Abstract

In the last decade human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) proved to be valuable for cardiac disease modeling and cardiac regeneration, yet challenges with scale, quality, inter-batch consistency, and cryopreservation remain, reducing experimental reproducibility and limiting clinical translation. Here, we report a robust cardiac differentiation protocol that uses Wnt modulation and a stirred suspension bioreactor to produce on average 124 million hiPSC-CMs with >90% purity using a variety of hiPSC lines (19 differentiations; 10 iPSC lines). After controlled freeze and thaw, bioreactor-derived CMs (bCMs) showed high viability (>90%), interbatch reproducibility in cellular morphology, function, drug response and ventricular identity, which was further supported by single cell transcriptomes. bCMs on microcontact printed substrates revealed a higher degree of sarcomere maturation and viability during long-term culture compared to monolayer-derived CMs (mCMs). Moreover, functional investigation of bCMs in 3D engineered heart tissues showed earlier and stronger force production during long-term culture, and robust pacing capture up to 4 Hz when compared to mCMs. bCMs derived from this differentiation protocol will expand the applications of hiPSC-CMs by providing a reproducible, scalable, and resource efficient method to generate cardiac cells with well-characterized structural and functional properties superior to standard mCMs.

Introduction

Numerous cardiac differentiation protocols have been established to differentiate human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) cultured in adherent monolayer (ML)1,2 or three dimensional (3D) suspension3–7 formats. However, generation of high quantity and quality hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) with low functional variability between differentiations has remained challenging. Specific reasons include insufficient quality assessment of hiPSCs8, variability in cardiac differentiation outcomes1,4, and loss of hiPSC-CM functional properties following cryopreservation9. These and other limitations associated with low functional reproducibility (e.g., high cost and low translational value) motivate the development of improved cardiac differentiation protocols with defined benchmarks and consistent functional output from cryopreserved hiPSC-CMs.

Presently, most cardiac differentiation methods are based on programmed activation and then inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway2 (Table S1). Due to its relative simplicity and high efficiency, this strategy became the dominant approach for hiPSC-CM differentiation for disease modeling and therapeutic cardiomyocyte replacement10–14. Typically performed in ML adherent cultures, this method has become the de facto standard for iPSC-CM differentiation. Nevertheless, hiPSC-CM differentiation by Wnt modulation in ML adherent culture has a number of important limitations. ML cultures scale poorly, with culture plate area and labor scaling linearly with cell number. Seeding density is a critical parameter for successful differentiation, and local heterogeneity in cell seeding reduces differentiation efficiency and increases well-to-well variation, causing low reproducibility in differentiation outcomes. Additionally, lack of flow within culture wells results in sub-optimal distribution of nutrients and pH buffering capacity.1 To improve hiPSC-CM purity, genetic reporter-, surface protein-, and lactate-based enrichment methods are often used following cardiomyocyte differentiation, but these purification methods can increase cost, create throughput barriers, or make hiPSC-CMs unsuitable for clinical applications15. While cryopreservation of cells is a critical step that dramatically facilitates design and execution of experiments and clinical translation, cryopreservation of ML-differentiated hiPSC-CMs negatively impacts their contraction, electrophysiology, and drug responses9. The limited scalability, well-to-well variation, and functional impact of cryopreservation combine to create significant barriers to the use of these cells.

To circumvent these limitations, suspension and stirred bioreactor cardiac differentiation protocols have been developed3–7. hiPSC-CMs obtained from suspension culture differentiation have been successfully utilized to model cardiac diseases16–18 or test novel molecular therapeutics19. Previous studies yielded 0.5–2 million hiPSC-CMs per mL for cultures ranging from 2.5 to 1000 ml1,3,4 (Table S1), illustrating the scalability of suspension cultures. However, different hiPSC lines exhibited inconsistent differentiation in previously reported suspension culture protocols4. The morphological, contractile, and electrophysiological properties of suspension and ML differentiated hiPSC-CMs has not been systematically evaluated, particularly after cryopreservation, although metabolic analyses suggested greater maturation of hiPSC-CMs from suspension cultures20.

Here we report an optimized bioreactor-based cardiac differentiation protocol with defined benchmarks enabling applicability to a variety of patient-, gene-edited and commercially available control iPSC lines without further modification and ensuring high quantity (~124 million hiPSC-CMs per 100 ml run) and quality (>90% cTnT+ cells) of generated hiPSC-CMs. We describe protocols for robust cryopreservation and recovery of the bioreactor-derived hiPSC-CMs (referred to as bCMs) and assess their cellular composition via scRNAseq. We evaluated the morphological and functional properties of bCMs and compared them to ML-derived hiPSC-CMs (mCMs). bCMs had greater reproducibility and greater morphological and functional maturity.

Results

Optimized bioreactor differentiation protocol

We modified bioreactor and suspension cardiac differentiation protocols4,5 with goals of improving yield and reproducibility, increasing applicability across diverse iPSC lines, reducing cost, and enabling cryopreservation and recovery of resulting hiPSC-CMs. Our optimized workflow (Fig. 1a and S1a) built on a previously described embryoid body suspension culture protocols4,5 by incorporating the following features: (1) use of quality-controlled master cell banks (MCBs) to ensure consistency of input iPSCs; (2) use of a stirred bioreactor that continuously monitors and adjusts O2, CO2, and pH; (3) use of small molecules rather than growth factors, which are more expensive and vulnerable to lot-to-lot variation, to guide differentiation; (4) optimization of the time point to initiate differentiation by Wnt activation; (5) optimization of the duration of Wnt activation and the timing of Wnt inhibition; and (6) incorporation of controlled freeze and thaw protocols.

Fig. 1: Optimized stirred bioreactor cardiac differentiation protocol.

(a) Schematic representation of the optimized bioreactor cardiac differentiation protocol. (b-c) Characteristics of successful bioreactor cardiomyocyte differentiations. Runs were categorized as failed when they yielded < 90% hiPSC-CMs. hiPSC-CMs with frequency of pluripotency marker SSEA4 by flow cytometry (b) or out of range mean EB diameter (c) had higher likelihood of failure. n=19–25 differentiations. EB diameter analysis at day 0. (d) Spontaneous beating frequency of bioreactor- and monolayer-derived hiPSC-CMs at day 15 (n=number of differentiations; number of EBs or wells: Bioreactor (n=3; 71); Monolayer (n=3; 46). (e-f) hiPSC-CM yield (e) and purity (f) at day 15 of bioreactor or monolayer-directed cardiac differentiation (bioreactor, n=19 differentiations; monolayer, n=7 differentiations). Percentage of cells positive for cardiomyocyte marker cTnT was measured by flow cytometry. (g) Timeline of bioreactor and monolayer cardiac differentiation monitored by GFP fluorescence from a TNNI1-GFP iPSC line (bar: 200 μm). (h-j). qRT-PCR analysis of marker gene expression during bioreactor and monolayer cardiac differentiation. Values are expressed as fold-change compared to bioreactor day 5. ACTN2 (h) marks cardiomyocytes, COL1A1 (i) and COL3A1 (j) mark fibroblasts. n=number of differentiations; number of replicates: Bioreactor (n=2–3; 6–11); Monolayer (n=2–3; 6–11). (k) Quantification of viable hiPSC-CMs after cryo-recovery from bioreactor (n=10) and monolayer (n=3) differentiations. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. b-f,k, Welch’s unpaired t-test. h-j, two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šidákś post-test. MCB, Master cell bank; human induced pluripotent stem cells,hiPSCs; EB, embryoid body; cardiac troponin T, cTnT; CM, cardiomyocyte; BF, bright field.

High quality input iPSCs are critical for successful and consistent differentiation21. Towards that end, we implemented procedures to establish MCBs of quality-controlled iPSCs (see Methods), including karyotyping (Fig. S1b) and mycoplasma testing. To monitor pluripotency of iPSCs input into the differentiation protocol, we measured pluripotency marker SSEA4 by FACS. High differentiation efficiencies (>90% expressing cardiomyocyte marker cardiac troponin T [cTnT]) were correlated with high SSEA4 (>70%) values, and low SSEA4 (<70%) predetermined failed differentiation (<90% cTnT+; Fig. 1b).

As in monolayer differentiation protocols2, we used Wnt activator CHIR99021 rather than growth factors to initiate mesoderm differentiation. We defined the optimal time of CHIR99021 addition based on EB diameter: EBs smaller than 100 μm fell apart upon CHIR incubation, and EBs bigger than 300 μm differentiated less efficiently (<90% cTnT+; Fig. 1c), likely due to inherent diffusion limits of larger EBs (Kempf et al. 2015; Manstein et al. 2021). Therefore our protocol targets CHIR99021 addition when EB diameter reaches 100 μm, which typically occurs at 24 hours.

We found that optimal cardiac differentiation occurs when CHIR exposure is limited to 24 hours, and when Wnt inhibition by addition of IWR-1 follows after an additional 24 hours (Fig. 1a and S1a). In 19 differentiations of 10 different iPSC lines treated with 7 μM CHIR and 5 μM IWR at these time points, we obtained on average ~1.24 million cells per ml (Fig. 1e) with >90% cTnT+ cells (~2.5 hiPSC-CMs/input hiPSC; Fig. 1f) over the course of 15 days. High percentages of cTnT positive cells were further confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis for cardiac markers cTnT and ACTN2 in cryosectioned bioreactor-derived cardiomyocytes (bCMs) at differentiation day 15 (Fig. S2c; Movie S1).

For comparison to bCMs, we used the same hiPSCs (WTC-Cas9) and differentiated them in parallel using the same differentiation protocol, except for a 48 h incubation period with CHIR instead of 24 h (Fig. S1a). Incubation with CHIR for 24 h led to failed ML differentiation. We did not apply hiPSC-CM enrichment methods15 at the completion of either bCM or mCM differentiation protocols. Compared to bCMs, ML-derived cardiomyocytes (mCMs) showed higher spontaneous beating frequency (Fig. 1d; Movie S2, S3), suggestive of lower maturity. Moreover, mCM differentiation resulted in lower cell yields (Fig. 1e) and higher variability in the fraction of cTnT+ cells per differentiation at day 15 (Fig. 1f).

We observed first contractions in bCMs at day 5 of differentiation (Movie S4), versus day 7 in mCMs and day 7 in previous reports of suspension culture hiPSC-CM differentiation1,4–6. To validate this observation, we differentiated hiPSCs in which sarcomere protein TNNI1 is fused to GFP22 in the bioreactor and visualized onset of GFP expression (Fig. 1g). TNNI1-GFP bCMs first expressed GFP at day 5 at the edges of spontaneously formed EBs, in regions that colocalized with areas of contraction. mCMs first showed GFP expression at day 6 (Fig. 1g). However, these GFP+ areas did not visibly contract. We also analyzed the time course of expression of the cardiac sarcomere gene ACTN2. By RT-qPCR, ACTN2 was expressed in day 5 bCMs, whereas its expression level in mCMs did not become comparable until day 7. Additionally, we observed reduced inter-batch variation in ACTN2 levels in bCMs compared to mCMs at days 7–15 (Fig. 1h and Fig. S2d). We also analyzed the expression of fibroblast markers COL1A1 and COL3A1. These mRNAs were expressed at significantly lower levels in day 5 and 6 bCMs, suggesting a higher fraction of non-cardiomyocytes (non-CMs) in mCMs (Fig. 1i,j).

The ability to cryopreserve and recover viable cells that retain functional properties is critical to incorporate large scale differentiation protocols into efficient workflows. To enhance cryopreservation and functional recovery of hiPSC-CMs, we optimized cell dissociation protocols and cryo-protectant media, and achieved controlled rate cell freezing through a dedicated computer-controlled freezer. Our freeze/thaw protocol yielded ~94% viable cells after recovery of bCMs and mCMs from cryopreservation (Fig. 1k). Functional testing of cryo-recovered hiPSC-CMs is discussed in subsequent sections.

Together, we established an integrated bioreactor-based workflow that yields consistently high numbers of highly pure hiPSC-CMs and developed methods for efficient cryo-preservation and cryo-recovery. The following sections further characterize the composition and functional properties of these cells.

Cell composition of bCMs and mCMs

To gain a better understanding of generated cell types and differences between bCMs and mCMs, we performed single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of freshly dissociated hiPSC-CMs at day 15 of differentiation. Using microdroplet technology, we captured a total of 5,173 and 2,513 high quality single cell transcriptomes from bCMs or mCMs, each in biological duplicate. Unsupervised clustering on the most variable genes (Table S2) revealed 11 cell clusters and excellent agreement between biological duplicates (Fig. 2a; Fig. S3a). Based on expression of canonical marker genes, the clusters were identified as CMs (Clusters: 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9), smooth muscle cells (Cluster: 6), non-CMs (Cluster: 3, 7), and endothelial cells (Cluster: 10) (Fig. 2b and S3b). The cardiomyocyte fraction was markedly higher in bioreactor (88%) compared to monolayer (51%) differentiation. We used canonical marker genes to classify the cardiomyocyte clusters. Clusters 0 and 1, highly enriched for ventricular marker genes MYH7 and MYL2, were enriched in bioreactor (67% of cardiomyocytes) compared to monolayer differentiation (44% of cardiomyocytes; Fig. 2c). Conversely, cluster 2, containing cardiomyocytes with high expression of atrial marker genes MYH6 and MYL7, were less frequent in bioreactor (8% of cardiomyocytes) compared to monolayer differentiation (36% of cardiomyocytes). Three cardiomyocyte clusters (4, 5 and 8) actively undergoing cell cycling (Fig. S3c) were present at comparable frequencies among cardiomyocytes (19% bioreactor vs. 16% monolayer). Compared to mCMs, bCMs expressed higher levels of mitochondrial metabolism genes HADHA and ACADVL (Fig. S3d,e), suggesting a higher degree of cardiac metabolic maturation, consistent with a prior report20. Upregulation of these genes was previously associated with a maturation protocol based on the induction of PPARdelta in hiPSC-CMs, which improved functional output23.

Fig. 2: ScRNAseq reveals higher cardiomyocyte content and degree of cellular specification in bioreactor-derived hiPSC-CMs.

(a) ScRNA-seq UMAP clustering of monolayer (ML) and bioreactor-derived hiPSC-CMs (bCMs) showing 11 clusters and their assigned cell types (right). (b) Stacked bar graph showing cellular composition of ML (left) and bCMs (right) expressed in % as parts of whole. Clusters are divided in cardiomyocytes (top) and non-CMs (bottom), whereby the color coding is the same as in panel A, and the order of clusters and the corresponding % are indicated in the table below (b´). (c) Violin-plot showing the relative expression of a subset of cardiac and non-cardiac marker genes (y-axis) across all clusters for bCMs (grey) and mCMs (red) (x-axis). Bioreactor-derived cardiomyocytes, bCMs; Monolayer-derived cardiomyocytes, mCMs; Noncardiomyocytes, non-CMs.

The non-cardiomyocyte fraction was dramatically lower in bioreactor compared to monolayer differentiation (12% vs. 49%; Fig. 2b, b’). An endothelial cell population marked by PECAM1 was uniquely found in bioreactor differentiation (Fig. 2c). ML differentiation was highly enriched for non-cardiomyocyte clusters 3 and 7, which expressed a variety of marker genes for fibroblasts (COL3A1, COL1A1) and neurons (CD24, ENC1) suggesting a mixed or not fully established cellular identity in these cell populations (Fig. 2a, Fig. S3b, Table S2).

Taken together, scRNAseq analysis of cellular composition indicated that bioreactor differentiation yields a higher fraction of hiPSC-CMs, and these hiPSC-CMs have a greater degree of maturation and ventricular identity.

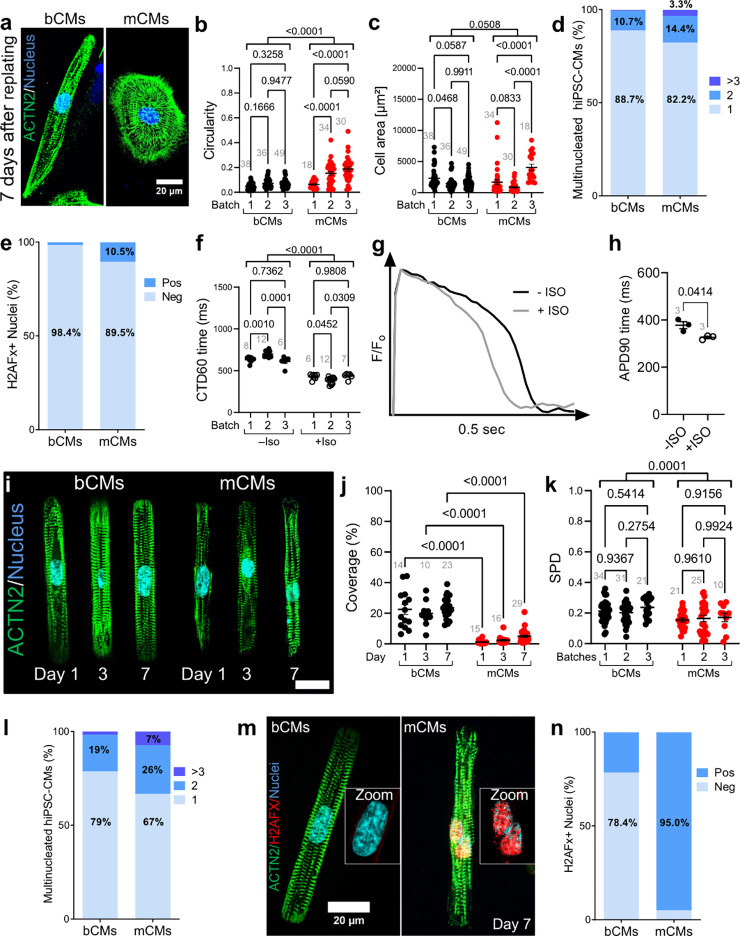

Inter-batch reproducibility of bCMs in morphological and functional 2D assays

For morphological and functional analysis, cryopreserved hiPSC-CMs were thawed and plated at low density in 96-well plates pre-coated with diluted Geltrex (see Methods). After 7 days in culture, unpatterned hiPSC-CMs were fixed and morphologically analyzed. Staining for ACTN2 showed that many bCMs had elongated morphology, reminiscent of the rod shape of mature, de facto human cardiomyocytes. Quantification of bCM circularity confirmed their consistent elongated morphology across multiple batches. In comparison, mCMs displayed greater circularity and higher inter-batch morphological variation (Fig. 3b; Fig. S4a). bCM cell area was not significantly different than mCMs (bCMs: 1752 ± 112.3 μm2; mCMs: 1905 ± 246.6 μm; Fig. S4b), and inter-batch variation in cell area was significantly less than mCMs (Fig. 3c). Measured cell areas were comparable to other hiPSC-CM control lines cultured for 719 and 30 days16,18. Mature, de facto human cardiomyocytes are 80% mononucleated24, and multinucleation tends to increase with cardiac disease10,18,25. Accordingly, both bCMs and mCMs were predominantly mononuclear. However, mCMs had elevated frequency of binucleated or multinucleated cardiac cells (Fig. 3d). Moreover, a greater fraction of mCM nuclei exhibited H2AFx immunoreactivity, a marker of DNA double strand breaks (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3: Comparison of bCMs and mCMs on 2D platforms.

(a-e) Morphological characteristics of unpatterned hiPSC-CMs. Cryo-recovered bCMs and mCMs were cultured for 7 days on unpatterned Geltrex-coated dishes. Cells were stained for sarcomere Z-line marker ACTN2. Representative images (a) illustrate elongated shape of bCMs compared to mCMs. Bar, 20 μm. Circularity (b) and cell area (c) were quantified from 3 independent differentiation batches of bCMs and mCMs. Grey numbers indicate cells analyzed. Two-way ANOVA with Šidákś post-test. (d) Nucleation of unpatterned bCMs (n=178) and mCMs (n=118) after 7 days in culture. Chi-squared p<0.0001. (e) Level of DNA damage response in unpatterned bCMs and mCMs. bCMs (n=63) and mCMs (n=95) were stained for H2AFX, which accumulates as a reaction to DNA double strand breaks. Chi-squared p<0.0001. (f) bCM calcium transients. Unpattered cryo-recovered bCMs were loaded with Ca2+ sensitive dye Fluo-4 and Ca2+ transients were optically recorded during 1 Hz pacing after 4 days of culture. mCMs could not be paced so were excluded. Calcium transient duration at 60% recovery (CTD60) was measured from 3 independent differentiation batches without (filled circles; n=26 wells) and with (open circles; n=13 wells) 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO) after 4 days in culture. Grey numbers indicate number of wells analyzed. Two-way ANOVA with Šidákś post-test. (g-h) bCM action potentials. Unpattered cryo-recovered bCMs were loaded with voltage sensitive dye Fluovolt and optically recorded during 1 Hz pacing after 7 days in culture. g, Representative action potential traces for bCMs without and with (grey line) 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO). h, Quantification of action potential duration at 90% recovery (APD90) for bCMs without (n=3 wells) and with (n=3 wells) 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO). Three separate wells were analyzed per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, paired t-test. (i-k) Characterization of micropatterned bCMs and mCMs. Cryo-recovered cells were plated on single cell extracellular matrix rectangular islands. Samples were fixed at stained after 1, 3, and 7 days in culture. i, Representative images. Bar, 20 μm. (j) Unbiased quantification of bCMs and mCMs coverage of single cell islands. Grey numbers indicate 10x fields analyzed. Two-way ANOVA with Šidákś post-test. (k) Unbiased analysis of sarcomere packing density (SPD) of micropatterned bCMs and mCMs 7 days after replating. Grey numbers indicate cells analyzed. Two-way ANOVA with Šidákś post-test. (l) Nucleation of micropatterned bCMs (n=192) and mCMs (n=60) after 7 days in culture. Chi-squared p<0.0001. (m) Level of DNA damage response in micropatterned bCMs and mCMs. Cells were stained for ACTN2 and H2AFX. m, representative images. Scale bar, 20 μm. (n) Quantification of H2AFx positive and negative nuclei in bCMs (n=51) and mCMs (n=20). Chi-squared p<0.0001. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Bioreactor-derived cardiomyocytes, bCMs; Monolayer-derived cardiomyocytes, mCMs; Isoproterenol, ISO.

Next, we analyzed the physiological properties of bCMs compared to mCMs. We recorded Ca2+ transients by loading hiPSC-CMs with the Ca2+ sensitive dye Fluo-4 and subjecting them to a 10 sec electrical pacing protocol. mCMs failed to follow electrical pacing (1 Hz; n=4 independent differentiation batches) and were therefore excluded from the analysis (Fig. S4c). In contrast, bCMs were reliably captured by the same pacing protocol. Ca2+ transients showed high inter-batch reproducibility and consistent responses to beta-adrenergic stimulation by isoproterenol (Iso) (Fig. 3f; Fig. S4d–h). Time-to-peak calcium transients in bCMs (218.6 ± 8.5 ms) were in agreement with a prior study using fresh and metabolically enriched mCMs derived from control line PGP126. Interestingly, Hamad et al. reported on average 2-fold higher time-to-peak calcium transient times in control mCMs, which is comparable to the disease model studied by Psaras et al., suggesting a lower degree of maturation for mCMs that are not metabolically enriched1,26. Next, we recorded bCM action potentials (APs) by loading cells with Fluovolt, a membrane voltage sensitive dye, and pacing at 1 Hz. bCMs displayed typical ventricular AP morphology (Fig. 3g) 11 days earlier than previously reported for mCMs1, corroborating our scRNAseq findings at day 15 of differentiation (Fig. 2). As expected, adrenergic stimulation with Iso shortened action potential duration (Fig. 3g-h; Fig. S4i–j).

Together, these data indicate that bCMs possess low batch-to-batch variation and robust physiological and morphological cardiomyocyte properties, even after recovery from cryopreservation. In contrast, cryo-recovered mCMs had less mature morphology and could not be electrically paced.

Micropatterned bCMs show a high degree of sarcomere maturation and survival

Plating hiPSC-CMs onto contact printed rectangular extracellular matrix (ECM) islands promotes their structural maturation, including alignment of sarcomeres perpendicular to the cell’s long axis27. We compared bCMs to mCMs after seeding onto rectangular ECM islands with the 7:1 aspect ratio of mature adult human cardiomyocytes. Cells were fixed on day 1, 3 and 7 after plating and stained for cardiac marker ACTN2 (Fig. 3l and S4k–k’). Cell attachment and sarcomere alignment were quantified by unbiased computational image analysis28. bCMs better survived plating on the micropatterned substrates, as demonstrated by their markedly higher coverage at all timepoints compared to mCMs (Fig. 3j; Fig. S4l). Sarcomere packing density and orientation order parameter, two different measures of sarcomere alignment with respect to the cardiomyocyte long axis, were considerably higher in bCMs than in mCMs at all investigated timepoints (Fig. 3k and Fig. S4m,n). Compared to unpatterned cells (Fig. 3d), a greater proportion of patterned bCMs and mCMs were bi- and multinucleated (Fig. 3l). Staining for DNA double strand break marker H2AFX indicated strikingly higher levels in patterned mCMs compared to patterned bCMs (Fig. 3m-n) or to unpatterned cells (Fig. 3e). Additionally, unbiased analysis of nuclear morphology29 identified a significantly higher fraction of nuclei with abnormal morphology in mCMs for all investigated timepoints (Fig. S5a–g). Together, these data indicate that bCMs are more amendable to single cell micropatterning than mCMs, with greater survival and sarcomere assembly, and reduced manifestations of genotoxic stress. Micropatterned substrates increased morphological maturation of bCMs, in line with previous findings on fresh mCMs30,31.

bCMs show high force development and maturity in 3D engineered heart tissues.

3D culture of hiPSC-CMs in fibrinogen gels subjected to anisotropic stress promotes cardiomyocyte maturation and sarcomere organization5,16. These engineered heart tissues (EHTs) also facilitate measurement of cardiomyocyte force development and relaxation. We assembled EHTs using cryopreserved bCMs (Movie S5) and mCMs (Movie S6; Fig. 4a). From days 5 to 32 after EHT casting, we recorded EHTs during spontaneous beating. bCM and mCM EHTs had similar spontaneous beating frequencies (Fig. 4b). bCM EHTs generated greater force than mCM EHTs at all investigated timepoints (Fig. 4c). Force generated by mCM EHTs (~0.108 mN) were consistent with the prior reports for control hiPSC-CMs using the same EHT constructs5,16, whereas bCM EHTs force generation (~0.384 mN) considerably exceeded these prior values. With increasing days in culture, bCM EHTs converged on similar contraction kinetics compared to mCM EHTs, as measured by the 50% contraction time (C50, Fig. 4d), and greater relaxation rates, as measured by the 50% and 90% relaxation time (R50, Fig. S6a; R90, Fig. 4e). Similarly, we recorded EHTs during optogenetic pacing at 1–3 Hz. At any given pacing frequency, bCM EHTs were captured more frequently than mCM EHTs (Fig. S6b). Under all pacing conditions, force was higher in bCMs EHTs compared to mCM EHTs (Fig. S6c), and C50 did not significantly differ between these groups (Fig. S6d). R90 was significantly lower in bCM EHTs at baseline and 2 Hz pacing; at 1 Hz and 3 Hz, bCM EHTs likewise had lower R90 values, although statistical significance was difficult to evaluate due to the low number of mCM EHTs captured at these rates (Fig. S6e). An independent set of EHTs was similarly analyzed with EHTs bathed in Tyrode solution, with similar findings (Fig. 4f-h; Fig. S6f). Under these conditions, both bCM and mCM EHTs generated greater force compared to culture medium, most likely due to higher calcium concentrations in Tyrode solution (bCMs: 0.384 mN vs 0.537 mN, mCMs: 0.108 mN vs 0.177 mN). Furthermore, in Tyrode solution a subset of bCM EHTs was successfully captured at 4 Hz pacing (Fig. S6g–j; Movie S8), notably faster than the previously reported maximal rates achieved for EHTs32–34 without physical conditioning35,36.

Fig. 4: Comparison of 3D engineered heart tissues (EHTs) constructed with bCM or mCMs.

(a) Representative images of EHTs after 29 days in culture (Scale bar, 1 mm). (b-e) Spontaneously beating EHTs assembled from cryo-recovered bCMs or mCMs were recorded in culture medium at 37°C from day 5 to day 32. Analyses of baseline frequency (b), force (c), time to 50% contraction (C50; d) and 90% relaxation (R90; e) showed greater force generation in bCM EHTs. Two-way ANOVA with Šidákś post-test of pooled bCMs and mCMs values for each timepoint. (f-h) Analysis of EHTs in Tyrode solution (f-h) without pacing (0 Hz) or with 1–3 Hz pacing. f, EHT beat frequency in response to pacing. Only EHTs captured by pacing are shown. The percent of EHTs captured at each pacing rate is indicated. Two-way ANOVA with Šidákś post-test. (i) Histological characterization of bCM and mCM EHTs. Cryosections of EHTs after 34 days in culture were stained for sarcomere Z-line protein ACTN2. Representative cryosections (i) showed higher cellularity and greater sarcomere content and organization in bCM EHTs. Sarcomere length (j) was quantified from 33 (bCM) or 35 (mCM) regions of interest from 2 (bCM) or 3 (mCM) EHTs. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Mann-Whitney test. Bioreactor-derived cardiomyocytes, bCMs; Monolayer-derived cardiomyocytes, mCMs.

Given greater force generation by bCMs in EHTs, we stained EHT cross-sections for cardiac sarcomere proteins ACTN2 and cTnT. Consistent with the physiological data, we found greater sarcomere density in bCM compared to mCM EHTs (Fig. 4i). Furthermore, bCM sarcomere length was higher in bCMs compared to mCMs EHTs (1.7 vs 1.6 μm; Fig. 4j), indicating greater maturity of bCMs. Overall, greater function of bCMs EHTs might be explained by the greater hiPSC-CM density, formation of more homogeneous tissue, and greater maturity including expression of metabolic genes HADHA and ACADVL, which have been previously associated with improved contractility in EHTs23.

Discussion

Although cardiac differentiation protocols have been continuously improved over the past decade, current commonly used protocols suffer from limited scalability, high cost, inter-batch and even inter-well variation in efficiency and structural and functional properties, and loss of key functional properties upon recovery from cryopreservation1,3–7,37 (Table S1). These issues have presented substantial practical hurdles to performing reproducible and rigorous research using hiPSC-CMs. As a result, labs relying on these cells invest considerable resources in their continuous culture and differentiation and accounting for well and batch effects. Prior suspension culture and bioreactor protocols offered a potential solution with improved reproducibility and scalability, yet lacked robust methods for cryo-recovery, and the functional properties of the resulting cells were uncharacterized. Here we present a lower-cost bioreactor-based cardiac differentiation protocol (~$569 per bioreactor run yielding ~124 million hiPSC-CMs, compared to ~$1075 for ML differentiation with comparable yield, exclusive of manpower; Table S3) with defined benchmarks and controlled freeze/thaw procedures. We extensively characterized the resulting bCMs and demonstrated that they have robust structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes, reduced batch-to-batch variation, and greater force production in EHTs than previously described5,16–18,32–34,36. These levels of force were comparable to EHTs that underwent physical conditioning of increasing intensity35. Our hiPSC-CM bioreactor differentiation and cryopreservation pipeline and the subsequent deep morphological and functional characterization of bCMs provides a scalable and reproducible hiPSC-CM platform to enable subsequent disease modeling and therapeutic cardiomyocyte replacement.

We adapted the use of MCBs, small molecules, and optimized time points for Wnt activation and inhibition to increase efficiency in cardiac differentiation and reduced inter-batch variability. The success of this adaptation was reflected by first contractions observed as early as day 5 using our protocol (Movie S4), 2–3 days earlier than other protocols1–5. Spinner-3 and shaker-based differentiations7 reported higher yields of 1.5 to 2 million hiPSC-CMs per mL, but these approaches lack reproducibility in differentiation outcomes3, which were significantly improved by adding metabolic selection to the shaker-based protocol7. It has recently been shown that perfusion in the bioreactor enables high density hiPSC cultivation38. Our protocol might be further improved by applying perfusion and metabolic selection to increase yields and purities of generated hiPSC-CMs, respectively. Additionally, we optimized freeze/thaw procedures by utilizing a controlled rate freezer and serum-free freezing reagents5,9. All of these adaptations led to efficient cryo-recovery of bCMs with increased overall maturity and reproducible morphology, calcium transient durations and drug responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Feng Xiao for providing hiPSCs for cardiac differentiation and Suellen Lopes Oliveira for assistance in graphic design.

Funding Support

WTP and KKP were supported by the NCATS Tissue Chips Consortium (UH3 HL141798 and UH3 TR003279) and by charitable support from the Boston Children’s Heart Foundation. WTP and MP were supported by funding from Additional Ventures.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Hamad S. et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in 2D monolayer and scalable 3D suspension bioreactor cultures with reduced batch-to-batch variations. Theranostics 9, 7222–7238 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lian X. et al. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat. Protoc. 8, 162–175 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen V. C. et al. Development of a scalable suspension culture for cardiac differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 15, 365–375 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempf H., Kropp C., Olmer R., Martin U. & Zweigerdt R. Cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells in scalable suspension culture. Nat. Protoc. 10, 1345–1361 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breckwoldt K. et al. Differentiation of cardiomyocytes and generation of human engineered heart tissue. Nat. Protoc. 12, 1177–1197 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halloin C. et al. Continuous WNT Control Enables Advanced hPSC Cardiac Processing and Prognostic Surface Marker Identification in Chemically Defined Suspension Culture. Stem Cell Reports 13, 366–379 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn-Krell A. et al. Bioreactor Suspension Culture: Differentiation and Production of Cardiomyocyte Spheroids From Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9, 674260 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assou S., Bouckenheimer J. & De Vos J. Concise Review: Assessing the Genome Integrity of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: What Quality Control Metrics? Stem Cells 36, 814–821 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J. Z. et al. Effects of Cryopreservation on Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes for Assessing Drug Safety Response Profiles. Stem Cell Reports (2020) doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosqueira D. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing in human pluripotent stem cell-cardiomyocytes highlights arrhythmias, hypocontractility, and energy depletion as potential therapeutic targets for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 39, 3879–3892 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S.-J. et al. Insights Into the Pathogenesis of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia From Engineered Human Heart Tissue. Circulation 140, 390–404 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X. et al. Increased Reactive Oxygen Species–Mediated Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II Activation Contributes to Calcium Handling Abnormalities and …. Circulation (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong J. J. H. et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature 510, 273–277 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burridge P. W. et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 11, 855–860 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ban K., Bae S. & Yoon Y.-S. Current Strategies and Challenges for Purification of Cardiomyocytes Derived from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Theranostics 7, 2067–2077 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prondzynski M. et al. Disease modeling of a mutation in α-actinin 2 guides clinical therapy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. EMBO Mol. Med. e11115 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuello F. et al. Impairment of the ER/mitochondria compartment in human cardiomyocytes with PLN p.Arg14del mutation. EMBO Mol. Med. 13, e13074 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zech A. T. L. et al. ACTN2 Mutant Causes Proteopathy in Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Cells 11, 2745 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prondzynski M. et al. Evaluation of MYBPC3 trans-Splicing and Gene Replacement as Therapeutic Options in Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 7, 475–486 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correia C. et al. 3D aggregate culture improves metabolic maturation of human pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 115, 630–644 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibamiya A. et al. Cell Banking of hiPSCs: A Practical Guide to Cryopreservation and Quality Control in Basic Research. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 55, e127 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts B. et al. Fluorescent Gene Tagging of Transcriptionally Silent Genes in hiPSCs. Stem Cell Reports 12, 1145–1158 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wickramasinghe N. M. et al. PPARdelta activation induces metabolic and contractile maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Cell Stem Cell 29, 559–576.e7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derks W. & Bergmann O. Polyploidy in Cardiomyocytes: Roadblock to Heart Regeneration? Circ. Res. 126, 552–565 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vliegen H. W., van der Laarse A., Cornelisse C. J. & Eulderink F. Myocardial changes in pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy. A study on tissue composition, polyploidization and multinucleation. Eur. Heart J. 12, 488–494 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Psaras Y. et al. CalTrack: High-Throughput Automated Calcium Transient Analysis in Cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 129, 326–341 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bray M.-A., Sheehy S. P. & Parker K. K. Sarcomere alignment is regulated by myocyte shape. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 65, 641–651 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasqualini F. S., Sheehy S. P., Agarwal A., Aratyn-Schaus Y. & Parker K. K. Structural phenotyping of stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Reports 4, 340–347 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filippi-Chiela E. C. et al. Nuclear morphometric analysis (NMA): screening of senescence, apoptosis and nuclear irregularities. PLoS One 7, e42522 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feaster T. K. et al. Matrigel Mattress: A Method for the Generation of Single Contracting Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 117, 995–1000 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H. et al. Modelling diastolic dysfunction in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. Eur. Heart J. (2019) doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saleem U. et al. Force and Calcium Transients Analysis in Human Engineered Heart Tissues Reveals Positive Force-Frequency Relation at Physiological Frequency. Stem Cell Reports 14, 312–324 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L. et al. Generation of high-performance human cardiomyocytes and engineered heart tissues from extended pluripotent stem cells. Cell Discov 8, 105 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feyen D. A. M. et al. Metabolic Maturation Media Improve Physiological Function of Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 32, 107925 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronaldson-Bouchard K. et al. Author Correction: Advanced maturation of human cardiac tissue grown from pluripotent stem cells. Nature 572, E16–E17 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen S. et al. Physiological calcium combined with electrical pacing accelerates maturation of human engineered heart tissue. Stem Cell Reports 17, 2037–2049 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lian X. et al. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, E1848–57 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manstein F. et al. High density bioprocessing of human pluripotent stem cells by metabolic control and in silico modeling. Stem Cells Transl. Med. (2021) doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandegar M. A. et al. CRISPR Interference Efficiently Induces Specific and Reversible Gene Silencing in Human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell 18, 541–553 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G. et al. Efficient, footprint-free human iPSC genome editing by consolidation of Cas9/CRISPR and piggyBac technologies. Nat. Protoc. 12, 88–103 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaaf S. et al. Human engineered heart tissue as a versatile tool in basic research and preclinical toxicology. PLoS One 6, e26397 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas L. S. V. & Gehrig J. Multi-template matching: a versatile tool for object-localization in microscopy images. BMC Bioinformatics 21, 44 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vandenburgh H. et al. Drug-screening platform based on the contractility of tissue-engineered muscle. Muscle Nerve 37, 438–447 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.