Abstract

Background: Crohn’s disease is a chronic ailment affecting the gastrointestinal tract. Mucosal healing, a marker of reduced disease activity, is currently assessed in the colonic sections using ileocolonoscopy and magnetic resonance enteroscopy. Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers visualization of the entire GI mucosae.

Objective: To validate a Crohn’s disease model estimating the budget impact of VCE compared with the standard of care (SOC) in Italy.

Methods: A patient-level, discrete-event simulation was developed to estimate the budget impact of VCE compared with SOC for Crohn’s disease surveillance over 5 years in the Italian setting. Input data were sourced from a physician-initiated study from Sant’Orsola-Malpighi Hospital in Bologna, Italy, and the literature. The care pathway followed hospital clinical practice. Comparators were the current SOC (ileocolonoscopy, with or without magnetic resonance enteroscopy) and VCE. Sensitivity analysis was performed using 500-patient bootstraps. A comparative analysis regarding clinical outcomes (biologics use, surgical interventions, symptom remission) was performed to explore the validity of the model compared with real-world data. Cumulative event incidences were compared annually and semi-annually. Bayesian statistical analysis further validated the model.

Results: Implementing VCE yielded an estimated €67 savings per patient per year, with savings in over 55% of patients, compared with SOC. While annual costs are higher up to the second year, VCE becomes cost saving from the third year onward. The real-world validation analysis proved a good agreement between the model and real-world patient records. The highest agreement was found for biologics, where Bayesian analysis estimated an 80.4% probability (95% CI: 72.2%-87.5%) that a decision maker would accept the result as an actual reflection of real-world data. Even where trend data diverged (eg, for surgery [43.1% likelihood of acceptance, 95% CI: 33.7%-52.8%]), the cumulative surgery count over 5 years was within the margin of error of the real-world data.

Conclusions: Implementing VCE in the surveillance of patients with Crohn’s disease and small bowel involvement may be cost saving in Italy. The congruence between model predictions and real-world patient records supports using this discrete-event simulation to inform healthcare decisions.

Keywords: surgery, biologics, symptomatology, remission, Crohn’s disease management, capsule endoscopy

BACKGROUND

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing, and heterogeneous inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, most often diagnosed in the terminal ileum and the colon.1–4 The standard of care (SOC) for diagnosing and monitoring CD is a combination of ileocolonoscopy (ILE), which allows for direct visualization and biopsy of the lower GI mucosa, and magnetic resonance enteroscopy (MRE) for the indirect assessment in the small bowel and upper GI tract.3,5 Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) has emerged as a versatile tool for noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of CD throughout the small intestine,2,6 with the same sensitivity as SOC in the lower GI tract7 and better specificity than MRE in the small bowel.8,9 VCE also provides an accurate assessment of mucosal healing, a widely accepted marker of remission,3,10,11 and better patient acceptance.12–14 VCE may allow for a readier and more adaptable therapeutic follow-up, particularly in the medium- to long-term management of small bowel lesions,7 where it showed the potential to optimize the management of CD.15

VCE has garnered attention as a minimally invasive diagnostic in various settings, particularly for evaluating and monitoring CD.16–20 However, VCE’s health-economic implications in CD surveillance remain understudied,21 without evidence specific to Italian healthcare. We had previously shown VCE as a cost-effective alternative in the mid-to-long term in the United Kingdom and United States, with higher initial costs recouped through improved management over time, using a patient-level discrete-event simulation model.22,23 However, the model lacks external validation for its accuracy against real-world data. Therefore, this work leverages published data from Calabrese et al,15 adapting the model to the local specifics and estimating the potential budget impact of adopting VCE compared with the SOC (ILE ± MRE) for CD surveillance in Italy. To determine the validity of this model, we assessed the model’s precision on clinical outcomes relevant to resource use and management of CD by comparing the generated longitudinal patient and real-world patient data, per recommendations from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) and Bayesian statistical analysis.24

METHODS

Analytic Approach

A discrete-event, patient-level simulation (Figure 1) with an underlying semi-Markov model, as described in previous publications,22,23 was adapted to the Italian setting based on expert clinician inputs and available guidelines.3,25–27 The model compares expected outcomes using VCE in CD surveillance in place of SOC (ILE ± MRE) by simulating CD progression based on individual patient characteristics, sensitivity and specificity of diagnostics (VCE or SOC), and treatment efficacy. The model was utilized to calculate the budget impact of introducing VCE in surveillance of patients diagnosed with small bowel CD compared with SOC surveillance. From the publication by Calabrese et al, data on 276 patients with CD were available for the model.15 Each individual-level patient record was replicated 10 times to provide a 2760-simulation set to better account for potential uncertainty.

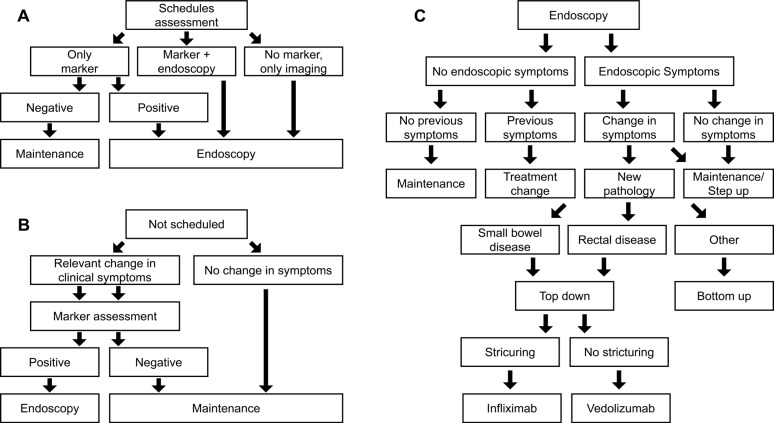

Figure 1. Diagnostic Workflow of the Model.

Patients can be eligible for endoscopic monitoring in each cycle by being regularly scheduled for monitoring (A) or scheduled for monitoring due to disease flare suspicion (B). In both scenarios, a marker test is conducted to confirm disease activity. Patients not scheduled for regular maintenance endoscopy get scheduled for endoscopy upon a positive result of the marker testing. Diagnosed complications result in surgery.

Model overview: The simulation spans 4.5 years of follow-up, using each patient’s first collected data point as a baseline input for the model. Over time, patient characteristics such as age, disease status, clinical disease activity index (CDAI), structuring, and abscess are updated. Age is simply updated in yearly increments, whereas CD-related characteristics are updated each cycle based on an underlying model with, for example, a semi-Markov model used to incorporate CD symptom progression. Each model cycle simulates a period of 3 months. In each cycle, each patient is evaluated for whether there is a scheduled physician visit. If so, then the patient undergoes planned surveillance using one of three options depending on their disease status and symptomatology (Figure 1A). If there was no scheduled physician visit, the patient is assessed for changes in CD symptomatology (eg, flares) that could signal an unplanned physician visit. If these are present, marker assessment with fecal calprotectin (fCal) is performed; otherwise, the patient remains on current maintenance (Figure 1B). Following either approach, patients with a positive market test or scheduled for endoscopy receive endoscopy as either SOC or VCE (depending on the arm of the model) and follow the procedure in Figure 1C to determine a diagnosis and treatment option as required.

Next to the diagnostic workflow of the model, symptom progression is estimated in the underlying semi-Markov process with monthly transitions (Tables S1 and S2); therefore, as a cycle is 3 months in length, multiple disease escalations or regressions per cycle are possible. For example, a patient with mild CD could have a flare in month 1 (of 3), have this resolve in month 2 (of 3), and then enter remission in month 3 (of 3). They would, therefore, in the model follow-up, go from mild CD to remission. Similarly, the same patient could have no change in months 1 and 2 (of 3) and a flare in month 3 (of 3), entering the next model cycle with moderate CD. If mild, moderate, or severe CD persists at the subsequent follow-up then a change in treatment, using either a bottom-up or top-down approach is considered (Figure 1C). The treatment is adjusted if a new pathology has developed (eg, rectal disease or small bowel presentation). Furthermore, the patient is directed to surgery if a complication is diagnosed.

The main model outcomes are the initiation of biologic treatment, biological treatment duration, and evolution of biological utilization through the model time frame. The secondary model’s outcomes are the incidence of surgery and remission. Using the Crohn’s Activity Index as a proxy of symptomatology, remission was defined as an asymptomatic period (CDAI score <150) immediately following active disease (CDAI score ≥150). Staggered degrees of symptomatology and underlying active disease were mild (150 ≤ CDAI < 220), moderate (220 ≤ CDAI < 450), and severe (CDAI ≥ 450).

Model input data: For the baseline set of patients, real-world demographic and clinical outcome data in terms of biologics use, surgery occurrence, and the cumulative incidence of remission and flares were sourced from Calabrese et al,15 a monocentric, matched-cohorts, retrospective, physician-initiated study. It investigated the impact of capsule endoscopy compared to the SOC in patients with CD at the Sant’Orsola-Malpighi Hospital in Bologna, Italy, (IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna–Policlinico di Sant’Orsola) between 1999 and 2019.15 In Calabrese et al, entry into the database prior to 1999, no diagnosed disease location, no initial CDAI, use of VCE in addition to ILE/MRE, and more than 2 consecutive missing data points (1 year) constituted exclusion criteria. Patients with the follow-up data in 6-month intervals up to 5 years after database entry were selected.

Anonymized patient records retained served uniquely as inputs for the model to generate representative cohorts for the two simulation arms. Event incidences and costs were identified in a structured literature review and hand searches. This included data on adverse events and symptomatology, such as subsequent hospitalization, bowel obstruction, GI bleeding, and infection following a capsule retention. Key inputs for each surveillance modality are presented in Table 1. Patient characteristics such as age, time from diagnosis, and time on treatment are updated according to the individual-level procession through the model. Costs were obtained from the 2020 IT-DRG scheme for Emilia Romagna (Table S3).

Table 1. Efficacy, Safety, and Cost Data by Surveillance Modality.

| fCal Test | VCE | Ileocolonoscopy | MRE | |

| Sensitivity | 78.813 | 83%9 SB: 97%9 |

91%9 SB: Not used |

71%9 |

| Specificity | 97.213 | 88%9 SB: 87%9 |

89%9 SB: Not used |

66%9 |

| Subsequent hospitalization | 0% | 0% | 1.63%14 | 0% |

| Bowel obstruction | 0% | 0% | 0.08%15 | 0% |

| GI bleeding | 0% | 0% | 0.42%16 | 0% |

| Infection | 0% | 0% | 4%17 | |

| Capsule retention | ||||

| With patency capsule | 0% | 0%a | 0% | 0% |

| Complete procedures | 100%b | 88.7%18 | 86.9%19 | 100%b |

| Cost per procedure, € (DRG code used) | 12,05 (90.12.A Veneto)28 | 850.00 (45.13.1)29 | 74.00 (45.23)29 | 160.10 (88.95.4)29 |

Together, ileocolonoscopy and MRE form the standard of care.

aBased on medical records, assuming the use of patency capsule.

bAssumed to be always completed.

Abbreviations: fCal, fecal calprotectin; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; SB, small bowel; VCE, video capsule endoscopy.

Sensitivity analysis: One thousand populations, 500 patients each, were bootstrapped to test the robustness of results in a multivariate sensitivity analysis.30 Median and interquartile ranges were estimated on bootstrapped populations. Only patients who had changed management practices were considered in the analysis, with single capsule endoscopy being a criterion during the model time horizon. A ±20% change in cost inputs was used in the one-way sensitivity analysis.

Real-World Validation

An analysis was conducted to explore the external validity of the previously described model comparing the model outcomes with real-world data. To account for uncertainty, each patient was simulated 100 times during validation to account for random sampling and real-life treatment pathway uncertainty. Two outcome definitions (permissive and restrictive) influencing the determination of the compared clinical outcomes, as outlined in Table S4, were used for the analysis. For example, in the permissive definition any 6-month period with a CDAI ≤150 was considered remission, whereas in the restrictive definition this was extended to require a 12-month period with CDAI ≤150.

Under these definitions, and using the 276 baseline patient records, 27 600 simulated patients were to be funneled through the model. Clinical outcomes were compared between the model and real-world data. The cumulative incidence and the disease burden of clinical outcomes in terms of resource use (use of biologics and number of surgeries) and the course of disease (duration of remission) were compared to explore the goodness of the model.

Bayesian Validation

The model was validated for its accuracy in predicting biologics treatment, surgeries, and remission using the Bayesian approach that Corro Ramos and colleagues proposed.31 The method assumes a 50% probability that a hypothetical decision maker would accept the model results as an accurate representation of the true value. The model’s success rate in predicting the empirical outcome is then determined to calculate the likelihood that the decision maker would accept the results, starting from the initial assumption of 50% acceptance. The model validity was computed as the likelihood of acceptance based on the proximity to the empirical value (ie, the model output is considered valid if within the uncertainty interval of the real value ≥50% of the time). Validity percentages were calculated at 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% proximity. The validity analysis was also conducted, assuming a target acceptance rate of 80%. As cumulative data is unsuitable for competing-risk analyses and does not fulfill the proportional hazard requirement for survival analysis, hypothesis tests were not performed. Nonetheless, cumulative series are presented for visual comparison.

Data Segregation

The discrete-event simulation used peer-reviewed published literature for all outcome events and transition probabilities. R.T.T. and R.S. developed and adapted the model to the Italian setting. No real-world patient data were used during the model development phase.

RESULTS

Model Results and Cost Calculations

We gauged the budget impact of implementing VCE in monitoring patients with small bowel CD diagnoses compared with using exclusively SOC (base case) in the validated model. To account for uncertainty, each patient was reproduced 10 times to provide an overall population of 2760. The model estimated mean annual costs of €6047 per patient in the base case vs €5980 per patient in the VCE scenario. VCE in the surveillance of patients with CD and small bowel involvement saved, on average, €67 per patient per year, or €221 by year 5.

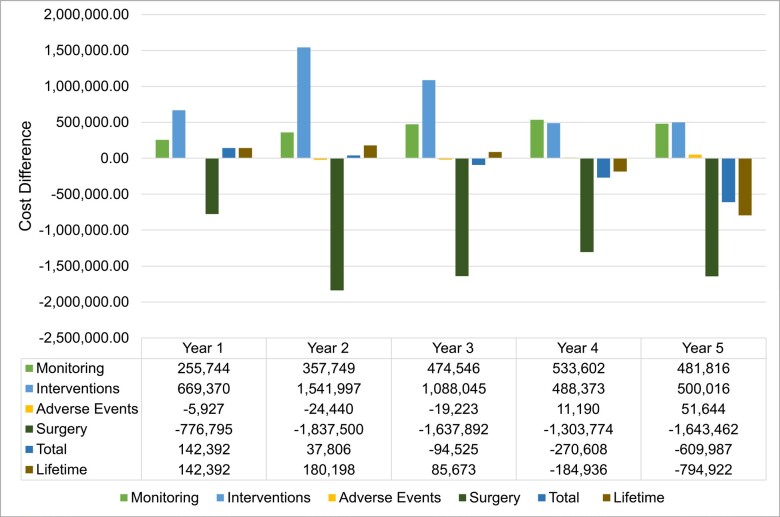

Overall, VCE implementation incurred higher annual costs until the second year; the trend reversed from year 3, leading to cost savings from year 4 (Figure 2). A shifting balance between reduced surgery costs and increased monitoring and intervention costs drives this progression. Adverse event cost contribution is negligible.

Figure 2. Cost Difference Breakdown by Year of Implementing VCE vs SOC.

Cost differences per groups (monitoring, interventions, adverse events, surgery) adding up to the total cost difference per year as well as accumulating cost differences over the 5-year time horizon.

Sensitivity analysis: Multiparameter sensitivity analysis was performed by comparing the base case and VCE scenario. A median saving of €80 (95% CI: -1148 to 1284) per patient per year is achieved using VCE (55.1% of simulated patients returned cost savings). Results from the one-way sensitivity analysis (Figure S1), showed that the total cost differential between the SOC and VCE was primarily influenced by the costs associated with surgery and the VCE procedure itself. Alterations in the expenses related to medication and fistula repair also resulted in significant fluctuations in the cost difference. In contrast, costs associated with ileoscopy (ILE), magnetic resonance enterography (MRE), computed tomography (CT), and other complications had a minor effect on the overall cost difference. The influence of other factors not depicted in the figure was negligible.

Real-World Validation

Analysis flow: Out of 300 patient records, 276 were retained after applying the selection criteria. Each record was replicated 100 times to generate the 27 600-patient simulated set (Figure S2).

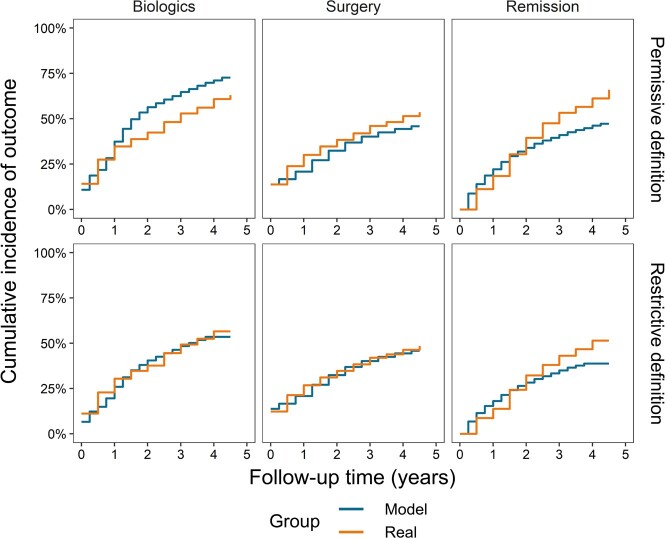

Cumulative incidence of outcomes: The first occurrence of an outcome was evaluated using permissive and restrictive definitions (Table S4). Overall, predictions align with real-world data (Figure 3), but for remission, which is overpredicted for up to 1.5-2.0 years and underpredicted afterward. However, the real data show larger changes over single intervals.

Figure 3. Cumulative Incidence of Outcomes by Permissive and Restrictive Definitions.

Top row: Permissive definition of outcomes, which includes any 6-month period of biologic use, all types of surgeries, and remission lasting any 6 months with no symptoms (CDAI ≤150) preceded by a period with mild, moderate, or severe symptoms (CDAI >150).

Bottom row: Restrictive definition of outcomes, which includes a period of biologic use of at least 1 year, only elective and emergency surgeries, and remission lasting at least 1 year with no symptoms (CDAI ≤150).

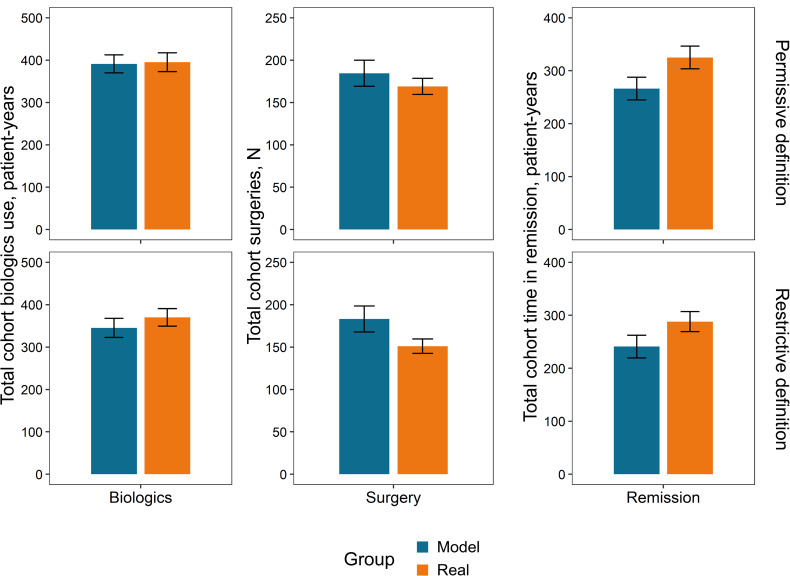

Outcome totals over the follow-up period: The disease burden over the follow-up period can be quantified as the aggregate resource utilization (biologics and surgery) and course of disease (duration of remission). Figure 4 compares cumulative outcomes between the real-world and the simulated sets of patients under permissive or restrictive conditions.

Figure 4. Model vs Real Outcome Totals Across Cohorts Over the Follow-Up Period.

Outcome totals over the 4.5-year follow-up period are shown according to a permissive definition (top) for biologics (any period of 6 months of use) and surgeries (all surgical procedures). The total time in remission was defined restrictively (bottom) as a minimum of 1-year duration for any period in remission.

Bayesian Validation

The model’s quantitative validation was based on the probabilities of a hypothetical decision maker accepting the model’s results as representative of the actual results,31 with a baseline acceptance rate of 50% (Table 2).

Table 2. Model Validity Results According to Bayesian Analysis.

| Outcome | Proximity | Permissive (95% CI) | Restrictive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biologics | True value | 80.4% (72.2%-87.5%) | 34.3% (25.5%-43.8%) |

| 5% | 99.0% (96.4%-100.0%) | 67.6% (58.3%-76.3%) | |

| 10% | 99.0% (96.4%-100.0%) | 87.3% (80.2%-93.0%) | |

| 20% | 99.0% (96.4%-100.0%) | 99.0% (96.4%-100.0%) | |

| Surgery | True value | 43.1% (33.7%-52.8%) | 5.9% (2.2%-11.2%) |

| 5% | 53.9% (44.2%-63.5%) | 14.7% (8.6%-22.2%) | |

| 10% | 73.5% (64.6%-81.6%) | 46.1% (36.5%-55.8%) | |

| 20% | 99.0% (96.4%-100.0%) | 64.7% (55.2%-73.6%) | |

| Remission | True value | 1.0% (0.0%-3.6%) | 1.0% (0.0%-3.6%) |

| 5% | 1.0% (0.0%-3.6%) | 1.0% (0.0%-3.6%) | |

| 10% | 1.0% (0.0%-3.6%) | 1.0% (0.0%-3.6%) | |

| 20% | 11.8% (6.3%-18.7%) | 20.6% (13.4%-28.9%) |

For each of the 3 outcomes, the results indicate the probability that a hypothetical decision maker would accept the model’s results as representative of reality according to the indicated parameters. The “true value” indicates that the model result falls within the uncertainty range of the real value. Other percentages indicate the degree of expansion (ie, the proximity of 10% means that the model value is within 10% of the real value, including its uncertainty range).

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

The model’s validity varied primarily based on the outcome and the employed definition. Under the permissive definition, the model reproduces empirical observation accurately in 80.4% of iterations (99% with more permissive proximity) while limiting to 66.7% and 87% accuracy at 5% and 10% proximity allowance under the stringent definition. The model is comparatively less efficient at predicting surgery under either permissive or restrictive criteria (Table S4), achieving satisfactory results only within a more permissive proximity range (73.5% at ≥10% proximity).

The model did not predict total time in remission according to either definition. Maximum validity values reached only 11.8% and 20.6% for permissive and restrictive values, respectively, when considering a threshold of coming within 20% of the real total time in remission.

DISCUSSION

A model for VCE in monitoring CD patients22,23 was adapted to Italian specifics and validated in its accuracy and generalizability. The model proved solid in capturing the complexities of CD, except for remission, a multifaceted and nuanced concept that poses significant challenges in clinical definition and modeling. This may be attributed to using the CDAI as the sole criterion for defining remission, which serves as a proxy for inflammatory activity and mucosal healing but does not fully describe the overall course of the disease. The scant empirical longitudinal data available on the evolution of CDAI further limits the model’s predictive accuracy of remission. Exploring larger and multicentric real-world data sets can offer potential avenues for enhancing the model’s predictive performance.

Analyzing the modeled outcomes revealed a steadier increment than the real-world data. This discrepancy may be attributed to the large number of model patients utilized to mitigate the effects of uncertainty in the model outcomes. In contrast, the limited real-world data set may have resulted in more significant fluctuations in cumulative incidence. Additionally, the dynamic nature of the clinical practice, which may involve treatment modifications not accounted for in the model, may have contributed to the observed difference. The model operates within a predetermined treatment framework based on diagnosed pathology and CDAI scores, while physicians may consider factors such as patient preferences and prior treatment history in their decision-making process.

The budget impact analysis appraised potential savings in the mid to long term at around €67 per patient per year, subject to significant uncertainty at sensitivity analysis. Also, the cost estimation presents a challenging interpretation due to the limited availability of data on hospital and healthcare resource utilization and costs in the patient sample analyzed. Nevertheless, the cost estimates are coherent with other European studies.32–34 The development of cost differences over time is consistent with previous studies investigating changes in patient management following diagnosis with VCE.35

In conclusion, the benefits to CD patients from the capability of VCE to provide a comprehensive assessment of the entire intestinal tract, thereby reducing the necessity for multiple examinations and improving mid- to long-term management, sum up economic considerations into the overall value proposition of the technology. The budget impact analysis indicates that implementing VCE monitoring in patients diagnosed with CD with small bowel involvement would likely increase healthcare expenditure in the first 2 years. However, cost savings are expected in the mid to long term within the specifics of Italian healthcare.

Limitations

The model is subject to limitations in its attempt to replicate clinical practice programmatically. It evolves through an idealized, predefined treatment framework, does not account for clinician discretionary judgment or clinical inaccuracy, and may not adequately cover the full range of possible CD cases. The real-world validation itself can suffer from the relatively limited statistics of cases in the monocentric cohort of 276 patients, missing data points, or inconsistent data recorded over two decades. Furthermore, when considering shorter time horizons, the likelihood of agreement between model results and tangible outcomes increases, potentially increasing the certainty in actions taken based on model predictions. Future comprehensive analyses may investigate the additional challenges associated with predicting patient remission. However, despite these limitations, the agreement between the model and real-world results across multiple outcomes is unlikely to be solely attributed to chance.

Disclosures

R.S., J.D., and R.T.T. are Coreva Scientific GmbH & Co KG employees, which received consultancy fees from Covidien, now part of Medtronic, for executing, analyzing, and disseminating the work presented in this manuscript. C.C. and D.G. received compensation from Coreva Scientific.

Supplementary Material

References

- Behaviour of Crohn's disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Louis E, Collard A, Oger A F, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi F A, Belaiche J. Dec 1;2001 Gut. 49(6):777–782. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.6.777. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.6.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural disease course of Crohn’s disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population-based inception cohort: an Epi-IBD study. Burisch Johan, Kiudelis Gediminas, Kupcinskas Limas, Kievit Hendrika Adriana Linda, Andersen Karina Winther, Andersen Vibeke, Salupere Riina, Pedersen Natalia, Kjeldsen Jens, D’Incà Renata, Valpiani Daniela, Schwartz Doron, Odes Selwyn, Olsen Jóngerð, Nielsen Kári Rubek, Vegh Zsuzsanna, Lakatos Peter Laszlo, Toca Alina, Turcan Svetlana, Katsanos Konstantinos H, Christodoulou Dimitrios K, Fumery Mathurin, Gower-Rousseau Corinne, Zammit Stefania Chetcuti, Ellul Pierre, Eriksson Carl, Halfvarson Jonas, Magro Fernando Jose, Duricova Dana, Bortlik Martin, Fernandez Alberto, Hernández Vicent, Myers Sally, Sebastian Shaji, Oksanen Pia, Collin Pekka, Goldis Adrian, Misra Ravi, Arebi Naila, Kaimakliotis Ioannis P, Nikuina Inna, Belousova Elena, Brinar Marko, Cukovic-Cavka Silvija, Langholz Ebbe, Munkholm Pia. 2019Gut. 68(3):423–433. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315568. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. Maaser Christian, Sturm Andreas, Vavricka Stephan R, Kucharzik Torsten, Fiorino Gionata, Annese Vito, Calabrese Emma, Baumgart Daniel C, Bettenworth Dominik, Borralho Nunes Paula, Burisch Johan, Castiglione Fabiana, Eliakim Rami, Ellul Pierre, González-Lama Yago, Gordon Hannah, Halligan Steve, Katsanos Konstantinos, Kopylov Uri, Kotze Paulo G, Krustiņš Eduards, Laghi Andrea, Limdi Jimmy K, Rieder Florian, Rimola Jordi, Taylor Stuart A, Tolan Damian, van Rheenen Patrick, Verstockt Bram, Stoker Jaap, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR] 2019Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 13(2):144–164. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adaptive support ventilation for faster weaning in COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Kirakli C., Ozdemir I., Ucar Z. Z., Cimen P., Kepil S., Ozkan S. A. Mar 15;2011 European Respiratory Journal. 38(4):774–780. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081510. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic skipping of the distal terminal ileum in Crohn’s disease can lead to negative results from ileocolonoscopy. Samuel Sunil, Bruining David H., Loftus Edward V., Becker Brenda, Fletcher Joel G., Mandrekar Jayawant N., Zinsmeister Alan R., Sandborn William J. Nov;2012 Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 10(11):1253–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.026. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Performance of capsule endoscopy and cross-sectional techniques in detecting small bowel lesions in patients with Crohn’s disease. Calabrese Carlo, Diegoli Margherita, Dussias Nikolas, Salice Marco, Rizzello Fernando, Cappelli Alberta, Ricci Claudio, Gionchetti Paolo. Apr 1;2020 Crohn's & Colitis 360. 2(2) doi: 10.1093/crocol/otaa046. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otaa046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panenteric capsule endoscopy versus ileocolonoscopy plus magnetic resonance enterography in Crohn’s disease: a multicentre, prospective study. Bruining David Henry, Oliva Salvatore, Fleisher Mark R, Fischer Monika, Fletcher Joel G. Jun;2020 BMJ Open Gastroenterology. 7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000365. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance enterography for the assessment of small bowel lesions in Crohn’s disease. González-Suárez Begoña, Rodriguez Sonia, Ricart Elena, Ordás Ingrid, Rimola Jordi, Díaz-González Álvaro, Romero Cristina, de Miguel Cristina Rodríguez, Jáuregui Arantxa, Araujo Isis K, Ramirez Anna, Gallego Marta, Fernández-Esparrach Gloria, Ginés Ángels, Sendino Oriol, Llach Josep, Panés Julian. Mar 1;2018 Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 24(4):775–780. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx107. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capsule endoscopy is superior to small-bowel follow-through and equivalent to ileocolonoscopy in suspected Crohn’s disease. Leighton Jonathan A., Gralnek Ian M., Cohen Stanley A., Toth Ervin, Cave David R., Wolf Douglas C., Mullin Gerard E., Ketover Scott R., Legnani Peter E., Seidman Ernest G., Crowell Michael D., Bergwerk Ari J., Peled Ravit, Eliakim Rami. Apr;2014 Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 12(4):609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.028. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looking beyond symptom relief: evolution of mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. Iacucci Marietta, Ghosh Subrata. Mar;2011 Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 4(2):129–143. doi: 10.1177/1756283x11398930. doi: 10.1177/1756283x11398930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frøslie Kathrine Frey, Jahnsen Jørgen, Moum Bjørn A., Vatn Morten H. Gastroenterology. 2. Vol. 133. Elsevier BV; Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort; pp. 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative acceptability and perceived clinical utility of monitoring tools: a nationwide survey of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Buisson Anthony, Gonzalez Florent, Poullenot Florian, Nancey Stéphane, Sollellis Elisa, Fumery Mathurin, Pariente Benjamin, Flamant Mathurin, Trang-Poisson Caroline, Bonnaud Guillaume, Mathieu Stéphane, Thevenin Alain, Duruy Marc, Filippi Jérôme, Lʼhopital François, Luneau Fabrice, Michalet Véronique, Genès Julien, Achim Anca, Cruzille Emmanuelle, Bommelaer Gilles, Laharie David, Peyrin-Biroulet Laurent, Pereira Bruno, Nachury Maria, Bouguen Guillaume. Aug;2017 Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 23(8):1425–1433. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000001140. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000001140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: role in diagnosis, management, and treatment. Spiceland Clayton M, Lodhia Nilesh. Sep 21;2018 World Journal of Gastroenterology. 24(35):4014–4020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparing diagnostic yield of a novel pan-enteric video capsule endoscope with ileocolonoscopy in patients with active Crohn’s disease: a feasibility study. Leighton Jonathan A., Helper Debra J., Gralnek Ian M., Dotan Iris, Fernandez-Urien Ignacio, Lahat Adi, Malik Pramod, Mullin Gerard E., Rosa Bruno. Jan;2017 Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 85(1):196–205.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.009. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capsule endoscopy in Crohn's disease surveillance: a monocentric, retrospective analysis in Italy. Calabrese Carlo, Gelli Dania, Rizzello Fernando, Gionchetti Paolo, Torrejon Torres Rafael, Saunders Rhodri, Davis Jason. Nov 28;2022 Frontiers in Medical Technology. 4:1038087. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2022.1038087. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2022.1038087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative colon cancer screening strategies in the context of the French national screening program. Barré Stéphanie, Leleu Henri, Benamouzig R., Saurin Jean-Christophe, Vimont Alexandre, Taleb Sabrine, De Bels Frédéric. Jan;2020 Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 13:1756284820953364. doi: 10.1177/1756284820953364. doi: 10.1177/1756284820953364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost effectiveness and projected national impact of colorectal cancer screening in France. Hassan C., Benamouzig R., Spada C., Ponchon T., Zullo A., Saurin J., Costamagna G. May 27;2011 Endoscopy. 43(9):780–793. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256409. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effectiveness of capsule endoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer. Hassan C., Zullo A., Winn S., Morini S. Feb 27;2008 Endoscopy. 40(5):414–421. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995565. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparing the cost-effectiveness of innovative colorectal cancer screening tests. Peterse Elisabeth F P, Meester Reinier G S, Jonge Lucie de, Omidvari Amir-Houshang, Alarid-Escudero Fernando, Knudsen Amy B, Zauber Ann G, Lansdorp-Vogelaar Iris. 2021JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 113(2):154–161. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa103. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Pennazio Marco, Spada Cristiano, Eliakim Rami, Keuchel Martin, May Andrea, Mulder Chris, Rondonotti Emanuele, Adler Samuel, Albert Joerg, Baltes Peter, Barbaro Federico, Cellier Christophe, Charton Jean, Delvaux Michel, Despott Edward, Domagk Dirk, Klein Amir, McAlindon Mark, Rosa Bruno, Rowse Georgina, Sanders David, Saurin Jean, Sidhu Reena, Dumonceau Jean-Marc, Hassan Cesare, Gralnek Ian. Mar 31;2015 Endoscopy. 47(4):352–386. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391855. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder Writaja, Laskaratos Faidon-Marios, El-Mileik Hanan, Coda Sergio, Fox Stevan, Banerjee Saswata, Epstein Owen. Diagnostics. 1. Vol. 12. MDPI AG; Review: colon capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease; p. 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating the clinical and economic consequences of using video capsule endoscopy to monitor Crohn’s disease. Saunders Rhodri, Torrejon Torres Rafael, Kosinski Lawrence. Aug;2019 Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 12:375–384. doi: 10.2147/ceg.s198958. doi: 10.2147/ceg.s198958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economic analysis of the adoption of capsule endoscopy within the British NHS. Lobo Alan, Torrejon Torres Rafael, McAlindon Mark, Panter Simon, Leonard Catherine, van Lent Nancy, Saunders Rhodri. May 12;2020 International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 32(5):332–341. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa039. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy David M., Hollingworth William, Caro J. Jaime, Tsevat Joel, McDonald Kathryn M., Wong John B. Medical Decision Making. 5. Vol. 32. SAGE Publications; Model transparency and validation: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-7; pp. 733–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Medical Treatment. Torres Joana, Bonovas Stefanos, Doherty Glen, Kucharzik Torsten, Gisbert Javier P, Raine Tim, Adamina Michel, Armuzzi Alessandro, Bachmann Oliver, Bager Palle, Biancone Livia, Bokemeyer Bernd, Bossuyt Peter, Burisch Johan, Collins Paul, El-Hussuna Alaa, Ellul Pierre, Frei-Lanter Cornelia, Furfaro Federica, Gingert Christian, Gionchetti Paolo, Gomollon Fernando, González-Lorenzo Marien, Gordon Hannah, Hlavaty Tibor, Juillerat Pascal, Katsanos Konstantinos, Kopylov Uri, Krustins Eduards, Lytras Theodore, Maaser Christian, Magro Fernando, Kenneth Marshall John, Myrelid Pär, Pellino Gianluca, Rosa Isadora, Sabino Joao, Savarino Edoardo, Spinelli Antonino, Stassen Laurents, Uzzan Mathieu, Vavricka Stephan, Verstockt Bram, Warusavitarne Janindra, Zmora Oded, Fiorino Gionata. 2020Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 14(1):4–22. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. Gomollón Fernando, Dignass Axel, Annese Vito, Tilg Herbert, Van Assche Gert, Lindsay James O., Peyrin-Biroulet Laurent, Cullen Garret J., Daperno Marco, Kucharzik Torsten, Rieder Florian, Almer Sven, Armuzzi Alessandro, Harbord Marcus, Langhorst Jost, Sans Miquel, Chowers Yehuda, Fiorino Gionata, Juillerat Pascal, Mantzaris Gerassimos J., Rizzello Fernando, Vavricka Stephan, Gionchetti Paolo, on behalf of ECCO 2017Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 11(1):3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. Gionchetti Paolo, Dignass Axel, Danese Silvio, Magro Dias Fernando José, Rogler Gerhard, Lakatos Péter Laszlo, Adamina Michel, Ardizzone Sandro, Buskens Christianne J., Sebastian Shaji, Laureti Silvio, Sampietro Gianluca M., Vucelic Boris, van der Woude C. Janneke, Barreiro-de Acosta Manuel, Maaser Christian, Portela Francisco, Vavricka Stephan R., Gomollón Fernando, on behalf of ECCO 2017Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 11(2):135–149. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw169. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portale Sanità Regione del Veneto - Stato. [2023-9-19]. https://salute.regione.veneto.it/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=81cf27ba-b06d-4806-9fb2-74e9dac832bf=988333

- Regione Emilia Romagna PRESTAZIONI DI ASSISTENZA SPECIALISTICA AMBULATORIALE, ottobre 2022. [2023-9-19]. https://salute.regione.emilia-romagna.it/ssr/strumenti-e-informazioni/nomenclatore-tariffario-rer/ottobre-2022

- Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Sullivan Sean D., Mauskopf Josephine A., Augustovski Federico, Jaime Caro J., Lee Karen M., Minchin Mark, Orlewska Ewa, Penna Pete, Rodriguez Barrios Jose-Manuel, Shau Wen-Yi. Jan;2014 Value in Health. 17(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A new statistical method to determine the degree of validity of health economic model outcomes against empirical data. Corro Ramos Isaac, van Voorn George A.K., Vemer Pepijn, Feenstra Talitha L., Al Maiwenn J. Sep;2017 Value in Health. 20(8):1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.016. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effectiveness analysis of top-down versus step-up strategies in patients with newly diagnosed active luminal Crohn’s disease. Marchetti Monia, Liberato Nicola L., Di Sabatino Antonio, Corazza Gino R. 2013The European Journal of Health Economics. 14(6):853–861. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0430-7. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casellas F., Panés J., García-Sánchez V., Ginard D., Gomollón F., Hinojosa J., Marín-Jiménez I., Barreiro M., Bastida G., Lindner Leandro, Giménez E., Vieta A. PharmacoEconomics Spanish Research Articles. 1. Vol. 7. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; Costes médicos directos de la enfermedad de Crohn en España; pp. 38–46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh Nivedita, Premchand Purushothaman. Frontline Gastroenterology. 3. Vol. 6. BMJ; A UK cost of care model for inflammatory bowel disease; pp. 169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small bowel capsule endoscopy in the management of established Crohn’s disease: clinical impact, safety, and correlation with inflammatory biomarkers. Kopylov Uri, Nemeth Artur, Koulaouzidis Anastasios, Makins Richard, Wild Gary, Afif Waqqas, Bitton Alain, Johansson Gabriele Wurm, Bessissow Talat, Eliakim Rami, Toth Ervin, Seidman Ernest G. Jan;2015 Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 21(1):93–100. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000255. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.