Abstract

Due to the non-degradable and persistent nature of metal ions in the environment, they are released into water bodies, where they accumulate in fish. In order to assess pollution in fish, the enzyme, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), has been employed as a biomarker due to sensitivity to various ions. This study investigates the kinetic properties of the G6PD enzyme in yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco), and analyzes the effects of these metal ions on the G6PD enzyme activity in the ovarian cell line (CCO) of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). IC50 values and inhibition types of G6PD were determined in the metal ions Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Cd2+. While, the inhibition types of Cu2+ and Al3+ were the competitive inhibition, Zn2+ and Cd2+ were the linear mixed noncompetitive and linear mixed competitive, respectively. In vitro experiments revealed an inverse correlation between G6PD activity and metal ion concentration, mRNA levels and enzyme activity of G6PD increased at the lower metal ion concentration and decreased at the higher concentration. Our findings suggest that metal ions pose a significant threat to G6PD activity even at low concentrations, potentially playing a crucial role in the toxicity mechanism of metal ion pollution. This information contributes to the development of a biomonitoring tool for assessing metal ion contamination in aquatic species.

Keywords: CCO, Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, Kinetic behavior, Metal ions, Yellow catfish

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Environmental sciences

Introduction

All living organisms depend on metals as essential components, fulfilling three primary functions: providing structural support, acting as enzyme cofactors, and facilitating electron transport1. However, elevated concentrations of metal ions, including low levels of non-essential heavy metals such as Cadmium (Cd), can lead to significant health concerns2. Due to their non-degradable and persistent nature in the environment, metal ions accumulate in aquatic organisms, posing a potential risk to human health as they undergo biological amplification through the food chain3,4. As demonstrated in a previous study, heavy metal pollution in aquatic species has reached critical levels, with the accumulation of metals in the tissues of yellow perch serving as a reflection of local contamination levels5. Furthermore, Chan et al. reported the presence of metal ions in the gills, intestines, and muscles of aquatic organisms in a South China region affected by acid mine drainage6. The impact of heavy metals on fish biochemical parameters, histopathology in various vital organs, and molecular-level DNA alterations are of considerable significance7.

In response to metal ion pollution, identifying contamination markers represents a direct and practical approach to monitoring the safety of aquatic products. The impact of pollutants can be assessed through biochemical reactions, specifically biological or molecular biomarkers8. Biomarkers, encompass physiological and behavioral indicators, respond to exposure to contaminants and their effects9. Fish hematological characteristics are also commonly recognized as a highly suitable experimental model for various biotests and toxicity experiments10. The enzyme Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD, E.C 1.1.1.49), a rate-limiting enzyme, plays a central role in generating ribose and the reducing agent nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) through the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)11. G6PD as a biomarker has been applied in various fields, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and Merkel cell carcinoma prognostic12,13. In the presence of NADP, G6PD catalyzes the conversion of glucose 6-phosphate into 6-phosphogluconate, which has been utilized as a biomarker for pollution-induced carcinogenesis in fish14. G6PD can also stimulate the activation of cytoplasmic nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide kinase (NADK1), producing NADP+ and contributing to the growth of NADPH and NADP+ pools under various oxidative stress conditions15. Previous research has demonstrated the utility of G6PD from earthworm species (Eisenia fetida) for monitoring metal ion contamination in soil ecology16. It has also been observed that certain metal ions can inhibit the activity of G6PD in Capoeta umbla liver and gill tissues17. In a prior study, heavy metal contamination levels were monitored by evaluating immunocytological and cytogenotoxic biomarkers in the gill and haemocyte tissues of green-lipped mussels (Perna canaliculus) in coastal waters18. However, the mechanism underlying the use of G6PD from yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) for determining the extent of metal ion contamination remains unknown. The enzyme kinetics of G6PD from rainbow trout erythrocytes and grass carp hepatopancreas have been studied on numerous heavy metal ions (Ag+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Cu2+)19,20.

Yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) can be used as a species to monitor environmental pollution because of its living environment, wide distribution, sensitivity to various metal ions and the interaction between immune dynamics and environment21. This study delved into the inhibitory effects of heavy metals on G6PD activity both in vitro and cells. In vitro, G6PD was directly extracted from yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) using affinity chromatography. Subsequently, the study examined G6PD enzyme kinetics and the impact of heavy metals on its enzymatic activity. As yellow catfish lack a cell line, channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) ovary (CCO) cells were employed to investigate enzyme activity in a cellular context, given the taxonomic similarity of channel catfish and yellow catfish as both belong to the Siluriformes group. Notably, this research probed the inhibitory effects of various metal ions (Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Cd2+) on enzymatic activity in vitro and within cells. The overarching goal was to provide comprehensive data to support the development of pollution guidelines for aquatic products, specifically focusing on the G6PD enzyme. Furthermore, the study also explored the potential therapeutic implications of G6PD as a target for intervention.

Results

G6PD kinetics properties from yellow catfish liver

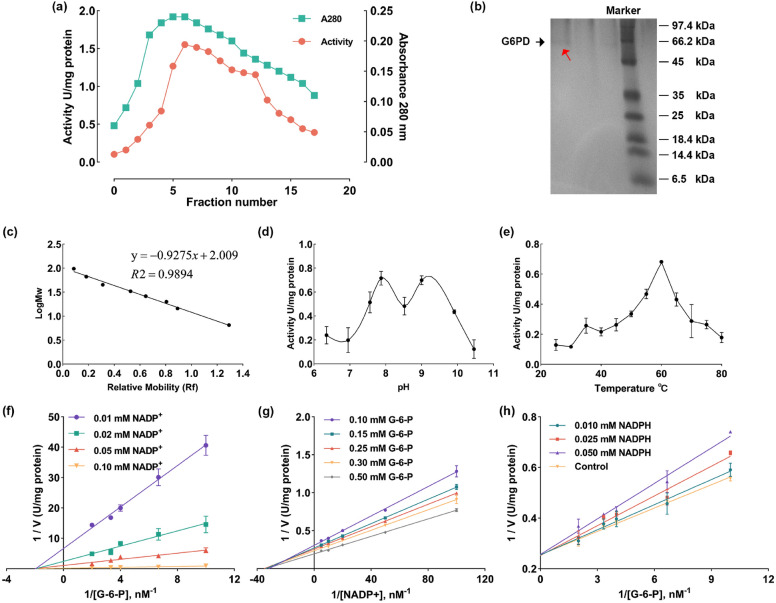

G6PD was eluted using buffer A supplemented with 0.177 mM NADP+ (Fig. 1a). After the purification process, the enzyme exhibited a specific activity of 0.83 U/mg of proteins, resulting in a notable 233.72-fold enhancement in purity (Table 1). The overall yield of the purification process reached approximately 58.24%. Furthermore, the purified G6PD presented a single band on the SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 1b), with a molecular weight (Mr) measured at 68.89 kDa (Fig. 1c). A summary of the purification scheme for G6PD from yellow catfish liver can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Purification and kinetic properties of G6PD isolated from yellow catfish liver. (a) Affinity column elution profile of G6PD. (b) SDS-PAGE photograph of G6PD. Lane 1: purified G6PD (red arrow). Lane 4: standard proteins. (c) G6PD standard molecule weighs Rf-logMw graph. (d) Effect of different pH on G6PD activity. (e) Effect of different temperatures on G6PD activity. (f) The double-reciprocal plot of initial velocity against G-6-P as varied substrate at different fixed NADP+ concentrations for the reaction catalyzed by G6PD from yellow catfish liver. (g) The double-reciprocal plot of initial velocity against NADP+ as varied substrate at different fixed G-6-P concentrations. (h) The double-reciprocal plots of the inhibition of G6PD by NADPH at three different concentrations to determine Ki. The controls show reactions with no inhibitor present.

Table 1.

Purification scheme of G6PD from yellow catfish liver.

| Purification step | Total volume (ml) | Activity (U/ml) | Total activity (U) | Protein (mg/ml) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogenate | 24.750 | 0.014 | 0.347 | 3.897 | 0.004 | 100.000 | 1.000 |

| Supernatant | 18.750 | 0.014 | 0.263 | 1.847 | 0.007 | 73.131 | 2.065 |

| 2ʹ,5ʹ-ADP-Sepharose 4B | 9.500 | 0.021 | 0.200 | 0.025 | 0.831 | 58.243 | 233.718 |

With the increase in pH value, the activity of G6PD increased, and the maximum activity was 0.715 U/mg at pH 7.87. At pH 8.52, the activity thereafter declined. Remarkably, the activity of G6PD increased once more and reached the maximum value of 0.665 U/mg at pH 9.0. Next, as the pH value increased, the enzyme activity reduced (Fig. 1d). In the determination of optimum temperature, the activity of G6PD increased as the temperature rose, peaking at 0.682 U/mg at 60 °C. After that, the activity of G6PD declined as the temperature rose (Fig. 1e).

Figure 1f illustrates the Lineweaver–Burk double-reciprocal plots for G-6-P as the substrate at different NADP+ concentrations. While, under the same G-6-P concentration, with the NADP+ concentration increased, the values of 1/V were decreased, which represented that the maximum Vmax of G6PD appeared in the 0.1 mM NADP+. In contrast, Fig. 1g presents similar plots for NADP+ as the substrate at various G-6-P concentrations. The maximum Vmax of G6PD appeared in the 0.5 mM G-6-P under the same NADP+ concentration. In the results, the points where these lines intersected the horizontal axis indicating a sequential mechanism for the catalytic process facilitated by G6PD in yellow catfish liver.

To investigate how NADPH inhibits G6PD, we employed G-6-P as a substrate and generated Lineweaver–Burk double-reciprocal plots at different NADPH concentrations, as depicted in Fig. 1h. The graph revealed that NADPH competes with 6PGD. The determined Km values for G-6-P and NADP+ were 0.479 mM and 0.029 mM, respectively, while the Vmax value was 2.83 U/ml (Table 2). The dissociation constant Ki for NADPH was calculated to be 0.092 mM.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of G6PD from yellow catfish liver.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| KmG-6-P (mM) | 0.479 ± 0.013 |

| KmNADP+ (mM) | 0.029 ± 0.002 |

| Vmax (U/ml) | 2.830 ± 0.130 |

| KiNADPH (mM) | 0.092 ± 0.001 |

In vitro inhibition assays

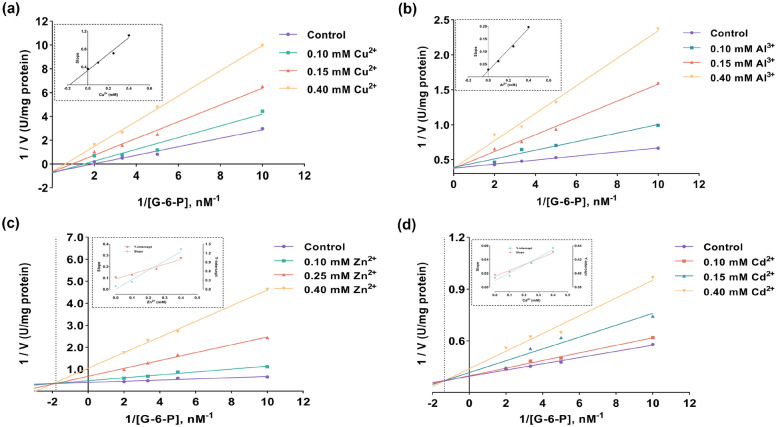

The regression analysis graphs for yellow catfish G6PD, depicting Activity (%) versus metals, are presented in Fig. 2. Based on the data, we calculated the IC50 values for Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ to be 1.718 mM, 1.299 mM, 0.321 mM, and 0.606 mM, respectively (Fig. 2a–d, Table 3). The Ki constants for Cu2+ and Al3+ were determined through Lineweaver–Burk plots, resulting in values of 0.175 mM and 0.056 mM, respectively. Both Cu2+ and Al3+ exhibited competitive inhibition (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 2.

Activity (%) vs metals regression analysis graphs for yellow catfish G6PD in the presence of different metals concentrations (a) Cu2+, (b) Al3+, (c) Zn2+, (d) Cd2+.

Table 3.

In vitro the parameters which metal ions effect G-6-P.

| Metal ions | IC50 (mM) | Ki (mM) | Inhibition type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kis Kii | |||

| Cu2+ | 1.718 | 0.175 | Competitive |

| Al3+ | 1.299 | 0.056 | Competitive |

| Zn2+ | 0.321 | 0.002 0.216 | Linear mixed noncompetitive |

| Cd2+ | 0.606 | 0.186 3.466 | Linear mixed competitive |

Figure 3.

Double-reciprocal plots of the inhibition of 6PGD in yellow catfish by (a) Cu2+, (b) Al3+, (c) Zn2+, (d) Cd2+ at three different concentrations for determination of Ki. The controls show reactions with no inhibitor present.

In the case of Zn2+ and Cd2+, the Ki constants indicated mixed-type inhibition patterns. Replots of the slope (Kis) and intercept (Kii) from the double-reciprocal plots with inhibitor concentration yielded linear plots, suggesting a linear mixed-type inhibition. For Zn2+, the Kis was calculated to be 0.002 mM, and the Kii was 0.216 mM. For Cd2+, the Kis was 0.186 mM, and the Kii was 3.466 mM (Fig. 3c,d).

In cells inhibition assays

Figure 4 demonstrate that for G6PD mRNA expression levels and enzyme activity under the four metal ions various concentration. The highest expression levels of G6PD mRNA were observed in the 0.5 μM group for Cu2+ and Al3+ (p < 0.001), and the lowest expression levels of G6PD mRNA were achieved in the 5.0 μM (Fig. 4a,b). Under the 0.05 μM Zn2+ condiation, the highest levels of G6PD mRNA were achieved (p < 0.001), while the similar results were observed from Cd2+ (p < 0.01). The lowest expression levels of G6PD mRNA were achieved at 0.4 μM in both Zn2+ and Cd2+ groups. This suggests that G6PD is more sensitive to Zn2+ and Cd2+ compared to Cu2+ and Al3+. Interesting, the change intention of four metal ions impact on enzyme activity of G6PD were similar to the expression levels of G6PD mRNA. Among Cu2+, Al3+, and Zn2+, the highest enzyme activity of G6PD were achieved that were correspondence to the G6PD mRNA expression (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4e–g). The Cd2+ group had conversed result, the G6PD activity were similar under the 0.025, 0.05, and 0.1 μM and decreased at 0.2 and 0.4 μM (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4 h). Additionally, it is noteworthy that both G6PD mRNA and activity exhibited an initial increase with the rise in metal concentration, reaching peak levels, then declining as the metal concentration further increased. This indicates that lower metal concentrations promote enzyme activity, while higher metal concentrations inhibit enzyme activity.

Figure 4.

The effect of metal ion on mRNA and activity of G6PD in CCO by QRT-PCR in the presence of different metals concentrations. mRNA of G6PD on (a) Cu2+, (b) Al3+, (c) Zn2+, (d) Cd2+. Activity of G6PD on (e) Cu2+, (f) Al3+, (g) Zn2+, (h) Cd2+. The *, **, and *** represent significant differences with p < 0.05, < 0.01, and < 0.001.

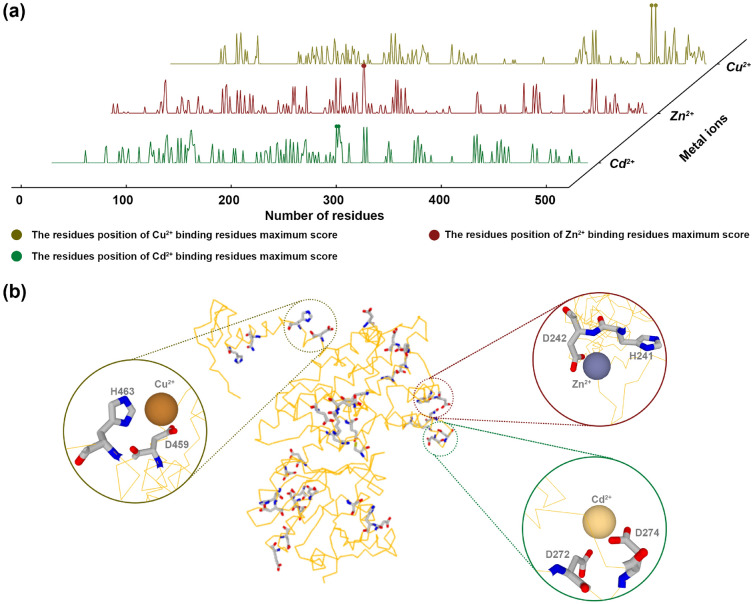

Metal ions with G6PD molecule docking model

In order to better deeply understand the molecular mechanism of metal ions inhibit the G6PD. The metal ions dock G6PD molecular docking model was built using the online Metal Ion-Binding site prediction and modeling server (http://bioinfo.cmu.edu.tw/MIB2/)22. Among the test four metal ions, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ were predicted due to the limitation of the server. The primary accession number for the G6PD sequences, which were acquired from Uniprot, is F1Q883. The maximum score of Cu2+ for the binding residues was 7.523, as expected by the data; Cu2+ may have interacted with aspartic acid at position 459 and histidine at position 463 (Fig. 5a,b, Supplementary Materials Table S1). Likewise, Zn2+ and Cd2+ had the highest scores of 6.020 and 4.519, respectively (Supplementary Materials Table S1). While aspartic acid and histidine will interact with the Zn2+ at positions 242 and 241. Then the Cd2+ interacts with aspartic acid at positions 272 and 274 (Fig. 5a,b).

Figure 5.

Cu2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ docking with G6PD. Score diagram of binding residues of metal ions in G6PD amino acid sequences (a). Schematic diagram of the interaction between Cu2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ and amino acids at the highest score binding residues position (b).

Discussion

A surge in environmental pollution has accompanied the rapid expansion of urbanization and industrialization23. Earlier studies have reported that heavy metal concentrations, particularly for elements such as Hg and Co, were elevated in the groundwater of urban areas compared to non-urbanized regions within the Pearl River Delta24. Additionally, heavy metals were detected in the tissues of aquatic organisms in areas affected by acid mine drainage in southern China6. The persistent and non-degradable nature of metal ions in the environment makes them readily available to aquatic species. This, coupled with their potential for biological amplification within the food chain, raises concerns regarding the potential risks to human health associated with metal ion exposure3,4.

In this study, we aimed to assess the impact of metal ions on G6PD to contribute to developing a biomonitoring tool for evaluating metal ion contamination in aquatic species and establishing standards. The purification of G6PD from yellow catfish liver was achieved through ultracentrifugation and 2ʹ,5ʹ-Sepharose-4B affinity chromatography effectively separated G6PD from 6PGD25. Several organisms have been shown to use similar purification processes for G6PD26,27, due to the highest yield, specific activity, and cost-effective purification technique28. The specific activity of G6PD obtained in our study was measured at 0.83 U/mg protein, and difference from previous reports17,29. The variations in specific activities of G6PD could be attributed to the enzyme's different sources and origins23. Likewise, the G6PD exhibited a molecular weight of 68.89 kDa, which may have two maximum activity values according to the LOWSS linear regression analysis. It is plausible that the G6PD active site harbors multiple ionizable groups30. Additionally, at pH 7.87 and 9.0, the hydrogen ion from the –COOH group may transfer to the –NH2 group, promoting the formation of bonds between the enzyme and substrate and increasing G6PD activity31. Nevertheless, this work did not examine the structural makeup of G6PD from yellow catfish. On the other hand, G6PD may be more thoroughly analyzed using enzymatic fingerprinting, a potential substitute and complement to nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to fully comprehend the impact of the structural composition of G6PD on enzyme activity32.

The kinetic mechanism of G6PD in our study followed an 'Ordered Bi' sequential mechanism, consistent with findings in other animal species33. Notably, the Km values for G6PD and NADP+ that we determined in our research were lower than those reported in rainbow trout34 but higher than the values observed in Aspergillus niger35. Our study revealed that the Km for G6PD was higher than that for NADP+, suggesting that 6PGD has a lower affinity for G6PD compared to NADP+33. This finding contrasts with previous reports where the Km for NADP+ was higher than G6PD36,37. Additionally, our investigation showed that NADPH competitively inhibited G-6-P, with a Ki of 0.092 mM. Similar results were observed in Thermotoga maritime (0.11 mM)38, but these values were higher than those reported in certain microorganisms (where NADPH exhibited competitive inhibition with a Ki of 0.012 mM)27,35,39. Furthermore, we found that NADPH inhibited G6PD in a noncompetitive manner, with a Ki constant of 0.144 mM40. These findings emphasize the metabolic control of G6PD enzyme activity by the cytosolic ratio of free NADP+ to NADPH41.

In our study, we observed a decrease in G6PD enzyme activity with an increase in the concentration of metal ions. This trend is consistent with findings from G6PD isolated from grass carp30. Our results indicated that G6PD is most sensitive to Zn2+ among the tested metal ions in vitro. Based on semi-empirical and qualitative theories, such as Parr and Pearson's soft acid–base (HSAB) principle, the selectivity and specificity of G6PD may have changed42,43. Among the metal ions have the ability to establish robust interactions with protein –SH, –NH, and –COOH groups44, and the metals can form covalent unions with –SH groups45, acting as a soft Lewis base and changing the structure and function of G6PD. Zn2+, Al3+, and Cu2+ from grass carp were comparable to those from our yellow catfish (Cu2+, Al3+, and Zn2+ IC50 values of 1.718 mM, 1.299 mM, and 0.321 mM, respectively)30. However, for Cd2+, a soft Lewis acid, the IC50 value was noticeably lower than grass carp. In terms of inhibition types, we determined that Cu2+ and Al3+ exhibited competitive inhibition, indicating that these metals compete with G-6-P for enzyme binding sites, adversely affecting the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)46. However, the inhibition type for Cu2+ in grass carp was non-competitive30. Both Zn2+ and Cd2+ demonstrated a linear mixed-type inhibition pattern in our study. Zn2+ exhibited competitive inhibition but was different in grass carp30,37. These findings would suggest that there are structural variations between the G6PD of yellow catfish and grass carp and may be attributed to variations in dietary habits and growing environments, resulting in different physiological responses of the same enzyme to the same metal element in different species47.

The mRNA and enzyme activity data reveal that G6PD in CCO (channel catfish ovary cells) exhibits different sensitivities to metal ions compared to the isolated enzymes. The concentrations of heavy metals used in our study closely approximate those found in polluted waters, as referenced in various studies conducted in southeastern Nigeria48, China49, and land-based fish farms in Atlantic Canada50. In our experiments, both mRNA and enzyme activity levels of G6PD initially increased with the rise in metal ion concentration (ranging from 0 to 0.5 μM for Cu2+ and Al3+, and from 0 to 0.05 μM for Zn2+ and Cd2+). Zn2+ and Cd2+ share comparable chemical characteristics, are members of the IIB groups on the periodic table, and are found in metalloproteins in tetrahedral configurations51. This would account for why Zn2+ and Cd2+ have comparable activity in CCO and how they swap places in proteins without affecting G6PD function52, as well both cations may have the same Lewis acid–base capacity. However, the IB and IIIA groups are home to Cu2+ and Al3+, respectively53. The maximal activity of G6PD indicates that the protein responds to both cations similarly. The reason for the early G6PD maximum activity in Zn2+ and Cd2+ solution compared to Cu2+ and Al3+ could be that Zn2+ and Cd2+ have more active polarization in the carbonyl group45. Moreover, cells and organisms require trace amounts of Cu2+, Zn2+, and Al3+ for growth. Additionally, low concentrations of metal ions can stimulate stress responses in cells54 and may promote improved immune capabilities55. However, higher metal ion concentrations negatively impact the organism's immune system56.

Metal ions interact with G6PD via the molecular docking model can better understand the molecular mechanism of metal ions that inhibit G6PD22. According to our predicted results, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ mainly interact with aspartic acid and histidine. Because histidine can be charged or neutral at physiological pH levels, it is particularly well-suited to take part in the reaction process57. Histidine can operate as an acid, alkali, or nucleophile and can also help to stabilize the reaction's intermediate state58. While aspartic acid's side chain is short, which contributes to its relative rigidity and fixed position, which aids in catalysis58. Cu2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ are transition metal ions that interact with the enzyme's surface charge and influence the ionization of certain amino acid residues, and then the structure of the enzyme is altered59. Subsequently, there was a decrease in G6PD activity as the quantity of metal ions increased (ranging from 0.5 to 5.0 μM for Cu2+ and Al3+, and from 0.05 to 0.4 μM for Zn2+ and Cd2+). This could be attributed to the production of reactive singlet oxygen, which can damage DNA and amino acids60. Thus, the antioxidant defense was altered in the organisms61. Due to the limitation of our experimental, the more accurate molecular mechanism of the inhibition of G6PD by four metal ions should be further studied.

Conclusion

In our study, we successfully isolated, purified, and characterized G6PD from yellow catfish liver. We also investigated the effects of metal ions on enzyme mRNA levels and enzyme activity both in vitro and in cells. When compared to other species, most of the parameters we examined, including specific activity, molecular weight, Km, Vm, and Ki, remained relatively consistent in yellow catfish, suggesting a common function in the properties of the protein. However, we did observe some differences, indicating a divergence between yellow catfish and other species. Based on our findings regarding the inhibitory effects of specific metal ions on G6PD, we hypothesize that if these metal elements exceed a certain threshold level, they could pose a hazard to fish and, ultimately, to human health due to consuming of contaminated aquatic species. This concern arises from the non-degradable and long-lasting nature of metal ions in the environment. In assessing metal ion contamination in aquatic species, it is crucial to consider the potential utility of G6PD as both a pollution biomarker and a therapeutic target. G6PD's role in responding to metal ion exposure highlights its significance in understanding and monitoring the impact of environmental pollution on aquatic ecosystems and food safety.

Materials and methods

Fish husbandry and sample collection

2ʹ,5ʹ-ADP-Sepharose 4B was procured from Pharmacia Fine Chemicals in Uppsala, Sweden, while protein markers were sourced from TIANGEN®. Other chemicals, including 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), NADP+, NADPH, Glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P), and all additional reagents, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. in Missouri, USA. The CCO cells were cultured and maintained at 25 °C in MEM (minimal essential medium) supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO).

Liver samples, weighing 4 g per fish, were promptly isolated using sterile forceps on ice. A subset of 20 fish was selected for subsequent analysis.

Purification and properties of liver G6PD

The purification of G6PD from yellow catfish liver was conducted following a previously published procedure26,30,62. The purification process comprised ultracentrifugation and 2ʹ,5ʹ-ADP-Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography and was carried out at a temperature of 4 °C.

Initially, the liver was sliced, and the samples were rinsed with ice-cold saline to eliminate residual blood. Subsequently, the samples were homogenized in a glass-Teflon homogenizer using three volumes of 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (designated as buffer A), which included 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM 2-ME, and had a pH of 7.42. The homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000g for 60 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was applied to a 2ʹ,5ʹ-ADP-Sepharose 4B column that had been pre-equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 50 ml of buffer A, which continued until the final absorbance at 280 nm dropped below 0.01. Elution was performed using 30 ml of 10 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM 2-ME, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.177 mM NADP, and had a pH of 7.42. Flow rates for both washing and equilibration were set at 16.2 ml/h. The purification scheme for G6PD from yellow catfish liver is depicted in Fig. 1A. Fractions 5–10 in Fig. 1A were combined and used as the analyzed sample.

The determination of G6PD activity was conducted at 25 °C by measuring the rate of NADP+ reduction at 340 nm, following the method described by Beutler63. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method, with bovine serum albumin as the reference standard64. SDS-PAGE was carried out to assess enzyme purity and determine the apparent molecular mass of the subunit according to Laemmli's method25,65 and the SDS-PAGE raw image of G6PD was obtained by gel imaging instrument (GenoSens 1850). The standard proteins consist of rabbit phosphorylase b (97,400), bovine serum albumin (66,200), ovalbumin (45,000), lactate dehydrogenase (35,000), rease bap98l (25,000), beta-lactoglobulin (18,400), lysozyme (14,400), and bovine lung bacteriostatic enzyme (6500).

The optimum pH and temperature of determination

The optimum temperature and pH of G6PD activity were determined, respectively. The optimal pH was carried on the 10 mM Tris–HCl, which has a pH range of 6.0–11.0. The 10 μl of the original enzyme was added to 90 μl of a pH-different Tris–HCl buffer for G6PD activity assay. At the optimum pH values, the determination of optimum temperature was carried on between 25 and 80 °C. The LOWESS approach was employed for the linear regression analysis, and the data was represented as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Kinetic studies

To assess the G6PD kinetic parameters Km and Vm, Lineweaver–Burk plots were employed. These plots were generated using five different concentrations of NADP+ (0.01, 0.02, 0.05, and, 0.10 mM) while maintaining a constant concentration of G-6-P. Similarly, experiments were conducted with G-6-P at five different concentrations (0.10, 0.15, 0.25, 0.30, and 0.50 mM) with a fixed NADP+ concentration. All kinetic investigations were conducted at 25 °C and a pH of 7.87. The Km and Vm values were deduced from the Lineweaver–Burk plots by analyzing the respective slopes and intercepts.

Various concentrations of NADPH (0.01, 0.025, and 0.05 mM) were employed to determine Ki values of G6PD pertaining to the inhibitor NADPH. G-6-P was used as a substrate at different concentrations (0.10, 0.15, 0.25, 0.30, and 0.50 mM, respectively). Activity measurements were conducted, and Lineweaver–Burk plots were constructed to determine Ki values and ascertain the inhibition type for NADPH66.

In vitro effects of metal ions

To evaluate how different concentrated metal ions affect G6PD activity. Cu2+ (0, 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, 2.00, and 2.50 mM), Al3+ (0, 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, 2.50, and 3.50 mM), Zn2+ (0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40, and 0.50 mM), and Cd2+ (0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.40, 0.50, and 0.70 mM) were prepared using the salts of CuSO4, Al2(SO4)3, ZnSO4, and CdSO4 that had been diluted to 20 mM with 50 ml pure water. The control cuvette, devoid of any inhibitor, was used as a reference, and its activity was considered 100%. At each concentration, we performed triplicate assessments for each metal ion. An activity-inhibition graph was constructed for each inhibitor, and the concentrations of metal ions resulting in 50% inhibition (IC50) were determined from regression plots.

For each metal ion, we conducted experiments employing three distinct inhibitor doses (0.1, 0.15, and 0.4 mM for Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Cd2+, respectively) to determine Ki values. In these experiments, four concentrations of G-6-P were employed as substrates (0.10, 0.20, 0.30, and 0.50 mM, respectively). All experiments were repeated three times. Lineweaver–Burk plots were generated by comparing 1/V to 1/[S] data. These plots were used to ascertain the type of inhibition and calculate the Ki constant for each metal ion66.

In cells effects of metal ions

To investigate the impact of metal ions on G6PD mRNA and activity in cells, we employed the concentrations that previous studies had reported of Cu2+ and Al3+ (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 μM), Zn2+ and Cd2+ (0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4 μM)30. The cells were cultured in MEM with 10% FBS for 12 h, after which they were washed twice with PBS and then exposed to varying concentrations of the respective metal ions (Cu2+, Al3+, Zn2+, and Cd2+) for a 2-h.

The mRNA levels of G6PD were determined via quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The relative expression ratio was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, and all data were presented regarding relative mRNA expression. G6PD activity was assessed using a G6PD enzyme activity assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, S0189). The activity of the control cuvette, without any inhibitor, was set as 100%. These experiments were conducted in triplicate. Specific primer sequences can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Primer sequences used in the qRT-PCR experiment.

| Gene name | Forward primer (5ʹ–3ʹ) | Reverse primer (5ʹ–3ʹ) |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) | CTGAGAAACCACCCCCTGTG | ACCTCCATTTGTCCGCTTGA |

| β-Actin | CACTGTGCCCATCTACGAG | CCATCTCCTGCTCGAAGTC |

Molecular docking model

Molecular docking model was established using the online Metal Ion-Binding site prediction and modeling server (http://bioinfo.cmu.edu.tw/MIB2/) (version: MIB2). The G6PD sequences were downloaded from Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/) (Primary accession: F1Q883).

Statistical analysis

In this case, data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three replicates. In the analysis of qRT-PCR, the expression of related genes was calculated using the comparative CT method (2−∆∆CT). The Lineweaver–Burk double-reciprocal plots were constructed using GraphPad 9.4.1. The IC50 values were calculated using the Least squares regression methods. Statistical differences between groups were analyzed with One-way ANOVA. The *, **, and *** represent significant differences with p < 0.05, < 0.01, and < 0.001.

Ethical approval

A total of 75 healthy yellow catfish were procured from a local market with an average body weight of 22.6 ± 1.2 g and a body length of 11.0 ± 0.2 cm. These fish underwent a 24-h fasting period before sampling. Subsequently, the fish were euthanized with CO2 asphyxiation. The experiment was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and legislations. The study complied with ARRIVE guidelines. The School of Life and Sciences at Jiangsu University examined and authorized the experiments involving animal participants.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jiangsu University and Guangdong South China Sea Key Laboratory of Aquaculture for Aquatic Economic Animals, Guangdong Ocean University for their assistance in the original data processing and related bioinformatics analysis, and revision of the language.

Author contributions

L.S. and Y.Z. designed the study. L.S. conducted the experiment, performed and collected the data. L.S. and B.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. K.C. and Y.Z. read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by the Grants from Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210747), Nanhai Key Laboratory of Aquaculture Economy Animal Breeding Open Subject (KFKT2019YB09).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-56503-6.

References

- 1.Wang C, Zhang R, Wei X, Lv M, Jiang Z. Metalloimmunology: The metal ion-controlled immunity. Adv. Immunol. 2020;145:187–241. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Y, Costa M. Metals and molecular carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1161–1172. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu YG, et al. Multivariate statistical and GIS-based approach to identify source of anthropogenic impacts on metallic elements in sediments from the mid Guangdong coasts, China. Environ. Pollut. 2012;163:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varol M, Kaya GK, Sünbül MR. Evaluation of health risks from exposure to arsenic and heavy metals through consumption of ten fish species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:33311–33320. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohamed SA, et al. Heavy metal accumulation is associated with molecular and pathological perturbations in liver of Variola louti from the Jeddah Coast of Red Sea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13:20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan WS, et al. Metal accumulations in aquatic organisms and health risks in an acid mine-affected site in South China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2021;43:4415–4440. doi: 10.1007/s10653-021-00923-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahjahan M, et al. Effects of heavy metals on fish physiology—a review. Chemosphere. 2022;300:134519. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valavanidis A, Vlahogianni T, Dassenakis M, Scoullos M. Molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to toxic environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006;64:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topić Popović N, Čižmek L, Babić S, Strunjak-Perović I, Čož-Rakovac R. Fish liver damage related to the wastewater treatment plant effluents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023;30:48739–48768. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-26187-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed I, Reshi QM, Fazio F. The influence of the endogenous and exogenous factors on hematological parameters in different fish species: A review. Aquac. Int. 2020;28:869–899. doi: 10.1007/s10499-019-00501-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang HC, Wu YH, Liu HY, Stern A, Chiu DT. What has passed is prolog: New cellular and physiological roles of G6PD. Free Radic. Res. 2016;50:1047–1064. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2016.1223296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang P, 2022. Construction of a competing endogenous RNA network to analyse glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase dysregulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Nakamura M, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures and chemokine landscape in virus-positive and virus-negative merkel cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022;12:811586. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.811586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osman AGM, Mekkawy IA, Verreth J, Kirschbaum F. Effects of lead nitrate on the activity of metabolic enzymes during early developmental stages of the African catfish, Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2007;33:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10695-006-9111-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, et al. G6PD-mediated increase in de novo NADP(+) biosynthesis promotes antioxidant defense and tumor metastasis. Sci. Adv. 2022;8:eabo0404. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayhan N, Çomaklı V, Adem S, Güler C. Purification and characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Eisenia fetida and effects of some pesticides and metal ions. Turk. J. Biochem. 2020;45:373–380. doi: 10.1515/tjb-2019-0156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirici M, Atamanalp M, Kirici M, Beydemir Ş. Purification of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Capoeta umbla gill and liver tissues and inhibition effects of some metal ions on enzyme activity. Mar. Sci. Technol. Bull. 2020 doi: 10.33714/masteb.709377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandurvelan R, Marsden ID, Gaw S, Glover CN. Waterborne cadmium impacts immunocytotoxic and cytogenotoxic endpoints in green-lipped mussel, Perna canaliculus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013;142–143:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng JL, Luo Z, Zhu QL, Chen QL, Hu W. Differential effects of acute and chronic zinc exposure on lipid metabolism in three extrahepatic tissues of juvenile yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2014;40:1349–1359. doi: 10.1007/s10695-014-9929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen QL, Gong Y, Luo Z, Zheng JL, Zhu QL. Differential effect of waterborne cadmium exposure on lipid metabolism in liver and muscle of yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013;142–143:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra Segaran T, et al. Catfishes: A global review of the literature. Heliyon. 2023;9:e20081. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu CH, et al. MIB2: Metal ion-binding site prediction and modeling server. Bioinformatics. 2022;38:4428–4429. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aralu CC, Okoye PC, Abugu HO, Eboagu NC, Eze VC. Characterization, sources, and risk assessment of PAHs in borehole water from the vicinity of an unlined dumpsite in Awka, Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:9688. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36691-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang G, Zhang M, Liu C, Li L, Chen Z. Heavy metal(loid)s and organic contaminants in groundwater in the Pearl River Delta that has undergone three decades of urbanization and industrialization: Distributions, sources, and driving forces. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;635:913–925. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adem S, Ciftci M. Purification of rat kidney glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and glutathione reductase enzymes using 2',5'-ADP Sepharose 4B affinity in a single chromatography step. Protein Expression Purif. 2012;81:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danişan A, Ceyhan D, Oğüş IH, Ozer N. Purification and characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from rat small intestine. Protein J. 2004;23:317–324. doi: 10.1023/b:jopc.0000032651.99875.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozer N, Bilgi C, Hamdi Ogüs I. Dog liver glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase: Purification and kinetic properties. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Şengezer C, Ulusu N. Three different purification protocols in purification of G6PD from sheep brain cortex. FABAD J. Pharm. Sci. 2007;32:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yilmaz H, Ciftci M, Beydemir S, Bakan E. Purification of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from chicken erythrocytes investigation of some kinetic properties. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2002;32:287–301. doi: 10.1081/pb-120013475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu W, et al. Purification and characterization of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and inhibition effects of several metal ions on G6PD activity in vitro. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2013;39:637–647. doi: 10.1007/s10695-012-9726-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gach J, Olejniczak T, Krężel P, Boratyński F. Microbial synthesis and evaluation of fungistatic activity of 3-butyl-3-hydroxyphthalide, the mammalian metabolite of 3-n-butylidenephthalide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms22147600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wattjes J, et al. Enzymatic production and enzymatic-mass spectrometric fingerprinting analysis of chitosan polymers with different nonrandom patterns of acetylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:3137–3145. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b12561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulusu NN, Tandogan B. Purification and kinetics of sheep kidney cortex glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;143:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciftci M, Ciltas A, Erdogan O. Purification and characterization of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) erythrocytes. Prevent. Vet. Med. 2004;49:327–333. doi: 10.17221/5712-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wennekes LM, Goosen T, van den Broek PJ, van den Broek HW. Purification and characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gener. Microbiol. 1993;139:2793–2800. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciftçi M, Beydemir S, Yilmaz H, Altikat S. Purification of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) erythrocytes and investigation of some kinetic properties. Protein Express. Purif. 2003;29:304–310. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibraheem O, Adewale IO, Afolayan A. Purification and properties of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Aspergillus aculeatus. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;38:584–590. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2005.38.5.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen T, Schlichting B, Schönheit P. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima: Expression of the g6pd gene and characterization of an extremely thermophilic enzyme. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;216:249–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opheim D, Bernlohr RW. Purification and regulation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Bacillus licheniformis. J. Bacteriol. 1973;116:1150–1159. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.3.1150-1159.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ju HQ, Lin JF, Tian T, Xie D, Xu RH. NADPH homeostasis in cancer: Functions, mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:231. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00326-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurbain J, Thommen Q, Anquez F, Pfeuty B. Quantitative modeling of pentose phosphate pathway response to oxidative stress reveals a cooperative regulatory strategy. iScience. 2022;25:104681. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson RG. In: Survey of Progress in Chemistry, Vol. 5*** Arthur FS, editor. Elsevier; 1969. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parr RG, Pearson RG. Absolute hardness: Companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:7512–7516. doi: 10.1021/ja00364a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guerrero Correa M, et al. Antimicrobial metal-based nanoparticles: A review on their synthesis, types and antimicrobial action. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020;11:1450–1469. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.11.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pauza NL, Cotti MJ, Godar L, Ferramola de Sancovich AM, Sancovich HA. Disturbances on delta aminolevulinate dehydratase (ALA-D) enzyme activity by Pb2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Na+, K+ and Li+: Analysis based on coordination geometry and acid-base Lewis capacity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005;99:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.You R, et al. Efficient production of myo-inositol in Escherichia coli through metabolic engineering. Microbial Cell Factories. 2020;19:109. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01366-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mu Y, et al. The localized ionic microenvironment in bone modelling/remodelling: A potential guide for the design of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023 doi: 10.3390/jfb14020056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edet AE, Offiong OE. Evaluation of water quality pollution indices for heavy metal contamination monitoring. A study case from Akpabuyo-Odukpani area, Lower Cross River Basin (southeastern Nigeria) GeoJournal. 2002;57:295–304. doi: 10.1023/B:GEJO.0000007250.92458.de. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lingling H, Zhendong C. Monitoring of heavy metal pollution in water environment of Wuhan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;30:41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lalonde BA, Ernst W, Garron C. Chemical and physical characterisation of effluents from land-based fish farms in Atlantic Canada. Aquac. Int. 2015;23:535–546. doi: 10.1007/s10499-014-9834-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rulísek L, Vondrásek J. Coordination geometries of selected transition metal ions (Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+) in metalloproteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998;71:115–127. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(98)10042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallee BL, Ulmer DD. Biochemical effects of mercury, cadmium, and lead. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1972;41:91–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.41.070172.000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen S, Xue Z, Gao N, Yang X, Zang L. Perylene diimide-based fluorescent and colorimetric sensors for environmental detection. Sensors (Basel) 2020 doi: 10.3390/s20030917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seo DY, et al. Transcriptomic changes induced by low and high concentrations of heavy metal exposure in Ulva pertusa. Toxics. 2023 doi: 10.3390/toxics11070549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qomaruddin, et al. Visible light-driven p-type semiconductor gas sensors based on CaFe(2)O(4) nanoparticles. Sensors. 2020 doi: 10.3390/s20030850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Subramannian S, Philip R. Pharmacological level of copper induces the immune and antioxidant mechanisms of Fenneropenaeus indicus conferring better protection against white spot syndrome virus infection. Aquac. Int. 2012;20:635–647. doi: 10.1007/s10499-011-9492-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radakovic A, DasGupta S, Wright TH, Aitken HRM, Szostak JW. Nonenzymatic assembly of active chimeric ribozymes from aminoacylated RNA oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116840119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartlett GJ, Porter CT, Borkakoti N, Thornton JM. Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:105–121. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sethi BK, et al. Production of α-amylase by Aspergillus terreus NCFT 4269.10 using pearl millet and its structural characterization. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:639. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eremenko AM, Petrik IS, Smirnova NP, Rudenko AV, Marikvas YS. Antibacterial and antimycotic activity of cotton fabrics, impregnated with silver and binary silver/copper nanoparticles. Nanosc. Res. Lett. 2016;11:28. doi: 10.1186/s11671-016-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li X, Ni M, Xu X, Chen W. Characterisation of naturally occurring isothiocyanates as glutathione reductase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35:1773–1780. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2020.1822828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Şentürk M, Ceyhun SB, Erdoğan O, Küfrevioğlu Öİ. In vitro and in vivo effects of some pesticides on glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme activity from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) erythrocytes. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 2009;95:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2009.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beutler E. Red cell metabolism. A manual of biochemical methods. Psychol. Meaningful Verbal Learn. 1984;60:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lineweaver H, Burk D. The determination of enzyme dissociation constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1934;56:658–666. doi: 10.1021/ja01318a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Wang P, 2022. Construction of a competing endogenous RNA network to analyse glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase dysregulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.