conceptualization (equal), writing—original draft (lead), methodology (lead), formal analysis (supporting), writing—review and editing (equal). J.H.: Writing—original draft (supporting), methodology (supporting), formal analysis (lead), writing—review and editing (equal). L.K.: Writing—original draft (supporting), writing—review and editing (equal). E.L.M.: Data curation (lead). L.S.T., M.C.D., and B.M.: Conceptualization (equal), writing and editing (supporting).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Vanderbilt University, and the research was completed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013.

Data Access Statement

All relevant data are within the article and its Supporting Information files.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Funding Information

This work was supported by grant NIH/NCMRR RO1-HD071089-06A1 from the National Institute of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Note

a. The Vanderbilt Brain Injury Patient Registry invites individuals with and without brain injury to be part of a standing pool of research participants for large-scale basic and translational research on acquired brain injury. In addition to experimental data collection, the Registry also collects demographic information and neuropsychological and neuroanatomical data to better inform tracking and prediction of long-term outcomes.

References

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Traumatic brain injury. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 2022. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/traumatic-brain-injury-tbi [Last accessed: November 16]. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Getting Better After a Mild TBI or Concussion. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/concussion/getting-better.html [Last accessed: October 26].

- 3. Feuston JL, Marshall-Fricker CG, M. PA. The Social Lives of Individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury. Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Douglas J. Loss of friendship following traumatic brain injury: A model grounded in the experience of adults with severe injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2020;30(7):1277–1302; doi: 10.1080/09602011.2019.1574589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLean AM, Jarus T, Hubley AM, et al. Associations between social participation and subjective quality of life for adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36(17):1409–1418; doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.834986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pew Research Center. Social Media Use in 2021. Pew Research Center; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brunner M, Hemsley B, Palmer S, et al. Review of the literature on the use of social media by people with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Disabil Rehabil 2015;37(17):1511–1521; doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1045992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brunner M, Palmer S, Togher L, et al. ‘I kind of figured it out’: The views and experiences of people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in using social media-self-determination for participation and inclusion online. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2019;54(2):221–233; doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McKenna KYA, Bargh JA. Plan 9 from cyberspace: The implications of the internet for personality and social psychology. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 2000;4(1):57–75; doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0401_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peter J, Valkenburg PM, Schouten AP. Developing a model of adolescent friendship formation on the Internet. CyberPsychol Behav 2005;8:423–430; doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Preadolescents' and adolescents' online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev Psychol 2007;43:267–277; doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ellison NB, Vitak J, Gray R, et al. Cultivating social resources on social network sites: Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. J Comput Med Commun 2014;19:855–870; doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellison N, Boyd DM. Sociality through social network sites. In: Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies. (Dutton WH. ed.) Oxford University Press; 2013; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker-Sparr C, Hart T, Bergquist T, et al. Internet and social media use after traumatic brain injury: A traumatic brain injury model systems study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2018;33(1):E9–E17; doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morrow EL, Zhao F, Turkstra L, et al. Computer-mediated communication in adults with and without moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury: Survey of social media use. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2021;8(3):e26586; doi: 10.2196/26586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsaousides T, Matsuzawa Y, Lebowitz M. Familiarity and prevalence of Facebook use for social networking among individuals with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2011;25(12):1155–1162; doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.613086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malec JF, Brown AW, Leibson CL, et al. The mayo classification system for traumatic brain injury severity. J Neurotrauma 2007;24(9):1417–1424; doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Byom L, Turkstra LS. Cognitive task demands and discourse performance after traumatic brain injury. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2017;52(4):501–513; doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. MacDonald S. Introducing the model of cognitive-communication competence: A model to guide evidence-based communication interventions after brain injury. Brain Inj 2017;31(13–14):1760–1780; doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1379613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Osborne-Crowley K, McDonald S. A review of social disinhibition after traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychol 2018;12(2):176–199; doi: 10.1111/jnp.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rowlands A. Understanding social support and friendship: Implications for intervention after acquired brain injury. Brain Impairment 2000;1(2):151–164; doi: 10.1375/brim.1.2.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salas CE, Casassus M, Rowlands L, et al. “Relating through sameness”: A qualitative study of friendship and social isolation in chronic traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2018;28(7):1161–1178; doi: 10.1080/09602011.2016.1247730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salas CE, Rojas-Libano D, Castro O, et al. Social isolation after acquired brain injury: Exploring the relationship between network size, functional support, loneliness and mental health. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2022;32(9):2294–2318; doi: 10.1080/09602011.2021.1939062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amati V, Meggiolaro S, Rivellini G, et al. Social relations and life satisfaction: The role of friends. Genus 2018;74(1):7; doi: 10.1186/s41118-018-0032-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poley MEM, Luo S. Social compensation or rich-get-richer? The role of social competence in college students' use of the internet to find a partner. Comp Hum Behav 2012;28:414–419; doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruppel EK. Preference for and perceived competence of communication technology affordances in face-threatening scenarios. Commun Rep 2018;31(1):53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coduto KD, Lee-Won RJ, Baek YM. Swiping for trouble: Problematic dating application use among psychosocially distraught individuals and the paths to negative outcomes. J Soc Person Relat 2020;37(1):212–232; doi: 10.1177/0265407519861153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. J Comput Med Commun 2007;12:1143–1168; doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zywica J, Danowski J. The Faces of Facebookers: Investigating Social Enhancement and Social Compensation Hypotheses; Predicting Facebook™ and Offline Popularity from Sociability and Self-Esteem, and Mapping the Meanings of Popularity with Semantic Networks. J Comput Med Commun 2008;14(1):1–34; doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.01429.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Desjarlais M, Willoughby T. A longitudinal study of the relation between adolescent boys and girls' computer use with friends and friendship quality: Support for the social compensation or the rich-get-richer hypothesis? Comput Hum Behav 2010;26:896–905; doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ruppel EK, McKinley CJ. Social support and social anxiety in use and perceptions of online mental health resources: Exploring social compensation and enhancement. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18(8):462–467; doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bonetti L, Campbell MA, Gilmore L. The relationship of loneliness and social anxiety with children's and adolescents' online communication. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2010;13(3):279–285; doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morton MV, Wehman P. Psychosocial and emotional sequelae of individuals with traumatic brain injury: A literature review and recommendations. Brain Inj 1995;9(1):81–92; doi: 10.3109/02699059509004574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Toma CL. Online dating and psychological wellbeing: A social compensation perspective. Curr Opin Psychol 2022;46:101331; doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Feaster JC. Expanding the impression management model of communication channels: An information control scale. J Comput Med Commun 2010;16(1):115–138; doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2010.01535.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rains SA, Brunner SR, Akers C, et al. Computer-mediated communication (CMC) and social support: Testing the effects of using CMC on support outcomes. J Soc Person Relation 2017;34:1186–1205; doi: 10.1177/0265407516670533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Sullivan B. What you don't know won't hurt me. Hum Commun Res 2000;26(3):403–431; doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00763.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caplan SE. A social skill account of problematic Internet use. J Commun 2005;55:721–736; doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb03019.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caplan SE. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic Internet use. Cyberpsychol Behav 2007;10(2):234–242; doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weidman AC, Fernandez KC, Levinson CA, et al. Compensatory internet use among individuals higher in social anxiety and its implications for well-being. Pers Individ Dif 2012;53(3):191–195; doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peter J, Valkenburg PM. Research note: Individual differences in perceptions of internet communication. Eur J Commun 2006;21(2):213–226; doi: 10.1177/0267323105064046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim JaDK. Online self-disclosure: A review of research. 2011.

- 43. Vitak J. Facebook Makes the Heart Grow Fonder: Relationship Maintenance Strategies among Geographically Dispersed and Communication-Restricted Connections. Association for Computing Machinery; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ledbetter AM, Mazer JP, DeGroot JM, et al. Attitudes toward online social connection and self-disclosure as predictors of Facebook communication and relational closeness. Commun Res 2011;38:27–53; doi: 10.1177/0093650210365537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tardy CH, Smithson J.. Self-disclosure: Strategic revelation of information in personal and professional relationships 1. In: The Handbook of Communication Skills. (Hargie O. ed.) Routledge: London; 2018; pp. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dindia K. Self-disclosure research: Knowledge through meta-analysis. In: Interpersonal Communication Research: Advances Through Meta-Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA; 2002; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stafford L, Kuiper K.. Social Exchange Theories: Calculating the Rewards and Costs of Personal Relationships. In: Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication: Multiple Perspectives. (Braithwaitez DO, Schrodt P. eds.) Routledge: New York, NY, USA; 2021; pp. 379–390. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Duff MC, Morrow EL, Edwards M, et al. The value of patient registries to advance basic and translational research in the area of traumatic brain injury. Front Behav Neurosci 2022;16:846919; doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.846919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Teasdale TW, Engberg AW. Subjective well-being and quality of life following traumatic brain injury in adults: A long-term population-based follow-up. Brain Inj 2005;19(12):1041–1048; doi: 10.1080/02699050500110397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van den Broek MD, Monaci L, Smith JG. Clinical utility of the Personal Problems Questionnaire (PPQ) in the assessment of non-credible complaints. J Exp Psychopathol 2012;3:825–834; doi: 10.5127/jep.024311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilk JE, Herrell RK, Wynn GH, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury (concussion), posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in U.S. soldiers involved in combat deployments: Association with postdeployment symptoms. Psychosom Med 2012;74(3):249–257; doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244c604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ledbetter AM. Measuring Online Communication Attitude: Instrument Development and Validation. Commun Monographs 2009;76(4):463–486; doi: 10.1080/03637750903300262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McEwan B, Fletcher J, Eden J, et al. Development and Validation of a Facebook Relational Maintenance Measure. Commun Methods Measures 2014;8(4):244–263; doi: 10.1080/19312458.2014.967844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dibble JL, Levine TR, Park HS. The Unidimensional Relationship Closeness Scale (URCS): Reliability and validity evidence for a new measure of relationship closeness. Psychol Assess 2012;24(3):565–572; doi: 10.1037/a0026265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Donath J. Signals in Social Supernets. J Comput Med Commun 2007;13(1):231–251; doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00394.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Johnston K, Tanner M, Lalla N, et al. Social capital: The benefit of Facebook ‘friends’. Behav Inform Technol 2013;32(1):24–36; doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2010.550063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Allain P, Hamon M, Saoût V, et al. Theory of mind impairments highlighted with an ecological performance-based test indicate behavioral executive deficits in traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol 2020;10:1367; doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lin X, Zhang X, Liu Q, et al. Theory of mind in adults with traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021;121:106–118; doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brunner M, Hemsley B, Togher L, et al. Social media and people with traumatic brain injury: A metasynthesis of research informing a framework for rehabilitation clinical practice, policy, and training. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2021;30(1):19–33; doi: 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lim H, Kakonge L, Hu Y, et al. So, I Can Feel Normal: Participatory Design for Accessible Social Media Sites for Individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury. Association for Computing Machinery: Hamburg, Germany; 2023. [Google Scholar]