Abstract

High levels of uncompensated care impact hospital profitability and may create challenges for rural hospitals at financial risk of closure. We explore 2019 hospital uncompensated care as a percentage of operating expenses and draw comparisons at a state level by Medicaid expansion status and rural classification. We further compare uncompensated care in 2019 to 2014 in rural hospitals by Medicaid expansion implementation timing. We found that, overall, rural hospitals had more uncompensated care than urban hospitals in 2019 (3.81% vs. 3.12%), but there was a larger difference by expansion status (expansion states: 2.55% vs. non-expansion states: 6.28%). In all but seven states, rural hospitals reported higher uncompensated care than urban, and the 14 states with the highest uncompensated care had not expanded Medicaid. We observed that rural hospital uncompensated care in non-expansion states increased between 2014 and 2019, while the most dramatic decrease occurred in late-expansion states.

Keywords: uncompensated care, rural health, Medicaid expansion, uninsured, hospitals

Introduction

Rural residents have lower incomes and are more likely to be publicly insured or uninsured compared to urban residents (Cheeseman Day, 2019; Hawryluk, 2020; Newkirk & Damico, 2014). The payer mix of rural hospitals contributes to their uncompensated care burden as low-income uninsured or underinsured patients struggle to pay out-of-pocket costs (Coughlin et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2021). Uncompensated care are services provided that are never reimbursed and include both anticipated charity care and unanticipated bad debt (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], n.d.; Garcia et al., 2018). Costs from unreimbursed care reduce operating margins and contribute to hospital closures that negatively impact rural communities (Holmes et al., 2006; McCarthy et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2021). Since 2010, 153 rural hospitals have closed, leaving many communities with longer travel times and fewer options for care (McCarthy et al., 2021; North Carolina Rural Health Research Program [NCRHRP], 2023).

Total uncompensated care decreased between 2014 and 2019, and recent studies have suggested there is a relationship between uncompensated care and Medicaid expansion (Ammula & Guth, 2023; Dranove et al., 2016). We endeavor to understand that relationship in reference to rural hospitals. This analysis compares the 2019 median uncompensated care of rural and urban hospitals by State (Medicaid expansion implemented and not implemented) and then explores changes in median uncompensated care for rural hospitals between 2019 and 2014, after the Affordable Care Act was implemented.

New Contribution

This study provides new information about uncompensated care reported by rural and urban hospitals, and how it differs between States that have and have not expanded Medicaid. We describe the differential uncompensated care burden on rural and urban hospitals at the State level, and the change in uncompensated care for rural hospitals by the timing of Medicaid expansion. The study increases our understanding of the differential rural-urban burden of uncompensated care, and how that burden has evolved since the expansion of Medicaid.

Study Data and Methods

In this study, we use 2014 and 2019 uncompensated care and operating expense data from the Health Care Cost Report Information System (HCRIS) Medicare Cost Report for all general acute care hospitals that are non-Indian Health Service and non-Veteran’s Affairs facilities. Cost report end dates were used to designate cost report year, meaning that cost reports with end dates falling in 2014 and 2019 are included in the analysis of those respective study years. Uncompensated care is defined as the cost of charity care (Worksheet S-10 line 23) plus non-Medicare and non-Reimbursable Medicare Bad Debt expense (Worksheet S-10 line 29).1,2 It is expressed as a percentage of operating expense (Worksheet G-3 line 4) and denoted as “uncompensated care” hereafter. Hospitals were excluded if they had a reporting period of less than 360 days, if uncompensated care was less than or equal to zero or missing, if operating expenses were negative, or if uncompensated care as a percentage of operating expense was greater than 70%. A total of 174 Medicare cost reports were excluded from the analysis across 2014 and 2019.

Rural status was assigned across all study years using the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy’s (FORHP, 2022) FY 2021 definition. 3 Medicaid expansion implementation date was determined using Kaiser Family Foundation (2023) tracking data. Medicaid expansion states are defined as those that implemented expansion by December 31, 2017, in Exhibits 1 and 2. We further divide states in Exhibits 3 and 4 into: (a) those that implemented Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014, (b) those that implemented expansion between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2017, and (c) those that had not implemented expansion by December 31, 2017. Table 1 shows the final number of 2014 and 2019 Medicare cost reports for rural and urban hospitals by Medicaid expansion status. 4

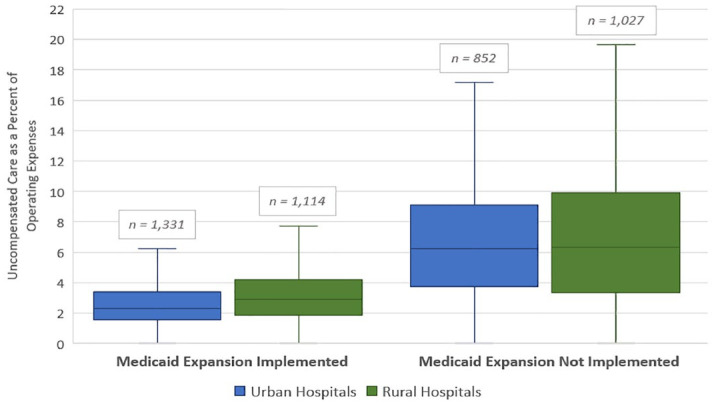

Exhibit 1.

Distribution of 2019 Uncompensated Care for Rural and Urban Hospitals by Medicaid Expansion Status.

Source. Authors’ analysis of 2019 Medicare Cost Report data, retrieved from Health Care Cost Report Information System.

Note. This boxplot displays the distribution of 2019 hospital uncompensated care as a percentage of operating expenses. Whiskers extend to 1.5× above or below the interquartile range.

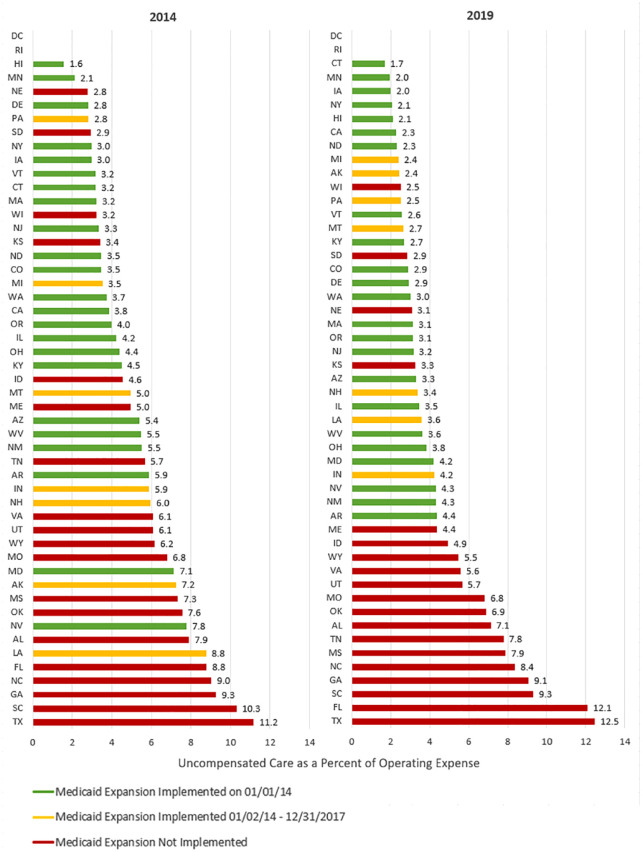

Exhibit 2.

Median 2019 Uncompensated Care for Rural and Urban Hospitals by State and Expansion Status.

Source. Authors’ analysis of 2019 Medicare cost report data, retrieved from Health Care Cost Report Information System.

Note. States are ordered from lowest to highest rural uncompensated care as a percentage of operating expenses within the expansion category. DC and RI do not have any rural hospitals.

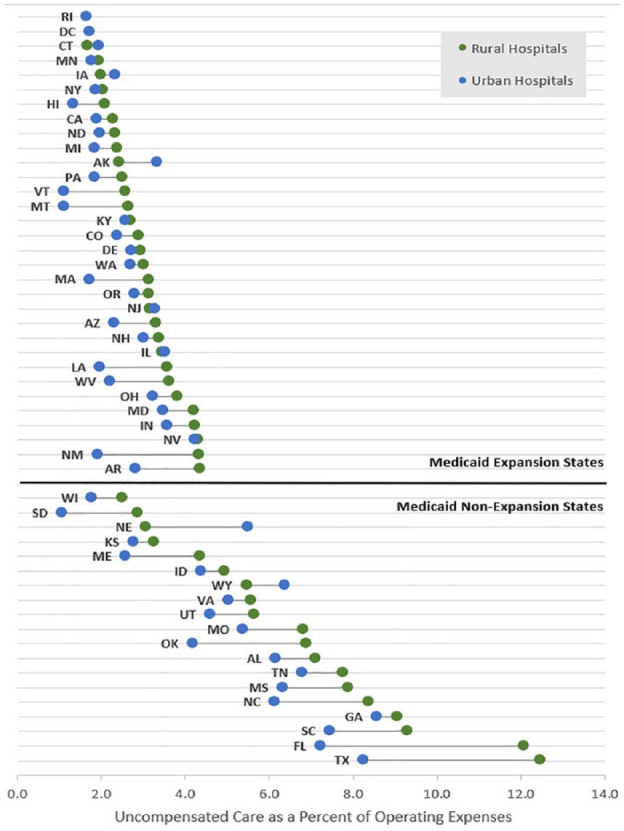

Exhibit 3.

State Median 2014 and 2019 Uncompensated Care for Rural Hospitals by Medicaid Expansion Status.

Source. Authors’ analysis of 2014 and 2019 Medicare cost report data, retrieved from Health Care Cost Report Information System.

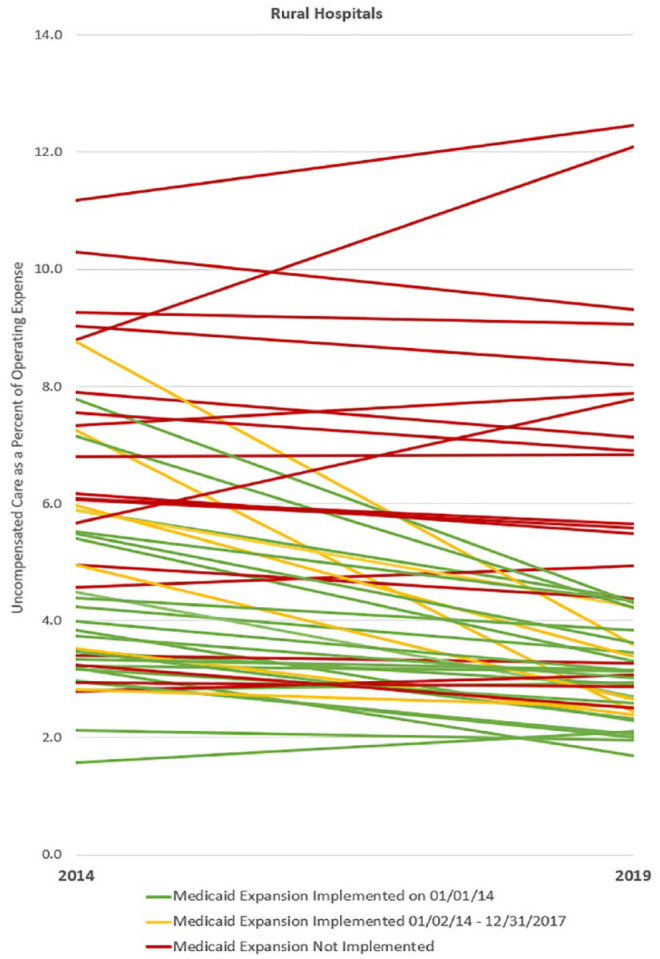

Exhibit 4.

State Median Uncompensated Care for Rural Hospitals by Medicaid Expansion Status from 2014 to 2019.

Source. Authors’ analysis of 2014 and 2019 Medicare cost report data, retrieved from Health Care Cost Report Information System.

Note. Table 2 displays median uncompensated care as a percentage of operating expenses for rural hospitals.

Table 1.

Number of 2014 and 2019 Medicare Cost Reports for all Rural and Urban Hospitals by Medicaid Expansion Status.

| Medicaid expansion status | No. of states and DC | No. of rural hospital cost reports | No. of urban hospital cost reports | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2019 | 2014 | 2019 | ||

| Implemented on 1/1/14 | 25 | 835 | 823 | 1,048 | 1,022 |

| Implemented 1/2/14 to 12/31/17 | 7 | 285 | 291 | 325 | 309 |

| Not implemented | 19 | 1,087 | 1,027 | 852 | 852 |

| Total | 51 | 2,207 | 2,141 | 2,225 | 2,183 |

Table 2.

State Median Uncompensated Care for Rural Hospitals by Medicaid Expansion Status from 2014 to 2019.

| State Medicaid expansion | Rural hospitals | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2019 | p-Value | |

| Implemented on 01/01/14 | 3.79% | 2.84% | <.001 |

| Implemented 01/02/14 to 12/31/17 | 4.79% | 2.98% | <.001 |

| Not implemented | 6.25% | 6.31% | 0.839 |

Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine if there was a significant difference between rural and urban median uncompensated care by the State in 2019. Additional Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine if 2014 and 2019 median uncompensated care differed significantly for each of the three expansion groups.

Study Results

Exhibit 1 shows that urban hospitals in Medicaid expansion states had the lowest median uncompensated care in 2019 (2.28%), followed by rural hospitals in Medicaid expansion states (2.88%), urban hospitals in non-expansion states (6.23%), and rural hospitals in non-expansion states (6.31%). In total, rural hospitals had higher 2019 median uncompensated care compared to urban hospitals (3.81% compared to 3.12%, not shown), and hospitals located in Medicaid non-expansion states had higher 2019 median uncompensated care compared to hospitals in expansion states (6.28% compared to 2.55%, not shown).

Exhibit 2 shows that rural hospitals had higher 2019 median uncompensated care in 42 states; the difference was statistically significant in 21 of those states (p < .05, not shown). State medians for rural hospitals ranged from 1.69% (CT) to 12.46% (TX) while medians for urban hospitals ranged from 1.07% (SD) to 8.57% (GA). The 14 states with the highest median uncompensated care were non-expansion states for both rural and urban hospitals. Eight of the 10 states with the largest difference between rural and urban median uncompensated care were non-expansion (from largest difference to smallest: FL, TX, OK, NE, NM, NC, SC, SD, ME, LA).

Exhibit 3 includes rural hospitals only and indicates that uncompensated care varies by when expansion was implemented. Exhibit 3 shows that states with the highest 2014 median uncompensated care are primarily non-expansion states (red bars) and that proportion is even higher in 2019. Exhibit 4 shows, in general, relatively steep declines in uncompensated care for states that expanded between February 1, 2014 and December 31, 2017 (yellow lines), gentle declines for states that expanded on January 1, 2014 (green lines), and a mix of slightly decreasing and steep increases for non-expansion states (red lines). Between 2014 and 2019, median uncompensated care among rural hospitals slightly increased in non-expansion states (6.25%-6.31%, p = .869, not significant), decreased significantly in states that expanded on January 1, 2014 (3.79%-2.84% p < .001), and in states that expanded between January 2, 2014 and December 31, 2017 (4.79%-2.98%, p < .001).

Discussion

Rural hospitals have more uncompensated care than urban hospitals, hospitals in non-expansion states have more uncompensated care than hospitals in expansion states, and uncompensated care is highest among hospitals that are rural AND in non-expansion states. Among rural hospitals, uncompensated care decreased the most in states that expanded between January 2, 2014 and December 31, 2017; it also decreased in states that expanded on January 1, 2014 but did not change in non-expansion states. 5

We cannot infer causation from this study because there are many factors that affect uncompensated care besides Medicaid expansion—payment rates, provider taxes, and uninsurance rates, for example. However, this study suggests that lower uncompensated care is associated with Medicaid expansion, particularly among rural hospitals. Other studies have also found that uncompensated care is higher in Medicaid non-expansion states, but the differential impact on rural hospitals has been under-researched post-2014 (Blavin & Ramos, 2021; Reiter et al., 2015). Our findings may relate to the fact that rural hospitals often serve lower-income populations that are less likely to have health insurance, particularly in non-expansion states, and more likely to struggle to pay health care costs (Garcia et al., 2018; Newkirk & Damico, 2014).

Rural hospital financial health is a critical issue, with a record 18 and 19 hospitals having closed in 2019 and 2020 alone. The disproportionate burden of uncompensated care on rural hospitals is worrying given the financial vulnerability of small rural hospitals and the negative impact of closures on community outcomes. Further research on which hospitals are most at risk would be prudent; financial health and reimbursement differences exist across rural hospitals, particularly between critical access hospitals and prospective payment hospitals. Understanding the relationship between uncompensated care, Medicaid expansion, and rural hospital financial health will allow us to better inform policies that may impact rural health access and economies.

Conclusions

We found that rural hospitals have higher uncompensated care, with the largest burden on those located in non-expansion states. Our findings suggest that the interaction of uncompensated care and Medicaid expansion is a relevant factor in addressing rural hospital closures and community health (McCarthy et al., 2021; NCRHRP, 2023).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement # U1CRH03714. The information, conclusions, and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors, and no endorsement by FORHP, HRSA, HHS, or The University of North Carolina is intended or should be inferred. We would also like to acknowledge H. Ann Howard with the Sheps Center for providing cost report data files from the Hospital Cost Report Information System.

Appendix.

2019 Number of Rural and Urban Hospitals by State and Expansion Status.

| State | Medicaid expansion | No. of hospitals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | ||

| AK | Implemented 9/1/2015 | 3 | 11 |

| AL | Not implemented | 35 | 50 |

| AR | Implemented 01/01/14 | 24 | 44 |

| AZ | Implemented 01/01/14 | 45 | 17 |

| CA | Implemented 01/01/14 | 229 | 54 |

| CO | Implemented 01/01/14 | 38 | 42 |

| CT | Implemented 01/01/14 | 24 | 3 |

| DC | Implemented 01/01/14 | 6 | |

| DE | Implemented 01/01/14 | 4 | 2 |

| FL | Not implemented | 152 | 24 |

| GA | Not implemented | 59 | 69 |

| HI | Implemented 01/01/14 | 9 | 12 |

| IA | Implemented 01/01/14 | 20 | 93 |

| ID | Not implemented | 11 | 29 |

| IL | Implemented 01/01/14 | 97 | 74 |

| IN | Implemented 2/1/2015 | 62 | 54 |

| KS | Not implemented | 21 | 105 |

| KY | Implemented 01/01/14 | 19 | 71 |

| LA | Implemented 7/1/2016 | 53 | 51 |

| MA | Implemented 01/01/14 | 53 | 5 |

| MD | Implemented 01/01/14 | 38 | 5 |

| ME | Not implemented | 7 | 20 |

| MI | Implemented 4/1/2014 | 66 | 63 |

| MN | Implemented 01/01/14 | 28 | 95 |

| MO | Not implemented | 44 | 57 |

| MS | Not implemented | 19 | 67 |

| MT | Implemented 1/1/2016 | 6 | 51 |

| NC | Not implemented | 48 | 48 |

| ND | Implemented 01/01/14 | 5 | 37 |

| NE | Not implemented | 15 | 70 |

| NH | Implemented 8/15/2014 | 8 | 17 |

| NJ | Implemented 01/01/14 | 61 | 1 |

| NM | Implemented 01/01/14 | 11 | 23 |

| NV | Implemented 01/01/14 | 22 | 13 |

| NY | Implemented 01/01/14 | 104 | 48 |

| OH | Implemented 01/01/14 | 85 | 69 |

| OK | Not implemented | 33 | 68 |

| OR | Implemented 01/01/14 | 26 | 33 |

| PA | Implemented 1/1/2015 | 111 | 44 |

| RI | Implemented 01/01/14 | 10 | |

| SC | Not implemented | 31 | 20 |

| SD | Not implemented | 9 | 45 |

| TN | Not implemented | 43 | 54 |

| TX | Not implemented | 200 | 155 |

| UT | Not Implemented | 24 | 21 |

| VA | Not implemented | 50 | 29 |

| VT | Implemented 01/01/14 | 1 | 13 |

| WA | Implemented 01/01/14 | 45 | 40 |

| WI | Not implemented | 48 | 73 |

| WV | Implemented 01/01/14 | 18 | 29 |

| WY | Not implemented | 3 | 23 |

Charity care and non-Medicare bad debt both contribute to uncompensated care costs; however, charity care costs are associated with services that the hospital offers free of charge to qualifying patients. Bad debt costs come from services for which the hospital charged but received no payment.

Worksheet S-10 was first included by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services in Medicare cost reports in 2010 to expand on the collection of uncompensated care information. See (CMS, 2023)

FORHP defines rural areas as (a) all non-metro counties, (b) all metro census tracts with RUCA codes 4-10, and (c) large metro census tracts of at least 400 sq. miles in area with a population density of 35 or less per sq. mile with RUCA codes 2-3. See (FORHP, 2022).

For 2014 cost reports, beginning dates ranged from January 1, 2013 to January 1, 2014. Thirty-nine percent of reports began on January 1, 2014, 32% began on July 1, 2013, and 17% on October 1, 2013. Cost reports for 2019 beginning dates ranged from January 1, 2018 to January 1, 2019. Thirty-nine percent began on January 1, 2019, 33% began on July 01, 2018, and 17% on October 1, 2018.

The date of cost report differs across hospitals and the reported effect of Medicaid expansion may vary with report timing within the year.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement # U1CRH03714.

ORCID iDs: Emmaline Keesee  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6430-4482

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6430-4482

Susie Gurzenda  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9210-3661

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9210-3661

References

- Ammula M., Guth M. (2023, January 18). What does the recent literature say about Medicaid expansion? economic impacts on providers. The Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-does-the-recent-literature-say-about-medicaid-expansion-economic-impacts-on-providers/

- Blavin F., Ramos C. (2021). Medicaid expansion: Effects on hospital finances and implications for hospitals facing COVID-19 challenges. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 40(1), 82–90. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). (2023, August 8). Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH). CMS.Gov. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/dsh

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). (n.d.). Uncompensated care. HealthCare.Gov. https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/uncompensated-care/

- Cheeseman Day J. (2019, April 9). Rates of uninsured fall in rural counties, remain higher than urban counties. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/04/health-insurance-rural-america.html [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin T. A., Samuel-Jakubos H., Garfield R. (2021, April 6). Sources of payment for uncompensated care for the uninsured. The Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/sources-of-payment-for-uncompensated-care-for-the-uninsured/

- Dranove D., Garthwaite C., Ody C. (2016). Uncompensated care decreased at hospitals in Medicaid expansion states but not at hospitals in nonexpansion states. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(8), 1471–1479. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. (2022, March). Defining rural population. Health Resources and Services Administration. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/what-is-rural

- Garcia K., Thompson K., Howard H., Pink G. (2018). Geographic variation in uncompensated care between rural and urban hospitals. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC-Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluk M. (2020, January 10). High-deductible plans Jeopardize financial health of patients and rural hospitals. KFF Health News. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/high-deductible-plans-jeopardize-financial-health-of-patients-and-rural-hospitals/

- Holmes G. M., Slifkin R. T., Randolph R. K., Poley S. (2006). The effect of rural hospital closures on community economic health. Health Services Research, 41(2), 467–485. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00497.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kaiser Family Foundation. (2023). Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- McCarthy S., Moore D., Smedley W. A., Crowley B. M., Stephens S. W., Griffin R. L., Tanner L. C., Jansen J. O. (2021). Impact of rural hospital closures on health-care access. The Journal of Surgical Research, 258, 170–178. 10.1016/j.jss.2020.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newkirk V., Damico A. (2014, May 29). The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage in rural areas. The Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-act-and-insurance-coverage-in-rural-areas/

- North Carolina Rural Health Research Program. (2023). Rural hospital closures. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/ [Google Scholar]

- Reiter K. L., Noles M., Pink G. H. (2015). Uncompensated care burden may mean financial vulnerability for rural hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(10), 1721–1729. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Thompson K., Knocke K., Pink G. (2021). Health system challenges for critical access hospitals: Findings from a national survey of CAH executives. North Carolina Rural Health Research Program. References. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/product/health-system-challenges-for-critical-access-hospitals-findings-from-a-national-survey-of-cah-executives/#:~:text=Three%20of%20the%20major%20challenges, medications%20and%20medication%20services%20has