Abstract

Compared with that of even the closest primates, the human cortex displays a high degree of specialization and expansion that largely emerges developmentally. Although decades of research in the mouse and other model systems has revealed core tenets of cortical development that are well preserved across mammalian species, small deviations in transcription factor expression, novel cell types in primates and/or humans, and unique cortical architecture distinguish the human cortex. Importantly, many of the genes and signaling pathways thought to drive human-specific cortical expansion also leave the brain vulnerable to disease, as the misregulation of these factors is highly correlated with neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. However, creating a comprehensive understanding of human-specific cognition and disease remains challenging. Here, we review key stages of cortical development and highlight known or possible differences between model systems and the developing human brain. By identifying the developmental trajectories that may facilitate uniquely human traits, we highlight open questions in need of approaches to examine these processes in a human context and reveal translatable insights into human developmental disorders.

Keywords: cortical development, human, model organisms

1 |. INTRODUCTION

How humans have attained a unique combination of higher-order cognitive traits remains one of the most central questions of biological research. Relative to other species, humans have a heightened ability to form complex social structures, communicate via verbal and written language, and develop preplanning and tools—specializations that may arise from human-specific characteristics of the neocortex. The increased complexity of the human neocortex is most striking at the anatomical level (reviewed in Lickiss et al., 2012). Relative to that of rodents and other common model organisms, the human neocortex occupies a greater proportion of the brain (Jerison, 1975; Stephan et al., 1981; Striedter, 2005) with a thicker cortical subplate (Glasser, Coalson, et al., 2016; Rakic et al., 1977; Rickmann et al., 1977). Much of this cortical expansion is supported by the folding of the neocortical surface into sulci and gyri, generating a surface area 1,000-fold that of the relatively smooth mouse cortex (Donahue et al., 2018; Herculano-Houzel et al., 2013).

Such anatomical differences are rooted in more complex variations at the cellular level (Clowry et al., 2018). For example, among mice and other small mammals, cortices with more neurons also have lower neuronal density—suggesting that increases in cortex size correlate with increased neuronal size. In contrast, humans and other primates do not conform to this rule and have a higher neuronal density compared with small mammals (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2015). Humans also have a more complex collection of cell types, including a diversity of interneuron subtypes (Krienen et al., 2020) and specialized Von Economo neurons (Allman et al., 2010; Evrard et al., 2012; Nimchinsky et al., 1999) that play roles in neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Santos et al., 2011), schizophrenia (Brüne et al., 2010), and dementia (Kim et al., 2012).

Although the evolution of the human brain has resulted in undeniably expanded and/or specialized functions, regions of the genome that are most recently derived compared with nonhuman primates are also the most enriched in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. In humans, noncoding regulatory regions of the genome are more distinct from nonhuman primates compared with coding regions, and recent genome-wide association studies have shown that these noncoding regions are also highly enriched for single-nucleotide variations significantly associated with susceptibility to neurodevelopmental disorders (Doan et al., 2016; Won et al., 2019). Human-specific protein-coding genes have also been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders. These include SRGAP2C, a human-specific gene linked to some cases of ASD, and the recently discovered NOTCH2NL, with potential roles in the genomic instability at the 1q21.1 locus that has been associated with ASD, micro/macrocephaly, and schizophrenia (Fiddes et al., 2018; Suzuki et al., 2018). Neurodevelopmental disorders have also been linked to human-specific genes enriched in loci such as 16p11.2 that contain copy-number variation hotspots (Nuttle et al., 2016). Human-specific pathway activation has also been associated with vulnerabilities to disease. For example, mTOR pathway activation is higher in human outer radial glia progenitor cells relative to those of nonhuman primates (Nowakowski et al., 2017; Pollen et al., 2019) and associated with numerous developmental and often structural brain abnormalities that can cause epilepsies or related disorders (Crino, 2020). In each of these examples and others, evolutionary differences between humans and other mammals may provide for some of the unique aspects of the human brain as well as vulnerabilities to disorder. In this review, we focus on the development of cortical cells derived from the dorsal telencephalon across model systems to highlight how the comparison of human cortex with that of model systems has laid the groundwork for a molecular understanding of human-specific cortical processes and given rise to the future directions required to more fully comprehend the human brain.

2 |. OVERVIEW OF COMMON AND HISTORICAL MODELS

A number of model systems have been primary tools for the study of cortical development. Simple neuronal systems such as the 302 neurons in C. elegans have established major principles including the role of terminal specification factors and the use of molecular identity to classify cell types (Hobert, 2018). Invertebrate systems such as Drosophila have provided and continue to reveal immense insights into brain patterning, terminal fate specification by temporal transcription factors, and axon pathfinding and connectivity (Oberst et al., 2019; Schmucker et al., 2000; Sen et al., 2019). Among mammals, rodents have provided a foundation for the current understanding of human cortical development by enabling the conditional expression or deletion of key patterning factors, studies that are detailed extensively in this review. Other models such as the ferret, though more difficult to genetically access, have provided a tool to explore cell types and patterns in a gyrencephalic (folded) cortex, compared with the lissencephalic (smooth) mouse cortex (Gilardi & Kalebic, 2021). Seminal experiments on the development of the visual system have also been performed in cats (Hubel & Wiesel, 1962). Nonhuman primates including macaque and newly emerging marmoset models (Mitchell & Leopold, 2015; Molnar & Clowry, 2012) enable lower throughput analysis of cell types, treatments, and disease-related mutations or toxins that most closely resemble human biology. Meanwhile, in vitro models such as neural progenitor cell culture, cortical organoids, and primary tissue cultures are beginning to provide insights in human cells directly (Kelley & Pasca, 2021). The core developmental principles established by this long history of model organisms provide a reference with which to understand what deviations may exist to generate the undeniably unique human cortex.

3 |. CORTICAL DEVELOPMENT, AS TOLD BY MODEL SYSTEMS

3.1 |. Patterning

One of the earliest events of corticogenesis is the division of the embryonic neuroepithelium into the various regions of the cerebral cortex (Cadwell et al., 2019; O’Leary et al., 2007). Seminal work using mouse models has revealed the patterning of these areas by gradients of morphogens throughout the neuroepithelium, such as the gradient of FGF emanating from anterior telencephalic patterning centers and the Wnt protein gradient from the cortical hem (reviewed in O’Leary et al., 2007). Mouse models are amenable to the perturbation of these morphogen gradients, revealing the essential roles of these factors on the size and identity of cortical areas. For example, the gradient of FGF8, which decreases along the anterior–posterior axis, establishes positional information for progenitor cells along this axis. Ectopic FGF8 expression is sufficient to induce posterior areas (Assimacopoulos et al., 2012), and modulating the levels of FGF8 at this patterning center induced corresponding shifts in the position of cortical areal boundaries along the anterior–posterior axis (Fukuchi-Shimogori & Grove, 2001; Garel et al., 2003). Similarly, studies ablating the cortical hem showed a reduced size of dorsomedial cortical areas in favor of ventrolateral areas (Caronia-Brown et al., 2014).

The positional information granted by these morphogen gradients is ultimately transmitted to differentiating cells via transcription factors. Functional interrogation of these factors in mouse models has been instrumental in revealing the landscape of possible molecular regulators defining the mammalian cortex. For example, FGF signaling represses the expression of the transcription factor and FGF agonist, Coup-tf1 (Borello et al., 2014; O’Leary et al., 2007), contributing to the gradient of Coup-tf1 expression along the posterior to anterior axis. In turn, COUP-TF1 is required for the boundaries of areas along this axis, specifically promoting posterior cortical regions such as sensory areas (Armentano et al., 2007). Conversely, the transcription factor SP8 has been shown to transduce FGF signaling and pattern rostral fates, in part by inhibiting Coup-tf1 expression (Armentano et al., 2007; Borello et al., 2014). Similar mutually antagonistic relationships have also been described between EMX2 and PAX6, which are expressed in reciprocal gradients along the anterior–posterior and mediolateral axes (Muzio et al., 2002; O’Leary et al., 2007). Genetic manipulation of these factors in mouse models has revealed the requirement of PAX6 in the maintenance of anteriolateral cortical areas (Bishop et al., 2000, 2002), whereas EMX2 maintains posteromedial fates (Bishop et al., 2000) in part by inhibiting FGF8 levels (Fukuchi-Shimogori & Grove, 2003). In this way, morphogen gradients along several positional axes provide a coordinate system that is integrated into cortical areal fates by key transcription factors.

Whereas mouse models provide a tractable mechanism for both discovering and mechanistically investigating the function of these areal patterners, tractable models for perturbing patterning mechanisms in the human brain do not exist. Mouse perturbational analyses have therefore established a model for cortical patterning mechanisms that serve as an essential foothold for the examination of patterning mechanisms in the developing human brain, which is inherently a descriptive enterprise. For example, immunohistochemical analyses of primary developing human brain tissue revealed the preservation of similar EMX2 and PAX6 gradients (Bayatti et al., 2008), and the reciprocal gradients of Sp8 and Coup-tf1 found in mice (Borello et al., 2014) are retained in the human across the anteromedial to posterolateral cortex (Alzu’bi et al., 2017).

Questions remain about how much these patterning mechanisms can be conserved in the larger human cortex (Figure 1a). In these larger organs, morphogens must traverse longer distances to fully recapitulate the gradients found in developing rodent brains. However, these molecules have dispersion ranges maxing at a few hundred microns (Parchure et al., 2018). A recent study of these patterning mechanisms in the developing ferret cortex found that FGF and Wnt gradients and patterning centers were recapitulated (Jones et al., 2019). Importantly, the length of the developing neocortex along the anterior–posterior axis at the time of FGF-induced patterning was comparable between ferrets and mice of equivalent developmental stages (Jones et al., 2019). However, ferret cortical expansion accelerated after these initial patterning stages (Jones et al., 2019). This hypothesis suggests that the patterning mechanisms in the mice may be recapitulated in larger mammals such as humans, if there is a similar delay in cortical expansion in human development (Jones et al., 2019).

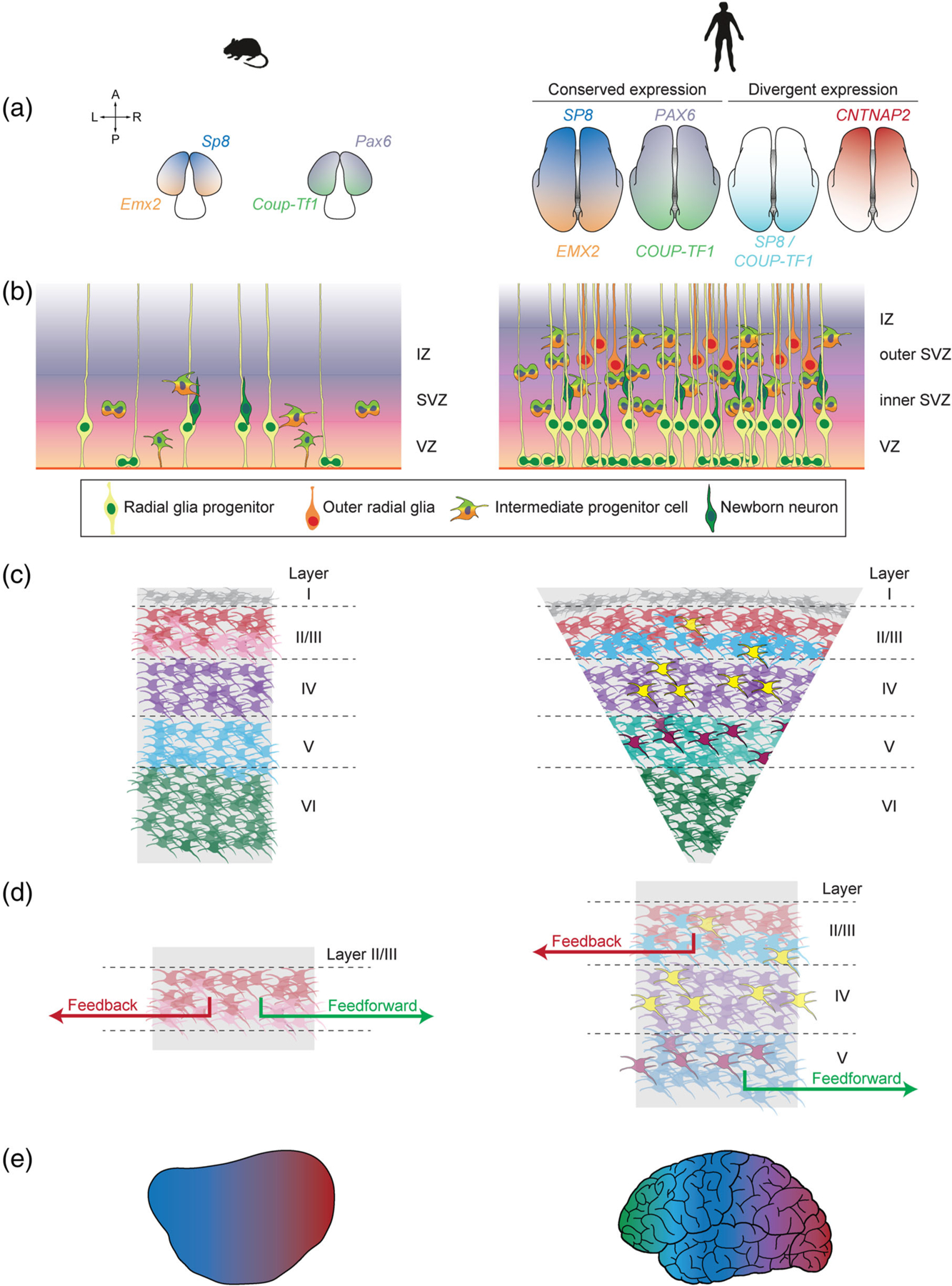

FIGURE 1.

Model organisms, including mice, highlight principles of cortical development, and their modifications in the human cortex. (a) Many patterning mechanisms dissected in seminal mouse model experiments are conserved in the developing human cortex. However, humans also display unique expression patterns, such as the coexpression of SP8 and COUP-TF1 transcription factors or the graded expression of CNTNAP2. (b) Both mice and human neurogenesis in the neocortex rely on the production of newborn neurons from progenitors in the neurogenic ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zones (SVZ), followed by their migration through the intermediate zone (IZ) to the cortical surface. However, humans have progenitors with greater proliferative capacity, expanded subventricular zones, and a specialized progenitor cell type called the outer radial glia that enables cortical expansion. (c) In both mice and humans, newborn neurons migrate radially to generate a six-layered cortex, segregated largely by cell type. However, human cell types show differences in laminar identities, such as the presence of neurons homologous to mouse layer V neurons in the human layer III (light blue cells) and human-specific neuronal subtypes (yellow and magenta). The human cortex also displays an expansion in the upper layers. (d) Although studies to delineate the conservation of projection specification principles between humans and mice are still ongoing, primates have been shown to display stricter rules in the laminar segregation of feedback and feedforward projections. (e) Recent transcriptomic studies have shown that both human and mouse cortical areas are defined by graded differences in transcriptomic identity—variations that are exacerbated in the human cortex

Alternatively, the patterning mechanisms characterized in the mouse may be altered in more nuanced ways in the human cortex. Indeed, even at this early stage, there exist subtle differences in the developmental programs found in mice versus those found in humans and other primates. Unlike the mouse cortex, the human cortex shows the disappearance of the PAX6 gradient 8 weeks after conception and the expression of EMX2 in postmitotic neurons of the cortical plate where it might interact with PAX6-regulated transcription factors (Bayatti et al., 2008). In addition, SP8 and COUP-TF1 differ in the human in that they have overlapping expression patterns in the ventricular zone of the human visual, auditory, and somatosensory cortex (Alzu’bi et al., 2017). Early microarray analyses to identify transcription factor gradients in the developing human neocortex highlighted the conservation of several mouse transcription factors such as the posteriorly enriched EMX2 and COUP-TF1, but also the presence of new factors such as the anteriorly enriched CNTNAP2 (Ip et al., 2010). More recent single-cell transcriptomic profiles of the human cortex have further highlighted the divergence between these species’ developmental programs. In particular, there are interspecies differences in the developmental timing of embryonic gene networks (Mathys et al., 2019), the genes driving cell type specification (Hodge et al., 2019), and the transcriptomic heterogeneity within cell types (Bakken et al., 2021; Hodge et al., 2019).

These subtle differences suggest that the human cortex contains another layer of patterning programs that may form more complex parcellations of the cortex in a way that is underappreciated by mouse models. This combination of differences could be what initiates the divergence between humans and model organisms. Future work using platforms for the perturbation of human cortical progenitors can elucidate both the human-specific patterning regulators that have been inaccessible in a mouse-centric approach as well as the human-specific signaling mechanisms that modulate conserved patterning regulators. For example, human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell models have provided a platform for high-throughput gene perturbation screens via CRISPR technology, which has been used to determine the genes that maintain transcriptomic identity in stem cell–derived neurons (Tian et al., 2019) as well as genes that are sufficient to drive human progenitors toward neuronal identities (Black et al., 2020). CRISPR-mediated perturbation screens have also been applied to cerebral organoids, enabling the dissection of the gene regulatory networks involved in deriving human brain regions (Fleck et al., 2021). Although these in vitro models have limitations in their ability to recapitulate the developing human brain (Bhaduri et al., 2020), further perturbation analyses in these more tractable models of human brain development will continue to highlight avenues for improving these platforms and ultimately deepen our molecular understanding of human corticogenesis.

3.2 |. Neurogenesis

Basic principles of neurogenesis have also been delineated in the mouse model (Figure 1b). In mice and most other lissencephalic species, cortical neurogenesis originates first from the ventricular zone (VZ), a sheet of progenitor cells between the cortical preplate and brain ventricles (Bayer & Altman, 1991). This is followed by the emergence of the subventricular zone (SVZ) between the cortical preplate and the VZ (Smart, 1973). Neurogenesis occurs via progenitors within these zones, including ventricular radial glia and intermediate progenitor cells (Casingal et al., 2022). Ventricular radial glia progenitors typically divide asymmetrically to produce intermediate progenitors and replenish the ventricular radial glia pool, whereas intermediate progenitors divide symmetrically for rapid neurogenesis (Borrell & Reillo, 2012; Florio & Huttner, 2014; Haubensak et al., 2004; Lui et al., 2011; Miyata et al., 2004; Noctor et al., 2004). Neurons then migrate radially, moving toward the cortical surface.

Although many of these basic principles have been conserved in humans and primates, these species have changes in cell division symmetry, cell-cycle length, and duration of proliferative state that have been thought to contribute to the considerable cortical expansion among primate species (Florio & Huttner, 2014). These complex evolutionary processes have been addressed extensively in recent reviews (Kalebic & Huttner, 2020; Mostajo-Radji et al., 2020; Sousa et al., 2017), and we highlight a few divergences between mouse and primate models here. For example, primates harbor an outer subventricular zone absent in most lissencephalic species, including mouse, that also grows progressively thicker (Reillo et al., 2011; Smart et al., 2002). This growth is driven in part by progenitor subtypes in primates that can undergo self-renewing divisions to produce a larger neurogenic pool (Betizeau et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 2010; Reillo et al., 2011). In particular, the outer SVZ contains outer radial glia, a distinct radial glia cell type that has lost processes to the brain ventricles and gained an increased capacity to produce both outer radial glia and intermediate progenitor cells (Fietz et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2010).

Compared with rodents, primates also have a distinct and protracted maturation that allows for increased neurogenesis, patterning, and specialization (Mundinano et al., 2015; Warner et al., 2012). Progenitor cells in primate ventricular zones tend to begin neurogenesis at later time points, enabling more time to generate a proliferative pool (Kornack & Rakic, 1998; Rakic, 1995, 2009). Neurogenesis is then up to ten times longer in humans and other primates (Caviness Jr et al., 1995; Rakic, 1995). Human-specific genes have begun to be attributed to these distinct developmental mechanisms. For example, in human in vitro neuronal models, the humanspecific NOTCH2NLB was sufficient to prolong proliferation by increasing entry into and decreasing exit from the cell cycle (Suzuki et al., 2018) and delaying differentiation (Fiddes et al., 2018). Similar strategies that leverage human-specific gene profiles and tractable models of human neurogenesis can continue to test how the neurogenic mechanisms in the mouse are modulated to enable cortical expansion in the human.

3.3 |. Gliogenesis

Neurogenesis is followed by gliogenesis, the production of glial cells including astrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), and oligodendrocytes. These cells play essential roles in the synaptogenesis, neural circuit maturation, and refinement of neuronal populations during development and into adulthood (Barres, 2008). As in neurogenic mechanisms, core aspects of gliogenesis are largely conserved between mice and humans, though a more temporal overlap between the two processes is observed in the human cortex given its protracted maturation (Semple et al., 2013). Humans are also marked by a uniquely expanded white matter comprised of myelinating oligodendrocytes, and recent work has identified human-specific EGFR-positive transit-amplifying OPC populations derived from human’s outer radial glia cells (Huang et al., 2020). Human-enriched progenitor subtypes, such as outer radial glia, therefore beget human-enriched glial populations, such as specific OPCs. Indeed, substantial differences exist between the populations of astrocytes and other glial populations in the rodent and primate brain, with some of the human glial cells being more complex than even nonhuman primates. For example, whereas protoplasmic astrocytes constitute the vast majority of astrocytes in both the primate and mouse, human astrocytes across all classes are larger, more complex and have more subtypes than rodent astrocytes (Oberheim et al., 2006; Robertson, 2014). Human and other primate brains also contain unique, radial glia-derived interlaminar astrocytes that cross cortical layers (Colombo & Reisin, 2004), divide locally after birth, and mature well into postnatal periods (Falcone et al., 2020). Astrocytes are therefore an important aspect of primate and human brain evolution, though future studies are required to fully explain how human-specific astrocyte populations have evolved and how they arise and mature during human brain development. Given the extensive role of both astrocyte and oligodendrocyte populations in the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders, these differences between rodents and humans/nonhuman primates raise important points of mechanistic difference.

3.4 |. Layer formation

Newborn neurons are born in an inside-out fashion: deep layers are generated first followed by upper layers, organizing the newborn neurons into the six layers of the neocortex (reviewed in Greig et al., 2013; Figure 1c). Subplate neurons are born first and reside in layer VI, the layer closest to the ventricular zones. These are followed by the corticofugal projection neuron subtypes (such as the subcerebral projection neurons and the corticothalamic projection neurons), the granular neurons, and finally the callosal projection neurons populating the upper layers. An important exception is the uppermost layer closest to the cortical surface (layer I), populated by early-born Cajal-Retzius neurons that modulate both neural progenitor proliferation (Griveau et al., 2010) and the correct orientation of layers (Germain et al., 2010). Cortical layers facilitate the organization of not only these neuronal subtypes but also various types of neuronal connections. Upper layer neurons connect to other regions within the neocortex, whereas layer IV receives inputs from thalamic nuclei and the deeper cortical layers connect to brain structures outside of the cerebral cortex (Franchini, 2021).

The adoption of layer-specific phenotypes largely occurs as postmitotic neurons migrate through and mature within the cortical plate. For example, rodent studies have shown that markers for the two corticofugal projection neuron subtypes are coexpressed until the emergence of subtype-specific axonal trajectories (Molnár & Cordery, 1999), at which time the neurons express either Ctip2 or Tbr1 to commit to either the subcerebral or corticothalamic projection neuron fate (Deck et al., 2013).

Studies in mouse models have also delineated the molecular programs that maintain and refine these layer identities to ensure appropriate laminar organization of neuronal subtypes. These include the delineation between the upper layer callosal projection neurons that connect to the midline of the brain and deep layer corticofugal projection neurons that connect to sites outside the cortex. The molecular identity and connectivity patterns of callosal projection neurons are maintained by Satb2, which repress corticofugal projection neuron gene networks and axonal growth to the brainstem and spinal cord (Alcamo et al., 2008; Britanova et al., 2008). Conversely, callosal projection neuron fate is attenuated by Fezf2, which is sufficient to redirect axons away from the corpus callosum and toward subcortical targets (Chen et al., 2008; Molyneaux et al., 2005; Rouaux & Arlotta, 2013). Corticofugal projection neurons are further specified into layer-enriched subtypes. The subcerebral projection neuron subtype is restricted to layer V, with Fezf2 maintaining subtype-specific gene-expression patterns and Ctip2 directing axonal outgrowth to subtype-specific targets (Arlotta et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2005; Molyneaux et al., 2005). Fezf2 is also expressed at lower levels in corticothalamic projection neurons of the layer below, layer VI (Molyneaux et al., 2005). In turn, corticothalamic projection neuronal identity relies on Tbr1, which participates in a mutually repressive network with Fezf2 (Bedogni et al., 2010; Han et al., 2011; McKenna et al., 2011; Molyneaux et al., 2005). More comprehensive analyses of layer-specific transcriptomic signatures via single-cell transcriptomics have revealed a gradual transition of transcriptomic identity between cortical layers in the glutamatergic neurons of the adult mouse cortex, rather than the presence of discrete borders (Yao et al., 2021). For example, the well-established layer IV marker gene Rorb was detected in multiple layers (Yao et al., 2021). These findings point to the presence of more complex gene networks that might finetune the identities of neuronal subtypes within these layers, mechanisms that can be further elucidated using the increased resolution of single-cell profiling.

On a broad level, the specification of cortical layers described in the mouse is largely conserved in humans (Franchini, 2021). Newborn neurons in the human cortex also possess a mixture of laminar identities (Li et al., 2018) prior to their segregation into cortical layers, which are also delineated by gradual variations in transcriptomic identity (Hodge et al., 2019). Transcriptomic comparisons of the human middle temporal gyrus and primary motor cortex with murine visual and motor cortical areas also show a general conservation of cell types across species (Bakken et al., 2021; Hodge et al., 2019). But primate-specific specializations in laminar size and cell types allude to important differences from mouse, particularly in the upper layers. Although glutamatergic neurons in the upper layers of both the human and mouse cortex fall into three broad cell types, the upper layers of primate cortices comprise almost a three-fold greater proportion of the cortical plate (DeFelipe et al., 2002; Kriegstein et al., 2006), potentially at the expense of deep-layer neurons (Bakken et al., 2021). Heterogeneity in cell transcriptome, electrophysiology, morphology, size, and density is elevated within human upper layer subtypes, variations that appear correlated to cortical depth (Hodge et al., 2019; Kalmbach et al., 2018; Von Economo, 2009). For example, some human-specific upper layer subtypes harbor complex dendritic networks that likely enable the integration of multiple inputs and long-range projections (Bakken et al., 2021). In deeper layers, the corticospinal Betz cells display electrophysiological characteristics such as bursting and spike-frequency acceleration, facilitating high conduction velocity (Chen et al., 1996; Miller et al., 2008; Spain et al., 1991; Vigneswaran et al., 2011). Primate upper layer neurons may therefore have further functional specializations to maintain information flow in the expanded primate cortex, mechanisms that are largely inaccessible via mouse studies.

The functional specializations of layer-specific subtypes within the human cortex may stem from subtle specializations in laminar molecular programs. Early in situ hybridization experiments comparing the gene-expression profiles of layers within the mouse versus human visual cortex showed that although the majority of gene-expression patterns were conserved, 199 genes were differentially expressed in the human (Zeng et al., 2012). Strikingly, half of the laminar marker genes identified in the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas showed differential expression patterns in the human (Zeng et al., 2012). Cell types can also shift layer positions between the two species, most notably from layer V in the mouse to the upper layers in the human (Bakken et al., 2021; He et al., 2017; Hodge et al., 2019). Human distinctions from other primate species have also been identified. A comparison of layer-specific transcriptomes between macaque, chimpanzee, and human prefrontal cortices revealed that a majority of putative layer-specific marker genes displayed differential expression between the three species (Ho et al., 2017). These studies also allude to the presence of a human-specific layer III, as the human cortex was marked by an increased frequency of macaque or chimpanzee layer V marker genes shifting to expression in layer III (Ho et al., 2017). Many of these genes were associated with pyramidal neurons, suggesting that these genes may help humans develop upper-layer neurons that have human-specific intracortical projections (Ho et al., 2017).

These recent studies highlight a number of open questions surrounding laminar organization, such as how human-specific changes in neurogenic timing, neuronal migration, and/or specification mechanisms contribute to upper layer neuron diversity and expansion. Further, many of the cross-species laminar comparisons described above (Bakken et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2017; Hodge et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2012) have been limited to intrinsic determinants in one cortical area. However, inputs from the thalamus, a subcortical structure specializing in sensory inputs, and developmental differences across cortical areas may also play a role in modifying laminar organization for human cognition. Expanded higher-resolution profiles of the laminar subtypes in both mouse and primate models are therefore essential toward understanding the specification of cortical layers and how they facilitate cortical function. Comparisons between these richer datasets will then deepen our understanding of the specific adjustments that support human-specific cognition.

3.5 |. Projection specification

The cognitive power of the cortex ultimately relies on a diverse range of projection neurons to process a variety of inputs. These projections can either originate from or travel to higher-order cortical areas associated with language, vision, spatial recognition, and awareness, generating feedback or feedforward circuits, respectively. Projection neurons can be divided into three categories based on their targets: corticothalamic neurons that predominantly exhibit feedback projections to the thalamus, pyramidal tract neurons that typically connect to the brainstem and spinal cord, and the diverse intratelencephalic projection neurons usually connecting to a variety of subcortical structures.

Much of the initial work investigating how projection neurons connect with each other used the cat somatosensory cortex (Mountcastle, 1957), defining cortical neurons within the same vertical mini-column to be the smallest functional circuit (Mountcastle, 1997). Model organisms have since revealed several types of microcircuits, defined based on the transcriptomically defined cell types involved (reviewed extensively in Kast & Levitt, 2019). These include thalamocortical circuits, generated by axons originating from the thalamus which first form transient synapses with cortical subplate neurons located near the ventricles (Ghosh & Shatz, 1994; Ghosh et al., 1990; Kanold et al., 2003). These transient connections are an essential step in guiding thalamic axons toward the cortical plate (Ghosh & Shatz, 1994; Ghosh et al., 1990; Kanold et al., 2003), where they establish connections within the layer V/VI boundary and, more prominently, within layer IV (Agmon et al., 1993). Cortical targets within layer IV eventually grow more sensitive to thalamic inputs than those in the deeper layers (Crocker-Buque et al., 2015), in part via synaptic remodeling conducted by specific interneuron subtypes (Marques-Smith et al., 2016; Tuncdemir et al., 2016). There are also microcircuits with connections originating from layer IV or layer V and projecting to layer II/III neurons, with studies in the rat barrel cortex showing that the upper layer II/III harbors a greater number of layer V targets with a greater sensitivity to layer V inputs than found in the lower layer II/III (Bureau et al., 2004; Staiger et al., 2015). In contrast, work in the mouse motor cortex has shown that the sensitivity of layer V neurons to projections from layer II/III is highly variable depending on the sublaminar position and cell type identity of the target layer V neuron (Anderson et al., 2010). In this way, cell types are the backbone of appropriate microcircuitry.

Even in the context of the rodent brain, how these basic principles of local microcircuitry are modified to generate connections to different areas of the cortex or subcortical structures remains unclear. As summarized in Kast and Levitt (2019), recent work in this rapidly evolving field suggests the reliance of these long-range networks on a combination of (1) an initial wave of promiscuous axonal projections from each cortical area followed by selective pruning and (2) a prepatterned program of axonal projections. In either case, initial synaptic connections within these long-range networks appear to be stabilized in a manner dependent on electrical activity (Mizuno et al., 2007; Suárez et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2007). Model organisms have recently revealed how these projections may be established during cortical development on a molecular level. These processes likely rely on surface molecule interactions between neurons and their microenvironment (reviewed in De Wit & Ghosh (2016). Recent studies have begun to catalog interatomic datasets for various surface molecules on Drosophila melanogaster neurons (De Wit & Ghosh, 2016), and a number of receptor tyrosine kinases and other molecules have been implicated in axon guidance in the mouse (Fothergill et al., 2014; Lodato et al., 2014; Srivatsa et al., 2014; Torii & Levitt, 2005; Torii et al., 2013). Other extracellular programs, such as morphogens, may also play a role. Recent work has shown that expression of the Sonic hedgehog hormone from layer V neurons and its receptor, Boc, from neurons in adjacent layers is required for appropriate connectivity strengths between layer V and layer II/III (Harwell et al., 2012). The complete set of membrane proteins that participate in the delineation of projections is as yet incomplete, and many efforts to elucidate projection specification have yet to fully integrate the increased diversity of cell types detected in single-cell transcriptomic studies, which may further alter our understanding of cortical circuitry.

Definitive cross-species comparisons to determine how these circuitry patterns are conserved in the human brain and adapted to support the expansion of the upper layers are still ongoing. However, the mechanisms by which projections are specified among small mammalian model organisms have clear differences. For example, a comparison of mouse visual cortex with that of cats and tree shrews shows that there are distinctions in connectivity patterns within layer IV. In the cat visual cortex, the spatial orientation of visual stimuli is perceived and processed by layer IV intratelencephalic neurons based directly on the organization of their innervation by thalamic neurons (Reid & Alonso, 1995). However, studies using the tree shrew found that the processing of visual stimuli requires neurons within layer IV sublayers to first feed this visual information to layer II/III neurons (Van Hooser et al., 2013). In the rodent primary somatosensory and auditory cortices, layer IV neurons process thalamic inputs in a manner dependent on the timing of excitation and inhibition (Wehr & Zador, 2003; Wilent & Contreras, 2005). Therefore, multiple patterns of connectivity within layer IV neurons appear to be species-specific.

Current work surrounding primate connectivity suggests that, despite the stark size differences between murine and primate brains, mice recapitulate many characteristics of the feedforward and feedback connections between cortical areas that support cognitive processing within the primate brain (Coogan & Burkhalter, 1990; Markov et al., 2014; Rockland & Pandya, 1979; Wang et al., 2012). Both rodent and primate cortices display reciprocal feedforward and feedback projections connecting two cortical areas (Felleman & Van Essen, 1991; Harris & Shepherd, 2015; Markov et al., 2014), and anterograde tracer experiments into mouse visual cortical areas revealed that nearby areas harbor more connections than distal areas in networks organized similarly to those found in primates (Wang et al., 2012). However, interareal projections are guided by much more restrictive rules in the primates (Figure 1d). In the rodent visual cortex, there is minimal layer-specific segregation of feedforward or feedback projections (Berezovskii et al., 2011), with the exception of the exclusion of feedback projections from layer IV neurons (Coogan & Burkhalter, 1993). In contrast, interareal projections in the macaque cortex originate and terminate in distinct layers based on their status as a feedforward or feedback projection (Markov & Kennedy, 2013; Rockland & Pandya, 1979). In deep layers of the rodent cortex, reciprocal pairs of feedforward–feedback projections are composed of feedforward projections targeting one or two areas (Kim et al., 2020) and feedback projections free to project beyond their reciprocal area (Young et al., 2021). Interareal connections in the visual cortices of primates and cats are more restricted, with feedforward projections rarely projecting to multiple areas (Bullier et al., 1984; Ferrer et al., 1992; Sincich & Horton, 2003), and feedback projections restricted to a specific target area (Siu et al., 2021). These studies suggest that strict laminar and areal segregation of cortical circuits enables the formation of a much more complex cortical hierarchy within the primate cortex. However, direct comparisons across small mammals, nonhuman primates, and humans are required to make definitive conclusions on the conservation of these rules in the human brain and their functional implications.

3.6 |. Arealization

Neocortical progenitors adopt unique neuronal identities corresponding to their position within the neocortex. These area-specific characteristics have been studied since the early 20th century, when histological studies of postmortem human cortical tissue revealed spatial changes in lamination patterns, neuron densities, and cell morphologies (Brodmann, 1909; Charvet et al., 2015; DeFelipe et al., 1999; von Economo & Koskinas, 1925). For example, layer IV is subdivided into three sublayers in the primary visual cortex, but largely absent in the primary motor cortex (Cadwell et al., 2019). Neuronal densities, particularly in the upper layers, vary by as much as two-fold throughout cortical areas (Charvet et al., 2015), and a number of area-specific specialized cell types have been identified such as the Betz cells restricted to the primary motor cortex and the Von Economo neurons localized in the frontal, insular, and anterior cingulate cortices (von Economo & Koskinas, 1925). In line with these area-specific structures, areas have also been shown to control specific cognitive functions. The prefrontal cortex, for example, has well-established roles for executive decision-making, whereas movement, vision, and hearing are regulated by corresponding motor, visual, and auditory cortical areas. These functionally specialized cortical areas form a network that processes a variety of stimuli into concrete behaviors, driving the cognitive power of the human brain.

Recent years have seen a wave of areal characterization at the molecular level via transcriptomic profiling. Initial studies assessing the transcriptomes of bulk mouse cortical tissue were unable to detect the substantial differences between areas, likely due to the conservation of a basic set of cell types across different cortical areas (Harris & Shepherd, 2015; Yamawaki et al., 2014). However, single-cell transcriptomic analyses evaluating gene expression within individual cells have revealed that although cortical areas share a common set of inhibitory neuronal subtypes that have migrated to the cortex, several subclasses of excitatory neurons that originate from the cortical subventricular zone are unique to specific groups of adjacent cortical areas (Tasic et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). The variations between these area-specific transcriptional signatures are subtle, producing a continuum of transcriptomic identity among the cell types within areas (Tasic et al., 2016, 2018; Yao et al., 2021). Cell types at the poles of this spectrum express highly discrete gene-expression profiles, and intermediate cell types display more combinatorial transcriptomes (Tasic et al., 2016, 2018; Yao et al., 2021). Thus, the discrete functional divisions between cortical areas are built at least in part on subtle differences in transcriptomic identity that gradually shift along the anterior–posterior and mediolateral axes (Yao et al., 2021).

These transcriptomic profiles have advanced efforts to understand the molecular mechanisms encoding unique areal characteristics. For example, the genetic ablation of specific Cajal-Retzius neuronal subtypes in mouse cortices results in the redistribution of Cajal-Retzius subtypes across cortical areas and subsequent changes in the transcriptional identities of cortical progenitors (Griveau et al., 2010). Mouse models have also begun to reveal the molecular determinants that define areal boundaries. These include the transcription factors Lmo4, which facilitates sensorimotor skills by maintaining the rostromedial boundary of the murine somatosensory barrel field (Cederquist et al., 2013), and Bhlhb5, which establishes molecular and cytoarchitectural identities in the somatosensory and caudal motor cortices (Joshi et al., 2008). A transcription factor cascade consisting of Pax6, Eomes, and Tbr1 has also been shown to both mediate the differentiation of radial glia to neurons (Englund et al., 2005) and define regional distributions of gene-expression and axonal projections (Elsen et al., 2013), suggesting that intrinsic gene programs may encode areal identities in neocortical progenitors. The identities established by such determinants may be refined further by extrinsic factors. One of the most well-studied among these are connections between neurons in the cortex with those in the thalamus (Haber & Calzavara, 2009). In rodents, signals from thalamocortical axons are thought to refine cell morphologies (Li et al., 2013; Narboux-Nême et al., 2012), cell fate (Chou et al., 2013; Pouchelon et al., 2014; Vue et al., 2013), neurogenesis and lamination (Monko et al., 2021), and size (Dehay et al., 1991, 2001; Reillo et al., 2011), particularly in sensory areas. Further studies will reveal the full scope of intrinsic and extrinsic determinants that define cortical areas, and how they are integrated to produce the complex transcriptomic and phenotypic profiles that delineate these regions.

The key differences in arealization between mice and humans are likely to have the most impact on human cortical development and disease. Profiles of human primates have shown the conservation of arealization principles described in rodent models, such as the gradual shifts in transcriptomic identity across cortical areas and the presence of area-specific molecular signatures in neuronal progenitors and neurons alike (Bhaduri et al., 2021). However, the expansion of the cortex in primates is accompanied by an increased specialization between areal identities (Figure 1e). Area-specific differences in electrophysiological and morphological properties of neurons in the prefrontal cortex versus the primary visual cortex occur in the macaque, but not the mouse (Gilman et al., 2017), and the Cajal-Retzius cells shown to regulate areal identities display greater morphological and transcriptional complexity in primates (Meyer, 2010; Meyer & Goffinet, 1998; Pollard et al., 2006; Roy et al., 2014). Differences in areal specializations exist even between human and nonhuman primate models, including an increased number of functional areas (Glasser, Smith, et al., 2016; Markov et al., 2014; Paxinos et al., 2000) and area-specific organization of cortical folds (Coalson et al., 2018; Glasser, Coalson, et al., 2016). Direct transcriptomic comparisons of macaque and human cortical areas have sought to reveal the molecular underpinnings of these human-specific traits (Li et al., 2018), finding broad similarities between the two species. These include a pattern in which areal transcriptomes were highly divergent prenatally, became more similar throughout childhood, and diverged again in the transition to adulthood (Li et al., 2018). However, human neocortical development is also protracted relative to that of nonhuman primates, with gene programs linked to myelination and synaptogenesis exhibiting progressive increases in activity throughout human development but plateauing in the macaque (Li et al., 2018). Phases of peak interareal differences also saw the greatest species-specific differences, suggesting that the differences delineating humans from macaques occur during the formation of areal identities (Li et al., 2018).

Species-specific differences appear to be enriched in the prefrontal cortex, particularly in genes associated with cell proliferation and myelination (Li et al., 2018). Humans contain unique, prenatal gene programs that are enriched anteriorly and include gene modules linked to axon guidance and retinoic acid signaling, implicating these processes in modifying the prefrontal cortex for human cognitive abilities (Li et al., 2018). Conversely, the enrichment of postnatal gene modules characterized by oligodendrocyte markers has been detected in all primary areas of the macaque neocortex, but only in the human primary motor and auditory cortices (Li et al., 2018). Primates, therefore, have a conserved framework for cortical arealization that may be altered in specific areas. Although the differences between humans and other primates are more subtle, targeting the most impactful questions surrounding human cortical development and disease relies on a greater degree of accuracy and tractability than can be achieved from even nonhuman primate models.

Similar to its effect on the study of cortical lamination, single-cell profiling has deepened our understanding of cortical arealization and raised further questions of these mechanisms in both mice and primates. In addition to experiments establishing how intrinsic gene programs establish and maintain areal fates, future work will also be required to understand how extrinsic inputs from the thalamus and downstream phenotypes at the epigenomic, proteomic, and connectomic levels coalesce into functionally distinct cortical areas. Mouse models can continue to elucidate the basic principles by which subtle transcriptomic differences generate cortical specializations. But identifying and functionally interrogating areal determinants in postmortem or in vitro models of human cortical development will ultimately be required to elucidate the arealization of the human brain.

4 |. THE USE OF MODEL SYSTEMS IN EXAMINING NEURODEVELOPMENTAL AND NEUROPSYCHIATRIC DISEASES

Maintaining the intricate developmental mechanisms described above is integral to cortical function, and derailment of any of these processes can give rise to neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Much as they have been used to assess physiologically normal developmental mechanisms, mouse and nonhuman primate models have also fueled mechanistic insights into neurological diseases. For example, ASD patients have defects in long-range cortical circuits in favor of local cortico–cortical circuits (Courchesne & Pierce, 2005), a phenomenon recapitulated in mouse models with mutations in ASD-linked genes such as Cntnap2 (Liska et al., 2018) or in Pten+/− mice modeling ASD and mTOR-linked macrocephaly (Huang et al., 2016). Studies in mouse models with Cntnap2 mutations have also shown that these connectivity phenotypes are driven by defects in the pyramidal cells projecting to the prefrontal cortex (Liska et al., 2018). In addition, mouse models harboring duplications in the ASD-linked Cyfip1 display the abnormal development of prefrontal cortex neurons as well as defective mTOR signaling (Oguro-Ando et al., 2015). Taken together, these mouse models provide a model linking together ASD connectivity phenotypes, projections involving the prefrontal cortex, and mTOR signaling.

Mouse models have also informed studies of schizophrenia etiology. Deficiency in dopaminergic neurotransmission in the cortex and increased dopamine release in the striatum is common in schizophrenia patients (Howes et al., 2012). These phenotypes are mirrored in mouse models harboring deletions in the 22q11.2 locus linked to neurodevelopmental disorders. Parvalbumin-expressing interneurons in these mice have less sensitive dopamine receptor subtypes, with a reduced capacity to modulate synaptic excitatory–inhibitory balance (Choi et al., 2018). Mice with defects in prefrontal cortex neuron excitability have also been shown to exhibit increased striatal dopamine release (Kim et al., 2015). Specific subtypes among interneurons or prefrontal cortex neurons might therefore play a role in the dopaminergic defects described in schizophrenia.

These examples highlight the ability of mouse models to not only recapitulate phenotypes in neurological disorders but also offer cellular and molecular insights into the connections between disparate phenotypes. However, these systems are insufficient in recapitulating multifaceted phenotypes of many of these disorders, driving a need to expand model systems beyond what is possible in the rodent (reviewed extensively in Zhao & Bhattacharyya, 2018). For example, though rodent models of schizophrenia mimic both disordered dopamine release and hyperactive behaviors, these traits are present in only a subset of schizophrenia patients, suggesting that mouse models may mimic schizophrenia phenotypes through distinct mechanisms (Scott & Bourne, 2021). The ability of rodents to model human disorders is also limited by the uniquely primate or human divergences to the core principles of cortical patterning, neurogenesis, gliogenesis, arealization, and projection specification described in model organisms. Although models for disorders of mTOR dysregulation exist, mTOR activation has been shown to be specifically higher in human outer radial glia cells (Lacreuse et al., 2018; Mansouri et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2005), which inherently cannot be replicated in a mouse. Glial cells are well described to play an essential role in both normal cortical development and in ASD and other developmental disorders (Barres, 2008), yet there are substantial differences between astrocyte subtypes in the mouse versus in the human. The prefrontal cortex is a crucial hub for area-specific phenotypes in various disorders including ASD or neuropsychiatric disorders, yet the overall similarity between a human and rodent prefrontal cortex remains controversial (Laubach et al., 2018). Though mouse models have provided foundational insights into some aspects of neurodevelopmental disorders, as we learn more about the human brain and its unique features, additional approaches to study these diseases will be required.

Nonhuman primate models may improve insights into neurological disorders, owing in part to their unique ability to perform behavioral tests of broad executive function (Alexander et al., 2020; Stawicka et al., 2020) and perceptual and value-based decision-making (Setogawa et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019). Macaque models with mutations in the ASD-linked SHANK3 gene have demonstrated reduced social interactions and eye contact, as well as anxiety (Tu et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019). In the marmoset, overactivation of areas within the primate-specific ventromedial prefrontal cortex can increase threat-induced anxiety responses (Alexander et al., 2020; Stawicka et al., 2020) and decrease motivation (Alexander et al., 2019).

But these insights are still limited by the subtle molecular distinctions between humans and other primates, particularly in terms of arealization. Genes associated with ASD, schizophrenia, and other neurodevelopmental disorders were among the genes displaying human-specific expression patterns relative to macaque (Li et al., 2018). Among these were schizophrenia-associated genes displaying human-specific, prenatal expression in the prefrontal and temporal cortices (Li et al., 2018). ASD-linked SHANK2 and SHANK3 genes, encoding components of excitatory glutamatergic synapses, were also expressed later in the human than in the macaque, whereas the schizophrenia-associated GR1A1, also a component of excitatory glutamatergic synapses, is expressed earlier in various human cortical areas (Li et al., 2018). Thus, targeted changes in spatial and temporal transcriptomic patterns between the human and macaque could have the biggest implications for neurodevelopmental disease. Although nonhuman primates and other model organisms provide valuable models of neurodevelopmental disease etiology, testing these mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in human models of neurodevelopment will be vital for effective treatments.

5 |. FUTURE DIRECTIONS TOWARD MODELING THE HUMAN BRAIN

Model systems such as C. elegans, Drosophila, and rodents have provided essential conceptual frameworks for the study of cortical development and will remain relevant to the field of human developmental neurobiology given the inaccessibility of primary human cortical samples. However, addressing the most impactful questions surrounding the human brain requires a rigorous understanding of the limitations of each model system and a goal toward a more authentic representation of the human cortex. These challenges require the following steps.

5.1 |. Continue to build the molecular landscape of human neurodevelopment

By applying recent advances in single-cell omics toward existing sources of primary human cortical samples, future work can build more comprehensive profiles of human cortical development that can serve as conceptual frameworks for experiments in model systems. Initiatives led by BRAIN2.0 such as the recent Brain Initiative Cell Census Network collection have begun to generate transcriptomic atlases of human neurodevelopment. Analogous studies in cortical tissue from a greater range of developmental stages and cortical areas will be necessary to expand on the resolution and depth of these datasets. These can be augmented by further profiling the human cortex at the epigenomic, proteomic, and connectomic levels, revealing how gene regulatory networks, signaling pathways, and neuronal circuits drive human neurodevelopment. These profiles can also be compared with the well-studied cortical processes established in mice and other species to identify the human mechanisms that are well-suited for investigation in these model systems and maximize the scientific potential of these platforms.

5.2 |. Develop in vitro systems into more accurate models of human cortical development

Molecular profiles of the primary human cortex can also guide the development of tractable, human-derived model systems. Such goals would take advantage of advancements in human in vitro systems. For example, protocols to culture sliced, primary human tissue have recently evolved to enable the observation and manipulation of progenitors, glial cells, and neurons in adults (Andersson et al., 2016; Schwarz et al., 2019; Ting et al., 2018) and developing (Linsley et al., 2019; Retallack et al., 2016) human cortex. Importantly, these models retain much of the complex spatial organization and electrophysiology essential for cognitive processing by the cortex (Schwarz et al., 2019; Ting et al., 2018). These structures can be manipulated with lentiviral transduction or optogenetics (Andersson et al., 2016; Schwarz et al., 2019; Ting et al., 2018), and more recent protocols have developed high-throughput systems to image individual cells in the developing human brain over the course of almost three weeks (Linsley et al., 2019). The continued development of such techniques could enable long-term monitoring of individual neurons at a large scale and, ultimately, the generation of rich datasets informing models of how neurons are generated, mature, adopt laminar and areal fates, and form connectivity patterns in the developing human cortex.

Advances in the long-term culture of primary human tissue have accompanied developments in three-dimensional, human stem cell–derived organoid systems (reviewed in Zhao & Bhattacharyya, 2018). Organoids undergo cytoarchitectural changes, increased cell type diversity, and cell–cell interactions, all of which have been shown to play integral roles in spatial patterning/corticogenesis according to animal models. Despite their promise, organoids are not immune to the pitfalls that surround animal models. Cortical organoids and primary cortical tissue have been shown to harbor differences in cell subtypes, cell type–specific gene-expression patterns, differentiation trajectories, distinct areal identities, and developmental stage (Bhaduri et al., 2020; Tanaka et al., 2020). These differences may be due in part to the in vitro conditions of organoid generation, which can lead to the downregulation of regulators of aerobic respiration and the induction of glycolysis, ER stress, and apoptotic genes (Bhaduri et al., 2020; Pollen et al., 2019; Tanaka et al., 2020). However, cortical organoids can be readily subjected to various culture conditions that may improve their fidelity to primary cortical tissue. For example, liver (Takebe et al., 2013), intestine (Watson et al., 2014), or lung organoids (Dye et al., 2016) have displayed improved maturation upon transplantation into mouse models. This has held true for cortical organoids, which have demonstrated more specific cell subtype specification, more complex cellular morphologies, improved neuronal maturation, and reduced cellular stress (Bhaduri et al., 2020; Mansour et al., 2018). Other protocols have also sought to improve the fidelity of cortical organoid models with culturing at the air-liquid interface (Giandomenico et al., 2019) or exogenous expression of the transcription factor ETV2 to improve vascularization (Cakir et al., 2019). Continued improvements of the cortical organoid system, benchmarked against the molecular and cytoarchitectural profiles of the human cortex, can therefore harness the full potential of cortical organoids as a tractable model of human neurodevelopment.

5.3 |. Invest in an infrastructure of genetic tools and perturbation systems in cortical organoid and non-human primate models

Model organisms have enabled the generation of conceptual frameworks for cortical development due to the extensive array of genetic tools available for these systems. Therefore, developing a similarly comprehensive understanding of human cortical development requires an equivalent infrastructure for in vitro human-derived systems and in vivo primate models. For example, the evolution of cortical organoid systems has paralleled that of targeted and high-throughput perturbational analyses for these cultures, including platforms for lineage tracing of neural progenitors throughout cell fate specification (He et al., 2022), CRISPR-mediated activation of a specific gene target (Ogawa et al., 2018), and high-throughput CRISPR screens to determine essential regulators of cerebral patterning (Fleck et al., 2021). Continued efforts to streamline the genetic manipulation of cortical organoids are an essential step toward their use as an efficient, reliable platform for mechanistic studies of human cortical development.

Further in vivo studies assessing cortical development in a model system more similar to the human brain stand to benefit from nonhuman primate models. However, a widespread adoption of these systems has been limited by their lack of tractability relative to rodents and small mammals (Scott & Bourne, 2021). Nonhuman primates have a slower birth rate and longer lifespan, and genetic manipulation in these systems is not as well established as in smaller mammalian systems. Macaque and marmosets are also larger and therefore more expensive and logistically demanding to maintain, and the cognitive similarity to humans that makes them such an enticing model also necessitates similar ethical considerations as human studies. As such, nonhuman primates present a largely untapped potential for testing conceptual frameworks of cortical development generated from mouse or in vitro studies in an in vivo context that more closely recapitulates the human brain. With further funding to support such studies in macaque and marmoset models, as well as the development of efficient genetic tools and perturbational approaches for use in these nonhuman primates, the field would gain a valuable tool toward bridging the existing gaps in human neuroscience.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our funding sources from the NIH NINDS (4R00NS111731; AB) and NIGMS (T32GM008243; PN) as well as members of the Bhaduri lab for their helpful feedback in the drafting of this manuscript.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Grant/Award Number: R00NS111731; National Institute of General Medical Science, Grant/Award Number: T32GM008243

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Agmon A, Yang LT, O’Dowd DK, & Jones EG (1993). Organized growth of thalamocortical axons from the deep tier of terminations into layer IV of developing mouse barrel cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 13(12), 5365–5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo EA, Chirivella L, Dautzenberg M, Dobreva G, Fariñas I, Grosschedl R, & McConnell SK (2008). Satb2 regulates callosal projection neuron identity in the developing cerebral cortex. Neuron, 57(3), 364–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L, Gaskin PL, Sawiak SJ, Fryer TD, Hong YT, Cockcroft GJ, Clarke HF, & Roberts AC (2019). Fractionating blunted reward processing characteristic of anhedonia by over-activating primate subgenual anterior cingulate cortex. Neuron, 101(2), 307–320.e306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L, Wood CM, Gaskin PL, Sawiak SJ, Fryer TD, Hong YT, McIver L, Clarke HF, & Roberts AC (2020). Over-activation of primate subgenual cingulate cortex enhances the cardiovascular, behavioral and neural responses to threat. Nature Communications, 11(1), 5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Manaye KF, Semendeferi K, Erwin JM, Park S, Goubert V, & Hof PR (2010). The von Economo neurons in frontoinsular and anterior cingulate cortex in great apes and humans. Brain Structure and Function, 214(5), 495–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzu’bi A, Lindsay SJ, Harkin LF, McIntyre J, Lisgo SN, & Clowry GJ (2017). The transcription factors COUP-TFI and COUP-TFII have distinct roles in arealisation and GABAergic interneuron specification in the early human fetal telencephalon. Cerebral Cortex, 27(10), 4971–4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CT, Sheets PL, Kiritani T, & Shepherd GM (2010). Sublayer-specific microcircuits of corticospinal and corticostriatal neurons in motor cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 13(6), 739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M, Avaliani N, Svensson A, Wickham J, Pinborg LH, Jespersen B, Christiansen SH, Bengzon J, Woldbye DP, & Kokaia M (2016). Optogenetic control of human neurons in organotypic brain cultures. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlotta P, Molyneaux BJ, Chen J, Inoue J, Kominami R, & Macklis JD (2005). Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron, 45(2), 207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armentano M, Chou S-J, Tomassy GS, Leingärtner A, O’Leary DD, & Studer M (2007). COUP-TFI regulates the balance of cortical patterning between frontal/motor and sensory areas. Nature Neuroscience, 10(10), 1277–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assimacopoulos S, Kao T, Issa NP, & Grove EA (2012). Fibroblast growth factor 8 organizes the neocortical area map and regulates sensory map topography. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(21), 7191–7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakken TE, Jorstad NL, Hu Q, Lake BB, Tian W, Kalmbach BE, Crow M, Hodge RD, Krienen FM, & Sorensen SA (2021). Comparative cellular analysis of motor cortex in human, marmoset and mouse. Nature, 598(7879), 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA (2008). The mystery and magic of glia: A perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron, 60(3), 430–440. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayatti N, Sarma S, Shaw C, Eyre JA, Vouyiouklis DA, Lindsay S, & Clowry GJ (2008). Progressive loss of PAX6, TBR2, NEUROD and TBR1 mRNA gradients correlates with translocation of EMX2 to the cortical plate during human cortical development. European Journal of Neuroscience, 28(8), 1449–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, & Altman J (1991). Neocortical development (Vol. 1). Raven Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bedogni F, Hodge RD, Elsen GE, Nelson BR, Daza RA, Beyer RP, Bammler TK, Rubenstein JL, & Hevner RF (2010). Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(29), 13129–13134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovskii VK, Nassi JJ, & Born RT (2011). Segregation of feedforward and feedback projections in mouse visual cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 519(18), 3672–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betizeau M, Cortay V, Patti D, Pfister S, Gautier E, Bellemin-Ménard A, Afanassieff M, Huissoud C, Douglas RJ, & Kennedy H (2013). Precursor diversity and complexity of lineage relationships in the outer subventricular zone of the primate. Neuron, 80(2), 442–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaduri A, Andrews MG, Mancia Leon W, Jung D, Shin D, Allen D, Jung D, Schmunk G, Haeussler M, Salma J, Pollen AA, Nowakowski TJ, & Kriegstein AR (2020). Cell stress in cortical organoids impairs molecular subtype specification. Nature, 578(7793), 142–148. 10.1038/s41586-020-1962-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaduri A, Sandoval-Espinosa C, Otero-Garcia M, Oh I, Yin R, Eze UC, Nowakowski TJ, & Kriegstein AR (2021). An atlas of cortical arealization identifies dynamic molecular signatures. Nature, 598(7879), 200–204. 10.1038/s41586-021-03910-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop KM, Goudreau G, & O’Leary DD (2000). Regulation of area identity in the mammalian neocortex by Emx2 and Pax6. Science, 288(5464), 344–349. 10.1126/science.288.5464.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop KM, Rubenstein JL, & O’Leary DD (2002). Distinct actions of Emx1, Emx2, andPax6 in regulating the specification of areas in the developing neocortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 22(17), 7627–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JB, McCutcheon SR, Dube S, Barrera A, Klann TS, Rice GA, Adkar SS, Soderling SH, Reddy TE, & Gersbach CA (2020). Master regulators and cofactors of human neuronal cell fate specification identified by CRISPR gene activation screens. Cell Reports, 33(9), 108460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borello U, Madhavan M, Vilinsky I, Faedo A, Pierani A, Rubenstein J, & Campbell K (2014). Sp8 and COUP-TF1 reciprocally regulate patterning and Fgf signaling in cortical progenitors. Cerebral Cortex, 24(6), 1409–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell V, & Reillo I (2012). Emerging roles of neural stem cells in cerebral cortex development and evolution. Developmental Neurobiology, 72(7), 955–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britanova O, de Juan Romero C, Cheung A, Kwan KY, Schwark M, Gyorgy A, Vogel T, Akopov S, Mitkovski M, & Agoston D (2008). Satb2 is a postmitotic determinant for upper-layer neuron specification in the neocortex. Neuron, 57(3), 378–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K (1909). Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrinde in ihren Prinzipien dargestellt auf Grund des Zellenbaues Barth. [Google Scholar]

- Brüne M, Schöbel A, Karau R, Benali A, Faustmann PM, Juckel G, & Petrasch-Parwez E (2010). Von Economo neuron density in the anterior cingulate cortex is reduced in early onset schizophrenia. Acta Neuropathologica, 119(6), 771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullier J, Kennedy H, & Salinger W (1984). Branching and laminar origin of projections between visual cortical areas in the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 228(3), 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau I, Shepherd GM, & Svoboda K (2004). Precise development of functional and anatomical columns in the neocortex. Neuron, 42(5), 789–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell CR, Bhaduri A, Mostajo-Radji MA, Keefe MG, & Nowakowski TJ (2019). Development and arealization of the cerebral cortex. Neuron, 103(6), 980–1004. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakir B, Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Kural MH, Parent M, Kang Y-J, Chapeton K, Patterson B, Yuan Y, & He C-S (2019). Engineering of human brain organoids with a functional vascular-like system. Nature Methods, 16(11), 1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caronia-Brown G, Yoshida M, Gulden F, Assimacopoulos S, & Grove EA (2014). The cortical hem regulates the size and patterning of neocortex. Development (Cambridge, England), 141(14), 2855–2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casingal CR, Descant KD, & Anton E (2022). Coordinating cerebral cortical construction and connectivity: Unifying influence of radial progenitors. Neuron, 110(7), 1100–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness V Jr., Takahashi T, & Nowakowski R (1995). Numbers, time and neocortical neuronogenesis: A general developmental and evolutionary model. Trends in Neurosciences, 18(9), 379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederquist GY, Azim E, Shnider SJ, Padmanabhan H, & Macklis JD (2013). Lmo4 establishes rostral motor cortex projection neuron subtype diversity. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(15), 6321–6332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvet CJ, Cahalane DJ, & Finlay BL (2015). Systematic, cross-cortex variation in neuron numbers in rodents and primates. Cerebral Cortex, 25(1), 147–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Wang SS, Hattox AM, Rayburn H, Nelson SB, & McConnell SK (2008). The Fezf2–Ctip2 genetic pathway regulates the fate choice of subcortical projection neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(32), 11382–11387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J-G, Rašin M-R, Kwan KY, & Šestan N (2005). Zfp312 is required for subcortical axonal projections and dendritic morphology of deep-layer pyramidal neurons of the cerebral cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(49), 17792–17797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Zhang J-J, Hu G-Y, & Wu C-P (1996). Electrophysiological and morphological properties of pyramidal and nonpyramidal neurons in the cat motor cortex in vitro. Neuroscience, 73(1), 39–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Mukai J, Kvajo M, Xu B, Diamantopoulou A, Pitychoutis PM, Gou B, Gogos JA, & Zhang H (2018). A schizophrenia-related deletion leads to KCNQ2-dependent abnormal dopaminergic modulation of prefrontal cortical interneuron activity. Cerebral Cortex, 28(6), 2175–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S-J, Babot Z, Leingärtner A, Studer M, Nakagawa Y, & O’Leary DD (2013). Geniculocortical input drives genetic distinctions between primary and higher-order visual areas. Science, 340(6137), 1239–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowry GJ, Alzu’bi A, Harkin LF, Sarma S, Kerwin J, & Lindsay SJ (2018). Charting the protomap of the human telencephalon. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology, 73, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coalson TS, Van Essen DC, & Glasser MF (2018). The impact of traditional neuroimaging methods on the spatial localization of cortical areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(27), E6356–E6365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo JA, & Reisin HD (2004). Interlaminar astroglia of the cerebral cortex: A marker of the primate brain. Brain Research, 1006(1), 126–131. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan T, & Burkhalter A (1990). Conserved patterns of cortico-cortical connections define areal hierarchy in rat visual cortex. Experimental Brain Research, 80(1), 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan TA, & Burkhalter A (1993). Hierarchical organization of areas in rat visual cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 13(9), 3749–3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, & Pierce K (2005). Why the frontal cortex in autism might be talking only to itself: Local over-connectivity but long-distance disconnection. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 15(2), 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crino PB (2020). mTORopathies: a road well-traveled. Epilepsy Curr, 20(6_suppl), 64S–66S. 10.1177/1535759720959320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker-Buque A, Brown SM, Kind PC, Isaac JT, & Daw MI (2015). Experience-dependent, layer-specific development of divergent thalamocortical connectivity. Cerebral Cortex, 25(8), 2255–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit J, & Ghosh A (2016). Specification of synaptic connectivity by cell surface interactions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(1), 4–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deck M, Lokmane L, Chauvet S, Mailhes C, Keita M, Niquille M, Yoshida M, Yoshida Y, Lebrand C, & Mann F (2013). Pathfinding of corticothalamic axons relies on a rendezvous with thalamic projections. Neuron, 77(3), 472–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Alonso-Nanclares L, & Arellano JI (2002). Microstructure of the neocortex: Comparative aspects. Journal of Neurocytology, 31(3), 299–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Marco P, Busturia I, & Merchán-Pérez A (1999). Estimation of the number of synapses in the cerebral cortex: Methodological considerations. Cerebral Cortex, 9(7), 722–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Horsburgh G, Berland M, Killackey H, & Kennedy H (1991). The effects of bilateral enucleation in the primate fetus on the parcellation of visual cortex. Brain Research: Developmental Brain Research, 62(1), 137–141. 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90199-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Savatier P, Cortay V, & Kennedy H (2001). Cell-cycle kinetics of neocortical precursors are influenced by embryonic thalamic axons. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(1), 201–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan RN, Bae BI, Cubelos B, Chang C, Hossain AA, Al-Saad S, Mukaddes NM, Oner O, Al-Saffar M, Balkhy S, Gascon GG, Homozygosity Mapping Consortium for Autism, Nieto M, & Walsh CA (2016). Mutations in human accelerated regions disrupt cognition and social behavior. Cell, 167(2), 341–354.e312. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue CJ, Glasser MF, Preuss TM, Rilling JK, & Van Essen DC (2018). Quantitative assessment of prefrontal cortex in humans relative to nonhuman primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(22), E5183–E5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye BR, Dedhia PH, Miller AJ, Nagy MS, White ES, Shea LD, & Spence JR (2016). A bioengineered niche promotes in vivo engraftment and maturation of pluripotent stem cell derived human lung organoids. Elife, 5, e19732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsen GE, Hodge RD, Bedogni F, Daza RA, Nelson BR, Shiba N, Reiner SL, & Hevner RF (2013). The protomap is propagated to cortical plate neurons through an Eomes-dependent intermediate map. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(10), 4081–4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Fink A, Lau C, Pham D, Daza RA, Bulfone A, Kowalczyk T, & Hevner RF (2005). Pax6, Tbr2, and Tbr1 are expressed sequentially by radial glia, intermediate progenitor cells, and postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(1), 247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrard HC, Forro T, & Logothetis NK (2012). Von Economo neurons in the anterior insula of the macaque monkey. Neuron, 74(3), 482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]