Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effect of adipose-derived cells (ADCs) on tendon-bone healing in a rat model of chronic rotator cuff tear (RCT) with suprascapular nerve (SN) injury.

Methods

Adult rats underwent right shoulder surgery whereby the supraspinatus was detached, and SN injury was induced. ADCs were cultured from the animals’ abdominal fat. At 6 weeks post-surgery, the animals underwent surgical tendon repair; the ADC (+ve) group (n = 18) received an ADC injection, and the ADC (−ve) group (n = 18) received a saline injection. Shoulders were harvested at 10, 14, and 18 weeks and underwent histological, fluorescent, and biomechanical analyses.

Results

In the ADC (+ve) group, a firm enthesis, including dense mature fibrocartilage and well-aligned cells, were observed in the bone-tendon junction and fatty infiltration was less than in the ADC (−ve) group. Mean maximum stress and linear stiffness was greater in the ADC (+ve) compared with the ADC (−ve) group at 18 weeks.

Conclusion

ADC supplementation showed a positive effect on tendon-bone healing in a rat model of chronic RCT with accompanying SN injury. Therefore, ADC injection may possibly accelerate recovery in massive RCT injuries.

Keywords: Suprascapular nerve injury, bone-tendon interface healing, rotator cuff tear, adipose-derived cells, animal model

Introduction

Most patients experience acceptable clinical outcomes following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR). 1 However, ARCR for a chronic rotator cuff tear (RCT) remains challenging, and is associated with a high structural failure rate of between 34–94%. 2 It has been reported that recurrence rates of massive RCTs may be as high as 80% due to tendon retraction, muscle atrophy, fatty infiltration, and osteoporosis. 3 One study that reported recurrence rates of 53% (8/15 patients) found re-tears were more common in patients with preoperative fatty infiltration. 4 Indeed, studies involving massive RCTs with a high recurrence rate, have found a significant association between suprascapular nerve injury, muscle atrophy, and fatty infiltration.5,6 Moreover, one study found that all patients who had a massive RCT (n = 8) had suprascapular neuropathy in the supraspinatus (SSP) and/or infraspinatus (ISP) muscles, as shown by electromyography analysis. These findings suggest that suprascapular nerve injuries are commonly associated with massive RCTs. 7 Another study using freshly frozen cadavers, reported that the degree of rotator cuff muscle atrophy often observed after a massive tear may be explained by increased tension on the nerve due to muscle retraction. 8

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are commonly used in tissue engineering for the treatment of various diseases and they can be readily isolated from autologous tissues. 9 The safety and efficacy of an intra-tendinous injection of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) have been evaluated for the treatment of partial-thickness RCTs and no treatment-related adverse events were reported at the 2-year follow-up. 10 In a rodent model of chronic massive RCT, ADSCs were shown to provide more benefit in chronic tears as shown by improvements in bone morphometric parameters. 11 Moreover, ADSCs have become increasingly used due to their minimal damage, low cost, and ubiquity. Furthermore, they can be isolated from various tissues, including bone marrow, the umbilical cord, and the placenta. 12 In the field of rotator cuff surgery, studies have begun to evaluate the effects of ADSCs on rotator cuff regeneration. 13

As aforementioned, reports have shown that suprascapular nerve injury due to massive tears is closely associated with the development of fatty infiltration and/or muscle atrophy.5,6,14,15 We hypothesized that the administration of adipose-derived cells (ADCs) would reverse fatty infiltration and enhance tendon-bone healing. 16 To investigate this, we established a rodent model of chronic RCT with suprascapular nerve injury to mimic a clinical setting, and assessed the effects of ADC supplementation.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for Animal Research and was approved by the Animal Studies and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of our institution (#2020-134). It was also approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Animal Care Centre at our institute (#2021-118). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and minimize the suffering of all animals.

Animals

In total, 36 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats 10 weeks old with a mean ± SD body weight of 344 ± 19 g were separated into two groups: ADC (+ve) (n = 18) and ADC (−ve) (n = 18). Both groups underwent massive SSP detachment in the right shoulder, and the untreated left shoulder in the ADC (−ve) group was used as a control. All rats were treated according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of MSCs

Procedures for isolating and expanding ADCs have been reported elsewhere.16–18 During the surgical procedure for development of the rat model, abdominal fat was collected from the ADC (+ve) group and washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The fat was minced using scissors and subsequently placed in a 50-ml conical tube containing 40 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 0.075% collagenase type 1 (Wako, Osaka, Japan) and 2% penicillin/streptomycin. The fat was digested in a shaker for 1 h at 37°C, and the digest was passed through a 70-μm filter (BD Falcon, Oxford, UK). The solution was centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min, and the pellets were washed with PBS twice. The resulting pellet was resuspended and expanded in DMEM with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) in T300 tissue culture flasks at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Semi-confluent ADCs from passage 2 to 5 were used for subsequent experiments. Confluent ADCs were used for implantation, and the concentration used was 3.78 × 107 cells.

Surgical procedure

The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane at a high oxygen flow rate. A middle longitudinal skin incision was made, and the subcutaneous tissue was divided to expose the deltoid. After exposure of the SSP tendon, the tendon insertion was detached and resected using a #11 scalpel blade, and the cartilaginous portion was protected at its insertion. The suprascapular nerve was pinched by the vascular clip for 20 s (clipping power 120 g/mm2) just anterior to the suprascapular notch. At 6-weeks post index surgery, the detached SSP was repaired, using the modified Mason-Allen stitch with 3-0 polyester suture (Akiyama Medical Manufacturing). Briefly, a bone groove and two columned tunnels were made on the greater tuberosity, and the detached tendon was reattached to the groove, passing the suture through the bone tunnel.

After the deltoid muscle incision was closed, an ADC pellet (3.78 × 107 cells) in 200 μl of normal saline was injected at the repair site using an 18G needle. The wound was then closed at each layer, and the animals were allowed to move freely in their cages after the operation. The surgical protocol was similar to that described previously.19,20 To establish a chronic tendon tear, a thermo-setting polyurethane mouldable resin was placed between the tendon edge and the tendon footprint. suprascapular nerve injury was achieved by applying a vascular clip for 20 s (clipping power 120 g/mm2). 21

Six weeks post-surgery, the ADC (+ve) group underwent tendon repair treatment with ADC injection, and the ADC (−ve) group underwent tendon repair treatment with saline injection. At 10, 14, and 18 weeks post-surgery, specimens were harvested and subjected to histological analysis, immunofluorescent staining, and mechanical testing. Details of the study are summarized in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study time course. RCT, rotator cuff tear; SN, scapular nerve; ADC, adipose-derived cell; ADSC, adipose-derived stem cell.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the study design, illustrating how the rats were divided into groups for the three time points. SSP, supraspinatus; PO, postoperative; SN, suprascapular nerve; ADC, adipose-derived cell.

Histological analysis

As described previously, axial sections of 5-μm thickness at the muscle belly (SSP) were processed from frozen sections and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Oil Red O. 22 To observe fatty tissue, fixed specimens were frozen briefly with iced 99.5% ethanol and cut axially into 10-μm-thick sections. The specimens were visualized under a light microscope (BZ-X710; Keyence, Osaka, Japan), and photomicrographs were obtained.

Muscle atrophy was identified by a few suggestive findings, such as an angular rather than a round shape of muscle fibres, decreased distance between myonuclei, and centralization of myonuclei. Muscle fibre size was not measured.

Immunofluorescence staining

Fatty infiltration was identified using a perilipin method. 23 Accordingly, abdominal fat samples were fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. Sections were then stained with a guinea pig anti-perilipin antibody (Fitzgerald, MA, United States), followed by a goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Invitrogen, CA, United States). Sections were examined via fluorescence.

Mechanical testing at the tendon-bone insertion

The testing protocol was similar to that described previously.19,22 All biomechanical testing specimens were dissected, stored at −80°C, and thawed the day before testing. With the exception of the SSP tendon-humerus complex, soft tissues over the humerus were removed. The SSP tendon was secured to a screw grip using sandpaper and ethyl cyanoacrylate. Specimens in saline were subjected to micro-CT (R-mCT2; Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) on the day of testing. Each sample was placed in a holder and scanned at 90 kV and 160 μA. Following micro-CT scanning, the specimens were placed in a tensile testing machine (TENSILON RTE-1210; Orientec, Tokyo, Japan). The humerus was secured to a custom-designed pod using a capping compound. The SSP tendon-humerus complex was positioned to allow tensile loading in the longitudinal direction of the SSP tendon-humerus interface. The specimens were preloaded to 0.1 N for 5 min, followed by five cycles of loading and unloading at a cross-head speed of 5 mm/min. Samples were then loaded to failure at a rate of 1 mm/min, and mechanical properties were calculated. Failure modes were recorded for each specimen.

Linear stiffness was calculated by determining the slope of the linear portion of the load-elongation curve. Ultimate stress was calculated by dividing the ultimate load-to-failure by the cross-sectional area of the repaired tendon-bone interface, obtained from the axial section of the micro-computed tomography (CT) image. Young’s modulus was calculated by determining the slope of the linear portion of the stress-strain curve. Strain was calculated by dividing elongation with the initial length obtained from the coronal section of the micro-CT image.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP version 16 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons among groups were analysed using Mann–Whitney U test and the Holm–Bonferroni sequential correction method was used to adjust the P-values for the multiple comparisons.

Results

Histological observation of muscle belly and enthesis

In the ADC (+ve) group, muscle fibres were slightly atrophic, with regular nuclear arrangement. These changes were similar throughout the experimental period. By contrast, in the ADC (−ve) group, the muscle fibres showed more advanced atrophy with irregular nuclear arrangement, and the changes became more prominent over the experimental period (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Examples of histological findings (haematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×40) taken at 4, 8 and 12 weeks. ADC: adipose-derived cell.

Histology at the tendon-bone insertion

The tendon-bone junction was reconstructed using granulated tissue in both groups. A firm enthesis was observed in the ADC (+ve) group, and showed dense mature fibrocartilage and well-aligned cells. In the ADC (ve−) group, the enthesis had a relatively decreased cell density and immature fibrocartilage (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Examples of histological findings (haematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×40) taken at 4, 8 and 12 weeks. ADC: adipose-derived cell, T: tendon, B: bone, I: tendon-bone interface

Immunofluorescence staining

At 18 weeks, there was some fatty infiltration in the abdominal muscle sample in the ADC (−ve) group. By contrast, lower fatty infiltration was observed in the ADC (+ve) group and the control group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining of muscle belly from one animal taken at 18 weeks. The area indicated by the white arrow represents regions where fat is stained with perilipin staining. ADC: adipose-derived cell.

Biomechanical testing

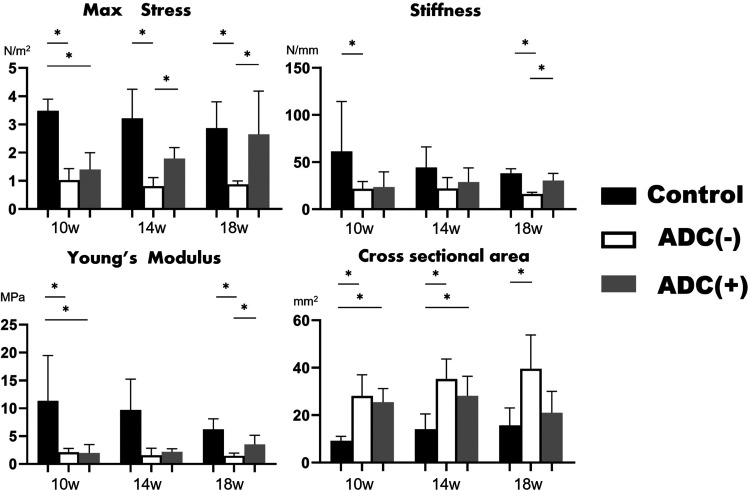

There was a significant difference in favour of the ADC (+ve) group compared with the ADC (−ve) group in maximum stress at both 14 and 18 weeks, in linear stiffness at 18 weeks and Young’s modulus at 18 weeks. There was no significant difference between these groups in cross-sectional area at all time points (Figure 6 and Table 1).

Figure 6.

The results of biomechanical testing. There were significant differences in favour of ADC (+ve) group compared with ADC (−ve) group, in mean maximum stress at 14 weeks and 18 weeks linear stiffness at 12 weeks and Youngs modulus at 18 weeks. *P < 0.05. ADC: adipose-derived cell.

Table 1.

Results of biomechanical testing in the rat model.

| Control(n = 18) | ADC (+ve)(n = 18) | ADC (−ve)(n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum stress, N/m2 | |||

| 10 weeks | 3.47 ± 0.42 | 1.40 ± 0.58 | 1.02 ± 0.40 |

| 14 weeks | 3.21 ± 1.03 | 1.79 ± 0.38* | 0.81 ± 0.30* |

| 18 weeks | 2.86 ± 0.93 | 2.6 ± 1.53* | 0.87 ± 0.12* |

| Linear stiffness, N/mm | |||

| 10 weeks | 61.3 ± 57.2 | 23.5 ± 16.0 | 21.5 ± 7.81 |

| 14 weeks | 44.2 ± 21.8 | 28.8 ± 15.0 | 22.0 ± 11.5 |

| 18 weeks | 38.0 ± 4.98 | 30.4 ± 7.53* | 16.0 ± 1.87* |

| Young’s modulus, MPa | |||

| 10 weeks | 11.3 ± 8.16 | 1.98 ± 1.51 | 2.11 ± 0.69 |

| 14 weeks | 7.21 ± 6.79 | 2.19 ± 0.56 | 1.56 ± 1.25 |

| 18 weeks | 5.93 ± 2.34 | 3.53 ± 1.61 | 1.48 ± 0.49* |

| Cross-sectional area, mm2 | |||

| 10 weeks | 9.20 ± 1.86 | 25.5 ± 5.79 | 28.1 ± 8.94 |

| 14 weeks | 14.0 ± 6.56 | 28.2 ± 8.20 | 35.2 ± 8.47 |

| 18 weeks | 15.7 ± 7.33 | 39.5 ± 14.2 | 21.0 ± 9.00 |

ADC: adipose-derived cell.

Comparison of ADC (+ve) and ADC (−ve) P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we used a rat model of chronic rotator cuff injury with an accompanying suprascapular nerve injury and examined the effects of ADC transplantation on enthesis repair. We focused on the reparative effects of ADCs, a type of MSC, on tendon-bone healing and fatty degradation. It has been suggested that exosomes, which are extracellular vesicles released by MSCs, enhance rotator cuff healing. 24 Unlike the broad-range, trophic effects of MSCs, exosomes provide a more targeted approach, delivering specific proteins, lipids, and RNAs that influence cell behaviour and promote healing. 24 While MSCs and exosomes support tissue repair, MSCs offer a more comprehensive regenerative potential by directly participating in tissue repair and modulating the immune response. 25 Our results suggest that ADCs, due to their MSC characteristics enhance tendon-bone healing and may possibly exert these effects through the secretion of exosomes, although this hypothesis requires further investigation.

Compared with other stem cell sources, adipose tissue has useful advantages because of its accessibility, abundance, and less painful collection procedure. In addition, MSCs can be maintained and expanded in tissue cultures for long periods without losing differentiation capacity, so providing large cell quantities. 26 A systematic review of 45 studies reported on the therapeutic advantages of ADSCs compared with bone marrow and umbilical cord-derived MSCs and concluded that ADSCs appeared to be the most suitable and promising MSCs for the recovery of peripheral nerve lesions. 12 Indeed, ADSCs have shown significant chondrogenic potential for use in tissue engineering. 27 These cells are now widely accepted for use in bone and cartilage regeneration and repair. Importantly, we found that in a rat model of chronic RCT with suprascapular nerve injury, ADSC transplantation improved tendon-bone healing, as well as fatty degradation and atrophy in the involved muscles. This led to enhanced biomechanical properties and granulation maturity at the repair site. To our knowledge, this is the first study to observe such findings.

Interestingly, in a study that used SSP transection and intramuscular botulinum toxin injection in a rat model of chronic massive RCTs, researchers found no added benefit of supplementing ADSCs with transforming growth factor-β3 (TGF-β3). 17 However, in a rabbit model of chronic RCT, where six weeks post-surgery, researchers used ADSCs alone, ADSCs plus repair, saline plus repair or saline alone for six weeks, no significant difference was seen among groups. The investigators suggested that the absence of effect with ADSCs in their study may be related to the observation time point. 28 In our study, the effects of ADCs on enthesis were obvious at eight weeks and longer. Therefore, perhaps long observational periods are required to confirm the effect of ADC supplementation on enthesis in chronic RCT models.

Interestingly, previous studies have failed to confirm the advantage of using scaffolds in chronic cuff repair models. For example, one study, in a rat chronic RCT injury model, compared the effects of ADSCs (4 × 106 cells) with and without use of scaffold (i.e., tendon hydrogel) on tendon healing, and found no biomechanical advantage. 29 Another study in a rabbit model, evaluated the efficacy of MSCs (1M cells) with a 3-dimensional (D) bio-printed scaffold and found that there was no significant difference in gross tear size between animals with and without the scaffold. 30 In a dose-escalation clinical trial in patients, another study found that the amount of ADSCs administered was an important factor in regenerating the rotator cuff and that intra-tendinous ADSC injection without scaffolds reduced shoulder pain by approximately 90% and muscle strength increased by >50%. 10 Shoulder function, measured using three common assessments scores, improved in all dose groups. Moreover, structural outcomes evaluated using MRI showed that the volume of bursal-sided defects in the high-dose group decreased by 90% six months after injection.

In our present study, ADCs were directly injected into the joint at 2–40 times the concentration of previous reports using MSCs with scaffolds.17,30,31 Moreover, they were injected after the deltoid suture to reduce outflow loss. Consequently, in terms of biomechanical testing and histological aspects, we observed better results in the ADC (+ve) group than in the ADC (−ve) group. Nevertheless, although we found positive effects of ADC injection without a scaffold in a rat chronic RCT injury model, other reports have observed a high initial cell loss (approximately 75%) over 24 h following MSC injection without a scaffold. 32 The resolution of the scaffold issue remains to be elucidated in future studies.

The condition of the rotator cuff parenchyma, enthesis, and suprascapular nerve, are major factors influencing postoperative prognosis of RCT repairs. Specifically, impaired condition of the suprascapular nerve will compromise the rotator cuff enthesis structure. In a rodent model with suprascapular nerve transection, one study demonstrated that suprascapular nerve injury impaired the enthesis by reducing cellularity and diminished the collagen bundle in the tendon zones. 15 Another study, also in a rodent model, evaluated the histomorphology of the fibrocartilage area of bone-tendon junction formation and reported that there was less cellularity and cell maturity in the group with suprascapular nerve transection. 14 We found that regenerated enthesis with suprascapular nerve injury was relatively more mature in the ADC (+ve) group compared with the ADC (−ve) group, with significant improvements in both biomechanical and histological parameters. We suggest that ADCs promote enthesis healing and transmission of suitable biomechanical stimulation via the healed enthesis secondarily results in recovery of the damaged nerve and muscles. An alternate hypothesis is that, ADCs lead to enthesis healing, and extra-articular recruitment of ADCs to the suprascapular nerve simultaneously improves the damaged nerve. The exact mechanism by which ADCs lead to improvements in enthesis repair following suprascapular nerve injury is the subject of ongoing research in our laboratory.

Other studies investigating the role of ADSCs in chronic RCT healing have found that beyond facilitating tendon-bone healing, ADCs may play a significant role in preventing muscle atrophy, a critical concern in RCT management. 33 Our findings corroborate these previous observations, underscoring the therapeutic utility of ADCs in both tendon-bone integration and the attenuation of muscle atrophy, thereby offering a comprehensive approach in the treatment of chronic RCTs.

Our study had some limitations. Firstly, the anatomy and function of the rat shoulder differs from the human shoulder. In particular, the acromial arch in quadrupedal animals is different because it involves reduced coverage of the subscapularis compared with bipedal animals. 34 Secondly, ADCs were not labelled which would have permitted analysis of cell retention at the healing site over time. In addition, their differentiation potential was not verified. However, in studies where similar methods for creating ADCs were employed, the cells were shown to possess stem cell-like differentiation capabilities. Thirdly, because of the small number of specimens, we did not evaluate histopathological scoring systems, muscle atrophy or fatty infiltration. Finally, relatively small number of samples were used which impacts the generalizability of our findings and so a cautious interpretation of our results is warranted.

In conclusion, we evaluated the effect of ADCs on the repair site in a rat chronic RCT model with suprascapular nerve injury. The ADC (+ve) group exhibited better results than the ADC (−ve) group in terms of mechanical and histological parameters. In addition, in ADC (+ve) group, the repaired enthesis had better fibrocartilage maturity with increased cell density, and muscle fibres showed less atrophy compared with the ADC (−ve) group. Therefore, ADC supplementation had a positive effect on tendon-bone healing in a model of chronic RCT injury with accompanying suprascapular nerve injury. Further studies are required to confirm our results.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the grant from Aid in Scientific Research [grant number 18K09125].

ORCID iD: Hiroki Ohzono https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7170-5401

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McElvany MD, McGoldrick E, Gee AO, et al. Rotator cuff repair: published evidence on factors associated with repair integrity and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, et al. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86: 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ladermann A, Denard PJ, Collin P. Massive rotator cuff tears: definition and treatment. Int Orthop 2015; 39: 2403–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi S, Kim MK, Kim GM, et al. Factors associated with clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with a suture bridge technique in medium, large, and massive tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 1675–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki Y, Ochiai N, Hashimoto E, et al. Relationship between neuropathy proximal to the suprascapular nerve and rotator cuff tear in a rodent model. J Orthop Sci 2018; 23: 414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Feeley BT, Kim HT, et al. Reversal of Fatty Infiltration After Suprascapular Nerve Compression Release Is Dependent on UCP1 Expression in Mice. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018; 476: 1665–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallon WJ, Wilson RJ, Basamania CJ. The association of suprascapular neuropathy with massive rotator cuff tears: a preliminary report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006; 15: 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albritton MJ, Graham RD, Richards RS, et al. An anatomic study of the effects on the suprascapular nerve due to retraction of the supraspinatus muscle after a rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Q, Liu R, Jiang J, et al. What is the impact of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on clinical treatment? Stem Cell Res Ther 2020; 11: 519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jo CH, Chai JW, Jeong EC, et al. Intratendinous Injection of Autologous Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Rotator Cuff Disease: A First-In-Human Trial. Stem Cells 2018; 36: 1441–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauyo T, Rothrauff BB, Chao T, et al. The Effect of Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Healing of Massive Chronic Rotator Cuff Tear in Rodent Model. Orthop J Sports Med 2017; 5(7 suppl6). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavorato A, Raimondo S, Boido M, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Treatment Perspectives in Peripheral Nerve Regeneration: Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernigou P, Flouzat Lachaniette CH, Delambre J, et al. Biologic augmentation of rotator cuff repair with mesenchymal stem cells during arthroscopy improves healing and prevents further tears: a case-controlled study. Int Orthop 2014; 38: 1811–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y, Wang C, Kwak JM, et al. Suprascapular nerve neuropathy leads to supraspinatus tendon degeneration. J Orthop Sci 2020; 25: 588–594.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gereli A, Uslu S, Okur B, et al. Effect of suprascapular nerve injury on rotator cuff enthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020; 29: 1584–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busser H, De Bruyn C, Urbain F, et al. Isolation of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells Without Enzymatic Treatment: Expansion, Phenotypical, and Functional Characterization. Stem Cells Dev 2014; 23: 2390–2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothrauff BB, Smith CA, Ferrer GA, et al. The effect of adipose-derived stem cells on enthesis healing after repair of acute and chronic massive rotator cuff tears in rats. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2019; 28: 654–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamada T, Matsubara H, Yoshida Y, et al. Autologous adipose-derived stem cell transplantation enhances healing of wound with exposed bone in a rat model. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0214106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanazawa T, Gotoh M, Ohta K, et al. Histomorphometric and ultrastructural analysis of the tendon-bone interface after rotator cuff repair in a rat model. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 33800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda H, Gotoh M, Kanazawa T, et al. Hyaluronic Acid Accelerates Tendon-to-Bone Healing After Rotator Cuff Repair. Am J Sports Med 2017; 45: 3322–3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farinas AF, Manzanera Esteve IV, Pollins AC, et al. Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging Predicts Peripheral Nerve Recovery in a Rat Sciatic Nerve Injury Model. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020; 145: 949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eshima K, Ohzono H, Gotoh M, et al. Effect of suprascapular nerve injury on muscle and regenerated enthesis in a rat rotator cuff tear model. Clin Shoulder Elb 2023; 26: 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachary CB, Burns AJ, Pham LD, et al. Clinical Study Demonstrates that Electromagnetic Muscle Stimulation Does Not Cause Injury to Fat Cells. Lasers Surg Med 2021; 53: 70–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai J, Xu J, Ye Z, et al. Exosomes Derived From Kartogenin-Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Cartilage Formation and Collagen Maturation for Enthesis Regeneration in a Rat Model of Chronic Rotator Cuff Tear. Am J Sports Med 2023; 51: 1267–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jovic D, Yu Y, Wang D, et al. A Brief Overview of Global Trends in MSC-Based Cell Therapy. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2022; 18: 1525–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldenberg BT, Lacheta L, Dekker TJ, et al. Biologics to Improve Healing in Large and Massive Rotator Cuff Tears: A Critical Review. Orthop Res Rev 2020; 12: 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazini L, Rochette L, Amine M, et al. Regenerative Capacity of Adipose Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Comparison with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh JH, Chung SW, Kim SH, et al. 2013 Neer Award: Effect of the adipose-derived stem cell for the improvement of fatty degeneration and rotator cuff healing in rabbit model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaizawa Y, Franklin A, Leyden J, et al. Augmentation of chronic rotator cuff healing using adipose-derived stem cell-seeded human tendon-derived hydrogel. J Orthop Res 2019; 37: 877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rak Kwon D, Jung S, Jang J, et al. A 3-Dimensional Bioprinted Scaffold With Human Umbilical Cord Blood-Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improves Regeneration of Chronic Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tear in a Rabbit Model. Am J Sports Med 2020; 48: 947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gulotta LV, Kovacevic D, Ehteshami JR, et al. Application of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in a Rotator Cuff Repair Model. Am J Sports Med 2009; 37: 2126–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith RK, Werling NJ, Dakin SG, et al. Beneficial effects of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in naturally occurring tendinopathy. PLoS One 2013; 8: e75697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Hu Q, Song W, et al. Adipose Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes Decrease Fatty Infiltration and Enhance Rotator Cuff Healing in a Rabbit Model of Chronic Tears. Am J Sports Med 2020; 48: 1456–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta R, Lee TQ. Contributions of the different rabbit models to our understanding of rotator cuff pathology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16: S149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]