Abstract

Protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt is implicated in survival signaling in a wide variety of cells including fibroblasts and epithelial and neuronal cells. We and others have described a linear survival signaling cascade used by insulinlike growth factor I (IGF-I) that consists of the IGF-I receptor, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3 kinase), Akt, and Bad. Activation of this pathway can be sufficient to protect cells from apoptosis. However, previous work had not determined whether this pathway is invariably necessary for protection from apoptosis or whether there are alternative survival signaling pathways. In this communication, we report the existence of two survival signaling pathways, one dependent on PI3 kinase and Akt and the other independent of these enzymes. We found that survival signaling initiated by IGF-I treatment of Rat-1 cells could be blocked by overexpression of a dominant negative kinase-deficient Akt (K179A) as well as by wortmannin. This demonstrates a survival signaling pathway dependent on PI3 kinase and Akt. However, when IGF-I receptors were overexpressed in a Rat-1 background (RIG cells), an alternative pathway became apparent, in which survival mediated by IGF-I was no longer sensitive to wortmannin or to overexpression of dominant negative Akt, even though Akt activation and Bad phosphorylation were still wortmannin sensitive. Experiments with inhibitors of RNA synthesis showed that transcriptional activation is dispensable for this alternative PI3 kinase/Akt-independent survival signaling. These findings demonstrate the existence of a new survival signaling pathway independent of PI3 kinase, Akt, and new transcription and which is evident in fibroblasts overexpressing the IGF-I receptor.

The last several years have seen remarkable advances in understanding the machinery of apoptosis and the factors initiating the cascade of events leading to apoptotic cell death (7). In contrast, only recently has equivalent attention been paid to the ways that the probability of apoptosis is regulated in response to cellular physiology. Although it has been known for some time that cytokines and growth factors such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-3, nerve growth factor, and insulinlike growth factor I (IGF-I) promote survival in various experimental cell systems, it was not clear which signaling pathways were used by these agents (3). One of the first reports on survival signaling connected activation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade with survival in PC-12 cells (44). Another signaling pathway requiring phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3 kinase) activity was associated with antiapoptotic signaling in neurons, fibroblasts, and hematopoietic cells (30, 45, 46). Subsequently, the serine/threonine kinase protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt was identified as a downstream component of survival signaling through PI3 kinase (11, 17–19, 24). Recently Bad, a proapoptotic member of the bcl-2 family, was found to be a substrate of Akt, identifying an intersection point of pro- and antiapoptotic regulatory cascades (8, 9).

Previously, we reported that PI3 kinase activity is necessary for antiapoptotic signaling by IGF-I and that overexpression of mutationally activated PI3 kinase or Akt is sufficient to protect cells from UV-induced apoptosis (24). Here we present evidence that kinase-deficient Akt (K179A) can interfere with IGF-I-mediated survival, showing that the activity of Akt also is necessary for antiapoptotic signaling by IGF-I. However, when IGF-I receptors were overexpressed, the protective signal initiated by IGF-I could no longer be attenuated by the PI3 kinase inhibitors or by overexpression of dominant negative Akt. This revealed the existence of a novel survival pathway independent of PI3 kinase and Akt that becomes more evident when IGF-I receptors are overexpressed. Bad seems not to be the target of this pathway, since its phosphorylation remains wortmannin sensitive even under conditions of IGF-I receptor overexpression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA constructs and cell lines.

Cells and IGF-I receptor constructs were as described previously (34). Vectors expressing HA-Akt (wild-type, kinase-dead, and constitutively active forms) were generously provided by Anke Klippel, Chiron Inc., Emeryville, Calif. Bad constructs were as described previously (8).

Antibodies and other reagents.

Antibodies were from the following sources: anti-ERK-2 from Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.; anti-phospho-p38/HOG1 from New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.; Texas red-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine; antibodies against p70S6 kinase from Kenneth Coker and Thomas Sturgill, University of Virginia; and phospho-Bad-specific antibodies (recognizing phosphoserine 136) from Sandeep Datta and Michael Greenberg, Harvard. Rabbit antibodies against phospho-MAP kinase were produced in this laboratory against a phosphopeptide corresponding to the MAP kinase phosphorylation site.

Chemicals and reagents (unless specified) were from Sigma, St. Louis, Mo. Tissue culture media and reagents were from GIBCO, Gaithersburg, Md., and IGF-I was a gift from Thomas Sturgill. α-Amanitin was from Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind., and rapamycin was from Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.

Protein kinase assays.

In vitro kinase assays for extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity and protein analysis were as described previously (24). Akt activity was assayed as follows. Cells transfected with HA-Akt constructs were starved for 6 to 12 h in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and treated with inhibitors for 15 min; this was followed by addition of growth factors if required. After incubation for 15 min at 37°C, dishes with cells were placed on ice and lysed in NLB (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM HEPES supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors). Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatants were equalized for protein concentration (usually 1 mg/ml) by the addition of NLB. 12CA5 antibodies prebound to protein G-agarose beads (15 μg per 30 μl of beads) were used for immunoprecipitation of HA-tagged proteins. After 2 to 3 h of rotation at 4°C, the beads were washed once each with NLB, NLB plus 0.5 M LiCl, and NLB and twice each with 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM MnCl2. Kinase reactions were performed as described previously (20).

Apoptosis.

Induction and detection of apoptosis were as described previously (24). Experiments in which apoptosis was induced by serum starvation were performed as follows. Cells (4 × 105 cells per 6-cm dish) were grown for at least 12 h in DMEM–10% calf serum, starved for 12 h in DMEM–0.2% calf serum, and then changed to serum-free DMEM. Inhibitors were added at this point, and growth factors were added after 15 to 30 min.

In Cos cells, apoptosis was quantitated by measuring caspase-3 activity with the fluorometric substrate Ac-DEVD-Afc (UBI or Bio-Rad) as specified by the manufacturer.

32P labeling.

At 12 h after transfection with HA-Bad constructs, cells were put in phosphate- and serum-free (PSF) medium for 1 h and then labeled for 5 h in PSF medium containing 0.5 mCi of 32P-orthophosphate per ml. When the labeling was finished, the cells were incubated for 15 min in PSF medium–200 nM wortmannin and IGF-I was added to a final concentration of 250 ng/ml for another 20 min. The cells were lysed on ice, and immunoprecipitation was done as described for HA-Akt kinase assays, except that the last two washes were with NLB.

RESULTS

Activation of Akt correlates with and is necessary for survival signaling by IGF-I.

Although the serine/threonine kinase PKB/Akt was recently shown to be activated by IGF-I and to be sufficient to protect cells from proapoptotic insults, the existence of other survival signaling pathways was not excluded. In particular, MAP kinase activation has also been suggested to be antiapoptotic in differentiating PC-12 cells (44). To examine the relationship between activation of Akt, MAP kinase, and survival signaling, we treated Rat-1 and Cos cells either with IGF-I, which activates Akt, or with epidermal growth factor (EGF) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), which are very effective activators of MAP kinase. Figure 1 demonstrates that EGF and PMA failed to activate Akt or to provide protection from UV-induced apoptosis in Rat-1 and Cos cells, respectively. In contrast, IGF-I was able to activate Akt and protect against apoptosis in both types of cells (Fig. 1). Thus, in this system, survival signaling correlates with activation of Akt and is unrelated to activation of MAP kinase.

FIG. 1.

Akt activation correlates with the ability of IGF-I to protect from apoptosis. (A) Rat-1 fibroblasts were transfected with HA-Akt cDNA. At 32 h later, the cells were serum starved for 16 h and 100 ng of EGF or IGF-I per ml was added for 15 min. Then the cells were lysed and HA-Akt immunoprecipitated, and kinase assays were performed as described previously (24). The presence of equal amounts of HA-Akt in the kinase reaction was verified by blotting with 12CA5 anti-HA antibody. A 25-μg portion of the cell lysate was probed with phosphospecific anti-ERK antibodies to demonstrate the signaling activity of EGF. (B) Rat-1 cells were irradiated for 1 min with UVB, and IGF-I or EGF was added afterwards. At 15 h later, the percentage of apoptotic cells was measured by propidium iodide staining followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis as described previously (24). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (C) IGF-I but not PMA can activate Akt in Cos cells. Akt activation was assayed as in panel A. Cell lysates were probed with phosphospecific anti-ERK antibodies to demonstrate the ability of IGF-I and PMA to activate ERK. Wortm, wortmannin. (D) IGF-I but not PMA protects Cos cells from UV-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis in Cos cells was induced as described for Rat-1. LY294002 (30 μM) was added immediately after irradiation, followed by IGF-I (0.5 μg/ml) or PMA (200nM) 15 min later. At 12 h after apoptosis induction, cells were collected and lysed, and apoptosis was assessed by measuring the caspase activity in lysates containing 100 μg of protein.

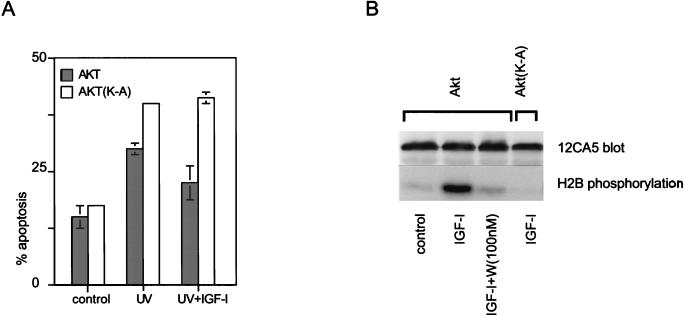

To determine whether Akt activation was necessary for IGF-I-induced survival signaling, we examined the consequences on this signaling of overexpressing kinase-deficient Akt (K179A) in Cos cells. Cells expressing Akt (K179A) were no longer protected by IGF-I (Fig. 2A), implying that Akt activation not only is sufficient but also is necessary for survival signaling utilized by IGF-I. This is consistent with a single linear survival pathway downstream from PI3 kinase and going through Akt.

FIG. 2.

Kinase-deficient Akt blocks the antiapoptotic effects of IGF-I. (A) Cos cells were transfected with HA-Akt and the kinase-deficient mutant HA-Akt(K179A). At 36 h later, the cells were irradiated with UVB and IGF-I (250 ng/ml) was added. After an additional 6 h, the cells were fixed with formaldehyde. The cells were stained for HA expression and subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-fluorescein nick end labeling assays, and the frequency of apoptosis in cells expressing Akt constructs was estimated by counting at least 500 cells in randomly chosen fields. Similar results were obtained in three independent transfections. Differences in apoptosis levels between cells expressing HA-Akt in the presence and absence of IGF-I were statistically significant (P < 0.005), while no IGF-I-mediated protection was observed in cells expressing HA-Akt(K179A). (B) Activation of Akt in Cos cells by IGF-I. Cos cells transiently expressing HA-Akt were pretreated with 100 nM wortmannin (W) for 15 min and then stimulated for another 15 min with 250 ng of IGF-I per ml. Then the cells were lysed, HA-Akt was immunoprecipitated, and kinase assays with histone H2B used as a substrate were done as described previously (24).

Overexpression of IGF-I receptors renders survival signaling wortmannin independent.

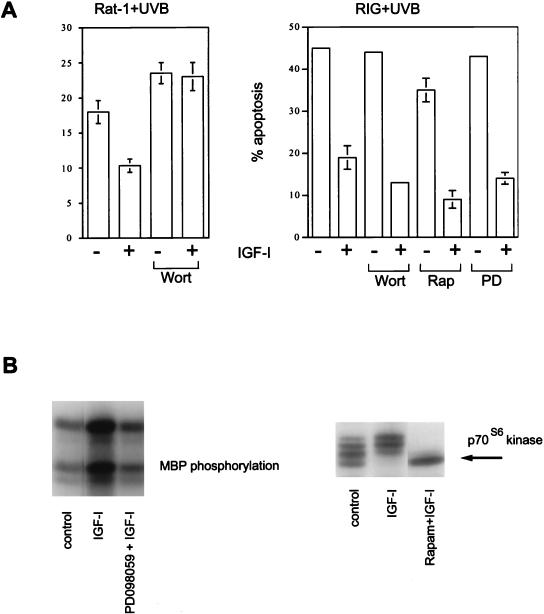

In Rat-1 fibroblasts and Cos cells expressing physiological levels of IGF-I receptor, survival signaling by IGF-I is wortmannin sensitive, arguing for an essential role of PI3 kinase (24). Thus, when Rat-1 cells were pretreated with wortmannin, IGF-I failed to protect them from apoptosis (Fig. 3A, left). However when IGF-I receptors were overexpressed in a Rat-1 background (RIG cells), IGF-I-mediated survival became largely insensitive to wortmannin (Fig. 3A, right) (although in some experiments wortmannin was able to partially attenuate the protection provided by IGF-I).

FIG. 3.

Survival signaling from overexpressed IGF-I receptors is wortmannin independent. (A) RIG cells overexpressing IGF-I receptors and parental Rat-1 fibroblasts were irradiated with UVB, and 100 nM wortmannin (Wort), 10 nM rapamycin (Rap), or 50 μM PD098059 (PD) was added. IGF-I was added to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml 15 min later. After 15 h, the cells were stained with propidium iodide and apoptosis was quantified by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. (B) Inhibition of MAP kinase activation by PD098059 and p70S6 kinase by rapamycin. RIG cells were serum starved for 12 h and pretreated with inhibitors for 15 min, and IGF-I was added. The cells were lysed 15 min later. MAP kinase activity was determined in kinase assays as described previously (38). Activation of p70S6 kinase was detected by observing the electrophoretic mobility shift on Western blots. MBP, myelin basic protein; Rapam, rapamycin.

As in the case with Rat-1 fibroblasts, rapamycin (10 nM) and PD098059 (50 μM) did not affect IGF-I-mediated protection in RIG cells (Fig. 3A, right), confirming our previous result that neither MAP kinase nor p70S6 kinase is involved in antiapoptotic signaling induced by IGF-I (24). To confirm that PD098059 is biologically active in RIG cells, we demonstrated that it can inhibit the activation of MAP kinase by IGF-I (Fig. 3B, left). Similarly, the activity of rapamycin was confirmed by its ability to inhibit an IGF-I-induced mobility shift of p70S6 kinase (Fig. 3B, right). It is noteworthy that in mouse embryo fibroblasts, late passages of Rat-1, and HER (Rat-1 cells overexpressing human EGF receptors), protection of cells by IGF-I was partially resistant to wortmannin, indicating that the wortmannin-insensitive component of survival signaling through IGF-I receptors can be manifested even when the receptors are not overexpressed (data not shown).

RIG cells have an increased sensitivity to serum deprivation.

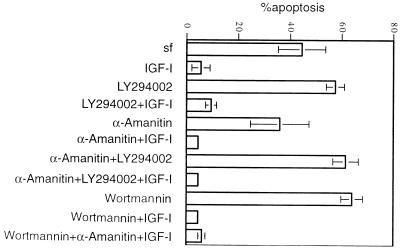

In the method we routinely used for induction of apoptosis, cells were serum starved for 12 h and then irradiated with UV radiation. In contrast to the parental Rat-1 fibroblasts, cultures of RIG cells deprived of serum displayed significant amounts of apoptosis even without UV irradiation. Therefore, in RIG cells the apoptosis observed after UV irradiation was in fact due to a combined effect of serum deprivation and UV irradiation. We suspected that this complexity could underlie the variable sensitivity of IGF-I-induced protection to PI3 kinase inhibitors. To test this, we used serum deprivation as the sole inducer of apoptosis in RIG cells and found that the reproducibility of the experiments improved significantly. When apoptosis in RIG cells was induced by serum deprivation, IGF-I-mediated survival was clearly insensitive to the PI3 kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

PI3 kinase- and Akt-independent survival signaling does not require new transcription. RIG cells were starved for 12 h in DMEM–0.2% calf serum and then for 14 h in serum-free (sf) DMEM. Inhibitors (20 mM LY294002, 200 nM wortmannin, 20 μg of α-amanitin per ml) were added immediately after the cells were placed in serum-free DMEM, and IGF-I was added 30 min later. After 14 h, the cells were stained with propidium iodide, and apoptosis was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis.

Requirement of new transcription for PI3 kinase-independent survival signaling.

To determine whether new gene expression induced by IGF-I was necessary for the antiapoptotic effects of this agonist, we used α-amanitin, a highly specific inhibitor of RNA polymerase II (23). Apoptosis was induced in RIG cells by serum deprivation in the presence or absence of PI3 kinase inhibitors and α-amanitin. We found no difference in the amount of apoptosis between cells treated with IGF-I plus wortmannin and α-amanitin separately or in combination (Fig. 4). Therefore, we concluded that the major component of PI3 kinase-independent survival signaling does not require new transcription.

A novel survival signaling pathway independent of PI3 kinase and Akt.

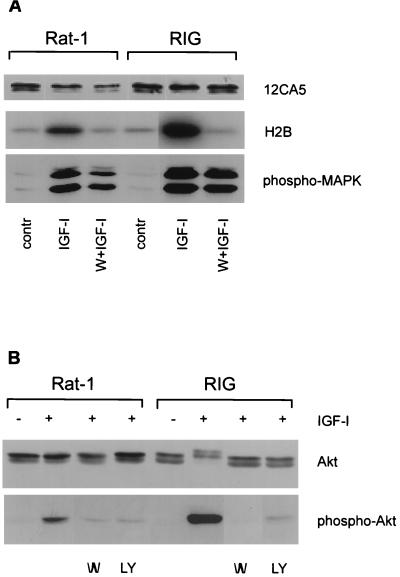

Since Akt is an effector of survival signaling downstream from PI3 kinase, the phenomenon of wortmannin-insensitive survival signaling by overexpressed IGF-I receptors can be explained in two ways: (i) Akt might be activated in a PI3 kinase-independent fashion, or (ii) an Akt-independent pathway might be used. If the first suggestion were true, Akt activation induced by IGF-I in RIG cells would not be inhibited by wortmannin. However, we found that IGF-I-mediated activation of endogenous or ectopically expressed Akt was sensitive to PI3 kinase inhibitors regardless of the level of IGF-I receptor expression (Fig. 5), which favors the existence of an Akt-independent pathway in RIG cells, which overexpress IGF-I receptors.

FIG. 5.

Wortmannin can inhibit IGF-I-mediated activation of Akt independently of the level of IGF-I receptors. (A) RIG and Rat-1 fibroblasts transiently expressing HA-Akt were pretreated with 100 nM wortmannin (W) for 15 min and then stimulated for another 15 min with 250 ng of IGF-I per ml. Then the cells were lysed, HA-Akt was immunoprecipitated, and kinase assays with histone H2B used as a substrate were done as described previously (24). To show that wortmannin was not inhibiting protein kinase activation nonspecifically, the activation of MAP kinase (MAPK) was assessed with phosphospecific anti-ERK antibody (lower panel). contr, control. (B) RIG and Rat-1 cells were pretreated for 15 min with 100 nM wortmannin (W) or 20 μM of LY294002 (LY) and then stimulated with IGF-I for another 15 min. Activation of endogenous Akt in RIG and Rat-1 cells was assessed in the Western blot by using phospho-Akt (S473)- specific antibodies (lower panel). To control equal loading of Akt, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with Akt-specific antibodies (upper panel).

Our experiments with Cos cells demonstrated that a kinase-deficient mutant of Akt [Akt(K179A)] can function as a dominant negative Akt by inhibiting IGF-I-mediated protection from apoptosis. To further confirm that protective signaling from overexpressed IGF-I receptors can bypass Akt, we analyzed the effect of kinase-deficient Akt(K179A) overexpression on IGF-I mediated survival in Rat-1 and RIG cells. Rat-1 and RIG cells transiently expressing dominant negative Akt(K179A) were irradiated with UVB and incubated with or without IGF-I before being fixed with formalin and analyzed for apoptosis in a single-cell assay. Unlike Rat-1/Akt(K179A) fibroblasts, RIG/Akt(K179A) cells can be protected by IGF-I (Fig. 6A, bottom). Thus, Akt activity is not required for survival mediated by overexpressed IGF-I receptors.

FIG. 6.

Expression of kinase-deficient mutant Akt(K179A) abolishes IGF-I-mediated protection in Rat-1 fibroblasts but not in RIG cells overexpressing IGF-I receptors. Cells transiently expressing HA-Akt(K179A) were fixed 6 h after UVB irradiation, stained with anti-HA 12CA5 antibody, and subjected to a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-fluorescein nick end labeling assay for DNA fragmentation. (A) Upper images were taken through a neutral filter (nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole appeared blue); lower images show the same field photographed through a red-and-green filter. Cells expressing HA-Akt(K179A) appear red; nuclei with DNA fragmentation are green or yellow. Red cells with yellow nuclei are scored as apoptotic. (B) The frequency of apoptosis was determined by counting several hundred cells expressing HA-Akt(K179A). Error bars reflect the standard deviation between different coverslips from the same experiment. Similar results were obtained in three independent transfections. In cells expressing HA-Akt(K179A), differences between the degree of apoptosis in the presence and the absence of IGF-I were statistically significant in RIG cells (P < 0.01) but not in Rat-1 cells (P = 0.72).

Bad is not the target of PI3 kinase- and Akt-independent survival signaling.

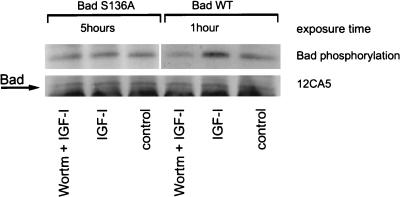

It was shown previously that phosphorylation of Bad on serine 136 allowed Bad interaction with 14-3-3 and resulted in inactivation of the proapoptotic function of Bad (47). Recently Akt was identified as a serine 136 kinase for Bad in circumstances where cells expressing Bad were protected from apoptosis by platelet-derived growth factor or IL-3 (8, 9). To determine whether IGF-I can also induce Bad phosphorylation, we expressed Bad containing a point mutation in the Akt phosphorylation site (Bad S136A) and the wild-type Bad in RIG cells as an HA-tagged protein. After the cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and then stimulated with IGF-I, only wild-type (not mutant) Bad became phosphorylated (Fig. 7). Since phosphorylation was wortmannin sensitive, it is very likely that IGF-I used the Akt pathway to phosphorylate Bad; therefore, Bad is not the target of the PI3 kinase- and Akt-independent survival signaling.

FIG. 7.

IGF-I induces wortmannin-sensitive phosphorylation of Bad. RIG cells expressing HA-Bad and HA-Bad(S136A) were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, pretreated with 200 nM wortmannin (Wortm) for 15 min, and stimulated with IGF-I for 20 min. Then the cells were lysed, and HA-Bad was precipitated with 12CA5 antibodies. The presence of Bad in the immunoprecipitate was verified by Western blotting with 12CA5 antibodies. HA-Bad blot was exposed for 1 h and HA-Bad(S136A) was exposed for 5 h, since the phosphorylation of Bad(S136A) in the nonstimulated cells was lower than that of the wild-type Bad.

DISCUSSION

Roles of PI3 kinase, Akt, and Bad in survival signaling.

In studies of the ability of IGF-I to protect cells from UV-induced apoptosis, we previously reported that activation of PI3 kinase was both necessary and sufficient and that activation of Akt was sufficient for protection (24). Similar results were obtained in experimental systems where apoptosis was induced by different means including overexpression of c-myc, interruption of contact between the cells and the extracellular matrix, and withdrawal of survival factors (12, 28). In this communication, we show that activation of Akt is not only sufficient but also necessary for IGF-I-mediated survival in Rat-1 fibroblasts and Cos cells expressing endogenous levels of IGF-I receptors.

In the course of these experiments, we observed that inhibition of PI3 kinase activity by wortmannin or LY294002 sometimes failed to completely block protection. The resistance to inhibition by PI3 kinase inhibitors was particularly evident in Rat-1 cells engineered to express high levels of the IGF-I receptor, suggesting the existence of a survival signaling pathway that does not require PI3 kinase activation. Resistance of survival signaling to PI3 kinase inhibitors was observed in cultured neuronal cells (35), hematopoietic cells treated with IL-3 or IL-4 (46a), and primary mouse embryo fibroblasts and late passages of Rat-1 cells treated with IGF-I (data not shown). This indicates that the PI3 kinase- and Akt-independent pathway is not generated solely by IGF-I receptor overexpression but is more likely to have a more general function in normal cell physiology.

The molecular mechanism by which this alternative signaling pathway operates is unknown, but the data reported here point to a posttranscriptionally regulated pathway that not only functions independently of PI3 kinase but also does not involve Akt or Bad.

It is possible that overexpressed IGF-I receptors induced an activation of Akt and/or phosphorylation of Bad without activation of PI3 kinase. Indeed, there have been reports of PI3 kinase-independent activation of Akt (21, 22, 38) and phosphorylation of Bad by kinases other than Akt (42, 47). Moreover, it is not known whether Bad is involved in all cases of survival signaling in which Akt participates and whether Bad is the only target mediating the survival effects of Akt. However, in this report we show that no Akt activation or Bad phosphorylation induced by IGF-I was observed in RIG cells when PI3 kinase was inhibited. Therefore, this novel survival pathway seems to be independent not only of PI3 kinase but also of Akt and Bad.

Survival signaling pathways independent of PI3 kinase, Akt, and Bad.

Only a few survival pathways besides the PI3 kinase-Akt-Bad pathway have been described so far. These include MAP kinase (33a, 44), NF-κB (29), calmodulin kinases (13, 41), and protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ) (2, 10). In PC-12 cells, survival effects were attributed to MAP kinase signaling based on experiments with PD098059 (33a) and constitutively active MEK (44). Since we and others did not find the connection between activation of MAP kinase and survival in fibroblasts or epithelial cells, the contribution of this signaling pathway to survival may be restricted to neuronal cells. Because IGF-I-induced survival signaling occurred in the presence of α-amanitin, we doubt that a transcription factor such as NF-κB is involved. Moreover, we did not observe phosphorylation of IκB in RIG cells treated with IGF-I (data not shown).

A possible role of calmodulin kinases in IGF-I survival signaling was suggested by the results of experiments with the inhibitor KN93 (41). Incubation of RIG cell cultures with this compound increased the amount of apoptosis, but addition of IGF-I could completely overcome this effect and also protect from UV-induced apoptosis in the presence of KN93 (data not shown). Thus, calmodulin kinase II is unlikely to be the effector for PI3 kinase-independent survival.

We also doubt that atypical PKCs play a role in IGF-I-mediated survival. First, there is evidence for activation of PKCζ by products of PI3 kinase (32, 40), and insulin-induced translocation of PKCζ is wortmannin sensitive (16, 31). Second, the effects of PKCζ activation were found to be mediated through MAP kinase and NF-κB activation (1, 27). We and others showed that the MAP kinase cascade is not involved in survival signaling by IGF-I (8, 18, 24), and NF-κB can be excluded for the reasons described above. Finally, inhibition of PKCζ activity by the UV-induced protein Par-4 was recently suggested as a possible mechanism of UVC-mediated apoptosis (10). Since we observed an increase in apoptosis when UV irradiation was performed in the presence of inhibitors of RNA synthesis, it makes PKCζ an unlikely candidate for PI3K/Akt-independent survival.

Effects of IGF-I on stress kinase signaling.

Evidence on the role of stress-activated kinase cascades in the regulation of apoptosis is full of contradictions. Depending on the experimental conditions, the activities of these kinases are seen as a cause of apoptosis (6, 15), a consequence of stress (5), or a survival force (33). Inhibition of p38 in cultured fetal neuronal cells was reported to be one possible mechanism of insulin-mediated survival (14). We did not find any inhibition of UV-induced p38 activation by IGF-I. On the contrary, IGF-I stimulated p38 activation in RIG cells to an extent comparable to that achieved with UV induction (25).

Survival signaling pathways and resistance to cancer therapy.

Induction of apoptosis is widely believed to be the predominant mechanism by which chemotherapy and radiation kill cancer cells. Thus, there is considerable interest in understanding the cellular mechanisms that regulate the sensitivity of cells to therapy-induced apoptosis. For example, we previously reported that overexpression of the EGF receptor allows it to activate PI3 kinase and Akt, thus converting ligands of the EGF receptor into survival factors. This could contribute to the poor prognosis associated with tumors displaying elevated expression of EGF receptor family members. If this hypothesis is correct, one would expect that inhibition of PI3 kinase in these tumor cells would restore their sensitivity to therapy-induced apoptosis. Although wortmannin failed to suppress the growth of xenografts in nude mice (39), it will be of interest to see if better results can be achieved by combinations of PI3 kinase inhibitors with conventional antitumor agents.

The data presented in this report reveal an additional mechanism by which cells can become resistant to apoptosis, namely, by overexpression of IGF-I receptors and engagement of a novel survival signaling pathway. The IGF-I receptor is reportedly overexpressed in a wide variety of tumors (4, 26), including breast (36, 37) and head and neck (43) tumors. Inhibition of PI3 kinase in these tumors should have little effect on their sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiation, and experiments to test this hypothesis are in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kevin Overman for technical assistance, Anke Klippel for the Akt vectors, and Michael Greenberg and Robert Datta for vectors expressing Bad, antibodies, and valuable discussions. G.K. acknowledges Leonid Guzman, Inna Alesina, and Hans-Joerg Schaeffer, without whose help it would have been almost impossible to complete this work.

This work was supported by USPHS NIH grants CA 39076 and GM 47332.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berra E, Diaz-Meco M T, Dominguez I, Municio M M, Sanz L, Lozano J, Chapkin R S, Moscat J. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for mitogenic signal transduction. Cell. 1998;74:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berra E, Municio M M, Sanz L, Frutos S, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J. Positioning atypical protein kinase C isoforms in the UV-induced apoptotic signaling cascade. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4346–4544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertollini L, Ciotti M T, Cherubini E, Cattaneo A. Neurotrophin-3 promotes the survival of oligodendrocyte precursors in embryonic hippocampal cultures under chemically defined conditions. Brain Res. 1997;746:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blakesley V A, Stannard B S, Kalebic T, Helman L J, LeRoith D. Role of the IGF-I receptor in mutagenesis and tumor promotion. J Endocrinol. 1997;152:339–344. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1520339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardone M H, Salvesen G S, Widmann C, Johnson G, Frisch S M. The regulation of anoikis: MEKK-1 activation requires cleavage by caspases. Cell. 1997;90:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y R, Wang X, Templeton D, Davis R J, Tan T H. The role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in apoptosis induced by ultraviolet C and gamma radiation. Duration of JNK activation may determine cell death and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31929–31936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darnay B G, Aggarwal B B. Early events in TNF signaling: a story of associations and dissociations. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:559–566. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datta S R, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg M E. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delpeso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz-Meco M T, Municio M M, Frutos S, Sanchez P, Lozano J, Sanz L, Moscat J. The product of par-4, a gene induced during apoptosis, interacts selectively with the atypical isoforms of protein kinase C. Cell. 1996;86:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudek H, Datta S R, Franke T F, Birnbaum M J, Yao R, Cooper G M, Segal R A, Kaplan D R, Greenberg M E. Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;275:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke T F, Kaplan D R, Cantley L C. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hack N, Hidaka H, Wakefield M J, Balazs R. Promotion of granule cell survival by high K+ or excitatory amino acid treatment and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase activity. Neuroscience. 1993;57:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90108-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidenreich K A, Kummer J L. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase by insulin in cultured fetal neurons. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9891–9894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikizawa K, Kajiwara K, Basaki Y, Koshio T, Yanagihara Y. Evidence for a role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in IL-4-induced germline C epsilon transcription. Cell Immunol. 1996;170:134–140. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauffmann-Zeh A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Ulrich E, Gilbert C, Coffer P, Downward J, Evan G. Suppression of c-Myc-induced apoptosis by Ras signaling through PI(3)K and PKB. Nature. 1997;385:544–548. doi: 10.1038/385544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy S G, Wagner A J, Conzen S D, Jordan J, Bellacosa A, Tsichlis P N, Hay N. The PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway delivers an anti-apoptotic signal. Genes Dev. 1997;11:701–713. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne P H, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:2783–2793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klippel A, Reinhard C, Kavanaugh W M, Apell G, Escobedo M A, Williams L T. Membrane localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is sufficient to activate multiple signal-transducing kinase pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4117–4127. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konishi H, Matsuzaki H, Tanaka M, Ono Y, Tokunaga C, Kuroda S, Kikkawa U. Activation of RAC-protein kinase by heat shock and hyperosmolarity stress through a pathway independent of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7639–7643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konishi H, Matsuzaki H, Tanaka M, Takemura Y, Kuroda S, Ono Y, Kikkawa U. Activation of protein kinase B (Akt/RAC-protein kinase) by cellular stress and its association with heat shock protein Hsp27. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:493–498. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koumenis C, Giaccia A. Transformed cells require continuous activity of RNA polymerase II to resist oncogene-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7306–7316. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulik G, Klippel A, Weber M J. Antiapoptotic signaling by the insulin-like growth factor I receptor, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Akt. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1595–1606. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulik, G., and Weber, M. J. Unpublished data. 1997.

- 26.LeRoith D, Werner H, Neuenschwander S, Kalebic T, Helman L J. The role of the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor in cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;766:402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb26689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozano J, Berra E, Municio M M, Diaz-Meco M T, Dominguez I, Sanz L, Moscat J. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for kappa B-dependent promoter activation by sphingomyelinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19200–19202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marte B M, Downward J. PKB/Akt: connecting phosphoinositide 3-kinase to cell survival and beyond. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:355–358. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayo M W, Wang C Y, Cogswell P C, Rogersgraham K S, Lowe S W, Der C J, Baldwin A S. Requirement of NF-kappa-B activation to suppress p53-independent apoptosis induced by oncogenic ras. Science. 1997;278:1812–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5344.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minshall C, Arkins S, Freund G G, Kelley K W. Requirement for phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase to protect hemopoietic progenitors against apoptosis depends upon the extracellular survival factor. J Immunol. 1996;156:939–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizukami Y, Hirata T, Yoshida K. Nuclear translocation of PKC zeta during ischemia and its inhibition by wortmannin, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakanishi H, Brewer K A, Exton J H. Activation of the zeta isozyme of protein kinase C by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishina H, Fischer K D, Radvanyi L, Shahinian A, Hakem R, Rubie E A, Bernstein A, Mak T W, Woodgett J R, Penninger J M. Stress-signaling kinase Sek1 protects thymocytes from apoptosis mediated by CD95 and CD3. Nature. 1997;385:350–353. doi: 10.1038/385350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Parizzas M, Saltiel A R, LeRoth D. Insulin-like growth factor inhibits apoptosis using the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:154–161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson J E, Kulik G, Jelinek T, Reuter C W, Shannon J A, Weber M J. Src phosphorylates the insulin-like growth factor type I receptor on the autophosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31562–31571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philpott K L, McCarthy M J, Klippel A, Rubin L L. Activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt kinase promote survival of superior cervical neurons. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:809–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Railo M J, von Smitten S K, Pekonen F. The prognostic value of insulin-like growth factor-I in breast cancer patients. Results of a follow-up study on 126 patients. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:307–311. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resnik J L, Reichart D B, Huey K, Webster N J, Seely B L. Elevated insulin-like growth factor I receptor autophosphorylation and kinase activity in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1159–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sable C L, Filippa N, Hemmings B, VanObbergen O E. cAMP stimulates protein kinase B in a wortmannin-insensitive manner. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schultz R M, Merriman R L, Andis S L, Bonjouklian R, Grindey G B, Rutherford P G, Gallegos A, Massey K, Powis G. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activity of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibitor, wortmannin. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:1135–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toker A, Meyer M, Reddy K K, Falck J R, Aneja R, Aneja S, Parra A, Burns D J, Ballas L M, Cantley L C. Activation of protein kinase C family members by the novel polyphosphoinositides PtdIns-3,4-P2 and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32358–32367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tombes R M, Grant S, Westin E H, Krystal G. G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis are induced in NIH 3T3 cells by KN-93, an inhibitor of CaMK-II (the multifunctional Ca2+/CaM kinase) Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1063–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H G, Rapp U R, Reed J C. Bcl-2 targets the protein kinase Raf-1 to mitochondria. Cell. 1996;87:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber, M. J. 1994. Unpublished data.

- 44.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis R J, Greenberg M E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao R, Cooper G M. Requirement for phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in the prevention of apoptosis by nerve growth factor. Science. 1995;267:2003–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.7701324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao R, Cooper G M. Growth factor-dependent survival of rodent fibroblasts requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but is independent of pp70S6K activity. Oncogene. 1996;13:343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46a.Zamorano J, Wang H Y, Wang L-M, Pierce J H, Keegan A D. IL-4 protects cells from apoptosis via the insulin receptor substrate pathway and a second independent signaling pathway. J Immunol. 1996;157:4926–4933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer S J. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L) Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]