Abstract

Despite extensive evidence implicating Ras in cardiac muscle hypertrophy, the mechanisms involved are unclear. We previously reported that Ras, through an effector-like function of Ras GTPase-activating protein (GAP) in neonatal cardiac myocytes (M. Abdellatif et al., J. Biol. Chem. 269:15423–15426, 1994; M. Abdellatif and M. D. Schneider, J. Biol. Chem. 272:527–533, 1997), can up-regulate expression from a comprehensive set of promoters, including both cardiac cell-specific and constitutive ones. To investigate the mechanism(s) underlying these earlier findings, we have used recombinant adenoviruses harboring a dominant negative Ras (17N Ras) allele or the N-terminal domain of GAP (nGAP), responsible for the Ras-like effector function. Inhibition of endogenous Ras reduced basal levels of [3H]uridine and [3H]phenylalanine incorporation into total RNA, mRNA, and protein, with parallel changes in apparent cell size. In addition, 17N Ras markedly inhibited phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (pol II), known to regulate transcript elongation, accompanied by down-regulation of its principal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (Cdk7). In contrast, nGAP elicited the opposite effects on each of these parameters. Furthermore, cotransfection of constitutively active Ras (12R Ras) with wild-type pol II, rather than a truncated mutant lacking the CTD, demonstrated that Ras activation of transcription was dependent on the pol II CTD. Consistent with a potential role for this pathway in the development of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy, α1-adrenergic stimulation similarly enhanced pol II phosphorylation and Cdk7 expression, where both effects were inhibited by dominant negative Ras, while pressure overload hypertrophy led to an increase in both hyperphosphorylated and hypophosphorylated pol II in addition to Cdk7.

Cardiac hypertrophy, in response to mechanical load or growth factors, characteristically entails the induction of a so-called fetal program of cardiac gene expression, superimposed on a generalized increase in cellular RNA and protein content. Signaling pathways leading to the transcription of fetal genes have been extensively studied (19, 26, 32, 35, 45, 47, 48, 50, 56–59), but information is still lacking for the underlying molecular mechanisms that augment total protein content. Despite evidence from gene transfer in vitro and in vivo implicating the proto-oncoprotein Ras in cardiac hypertrophy (1, 24, 56, 57), there is only meager information on the exact mechanism(s) by which this GTP-binding molecule might augment cardiac growth.

Our previous finding that Ras can enhance expression of a generalized set of promoters, including constitutive ones, led us to speculate that Ras may be a candidate molecule that regulates global gene expression during cardiac hypertrophy (1). In support of this inference, a transgenic mouse expressing activated Ras in the heart manifested cardiac hypertrophy (23, 24), although the exact mechanism for Ras-dependent growth was not established, and an indirect effect, inherent with a chronic model, cannot be excluded. Through mutational analysis of the effector domain of Ras, we have shown that a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) binding site is necessary for Ras-dependent gene induction in the ventricular myocytes, suggesting that GAP predominantly exercises an effector role in the cardiac cells (2). This conclusion was corroborated by the fact that full-length GAP and the N-terminal region of GAP (nGAP) both mimicked the global effect of Ras on cardiac gene expression.

While GAP may thus mediate the generalized effects of Ras on gene expression, one Ras effector protein, Raf, has been implicated more specifically in the regulation of fetal genes that are reexpressed during ventricular hypertrophy, such as ANF and MLC-2 (56). A possible dissociation between the signaling pathways that lead to an increase in total cellular protein and the fetal phenotype was recently suggested in connection with angiotensin II (AII) stimulation (49): rapamycin blocked the increase in ribosomal p70 kinase (S6K) activity, and consequently the increase in total cell protein, but did not impair the reactivation of fetal genes (skeletal α-actin gene and ANF) or the increase in mitogen-activated protein kinase activity.

An increase in total protein per cell (the sine qua non of hypertrophy) is itself a complex process that involves regulation of multiple cellular functions. Cardiac hypertrophy is accompanied by enhanced activity of RNA polymerase I (pol I) (38, 39), pol II, and pol III (10), which regulate synthesis of rRNA, mRNA, and tRNA, respectively, as well as by enhanced p70 S6K (49) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF-4E) (61) phosphorylation and activities, which each contribute to the regulation of overall protein synthesis. However, the precise signaling pathways involved in mediating these events are still largely unknown.

In this report, we demonstrate that Ras and GAP can mediate the increase in total RNA, including mRNA, and protein accumulation per cell. These effects are accompanied by changes in pol II phosphorylation and cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (Cdk7) expression. Phenylephrine, an α1-adrenergic agonist known to induce cardiac hypertrophy and previously shown to employ the Ras pathway, likewise induced pol II phosphorylation and up-regulation of Cdk7, both of which were inhibited by 17N Ras. Moreover, pressure overload hypertrophy led to an increase in total pol II and Cdk7 proteins after 7 days. Thus, our results implicate Ras-dependent phosphorylation of pol II as a potential mechanism for the increase in total protein per cell that is characteristic of cardiac hypertrophy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of adenoviruses.

Recombinant adenoviruses were constructed, propagated, and titered as previously described (20). Briefly, pJM17, constituting the adenoviral genome, was cotransfected into 293 cells, using Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL), along with the pΔE1sp1 shuttle vector containing either 17N Ras downstream of a simian virus 40 promoter, nGAP downstream of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, or the simian virus 40 promoter only. The adenovirus-CMV (Ad.CMV) recombinant was a gift from J. Nevins. Through homologous recombination, the test genes were integrated into the adenoviral genome, to create the recombinants Ad.SV.17N Ras, Ad.CMV.nGAP, and Ad.SV. Next, the viruses were propagated on 293 cells and purified by using CsCl2 banding followed by dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline and 10% glycerol. Titers were determined on 293 cells overlaid with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium DMEM plus 5% equine serum and 0.5% agarose.

Cardiac cell culture.

The neonatal cardiac myocytes were cultured as previously described (1). Briefly, cells were cultured from 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats. After dissociation, the cells were subjected to Percoll gradient centrifugation followed by differential preplating, to enrich for cardiac myocytes and deplete nonmyocytes. Cells were plated in DMEM with 5% equine serum at a density of 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 cells/35-mm-diameter dish.

Immunocytochemistry.

After 24 h in culture, cells were infected, at 10 to 20 viral particles/cell, with Ad.SV, Ad.17N Ras, Ad.CMV, or Ad.nGAP in serum-free medium. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were fixed in 100% methanol for 5 min and incubated for 1 h with an antibody (MF20; 1:50) (4) to sarcomeric myosin heavy chain (MHC) or with a 1-μg/ml concentration of either anti-Ras (Oncogene Science), anti-GAP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-Cdk7 (Santa Cruz), diluted in 0.1 M Tris-HCl–5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)–2% milk, (pH 7.5). By using a 1:1,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-linked secondary antibodies for 30 min, the immune complexes were detected by a colorimetric reaction utilizing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium substrates.

Detection of F-actin by using FITC-phalloidin.

Cell were plated on glass coverslips coated with gelatin. Forty-eight hours after virus delivery, the cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde plus 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and then with 3% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, in CB buffer (10 mM MES [morpholineethanesulfonic acid], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose [pH 6.1]). The cells were then washed with CB buffer and incubated with 1 μg of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-phalloidin (Sigma) per ml for 1 h at 37°C in Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.5]). Cell were washed with CB buffer and mounted.

[3H]uridine and [3H]phenylalanine incorporation.

Twenty-four hours after viral delivery, the cells were incubated with 1 μCi of either [3H]uridine or [3H]phenylalanine per ml for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated by using a Qiagen RNA/DNA extraction kit, which also allowed simultaneous extraction of DNA from each sample. Subsequently, poly(A) RNA was extracted from the total RNA by using a Qiagen Oligotex extraction kit. Total protein was extracted with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–10 mM NaCl–3 mM MgCl2–0.5% Nonidet P-40. Nuclei were separated from the lysate by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min; the DNA was precipitated with 5% trichloroacetic acid and resuspended in 0.3 N NaOH. Cellular protein was precipitated from the lysate by using 10% trichloroacetic acid in the presence of 0.1% BSA and recovered on GF/C filters. The 3H content of the RNA and protein fractions was measured with a scintillation counter and normalized to the DNA content of each sample as measured at 260 nm.

32Pi labeling of the cardiac cells and immunoprecipitation.

Forty-eight hours after viral delivery, the cells were incubated with 0.1 mCi of 32Pi per ml in phosphate-free DMEM for 24 h. The cells were then lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline plus 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 μg of leupeptin, 1 μg of aprotinin, 0.1 mg of Pefabloc, and 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, 10 mM Na3VO4, and 0.1 μM okadiac acid). Pol II was immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of polyclonal anti-Pol II antibody (Santa Cruz) in the presence of protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz). The precipitated immune complex was washed three times with RIPA buffer and then eluted by boiling for 5 min in 50 μl of 1× Laemmli loading buffer.

Plasmid transfection.

Twenty-four hours after plating, cardiac myocytes were cotransfected, using Lipofectamine, with 0.5 μg of a luciferase reporter gene driven by the adenovirus-associated transcriptional initiator sequence downstream from six Sp1 enhancer sites, plus 2 μg of pcDNA vector (Invitrogen), CMV-driven, α-amanitin-resistant pol II or the C-terminal-domain (CTD)-truncated Δ5 pol II, kindly provided by Jeff Corden (17), and increasing concentrations of 12R Ras as indicated previously (2). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured with a luminometer.

Western blotting.

Forty-eight hours after viral delivery, the cells were lysed with RIPA buffer. Protein were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), electroblotted with 3-[cyclohexylamino]-1-propanesulfonic acid buffer plus 10% methanol, and incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody to pol II (8WG16; QED Biosciences) or polyclonal antibody to Cdk7 or Cdk2 (Santa Cruz), each at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml diluted in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl [pH 7.5], 0.3% Tween 20, 0.2% BSA). The blots were next incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies at a dilution of 1:10,000 or 1:1,000, respectively. The blots were washed in TBST without BSA, and the specific bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Selective extraction of free and speckle pol II fractions.

As previously described (6, 7), cells were lysed in the plate by adding ice-cold TD buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 μg of leupeptin, 1 μg of aprotinin, 0.1 mg of Pefabloc, and 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, 10 mM Na3VO4, 0.1 μM okadiac acid). After the plates were incubated on ice for 10 min, the cells were scraped into Eppendorf tubes and vigorously vortexed for 1 min. The cell debris was spun down, and the supernatant, now containing detergent-sensitive (free) pol II, was separated from the pellet, containing detergent-resistant fractions (speckles) (6, 7). The pellet was then extracted with an equal volume of RIPA buffer. Equal volumes from all fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 4 to 15% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel and subjected to Western analysis using 0.1 μg of monoclonal anti-pol II antibody 8WG16.

Aortic banding.

The transverse aorta is exposed between the right innominate artery and the left carotid of 20- to 30-g, 12-week-old adult mice (FVB; Harlan Laboratories). An aortic constriction is created by tying a 6-0 suture against a 3-mm length of a 27-gauge needle. After two knots, the 27-gauge needle is promptly removed, which yields a constriction of approximately 0.3 mm, equal to the outer diameter of the 27-gauge needle. This produces a 60 to 80% aortic narrowing and is monitored for by a specially designed Doppler flow probe. The flow characteristics indicated the magnitude of constriction. As a control, a sham operation was performed on another animal at the same time. Seven days later, the animals were sacrificed, and the heart/body weight ratio was determined before extraction of total protein from the isolated hearts for Western analysis.

RESULTS

Regulation of total RNA and protein synthesis by 17N Ras and GAP.

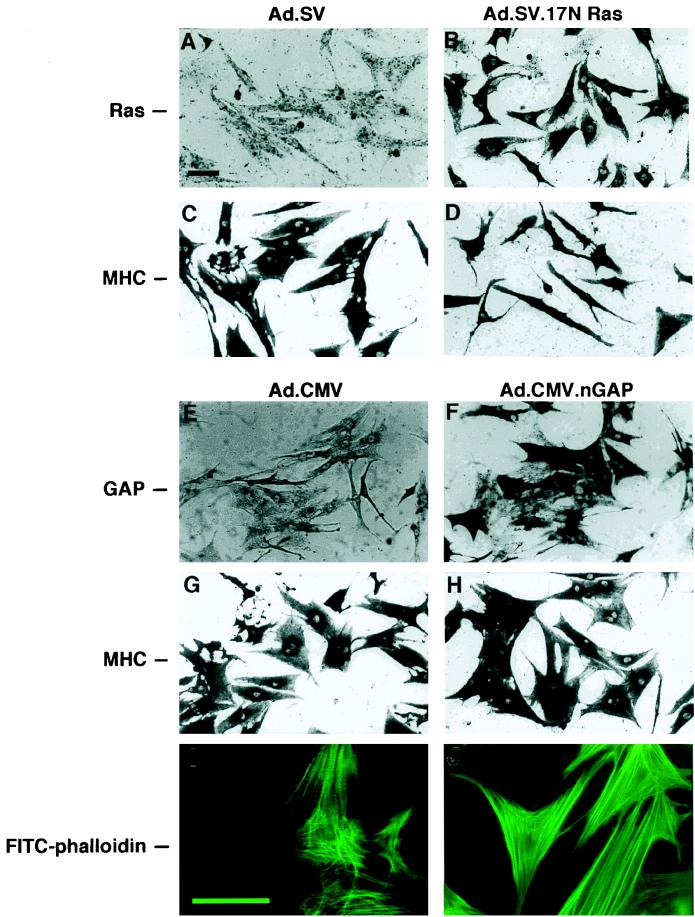

To directly test the effect of any foreign gene on endogenous cardiac cellular functions, it is advantageous to deliver the test gene homogeneously to the majority of cells. However, transfection of plasmid DNA by any of the methods known to date typically results in only 1 to 10% efficiency of gene delivery to the neonatal cardiac myocytes. To achieve a higher transfer efficacy, we engineered replication-deficient adenoviruses harboring either 17N Ras or nGAP (amino acids 1 to 666) lacking the catalytic GTPase-activating domain. At a multiplicity of infection of 10 to 20 viral particles/cell, the genes were delivered to virtually 100% of the cultured cells, as detected by indirect alkaline phosphatase staining (Fig. 1B and F), compared to cells infected with the control viruses, Ad.SV and Ad.CMV (Fig. 1A and E). Ras and nGAP protein expression was also confirmed by Western analysis (data not shown). Cells immunostained with an antibody against sarcomeric MHC reveal the predominance of myocytes (>95%) in these primary cultures (Fig. 1G and H).

FIG. 1.

Recombinant adenoviruses deliver 17N Ras or nGAP genes to ∼100% of the cultured neonatal cardiac cells and result in morphological changes. Twenty-four hours after culturing, the cells were treated, at 10 to 20 viral particles/cell, with the indicated recombinant viruses in serum-free medium. Forty-eight hours later the cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-MHC anti-Ras or anti-GAP antibody or were incubated with FITC-phalloidin, as indicated on the left. Cells in panels A, B, E, and F, panels C, D, G, and H, and panels I and J were from three different cultures. The bar in panel A (50 μm) applies to panels A to H; the bar in panel I (50 μm) applies to panels I and J.

Noteworthy were the reciprocal morphological changes after viral delivery of 17N Ras versus nGAP. While 17N Ras-treated cells appeared smaller than the control cells, nGAP-expressing cells were visibly larger, although this observation is consistent with either a change in cell volume or cell spreading. Notably, nGAP-infected cells also showed highly organized actin fibers (Fig. 1I and J), similar to those previously reported in phenylephrine-induced hypertrophy (60).

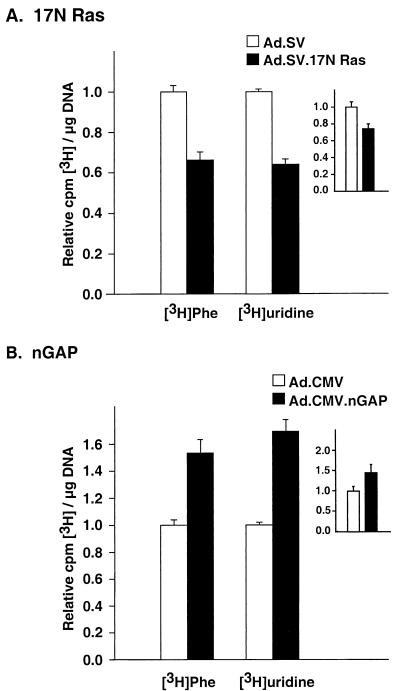

We have previously shown that Ras and GAP regulate a broadly inclusive set of promoters in cardiac muscle cells (1, 2). To test whether these molecules might thus be involved in regulation of global gene expression, we measured the incorporation of [3H]uridine into total RNA and [3H]phenylalanine into total protein. Inhibition of endogenous Ras by the 17N Ras allele resulted in 34% (P < 0.01) reduction in [3H]uridine and 32% (P < 0.01) reduction in [3H]phenylalanine incorporation into total protein (Fig. 2A). Little reduction was seen in [3H]thymidine incorporation, as expected under the serum-starved conditions of these experiments (data not shown). As anticipated from our previous transfection data, nGAP led to the opposite effects, resulting in 68% (P < 0.01) and 46% (P < 0.01) increases in [3H]uridine and [3H]phenylalanine incorporation into total RNA and protein, respectively (Fig. 2B). These result show that Ras- and GAP-dependent pathway can augment total RNA and protein synthesis in cardiac cells.

FIG. 2.

Ad.17N Ras and Ad.nGAP regulate RNA and protein synthesis. Cells were treated with Ad.SV and Ad.17N Ras (A) or Ad.CMV and Ad.nGAP (B) in serum-free medium. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were incubated with 1 μCi of either [3H]uridine or [3H]phenylalanine per ml for an additional 24 h. Total RNA and DNA were simultaneously extracted from [3H]uridine-treated cells, while protein and DNA were extracted from cells treated with [3H]phenylalanine. The 3H content of RNA or protein was measured, and the results were normalized to the DNA content of each sample and expressed in values relative to the mean of the control (Ad.SV or Ad.CMV, adjusted to 1). The insets show the 3H content in the poly(A) mRNA fraction after normalization to DNA content, expressed in values relative to the mean of the control (Ad.SV or Ad.CMV, adjusted to 1). Each data point is the mean of six samples ± standard error.

The majority of RNA (>90%) consists of rRNA; hence, the experiment above reflects changes in the synthesis of the latter molecule but does not discern any alterations in mRNA or tRNA synthesis. To address this issue, we further extracted poly(A) mRNA from the total RNA fraction and measured its 3H content, normalized to the DNA content. The changes in mRNA synthesis paralleled the changes observed in total RNA synthesis, where 17N Ras resulted in a 25% decrease (P < 0.05) whereas nGAP resulted in 40% increase (P < 0.05) in [3H]mRNA (Fig. 2, insets). Therefore, at least rRNA and mRNA syntheses are regulated by 17N Ras and GAP proteins in cardiac myocytes.

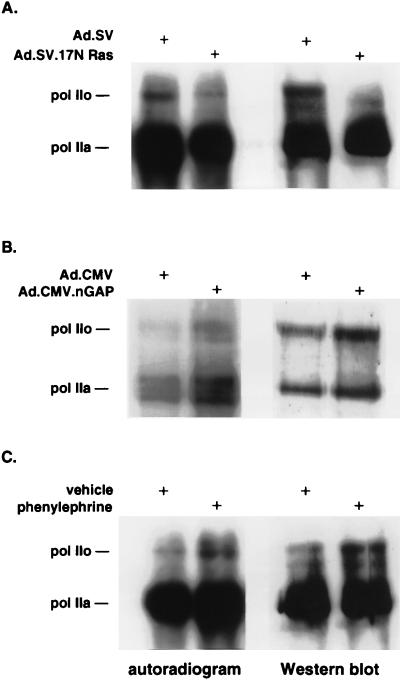

Regulation of pol II phosphorylation by 17N Ras, nGAP, and phenylephrine.

The CTD of pol II, which is highly phosphorylated (27), regulates the rate of transcript elongation (7, 33, 34, 44) and, in turn, full-length mRNA abundance. To test whether 17N Ras or nGAP might alter pol II phosphorylation, we immunoprecipitated pol II from metabolically 32Pi labeled cells after adenoviral gene transfer for either of these molecules. 17N Ras reduced 32Pi incorporation into both the pol IIa (hypophosphorylated) and pol IIo (hyperphosphorylated) isoforms under serum-free conditions (Fig. 3A). Western analysis of the same blot confirmed that reduced pol II phosphorylation was accompanied by an equivalent decrease in hyperphosphorylated pol IIo. Conversely, nGAP-treated cells showed an increase in pol II phosphorylation, resulting in an increase of the slower-migrating pol IIo (Fig. 3B). Phenylephrine, previously shown to induce hypertrophy and to increase total RNA in neonatal cardiac cells, also enhanced pol II phosphorylation, with selective accumulation of pol IIo but not pol IIa (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that control of pol II phosphorylation is a plausible mechanism underlying the regulation of global mRNA synthesis by the Ras/GAP pathway and by phenylephrine.

FIG. 3.

Ad.17N Ras, Ad.nGAP, and phenylephrine modulate pol II phosphorylation. (A) Cardiac myocytes were infected with either Ad.SV or Ad.17N Ras. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were incubated with 0.1 mCi of 32Pi per ml in phosphate-free DMEM for 24 h. The cells were then lysed, and pol II was immunoprecipitated. The precipitate was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 6% gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The latter was first autoradiographed and then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-pol II antibody 8WG16. The experiment is a representative of two with similar results. (B) Cardiac cells were infected with Ad.CMV or Ad.nGAP and analyzed as for panel A. The experiment is representative of two with similar results. (C) Twenty-four hours after plating, cells were serum starved for 48 h before incubation with 100 μM phenylephrine or vehicle for an additional 24 h in the presence of 32Pi. Cells were then subjected to the same analysis as for panel A. The experiment is representative of two with similar results.

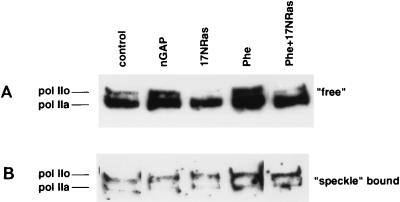

RNA pol II is present as both free and speckle-bound populations.

Pol II is known to be present both in a free (unbound) form that engages in transcription and in a hyperphosphorylated, detergent-resistant form, contained in membrane-bound speckles that also store RNA splicing factors (6, 7). It was therefore necessary to determine which of these pol II populations was the target for the phosphorylation seen in Fig. 3. Under low-detergent extraction conditions, free pol IIa and pol IIo isoforms were isolated from the cardiac cells (Fig. 4A). A subsequent high-detergent extraction allowed isolation of predominantly pol IIo, which constitutes the speckle-bound form (Fig. 4B). As shown, 17N Ras caused a decrease of free pol IIo, in contrast to an increase effected by nGAP or phenylephrine. On the other hand, speckle-bound pol II, extracted from the same cells, undergoes no change in isoform distribution. Furthermore, 17N Ras markedly inhibited phenylephrine’s effect, supporting a Ras-dependent signaling pathway for this hypertrophic factor, in agreement with previous reports (32, 57).

FIG. 4.

17N Ras, nGAP, and phenylephrine regulate free pol II. Cells were infected with the viruses indicated. Twenty-four hours later, they were stimulated with 0.1 μM phenylephrine (Phe), where shown, for an additional 24 h. Cellular protein was differentially extracted as described in Materials and Methods, and the different fractions were electrophoresed separately on an SDS–4 to 15% gradient polyacrylamide gel followed by immunoblotting with anti-pol II antibody 8WG16.

Requirement of the pol II CTD for Ras-activated expression.

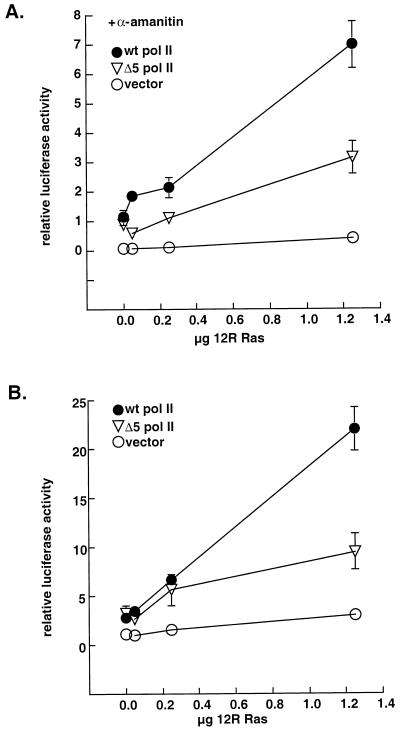

The observed Ras-dependent phosphorylation of pol II does not directly prove the functional significance of the pol II CTD, or its modification, in cardiac cells. Therefore, we cotransfected the cardiac myocytes with a luciferase reporter construct plus α-amanitin-resistant pol II genes, in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of constitutively active Ras (12R Ras). The Sp1.Inr promoter, containing six Sp1 sites upstream of an initiator sequence, was used as a representative of a minimal housekeeping promoter, previously shown to support CTD-independent transcription under basal unstimulated conditions (17). In the presence of α-amanitin, to inhibit endogenous pol II, the α-amanitin-resistant, wild-type (wt) pol II and a truncated mutant (Δ5 pol II) retaining only 5 of 52 CTD heptad repeats restored basal levels of promoter activity with equal efficacy. However, when 12R Ras was cotransfected, wt pol II and Δ5 pol II-dependent transcription levels were elevated 7.1 ± 0.8- and 3.1 ± 0.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 5A). Thus, Ras-dependent augmentation of the promoter’s transcription is largely dependent on the presence of the CTD. In the absence of α-amanitin, similar results were obtained: both pol II mutants increased basal promoter expression up to ∼3-fold, which 12R Ras further enhanced 21.96 ± 2-fold in the presence of wt pol II but only 9.48 ± 1.8-fold in the presence of Δ5 pol II (Fig. 5B). The results of the latter experiment confirm that observations made in the presence of α-amanitin were not merely due to compromised expression of 12R Ras when Δ5 pol II was the sole source of pol II activity and also suggest that the activity of endogenous pol II is limiting, at least under these experimental conditions.

FIG. 5.

12R Ras activation of the Sp1.Inr promoter is dependent on the pol II CTD. Cardiac myocytes were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of the Sp1.Inr luciferase reporter gene, 2 μg of the pcDNA vector, CMV-driven pol II, or Δ5 pol II genes, and increasing concentrations of 12R Ras in the presence (A) or absence (B) of α-amanitin (2.5 μg/ml). Total plasmid DNA and promoter content was kept constant by using plasmid SV-sport. Cells were then analyzed for luciferase activity; data are expressed relative to the mean of control cells transfected with pcDNA, in the absence of 12R Ras and α-amanitin, adjusted to 1. Each data point is the mean of six samples ± standard error.

17N Ras, nGAP, and phenylephrine regulate Cdk7.

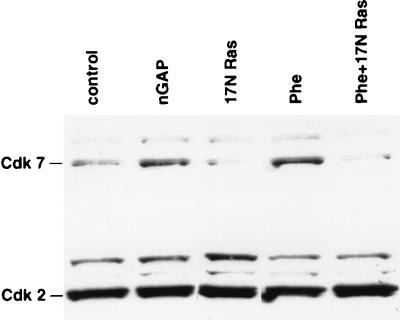

Cdk7, a cyclin-dependent kinase which phosphorylates and activates the cell cycle regulators Cdk4, Cdk2, and Cdc2, also has recently been identified as a major kinase for phosphorylation of the pol II CTD (16, 51, 54). It was therefore of interest to test the state of this kinase in cardiac cells treated with either Ad.17N Ras, Ad.nGAP, or phenylephrine. Figure 6 shows that Cdk7 was up-regulated by treatment with nGAP or phenylephrine in serum-starved cardiac cells and that the induction by phenylephrine was inhibited by 17N Ras. In comparison, expression of Cdk2 under the same conditions was unaffected.

FIG. 6.

Ad.17N Ras, Ad.nGAP, and phenylephrine regulate Cdk7 expression. Cells were infected with the viruses indicated. Twenty-four hours later, they were stimulated with phenylephrine (Phe), where shown, for an additional 24 h. Cells were then lysed and separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel, immunoblotted, and incubated with the indicated antibodies. The data are representative of three separate experiments with similar results.

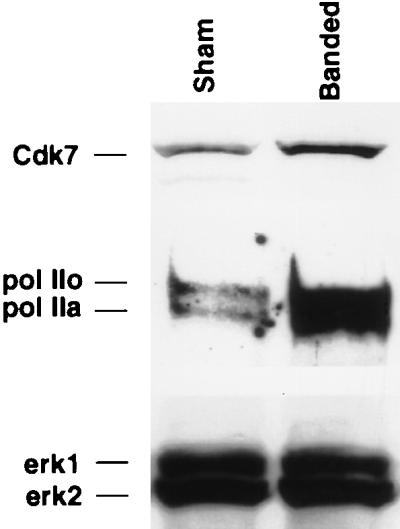

Pressure overload leads to enhanced pol IIo, pol IIa, and Cdk7 protein expression.

To test the relevance of our findings in pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy in vivo, we performed Western analysis on the protein extracted from hearts subjected to aortic constriction for 7 days. The results in Fig. 7 show that total pol II, including pol IIo and pol IIa fractions, and Cdk7 proteins were up-regulated, in contrast to the invariable levels of the mitogen-activated protein kinases Erk1 and Erk2 detected on the same blot. This result suggests that pol II and its major kinase play a role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

FIG. 7.

Mice were subjected to aortic banding or a sham operation as indicated. Seven days after the operation, protein was extracted from the isolated hearts, and 25 μg was electrophoresed on an SDS–4 to 15% gradient polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The same blot was then incubated sequentially with anti-pol II, anti-Cdk7, and anti-Erk antibodies as indicated. The experiment is representative of two with identical results.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that Ras and GAP regulate total RNA and protein synthesis in cardiac muscle cells. These results indicate that the regulation of the wide array of promoters seen in our earlier studies was, as predicted, the result of an effect on the basal transcriptional apparatus of the cell, although additional effects at the translational level are not excluded. In our previous studies, we had used plasmid transfection, which, though a powerful tool for obtaining provisional information, has its limitations. Notably, transfection efficiency in cardiac myocytes is only 1 to 10%, rendering most experiments reporter dependent. Directly testing the effect of the genes of interest on any of the endogenous biological functions of the cell, or on biochemical signaling intermediaries, is best achieved at a higher gene transfer efficiency. This prompted us to construct adenoviral vectors with proven high transfer efficiency in cardiac cells (29, 30). Adenovirus is the only vehicle known to date that allows delivery of test genes to 100% of cardiac cells upon exposure to a sufficient number of viral particles. Recombinant adenoviruses have recently been instrumental in determining the basis of the postmitotic cardiac phenotype (28, 30) and more recently have been used in studies of signaling mechanisms in cardiac hypertrophy (62, 63). Because recombinant viruses are more cumbersome to construct than plasmids, only a few select genes were chosen for this task. The wt and activated forms of Ras were dismissed because of their potential carcinogenicity. As alternatives, we engineered a dominant negative Ras, which will inhibit endogenous Ras, and nGAP, with a preferential Ras-like effect in cardiac myocytes. These viruses enabled us to measure the effects of the latter genes on cell morphology, actin stress fibers, total RNA and protein synthesis, pol II phosphorylation, and Cdk7 expression. In addition, these viral vehicles will eventually allow us to study the effects of Ras and GAP on adult cardiac myocytes, which are resistant to any conventional transfection method.

Hypertrophy is defined as an increase in cell volume and mass, as a consequence of increased total cellular protein per cell. Whether induced by pressure overload (55) or by α1-adrenergic (5), AII, or phorbol ester (3) stimulation, hypertrophy is also accompanied by an increase in total RNA content. This in turn may be a result of the associated increases in RNA polymerase activities (43) and the rate of RNA synthesis (25, 31). Although an increase in total RNA might sufficiently explain the increase in total protein that we observed, it does not exclude a superimposed effect on translation or on ribosome biogenesis. Indeed, it has been shown that eIF-4E is hyperphosphorylated, as a prerequisite for its activation, in response to left ventricular pressure overload (61). Analogously, AII increased p70 ribosomal S6K activity, in parallel with protein content (49). While we show an effect of Ras and nGAP on pol II phosphorylation, we do not exclude regulation of RNA pol I and pol III by the same pathway, especially as our data also reflect an increase in rRNA synthesis. Similarly, effects of the recombinant viruses on eIF-4E and p70 S6K in cardiac muscle cells remain to be tested.

Enhanced phosphorylation pol II by serum has been previously reported (14), but the signaling molecules and growth factors needed for this effect are still largely unknown. Although phosphorylation of the CTD may be superfluous in vitro (36), its relevance in transcript elongation in vivo (9, 33, 44) is indisputable. On the other hand, the unphosphorylated form of pol II preferentially associates with the initiation complex (34). Therefore, it appears that transcription may be regulated at two checkpoints: initiation, which requires the unphosphorylated form of pol II, and elongation, which is enhanced by phosphorylation of the CTD. Accordingly, a critical ratio of free pol IIa to pol IIo is required for maximum transcription efficiency. Our results showing that the Ras pathway enhances pol II phosphorylation and is functionally dependent on the CTD suggest that Ras-enhanced transcription may be a direct consequence of an increase in pol IIo.

It has been previously shown that pol II, at least in kidney and liver cells, is present in two different nuclear locations: membrane-bound speckles, which are discrete nuclear subdomains that also store splicing factors, and free polymerase, which engages in transcription (6, 7). The hyperphosphorylated speckle-bound polymerase has been shown to interact both physically (66) and functionally (13) with mRNA splicing factors. Using a previously reported differential extraction method, we were able to demonstrate that free pol II was the fraction subjected here to regulatory phosphorylation by the Ras pathway and phenylephrine, in support of their role in modulating RNA transcription.

Although several pol II CTD kinases have been reported, Cdk7 has been regarded as the primary kinase given its proximity to the polymerase in the TFIIH transcription initiation complex (16, 54). Therefore, the reciprocal changes in Cdk7 protein expression produced by either nGAP or 17N Ras could potentially explain the corresponding changes in pol II phosphorylation observed in our studies. Cdk8, an alternative pol II kinase, was not detected in the postnatal heart (data not shown), but the possible roles of Cdk9 or other CTD kinases in Ras-dependent phosphorylation of pol II, and in hypertrophy more generally, remain to be studied.

Ras can regulate minimal, TATA-dependent or TATA-independent promoters in mink lung epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and cardiac myocytes (1), whereas GAP preferentially mediates the effect of Ras in cardiac but not epithelial cells (2), and thus its effect is contingent on cell type. Our results establishing an effector-like function for GAP concur with its known Ras-like effect on the K+ channels in atrial cells (37, 65). The SH2-SH3 domain of GAP has been previously reported to activate the c-fos promoter (41), cooperate in cellular transformation (11), and mediate germinal vesicle breakdown in Xenopus oocytes (15), but a Ras-like activity of full-length GAP has been reported only for cardiac myocytes (37, 65). Furthermore, the activity of the SH2-SH3 domain of GAP is modulated by the flanking N-terminal hydrophobic and/or pleckstrin domains in a similarly cell-type-specific fashion. For example, the presence of those domains abrogates SH2-SH3 nGAP activity in CHO9 cells but not in A14 cells (41). The differences observed between cell types in the response to GAP is not surprising, taking into account the existence of several GAP-binding proteins, including p190 (53), p62 (64), p68 G3BP (46), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (12), and the multitude of functional domains, including the SH3-binding, SH2-SH3-SH2, pleckstrin homology, and CaLB domains, that constitutes this molecule. Thus, the tissue distribution of GAP and the identities of interacting proteins, their ratios relative to each other and to GAP, and their interactions with tissue-specific factors may determine the net observed function(s) of GAP or nGAP in a given cell type.

GAP can bind Ras through its catalytic domain (amino acids 714 to 1047), utilizing amino acids Arg786 and Lys831 (42), but the possibility of additional sites of contact cannot be disregarded. Specifically, whether the SH2-SH3 domain is also involved in physical interaction with Ras is unproven. Consistent with this interpretation, however, an isolated catalytic domain has a lower binding affinity to Ras than does full-length GAP (18). Whether isolated nGAP function is dependent on or independent of Ras is likewise in question and might also vary with the cell background. For example, in cardiac myocytes, inhibiting endogenous Ras with a neutralizing antibody did not inhibit nGAP’s effect on K+ channel activity (37). In contrast, in CHO9 or A14 cells, activation of the c-fos promoter by nGAP could be inhibited by using 17N Ras (41). Similarly, cooperation of v-src and nGAP for cellular transformation is dependent on endogenous Ras (11). Direct measurement of Ras activity, after adenoviral delivery of nGAP, revealed no increase in the GTP/GDP ratio bound to Ras (data not shown). Hence, a positive feedback loop from GAP to Ras, or a dominant negative effect of the truncated GAP on endogenous GAP, is excluded as an explanation for the Ras-like effect of nGAP observed in our studies.

In addition to regulation of gene expression (21, 60), RhoA also induces reorganization of actin filaments in cardiac myocytes (22). Therefore, a plausible mechanism by which GAP exerts the effects observed in our study may be through modulation of its associating protein, p190, which possesses a Rho GTPase-activating function (52, 53). Several other lines of evidence support a role for GAP in actin organization, albeit through a different mechanism. First, McGlade et al. have shown that overexpression of nGAP in Rat-2 cells will disrupt actin stress fibers, reduce focal contacts, and impair the ability of the cells to adhere to fibronectin (40). Second, two human Ras-GAP-related proteins, IQGAP1 and IQGAP2, harbor an N-terminal, potential F-actin-binding motif (8). Third, we have discovered, using the yeast-two hybrid system, that GAP interacts with the actin-binding protein filamin (data not shown).

In summary, Ras and GAP augment total RNA, mRNA, and protein accumulation in cardiac muscle cells. These effects are accompanied by corresponding changes in pol II phosphorylation and Cdk7 expression, providing a possible mechanism for the regulation of global mRNA synthesis by the Ras pathway. In addition, the analogous effects of phenylephrine, a canonical hypertrophic agonist, and their inhibition by 17R Ras suggest a plausible role for this pathway in the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Corden for providing plasmids, F. Ervin for technical assistance, R. MacLellan for comments and suggestions, and R. Roberts for encouragement and support.

This work was supported in part by American Heart Association grant 96G-1175, Baylor Junior Faculty Seed Funding, and a Chao fellowship to M. Abdellatif and by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL47567, R01 HL52555, P01 HL49953, and P50 HL42267 to M. D. Schneider.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdellatif M, MacLellan W R, Schneider M D. p21 Ras as a governer of global gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15423–15426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdellatif M, Schneider M D. An effector-like function of Ras GTPase-activating protein predominates in cardiac muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:525–533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allo S N, Carl L L, Morgan H E. Acceleration of growth of cultured cardiomyocytes and translocation of protein kinase C. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C319–C325. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.2.C319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman D A. Immunocytochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:763–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishopric N H, Simpson P C, Ordahl C. Induction of the skeletal α-actin gene in α1-adrenoreceptor-mediated hypertrophy of rat cardiac myocytes. J Clin Investig. 1987;80:1194–1199. doi: 10.1172/JCI113179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bregman D B, Du L, Li Y, Ribisi S, Warren S L. Cytostellin distributes to nuclear regions enriched with splicing factors. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:387–396. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bregman D B, Du L, van der Zee S, Warren S L. Transcription-dependent redistribution of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II to discrete nuclear domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:287–298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brill S, Li S, Lyman C W, Church D M, Wasmuth J J, Weissbach L, Bernards A, Snijders A J. The Ras GTPase-activating-protein-related human protein IQGAP2 harbors a potential actin binding domain and interacts with calmodulin and Rho family GTPases. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4869–4878. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cadena D L, Dahmus M E. Messenger RNA synthesis in mammalian cells is catalyzed by the phosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12468–12474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutilletta A F, Rudnik M, Zak R. Muscle and non-muscle cell RNA polymerase activity during the development of myocardial hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1978;10:677–687. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(78)90403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeClue J E, Vass W C, Johnson M R, Stacey D W, Lowy D R. Functional role of GTPase-activating protein in cell transformation by pp60v-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6799–6809. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DePaolo D, Beusch J E-B, Carel K, Bhuripanyo P, Leitner J W, Draznin B. Functional interaction of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with GTPase-activating protein in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1450–1457. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du L, Warren S L. A functional interaction between the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and pre-mRNA splicing. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:5–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubois M-F, Nguyen V T, Dahmus M E, Pages G, Poussegur J, Bensaude O. Enhanced phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II upon serum stimulation of quiescent cells: possible involvement of MAP kinases. EMBO J. 1994;13:4787–4797. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duchesne M, Schweighoffer F, Parker F, Clerc F, Frobert Y, Thang M N, Tocqué B. Identification of the SH3 domain of GAP as an essential sequence for GAP-mediated signaling. Science. 1993;259:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.7678707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feaver W J, Svejstrup J Q, Henry N L, Kornberg R D. Relationship of CDK-activating kinase and RNA polymerase II CTD kinase TFIIH/TFIIK. Cell. 1994;79:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber H-P, Hagmann M, Seipel K, Georgiev O, West M A L, Litingtung Y, Schaffner W, Corden J. RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain required for enhancer-driven transcription. Nature. 1995;374:660–662. doi: 10.1038/374660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gideon P, John J, Frech M, Lautwein A, Clark R, Scheffler J E, Wittinghofer A. Mutational and kinetic analyses of the GTPase-activating protein (GAP)–p21 interaction: the C-terminal domain of GAP is not sufficient for full activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2050–2056. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glennon P E, Kaddoura S, Sale E M, Sale G J, Fuller S J, Sugden P H. Depletion of mitogen-activated protein kinase using an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide approach downregulates the phenylephrine-induced hypertrophic response in rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78:954–961. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham F L, Prevec L. Methods in molecular biology. Vol. 7. Clifton, N.J: The Humana Press Inc.; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines W A, Thorburn A. Ras and rho are required for α-induced hypertrophic gene expression in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:485–494. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshijima M, Sah V P, Wang Y, Chien K R, Brown J H. The low molecular weight GTPase rho regulates myofibril formation and organization in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Involvement of rho kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7725–7730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter J J, Rockman H A, Chien K R. Left ventricular hypertrophy produced by tissue-targeted expression of activated Ras in transgenic mice. Circulation. 1994;90:I-197. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter J J, Tanaka N, Rockman H A, Ross J, Chien K R. Ventricular expression of a MLC-2v-ras fusion gene induces cardiac hypertrophy and selective diastolic dysfunction in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23173–23178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kako K J, Varnai K, Beznak M. RNA synthesis and RNA content of nuclei prepared from hearts during hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 1972;6:56–66. doi: 10.1093/cvr/6.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kariya K, Karns L R, Simpson P C. An enhancer core element mediates stimulation of the rat beta-myosin heavy chain promoter by an alpha 1-adrenergic agonist and activated beta-protein kinase C in hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3775–3782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim W-Y, Dahmus M E. Immunochemical analysis of mammalian RNA polymerase II subspecies. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:14219–14225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirshenbaum L A, MacLellan W R, Mazur W, French B A, Schneider M D. Highly efficient gene transfer to adult rat ventricular myocytes by recombinant adenovirus. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:381–387. doi: 10.1172/JCI116577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirshenbaum L A, Schneider M D. Adenovirus E1A represses cardiac gene transcription and reactivates DNA synthesis in ventricular myocytes, via alternative pocket protein- and p300-binding domains. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7791–7794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirshenbaum, L., A. Abdellatif, M. Chakraborty, and M. D. Schneider. Human E2F-1 reactivates cell cycle progression in ventricular myocytes and represses cardiac gene transcription. Dev. Biol. 179:402–411. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Koide T, Rabinowitz M. Biochemical correlates of cardiac hypertrophy. II. Increased rate of RNA synthesis in experimental cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res. 1969;24:9–18. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaMorte V J, Thorburn J, Absher D, Spiegel A, Brown J H, Chien K R, Feramisco J R, Knowlton K. Gq- and Ras-dependent pathways mediate hypertrophy of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes following α1-adrenergic stimulation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13490–13496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laybourn P J, Dahmus M E. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase IIA occurs subsequent to interaction with the promoter and before initiation of transcription. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13165–13173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Flores O, Weinmann R, Reinberg D. The nonphosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II preferentially associates with the preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10004–10008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLellan W R, Lee T C, Schwartz R J, Schneider M D. Transforming growth factor-beta response elements of the skeletal alpha-actin gene. Combinatorial action of serum response factor, YY1, and the SV40 enhancer-binding protein, TEF-1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16754–16760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mäkelä T P, Parvin J D, Kim J, Huber L J, Sharp P A, Weinberg R A. A kinase-deficient transcription factor TFIIH is functional in basal and activated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5174–5178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin G A, Yatani A, Clark R, Conroy L, Polakis P, Brown A M, McCormick F. GAP domains responsible for Ras p21-dependent inhibition of muscarinic atrial K channel currents. Science. 1992;255:192–194. doi: 10.1126/science.1553544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDermott P J, Carl L L, Conner K J, Allo S N. Transcriptional regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis during growth of cardiac myocytes in culture. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4409–4416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDermott P J, Rothblum L I, Smith S D, Morgan H E. Accelerated rates of ribosomal RNA synthesis during growth of contracting heart cells in culture. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18220–18227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGlade J, Brunkhorst B, Anderson D, Mbamalu G, Settleman J, Dedhar S, Rozakis-Adcock M, Chen L B, Pawson T. The N-terminal region of GAP regulates cytoskeletal structure and cell adhesion. EMBO J. 1993;12:3073–3081. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medema R, Laat W L D, Martin G A, McCormick F, Bos J L. GTPase-activating protein SH2-SH3 domains induce gene expression in a ras-dependent fashion. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3425–3430. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miao W, Eichelberger L, Baker L, Marshall M S. p120 Ras GTPase-activating protein interacts with Ras-GTP through specific conserved residues. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15322–15329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nair K G, Cutilletta A F, Zak R, Koide T, Rabinowitz M. Biochemical correlates of cardiac hypertrophy. I. Experimental model; changes in heart weight, RNA content, and nuclear RNA polymerase activity. Circ Res. 1968;23:451–462. doi: 10.1161/01.res.23.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Brien T, Hardin S, Greenleaf A, Lis J T. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain and transcriptional elongation. Nature. 1994;370:75–77. doi: 10.1038/370075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paradis P, MacLellan W R, Belaguli N S, Schwartz R J, Schneider M D. Serum response factor mediates AP-1-dependent induction of the skeletal alpha-actin promoter in ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10827–10833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parker A, Maurier F, Delumeau I, Duchesne M, Faucher D, Debussche L, Dugue A, Schweighoffer F, Tocque B. A Ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3-domain-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2561–2569. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker T G, Chow K L, Schwartz R J, Schneider M D. Positive and negative control of the skeletal alpha-actin promoter in cardiac muscle. A proximal serum response element is sufficient for induction by basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) but not for inhibition by acidic FGF. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3343–3350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramirez M T, Post G R, Sulakhe P V, Brown J H. M1 muscarinic receptors heterologously expressed in cardiac myocytes mediate Ras-dependent changes in gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8446–8451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sadoshima J, Izumo S. Rapamycin selectively inhibits angiotensin II-induced increase in protein synthesis in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Circ Res. 1995;77:1040–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadoshima J-I, Izumo S. Signal transduction pathways of angiotensin II induced c-fos gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Circ Res. 1993;73:424–438. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serizawa H, Makela T P, Conaway J W, Weinberg R A, Young R A. Association of Cdk-activating kinase subunits with transcription factor TFIIH. Nature. 1995;374:270–282. doi: 10.1038/374280a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Settleman J, Narasimhan V, Foster L C, Weinberg R. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding the GAP-associated protein p190: implications for a signaling pathway from Ras to the nucleus. Cell. 1992;69:539–549. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90454-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Settleman J, Narasimhan V, Foster L C, Weinberg R. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding the GAP-associated protein p190: implications for a signaling pathway from Ras to the nucleus. Cell. 1992;69:539–549. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90454-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiekhattar R, Mermeistein F, Fisher R P, Drapkin R, Dynlacht B, Wessling H, Morgan D, Reinberg D. Cdk-activating kinase complex is a component of human transcription factor TFIIH. Nature. 1995;374:283–287. doi: 10.1038/374283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swynghedauw B, Moalic J M, Bouveret P, Bercovici J, Bastie D D L, Schwartz K. Messenger RNA content and complexity in normal and overloaded rat heart: a preliminary report. Eur Heart J. 1984;5:211–217. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/5.suppl_f.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thorburn A. Ras activity is required for phenylephrine-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cardiac muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:1417–1422. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thorburn A, Thorburn J, Chen S Y, Powers S, Shubeita H E, Feramisco J R, Chien K R. HRas-dependent pathways can activate morphological and genetic markers of cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2244–2249. . (Erratum, 268:16082.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thorburn J, Frost J A, Thorburn A. Mitogen-activated protein kinases mediate changes in gene expression, but not cytoskeletal organization associated with cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1565–1572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thorburn J, McMahon M, Thorburn A. Raf-1 kinase activity is necessary and sufficient for gene expression changes but not sufficient for cellular morphology changes associated with cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30580–30586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thorburn J, Xu S, Thorburn A. MAP kinase- and Rho-dependent signals interact to regulate gene expression but not actin morphology in cardiac muscle cells. EMBO J. 1997;16:1888–1900. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wada H, Ivester C T, Carabello B A, Cooper G T, McDermott P J. Translational initiation factor eIF-4E: a link between cardiac load and protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8359–8364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, Huang S, Sah V P, Ross J, Jr, Brown J H, Han J, Chien K R. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2161–2168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Su B, Sah V P, Brown J H, Han J, Chien K R. Cardiac hypertrophy induced by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7, a specific activator for c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in ventricular muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5423–5426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong G, Müller O, Clark R, Conroy L, Moran M F, Polakis P, McCormick F. Molecular cloning and nucleic acid binding properties of the GAP-associated tyrosine phosphoprotein p62. Cell. 1992;69:551–558. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90455-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yatani A, Okabe K, Polakis P, Halenbeck R, McCormick F, Brown A M. Ras p21 and Gap inhibit coupling of muscarinic receptors of atrial K channels. Cell. 1990;61:769–776. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90187-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuryev A, Patturajan M, Litingtung Y, Joshi R V, Gentile C, Gebara M, Corden J. The C-terminal domain of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II interact with a novel set of serine/threonine-rich proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6975–6980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]